Skylark, To To amuse oneself in a frolicsome way; to jump around and be merry; to indulge in mild horseplay. The phrase was originally nautical and referred to the sports of the boys among the rigging after their work was done. Hence perhaps the popular boat name, as in ‘All aboard the Skylark’. (Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, 18th Edition)

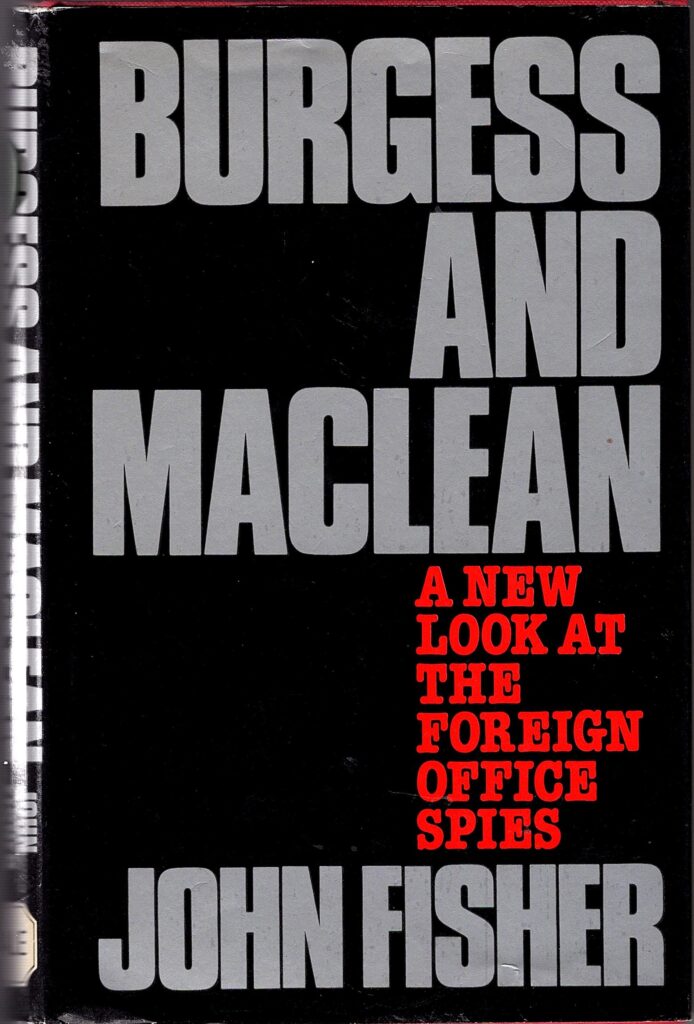

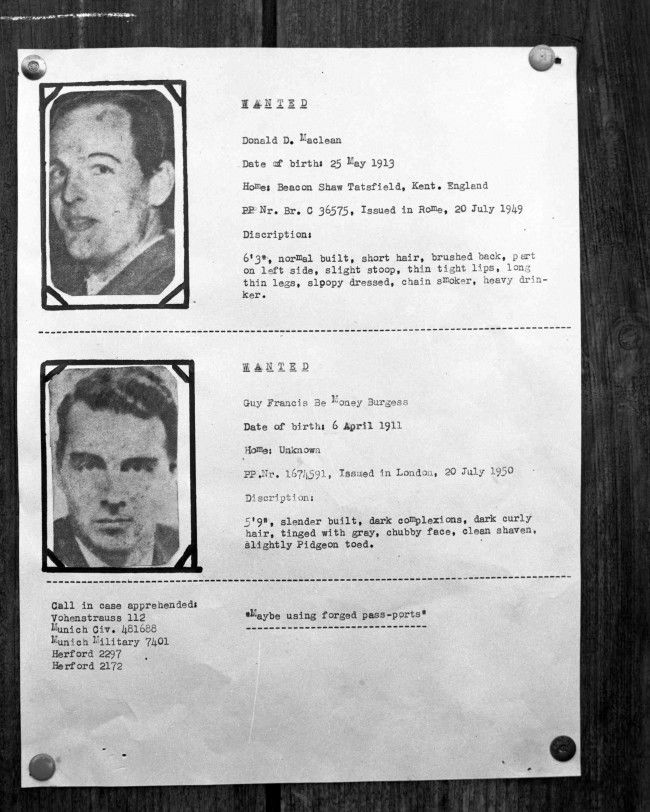

In this bulletin, I outline my case that the escape of Burgess and Maclean was facilitated by the British authorities. But first, a diversion . . .

A Self-Important Announcement

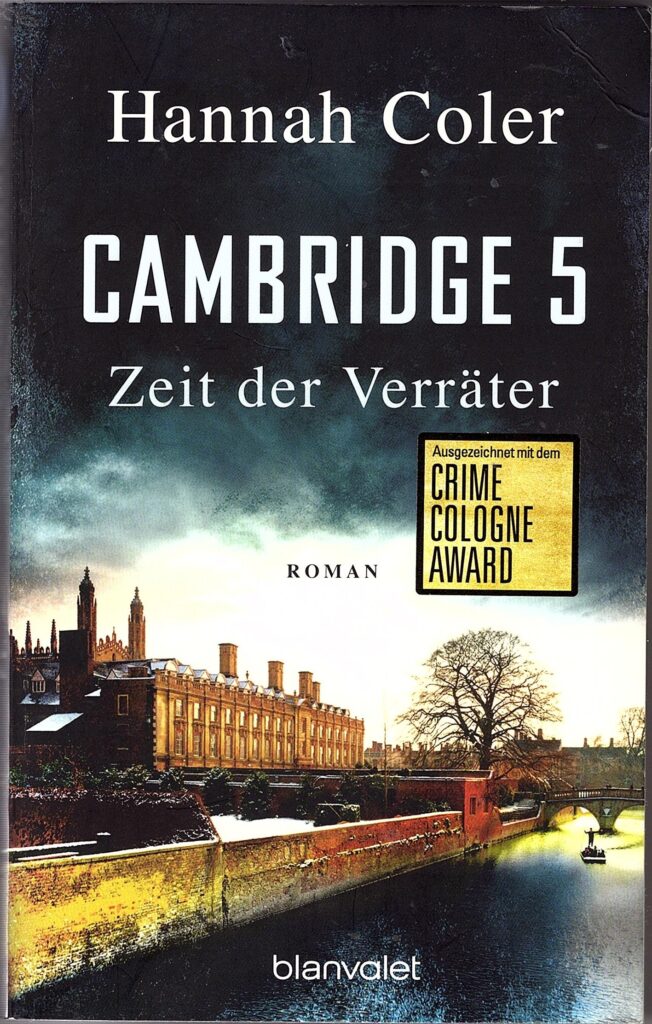

Before I get to the main agenda for this month, I need to make an announcement. I shall be visiting the UK this September, for the purposes of delivering a talk on the Cambridge Five at my old school (see https://www.whitgift.co.uk/my-whitgift/alumni/events for details), and of attending a re-union. This will probably be my farewell tour of the Old Country – not because I expect that officers from Special Branch will be waiting at Heathrow to clap the handcuffs on me, although I do not discount that possibility – but because making the arduous trip over becomes less and less appealing as I approach my eightieth year. I should thus like to make the most of what will probably be a stay of about two weeks between (roughly) September 5 and September 22.

I am going to seek out further speaking opportunities (the current talk is scheduled for September 12, in Croydon). As a Lifetime Member, whose career was recently featured in the Society’s Newsletter, I have approached the Friends of the Bodleian, who are this year celebrating their centenary, but their calendar is full for September. I am also a Lifetime Friend of the National Archives, but two emails to them (President and Secretary) have failed to gain any acknowledgment, even, which is disgraceful. (Don’t they know who I am??) I have written to my alma mater, Christ Church, Oxford, which is celebrating its five-hundredth anniversary this year, to suggest a lecture on one of their most celebrated – or notorious – alumni, Dick White, but after two weeks have not yet had a response. I have one or two other leads to follow, but if anybody out in coldspurland has a local historical society that might be interested, please let me know. I could talk on any one of my pet subjects (Sonya, the Cambridge Five, Dick White, Spycatcher, Flight PB416, PROSPER, Borodin, etc., etc.), or maybe give a more general, but light, presentation on the practice of interpreting archives, with liberal examples. The week of September 15 is probably best, so please contact me if you are interested.

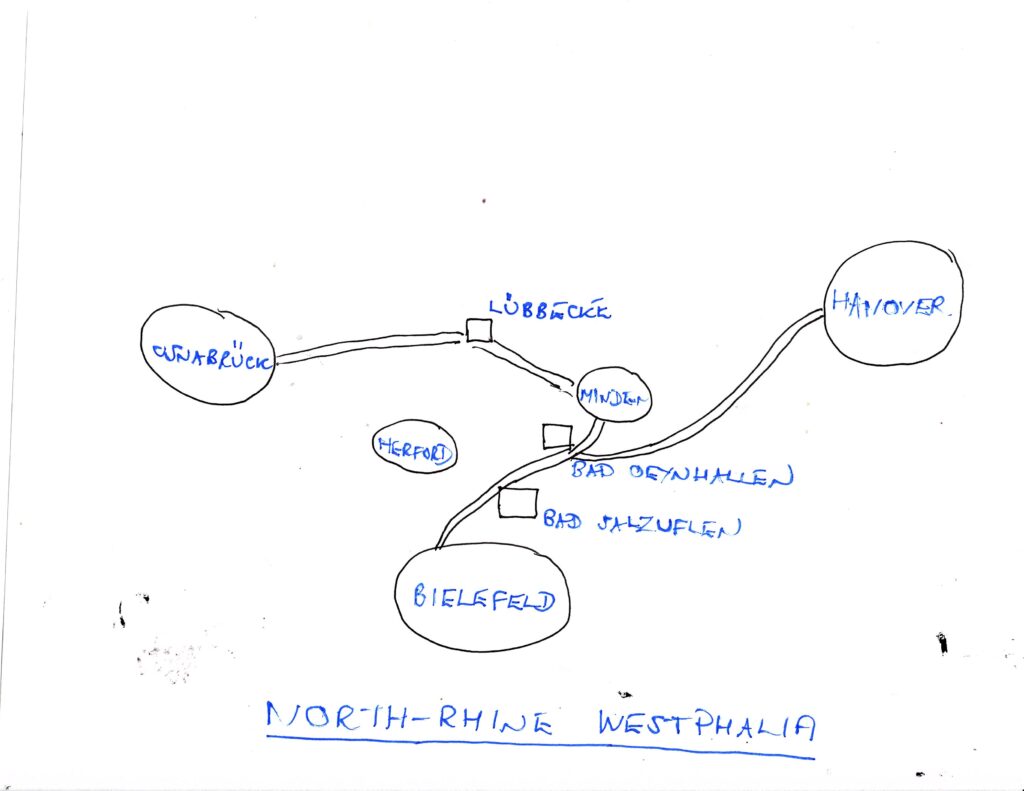

In any case, I should very much like to meet colleagues acquired on-line through coldspur with whom I have frequently engaged over email, but whom I have never met. From discussions already under way, I can envision an itinerary taking in London, Oxford, Cheltenham, and Cambridge, one that could be extended to destinations not too far off that track. Again, please get in touch with me, and let me know your place of residence, and your availability. Thank you! And now back to research and analysis. (This story of the ‘Missing Diplomats’ continues to evolve, and there will be more to come.)

Contents:

Introduction

The Committee

William Strang

Theory and Methodology

Actors and Agents

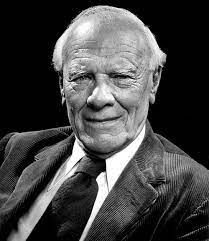

Dick White

The Cambridge Four:

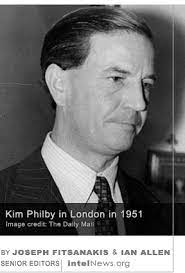

Kim Philby

Guy Burgess (and Goronwy Rees)

Anthony Blunt

Donald Maclean

The British Authorities

MI5’s Dysfunction

Carey-Foster and the Security Department

A Possible Sequence of Events

A Lack of Imagination

Prosecution

Surveillance

Authority

Conclusions

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

I believe that the British authorities facilitated the escape of Burgess and Maclean.

Yet that sentence must immediately be qualified. Who were the ‘British authorities’? It is a lazy trick of the casual historian (I have done it myself) to hide behind generalities, and to write (for example) that ‘MI5 did this’, ‘the Foreign Office believed that’, ‘MI6 was opposed to something else’, without identifying particular agents, actors or authors, as if all decisions emanated from some impeccably drafted high-level policy, and were executed without dissension. Matters were far more complex than that, and I try to make it my business to assign responsibility to individuals where I can. Bureaucrats, however, have a particular partiality for using the passive voice, and thus disguising how decisions were made: authorized histories hiding behind unidentifiable sources aggravate the problem. The ‘authorities’ were a nebulous group: they were neither authoritative nor authoritarian, and they thus failed to control the narrative.

