Introduction

This bulletin, the first of two, or possibly three, dedicated to Roger Hollis, started out as a ‘B’-class (‘Businesslike’) report, but soon developed ‘A’-class (Advanced’) tendencies. I discovered a wealth of intriguing new facts concerning Jane Archer and the organization of MI5 at the time war broke out, facts that have been in the public domain for over two decades, but which have apparently been overlooked. I have thus included a deeper analysis of the phenomenon, since it reflects sharply on the role of Hollis. I have overall sacrificed digestibility in the cause of compendiousness, as I believe that it is important that a full story as possible concerning Hollis is recorded.

I have set out to describe Hollis’s responsibilities and achievements during the war, first covering his time within MI5’s B Division until the re-organisation of June 1941, and then his work thereafter in the new F Division until the summer of 1945. In November of 1941 Hollis replaced John Curry as head of F Division, and he led the group for the remainder of World War II. I do not believe that a proper account of Hollis’s role has been written anywhere, and, in that absence, Chapman Pincher’s distorted story has lain as the default, and has probably influenced public opinion in a notorious fashion. In his authorized history of MI5, Christopher Andrew wrote a few paragraphs about Hollis’s contribution, but hardly did justice to the complexity of Hollis’s charter, or his activities. I exploit accounts from various sources: this is not an integrated profile of the MI5 officer, but the process does enable the formulation of some patterns of behaviour and policy.

Confirmed Pincherites should read the whole article: others may wish to jump to the Conclusions and then decide whether they want to study the supporting material.

Contents:

Chapman Pincher’s Mythology

What the Histories Say:

‘Defend the Realm’

John Curry’s ‘Official History’ of the Security Service

F Division Reports (KV 4/54-58)

Nigel West’s ‘MI5’

Other Sources

Guy Liddell’s Diaries

Other Archival Sources

David Springhall

The Communist Clamp-Down

Engelbert Broda

George Whomack

Claud Cockburn and ‘The Week’

Conclusions

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Chapman Pincher’s Mythology

I use as a springboard for my analysis Chapman Pincher’s revised version of Treachery (2012), in order to record and comment on his representation of Hollis’s role and actions, since it has received an unprecedented and unjustified degree of respect in pseudo-academic circles. For example, in the infamous 2015 Institute of World Politics investigation into Hollis, chaired by the FBI’s Ray Blatvinis (see https://fbistudies.com/2015/04/27/was-roger-hollis-a-british-patriot-or-soviet-spy/), the Australian Dr. Paul Monk was introduced in the following terms: “Over the past two years or so he has carefully extracted all the salient facts about Hollis from two major sources. The first is Treachery, a monumental examination of the Hollis case written by the late British journalist Harry Chapman-Pincher [sic]. The other is Defend the Realm authored by Dr. Christopher Andrew, Chairman of the Department of History at Cambridge University and the Official Historian of the BSS.” The consideration that the largely spurious account by Pincher unerringly contained ‘salient facts’ represented such a gross error of judgment that it undermined the whole proceedings. I thus outline here the primary anecdotes that Pincher relates concerning Hollis, as well as the broad allegations against him, annotating them with facts and statements from other sources to highlight the discrepancies.

- Hollis’s Induction

Pincher correctly uses much ink in describing Hollis’s rather unusual path into MI5 – the abandoned degree course at Oxford, his seeking his fortune as a journalist in China and his subsequent employment in that country by British American Tobacco, his passage through the Soviet Union on leave in 1934, his eventual return to the UK because of tuberculosis, a period of unemployment before joining BAT again, his marriage to Eve Swayne and an enigmatic visit to France at the end of 1937, a stimulating lecture he gave to the Royal Central Asian Society, and a possible introduction to MI5 by Major Meldrum.

The problem is that Pincher’s account is riddled with so much speculation – in China he was friendly with Arthur Ewert, Agnes Smedley and (possibly) Ursula Hamburger (Agent Sonia) and Richard Sorge, and was thus, in Pincher’s mind, recruited into the GRU network. Every time that Hollis is associated with a communist or left-winger, such as in his friendship with Claud Cockburn, that fact confirms for Pincher Hollis’s true affiliations. Each time Hollis disparages communism (such as in his criticism of the state of Moscow), or shows patriotic loyalties (in letters home), that phenomenon is judged as part of his disguise. Pincher has made his mind up that Hollis was recruited, either in Oxford, or in China, or in Paris, to the Comintern cause, and thus began his long career as ‘ELLI’.

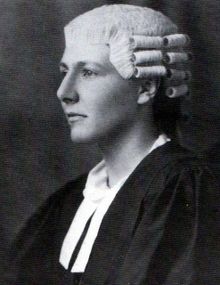

There seems to be some confusion as to exactly when Hollis was recruited by MI5, and for how long he was on probation. The tennis-match at Ealing, arranged by Jane (Kathleen) Sissmore, did probably occur in August 1937, and Hollis was asked to submit his qualifications as a potential MI5 officer. Dick White told Pincher that Hollis ‘did not volunteer any special knowledge of international communism at any stage of his recruitment’. Pincher characteristically remarks: “Perhaps wishing to conceal his past association with notorious people like Ewert and Smedley, and possibly Sonia, he remained silent, as he certainly did about his connection with active British communists such as Cockburn.” On the other hand, White and Sissmore might have been impressed by Hollis’s ability to ingratiate himself with such persons without betraying his true allegiances. In any event, Peter Wright told Pincher that Hollis was rejected, first by MI5, and then by MI6, before Jane Sissmore convinced MI5’s director-general, Vernon Kell, to accept him. It is difficult to verify that account, yet Sissmore definitely took Hollis under her wing when he became a regular employee of MI5 in the summer of 1938. A 1938 organizational report has Sissmore listed as B4a, with Hollis, somewhat surprisingly, already given the same designation.

- Hollis in B4

Despite his less than auspicious background, Pincher has Hollis becoming, in 1940, ‘the driving force in his speciality, quickly being recognized as MI5’s expert on communism and the prime understudy to Jane Sissmore in that respect’ (p 71). Somehow, ‘driving force’ and ‘Roger Hollis’ do not sit well in the same sentence: Pincher appears to contradict himself by going on to write how dull and reserved Hollis was viewed by his colleagues at this time. In addition, Hollis had been with the service for only two years, and Pincher openly recognizes Sissmore (in fact now Jane Archer) as the premier expert on Communism, while understating the knowledge of Dick White and Guy Liddell in that sphere. John Curry specifically named Jasper Harker and Liddell as the experts. Yet an organizational listing, from December 1939 (viewable at KV 4/127), lists Hollis as the sole officer in charge of B4a, with the Misses Cotton, Creedy, Ogilvie and Wilson working for him. What happened to Jane Archer?

That KV 4/127 file reveals another startling fact. By December 1939, Jane Archer appears (assisted by Miss McNalty and Miss Small) as the officer in charge of a mysterious unit B14, an entity which I cannot find mentioned in any of the histories. Indeed, the first Krivitsky file (KV 2/802) shows her signing herself as B14 as early as September 1939, in a memorandum to Jasper Harker and Gladwyn Jebb. Thus she had been transferred from her B4a post well before the Krivitsky interrogations in January 1940 – probably in preparation for his arrival, so that she might work on the project investigating Soviet espionage. John Curry mentions this scheme in his history, without ever identifying B14. Strangely, Liddell makes no mention of the creation of B14 in his diaries, although an entry for October 13, 1939, records a discussion he had with Archer after she had visited Percy Glading in prison. On November 16, he writes, rather clumsily, that ‘Jane has got a new man at the Russian trade Delegation that she would like to get at’. That gentleman may have been A. A. Dostschenko, who, as Jane reported on November 24, was found distributing a questionnaire to an informant. Yet, in a note soon after, on November 29, Liddell would appear to be instructing Jane to step into what was domestic territory, namely the investigation of ‘applications for employment in restricted occupations from the Reading area’ – the notorious ‘Russo-German case of F. R. Brown’, who may or may not have been the future England cricket captain of that name. Liddell had also been watching carefully the developments in the Krivitsky case, and shows that he discussed his interview with him with Jane on January 30, 1940. Yet he does not describe her intense involvement, or what the charter of B14 was.

