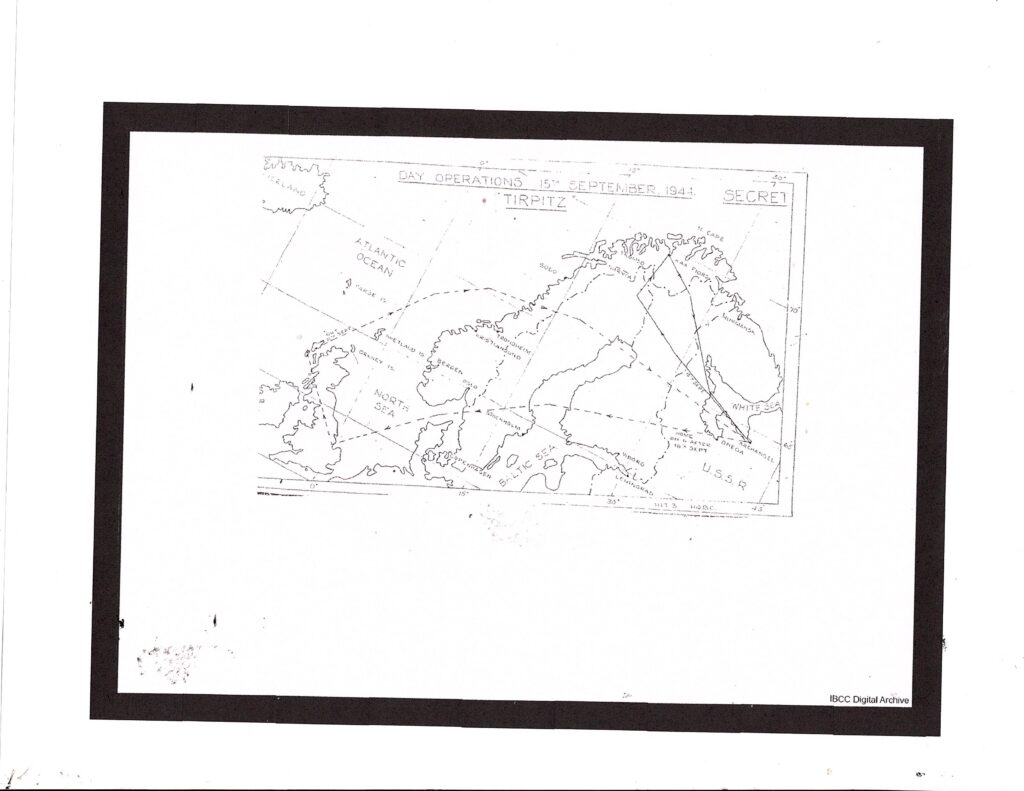

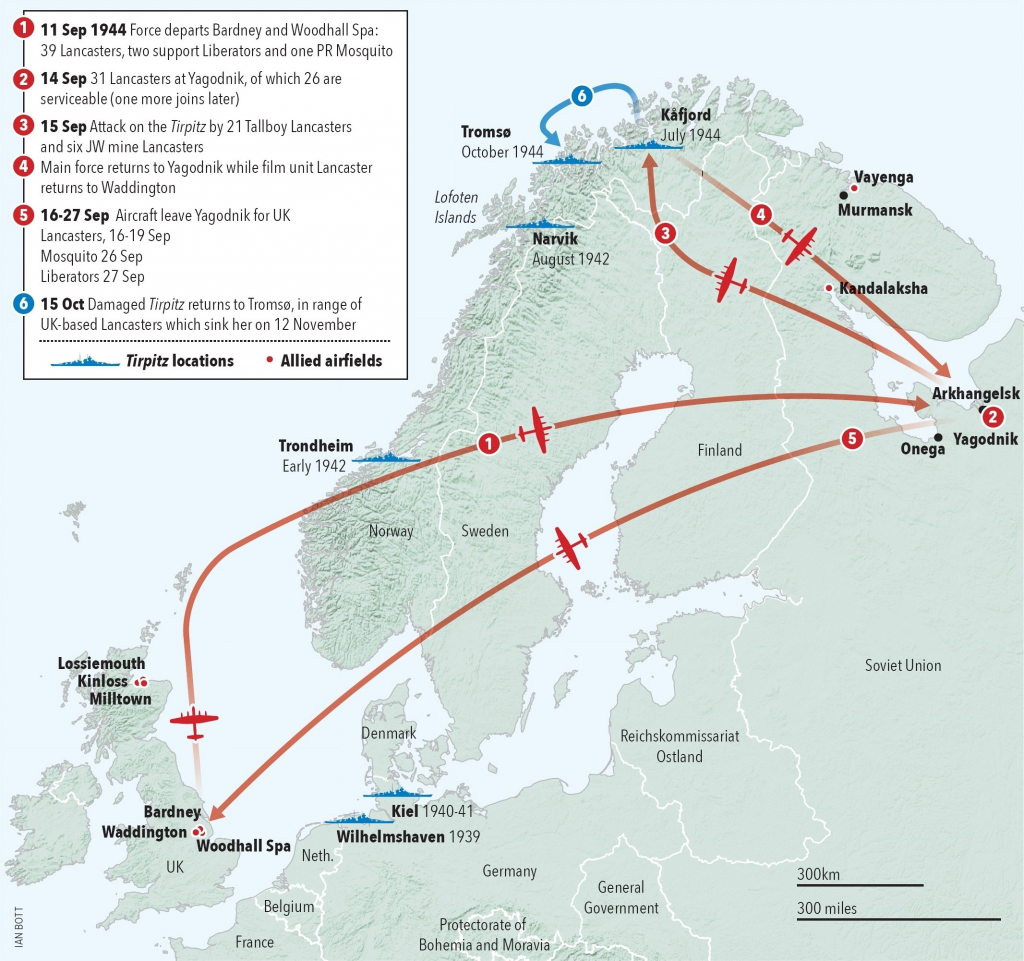

I reported earlier this month that I was awaiting the Casualty File for Flight PB416 from the Ministry of Defence. PB416 was the Lancaster bomber that crashed near Saupeset in Norway on September 17, 1944, with the loss of life of all on board – the subject of my articles on ‘The Airmen Who Died Twice’: see https://coldspur.com/the-airmen-who-died-twice-synopsis/ for the synopsis of them. The official historian of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office had encouraged me to make an application under the Freedom of Information Act, and, on July 11, the package arrived by email.