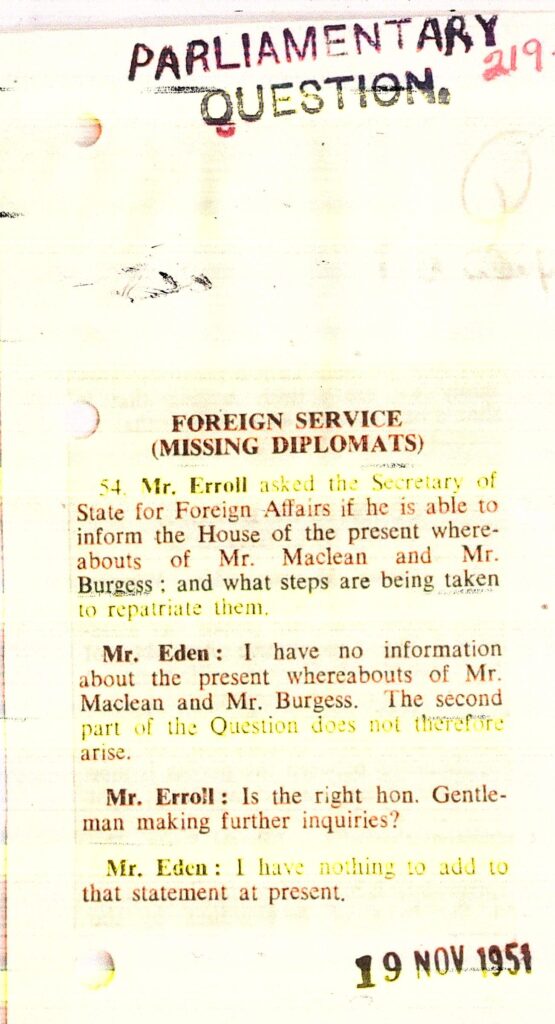

In other words, ‘the British authorities’, and ‘British intelligence’ were not, and are not, unitary, monolithic, single-minded, unlike the Russian Intelligence Services, where no one would raise a finger unless they knew that Stalin had already approved such a movement. In post-war United Kingdom, conflicts reigned, both inside and outside intelligence. That was an inevitable – and not always regrettable – outcome of pluralist tensions. A Labour government brought some very equivocal attitudes towards communism and the Soviet Union. Differences of opinion concerning policy towards the Soviet Union existed within the Foreign Office. As the Cold War began, some officials wanted to continue the policy of co-operation with, and appeasement of, the Soviet Union that had pertained during the war. Other factions were influenced more strongly by the Chiefs of Staff, who saw a direct military threat after watching Stalin’s actions in Eastern Europe. Residual officers from SOE within MI6 tried to restart subversive efforts behind the Iron Curtain, while a more traditional faction wanted to focus on intelligence-gathering. Politicians and leaders were often kept in the dark by their intelligence units. Herbert Morrison, the Foreign Secretary, was not told of the abscondment of Burgess and Maclean until several days after they escaped. Prime Minister Churchill and Foreign Minister Eden, on their taking office in November 1951, were not told the true story of the events.

As far as the intelligence services were concerned, there were rivalries and overlaps between MI5 and MI6. Moreover, within the services, decisions and information were often carefully protected. In MI5, Percy Sillitoe, the director-general, was not broadly respected by his subordinates, and was not kept fully informed of how B Division was dealing with the FBI and the CIA. White (in 1951 counter-espionage chief) and Liddell (deputy director-general) did not always disclose the decisions they had made to all their underlings – or even to each other. The details behind the case of Agent Sonya (Ursula Beurton), whose marriage and subsequent passage to Britain from Switzerland were abetted by MI6, were not divulged to the junior officers investigating her possible use of wireless. Certain files were kept as Highly Secure, not available for casual inspection. Officers posted memoranda that display complete ignorance of the reality behind events, such as J. C. Robertson’s annotation that Volkov’s warnings were referring to Guy Burgess’s spy network. Dick White did not inform Robertson of his scheme to pass on the Philby file to the FBI, otherwise White would not have had to swear his group to secrecy over the Philby identification in early 1952. It appears that Graham Mitchell, head of D Branch in 1954, had not been told by White about the dealings with Blunt.

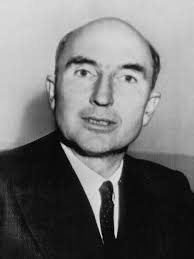

The committee responsible for investigating the leakages from the British Embassy had started out in 1949 as a broader group, including Valentine Vivian from MI6, but by the spring of 1951 it constituted a tight cabal of career officers: William Strang, Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs (later Lord Strang); his deputy, Roger Makins (later Lord Sherfield); Patrick Reilly, assistant secretary at the Foreign Office, and sometime personal secretary to Stewart Menzies, chief of MI6; George Carey-Foster, Security Officer at the Foreign Office; Percy Sillitoe, Director-General of MI5; and Dick White, head of B (Counter-espionage) Division at MI5. These six men were ultimately responsible for the handling of all aspects of the events leading up to the surveillance of Donald Maclean, and the escape made by him and Guy Burgess. They were abetted by Geoffrey Patterson, the MI5 Liaison Officer in Washington, and Robert Mackenzie, the Foreign Office’s Security Officer at the Washington Embassy. Dick White confided especially in his subordinate Arthur Martin. After the abscondment, J. C. Robertson, head of B2 (Soviet counter-espionage) became a key member of the MI5 investigating team. Some reports state that the half-dozen members of Carey-Foster’s team knew all about the investigation.

William Strang was the senior official on the project, and, as Permanent Under-Secretary, responsible for all Foreign Office personnel. For research into this piece, I read his 1956 memoir, Home and Abroad. The author comes across as highly intelligent, erudite, humane, and sensible (although he did have a darker side). He very pointedly sidesteps the issue of Burgess and Maclean, however. In his Foreword, he writes: “As was to be expected, my publishers asked why I had not written about the case of Burgess and Maclean. The answer is simple. Even were I in a position to do so, it would not be open to me as an ex-official to add anything to the public statements already made by Ministers on the substance of the case; while merely to repeat those statements or any part of them would be otiose.” It is a characteristically cautious statement, Strang being reluctant to admit any irregularities, or to the fact that he had passed on disinformation to his masters, as had senior officers in his department.

Yet it is in many ways surprising, given his experience and wisdom, that he allowed the intrigues of White to proceed unchecked. It appears that he did not keep his Minister, the ailing Ernest Bevin (who resigned on March 9, 1951, and died the following month) informed, nor did he fully advise Herbert Morrison, Bevin’s successor, who was replaced when the Conservatives regained power in October. Moreover, his first briefing of Anthony Eden appeared to take place only in March 1952, when he admitted that his Foreign Office employees, Burgess and Maclean, had been spies for some time, and that Philby had probably been one throughout his MI6 career. That was something that he had understood for well over a year, so his reticence shows a large degree of discomfort, and his dedication to rectitude and honesty must be questioned. It is clear (for instance) that he lied to Christopher Steel in the Washington Embassy, claiming that Maclean had come under suspicion as the ‘leaker’ only after he disappeared. (It also sheds dazzling light on the untruths told by Macmillan and Eden later in the House of Commons.)

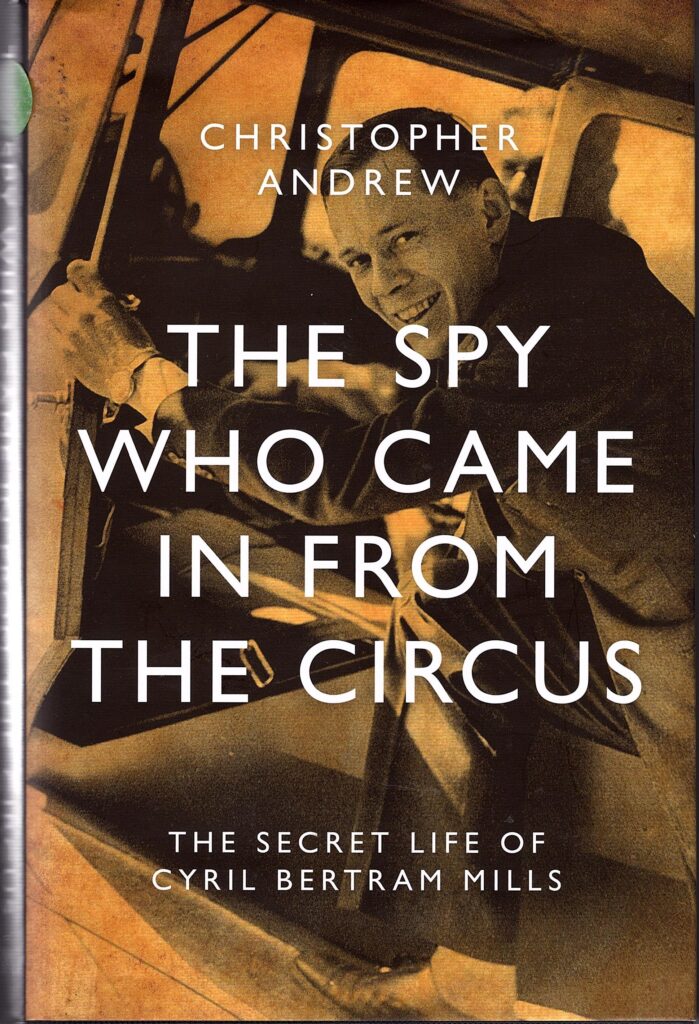

I judge that Strang was probably too correct a man to understand the machinations of the intelligence world: he was also extremely busy, and before the escape probably considered this business as a low priority. He took control thereafter, but struggled over what he should say to his Minister, and to the Washington Embassy. The bottom line is that, apart from Strang, those persons actually in ‘authority’, namely the Prime Minister and his departmental ministers, as well as the chiefs of MI6 and MI5, did not receive a full explanation of what was going on. Strang was probably deceived to some extent, as well, but that does not absolve him from failing to take a more active role in the investigation. This was a prominent civil servant who had dealt personally with Stalin, Litvinov, Molotov, and Gusev. He knew the nature of his country’s adversaries, but showed no operational leadership in the consideration that Stalin may have planted spies in his nest, and he should probably have anticipated the minefield that White’s deviousness was setting. A later opinion on Philby [see below] suggested that he was very comfortable with the idea of letting Burgess and Maclean escape, but he obviously did not want to admit that in June 1951. Strang’s psychology, and his interpretation of his duties during the whole business, are of great interest, and merit a separate study. You will find no entry for ‘Strang’ in Christopher Andrew’s Defend the Realm. Andrew has made much of intelligence being the ‘missing dimension’ of history, after his colleague David Dilks, but he has been negligent in tracking the dynamics of the interactions between the intelligence agencies and their political masters.

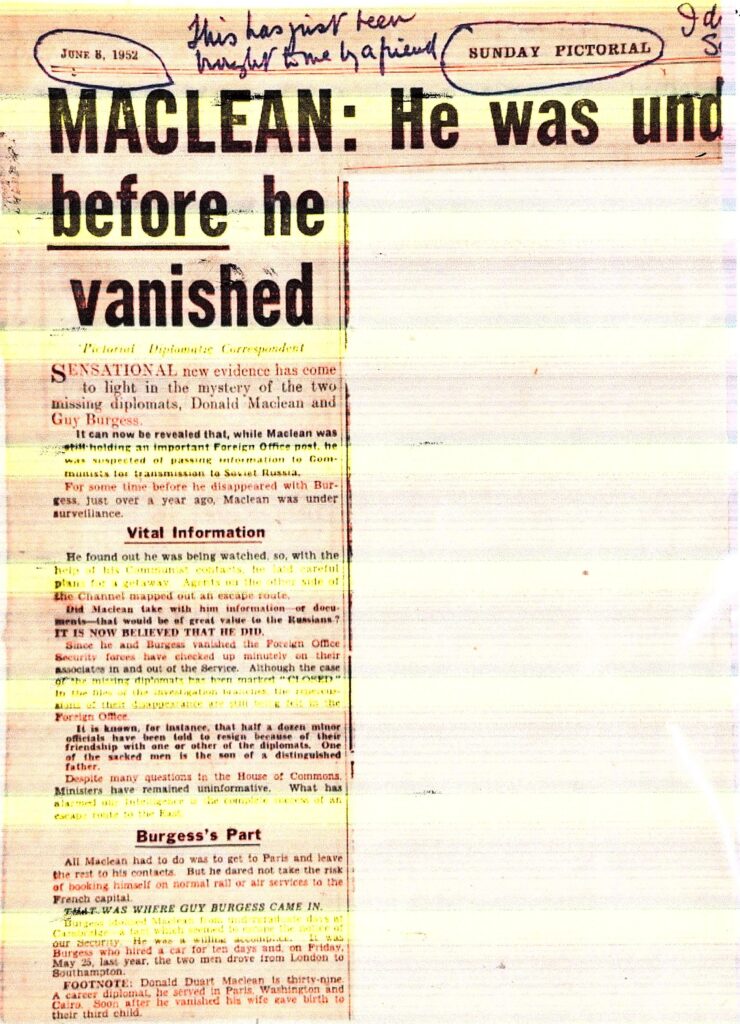

I find the conventional accounts of the successful escape of Burgess and Maclean utterly unconvincing, and hereby present an alternative analysis. I recently read Murder in Cairo, the recently published book by Peter Gillman and Emanuele Midolo about the murder of the Sunday Times journalist David Holden in 1977, and came across the following sentence: “The journalists would follow what had become a tried-and-tested formula: gather every available scrap of information, assemble it into a coherent narrative and trust that the answers to the central question would become clear.” In that proud boast is encapsulated all that is wrong about the Phillip Knightley, Anthony Cave-Brown, John Costello, Andrew Lownie, Helen Fry, etc. etc. school of writing on intelligence matters. Trawl around for every conceivable factoid, treat them all as equally valid without verifying them, or cross-checking them, and hope that the reader will be able to discern from the resulting narrative what really happened. It is a recipe for confusion.