All this would strongly indicate that Archer had a far more serious mission in covering the risks of Soviet penetration than did Hollis, who, with only a year’s experience in MI5, was left in charge of less dramatic domestic issues, such as inspecting Brian Simon’s passport papers, or (after the war started) handling policy on the export of newspapers. Moreover, in December 1939, Hollis was in charge of B4a only – not of B4b, which was led by the more serious student of Soviet intrigues, Milicent Bagot. For example, Guy Liddell’s diary entry for September 17, 1939, shows that B4b (not B4a) was responsible for assessing how many Soviet citizens might have to be interned. An entry for October 9 shows that B4b was likewise charged with investigating the Czech communists in residence. (Extraordinarily, at the end of 1939, all the officers in the numerous B units – up to B18, with Curry as B15 – seem to have reported directly to Liddell: there was no intermediate head of any entity named ‘B’. Dick White was merely the leader of a two-person band in B2!) Hollis was thus never ‘the prime understudy’ to Sissmore (actually ‘Archer’) in 1940, because they did not work together after September 1939.

Yet Jane Archer, shortly after completing her report on the Krivitsky interrogations, was mysteriously moved over to managing the Regional Security Liaison Officers (RSLO) in the summer of 1940. Hollis, the only officer in B4a, thus did not take over her job at this time: what happened to the B14 operation is not clear, but the dissolution of Archer’s work has very ominous overtones. Neither Curry, nor West, nor Andrew ever acknowledges the creation or dissolution of B14. (Andrew’s first mention of B4 after the 1930s, even, is of its surveillance teams trailing Fuchs in 1949!) One might expect Andrew and West to have overlooked B14, given the lack of archival material, but Curry was there at the time, and he had a professional interest in its activities! Why the coyness? The fact that the existence of a unit that was specially set up to investigate the intelligence from Krivitsky has been suppressed and excised from the authorized history of MI5 is damning. White probably subsumed B14’s role into his own department after the reorganization (an idea that I shall investigate below), but the archival record is woefully bare.

Pincher is thus completely misguided about Hollis’s true role, but he sets about his assault anyway. In a passage that is characteristically vague about dates he accuses Hollis at this time of being responsible for failing to give rigorous advice to the Security Executive about the probably seditious publications of his communist friend Claud Cockburn. Pincher writes: “The Security Executive had repeatedly asked MI5 for the necessary evidence for a prosecution, but Hollis had insisted that he could not provide any that would stand up in court. This may have been true, but it had also been against his interests that his past association with such a notorious Communist activist might become known. Eventually the war cabinet decided to suppress both The Week and The Daily Worker, with or without evidence, and the file on the event shows that Hollis was definitely the MI5 officer required to deal with the case.”

This account is a distortion of what happened, suggesting that Hollis was an influential advocate, acting alone. While the fresh interest in Cockburn started well before Hollis had been given sole control of B4a, in early 1940 several senior MI5 officers weighed in with their views on Cockburn and The Week. (Since the writer W.J. West expands on this story with archival references, I shall explore the events surrounding Cockburn later in this piece.) Hollis admittedly may have mis-stepped in his handling of Cockburn, and in his negligence over George Whomack, but Pincher attributes this behaviour to the obstructionist actions of a penetration agent rather than the inexperience of someone feeling his way. In any event, Pincher asserts that Archer’s eventual sacking for impertinence, in November 1940, immediately elevated Hollis as the ‘acknowledged expert on communism and Soviet affairs’ (p 99). Where he acquired this expertise throughout 1940, and who acknowledged him in this role, are not explained by Pincher, who has failed to recognize the organizational realities of that year, and has given a totally erroneous picture of MI5’s set-up.

iii) Hollis in F Division

Pincher then grossly misrepresents the re-organization initiated by David Petrie in June 1941, when a new Division F was established under John Curry, responsible for ‘Subversive Activities’, namely domestic challenges to the system from disaffected groups. Hollis was an assistant-director under Curry, responsible for a small team (F2) covering ‘Communism and Left-Wing Movements’, which in turn had one officer tracking ‘Policy Activities of C.P.G.B. in UK’ (Clarke, F2a), ‘Comintern Activities generally, Communist Refugees’ (F2b, immediately filled by the capable person of Milicent Bagot), and ‘Russian Intelligence’ (Pilkington, F2c). Pincher was excited by Curry’s careless and imprecise statement in his official history that F2c was responsible for ‘Soviet Espionage’. While Curry pointed out the successes in the cases of Oliver Green, David Springhall, and Desmond Uren, Hollis was never charged with assuming Archer’s responsibilities, namely a serious re-assessment of the possible implications of the Krivitsky revelations, the structure and polices of the NKVD and GRU, and the whole phenomenon of deep penetration agents.

Pincher then writes that ‘the deference quickly paid to Hollis as the Soviet expert greatly increased his influence’, although he never describes how Hollis showed his expertise, nor does he identify who the subjects paying deference were. He notes that, when Hollis replaced Curry as head of F Division in October 1941, his access and authority were increased still further. Pincher states that Hollis then brought in his ‘Oxford University drinking companion’, Roger Fulford to help him. Yet Curry’s organization chart for July 1941 shows that Fulford was already responsible for F4, covering Pacifist movements such as the Peace Pledge Union, and thus reporting to Curry, not Hollis. By 1943 Fulford has moved on. Pincher then criticizes Hollis for failing to monitor properly, or restrain, the more than a dozen KGB (actually NKGB) and GRU officers active in London at the time, although how he was supposed to do that with a combined team of probably only three officers and other personnel in F2 in 1941 is not clear. Pincher claims that Kemball Johnston was hired at this time, but the April 1943 chart shows a weakened F2 organization with Clarke still covering F2a, and Shillito now responsible for both F2b and F2c.

That MI5 leaders were not seriously trying to bolster a force against Soviet espionage through F Division was reinforced by a written statement that Dick White made to Pincher in 1983, namely that ‘Hollis and F Division had never been responsible for Russian [sic] counter-espionage, which had always been part of B Division’ (p 102). White was partially correct (as Curry confirms in his official history), if by ‘Russian’ he meant initiatives starting from overseas, as opposed to those native to the CPGB. Yet that supposition was making very fine distinctions, and would have opened a whole field of hazards. Moreover, White, now the Assistant Director to Liddell for B Division, was indeed the officer heading both B1 (Espionage) as well as Hollis’s old section B4, now called ‘Country Espionage’, including B4a. B4a was the unit responsible for non-Nazi counter-espionage, i.e. investigations into espionage deriving from ‘individuals domiciled in the United Kingdom’: White no doubt wanted to keep some measure of control over the function. That did not mean, however, that the task of countering Soviet espionage was being carried out with aplomb. For instance, by June 1943, B4b, charged with investigating espionage in Industry and Commerce, still headed by J. R. Whyte, had been reduced to a small band covering ‘Escaped Prisoners-of-War and Evaders’. (By then, of course, its original function may have well been passed on to Hollis.) Yet the failure to grapple with the Soviet espionage threat was a source of much discussion between Liddell and Petrie as the war progressed. Archival evidence shows that Petrie and Hollis discussed the potential Soviet menace, as did Petrie and Liddell, and Liddell and Hollis, but White is largely absent from the conversation.

The fact that Hollis was not responsible for handling the broader and more sinister aspects of Soviet intrigue does, however, not fit in with Pincher’s view of the world: he argues, somewhat bizarrely, that he does not attribute this ‘misconception’ of White’s to his failing memory, but instead to his willingness to accept responsibility for any incompetence himself, as part of the theme that his protégé needed to be protected. If anything, White’s assertion was a criticism of his boss, Liddell, who was responsible for all of B Division during the war. Certainly, after June 1941, when the Soviet Union was an ally (albeit a difficult and temporary one), the task of countering direct Soviet espionage – as opposed to domestic subversion – was largely buried, and White in particular wanted to shield the potentially embarrassing business of MI6’s enabling of Sonia’s marriage to Beurton, and of assisting her passage to Britain, from prying eyes.

