“Oh, what a tangled web we weave.

When first we practise to deceive!” (Sir Walter Scott, Marmion)

In this bulletin, I use some correspondence as a trigger to invoke a more detailed analysis of Dick White’s plot to leak information on Kim Philby to the CIA – the exercise that his representative in Washington characterized as an ‘ingenious scheme’ – and to re-assess White’s overall track-record as a counter-espionage officer.

Contents:

An Uncomfortable Exchange

The Letter from Mr. Even-Shoshan

Re-Assessing Dick White’s Plot

Milicent Bagot’s Dossier

The Strange Reactions of Robert Lamphere

Deeper Implications

White’s Predicament

PEACH

Enter ‘Buster’ Milmo

‘The Imperfect English Counter-Espionage Officer’

Postscript: The Lost Philby Chapters

* * * * * * * * * * * *

An Uncomfortable Exchange

I often reflect on the various email exchanges I have with two groups of individuals. The first I shall call ‘members of the public’, namely amateur enthusiasts for intelligence matters, former intelligence officers, journalists, and writers of histories and biographies with no relevant academic qualifications. The second is simply ‘academics’, professional historians with doctorates or professorships teaching at universities. The messages from the first group are almost uniformly engaging, showing humility, a genuine curiosity and willingness to engage in sensible discussion, patience, and an appropriate degree of scepticism, as well as a readiness to express complimentary remarks about my research. The academics, on the other hand (if they respond at all, of course) are generally – but not always – abrupt, dogmatic, patronising, intemperate, and stingy with any praise.

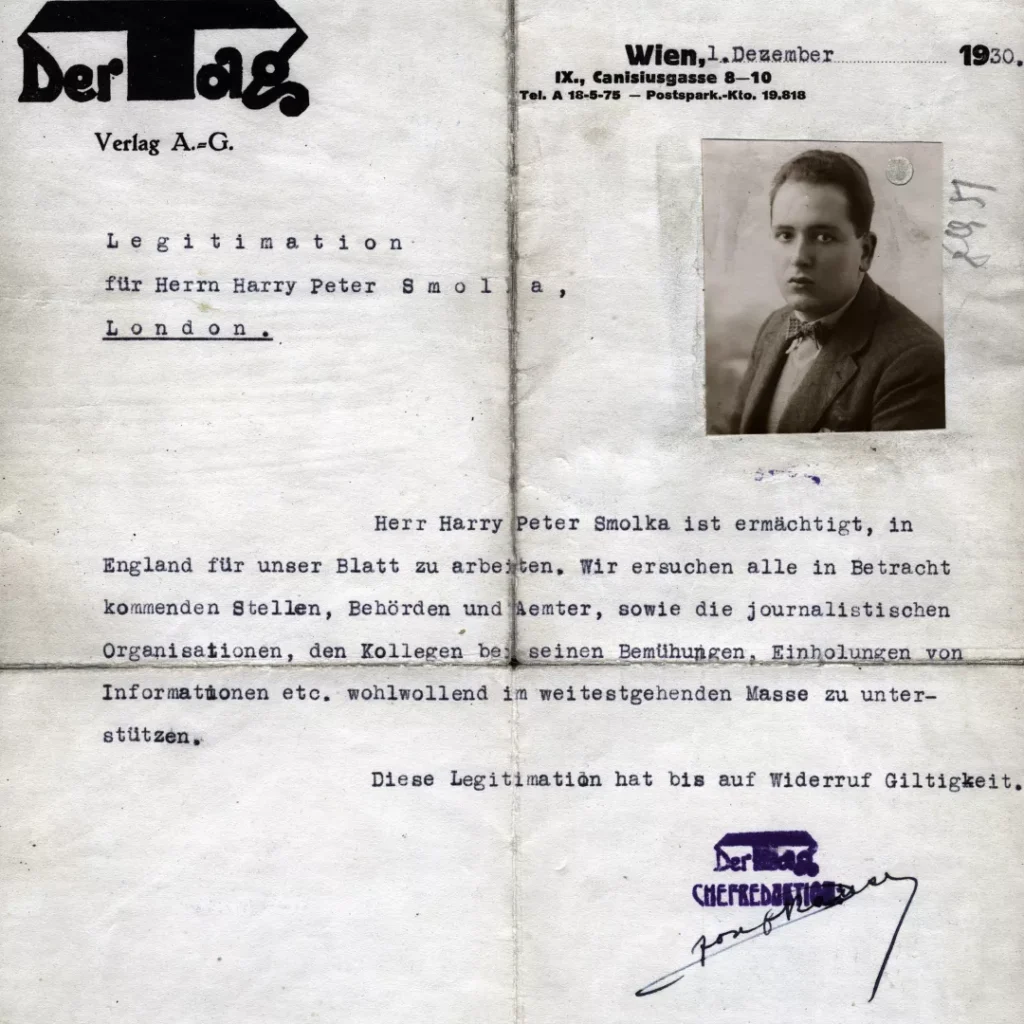

I was reminded of this contrast during two recent conversations I had with persons I have never met. The first was a female academic (whom I shall not name – unless there is an overwhelming demand for her identification from coldspur readers) whom I had approached concerning Kim Philby. She responded quite pleasantly to start with, and I sent her a late draft of my February coldspur article on Smolka. Her immediate response was ‘Yes, I know the whole Smolka story’, and she described a recent project concerning him that she had worked on. This was a clear message to me that she was the undisputed expert on Smolka, and that she had nothing to learn from any other source. (I do dislike know-alls.)

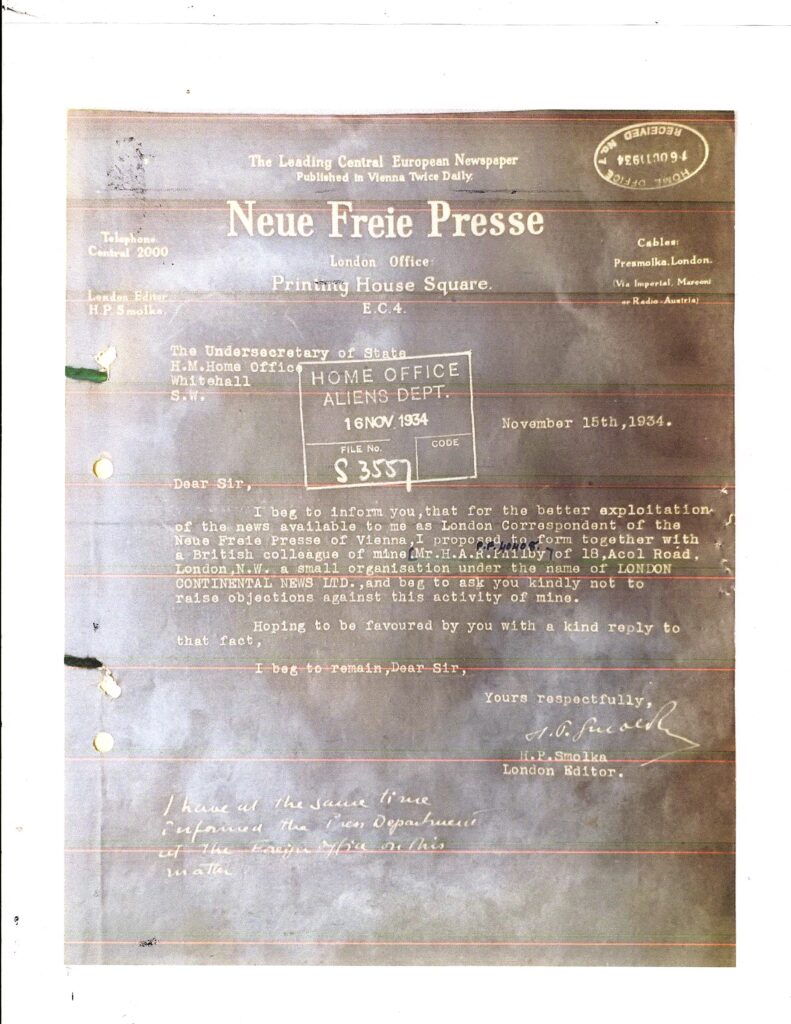

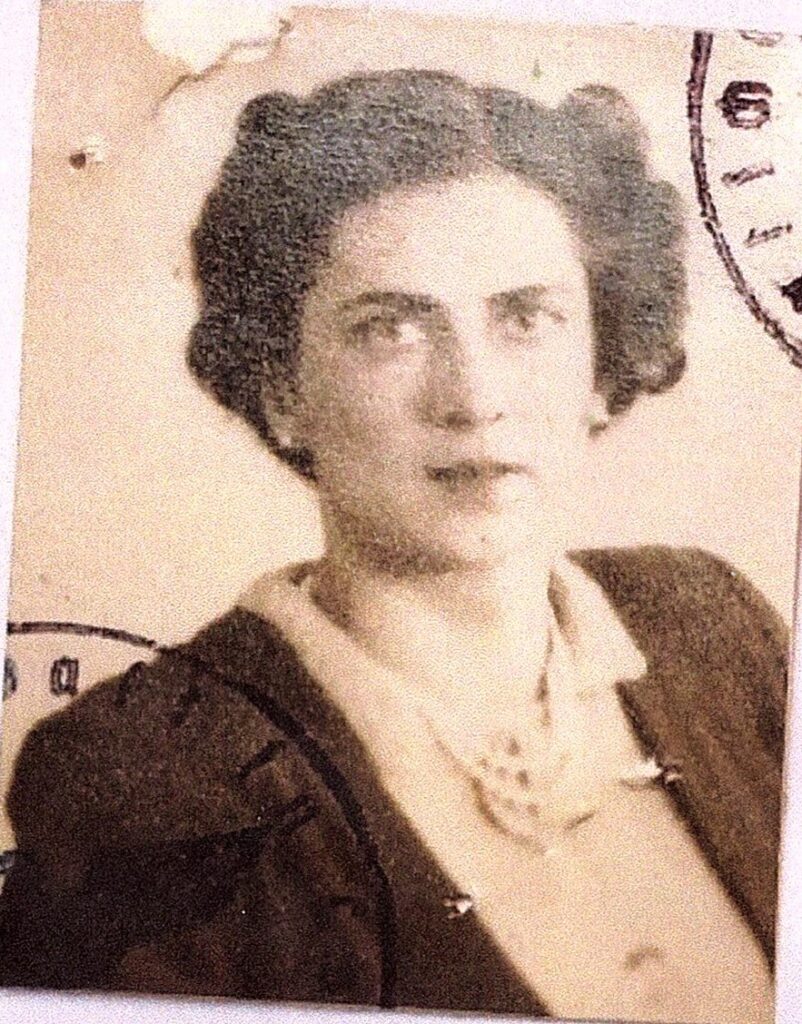

And then, when I suggested that Edith Tudor-Hart’s role had been greatly exaggerated by such persons as Anthony Blunt (as well as the KGB), she immediately accused me of having male chauvinist tendencies, telling me that I underestimated the work of female intelligence officers. This was an extraordinarily illogical – and faintly insulting – conclusion to come to, and I responded that I was a big fan of Jane Sissmore/Archer, and that I recognized what Daphne Park had achieved. I also mentioned that I had recently read Helen Fry’s Women in Intelligence, and learned much from it. She ignored my response, and then questioned me about the planting of the 1934 press article about Philby, which I had ascribed to MI6, and lectured me that Philby had had nothing to do with MI6 at that time.