I do not expect to find any archival evidence that the cabal identified above (essentially ‘the British authorities’) arranged matters so that Burgess and Maclean were able to be exfiltrated from Britain apparently undetected. This report is thus based largely on speculation and hypothesis. But that does not mean that it is lacking in methodology. Facing what is frequently self-implicating evidence, I apply the technique of tracking carefully the chronology of events, examining geographical details, and cross-checking accounts from different sources – as well as the very important process of assessing the probable motives of the participants. I have previously hypothesized that the priorities of most persons in the business of intelligence (and probably in many other fields of endeavour) are i) one’s personal career, legacy and reputation – including the fending off of rivals – or even fighting for survival; ii) the status and repute of the organization to which one feels allegiance; and iii) the larger overall mission for which one is supposed to be working, such as ‘Defend the Realm’. Occasionally, objectives 1 and 3 combine, when self-important actors justify their personal vagaries as helping to achieve a patriotic goal. Some figures even extend their justifications to the loftier aim of ‘helping mankind’, the latter entity normally represented as ‘progressive humanity’ in Soviet jargon, as if any individual could be presumptuous enough to understand what such pretensions meant, or how they could ever be measured. Thus, when assessing the actions and objectives of the key agents in the drama, one has to pose the questions: What did they know? What were they supposed to be doing? Which priority loomed largest in their calculations?

Actors and Agents

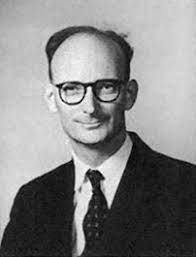

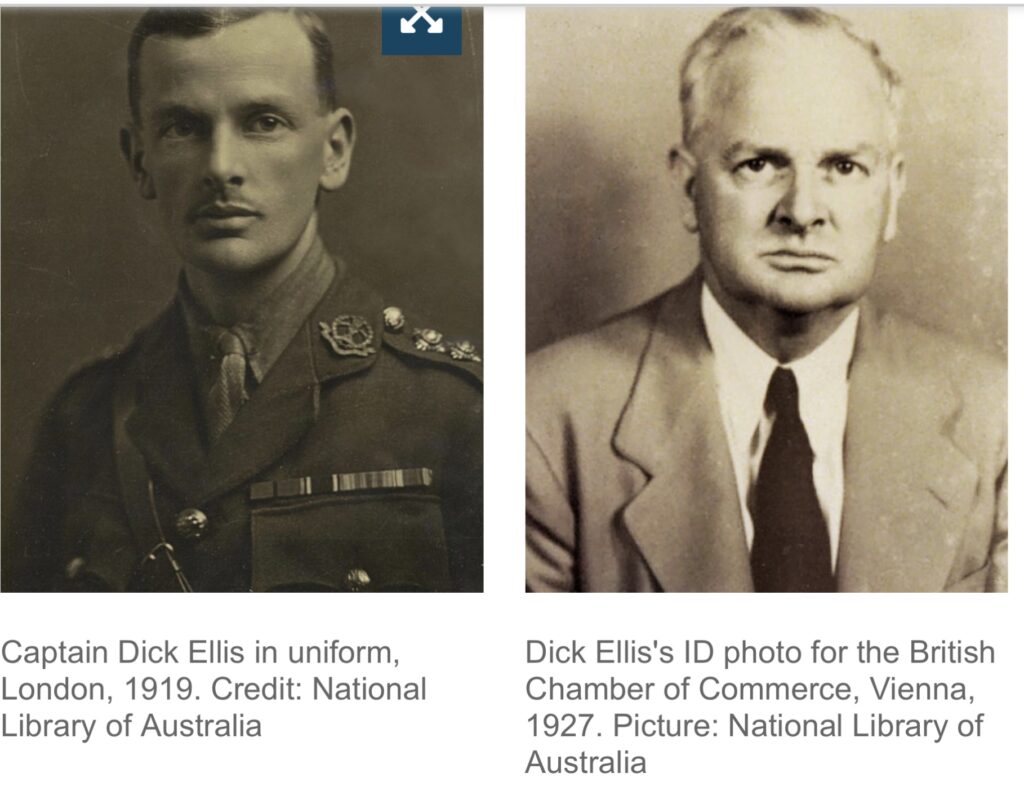

Dick White:

Dick White was essentially the one-man-band managing the project, in his role of de facto show-runner of MI5, as he arrogantly described himself to Malcolm Muggeridge. I thus first look at him, the only experienced intelligence officer on the investigating team, somebody who was probably able to influence the three grey career diplomats, his boss (the ex-police officer Sillitoe), and the greenhorn Carey-Foster. What did he know in early May 1951, when Guy Burgess returned from the United States in disgrace?

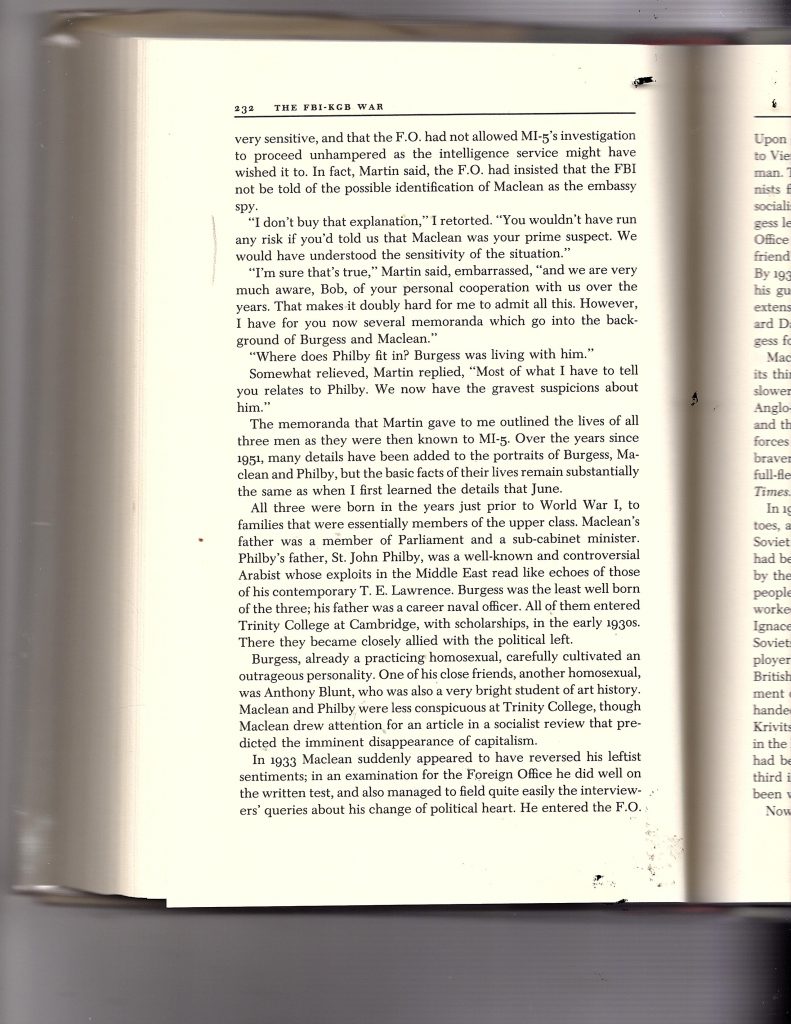

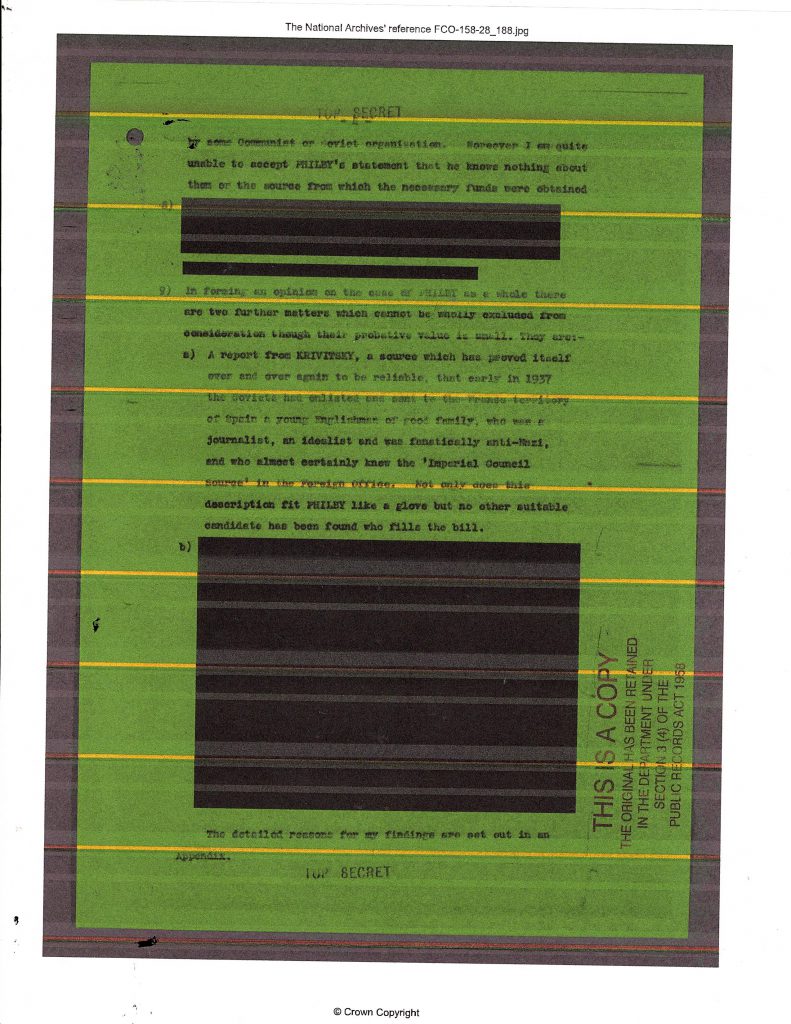

First, he was familiar with the disclosures revealed by Walter Krivitsky in January 1940, in which the defector pointed to a set of penetration agents who had been recruited in the early 1930s. Among these was a spy in the Foreign Office who had been involved with the ‘Imperial Council’ meetings, and a journalist sent to Spain during the Civil War to be attached to Franco’s camp. White would recall that these leads had not been followed up, almost certainly by dint of the fact that Kim Philby (the journalist) had unmasked himself to MI5 after the Nazi-Soviet Pact was signed, in early September 1939, and claimed that he had abandoned his communist sympathies. The lead analyst of Soviet counter-intelligence, Jane Archer, had been removed from the group immediately after her report was filed. Philby had surely brought his wife, Litzy, along with him in his ruse: whether he also identified Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt as fellow apostates is not so certain. I shall explore that possibility soon.

White knew that Anthony Blunt, who was recommended for a post with MI5 by Victor Rothschild in August 1940, and eventually served as Guy Liddell’s assistant, among other roles, had been a communist. Yet White had treated that allegiance as a harmless aesthetic impulse, and during the war he had enjoyed Blunt’s company as a fellow-intellectual among the typically more philistine interests of the MI5 collegium. I strongly believe that White would have been aware of the indiscretions of Blunt and his side-kick Leo Long in extracting confidential material and passing it on to the Soviets in 1944, but he may have considered it part of their natural cover, to convince their supposed Soviet controllers of their commitment.

Doubts about Philby’s loyalties started to creep in with White and others at the end of the war. The Volkov incident, in which Philby engineered his own management of the would-be defector’s approach to the consulate in Istanbul, building in such a delay that the unfortunate Volkov was arrested, exfiltrated, tortured, and killed, brought strong attention to the possibility that Philby himself were the counter-intelligence officer identified, but not named. The sudden flight of Litzy Philby’s new partner, Georg Honigmann, into the Soviet zone of Berlin in the summer of 1946, caused a shock, and White may well have been involved in the dubious granting of Litzy a divorce decree from Kim, an event that is inexplicable in terms of chronology and geography. Litzy then joined Honigmann in Berlin. It suggests that White began to doubt the sincerity of the Philby volte-face some time before Liddell and others did, with Liddell continuing to trust his triad of Burgess, Blunt and Rees right up until the disappearance.

