Contents:

Introduction

Philby’s Personal File?

Early Recruitment by MI6?

The Internment of Harry Philby

Edith Tudor-Hart‘s Files

Informers

A Theory

Litzy Feabre

Interest in the Honigmanns

Summary and Conclusions

Postscript

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

In last month’s report, I investigated how it was that the NKVD risked using Litzi Philby so energetically in espionage activities without appearing to consider that such a strategy might jeopardize the cover of her husband. I concluded that, for almost all the time that she was resident in England and France (1934-1946), she was considered a far more important asset than Kim. In this bulletin, I address the first of the two questions left over from that report, namely:

- Why were Philby’s connections with Litzi and her communist associates not picked up and taken seriously by British intelligence?

My exploration of this topic, which unearthed some startling facts, led me to some fresh conclusions, and provoked me to raise another question worthy of attention:

- How did MI5 and MI6 process the evidence of Philby’s treachery when he came under direct suspicion in June 1951?

Owing to the amount of detail in the exegesis of the first topic, I shall have to defer analysis of this subsidiary question until next month. I shall also have to hold over once more the third question: ‘What was Philby up to in Europe in 1945?’, and address it later. I shall also cover then the Sun Engraving Company, which Edith Tudor-Hart rather clumsily engaged for propaganda purposes.

I start by cataloguing all the events that could have led to, or contributed to, Philby’s exposure, from the time that he attended Trinity College, Cambridge up to his interviews and interrogation in 1951. I exclude from this list the highly important and very visible project that Philby took on to help the socialists being oppressed in Vienna in 1933, simply because it was so public and obvious. In itself, it might have been explained away as an impulsive action of exuberant youthfulness, yet it was complicated by ancillary activities that should have provoked – and eventually did trigger – severe warning signals about the nature of Philby’s true allegiances. Not all these events were internalized or recorded at the time. Some were noted by observers, but their significance was not recognized until much later.

- Treasuryship of the Cambridge University Socialist Club (1932): Philby had joined the Club in 1931. His tutor, Maurice Dobb had founded it, and it was as much the symbolism of Philby’s membership of an extreme left-wing group, as the intimacy with other firebrands, such as the openly Communist James Klugman, that could have incriminated him.

- Visiting the Soviet Embassy in Vienna (1933): E. H. Cookridge claimed that Philby had told him that he had made contact with two officials at the Soviet embassy, Vorobyev and Antonov-Ovseyenko, both of whom were NKVD agents. Cookridge apparently did not reveal this fact until he published The Third Man in 1968.

- Marriage to Litzi Friedmann (1934): Philby’s decision to marry Litzi, even out of sympathy with her plight, constituted an unnecessary step in his commitment to the Soviet cause. And his failure to disentangle himself quickly from the union would bedevil him for over a decade.

- Application to Join (Indian) Civil Service (1934): Philby’s application required references, and he sought out two Cambridge dons, both named Robertson. They drew attention to his unsuitable ‘sense of political injustice’, so he apparently withdrew his application.

- Association with Edith Tudor-Hart (1934): Litzi introduced her husband to Tudor-Hart, who was being watched by Special Branch as a communist subversive.

- Incomplete Separation from Litzi (1935): When Philby started to express to Jim Lees his rejection of Communism, his sympathy for the Germans and his need to jettison Litzi, he nevertheless failed to cut off contacts with her, or initiate divorce proceedings. (Source: Lees’s correspondence with Seale and McConville.)

- Litzi’s travel around Europe (1934-1938): Philby’s interrogator of 1951, Helenus Milmo, revealed that MI5 had tracked Litzi’s movements during this period very closely, although it is not clear whether these were recorded at the time, or harvested later.

- Sudden Switch to Fascism (1936): Philby’s joining the Anglo-German Fellowship was a sudden and surprising volte-face for someone of avowed communist leanings. This move would later be questioned by Archer, Martin and Bagot when Philby was being considered as a possible future chief of MI6.

- Invitation to Flora Solomon (1937): Philby revealed to Flora Solomon that he ‘was doing important work for peace’, and invited her to join him. She declined.

- Funding for Spain Venture (1937): Philby could not have afforded the expenses of living as a free-lance reporter in Spain. He later lied about the source of funds to his interrogators.

- Assurance to Erik Gedye (1937): From Spain, Philby sent a message to his friend Eric Gedye to re-assure him that his leftist allegiances had not changed. Gedye apparently revealed this fact to Seale & McConville only after Philby’s escape.

- Litzi’s Drawing on Philby’s Bank Account (1937): Milmo wrote that Litzi had no money to support her travels, and was using her husband’s bank account to the tune of £40 per month.

- Interrogation of Tudor-Hart over Camera (1938): In 1938 receipts for a Leica camera used by the Percy Glading group to photograph documents stolen from Woolwich Arsenal were made out to Edith Tudor-Hart. This showed that the Austrian Communist cell was not a purely intellectual group, and Philby could have been linked through Litzi to its felonious activity.

- Introduction to Aileen Furse & Cohabitation (1939-1940): Flora Solomon introduced Philby to Aileen Furse on September 4, 1939, the day after war was declared. They met again, and Aileen and Kim decided to cohabit, when Philby returned from France. Since Philby declined to divorce Litzi, Aileen changed her name by deed poll. Aileen would later suspect that Philby was a Soviet spy.

- Litzi’s Mother’s Request on Internment (1939): Milmo’s report indicates that Litzi’s mother (recently extracted from Vienna), in an application to relieve internment restrictions, pointed out that Philby was paying £12 a month towards her (presumably the mother’s) maintenance.

- Litzi’s Permission to Go to France (1939): Milmo reported that Philby had requested permission for Litzi to return to France on September 26, as if she had been stranded in the UK when war broke out.

- Vetting Form for MI6 (1939): An MI6 Vetting form for Philby was recorded in his father’s Personal File, dated September 27, 1939. This probably resulted from a meeting Philby had with Frank Birch, who had just re-joined GC&CS. Any job application might consequently have drawn attention to his dubious career, and his statements to Flora Solomon. It alternatively may have been related to the initiative from Michael Stewart to have Philby recruited. Further notes indicate correspondence concerning ‘G. Egge’ and Litzi Philby.

- Litzi’s Permission to Return to UK (1940): The Personal File on Philby’s father indicates that a Form of Interrogation, after intervention by the PS (Private Secretary) to the Secretary of State on December 8, 1939, was sent to Newhaven for the purpose of cross-examining Litzi on her arrival from France in early January. Philby admitted that he had applied to the authorities to facilitate her return (but omitted to mention the earlier request to allow Litzi to passage to France).

- Evidence from Krivitsky (1940): During his interrogation in London, the GRU defector Walter Krivitsky told Jane Archer that the NKVD had deployed to Spain ‘a young Englishman, a journalist of good family, an idealist and fanatical anti-Nazi’. This lead was not followed up.

- Residing with Aileen Furse and Burgess at Flora Solomon’s (1940): Philby unwisely advertised his association with Burgess by inviting him to join him and Aileen at Flora Solomon’s residence.

- Interview for position in Section D (1940): According to Cave-Brown, in June, Vivian interviewed Philby for a position in the sabotage unit Section D, before it was taken away from MI6 and incorporated into SOE (in August).

- Deceit on SOE paperwork (1940): Philby lied about his marriage when entering SOE (Cave-Brown).

- MI6 recruitment & Vetting (1941): After a recommendation from Tomás Harris, Philby was approved for a position in MI6’s Section V. Valentine Vivian believed his name may have come from a pool of potential recruits: his process of vetting was to have lunch with Philby’s father.

- Deceit on MI6 Paperwork (1941): Philby lied about his marital status when completing MI6 entry paperwork.

- Litzi’s Wartime Associations (1940-1945): Litzi mixed regularly with Tudor-Hart’s circle of Austrian Communist refugees.

- Litzi at Bentinck Street & the Courtauld (1941-44): Litzi met Blunt and Burgess at Victor Rothschild’s House at 5 Bentinck Street, and also visited Blunt at the Courtauld Institute.

- Litzi’s Job Application (1943): Litzi applied for a government job, and used her husband’s name as a reference. Taken aback, Philby declared that his ‘first wife’ was ‘OK’.

- Leakage of Intelligence (1944 & 1945): Maurice Oldfield, then working for SIME in Cairo, believed that Philby might have been involved in leaking information about the defection of the Vermehrens, and the arrest of the head of the LUCY network, Sando Rado. (source: Richard Deacon)

- Stalin’s Challenge (1945): Stalin hinted strongly that he had received intelligence about US/GB-Germany negotiations for peace that took place in Bern, Switzerland.

