[In this report, I return to one of my pet bêtes noires – Official History. It is a straightforward ‘B’-class piece, and it should, I think, be of interest to the general reader as well as to academic historians.]

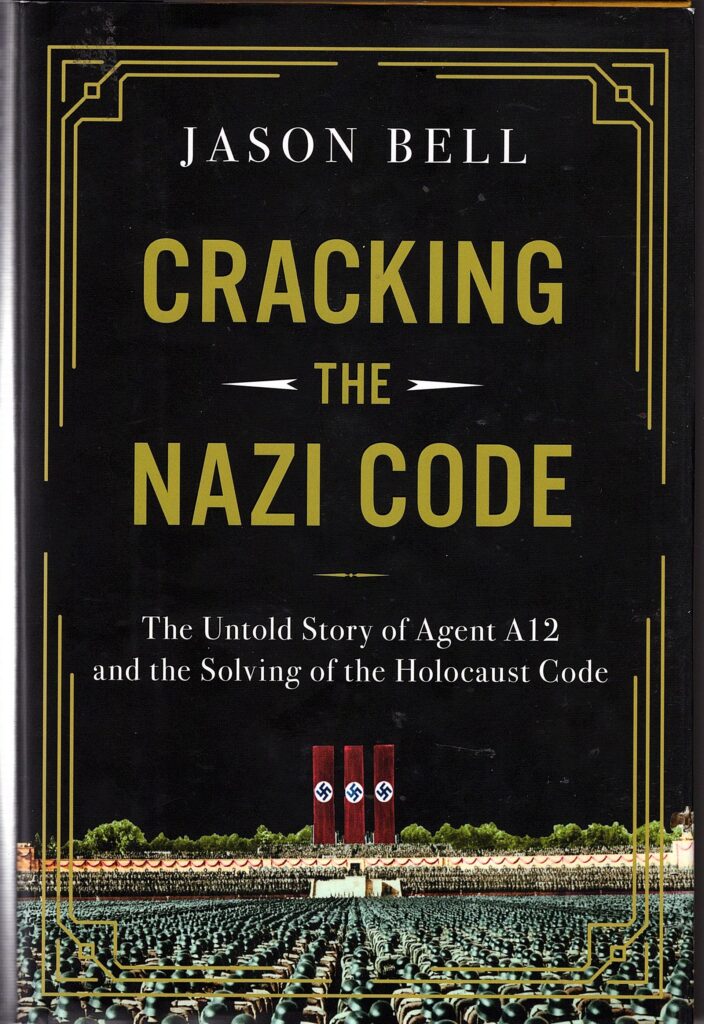

In its September 2025 issue (Volume 36, Number 3), the journal Diplomacy and Statecraft, one in the Taylor and Francis stable, delivered a series of articles under the title Official History: Writing the History of Military Operations and Intelligence (see https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/fdps20/36/3). I was drawn to what appeared to be an intriguing set written by mostly familiar names, and I plucked out ten of them to read and analyze more closely. This report is dedicated to exploring what they had to say, and to making some conclusions concerning their messages.

The collection was edited by Professor Patrick Salmon and Dr Richard Smith, both members of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, Chief Historian and Principal Historian respectively, with the former apparently working in Cambridge and the latter in Peterborough. I should at this stage ‘declare an interest’ concerning some of the authors. I enjoyed a brief exchange with Professor Salmon when I was researching the PB416 disaster: he encouraged me to contact 617 Squadron (which I did, rather fruitlessly), but he then absented himself from any further discussion. Mark Seaman published a review of Misdefending the Realm in the Times Literary Supplement: I have since criticized him on coldspur for the dogmatic and unscholarly stance he took on judging that Francis Suttill Jr’s book on his father, PROSPER, constituted the final word on the controversy concerning the betrayal of the eponymous SOE circuit. I have been in occasional email contact with Roderick Bailey and Tony Comer on matters concerning the SOE in Italy and Albania, and GCHQ, respectively.

My article will explore a number of themes that immediately struck me: the difficulties the editors have in defining what they meant by ‘Official History’, a pattern echoed in the articles that they commissioned; the questionable way in which official history is approved as a method of celebration, or even propaganda; the curious way that the historians are chosen, and what ‘privileged access’ to secret archives means in practice; the extremely troubling way in which unreleased archival material is exploited but not identified; and the failure to recognize what the implications of the appearance of new facts, or the release of fresh archival material, will mean for the published record once the ‘definitive’ or ‘authoritative’ account has appeared.

Three of the articles are available as ‘Free Access’, and are asterisked. The remainder require a subscription, either individually, or else through an academic institution.

Introduction by Patrick Salmon and Richard Smith (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533027)

This article struggles with some definitions from the outset. The authors state that the edition of the journal originated from a series of online seminars on Official History, and ‘explored themes around the use and utility of history in the creation of public policy, the relationship between historians and policymakers, and the desirability of “collective memory” in government’. Why that dubious concept of ‘collective memory’ had to be put in quotation marks is not clear: perhaps the authors were subtly expressing their concerns about exactly what it meant, and that it was a fashionable way of stating that institutions should learn from their successes and their failures. And they then go on to state that:

The concept of official history was interpreted in its widest sense, beyond the Cabinet Official History programme, to include documentary series, ‘authorized’ [those inverted commas again] histories such as those produced by the intelligence agencies, histories of the wartime Special Operations Executive, and institutional histories such as those commissioned by the Atomic Energy Authority.

That is a very odd list. My immediate reaction was that ‘documentary series’ must describe television documentaries, but, on reflection, I judge that it must refer to the occasional publication of state documents, such as the series Documents on British Foreign Policy, 1919-1939, which I have productively trawled. Indeed, the authors present a useful paragraph about this class of publication later in their article. Whether it counts as ‘history’ or simply ‘archival material’ must depend, I suppose, on how extensive and learned the editing of such documents is. The authors cite Rohan Butler, the Foreign Office’s Historical Adviser between 1963 and 1983 as saying that ‘it was more satisfactory for the historian to receive the raw documentary material, from which to work out their own conclusions and narratives, than to be spoon-fed an official account’. No doubt. ‘Spoonfeeding’ is itself a rather derogatory term, and why should the historian have to deal with a pre-selected set of documents rather than being able to roam around the originals, and discover possibly overlooked items of value?

And why should histories of the SOE be singled out as a separate category without any indication of why they do not fit into either the ‘official’ or ‘authorized’ class? Is it because the unit was disbanded in 1946, its rump absorbed into MI6, and thus needs special treatment? And what is this category of ‘institutional histories’? The Preface to my copy of Volume 1 of Margaret Gowing’s Britain and Atomic Energy starts by declaring: “This book is the first instalment of an official history of the United Kingdom atomic energy project: it is an official history of the same genre as the civil and military histories of the Second World War which have been written under the aegis of the Cabinet Office.” That seems pretty clear-cut to me. And an earlier ‘Note on Documentation’ by Gowing, prominently displayed, informs readers that ‘in accordance with the practice of the official war histories, references to official papers that are not yet publicly available have been omitted’. The authors later characterize the history of atomic energy as an example of ‘official’ history, but maybe that is simply a circular argument using their own bizarre classification scheme. Thus the distinctions made by Salmon and Smith seem irregular and misleading.

The authors set out to describe what the objectives of early official history were, namely educating the public in a readable way, and providing a work of instructive value for future military officers and strategists, recognizing that those two aims might be in opposition. They also cite Harold Wilson’s rather bizarre statement from 1966, when he announced that the range of official history was to be extended to peacetime affairs. The series was intended to provide ‘authoritative histories in their own right: a reliable secondary source for historians until all the records are available in the National Archives: and a “fund of experience” for future government use’. The availability of ‘all the records’, indeed! We shall be waiting a long time for that day, and, even then, how will anyone know that ‘all the records’ have been released?

The article does go on to introduce what are the essential questions about official history, echoing the challenges that Herbert Butterfield described in his 1949 study Official History: its Pitfalls and its Criteria: Why do governments commission official histories? Can we trust official historians if they are the only ones allowed to see the documents? Can we be sure that official historians have seen all the relevant documents? Is there a danger that official historians may become too institutionalised or too close to their subjects? And the authors claim that the papers in the volume will address ‘many of these themes’. They highlight Declan O’Reilly’s suggestion (concerning Harry Hinsley’s multi-volume study) that ‘the official history of wartime British intelligence was intended to restore the reputation of the intelligence agencies in the wake of public spy exposés’, adding that ‘the aim was not openness but information control and avoidance of government embarrassment’. Indeed. The purpose behind such ventures becomes more controversial. Salmon and Smith expressly report that the GCHQ commissioned its centenary history ‘to increase transparency and reshape public perceptions of the organisation in the wake of the Edward Snowden revelations’. That objective sounds perilously like propaganda.

Lastly, the authors dedicate a paragraph to the SOE, which has benefitted, so they say, from seven official histories already. They describe how Mark Seaman examines the ‘motivations’ behind their commissioning, as if there might be an objective more sinister than describing what actually happened as precisely as possible. Here they reproduce Seaman’s familiar conclusion that ‘further official histories are unnecessary, as existing records and independent works have already filled the gaps’. (Why Seaman was allowed two contributions is a puzzlement. I also think that it would have been beneficial to have invited Christopher Moran, the author of Classified, to join the throng, as it would have provided some balance to the general theme of ‘officialdom’ dominating the debate.) Whether there remain outstanding conflicts, and how even the most able reader is supposed to compile a consolidated reliable history from such a variety of sources, is not a question that the editors feel is worth asking. They leave us with the hope that the special edition of the journal ‘will not only enhance our understanding of the role and value of official history but also inspire scholarly inquiry into the subject’. Perhaps this offering of mine may be considered such a phenomenon.

Taking Stock of Official History, Past, Present and Future: Reflections of an Official Historian by Sir Lawrence Freedman * (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533025)

Sir Lawrence Freedman’s contribution is a more informal offering than the other articles, since it is a transcript of the keynote lecture that he gave to the Official History Seminar in January 2025. His scope, however, is much narrower than his title suggests: he focuses on his role as Official Historian of the 1982 Falklands Campaign. Freedman realized that the appointment (made by Prime Minister Blair), however seriously he approached the task, was ‘bound to put a question-mark against my integrity’, since the controversial aspects of the Campaign might mean that he would be discouraged from taking positions critical of the way in which the war was conducted. These areas included intelligence, nuclear weapons, special forces, and the relationship with Chile. Freedman then makes the somewhat alarming statement that he felt he was ‘under some responsibility to produce a comprehensive and reliable account’, as if the alternative (shallowness? unreliability?) might seriously have been on the cards.