It was quite obvious that she had not read the piece I sent her (nor was she familiar with Fry’s book), so I gently drew her attention to it again, asking her whether she had already encountered everything that I had uncovered about Smolka. She quickly wrote back a hot-headed message titled ‘Philby working for MI6 in 1933 is SO NUTS!’, and I quote the full content of her text (which lacked any salutations):

Helen Fry cannot be serious. This is the most ludicrous theory ever.

Christopher Andrew must be laughing his head off (but you will probably say he is establishment and we have to believe in conspiracies instead).

Regarding Smolka: Yes of course he was working for the Russians. That is hardly new (I did not mean you should try to read Russian books. I mean their archive releases. Go to their websites)

Korda and Greene had other things to do in Vienna in 1948 than interviewing the little fish Smolka. (Ever heard of Peter Lunn and his tunnels?)

And one did not need Smolka to learn about penicillin and sewers (yes, I know that Montagu claimed his short story was vital etc) If you read German, go through the newspaper collection ANNO. It is online. They were covering these stories all the time. It was public knowledge.

My first reaction was to wonder whether the lady harboured any inherent prejudices against all female historians, but I quickly put that unchivalrous thought behind me, and turned to the substance. It seemed to me that not only had my correspondent not read carefully anything I had written, but that she also was grabbing the wrong end of the stick with her rhetorical and ill-mannered flourishes. Specifically:

- It did not appear that she had read Helen Fry’s Spymaster, for she would otherwise acknowledge that Fry actually cites a retired MI6 source who made the claim about ‘Philby always working for MI6’, while she (Fry) cast doubts on its veracity. Moreover, Fry withdrew that assertion in the second edition of the book, a move that I ascribed to the fact that she had been ‘nobbled’ by the authorities. My correspondent shows no awareness of these events, and thus her opinion on the ludicrousness of the assertion is ill-directed and lacks any substance.

- Why the reactions (cachinnatory or otherwise) of the ‘great Yoda of intelligence studies’ [M.S. Goodman] had to be invoked was a mystery to me. After all, Andrew is the authorized historian of MI5, not MI6, and his pronouncements on these matters have been erratic. It was he who declared, almost a decade ago, that his findings on the very relevant Eric Roberts correspondence would ‘keep the conspiracy theorists busy for fourteen more years’, but he then suffered from an attack of amnesia when asked to recall the circumstances behind that observation. The woman is clearly an acolyte of Andrew: she echoes the clumsy characterization that anyone who suggests that a conspiracy may be lurking behind any event is an irredeemable (and maybe congenital) ‘conspiracy theorist’, while implying that all the reputable scholars like her and Andrew (the ‘Establishment’, presumably) exclude conspiracies from their analyses as a matter of principle.

- The lecturette on the fact that Smolka ‘of course’ (a typical donnish insertion) was working for the Russians was naive and patronising. The fact that he was a Soviet spy is incontrovertible: the issue at stake was whether he had been recruited by the NKVD in 1933 or 1934, or whether, as Philby claimed in 1980, that it was he who had done so in 1939-1940. One major point of my article was to show how absurd Philby’s claim was, and how it must have been arranged by the KGB on Smolka’s death. My correspondent declined to engage me on this matter. She expresses far too confident an opinion of the reliability of Russian archival sources (a language she does not use, incidentally).

- She continued her bossy lesson with another arrogant remark about Peter Lunn. Indeed, ma’am, I am familiar with Lunn and his project (‘Operation CONFLICT’) to eavesdrop on Soviet telephone communications in the tunnels below the French and British zones in Vienna. Only Lunn – according to Stephen Dorril – did not replace Young as station chief until 1949, and the first recognition of the telephone cable infrastructure did not occur until late 1948, almost a year after the Greene encounter with Smolka. The woman’s insinuation is that Greene and Korda would have been involved with the operation. But Korda did not accompany Greene to Vienna at that time, and, even if the project had occurred earlier, there is no earthly way that Greene, an ex-MI6 officer with no engineering background, would have been introduced to such a sensitive project. With Philby under suspicion at the time, it would have been hugely irresponsible to have exposed any aspects of CONFLICT to Greene, Philby’s old crony in Section V of MI6.

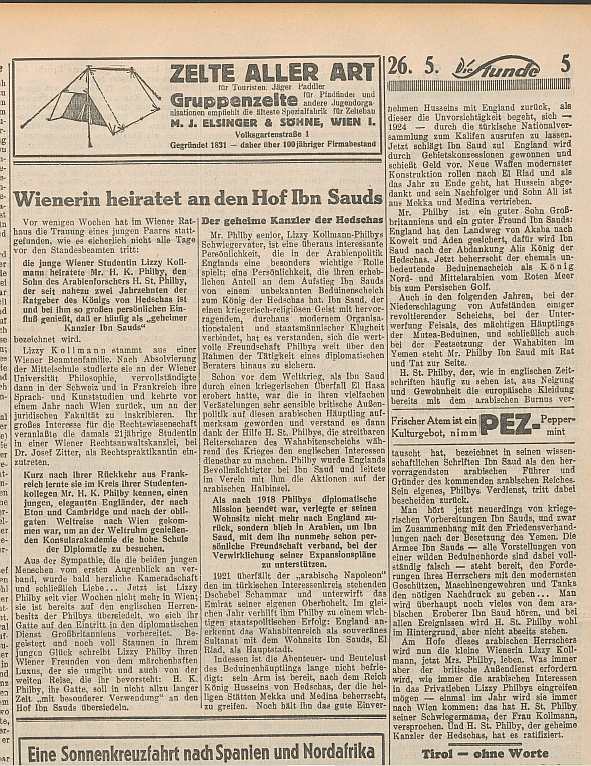

- Lastly, she fails to acknowledge that I myself had questioned the fact that Smolka had been the source of the anecdotes about adulterated penicillin and transport through the sewers, and that I had suggested that the story had been created as a useful distraction from the real reason that Greene was sent to interview him. What she means by ‘they were covering these stories all the time’, or that ‘it was public knowledge’ eludes me. That the Viennese press in 1948 was writing about fake penicillin, and that everybody knew about it? She fails to provide the evidence. It was indeed the ANNO archive that allowed me to re-present the extraordinary article about the Philby marriage in the Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung from May 1934. As for challenging my ability to read German, I actually told her that I studied the language at Oxford: she may not have encountered my translations of Honigmann yet. Yet she chooses to disbelieve me, and thinks that I used Google Translate.

You will notice that this person does not have the graciousness to say one good word about my research, or to admit that she learned anything at all from it. Her whole behaviour was clumsy, waspish, unscholarly, supercilious and offensive. It is as if she wanted to reinforce through her responses the characteristics of donnishness in all their darker aspects, and to teach this upstart a lesson. I did not respond to her outburst, but merely added her name to the List.

The Letter from Mr. Even-Shoshan

On the other hand, some conversations can be very pleasant. A week earlier, I had received an email from a fresh correspondent, one Moshe Even-Shoshan, who lives in Pennsylvania. He had just finished reading Misdefending the Realm, and, after a complimentary comment, wrote:

Yet I still struggle with the crucial question why the original approach, of the 1920s and early 1930s, to Communist/Soviet espionage changed so drastically in the critical period that you study—precisely and ironically on the background of the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact. In the last chapter, you pin the rap, to use detective novel parlance, on Dick White. But on the eve/at the beginning of WWII (for Great Britain, as opposed to the USA), he was just the first university recruit to MI5. So how could one “blame” him? After all, it was Liddell who brought Blunt in and who socialized with characters who should have not have been touched with a ten foot pole.

I look forward eagerly to your comments.

After thanking Mr. Even-Shoshan for his interest, I replied as follows:

I think your question is a very shrewd one, and it is one that has occupied me again of late, since I have started preparing a future edition of coldspur that will provide a topographical guide to my research since I published MTR.

I stand by what I wrote on p 75, as a decent account of the debacle, and how it has shifted since 1940, including Andrew’s rather shameful comments. Yet I believe that some recent research of mine – involving Philby and Smolka, the second installment on whom will appear in a couple of weeks’ time, and will reinforce the points I am about to make – sheds some further light on the passivity of MI5.

The main problem at the time was a lack of intellectual leadership in the Soviet counter-espionage business. Jane Archer was obviously outstanding, but she was a woman in a man’s world, and she fell foul of political intrigues, I suspect. Whether those intrigues were initiated by communist sympathizers, one can only guess. But she was taken off the case, and Hollis was a poor substitute.

I see White’s entry as an attempt to bring more serious intellectual heft into the organization. Some military men have declared that more soldierly than academic skills should have been brought in to counter the communist threat, but my view is that a more subtle assessment of Moscow’s strategies was required. Liddell was sharp, but he was essentially a policeman, and was surrounded by such. The dominant belief within MI5 was that Soviet spies would have to emanate from the CPGB – a policeman’s response, ignoring what Krivitsky said, and Petrie let Soviet counter-intelligence wither on the vine during WWII. The successes of Trevor-Roper (against the Abwehr), Austin (against the Wehrmacht – see https://coldspur.com/summer-2023-round-up/), and, to a lesser extent, Masterman on XX, showed that an Oxford don had a powerful role to play in building up intelligence about an enemy agency. In my piece on Austin, I made the point that his skills and processes should have been applied within MI5 in creating a model of the Comintern, and how it worked. White failed in this exercise, since he did not push for it, and he was in many ways a weak man (and he married a Communist). He failed to see through Burgess, Blunt – even Rothschild – and felt humiliated.

Then there was the problem of leakage. From the Home Office, Jenifer Hart passed on to Berlin and Burgess the details of the Krivitsky business. One must also have questions about Stephen Alley, who translated between Archer and Krivitsky. He is still largely a mystery, with maybe torn allegiances. The NKVD had an opportunity to move, sway MI5 opinion, and stifle any further investigations.

The lack of resolve in tracking down Philby ‘the journalist’ astonished me at the time. If you have read what I wrote about Philby last year: see https://coldspur.com/litzi-philby-under-the-covers/, https://coldspur.com/kim-philby-always-working-for-sis/, https://coldspur.com/kim-philby-in-1951-alarms-and-diversions/ (especially), and https://coldspur.com/kim-philbys-german-moonshine/, you will learn that White clearly ignored much of the evidence in 1951, even though it had been sitting in MI5 files for a long time, and it was left to Milmo to point out the obvious.

And my recent research on Smolka, and his relationship with Philby, introduces a far more important dimension. My hypothesis has been that Philby, when the Nazi-Soviet pact was announced, essentially pretended to break away from the Comintern and offer his services (alongside those of Litzy) to MI6, where Claude Dansey was having his whimsical ideas of ‘turning’ known Communist agents (including Ursula Kuczynski and Smolka) into assets for the Secret Intelligence Service. Philby fitted into that pattern. It was a disaster that MI6 has ever since tried to cover up. But, if Philby had been regarded as a friend in late 1939, it would explain why following up, in January 1940, on his activities in Spain would have not been given much attention. After all, Philby would have explained them away. But one of the reasons he moved when he did was because he knew what Krivitsky was saying in the USA, and probably that MI5 was planning to ask him over . . .