- Hollis, Fuchs, Sonia & Springhall

Yet Pincher continually beats the drum that records Hollis’s failure as the wartime Soviet counter-espionage officer, as if he had been responsible for allowing the Cambridge spies to purloin so many documents (p 103), in the years when they ‘perpetrated their worst crimes’ (p 108). Hollis was reputedly lax in allowing Sklyarov and Kremer to meet Klaus Fuchs in Birmingham in August 1941, since, even though new to his job, he had been involved in the takeover procedure for his new assignment for several weeks (p 134). Pincher admittedly would appear to be making a shrewd observation when he points out that D. Griffiths, in F Division [actually F2b], had noted that the source Kaspar had reported that Fuchs was ‘well-known in communist circles’, and Pincher follows up by claiming that Hollis took no action (p 136). Yet this report was made as late as October 10, and Griffith [sic] judged that they could not put off any longer the requests from the Ministry of Aircraft Production for permission to hire Fuchs. The final approval was given by Joe Archer (AI1d) a few days later, on October 18.

The truth is that the investigations had been carrying along at a much higher level by then. For example, MI5’s request to the Chief Constable in Birmingham, C. C. H. Moriarty, for information on Fuchs’s political activities, was dated August 9. It went out, however, under the name of Director-General Brigadier Petrie, signed by Milicent Bagot, as if both Curry and Hollis were out of the loop. (The item is designated “F.2b/DG’.) Moreover, the request to the ‘Watchers’ (Robson-Scott in E4) for information on Fuchs, again under F.2b/DG, was sent to Robson Scott in E1a on August 9, and Bagot and Petrie had to wait over two months for a reply, namely the report from Kaspar. Hollis was thus not the lead officer on the project, and his name never appears in the archive during these months. For him to insert himself in the project at that late stage, when his boss’s boss had been personally involved, would have been inappropriate. Pincher’s slur is simply unjustified. More at fault was perhaps Petrie, for managing the investigation himself, but not taking action during the long delay. What Petrie was doing, delving down to F2b to collaborate with Milicent Bagot early in his career as Director-General, remains a mystery.

Other archival material tells us that Hollis did complain about the recruitment of communists to the Tube Alloys project, but was overruled by the Ministry of Supply and the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. The Ministry was not concerned about political persuasions if those holding them could help in the war effort against Hitler. Remarkably, Pincher then cites Hollis’s absence, in November 1941 (i.e. immediately after his promotion, but a date that is highly questionable), because of a bout of tuberculosis, as a reason that Moscow Centre broke contact with Fuchs for a while, as they were no longer receiving the ‘regular assurances of safety’ from their man in MI5! How Hollis would have known about Fuchs’s current security, or how he would have delivered such messages of comfort to the Embassy under normal working conditions is not explained by Pincher. By January 1943, when Fuchs’s naturalization papers were being considered, agent Kaspar had changed his tune: Fuchs then bore a ‘good personal reputation’ and was considered ‘a good fellow.’

The next major theme is Hollis’s close collaboration with Ursula Beurton, née Kuczynski (agent Sonia). By some weird reasoning, Pincher interprets the way by which Sonia came to service Fuchs as proof that she had been posted to Oxford from Switzerland for the purpose of supporting someone else – Hollis, who had been working out of Blenheim after the transfer from Wormwood Scrubs (p 158). Shortly after Sonia moved to Avenue Cottage in North Oxford, in October 1942, Hollis returned to duty after his convalescence from tuberculosis. Thus her ‘task of servicing two major suppliers in the area’ was substantially eased, according to Pincher. He then blames Hollis for his negligence in not following up Hugh Shillito’s suspicions concerning Sonia’s possible spying, or the discovery of a large wireless set at the Laski residence where she was staying (pp 160 & 161). Pincher claims that Shillito actually passed up his message, expressing doubts about Len Beurton’s testimony, through his boss, Hollis, to the deputy Director-General. Yet Hollis was, in Pincher’s eyes, solely responsible for ignoring Sonia’s ‘traitorous activities’.

The problem is that Pincher completely distorts what happened. Shillito’s letter, available in KV 6/41, is not addressed to the deputy director-general (who would have been Jasper Harker at the time), but to Major Ryde, the Regional Security Liaison Officer in Reading. His information was gained by virtue of a joint interrogation of Beurton carried out at MI5 alongside a Mr. Vesey and a representative from MI6. D. I. Vesey, who worked for B4b, has already appeared on file, as he had been on the Beurton case all through the summer, and had arranged the interview referred to by Shillito – as his letters and memoranda prove. Thus Dick White’s group was indeed (moderately) active in pursuing cases of possible Soviet espionage, in this case a person who had earlier been tracked now arriving from abroad – even if he was a British subject. In March, 1941, Shillito (then B10c), whose interest in Ursula Beurton had been piqued by her recent arrival to the country, alerted Ryde to that event, and also passed her file to B4b as the natural home for it. So it appears to confirm that an active cell of tracking potential communist threats had endured in B Division, as White claimed, and F Division had not assumed in toto the various B sections, contrary to what Curry claimed in his official history at the end of the war [see below].

What is also interesting, however, is that Vesey, in his memorandum of October 20, 1942, that records the interview with Beurton, does describe the presence of an officer (name redacted) from MI6, but makes no mention that Shillito was present. Clearly, the investigations of Shillito into domestic subversion, and Vesey, into international espionage, had crossed because of the Kuczynski-Beurton shenanigans, and Vesey was anxious to put Shillito in his place. Of course, if the high-ups had wanted to pursue the investigation of the Beurtons, they would have insisted upon it, and they would not have allowed Hollis to display any negligence by showing no action. Moreover, Pincher completely ignores the role played by Vesey and B4b in these incidents.

Pincher next uses the success over the Springhall arrest and prosecution in 1943 to make another wrong conclusion. “Springhall’s conviction should have finally convinced Hollis and his colleagues that Russian intelligence was prepared to use flagrantly open communists as agents”, he writes (p 164). In fact, Springhall’s exploits were firmly in opposition to Moscow policy, which ruled that CP members should take no part in espionage. The NKGB was not at all happy about the way that the CPGB had dragged itself into notoriety. Yet Pincher again blames Hollis for being a major influence in the failure to investigate such characters as Philby, Maclean, Blunt, Klugman, Fuchs, the Kuczynskis, Norwood and Kahle. Apart from the fact (as I have indicated elsewhere) there were special considerations with each of these menacing personalities, it is unlikely that the combined wills of White, Liddell, Petrie and Menzies would have caved in to Hollis’s presumed appeals for inactivity. And Pincher again misrepresents the dynamics, by suggesting that Burgess and Blunt must have experienced extraordinary thoughts when they drank socially at the Reform Club with Hollis, ‘the man they knew to be responsible for detecting Soviet [sic] spies’ (p 167).

- Hollis and Section IX

The next episode in the saga is Hollis’s apparent shrewdness in recommending that MI6 establish a new Section, Section IX, to ‘intercept and possibly decipher’ wireless messages being transmitted between Moscow and the CPGB headquarters’, especially since ‘certain London members of the party [were] known to be operating illicit transmitters and receivers from their homes’ (p 169). This statement is a distortion of the truth. Apart from the obvious fact that, if CP members were known to have been operating radio sets from their homes (an illegal activity), they would instantly have been picked up, Pincher throws in a completely irrelevant observation that this initiative coincided with a USA attempt to interpret KGB [sic] transmissions between New York and Moscow. (That would been the first few weeks of the VENONA project, and it has nothing to do with the case.)

It is difficult to know what to make of this. Pincher cites Curry’s official history as the source. Indeed Curry does give Hollis a large amount of credit for encouraging the formation of Section IX. He also reports (p 358), that there was one isolated incident of detected wireless traffic involving James Shields of the CPGB, and a former member, Jean Jefferson, who operated from her home in Wimbledon, and that they were being watched. Curry states, however, that there were much broader reasons for MI6’s needing to have a section dedicated to Soviet counter-espionage at the time. In any case, such a technical challenge was the province of the Radio Security Section (RSS) and GC&CS: MI6 would not have brought any fresh skills or insight to the operation.