Yet Freedman soon makes a surprising statement: “As a historian I am a bit of an imposter”. His background has been in the social sciences, and, while he never abandoned his social science roots, he states that, because of this assignment, his research methods became increasingly historical over time. As someone who takes a very dim view of sociology, and the lens through which it analyzes human endeavour, I interpreted this statement to mean that Freedman’s sociological training had to be abandoned in favour of more rigorous methods. Indeed, Freedman gives attribution to Michael Howard, his supervisor and mentor, for effecting a change in his research methods. He characterizes his research beforehand as more like ‘investigative journalism’, and he found that working with archives was a completely refreshing experience. He even reaches a conclusion with which I am in total sympathy: “I was constantly struck by the fallibility of memories and the value of documents as a check on what I was being told.” (Though of course the documents can lie, too.)

The writer offers a colourful account of the challenges he faced, most notably in the desires of the Foreign Office and the intelligence agencies to have no mention of the Chilean connection in the official history. Freedman had to threaten to resign to get his way, and the crisis turned out to be non-existent. He drew attention to what he thought were scandals (such as over HMS Sheffield, and claims about the UK’s air defence systems), but the media failed to pick them up. He makes a very insightful point that journalists are inclined to think that anything published in an ‘official’ history must necessarily be boring, and they look for their scoops in surreptitiously released material. He expresses his annoyance with books published thereafter that claim to present the ‘true’ history, when it is apparent that the authors had not even read his compilation.

Overall, Freedman comes across as a very humane and wise analyst of this realm of human conflict. He wonders how the loss of written testimony, replaced by telephone calls, email, and social media, will affect the ability of future historians to carry out their task. He makes the important point that, while ‘individuals are prepared to take credit for the positive, there is no need to let them off the hook when considering the negative’. (Is that an anti-sociological stance?) He respects the unique position he was put in, and ends his address with an excerpt from an earlier lecture:

The historian can illuminate the context in which decisions were taken: identify the factors that were given excess weight and those that received too little; report on the effects of those decisions; and note their unexpected consequences. But this still needs to be done with a degree of humility, as such work is undertaken without the burdens of responsibility.

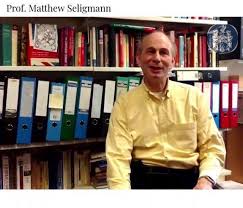

Commissioning Official History versus Paying for Official History by Matthew S. Seligmann (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533031) *

Matthew S. Seligmann’s article is somewhat of an outlier in this collection, since most of the events it covers took place over a century ago. One might assume that the government approach to historiography, the availability of sources, and the expectations of a thirsty public would have changed considerably in the period since. Seligmann, a renowned historian of naval matters, is Professor of Naval History at Brunel University, and chose for his contribution the saga of the conflict between the Royal Navy and the Cabinet in the wake of World War I. The Admiralty had strong views about the need for a comprehensive official record of its achievements, but encountered resistance from the Exchequer as its demand for funding extended into the 1930s.

Professor Seligmann has created a fascinating and elegant narrative, despite a tendency to drop into unscholarly jargon occasionally (‘image-wise’, ‘topic-wise’). He puts his finger on the problem early: “Its [the Admiralty’s] own role and experience needed to be recounted in a manner that added lustre to its reputation.” It had agreed to the commissioning, by the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID), what turned out to be a five-volume set titled Naval Operations from Sir Julian Corbett, and, after Corbett’s death, Henry Newbolt. When Corbett, in the third volume, cast doubts about the judgments surrounding the Battle of Jutland, the Naval Lords took objection to the usurpation of what they had considered was their history, and demanded that the heading on the title be changed from ‘Official History of the War’ to ‘History of the War’. They pinned the blame on the CID for encouraging views that were hostile to the apparently unanimous opinions of the Lords themselves.

It was too late to do much about it except grumble, so instead the Admiralty started production of a series of fifty pamphlets that explored different aspects of naval warfare, as carried out in the years 1914-1918. As Seligmann writes:

The rationale for the series was to get the hard-won wartime experience on specific technical questions written down and recorded before the people most closely involved in these specialist but important questions were demobilized and their expertise lost to the service. In that it succeeded admirably, and the sequence was frequently cited within the Navy as authoritative. Yet in this project, the Admiralty committed itself to an extensive and expensive undertaking that made further and further demands on the Treasury, accompanied by a certain amount of deception about deadlines. In 1921, a new section, called the ‘Monograph Section’, had been set up in the Training and Staff Duties Division specifically to produce these items.

Seligmann covers the evolving disputes at length, but I wonder: perhaps a misjudgment was made concerning the existence of these items as ‘official history’? It seems to me that an internal Research function, incorporating the lessons of both success and failure, should have been an essential component of any fighting force. The Admiralty could have engaged upon this effort without the added effort and cost of making the output of the exercise polished up and beautified for public consumption – and indeed for that of any hostile powers. There must have been a security aspect to the whole project that appears to have been overlooked. Seligmann approaches this aspect only in the final sentences of his article, where he quotes an anonymous Admiralty letter from 1929 that includes the following passage:

Here it may be mentioned that this material [Staff Monographs] is not dealt with by the Historical Section, CID, whose function is rather to produce a history for the general public, whereas the Staff Monographs will provide technical history for the study of war problems.

Seligmann’s conclusion is that “In effect, for the Navy, official history meant history that they produced themselves. It was for this reason that they fought so hard for it to be funded.” Yet I sense that that final judgment overlooks an important point.

Politics and the History of British Intelligence in the Second World War, 1969-1990 by Declan O’Reilly (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533028)

This is a long but largely uncontroversial article: I shall not spend much time on it. It has much of historical interest, in showing how the Cabinet Secretary, Burke Trend, in 1969 set in motion the process by which the government tried to regain control of the narrative concerning the role of intelligence in World War II. While the gathered luminaries all believed that it had been a significant factor in eventual victory, too many stories were appearing in the media, as well as abroad, that distorted the truth. Trend reminded his audience that all the official histories of the Second World War were deficient because they ignored the intelligence dimension completely. Yet the government was inhibited by the fact that MI5 and MI6 were not officially admitted to exist, which would make any potential disclosures embarrassing. As O’Reilly writes:

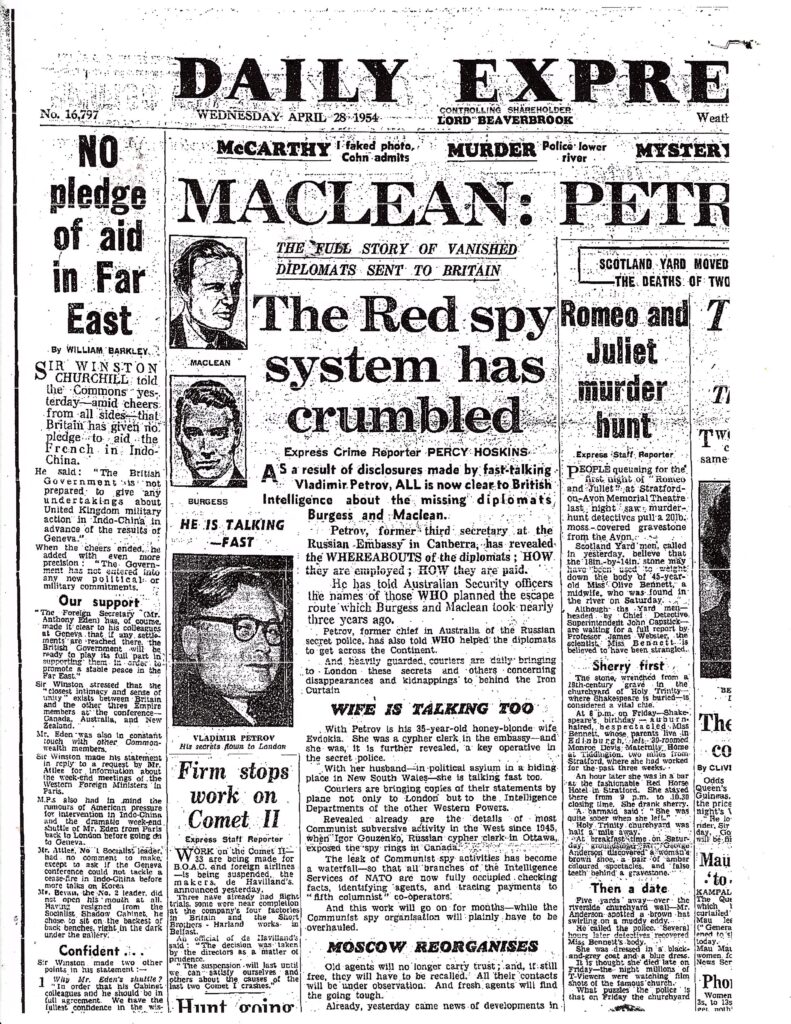

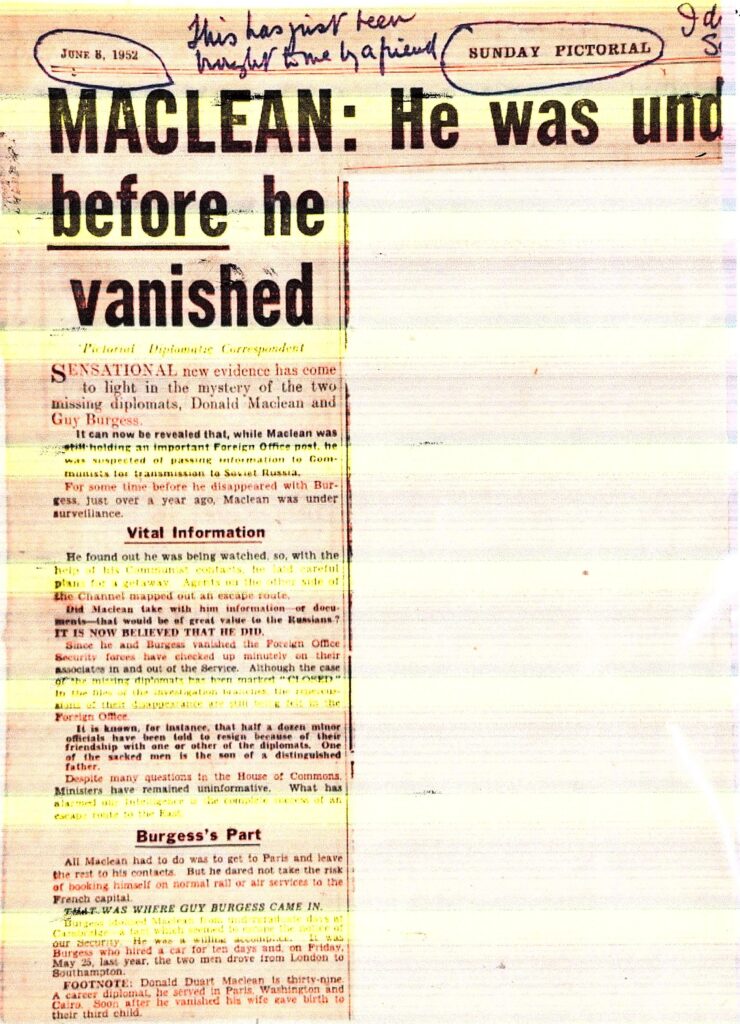

Conceived as part of an existing ‘counterblast’ strategy – restricted disclosure of classified material to selected authors, which aimed to win back public trust in a secret state badly damaged by the spy scandals of the 1960s – the underlying purpose of promoting any history was not openness but damage limitation and information control.