Mr Even-Shoshan was sympathetic to my analysis, responding as follows:

I agree with you totally that a more subtle assessment of Moscow’s strategies was required than a pure policeman’s approach and therefore an academic’s approach and experience would have been appropriate. You mentioned Trevor-Roper’s work at the RSS on the Abwehr. I would add, to make the point sharply, his RSS/RAB colleague Stuart Hampshire’s Nov. 1942 report ‘Canaris and Himmler’, where SH “concluded that this struggle [with Himmler’s SD] for secret intelligence was a symptom of a wider struggle for power between the Nazi party and the German General Staff.” (Adam Sisman, An Honorable Englishman: The Life of Hugh Trevor-Roper, p. 121). This conclusion of RH is, of course, of crucial importance to the question of whether WWII could have been ended much earlier through a negotiated peace with certain forces in Germany. And this, of course, links to Philby’s baleful impact as a Soviet agent – I recall that HTR said Philby prevented this report from going to the British leadership or, perhaps, even just to the top of SIS. It was in the interest of Stalin that the war drag on until Stalin was able to extend his power westward through his eventual “satellite” Communist states–and also to increase his influence in Western Europe through the CPs (especially the French CP), which were able to gain stature as resistance forces. I think you have downplayed Philby’s actual impact on affairs as compared others in the Cambridge Five. But could this one act of Philby have been of great consequence?

This addition of Hampshire to the list of dons was a useful one, and I was able to locate the cited report in a file described, however, as containing exclusively contributions by Trevor-Roper, namely HW 19/347 at Kew, as listed by Edward Harrison in his Introduction to Trevor-Roper’s Secret World. I subsequently commissioned photographs of the file. Yet the result was puzzling: Sisman gets the year of the report wrong (it is dated June 5, 1943), Hampshire’s name is never mentioned, and the tone of the report’s conclusions is much less dramatic than is implied by Sisman. Moreover, the writer offers no sources for his anecdotes outside two references to Philby’s memoir. Sisman’s reliability as a chronicler must be questioned: it is as if Trevor-Roper (or Hampshire, perhaps) wanted to embellish evidence of his colleague’s treachery in order to enhance the record, and distance himself from the mole.

As for my assessment of Philby’s relative influence on military outcomes, I do not recall ever analyzing this topic in detail. I shall simply point out here that Philby started providing intelligence much later than the other members of the quintet, and he was initially distrusted. An interesting matter to be pursued another time, perhaps.

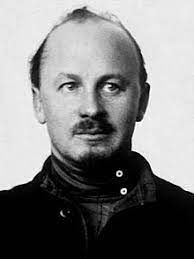

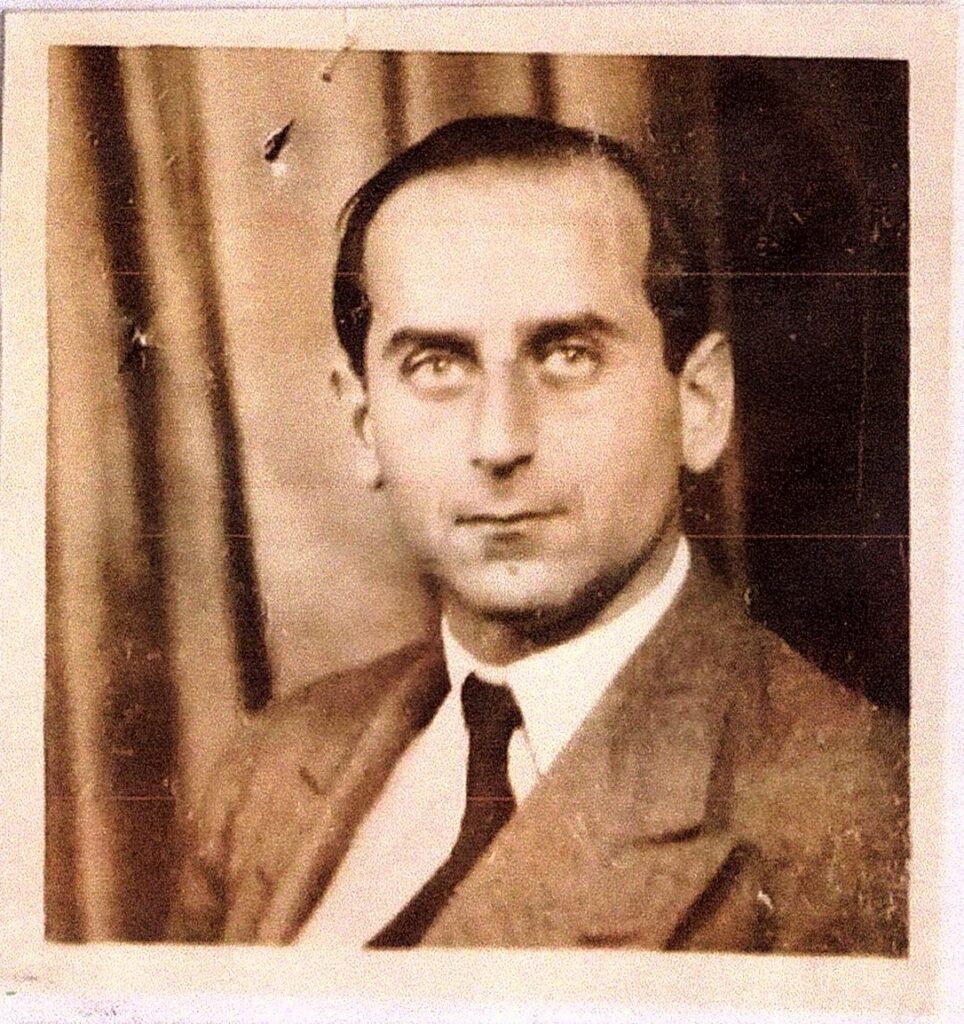

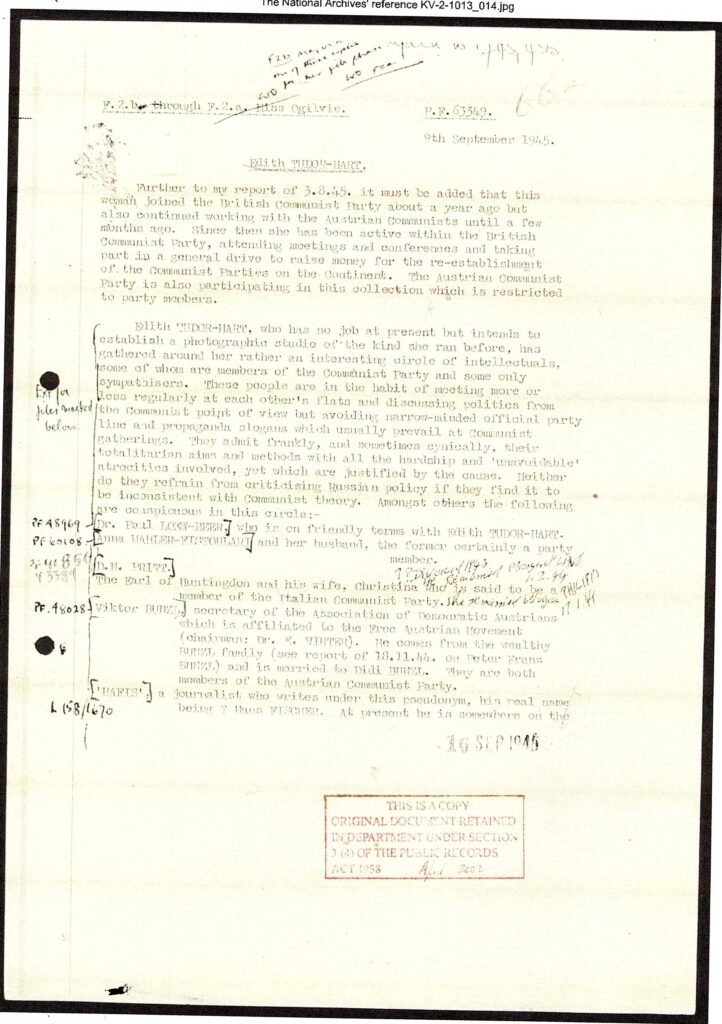

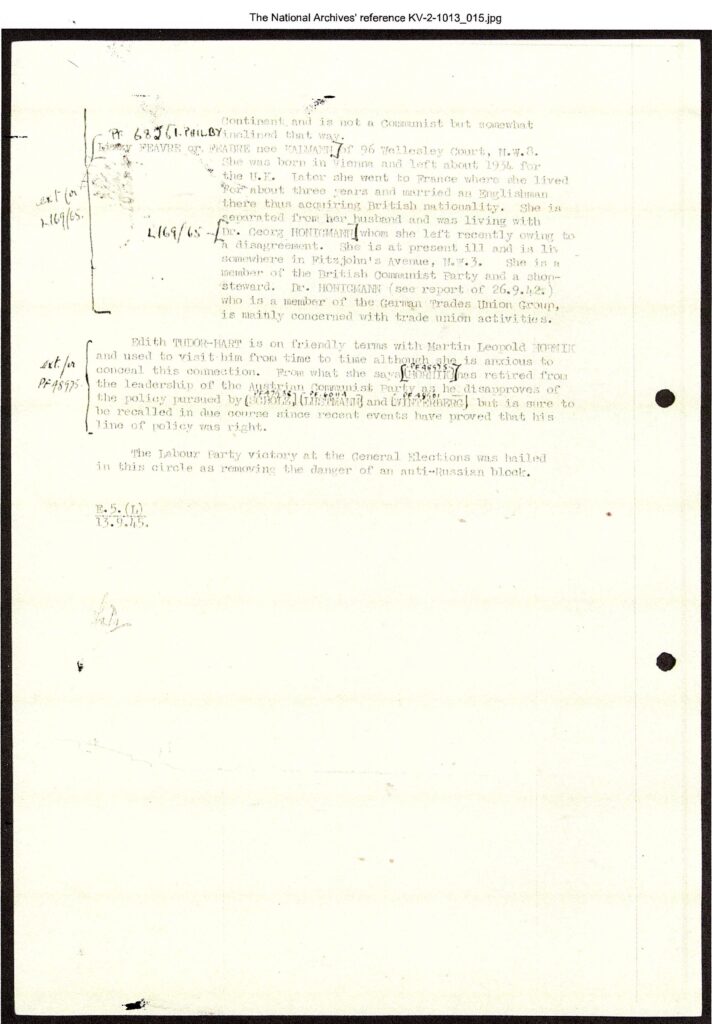

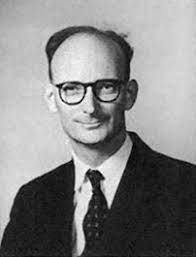

Re-Assessing Dick White’s Plot

One of the reasons why Mr Even-Shoshan’s letter was so timely was the fact that I had been planning to write about Dick White’s very bizarre behaviour during the compilation of his report on Philby in the autumn of 1951. In my Year-End Round-Up published last December, the leading sentence in my ‘Research Agenda’ section ran as follows: “I want to explore more thoroughly where Milmo derived his facts about Kim and Litzy in his December 1951 report, and why White failed to disclose them in his report issued just beforehand.” To summarize the relevant facts concerning White’s activities (as described in https://coldspur.com/kim-philby-in-1951-alarms-and-diversions/ ):a file on Philby had been maintained since 1934 (PF 40408 – and, incidentally, someone has whispered to me that this folder contains over 16 discrete files); Dick White had instructed Milicent Bagot to use this file when preparing the dossier for the FBI/CIA before the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean; and he had had access to it for his summer 1951 report, the release of which was curiously delayed until November. Yet he had used it very selectively.