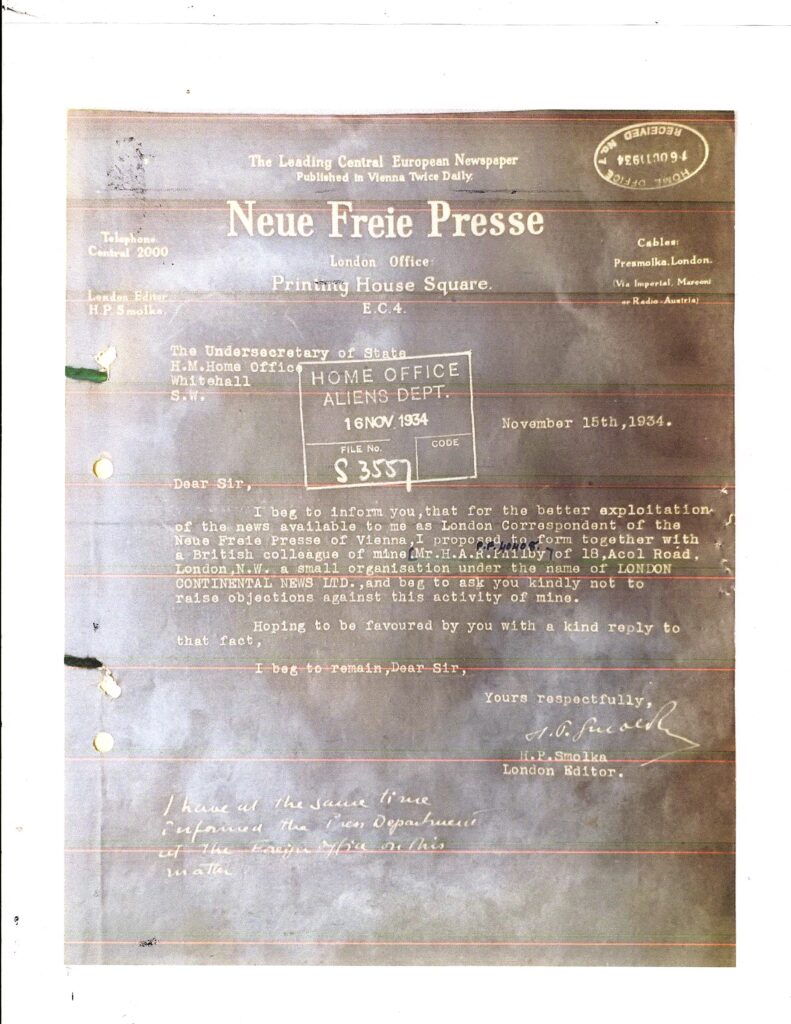

But Litzy was not the only communist, whether ex- or not, to abandon their recent country of naturalization for life behind the Iron Curtain. Peter Smolka, who had been granted UK citizenship during the war, and worked at the Ministry of Information, disappeared in Red Vienna in 1948. Ursula Beurton, aka Agent Sonya, had made a sudden flit to East Berlin in early 1950, as soon as she heard that Klaus Fuchs had been arrested. That left the neurotic and disorganized Edith Tudor-Hart, the third prominent member of female communists gaining British citizenship through marriage, as the remaining domiciliary in Britain. She was now relatively harmless, divorced, hamstrung with caring for her autistic son, and prone to falling in love with her psychiatrist and other undesirables. Yet why were all these presumed loyalists now fleeing to Stalin’s petticoats, without apparent fear of retribution?

The VENONA project, and the search for HOMER, complicated White’s counter-espionage efforts. While his suspicions concerning Philby had intensified, a name that may have been new to him as an espionage suspect, Donald Maclean, had come into view. It is evident from the archives that White soon realized that the HOMER investigation was going to break open a hornet’s nest of intrigue and embarrassment. Shortly after Kim Philby, in November 1949, had dramatically drawn attention to Krivitsky’s identification of a spy in the Foreign Office, in January 1950 White tried to call the whole exercise off – a foolish initiative that indicated he knew far more than he was letting on to his colleagues. Had Philby’s reminder prompted him to re-examine the case of the ‘Imperial Council’ spy? On February 16, White wrote a long memorandum recommending that the hounds be called off, since the field of investigation was so wide, and ‘that there was no possibility of reaching a solution unless more data becomes available’. This was a scandalous suggestion to make, since a shortlist of recipients of confidential telegrams had recently been produced (which obviously included Maclean), and Philby had just recommended that the investigation focus on the more senior officers!

White had received nominal support from Vivian, but fortunately (in the cause of justice), Carey-Foster was recorded, a month later, as reacting strongly against White’s desire to close down the inquiry. White had to backtrack: Carey-Foster surely learned later the reason for White’s timorousness. Thus White had to show a measure of earnest endeavour again. His interactions with Makins over Maclean’s re-appointment in the Foreign Office in late 1950 indicate that White must have come to an earlier conclusion that Maclean was HOMER. He would not have been involved with Makins if Maclean’s problems had been solely internal disciplinary issues. He also had the case of Burgess to deal with. In the summer of 1950, Liddell had warned the Foreign Office about the dangers of sending Burgess into the sensitive arena of Washington, after his notorious exploits in Spain, and probable dealings with Fredrick Kuh, but he had been overruled. Someone – maybe White himself – had wanted to use Burgess as bait for Philby, in the same way that White needed to entrap Maclean into performing some indiscretion, such as meeting with his controller again.

White had managed to stall the HOMER inquiry long enough, but he could not hold off his colleagues on the team, or the FBI, much longer. The decision to impose surveillance on Maclean in mid-April 1951 must have been an obvious one, in the hope of delivering the crucial evidence of contact with Soviet Embassy officials that would condemn him. Yet White surely had his doubts. He could not rely on bringing VENONA evidence to court, and the only way of securing a conviction would be through a confession. Moreover, if Maclean were faced with evidence solely of a recent contact, to what crimes would he confess? Would his whole career since 1935 be laid on the line? When it came to a trial, would he reveal secrets that MI5 and the Foreign Office would rather stay undisclosed, such as the tolerance of his atrocious behaviour in Cairo, but consequent re-instatement? Might he even betray the secret of the VENONA program, since Philby had made him aware of what it delivered, in an effort to embarrass his inquisitors? Might the pointers from Krivitsky, and details about the ‘Imperial Council’ spy come out in the wash? Would Maclean say nothing about Burgess and Philby? And what use would it be putting Maclean behind bars while Burgess and Philby still roamed free?

When Burgess arrived, and was seen in the company of Blunt, as well as Maclean, White realized that events were coming to an even more critical point. Yet he still had no evidence of treachery on Maclean’s part: the surveillance had not revealed any indiscretions, despite the arrival of Burgess. MI5 had no power of arrest over suspects like Maclean. A continuing mystery about White’s behaviour, however, is his attitude towards Burgess and Blunt. It is now clear that he had had suspicions about Burgess that antedated his time in the United States. If he encouraged Ambassador Franks to send him back [see below], it must have been because he believed that Burgess’s contacting Maclean might help to entrap the pair of them, and to kill two birds with one stone. Yet the investigating group (or, at least, White and Sillitoe) was quite comfortable seeing Blunt have regular encounters with Burgess while not showing any concern as to how Blunt might be acting behind the scenes – namely, meeting with his Soviet contacts. Either that was because that was Blunt’s delegated role, or because White regarded him as being in a quite different camp from that of Burgess, a loyal servant who could spy on the pair, and be trusted.

That scenario immediately throws up another conflict, however – the fact that Burgess and Blunt had in 1949 been in close collusion over the Borodin affair, the mishandling of a Soviet scientist seeking asylum. Was White perhaps ignorant of the special project, one of disinformation to the Soviets, that Liddell was managing under his nose? It seems outrageous, but equally unlikely would be White’s regarding as wholly innocent the collaboration of Burgess and Blunt (and Rees) in Liddell’s scheme. White never referred to that business in what he told his biographers, but he should have asked himself: why would Blunt, in regular contact with Guy Liddell, say nothing about Burgess’s assumed disloyalty in 1949, but then be willing to act in subterfuge against him in 1951? (Blunt’s presence at Waterloo in greeting Burgess is obviously critical to this analysis.)

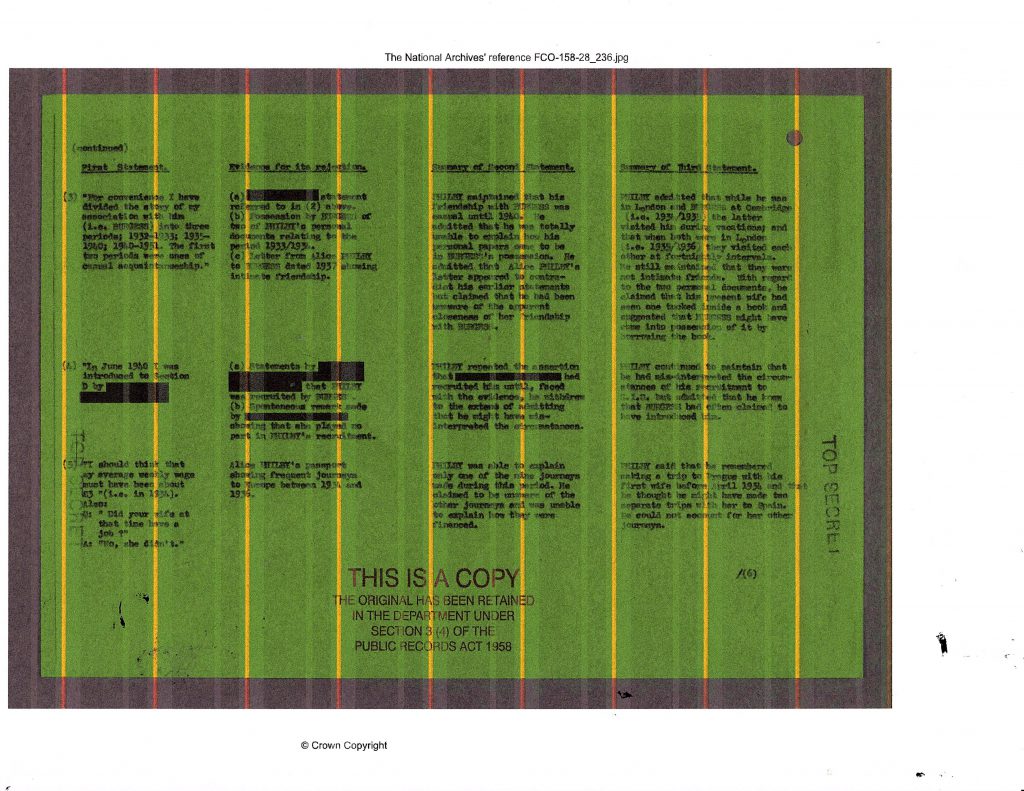

The Perfect English Spy is overall not helpful, being a farrago of deceit and delusion. From what White told his biographer, when Rees informed him of the conspiratorial relationship between Burgess and Blunt going back to 1939, White was much more annoyed with Rees for hanging on to that information for so long than furious at possibly having been betrayed by Blunt. White makes no mention to Boyle or Bower of Blunt’s associations with Burgess and Maclean in May 1951. Disgusted with Rees over his tardy revelations about Burgess, he claims he mistrusted Rees’s accusations about Blunt, too, and professes to be shocked about the revelation in 1963 that Blunt was a spy. He conveniently forgets that he had agreed with Robertson, back in the autumn of 1951, that Blunt should be offered immunity in exchange for disclosing what he knew (or had done), and he blames his inability to understand the strange allegiances of homosexuals for never considering that Blunt, whom he had regarded as an inspiring and loyal colleague during World War II, could have been a traitor.

In any case, White feared for his future – and that of MI5. If MI5 were shown to have been grossly negligent, the Security Service might have been put under MI6’s wing, as had been threatened during the war, and which prospect had been raised by civil servants again recently. White’s career in counter-intelligence would certainly be over. Thus the prospect of having Burgess and Maclean disappear from the scene, if it could be managed surreptitiously and with minimum risk of disclosure of any supportive activity, looked attractive. Moreover, if Philby could be encouraged to remove himself while in America, that would solve another problem. Failing that, prompting the Americans to denounce him by feeding to them a dossier with incriminating information might have the equivalent effect of at least ostracizing Philby, and causing him to join his colleagues.

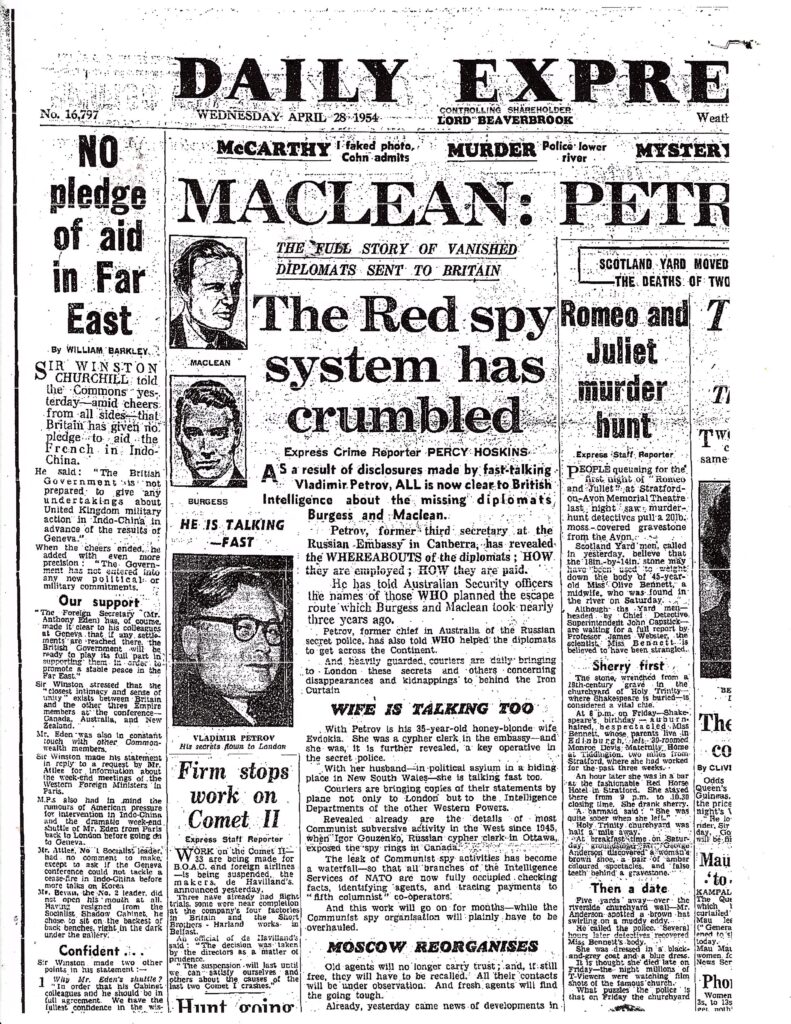

Finally, White was guilty of masking his own mistakes by loading the arch-demon Philby with responsibility for many of the security leaks with which MI5 was involved. When the Petrovs revealed in 1954 that their colleague Razin had pointed to the value for the NKVD of having an agent embedded in the enemy’s counter-intelligence service in London during the last years of the war, White must have known that he was referring to Anthony Blunt. Yet White allowed Graham Mitchell, to whom the secrets of the Burgess and Maclean investigation had not been divulged at the time, to carry the can, with Mitchell disclosing in his internal memoranda at the time that Razin must have been referring to PEACH (i.e. Philby). In that way was White able to deflect attention away from the highly embarrassing case of Blunt. White had seen through Blunt in 1951, but had then buried the case in the hope that interest would die away.