- Gouzenko’s Revelations (1945): In Ottawa, the GRU defecting cipher-clerk Igor Gouzenko described a Soviet agent in British counter-espionage.

- Volkov Incident (1945): The would-be defector Konstantin Volkov contacted the British in Istanbul, offering to hand over a list of agents in Counter-Intelligence and in the Foreign Office, including the head of a Counter-Intelligence Department. Philby engineered his own role in travelling to Istanbul to investigate. Volkov was extracted by the Soviets, and killed.

- Evasion on MI5 Questions concerning Litzi Honigmann (1946): When MI5 officers sought information from MI6 about the Honigmanns in East Berlin, Philby concealed the fact that Mrs Honigmann had been his wife.

- Guy Liddell’s Suspicions (1947): Liddell told MI6 officer Eric Roberts that he believed that MI6 may have been penetrated by the Soviets.

- East European Failures (1946-1949): Several MI6/CIA exploits in Eastern Europe failed, most spectacularly the project to insert insurrectionists in Albania. Philby played a part in these disasters.

- Change to Soviet Cyphers (1949): Three months after Philby was indoctrinated into VENONA, Moscow changed its encryption methods, thus closing off further traffic to analysis by US/GB. (William Weisband was later judged to have been responsible for the leak.)

- Burgess Cohabitation in Washington (1950): When Guy Burgess was posted to Washington in 1950, Philby agreed to take him under his wing, and they shared accommodation.

- Attempted Distancing from Maclean (1950): In Washington, Philby dissembled over his acquaintance and familiarity with Donald Maclean.

- Martin/Archer Report (1950): A report commissioned by Menzies and Vivian from MI5 (Archer and Martin) drew attention to Philby’s sudden conversion to fascism in the mid-1930s.

- Tudor-Hart Photograph of Philby (1951): Tudor-Hart was worried about negatives of photographs of Philby that she had kept.

- Kollek in Washington (1951): Teddy Kollek, who knew of Philby’s role and associations from Vienna, and had attended his wedding, warned James Angleton that Philby could be a Soviet spy.

- ‘Third Man’ Business (1951): After the abscondment of Burgess and Maclean, Philby immediately came under suspicion as the ‘Third Man’ who had warned Maclean of his imminent call to be interrogated.

Commentary:

- While the reliability of all these events may not be total, most of them have indeed been verified and accepted. Some possess only thin evidence. For example, Anthony Cave-Brown, in Treason in the Blood, does not offer any source for the events listed at 21 and 22. Yet such assertions are inherently no less respectable than Chapman Pincher’s attributions to ‘confidential inside sources’, Christopher Andrew’s unidentified references to the ‘Security Service Archive’, or even the dubious statements of many memoirists (including those of the subject himself) that have made their way into the Philby lore.

- The volume of these incidents is both impressive and shocking. While the outrageous behaviour of Guy Burgess should have disqualified him from ever being recruited by the Diplomatic or Intelligence Services, and Donald Maclean’s outburst in Cairo should have been treated much more suspiciously, the extended pattern of hints and clues displayed by Philby, with an accompanying disregard by the authorities, is exceptional. (These are what Guy Liddell described as ‘the cumulative effect of points against him’, a conclusion reached too late in the game.)

- While many of these events have been reported in several books, I do not believe that they have been consolidated into one single dossier anywhere, and thus the possible relationships have not been explored. For instance, was the lethargy in following up Krivitsky’s hints concerning a journalist in Spain related to any change in status of Philby in the considerations of MI5 and MI6?

- The declarations by such as Milmo point to the fact that a Personal File on Philby had been created. Indeed, it would have been extraordinary if one had not been started when he went to Vienna in 1933. A burning question is therefore: what happened to Philby’s PF? Was it buried, or closed at some stage? The fact that items concerning Philby were noted in his father’s file towards the end of 1939 suggests strongly that his own PF had been retired by this time.

- The same criteria apply to Litzi Philby’s PF. The comments about her from Milmo’s report strongly suggest that comprehensive notes were being taken about her from the time she arrived in the United Kingdom, yet the PFs of (for example) Edith Tudor-Hart are devoid of any reference to Litzi until the bizarre introduction of Litzi Feabre, and a PF pertaining to her, in 1945. The absence of such notations might provide clues to Litzi’s role during this period.

- In the absence of the PFs themselves, or supporting memoranda, it is difficult to determine at what stage certain remarks were made. For instance, were Milmo’s descriptions of Litzi’s travels in the mid-thirties collected from observations at the time, and stored, or was a trawl through port and customs records undertaken in the light of later suspicions? A possible explanation is that the annotations were recorded at the time of the events, and were not considered startling or damaging when they occurred, but were ‘discovered’ later by a third party.

- One not completely obvious lesson from the events is the fact that sections of the Intelligence Services sometimes kept other groups in the dark, such as when an alias for Litzi Philby was created. This was not an unusual phenomenon, and could be compared with the activities of the rogue TWIST committee in World War II, or the efforts made by senior MI5 and MI6 officers to conceal from their subordinates the project to manipulate Ursula Beurton (née Kuczynski).

- In any case, a critical change of circumstances appears to take place after the outbreak of the war, in September 1939. This coincides with several important other events, such as the death of Sinclair and the contest for his successor as MI6 chief, the Venlo incident, after which the European MI6 organization was essentially destroyed, and Claude Dansey’s attempt to merge his back-up Z Organization into MI6, during which activity he returned from Switzerland in November of that year.

What this leads me to believe is that at some stage Philby made an approach to MI6, indicating that any Communist sympathies he may have shown in the past had now waned, and that his wife was no longer an agent dedicated to the cause of the NKVD. MI6 was taken in by this ruse, took Philby to its bosom, and planned to treat Litzy as a valuable source of information on émigré Austrian communist circles. I now present my chain of reasoning as I explored the archival material.

Philby’s Personal File?

One intriguing avenue of research is seeking evidence that Kim Philby had a Personal File (PF) created for him early in his career, and, if so, what happened to it. Information on him is scattered: he turns up frequently in communications between MI5 and MI6 at various times, but data on his activities as someone possibly under surveillance are elusive. I identify seven potential major sources for information on him: 1) The PF on his father Harry St. John Philby (KV 2/1118-1 & -2); 2) The ‘PEACH’ files, that collect information regarding the investigation begun in 1951 into Philby’s possible guilt as the Third Man, ‘PEACH’ being the codename assigned to him (FCO 158/27 & 28); 3) The Personal File on Philby apparently opened at the time of the PEACH investigation (or shortly before, early in 1951), which assembled various facts about Philby from other files (PF 604584); 4) The Maclean/Burgess files created in the 1955 investigation into Philby (FCO 158/175); 5) The file opened for Litzi (of course not released, and thus useful only by external references to it), which is bizarrely identified in the main as being the record of Litzi Feabre, with occasional admission that this person is Litzi Philby (PF 62681); 6) The files on Litzi’s partner and later husband, Georg Honigmann, which, by inclusion or oversight, provide some clues to the relationship (KV 6/113 & /114); and 7) Flora Solomon’s files, which contain some very provocative information, including the annotation that PF 604584 included a Volume 8, a pointer that shows there is much still to be released (KV 2/4633, 4634 & 4635).

There is a good case to be made that Philby would a priori have had a file opened on him when he travelled to Vienna in 1933 to help the socialists. A precedent is the case of a similar subversive, John Lehmann (KV 2/2253-2255), who also went to Vienna at this time, and was likewise encouraged in his activities by Maurice Dobb, a Cambridge don who was noted as an inspirational mentor with communist convictions. Lehman was tracked very closely, and it is difficult to imagine that Philby would not have come under the same close surveillance. Thus one might conclude that at some stage his file was removed or destroyed as an embarrassment. So what facts can be assembled from elsewhere?

The file on Kim Philby’s father is very revealing, since it contains some early references to Kim’s socialist activity, as well as some fascinating exchanges between Guy Liddell and Valentine Vivian on Philby’s recruitment by MI6 through Section D (which I shall explore later). Thus one has to ask the question: do these items appear here because a) his father’s PF was a convenient postbox for storing Kim’s activities; b) they were put here in error, or out of confusion; or c) they were rightly placed (maybe copied) there because of a genuine link between Kim’s activities and his father’s situation?

The earliest note appears in the Minute Sheet dated September 7, 1933 (as with many such files, not all items listed in the Minute Sheet are preserved in the body of the file), and states ‘Extract-re H.A.R. PHILBY – taken from list in office of ‘Labour Monthly’. A handwritten annotation further informs us that this item was ‘Transferred to PF604584 11/6/51’. Three more entries obviously pertaining to Kim then follow (the last dated 15.11.34), before the substance returns to Harry Philby matters. The next entry related to Kim is dated 27.9.39, and concerns an SIS Vetting Form (although that description has been taped over the original type), and is followed by two more entries (the first relating to Kim, the second to Litzi and a certain G Egge, which are listed with the rubric that they should both be moved to PF68261, i.e. Litzi’s own PF.

