(This ‘C’ – ‘Congenial’ – report consists of a diary of my fortnight’s visit to the UK this month, followed by a structured transcript of my talk at Whitgift School titled ‘The Cambridge Five and the Whitgift Connection’. It is dedicated to the remarkable hostess who had to deal with a prolonged stay by her guest – Anne Platts.)

Tuesday, September 2

When I started planning my trip to the UK this summer, I imagined that the largest threat to its execution might be the possibility of being arrested by Special Branch as I went through Customs at Heathrow. Little did I know that I might face greater obstacles in even entering the country. I am a dual citizen of the USA and the UK, and I have always used my UK passport when visiting my native land, as that behaviour seemed to result in a speedier passage through Immigration. But my UK passport expired in 2024, and I judged that, since I was unlikely to be making many more journeys, I might as well rely on my US passport in the future. I consequently let my UK passport expire.

I accordingly made my flight bookings via American Airlines, but barely noticed a little memorandum that talked about a visa requirement for American citizens visiting the UK. I thought nothing of it at first, since, as a dual citizen, I assumed that I would be able to sail in unchallenged and unverified. I then examined it a bit more closely a few days later, and saw that it was indeed a new regulation, introduced this year, that did require something called an ‘ETA’, an electronic travel authorization. When I looked at the rubric again, it stated, however, that British visitors with dual citizenship were not allowed to use an ETA. They had to supply proof of citizenship, namely a UK passport! This sounded so incongruous that I researched further – but got nowhere. So I visited the UK government website, and I eventually found myself number 25 in a queue (line) to ‘chat’ to a real person.

I had prepared my text, and quickly pasted it into the box when, after half an hour, my number came up. I described my dilemma, explaining that I had let my UK passport lapse, but that I was still a UK subject, that I paid taxes on income from my UK-based assets, and received pension payments through my National Insurance registration. I quickly learned that I was in a Kafkaesque predicament, a Catch-22, where my lack of ownership of a valid UK passport appeared to disqualify me from travelling to the UK. Indeed, my interlocutor advised me that, although ‘all British citizens have the right of abode in the UK’ (as the website declares), if I did not hold a valid passport, I would need a ‘certificate of entitlement’ to prove my citizenship, and gain entry. And what would it take to gain such a document? An application accompanied by a fee of £589! (This is at a time when hundreds of illegal immigrants are arriving each week on the shores of England, and being housed at public expense.)

I protested that this was absurd and inhumane, and that the policy was more generous to US citizens coming for a visit than it was for a person born in the UK who had just happened to let his UK passport lapse! Could I perhaps just turn up with my expired passport, or show other signs of UK citizenship? My interlocutor was adamant. Those were the rules, and she closed out the call, since she had nothing more to say. I had asked to speak to someone in her office, but she said that was impossible.

I gritted my teeth, had a deep think, and then re-strategized. If presentation of a valid passport was evidence of genuine citizenship, then perhaps absence of such was proof that I was no longer a UK subject, and I could thus apply for an ETA on the strength of my (primary) American citizenship? Who would know? So that is what I did. I went on-line, gave my details, scanned my US passport, offered the authorities a photograph of myself, and paid a fee of about $20. I was told the result of my application would be sent to me in about three days. Eight hours later, I received the positive email! Even though I was told I did not need to present the email on arrival, since everything was automated, I did indeed print it out, and added it my file of documents and confirmations. And here I am, landing at Heathrow on September 3.

Wednesday, September 3

The American Airlines plane cruised over the Atlantic from Charlotte at the rate of one mile every six seconds, and I was able to get some sleep by stretching out in the ingenious pod. We circled around the Epsom Stacks for half an hour, and then trundled round to the gate at Terminal 3 at Heathrow, waiting for some faulty detection device to be mended. I then had a walk of half a mile or more to reach Immigration, where an extraordinarily efficient passport recognition system allowed me to cross in five seconds, with no waiting. ETA had been sorted properly, it seemed. So I went to pick up my suitcase (which arrived fairly promptly), and went to face my next hurdle – Customs. I expected a couple of Special Branch officers to jump on me with the manacles and spirit me away. But no. All was quiet, and I took the Avis bus to drive me to the car rental centre, which was in a location far from where I picked up a car on my last visit to London eight years ago. There I decided to upgrade to an automatic: shift-stick driving has more control, and I felt quite capable of managing it still, but I thought it might be a bit more relaxing to have the decisions made for me. Contorting my neck as I did so, I stepped into a brand new Volvo, having determined what kind of petrol it needed, and where the petrol-cap was. I looked at the controls, orienteered myself, and, after reaching for the hand-brake (which feature was absent), set off to manœuvre on the left side of those busy London roads.

The next challenge was the imposition of speed limits. The Volvo knew all about temporary restrictions, and the location of cameras, and when the M40 required a maximum of 40 mph in some spots, it immediately informed me when I jogged along at 41-42 mph. The South Circular (which sounds as if it ought to be a major orbital, but which is in effect a succession of urban streets) had a 20 mph restriction, but trying to stay within that constituted quite a challenge. Moreover, whenever I slowed down to 20 from 22 (responding to the squeaks from the advisor), it seemed that buses would roar away from me at 25 mph, and impatient drivers behind me would latch on to my tail, and wait for the first opportune moment to overtake me. Should I have taken that speed restriction less seriously?

In any case, I arrived at the Battersea house of my brother Michael and his wife Susanna in good time, where I was given a great reception, and a lovely dinner with a fine choice of wines. Michael advised me that I did indeed need to take the speed restrictions seriously, as I would be spotted by cameras, fined, and given ‘points’ that would normally appear on my driving record. I might already have racked up enough points to get deported, but then why were all the other drivers so cavalier about the law? Before dinner, the two of us had walked and bussed to the EE store in Clapham Junction, where I was able to have my 2016 mobile phone – still under a contract that expires in April 2026 – given a new lease of life and a new number. As will be obvious, this model does not have a camera. Shortly before I left the States, I had tested out my excellent 2006 Canon device, only to find that Canon no longer supported a driver to upload photographs from the camera to the PC! I had thus brought my Samsung Galaxy with me (my provider in the USA not having an arrangement to operate in the UK), so that I could use it as a camera, with my iPad as a clumsy back-up, if needed. At least I had a working device to communicate with my friends and colleagues should I get lost, delayed, or arrested.

It so happened that, a few yards down from the EE store was a Waterstones bookshop that I had frequented on my last visit. I thus went in to see whether it had a copy of Gordon Corera’s new book on Mitrokhin (which will not be out in the USA until next year). Unfortunately, it had sold out, but I was able to order it to be picked up in a couple of days, and, since no elderly male Percy leaves a bookshop without carrying at least one item with him, also managed to select Richard Kerbaj’s The Defector, about Oleg Lyalin, of the publication of which I was entirely ignorant. Thus a doubly successful exploit. I managed to survive the jet-lag without taking a nap during the day, so I looked forward to a good night’s sleep.

Thursday, September 4

For this day I had originally planned to meet my London-based researcher and photographer Dr. Kevin Jones at the National Archives, to have lunch and visit the MI5 exhibition. I have been commissioning Dr Jones for about a decade now to photograph important Kew files that have not been digitized. Sometimes these requests are simple, and involve the creation of a PDF document of perhaps a hundred pages, with confidently known value. Others are more speculative, and enormous files may reveal only a few items of important interest. But that is how the system must work, and I have an arrangement by which my pre-emptive strikes in these areas may not be quickly shared with any of my competitors. The system has worked well, and Kevin has been a very reliable agent.

Sadly, he has enjoyed very indifferent health recently, and succumbed to double pneumonia in early August, a shock that required hospitalization. His doctors strongly advised him to refrain from any travel or work for a few weeks, so he had to cancel our arrangement. (I have never met him.) So I decided to visit the MI5 exhibition alone, and to perform some research while I was there. A week or so before I left, I was able to renew my reader’s card on-line, and order up a sheaf of files, namely the entire Brian Simon Personal Files, with some records of the Leslie Hollis Committee of the late 1940s as a reserve. The Simon batch was particularly attractive, since, owing to its size, I had requested that Kevin scan the files by eye himself to look for nuggets rather than photograph the whole ten volumes kit and caboodle. That task I could now do myself, with iPad in hand to take notes.

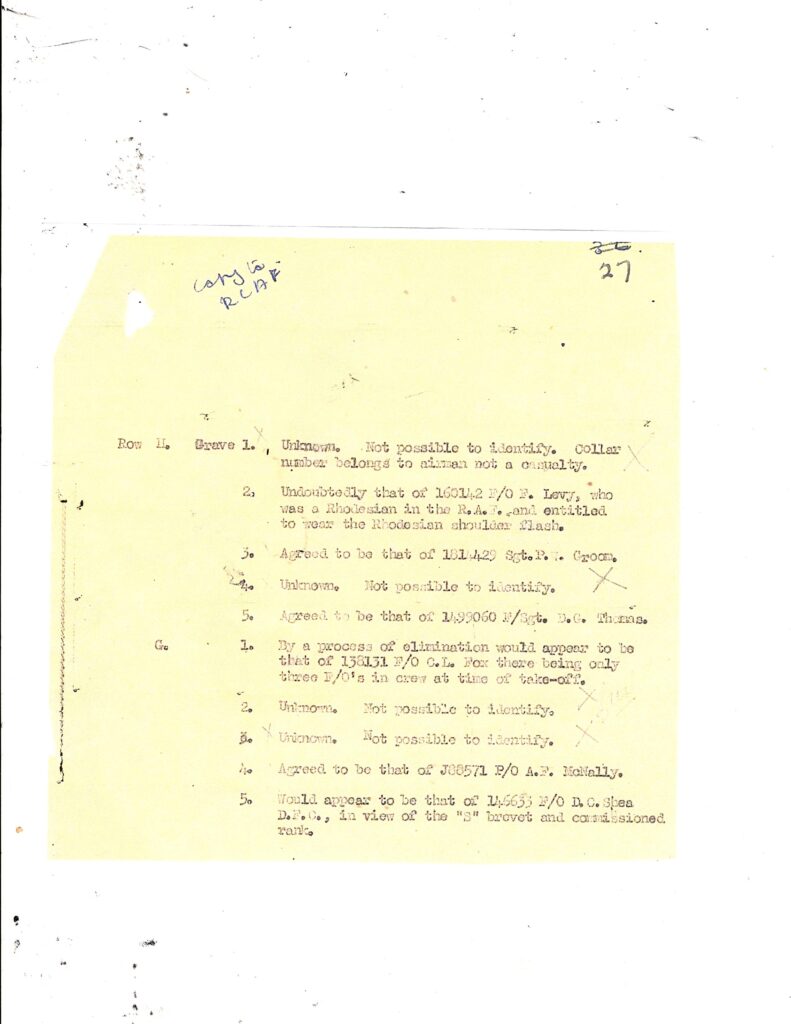

I drove down to Kew on Thursday morning. While checking in was a breeze, a major disappointment was the unavailability of the first two volumes of the Simon PF, which were already in use. Those happen to be the most interesting, since they cover the early years, when Simon’s associations with communism would have been of great relevance to my research on his connections with Peter Astbury. I processed KV 2/1477 to 2/1483 quite quickly: they were mostly boring, but did contain some gems on which I shall report at a later date. Unfortunately, the first two volumes were still unavailable at the end of the day, and had apparently been held (sitting in someone’s locker) for a while. I questioned the policy by which such selfish researchers could hog such items, and encouraged the authorities to be tougher, but received only shrugs. (This is a problem that has occurred before, as Dr Jones will attest.) Had MI5 got wind of my plans, and scuppered them, perhaps? The service must have moved pretty quickly if that were the case, as my piece on Astbury and Simon appeared on August 31, and I left North Carolina on September 2.

I did therefore have time to study the proceedings of the Hollis Committee (the successor to the London Controlling Station, chaired by General Leslie Hollis, not Roger), which operated between 1947 and 1949, and fascinating reading it was, too. (The files constituted DEFE 28/75, 28/76 and 28/77, and thus I can cancel another pending order for Dr Jones.) They describe the rather desperate and quixotic hopes of the Ministry of Defence to provide disinformation to the Soviets on Britain’s military capabilities during the early years of the Cold War. This topic relates to my interest in the biological scientist and defector Nikolai Borodin, and helps to flesh out what is evolving into a very enigmatic story. Again, I shall be expanding on this project, and reporting my findings on coldspur in the coming months.

After a good half-day’s work, I visited the MI5 exhibition. Overall, I thought this was very well done. It was curated by the gentleman who had delivered in August what I had rated to be a rather poor on-line lecture on Burgess and Maclean, but he turned out to be a much better curator than he was a historian. He was clearly guided by MI5, and I judged that the Security Service had performed a very creditable job in encapsulating the history of MI5 with some very important cases, and highlighting many of its stars. I had a few quibbles with some of the inscriptions, but the several members of the public who were also visiting seemed rapt, and for anyone not closely acquainted with the goings-on, it must have been a very educational exercise. By the time this bulletin is posted, it will have closed. (In fact I have just learned that it has been extended to November 24.)