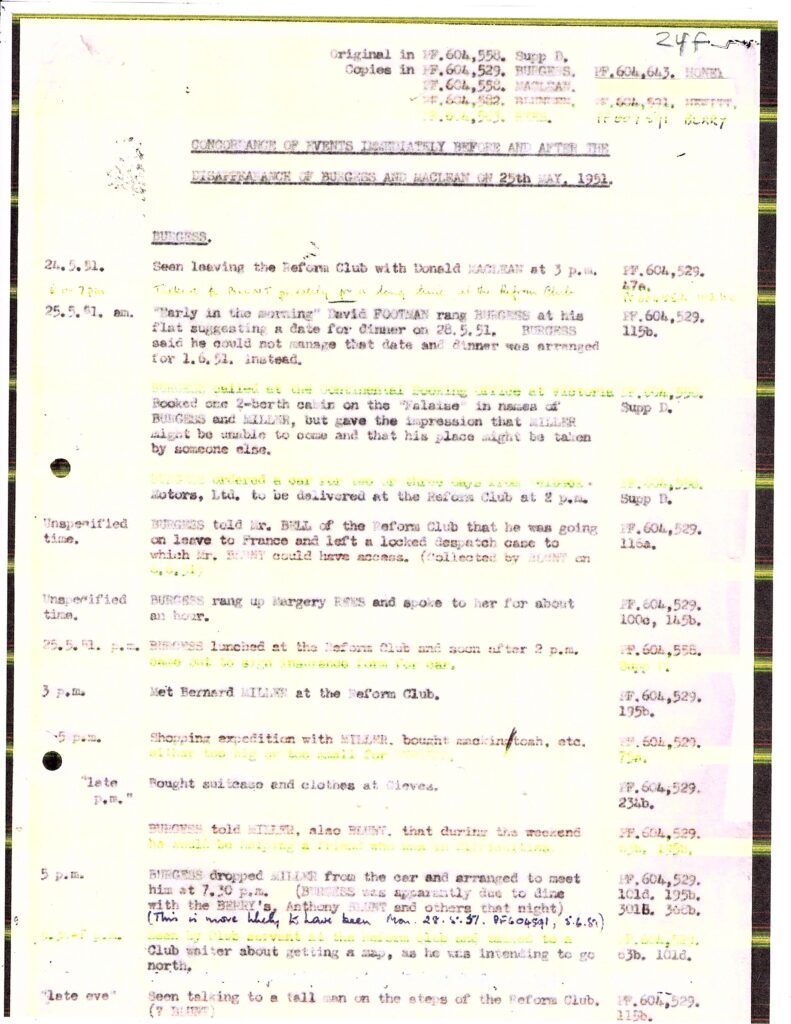

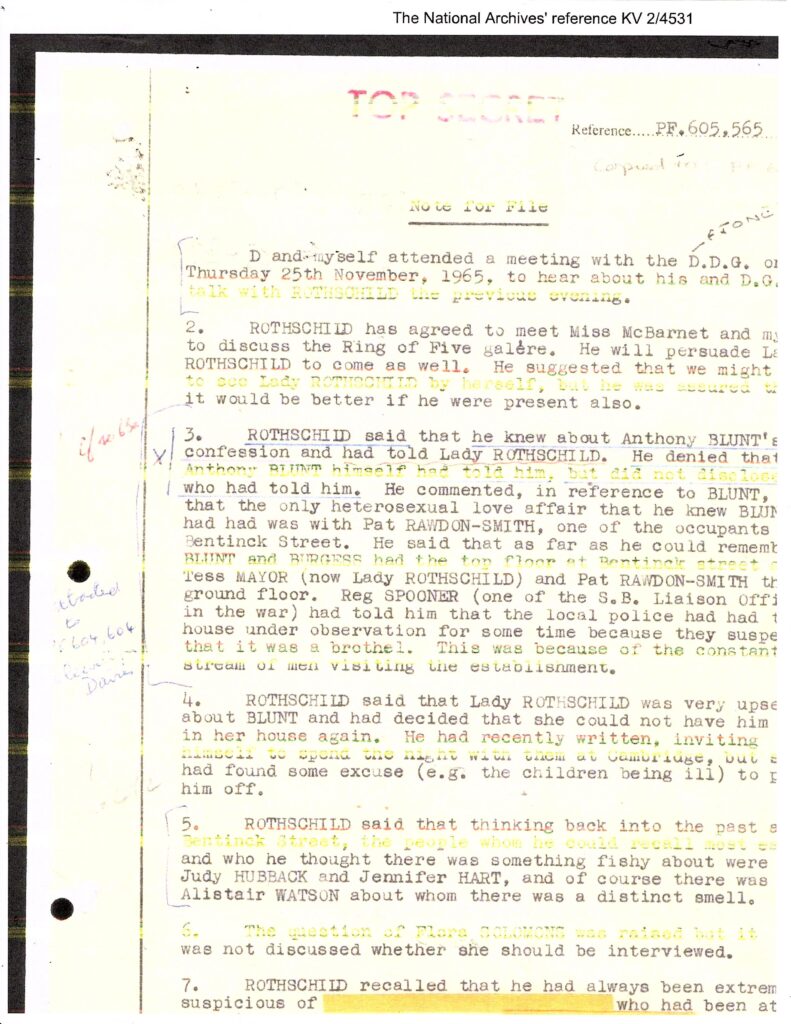

I am not sure what O’Reilly’s particular qualifications are to allow him to be an expert in this area (his bio states that he was trained as an economic historian, and holds degrees from the University of London and Cambridge), but he has done his homework, even if his judgments are cautious. Would opening up about Enigma and Double Cross be adequate to compensate for the embarrassments of the Cambridge Spies (with the shocking news about Blunt’s pardon coming along late in the project)? In any event, the mission was clearly one of propaganda, and the team wanted a ‘reputable’ (i.e. ‘safe’) historian: there were apparently ‘disreputable’ historians lurking around, anxious to get their hands on the files. Many outsiders had been pressing the government to change the moratorium on public access to papers from fifty to thirty years, which event happened in 1967, and all papers up to 1945 were to be released en bloc in 1972.

The moves by Winterbotham (on Enigma) and Masterman (on Double-Cross) to publish what they knew added further pressure, and Dick White was asked to provide a paper on how the government should proceed – which he did in 1969. Again the belief was that only an Official History could set the record straight, and White argued that it was necessary to restore the reputation not only of British Intelligence but also of security. And thus the project got under way: there were problems of confidentiality of names, of funding, of consultations with the Americans. Heath took over from Wilson, and had to review everything. A steering committee was set up. Potential authors had to be vetted. The next stage was to find ‘reliable and trustworthy historians’ – chaps who would get the story right. The clear front-runner was Harry Hinsley, former Bletchley Park codebreaker, and Professor of Industrial Relations at Cambridge. MI5 and GCHQ agreed to allow properly vetted researchers access to their files: MI6 refused.