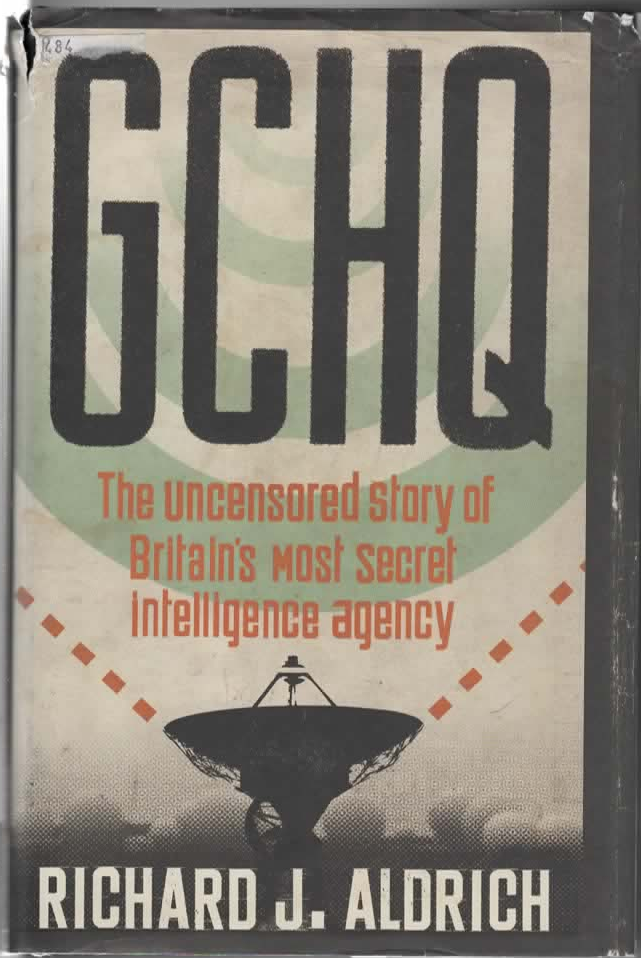

Pincher also cites Richard Aldrich’s book GCHQ, suggesting that Aldrich had recorded a meeting between Alastair Denniston, ‘the head of the forerunner of GCHQ’ [wrong: Denniston had been ousted by then, and was working on Comintern traffic in London], and ‘a senior member of the RSS’ (actually, our old friend Ted Maltby) to discuss ‘the interception of KGB messages being sent from Soviet agents in various parts of Britain to the Soviet Embassy’ (p 169). If true, that would have been an immense shock to all concerned. But Pincher got it wrong. What Aldrich wrote about was ‘the interception of certain apparently illicit transmissions from this country which have been “DF-ed” [direction-found] to the Soviet Embassy” (p 79). These were messages transmitted from the Embassy, not to it, and were part of the ISCOT project that later revealed information about Soviet post-war plans for Eastern Europe. Moreover, transmissions could not have been characterized as being targeted to any particular location such as the Soviet Embassy. They were available in the ether for anyone in suitable range to pick up. Pincher shows his technical ignorance, mixes up three entirely different projects, perhaps deliberately and out of mischief, and posits the absurd notion that there was a large number of Soviet spies transmitting undetected across Britain.

Yet Pincher’s whole chapter is amplified into a paeon to the ‘two-headed colossus’ of Philby and Hollis working in partnership to thwart any attempt by the British intelligence services to identify and prosecute Stalin’s agents. One of their apparent successes needs to be cited in full (p 170). “A particular significant aspect of this remarkable situation, which was to last throughout the war, ensured that any intercepted messages to and from illicit radio operators in Britian, including Sonia’s, would automatically be passed by Phliby’s section to Hollis for possible action. The messages would be in code, and it was Hollis who would decide whether to have them deciphered or not.” This is utter nonsense. If such a volume of messages had been picked up, RSS and MI5 would have been obsessed with discovering whether any of them derived from German agents first. An undeciphered message would not betray the allegiance of its source –unless the authorities had already pinpointed the location of its sender by direction-finding. Such messages would never have been sent to someone like Hollis, and he would never have been able to make any decisions about their importance if they were undeciphered, anyway! This is all pure fantasy on Pincher’s part. Pincher claims that Hollis was so proud of his achievements in this MI6 initiative that he apparently described it as his ‘best, personal wartime shot’ in his post-war account of his unit’s history (p 175). That report can be seen in KV 4/54. Hollis never mentions radio interception at all, let alone his unique contribution to MI6’s innovations.

vi) Hollis and the Quebec Agreement

The dual themes of ‘Hollis as ELLI’, and his collaboration with Sonia, are amplified in Chapter 23, ‘A High-level Culprit’, (pp 184-190), which is dedicated to the notion that Sonia betrayed to Stalin the secrets of the Quebec Agreement of September 1943. This is a very involved saga, and I spent much ink analyzing it in my bulletin of over eight years ago, at https://coldspur.com/sonia-and-the-quebec-agreement/. I shall thus not examine it again here, merely summarizing that the case for Sonia’s being the source of any leaks rests on very flimsy evidence, including some reported Soviet archives that are unavailable, and hence inscrutable. It also assumes a very dubious timeline concerning departures of scientists to the USA, and the release of further nominated experts to follow, as well as some highly questionable claims about Sonia’s movements when she was heavily pregnant. Nevertheless, Pincher chooses to portray the incidents as further evidence of Hollis’s guilt (and Hollis at this time, inevitably ‘was regarded as MI5’s atomic expert’ – p 186), while his narrative is riddled with so much speculation concerning events that might have happened, and persons who ‘could have known’, that his argument turns out to be very flabby indeed. Again he emphasizes how Sonia had been sent to the Oxford area specifically to service this important GRU agent. The lack of any direct pointer to Hollis either in Sonia’s memoirs, or in GRU files (which have, incidentally, not been released in any form) is, in Pincher’s twisted mind, attributable to the high level of security that was attached to this supermole. If Hollis ever wrote anything in favour of prosecuting communists, it was a cover for his real designs, claims Pincher. And if there is no evidence for any of his clandestine assignments, that is because they were all carefully covered up.

- Hollis and Fuchs’s Move to the USA

Pincher would appear to be on firmer ground in his criticism of Hollis’s negligence in allowing Fuchs to proceed to the United States in November 1943, in the chapter 24, ‘Calamitous Clearance’, pp 191-195). His account runs as follows: Fuchs received his visa for transfer on November 22, 1943, and told Sonia that day about his planned departure, which ‘eventually’ was scheduled for December. On November 17, MI5 had been asked if there was any objection to an exit permit, and Hollis had taken charge of the case himself. He reported specifically to an American questionnaire that Fuchs was politically inactive and that there were no security objections to him. On January 10, 1944, Hollis compounded the deception of failing to reveal Fuchs’s communist background by recommending that the dishonesty be continued. In fact, Fuchs had arrived in the USA on December 3 (thus nullifying Pincher’s earlier observation about the scheduled sailing), and on January 10, the Ministry of Supply informed MI5 that he might be required to stay on in the USA longer than expected. Hollis immediately approved such an arrangement, and noted that ‘it might not be desirable to make any mention to the US authorities of the earlier allegations of Communist affiliations’.

Hollis’s coup, according to Pincher, was not only to ensure Fuchs’s entry into the heart of the Manhattan Project, the operation to build the atomic bomb, but also to place the seeds of bitterness on the part of the Americans when they found out about Fuchs’s treachery a few years later. “The fact that Fuchs had been able to betray so many secrets because Hollis had repeatedly ensured his security clearance is regarded by MI5 as pure coincidence”, writes Pincher (p 194). He adds that, early in 1944, Churchill, unimpressed by MI5’s performance, reacted by giving vetting responsibility to a ‘secret panel of Whitehall officials’, and that Hollis insisted, in a memorandum to David Petrie, that all such cases should be referred to him. (As with all of Pincher’s references, no source is given.) Thus (according to Pincher) Hollis’s communist watch was totally ineffective.