It consisted of two PDFs. The first was a standard letter, pointing out some of the security concerns that had occasioned redactions, primarily to disguise the names of relatives. Letters to such persons had also been omitted. It also described what actions I should undertake if I had any complaints about the procedure. The second was a 93-page file containing a variety of documents and photographs. What surprised me was that no restrictions on the use of the material were imposed upon me, so I judge I am free to quote, or even reproduce, freely from the material provided.

The file is very poignant – but also disturbing. It comes home to me that the registration processes shown here, which seemed very singular in relation to my quest over the individual flight that took place almost eighty years ago, must have become a sad routine for the RAF personnel who constantly had to record such mishaps. Yet the collection is also very alarming: it is fragmented, and inconclusive, and is in no way comprehensive. It complements rather the other archival information that I (benefitting largely from Nigel Austin’s predecessor activity) have revealed in my essay on the disaster. I conclude that the Squadron617 ‘historian’ has either never inspected this file, or has chosen to ignore some of its more provocative segments.

The last entry in the file is dated March 31, 1980, in which the author attempts to close out the story once and for all, while ignoring much of the archival record. (I shall return to that item later.) Perhaps a generation of interested contemporaries was dying out. The story was lost, and was relegated to a footnote. It has taken another forty-four years for the investigation to be resuscitated. My impression is that some institutional memory has endured over the decades, and enough knowledge has survived to foster the need for the incident to remain buried. My knowledge of RAF terminology and abbreviations is poor, but I hereby attempt to interpret the various reports contained.

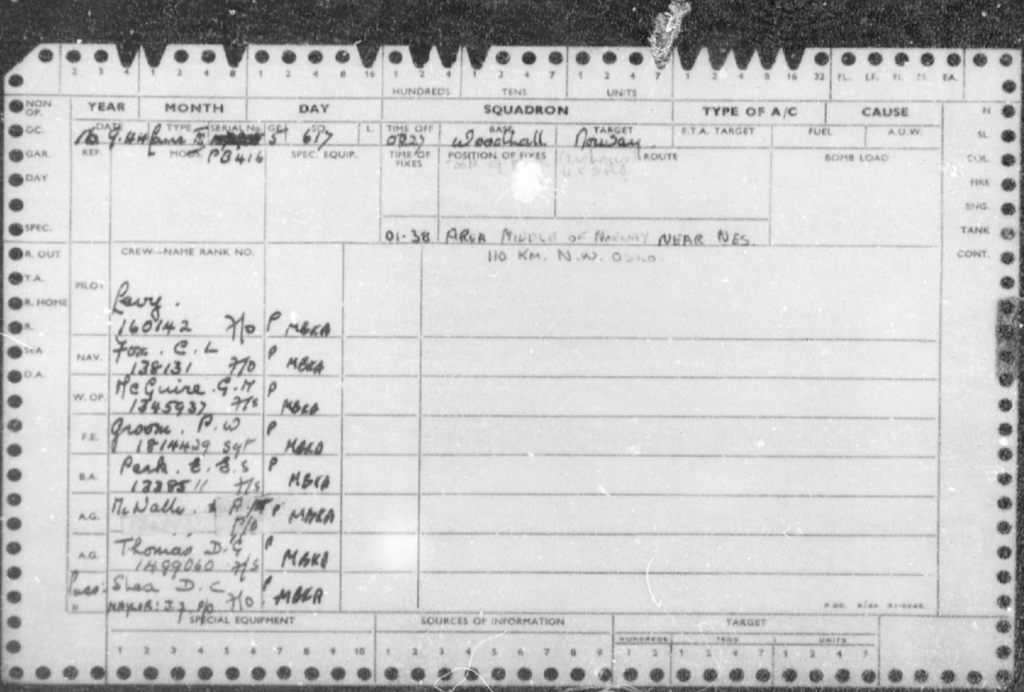

The file starts with a very plain Air Ministry statement, dated the day of the crash (17/9/1944), and simply recording the names of those airmen missing. As a foundation for the evolving story, I list their names here:

F/O Levy, F.

Sgt. Groom, P. W.

F/O Fox, C. L.

F/Sgt. Peck, E. E. S.

F/Sgt. McGuire, G. M.

P/O McNally, H. C.

F/Sgt. Thomas, H. D.

F/O Shea, D. G.

P/O Naylor, J. F.

‘Passenger’ is written under this list, reflecting the knowledge that the standard crew of seven had been complemented by two others, the result of the inability of damaged Lancasters to return from Yagodnik, with their crews consequently allocated to other planes.

An unenciphered telegram, dated September 17, at 4:45 pm, from the Squadron to the Air Ministry follows, recording that the flight was missing, ‘returning to base after an operational sortie’ – an ambiguous phrase with severe implications, as I shall explore later. It provides more details of the crew, listing next of kin (although, surprisingly, only four such connections have been redacted). It states that Levy and Fox were Jewish, a fact that has repercussions later, and confirms that Shea and Naylor were passengers. The next day, the Squadron Leader writes a formal letter to the Air Ministry, confirming the details, but classifying the incident as a ‘battle casualty’, which it surely was not. He adds that a wireless-telegraph message was received at 2:27 am BST, but does not offer the co-ordinates, merely adding that it was ‘over Norway’.

