Contents:

Introduction

Sources: Smolka in the UK

Sources: Smolka’s Personal File

Sources: The ‘Third Man’ Movie

Research Questions

Chapter One: 1930-1934 – Finding his Feet

Conclusion

Introduction

The status and allegiance of the influential Austrian Peter Smolka (who changed his name to ‘Smollett’ when he was naturalized in 1938: I shall refer to him throughout my postings as ‘Smolka’ – except when quoting other works directly – as that is the name he reverted to after he returned to Austria) are a matter of some controversy. An apparently tireless worker for the Soviet cause, his role as a Soviet agent has been denied by his son, yet Soviet archives clearly identify him as an NKVD operative with the cryptonym ‘ABO’. In this bulletin, I present the first results of a research project involving the inspection of source material (with special attention to a detailed analysis of the extensive files released by the National Archives in 2015) in an attempt to verify the period for which Smolka might have been active on the NKVD’s behalf, and to discover the interactions he had with British Intelligence. In this first report I survey and summarize the generic literature on Smolka, and present my analysis of his career up to the end of 1934, after a momentous year experienced by Smolka and his colleague Kim Philby, one not without controversy.

I divide Smolka’s career into six main chapters : i) his arrival in the UK in 1930, up to his visits to Vienna in 1934, and the months thereafter: ii) the years spent before the war, up to his supposed ‘recruitment’ to the NKVD by Philby in 1939 (or soon after); iii) his career during the war, highlighted by his prominence in the Ministry of Information; iv) his post-war activity in Vienna up to 1948, including his involvement with Graham Greene over the screenplay for the movie The Third Man, and what that relationship reveals about his early career; v) the renewed interest shown in him between 1949 and 1951, when, after the escape of Burgess and Maclean, documents incriminating Smolka were found in Burgess’s flat; and vi) the desultory investigation that followed, interleaved with one or two dramatic flourishes, culminating in Arthur Martin’s ‘interrogation’ of Smolka in October 1961. I organize this introduction by first describing the literature published before the release of the Kew material in 2015, next by analyzing what has been since issued that exploits those same files, and lastly by inspecting the considerable literature on Graham Greene and Smolka, which merits a category in its own right. I shall then use the Smolka Personal Files as a backdrop for interpreting what the highly contradictory third-party accounts report. In a bulletin to appear next month, I shall cover the last five chapters, including Smolka’s assimilation into, and acceptance by, leading establishment offices, his service as a Soviet propagandist during the war, followed by his return to Vienna as a correspondent for The Times, when he gained the attention of MI6 after it was reported that he had joined the Communist Party. Now that I have performed my preliminary investigation, I believe that the results are very dramatic, and that they will help clear up some earlier mysteries.

A reminder about my approach to archival documents: I do not take them at face value. I ask myself the following questions:

- Who is the author of the document?

- What did he or she know at the time?

- What was he or she trying to achieve in writing this item?

- What does the framework and incidental data of the document (modes of address, redacted information, unredacted information, references, handwritten annotations, missing information, etc. etc.) tell me about its context?

- Why was this particular document inserted into the archive?

- How does the information therein compare with other sources (e.g. memoirs)?

Similar questions have to be addressed to memoirs themselves.

Sources: Smolka in the UK

While long-standing government files occasionally refer to Smolka’s involvement with the Ministry of Information and with the BBC, the primary source material consists of the four files KV 2/4167-4170 representing Smolka’s MI5 Personal File 39680, which were released by the National Archives at Kew in 2015. They cover the period from when he arrived in the UK as an eighteen-year-old in 1930 up until early 1962, shortly after he left the UK for the last time, having undergone a very feeble interrogation by Arthur Martin. These files are thus the prime source for Smolka’s overall career: writers on intelligence matters who discussed Smolka before 2015 had to rely on snippets in general files, informal recollections and anecdotes, or (in one case) bootlegged extracts from official archives that were made available furtively. I point out that a supplemental ‘Y’ file – a highly secure Annex to his Personal File – was maintained by MI5, the contents of which are of course unavailable.

Smolka had started to come to the attention of authors in the 1980s, when documents relating to the wartime Ministry of Information were released. In Their Trade is Treachery (1981), Chapman Pincher made a brief reference to Smolka’s questionable role at the Ministry, and he pointed out that the debriefings of Anthony Blunt (a secret that must have been divulged to him) had confirmed that Smolka had been a Soviet agent. Anthony Glees, while also lacking access to such archival material, picked up the story and made a strong case about Smolka’s pernicious role in his 1987 book, Secrets of the Service. He made the confident assertion that ‘there is now overwhelming evidence to suggest that one of Bracken’s most trusted advisers, Peter Smolka-Smollett, was a Communist mole’. Yet, apart from the familiar tale of Smolka as a cagey propagandist for Stalin in the Ministry of Information, Glees did not provide any evidence that Smolka had actually been recruited by the NKVD at that time. He referred to the regular meetings that Smolka had at the Soviet Embassy, but those arrangements were in no way out of order, given Smolka’s position.

I suspect, however, that Glees was the first to publish Smolka’s detailed strategy for projecting the Soviet Union’s influence on British policy, although it is sometimes hard to follow Glees’s narrative and use of sources. He made much of the fact that Smolka was a close friend of Brendan Bracken (without explaining how that friendship occurred), and that he thereby conspired with him to oust Hugh Dalton as the head of the SOE. I find much questionable about this theory, however. Glees wrote a lot about ‘moles and agents’ within SOE, but few are identified, and it is not clear how they affected propaganda at a time when SOE was focussed primarily on sabotage and secondarily on intelligence-gathering. The overall conclusion, in the context of the timing of the Soviet Union’s entry into the war, of Smolka’s promotion, of the maturity into action of SOE, and of Dalton’s dismissal, does not make sense to me.

Another controversial contribution was W. J. West’s The Truth About Hollis (1989). While professing to have had no access to secret sources – or even knowingly to have spoken to any MI5 officer – West (no relation to Nigel West) had clearly been shown portions of Smolka’s Personal File, no doubt according to some manner of controlled leakage. For West was an overt member of the ‘Hollis is guilty’ school. West’s contribution is nevertheless very useful. Exploiting Foreign Office and BBC archives, he gives a very sensible analysis of Smolka’s ‘adoption’ by Rex Leeper, his collaboration with Guy Burgess, and his extensive propaganda work at the Ministry of Information. He even includes a two-page circular issued by Smolka in February 1943, titled Arguments to Counter the Ideological Fear of ‘Bolshevism’, which he sources to his own earlier 1985 work Orwell: The War Commentaries. It is an astonishingly mendacious piece, and should have raised a storm.

Further anecdotes surfaced in the next two decades, some from unreliable memoirs, others from Russian sources. Discoveries made by Oleg Gordievsky from Soviet archives were revealed in KGB: The Inside Story (1990) by Christopher Andrew and Gordievsky: they stated firmly that Smolka had been a Soviet agent, suggesting that he had been recruited some time before 1939 (the year in which Philby claimed to have engaged him). Through that assertion, without mentioning Philby, since they would not have been aware then of Philby’s claims, they reinforced the notion of Smolka’s longevity as an agent. They also recorded that, during the Slánský trial in Prague, in November 1952, Smolka was publicly denounced as an ‘imperialist agent’, characterizing this charge, perhaps a little naively, as ‘absurd’. A plan to kidnap Smolka from Austria, and to bring him to Moscow to answer allegations that ‘during the war he had recruited another Jew, Ivan Maisky, then Soviet Ambassador in London, to the British SIS’ was abandoned. Andrew and Gordievsky attribute these events to Stalin’s generic purge of Jews from the upper echelons, but Smolka’s escape from his Czech persecutors suggests that some intervention may have taken place.

It was in fact in Genrikh Borovik’s Philby Files (1994), where some dubious but henceforth much quoted reminiscences from Philby about his recruiting Smolka first surfaced, while Yuri Modin’s My Five Cambridge Friends (also 1994) offered one or two important insights. Modin provocatively asserted that Philby had met Smolka in Vienna in 1934 (without explaining anything about the circumstances), and he added that Smolka was an NKVD agent when he worked with Guy Burgess at the BBC in 1941 (but said nothing about the manner and timing of his recruitment). The Crown Jewels (1998), by Nigel West and Oleg Tsarev, exploited documents sent by the London-based spies to Moscow, and eventually inspected in the KGB vaults, in which Smolka occasionally appears. Yet the authors appeared to take at face value what Philby wrote in his reports, and how he later explained them, and they also displayed an inappropriately high degree of trust in what Moscow Centre declared about its relationship with Smolka.