For a comprehensive background on the events of 1951, I recommend to readers that they return to the second half of my post from April 2019 (https://coldspur.com/the-importance-of-chronology-with-special-reference-to-liddell-philby/) and my account, two months later, of Dick White’s scheming (https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-devilish-plot/). This plot was designed so that MI5 could pass confidential information, via Robert Lamphere in the FBI, to the CIA so that the latter could inform MI6 of their strong suspicions about Philby, thus forcing a breach between MI6 and Philby that would not be attributed to White and MI5. Readers should recall that White had communicated his intention to mislead Lamphere and the FBI as early as May 25, the day that Burgess and Maclean disappeared, and that his representative in Washington, Geoffrey Harrison, acknowledged the scheme four days later. The purpose of this month’s bulletin, in the context of my exchange with Mr. Even-Shoshan, is to focus on Dick White’s character, motivations, and abilities as reflected in his very deceptive and discreditable performance in 1951, and to draw long-term conclusions about MI5’s failures in counter-espionage.

I have just re-read those posts of five years ago, and I would hardly change a word. My findings since have only reinforced the conclusions I made then, adding further evidence to support the hypotheses of Dick White’s misplaced ingenuity, and of Lamphere’s conspiratorial support. What I did not cover at the time were the exact circumstances behind the material that Martin released to Lamphere of the FBI when he and Sillitoe visited Washington in June 1951, where that information came from, why some highly confidential facts about Krivitsky were included, why the reaction of the FBI concerning Krivitsky seemed so passive at the time, or why the exact role of the CIA’s Bill Harvey has since been obscured. One major fresh consideration to be taken into account, however, is my recent conclusion that Philby had made a false renunciation of his communist allegiances to MI6 in 1939, just before the Krivitsky interrogations. In my opinion MI5 and MI6 would therefore, in 1951, have had additional reasons for being on guard against possibly traitorous behaviour from Kim and Litzy. The details of White’s plotting come into sharper focus because of the events of 1939.

Milicent Bagot’s Dossier

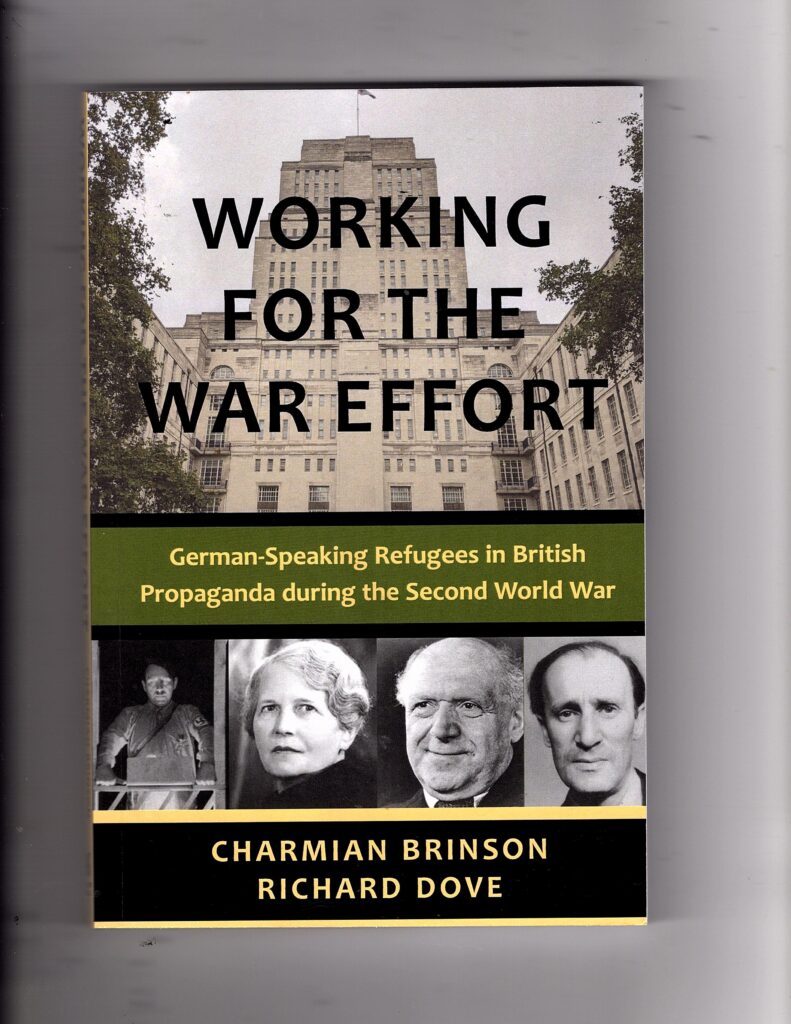

The MacGuffin in the plot is the dossier prepared by Milicent Bagot at the request of Dick White. While White claimed to his biographer that this was compiled only after Martin and Sillitoe returned from Washington, it is obvious that Martin took it with him to show to the FBI agent Robert Lamphere. And White must not simply have asked for a general trawl to see what could be found: he must have been very familiar with the Philby file where everything relating to its subject had been collected. A very telling detail is released in The Perfect English Spy, Tom Bower’s biography of White, where Jane Archer (who was assisting Bagot on the project, having recently returned to MI5 after her spell under Philby in MI6) is shown to contribute a breakthrough finding. White misleadingly presents its timing as occurring after his interrogations of Philby in June 1951. The passage runs as follows (and was provided to Bower by a confidential insider at MI5):

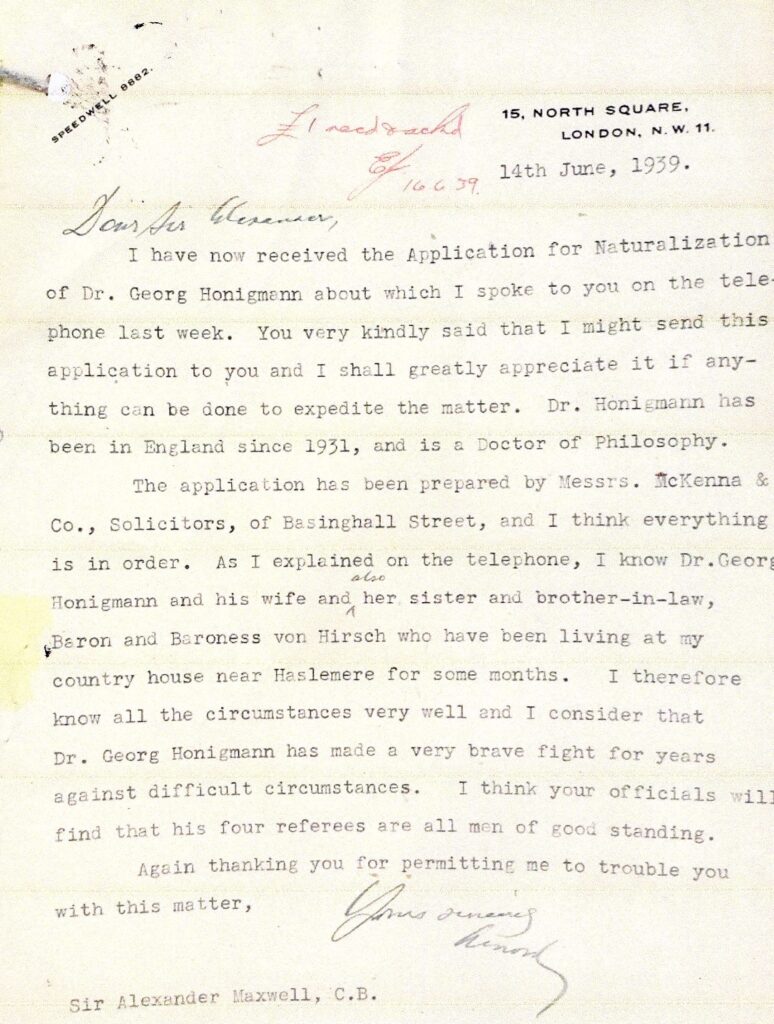

Shortly after that encounter, White immersed himself in the research prepared by Arthur Martin and Jane Archer about Philby’s past. For the first time, Archer produced a thin MI5 file compiled in 1939 and then forgotten. A report contrasting Philby’s communist sympathies at Cambridge and his sudden espousal of fascism made a deep impression. Alongside was Philby’s own résumé. One coincidence was interesting. Philby mentioned his employment by The Times covering the Spanish civil war. Krivitsky had claimed that among the Soviet agents he controlled from Barcelona was one unnamed English journalist.

Now the significance of this sparkling item from a file that was by then – contrary to how White characterized it – quite thick may not come as a shock to any dedicated coldspur reader, but to the uninitiated, it should have sent out some shrill warning signals. What was Philby doing in 1939, providing details of his career to MI5, and even admitting to his role as a journalist working in Spain? Why was he providing a résumé when he was not being interviewed for a job with MI5? The submission of this data to his file occurred just before Krivitsky arrived in the UK: how could it happen that MI5 failed to follow up at all and make the obvious connection? The reasons for this paradox appear to have eluded all the other historians. Yet the facts fit in perfectly with my theory that, in September 1939, Philby concluded a deal with MI6 and MI5 whereby he admitted his past career working for the Comintern, but agreed to switch back his allegiances to his fatherland, and bring along Litzy with him, while they would both pretend to be working for the Soviets still. In such circumstances, MI5 and MI6 would acknowledge Philby’s journalist role in Spain, but they would forgive it as a youthful mistake.

The reference to Krivitsky is very poignant, since an even more prominent hint was dropped by the defector about ‘the Imperial Council spy’. The placement of these two items by Jane Archer (who wrote the summary back in 1940) is fascinating, and significant in the light of future events: the description of the Imperial Council leakage appears prominently in the Appendix to Chapter 2, concerning OGPU agents in the Foreign Office and Diplomatic Service. Archer qualifies Krivitsky’s suggestion that the candidate attended Eton and Oxford by adding that Krivitsky conceded that he might have got those details wrong. The item about the ‘young Englishman, however, ‘a journalist of good family, and idealist and fanatical anti-Nazi’ recruited by Theodore Maly to assassinate Franco, appears only as a marginal note under Maly’s entry in the list of Soviet Agents mentioned by Krivitsky. It could well have been overlooked by the casual reader – but not by the experts.

I here re-present the seven points in the package delivered by Arthur Martin to Lamphere, as they appeared in my April 2019 bulletin:

- Maclean, Burgess and Philby had all been communists at Cambridge

- Philby had become pro-German to build his cover story

- Philby had married the communist Litzi Friedman

- Krivitsky had pointed to a journalist in Spain (who was in fact Philby)

- Philby was involved in the Volkov affair

- Philby was involved in infiltrating Georgian agents into Armenia

- Philby was suspected of assisting in the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean.