Thus the references to Kim in his father’s file constitute a motley assortment, the placement of which reflects no obviously consistent policy. The long void between September 1933 and November 1934, as well as the abrupt termination of any entries thereafter, could mean that these were accidental, and that a more comprehensive account had been maintained elsewhere. Or it might mean that Kim Philby was no longer considered a person worthy of interest, as if it had been determined that he was ‘friend’, not ‘foe’. To consider that aspect, I return to Helen Fry and her suggestions about Philby’s loyalties in Vienna.

Early Recruitment by MI6?

As introduced above, my working hypothesis, as a means of explaining the indulgence shown by MI5 to Litzi Philby throughout her life in the United Kingdom, is that Kim at some stage managed to take advantage of an opening to mislead the authorities about his wife’s true role. The extreme version of this theory would be that Kim was an MI6 asset from the beginning. As I reported last month, Helen Fry makes the suggestion that Philby’s activities in Vienna may have been undertaken with MI6’s approval. In the revised edition of her book, Spymaster (2021), she makes a controversial statement, one expressed, however, in a decidedly equivocal manner:

It is, however, possible – though not yet definitely proven – that Philby went to Vienna in 1933 to penetrate the communist network for SIS, and was, in fact, working for Kendrick.

There is a large gulf between ‘possible’, and ‘not yet definitely proven’, and it is not clear what kind of proof Ms. Fry expects might appear at this late stage of the game.

Moreover, Fry’s case is tenuous. She attributes Kendrick’s success in ‘identifying and tracking Russian agents operating in and out of Vienna and the region’ to the wiles of Philby and Hugh Gaitskell (the future Labour Party politician who was attending the University of Vienna on a Rockefeller scholarship), implying, without any evidence, that they had both been working ‘loosely’ for the British Secret Intelligence Service at this time, and had been ‘sent out to Vienna to gather intelligence’. Fry concludes her analysis by asserting that these actions enabled SIS to ‘assess the ongoing threat to western democracy’, and she even identifies Engelbert Broda as one of the victims of this campaign, subsequently tracked by MI5 in Britain.

Yet the irony in Fry’s argument is that MI5 and MI6 failed dismally in their endeavours. They did not assess the threat clearly. They did not prevent Broda being recruited to the Tube Alloys project and revealing secrets of atomic weaponry through Litzi Philby. They even bungled the warnings from Walter Krivitsky. Fry also suggests that the contribution that Philby made explains why he (and Gaitskell) were so easily taken up by British intelligence in 1939-40. She does not explore why, if Kim had been recruited as some kind of asset by MI6, he would not have joined the service officially much earlier. She bizarrely mentions only briefly in passing the complications that marrying Litzi, ‘a high-level threat to Britain as a Soviet agent’, brought to the equation.

I believe it highly unlikely that Kendrick used Philby in any capacity that suggests that he was ‘working’ for MI6. His previous movements, and guidance from Maurice Dobb, give no indication that MI6 had any role in his endeavour. If Kendrick had had any role in his mentoring in Vienna, he would not have allowed a greenhorn like Philby to contact the Soviet Embassy, and would have been appalled at Kim’s marrying Litzi Friedmann. Kim’s actions in Vienna went far beyond what a more careful observer such as Gaitskell, who was scathing about the adventures of the extreme left-wingers, undertook. The circumstances of Kim’s return to the United Kingdom, and his steps thereafter, do not indicate that MI6 saw him as one of theirs. When Fry considers how Philby succeeded in being recruited by MI6 in 1940 she appears to minimize the bad marks against Kim and Litzy earned during the 1930s, regarding them as somehow less significant than a possible short-lived relationship between Philby and MI6 in 1934. (In fact, Philby was not recruited by MI6 proper until 1941.)

And then Keith Ellison pointed out a sentence from Fry’s book, writing to me: “On Philby, Fry writes of one unidentified source who claimed that Philby ‘was working for SIS and always did work for us – though it will destroy the book if you say so openly’ (p 81)”. This was an astonishing revelation. I did not recall the statement. I thus looked up page 81 of Spymaster, but could not find the sentence. We swiftly determined that Keith was using the earlier edition published by Marranos Press in 2014: Fry had removed this startling claim from the Yale University Press edition of 2021. I also own that earlier edition, so I was able to retrieve the relevant section. I immediately sent a message to Helen Fry via her website, asking her to explain why she had dropped this startling assertion, and received the following reply: “In the revised expanded edition of Spymaster, a decision was taken by myself to take out that sentence. I felt it was not my place to keep it in without further evidence to justify it.”

Apart from the evasiveness of this reply (and why not the more active: ‘I decided to take out that sentence’?), I found it perturbing, both from a procedural and substantive perspective. I have earlier noted the perplexing way that the 2021 edition of Spymaster was brought out, with no reference to the preceding publication (see https://coldspur.com/2021-year-end-roundup/ ). For the author to have apparently landed a scoop, and published it, ‘openly’ I suppose, although without contributing anything to the identification of the source or analyzing what he or she meant, and then retracting it, certainly not ‘openly’, seemed to me to be a great dereliction of authorial duty. Indeed, was the first version of her book ‘destroyed’ on that account? One can only wonder what the motivations of her leaker were, to grant her such a loaded rumour, and then threaten her not to deploy it.

It sounded to me that Ms. Fry had been ‘nobbled’, i.e. coerced through some sort of threat, to remove that allegation, however tenuous it was. After all, she makes so many vague and uncertifiable claims about various persons in this business that citing ‘the lack of evidence to justify it’ as the reason for deleting this particular assertion seems particularly feeble. Any scrupulous researcher would have followed up to determine exactly what her informant meant: How long back did “always” go? Had that assertion been made anywhere else? Why was the informant telling Fry if he or she did not want her to publish? Furthermore, why did the authorities (as I believe they were surely involved) move so clumsily over the deletion of the claim? The book was published: the facts could not be erased. Did they really believe that no one would notice the excision that had been made, and simply accept Fry’s ‘expanded’ (but actually ‘diminished’) account?

Yet the outcome is that the reading public could encounter a hint that Philby had at some stage come to an accommodation with MI6. When did that happen? (How long back did ‘always’ go?) The sources are, of course, woefully thin, so first I move forward to a critical moment in Kim Philby’s career.

The Internment of Harry Philby

I turn now to the events of summer 1940, when Philby at last managed to get his foot in the door of MI6. At that time, Guy Liddell in MI5 and Valentine Vivian in MI6 were in intense discussions about the proposed internment of Kim’s father, Harry St John Philby, who was scheduled to arrive in Liverpool in October 1940. (This exchange is covered by Edward Harrison in Young Philby, though I believe he overlooks some of the subtleties of it.) Harry Philby had been detained in India under emergency regulations while travelling from Saudi Arabia to the USA, as his pacifist and pro-Nazi statements expressed in intercepted letters led the Foreign Office to judge that he had been engaged in treasonable activity. In a letter to Liddell of September 12, H. L. Farquahar in the Foreign Office expresses the confident hope that his office ‘can safely leave it to you and the Home Office to deal with him suitably when he arrives’. Farquahar engages in the classic buck-passing procedure of advising his interlocutor to ‘do what’s right’.

What did Liddell know about the case? Intriguingly, at the beginning of the Harry Philby PF (KV 2/1118-1), a handwritten note in red ink – apparently initialled by MI5 chief Vernon Kell – states: ‘Capt. Liddell knows Philby well and can supply any information’. It is dated June 18, 1932. This item caught my attention: so early, soon after Guy Liddell had joined MI5 from Special Branch. Was he really known as ‘Captain Liddell’ at that time, bringing over some rank from WWI? And how was it that he knew Philby well? It must surely refer to Harry Philby, as Kim would still have been at Cambridge at that time. Was it perhaps Guy’s father, also a retired Captain, to whom Kell was referring, perhaps as a consultant familiar to MI5 officers? No, it could not be, since Liddell père had died in 1929. Nor was it Guy’s older brother, Cecil, who was not brought into MI5 until 1939. It must be Guy, and his knowledge of Harry.

Yet in his letter to Vivian of September 19, where he seeks guidance from Vivian, Liddell signs off as follows: “I recollect that you know PHILBY fairly intimately”, as if he himself were not so well acquainted. I puzzled over this conflict until Keith Ellison suggested that Liddell had long been familiar, not with Harry Philby personally, but with his case-history, since he had been tracking him in some way since his days in Special Branch in the 1920s. Even if that were the case, however, it suggests that Liddell was perhaps not quite the expert that Kell had set him up to be, had possibly let his attention lapse during the 1930s, and was perhaps introducing notions of intimate friendship into the process of professional business a bit too eagerly.