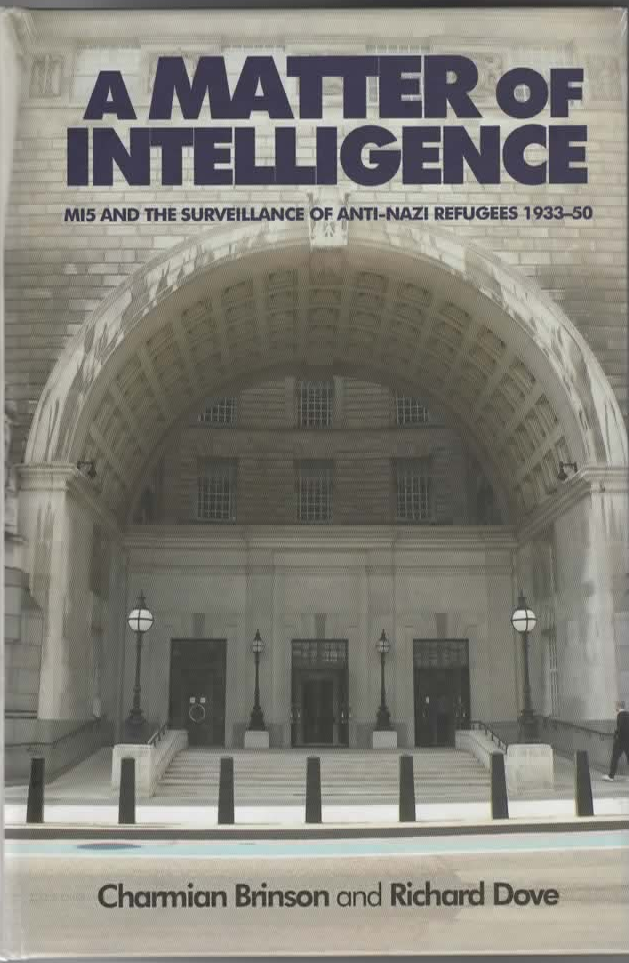

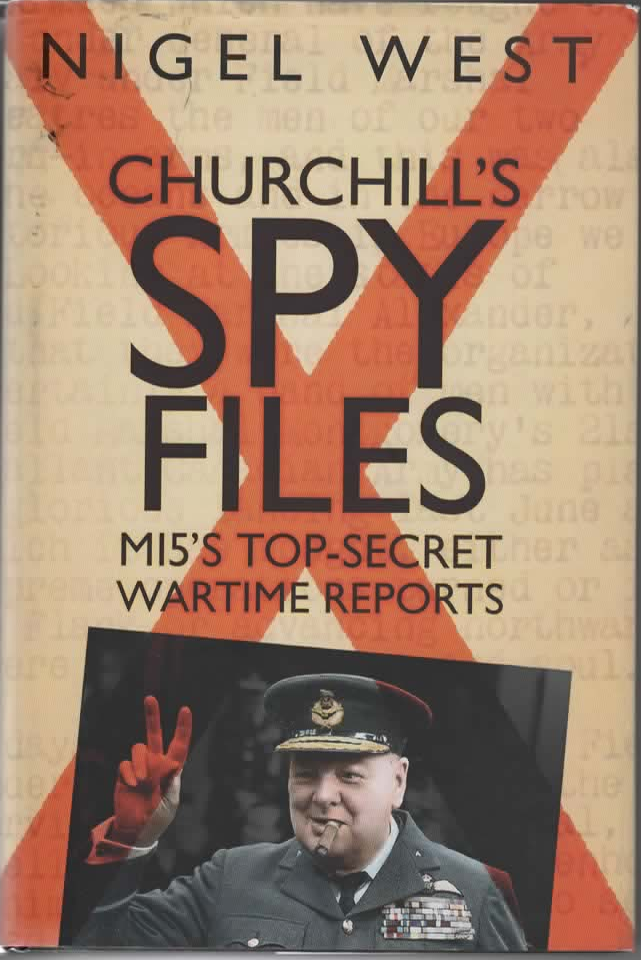

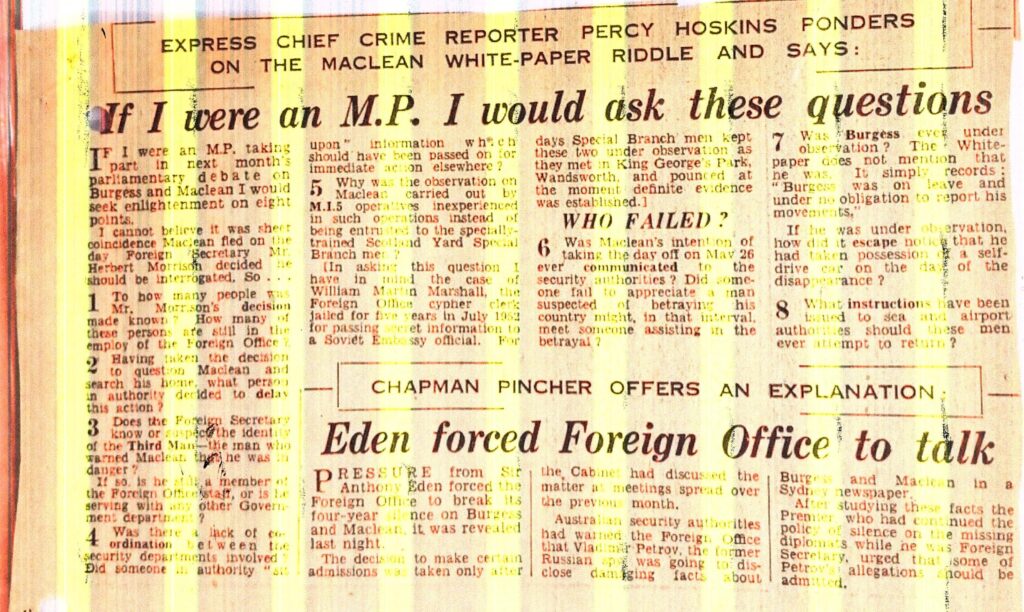

Callaghan replaced Heath in 1977: the first two volumes were ready to print. Some sanitisation was required. Then Margaret Thatcher, as leader of the Opposition was consulted: she was not keen on the undertaking, and she would in fact cancel part of the project when she became Prime Minister. In 1979 the first volumes were published – to a mixed reception. While many praised it, others demurred. The role of the Poles in cryptology had been overlooked; the Notes were inadequate; Maurice Oldfield, former head of MI6, dubbed the work ‘a book written by a committee, about committees, for committees’. Thatcher’s obduracy concerning Volumes 4 and 5 was intensified by her embarrassment at having to own up to the Blunt fiasco. It meant that bootlegged versions of the story came out from Nigel West and Chapman Pincher. O’Reilly’s conclusion is equivocal: he recognizes the difficulties of delivering such a work, but regards it as ‘a vital contribution to the historiography of the Second World War’. Whether it achieved its goal of restoring the public’s confidence in the British intelligence services is dubious, as reading the full work was a specialist task, and the airport bookstalls were laden with more sensationalist offerings that named names.

‘Utterly Unrestricted Access’: Some Thoughts on the Writing of the Authorised History of the Secret Intelligence Service by Christopher Baxter & Mark Seaman (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533021)

This article consists of separate contributions by two researchers who assisted Keith Jeffery in the production of the authorized history of MI6, Christopher Baxter and Mark Seaman. They are ‘writing in a personal capacity’, a statement that calls out for elucidation *. Seaman’s other article was incidentally written ‘in a private capacity’. Both writers pay due respect to Jeffery’s leadership skills, professionalism, command of the material, and attention to project deadlines, all of which was sadly put in context by the historian’s premature death from cancer in 2016. Baxter states that Jeffery ‘was a stickler for fact-checking and getting to the truth’, although one might point out that any historian who did not possess those characteristics should be considered a charlatan.

[* On December 12, 2025, I submitted a question via the Taylor & Francis website, as follows:

Could you explain to me the policy of describing authors as writing in a ‘private’ or ‘personal’ capacity, please? In the latest edition of Diplomacy and Statecraft you have Seaman writing in a ‘private ‘ capacity, and then Baxter and Seaman doing so in a ‘personal’ capacity, but do not extend this description to (say) Comer or Bennett, who have both retired from their government positions. Should we readers assume that, if no such rubric is offered, the writers have had their articles approved by their current or previous employer?

I have not received any acknowledgment, let alone a reply.]

Baxter (who worked as a government historian at the Cabinet Office before joining Jeffery as chief researcher) offers a largely uncontroversial account of the project. He emphasizes (as does the title) the notion of ‘Utterly Unrestricted Access’ to SIS archives over which Jeffery expressed such confidence when he received the commission. Baxter sets out to endorse this notion by asserting that ‘nothing was ever denied to me when I asked for it’. Yet that is rather a weak declaration. It explicitly states that the archives were not directly accessible by the team. And how would a researcher know what to ask for without an Index to sources? As Gill Bennett recounted, surprises occurred when a trove of documents suddenly turned up. Baxter’s claim implies a greater level of knowledge that neither the researchers nor the MI6 staff could make claim to.

Another point worthy of mention is the official historian’s direct exposure to the documents. Baxter makes the statement that Jeffery was uninfluenced by anyone when he marshalled the evidence ‘to tell the story as he saw it’. “It was Keith’s interpretation of the sources he had in front of him alone”, he writes. Yet earlier he relates how Jeffery could ‘not read every single file’, and had to rely on his team to present the material he needed in the best format available so that he could meet his deadlines. This disturbs me not a little: having a team of research assistants sounds great, but I am a strong believer in the historian working at the coalface him- or her-self. If that is not achievable, it suggests to me that the scope of the project is too vast, as indeed a single-volume history of MI5 or MI6 certainly is. John Lukacs wrote about Five Days in May, and my Misdefending the Realm concentrates on twenty-two months of MI5’s history. I believe a comprehensive single book could be written on the activities of MI5 in 1951 alone in order to perform justice to the subject.

Jeffery’s policy was to tell the story from the documents, in the belief that they held the facts. This was perhaps a trifle naive, given how we know that untruths may be sprinkled in official documents to mislead posterity, and controversial items omitted. Yet that tight policy also meant that he did not try to exploit the occasional memoirs that had been written (in flagrance of the authorities) by former MI6 officers. Nevertheless, Baxter describes the process of discovery as being fairly dull, with few ‘Wow!’ moments. He makes the point that most MI6 officers were of low calibre, having failed to make a success of their first career – which casts an ironic twist on the reputation that Britain’s Intelligence Services was supposed to have in the Kremlin. He also stresses that MI6 did not analyze the information it collected, apart from annotating the probable reliability of its sources, leaving it to its customers to perform the tasks of integration and interpretation.

Baxter does not bring up the charge that was made concerning the activities of Kim Philby, who is only sketchily covered in the work, although his treachery was sharp and effective through the year 1949, when the History comes to a stop. Yet Jeffery strongly believed that his work was not ‘the final, definitive record’ and openly ‘anticipated’ (perhaps ‘hopefully expected’) the day when the closed records might be available for others to scrutinize. (Indeed.) He made little use of foreign sources, largely because of the pressure of time, so there is no doubt that a fuller story could be told – and we can look to Stephen Dorril’s massive and informative MI6 to start with. Baxter says nothing about that work, reflecting the general coyness that dominates this collection. He concludes: “I hope that ‘MI6’ remains a standard text for scholars or future generations working on the history of SIS during this period.” Well, up to a point, Lord Copper. Anyone wanting to work on the history of MI6, and expand on Jeffery’s important platform, will need to see those original documents.

His partner’s contribution is a typical Seamanesque affair, containing some useful insights accompanied by idiosyncratic judgments that do not reflect well on his stature. Overall, Mark Seaman’s aim is to show that the execution of the MI6 project was a model for others to follow, and that he himself played a large role in its success. He starts off by explaining that several structural options were considered as to how to tackle the vast subject, with an initial idea being the assignation of chapters to individual historians dealing with specific topics/narratives. “It was envisaged [‘by whom?’ might one ask] that a team of authors would be given access to the relevant parts of the closed SIS archive in order to research their particular subjects”, he writes. Well, that was obviously not going to fly (although Seaman does not comment): the last thing that MI6 wanted was a group of nosy academics let loose among their precious records. Another option was carving the study into two, but SIS’s senior management wanted a single volume written by one author, to make the book more appealing, and ensure that it would be published as part of the centenary celebrations. ‘History as celebration’, and the old software credo of ‘deadline-driven design’.

Seaman applauds the choice of Keith Jeffery, and avers that the securing of Dr Chris Baxter as chief researcher made for a formidable team, including Seaman himself, of course, and supported ‘by a selection of part-time, in-house researchers’. Does that mean they were all MI6 employees – apart from Gill Bennett, whose professional home we know? Seaman coyly does not say, but it would be interesting to know under what constraints they worked. He describes how it was Jeffery’s intention to write the book ‘primarily based upon what he discovered in the SIS archive’, forgetting that Jeffery did not actually make any ‘discoveries’ himself. Seaman then makes the extraordinary statement that ‘the prospect of being given unique access to the closed records would have had any right-thinking historian salivating’. On that, he is 100% wrong. Any right-thinking historian would have had severe misgivings about his professional integrity’s being jeopardized by being granted the freedom to inspect, analyze, and judge confidential material that he could not cite, and presumably would have to ‘forget’ for the rest of his or her professional career.

Jeffery’s preference for using the archives, almost exclusively, was challenged by Seaman, who wisely judged that external material could have provided much context, and filled in some of the gaps. Seaman was overruled, mainly in order to keep the project on schedule. “Expanding the research field would have imposed extra demands on limited resources . . .”, he writes (of course, no resources are ‘unlimited’). Seaman came to the rescue in other ways, however. He dealt with the sensitivity review group, some of whose members did not care for the negativity of some of Jeffery’s text. “We were quick to respond that such observations from our colleagues did not fall within our brief”, he records, thus perhaps unwittingly betraying the fact that he was indeed an MI6 insider.