Lastly, the excellent bookshop. I found Corera’s book there (and could have bought it without upsetting the very helpful Waterstones assistant), but instead picked up Steve Gibson’s book Brixmis: The Last Cold War Mission (first published in 1997, and re-printed in 2020) and Spies, Spin and the Fourth Estate: British Intelligence and the Media by Paul Lashmar (1920, which I later discovered I could have read on-line!). I had to persuade the clerk at the till that my Lifetime Membership of the Friends of the Archives entitled me to a discount (she wanted me to call a ‘friend’ in the back-office), and I contentedly marched out of the building to face the South Circular, and another very pleasant evening with Michael and Susanna.

Friday September 5

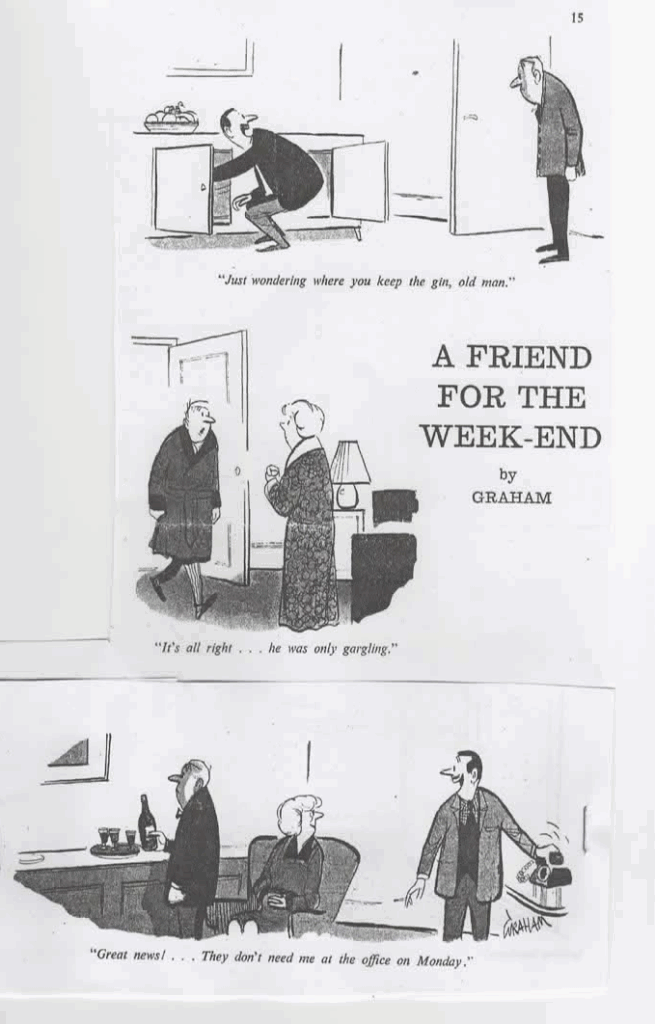

I had to return to the EE store, and then a Phone Exchange store, because of a charging problem with my mobile. That fixed, I popped into Waterstones again to ascertain whether my Corera book had arrived. It had not, so auto-drive went into action. I bought an Ordnance Survey map of Cambridge, desired for my forthcoming visit, and on my way out, noticed that they had a special deal of 50% off a second paperback. I thus was able to add Ben Macintyre’s book on the SAS assault of the Iranian Embassy, The Siege, and Ulrike Skotte’s The Umbrella Murder, the investigation into who killed Georgi Markov. I wanted to take Michael and Susanna out for a late lunch in the country, so I drove them down to the White Hart in Chipstead, Surrey. (Alert readers will recall my mention of the ‘remote and largely unexplored Chipstead Valley’ from an earlier posting). This was an excellent hostelry, in territory with which I was very familiar, but one that I never recall visiting beforehand. A very good meal was enjoyed by all, after which I dropped off Michael and Susanna at Purley station, and drove on to Sanderstead, where I planned to stay the weekend with my longstanding friends Nigel and Anne Platts. Nigel has an extraordinary capacity for recalling the rich lives of various personages from across the ages, with a store of anecdotes, most of which are probably true. He and his wife, Anne, are keen book-lovers and collectors, as well. A very enjoyable evening.

Saturday September 6 & Sunday September 7

On the morning, Nigel and I went down to Whitgift School in South Croydon, where the rugby First XV was playing Sedbergh, a power-house team, and probably the best in the country. It was the first live game of rugby that I had seen since the new laws came into effect almost twenty years ago. (I was a London Society referee after I had to give up the game, and one of my recurrent nightmares is being invited to take charge of a modern game when I do not know the new laws, and my whistle won’t work.) The skills of both sides were impressive: good handling, imaginative passing, strong tackling, and shrewd kicking. A very different game from that which I frequently played on the same pitch (but not for the first XV) over sixty years ago. At half-time, Sedbergh was leading 19-7, and looking very strong. (Sedbergh won 52-19.) We left at half-time since we had a luncheon to attend – put on for Old Whitgiftian Vice-Presidents, held at the Clubhouse at Croham Road. Another excellent opportunity to see some old friends, and to meet fresh faces.

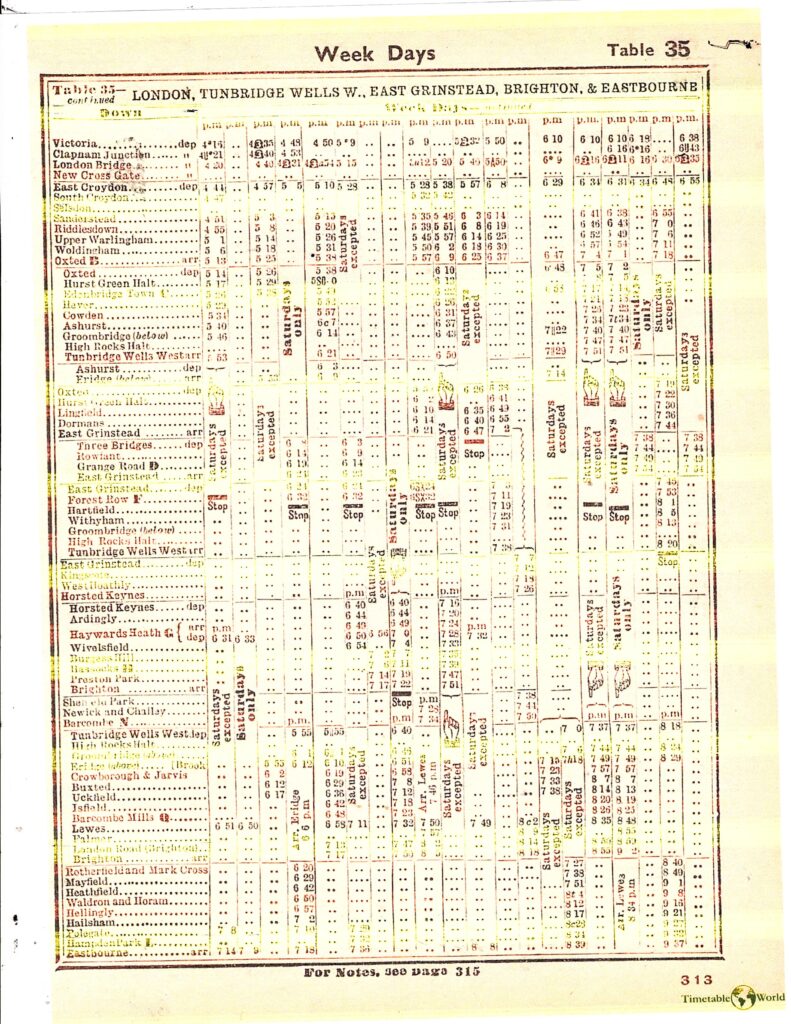

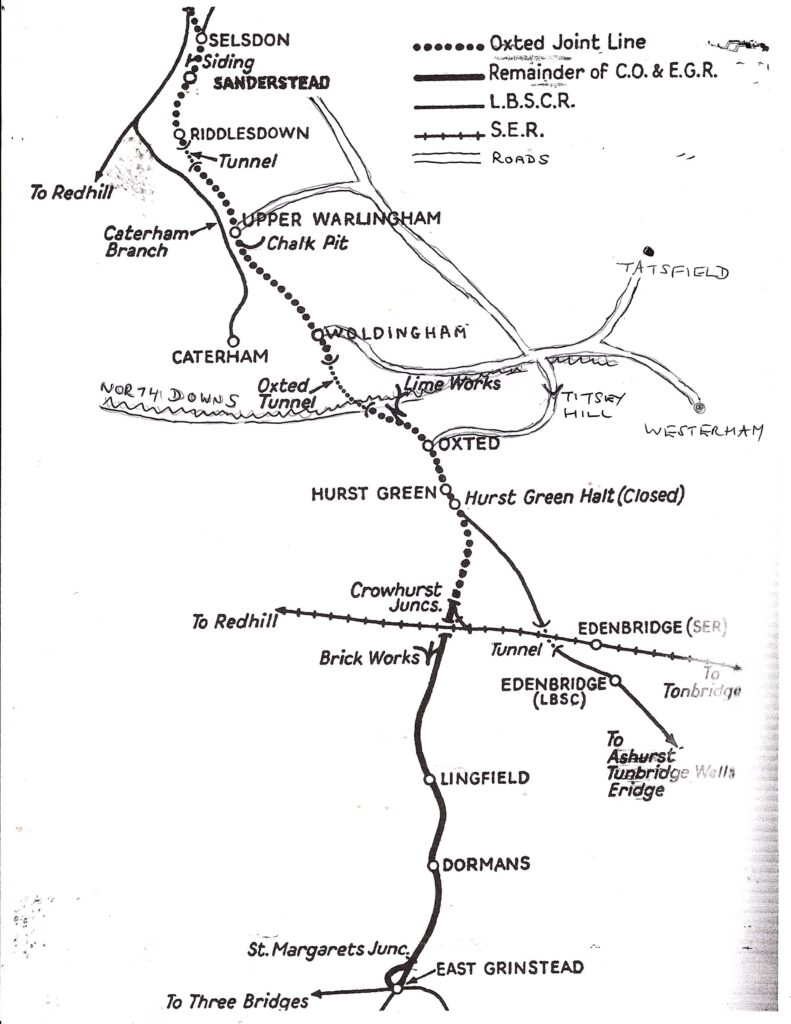

After a quiet evening with Nigel and Anne, his very hospitable and kind wife, I drove down to Oxted on the Sunday to have lunch with two other long-standing friends, Peter and Pia Skeen. Oxted is Donald Maclean country, and the Skeens live on a hill above the Oxted tunnel, near the station at which Maclean usually caught the train to Victoria in London. Peter was best man at my wedding, and I attended his in Mönsterås, Sweden, so we all had a lot of reminiscing to do. By this time, however, I had a tickle on my throat and nose, with all signs of an oncoming cold. I have lived in North Carolina for almost twenty-five years without succumbing once to the common cold, but the hazards of recirculated air in a jet-plane were probably responsible. I drove back across the North Downs (bypassing Tatsfield) to Sanderstead. An hour later I was shivering with an acute fever – my temperature was 102 F. Things looked bleak for my engagements and meetings for the coming week. I had lunch and dinner appointments in Cheltenham the next day, so I alerted my contacts that it was highly improbable that I would be able to make them. I was in no shape to take on the M25 and M40, and I did not want to risk infecting my colleagues.

Monday September 8

After a wretched night, I re-assessed the situation. My temperature was down to 100 degrees, but I was still aching badly, and wheezing. A test for Covid (the kit generously supplied by the doctor husband of the Platts’s daughter Hannah) came out negative, but it may have been obsolescent. I needed at least a couple of days’ rest. I confirmed the cancellation of my Cheltenham meetings, one of which was with the retired GCHQ historian, Tony Comer, and called off my Tuesday rendezvous with old friends Peter and Mansy Godfrey (residents of Minnesota, but fortuitously visiting the UK at this time, and staying at their house in Cirencester). I contacted Patrick Marnham (the author of War in the Shadows), since we had planned that we should dine, with his wife Chantal, at the ‘Perch’ in Oxford on the Tuesday evening. We called it off: for general health reasons, that was wise. The last remote engagements of the week were in Cambridge, on Wednesday – a reserved seat at Churchill College to study the William Strang papers, and a dinner with Professor Jonathan Haslam, author of Near and Distant Neighbours and The Spectre of War, with whom I wanted to discuss the TARANTELLA operation. Would they have to be sacrificed as well? I alerted Professor Haslam, and waited to see how my day evolved. He quickly responded, however, wisely concerned about risk of infection, and I thus went about cancelling my Churchill College and hotel reservations there.

Then my temperature rose to 104. That was not good. There was no way I could move anywhere (except perhaps to an emergency room) for a day or two. I was shivering so violently, and was so shaky and achy that I feared falling over: manœuvring the stairs was hazardous. I have had Covid before, and the symptoms were the same: high fever, aching all over, loss of sense of taste, brain fog. Nevertheless, I thought I would be capable of delivering my talk on Friday, but all other engagements were off. I contacted Peter Gillman (co-author of Death in Cairo), with whom I was scheduled to have dinner on September 11, and we agreed that getting together was not a sensible proposition for either party. Nigel and Anne have been marvellous: their weekend guest has turned out to be a regular who needs careful handling.