What is important to note is that most of this list was prepared before Maclean had been officially identified as the ‘Imperial Council spy’, and thence as HOMER. (Item 7 clearly had to have been added after the May 25 debacle.) Yet that conclusion had not been communicated to the FBI, and the relevant datum is not included in the list, which focuses sharply on Philby. Armed with it, Martin flew out to Washington at the same time that Philby was returning to London on his recall.

The Strange Reactions of Robert Lamphere

One puzzling aspect of Lamphere’s account of the briefing is the fact that it is not absolutely clear that all that he describes (on pages 232-237 of The FBI-KGB War) derives from the memoranda that Martin brought with him. The dominant impression given in his narrative was that the whole cavalcade of facts concerning the careers of Maclean, Burgess and Philby came from Martin at that time, but he also hints that he fleshed out his story with information learned since then. (His book came out in 1986.) What he wrote is not precise:

The memoranda that Martin gave to me outlined the lives of all three men as they were then known to MI-5. Over the years since 1951, many details have been added to the portraits of Burgess, Maclean and Philby, but the basic facts of their lives remain substantially the same as when I first learned the details that June.

Thus we cannot be sure how much of what Lamphere reports thereafter derives from the Martin memoranda, and what is later embellishment – or even correction.

In any event, it is salutary to compare his description of how the revelations occurred with that of White. Lamphere described Martin’s visit by recording his own remonstrations about MI5’s lack of honesty over its closing in on Maclean, and then by emphasizing his own suspicions about Philby in the Burgess-Maclean disappearances. The exchange went as follows:

“That makes it doubly hard for me to admit all this. However, I have for you now several memoranda which go into the background of Burgess and Maclean.”

“Where does Philby fit in? Burgess was living with him.”

Somewhat relieved, Martin replied, “Most of what I have to tell you relates to Philby. We now have the gravest suspicions about him.” (The FBI-KGB Wars, p 232)

This strikes me as stilted and artificial. Why, when being offered some surely intriguing morsels about Burgess and Maclean, would Lamphere sharply switch the subject to Philby? And why, if Martin was planning to divulge some critical information about Philby anyway, would he be ‘relieved’ that Lamphere brought the subject up?

Dick White presented it otherwise to his biographer. After reporting how Sillitoe and Martin had experienced their awkward interview with Hoover, in which Hoover ranted most of the time, Bower’s narrative runs as follows:

Arthur Martin’s subsequent conversations with FBI officers, especially Lamphere, were focused upon Burgess. As recollections of the antipathy and outrage they had felt towards the dishevelled diplomat were rekindled, the Americans recalled that that his host, Kim Philby, had been remarkably supportive of him. (The Perfect English Spy, pp 120-121)

Again, this is a strained path of logic, contradicting what Lamphere wrote. In any event, Philby’s behaviour towards Burgess might have been caused by natural loyalty. Burgess had been shown to be a boor, but there had been no evidence that he was a spy. If he had been, and Philby did not know about it, he would have supported him. On the other hand, if Philby were guilty, too, one might have expected him to distance himself. The two accounts are certainly at variance, even though both of them attempt to show a natural progression for the discussion switching rapidly to Philby.

Yet other passages are more precise. For example, Lamphere devotes a paragraph to the Krivitsky affair, although he does get the date of the interrogations wrong, and he inserts an ‘as you’ll recall’ to the reader, suggesting that some of what he writes about is information imparted earlier. He then highlights the claims that Krivitsky made about two agents: one ‘a Scotsman of good family who had been educated at Oxford and Eton’ – erroneous in detail, of course, and corrected by Lamphere in his text; and the other ‘a journalist, a man who had been with the Franco forces during the recent Civil War’. And he cites, as the fourth of the ‘Seven Points’ the fact of Krivitsky’s referring to the journalist in Spain, and that it had been used as one of the arguments pointing suspicion at Philby.

Yet what astonishes me is Lamphere’s reaction. His first (and only) impulse is to express the wish that he would have liked to interrogate Philby on all these matters. (He was unable to, primarily because Philby had already been recalled to England, but the spy would obviously not have agreed to be ‘interrogated’ by a foreign intelligence officer.) If, as Lamphere claimed, this was the first occasion when he had learned of the political leanings and disloyalties of those three prominent persons, one would have expected him to have expostulated, and demanded to know how long the British had known those facts. His passivity is inexplicable: he must have been confided in already. Moreover, it would have been scandalous for MI5 to have passed across highly incendiary documents to a foreign power without very tight safeguards. The whole process had been set up.

Moreover, Lamphere appears utterly unimpressed with the factoid concerning the journalist. One might have expected him, if had encountered the Spanish reference beforehand, to declaim: “What? You can now associate the journalist in Spain with Kim Philby? When did you achieve that?” Yet he is totally unsurprised. And what he did not do was to request a copy of the complete report on Krivitsky, which would appear to have been a much more sensible and professional response. After all, Krivitsky was well-known in the USA, had given evidence to a congressional committee, had published a book, and had been assassinated (almost certainly) some time after his return. Would not any smart, inquisitive intelligence officer have wanted to inspect the primary source material? Is it possible that Martin had brought a copy of the full report with him?

I thought it unlikely. The report was a bulky one. Lamphere refers only to ‘memoranda’. If he had seen the full report, one would expect that he would have written about it. By 1986, its contents of were public knowledge. Gary Kern, in his superb study of Krivitsky, A Death in Washington, credits Gordon Brook-Shepherd with breaking the news about Krivitsky in his Storm Petrels, published in 1977, in which he gave a full account. Brook-Shepherd had clearly been given access to the Krivitsky file by MI5, and authorization to write his book, in an attempt to reverse recent Soviet propaganda claims. It is true that the report (or at least a summary of it) had been circulated to government offices in 1940 by Vernon Kell, as Kern relates, and as I explained in Misdefending the Realm, including the Home Office, where the spy Jenifer Hart saw it. Yet that meant that the beneficiaries would have been the Soviets, not the Americans, and if anyone had passed it on across the Atlantic, I concluded that the revelations would surely have prompted questions well before 1951.

Deeper Implications

On the other hand, why did White, after requesting Milicent Bagot to create the dossier on Philby, and presenting it to Martin to pass on to the FBI (without the knowledge of White’s boss, Percy Sillitoe), include such a provocative and incriminating lead in the package? After all, even if the FBI/CIA had learned through some clandestine source about the tip concerning a journalist in Spain, they probably never knew that Philby fitted that profile, and thus would not have made the connection! True, it might add another brick to the rapidly growing structure of evidence against Philby, but, at the same time, the disclosure opened up the possibility of serious accusations being laid against MI5. If the Security Service had had this factoid in their hands since 1940, why had it not been able to follow up the lead, and identify Philby? There could not have been that many British journalists working closely with Franco in Spain in 1937 – certainly fewer than the number of diplomats who might have had access to confidential material in the British Embassy in 1944-1945 . . .

Either White was behaving remarkably stupidly, or he had come to an agreement with his American counterparts already, or he was trying on a risky bluff. In any case, he received the reaction he wanted. When Lamphere passed on the memoranda to his ex-colleague Bill Harvey, now in the CIA – an action incidentally not recorded by Lamphere, who grants Harvey and Bedell Smith the perspicacity of coming up with the same conclusions independently – Harvey latched on to items 3 and 5 on the list, namely the fact that Philby had married a known Soviet agent Litzi Friedmann, and the circumstances of the Volkov affair. He also introduced the ELLI phenomenon originating from Gouzenko. The exposure of the Krivitsky hints, and the lack of follow-up, appeared to have been forgotten.

And then I recalled vaguely an item in the PEACH archive, from KV 6/142-2, and retrieved it. Serial 351A, dated April 9, 1951, consists of a letter written by MI5’s man in Washington, Geoffrey Patterson, to the Director-General (Sillitoe). The second paragraph runs:

When I visited Lamphere today he asked me casually whether we had ever given the F.B.I. a copy of Krivitsky’s statement about the source in the Foreign Office. I told him I did not know and that there was no copy in my office. He then told me he would make enquiries within the Bureau to see what they had. Patterson continued:

I think we can assume that Lamphere’s mind is running along parallel lines to our own and that it will not be long before he asks us which members of the Embassy fit in with Krivitsky’s description. By a process of elimination he will probably end up with the same conclusions as we have.

This was extraordinary! Lamphere worked for the FBI: why would he be referring to it as a separate entity? He himself was obviously familiar with the (perhaps partial) contents of the Krivitsky report already. He must have been shown it in confidence – no doubt by a colleague in MI5, presumably Patterson. Yet, if had encountered the ‘journalist in Spain’ reference at this time, he would not have seen it as having any relevance to the HOMER investigation. Patterson in turn showed that he was familiar with the material, and that he had surely read the report (and not simply been informed of its contents), since he admitted that there was no copy in his office. He also showed that he thought it quite regular for Lamphere to be familiar with the report, perhaps carelessly forgetting that he had shared it with Lamphere confidentially, and betraying that fact to history. Why would Patterson not be surprised by the fact that Lamphere alone has knowledge not available to the rest of the FBI, and had not passed on the information to his colleagues, unless he and Lamphere were alone privy to the deal? The exchange is all very phony.

In addition, the irony of this episode lies in the fact that Patterson was then working closely with Philby to try to determine who the spy in the Embassy was. Philby would have become aware of this exchange, and of the fact that Lamphere had access to a vital pointer to Maclean. He might thus have also suspected that Lamphere knew about the journalist in Spain, which could have been alarming. Was MI5 trying to put the wind up Philby, to draw him out? Philby knew that Maclean was HOMER, of course, and the current hunch of the British cross-Atlantic team was that Maclean was indeed the prime suspect, with Gore-Booth an alternative. Indeed, Philby pushed the latter theory: Gore-Booth had the unfortunate qualifications of having attended Eton and Oxford, which temporarily placed him Number 1 on the charts in the Foreign Office assessments. Yet MI5 and the Foreign Office did not want to let the Americans know of their conclusions before they were ready to move, and they also did not want the Americans to work it out themselves.

At this time, the British were making careful comparisons between Krivitsky’s description of the ‘Imperial Council Spy’ and Maclean. Was the FBI following similar leads, with inferior information? No result of Lamphere’s investigations has survived, but on April 18, a remarkable letter from Arthur Martin of B2b (yes, him of the FEABRE/HONIGMANN/TUDOR-HART saga) to Patterson appears on file. A critical paragraph runs:

I don’t think we need worry unduly about the F.B.I request for a copy of Krivitsky’s statement. In fact they received from us, through S.I.S., an expurgated version of what KRIVITSKY said which omitted any reference to the “Imperial Council” source. However, they would undoubtedly have heard of this source from Don LEVINE who, you will remember, ‘ghosted’ KRIVITSKY’s book and would almost certainly have received this information during his conversations with KRIVITSKY. If the F.B.I. raise the subject again I think you should simply feign complete ignorance but if they press hard agree to refer the request to me.

This note reflects the fact that, at a meeting in London on April 17, Dick White had reported that the FBI had asked for a fuller [sic] version of the Krivitsky material. Lamphere had presumably followed up, discovered that the Bureau had located its expurgated copy, and was now requesting the full Monty.

What to make of all this?

- MI6, whenever they forwarded the Krivitsky report to the FBI, had obviously been sensitive and embarrassed enough about Krivitsky’s references to the ‘Imperial Council’ source to want to conceal the information. (What else did they hide, one wonders? And did they redact it in a noticeable fashion, or merely re-present the harmless sections?)