The truth was somewhat different, as Mike Rossiter explained in The Spy Who Changed the World, and as I summarized in Misdefending the Realm. Unfortunately, Rossiter does not offer precise references, and his attribution of memoranda is a little awry, but the details can be found in the relevant Fuchs file at KV 2/1245. The sequence of events in the latter half of 1943 is as follows: on July 7, Miss Bosanquet in F2b contacted the RSLO (Captain Dykes) in Birmingham to ask for his opinion of Fuchs. Dykes replied promptly (although his letter is not on file), and Bosanquet wrote again on July 14, stating that ‘as he [Fuchs] has been in his present job for some years without apparently causing any trouble, I think we can safely let him continue in it’. Now that judgment should probably not have been delegated to a junior officer (what kind of ‘trouble’ was she expecting?), and it was the RSLO who immediately challenged it. He wrote the very next day, saying: “Surely, however, the point is whether a man of this nature who has been described as being clever and dangerous, should be in a position where he has access to information of the highest degree of secrecy and importance?”, and he concluded his objection by suggesting that Fuchs should be referred to the Police. Well said, Captain Dykes.

Bosanquet, oddly, continues the exchange, pointing out to Dykes that, in his earlier (unfiled) letter, he had indicated that he had already alerted the Police, since he had then informed her of what the opinion of the local constabulary had been. On July 28, she wrote again, indicating that she had been the officer who had dealt with Fuchs’s application for naturalization earlier that year (May), and that nothing had been found to his detriment. She diminishes the Communist claim as coming from the German consulate in Bristol, and thus being possibly tarnished. (That was a very cloistered and outdated judgment, since Fuchs’s communist activities had been reported from other sources, including Kaspar. It is not clear why Miss Bosanquet was entrusted with this task.) She strongly hints that Rudolf Peierls is the person who has testified to the important service that Fuchs is providing for the country. On August 30, Bosanquet concludes that nothing can be done about Fuchs, and on September 4 Hugh Shillito in F2c agrees, stating that he does not ‘regard Fuchs as being likely to be dangerous in his present occupation’. A fellow named Garret concurs.

The next we learn is that, on November 18, MI5 offers ‘no objection’ to a request for approval for Fuchs’s overseas mission on behalf of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. A scribbled and undecipherable couple of letters appears below the stamp ‘No Objection’, but a large stamp, as well as the rubric at the bottom of the document, indicates that it is D4a1 (probably Lt. T. Nesbitt) who has made the judgment, D4A being responsible for travel control, visas and exit permits. The formidable Milicent Bagot, on November 22, records her surprise that Fuchs, ‘who has now applied for an exit permit’ [my italics] is now a British subject, indicating that the approval of his naturalization process had not reached her desk. On November 28, Michael Serpell (F2a) approaches Garret (now shown to be D2) as to whether any period has been set on Fuchs’s visit to the USA, suggesting that he believes that Fuchs has not departed yet. Yet the extraordinary fact is that Fuchs had departed on November 11, as Rossiter reports, under conditions of haste and secrecy. The approach to MI5 for approval for Fuchs’s mission was all a sham. Pincher’s account was well off the mark.

In this fashion another obscure section gets in on the act. On November 29, Major Garret of D2 (Naval Security Measures) informs Serpell that Fuchs’s name was not on the original list of workers going to the USA, and thus must have been added at the last minute. A few weeks later, however, on December 6, Garret seeks confirmation, and writes to Michael Perrin at the DSIR, inquiring whether Fuchs should be considered as one of the party of ‘workers’ who have gone to the USA. (It seems as if MI5 has not been informed of the details of their departure: if there was any expression of outrage from anywhere in MI5, it has been suppressed.) Perrin replied awkwardly two days later, confirming that Fuchs was indeed now in the USA, but regretting that he could not give a firm statement as to the longevity of Fuchs’s mission. He personally believed that Fuchs would remain in the American organization. By January 10, 1944, Perrin appears to have been more alarmed. He confirms that Peierls wants to keep Fuchs out in the USA, but now does raise the security angle, about which the Americans are most concerned, and he expresses some urgency in gaining from MI5 its opinion of Fuchs, and any risk associated with him.

A quick telephone call must have been arranged, because on January 17 Garret writes to Perrin again, saying that he has consulted the relevant department after their recent telephone conversation, and he reinforces the opinion that Fuchs is a reliable character. “It is considered that there would be no objection to this man remaining in the U.S.A. as he has never been very active politically, and recent reports endorse the good opinion you have of his behaviour in this country”, he writes, but adds, ominously, “It would not appear to be desirable to mention his proclivities to the authorities in the U.S.A., and we do not think it at all likely that he will attempt to make political contacts in that country while he is there.” Garrett had been updated by an enigmatic note from a colleague in D2, who has obtained a full picture of Fuchs’s communist activity from Serpell, F2a (although someone has inscribed ‘B1a’ above it). The note adds that “Clarke’s opinion [Clarke being the established officer handling the CPGB in F2a: Serpell has presumably recently been transferred from B1a] is that he is rather safer in America than in this country, and for that reason he is in favour of his remaining in America where he is away from his English friends. Clarke’s opinion also was that it would not be so easy for Fuchs to make contact with communists in America, and that in any case he would probably be more roughly handled were he found out.” Whether ‘safety’ in these circumstances refers to Fuchs’s individual ability to be kept free from harm, or whether it describes the degree by which the authorities might be protected from Fuchs’s possible treacherousness, is left for the reader to decide.

The whole charivari appears to be a ridiculous mess, with senior MI5 officers staying out of the business (having presumably been squared by Perrin), and the junior officers floundering around in the dark – a perennial phenomenon in the execution of MI5’s charter. There was no serious attempt – let alone an opportunity – for F2a and F2b and D to voice their concerns about Fuchs’s proposed mission until after he had left. And thus Hollis must be judged to have been part of that conspiracy to pretend that sending Fuchs to the USA was not a risk, and to have gone along with the insistent demands of Perrin and his department. Yet Pincher’s account is erroneous. He gets the date of departure wrong, and inserts Hollis (alone) as the dominant figure in the imbroglio, ascribing all manner of statements to him that were in fact made by other officers, as can be verified by the wording that Pincher uses, and the evidence of the files. Unless the files were subsequently weeded (Pincher’s book appeared in 2012, Rossiter’s in 2014) there is no archival record that indicates Hollis’s direct involvement. That does not mean that MI5 was not involved in some very weird backroom business, but it does negate Pincher’s highly distorted account of Hollis’s dominant role in the catastrophe.

And that effectively brings Pincher’s coverage of Hollis during the war to a close, as the next event he covers is Gouzenko’s defection in September 1945.

What the Histories Say

While Pincher’s accounts of Hollis’s activity are obviously a distortion of the truth, we should expect any ‘official’ or ‘authorized’ history of his department to be markedly better, and that independent historians would offer a cooler, unbiased assessment of his career.

Christopher Andrew’s Defend the Realm

[Andrew’s history is a problematic compilation. He provides many insights, but his sources usually cannot be verified. His coverage of Hollis is very spotty, although he does provide a different strategic perspective on the Fuchs business of 1943 through his description of concurrent moves at Cabinet level to restrict communists from undertaking sensitive work.]

In his authorized history of MI5, Christopher Andrew is very restrained about Hollis’s career. He records that Hollis was recruited by Kell in June 1938, but, extraordinarily, Hollis’s first appearance in the history is not until 1943, when he is already ‘F2, in charge of monitoring Communism and other left-wing subversion’. Andrew does throw in a retrospective comment that Hollis had regarded the main SIS Communist expert, Valentine Vivian, with veneration, but says nothing about his studentship in Communist affairs under Archer (whose name changed from Sissmore to Archer when she married Group-Captain John Archer, of D Division, the day before war broke out). He briefly covers the reorganization instituted by the selected new leader, David Petrie, who had been approached in November 1940 to take over MI5. Petrie, after performing a study of MI5 and gaining a commitment from Swinton and Churchill that he would be able to run his own ship, decided to create new Divisions, breaking up the overloaded B Division (responsible for counter-espionage) into a new B Division concentrating purely on anti-Nazi counter-intelligence, E Division charged with alien control under Ted Turner, and F Division with a mission of counter-subversion, under Jack Curry. As I have shown, this is an oversimplification of what changes occurred.