In 2012, Gordon Corera offered up The Art of Betrayal, subtitled The Secret History of MI6, a rather hectic, journalistic approach that includes some valuable source material, but does not regard the dating of events as important. He introduced Smolka in the context of the Third Man saga, and described him, almost casually, as having passed information to the Soviet Union ‘from at least the start of the Second World War’. It is exclusively here that we learn that Philby returned to Vienna for a brief visit after the war, sourced to a tape-recording by Bruce Lockhart that the Imperial War Museum has withdrawn (Chapter 1, Note 19). Yet Corera danced around the circumstances of the friendship between Philby and Smolka, merely noting that the latter was ‘a friend of Litzi’s who had come to London’, the event undated. The author did not acknowledge any contribution by Smolka to the rescue work performed by Kim and Litzi in 1934. Thus Corera neither revealed nor corroborated relevant ‘secrets’ about Smolka and MI6 that had in fact been aired before, although he did re-present the startling insight first voiced by Andrew and Gordievsky concerning the KGB charges against Smolka during the Prague trials. He wrote that Anatoly Golitsyn, before he defected to the British, discovered in late 1954 in his predecessor’s file at the KGB Residency in Vienna an old letter from the head of the KGB British Department requesting ‘the kidnapping of Peter Smollett to answer charges that he had been working for MI6’.

The problem is that so many works show a cavalier approach to what has been written before. They either overlook previous assertions or disclosures, or accept them unquestioningly, but almost always fail to inspect them properly, to attempt to verify them, or to analyze in any depth the contradictions of multiple narratives that are crying out for resolution. For example, as late as 2015 Boris Volodarsky, in Stalin’s Agent (a book purportedly about Nikolai Orlov, but one rambling across many spheres) offered a wild summary on Smolka, with some vague and unattributed claims (‘Some say that Smolka got his job at the Ministry of Information through Brendan Bracken’), and several incorrect dates. Many of these works are similarly not accurately sourced, and, in general, one has to be very careful in determining who is echoing whom, and where the stories started. Anything that the habitual liar Kim Philby wrote should be treated very cautiously. As always, a close examination of chronology and geography is required to test many of the ‘facts’ that are presented by these authors.

For instance, the book by Andrew and Gordievsky, bolstered by the authority that the latter enjoyed by virtue of his inspection of KGB files, claimed that Smolka and his wife were trapped in Prague when Hitler visited it (after occupation, on March 19) in 1939, and that they thus had to seek refuge in the British Embassy. An endnote indicates that this fact derived from W. J. West’s volume. West had in fact dug out a memorandum, dated November 1938, from Smolka to Rex Leeper, laying out his plans to visit Prague, Warsaw, Budapest, Bucharest and Berne. Indeed the assertion about his escape from Prague does appear in West’s text, and he claimed that Smolka got away alongside one Otto Strassner ‘and other anti-Nazi leaders’, after which he and his wife returned immediately to London – which would suggest that the visits to other capitals were abandoned. Yet West provided no source for his story. The chronology in the Smolka files (which were not officially available in 1989, when West’s book was published) leaves a puzzling gap between November 1938 and September 1939, although serial no. 116a in KV 2/4168 states that, in April 1939, Smolka went to Switzerland with letters of recommendation from Rex Leeper (his sponsor at the Ministry of Information). No embarkation or disembarkation records for either of these purported journeys have been made available. Moreover, the Smolkas’ second son, Timothy, was born on October 12, 1938, so it seems to me unlikely that Lotty, even if it had made political sense for her to accompany her husband to Prague, would have abandoned her sons at that critical time. In addition, Smolka was a UK subject by then, so should have been in no danger.

Yet confirmations of Smolka’s presence in Prague are offered by Purvis and Hulbert. In the BBC archives, they uncovered a memorandum from George Barnes, the Assistant-Director of Talks, to Guy Burgess, notifying him that Smolka had been pencilled in for a talk on March 14, 1941, since he had been in Prague when the Germans entered the Czech capital on March 14, 1939. The duo even discovered a sound recording of the programme, and heard Smolka vividly describe what happened, when reporting for the Exchange Telegraph news agency – which must be one of the most genuine artifacts in this messy tale. They add that the Foreign Office indeed had helped to get Smolka out of Prague. Lotty is not mentioned in this scenario, but Smolka presumably quickly returned from the UK to mainland Europe, but for an abbreviated tour solely to Switzerland. But why was the Berne expedition, but none of the Prague incident, recorded in his Personal File?

Somewhere, behind all this, a truth might be found. It would appear that West was working from a different source, since he appears not to be familiar with those particular BBC exchanges. Maybe a reappraisal of the sound recording, or some delving into the activities of Otto Strassner, might reveal more, but the whole sequence of events is typical of the muddle that surrounds these archival remnants.

Sources: Smolka’s Personal File

The contents of the files at Kew are very rich in many ways, and merit close attention, since they display many anomalies that have not been picked up by any commentators, so far as I can judge. There exists also a Home Office file on Smolka’s naturalization request (HO 405/47416) – superficially not very significant, apart from the fact that two pages of extracts (405/47416/1) are closed, and not to be opened until January 1, 2034. The journalist Mark Hollingsworth (whose book I reviewed in October), had submitted a Freedom of Information request to have this item released immediately. His first appeal was rejected, quite absurdly, on the grounds that an MI5 officer was therein identified. Hollingsworth therefore took the process up to a higher level, but his request was again rejected. The logic for withholding details of a naturalization request from eight-five years ago by someone now accepted as having been a Soviet agent is indefensible: the decision represents sheer bureaucratic obtuseness, and merely draws attention to an area of embarrassment. Of course, there must be something to hide, and matters of institutional pride and shame are at stake. The fact that January 1934 happens to be the centenary of Philby’s presence in Vienna, when he was, according to some accounts, in the company of Smolka, might suggest what matters the closed papers address.

My analysis of the files, in which I integrate the intelligence found there with the surrounding memoirs and histories, will be prominent in the sections that follow. I here summarize recent publications by those who have, to some degree, studied them. As far as independent scrutiny in the recent, post-2015 literature is concerned, I believe the only serious analysis of the KV material has been undertaken by Stewart Purvis and Jeff Hulbert, in their 2016 book on Guy Burgess The Spy Who Knew Everyone. The authors have also brought fresh light on Smolka by their discovery of records in the BBC Archives (many of which were actually first revealed by W. J. West), although these items are remarkable more for their curiosity value than for anything they shed on Smolka’s allegiances, and his ability to outwit his hosts. Purvis and Hulbert also refer to some vital memoirs and histories that help flesh out the story, although, probably because their emphasis is on showing how Smolka contributed to Burgess’s traitorousness, they neglect to discuss some of the anomalies in the record, and avoid any inspection of the Graham Greene connection that helps illuminate the details of Smolka’s career and time-line.

Richard Davenport-Hines, in Enemies Within (2016), also gives a respectable but superficial summary of the Smolka files. He has appeared only to skim them: on the other hand, his analysis is enhanced by his bringing to the discussion some worldly and enlightening insights from contemporary political events. He offers some trenchant (and contentious) judgments, but his canvas is so broad that many of the paradoxes and subtleties of Smolka’s career have eluded him. At least he provides detailed references, and he does provide an original perspective on the Graham Greene connection. Helen Fry misses an opportunity to shed light on Smolka in a very confusing and muddled paragraph in her 2021 book, Spymaster, her profile of the MI6 head-of-station in 1934 in Vienna, Thomas Kendrick.

Mark Hollingsworth’s Agents of Influence (2023) would seem to be the first book that attempts to integrate the available archival material from Kew with the rich seam of narratives on the Third Man extravaganzas (see below). The author offers a useful and colourful synopsis of Smolka’s career. Unfortunately, Hollingsworth undermines his story by presenting Smolka as a prime example of an ‘agent of influence’, rather than a confirmed spy. While it is true that he exerted influence as a propagandist, such a classification understates his more serious role. Hollingsworth cites Corera and Gordievsky in support of his thesis, yet Corera himself reported that Smolka handed over information to the Soviets, and Gordievsky confidently declared that Smolka was a spy. That knowledge is now clear from the reports of information provably originating from Smolka being found in Guy Burgess’s effects after the latter disappeared, a fact that Hollingsworth acknowledges. And if Smolka passed on confidential information to Burgess, he certainly would have done the same to Maisky, the Soviet ambassador. In addition, Hollingsworth, while echoing the dramatic story that Smolka worked alongside Kim and Litzy in the sewers in 1934 (which surely demands closer inspection), nevertheless presents Smolka as being largely influenced by Philby, contrary to the evidence. Hollingsworth also trusts Philby’s account that it was he who recruited Smolka to the NKVD, thus implicitly suggesting that Smolka’s activities were all very innocent up until then.

Sources: ‘The Third Man’ Movie

The fourth chapter primarily concerns Graham Greene, and his visit to Vienna in 1948 to perform research for his screenplay for the film to be directed by Carol Reed, The Third Man. There Greene met Smolka (who had returned to Vienna after the war as a correspondent for the ‘Times’, and did not relinquish that position until May 1949), and the overall evidence points to the fact that Smolka contributed in some way to the screenplay, thereby betraying some of his activities from the 1930s, and probably intimating darker arrangements. The literature in this domain is quite rich. As always, however, the accounts are not consistent, but they are frequently very provocative.