- Unless Lamphere was dissembling, he was in April unaware that anyone in the FBI had seen the report. And maybe it had been buried and forgotten: certainly he had not been able to rely on his bosses to share its contents with him.

- On the other hand, Lamphere had been confided in by MI5 to the extent that he knew about (some of, maybe all) the expurgated sections, but had apparently withheld the nature of this confidential statement from his colleagues in the FBI. That explains his lack of interest in seeing the whole report, and instead his expressed desire to interrogate Philby.

- Martin (as is habitual) had been kept in the dark. He failed to distinguish between the FBI in general, and Lamphere in particular, and somehow thought that Patterson, if pressed, would be able to feign ignorance if Lamphere were to raise the topic of the ‘Imperial Spy’ with him. This was despite the fact that Patterson’s earlier correspondence indicated irrefutably that he, Patterson, had discussed the topic with Lamphere.

- Martin was again shown as being somewhat slow. He failed to detect the difference between the full Krivitsky material and the expurgated version, or to realize why the FBI might want to see the former.

- Lamphere’s loyalties and sympathies would appear to have been as much with MI5 as they were with his employers, the FBI. (He bore some animosity to the chief of the FBI, Edgar J. Hoover.) Moreover, his first step when Martin arrived with the incriminating dossier was to leak it to his ex-FBI colleague, Bill Harvey, now working for the CIA. Yet he concealed this action in his memoir, and made no mention of Harvey’s report, or its introduction of ELLI. It strongly suggests that Lamphere was a party to White’s Devilish Plot.

- Lamphere may even have been obstructing the official American inquiry, since memoranda on file indicate that he stated, as late as May 1, that he was still undecided as to whether the spy was British or American, and that he wanted attention spent on Halpern. This trend is reinforced by the fact that, as the FBI was reported to be heating up its inquiries, on May 7, the bureau was reported by Patterson to be ‘thinking in terms of HALPERN and FISHER’.

- In his report to Bedell Smith condemning Philby, Harvey of the CIA focused on the Volkov affair, and Philby’s marriage to Litzy, while introducing the Gouzenko references to ELLI in place of inspection of the Krivitsky reference. That was probably because he could not have been expected to know about Krivitsky’s description of a journalist in Spain, let alone that that role could have been linked to Philby. In addition, it helped to distinguish his conclusions from what Martin had passed to Lamphere.

- White’s gesture of help towards Bedell Smith may have arisen from his service with the General towards the end of the war. (White had been appointed deputy counter-intelligence adviser to Bedell Smith, then Eisenhower’s chief of staff.) Bedell Smith had rebuked White for openly opposing USA policy over counter-intelligence issues: at the time, White had not felt confident enough to hold his ground.

Yet the most dramatic conclusion must be the fact that some weeks before Burgess and Maclean disappeared, when Maclean had still not been solidly identified, when Burgess was officially not regarded as involved at all, and Philby was not only out of the picture but part of the team working on the leakage, MI5 had been preparing a dossier that essentially presented not just Maclean, but also Burgess and Philby, as long-term Soviet agents. (What information MI5 had gathered on Burgess, and what suspicions the service had about him at this time, are important questions – as some coldspur readers have pointed out – that will have to be deferred for analysis another time.)

White’s Predicament

It is no wonder that White attempted to present the sequence of events as markedly at variance with the facts. He had to pretend that the project of identifying Homer had focused on Maclean, and that MI5 had no suspicions that Burgess was involved – or even harboured any concerns about Philby’s involvement. He had to imply that the first accusations against Philby came from the CIA, and that Philby returned after the visit by Sillitoe and Martin. He had to conceal the mission undertaken by Martin to leak the dossier to Lamphere. He had to claim that it was only after Martin’s return from Washington that a proper investigation into Philby’s past was undertaken, and that, with Bagot’s help, a dossier was then created and passed to MI6’s chief, Stewart Menzies. As I have described elsewhere, White’s description of events, as relayed first to Andrew Boyle and then to his biographer, Tom Bower, is a tissue of lies. Moreover, it is as if Bower, who lists Lamphere’s book in his bibliography, and uses it in his endnotes, did not read it properly, since he fails to identify the contradictions, ignoring completely Lamphere’s account of how Arthur Martin passed him the detailed dossier. It is worthwhile here recapitulating – and slightly expanding – White’s version of events, as essentially displayed in Chapter 5 of A Perfect English Spy.

In the early days of the investigation after Burgess and Maclean absconded (May 28), MI5 was very much reliant on the testimony of Goronwy Rees, who had volunteered information about Guy Burgess, Burgess having left a message for Rees just before he disappeared. Even though Burgess was quickly confirmed as the person who had rented the Austin A40 left on the quay at Southampton, Dick White claimed to his biographer that he could not believe that Burgess had been an accomplice to Maclean. He said that he was astonished at Rees’s descriptions of Burgess’s past, even though Anthony Blunt, a close friend of Guy Liddell, had helpfully suggested that Burgess might have escaped with Maclean. This was all clumsy dissimulation, in light of the contents of the dossier compiled for Lamphere.

Yet, when White described the meetings between Arthur Martin and Lamphere, he indicated that the conversations were focused on Burgess. This is astonishing, as the main part of the dossier outlined by Lamphere – which White does not mention at all – concentrated on Philby. White attempted to explain this outcome by virtue of the fact that the Americans recalled that Philby had been very supportive of Burgess, and that their investigation therefore was re-directed at Philby. This was simply a clumsy effort by White to explain why the coming broadside from Washington was targetting Philby, when White himself had set up Lamphere & co. with the ammunition.

White went on to state that, soon after Sillitoe’s return to London (actually on June 18, alongside Martin, who had held his meetings without Sillitoe in attendance), ‘a long message arrived from Philby’ offering his thoughts about Burgess. That implies that Philby was still in Washington, but in truth he had already been recalled by Menzies, and he arrived the day after the departure from London of Martin and Sillitoe (on June 12). White would also have in mind another infamous message, suggesting that Maclean might be the guilty party, which Philby had sent on April 2 (see KV 6/142). Yet Philby wrote a further attempt to distract attention from himself on June 4, when he indeed wrote to Menzies about some of Burgess’s dubious habits, and his suspected Marxism. That must be the missive to which White was referring, although why a telegraphed message should have taken so long to arrive on White’s desk is highly questionable. His dating of its arrival serves to postpone the timing of Philby’s departure from the USA.

Thus White’s account of the process of interrogating Philby is mendacious. In his recollection, after the return of Sillitoe and Martin (undated, of course, but actually June 18) White approached Jock Sinclair of MI6, and convinced him that Philby would be of use in London in the inquiries. (Philby had already been in London for a week.) Jack Easton then sent a handwritten message to Philby warning him of an imminent recall – which was in no way ascribable to any misdemeanours. And only at that stage, according to White, did MI5 set to work, preparing for Philby’s return:

Over the next few days, White and Martin diligently compiled a record of Philby’s work. There was the discovery that Philby’s first wife, Litzi Friedmann, was an Austrian communist. In 1946, White had been asked by SIS to check on Litzi after Philby had applied for permission to divorce his youthful transgression . . .

There was also Philby’s handling of the Volkov defection in 1945. Konstantin Volkov’s offer to defect had been negotiated with John Reed, a first secretary at the British Embassy in Turkey. . . .

Bower notes without comment that no attempt was made to question Reed before Philby’s return from Washington. Of course, it is absurd to accept that MI5, having maintained a dossier on Philby, would acquaint itself with its contents only at this late stage of the game. If White, as he admitted, had been involved with the embarrassing business of Kim’s wanting a divorce from Litzy in the summer of 1946, when her background was well-known, how could he have suddenly ‘discovered’ those facts in 1951? All the work had already been performed for Martin’s and Lamphere’s benefit.

Next followed the interrogations. Easton had been provoked to have suspicions about Philby himself, but why Sinclair did not object strongly to the process, having been told that Philby’s recall was imply for amicable discussions, is not explored by Bower. White was not practiced in interrogation, and did not prepare himself properly: thus he failed to get any admission or confession out of his subject. Philby simply stuck to his guns, and refused to admit anything, or to concede any of White’s points, knowing that without a confession his accusers were powerless. There was a certain farcical aspect to the exchanges, however. As Philby and White jousted over the funding of Philby’s trip to Spain, White knew that the NKVD had been his paymaster, while Philby had to pretend otherwise in order to ward of Jack Easton, innocently attending the interrogations.

Irrespective of White’s mendacious account of the events, and the inability of his biographer to unravel its contradictions, a balance-sheet of White’s situation can be drawn up. On the credit side, Philby had been forced to resign; the FBI and CIA appeared not to be disturbed by the revelations, which could have rebounded harshly on White and MI5 generally; White’s devious tricks had not been picked up by Petrie or Liddell; his cohorts of Martin, Archer and Bagot kept their silence; hardly anyone outside the intelligence services would have ever heard of Philby; and Attlee and his administration were too consumed with other matters to want to stir up trouble with spies On the debit side, MI6 was not unified in its attitude to Philby, with Sinclair, Vivian and Nicholas Elliott stoutly defending him, Easton supportive (until July, when he became a fierce critic), and Menzies forced to sit on the fence; the flurry of documents circulating could well have come to the attention of politicians who might ask why on earth MI5 had been so sluggish; Guy Liddell was pursuing the eponymously named PEACH inquiry into the possible misdemeanours of Philby; the Foreign Office, in the guise of the Washington Security Officer, James Mackenzie, was also revisiting Philby’s behaviour in Washington; and Harvey in the CIA had resuscitated the spectre of ELLI, something White considered a dead issue by then, but one which could have opened a whole fresh disclosure of uncomfortable secrets concerning SOE and the Soviet Union from the war period.

Dick White surely hoped that things would blow over. But unconnected events suddenly changed the rules.

PEACH

After the interrogations, Dick White had reportedly submitted a report to Menzies constituting the case against Philby. It has not come to light. According to what White then told Andrew Boyle and Tom Bower, he then busied himself with an intense study of the connections and affiliations of the Cambridge graduates of the early 1930s, remorsefully admitting that MI5 had not been thorough enough. Yet he also complained that the establishment resented their digging around, and its members in influential places came to their friends’ defence. This was much of a sham show by White: he had had ample time to consider the facts back in 1939 and 1940, when Philby’s malfeasances had come to notice. Moreover, he still showed loyalty to Anthony Blunt, who had also been an Apostle at Cambridge, had visited the Soviet Union in 1934 with Burgess and (despite what Bower writes), had remained friends with him, and had maintained his communist opinions, as was evident when he was recruited by MI5 in 1940. That was an utterly naïve display by White.

MI5’s initial focus during the PEACH inquiry seemed to be on confirming that Philby had been a Soviet agent. Yet what did that mean? The Security Service had no evidence that he had passed on secrets of any kind: he was not trapped from VENONA decrypts. With the Foreign Office investigations, the attention appeared to shift smoothly to another domain: ascertaining whether Philby could have been the man who had alerted Maclean to the imminent interrogation, thus proving his guilt. This line of inquiry was flawed on three counts: the ability of Philby to gain up-to-date information, and then communicate with Maclean from Washington, must have been thin, to say the least; the interrogation was not imminent, but planned for a day a couple of weeks later; and, in principle, Philby might have wanted to save the skin of his friend without necessarily being employed by the NKGB. White and MI5 knew better, of course, but it was a politically more astute strategy to pursue the ‘Third Man’ angle.