Andrew does appear confused about timing: he states that, after the eyes of the Security Service were opened by Krivitsky (in February 1940), it was handicapped in investigating Soviet espionage by lack of resources. “B Division (counter-espionage) was wholly occupied with enemy (chiefly German) spies. Wartime Soviet counter-espionage, which was considered a much lower priority, was initially [sic] relegated to a single officer (F2c) in F Division (counter-subversion).” This is erroneous and misleading: F Division was not created until August 1941 – after Barbarossa. This assessment completely misrepresents a critical year of negligence. There were no potential ‘enemy’ spies apart from Germans until June 1940, when Italy declared war on Britain: Andrew has his categories wrong, and he is careless with dates and responsibilities.

The most thoroughly covered aspect of Hollis’s tenure is the Springhall case in 1943, and the subsequent discussions about open communists working for sensitive government departments. Andrew records how, after Springhall’s sentencing, Hollis and Felix Cowgill (the head of Section V in MI6) interrogated the MI6 secretary Ray Milne, who admitted that she had passed information to an ally (the Soviet Union), and was dismissed but never prosecuted. For some reason, Andrew thereafter emphasizes the role of David Clarke (F2a) rather than Hollis himself. As the file KV 4/251 shows, on October 21, 1943, Clarke submitted a long report that showed how dozens of communists were then working in government institutions, and that many of them had access to information of the highest secrecy. He provided numbers, but did not list names. Hollis passed this report on to Duff Cooper, a rather ineffectual protégé of Churchill, who was Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and head of the Security Executive at the time. Cooper soon responded (on October 27) that he had drafted a memorandum for the Prime Minister, at the same time asking for a list of those implicated. Hollis obliged the next day. Churchill indicated that he agreed with the recommendations in the memorandum, and the overall approval was minuted on December 13 – with Churchill’s famous decision to have vetting performed by a special panel under the Chairman of the Security Executive.

Hollis had, however, been active in the meantime. On November 4, he noted a discussion with Cooper, who had in turn spoken to the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison. Hollis looked to the Cabinet for guidance on how to execute any restrictive policies, as he had noticed that high-level officials, while agreeing with such a policy in principle, had problems executing it when it affected their departments. On November 9, Morrison made a strong case to the Prime Minister about removing communists from sensitive work, although he offered an exception for a man ‘whose specialist abilities are so valuable that it is better to take any risk in continuing his employment than to lose his assistance on the specialist job in which he is engaged.’ On November 10, Hollis reported that he had spoken to the Home Secretary, Sir Alexander Maxwell, who informed him that Morrison had expressed concern about MI5’s excluding anybody with left-wing views. Hollis had said that such the number of cases demanding transfer of the employee would be small, and that MI5 ‘would be very conscious of the desirability of being prudent.’ A few days later, on November 16, Director-General Petrie showed his approval of the moves, encouraged Hollis to address such cases himself but to be sure to gain approval from either Petrie or his deputy (Harker).

Of course, in the middle of this exchange, Fuchs had set sail for the USA. It is as if Perrin had got wind of the planned restrictions, maybe gained approval at a high level, and surreptitiously arranged for Fuchs to join the party of scientists. How much did Hollis know of the energetic attempts in his group to restrain Fuchs at this time? It is not clear. It seems more likely that he was in on the secret, maybe alongside Petrie, and that Fuchs had been acknowledged as one of those with ‘specialist abilities’ who could not be surrendered. It would appear that, far from insisting on indulgence towards communists like Fuchs, Hollis was trying to promote the integrity of F2 while acknowledging the political realities of his position. And Churchill’s desire for any future vetting procedure to be taken out of the hands of MI5, as well as to keep the whole process as secret as possible, reflects his need to control the whole process himself, as well as not make any overt gesture that might upset Stalin – a special sensitivity of his at the time.

Andrew elides all the subtleties of these dynamics – as well as the fact that Fuchs’s departure came in the midst of the negotiations. And he quickly runs through the events of 1944 which followed the mini-crisis. KV 2/451 shows that Hollis was involved in intricate negotiations with Edward Bridges (the Cabinet Secretary), Alexander Maxwell, and others throughout 1944 and early 1945, but the attention on possible ne’er-do-wells in sensitive positions was always focused on Communist Party members, and thus bypassed the less hidden but more dangerous threat from penetration agents. Andrew’s final flourish, as far as wartime is concerned, is to trumpet Hollis’s valiant attempts to bolster the efforts countering Soviet espionage. In a telling (but unverifiable) observation, he writes: “The leadership of the Security Service was also well aware that it was failing to keep track of Soviet espionage. With at least partial justice, it blamed its failure on the severe restrictions placed by the Foreign Office on investigation of the Soviet embassy and Trade Delegation, and therefore of the intelligence residences for which they provided cover.” (pp 279-289) He cites a March 1943 entry from Liddell’s diary where Liddell and Hollis discussed the risk, as well as the exposure of doing nothing, although exactly what ‘action’ MI5 might have undertaken, apart from surveilling arrivals and departures at the Embassy more closely, is not clear.

Hollis is described as ‘the senior MI5 officer most alert to the continued threat from Soviet espionage’. Hollis regarded Valentine Vivian in MI6 as the most expert in the field, but he disliked his successor, Felix Cowgill, and was also dismissive of MI6’s overall efforts to investigate international communism. In another unsourced reference, from a memorandum to Petrie in April 1942, Hollis claimed that his group had ‘started, rather belatedly, to follow the activities of the Comintern wherever it appears’ (a project no doubt spearheaded by Milicent Bagot), admitting that F Division was stepping beyond its charter. Petrie encouraged him, but, apart from a voiced suspicion about Blunt, Hollis directed his section’s energies more against members of the CPGB, who, he misguidedly judged, would be the most obvious candidates for espionage. Yet there is no doubt that Hollis was not acting alone, or that he enjoyed the close attention of the director-general. Chapman Pincher chose to ignore these passages from Andrew.

John Curry’s ‘Official History’ of the Security Service

Curry’s history, which was written in 1946, and published in 1999, is in some places much more explicit than Andrew’s work. Curry was a complex character: he comes over as insecure and a bit neurotic from his exchanges with Liddell, always wondering where his career was going, and articulating disappointment that his contributions were not being properly recognized. He was probably not a very good leader, but he was a dedicated officer, and attentive to detail. Thus his history – which, as far as WWII was concerned, was much reliant on the assessments made by Division heads of their groups’ performance, but also contained much of his personal interpretation – is an important contribution to MI5’s form and function, and contains much information (such as on organization) in which Andrew showed only superficial interest.

For instance, the history contains organizational charts after Petrie’s restructuring in August 1941, as well as for April 1943, when Hollis was well-established as the head of F Division, with assistant-director status, after Curry left for a new position in ‘Research’ in November 1941. Curry states that the instructions for re-organisation were issued on April 22, 1941, but were not brought into effect until August 1. He also declares (p 146) that Petrie’s plans were based on Swinton’s proposals, which Swinton, as head of the Security Executive, had not been able to force upon a reluctant MI5 in December 1940. Yet Curry is vague about exactly what Swinton proposed, since the only function allocated to F Division is identified as ‘dealing with the B.U.F.’ – surely an understatement. As far as the evolution of the new structure is concerned, the charts in Curry’s volume show that Dick White and Major Frost were Assistant Directors of B Division under Guy Liddell in August 1941: Hollis and Aikin Sneath worked under Curry, who had been appointed Deputy-Director in charge of F Division (’Subversive Activities’). F Division was split into four sections: F1, under Lt. Col. Alexander (who worked with a large degree of independence from Curry), responsible for security in the forces; F2, under Hollis, responsible for Communism and Left Wing movements, where Clarke was charged with watching the CPGB (F2a), and Pilkington Russian Intelligence (= Soviet espionage, F2c), by default Hollis being responsible for the vacant slot of watching the Comintern (F2b). Sneath was responsible for Right Wing and Nationalist movements (F3), while Fulford in F4 watched pacifist groups. F3 was the reincarnation of B7 from the previous organization. Curry writes that, after April 1941, there was confusion as to whether MI5 or MI6 was responsible for maintaining adequate records about the Comintern, and that the expert knowledge of Miss Bagot in F2b was the only palliative to the situation.