The Cambridge Four:

Meanwhile, what about the motivations of the Cambridge Four? (I exclude John Cairncross from this analysis, as his role as a suspect came to light only after the escape, when incriminating notes were found in Burgess’s flat.)

- Kim Philby:

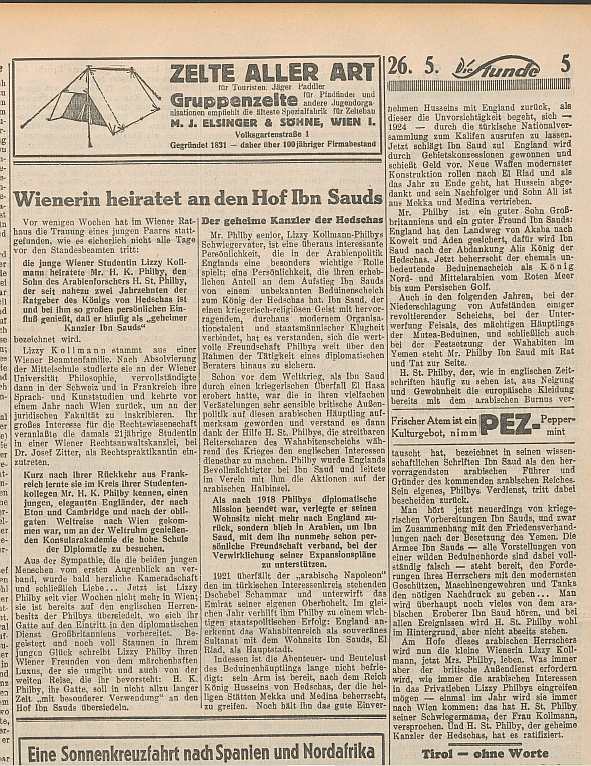

When Kim Philby, on learning in August 1939 of MI5’s invitation to Walter Krivitsky to visit the UK, concluded that the game could very shortly be up, he decided (as has been my thesis) that he had to pre-empt any revelations by the defector about his (Philby’s) role in Spain. He thus decided to admit that he had been sent there as an emissary of the NKVD, but that the Nazi-Soviet Pact had completely destroyed his belief in Communism as a viable anti-fascist force, and he had consequently turned away from Stalin to rededicate himself to the British cause of defeating Hitler. That was a very logical and popular line to take, and the timing was perfect. As part of the arrangement with MI5 (since MI6 was not yet in the picture), he would continue to act as if he were a dedicated agent of the NKVD. (At this time, of course, Philby was considered of negligible value by his bosses in Moscow.) There was a danger, of course. If his Moscow masters suspected his apostasy was sincere, his name would appear on a possible death-list, even though the NKVD and GRU were warier of assassinating native citizens of the democracies than they were of turncoats from the old Russian imperial territories, mostly the ‘illegals’. Such persons would either be recalled for execution in the Lubianka, or would be hunted down in the cities of western Europe.

Thus I have to assume that Moscow knew about – even approved – the plan: Philby met with Gorsky at the beginning of September 1939, and MI6 submitted to MI5 a vetting request on him at the end of the month. Philby was still a war correspondent at this time, however, and it would take short spells in MI6’s Section D, and then the newly established SOE, before he joined MI6 in October 1940. In the first half of 1940, Moscow had ordered all contact with Philby to be halted, and Gorsky was absent until December of that year. Thus 1940 was very much a year of experimentation and fencing, with Philby not too strenuously trying to join MI6, and Moscow very cautious about the integrity of its agent network after the Krivitsky revelations.

Part of the long-term deception with MI6 would involve a commitment to providing information of value to the Kremlin, an exercise that would need to be handled carefully, mediating between items of significance that would not endanger security, and ‘chicken-feed’ that could not be too obvious. Claude Dansey, the deputy to Stewart Menzies in MI6, believed himself to be an expert at this game of misinformation. It gave officers like Philby an excellent cover for their true subversive activities, since they now had a valid reason for meeting their contacts, and in fact needed to do so to reinforce their story. Indeed, defenders of Philby within MI6 through the 1950s referred to such apparent subterfuges to explain why Philby had to meet with dubious characters in order to carry out his ‘double-agent’ role. *

[* I recently re-discovered an extraordinary item in Guy Liddell’s Diaries, which in puzzlement I had annotated a decade ago with two question-marks, but which now seems much clearer to me. It is dated December 18, 1951, and was entered after Liddell had read Dick White’s report on Philby for the Americans, essentially denying that Philby could have been ELLI. The note reads: “Arguable that Philby’s actions in recent years may have amounted to no more than betrayals in cases where he thought they were necessary to safeguard his own position.”]

Would Philby have included any of his collaborators in his scheme? In 1939, Philby had no proven track-record with the NKVD. It seemed unaware of his presence and his contribution, and regarded his wife as a more useful asset. Yet the prospect of neutralizing the influence of Krivitsky, and of Philby’s being eventually accepted for an influential role in Britain’s intelligence services, might well have been regarded as a powerful stimulus. Later in the war, in 1943, it should be remembered, Philby and his cohorts were indeed considered as ‘plants’ inserted by the British to confuse the Soviets with disinformation, as the Modrzhinskaya episodes confirm. Only an increase in the delivery of important confidential material convinced the Kremlin that the spies were indeed loyal to them.

If Philby’s goal had been solely to neutralize the threat from Krivitsky, he might have restricted the group to those whom, in his judgment, the words from Krivitsky might help identify. Yet his knowledge was minimal: the ‘Imperial Council’ spy (i.e. Maclean) was probably the strongest lead in the testimony that Krivitsky provided, but I do not believe that Philby would have known about that incident until he read Jane Archer’s report (something he internalized very closely, as his memorandum in 1949 later showed). No indirect pointers to Burgess or Blunt appear in that report. As far as I can gather, the equivalence of Maclean as a candidate for HOMER was the first indication to White and his colleagues that Maclean may ever have been associated with the Comintern and the NKVD. He had been open about his leftist sympathies at his Foreign Office interview, but he had never been noticed in dramatically subversive exploits – unlike Philby.

The evidence that Philby brought Blunt and Burgess into his cover-story is slightly more compelling, but pinning down the issue of timing is more complex. It would have made sense for the trio to be united about any deceptions. The fact that Blunt was smoothly introduced into MI5 in the summer of 1940, despite his Communist background, is telling. Burgess was a law unto himself: his behaviour was so outrageous, and his articulation of left-wing, and anti-American, views so brazen that no one could really believe that he could be a serious agent for any secret service, let alone the NKVD. Modin wrote that, when Burgess and Blunt returned to the UK from France at the end of August 1939, having learned of the Nazi-Soviet pact, they met with Philby, and had a long discussion. They concluded by re-affirming their commitment to the cause of the revolution, and Philby may well have shared his concerns about Krivitsky at that time.

Thus, in 1949 and 1950, when the clouds started rolling in on Maclean as the prime HOMER suspect, Philby might have believed that there was a firewall between his triad and Maclean. He had not seen Maclean since 1940 (or so he claimed: that assertion is belied by evidence in Blunt’s Personal Files). Having alerted Moscow to the threat, he seemed happy to let matters take their course. If Maclean had to be exfiltrated, so be it. It would not cast any further suspicions on him. As far back as November 1949, he had been preparing his cover by reminding his colleagues in detail of Krivitsky’s disclosures: he even pointed out to Mackenzie that the investigation was probably wasting too much time on lower-level staff. This was an astonishingly bold – but disloyal – gesture, showing that he was willing to sacrifice his friend to save himself. That constituted a weird twist to the Forsterian creed of loyalties. Philby did not selectively leak his thoughts to a confidant: he carefully wrote them up, knowing that they would gain broad distribution. In so doing, he knew that Krivitsky’s comments about a ‘journalist in Spain’ would inevitably gain fresh attention, and probably turn the spotlight on him. He must have been confident that White, who had been party to his volte-face, would come to his defence if necessary. But White clearly did not want to touch the matter.

(Incidentally, Philby’s account of these events is predictably unreliable. In My Silent War, he gives a very accurate and telling analysis of the failures of the cabal to follow up the Krivitsky leads, but presents his suggestion that the investigation could be accelerated as occurring only when the rescue plan was being developed in the spring of 1951, thus conveniently overlooking his contribution of November 1949. His masters at the KGB, controlling his text, would not have been too happy if they had learned that Philby had at that time been prepared to sacrifice such a valuable asset to save his own skin. It is perhaps also telling that it was in that same month of November 1949 – according to Christopher Andrew – that Maclean asked his controller to be relieved of his espionage duties.)

Arthur Martin responded to Philby’s memorandum by immediately claiming that the possibility of that identity had been ‘borne in mind since the beginning of the inquiry’, but the observation is not obvious from the evidence. Moreover, there is no track record of any follow-up before Dick White’s bizarre suggestion, on January 31, 1950, that the project should be handed over to the FBI. Thus the investigation continued, even though Carey-Foster, out of his depth, diminished the importance of Krivitsky’s hints. Yet it is inconceivable to me that Philby’s reminders, and the retrieval of Krivitsky’s testimony from the vaults, did not prompt some earnest inspection and consideration from the members of the team – especially those in MI5. And the reports of Maclean’s antics in Cairo (though not broadly distributed) should have caused some logical connections to be made.

Indeed, in March 1951, Philby renewed his accusations, clearly considering Maclean’s cause as lost, as he provided direct indications of Maclean’s possible guilt to Patterson, MI5’s representative in Washington, as a way of deflecting attention from himself, and reminding everyone of his loyalty. (Not only did he bring up the ‘Imperial Council’ spy allegation again, he also pointed out Maclean’s visits to New York.) Far from enabling Burgess’s return to London, as a way of warning Maclean, he would have done much better to keep him in Washington until the smoke cleared. If Burgess’s account can be trusted, Philby’s final instructions to him when he left Washington were ‘Don’t you go, too!’, but they should be seen more as a humorous gesture. Philby surely would have reacted in horror if he learned how closely Burgess consorted with Maclean in London, and how the pair were watched. Indeed, he was dramatically shocked when he heard that both of them had fled.

- Guy Burgess (and Goronwy Rees):

I include a discussion of Rees here, alongside Burgess, because the relationship between the two is one of the most provocative aspects of the case. Burgess had had his confrontation with Goronwy Rees the very next day after the Philby-Blunt-Burgess confabulation in September 1939 (described above), for the record of which we have to rely on Rees himself, of course. Burgess started by defending the pact, as if he hoped he might be able to confide in his friend, and have him join the trio in the scheme. Yet, when Rees showed dismay and disgust with Burgess’s behaviour, telling him that he wanted nothing to do with the Comintern again, Burgess apparently backtracked. As Andrew Lownie wrote: “Burgess, in order to ensure Rees wouldn’t betray him and Blunt, pretended to his friend that he, too, had become disillusioned by the Nazi-Soviet Pact and had given up his illegal work for the Communist Party.” (Stalin’s Englishman, p 103) That scenario would fit in with the idea that Philby had successfully brought just Burgess and Blunt into his conspiracy.

On the other hand, the very bizarre activities shared by Rees, Burgess and Blunt in the Borodin affair, under Guy Liddell’s stewardship, in 1948 and 1949, raise further puzzling questions. If we assume that Liddell was working with honest intentions, and that he was not a scoundrel like the rest of them, we have to judge that Liddell believed that the three of them were still loyal servants of the Crown. Furthermore, if this exercise had indeed been one of disinformation, and passing on useless secrets about the penicillin process to the Soviets, Rees’s joining a firm after the war to do business with Moscow would not have been a disreputable act, as Robertson and other officers in MI5 judged it, but a necessary front set up with the assistance of MI6, for whom he was working part-time. Liddell would have hardly laid out the details of the project so openly in his diaries if he had truly been involved in defying US instructions, and in assisting Moscow. Thus the episodes simply show, in my opinion, how gullible Liddell was, and how poor his judgment of character, and also how disinformation exercises can go so horribly wrong when you cannot rely on a crucial part of the intelligence infrastructure.