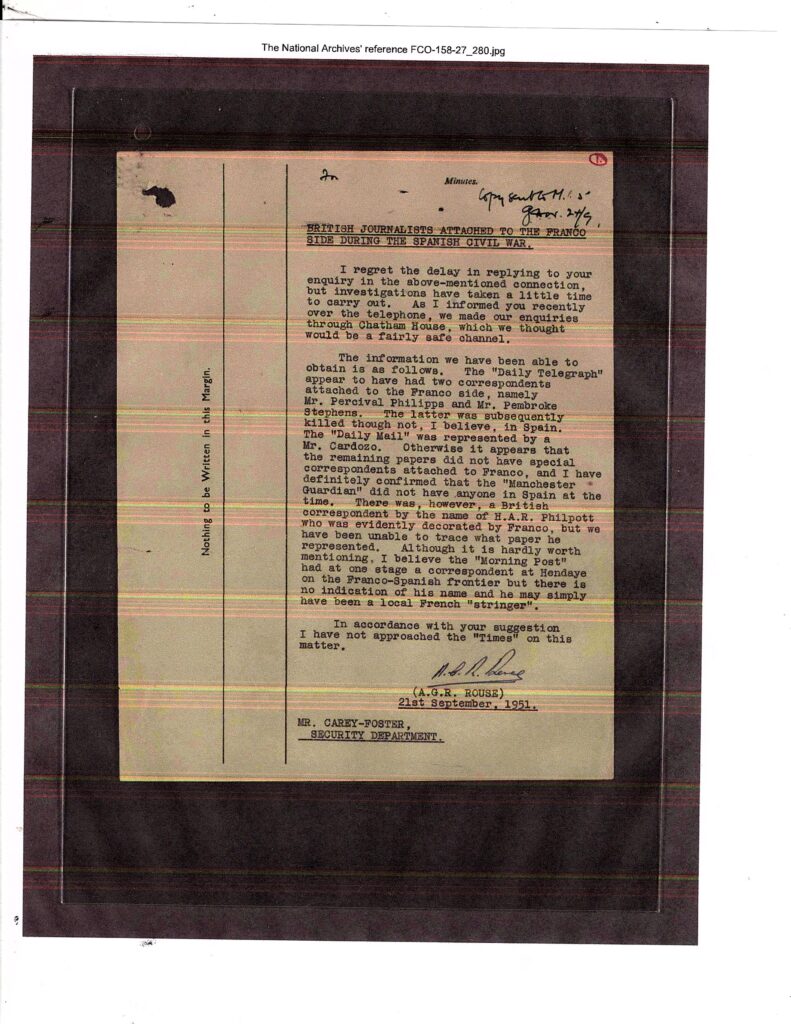

White had tried to disqualify himself from the inquiry, on the grounds that ELLI and Volkov were not in his bailiwick – a rather feeble declaration. Thus the substance and the timing of his report are both very bizarre. During the summer (as I have explained elsewhere) matters started heating up, what with the CIA getting antsy again, and demanding more action, Liddell visiting the USA, and getting messages that he could not rationalize because of his exclusion from the plot, and the Foreign Office also stirring the pot afresh. When Liddell returned from leave in August and wrote that things were looking bleaker for Philby, it is not clear what he was referring to, and White’s report (not issued until the end of November) does not reflect any fresh discoveries – not even the quirky letter that reported that H. A. R. Philpott had indeed been a journalist in Spain in 1937. Why would such a spurious item be so prominently added to the archive at that late stage? Now that Jane Archer’s recovery has been publicized, it appears as a clumsy KGB-type spravka inserted in the file to give the impression that vague pointers to Philby in Spain surfaced only in the summer of 1951.

Thus White’s report, presented without any fanfare or explanation in FCO 158/27 as being distributed on November 30, may have been a modest revision to what he submitted to Menzies back in June. The tone of the text suggests, however, that more serious investigations of material undertaken during the summer had strengthened the case that Philby was a Soviet agent, but the linkage between that assertion and the desirability of determining who had leaked information to Maclean before he escaped is never made clear. The report is in many ways a re-working of the ‘Seven Points’. It is, however, very superficial on the ties with Litzi. It states that Philby did indeed go to Spain as a journalist (as had been declared to Lamphere back in June), but it does not explain how this information was derived. Without identifying the project itself, it adds the details of the VENONA decryption exercise, and the changes which the Soviets made in December 1949. It does not mention ELLI.

Yet it is also mendacious. White cites the Krivitsky testimony, noting that the plan to assassinate Franco ‘did not mature’, and then adds: ‘but Krivitsky says he is pretty certain that the “imperial council source”, namely Maclean, would have been amongst the friends of the young man sent to Spain’. That is nonsense: moreover, Krivitsky was long dead by then, and the use of the present tense is incongruous. Krivitsky is not on record of saying any such thing (I am not sure what the original Russian for ‘pretty certain’ would have been), and there is no linkage between the two in the Krivitsky report. White goes on to repeat, several times, the vague assertion that Philby and Maclean must have been well acquainted, and he uses this claim to conclude that Philby was ‘the most likely person to have been responsible for alerting Maclean’.

The irony was that, even if Philby had managed to warn Maclean of the impending interrogation from afar in Washington, it would have been the least of his considerable sins. White and Menzies must have come to that conclusion, and dreaded what might come out of the woodwork. If only they could just shuffle him off quietly to the side, and hope the story died down . . .

Enter ‘Buster’ Milmo

What upset their musings was the General Election in October, with Churchill’s Tories returning to replace the Attlee administration, and displaying a traditionally more robust response to the evidence of Soviet penetration. As I explained in my May 2023 piece, both Eden and Churchill were badly briefed, and Churchill, with typical impetuosity, insisted that Milmo’s interrogation of Philby be advanced a week, to December 12, only five days after Liddell had accompanied Sillitoe to listen to Eden’s fears about another scandal, and only two weeks after White’s document had been distributed. The main concern seemed to be that Philby would flee the country (one of the reasons why Churchill demanded haste): the belief was that a confession would be gained from Philby, although the implications of putting him in the dock were not clearly thought through. A vague desire of convincing the Americans that ‘we are resolute in clearing up Soviet espionage in the United Kingdom’ was expressed. What was not planned for was an outcome where Philby denied everything, and in which MI5 and the Foreign Office were left helpless in the stand-off.

Milmo was given his instructions on December 3: he conducted his interrogation on December 12. During that time he studied a dossier (‘a very full one’, though how he knew that is not evident) prepared for him, no doubt by Arthur Martin. Again, I shall not repeat my analysis of Milmo’s report from last May: what intrigues me is the fresh evidence that he turned up – clearly not ‘fresh’ to him, as it must all have been new – but fresh in the sense that White had curiously avoided mentioning it. I listed seventeen items that MI5 had appeared to have dredged up during the summer, all of them relating to events before the outbreak of the war. The most startling are perhaps the details of Litzy’s movements in Europe between 1934 and 1937, and her banking arrangements. I find it impossible to believe that these items were discovered and prepared especially for Milmo’s benefit, considering the short time between his appointment and the interrogations. But neither do I think it likely that MI5 came up with these gems by trawling through previously arcane folders in the summer of 1951, or by making requests to the Immigration authorities about her movements. They must have all been in Philby’s Personal File, and they had been entered there at the time that the events occurred.

So why did Dick White appear unaware of them in his report? It is inconceivable that he was not familiar with the details. After all, he had reported to his biographer the item whereby Philby’s role as a journalist had been ‘discovered’ by Jane Archer – a nugget, by the way, that was noticeably absent from Milmo’s Appendix. First of all, his report must have been written some time beforehand, at a time when he thought matters were settling down, and surely not in the knowledge that Milmo was about to embark on another interrogation. Second, the report must have been pulled out to provide evidence that MI5 had been doing some kind of investigation, but it ran the risk of harming the reputation of White and the Security Service because of its shallowness. Yet the most provocative aspect of the dossier is that it closes in 1939, the time when Philby (as I claim) performed his deal with MI5 and MI6. The file no doubt moved into a ‘Y’ category with special security status at that time, and its contents were not made available to casual researchers in MI5. The intent was to show that Philby had been a careless and subversive operator in his early years, but that there was no evidence of any treacherous activity once war broke out.

The risks were enormous, however. Anyone reading Milmo’s Appendix should have expostulated: “You mean, you had all this information on Philby in the 1930s, and you still employed him in SOE and MI6, and promoted him to high positions, even head of Soviet counter-intelligence??”, and wondered why the routine checks were not made. As I have explained before, it is documented that, on June 18, 1940, MI6 made a telephone inquiry to MI5, requesting a trace on Philby, but all the Security Service came up with was a record of his previous membership of the Anglo-German Fellowship. (For example, the item on his role as a journalist in Franco’s Spain, matching the Krivitsky tip, was conveniently overlooked.)

Certainly, only a carefully doctored subset of Philby’s file would have been presented to Milmo for inspection. Milmo might have been presented with the specially crafted September evidence about Philpott the journalist in Spain, but assuredly not the original 1939 entry, so that it would appear that the Spanish connection was only a recent discovery. Yet, in his report, Milmo refers neither to the résumé information that Jane Archer ‘discovered’ nor to the dubious ‘Philpott’ memorandum, instead writing:

There is no proof that PHILBY was in fact the agent referred to in the above statement but this information fits him like a glove and no the alternative candidate has been found.

The ‘above statement’ cites the phrase attributed to Krivitsky concerning his being ‘pretty certain’ about the friendship between the Imperial Council spy and the journalist, so it is clear that Milmo is merely parroting what White had written. He had had no time to undertake any original investigation: the dossier presented to him was not as ‘full’ as he supposed.

Nevertheless, White’s leaving it to Milmo (who worked for MI5 during the war) to come up with the documentation of all those telling stories is unfathomable. He should have been mortified that Milmo would be allowed to be the first to reveal some of the unpleasant secrets in the MI5 files. One can only assume that he had no choice, and matters were by then beyond his control. Alternatively, he would probably have claimed that he never would have had a chance of viewing the records that Arthur Martin and Jane Archer managed to dredge up from the vaults for Milmo’s benefit. Yet he must also have figured that, if someone were incisive enough to question MI5’s thoroughness in this respect, the matter would come back to rebound primarily on Menzies. Menzies and White knew the score, were both party to the confession and deal that Philby engineered, and protected each other, but no one in authority was smart enough to challenge them.

‘The Imperfect English Counter-Espionage Officer’

‘For he himself has said it,

And it’s greatly to his credit,

That he is an Englishman!’ (W.S. Gilbert, HMS Pinafore)

I have previously pointed out that The Perfect English Spy was one of the worst-selected titles for an intelligence biography. Dick White scored one out of three: he was indisputably English. But he was primarily a counter-espionage officer, not a spy. And his performance was frequently poor. Whatever native intelligence he possessed was too often directed at schemes to confound his rivals and allies rather than towards thinking strategically about the enduring enemy. White was treading very dangerous ground, but he must have calculated that no archival material would be released in his lifetime to undermine his account of what happened. In that respect, he was right, but a more careful analysis by his biographer should have pointed out the contradictions.