Graham Greene: Greene’s account of the adventure in his memoir Ways of Escape (1980) is full of deceit, as would be revealed years after when the archives of the London Films Production were inspected, and Elizabeth Montagu in 1997 started to disclose to researchers sections of her unpublished memoir, which eventually saw the light of day in 2003. Greene makes no mention of his stint at the Ministry of Information in the summer of 1940, where he might have encountered Smolka. He does not disclose how Alexander Korda (the producer of the movie, and an MI6 asset) arranged his itinerary in 1948, and he offers specious arguments for his spending a week in Prague after leaving Vienna, when he was supposed to be in Rome. He never mentions Montagu (who worked for Korda, and apparently arranged his meetings in Vienna): nor does he record his contacts with Smolka, or the controversies that surrounded the latter’s contract with Korda’s film company. He describes an unlikely evening with Elizabeth Bowen, which is nevertheless verifiable from other sources (including Bowen herself), and thus not simply a mask for an outing with Elizabeth Montagu. The overall account is, however, a typical Greenian charade, and serves only to demonstrate that he wished to conceal the nature of the events.

Michael Shelden: Shelden was the first (unauthorized) biographer of Greene, his 1994 book being published in the UK with the suffix The Man Within and in the USA as The Enemy Within. While much private material was therefore withheld from him, Shelden struggled mightily with the mass of anecdotes he was able to collect, and strained to impart a coherent explanation of what was happening. Significantly, he interviewed Lotty Smolka and her sons, as well as Elizabeth Montagu, who must have shown him some of her then unpublished memoir. In that way, a probably more accurate account of Greene’s activity in Vienna comes out, with his being introduced to Smolka by Montagu, who arranged Greene’s meetings with journalists and businessmen. Thus Shelden attributes to Smolka a role as the source of the anecdotes about the diluted penicillin, the sewers, and the bizarre sharing of facilities by the Four Occupying Powers, since Smolka had apparently written some short stories on these phenomena, which he passed over to Greene. This leads into a startling direct reference to Smolka’s subversive activity in Vienna in 1934, something that Lotty Smolka confirmed to him, yet Shelden sees nothing noteworthy in this extraordinary revelation. He also refers to a contract that Smolka signed with Korda that expressly proscribed him from seeking any other monies or publicity over ‘The Third Man’, and relays Elizabeth Montagu’s disgust and puzzlement over this rather clandestine and suspicious agreement.

While Shelden also explains that Korda was working part-time for MI6 (for such services he had in fact been knighted in 1942 on Churchill’s recommendation), he cannot contrive any coherent explanation for what schemes might have been going on at the time. He does indeed claim that the 1948 trip was cover for MI6 investigations in what was going on (‘keeping an eye on the volatile political situations in both countries’), but MI6 had very capable representatives at the time, especially in Austria, where the distinguished George Kennedy Young was head of station. It sounds like a very lame explanation. He very oddly suggests that Greene was possibly working under private instructions from Philby himself, who was ‘still the blue-eyed boy of the service’ (hardly an accurate representation at this time). He judges it a coincidence that Montagu would lead Greene straight to Smolka, although ‘he was the one man in Vienna who could discuss Philby’s past in detail and who could do it in English’. There is a lot of hidden menace in that suggestion of the Smolka-Philby intimacy, but it remains unexplored: why Smolka would volunteer information about his fellow-agent (a suspected spy) to a former MI6 officer is left unexplained. Shelden is clearly out of his depth.

Norman Sherry: Graham Greene selected Sherry as his authorized biographer, and his massive and rather self-indulgent study, The Life of Graham Greene, appeared in three parts, with Volume 2 (1939-1955) – which is the critical item for my analysis – being published in 1994. Sherry had eventually fallen into disfavour with both Greene (who died in 1991) and his family, since he inevitably presented some less illustrious aspects of Greene’s career and personality. Sherry does reflect many incidents of Greene’s employment with MI6, but his preference is for literary analysis, and he is not tuned to the multilayered character of intelligence and counter-intelligence manœuvres. He thus struggles to interpret conflicting information, and leaves several paradoxes unanswered.

For example, his chronology for Greene’s sojourn in Vienna is simply careless. He has Greene ‘reluctantly’ going to Vienna in February 1948: Greene wanted to get his preliminary research for the plot of his screenplay over with quickly, so that he could soon rendezvous with his lover, Catherine Walston, in Rome. Sherry makes an incongruous observation: “He thought of leaving Vienna by train because it would have been easier to reach Italy that way, but for the sake of adventure, he decided to fly.” My research indeed shows that there were no commercial flights between Vienna and Rome at that time: voyagers had to travel by train, but neither were there flights between Prague and Rome. Greene therefore took a plane to Prague, since he apparently did not want to miss an exciting story in the Czech capital. Revolution was breaking out. So much for urgently wanting to be re-united with Catherine: he delayed his assignation unduly.

Sherry does report that Greene spent six or more hours with Smolka on the night of February 17 (which would suggest some very intense discussions), and he next mentions the Elizabeth Bowen cocktail party on February 21. Greene had written to Catherine on February 18, reminding her that he had seen her only a week beforehand (which, if true, would place his departure from England on about February 12), and Greene then stated that he left Vienna on February 23 for Prague, where he stayed for a week. On February 27, a paragraph about him appeared in the News Chronicle. Lastly, Sherry informs us that Greene then met Catherine in Rome in late February, where he started writing his screenplay. Yet, according to the chronology, Greene could not have left Prague until early March. Someone is obviously lying, and Sherry is not shrewd enough to suspect that Greene may have had more official business in Prague.

Greene’s return to Vienna in June, accompanied by Carol Reed, is also covered. Sherry states that the pair went to the Soviet zone, that Greene spent time in the sewers with Elizabeth Montagu and the sewer police, and that on his penultimate day there, the famous Beauclerk told him the story about the penicillin racket. Only now does Sherry concede that Smolka may have been the source of such anecdotes, adding that Greene also visited the Soviet zone with Smolka, and that they spent several nights (evenings?) together. Perhaps uncertain where he stands, Sherry cites Montagu as the authority for the stories of penicillin, and credits Smolka’s short stories as a more likely source than Beauclerk. Whether such tales were ever written must remain a mystery.

W.J. West: W. J. West returned to the fray in his 1997 book The Quest for Graham Greene. For some reason he is very dismissive of Shelden’s work, and largely ignores Sherry’s, especially when it comes to Smolka. Preferring to believe Greene’s own account, as revealed in the author’s papers at Boston College, he recognizes the contract that Smolka signed, but describes it as a possible ‘cover for some other less avowable reason for payment’. (That is a tantalizing observation, however, that may have a lot of merit.) Yet West seems rather naïve about the context: he describes Smolka simply as a ‘freelance journalist’. He suggests that the papers at Boston College indicate that a priest had apparently written to Greene in 1950, inquiring about the source of the penicillin story, and Greene had replied that he acquired it from the ‘chief of police’ (actually the MI6 officer), Beauclerk. West accepts this at face value, ignoring the evidence that Montagu had provided. He does suggest that Greene already knew about Philby’s adventures in the sewers, without explaining where he gained this insight. It is another very uneven compilation that could have benefitted from some stricter discipline.

Charles Drazin: Another author who interviewed Montagu was Charles Drazin, a London-based author and film-historian, who presented a timeline that conflicted with hers in his 1999 book In Search of the Third Man. Here he has Montagu being charged with her mission from Korda in December 1947 (as opposed to her claim of ‘early February’), without any overt explanation as to whether her presence was coincidental, or part of a deeper plot to set the stage. Yet Drazin also dug out a letter of January 5, 1948 from Korda to Greene, instructing him to go to Vienna for three weeks and then to Rome for five weeks for purposes of research work. The proximity of the two events suggests that they occurred in tandem.

Drazin was able to exploit the archives of London Films Productions, and thus presents some original documents. He largely follows the Montagu line about her introduction of Smolka to Greene, and the source of the anecdotes, indicating that Montagu learned about Smolka’s stories before Greene arrived. He adds the fascinating detail that Smolka asked Greene’s literary agents, Pearn, Pollinger & Higham, to handle negotiations of the contract for him, and that he seemed happy with the whole process. Drazin uncovered a signed contract returned by Smolka on September 21, 1948. It all suggests a harmonious and amicable relationship between the couple. He also records that Montagu told him that she suspected duplicity in what Greene was up to –maybe a disingenuous observation on her part.

Elizabeth Montagu: The part-time OSS and MI6 asset Elizabeth Montagu clearly played a significant role in the affairs in Vienna, but her own evidence is riddled with controversy and contradictions. Montagu, the daughter of Lord John Montagu of Beaulieu, was a member of the Mechanised Transport Corps in France in 1940, and she became stranded when she declined an opportunity to sail back to the UK. Hunted by the Gestapo, she managed to escape to Switzerland, and eventually worked for Alan Dulles of the OSS. After the war she was employed by Sir Alexander Korda, who sent her on a mission to Eastern Europe early in 1948. She had been interviewed by Shelden (and others) in 1993, revealing to him portions of her then unpublished memoir, which revealed much about the bizarre encounters between Greene and Smolka in Vienna in February 1948, and her disdain for the contract that Smolka eventually signed. Yet, when the memoir Honourable Rebel appeared in 2003, a year after her death, the text was much more cautious and restrained. While she described introducing Greene to Smolka, and the fact that Smolka handed over to Greene a manuscript, hoping to get his stories published, she even suggested that Greene might have acquired the penicillin story from other sources in Vienna at the time.