Vivian replies, expansively, on September 24, indicating that Liddell’s letter was ‘one of the hardest letters to answer, which you have ever sent me’. He did indeed know Harry Philby well, ‘a bullet-headed young Assistant Commissioner in the Punjab’, and explained how he had gained the enmity of the Foreign Office and the Colonial Office, Vivian’s final judgment being that Philby was not disloyal, but merely ‘insufferably arrogant’. He then, however, introduces the following aside:

Now, the curious thing is that his son (the person to whom I believe he refers to as “Kim” in one of the letters returned herewith is one of our D. officers. In that capacity I have met him once or twice and found him both able and charming. He himself told me that his father had cooled down in the strength of his views in the last few years, but that would not appear to be so from the letters. Young Philby was, of course, in D’s section being taken over by Dalton, but, as that has happened fortuitously, the son will be more or less under the direction of a man known to his father, with whom I believe the latter has had quite a number of semi-covert dealings. I mention young Philby simply because I think it will make it more difficult to take any repressive measures against his father.

Apart from the ironic way Vivian has been taken in by charm (Harry Philby would later convince Vivian, who was ‘vetting’ Kim for entry into Section V, that Kim had discarded his youthful socialist beliefs), this passage suggests a mismeasure of Vivian’s responses. First of all, it strongly suggests that he had not interviewed Kim personally for the job in Laurence Grand’s Section D. Secondly, he is mistaken about Kim Philby’s position – unless by ‘our’ he means His Majesty’s intelligence forces – since, as he indicates, D Section had by then been split off from MI6 and absorbed into the new Special Operations Executive (July 1940). It was then led, at ministerial level, by Hugh Dalton, a fait accompli that Vivian explicitly recognizes. (It is true that there was a delay in the announcement of the re-organization, but that had all been squared away at Menzies’ level well before the time of this correspondence, as Alexander Cadogan’s Diaries confirm.) But why should Vivian be so sensitive about the reactions of a recent recruit outside his bailiwick, someone who could clearly be sacrificed if necessary, in the light of his father’s detention? Did he perhaps fear the hostility of the much disliked Dr. Dalton, or was he afraid of what the reaction of Philby fils might be? In any case, Vivian cowardly passes the buck as well. He thinks that it is urgently necessary not to give Harry Philby any further grounds for grievance, but acknowledges to Liddell that the Foreign Office and the Government would ‘gladly see you using strong-arm tactics’: “With this uncomfortable problem I must leave you to deal.”

Liddell’s response was to pass on meekly Vivian’s comments almost verbatim, without indicating his source. The matter was elevated to Wilson-Young of the Foreign Office, who replied curtly on October 12, stating that a Detention Order against Philby had been issued by the Home Secretary, and that the S.S. City of Venice was expected to dock in a few days. In a postscript, he indicates that the Home Office ‘cannot agree with the estimate of Mr. Philby given by your informant’. Liddell’s weakness is shown in his letter to Vivian of October 21, where he, having recently passed on an anonymous report (by Vivian) to the Foreign Office, now complains that an unknown person in that latter department is using the same tactics when questioning Philby’s loyalty to anyone but himself. His letter concludes:

. . . I cannot help feeling that it may be a very unintelligent remark and that a gross blunder is being committed. Do you think there is anything to be done, particularly owing to the fact that the son is in your employ?

I think this was a feeble but provocative performance by Liddell. Harry Philby was arrested by the Liverpool City Police when he arrived on October 18. All of Liddell’s ruminations were for nothing, and his standing must have been reduced with the Home Office. But why ‘particularly’? Why should that mean so much, especially when Kim Philby was not in Vivian’s employ? And why should Liddell’s professional judgment of Harry Philby’s culpability be so easily undermined by a desire to protect the son? After all, Kim himself had been a member of the Anglo-German Friendship Society, and his affiliation was open. The arrest of Harry, and the thought that ‘the apple does not fall far from the tree’ should perhaps have given Vivian and Liddell some second thoughts about Kim’s recruitment rather than simply expressing concern about Harry’s internment. (The trace requested from MI5 on Kim came up with nothing, according to Edward Harrison.) Maybe it is possible to overread the significance of this very bizarre exchange between Vivian and Liddell, but it suggests to me an unhealthily close relationship between the two weak officers and a junior recruit whose career future should have been a minor consideration for them. In their choice of language, both gentlemen hint that Kim Philby is more closely linked to MI6 than the facts warrant.

Another interpretation comes to mind. Rather than absent-mindedly overlooking the organizational changes with SOE, perhaps Vivian and Liddell were implicitly reinforcing the fact that Philby was indeed considered an asset of MI6 at that time, though not officially on the books. That might point to an arrangement whereby Kim, possibly after being challenged on his past history, had been able to turn the tables, to suggest that he could contribute to counter-espionage in some way. Harry Philby was eventually released on March 18, 1941: it was accepted that his detention had been illegal. When Vivian was asked to endorse Kim’s appointment to Section V a couple of months later, he queried his newly rehabilitated friend Harry about Kim’s communist spell at Cambridge, a somewhat anomalous question in light of the fact that Kim’s latest interest had been Anglo-German Friendship. The inability of Vivian (and Liddell) to detect any artifice in these postures is a sign of their essential unfitness for the jobs they held.

What is also noteworthy is that Liddell makes no mention of the Harry Philby controversy, or his exchanges with Vivian about it, in his Diaries. Moreover, in a diary entry for November 1, 1940, he comes across strongly against any relaxation of detention for prominent B.U.F. (British United Front) members, which would appear to be hypocritical. But where to go next on this trail? I returned first to the Edith Tudor-Hart files.

Edith Tudor-Hart’s Files

While the archival material on Edith Tudor-Hart is very rich, that on Litzi is very sparse. ‘Was that in itself a clue?’, I wondered. If Litzi had been such a close associate of Edith in the Austrian Communist Party cell in London, I would have expected her name to come up more frequently – apart, of course, from the time that she was in France, which ran from early 1937 to January 1940. So I re-inspected the files on Edith, registering the key dates and methods of intelligence collection.

The first batch (KV 2/1012) covers the period January 1930 to October 1938. It consists almost exclusively of reports via MI6 from Vienna, of Special Branch surveillance reports, and many intercepted and photographed letters. It also contains a damaged version of the interrogation of Tudor-Hart after her camera had been used in the Percy Glading espionage activity. Special Branch was also able to determine, from an agent’s report, that Edith was hosting meetings of a local branch of the Communist Party in 1935. Yet one item that stood out for me was the report that Edith arrived with her mother Adela (actually Adele) at Dover on August 27, 1937, Adele being given permission to stay in the country for three months.

What was going on here? Why was the Home Office allowing the parents of known Communist subversives to join their daughters for residence in the United Kingdom? This was an exact echo of the passage of Litzi Philby’s parents from Vienna to England at about the same time. And Adele outstayed her welcome. Ancestry.com shows that she went to live in Bournemouth, and, according to the 1939 census, was still living there, supported by ‘private means’. As an alien, she was also fortunate enough to satisfy the tribunal in November 1939 with ‘no restrictions’ applied. Indeed, a profile in Tudor-Hart’s fresh file at KV 2/4091, dated December 1, 1951, records (alongside similar information about Edith’s brother and two cousins) that her mother resided in Cricklewood at that time. Records show that Adele outlived her daughter, dying on May 24, 1980 in The Bishop’s Avenue, London N2.

This apparent charitable behaviour of the British authorities was a puzzling phenomenon, to be stored away. I moved on to the next batch, namely KV 2/1013. This series covers the period from November 1938 to March 1946, although the Minute Sheet tantalizingly contains some additional few entries that take it up to May of that year, but which are not present in the body of the file. Yet the period 1938 to April 1940 is very sparsely covered – merely two entries concerning attempts to rescue CP members from Europe, before the reports start up in earnest in April 1940. The first flurry appears to have been provoked by interest in the activities of Alexander Tudor-Hart, now divorced and with a new partner, Constance, who has come to the attention of the Shrewsbury Police. (The divorce between Alexander and Edith was not made absolute until October 11, 1944: like Aileen Philby, Constance changed her surname by deed poll in order to project respectability.) The file picks up in earnest in March 1941, when the Special Branch’s surveillance efforts are considerably boosted by the work of the agent KASPAR, revealed by Brinson and Dove in A Matter of Intelligence to be Joseph Otto von Laemmel, and also by Kurt Hiller, both members of the Freie Deutsche Kulturbund. (Hiller provided much information on the Kuczynskis.)