Tuesday September 9

I had my first decent sleep (jet lag having worked its wonders the first few days before the lurgy took over), and felt much better. My temperature had dropped to 99.5. I spent the morning sorting out my phone top-up. I had successfully added time via the phone itself shortly after I acquired it, but a call home to the USA rapidly drained the balance. When I tried to repeat the process, I went round in circles, and the system failed to recognize me. I thus turned to the EE website, and carefully entered my phone number (twice), and my debit card information, address, etc. Yet when I tried to process the request, the system rejected it simply by saying ‘Problems Occurred’, without offering any guidance as to what the problems were, or what I should do. What a shower! In some despair, I returned to the phone, and eventually managed to speak to a real person, who explained that they needed extra security checks, such as the last four digits of my Social Security Number, and my being able to inform them of the town in which my previous address (in Connecticut, twenty-four years ago) lay. I was thus eventually able to invoke the on-line system again to top the phone up, and I received a confirmation message on the device itself. Thus I was back in action, which would soon turn out to be very necessary.

Wednesday September 10

Another chance of a day of rest, I thought. Not so fast, buster! First of all, my fever was down to 98.5, which I thought was an estimable compromise between what is considered in the USA to be normal (cf. Keith’s 1966 hit ‘98.6’), and what traditionally been the accepted value in the less hot-blooded United Kingdom (98.4), in some way encapsulating my transatlantic heritage. As I started to relax with Sheila Fitzpatrick’s On Stalin’s Team, an excellent book, very well-written, with valuable insights on the relationships between Stalin’s inner circles and their wives and relatives, I was interrupted by the call of one of the neighbours of Nigel and Anne. The siren on my car, parked almost opposite, had been sounding intermittently, although no lights were flashing. What was going on? I went to look at it: the siren stopped as I approached it (coincidence, I believe), but my key was inoperative. I could not open the door to investigate, or even inspect any documentation – not that there was any, as far as I could recall. It was obvious the battery was dead – but how? I had left it parked for three days, but no lights were on.

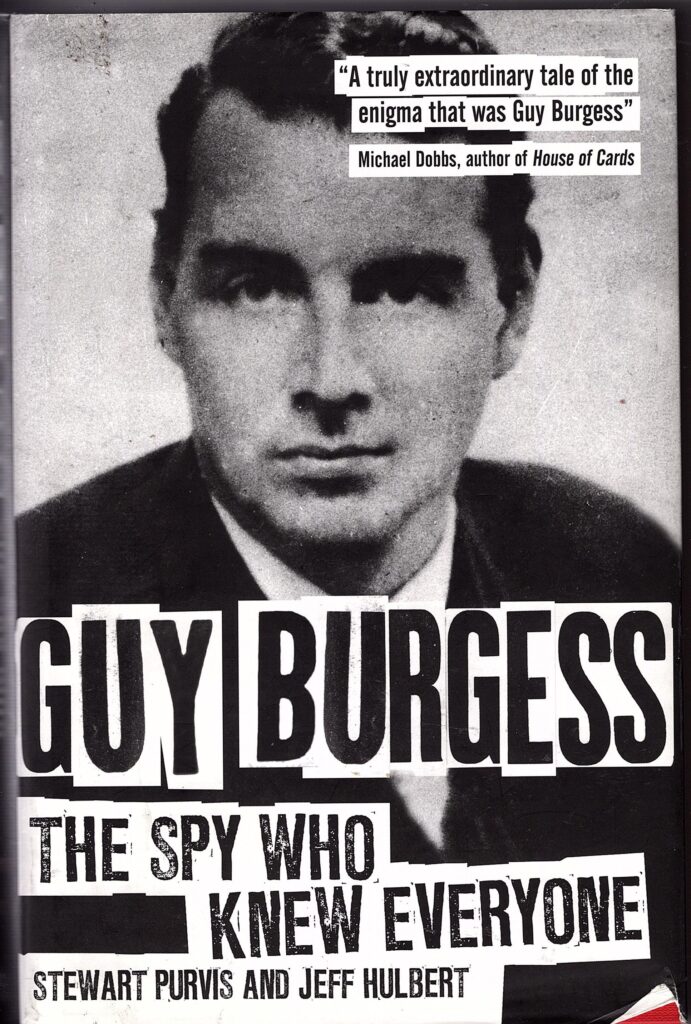

Okay – call Avis at Heathrow. I described my problem, and the girl on the desk said I had to call the AA (Automobile Association, not Alcoholics Anonymous), and she gave me the number. I repeated my problem to the AA receptionist, and she said that assistance would arrive at my location in about an hour and a half, and that I would receive a message from the representative ten minutes before he arrived. Over two hours later, I received a text message saying that he would be there at a time that had actually already passed (twenty minutes beforehand). Two minutes later, he called me on the phone, and arrived on the doorstep soon after. He had an ingenious way of opening the car, by prising out an inner key from the remote control, which he inserted into the passenger door. He set up the cable to recharge the batteries – of which there were two. The Volvo is a gasoline/petrol vehicle, and I do not understand why it needs two batteries, but, unlike Guy Burgess, I am not a petrolhead.

The technician quickly noticed that the smaller of the batteries was not filling properly, and messages confirming this malfunction appeared on the dashboard screen. I pushed him into carrying out further diagnostics, and he concluded that an internal network was sending out wrong signals, and that the smaller battery had not closed down properly, and had thus been leaking power over the past three days. This was troubling, and I expressed my desire not to drive the vehicle unless he could (reasonably) guarantee its reliability. Could the car be replaced? He thought that there was an Avis outlet in Croydon, but he must have been misinformed, as we could not find it on-line. I protested that Avis should drive out a replacement car for me, and the faulty vehicle be picked up by them, and I suggested that he contact Avis with that aspiration in mind. He accordingly did so. He was advised that the only solution was for me (the driver) to take the car to Heathrow to be replaced, as it was not their policy to help stranded drivers in that way when the car was capable of being driven. The only other alternative was to take it to Twickenham (not much nearer, and thus hardly more attractive). Nigel and I agreed that, while it would make excellent sense to return the car to Gatwick Airport, only thirty minutes away, that was probably not convenient for Avis, who required its errant motorcar to be returned to its natural home. It was clear to me that ‘We Try Harder’ was no longer the dominant thought behind the company’s policies towards its customers. Perhaps ‘We Don’t Really Care’ might be more appropriate.

I discussed the problem with the technician. He agreed that Avis’s response was arrogant and unfair, but then noted that the diagnostic message for the second battery had now disappeared, indicating that the car was probably safe to drive – and to park overnight. Perhaps I should just continue as if nothing had happened. But I had another task, irrespective of the decision I made. I had to sit in the car for an hour with the engine running, or take it for a spin, to charge it up fully. Thus, at my expense of time and petrol, I drove around the Downs in the rain for an hour, out through Warlingham to the top of Titsey Hill, then left, and left again through Tatsfield (noting the house of Donald and Melinda Maclean as I passed), through Biggin Hill, famous for its WWII aerodrome, south through Westerham (Wolfe, Montcalm and Churchill territory), and then back to Oxted, turning north up Titsey Hill. It took me about seventy minutes. I left the car outside, hoping that no sirens would disturb the neighbours, collapsed, utterly exhausted, on to my bed for half an hour before joining Anne and Nigel for a delicious cottage pie. And so to bed.

Thursday September 11

Again, I had a poor night, but looked forward to my day of rest. I still feel I have some residual brain fog from the attack: while in conversation with Nigel, certain words and names do not come quickly, and one needs to maintain a rapid and coherent flow to keep up with Nigel, and his superlative memory. I trust it will pass. I had arranged earlier in the week to speak to Tony Comer (the previous departmental historian at GCHQ) at 10:30, and we had a very interesting phone conversation for an hour on matters cryptanalytical and intelligence-related. (See his blog at www.siginthistorian.blogspot.com ) My recollection of names seemed to have improved a bit, which was encouraging. Indeed, the rest of the day was uneventful. I took another look at my slides for the presentation the next day, and tackled some more of Fitzpatrick.

Friday September 12

Another only fair night, and I woke up coughing. Fit enough to present, but I wondered whether my voice would hold. I relaxed in the morning, attending to correspondence, checking out the news on-line, and speaking to Patrick Marnham to set up a meeting in London next Monday. I then finished On Stalin’s Team, which I heartily recommend. In the early afternoon, I drove down to Whitgift School, a few miles away in South Croydon, to meet my host Andy Marlow. He gave me a brief tour of some new features and structures at the school, and then led me to the Old Library, where I was to address a dozen or so sixth-formers with an interest in History, and especially the Cold War. On the way, I was happy to encounter my old friend and ally, Atiya Bauer, Head Librarian. The schoolboys were a very smart set, seemed very engaged, and asked some excellent questions. A short breather, and a very pleasant meeting with the new Headmaster, Mr Toby Seth, an impressive person, engaging, authoritative and obviously extremely competent. Whitgift will be in good hands, and I am happy to help the cause.

I had arranged a small reception for the attendees at my talk ‘The Cambridge Five and the Whitgift Connection’, and was happy to see some old friends whom I had not seen for decades, including him who had travelled the furthest, David Puttock, alongside whom I studied German and Russian at Whitgift, and who preceded me at Oxford by a year. He had travelled from Ontario – probably not solely to witness my presentation – but I was glad to add further substance to his schedule. It was a remarkably eclectic group of over a hundred persons – Old Whitgiftians, some with their wives or partners, masters and former masters at the school, schoolboys, some with their parents, outsiders who had learned about the event through coldspur. Some whom I had hoped to see had to cry off at the last minute, but I was very happy with the turnout, and the interest showed.

I think the talk went well, although it is not really for me to say. I was not on tip-top form, my voice was a bit hoarse, I stumbled over one or two names, and omitted one or two relevant anecdotes. I tried to draw a broad-brushed scenario for those for whom the fiasco of the Cambridge Five was all a mystery, while providing enough provocative detail to show that there were some breakthrough findings in what I had to say. (The more formal transcript appears below.) The presentation was received with strong applause, I have to say, and again, I received some very penetrating questions. During further refreshments, I enjoyed many much appreciated conversations with happy attendees, including a remarkable exchange with an Old Whitgiftian from Nottingham who had been at the school from 1943 to 1950, who had not been back to it in seventy years (!), and who presented me with a remarkable note made by his father-in-law, who had joined MI6 in 1946. The memorandum made an astonishing claim about a sudden stop to GCHQ’s decryption of Soviet messages in 1951, which I must investigate when I get home. Lastly, David Puttock, Michael and Susanna and I [not ‘and myself’, please note] left for a good meal at Bagatti’s in South Croydon. I dropped David off near his hotel (okay, not that near, as the streets of central Croydon confused me), and returned to Sanderstead for a well-earned sleep.

Saturday September 13

Today’s event was one of the original attractions of my visit: a re-union of School Prefects from 1965, which Chris Singleton had kindly arranged to coincide. It was held at the ‘Horse and Groom’ in Belgravia, namely at the same hostelry where the last get-together took place in 2017 (see https://coldspur.com/polarbear-has-landed/). Unfortunately, only six of us attended: Paul McCombie and David Kirk have since died, and health reasons prevented a couple of others from appearing. David Earl was a late-no show. Thus a quartet of Singleton, Flood, Rawlings and Percy maintained continuity, and I was very pleased to see the very spry Gordon Aitken and Brian Caswell for the first time since 1965. A group of six allowed more liberal interchange, however, and we had a very enjoyable time. My meal was disappointing: I chose chili con carne, since it is difficult to get the classic dish in North Carolina, but there were not enough beans in it, the meat concoction had too many extraneous substances in it that interfered with the primary taste, and the rice was far too chewy.

I walked with Tim Flood to meet with Nigel Platts (who had been attending a similar reunion of 1955 classmates in London) at Victoria Station. The terminus was milling with all sorts of persons from every nationality, every region of the world – I might even say every ‘race’, which is a word I avoid – who looked in a rush to locate their train as if they had been a swarm of commuters in 1975. They could not all have been tourists, as East Croydon and Crystal Palace stations are not normal destinations on the ‘what to see’ guide, so I assume they were citizens or fairly permanent residents going about their weekend business. On a coolish and damp Saturday afternoon, many of the young ladies were dressed as if they were setting out for Santa Monica beach, which was startling, to say the least. I thought the variety and bustle were all rather grand: London presumably still has its attractions as a cosmopolitan city, with much varied entertainment, and is the capital of a country where the secret police do not knock on your door at 3:00 am, but it puzzled me how it keeps going, and how long it will take to be bankrupted. How do people afford everything? And how long will this disastrously incompetent government keep going? Its leaders have no clue at all about economics, and dreadful old mischief-makers like Neil Kinnock are dragged out to compound the chaos. What I do not understand is the relentless urge to tax anything that is considered antisocial or immoral (such as illiquid assets, horse-racing, or independent schools). While the government will exploit the short-term revenues gained in order to balance its budget, if it is successful in its campaign of righteousness, the source of revenues will inevitably decline. And then it will have to find another target. Madness! The current situation reminds me of the 1970s, with the three-day week, and rampant unions, and a road to economic horror that might require the IMF to be brought in eventually. (I left the UK in 1980.)

Sunday September 14

I left Nigel and Anne with fond farewells, expressing my deep gratitude for all they had done for me during my indisposition. I was the guest who came for a weekend and then stayed nine nights: their hospitality and kindness could not have been greater. In the morning I drove back to Battersea, encountering horrendous traffic almost everywhere, but not letting myself be flustered by drivers who judged that I was leaving an intolerably large distance between the car in front of me and the Volvo, and I remained patient when some unreasonably wedged themselves in front of me. I had a little lunch, read the Saturday paper, and took a little nap before we set off for Stratford to meet the families of Michael’s two sons.