Mr. Even-Shoshan is nevertheless correct: few of the errors of 1940 can be laid directly at White’s door. After the opportunity that Krivitsky placed before MI5, the service was in confusion. Jane Archer was pushed aside in bizarre circumstances. Vernon Kell was overwhelmed by the illusory German ‘Fifth Column’ crisis, and then deposed. Liddell was ineffectual. Churchill’s Security Executive caused demoralization. The implications of Krivitsky’s death in Washington were overlooked. Petrie came in to restore order, but completely mismanaged the Soviet counter-espionage effort during the war. It was delegated to the unimaginative Hollis, who was charged with keeping an eye on the Party. Others who spoke up about the Communist threat (Harker, Curry, Knight) did not have enough clout, and were not leadership material. By 1945, when White took over B Section, most of the damage was done.

At the outset of war, however, White had been quickly introduced to some of MI5’s major projects. He had opportunities to break through, and shine, but was at that time guileless, too ingenuous. He was present at some Krivitsky interrogations, but he did not trust the defector since he himself lacked appreciation for the cunning and dissimulation essential for spycraft, and he thus classified all Krivitsky’s pointers as worthless. In dealing with Whitehall over the double-cross operation, White decided to be deferential, and that behaviour let him down when he tried to criticize Beaverbrook’s policy for hiring communists. Indeed, Roger Hollis (who had not completed his degree course at Oxford) was more forceful than White over the communist threat. Bower writes that White’s attitude towards communism at that time was ‘benign’. White never raised any objections to Smolka’s employment: he admitted that communist penetration was a side-issue. When Percy Sillitoe was appointed Director-General after the war, and White took over the counter-espionage B Division from Liddell, Hollis remained more hawkish than White. Again, White kowtowed to Whitehall.

White had been the first graduate to be employed by MI5, which was significant, in that it represented a development away from Special Branch police officers and military men. Yet he did not possess a first-rate brain: he had gained only a second-class degree in history at Christ Church, Oxford, and had been assessed by his tutor as being a little slow to ‘get going’. Thus he was not a ‘don’ with a post-graduate degree: in fact he had been turned down for a university appointment. (His mentor at Christ Church, was another history don, John Masterman, who came to work for him during the war, and led the XX Committee). Moreover, White complained, when he belatedly tried to understand the mechanics and structure of Soviet subversion, that he was constantly thwarted by ‘the intellectuals’. On the other hand, he mixed well with the Oxford group – especially what was known as the Christ Church mafia: Masterman, Gibert Ryle, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Charles Stuart, and Denys Page (MI5’s representative at Bletchley Park). Moreover, given his relationship with Blunt, this was a rather simplistic view of the world, and reflected a lack of toughness, of the keen curiosity that is essential for counter-intelligence work.

On the other hand, perhaps reflecting the mutual admiration society of Christ Church men, Trevor-Roper spoke highly of him:

He was a true professional in his methods, but what we most admired was his intellectual lucidity, his equanimity, his unfailing sense of proportion and humour . . . He believed that all problems are soluble by reason; and he never lost his balance.

That would be a positive assessment for a clubbable civil servant, yet what was required of someone prepared to confront the KGB were steelier qualities: greater cynicism and less optimism; an appreciation of the presence of the irrational and cruel. Dropping that ‘sense of proportion’ might have been a useful guardrail against Stalin’s evils. An echo of that assessment came from Kim Philby, who wrote to Trevor-Roper (in a letter dated April 30, 1968) that his survival from his interrogation had been gained courtesy of the ‘ineffective’ White, who was ‘pretty nondescript besides such colleagues as Liddell, Hart, Blunt, Rothschild and Masterman’.

As Tom Bower points out, there were some sour grapes behind that observation, and he points out that none of the officers named ‘would have been minded to lead the charge against Philby’. He is right: Liddell was cerebral, but lacked confidence and guts; Hart was a very meek and mixed-up personality; Blunt’s reputation for scholarship and clear-thinking was obviously blasted after his exposure; Rothschild was a devious and vainglorious character, with dubious motivations; Masterman was surely equipped to enjoy a quiet life, skillfully organizing the XX Committee. Trevor-Roper acknowledged Philby’s grudge and poorly disguised motivations in a tribute to White in Christ Church Report, 1993, where he disparaged Philby’s letter. Yet Philby was overall on the mark: White blew his opportunity.

As I indicated in my response to Mr. Even-Shoshan, I think the comparison should lie elsewhere. In writing on what makes a good Intelligence Officer, in my piece from last December (https://coldspur.com/a-wintry-miscellany/ ), I wrote:

In conclusion, after reading the biography of J. L. Austin, I realized that it was a figure like him that MI5 (and MI6) desperately needed to coordinate intelligence about Soviet intentions and practice in all their aspects – Leninist and Stalinist doctrine, the Comintern and its successors, Moscow’s relationship with the CPGB, the role of spies, illegals and agents of influence, the use of propaganda and subversion. Austin’s capacity for hard work, his ability to learn, his excellent memory, his historical sense, his patience, his lack of sentimentality, and his synthetic abilities in interpretation all gave him an unmatched capability. Two heads of the CIA, Walter Bedell Smith and William Casey, were both highly impressed with Austin’s work, and tried to bring his disciplines to work in reforming the organization.

Thus Bedell Smith, for whom White had served in Germany at the end of the war, thought more highly of Austin. White had had an opportunity to bring his expertise to bear in the immediate post-war years, and to dedicate appropriate analysis to the warning signs. The intelligence concerning Blunt, Feabre, Honigmann, Smolka, Broda, Tudor-Hart, Nunn May, Philby (abetted by Gouzenko and Volkov), as well as Alexander Foote, and Ursula and Len Beurton, followed by the Fuchs case, should have formed a pattern. Yet, facing the unthinkable, he failed to grasp the nettle. He set about concentrating on cover-ups, saving his own career, helping to ensure the survival of MI5 by lying to his bosses, and then persuading Sillitoe in turn to lie to Attlee over the Fuchs business. Afterwards, he felt like resigning when severely rebuked by Sillitoe, yet was convinced by Liddell that he should soldier on, only then to betray Liddell in his quest for the top job. And then, later, when chief of MI6, he undermined his former service by encouraging rumours of Soviet penetration of MI5 – the ‘ELLI’ fiasco. It was a selfish and dishonourable end to his career.

So that is my conclusion about White: on the surface, a heartily good fellow who knew how to deal with Whitehall, but altogether too decent a chap to take on the monstrosities and wiles of Stalin. ‘The schoolmaster’, as Malcolm Muggeridge called him after hearing of his promotion to Director-General. True, he was not immediately responsible for the policies of Section B when he arrived in MI5. He soon had an opportunity to extend a fundamental influence, however, but he failed to do so. He was not comfortable speaking ‘truth to power’. He disbelieved the harsh truths from Krivitsky, but succumbed to the flattery and attention of Blunt. He showed some worldly wisdom, and was not without ingenuity himself, as his plot with the CIA demonstrates, but he quickly wove himself a tangled web which should have been impossible to escape. He did escape for a long time, however, and even received a bountiful biography, and accolades, which have positively enhanced his reputation. The crucial factor was that he was fortunate in that his political bosses were not very smart, either.

Postscript: The Lost Philby Chapters

As a result of another amiable email from a regular correspondent, I followed up a lead on the chapters of Philby’s autobiography that failed to be included in My Silent War. The writer drew my attention to a story published on-line by the BBC, at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-67456282. My informant went on to tell me that Philby’s widow had been trying to sell some of their possessions after the fall of the Soviet Union, yet, shortly before the auction was to take place, MI6 became rather nervous about what might be revealed, and persuaded the auction house to remove the more sensitive portions of the memoir. Money changed hands, and the censored material is now reportedly held in the MI6 vault.

From the photographs of the excerpts, I was able to determine that what was presented by the Spyscape Museum actually represented the extra two chapters that were published in The Private Life of Kim Philby, by Rufina Philby, assisted by Hayden Peake and Mikhail Lyubimov, published in 2000. They appear as ‘Autobiographical Reminiscences’ on pages 206 to 243: the first covers Philby’s early years, while the second starts with Philby’s arrival with his new bride in London in the spring of 1934, and describes his recruitment by Arnold Deutsch. So what might the withdrawn chapters have contained? It occurred to me that Philby’s time in Vienna was completely absent, and that he might well have written a chapter describing his experiences there – the revelation of which would have been very embarrassing for MI6.

I decided to contact Shari Kashani, Head of Collections and Curation at Spyscape. She was very helpful and appreciative. Portions of the two chapters had originally appeared in the Sunday Telegraph, in 1993: she very kindly sent me images of the extracts. But she (and Skyscape) did not even know that the two chapters had appeared in the Private Life book published in 2000! So we know that what Skyscape owns appears to correspond to what Rufina handed over. Yet, as I pointed out to her, it is odd that the memoir would jump from childhood reminiscences to London in 1934, without covering the tumultuous days in Vienna. I wrote to her:

I find it all intriguing, because Philby’s memoir (My Silent War) is judged to have been written with the KGB looking over his shoulder, and is very unreliable. One might think that Philby would perhaps have tried to correct some false impressions, but the second chapter (concerning his recruitment) is probably just as unreliable. For example, he starts off by writing about his return by train via Berlin and Paris, but E. H. Cookridge, who knew him well in Vienna, wrote in his memoir that Kim and Litzy returned to the UK on a motorcycle . . . The fact that he did not write about the controversial time in Vienna (that would have preceded this chapter) is also provocative.

Ms. Kashani replied:

Thank you so much for sharing that very interesting information. When we purchased the memoir, it was specified that the work was unpublished, hence we didn’t know of its inclusion in Rufina’s memoir. You are correct – the work comprises 48 typewritten pages, and then additional pages of edits. Nevertheless, we are thrilled to have the memoir and its document holder as part of our collection, and very happy to know that the public have access to Philby’s words in this 2000 compilation.

Finally, I informed her of the story of MI6’s intervention, and gently pointed out that Spyscape might have been misled over the exclusivity of the chapters the firm did buy (since they were unaware that they had been published in book form), and that it may also have purchased less than was originally described. She had confirmed to me that there were only 48 pages extant, which number matches that stated by Peake in his Introduction in the book. On the other hand, in an article in The New York Times of 1994 (‘Kim Philby and the Age of Paranoia’), Ron Rosenbaum described how he had been able to inspect the consignment of Philbyana received from Moscow when he visited Sotheby’s, and that among the papers he discovered the unfinished biography. “Five [sic!] chapters in manuscript pages whose publication the K.G.B. had apparently prohibited”, he wrote. This was apparently news that Spyscape did not want to hear, as she did not respond to my comments: her previously very affable communications ceased over two months ago. She and her bosses were presumably no longer ‘thrilled’. In a way, I was sorry to detect her chagrin, but I had hoped she might follow-up my lead more aggressively.

So it seems there exist two chapters as yet unpublished. Can anyone out there add anything else?

Late News: I have compiled Omnibus Editions of a) the demise of PROSPER, and b) recent bulletins on Kim Philby, that can both be inspected via the Reports and Articles page at https://coldspur.com/reviews/.

(Latest Commonplace entries can be seen here.)