The next item is startling. It comprises a translation of a letter received via the Norwegian legation, in which a Norwegian describes how a local party of citizens was assembled to provide a ceremony for the dead airmen, and how they prevailed upon the Germans to allow them to lay a wreath on the rude grave that the local (Quisling) police had dug in the mountains, by arrangement of the Nazis. The writer describes the location of the crash, and then adds: “The entire crew, consisting of two Russian, two Australian and seven British airmen, was killed, and their identity plates were found.” He ends his script by asking whether the Red Cross could provide them with the names of the airmen’s mothers so that they might learn that some Norwegians tried to give them their last honours.

I found this astonishing – for the confidence that the writer expressed in the identification process, as well as for the insouciance over the presence of Russians among the crew. Yet it is also puzzling: if all identity plates were found (presumably the only way to determine that two were Russians), why did the local authorities conclude that two of the crewmen were Australian? A photograph of Shea’s ID-tag provided later in the file, in which all information is clearly visible, indicates name, rank (OFFR), number, and religion (C E), but no clue towards nationality. (It happens that one member was Canadian, and one Rhodesian, which leads me to believe that perhaps their status as a ‘colonial’ was included: perhaps the Germans assumed that all colonials were Australian. I seek guidance.) Nevertheless, the uncompromising assertion that there were eleven identifiable bodies, and two of them were Soviet citizens, supports my hypothesis about these authorized ‘stowaways’.

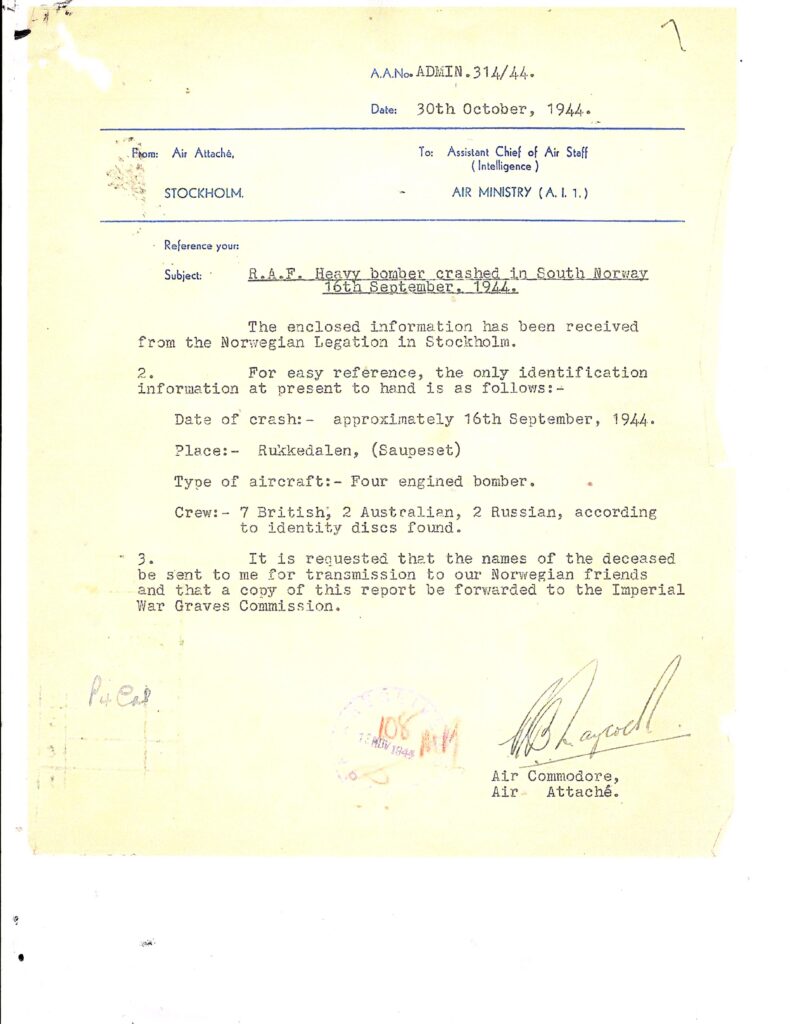

On October 30, the Air Attaché in Stockholm formally presented in a letter the same information to the Assistant Chief of Air Staff (Intelligence), and he requested that a copy of his report be sent to the Imperial War Graves Commission. The Attaché bewilderingly expressed no surprise that a pair of Russians could have been companions of the RAF airmen. Yet he went further: he was, however, explicit that the tally of the crew, seven British, two Australian, and two Russian, was derived from the identity discs found. This provocative report prompted a stern message from the Director of Personal Services at the Air Ministry, in a letter to the Commanding Officer at Woodhall Spa, dated December 4. He cites the report from Norway, adds some details about items recovered at the scene, but also shows a large degree of disingenuousness in his attempt at detective work.

The most surprising aspect is that he had up till then not recognized or confirmed the identity of the crashed plane. He lists a few scraps of clothing that the Germans had left behind, and uses the fact that one item marked ‘511 Peck’ leads to the conclusion that ‘despite certain discrepancies, it is thought that the crash is that of Lancaster P.B. 416’. How such bureaucratic stodginess could occur when a confident statement about the identity of the sole missing plane had been made the day of the disaster is incredible. Moreover, he refers to the squadron’s report about the crew of seven, and two passengers, so he must have been familiar with the details. He highlights the anomaly of the recorded eleven victims, stating: “The reference to Russian occupants may be due to the fact that the aircraft had taken off from Archangel and might have been carrying some Russian souvenirs.” He leaves unexamined the evidence (though not verifiable) from the Germans that two Russian identity discs had been found, or how the presence of a few souvenirs could have caused the Germans to lead the Germans to identify two corpses as Russian.