Yet far more serious questions have to be asked about the accuracy of her account. The chronology does not make sense: it is physically impossible. First, she recalls that Korda summoned her to his office to outline her mission in Eastern Europe ‘early in February’. She then describes making an emergency exit from Prague, via a US army plane, to Vienna, just after the February revolution, and then spending a few days in Vienna before receiving a telegram from Korda that Graham Greene would soon be on his way, and that he would need her help. Yet Greene arrived in Vienna, verifiably, on February 12, and left – for Prague, of all places, when he was supposed to be going to Rome! – on February 23. And the revolution in Prague took place on February 21, when Gottwald, on Stalin’s orders, seized power. Montagu’s interviews in Prague must either have been a fantasy, or have occurred after her time in Vienna. It seems to me that she must have been complicit in the whole escapade, was encouraged by MI6 to conceal her tracks after her oral revelations, and then left a deceptive paper-trail in the published memoir, not to be released until after her death. I shall explore this remarkable distortion of the truth in next month’s segment, after I have tried to cross-check dates and sources more deeply, but I suspect that the accounts may be irreconcilable.

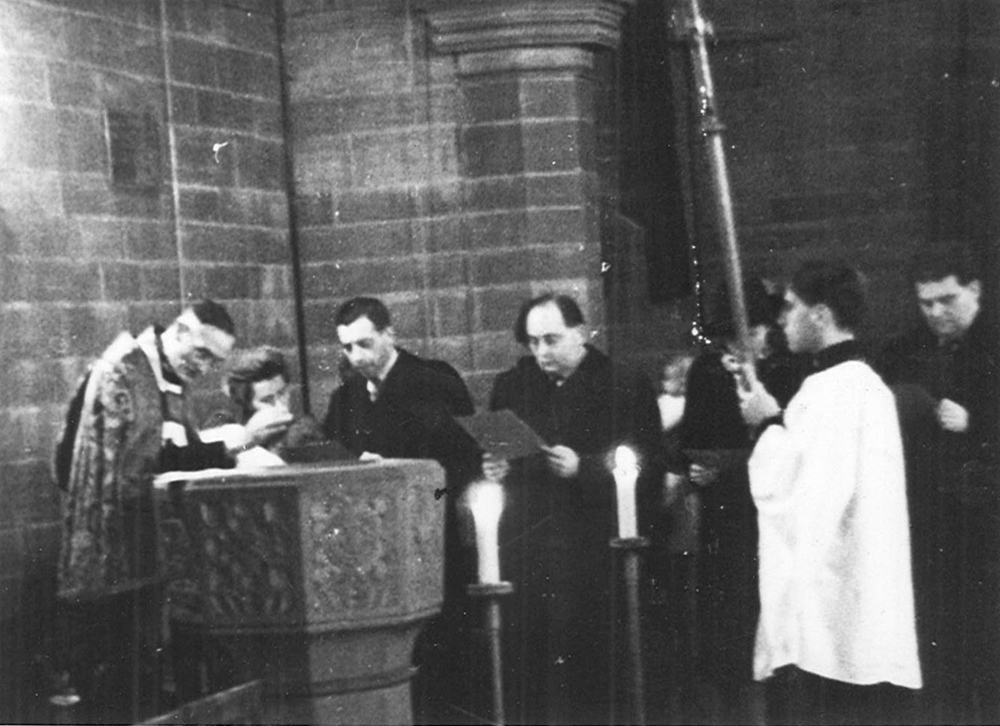

Peter Foges: An astonishing contribution to the saga appeared in 2016, in the relatively obscure Lapham’s Quarterly – and then only in an on-line segment, visible at https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/my-spy . (I have all fifteen years of Lapham’s Quarterly, a fascinating thematic collection of writings and art, in a pile in my library extension.) It was written by one Peter Foges, a film and television producer, who had been in the enigmatic situation of having Smolka, atheist and Jew, as a godparent. A photograph of this remarkable ceremony, held at Liverpool Cathedral in 1944, appears in the article (see below). Peter Foges’s father had known Smolka in Vienna, and Foges fils informs us that Smolka met Kim Philby through Litzy, who was a good friend of his. Moreover, he states that the three of them worked in the sewers together in 1934, and then Smolka followed them to London. I believe that, while hints have been made about Smolka’s presence in Vienna at this time, this is the first occurrence of any claim that Smolka and Philby had been communist collaborators, and the assertion has monumental implications, into which I shall delve later in this bulletin.

The rest of Foges’s account is error-strewn and woolly. He makes unattributed claims about Smolka’s recruitment by the Soviets (Maly?), and he seems to be unaware of Smolka’s previous time in the UK. He gets dates wrong, and echoes the relationship with Bracken (‘Bracken took a shine to Smolka and fell for his flattery’) without providing a source. He also makes the astonishing claim that Bracken himself ‘dragooned’ Smolka into helping write the script for The Third Man, and that Smolka was even flown in specially for a meeting with Korda and Bracken to plan that the movie take place in Vienna, so that Korda’s wealth locked up there could be exploited. Thus the overall tone of the piece is a bit shrill and questionable, while the first-hand exposure to Smolka that Foges père experienced in Vienna has the ring of truth.

Jean-Luc Fromenthal: An unlikely contribution to the debate crops up with The Prague Coup, a graphic novel written by Jean-Luc Fromenthal, and illustrated (sometimes very salaciously) by Miles Hyman, which appeared in 2018. The nuggets to be derived do not originate in the story itself, but in the Afterwords. Fromenthal echoes the assertion that Korda wanted to set the film in Vienna since he owned blocked funds in an Austrian subsidiary, Wien-Film, but he also suggests that Greene was actually on a mission to uncover evidence that there was a dangerous mole within MI6 – namely Kim Philby – and that Greene was dispatched to uncover Philby’s tracks. In this context, Smolka’s previous acquaintance with Philby is very poignant, and Fromenthal makes the provocative claim that the pair had met in London, in 1933, i.e. before Philby ventured to Vienna, and that it was Smolka who introduced Kim to Litzy (although the author is incorrect on his dating of Philby’s journey). He boldly declares that Smolka had been an agent of the NKVD, already known as ABO, as far back as 1933. Sadly, Fromenthal does not link any of his assertions to the fascinating Bibliography he offers at the end of the book, so it is impossible to trace these references.

What could also be vital evidence in support of Greene’s mission on behalf of MI6 is the role of one Colonel John Codrington. Fromenthal describes him as ‘a former agent of Claud [sic] Dansey’ (the vice-director of MI6), and he presents his role at the heart of Korda’s organization ‘to facilitate the movement of London Films personnel abroad, during an era in which the British government enforced heavy restrictions in that respect’. Codrington was thus able to make all the arrangements for Greene’s trip to Vienna – and to Prague, the latter excursion being described by Fromenthal as ‘an unforeseen (and to this day unexplained) extension to the journey’. Fromenthal distrusts what Greene said about Beauclerk, and attributes to Smolka the contributions on the penicillin and sewer material.

Thomas Riegeler: Lastly, a prominent article about this whole exercise was written by Dr. Thomas Riegeler in 2020, in the Journal of Austrian-American Studies. Titled The Spy Story behind The Third Man, it trawls widely, and occasionally in depth, through the literature concerning the movie. I learned about several items that had escaped my attention, including the Austrian periodical, The Journal for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies, which devoted a special issue (Volume 12, no.2, [2018]) to ‘The Third Man’, as well as the works by Elizabeth Montagu, and Jean-Luc Fromenthal and Miles Hyman, described above in this report. Riegeler also enjoyed conversations with Smolka’s widow, and their children. (I applied via the Journal’s website to purchase a copy of that important issue, but I have received no reply from the institution.)

Riegeler sets himself an ambitious agenda, describing the role of his article as follows: “By drawing upon archival material as well as secondary literature, this article explores this other history of The Third Man and puts the film in the context of postwar Austria, and highlights how real-life events and personalities inspired its story”. Yet Riegeler unfortunately appears to practice no identifiable methodology, and is very ingenuous. He treats all evidence and testimony as of equal value, and fails to investigate where and why conflicting accounts of the events surface. This defect is especially apparent when he reproduces the statements of Smolka’s son Timothy. These claims fly in the face of what others assert about his father’s activities and loyalties, and Riegeler does not question how objective or insightful Timothy might have been when talking to him.