Yet perhaps it would have meant a most damaging outcome for Rees, since his failure to alert Liddell of his suspicions of Blunt and Burgess during the Borodin project would have been thrown severely in his face when he met Liddell on June 1, 1951. It was one thing to admit to having had suspicions about Burgess that had lain dormant for twelve years, but quite another to participate without demurral (alongside Blunt) in a Soviet deception exercise as recently as two years before the events of 1951. One can understand why Rees felt compelled to stand down from his denunciations of Blunt after his clandestine meeting with the deputy director-general, and one could even sympathize with Dick White when he expressed his contempt for Rees to his biographer. Rees was severely squeezed, and he nursed his grievances for years without ever admitting the shabby role he had played in the affair.

The interpretation I put on the Borodin affair is that Burgess must at that time have considered that Rees was ‘safe’, sympathetic to Burgess’s true role, and at no risk of betraying him. Thus the pre-planned visit to Sonning would not have been a madcap exercise to ensure Rees’s loyalty, but something undertaken as a way of exploiting Rees’s connections with MI6. Yet it is difficult to gauge Burgess’s motivations or fears as he prepared his trip home to the UK. He needed new employment, and his negotiations with Michael Berry of the Daily Telegraph suggest that he had long-term plans in the UK. It appears that he did not worry about being caught up in the Maclean investigation, probably because he had always behaved so outrageously, and got away with it. There had been fresh misdemeanours in the United States, but nothing specifically tied to espionage. He had always behaved in a scandalous manner, but it had not previously affected his career. He was not being asked to resign because of suspicions of disloyalty.

Nevertheless, he pitched himself into the maelstrom. He must have alerted Hewit to his homecoming, and he probably suggested that he be accompanied by Blunt to welcome him in London. His free association with Blunt thereafter would suggest that he believed that Blunt was in the clear, and not under suspicion. Had Blunt been told by Liddell of the surveillance involved on Burgess and Maclean? It is not impossible, but Burgess did not appear to be deterred by it, engaging in nothing more blatant than resuming a familiar friendship. And if he learned of the watchers from Maclean himself (as most accounts indicate), he carried on as if everything were normal. I drew attention last month to the feeble way in which Burgess’s actions have been chronicled in the couple of biographies of him.

At some stage Burgess must have concluded that, if Maclean’s escape were being arranged, he would have to accompany him. It was probably after the lunch at the Reform Club on May 15. Whether that was because Moscow had ordered him to accompany Maclean, or because Maclean had convinced him that their true home was now Moscow, as their roles had been snuffed out, or because Burgess had come to that decision off his own bat will probably never be known. Another explanation could be that, in order for ‘the British authorities’ to allow Maclean to escape unmolested, they insisted that Burgess be part of the deal as well.

- Anthony Blunt:

Why was Blunt on-site to welcome Burgess when he arrived at Waterloo Station on May 7? Whatever the circumstances, it would seem an unnecessarily bold and risky action. Blunt must have considered himself invulnerable, but who put him up to it? How did he learn of Burgess’s imminent arrival? If it was Modin who had learned of Burgess’s itinerary, he would surely have urged caution. Modin’s recollection is customarily untrustworthy. He claimed that he ‘was waiting anxiously’ in London – but does not define exactly what he was waiting for. When Blunt met with him the day after Burgess’s arrival, Modin wrote that Blunt told him that Burgess had ‘just arrived in London’, suggesting that it was news, and that Modin would not have known about the details of the voyage. But Blunt then continued: “Homer’s about to be arrested. MI5 has focused on three men, and now it seems they have a lead which points straight to Maclean. It’s only a question of days now, maybe hours”.

But that is nonsense. If Burgess had been on an ocean-liner for a week or so, he would not have been able to gather and impart such hot news. Blunt could have told Modin about the search being cut down to three men several weeks beforehand. He was in regular contact with Liddell, although Liddell does not specifically refer to his meetings with Blunt before the escape. While it was true that an interrogation might unveil the whole network, Maclean was not about to be arrested. Further lies followed: Blunt was said to have claimed that Maclean was then in such a state that Blunt was convinced that he would break down the moment MI5 questioned him. But Modin had just written that Blunt had heard nothing from Maclean since their last contact in April. Modin never challenged Blunt, however, on why he had gone out of his way to be seen in Burgess’s company. It consisted of really poor tradecraft. Modin could not really have believed at this stage that MI5 considered Burgess harmless, and that any meetings with him would be regarded as innocent. And then Modin compounded his error by arranging (so he said) a meeting with Burgess himself.

Modin admitted that Burgess then had to become the intermediary with Maclean, as Blunt could no longer contact him in safety. Yet that statement implies that it had been safe beforehand, even though Maclean had been under intense scrutiny for some months, and under close surveillance since the middle of April, during which month Maclean and Blunt had met. It all suggests that Blunt had been sent to Waterloo by White and his posse, in order for Blunt to put Burgess at his ease, and for Blunt to learn the news from America. (MI5 was probably told of Burgess’s itinerary by Blunt himself.) After all, the Watchers were there to notice the encounter. Blunt could have explained it to Modin as part of his deception game, where he pretended to be working as a consultant to help the Security Service. Given he was no longer an employee of MI5, it was pushing the idea a bit far to suggest that maintaining contact with Soviet officials was still an important part of his cover, but maybe Modin was not smart enough to work that out. In any event, White at this stage appeared to have every confidence in Blunt’s loyalties to use him as an informant and go-between.

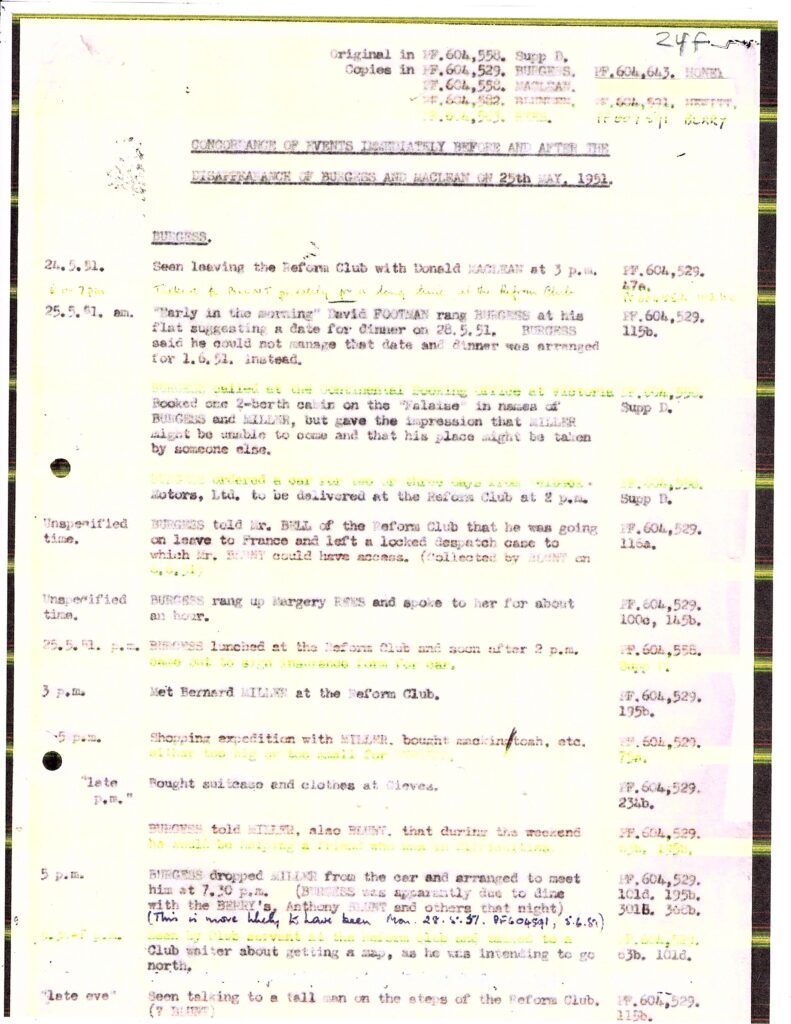

The recently released Personal File on Blunt reveals a remarkable annotation, in KV 2/4700, at sn. 24f. The Concordance of Events compiled after the ‘Disappearance of Burgess and Maclean’ appears in many places, but the version in Blunt’s file contains a hand-written addendum concerning Burgess that reads as follows: “24.5.51 6 or 7 pm: Talked to BLUNT privately for a long time at the Reform Club”, with a reference to PF 604582 [Blunt’s file] 1112bc. Cross-referring to KV 2/4720, one finds that the evidence was not provided until 1972, by a Squadron-Leader Richard Leven. Leven, who had been waiting to pay Burgess some money he owed him, had seen Burgess and Blunt in a huddle on a sofa for ‘a few hours’ on the evening of May 24. Officer Maconachie of K3 (who appears a little confused) added: “The information that BLUNT and BURGESS had a long conversation in the Reform Club in the early evening of either day [i.e. May 24 or May 25] seems to be new to us.”

Why Leven did not volunteer this information to the authorities immediately afterwards is not apparent, while the apparently retrospective ‘enhancement’ of the archival report consists of a markedly dubious practice. (When the future director-general of MI5, Stella Rimington visited the seedy Leven in Weston-Super-Mare a couple of months later, she elicited the fact that Leven had shortly afterwards spoken to a reporter from the Daily Express, as well as to a Foreign Office acquaintance, about the events at the Reform Club. In his memoir, My Flying Circus (2006), Leven elides over the whole episode, suggesting that he never returned to the Reform Club after his complaint to the Club’s secretary about Burgess’s homosexual advance on him was ignored. Leven does however offer some useful observations about Burgess and Blunt, which I shall return to some time later.) Yet one should not immediately accept Maconachie’s claim that this information was new to MI5. Burgess was being watched closely, and it would seem impossible that such a lengthy discussion could have been missed. No one picks up on the significance of this discussion, however. Blunt did not mention it, and none of the inquisitors who immediately targeted Blunt as a possible conspirator of Burgess’s ever thought to question him about it.

Other evidence is damning. Blunt had been spotted with Burgess at the Reform Club the previous day, as KV 6/145 confirms. Were the Watchers called off on the Thursday, as a note suggests? Then why did they record Burgess’s meeting with Pollock and Miller at the Reform, and then moving on to dine with them both on that same evening, which must have clashed with the ‘couch’ engagement? Did no one notice this anomaly? Did White manage to convince everyone to steer clear of any Burgess-Blunt interactions at the time? In 1956, when Goronwy Rees’s article in the People had stirred up fresh interest in Blunt, Ronnie Reed and Courtenay Young tried to interrogate Blunt again, but Blunt was asked only about his brief meeting with Burgess on the morning of May 25. None of the several meetings or telephone discussions between Burgess and Blunt – including Blunt’s welcoming him at Waterloo – was brought up. [Reed’s and Young’s performance was characteristically inept, which must be fodder for later analysis. Rees had poignantly been provoked to supply his information to the People from his anger that the government inquiry had overlooked Blunt’s relationship with Burgess at the time, and that all blame had been placed on Philby.]

Thus Blunt found himself in an extraordinary, outwardly perilous, but internally safe, situation. He was trusted by Dick White to engage with Burgess without the risk of his being contaminated himself. He was not under surveillance, and he thus felt confident in carrying out his meetings with Modin. He knew that he was trusted at a very personal level by Guy Liddell. Modin did not feel threatened as he knew that Blunt’s true loyalties were to the Soviet Union. Blunt was therefore in a perfect position to help negotiate the outcome that would salvage some prestige for Moscow while allowing MI5 and the Foreign Office to solve the problem of its unarrestable espionage suspects. After the escape, as Guy Liddell’s diaries reveal, the newspapers quite freely described Blunt’s close relationship with Burgess, but the journalists did not pick up the story aggressively enough, and MI5 was spared.

- Donald Maclean:

Maclean is the most mysterious of the Four, since he committed nothing to paper about the events except for the unearthly press conference in Moscow in 1956, when the words were certainly dictated for him. I suspect that the stories of his hypercharged emotional state in April and May 1951 have been exaggerated or distorted, since many of the indications from those he had dealings with in the last two weeks of May indicate that he had reached a level-headed recognition that his days in the United Kingdom were numbered, and that he would be spending the rest of his life in Moscow – where, incidentally, he adapted much more successfully than did Burgess and Philby, even though he underwent a number of alcoholic binges that required hospitalization. It is highly unlikely that Burgess was appointed to accompany him because of his frail mental state.

The visceral reaction to the fact that his treachery had been revealed occurred in Cairo in early 1950. Since then he had walked a slow road to some sort of ‘recovery’, with psychiatric help that may have been undertaken as a necessary step to maintain a front. There had been, in the autumn of 1950, a diagnosis of ‘repressed homosexuality’, which Maclean may have borne without challenge if it provided him with some cover. His wife was quoted as supporting the notion that he had a homosexual (or bisexual) streak, but that may also have been part of the legend. (Cyril Connolly later gave confident evidence that Macean had had homosexual tendencies, but his testimony was overall very muddled. In January 1958, however, Sir Steven Runciman told Courtenay Young that Burgess and Maclean had conducted ‘a roaring affair’ up at Cambridge.) After the escape, Blunt would ‘confirm’ to Liddell that Maclean was a homosexual, thus helping to confuse the issues surrounding Maclean’s personality and motivations. Outlandish incidents still occurred, such as his outburst that he was the ‘English Hiss’ in the middle of March 1951, but he was cool enough to recognize the signs that he would soon have to face the music.