The officer adds a couple of perplexing details. He writes that the Germans removed everything of value from the site, leaving only four items. Apart from the Peck item (and an anonymous clothing tab), he lists ‘a clothing label in marking ink marked 544 T (?) Smith’, and ‘the remains of a pocket book marked 225/2 marked Ormestad or Ormestond’. His final request is for the Commanding Officer to verify that the co-ordinates received by W/T concerning the location of the aircraft correspond to the site of the crash, and for the mystery of the Smith/Ormestad clothing to be resolved. “Possibly one of the occupants was wearing someone else’s flying clothing.” Indeed. But the overall impression is of someone not overdosed with intelligence, concentrating on exactly the right protocol so that the office can inform the next of kin.

In his reply, dated December 12, the Wing Commander crisply tries to dispense with any anomalies. He confirms the coordinates, and echoes the vague conclusions about the challenges of identification, and the probability of the existence of souvenirs, while using the passive voice (‘it is believed’), rather than admitting to a formal judgment. Yet he completely ignores, or tacitly views as irrelevant, any suggestion that there could have been more than nine persons on the crashed plane.

The fragmented and discontinuous nature of the file is shown by the next item. It appears to be an internal memo within P.4.CAS, dated December 19, 1944, and makes it official that the Canadian member of the crew, McNally, was on the flight. In recording the burial ceremony, however, the anonymous writer concludes: “The next of kin of the R.A.F. occupants have been informed.” That strikes me as a very bizarre form of words, implying that not all of the occupants were members of the R.A.F. Otherwise, why qualify the statement with ‘R.A.F.’?

The next letter, apparently by the same writer in P.4.CAS, with the same date, is also revealing. It is directed to A.I.1, presumably Air Intelligence. It records the facts of the flight of PB416, but carelessly notes that the plane took off from Archangel ‘to return to base after having carried out an operational sortie’. This is the first occasion in which a report has openly stated that the sortie was scheduled after the plane had left Archangel, and it directly contradicts the claims that I have listed elsewhere that the plane had probably been blown off-course. I believe this statement constitutes further proof (alongside the unsurprised checking of co-ordinates) that PB 416 was on a mission to southern Norway. The writer then dismisses any notion that there could have been more than nine persons on the plane, and he lists the nine, as given above. He judges that souvenirs must have been taken as identity discs, thus pretending to counter the assertion of eleven passengers.

On December 19, the Director of Personal Services felt comfortable enough with the investigation to inform the Director General, Graves Registration and Inquiries that, indeed, there were only nine members in the crew, not eleven, and he attached the previous letter for details. On January 11, 1945, a ‘Missing Memorandum’ (no 5889) was issued, in which the status of the nine was changed from ‘Missing’ to ‘Missing believed Killed’ (MBK). The Air Ministry passed on this decision to the HQ of 5 Group, 617 Squadron. On January 8, the RAF Casualties Officer had challenged this reclassification to MBK (and to WBK – the meaning of which is not spelled out), however, and awaited further justification in a letter.

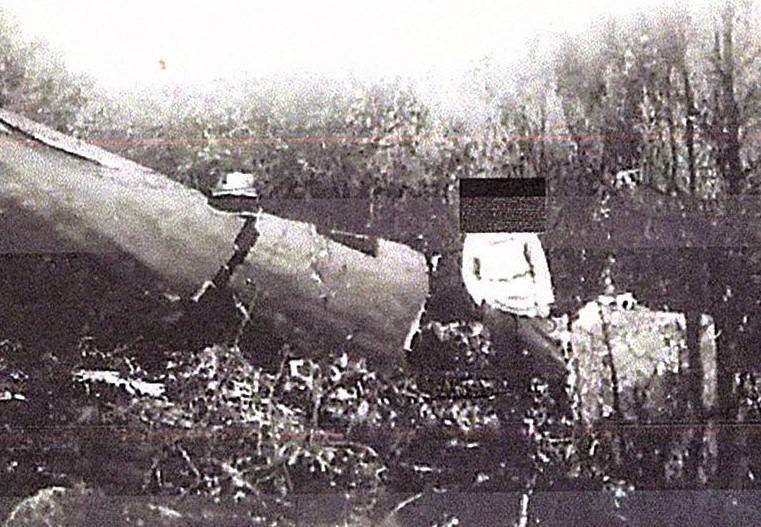

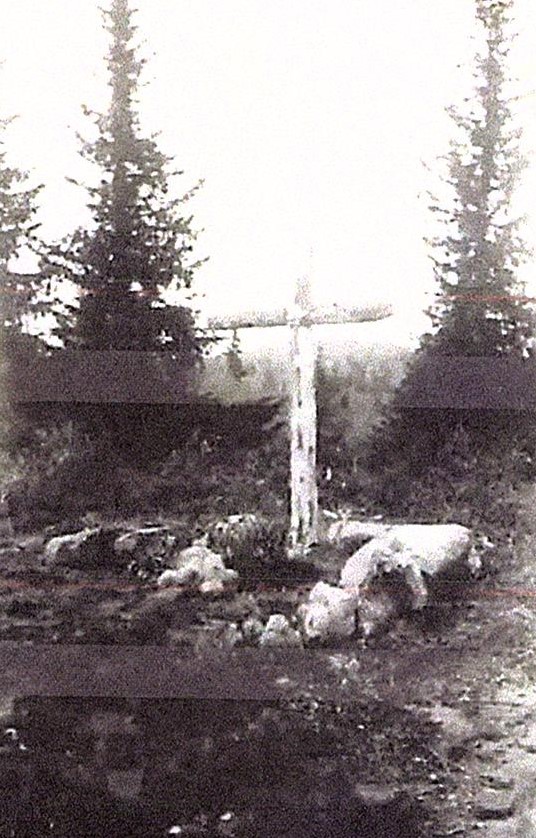

Another letter from a Group Captain, acting for the Director of Personal Services, and dated February 6, confirms the status of the dead, but allows a separate process for the presumption of death to be taken by the Canadian section in the case of McNally. This letter extraordinarily still records that ‘The entire crew, believed to comprise eleven personnel, were all killed’, without making any commentary on this enduring enigma. The letter confirms the reality of the operational sortie. Following the letter, photographs of fragments of clothing, of the cross constructed at the crash-site, and of the airplane itself, are provided.