For example, he weakly characterizes Smolka as ‘a possible Soviet spy’, appearing to trust what Timothy, who downplayed his father’s involvement, told him. Timothy claimed that Smolka père had never been a member of the Communist Party, and never a Soviet agent. Riegeler reports that Timothy stated that his brother Peter had discovered documents in Moscow that Smolka had been judged unsuitable as a spy, as he was ‘far too attached to his family’ – all quite absurd, and flying in the face of what Riegeler himself writes elsewhere, when he cites Andrew and Mitrokhin. Likewise, the other son, Peter, minimized his father’s role in supplying anecdotes about the penicillin scam, ‘as his father never spoke about it’. Elsewhere, Riegeler is haphazard and wrong about dates (for instance when discussing the ‘divorce’, and Litzy’s departure for Berlin, as well as Montagu’s activities in Switzerland). He bizarrely describes the first sacrifice that Philby made was ‘to divorce Litzy’. While Hollingsworth states that the Third Man’s Harry Lime was based partly on Smolka, Riegeler asserts that the inspiration for him was Philby himself.

Additional Material: As a coda, I present two important contributions from MI6 sources. The first is a valuable observation on George Kennedy Young, who was head of the MI6 station in Vienna when Greene arrived. He was a Cold War hawk who constantly criticized Western passivity in the face of Communist aggression. In 1984, he published Subversion and the British Riposte, which described his frustrations. He ran agents, defectors persuaded to stay in place for a while, no doubt, and wrote (p 10) that ‘by the autumn of 1947 the Soviet intention to bring Jugoslavia and Czechoslovakia to heel had become known through defectors’. In a 2020 tribute to Young (see https://engelsbergideas.com/portraits/george-kennedy-young-banker-writer-soldier-spy/) , Rory Cormac wrote that in the autumn of 1947 Young ‘had warned London of the threat of a communist takeover in Prague’. The decision to send Greene to Prague must be viewed in the context of this advice.

The second comes from the writer Jeremy Duns, who has made his writing on intelligence matters available at www.jeremy-duns.com . After the war, the journalist Antony Terry (who had performed very creditably during the war in various roles, but had been incarcerated by the Germans) was recruited by Ian Fleming’s ‘Mercury’ network, and posted to Vienna to work for MI6, while also being employed as a correspondent for the Sunday Times. Duns relies on the reminiscences of Terry’s wife, Rachel, for some of his accounts of Smolka, whom they encountered there. Terry took over some of Kennedy Young’s agents, and Duns writes: “Also reporting from Vienna at this time was a Daily Express correspondent, Peter Smollett, who was not all he seemed.” He continues:

After the war, Smolka returned to Vienna as a correspondent, carrying out much the same job for Soviet intelligence as Terry was for M.I.6. Smolka was a familiar face in the British press pack, but Rachel Terry soon began to distrust him. “In November (1947) Picture Post wanted an article on a foreign correspondent’s life in an Occupied city, and Peter Smolka proposed this to my husband as something in his gift. Smolka had the permits necessary to go to such places as Klosterneuburg, impossible to get from the Russians except on an official level. He also invited us and the photographer, the wife of the editor of Picture Post, to dine at the British Officers’ Club in Palais Kinsky with a woman Russian colonel, whose picture duly appeared with us all in the magazine. This was something so unheard-of that even I could see something odd in it. It could only have occurred with official Soviet approval, and to get permission for foreign publicity of that kind proved intimate and high-level contacts.”

Rachel Terry wrote this in 1984, and even then was being a little coy: the ‘woman Russian colonel’ was in fact Emma Woolf, a senior Soviet intelligence officer.

Duns assumes that this information would have been passed back to Young, but he notes that the British did nothing at that time, despite Smolka’s obvious links to Soviet intelligence. His article cannot be relied on absolutely: his chronology is erratic, and, like many, he has been taken in by KGB files concerning Smolka’s recruitment by Philby – a subject that I shall take up next month. Yet he revealed a very useful source.

I discovered the published source for these anecdotes. In the December 1984 issue of Encounter magazine, the thriller writer Sarah Gainham (the pseudonym of Rachel Terry, then Ames, née Stainer) submitted a long letter titled ‘Smolka “the Spy”’, which, while casting doubt on the reliability of the claim that Smolka had been a Soviet agent, did describe some aspects of his very unusual behaviour when she became acquainted with him in Vienna after the war. I have acquired a copy of the Encounter issue in question, and I shall report fully in next month’s coldspur.

Research Questions

While the overriding questions: ‘When was Smolka recruited as a Soviet agent?’; and ‘What was his relationship with British Intelligence?’ have driven my research, as I made my first pass through all the material described above, I compiled a list of subsidiary questions, as follows:

- Why was Smolka so rapidly approved for naturalization (in contrast to such as Honigmann)?

- Why did the authorities ignore the implications of his visits to the Soviet Union and his propagandist book?

- Why did MI5 and MI6 show so little interest in Smolka’s travel in 1933, and misrepresent the facts later?

- Did Smolka truly assist Philby in the sewers of Vienna in 1934?

- Why was Smolka’s presence in Vienna not noticed or recorded by MI6?

- Why did Smolka declare that he did not meet Philby until late in 1934?

- If he did indeed meet Philby only then, why did they so quickly agree to set up a news agency together?

- Why was news of Philby’s open collaboration with Smolka not received with alarm by MI5?

- Why did Smolka rise so quickly in government circles, leading to his recruitment by the Foreign Office, and eventually the O.B.E.?

- In what manner did Brendan Bracken become convinced of Smolka’s value?

- Why were the objections of the MI5 ignored, and why was Smolka’s case deemed ‘difficult’?

- Why were the suspicious of leakage from the MoI in 1940, described by Beaumont-Nesbit, ignored?

- Why did Rex Leeper, abetted by Vansittart and Peak, support him so actively, ignoring the fact that he surrounded himself with Germans and Austrians at his news agency?

- Was it really Moura Budberg who enabled Smolka to be recruited by the MoI?

- Why did Vivian of MI6 minimize his importance and influence?

- Why did Brooman-White of MI5 trust Philby’s opinion of Smolka in 1942?

- Who actually first made contact with Smolka in Vienna in 1948?

- Why did Smolka accept such a one-sided contract?

- Why did Arthur Martin give him such an inept interrogation in 1961?

- Why were the contradictions in his account not picked up?

- How did Smolka avoid the Czech show-trials?

- How, when he was apparently at death’s door, did Smolka manage to survive another twenty years?

- Why were suggestions made that Smolka’s visit to Czechoslovakia in 1948 might have been made on secret intelligence business?

- Why did MI5 think it might be able to persuade Smolka to ‘defect’ to the British?

- Why are so many of Smolka’s activities omitted from his PFs?

- When did MI6/MI5 become convinced that Smolka was a Soviet agent?

- Why do critics believe Philby’s claim that he recruited Smolka as an NKVD agent in 1939 as ABO?

- Why did Graham Greene and Elizabeth Montagu lie about the details of their itinerary in February 1948?

- Why did Greene travel to Prague after Vienna, when he was supposed to be in Rome?

- What was the role of George Kennedy Young (head of MI6 station in Vienna) at the time of the Greene-Smolka meetings?

(The relevance of several of these may not yet be apparent to the reader, as they derive from a close study of Smolka’s Personal File.)

I thus turn to a detailed analysis of the story of Smolka’s adventure with the United Kingdom, starting in 1930.