A sudden shift in tempo is shown on March 14, 1941, where a very comprehensive report on the Central Committee of the Austrian Communist Party in the UK, compiled by B24G, appears. It lists such luminaries as Eva Kolmer (Secretary), Franz West (Political Leader), Edith Tudor-Hart (Accountant, presumably Treasurer) and Ing. [Engelbert] Broda (Training Leader), as well as fourteen other names. There follow extracts from intercepted correspondence between Tudor-Hart and Martin Hornik in internment in Canada. During 1942, Special Branch kept a close watch on Tudor-Hart’s movements, even inspected her bank account, and reported through B6 to Milicent Bagot in F2B. The file then meanders listlessly through 1943 and 1944 until it covers the clumsy propaganda business with the Sun Engraving Co. Ltd., in 1945.

Towards the end of 1945, an undated memorandum appears that runs as follows:

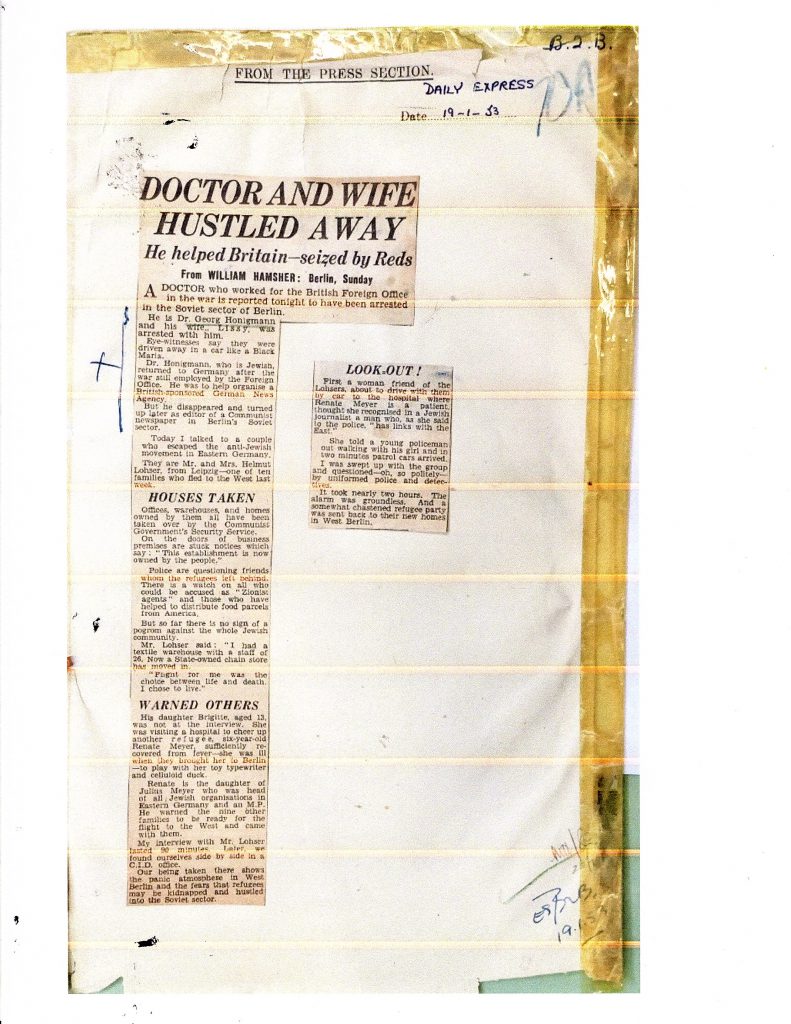

Edith Tudor-Hart is said to be in touch with a certain Anna WOLF who is apparently attached to the American diplomatic representative in Vienna, and is a close friend of Lizzy FEAVRE [identified as belonging to PF.Y.68261]

This appears to be the first recorded reference to Litzi Philby’s alias: a letter of September 9, 1945, from E5L to F2B, displays a list of members of Tudor-Hart’s circle, including Loew-Beer, Mahler-Fistolauri, Dennis Pritt, Bunzl, ‘Hafis’, and the infamous ‘Lizzy Feavre or Feabre née Kalmann’ (as described in last month’s coldspur).The last is accompanied by the fictitious legend that she left Vienna for the UK in 1934, and later went to France where she married an Englishman ‘thus acquiring British nationality’. It would appear that E5L has no idea about Feabre’s true identity.

The Austrian group is now nervous and on the alert, after the breaking up of the Soviet spy-ring in Canada (September 1945) has been revealed. MI5’s interest in the Tudor-Hart circle intensifies, and suspicions are cast upon Broda, because of his working for Tube Alloys. Yet it seems that MI5 has an insider still at work. On March 12, 1946, E5L sends a report to Marriott (F2C), describing Tudor-Hart’s newest associates, one of whom, Dr. JANOSSY, employed by ICI ‘has stumbled upon a new invention which may prove to be more effective than the atomic bomb.’

One might whimsically imagine that an appropriate response at this juncture would have been to ‘collar the lot’. Of course, it was not that simple. Yet this file has one more extraordinary surprise to offer: in the very last entry, a memorandum from B2B to Marriott of F2C, dated March 18, 1946, records the arrival of a mystery visitor to Edith Tudor-Hart’s residence, a suspected snooper with an Oxford accent. Tudor-Hart believed that the call was related to Broda, and, indeed, the latter visited her a few days later to report that his landlord had discovered an intruder trying to break into Broda’s room. (This search was no doubt occasioned by Broda’s meetings with Nunn May when the latter returned from Canada, and was arrested and convicted for espionage.) Apart from shedding light on the occasionally clumsy enterprises of Special Branch, an intriguing question must be posed. How did B2B know about this event?

The astonishing fact is that the memorandum openly states that Tudor-Hart opened the door in the presence of LAMB, that name presumably being a cryptonym. Who was LAMB? The reason that this disclosure astounded me is that I had only the same day re-inspected the Honigmann archive that I had received since last month’s posting. A document there reproduces an excerpt from the critical interview between Arthur Martin and an unidentified interviewee from the Tudor-Hart file, where the name was redacted, and I hazarded some guesses about his identity. Only here, the name is not redacted: the name of the interviewee appears as ‘LAMB’. The link was clear. No wonder the interviewee knew Edith Tudor-Hart intimately from 1944 onwards. I shall return to this breakthrough later.

The last volume, KV 2/1014, picks up the story from May 1946, and carries on until October 1951. The watchers continue to monitor Tudor-Hart’s circle, maybe still assisted from inside. A report dated June 14, 1946, starts off by stating that ‘Lizzy FEAVRE has been more active during the last few weeks’, no doubt preparing to join her partner, Georg Honigmann, who had received clearance to travel to Germany on May 10. By June 11, she is reported as having joined Honigmann in Berlin, while Tudor-Hart maintains discrete communications with Broda. She is still trying to foment the revolution in Britain, and Arthur Wynn and Professor Joliot-Curie appear in her list of contacts.

By February 1947, however, Edith has been interrogated, and has ‘at last’ admitted that she used to work for the Russian Intelligence in Austria and Italy in 1932-1933, and had collaborated with a Russian who was also her boy-friend. That was assuredly Arpad Haasze, since she received a letter from him in August 1947. Matters then drift: a report of December 13, 1948 indicates that ‘Edith Tudor-Hart is hardly engaged in any CP activities at present’. Edith took on the alias ‘Betty Grey’, and the authorities were confused for a while, but concluded by August 1951 that the two were in fact one person by analyzing their handwriting. In October 1951, Simkins of B2A requested a fresh Home Office Warrant on Edith’s mail, because of ‘a connection with a current case of suspected espionage’. And that leads up to the Martin interview of October 3 that concludes the file. From this we learn that LAMB had still been enjoying Edith’s confidences, as he had reported in 1948 on Litzy’s movements, and described the essence of correspondence passed between Litzy and Edith since the former moved to Berlin.

Informers

An overriding question concerning the Tudor-Hart disclosures is – how did MI5 glean its information, apart from the mechanisms of surveillance, telephone taps, and intercepted mail? The role of KASPAR is now very evident, as he was a member of the Kulturbund, and was presumably trusted enough by Edith for him to become a close acquaintance, to the extent that he was accepted as a guest in her lodgings. Yet can the very detailed report on the membership of the Central Committee of the Austrian Communist Party be attributed to KASPAR? It is not sourced as coming from him in the Tudor-Hart files *, unlike other reports. And Brinson and Dove, even though they credit KASPAR with this important report – without any explanation, and probably faute de mieux – point out how irresponsible it was for Edith to have confided in KASPAR. They write, after expressing surprise that Broda would even have shared confidential information about atomic energy with Tudor-Hart:

There is, however, a third and equally astonishing aspect to this report (from September 1946), namely that Tudor-Hart, a Soviet agent herself, would have talked so freely to ‘Kaspar’, that is Josef Otto von Laemmel. Certainly she would have known Laemmel from the earliest days of the Austrian Centre, when both held a position there, but she would also have known that Laemmel would have been forced out of the Centre, and was extremely disgruntled with the Austrian Communists as a result, and that he was a leading member of the tiny Austrian Christian Socialist group in exile and very far removed from her own political position.