Stratford is in North-East London: the Olympic Stadium is situated there. For most people who live in South London, I believe that North London is terra incognita. I have never been to Stratford or Hackney, and I had to find out exactly where they were on the map. Our plan was to walk to Clapham Junction Station, get a train to Waterloo, and thence take the Jubilee Line. Quite simple. But when we trekked down into the bowels of the earth to pick up the Jubilee Line, we found that it was closed. So we returned to pick up the Northern Line train, where we transferred at Tottenham Court Road to take the Elizabeth Line to Stratford. Quite a lot of walking involved, but, after all, there was an alternative plan without going overground. (It was a miserable day, with heavy rain). Thus we disembarked where the line surfaced, in Stratford.

North London looks remarkably like South London – tower blocks, a few allotments, terraced houses, and the customary muddle, with spray-painted slogans daubed on practically every open surface. The natives are similarly polyglot. We had to walk half a mile or so to find the Gordon Ramsay restaurant where we were meeting Alexander, his wife Victoria (whom I had never met) and their six-month-old daughter Astride. Jonathan and his son, Oliver, and daughter, Felicity, who drove in from North Essex were already there. Sadly, Jonathan’s wife Pippa could not make it. After some warm introductions, we sat down to inspect the menu.

My spies inform me that Gordon Ramsay is what is known as a ‘celebrity chef’, and that he has opened a chain of restaurants presumably designed to show off his talents. I thus eagerly selected the beef with Yorkshire pudding, as that is fare I have not enjoyed for a while. Three of the party made the same choice, but when the dishes arrived, I noticed that they were lacking the prime ingredient – the pudding. On being questioned about this, the waitress informed us that they ‘had run out of Yorkshire puddings’. Poor Michael (our host) was as disenchanted with that news as was I. The waitress had omitted to tell us that there was no pudding available when she took our order, which was unpardonable. But ‘run out’? Did they order them from Sainsbury’s? Could Ramsay’s representative not have conjured up some more from the ingredients they must have held in the kitchen? (Moreover, the dish was ornamented with something called ‘kimchi cabbage’, which was surely not a fare offered up in Barnsley or Bradford where this dish had its roots. Where were the carrots, peas and cauliflower?) It was all a shame, and it shows how the hasty expansion of a brand name can swiftly lead to its debasement, but we made little of the problems so as not to spoil a wonderful occasion.

The return journey allowed us to use the Jubilee Line again, as it had since re-opened. Some more long walks, and a light drizzle, and I was very happy to slump into an armchair, check up on the golf scores, attend to text messages from my daughter, Julia, and fall into bed. Michael and Susanna had to get an early train to Brussels the next day. I had a more relaxing prospect ahead.

Monday September 15

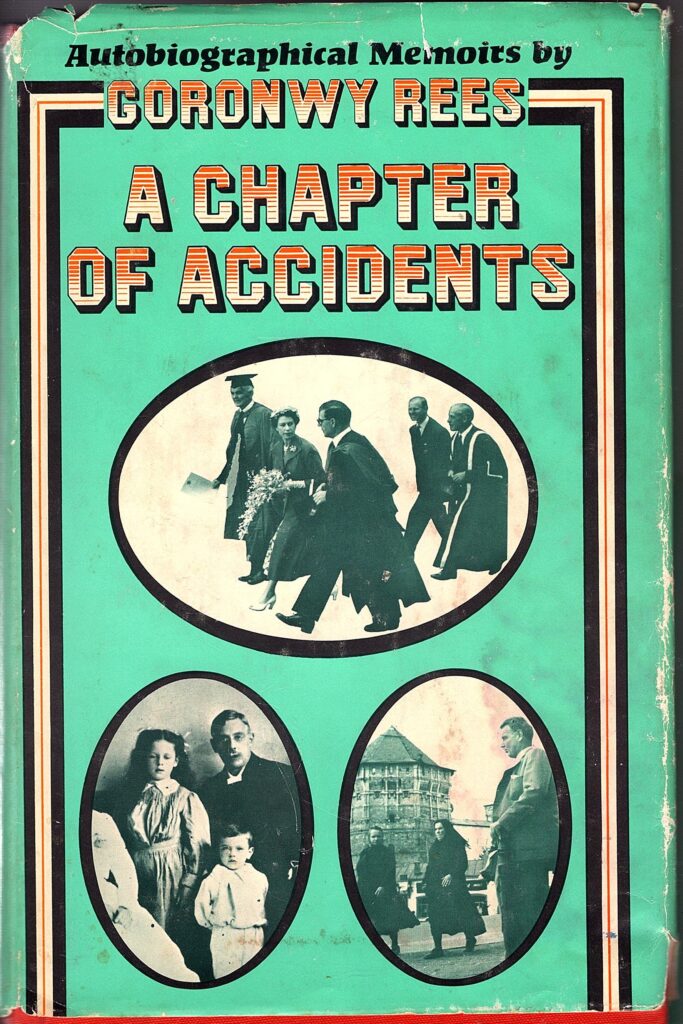

I had arranged to meet Patrick Marnham for lunch at a little cafe near the London Library today. I had offered to drive up to Oxford, but, since he wanted to visit the Library, we agreed that meeting near the Library would be a good idea. I left in good time, allowing myself an hour or so in Waterstones further up on Piccadilly before our 12:45 engagement. I needed to pick up a special book for our daughter Julia. I was there in plenty of time – but Patrick did not turn up. For some reason I could not reach him on my mobile, which had been working perfectly a couple of hours beforehand, so I simply bought an excellent bacon and cheese sandwich, and made my way back to Battersea. Lots of walking! From the house to Clapham Junction, to the train, through the concourse to the Underground, to the Victoria Line entrance, round a devious path out of Green Park Station, up to Waterstones past Hatchard’s, and back to Duke Street St James to the cafe. Then all the way back again. My feet and legs were utterly worn out. I arrived at Michael’s house and called Patrick. This time I got through: Patrick was stranded in a train somewhere between Oxford and Paddington since some idiot had pulled the emergency cord, and the line was closed. He had been unable to contact me. A chapter of misfortunes.

So I made myself a cup of tea, and prepared for the next step – driving to Heathrow to stay at the Ibis hotel, where my car would be parked during my final expedition into Central London tomorrow. I was all packed, and ready to go. So I took my suitcase out to the car – and found that the car’s battery was flat again! The second time in six days! If I could just get the car to the Ibis, I would happily have nothing more to do with it, and, if it didn’t start on Wednesday morning, I would tell Avis to tear up my invoice and to pick up the wretched automobile themselves. The AA were due in Battersea at about 4:15. I had plenty of time. I had pre-registered at the Ibis on-line, indicating I would probably arrive between 3 and 6. So I just sat and waited and updated this diary.

The service guy arrived early, and checked out the previous record. He ran his tests – not good: it looked as if the transmission was dodgy, and the car should not be driven. He was Polish: while we waited for the battery to be charged we discussed Polish-Ukrainian relations, and Stepan Bandera. He valiantly volunteered to follow me to the Avis terminal at Heathrow, in case I broke down, and committed to describing to the Avis agent the condition he had found the car in. This he did: it was a long haul, but we found our way to the counter. When I explained that I was returning the car early, as I wanted nothing more to do with it, and instead sought a large discount, the agent was unbending. All he could do was waive the tank refill charge (I had obviously not filled it up), and give me a day’s fee off. I would have to write to Head Office to seek any more reparations. (Hang on there, Avis: the letter will be on its way soon.) Needless to say, I received an email survey ten minutes later, asking how delighted I had been with Avis’s service. That was not good for my neurodivergent state.

So I had to get a taxi to my hotel, wait in line at the front desk for twenty minutes, and then had to remonstrate with the clerk that my two days’ parking fee should be rescinded, go to my room to freshen up, and hasten to the bar for some much needed refreshment. There I had to stand in line at the bar for twenty minutes to give my order. The draught cider was off, so I selected two bottles of Kopparberg Premium Cider with Strawberry and Lime, and a nice gammon steak with peas, egg, and chips. That, at least, was quite good. What could go wrong tomorrow, I asked myself? And what is amiss with this country, that so many things go awry, and nobody knows how to address the customer satisfaction problem?

Tuesday September 16

My night in my cell at the Ibis was reasonable – a little austere, with no bedside telephone to ensure a wake-up call, or to ask for room service. The KGB goon looked through the peephole every hour to check whether I was still breathing, and I awoke early, to give a dry-run for the whole transport procedure tomorrow. Today I was visiting the UCL archive in Bloomsbury to inspect some of the Brian Simon papers, and planned to take the Elizabeth Line on a fast link to Tottenham Court Road, change to the Northern Line for Goodge Street, and walk the half mile or so to the Library. After a good breakfast, I took the shuttle from the hotel, due at 9:36. It was late, and went via Terminal 3 to Terminal 2 and the Underground. I then had a long walk, and boarded my train at 10:25. Oh well! I didn’t want to spend too long in the archives, anyway. I had pre-selected what I judged would be the most important papers. It was quite a hike from Goodge Street to the Library: armed with my iPad, I arrived at about 11:15.