The tales of tensions in the relationship between Melissa and Donald may well have been overstated. He had confided in her his commitment to the communist cause right at the start of their relationship, and she had supported his actions. Yes, she may well have been shocked by her husband’s wild behaviour in Cairo, but it did not destroy the marriage. Despite her late pregnancy, she approved of Donald’s flight, and she always planned to join him in Moscow when the circumstances were right. Donald had presented a calmer face to his friends as the arrangements for his escape matured, and, in particular, Anthony Blake’s observations concerning his friend when they met on May 24, and the document that was passed on to the FBI, would tend to confirm that he was reconciled to the outcome. (An anonymous transcript of this letter was handed to MI5 by the US Embassy on June 14, but the Foreign Office judged that it was a poor fake: see sn. 97 in FCO 158/3.) Maclean may, however, have been amazed at Burgess’s perilous sense of timing as they raced their way along the roads of south-east England to make their rendezvous with the Falaise.

Most accounts indicate that Maclean picked up the fact that he was being surveilled, and informed Burgess of such. Yet multiple rumours, and informal statements from insiders, suggest that he had colleagues within the Foreign Office (Talbot de Malahide, conspiratorially) or Michael Wright (innocently) who may have kept him up to date with the progress of the project to investigate him. Jackie Hewit may have meanly identified Frederick Warner as a close intimate of Burgess’s in the Foreign Office who had performed a similar service. None of these relationships can really be construed, however, as being significant in the execution of the exfiltration plan – and certainly not as a ‘last-minute’ tip-off about an interrogation that was not just about to happen.

‘The British Authorities’

Consider what the authorities performed, or allowed to happen. First recall, however, that i) MI6 was not represented on the team investigating the Washington Embassy leaks; ii) MI5 and the Foreign Office could not control the appointments made by MI6, such as the transfer of Philby to Washington; iii) while in Washington, Kim Philby had access to the proceedings of the HOMER inquiry; iv) while Dick White had suspicions of Philby’s loyalty, he could not prevent Philby seeing the results of the cabal’s investigations; and v) Philby had his strong supporters and allies in MI6, including his bosses Easton and Menzies.

- While, in early 1950, evidence pointed strongly towards Maclean as being HOMER, the team stretched out the project, conceding only at the end of March 1951 that the search had been conclusive.

- Despite the warnings from MI5, and internal concerns, in 1950 both Burgess and Maclean were appointed to sensitive positions in the Foreign Office when disciplinary proceedings against each were considered. (Home Secretary Morrison was one who declared that they should both have been dismissed.)

- After Maclean was appointed head of the American desk at the Foreign Office in October 1950, highly sensitive reports were withheld from him.

- The official conclusion that Maclean was HOMER was made the day after Burgess was ordered back to London by Ambassador Franks.

- The Watchers of MI5 were prepared for Burgess’s arrival, and they noticed him being met by Jackie Hewit and Anthony Blunt at Waterloo Station on May 7, 1951.

- Close surveillance of Maclean had started on April 23, and it continued up until his departure on May 25. Surveillance on Burgess was less intense, and apparently selective, as his meeting with Modin (if indeed it did take place) was not observed; nor was his long session with Blunt on the evening of May 24.

- By all accounts, the surveillance of Maclean was so obvious that he noticed it, and thus probably became wary about making any incriminating contacts. Burgess likewise noticed that he was being watched, but it did not inhibit him.

- If the intention of the surveillance had been to capture contacts with a member of the Soviet Embassy, it failed to observe the one or two incidents in which Burgess was involved.

- The authorities appeared to have no interest in the meetings between Burgess and Rees, and Burgess and Footman, both MI6 officers. The exercise completely ignored the activities of Anthony Blunt, ‘consultant’ to MI5.

- The surveillance did pick up unusual events (such as the booking of berths on the Falaise, and the hiring of a rental-car, by Burgess) that should have alerted MI5 as to the intentions of the couple they were watching.

- Dick White prepared his dossier on Philby, to be given to the FBI, before the escape of Burgess and Maclean.

- Approval was sought from Foreign Minister Morrison to question Maclean as soon as the escape plan was finalized.

- No one in the Foreign Office or MI5 seemed to be disturbed by the subsequent non-appearance of Maclean in the office on May 26 (Saturday morning).

- Likewise, the response to Maclean’s failure to arrive on his normal train on May 28, and non-appearance in his office, was received with apathy. Carey-Foster and Makins even considered that he might have been granted another day off.

- The telephone surveillance carried out at the Maclean homes turned out to be a poisoned chalice. It could not be turned off without undermining the whole exercise, but the evidence it provided, involving suggestions of Maclean’s absence over the weekend of May 25-27, as well as fake indications of his proximal presence, should have caused acute embarrassment.

- The cabal spuriously interpreted the telephone activity (and inactivity) at the Maclean residence during the weekend of May 26-27.

- If MI5 did request Special Branch to keep watch on the ports, the officers failed to think through the implications that, as they admitted, they could not prevent subjects on whom no arrest warrant had been issued from leaving the country.

- If Maclean was indeed identified when he boarded the Falaise, no immediate report on his presence was made, or, if it was, it was apparently ignored.

- The scramble to involve foreign Police departments (especially the Sûreté) in tracking down the ‘Missing Diplomats’ was equally flawed, as the authorities had no legal authority to arrest the innocent parties.

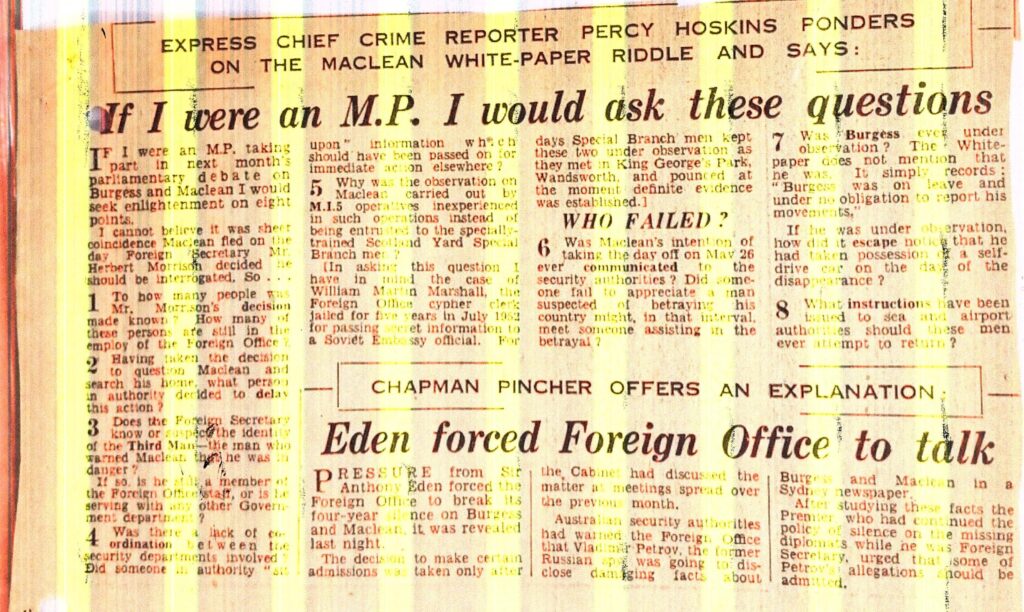

- The cabal (primarily Carey-Foster and Reilly) misinformed the press by claiming that Maclean was due to be interrogated on May 28.

Some of these events may be coincidental. The circumstances of Burgess’s recall are enduringly provocative. It would appear that the cabal had no control over the rationale and timing of Ambassador Franks’s decision, but the evidence shows that the decision to send Burgess back to London had nothing to do with his speeding offences. The complaint from the Governor of Virginia arrived on March 14, 1951. Franks was in England between March 10 and March 28, and could certainly have conferred with his Foreign Office colleagues about Burgess’s status. If the cabal had requested that Burgess be disciplined, and required to return to the UK, Franks had other reasons for reprimanding him, given his obstreperous behaviour at the Philby household, for instance. Thus, if the British authorities wanted to package both Burgess and Maclean up in a ‘defection’ project, having Burgess back in London, consorting with Maclean, would have been a sensible option.

The material in the FCO files is informative. Despite any overt recognition that Burgess may have been a topic for discussion while Franks was in London, soon after his return to Washington, on April 7, Franks wrote a long letter to Ashley Clarke, the Chief Clerk at the Foreign Office, that came to a somewhat reluctant recommendation that Burgess be sent home. The reason was not because he was in disgrace, but because the Ambassador felt that ‘his usefulness here is small and that with this speeding trouble on top of the rest of the story he is more of a liability than an asset to us’ (FCO 158/182). Franks cited Burgess’s slipshod and superficial research, and a laxity towards security matters, but specifically denied that any serious personal or political offence was involved in his decision – thus rather dishonourably ignoring Burgess’s insulting behaviour at the Philby party in January, when he drew a disgusting caricature of the wife of William Harvey, the CIA officer. It is noteworthy that the speeding offences come up as a kind of incidental clincher for the decision, but are by no means essential parts of the argument. On the other hand, given Burgess’s reputation and track-record before he was sent to Washington, the sudden realization by Franks that Burgess was more of a liability than an asset, is unconvincing in its timing. It is perhaps not surprising that Burgess objected to his punishment if the case against him had been presented in that way.

MI5’s Dysfunction

Communications and cooperation were not a strength of MI5. Director General Sillitoe was not highly regarded by his subordinates, and he was thus not told everything that was going on. He held regular staff meetings, but no formal records are available. The position of Deputy (held by Liddell) was always an awkward one: in order to represent his boss while the latter was away, he would have had to imagine what Sillitoe’s policy would have been. That could not have been easy, since Sillitoe sometimes had to cable in for instructions when on the road. Liddell seemed to be occupied with political issues, and ‘special projects’. The relationship between Liddell and White had probably begun to deteriorate in the late 1940s. Liddell’s secret project with Borodin in 1948 and 1949 was probably undertaken without White’s knowledge. It seems that White did not confide to his former mentor all that was going on in the HOMER investigation. After all, he had indicated to Malcolm Muggeridge three years back that he was effectively running the show.

For example, part of Liddell’s diary entry for April 11, 1951, indicates that White has only very recently informed Liddell of progress in the hunt for a Soviet spy in the Washington Embassy. It runs as follows:

It is now thought that this individual may be identical with the Foreign Office agent reported by KRIVITSKY as supplying information on Imperial Policy back in 1937. KRIVITSKY said that he was the son of some titled individual. Recent ACORN material served to narrow the field; this material had been in the possession of the Americans for a long time, but for some reason has only just reached us. There are two people who might possibly fill the bill; one, Donald MACLEAN and the other, John RUSSELL. MACLEAN is now head of the American Department in the Foreign Office and is the brother of Nancy Maclean who was formerly in this office.

Liddell has clearly been left out of the discussions, despite the fact that he had formerly been the expert in Soviet counter-espionage, and had even interviewed Krivitsky at length. Moreover, White has deceived him over the nature of the project, claiming that the Americans have withheld information, when GCHQ had been working on the VENONA (= ACORN or BRIDE) texts for years, had specifically taken over control of the HOMER traffic in January 1949, and had been withholding details of its successes from the NSA! Only in April does Liddell learn about Maclean’s identity – some weeks later than did Philby through his ability to review progress in Washington. Moreover, Liddell oddly comes up with a name, Russell, who was not part of the triad identified in early April, namely Maclean, Gore-Booth and Wright. It is apparently news to him that Maclean is now head of the American Department, when that appointment had been made six months beforehand. It is clear from Liddell’s diaries that neither Sillitoe nor Liddell knew about White’s little scheme of revealing damaging information to the FBI about Philby. At this stage the withholding of information was probably only a power-play by White, but his opinion of Liddell soon deteriorated.

The main source of discord was Blunt, but it was not over Blunt alone that the two officers disagreed. In his diary entries after the escape, Liddell consistently expresses his trust in Blunt, never believing that he could be a traitor, despite his known history of ‘intellectual’ communist sympathies. He is disparaging about Burgess – a ‘skunk’, but continues to show sympathy for Philby, from his immediate reaction after the events (“There is no doubt that Kim Philby is thoroughly disgusted with Burgess’s behaviour both inside his house and outside it.”) Liddell was broadly unsympathetic to White’s initiative to blacken Blunt in a formal report to the FBI at the end of June. When Liddell returns from leave at the beginning of October, he is apparently saddened to discover that the case against Philby is ‘much blacker’, and he records confidently that Philby was not the man mentioned by Gouzenko and Volkov. (The former, correctly so: the latter certainly not.) He shows his naivety by stating that it was inconceivable that Tomás Harris or Blunt would not have come forward and exposed Philby if they had known he had been a Soviet spy in SIS! And such ruminations lead up to the infamous note of December 18 that I recorded earlier, concerning Philby’s subterfuges as a ‘double agent’.

During the autumn of 1951 White was more involved with Philby than he was with Blunt, and he delegated the examination of Blunt’s record and statements to Robertson. Yet he was impressed enough by what Robertson reported to him (which may well have gone beyond the rather bland statement of Robertson’s that exists in the archive) to want to recommend that Blunt be given the immunity deal. He knew that he would have to get it past Liddell, given his colleague’s seniority and close relationship with Blunt. As I have written elsewhere, White and Liddell passed each other in the night, and the proposal somehow got lost in the fog. In retrospect, when Liddell was dead, White would convey to his autobiographer the suspicion that Liddell might have been party to the conspiracy to exfiltrate Burgess and Maclean, in such a way to shift responsibility while rather disingenuously indicating that such a plot had indeed existed. Liddell’s reluctance to pursue the Blunt deal would convince White that it was imperative that he himself take over the helm when Sillitoe retired. As he surely did.