[* As I was putting this piece to bed, I noticed that an identical copy of the report in the Broda files at KV 2/2350 explicitly identifies the source as KASPAR. It looks genuine, as if typed at the same time, but I still have reservations, to be investigated at another time. It might have been delivered to KASPAR by someone else, as Brinson and Dove suggest. I cannot believe that Laemmel could have worked so closely with the inner circle of the Austrian CP of GB inner circle, at this time, or any other.]

As I noted, in that extract from the Martin interview in the Honigmann files, the name ‘LAMB’ is unredacted, which led me to think that it was perhaps the interviewee’s real name. But I could not find any diplomat or officer bearing that surname. And then I stumbled on the report in KV 2/1013 that identified indubitably that Edith’s companion at the door was ‘LAMB’. Who could have got so close to her? It was Nigel West who came to the rescue, since in his book that I panned last month, he explains, in his Notes to the chapter on Broda:

Josef Lemmel’s [sic] codename was changed from KASPAR to LAMB, probably to avoid confusion with a technical source in the CPGB headquarters in King Street, actually a microphone codenamed TABLE and the KASPAR.

KASPAR and LAMB were the same person. [Indeed, Brinson and Dove reveal this on page 158 of A Matter of Intelligence. I had overlooked it. The Broda archive also explicitly confirms the equivalence.]

‘Laemmel’ is obviously a derivative of the German word ‘Lamm’ = ‘lamb’, so the choice of cryptonym was as unimaginative as that of EDITH. Thus the enigma about the identity of the interviewee was solved. It was neither Gedye, nor Ellis, nor Cookridge (né Spiro). MI5 had hauled in one its most effective spies in the Austrian émigré organizations to help flesh out their knowledge of Litzy. Moreover, Laemmel’s career included relevant experience in Vienna, which sealed the deal, and made the testimony recorded by Martin more acceptable. As Laemmel’s Austrian biography detail informs us:

From 1928 to 1933 he held the post of secretary of the Styrian Writers’ Association and was then press officer for the ‘Ostmark Sturmscharen’ until 1938 and emigrated to London via Switzerland because of the threat of persecution. There he joined the ‘Austria-Center’ and worked as head of the library. Because of the increasing communist influence, he left the organization in 1940, was then secretary of the ‘Association of Austrian Journalists in England’ until 1945 and worked on radio programs of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).

His presence in Vienna might thus enabled him to have had exposure to Haasze, but as an Austrian, he would not have been close to the Philby-Gaitskell circle, and therefore would not have known about the Kim-Litzi marriage. It makes sense.

Yet did it explain everything? LAMB explained to Martin that he had become acquainted with Edith closely only in 1944. The report on the composition of the Committee had been compiled in March 1941, and it would have been very unlikely for Laemmel, given his political convictions, to have gained access to the CP’s closest and most secret forums. Brinson and Dove are quick to ascribe reports on the Austrian Communist Group to Laemmel’s own set of informers, but there is no evidence of that. Moreover, in the Honigmann archive lies a note from KASPAR dated September 9, 1945, that reports about Edith Tudor-Hart’s circle of Communist friends and sympathizers, as if this were intelligence freshly gained. It could not possibly have been provided by the same person who had the insider knowledge from 1941.

What struck me in the survey of the members of the CP Committee was the absence of one name that one would expect to be prominent – Litzi Philby. If Litzi had been as dedicated a member of the communist underground as anyone, had been a close friend of Edith Tudor-Hart, and had collaborated and conspired with her during the war, as every historian and biographer has asserted, one might expect that the informer, whoever he or she was, would have listed her name. After all, she was so intimately embedded in the circle that she was chosen to be the courier to meet Broda clandestinely and in 1943 to collect his papers purloined from the Cavendish Laboratory. Yet it is only in 1945 that her name appears, and then under a pseudonym. Was she forced out of the covers by some mischance, and a poorly disguised scheme devised to conceal her true identity? Had Litzy perhaps been the source of the intelligence of the communist cell, and had MI5 perhaps been distracted from her true mission? It would not have been out of character for Moscow Centre to have diverted attention to the earnest but essentially harmless rumblings of the Party itself, while more important work was being performed away from it.

A Theory

This analysis led me to solidify my hypothesis that, at some stage, Kim Philby came out of the cold, and struck some sort of deal with his intelligence opposition. I had at first considered that this might have been performed in 1937, before the parents of Edith and Litzi were so magically spirited out of Austria, but I now think that that phenomenon was simply coincidental, and perhaps the result simply of a legal and humanitarian policy, since both Edith and Litzy were British nationals by then. Before the Anschluss of March 1938, the Home Office was far more relaxed about accepting refugees from Austria. I think it much more probable that the event occurred in September 1939.

The signing of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact gave even the most hardened Communist, committed for years to the fight against Fascism, pause for thought. Goronwy Rees rebelled against it, and Guy Burgess wanted him killed for his apostasy. Arthur Koestler abandoned his belief. Harry Pollitt, leader of the CPGB, lost his job by challenging the Moscow Line. To begin with, Philby was incredulous, and, according to Gorsky’s report of May 1940, it took several conversations to bring him around. Yet it would have given Philby a singular opportunity to play a subtle but dangerous game: “Look, it is true that Litzi and I had communist sympathies, but that is all changed now. I have convinced her that the world has changed. With her connections, Litzi is prepared to provide you with insights into the membership and activities of the Austrian Communist Party in exile. And I can work with you to help defeat the Nazis and their allies, the Soviets.” He later tried to maintain this fiction. When Philby was interviewed by Dick White in June 1951, he told him, in an effort to minimize the danger of the Litzy connection, that he had ‘subsequently converted her’ (Liddell Diaries, June 14).

We know that Philby was in some form of contact with MI6 at this time, because a vetting-form from MI6 was recorded in his father’s file on September 27, 1939, and it would appear to be linked to Philby’s conversations with Frank Birch of GC&CS. The circumstances behind this event are very provocative. Flora Solomon’s file shows that she had the impression that Kim was still fervently Communist even after the announcement of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (thus contradicting what Gorsky claimed). And yet she still encouraged Birch, the partner of her close friend and employee, Aileen Furse, to interview Philby for a job. Philby had expressed a desire to her to enter British intelligence, and Birch only that same month had rejoined GC&CS. Solomon conveniently arranged a lunch where they could meet.

Birch and Philby had a private chat. While Birch deemed that Philby was unsuitable for cryptographic work, he apparently used his connections to instigate interest in him, later that month, from elsewhere in MI6. (GC&CS reported to MI6.) Hence the vetting request of September 27. And when Philby returned from France in May 1940, Birch apparently helped him gain entry elsewhere (into Section D, presumably). While the testimony of Flora Solomon may not be completely reliable, it was an astonishingly reckless action by Philby at exactly the same time to reinforce his Communist sympathies and advertise his objective of entering British Intelligence. Birch obviously knew where the lead came from, and any serious trace would have put the spotlight on Solomon.

I find much that is phony – even furtive – about this account, given by Solomon in 1962 to the incompetent interrogator Arthur Martin. First of all, it would have been very irresponsible of Flora Solomon, knowing that Philby was a committed Soviet agent, to recommend him for intelligence work, especially as she claimed that she had just switched her allegiances because of the Pact. Second, it would be highly irregular for her to know about Birch’s posting, and what Bletchley Park was about. If Aileen Furse (Birch’s lover, and employee of Solomon’s at Marks and Spencer) had leaked it to her, that would likewise have been irresponsible, and Birch, when he found out, should have been aghast that a Communist sympathizer had been informed of his role in cryptographic work, and the location of his workplace. Thus Birch’s willingness to speak to Philby privately (after that lunch also attended by Aileen, and Solomon’s boy-friend, Eric Strauss), and then apparently recommend him for work elsewhere, is a third shocking event, suggesting that he might also have been implicated in the scheme. A fourth consideration is the fact that Kim and Aileen began to cohabit in the summer of 1940 – an event that might well have spurred some dangerous antagonism on Birch’s part – yet Solomon claimed that Birch was responsible for Philby’s gaining his post in intelligence at that time. (That fact appears to be confirmed by a third-unidentified party, as is evidenced in Solomon’s file.) Why Martin did not follow up on these conundrums is unfathomable.