Seaman spends considerable time on the issue of anonymity of participants in the history. Jeffery wanted more exposure, but MI6 management was cautious, imposing restrictions that had not been laid out beforehand, much to Jeffery’s chagrin. Seaman categorizes it as ‘a truly regrettable episode’. Otherwise, the project was a great success, in his mind, and he makes a contrast with the delivery of the work compared with other Official Histories that have failed to be delivered on time. (I noted in Seaman’s other article a sly dig at Michael S. Goodman and his history of the Joint Intelligence Committee, where he wrote, in Note 21, that the second volume ‘was due in 2024’. Tsk! Tsk!) Seaman’s conclusion is that the successful setting and management of parameters for the MI6 project allowed it to avoid the kind of complaints that were expressed by Andrew and Ferris over what they considered restrictive practices imposed on them in their respective efforts. He explicitly suggests that future ventures into authorized or official history adapt the techniques that Jeffery’s team adopted. Of course, if Jeffery were still alive, he might voice complaints about the way the promise of the closed records was never fulfilled, and that the results of his hard work were not verifiable by his peers.

Behind the Enigma: How GCHQ’s Authorised History Appeared by Tony Comer (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533023)

Tony Comer was appointed in-house historian at GCHQ in 2009, and retired in 2021. He is not, however, introduced as writing in a ‘personal’ or ‘private’ capacity, so his views must presumably reflect official doctrine. Comer did have close involvement with the GCHQ centenary in 2019, and was integral to the evolution of the project that commissioned John Ferris to write the authorized history of the service. His contribution shows that he had watched carefully the experiences endured in the compilation of the histories of the sister services, MI5 and MI6, but I found his arguments a little wanting as far as objectives and implementation were concerned.

For instance, Comer claims that he noted the adverse reaction that Christopher Andrew’s repeated sourcing of information to ‘Security Service Archives’ in his Endnotes to his history, and makes the rather melodramatic comment:

There seemed to be almost an insinuation that unless a reviewer could, as it were, ‘see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and put my hand into his side’, then the texts quoted were without value.

Yet the complaint was not because a reviewer might be incommoded. (After all, a reviewer might not be a trained historian.) It was because any conclusions that Andrew made were essentially unverifiable. Other historians could not inspect the sources when they came to treat the same subject matter. The author follows up by stating that this phenomenon was in contrast to the way that ‘a mythology of Sigint at Bletchley Park during the Second World War had grown up and persisted despite the release of records which demonstrated that the myths were without foundation.’ What mythology he refers to, or who created it, and how it was demolished, are not clear: this passage could have benefitted from some more insightful explanation.

In any event, I note some discrepancies in the descriptions of the processes. In the Foreword to Behind the Enigma, Jeremy Fleming, Director of GCHQ from 2017 to 2023, wrote: “For those who want to research further and form their own conclusions, we are also releasing the source material to the National Archives.” Ferris wrote, however, on page 6 that ‘most of the material I used will be released to the National Archives after this book is published, though some files will be retained, and others redacted to varying degrees.’ Moreover, I cannot see, in Ferris’s Endnotes, any reference to unidentified GCHQ files, yet, at the time of publication, many of his references had not been revealable, according to what he and Fleming said. It would have been useful for Comer to have sorted out these puzzles, and to have informed his readers what the true state of the game was.

Comer’s next major assertion is that GCHQ’s aim in authorizing a history was to create a story ‘which would show how the intelligence produced by GC&CS/GCHQ had made a difference’. That decision was made in the wake of the actions by the former NSA contractor, Edward Snowden, who had leaked a vast number of documents that suggested that GCHQ wilfully invaded citizens’ privacy and their civil liberties. No matter how strong the outrage, however, that surely cannot be an aim of writing history. It might be an outcome, but otherwise it falls back into the realm of propaganda. As I have indicated elsewhere, I might set out to write a history of SOE with a similar objective, but end up concluding that it had overall been a disaster.

Another aim was apparently to produce an authoritative history which would show how the intelligence produced by GC&CS, and then GCHQ, had made a difference. It was a laudable sentiment, but I would counter that GCHQ, which was delivering intelligence, could not have been responsible for its interpretation, and that a historian of GCHQ alone could not judge that that intelligence made a difference. It was the job of GCHQ’s customers to integrate and analyze various intelligence (as the accompanying essay on MI6 makes clear). Certainly GCHQ’s labours did make an extraordinary difference, but I think that idea could have been expressed differently. Later on, Comer defends GCHQ’s decision to omit several categories of activity when it emphasized that it ‘was not intended to be a complete history, but one that set out to meet a particular set of aims’. That statement must nevertheless undermine how ‘authoritative’ such a work can be.

I was puzzled by some statements. Comer writes that part of the agreement was that ‘diplomatic Sigint after 1945 would not fall in scope for the book’ (something that Ferris himself made clear). Yet, in his work, Ferris made a number of vague and unsubstantiated statements about cryptologic successes into the 1950s? Were they on ‘diplomatic’ traffic? If not, what were they? And how did GCHQ know what type of traffic it was? I also disagree with Comer that an argument that claims that historians ‘should not tackle a subject knowing that their access is limited’ is self-defeating. They don’t even know how ‘limited’ it is. Unless there is a full catalogue of all archival material made, even the minders do not seem to know what is available (as the SOE article showed, when the historians’ assistants suddenly came across a file they had overlooked.) Everything should be recorded, and when an item is declassified, the appropriate cross-reference can be made. This is a point on which Professor David Dilks agreed with me: he was insistent that it occurred on his watch.

Comer agrees on this latter aspect, indicating that, when relevant material was found in the Archives (material presumably not declassified) for Ferris to work on, a record was kept so that the original material could be released after the publication of the book. He boldly and rightly voices his disappointment, however, over the fact that when material was passed on to the National Archives, it was not digitized. This is a subtle point, but important. It means that, if a researcher wants to check out Ferris references, he or she has to go to the inner sanctum at Kew to inspect the paper files. Yet one is not allowed to take a book to the reading-room, and thus one cannot compare text, notes and original sources. Has this obstruction ever been considered by any of the contributors to the topic?

[That was one of the reasons why I wrote to the Director of GCHQ, Ms. Keast-Butler, at the end of November, as I reported in last month’s coldspur. I carefully explained to Keast-Butler how GCHQ had not followed up on commitments made: for ease of accession, I reproduce it here:

“Dear Ms Keast-Butler,

I am a retired historian with a great interest in GCHQ. I read John Ferris’s Behind the Enigma when it came out, and I am prompted to write to you as I see several anomalies in the execution of GCHQ’s policy for releasing archival material that he used. (I am writing a traditional letter to you, as the GCHQ website appears to offer no on-line option for contacting anyone at the institution.) My inquiries run as follows:

- On 24 February, 2017, GCHQ announced the commissioning of John Ferris to write an authorised history and said: “We will be giving as many source documents from the history as we can to the National Archives, alongside our continued programme of releasing previously secret documents from our past.” (https://www.gchq.gov.uk/news/gchq-to-celebrate-centenary-in-2019) What is the implication of ‘as we can’? Who, or what agency, controls those decisions?

- In the Foreword of the history Jeremy Fleming wrote: “For those who want to research further and form their own conclusions, we are also releasing the source material to the National Archives.”

- In his Introduction, John Ferris wrote: “Most of the material I used will be released to the National Archives after this book is published, though some files will be retained, and others redacted to varying degrees.” Why this contradiction with Jeremy Fleming’s statement?

- However, five years after publication the only releases, so far as I can judge, appear as HW 92, consisting of twenty-five files. The descriptions are opaque, but relate mainly to Chapter 13: (HW 92/1-5 Signal traffic regarding Palestine, HW 92/5-13 about Konfrontasi and HW 92/14-25 about the Falklands Conflict), and thus ignore the bulk of Professor Ferris’s text. Why has the remainder of the material not been released?

- Furthermore, these are only hardcopy releases to The National Archives. In an article in Diplomacy and Tradecraft of September 2025, Tony Comer, who appeared to be writing with authority on behalf of GCHQ, expressed his regret that they had not been digitized. I share his dismay, as the lack of digitization means that the documents have to be inspected at the National Archives at Kew, and taking books into the reading-room is forbidden. Thus there is no easy way for researchers ‘to form their own conclusions’ (as Mr Fleming suggested) by checking the text of Behind the Enigma with the sources used. For those of us distant from Kew, of course, access is impossible unless we contract someone to photograph the files – an expensive, wasteful and inefficient process.

I should be very grateful if you could respond to my points, and especially if you could authorise a fuller release, and digitization, of documents used by Professor Ferris.”

By mid-January I had not received an acknowledgment, let alone a reply, to my traditional letter. It seemed to me that GCHQ neither has an effective PR department to deal with the public, nor does it maintain relevant in-house expertise to supply the intelligence journals with material, and it thus has to draw on retired personnel. And then an insider – he shall have to remain anonymous, but I’ll call him ‘John Cairncross’ – informed me on January 18 that my letter had not been received. I judged that non-event rather unlikely, and suspected that my missive had gone straight into the ‘Cranks’ folder. In any event, JC gave me an email address to which to re-send my letter, and I thus tried again on January 19. I still have not received any response from GCHQ, and can only conclude that it is dysfunctional.]

Lastly, GCHQ may be the loner here, but I do not think anyone should claim that ‘authoritative, top-level authorised histories’ (who judges?) are a good way of ensuring that ‘public understanding of them is underpinned by facts’. A work does not become authoritative simply because it has been authorized. And what happens when the facts change? Is the history re-issued?

Travels in the Missing Dimension: Official History and Secret Intelligence by Gill Bennett (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533022)

I have been an admirer of Gill Bennett, but I found her contribution to the series muddled, and her implicit tone of ‘we insiders know best’ a little grating. Ms. Bennett is introduced as follows: “Gill Bennett was Chief Historian at the FCO from 1995 to 2005 and worked as an official historian in Whitehall for over forty years.” Perhaps one’s perspective loses its edge after being an insider for so long. The title of her topic implicitly refers to (but does not acknowledge) the book edited by Christopher Andrew and David Dilks that appeared in 1984 (The Missing Dimension), to which Bennett did not contribute.

Her confusion dominates her first paragraph, where she highlights her long career as an official historian, including a spell between 2006 and 2010 when she was a member of the research team helping Professor Keith Jeffery in writing the official history of MI6. (That was, of course, an ‘authorized’ history, not an ‘official’ one.) She then stresses her role in being commissioned, as part of the Cabinet’s Official History Programme, to write a biography of Desmond Morton, Churchill’s intelligence adviser, as well as to prepare ‘the Historians’ [who they?] 1999 report on the Zinoviev Letter’, both of which projects involved ‘privileged access’ to comprehensive archival material. When Churchill’s Man of Mystery – an excellent book on Morton – was published in 2007 (and then re-appeared in 2009 from Routledge), its patronage by the Government Official History Series was in fact well veiled. All that Bennett wrote in a brief untitled note was that ‘the author has been given full access to official documents [how did she know?]’ and ‘the data and factual information in the report is [sic] based on these documents. The interpretation of the documents and the views expressed are those of the author’. So was her work not subject to any departmental oversight or ‘sensitivity review’ [see below]?