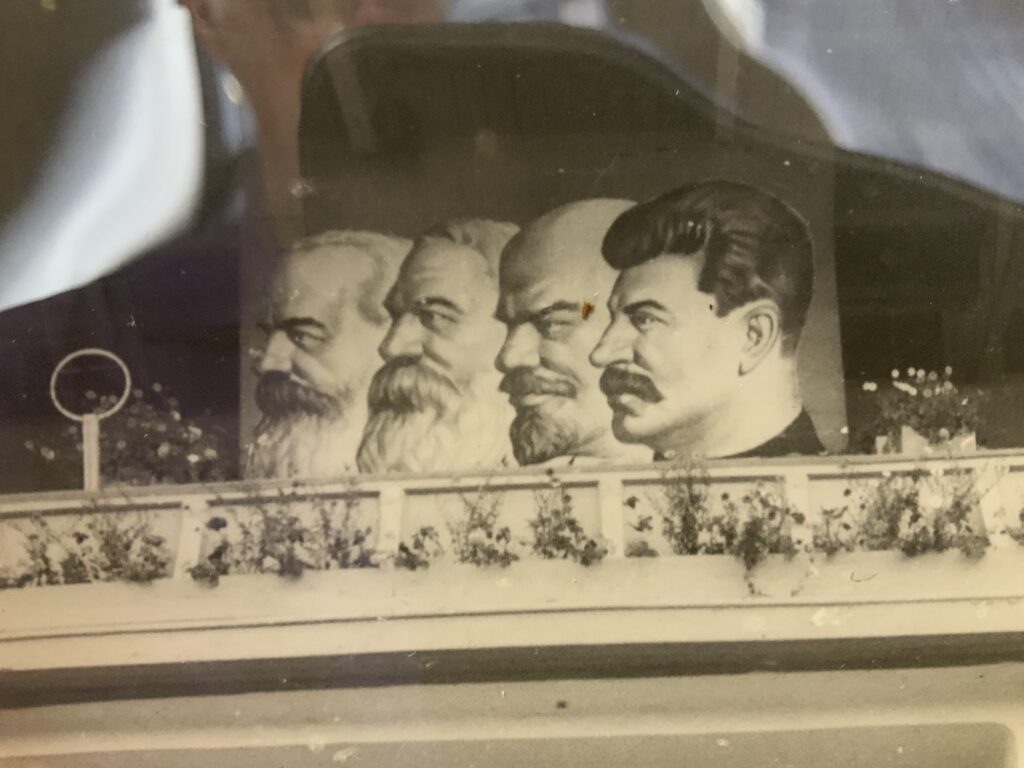

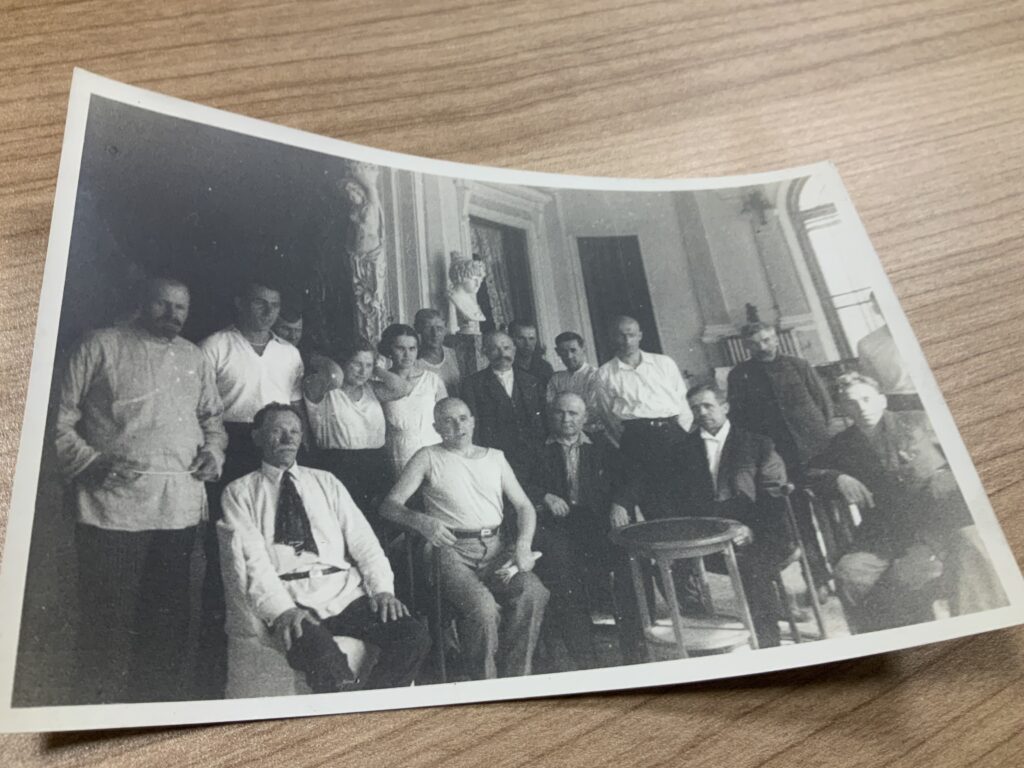

The staff at the Library were (was?) very helpful. Several large boxes of files were presented to me, and I started off on SIM/6, described as Simon’s ‘Visits Abroad, ca. 1935-1990’, with 6/1 specifically dedicated to his visits to the Soviet Union. Yet there was no written record of his voyage to Leningrad, Moscow, and beyond with Anthony Blunt in 1935, the boxes starting in 1956! I found, in SIM/4/5, some correspondence between his brother Roger at the time. Roger was writing on Intourist notepaper, which seemed a bit strange. When I get back home, I shall have to investigate whence the accounts of Simon’s impressions of the Soviet Union come: they may have been ‘mis-placed’ elsewhere in the files. I did not have the time or energy to dig around any more. After re-inspecting the file, however, I concluded that a set of photographs (in 6/1/1) may be all that represents his visits to the Soviet Union in 1935. They are undated, but one prominent one suggests a younger Stalin, and two postcards (of the Moscow Metro, and of Sverdlovsk Square, now known as Theatre Square, in Moscow) bear the dates of 1936 and 1935. Thus Simon must have made a return visit. Indeed, from an inspection made of Simon’s PF KV 2/4175, since photographed by Dr. Jones at the National Archives and sent to me, I note that the immigration authorities noted that they had failed to pick up Simon’s second journey to the Soviet Union in 1936 or 1937, while confirming that he had recently paid a visit there. He probably entered clandestinely from another country rather than travelling on a Soviet vessel.

I did find, however, some notes that Simon made about his time at Gresham’s School, Holt, his mentorship by McEachran, and his friendships there with such as George Klugmann and Brian Floud, which was interesting. After Gresham’s, he went for a year to Kurt Hahn’s school at Salem in Germany. Hahn was a vigorous critic of Hitler, and thus had to escape, after which he founded Gordonstoun. Simon may have been influenced by Hahn. The exact dating of his commitment to Stalin remains evasive. In summary, the files represent the sanitised memoranda of a decades-long communist and admirer of Stalin’s Soviet Union, carefully omitting anything that might be considered incriminating. There is an opportunity for a dedicated researcher to plough through (for instance) all those love-letters to his wife written from GHQ Liaison Regiment, or a curious exchange with his brother Roger when the latter was apparently working for Intourist, but I am not that person.

I then made my way to Shepherd’s Bush, to have dinner with Richard Davenport-Hines, author of Enemies Within (and many other works), who had kindly invited me to his home. (He was over from his home in France, and flying on to Prague in a day or two). I decided to go to Russell Square Underground Station, quite a bit nearer than Goodge Street, and changed to the Central Line at Holborn. I surfaced, having familiarized myself with the map, but had to orientate myself by the sun, as there was no ‘You Are Here’ arrow on the map provided, and I would otherwise have had no idea on which arc of the circle I was. I found a Waitrose to buy a bottle of wine, and then sought solace at a bar that served me a delicious draught cider that refreshed me after a hard day’s walking.

The evening with Richard was delightful, and diminished all the disappointments I have had. He is a very charming man, and we have identical sentiments about what is written on intelligence by journalist and historians. We filled in little cracks in each other’s stories; he told me about the new book he is writing about David Footman and others, and I updated him on some of my latest research, which he has not had a chance to inspect yet. (He has a natural preference for paper-based research, and I committed to sending him Word versions of a few select bulletins, a favour I am prepared to give for anyone who asks.) Richard asked me to sign his copy of Misdefending the Realm, a ceremony that occurs only too rarely. Instead of making another late trek across London’s Underground and mainline stations (Shepherd’s Bush does not link well with other Underground Lines), Richard called an Uber to ferry me direct to the Ibis hotel on the Bath Road, and I consequently arrived before 10:00 pm to have a nightcap, check my email, send a text message to daughter Julia, and update my diary. All set for an early departure from the hotel tomorrow morning.

Wednesday September 17

Everything went smoothly this morning, and, having caught the 7:36 shuttle bus from the hotel, I was installed in a seat in the Admirals’ Club by 8:15, with plenty of time before my 11:00 flight to Charlotte. This has been a gruelling trip, and several persons have asked when I shall be coming back. I have some unfinished business to fulfill, but the wear and tear to the body (and mind) makes travelling very arduous. Most of all, it is the walking. I could get a wheelchair at the airport, but moving around London contains hidden struggles. The Underground Stations look deceptively close for changing lines, but the walks to the entrances, and from the entrances to the trains, and from the trains to the connectors, and thence back to the outside world, with a further walk required, placed painful strains on my damaged leg, and especially my gammy left knee, for which the right leg tries to compensate. Overall during my stay, too many steepish stairs or steps, some with too shallow treads, and lacking handrails. At the end of each day, I was close to toppling over. And then there is all the hassle of dealing with British immigration authorities, hotels, mobile phone suppliers, car rental companies, and celebrity chefs. Driving around the suburbs of London is a hazardous business, and I found the constant series of alarms and beeps from the dashboard of the rental car distracting. Payment for everything was, however, supremely simple, my NatWest debit card being ubiquitously useful. On the other hand, I had trouble understanding most people: my hearing is a bit impaired, but the London Mumble, delivered with every variety of unfamiliar accent, made me feel very often that I needed an interpreter.

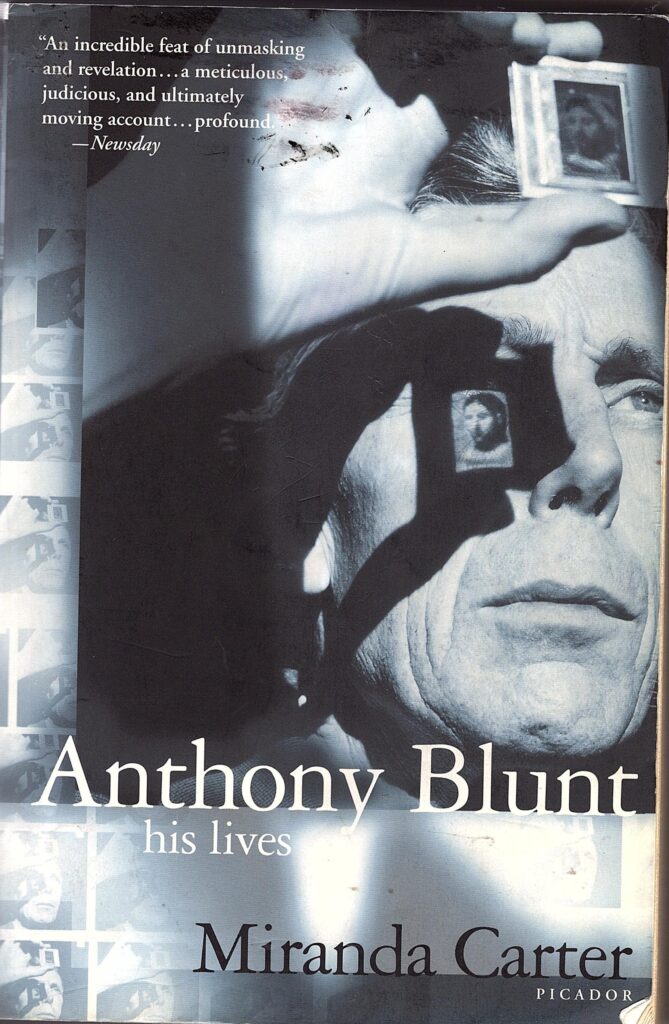

We took off half an hour late, at 11:30. Another long walk from the Club to the gate – where we then had to embark on a bus, and face more steep steps. Heathrow is obviously overloaded. A comfortable journey back. After a tasty curry lunch, and a good nap, I again got my teeth into Robert Verkaik’s The Traitor of Arnhem, which I had read earlier this year, but this time set out to inspect very closely the claims he makes about Anthony Blunt. I made a good deal of progress, identifying errors and anomalies, as well as listing important sources in the Endnotes that require following up, although switching to the task of entering my observations in Apple ‘Notes’ was a bit awkward in an airplane seat. (I suspect that son James would say that I should have been dictating them for some routine to transcribe them, but I am not sure my voice would have been picked up well, what with the noise of the engine.) In any event, I had had enough after processing several chapters, and I shall have to finish the task later. A long wait for baggage at Charlotte, but I allowed plenty of time for my connecting flight to Wilmington, where a car picked me up to take me home, and to a joyful re-union with Julia and Sylvia.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Cambridge Five and the Whitgift Connection

Who wrote the following sentence:

“Not for me the clandestine delights of supposedly chance encounters on that well-worn Regent’s Park bench with some charismatic unfrocked Hungarian priest coyly sounding me out for membership of the Whitgift Twelve”?

Was it Marshal of the Royal Air Force, Arthur Tedder (Whitgift, 1902-1909), Baron Tedder, Deputy Supreme Commander at SHAEF under General Eisenhower, who faced up to Stalin in Moscow and signed the German instrument of surrender?

Was it Kenneth Diplock (1917-1926), Baron Diplock, Secretary to the Security Executive in 1940, squadron-leader in the RAF, and High Court judge, who from 1971 chaired the Security Commission that reviewed the FLUENCY investigations?

Was it Burke Trend (1924-1932), Baron Trend, Cabinet Secretary from 1963 to 1973, who carried out a yearlong investigation into the claims of infiltration of Britain’s secret services by the Soviets?

Was it Geoffrey Elliott (1948-1954), son of an SOE and MI6 agent, who learned Russian during his national service, became an MI6 officer with a cover of working for Reuter’s, and was an honorary Fellow of St Antony’s College?

Was it Sir Dick White (master at the school 1933-1935), the only man to head both MI5 and MI6, who had a very checkered career dealing with the threats of Soviet espionage since he was recruited by MI5 in 1935?

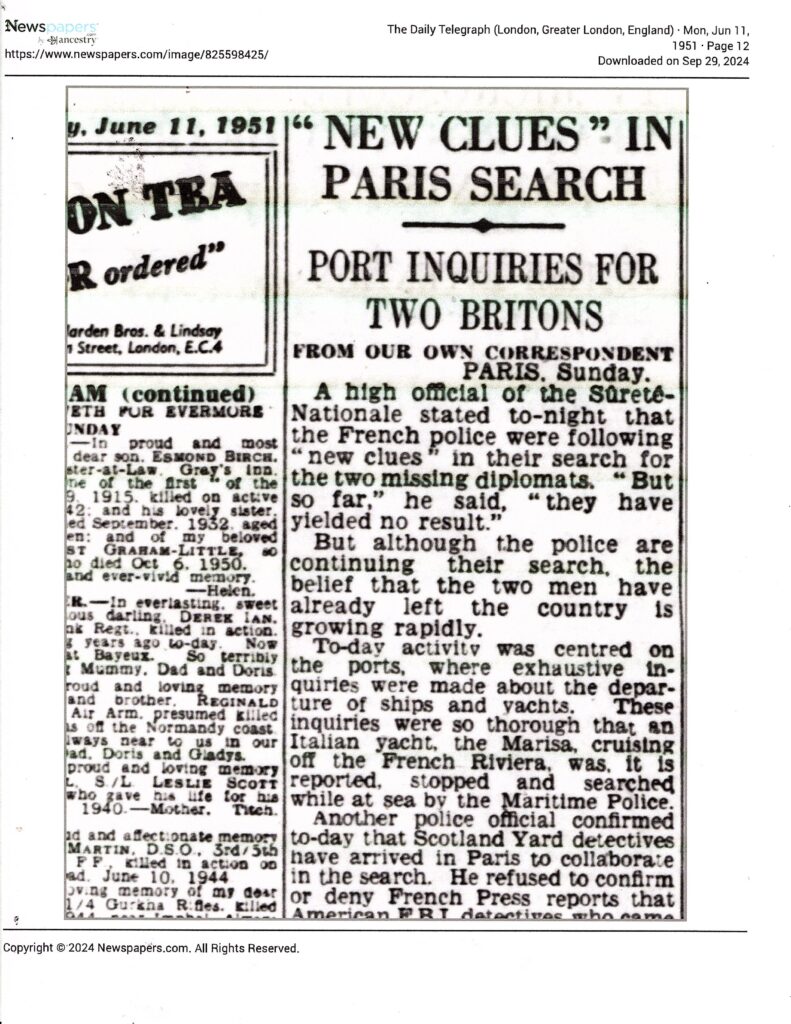

I shall return to that question later, but all five had some dealings with the infiltration of government service by moles who had been recruited by the Comintern (Stalin’s organization for promoting communism abroad) in the 1930s. The most notorious of the group known as the ‘Cambridge Five’ was Kim Philby. Before he absconded to the Soviet Union in 1963, however, a pair had captured the imagination of the British public as ‘The Missing Diplomats’ after their own escape to Russia in 1951 under suspicious circumstances. Their names were Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean.