A new twist is next provided by an undated memorandum from an address in Oslo (the identity of its owner redacted). It repeats familiar information, but comments: “Eleven men were buried accoring [sic: ‘according] to the Germans, but the Norwegians say it was only ten.” This development may reflect the testimony of a Norwegian present at the time, who was reported on social media over a decade ago as saying that he had seen a body transported from the site. The file then reverts to October 28, where the Air Attaché in Stockholm writes to RAF Intelligence that the crew was believed to consist of eleven or twelve men! Where the twelfth person came from is not explained.

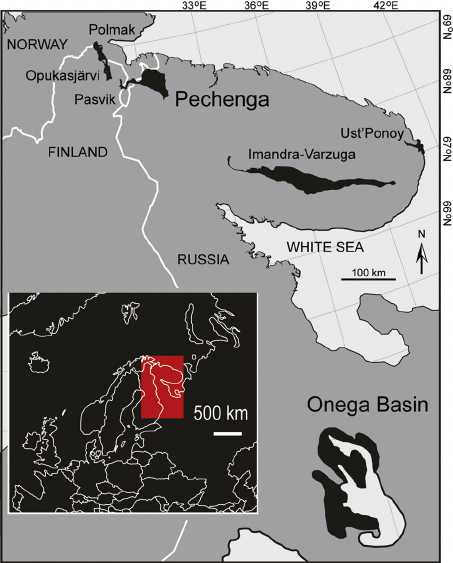

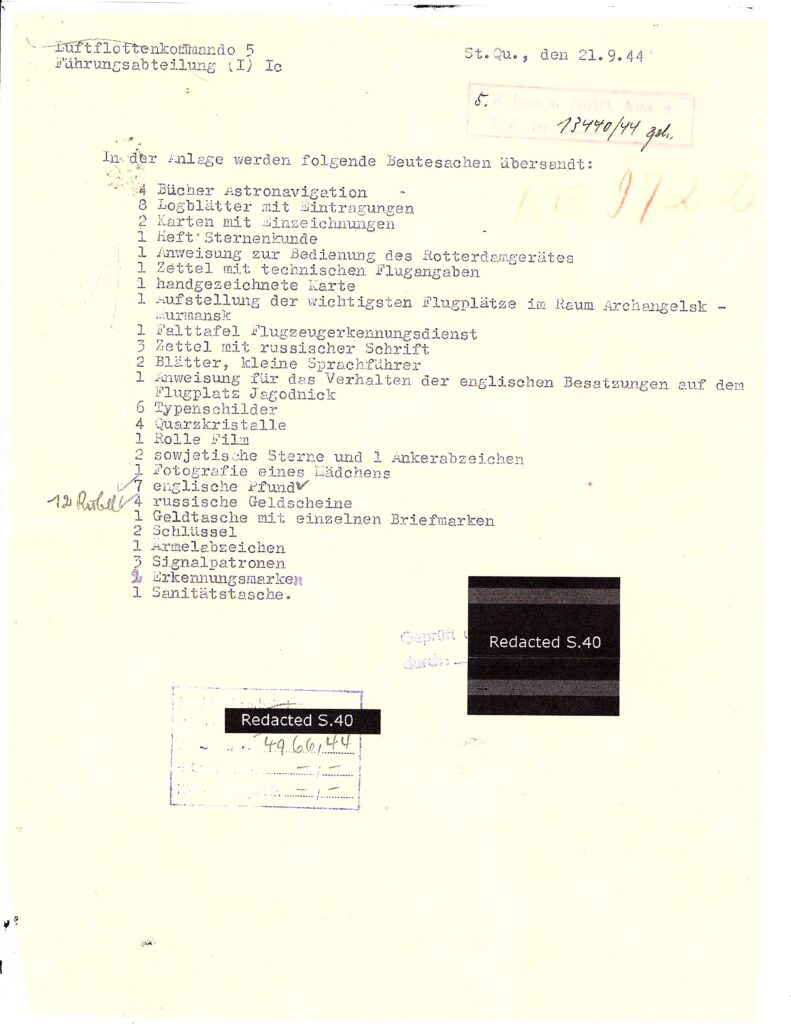

The file takes another sharp turn when some German documents are revealed. It is not clear when these were discovered, but it must surely have been after the war. The first is dated as early as September 21, 1944, and consists of a list of ‘loot’, or ‘booty’ retrieved from the site. Notable among the effects are a ‘Zettel mit russicher Schrift’ [scrap of paper with Russian writing on it], ‘2 sojwetische Sterne und 1 Ankerabzeichen’, [2 Soviet stars and 1 Anchor medallion] as well as ‘4 russiche Geldscheine’ [4 Russian banknotes]. While the latter two items could conceivably be interpreted as being souvenirs (although foreigners taking Soviet money out of the country was strictly forbidden), the scrap of paper would point indisputably to the presence of a Soviet citizen on board. The anchor medallions would suggest that at least one of the pair was a member of the Soviet navy.