Thus there is much that is bogus about these events. That was not all, however, that was going on at this time. We also know that Philby lied about the travel arrangements for Litzi. He explained to Borovik that his efforts in December 1939 had been made to secure Litzi’s safe return to the United Kingdom from Paris, but he did not admit that his original request of September 26 (as related by Milmo) was to allow Litzi to return to Paris – presumably to collect or store all her belongings, and tidy up her affairs, and maybe to pass on to her controllers what the ruse was about. For it would have been suicidal for Philby to have taken any such initiative without the approval of his bosses. Thus, by the winter of 1939-1940, MI6 and MI5 must have believed that they had a Communist renegade on their books. This turn of events would have fitted in supremely well with the machinations of Claude Dansey, who was at the time arranging for Ursula Kuczynski to gain a British passport in Switzerland, Dansey likewise believing that he was actually controlling Sonia rather than the reverse.

This timing would also explain why MI5 did not respond energetically to Krivitsky’s warnings about a young British journalist who had been sent to Spain. Krivitsky arrived in Liverpool in January 1940, and underwent intense interrogations managed by Jane Archer and Stephen Alley. They should certainly have identified Philby quickly, but could have re-assured themselves: “Oh, yes, we know about him. But he is now on our side, so we don’t have to do anything.” Thus, when Philby returned from France in May 1940, the primary objections to his recruitment by any of the intelligence services had disappeared, and, after a respectable period, he was accepted by MI6 after a very perfunctory interview process.

The fact that Philby was accepted by the establishment by this time is reinforced by anecdotes about Hugh Gaitskell, who had attended the wedding in Vienna. When he joined SOE, Philby sought out Gaitskell, who was at that time principal private secretary to Hugh Dalton, the minister responsible for SOE, for guidance on British long-term plans for Europe. Edward Harrison cites a conference on May 24/25, 1941, where it was agreed that Philby should perform the training of propaganda agents, a decision that Gaitskell agreed with. Either Gaitskell was foolishly colluding with Kim’s objectives, or he had been brought into the confidential agreement concerning the new Philby.

Yet the complications regarding Litzi would not go away. To complete the pretence of ideological separation, Kim and Litzi should have divorced, for both professional and personal reasons. He needed to show the world a complete break from Litzi’s fanaticism, and to be free to marry another. She needed to show that she was still a devotee (which indeed she was) to secure the confidence of Edith’s cell while carrying on a more vital task of couriership supporting espionage. Moscow surely ruled that they should not be divorced, lest Litzi lose her residential qualification, and it did not relax that requirement until her job was finished, the war was over, and she had retreated to East Berlin. Philby would use the excuse for not divorcing Litzi that she might thereby have lost her citizenship, but that was nonsense. She gained permanent citizenship through her marriage, and it could not be taken away, unless, like Fuchs, she were convicted of a serious offence. As Kim became more of an asset, however, the Philby moniker attached to Litzi became a severe annoyance.

Litzy Feabre

What is astonishing is the degree that officers in MI5 appeared to be in the dark – unless a deception game of mammoth proportions were being played. The fact that Kim Philby had married Litzy Friedmann (and was still married to her) was known to members of a select group, who may have had their separate reasons for not promulgating the information. It is sometimes hard to project, from the world of universal data in 2023, the more closed environment of 1943. Yet certain anomalies remain: for example, how could Valentine Vivian claim to Seale and McConville that (in 1946) he had been ignorant of Kim’s first marriage, that he was affected by Philby’s admission about ‘a youthful escapade’, and that he needed a search to discover that Litzi was a Soviet agent, unless he were confident that he could carry off such a monumental show of disingenuousness? And the authors appeared to be taken in by it.

It appears to me that Vivian was trying to string a line to the journalists about his obvious innocence in the business. What he told Seale and McConville was that Dick White informed him, in that summer of 1946, based on information from ‘Klop’ Ustinov, that Litzi was a Soviet agent. But why was Klop used, and what did he know about it? Dick White had an informer, Laemmel (KASPAR), who was providing information during the war about the Austrian Communist circle, and had revealed to Arthur Martin in October 1951 that Litzi had been a Soviet agent, even likening her to Arpad Haasze. Did Laemmel not tell his handlers at the time, or did the information inexplicably not reach White? It is more probable that White and Vivian were being obtuse.

Thus, when ‘Litzy Feabre’ first appears on the scene, several MI5 officers and men (and women) seem to be deceived by the charade. For a while Litzy remains a shadowy figure with an uncertain past. (The documents referring to her are all plastered with hand-written notes inserted much later that she is really ‘Philby’.) And it is not until she has left the country, in the summer of 1946, that questions start to fly around, as MI5 starts to investigate the strange disappearance of Georg Honigmann. The adventure starts off harmlessly: in April Honigmann had been granted a military permit for a one-way journey to Germany, requested by the Control Commission, even though his past Communist activities were known.

[I should mention, incidentally, that the Aliens Department of the Home Office owns Personal Files on Georg and Barbara Honigmann, identified as HO 382/255, containing information ranging from 1936 to 1960. They reside at the National Archives at Kew but have been retained for one hundred years, and will thus not be viewable until 2061. That decision was made in 2017, apparently in deference to the appearance therein of ‘personal information where the applicant is a third party’. I have no idea why the release of such information might endanger national security or embarrass any surviving relatives, and a couple of months ago I thus submitted a Freedom of Information request. I received a mildly encouraging response, but have not heard anything further since then.]

But then the exchanges take on an eerie character. B. H. Smith, in F2ab of MI5, judges that MI6 needs to be informed of Honigmann’s appointment, and thus sends, on May 10, a memorandum to Kim Philby, informing him of the granting of the permit, and describing Honigmann’s communist past. He concludes his letter:

Although his permit was granted at the request of the Control Commission he is not so far as we are aware working for them, but is believed to be employed in the Hamburg area. The Intelligence Bureau of the Control Commission have been given a brief note of our information.

If Philby reacted to this, his response has not been recorded. But it could not have been comfortable. Perhaps he knew of the plans for Georg and Litzi at this time: Litzi was still in the UK. In any event, matters quickly became murkier, and implicitly more dangerous. On May 28, the dogged KASPAR reports to B2B that a Captain Atkinson, with the R.A.M.C., has been in contact with Lizzy Feavre ‘whose friend, Dr. Georg Honigmann recently left for Berlin where he joined the Communists’. This message is passed on to Smith in F2ab.

How Laemmel knew about this exchange, and what Captain Atkinson was up to, will probably remain a mystery for a long time. Was Atkinson the go-between between Honigmann and Litzi, bearing a message that it was now safe for Litzi to join him? Yet the revelation that Honigmann had flown the coop to join the Communists should have been a great shock for MI5 and the Foreign Office. It seems, however, that this intelligence was not acted upon. The Tudor-Hart archive shows that Litzi had been known to have been very busy at the end of May and the beginning of June, and was confirmed as having joined Honigmann by June 11, yet no effort was made, despite Honigmann’s defection, at interviewing Litzi, and preventing her departure. It suggests either incompetence or collusion. Moreover, this factoid surely shows that Laemmel surely did not know Litzi’s true identity, an ignorance he was to claim when interrogated by Martin a few years later. Moreover, if he had been introduced to Litzi through Edith, Edith must have been indoctrinated into the charade. That would have been an essential part of the plan so that Edith would have no doubts about Litzi’s motivations and objectives.

For some reason, another month passes before B2B confirms KASPAR’s insights to Smith in F2ab. He now has an update from KASPAR, however (June 28): “He [Honigmann] is in communication with his friend Lizzy FEAVRE, and the latter reported scornfully that the whole British Security Service and the Police in Germany have been searching for him on the assumption that he had been kidnapped by the Russians.” (Did she learn that from her husband?) Yet this is a strange construction, stating that Honigmann is in ‘communication’ with Feavre, suggesting that she has not yet joined him. Litzi’s comment could otherwise mean that it was KASPAR with whom she had been in contact. According to the Tudor-Hart file, Litzi had joined her partner in Berlin, apparently travelling via Paris and Vienna. Philby claimed to Borovik that at some stage during this summer he opened up to Vivian, and explained that he needed a divorce. If indeed he did go to France to arrange the settlement, it was probably when Litzi was en route to Berlin. It had no doubt all been arranged beforehand. After all, the divorce was granted on September 17, and he was able to marry Aileen a week later, on September 25 at the Chelsea registry office, witnessed by Flora Solomon and Tomás Harris. Yet this timeline would be shockingly undermined by a memorandum to be found elsewhere, in the Broda archive.