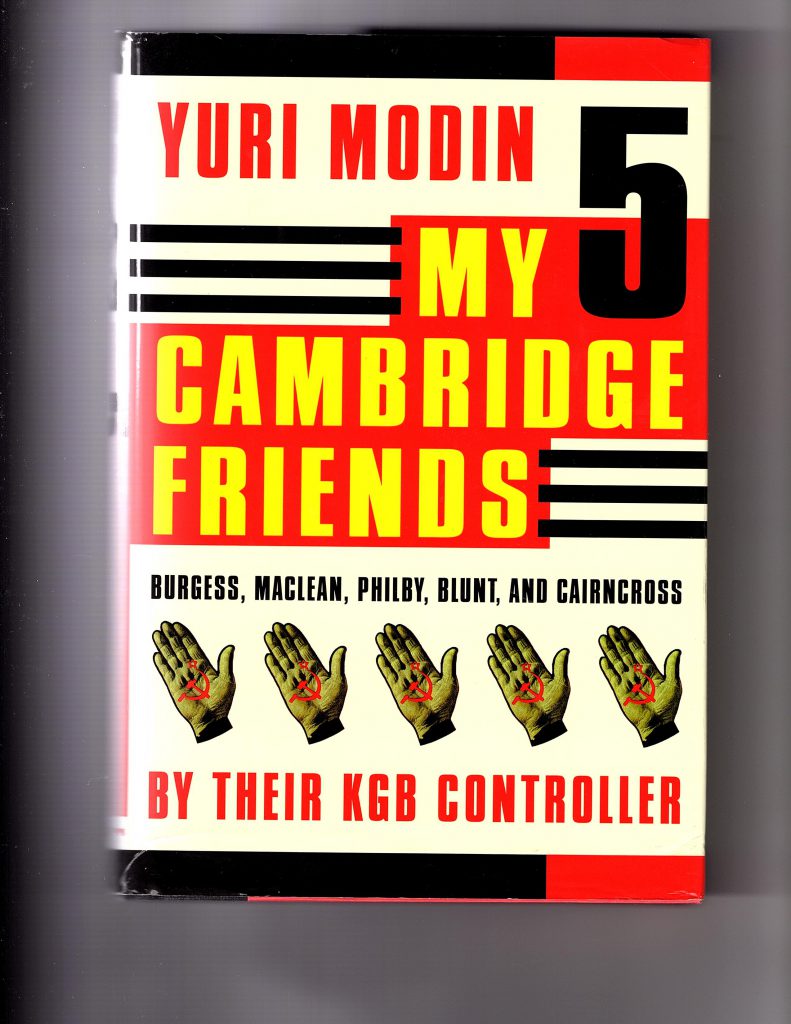

‘Burgess and Maclean’ was thus, in the 1950s and 1960s, a familiar dyad, like ‘Marks and Spencer’, or, perhaps more suitable for today’s audience, ‘Ant and Dec’. The fourth member of the group was the art historian Anthony Blunt, who managed to secure a plea bargain with MI5 in 1963, whereby he was given immunity from prosecution in exchange for telling the authorities ‘all he knew’ about Soviet espionage in Britain. He was unmasked, to great embarrassment, in 1979, after Andrew Boyle’s Climate of Treason was published. The fifth member, John Cairncross, was less closely affiliated with his four companions, but did as much damage to Britain’s interests as any of the group.

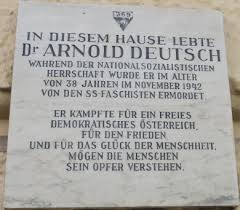

What is remarkable is the subterfuge that the group engaged in, and how they managed to manipulate the trusting counter-espionage officers and bosses of MI5 and MI6. To understand properly the manner in which they infiltrated the corridors of power, the Foreign Office, the Treasury, GCCS (the forerunner to GCHQ), MI5 and MI6, we have to go back many years, first to that period just before WWII, when allegiances were being build and dismantled in the face of Nazi aggression in Central Europe, and then, further back, to 1934, when Philby was recruited in Vienna to work for the NKVD.

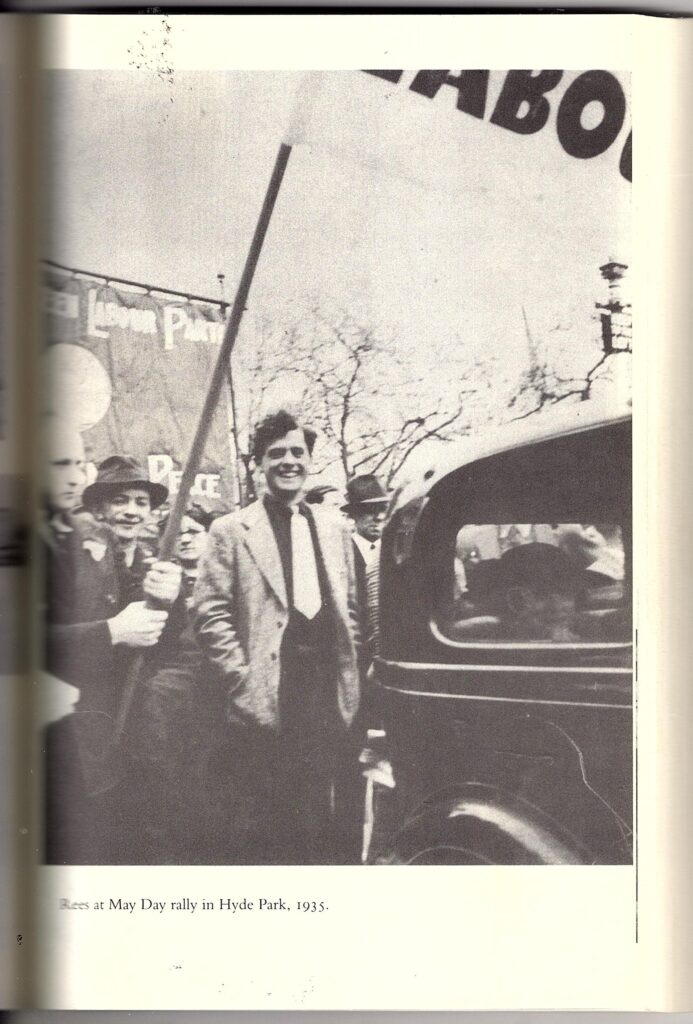

The lure of communism was largely because the Soviet Union was viewed by many intellectuals as the only force strong enough to resist, or even demolish, fascism, as Hitler’s oppressions and his territorial ambitions became more evident after he assumed power in 1933. The Cambridge Five were all recruited by the Comintern (effectively the NKVD) in the mid-thirties. Thus, when Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia announced a non-aggression pact in August 1939, members of communist parties around Europe – as well as those clandestine believers who had steered well away from the communist party itself – were shocked that such a partnership with the devil could have been sealed. Philby, Blunt, Burgess and Maclean were in that number. Burgess and Blunt heard the news while they were travelling in France, and struggled to come to terms with the announcement, eventually concluding that they had to stay loyal, believing in the wisdom of Stalin, and that he was buying time.

Kim Philby was in a more delicate position. He had committed to the Soviet cause ever since he helped victims of official persecution in Vienna in 1934, whither he had been guided by his mentor at Cambridge, Maurice Dobb. He had acted as a courier, taking messages across the border to Prague by virtue of his British passport. He had also engaged in propagation of leftist ideas, and married a woman who was an even more dedicated communist, Litzi Friedmann. That partnership was one of the most bewildering aspects of his career since, if he had wanted to pursue a life of subterfuge in penetrating British government circles, he should not have allowed attention to be drawn to his affiliations with known communists. The fact that MI6 seemed to be aware of his activities, and even subtly condoned them, has always been one of the most enigmatic aspects of the Philby puzzle.

After he (with Litzi) returned to Great Britain in May 1934 (you cannot trust Philby’s memoir concerning the facts of his journey, or subsequent goings-on), Philby was apparently officially recruited as a Soviet agent. (That is where the anecdote about a meeting on a bench in Regent’s Park derives.) He was responsible for identifying possible new recruits, among them Burgess and Maclean, with Blunt as an adherent soon afterwards. As cover, he then gradually distanced himself from any leftist associations, and even joined the Anglo-German Friendship Society. He worked as an independent journalist in the Spanish Civil War, and then was hired by the Times to report from the Nationalist (i.e. Nazi-sympathetic) Franco camp. He was biding his time, waiting to make his entry into some department of Britain’s intelligence services. Yet the announcement of the pact had potentially far direr implications for him.

The problem was that a senior NKVD officer named Walter Krivitsky (not his real name) knew about the mission by a young English journalist to be sent to Spain, ostensibly to assassinate Franco. In 1938, Krivitsky, greatly alarmed by Stalin’s purges of the Red Army as well as of members of the foreign intelligence organization, decided to defect instead of being recalled to Moscow to face certain death. He left France for the USA, co-operated with American intelligence, and had his memoirs ghost-written, thus incurring Stalin’s wrath more intensely. One of the insights he imparted was the identity of a spy in the British Foreign Office, which resulted in the arrest of John King. MI5 was intrigued enough to want to invite Krivitsky to Britain, and he was interviewed at length in January 1940. One of the officers who met him was Dick White, who was not very impressed with him.

The lead MI5 officer on the case was Jane Sissmore, who had recently married another MI5 officer, John Archer. She was the most experienced Soviet counter-espionage officer, and, with the help of Stephen Alley, an old Russia-hand, she interrogated Krivitsky at length, and then produced a comprehensive report on Krivitsky’s testimony. Several beguiling clues emerged, including a slightly erroneous pointer to an ‘Imperial Council spy’ in the Foreign Office, who was in fact Donald Maclean, and a much clearer indication of a young journalist who had travelled to Spain on behalf of a newspaper. One might have imagined that at least one of these clues would have been pursued, and the identity of Philby unmasked.

Yet very little happened. There seemed to be no eagerness to pursue the leads. What is more, Jane Archer was removed shortly afterwards from MI5 counter-espionage, and took over a role in managing a group called the Regional Security Liaison Officers before being fired from MI5, later in 1940, for apparent insubordination. The reason given was that she had made inappropriate and disrespectful remarks about the acting MI5 chief, Jasper Harker. She was moved to MI6, where she incidentally became a threat to Philby himself. No one has satisfactorily explained why MI5 behaved so indolently after capturing so much vital information about Soviet penetration.

My theory is that Philby learned, early in September 1939, of the coming visit by Krivitsky, and realized that he could be quickly unmasked by the amount of information that the defector knew about him. A bold counter-attack was required. He thus approached MI5 and told them that, yes, he had been a Communist sympathizer, and had performed routine work for the NKVD, but that the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact (as it was known) had made the scales fall from his eyes. Stalin was obviously a traitor to the cause, and Philby would throw in his lot completely with Britain’s declaration of war against Hitler. He probably brought his associates (certainly Burgess and Blunt) into his scheme, and set about crafting a career, initially with SOE, and then with MI6. The authorities believed his story, while accepting that Philby would have had to conceal his change of heart from his Soviet masters. MI5 and MI6 now had an agent in their camp who could deliver the occasional nuggets of disinformation to the Soviets.

Another outcome of this soul-cleansing was that Blunt was recruited by MI5. MI5 was in some disarray in the first half of 1940, what with a clumsy management organisation, and an enormous challenge of sifting out unreliable elements from the mass of refugees arriving on Britain’s shores. Winston Churchill fired its chief, Vernon Kell, and instituted a Security Executive (the unit that Kenneth Diplock helped to administer) to oversee all the country’s intelligence efforts. It did not last long: Blunt had been taken off an intelligence course as a recognized communist, but his pal Victor Rothschild managed to bypass the security checks and get Blunt in, initially as the assistant to Guy Liddell, the head of B Division, responsible for counter-espionage. The rot was setting in.

By this time, Maclean had been firmly established in the Foreign Office. He had been posted to Paris, where after having an affair with his Soviet handler, he had married Melinda Marling, an American, just before the Germans arrived, and the couple made a hasty escape to England in June 1940. Melinda knew about his espionage for the Soviets, and her ability to deceive the British authorities later constituted another facet of manipulation. Burgess was in his own league: his disreputable behaviour resulted in his being fired by SOE, and he thereafter drifted around during the war, working for the BBC, the Ministry of Information, and as an ‘agent’ of MI5, with his cover of being far too obvious in his anti-American and pro-Soviet diatribes to be considered to be capable of acting as an agent for anybody.