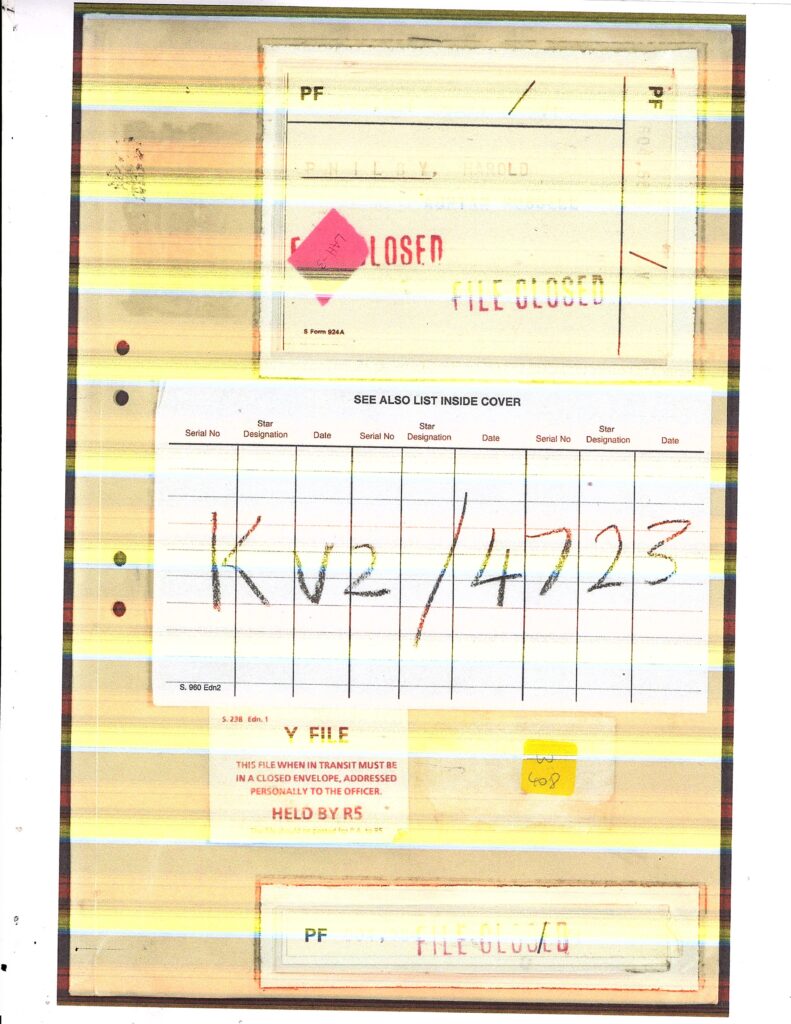

I note, however, that Bennett does not use here the phrase ‘privileged access’, but a careful inspection of her copious Endnotes indicates that she did enjoy such a benefit. Tucked among the many properly annotated sources can be seen references to ‘PUSD files’ or ‘PUSD records’, dated, but without a proper identifier, PUSD being the Permanent Under-Secretary’s Department in the Foreign Office, the interface to the Intelligence Services. This phenomenon is a precursor to Christopher Andrew’s notorious overuse of ‘Security Service Archives’ in his history of MI5, and Bennett is awkwardly coy in not explaining in her note what the conditions were. And have those papers been subsequently released? I have no idea. It would have been very appropriate if Ms. Bennett had seen fit to inform us, and, if the records she selected have been declassified, how she planned to resolve the incongruities so that other historians could check her sources. But she has selected not to take advantage of this opportunity to explain policy. (In the Notes accompanying her article, Bennett does indeed refer to the transfer of PUSD files on the CORBY (Gouzenko) case, identifying the relevant items, FO 1093/538-541 and KV 2/1419-148, but the brief reference lacks detail, and she does not address the Morton situation.)

Until that event of declassification, however, no independent historian could in principle perform the same exercise, although it would be unlikely that he or she would gain the valuable guidance around the archives that Bennett did, and such a person would not enjoy the privilege of being paid by the Government while executing the project. The outcome was excellent – a valuable contribution to intelligence history (as Professors Andrew, Hennessy and Kimball attested in their back-cover blurbs, an opinion with which I would concur), and no independent academic will attempt to revise the account, I am sure. Yet the process of internal award, government funding, personalized support, privileged access, and failure of reconciliation remains disturbing. Thus, when Bennett writes that her involvement in the writing of official history that used secret intelligence ‘has, therefore, been both professional and personal’, she puts her finger on the anomaly. No one should be able to use his or her privileged position to write personal works authorized by his or her employer, especially when that privilege has not been openly extended to other historians.

Bennett devotes a long paragraph to an explanation of why information deriving from intelligence material, involving ‘confidential and sensitive sources’, needs to be treated carefully, so that ‘a full and balanced account’ may be produced while protecting sources and methods. ‘This has been especially true’, she writes, ‘when dealing with conspiracy theories or allegations of a government ‘cover-up’’. This apology lacks any examples, and is too defensive, for my liking. Note the disdain for ‘conspiracy theories’ inherent in establishment attitudes, as if all attempts to explain outwardly bewildering ‘official’ accounts of events were inherently misconceived and inevitably faulty, an opinion that is accompanied by the implication that a breed of habitual ‘conspiracy theorists’ exists that should be regarded on the same level as worm-can openers and wifebeaters.* Moreover, Bennett puts that expression ‘cover-up’ in quotation marks, as if such an activity never happens, and she implies that ‘allegations’ of such are without exception groundless. I find that an extraordinarily arrogant opinion, and the suggestion of a need for ‘balance’ indicates a desire to avoid controversy and not ruffle any feathers. Her message is explicitly that ‘the official historians’ (or ‘Historians’?) should be trusted because they alone have the experience and insights to make the correct judgments, but who determines the quality of their work? It is a circular argument: the historians become ‘official’ because they were deemed to be trustworthy, and then they are monitored to ensure that they get the story right.

[* A few years ago, Ms. Bennett published a book titled The Zinoviev Letter: The Conspiracy That Never Dies, and she concluded that there probably was a conspiracy involving Joseph Ball and the Conservative Party. That volume appeared under her name after Foreign Secretary Robin Cook chartered her, as Official Historian, to write a report on it.]

She then diverts into a useful discussion of where important intelligence information may be found, even though not formally released by the owning agency (particularly MI6). Then follows an amusing example, where she describes the circumstances in which, when she was working on Jeffery’s team, a member of MI6 appeared in her room to inform her that he and his colleagues had found ‘a couple of boxes at the bottom of a press’, which turned out to be useful for determining how Stewart Menzies had been chosen to head MI6 in 1939. How convenient! And it just goes to show that, since complete records of the archive had not been maintained and registered, no historian – official or not – could know how ‘unrestricted’ their access to valuable information could be. Even Bennett was subject to what the minders (the equivalent of the ‘SOE adviser’ in the Foreign Office) wanted to show to her.

‘Privileged access does not mean freedom to publish’, Bennett writes, and she brings up the dreaded process of ‘sensitivity review’ (an expression that has taken on new meaning in these woke times). She gives an example of Freedman’s history of the Falklands Campaign [see above], where she was a member of the departmental committee dealing with sensitivity, but then, rather bizarrely, offers The Mitrokhin Archive, published by Professor Andrew in collaboration with Vasili Mitrokhin, where she was also a committee member. She does not explain why this volume came to her attention: it was an independently produced work, and the interest of the FCO Chief Historian would appear to be meddlesome. Perhaps, once you are an authorized historian (Andrew), everything you write is by some unknown contract subject to Whitehall review. (And does that also apply to researchers working for an authorized historian?) Bennett does not elucidate, but points out that Historians [sic!] are supremely qualified to resolve the discordant sensitivity issues that frequently arise on interdepartmental committees. Yet her involvement on both sides of the line (researcher and sensitivity committee member) appears inappropriate.

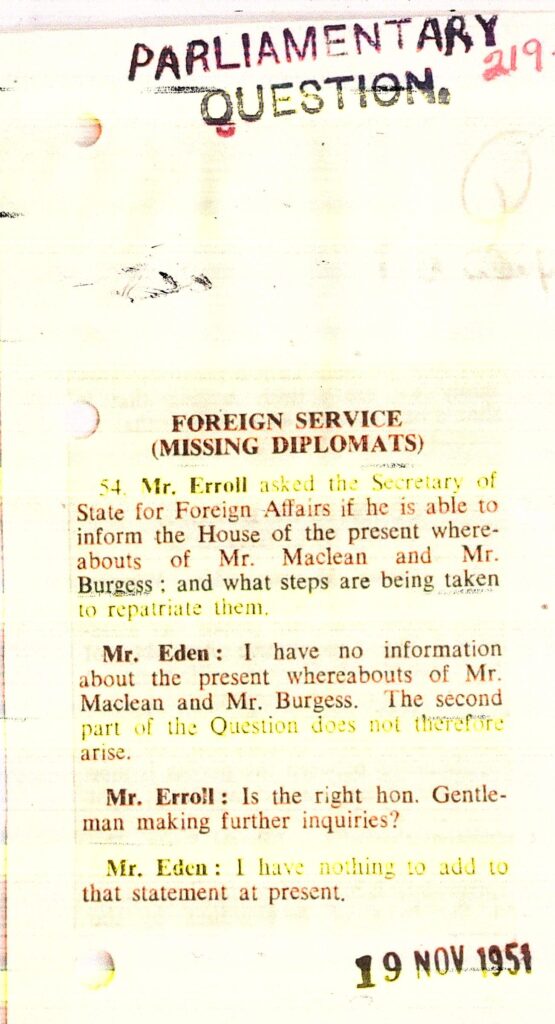

The following pages do not offer many new insights. Her account of ‘national security’ concerns inhibiting the release of some material is flabby, and I would guess the protection of professional reputations is a dominant influence. On the other hand, she makes a solid point, quoting what Foreign Secretary Robin Cook said in 1998, about the necessity of not revealing names of persons who had co-operated with MI6, since hostile nations might be ruthless in persecuting their relatives and descendants. That, to me, seems a very important reason for non-disclosure, but it has been an accepted practice for many years that essential documents could be released with certain names redacted. That policy has its pitfalls, however: careful examination can frequently make correct identifications from other sources, with no harm done. The problem is that many of such redactions were made when the files were stored away, decades ago, and the exposure is now nil. How can the originals be restored? And what about those Guy Burgess files, some retained until the 2070s because of family sensitivities, or ‘health and personal reasons’? The man had no family or survivors! Ms. Bennett could have made more of a splash by investigating such matters.

Some Thoughts on the Official Histories of the Special Operations Executive by Mark Seaman (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533030)

Mark Seaman surprisingly appears again. His contribution is a combination of important historical insight, superficial analysis, and more than one odd judgment. For some reason, Seaman, described as having been ‘an historian with the Imperial War Museum and, subsequently, the Foreign Office’ is introduced with the annotation that he is ‘writing in a private capacity’. I do not know what that implies as for the other contributions: did their articles have to be checked to see whether they complied with official doctrine? Someone once told me that Seaman was actually an employee of MI6: that may be true, but I wonder why it cannot now be declared, if so. (And see my supposition above.)