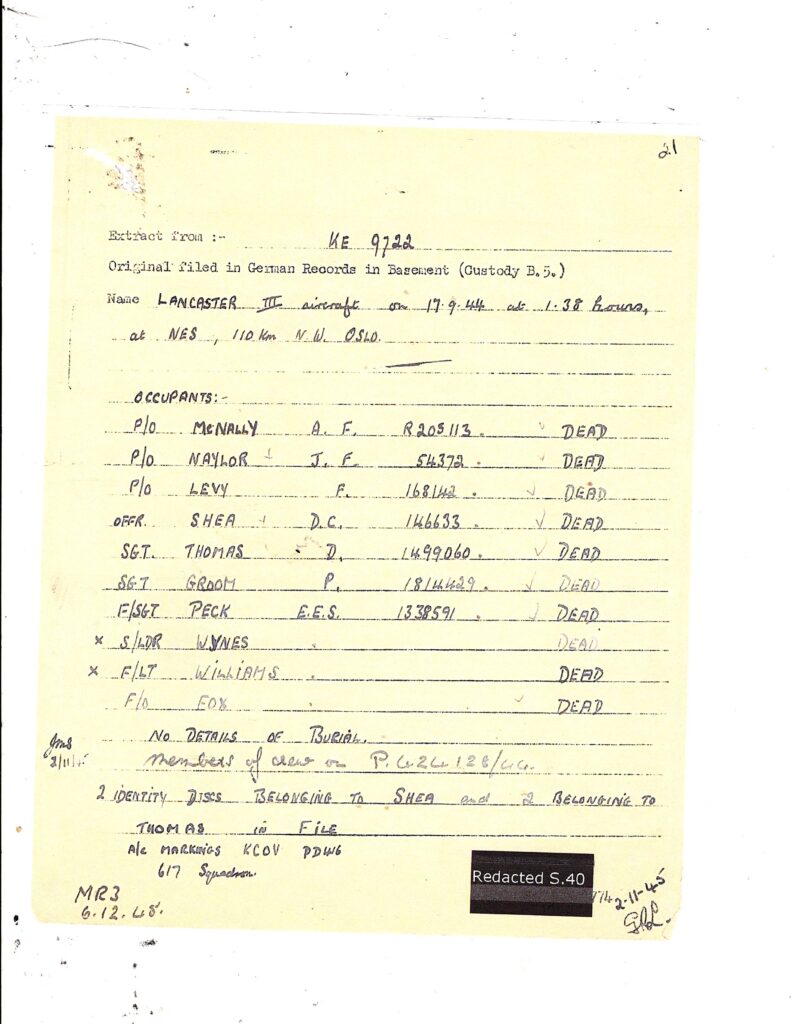

A brief report from an Oberleutnant, dated September 27, refers to the fact that the personal papers of seven crew members of the Lancaster will be handed over soon to the Air Command. It is followed by the shocking first revelation of the phantom members of the crew, Wynes [sic: ‘Wyness’] and Williams. On an official form for reporting British airplane crashes, dated January 24, 1945, ten crew members are listed, comprising the standard roster (but without McGuire), but including Squadron Leader Wyness and Flight Lieutenant Williams. Yet the latter two, as well as Fox, are listed without their ID-tag number, which is a surprising phenomenon, given that earlier reports had indicated that all the IDs had been found. This report appears to have been picked up on November 2, 1945, and is reproduced, with no apparent challenge. Yet the absence of McGuire is not noted, while two crosses appear against the names of Wynes [sic: unchanged, as if the writer is not familiar with the real Wyness] and Williams.

The Director of Graves Registration and Inquiries is confused. On October 16, 1945, he writes to the Under-Secretary of State, Air Ministry (Casualty Branch), informing him that ‘the Graves Registration Service, Norway, have been alerted to visit the location and register the grave of the nine members of the crew’, who have been interred at the top of the mountain. Yet he adds that the names of Wynes and Williams have been included, without declaring the anomaly in count, or even checking his own records, where he would have found that the two airmen were already deceased. He ends his letter by asking if the two might be correctly identified, and their ‘full Service particulars furnished’.

The request for clarification is echoed in a letter from the Squadron Leader in Oslo, the officer commanding Section 6 in 88 Group. He is addressing the Casualty Department of the Air Ministry, and requests full information so that he may supply the Graves Registration Unit with accurate information. The quota of the crew has been restored to eleven, with McGuire present again, and Wynes and Williams still in view. He adds that the GRU wants the graves to remain where they are for the time being.

This causes a flutter with the Director of Personal Services. Without offering any evidence, in a letter back to Norway, dated January 2, 1946, he asserts that the aircraft carried only nine men, and notes that ‘the inclusion of Squadron Leader Wyness and Flight Lieutenant would appear to be an error on the part of the German authorities’. I notice that this is the first time that Wyness has been spelled correctly, and the Director has obviously done his homework, as he relates how the pair went missing in October 1944. His proffered explanation is that other members of the crew had somehow been carrying some of Wyness’s and Williams’s effects with them, as if that resolved all the issues. He then sends a shorter letter conveying the same message to the Under-Secretary at the War Ministry. Meanwhile, the Director of Graves Registration is getting impatient. On January 3, 1946, he reminds the War Office that he is still awaiting a response to his October 16 letter. If he received a reply, it has not been filed.