On July 20, MI5’s B2B posted another report from KASPAR-LAMB, which reinforced KASPAR’s confusion about the identity of Lizzy, who has clearly been speaking to KASPAR directly. The main portion of it runs as follows:

It would appear that E. BRODA and his former collaborators have been withdrawn from intelligence work and are more or less inactive at present. This holds good for Edith TUDOR-HART too and even for Lizzy FEAVRE who seemed to play a somewhat more important part during the last few weeks and still displays much more activity than the others, but she admitted that she had to refrain from such work owing to the fact that her friend, Dr. Georg HONIGMANN, had taken up work in the Russian zone (see report of 26.6.46). She intends to go to Paris on the 5.9.46 and from there on a special party mission to Prague. She also intends to visit DR. HONIGMANN in Berlin. She has already got her passport and visas and also the ticket of the Air France, issued in the name of Lizzy Philly which seems to be her real name, though she has always been called FEAVRE and even received mail under this name.

The gradual metamorphosis from Feavre/Feabre through Philly to Philby is taking place, and Litzi’s identity as ‘PHILLY’ appears to have received official recognition from the passport office. Litzi is boldly described as being busier than most, and is even ‘on a special party mission to Prague’. KASPAR/LAMB is still confused: MI5 appears to be unimpressed and unconcerned. A handwritten notice even picks up the charade, indicating that the report should be filed in PF 68261 PHILLY [sic].

Interest in the Honigmanns

This was a quite shocking state of affairs. The Foreign Office and MI6 had to confront the fact that a nominee for the Control Commission, a known Communist, had debunked to East Berlin. He had left behind his partner, overtly an even more rabid Communist, who was still the wife of a senior MI6 officer. The authorities had to arrange for the Philbys to gain a quick divorce, preferably not on British soil. And they had to conceal the identity of Honigmann’s partner from prying eyes, such as the Press, and inquisitive officers in MI5. No doubt they believed that they were engaged in some sort of coup, infiltrating a friendly Soviet agent whom they had ‘turned’ into the den of the enemy. Indeed, it may well have been MI6’s original plan to use Honigmann‘s appointment with the Control Commission as a ruse to insert him and Litzi into East Berlin.

Matters quickly turned farcical, however. Questions were being asked in several quarters. The Headquarters Intelligence Division of B.A.O.R. writes to MI5 on November 11, 1946, asking for verification of the rumours about Honigmann’s defection. Graham Mitchell in B1A responds, essentially confirming what MI5 has been told, and indicates that further enquiries are being made. So whom does Mitchell turn to? None other than Kim Philby himself. A letter of November 22 refers to Honigmann’s employment in Karlshorst, and includes the following appeal:

Have you any confirmation of these reports? If they are true it would be very helpful to have them amplified, with particular reference to the nature of HONIGMANN’s work.

A week later, a response under Philby’s name comes through, indicating that Mitchell’s query has been referred to the field, and, a month later (December 23) Philby provides an account ‘based on information from a source who knows Honigmann personally’. After a brief potted history of Honigmann’s career in the United Kingdom, the story evolves into pure flannel, and merits being quoted verbatim:

On calling at Reuters [in May 1946] source was told that HONIGMANN had left for Berlin a few days previously. Later a mutual acquaintance (not in Reuters) said that HONIGMANN was now in Berlin; as far as source can remember, it was also said that HONIGMANN was no longer working for Reuters, and that his job appeared to be somewhat mysterious.

Source paid no particular attention to this remark at the time, as he had no reason whatsoever to connect HONIGMANN with clandestine activities. He knew that HONIGMANN had Left-wing views, like almost every German or Austrian émigré, and that he was a subscriber to Cockburn’s News Letter, but this was thought to be for professional reasons. Politics were in fact never discussed except on a professional basis.

Reuters will presumably be able to say whether HONIGMANN did in fact go to Berlin on their behalf. Source may also be able to discover more details from discreet enquiries.

Philby must have thought he might get away with this astonishing display of chutzpah. After all, his (MI6) bosses were on his side at the time. The Reuters story was no doubt the official MI6 line, else Philby would have been caught out in a sorry deception. And maybe he did escape unscathed for a while. In 1947, however, MI5 picked up the threads again. On July 7, 1947, B1 presented a memorandum to Vivian concerning ‘Alice (Lizzy) HONIGMANN @ FEAVRE née KOLLMANN or KOHLMANN’, the author still blissfully unaware of the subject’s real identity. What is highly significant here is the formulation ‘@ FEAVRE’, indicating that ‘FEAVRE’ was a cryptonym for an asset, analogous to Laemmel’s ‘KASPAR’, a singular confirmation that Litzy had been working as an informer for MI5.

This memorandum included the following text (in fact a subset of the report from KASPAR on the events supplied above, but excluding the information about Busy Lizzy):

Two months later [i,e. after Honigmann’s departure] it was reported that Alice HONIGMANN, although still a keen member of Edith TUDOR-HART’s circle, had had to restrain her activities as HONIGMANN had taken up work in the Russian zone. Her contacts abroad were said to include Magda GRAN-PIERRE, Budapest 12, Kovas utoza No. 46, who was reputed to be an important agent in the Hungarian Communist Intelligence network.

Alice HONIGMANN left England at the end of August 1946 [sic!] and went from Paris to Prague on 5th September. In November 1946 it was reported that she was in Berlin working with Dr. HONIGMANN to whom she has since been married.

I do not follow the logic (‘although . . . . as’) of this assessment. Yet one might conclude that Litzi had gone to Hungary to meet her former lover Gábor Péter, now head of the Hungarian Secret Police, and wreaking havoc. This itinerary nevertheless implies that Philby did not go out to Paris to negotiate the divorce with Litzi until late August. It was all very much a shotgun affair: one can only marvel at the speed with which a London Registry Office was able to recognize the legality of a divorce executed on foreign soil, just a week earlier. And the change of departure date from June to August turns the focus much more intently on MI6’s inability (or unwillingness) to interview Litzi. They had over two months, after her partner had absconded, in which to carry out an investigation, and interview Litzi. Yet they apparently did nothing. Furthermore, had Honigmann perhaps been subjected to some intense interrogation, so that the NKVD could verify Litzi’s loyalty before authorizing the divorce and her departure from the United Kingdom? One might expect such a procedure.

Two days after the creation of the memorandum above, the persistent Milicent Bagot (now B1c) wrote to Anthony Milne of MI6 (no doubt unaware that the latter had been one of Litzy Philby’s lovers, but who had not yet been unmasked and dismissed). Bagot’s objective was to pass on information about Alice Honigmann. The ignorance about Litzy’s previous name endures: the same formation of her identity is used. The famed MI5 Registry has either been purged, or the cross-referencing system is not working. The file then peters out, before recording the fact that a Peter Burchett, Reuter’s correspondent in Berlin, who had been a member of the CPGB for some time, had been responsible for Honigmann’s contract with the Russians in Berlin.

What is noteworthy about this period is the fact that no reference to the Honigmann business appears in Guy Liddell’s Diaries. That could be because a) he was not aware of what was going on; b) he knew about it but did not consider it worth recording; c) he knew about it but considered it too sensitive to write about; or d) he did write about it, but the passages have been redacted. I would plump for the last. For there are indications that Liddell nurtured some serious concerns about the penetration of MI6 at this time. Long-standing coldspur readers may recall my commentaries from 2019, where I expressed my frustration with Christopher Andrew, who successfully suppressed a story he had helped air on the BBC about Eric Roberts, an MI5 officer who was transferred to MI6 and went to Vienna in 1947 (see https://coldspur.com/a-thanksgiving-round-up/ ). I wrote at the time:

Before Roberts left for Austria in 1947 (no specific date offered), on secondment to MI6 (SIS), Liddell ‘hinted that he suspected MI6 might have been penetrated by the Soviets’. On his return in 1949 (‘after just over year’, which suggests a late 1947 departure), dispirited from a fruitless mission trying to inveigle Soviet intelligence to approach him, Roberts talked to Liddell again, looking for career advice. But Liddell ‘changed the subject’, and wanted to know whether Roberts suspected that MI5 had itself been infiltrated by a traitor. He followed up by asking Roberts how he thought MI5 might have been penetrated.

One can imagine Liddell’s bewilderment (unless he had been a party to the whole scheme). A journalist of dubious merit has been selected for a position with the Control Commission. He quickly disappears to East Berlin. And then MI6 and the Foreign Office sit on their hands, declining to detain and interrogate his partner, known to be a Communist agent, yet one married to the head of Section V in MI6. And that office then tries to fob off junior MI5 officers, clearly communicating an official SIS line. By 1949, Liddell has been nobbled, too.