It should be remembered that, from September 1939 to June 1941, when Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in Operation BARBAROSSA, Stalin was aiding the German war effort against Britain and the Empire. The Soviet Union was not a technical enemy, but it was a hostile entity, and considerations of Soviet espionage, where confidential information could have been shared with Nazi Germany, should have been alerted. That MI5 was confused during this period was one of the assertions I made in Misdefending the Realm. All that changed, however, when BARBAROSSA was launched, and Churchill issued his over-enthusiastic pledge to assist his new ally. Thereafter, as the case of Klaus Fuchs made clear, the deficiencies and dangers of communists in their midst were forgotten as government officials showed their willingness to endorse and nourish anyone who could help in the battle against Hitler and Nazism. In that way the ‘Tube Alloys’ project, to build atomic weaponry, was fatefully undermined.

MI5’s counter-espionage energies for the remainder of the war were thus focused almost exclusively on the Nazi threat, with some sporadic attention spent on the Communist Party Headquarters. This did result in the arrest and sentencing of David Springhall in 1943, but the worst offenses were taking place away from Party members. Moreover, MI5 and MI6 were mismanaging the threat of subversives in their midst. For example, MI5’s indulgence towards Ursula Beurton (Agent Sonya) showed that the intelligence services believed that she was actually under their control. Meanwhile, the Cambridge Five did their best to pass secrets on to their Soviet masters. In fact the information was so prolific that for a while, in 1943, the NKVD suspected that it was being fed disinformation by agents under British control.

One of the most damaging phenomena was the deployment of ULTRA intelligence – that deriving from interception and decryption of German wireless traffic – primarily from the ENIGMA machine. Churchill was adamant that the source be disguised, lest the project be revealed to the Germans, and he had information packaged up for the Soviets in a way that would conceal its source, either physical or textual. The Cambridge Five (especially Blunt and Philby) were frustrated that Britain’s Eastern ally was not receiving all that she needed – although the pair was in ignorance of exactly what was being sent, probably through the Red Three ring in Switzerland. Thus Stalin received from his spies richer information concerning German battle plans than he was receiving officially, which inevitably led to distrust and suspicion on the part of the vozhd. In addition to that, his unrealistic demands for the opening of a ‘Second Front’ (regardless of the fact that Britain and the USA were operating on multiple international fronts) were echoed and enhanced by his agents and sympathizers in the Ministry of Information in Britain.

The wily Stalin manipulated Roosevelt and Churchill. As for those who worked under them, he had mixed views. He had no time for prigs like ambassador Stafford Cripps, and preferred an earthy character like Cripps’s replacement Clark Kerr, with whom he could share dirty jokes. He regarded with disdain obsequious and patronising politicians like Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, preferring blunt military men who got down to business. Thus he got on well with Tedder, who was sent on a mission to Moscow in early 1945 to coordinate the final phases of the war, and request more pressure from the Soviet Union as the incursions into Germany had been stalled. The exchanges were regarded as the most successful of the various dialogues that western leaders had with Stalin.

1945 was a critical year for the fortunes of the Cambridge Five, however, mainly affecting Kim Philby. It was marked by two attempts at defection by Soviet intelligence personnel – one successful, the other fatally disrupted. When a cypher-clerk, Igor Gouzenko, escaped to the Canadian authorities in August 1945, he was able to provide information that led to the arrest and conviction of Alan Nunn May, an atomic spy, and the identification of many Canadian informers. He also offered vague hints to the identity of a spy code-named ‘ELLI’, which set MI5 guessing for years. The following month, Konstantin Volkov in Istanbul volunteered his services to the UK embassy, promising to name a nest of spies in British intelligence, but the officer sent out to investigate him was Philby himself. By the time he arrived a few weeks later, Volkov and his wife had been exfiltrated to Moscow, and killed.

The Volkov incident was just one of several where doubts were being cast about Philby’s loyalty. In 1946, his private life came under the microscope. Belatedly thinking that he ought to divorce Litzi Friedman so that he could make an honest woman of Aileen Furse, he went to his boss to come clean, and met a very indulgent response. According to the flimsy accounts that were told afterwards, he managed to gain a quickie divorce from Litzy, and then marry Aileen in September 1946. Yet, by then, Litzi had absconded with her lover Georg Honigmann to Soviet-controlled Germany, Honigmann himself done a bunk from an educational position with the Control Commission. How Philby contacted Litzi, how she managed to leave East Berlin, where they in fact got divorced, and under what circumstances, is a mystery. Litzi was very coy about her marital status in oral statements to her daughter who was born out of the Litzy-Georg relationship.

A symptom of questions about Philby’s loyalty was his removal from the position of head of MI6’s Counter-Espionage section in 1947, soon after he had been appointed, and his transfer to Turkey. Istanbul was, however, an important post, the centre of MI6’s intelligence operations against the Soviet Union. The late 1940s are a very murky period in the matter of MI6’s trying to turn back the tide of Communist domination of Eastern Europe. Tedder, as a member of the Russia Committee that strategized over how to prepare for the Communist threat, was disdainful of armed subversive encroachments into Soviet satellite territories that were not backed up by full military force, and argued against the revival of SOE-type exploits.

Despite Tedder’s warnings, some clumsy forays were being made behind the Iron Curtain, of which the disastrous Albanian venture (partially betrayed by Philby) was the most prominent. And MI6 continued with more conventional enterprises – using agents who were already known to Soviet intelligence. One of these ventures employed Geoffrey Elliott’s father, Kavan, who had been used as an SOE agent in Yugoslavia during the war, but had been immediately captured. In 1948 he was working for MI6 with commercial cover as a Unilever manager in Hungary, but arrested as a suspected spy. He was probably working as a liaison between the Vatican and Cardinal Mindszenty: he was eventually released under questionable circumstances. Geoffrey Elliott claimed that Philby had betrayed at least one other MI6 asset, a Hungarian national, who had been his father’s contact, and was executed. Dick Brooman-White (a former MI5 officer, who preceded Philby as Head of Station, and had been an exact contemporary of Philby’s at Trinity College, Cambridge) may have unwittingly passed on information to Kim that seriously damaged the network in Budapest. The fact that Gabor Peter, who led Hungary’s intelligence service, had been a lover of Litzi Friedmann’s before she met Kim, is a tantalizing detail that may point to hidden connections.

During the late 1940s, disputes over threats of deploying nuclear weaponry as a means of defence against the Soviet Union took place between the Foreign Office and the more aggressive Chiefs of Staff represented on the Russia Committee. Tedder, who had very solid relations with the Americans, and for whom Dick White had worked in as counter-intelligence expert at the end of the war, expressed the view that the Cold War should be won by the overthrow of Stalin’s Empire within five years. That ambition was based on the assumption that the Soviet Union would not have an atomic bomb at their disposal until the mid-fifties. Illusions were shattered when Stalin’s scientists, greatly aided by Fuchs and company, detonated a bomb in August of 1949.

According to Stephen Hamrick’s very speculative Deceiving the Deceivers, Tedder was very supportive of a plan to resuscitate the London Controlling Section that had manipulated the Double Cross operation of World War 2, in an attempt to plant disinformation on the Soviets. There is no doubt that this initiative was real: the Committee that supervised it was called the Hollis Committee, after General Leslie Hollis, who was secretary to the Chiefs of Staff. We know from Guy Liddell’s diaries that Burgess and Blunt were involved in such a scheme: Hamrick makes the apparently outrageous claim that Philby, ‘as a known Soviet agent’, was also used, alongside Maclean, to carry on such a propaganda campaign. How they could be trusted not to tell their true masters all is not explained by Hamrick, but if there is any merit in the story, it highlights possible tensions in 1948 between Tedder (who may have persuaded that Philby was a loyal agent in touch with the Russians) and White, who had by then concluded that Maclean and Philby were both traitors.

And then the VENONA program created a whole new bouleversement. VENONA was a decryption project carried out by the USA’s NSA (National Security Agency) and Britain’s newly formed GCHQ. The Soviet Union’s slackness in re-using ‘one-time pads’ during the war meant that a large raft of wartime messages, which had been intercepted and stored, laid themselves open to analysis. Fragments of messages trickled out during the late 1940s, with one particular thread being the actions of one ‘GOMER’ (= HOMER), who had betrayed Allied military plans at the end of the war to his Soviet masters. By 1949, Dick White (now head of counter-espionage in MI5) had latched on to the fact that HOMER was probably Maclean. At that stage, he surely concluded that he had been taken in by Philby and his wiles, and that the NKVD had planted cuckoos in his nest. If such a truth came out, it would be highly embarrassing for MI5 and the UK government, and White even tried to quash the investigation. But it had too much momentum by then.

In the interim, some extraordinary employment transfers had been made. Guy Burgess had joined the Foreign Office after the war, as a Press Officer, and after working as Personal Assistant for Hector McNeil, was transferred to the Junior Branch of the Foreign Office. He had, however, engaged in reckless and abusive behaviour in Gibraltar. Maclean, who in 1948 had been transferred from Washington to Egypt, no doubt under the strain of fearing that he was likely to be unmasked by VENONA, also engaged in destructive acts under the influence of alcohol. Both should have been dismissed, but Burgess was given a warning, and Maclean was recalled for psychiatric treatment. Yet Burgess was then transferred to Washington, and Maclean was appointed head of the American desk at the Foreign Office in the autumn of 1950. Kim Philby had been sent out to Washington in 1949 to act as the liaison between MI6 and the CIA/FBI, and he thus had access to the progress of the VENONA project. By the end of 1950, Dick White had an eye on them all, suspecting that each was guilty of espionage to some degree.

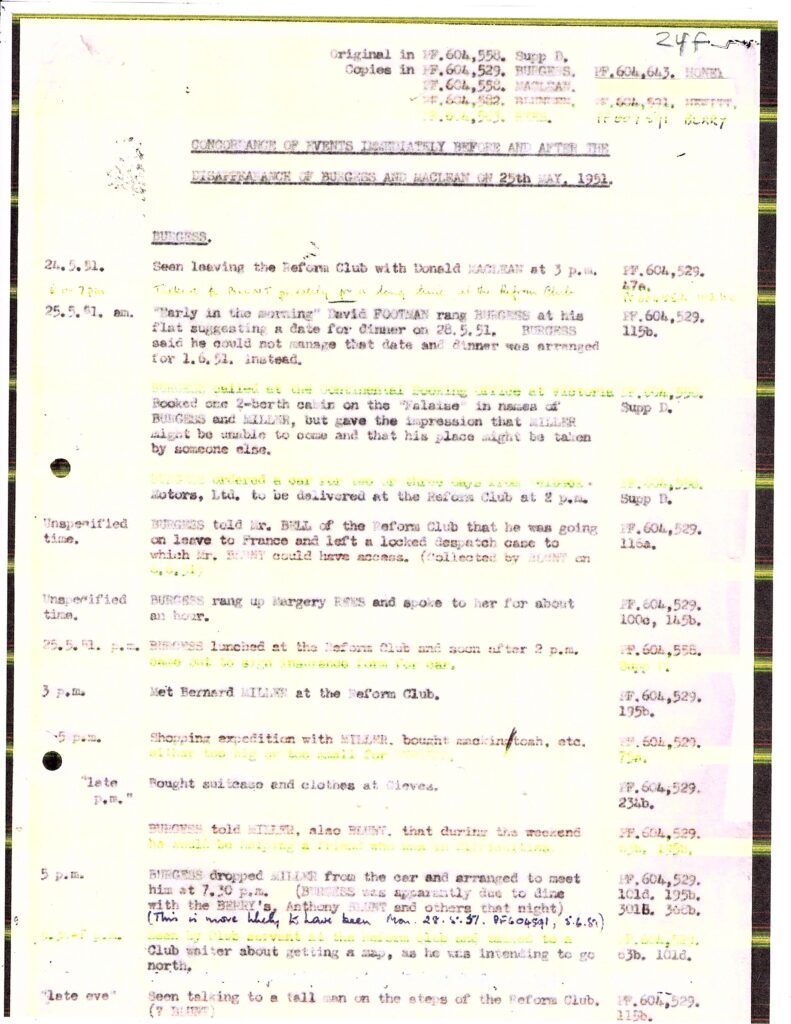

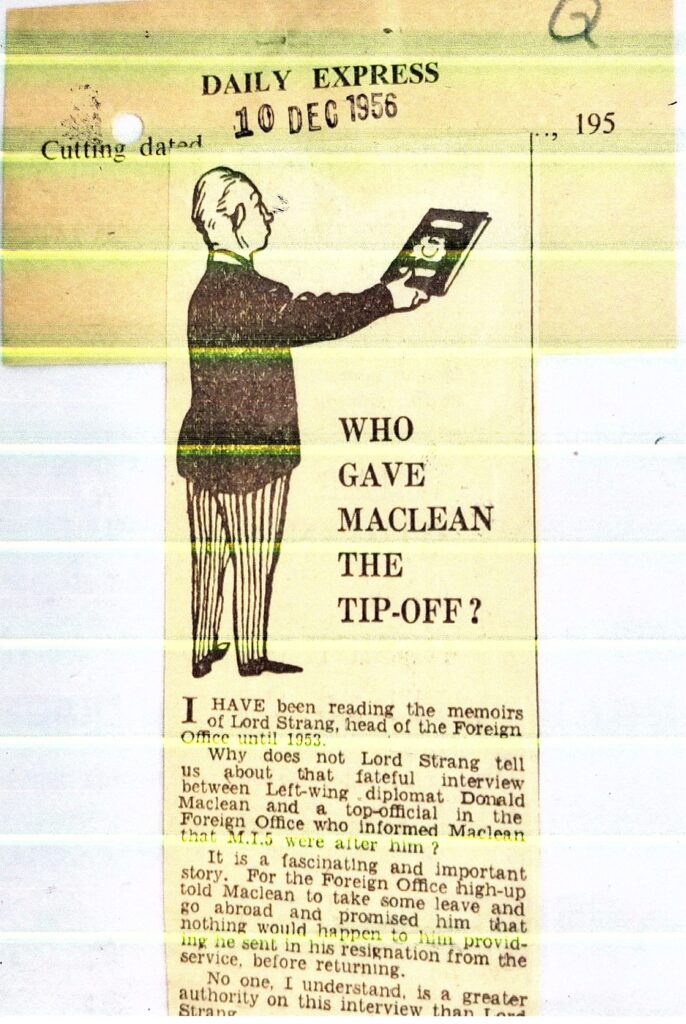

As the evidence from VENONA pointed more unerringly towards Maclean, White faced a challenge. He led a close cabal of Foreign Office careerists that was tracking the project, and deciding at what stage Maclean should be called in for questioning. At the beginning of May 1951, however, Burgess was recalled to London because of poor performance. White’s plan to entrap him with Philby had not worked. Burgess by happenstance was able to act as a useful messenger between Maclean and Blunt, who, having been advised of the crisis by his Soviet controller, was helping to make arrangements for Maclean’s escape. At the same time, White daringly prepared a dossier, to be carried by his sidekick Arthur Martin to Washington for the CIA, which explicitly incriminated Philby as an agent of the Russians. White also realized that the last thing MI5 and the Foreign Office needed was an awkward confession by Maclean, and an embarrassing trial. So he schemed with Blunt (who in his opinion was still a loyal ally) to arrange for Maclean and Burgess to escape from the country on May 25.