Chapter 1: 1930-1934 – Finding his Feet

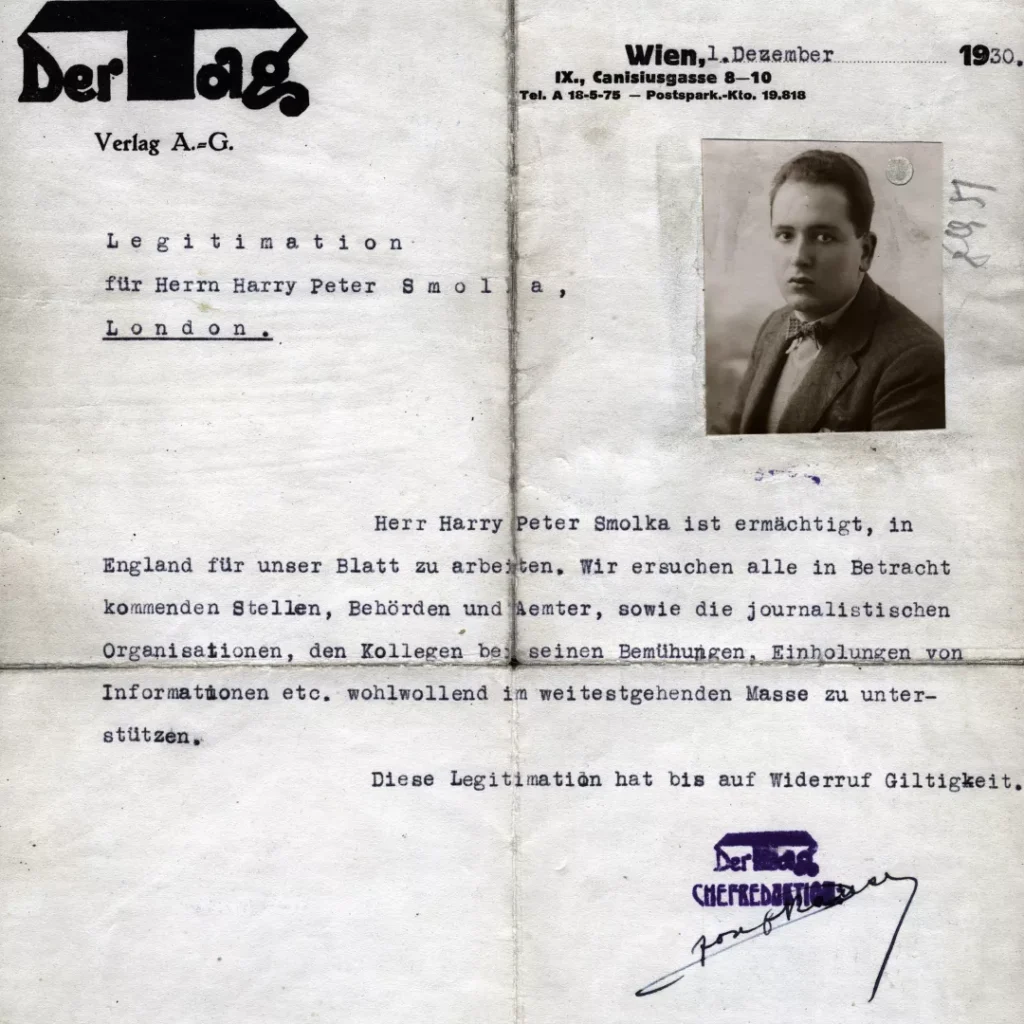

A significant fact about Smolka’s arrival at Dover on September 29, 1930 is that he was only twelve days beyond his eighteenth birthday. This was an early age for anyone to start engaging in nefarious activities. Yet his presence was quickly noted by MI5, who received a report in November that Smolka had arrived in Marseilles from Barcelona on August 18, that he had immediately been expelled by the French authorities, on August 20, for taking photographs at the port of Marseilles, and that he was suspected of being an Italian spy. Where he spent the intervening weeks is not clear, but he also came to the notice of the Metropolitan Police when his presence at a meeting of the ‘Friends of India’ society in Trafalgar Square was noticed on November 15. (An MI5 report states that that society ‘is described by I.P.I. as a Socialistic society composed mainly of Quaker cranks and Ghandi [sic, should be ‘Gandhi’] worshippers’.)

Smolka was actually interrogated after this event, and Scotland Yard informed B1b in MI5 of the outcome. Moreover, Smolka misleadingly admitted that he had been detained by the French police after attending a meeting. When the French authorities were consulted, they provided the true story, and added that Smolka had given his occupation as a journalist working for Die Zeitschrift der Neuen Jugend. Smolka produced evidence for the Metropolitan Police that he was attending a course at the London School of Economics, ‘taking a general course as a scholarship student of the Austrian government’. Whether the officials in Vienna knew or approved of their student’s wayward travel and offenses is not stated, but no indication is given that MI5 followed up with the Austrian Embassy to verify Smolka’s claims.

Nevertheless, MI5 increased its surveillance of Smolka, watching his movements, and also applying for a warrant to have his mail opened. They thus learned that he was keen on taking photographs of people in straitened circumstances, that he showed communist sympathies, and that his future bride, Lotty, wrote to him congratulating him on learning Russian. He was successful in getting some of his reports accepted by Austrian periodicals. MI5 also started keeping tabs on some of his friends and associates. His permit required him to leave the country within six months, so he departed from Dover for Ostend on March 25, 1931. MI5 knew from his recent correspondence that his destination was Vienna.

Smolka was away for a couple of years, arriving in Folkestone from Boulogne on May 6, 1933. He was accompanied by his wife, and stated that he was now a journalist for the Neue Freie Presse of Vienna. If Smolka had been recruited by the NKVD, early 1933 would have been the obvious time, as the organization was intensifying its infiltration of the Western democracies. Arnold Deutsch had received his training in Moscow in January. The Orlovs had returned to Vienna in March, and, after a short spell in prison, left for Prague and Berlin, and arrived in Geneva in September. In March, Rudolf Katz was sent by Moscow to join Willi Műnzenberg in Paris. He arrived in the UK soon afterwards. In April, Robert Kuczynski fled to Czechoslovakia, then to Geneva, and arrived in the UK at the end of the month. Edith Suschitzky was arrested in Vienna in May, and married Tudor-Hart in August, thereby gaining her British passport. That same month, Deutsch, back in Vienna, recruited the couple as STRELA. In July, Klaus Fuchs was dispatched from Germany to Paris. John Cairncross spent the summer in Vienna. Ignaty Reif was sent to Britain in August.

And it is now that the record starts to take a strange turn. On August 24, Smolka sent a letter to the Under-Secretary of State at the Home office, in which he referred to a recent conversation he had with a Mr. Hoare of that department. He requested that he and his wife be allowed to stay in the country further, given his new role as special correspondent for the Neue Frei Presse to the Worlds [sic] Economic Conference, indicating that they were economically self-sufficient. On September 6, a Mr E. N. Cooper replied to say that the Secretary of State would ‘raise no objection’ to the prolongment of the couple’s stay in the United Kingdom.

Was something being fixed behind the scenes? The statement that no objection would be raised strongly suggests that others might do so. And who was the Mr Hoare with whom Smolka had spoken? Could it be the future Home Secretary Samuel Hoare, who took up that office in 1937? Hoare clearly did not work for the Home Office at that time, since he was Secretary of State for India, but he spoke Russian, and had been a liaison officer inside MI6 to Russian Intelligence during World War I. John Gilmour, a Scottish Unionist, was the Home Secretary between 1932 and 1935, but does not appear to have achieved much of distinction: maybe he did not know exactly what was going on. Hoare himself was deeply involved with the Round Table conferences discussing India’s constitution that summer (a topic of great interest to Smolka, incidentally), and would not naturally have had reason to be distracted by the appeal of an Austrian émigré. Yet, given his questionable status, how Smolka arranged to have any personal discussion with any Hoare of influence, whether working in the Home Office or not, is something of a surprise.

MI5 appeared not to be disarmed by this recognition. On October 6, they requested the GPO to pass on all of Smolka’s correspondence for a fortnight (‘the usual list of letters’). There were only five letters during this period, but four came from Vienna (their contents were not filed). And immediately this fortnight was over, Smolka started to exploit his new status by some provocative travel. He left Folkestone for Boulogne on November 25, returning to Newhaven on December 12. A further batch of over twenty letters had been intercepted during this period, again mostly from Vienna – not all from the Neue Freie Presse. Thereafter the record turns eerily silent, with the next item constituting Smolka’s departure for Boulogne on August 1, and onward to Vienna, at which time the mail interception process resumes.

What do we know from other sources about Smolka’s movements during this time? Modin wrote that Philby met Smolka in Austria in 1934. Foges stated that Smolka worked with Litzy and Kim in the sewers. Drazin indicated that Smolka had met Philby in London in 1933, and that he returned to Vienna a year later. (That could refer to the August trip.) Drazin also claimed with confidence that Smolka presented Litzy to Philby. That could also not be precisely true: Philby arrived in Vienna in late summer, and he met Litzy soon afterwards. But Smolka, who returned to Britain a month before Philby was directed to go to work in Vienna as a courier, could have given Kim an introduction orally before the latter left. Shelden claimed (probably based on what Lotty Smolka told him) that Litzy introduced her future husband to Smolka, thus placing the encounter between mid-January and mid-February. Yet that sounds like a deception: since Litzy was Lotty’s best friend from their schooldays, it seems more probable that Smolka would have recommended that Philby stay with the Kollmanns when he advised him in the summer of 1933. The various testimonies to Smolka’s contribution to subterranean lore would nevertheless seem to show that he had indeed been active in the sewers.

One of two explanations seem possible to me: a) the accounts of Smolka’s work for the Viennese communists that spring of 1934 are pure fantasy; or b) the British authorities covered up the records of the travel of the Smolkas. The evidence in support of the former is flimsy, of ‘dog in the night-time’ character. No one outside the Smolka family appears to have recorded his presence and activity. Why did no one employed by MI6 (either officially or unofficially) notice Smolka’s presence in Vienna, especially since he was close to Litzy and Kim? Would he have attended the wedding? E. H. Cookridge, who was political editor of an unnamed morning newspaper, does not mention him. G. E. R. Gedye apparently did not notice him. The head of MI6 Station Thomas Kendrick apparently sent no report on him, and there were various English-men and -women floating around Vienna, for example Stephen Spender, Hugh and Dora Gaitskell, John Lehmann, Naomi Mitchison, Emma Cadbury, as well as the American Muriel Gardiner, none of whom appeared to detect or remark on his presence.

Yet, if the testimony of Montagu can be relied upon, Smolka drew upon his experiences to write some insightful short stories. And why would his wife and Foges draw attention to such escapades, except perhaps to elevate Smolka’s heroism? (The photographs of him suggest a fastidious character perhaps rather diffident about soiling himself in the sewers.) Yet several questions need answering. Why would the Neue Freie Presse, having just installed a new head in its London bureau, very soon after call him back to Vienna for several months? – unless it had been compliant in the whole endeavour, which is not out of the question. The major piece in the puzzle lies in the behaviour of the British authorities.