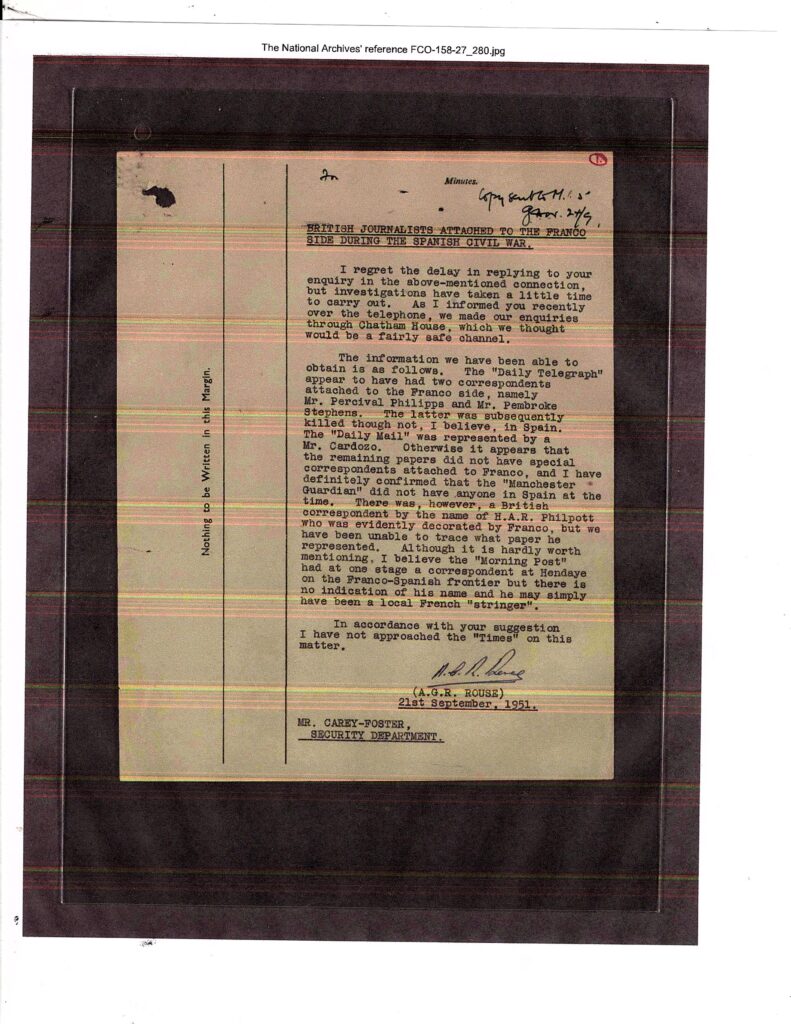

Carey-Foster and the Security Department

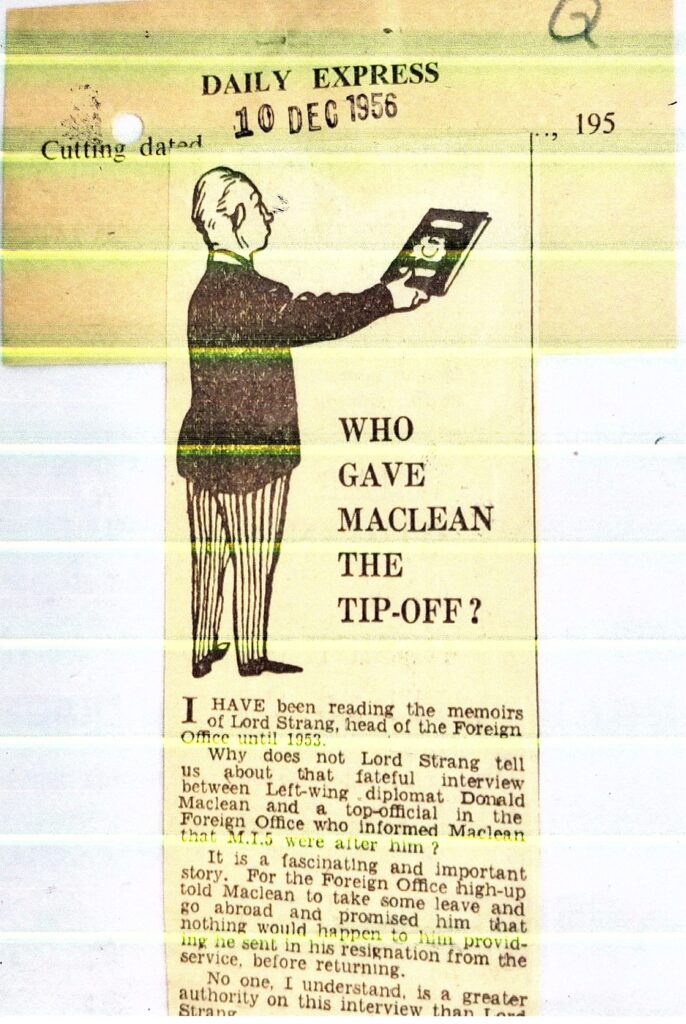

One dimension of the controversy that has not received enough attention is the role of George Carey-Foster and his team of security officers in their attempts to break down the close and collegial atmosphere of the career Foreign Office ‘diplomats’. This aspect is important because of the press attention given during the early 1950s to the notion of an insider in the Foreign Office giving a ‘tip-off’ to Maclean. As I have explained, this was a red herring, since the authorities had skillfully conflated the ideas of a generic warning about the investigation into Maclean (which certainly went back to April, at least) and that of a last-minute alert (which was based on a convenient untruth, and was in any case irrelevant, since the plans had been sprung). Yet it is important because of the fact that the Security Department itself was infected.

Not much has been assembled about the activities of Carey-Foster’s ‘Q’ Section. I am indebted in many ways to an article by Daniel Lomas and Christopher Murphy, published in Diplomacy and Statecraft in August 2023, titled The Foreign Office ‘Thought Police’: Foreign Office Security, the Security Department and the ‘Missing Diplomats’, 1940-1952. While ‘Thought Police’ is a strange way of describing, presumably, what a vetting procedure is (it derives from Arthur de la Mare, who succeeded Carey-Foster after the de Malahide interregnum), the article goes deeply into some aspects of the topic, but it is surprisingly thin in much of its coverage, and, astonishingly and inexcusably, completely overlooks the role of Lord Talbot de Malahide. As I have indicated beforehand, de Malahide played a very equivocal part in the proceedings, and was even suspected by Malcolm Muggeridge and Lord Killanin of being a Soviet agent.

Carey-Foster, who had been appointed to the position in 1948, struggled with his responsibilities. His function was presented as being ‘advisory’ rather than ‘executive’. The career officers resented this intrusion into their practices and habits, which were based on camaraderie and trust. Strang did not heed sound managerial principles of having Carey-Foster’s recommended disciplines incorporated into the chain of command, and thus Carey-Foster and his team were frequently treated with disdain. Early in the Maclean investigation, Carey-Foster had challenged White for his attempt to disband the exploration, probably because his was an MI5 voice, not a Foreign Office one. There had also been territorial disputes between Carey-Foster and Liddell over responsibilities for investigating the Embassy staff when the leakage was first detected. By the time of the disappearance of the ‘diplomats’, however, Carey-Foster had clearly been cowed into the party line adopted by the cabal, namely that the Foreign Office had not been betrayed by careless chatter or devious betrayal from insiders, but by the machinations of an outsider, Philby.

His conscience probably troubled by a sense of failure and guilt, Carey-Foster struggled after the events of 1951. In the immediate aftermath, in early June, his comments and reactions, as listed in FCO 158/3, show him to be confused and out of his depth. He comes across as week and vacillatory, and his inexperience is also evident from the later escape post mortem, when the Foreign Office was debating on how to handle the propaganda aspects of the events (in FCO 158/26). Yet he maintained an interest in the business, since, after his retirement (or removal) from the Security post, he wrote rather apologetic memoranda from Rio de Janeiro and Warsaw that are available in the FCO/158 series. What is astounding about the account from Lomas and Murph, however, is that they completely ignore the interregnum when de Malahide took over as acting Security Officer before the arrival of Arthur de la Mare (whom they identify as Carey-Foster’s successor). Their confusion is manifest by an important sentence in their article: “As the defection of Maclean and Burgess revealed, colleagues in the Foreign Office already knew a lot about the conduct of the two men, which was finally brought to the attention of the Security Department when the scandal broke”.

To depict Carey-Foster as uninformed about the previous misdemeanours of both Burgess and Maclean is erroneous. He may not have been told at the time of Maclean’s return from Cairo about his behaviour in Egypt (although Lomas and Murphy misrepresent the dates here, claiming that the details started to reach the Security Department in ‘in March 1950, nearly ten months after his recall’, when they must mean March 1951). On the other hand, they clearly point out that Carey-Foster had been overruled by MI5’s Guy Liddell when he wanted to prosecute Burgess under the Official Secrets Act in January 1950, and he underwent resistance from MI6 as well as senior Foreign Office staff when he pursued his case. Nevertheless, to ignore the familiar and long-standing acquaintanceship that one of Carey-Foster’s officers, de Malahide, had with both malefactors, and which he declared soon afterwards, is simply lackluster and indefensible.

Does all this matter? From the standpoint of the overall plotting of the cabal, not very much, perhaps. It did not change the outcome of events at all, since the cover-up had been underway for a while, and Maclean may have had other well-wishers in the Foreign Office who alerted him to the investigation, which would have been of no surprise to him. On the other hand, it adds enormously to the critique of the leakiness and unstable nature of the Foreign Office itself. It was not simply that some friends of Maclean might have harboured misplaced sympathies, and warned him to get away: it was the fact that a probable Soviet ‘agent of influence’ was embedded in the Security Department itself, and may have been performing untold damage in other parts of the intelligence services before then. Furthermore, he may have been protected by his old school chum Patrick Reilly, who was as complicit in the lying to the outside world about the affairs of May 1951 as was Carey-Foster. No doubt Lomas and Murphy were carefully steered away from such incriminating material by some of the ‘advisers’ whom they acknowledge in a footnote, but they showed a lack of entrepreneurialism in not looking closely at the relevant archival material themselves.

A Possible Sequence of Events

Before the official conclusion from GCHQ, on March 30, 1951, that Maclean was surely HOMER, Dick White realized that the writing was on the wall. He persuaded his colleagues in the Foreign Office that, if Burgess were ordered to return to the UK, they could combine their operation by including a second agent about whom White held strong suspicions, and who might collaborate with Maclean in setting up clandestine meetings with the Russians. White thus exploited the visit by Ambassador Oliver Franks during March 10 to 18 (had he in fact been summoned on such a pretext?) to request that Burgess be sent home under a disciplinary cloud. Franks returned to Washington to discover the speeding incidents, which helped to strengthen what was a more work-related dossier of low performance. Burgess was thus ordered home, although he took his time. Probably alerted by Patrick Reilly, who had worked for Stewart Menzies as his Personal Assistant in World War II, Valentine Vivian flew out to Washington at the end of March to warn Philby about the unsuitability of boarding Burgess – a little late.

Meanwhile, the surveillance on Maclean was approved in early April. The Washington Leaks Committee continued to meet and ponder. They confirmed the HOMER hypothesis, and shared their findings with Patterson in Washington, who in turn showed them to Philby. On April 7, James Robertson of B Division pointed out the equivalence of Maclean and the ‘Imperial Council’ source. MI6 was being kept abreast of the progress, partly by Arthur Martin of MI5, but, at a higher level, no doubt by Reilly. Gore-Booth was officially eliminated as a suspect, for geographic reasons, on April 11. The cabal did not yet want to inform the FBI of its suspicions, believing it needed to have a stronger game-plan in place, but also because they were scared of the news leaking out. Strang was temporizing: he insisted no information be given to the Americans, and wanted Gore-Booth’s name to be added back to the shortlist. On April 13, Roger Lamphere of the FBI asked about the Krivitsky report, indicating that the organization was moving on similar lines. MI5 started its detailed investigation into Maclean’s past on April 20.

MI6 was drawn more closely into the project on April 23, when Robertson and Carey-Foster agreed to share information with a few MI6 officers, including Valentine Vivian. On April 28, Philby had his final briefing meeting with Burgess. The FBI was in the meantime demanding swifter action. On May 1, Arthur Martin flew to Oslo to interview Michael Wright, who had been head of Chancery in Washington. He confirmed Maclean’s incriminating absences in New York, but was incredulous at the probability of Maclean’s being a Soviet spy. On May 5, Martin was able to record the fact of Maclean’s ‘communist outburst’ at a party in January. In Washington, Patterson was concerned about secrets given to the FBI escaping to the notoriously loose-lipped State Department. Partly because of the pressure from the Americans, the team had considered on May 4 that Maclean should be interrogated ‘within a fortnight’. It is clear that the cabal at this time considered interrogation a necessary step, even though it had then gathered no incriminatory evidence from the surveillance. Moreover, it appears that no decision about the form of the interrogation, or who should conduct it, had been made. And then Guy Burgess arrived at Southampton on May 7.