The author opens his article by apologizing for his previous ignorance as to why the official histories of SOE were written, and ascribes the enthusiasm for such projects as coming from influential former members who were chagrined that the unit was dissolved soon after the war. In an anonymously framed explanation, Seaman writes: ‘. . . . there was a belief that its heritage needed to be preserved not only out of sentiment but through a conviction that clandestine warfare had made a difference, and that lessons should be drawn for exploitation in future conflicts.’ There stand the ‘lustre’ and ‘education’ objectives that stirred the Admiralty in 1919. Yet the spheres of memoir and movies took over for fifteen years or so, with the exploits of SOE agents glamorized and often misrepresented in the popular media. Thus, although a departmental history by William Mackenzie had been written, but shamelessly not published until 2000, M. R. D. Foot was commissioned to write an official history of SOE in France in 1960, this presumably being a more manageable chunk to bite off, and also useful in countering rather unbalanced stories coming from across the Channel.

The evolution of Foot’s work had a very checkered history, which I shall not reproduce here. But I shall emphasize a point that Seaman rather disgracefully elides. He writes about the first edition having to be withdrawn (because of libel actions), and consequently republished in 1968, and that ‘a somewhat redundant fourth edition (adding little new material)’ appeared in 2002. While this observation draws a massive attention to the problem of updating an ‘authoritative’ account, whatever the subject, Seaman ignores what was a shameful episode in that edition’s creation. Michael Foot, under pressure from Francis Suttill, Jr., the son of a murdered SOE hero (PROSPER), rewrote for the new edition a crucial paragraph about the movements of Suttill’s father in 1943, yet provided no explanation for why he did so. Seaman also ignores the controversy over the ‘SOE advisers’ who over the years were offered by the Foreign Office to historians seeking archival material before it was released. Boxshall, the first adviser, did a very poor job in the cause of truth by protecting Foot from seeing original documents, and Foot was simply not demanding enough in his methods, which resulted in many errors.

Seaman proffers an erratic assessment of the historians who were commissioned to write works on other dimensions of SOE’s history. Christopher Woods, who had served with SOE, ‘possessed near-perfect credentials’, according to Seaman, but Woods was not a historian, and could not even produce a text for others to work on. Those ‘credentials’ look pretty shabby now. Other figures with a better academic profile became distracted, and could not complete their assignments. This points to another perennial problem: how should commissioned authors be remunerated, and were they expected to carry out their current obligations as well as perform the research and writing required for the official assignment, in the belief that honour and renown would compensate for the stresses? In any event, while these messes were continuing, a large batch of SOE archives was transferred by MI6 to the National Archives, which opened up a vault of information to be used by independent historians.

His conclusion, however, stirs up rather than resolves a debate. “There surely can be no necessity for further SOE official histories”, part of his argument being (for example) that the hundred or so documents still held by MI6 ‘would surely only provide supplements to the detailed picture we already have’, and he compliments Roderick Bailey on his history of SOE in Italy, and Knudsen Jespersen’s work on Denmark (not an official UK government publication, of course) as filling out the story. What Seaman does not mention here is his declared belief that it was the publication of Francis Suttill’s Shadows in the Fog was ‘the last word’ that effectively closed the door on the need for any future study – a scandalous observation. There are no ‘last words’ in history. Readers should return to the challenge that Patrick Marnham and I threw out to the editor of the Journal of Intelligence and National Security back in 2023, visible at https://coldspur.com/special-bulletin-prosper-the-letter-to-jins/. Instead of defying anyone to provide an objective re-assessment of the history of SOE, if Seaman were a proper historian, he would be exploring mechanisms whereby published ‘definitive’ or ‘authoritative’ histories could be updated without the complexity of costly new editions which few would want to buy. I shall return to that dilemma in my Conclusions.

On Writing an Official History of SOE in Italy by Roderick Bailey * (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533020)

Roderick Bailey’s contribution is a very straightforward and honest assessment of his experience as an official historian (although there appears no annotation that he is writing ‘in a personal capacity’). In 2014, his second book Target Italy: The Secret War Against Mussolini’s Italy 1940-1943, was published by Faber and Faber. The fact that this volume addressed only part of the duration of the war has a strange history: Bailey records the now familiar story of Christopher Woods’ failure to provide a usable manuscript, although Bailey makes a similar misjudgment in stating that Woods’ experiences ‘fitted him well for the historian’s role’, overlooking the fact that lack of historiographical training, but simply being close to the action and having an enduring interest in the subject, was not an adequate qualification. When Woods had to abandon his project, it was split up into two, with Professor David Stafford being charged with writing about SOE’s activities in German-occupied Italy between 1943 and 1945, and the task of recounting the story of SOE in Italy between 1940 and 1943 being given to Bailey himself.

I believe Stafford’s work merits a short aside in its own right. The reader would not suppose that the work is an official history after looking at the covers or the preliminary pages. Indeed, it is not until page xvii of the Introduction that Stafford states that ‘this is an official history, commissioned by the Cabinet Office, and the sixth about SOE to appear in print’. It does not seem that the Cabinet Office was anxious to promote the book in any way, and no listing of the previous five appears within to satisfy the interested reader. It all rather pours water on the notion that commissioned authors would gain renown by having their names linked to such an authority. Stafford does, however, point to an important statement not recorded elsewhere in this collection. He cites what Cabinet Secretary Sir Norman Brook wrote in 1953 to Sir Edward Bridges, head of the Civil Service, that the official historian’s duty was ‘to give an exact and truthful picture of events’, and he reinforces that opinion by citing the general editor of the military series, Sir James Butler, said that the historians should provide such a picture ‘giving honour where honour was due, but not disguising failure.’ No lustre for lustre’s sake, or unqualified celebration, then.

Bailey then moves on to describe his experiences. He had some praiseworthy goals, primarily to make sure that foreign (i.e. Italian) sources were properly exploited, the failure to do so being a marked characteristic of earlier histories. He hoped that bearing the stamp of ‘official history’ might help in adding ‘authority to particular challenges to long-standing allegations in Italy about the British Government’s past actions there’ – a controversy which this reader wishes he had explained in more detail. He was promised that familiar bromide of ‘unrestricted access’, yet discovered that access to official material was much more restricted than he had expected. Some files had not been released to Kew, and he had to inspect some personnel records ‘in the secure surroundings’ of Admiralty Arch. When he wanted to investigate the relationship between SOE and SIS during the early days of the war, he was stymied largely by the obstructions put in his way by MI6. He was let down, after promises had been made that the papers of Max Salvadori would be released, by the decision to withhold them. Bailey is an ardent believed that the sources of official historians should be accessible by other historians, so that they can verify the initial accounts. His judgment of the in-house review of his work, however, was that it was ‘wholly positive’.

The other major disappointment felt by Bailey was the matter of payment. He writes: “The arrangement for official SOE histories was that authors should receive no fee but should be allowed to secure their own publishers and benefit from whatever advances and royalties their books might provide.” That sounds a rather mealy-mouthed statement of policy, but might explain why SOE histories were put in a class of their own by Professor Salmon and Smith. They were unfavoured stepchildren, who had to be encouraged vaguely, but who did not gain the necessary endorsement and support that someone like Gill Bennett enjoyed. Thus Bailey (self-employed) had to hustle around to gain charitable support to fund his trips overseas to perform the research that he justifiably deemed was necessary to do the job properly. He admits that he should have been more wary, and perhaps more demanding, when he agreed to the engagement.

Lastly, Bailey politely rejects the somewhat airy remarks concerning commerciality that Sir Joe Pilling wrote in 2009 when he reviewed the Official Histories Programme. Pilling advanced the questionable notion that a subject should not be excluded from the programme simply because ‘fewer people are likely to want to read the book’, and continued by making some conclusions as to how public opinion might be shaped by a book that had ‘several thousand readers’ and was broadly reviewed. Whether Pilling was implicitly recommending public subsidy in the cause of truth and discourse, or whether he was suggesting that histories designed with ambitious sales prospects (and the risk of such volumes becoming airport bookstall fodder) is not clear. Yet it would seem that the government might prefer to enjoy the cachet of opening up strategic historical areas (and also controlling the process), while delegating the commercial risk to the private sphere. After all, it can maintain pretence to ‘officialdom’ only if it allows restricted access to secret archives by its preferred historians that is not allowed to others.

SOE in France: Revisited by John Peaty (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592296.2025.2533029)

After the appearance of Mark Seaman’s article, further attention to SOE in France might appear superfluous. Were there not other subjects worthy of analysis, such as Andrew’s history of MI5, which merits hardly a mention in this anthology? John Peaty is introduced as an ‘independent scholar’, one of a magnificent troupe to which I would claim membership, although Mr Peaty has far more letters after his name than I. His qualifications appear to be the fact that he ‘is a life member of the Institute of Historical Research’, and ‘is retired from a long and varied career in Government service, including several years at the MOD in Whitehall’. His choice was to re-visit ‘a ground-breaking and controversial government history’, namely Foot’s ‘authorized [sic!] history of SOE in France.

Peaty offers a beguiling paragraph concerning the actual status of SOE in France, referring to Foot’s claim in his Preface that, while the book had been prepared under official auspices, it in no way reflected official doctrine. (The questions of whether any such doctrine existed, or whether Foot knew what it was, were ignored.) Peaty continues:

Later he called it ‘quasi-official’. Before publication, the Cabinet Secretary [the normally razor-sharp Burke Trend, performing his best Sir Humphrey imitation: coldspur] informed the Prime Minister Harold Wilson that it was not an official history ‘in the full sense of the term’ as it was not written by a team or subjected to departmental scrutiny but rather ‘a companion volume to the official histories’. Nevertheless, it was part of the government’s series entitled ‘History of the Second World War’, and there was never any doubt about its official status.

Is that quite clear, everybody? Did you get that, Harold? What say you, Gill Bennett, with your solo, non-scrutinized book on Morton? It is all quite amazing.

The description of the evolution of SOE in France does not really cover new ground: C. J. Murphy wrote an extensive article about it in Historical Journal in 2003, which Peaty cites. The account of the review of Foot’s draft at the end of 1962 has an amusing side: “It was then read by various authorities and its publication authorised”, writes Peaty, continuing: “The draft was then set up in galley proof and circulated to eminent and well-informed people”, their review generating some textual changes. Given the lawsuits and expensive rework that resulted from the book’s appearance, it would be interesting to know who all these ‘various authorities’ and ‘eminent and well-informed people’ were. Peaty does not identify them, but the disaster casts questions over the whole process of official scrutiny.