Whether or not Smolka did spend some time in Vienna in the spring of 1934, his Personal File, with its utter lack of entries between December 1933 and August 1934 represents incriminating evidence either way. If Smolka (and his wife) did leave the country – and return to it – during that time, the port officials should have recorded the fact, and informed MI5. If they did so, the information was suppressed. And if the couple never left, one would expect conventional monitoring of them to have continued. But there is nothing. Why would MI5, having been surveilling Smolka closely, suddenly be so casual and uninterested in the activities of a known Communist who made frequent trips to the Continent? Moreover, when Smolka gave an account, in his naturalization request of 1938, of all his movements abroad, he omitted any reference to travel between December 1933 and August 1934, which would have constituted a signed perjurious statement if he had indeed visited Vienna.

Was Kendrick, in Vienna, told to turn a blind eye? He has been accused of negligence. In her biography of him, Spymaster, Helen Fry wrote that he overlooked ‘the majority of the prominent, potentially dangerous, communists in Vienna’, which group may have included Smolka. Her focus shifted, however, as she shifted to make the following controversial statement:

It is, however, possible – though not yet definitely proven – that Philby went to Vienna in 1933 to penetrate the communist network for SIS and was, in fact, working for Kendrick.

I discussed these assertions a few months ago, in https://coldspur.com/kim-philby-always-working-for-sis/, and explained why I thought that hypothesis unlikely. Yet I pointed out that the earlier 2014 version of the book contained an even more shocking claim, made to Fry by a source who wished to remain anonymous, that Philby had ‘always been working for us [i.e. MI6]’. The person told her that it would ‘destroy the book if you say so openly’. Fry did as much, however, by quoting him, and then decided to remove this provocative assertion from the sanitized edition. My conclusion was that she had indeed been nobbled.

Of course her informant may have been a relic who had had ‘intelligence’ passed on to him from the ‘robber barons’ of MI6 who believed that Philby was innocent, and claimed that he had been manipulated by MI6 to pass on misinformation to the Russians. Yet it was a bit ridiculous to assert, as late as 2014, decades after Philby’s escape, confessional memoir, and death, that he had always been a loyal servant of MI6. After all, what did the informant know of 1933? What did ‘always’ mean? Thus the warning may simply have been a traditional smokescreen by current MI6 officers to cause as much confusion as possible. After all, if there was anyone who ‘had always been working’ for the KGB or any of its predecessor structures, it was Kim Philby.

Moreover, there are important issues of tradecraft to be considered. If Philby, as E. H. Cookridge reported, told him that he had close contacts with the Soviet Consul, Ivan Vorobyev, and Vladimir Alexeievich Antonov-Ovseyenko, later to be revealed as an OGPU officer, it was remarkably stupid of the Englishman. It caused a breach between him, on the one hand, and Cookridge and his anti-communist friends on the other: Philby must have misjudged his colleague’s probable reaction. Thus, if MI6 had in reality tried to exploit Philby’s presence in subversive circles to infiltrate the Communist organization in Vienna, Hendrick must have firmly believed a) that Philby was naturally loyal to the British democratic cause, and to MI6; and b) that the Communists could not possibly have any inkling that Philby was working secretly for British Intelligence. If, as seems clear, Philby did spill the beans, he had been remarkably poorly briefed. Indeed, Cookridge assumed that Philby had been compromised by the summer of 1934, and had to leave Vienna in a hurry [in fact in April]. It was more likely that MI6, if it had put out feelers to Philby, suspected that their game may have been rumbled. If the OGPU had smelled a rat, Philby would have been permanently discarded – unless he had been able to convince his contacts at the Consulate that he was in fact loyal to them, and that he was cleverly manipulating Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service. That would suggest, of course, that he had already been recruited by the Soviets.

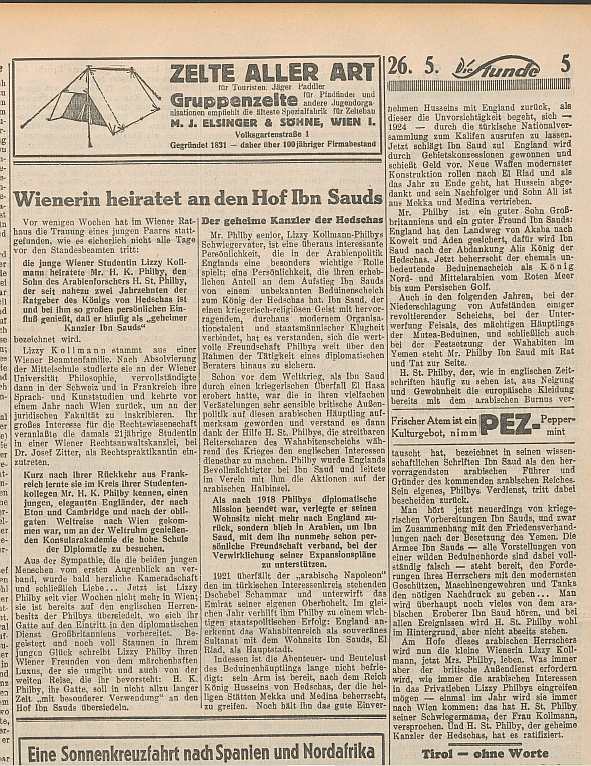

All this makes the release of information on the Philby wedding to the Austrian Press even more poignant and dramatic. The item (see below) was published in the Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung on May 25, 1934. I extract, highlight, and translate or paraphrase the more significant portions of it. (Readers should recall that Philby had been married to Litzy on February 24, 1934, and the pair had left Vienna on April 28.) The headline reads: ‘A Viennese woman marries into the court of Ibn Saud’, which must have come as a rather startling revelation to those who knew the young leftist firebrand. Litzy was already an agent of the OGPU, was under strict police surveillance, and had probably been set up as part of a honeytrap to capture the young Briton, which makes the following story even more absurd.

The column, having introduced Litzy Kollman [sic] as a student, mentions her marriage to ‘Mr H. K. Philby’, who is identified solely by virtue of his father, a two-decade-long advisor to the King of Hejaz, who had enjoyed such great influence with the King that he was frequently dubbed ‘the secret Chancellor of Ibn Saud’. This was not strictly true. Ibn Saud was the King of Saudi Arabia, and he had annexed the kingdom of Hejaz a couple of years beforehand. No matter. The writer then attempts to set up Litzy as a dedicated scholar with ambitions of becoming a legal expert with the practice of Dr. Joseph Zitter. According to the report, she then encountered Philby in her circle of student-colleagues, ‘a young, elegant Englishman, who, after Eton and Cambridge, and after the obligatory world tour, had come to Vienna to attend the world-famous College of Diplomacy’. Who provided the writer with this nonsense is not clear.

Naturally, the couple fell in love, and the young Viennese treasure is reported to be no longer in her home city. “She is already installed in the lordly mansion of the Philbys, where her husband prepares himself for entry to Great Britain’s diplomatic service”. The writer continues: “Inspired, and still amazed by her fresh good fortune, Lizzy Philby writes to her friends in Vienna of the fairy-tale luxury that surrounds her [no flea-bitten pad in Hampstead, then, under the eye of a sternly disapproving mother-in-law], and also of the long journey that awaits her: H. K. Philby, her husband, is shortly to be transferred ‘with special disposition’ to the court of Ibn Saud.” The column then switches to a long explanation of the history of the region, and of Philby Senior’s role since the end of World War I.

Harry St. J. Philby is described as being ‘a good son of Great Britain and a good friend of Ibn Saud’, but in reality Philby worked mostly against British interests. He opposed the Balfour Declaration, and he worked behind Britain’s back in seeking out agreements on oil concessions with the USA, and even with Spain and Nazi Germany. There are veiled references to Nazi affinities: Philby père is quoted as writing that he considered Ibn Saud ‘the outstanding Arab “Fűhrer” and ‘founder of the incipient Arab “Reich”’ – all very deliberate and weighty words. Readers of the column are advised to watch developments in this sphere closely. “They should expect to hear a lot more about the Arab conqueror Ibn Saud, and, according to past events Philby will surely loom in the background, but not to one side.”

And how does this scenario affect our young, happy couple? The conclusion is muddled, and sentimental. “The petite Viennese Lizzy Kollmann, now Mrs. Philby, will soon reside at the court of the Arab ruler. Whatever the British Foreign Office may demand, and however Arab interests may interfere with Lizzy Philby’s private life – some time during the next year she will return to Vienna: H. St. J. Philby [sic: should be ‘H.K.’] has promised that to his mother-in-law, Mrs Kollmann. And H. St. Philby, the secret Chancellor of Hejaz, has confirmed it.”