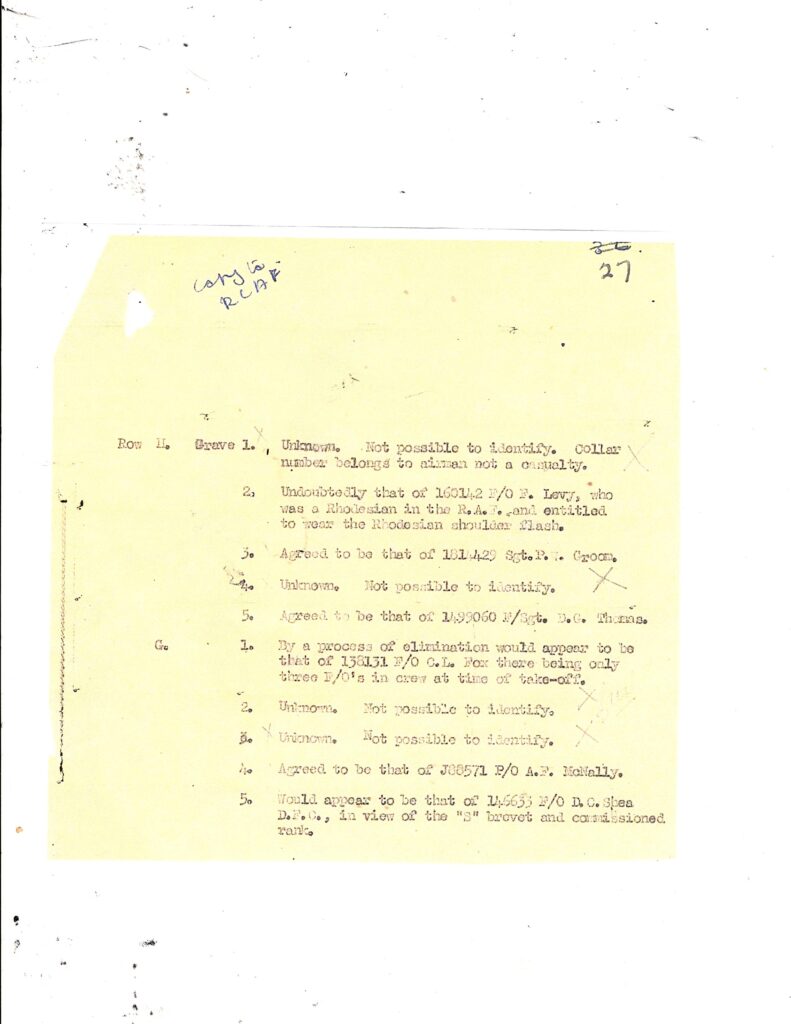

The scene then switches back to Norway, and the gravesite. An undated report explains how the bodies have been re-interred in the graveyard at Nesbyen Church, probably in April 1946. “Local reports say that eleven bodies were buried but only the remains of ten could be found,” it runs, continuing: “These were badly burned and mutilated and in all cases only parts of each body were found.” The evidence from the ground would tend to reinforce the notion that one body had been removed, while it fairly conclusively indicates that ten separate bodies could be recorded, though not confidently matched to the known crew members. The result is that some guesses had to be made.

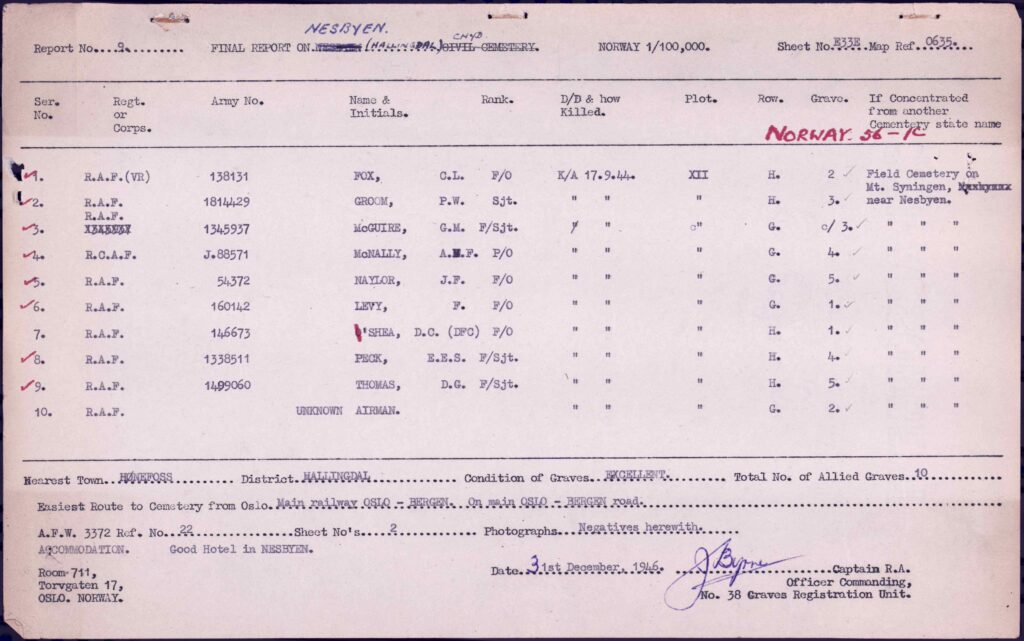

I show below the summary of the allocation of graves to victims. One extraordinary supporting note for the body placed in Row H, Grave 1, states that one of its markers was ‘part of collar bearing the number 1435510.’ Someone has inserted the name of the airman holding this number, but it has been redacted. Next to it appears the rubric: ‘Not a casualty’. A quick search on the Web reveals that Pilot Reg Payne of the same Squadron held that number, but his name does not appear in the Operations Book of the PARAVANE mission. Why his id-tag should appear in the remains is yet another mystery. What the summary does tell us, however, is that only Levy, Groom, Thomas, Fox, McNally and Shea could be confidently identified, leaving Peck, Naylor and McGuire perhaps incorrectly identified on the eventual tombstones, with the possibility (not evident to the authorities) that McGuire’s body had been removed, and that one of the Russians had taken his place. And, of course, the tenth man is the extra whose existence could not be recognized by the R.A.F.