Curry’s coverage of F Division is a bit erratic, and his account of Hollis’s contribution especially so, as if he bore some resentment for his successor’s responsibilities and achievements. He dedicates a long section on F3 (Fascist, Right-Wing, Pacifist and Nationalist Movements: pro-German and defeatists) in the main body of his tome, since its work was most relevant to the direct war effort. Yet Hollis is not mentioned once in the dense five pages (pp 308-312), and much is written in an irritatingly passive voice (‘it was felt . . .’). Thus the rest of F Division’s work is relegated to Volume 3, in what is called Chapter V, Part 2: ‘Communism and the U.S.S.R 1941-1945’. Here he introduces the challenges facing F Division in its attempts to defend against the unchanged long-term threats of the Soviet Union while dealing with a Whitehall that (after Barbarossa) regarded it as an ally. He writes that ‘the work of F.2.c has been discussed in detail under “Soviet Espionage”’, but that section does not appear until later.

Thereafter, Curry seems keen to present himself as the expert on Soviet counter-espionage. He provides a fascinating list of known ‘leakages” (without sources, of course), and a decent overview of the post-Springhall turmoil (without mentioning the Fuchs imbroglio). His main trumpeting of Hollis’s achievements occurs when he describes the creation of Section IX in MI6 (see above), but his discourse thereafter is more about MI6 than MI5. He returns to the theme of espionage in returning to Krivitsky, Glading and Springhall, and then describes the constraints placed upon MI5 by the Foreign Office’s prohibition of any attempts ‘to penetrate Russian official or Trade Delegation circles in this country’. He notes that the large Russian [sic] diplomatic establishment in London – over ninety individuals at the end of the war – were allowed to visit every sort of establishment and factory in the country, and had been detected attempting to see much more than that to which they were entitled. Hollis’s job in attempting to harness such activity had indeed been impossible.

F Division Reports (KV 4/54-58)

One gets more of the nitty-gritty, but not so much high strategic insights, from the reports that Hollis submitted to Curry. Hollis’s overview (KV 4/54) has been liberally marked, as if by sixth-form teacher, with question-marks, the occasional ‘No!’, and several ‘Xes’, which presumably mean approval. The assessor is presumably Curry, but a ‘corrected’ version has not been filed. After defining ‘subversion’, Hollis appears to credit himself with the claim that, in the face of the fact that the Communists and Fascists behave so differently, ‘the Head of the subversive division [sic] can give a certain political unity to policy’. What exactly Hollis meant by that, since the Division’s policy against communists had turned out to be largely ineffectual, is not evident, but Curry has indicated his endorsement of this rather woolly claim.

Hollis’s report is a muddle, and is not delivered elegantly. His introduces the incorporation of F Division with the following statement: “At the outbreak of the war the staff of the four sections was seven: B.1. two, B.4.a two, B.4.b two, B.7 one. Of this total two were women. These sections, reconstituted into F. Division, reached high water numerically in 1943, when the staff reached twenty-nine.” That assertion strongly indicates that the four sections were brought over lock, stock and barrel into F Division. Yet MI5’s organization in 1938 shows that Soviet counter-espionage, oddly designated as ‘Civil Security – home & foreign’, B4a and B4b respectively, came under Sissmore and White, with Mr Younger supporting Sissmore. Hollis became the sole B4a officer, of course, during the curious events of September 1939, but Younger does not appear in F Division in the July 1941 chart. Hollis goes on to explain that, in autumn 1940, a new section, B4c, had been formed ‘to deal specifically with Soviet espionage in this country’, and that it was placed alongside B4a and B4b ‘under a single head’. He does not name that head, but the impression given is that it was not Hollis. That B4c unit presumably became F2c, described by Curry as a one-man band under Pilkington, but presented as ‘Russian Intelligence’.

Yet B4b already existed, set up to investigate Soviet espionage in the UK, and Bagot was described as being its head in December 1939. Perhaps B4c represented the assimilation of Jane Archer’s B14. Since White had been in charge of B4b since 1937, was he perhaps the ‘single head’ to whom Hollis anonymously refers? White is listed simply as ‘B2’ in the December 1939 charts, but he was probably placed temporarily in charge of B4 before the Petrie restructuring took place (the autumn 1940 changes that Hollis described briefly). John Curry can be frustratingly vague over dates and structure in his history, but he does offer the insight in his paragraph concerning that year of 1940 (p 161) that ‘Mr. White was supervising the work connected with the Communist Party and the Comintern and the arrangements for liquidating the Nazi Party . . .’ I thus conclude that White was indeed the ‘single head’ whom Hollis reluctantly had to acknowledge without identification.

In any event, the records [see Curry, above] indicate that Dick White, when he took over control of B1 in June 1941, retained, as ‘officer in charge’ a B4 section headed by Whyte (who had previously been B2b, responsible for ‘Counter-espionage Germany’) that covered any traces of espionage, whether ‘enemy’ or not, by UK citizens. That unit may have included other names (such as Boddington and Badham) that appear on the earlier chart, but have not found their way into F Division. A perennial challenge for the chronicler of MI5’s activities is trying to determine what happened to officers who disappear from the radar screen – and sometime return to it. Such a task requires meticulous recording of appearances scattered around files, something that I have not undertaken with any thoroughness, but which is a project that I would cheerfully delegate to my research assistants – if I had any.

Hollis describes how F4 was created in July 1941 (presumably prompted by Swinton-Petrie concerns) to investigate ‘new politico-social or revolutionary movements’, but was dismantled in April 1942 when no signs of such could be found – incidentally when Hollis was at a convalescent home with tuberculosis. The work was absorbed into F3 and F4, and Fulford with it, no doubt. A similar fate awaited F1, commissioned to study the internal security of the Armed Forces, but eventually absorbed into F2a and F3. Hollis provides no date: the section is still present on Curry’s organization chart for July 1943. He then jumps to 1944, when the question of ‘renegades’ (which meant persons who may have helped the enemy, excluding spies) was magnified. That required a new section under the name of F1 to be created on September 30, 1944 – presumably a decision of Hollis’s, although it would have required board-level approval.

There follows a rather cryptic paragraph, where the considerable help provided to the Division overall by ‘new sources’, presumably spies within the CPGB HQ at King Street, is outlined, with redactions. Hollis then closes with summary histories of the different sections. He introduces them by stating that the functions of F Division are ‘only in small part preventive or punitive, since its role is to provide information to various government departments, and to act as adviser to them on subversive activities’. That might be deemed to be too passive by some critics (certainly Chapman Pincher), and Hollis should perhaps have taken on a more energetic part in selling his ideas. We must, however, bear in mind that he was in constant communication with the director-general, who was very sensitive to the political situation, and who would surely have prodded Hollis to do more if he judged a more aggressive approach were merited.

Perhaps the most fascinating account is that of F2b, where the author laments the fact that the section had to shoulder the burden of compensating for the incompetence of MI6’s Section V in handling the threat of Communism, and describes how MI5’s superior Registry personnel even helped its rival service to ‘get in touch with their own records’. Hollis states that the only success that F2c had during the war was that of Green – another surprisingly thin and inadequate account. Oddly, Hollis says nothing about the radio interception issue of which Curry so proudly boasted. Whether that was out of modesty, or whether Curry simply got the whole matter wrong, remains another enigma of F Division’s history.