Peaty covers the matter of Foot’s methodology in a rather shallow fashion. He claims that Foot ‘had been given access to the surviving records’, but he completely avoids mentioning the challenge that Foot faced with the SOE Adviser, who steered him away from certain files, and – sometimes deceptively – summarized other information for him. Peaty never includes the fact that Foot was not allowed to read the internal departmental report written by William Mackenzie, and he belatedly points out that Foot was deterred from speaking to SOE staff and agents, but apparently did not push very doggedly to gain access. He cites Foot’s rather weak apology, and adds that the author made hardly any use for foreign archives. Why was that?

On the question of Foot’s overall objectivity, and whether his history consisted of a proper assessment of SOE’s achievements, Peaty lays out some trenchant questions, although he sits on the fence, and is irritatingly anonymous in his references. A relevant passage is worth quoting in full:

Did SOE agents in France change the course of the war? Was France liberated by a national uprising in August 1944? Was Foot a completely free agent? Did he have no axe to grind? Foot was an admirer of SOE, its personnel and its activities and tended to accentuate the positives (the more so as he got older). Others (both during the war and subsequently) have viewed SOE in general and F section in particular as amateurish, its security lax, its circuits easily penetrated by the enemy, its agents unable to achieve anything significant, and its losses disproportionate to its efforts.

It would have been useful if Peaty could have identified these critical sources and offered some sort of summing-up, but he does not rise to the occasion. I could add some criticisms of SOE: it was a buccaneering gesture by Churchill to want to ‘set Europe ablaze’ when Europe did not want to be set ablaze; the reprisals after sabotage and assassinations were horrendous; the attempt to arm French résistants when the re-entry to Europe was years away was futile, and much of the weaponry ended up in the hands of the ruthless Communists; many of the renowned groups of maquisards were poorly trained and ill-prepared; most of the successes that SOE did achieve could have been won by other commando-type forces. Yet to write a history of SOE that left an impression of failure and wastage would have been very unpopular with survivors and relatives who did not – and do not – want to conclude that so many brave lives had been lost in vain.

Peaty steers clear of such controversy, rather weakly stating that ‘which version of the book [the 1968 or the 2004 version] is to be preferred is a matter of opinion’, as if anyone wanting to make a judgment is going to compare both texts in detail. Of course they are both flawed, as Peaty admits, and SOE in France is ‘definitely not the last word’ on the subject. We have Suttill and Marnham (neither of whom Peaty names) to add to the mix, and a further synthesis is necessary – a part of which I have tried to address with my series on the PROSPER disaster on coldspur. Yet it is unlikely that that evolution will be shown in a fresh government-sponsored history, whether official, quasi-official, authorized, departmental, personal, or any other variety.

Finally, I noted that Peaty – who appears to be the sole ‘independent’ contributor to the forum – acknowledged guidance from Christopher Moran in the writing of his article. In my opinion, as I suggested earlier, it would have been far more productive if Professor Moran himself, the author of Unclassified, had been invited to participate in the seminars himself, and write an article. But that might have rocked the boat a bit too much.

Intermezzo

As I was completing the assessments above, my copy of Patrick Salmon’s Control of the Past: Herbert Butterfield & the Pitfalls of Official History, published in 2021,arrived. I had thought it necessary to read what Salmon had written about that renowned critic of official histories, and to ascertain how his message compared with that of his text in Diplomacy and Statecraft. In many ways, I was surprised. Butterfield’s original complaint seems to have been addressed to the fact that compilations of official documents (i.e. not ‘official histories’, as such) frequently neglected to include Cabinet Office or Foreign Office minutes. Butterfield was presumably under the impression that official minutes constitute an accurate record of what took place at important meetings. Yet, as I have learned in my recent study of the Joint Intelligence Committee (and as Andrew Robertson shrewdly reminds us in Masters and Commanders), such minutes frequently avoided the sensitive or confidential decisions made, or even distorted the truth, since the scribes on occasions preferred to record for posterity what the participants should have said as opposed to what they actually did say.

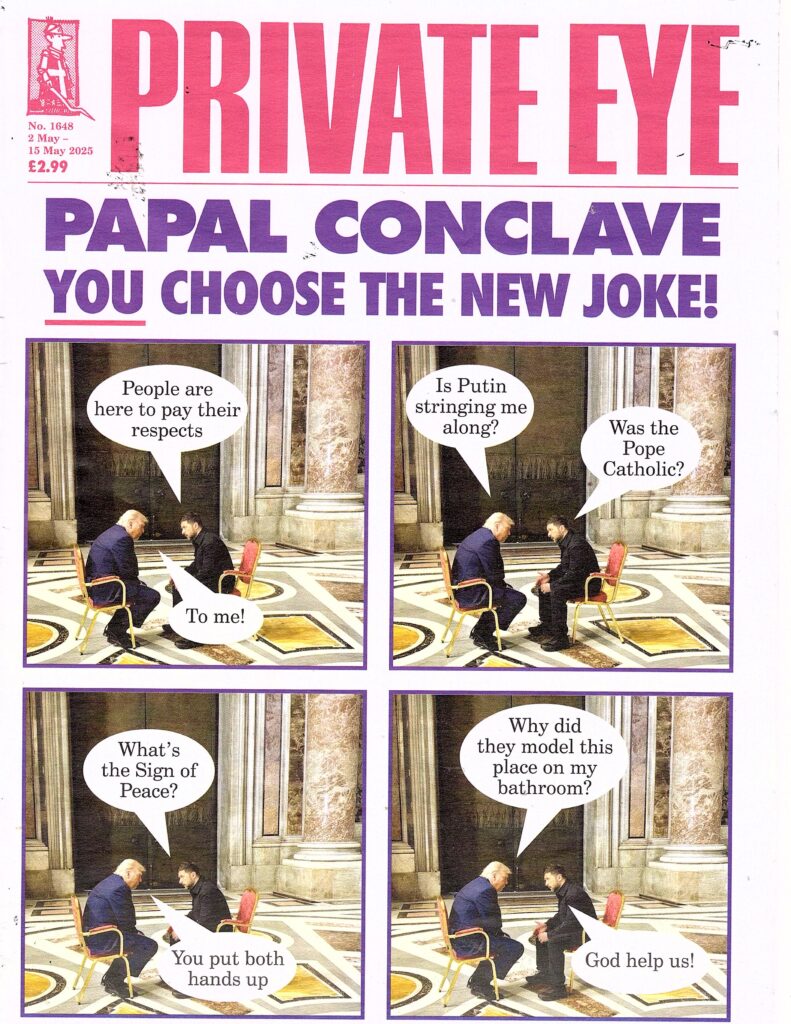

This an important aspect of historiography – the firm belief in the solidity of documents. Salmon cites a vital article by T. Desmond Williams, The Historiography of World War II, originally published in Historical Studies, and reprinted in The Origins of the Second World War, edited by Esmonde M. Roberston. The piece shows that the selectivity of collections of documents (such as government minutes) can play a large role in influencing how historians interpret events, and the run-up to World War II is a crucial example of such. In fact, the historian A. J. P. Taylor was severely called to task by his selective interpretation of German documents when he downplayed Hitler’s strategic imperatives in The Origins of the Second World War. A vigorous debate – mostly very critical of Taylor – ensued in the open press, which was as it should have been, although the circumstances were slightly tainted by the fact that much of it took place in the pages of Encounter, the CIA-funded magazine.

Salmon’s comments otherwise are mostly unremarkable, ranging from the complacency of the elite as to how the Official Histories Programme was launched in 2005:

Historians of eminence in their field are identified, after consultation with appropriate government departments, and are appointed by the Prime Minister. They are then given access to all relevant material in government archives, whether publicly available or not. The historian writes the history from his/her own perspective on the basis of the full information. Any security issues connected with the historian’s use of still sensitive material are then addressed before the manuscript goes to the publisher

through aspirational hopes, such as:

The purpose of the programme was defined in 2005, by what had now become the Histories, Openness and Records Unit of the Cabinet Office, as being ‘to provide authoritative histories in their own right; a reliable secondary source for historians until all the records are available in the National Archives’; and a ‘fund of experience for future government use’

to the more sensible but unfulfillable statements of policy, such as:

And we agree with Woodward that there always exists a check on our honesty in the fact that the archives from which we make our selection will one day – perhaps very soon – be fully open. Like Woodward, we ‘don’t want to get the posthumous reputation of a faker of history’

and the concluding righteous but clearly not adopted sentiment:

Butterfield’s second maxim – that there is a place for official history, but that it would be submitted to unremitting scrutiny – remains as valid today as it was in 1949. Official historians are still ‘people to be shot at’. And his real thrust here is that academic history – history studied for its own sake and not for any imagined utility – must remain paramount and uncontaminated by any association with government

Conclusions

“Yet there is another possible business rationale for closing the archives to outsiders in a hostile content climate. It shuts down new perspectives on the past and inhibits the production of biographies and memoirs of less branded names that would be of interest to the public, but over which the BBC would not exert control. It avoids potential leaks, content heists and future embarrassments for the corporation.” (J. E. Smyth in Who controls the past, on the BBC’s restricting access to its archives, in the Times Literary Supplement, November 14, 2025)

If I overall sound curmudgeonly on this set of articles, it is because I believe the exercise has been a colossal disappointment. A great opportunity has been missed. I judge that a mutual admiration society of mostly greying bureaucrats has been allowed to dabble around in some obviously controversial matters without any real challenge, with the outcome that they come across as being very self-satisfied. They elide over the pressing questions that could be thrown at them. The editors obviously offered little guidance on what their invitees should write about, and declined from providing insightful analysis, or even suggesting remedial actions that should be initiated. Instead they conclude with the weak hope that the special edition of the journal ‘will not only enhance our understanding of the role and value of official history but also inspire scholarly inquiry into the subject’. If scholarly inquiry could not be conducted here, where do they expect it to happen?

In my summary thoughts, I concentrate largely on the vital matter of Unreconciled Sources.

I start by presenting a quotation from Margaret Gowing’s Note on Documentation, from Volume 1 of her Britain and Atomic Energy 1939-1945, published over sixty years ago: In accordance with the practice of the official war histories, references to official papers that are not yet publicly available have been omitted: footnotes are confined to published material. The complete documentation will, however, be available in confidential print and will be accessible to scholars when the documents concerned are publicly available.

If any of that documentation has been released, I do not know how we could establish what it was, or how any of it corresponded to the absent references in Gowing’s text. What ‘confidential print’ means is obscure. (The Imperial War Museum suggest that it might hold information regarding Gowing’s use of official papers, at https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1500082073, but the information is not available on-line.)

In his Preface to Volume 1 of British Intelligence in the Second World War (1979) Professor Hinsley made a distinction between conventional government files, where, even if they were might not be available for ‘a considerable time to come’, he was able to provide precise references [an excellent practice] and those of ‘the domestic files of the intelligence-collecting bodies [MI5 and MI6, which he lists in his Index] which are unlikely ever to be opened in the Public Record Office’. He thus resolved that it ‘would have served no useful purpose to give precise references’. That implies that his team maintained them, of course. I do not believe that any reconciliation of those references has ever been published.