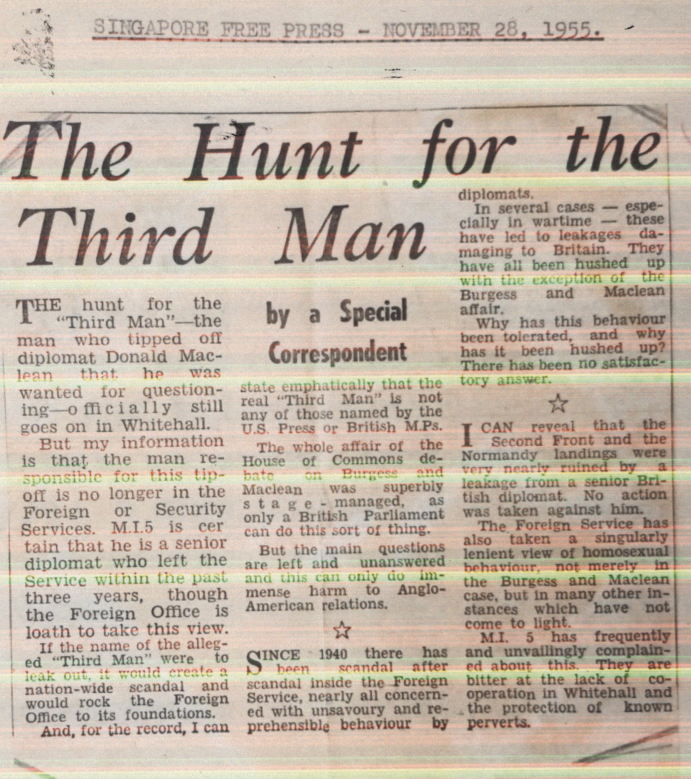

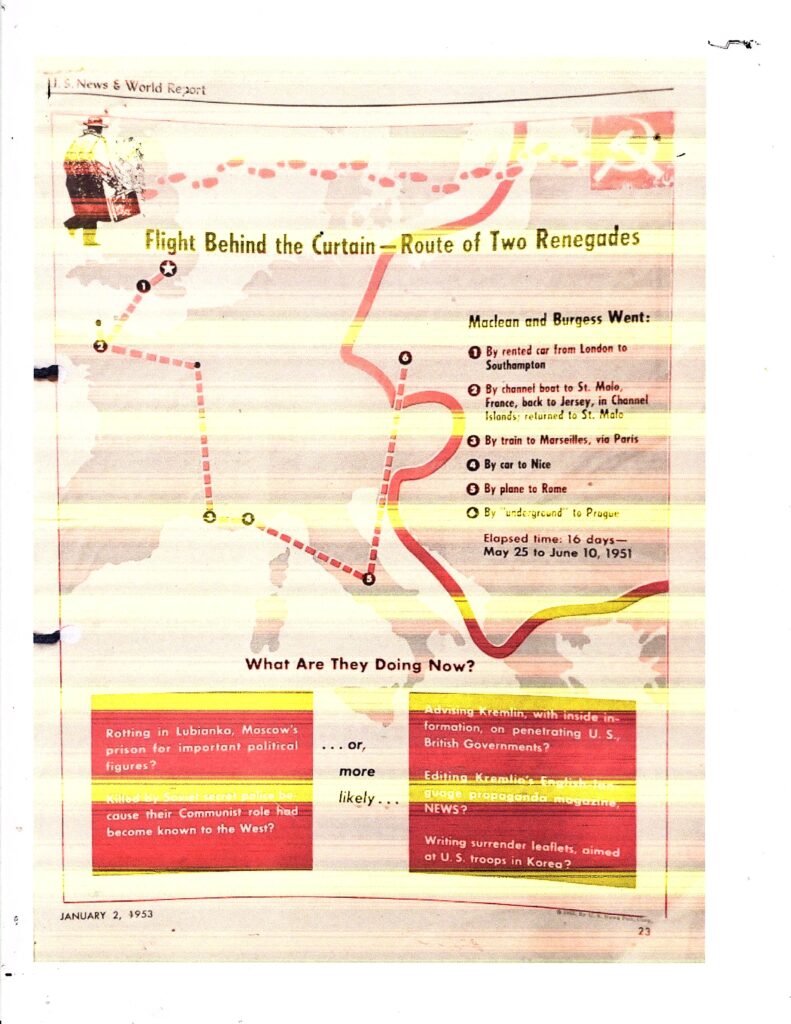

The story that has dominated the accounts of the escape of Burgess and Maclean has been that a ‘Third Man’ managed to give the pair the tip-off, and that they thus absconded just before Maclean was to be brought in for interrogation. Through a clumsy exercise later, when they were forced into the open, White and the Foreign Office claimed that Philby had been that individual. Yet that theory was nonsense. Philby was thousands of miles away at the time, and unable to influence events (although he had earlier alerted his Soviet handler in the USA about the HOMER hunt). Moreover, Maclean was not about to be brought in for questioning. The decision had been made that the move should not be made until after Melinda’s delivery of their third child, in a few weeks’ time. In any event, Burgess and Maclean escaped under the noses of the surveillance teams and Special Branch, and MI5 and the Foreign Office pretended they had no idea why the ‘Missing Diplomats’ had disappeared, nor where they had gone. For a while, despite some irritating rumours in the Press, they got away with it.

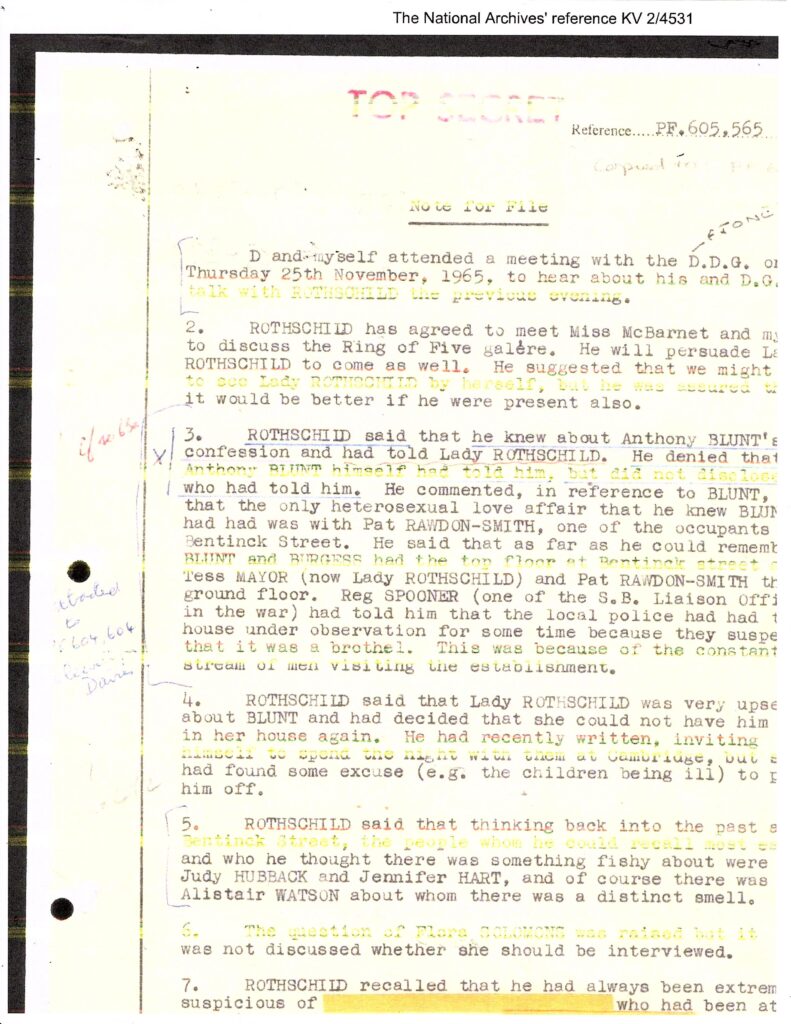

Immediately after the escape, Dick White’s suspicions fell upon Blunt, and he and J. D. Robertson even considered offering him immunity if he would confess all. White was also involved with Philby, who had been recalled before White’s dossier could be processed by the CIA, and who had evidently decided to brazen it out rather than defect himself. Neither White’s incompetent interrogation, nor a hastily arranged one by QC Helenus Milmo, could persuade Philby to confess to anything, but he was forced to resign from MI6. MI5 and the Foreign Office then fumbled around, evading questions, until the defection of the Soviet agents Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov in Australia in early 1954 sent an embarrassing salvo across the British bows. The Petrovs had learned through colleagues of the method of escape of Burgess and Maclean (which then became public), and of the existence of a wartime spy in MI5 who had passed on secrets. After some frenzied questions by the Press, and the resuscitation of the ‘Third Man’ rumours, White, who had unmasked Philby to his American counterparts, was forced, in October 1955, to prepare a statement for Prime Minister MacMillan that Philby was innocent.

Meanwhile, Philby still had his allies within and without MI6 (one of his staunchest being Brooman-White, now an MP), and they tried to resurrect his career. Such plans were derailed when Dick White, who had been appointed director-general of MI5 on Sillitoe’s retirement in 1953, was transferred to head MI6 after the Commander Crabb ‘frogman’ disaster in 1956. White was seen as a ‘safe pair of hands’, and with his strong belief that Philby had throughout remained loyal to the Soviet cause, was not having him around. Philby moved to Beirut as a journalist, but in 1961 the Soviet defector Golitsyn provided strong evidence of Philby’s guilt. White, recalling the ploys of Burgess and Maclean, clandestinely sent Blunt out to the Lebanon to warn him, so that he could likewise abscond, and thus not cause excessive embarrassment to White and the intelligence services through a confession and trial. Thus, when Philby’s crony Nicholas Elliott went out to confront Philby in January 1963, a staged confession was set up, and Philby decamped to Moscow.

Guy Burgess died in June of that year, which was marked by another dramatic event – the admission to the FBI by Michael Straight that he had been a Soviet agent recruited by Anthony Blunt. The official story of what happened next cannot be trusted, and careful inspection of the evidence shows that in December 1963 (not April 1964) Blunt was persuaded to ‘confess’ by means of an immunity offer, by which he promised to inform MI5 of all he knew about Soviet espionage. It had taken twelve years for the suspicions and desires of Dick White to deliver Blunt to his interrogators: the inquisition into Blunt was feeble, and may have been engineered in that way by White, so that the skeletons would remain locked in the cupboard. But even then, in 1964, it was a false dawn. Blunt evaded the difficult questions, and his inquisitors had no idea how accurate the information was that Blunt told them, or how they should address the phenomenon of his selective amnesia.

Yet the saga was not over. Golitsyn became carried away, and convinced his friend James Angleton in the CIA that British Intelligence was riddled with further spies: their enthusiasm infected Arthur Martin and Peter Wright in MI5. A series of investigations was carried out, in which Graham Mitchell and Roger Hollis (White’s replacement as Director-General) came under severe scrutiny. Dick White, from his fastness in MI6, played a dishonourable role in all of this. In an effort to distract attention from his own undistinguished activity in allowing Soviet penetration of MI5, he encouraged speculation about his former colleagues and friends – especially when they were dead, and could not defend themselves. Thus he was happy to cast aspersions on Guy Liddell, and how he might have abetted the escape of Burgess and Maclean. He encouraged the investigations into Mitchell and Hollis, knowing that they would be fruitless, but that, if the quest remained inconclusive, the opinion of the press and the public would tend to hold Soviet penetration responsible for all the errors rather than institutional incompetence.