How the British Embassy thought it could get away with this charade is unbelievable. After all, there were several Britons still around in Vienna who knew enough about the real life of Litzy and Kim – including the fact that she was not a Kollman at the time of her marriage, and that the innocent young student had already married and divorced one Karl Friedmann. In Treason in the Blood, Anthony Cave Brown wrote of the marriage: “All who were interested heard about it and gossiped about it, and the British community in Vienna was astonished.” It seems that Kendrick must have been under pressure to show that the British authorities had no knowledge of any subversive activities on the part of Kim, and that he needed to present him as a true cion of his right-wing father. It was trying to send a subtle message to the Soviet Consulate. Yet the column is an extraordinarily clumsy creation. Why did they think the Soviets would be taken in? And why was everyone silent over this disinformation? The visitors from the UK surely must have read it. For example, it is not clear how long Cookridge stayed in Vienna (he was later incarcerated in Dachau and Buchenwald by the Gestapo), but he made no mention of it in The Third Man.

All this sub-plot about the Philby wedding leads back to Smolka, if indeed he were still around. If so, he must surely have read the piece, and he would have enjoyed discussing it with his handlers at the Soviet Consulate. Maybe he even had a hand in composing it, with his journalistic skills, and love of intrigue. For one has to start asking the very searching question that this pattern of activity provokes. Did MI6 believe that they had a similar influence over Smolka at this time as they did over Philby? Had they made overtures to him, back in England in 1933, with the idea that he might become an informer for them in the Communist camp? And did they then start to dangle his pal Philby in a similar manner when they discovered what he was up to with Litzy? And had that part of the plot even been dreamed up in London?

I shall return to that controversial conjecture next month, and here tidy up the loose ends of 1934. In any case, Arnold Deutsch left Vienna for London in May, quickly on the heels of the newlyweds (some write that he left before them). If we are to believe Philby’s account of the events that followed, the spy was recruited after some furtive meetings with Deutsch, arranged through the intermediary Edith Tudor-Hart. Yet that schemery was not necessary: it is much more likely that Deutsch was dispatched to verify the determination and loyalty of the OGPU’s new recruit after the rumours in Vienna. Moreover, Philby’s timetable is impossible: if he left Vienna on April 28, and travelled via Prague and Paris by motorcycle (as Cookridge recorded), he would not have been able to attend the May Day parade in Camden (as Philby later claimed).

An alternative scenario, as described briefly in the later chapters of memoir by Philby (published in The Private Life of Kim Philby) suggests that he and Litzy travelled by train, via Berlin and Paris.

Meanwhile, what were the Smolkas doing during the summer, how did they survive, and when did they return to the UK? No record appears to exist. Maybe he was being maintained safely by his Soviet protectors until they gained verification that his comrade from the sewers was reliable, and that it was safe for him to return to the United Kingdom. The owners of the Neue Frei Presse were presumably still complaisant. And then Smolka returned to Vienna in early August, 1934. Perhaps his task was to inform his bosses, in person, that the ring was safe, to confirm that Philby was reliable, and had been formally recruited by Deutsch. For the Comintern wheels were in motion again.

The very same day that he returned, on September 4, Litzy left England for France, and then Spain. Orlov left Vienna for Paris, then London, in mid-September, and his family joined him soon afterwards. Guy Burgess (who had written to Isaiah Berlin in May, informing him that Philby had just returned from ‘fighting in Vienna’) wrote to Berlin early in September to let him know that Philby was staying with him. The PEACH files even inform us that Litzy returned to Vienna, for one month, on September 21 – a dangerous exploit had she not been protected by her British passport. In October, Edith Tudor-Hart recruited Arthur Wynn at Oxford, and Philby was instructed to introduce Donald Maclean to Ignaty Reif. On November 7, the MASK traffic reported that MARY (Litzy) had arrived back safely in London.

MI5 did not appear unduly surprised or excited about Smolka’s re-appearance, as if it were completely routine for a communist under surveillance to have taken another trip to a highly volatile city. One might expect urgent confabulations with MI6 to have taken place: if they did, nothing has survived in MI5 files. A week after Smolka’s return, ‘Tar’ Robertson requested of the G.P.O. a ‘return’ of all correspondence addressed to him, such intervention to last for a fortnight. This is an unusual formulation: a warrant for inspection of a suspect’s mail conventionally ran as follows: “I hereby authorize and request you to detain, open and produce for my inspection all postal packets and telegrams addressed to . . .”. Similar requests had been made in October and November 1933: it seems that a list of all correspondence, with senders identified only if they appeared on the envelope, was the result. Vienna again features strongly, and there is an intriguing letter arriving on September 17 from Guetan in Spain, against which someone has scribbled a half-obscured note mentioning ‘Lizy’. In any case, Robertson was interested enough to request the Home Office file (638153) on Smolka, which contained his Alien record, and the correspondence with the Home Office from November 1933.

Jasper Harker then picked up the baton, writing to Sir Arthur Willert at the Foreign Office for a list of all accredited representatives of the Neue Frei Presse. Willert was under the impression that Smolka, the chief representative of the publication, had been chief for some years, and had just announced that he had hired an assistant, Dr. Robert Ehrenzweig. In a handwritten note, Willert added that Smolka is ‘rather a bore, but decent’, and had an office at the Times premises on Printing House Square. No obvious action results from this inquiry.

As all this busy re-energizing of networks was taking place, and MI5 rather laboriously started paying attention to Smolka again, he then took what might have appeared to be an unnecessarily bold step. Writing as London Editor of the Neue Freie Presse, on notepaper listing its address as Printing House Square, on November 15 he alerted the Undersecretary of State at the Home Office to his intention to form the London Continental News Ltd., along with his British colleague Mr. H. A. R. Philby. He hopes that the Home Office will not raise any objections, and adds in a handwritten addendum: “I have at the same time informed the Press Department of the Foreign Office on this matter.”

While it may seem a little premature for Smolka to have informed the Foreign Office before he had gained permission from the Home Office, this seems a remarkably flamboyant way of drawing attention to his association with Philby. Was it really necessary? The formal response is not included in the file, but extracts from the Home Office papers indicate that a letter was sent to him on January 3, 1935, stating that the Office had no objections, and Harker concurred with that decision.

As so often occurs with these sagas concerning British Intelligence and Communist agents and spies (Ursula Kuczynski, Tudor-Hart, Litzy and Kim Philby, Smolka), one has to pose the challenging questions: Why was the OGPU/NKVD/KGB so brazen in the gestures it threw out? And why were MI5 and MI6 so sluggish and inattentive in their response? It was surely unnecessary for Smolka to draw the attention of the British authorities to his close association with someone who had been watched contributing to leftist subversion in Vienna. One can only assume that he did it as an act of bravado, to prove to himself (and maybe his bosses) that he and Philby were both considered harmless.

As for MI5, who clearly maintained an active file on Philby, the passivity over this letter from Smolka, however superficially uncontroversial, is astounding. The letter was not weeded out at the time. Either someone who had no idea who Philby was (despite the recognition that he had been allocated a PF) added it to the file in innocence, and no senior officer checked what was happening. Alternatively, someone in authority decided that this was all above board, and gave no cause for concern. And why did the document not ring alarm-bells when it was discovered in the late 1940s (as it surely must have been), when Philby began to fall under suspicion? Yet, even in 2015, no one deemed that the publication of the letter was damaging, and that the lack of activity thereafter might prompt some awkward questions.

I offer another explanation for the remarkable number of hints about Philby’s misdemeanours to be found in the archive. MI5 officers were dismayed by the conduct of their ex-chief, Dick White, when he was transferred to lead the rival organization, MI6, and later shown to have been taken in by Anthony Blunt during the war. White then compounded his guilt by allowing Philby to flee unpunished, and then by initiating a damaging search within MI5 for the fictitious ‘agent ELLI’, bringing Hollis, Mitchell, McBarnet and others under suspicion. A generous sprinkling of notes incriminating Philby, and thus embarrassing MI6, was made across various files, awaiting someone in posterity to integrate them into a coherent story, and thereby clear MI5 of any further betrayal.

The last observation I make at this juncture is that another familiar pattern shows itself – the fact that senior officers in MI5 (and probably MI6) made decisions of highly strategic import that they did not confide to their underlings. Thus we encounter the familiar phenomenon of organizational dissonance: a story of eager young officers asking searching questions, but being discouraged when their managers try to diminish the significance of their inquiries, and attribute the suspicious signals to misunderstanding or some kind of prejudice.

Conclusion

This investigation has perhaps been the most challenging that I have ever set myself. The source material is cluttered with lies, deceptions, omissions and evasions. Yet behind it all there must be a narrative that makes sense. There always is. All the actors must have believed that each step that they undertook was either furthering their career (or perhaps preventing it from coming to a grisly end), contributing to the success of the agency for which they worked, or even helping the cause of the nation or movement to which they were ultimately committed. Their priorities were normally in that order. Yet I do not believe that any documents are suddenly going to come to light that will undeniably and permanently clear matters up.

Those readers who have been following my posts over the past few years will probably be able to guess where this line of research is leading. Next month I shall present my analysis of the final five chapters of the Smolka story. In the meantime, however, I appeal to you to get in touch with me – on errors of fact, on mistakes of logic or interpretation, on overlooked source material, on misunderstood procedures. I need all the help that I can get.

(New Commonplace entries can be seen here.)