The details concerning the body interred at G2 are fascinating: “This body was very badly burned and only part of civilian type [missing] with blue and white stripes could be found.” Whether the pattern of this clothing could lead to clearer identification was apparently never investigated, but was it perhaps a Soviet prison uniform? Why would the authorities choose to ignore this unusual but discomforting factoid?

In any event, on May 2, 1946, the Squadron Leader of the Oslo RAF mission passed on the report to the Casualty Department at the Air Ministry, pointing out the discrepancy between the ten bodies and the nine names supplied, and asking for the Ministry’s findings on the matter. The Director of Personal Services replied on July 27, seeking to close out the business. He concurred with the identification of the six above, and then wrote: “It is not possible to identify the occupant of grave 2, row G, from the civilian wearing apparel, and it is suggested [that passive voice again!] that the remains be concentrated [sic: ‘consecrated’?] to one of the unidentified graves.” Further, he recommended that the unidentified graves be registered collectively in the names of Peck, McGuire, and Naylor. He finally attempted to wipe away all controversy about the number of bodies found by referring to the general state of mutilation, which must have made counting difficult, and requested the Graves Registration Unit to accept what he had decreed.

There then follow a number of identical photographs of the graves and their markers, on which the names can be clearly viewed. These were taken in October 1946 by an unnamed tourist from Leeds who happened to be in the area. There are two St. David’s Stars (for Levy and Fox), eight Christian crosses, and, very curiously, an unmarked grave to the left. That is provocative, because photographs taken recently at Nesbyen Church, with new granite headstones provided, indicate that the number of graves has been reduced to ten. This anomaly caught the eye of the officer in CAS, and he wrote to the submitter, on February 18, 1947, that ‘the arrangement of the graves shown thereon does not tally with the arrangement quoted in the exhumation reports’, and that he would not be able to forward the photographs to the next of kin until the discrepancies were cleared. The fact that these sixteen photographs still sit in the file suggests that those discrepancies remained unresolved.

There were several problems, and the officer had to send a sharp note to Oslo the same day, pointing out that the location of the graves as displayed by the private photographer contradicted the findings issued by his office. He did not describe the conflicts in detail, but it is obvious that the presence of not only a tenth, but an eleventh, grave disturbed him, and the locations of the named victims had been moved as well. “In these circumstances”, he writes, “can it be stated please on whose authority the crosses shown in the photograph were erected and inscribed?”.

He was not to receive any useful answer. On March 1, the Air Attaché in Oslo wrote back that the addressee, ‘No 14. M.R.E.S’, had left Norway five months earlier, taking all his files with him, and he routed the inquiry to Headquarters, No. 3. M.R.E.U. In Karlsruhe, Germany. Thus the investigation was tactfully allowed to grind to a halt. The officer issued his final official burial records, all nine of which appear on file, as follows, with precise data about Row and Grave No.:

Levy G1

Groom H3

Fox H2

Peck H4

McGuire G3

McNally G4

Thomas H5

Shea H1

Naylor G5.

His instructions were followed, in the main, except for the fact that a headstone existed at G2, dedicated to an ‘Unknown Airman’ – someone that the Air Ministry did not want to recognize, although the gap would have stood out like a missing tooth. And, of course, the remains described as McGuire probably belong to the second Russian citizen.

Nevertheless, the officer received confirmation on November 26, 1947, that the graves had been shifted according to instructions, and that the registrations were correct. Oslo declined to remove the remains of the ‘Unknown Airman’, and London remained in ignorance of their durability. And that was effectively that. Apart from corrections to the named rank of Naylor and Fox, the case was closed on December 7, 1950, with the list of the dead stubbornly remaining at nine. The last entry, dated March 31, 1980, shows that one inquisitive private sleuth was trying to decipher the mystery, having seen the grave for the Unknown Airman at Nesbyen. A letter to him from the Ministry of Defence confirms that there were only nine passengers on board the flight, and the author observes: “Unfortunately we have no knowledge of the identity of the airman who occupies the grave in the churchyard which is marked ‘Known Unto God’”. That in itself reinforces the paradox: if there were only nine on board, how is it that a real but unidentifiable tenth airman could be implicitly acknowledged?

Conclusions:

This was a sad and ignoble project. The file, while straining to provide its own narrative, omits many other significant items, such as those I have displayed in my analysis. It desperately cries out for an integrated assessment of all intelligence. It is characterized by a petty, bureaucratic lack of imagination and curiosity, and a failure of anyone to take proper responsibility for resolving the many conflicts. The question cries out for attention: Why was a Special Inquiry into this tragedy not carried out at the time?

Of course, that may have been the intention – to maintain the investigation in such a state of confusion that the bureaucrats would eventually tire of its twists and turns. Someone in authority surely knew the whole story, and how volatile it would be if the truth came out, and issued clear instructions that the anomalies were not to be pursued with any diligence. And the obstruction was successful.

Yet, some irrefutable clues persist as to the nature of the deception. The last flight of PB416 is more than once described as an operational sortie over Norway, and its unorthodox course can thus not be attributed to the weather. The Germans were able to identify two of the bodies as Russians (although their technique for doing so is not clear), and the markers erected on site (which the Report does not reproduce) clearly indicate the presence of the remains of airmen bearing the markers of Wyness and Williams. Effects showing Russian heritage, including handwritten notes, which could not have been created by any of the R.A.F. crewmen, and banknotes to the tune of 70 rubles, were recorded by the Germans. Unexplained anchor medallions and ‘civilian clothing’ were found. A suggestion remains that not all occupants were R.A.F. members. The count of eleven corpses endured, despite all the efforts of the Air Ministry to quash it. It is time for the Ministry of Defence to acknowledge the patent errors and oversights that characterized the investigation of its predecessor Ministry, conduct a proper inquiry that considers all the evidence, and prepare to apologize to the relatives of all those who died.