Nigel West ‘s ‘MI5’

Nigel West’s ‘MI5’ offers a strange account, although it does add some names to the pot. His organization charts refer to ‘wartime organisation’, which is a very fluid concept. Thus Alexander, Boddington, Watson and Curry are shown working under ‘Military Subversion’ in an unreconstituted B Division, whereas ‘Soviet Affairs’ contains Saunders, Bagot, Sissmore and McCulloch. An accompanying chart for F Division indicates it was under Ede, as Director of Overseas Control, with a loosely attached group named ‘Political Parties’ containing Hollis, Kemball Johnston and Fulford under ‘Communists’, and Mitchell under ‘Fascists’. It is a mess. West does not cover the re-organization, and refers to Mitchell as joining F Division’s [sic] anti-Fascist section in 1939. In his narrative, West indicates that, when Frost was inserted into B Division in June 1940, Hollis had recently succeeded Colonel Alexander on the latter’s retirement. But Alexander is presumably the same individual whom Curry shows to be leading F1 in July 1941, still active and unretired. Moreover, West asserts that Hollis was promoted to Assistant Director rank in 1940, after two years in F Division [!], ‘and was also appointed to serve on one of Lord Swinton’s sub-committees, the Committee on Communist Activities, a Whitehall interdepartmental group formed to monitor CPGB sympathizers and the growing diplomatic presence in London.’ (What this committee achieved seems to have been lost.) West thus lazily backdates the functions of F Division in counter-subversion to 1938, the year Hollis was hired.

Other Sources

Hollis turns up in several other books. W. J. West’s The Truth About Hollis (1989) (re-printed in the USA as Spymaster: The Betrayal of MI5) contains much useful information about Hollis’s early life, but it is a rambling work, expressing Pincheresque tendencies, that sheds little detailed light on Hollis’s activities during World War II, and it indulges in a lot of speculation. West does provide some useful insights into Hollis’s relationship with Claud Cockburn, especially during the process to ban the Daily Worker in 1941. West had access to the file on the banning of the Daily Worker (HO 154/25140), but the PF on Cockburn (KV 2/1546-1555) was not released until 2004, five years after West died. West did manage, however, to extract from the National Archives in Washington a document provided by the Security Executive to the FBI which summarized Hollis’s admittedly favourable opinion of Cockburn. (I pick up below the threads of Pincher’s and West’s accusations against Hollis.) West also stresses that Hollis was solely responsible for the oversights concerning Klaus Fuchs. The recurrent problem of such analyses that suggest that Hollis was a dangerous lone wolf undermining the nation’s security is that they credit him with a large amount of inexplicable influence over his senior officers.

In his Secrets of the Service (1987), Anthony Glees offered a spirited defence of Hollis against the allegations made by Chapman Pincher. Glees presented some searching and highly logical, analysis, but his book is marred by a) his taking Pincher’s accusations too seriously; b) his being too easily impressed by Foreign Office mandarins (in particular Patrick Reilly); and c) his lack of access to archival material. In addition, the introduction of possibly useful material is flawed by its anonymity. For example, on page 326, Glees refers to a document titled ‘List of Foreign Communists considered dangerous by MI5’, reportedly passed by ‘Hollis’s section’ (B4?) to the US Embassy on December 26, 1940. This is a document that Pincher had ‘come across’ (‘how?’, one might ask), and which he had generously passed on to Glees. Yet the document is neither identified, nor described fully, nor re-presented (photographed). Moreover, Glees then goes on to write about ‘the MI5 reports that I have seen’, without explaining how he gained access to them, or who wrote them, when. This is not good historiography, and Glees’s claims cannot be followed up for verification.

Mike Rossiter’s profile of Klaus Fuchs, The Spy Who Changed the World, is intelligently written, but does not mention Hollis until the events of 1949, when Fuchs returned to Britain. Trinity, the compendious biography of Fuchs by Frank Close, is generally excellent, offering meticulous inspection of the archives. Close covers the oversights concerning Rudolf Peierls’s approaches to have Fuchs join him in Birmingham in July of 1941 (see below), which triggered exchanges between C. C. H. Moriarty, the Chief Constable of Birmingham, and Milicent Bagot of F2B. What is extraordinary is that Bagot signs the letters under David Petrie’s name, as if they were working in close co-operation. Close rightly observes that Hollis did not appear to be involved in these discussions. But the author mistakenly presents Hollis as being head of F Division at that time, when he did not replace Curry until November 1941. Hollis’s role as head of F2 should have required him to be closely attentive to the Fuchs case, but Petrie appears to exclude him. Thus a remarkable phenomenon is overlooked: both Hollis and Curry were for some reason kept out of the loop over Fuchs’s recruitment, while Petrie’s involvement can hardly bolster a case that claims that Hollis behaved wantonly, as opposed to carelessly, over allowing Fuchs into a sensitive project. While sometimes challenging Pincher on his more questionable claims, Close is also a bit too willing to use him as one of his primary sources.

A Matter of Intelligence, the 2014 work by Charmian Brinson and Richard Dove, subtitled MI5 and the Surveillance of Anti-Nazi Refugees 1933-50, is an uneven work. The authors are a bit too keen to tilt the balance in favour of Pincher’s claims about Hollis. Their book contains much valid scholarship, as well as some sloppy attribution. For example, on page 199 they claim that, on June 2, 1942, Hollis, writing as C2B, after making ‘only desultory checks’ on Fuchs’s application for naturalization, approved the process, citing KV 2/1245. They quote the report from him that stated that MI5 had no objection The trouble is that the request for information truly did originate from C2b (Mrs Wyllie) on May 28, C Division being responsible for Examination of Credentials. The note was addressed to F2b, in the person of D. Griffth. Griffith replied on May 30 that MI5 had no objection, allowing Wyllie to contact the Home Office, as she did, on June 2, confirming the judgment. Hollis does not appear anywhere in this exchange: he was in fact absent in the sanatorium at the time. Thus another myth entered the books. In addition, Brinson and Dove also misrepresent the attitude that Hollis took to the suspected espionage of Engelbert Broda in May 1943, when he expressed his opposition to applying surveillance on him (see KV 2/2350). They do not faithfully reflect Hollis’s complete statement, which I explore below. They intriguingly assert (without giving evidence) that Hollis was known as ‘the master of inaction’ within MI5.

The substantial volume produced by K. D. Ewing, Joan Mahoney, and Andrew Moretta, titled MI5, the Cold War, and the Rule of Law (2020) contains a few pages on the post-Springhall clamp-down on Communists in government, using KV 4/251. They do, however, miss the main point, echoing the untruth that the CPGB encouraged espionage, and even annotating the absurd tale that Springhall had been named (by Andrew Boyle) as ‘running the Cambridge Five’. (I cover those episodes below.) Finally, Ian Maclaine’s Ministry of Morale (1979) cites a memorandum written by Hollis to the Foreign Office in October 1940, which gives a ringing endorsement of Hollis’s insights as he took over Archer’s role. It is worth quoting: “MI5 voiced astonishment at the Ministry’s failure to appreciate the link between the British communists, the Soviet Union and the Comintern, an attitude largely irrelevant to the matter at hand but one shared by Lord Swinton’s Committee on Communist Activities, an interdepartmental body which monitored the doings of British communists.” (INF 1/910). [This was a new one on me: file CAB 123/55 at TNA indeed covers this Committee’s activities, and I have added it to the list to be photographed.]

Guy Liddell’s Diaries

[Liddell’s Diaries, if interpreted with caution, can provide some valuable insights into the dynamics of MI5’s operations. Yet we must bear in mind that they are episodic, not comprehensive, and thus not necessarily representative, and may even show biases. Hollis assuredly had significant conversations with other MI5 officers (particularly White and Petrie) that were never recorded for posterity.]

Guy Liddell maintains a running commentary on his interactions with Hollis through the war years. Immediately war broke out, with the Soviet Union a party to the Non-Aggression Pact with Nazi Germany, Guy Liddell brought Hollis in to try to resolve how MI5 should treat the Communist Party. In this respect, it may be with deliberation that Liddell apparently bypassed Jane Sissmore, since he chose the day of Sissmore’s marriage to Joe Archer (September 2, 1939) to have this first recorded conversation. Here Liddell cites Hollis as saying ‘that the Communist Party shows strong signs of supporting the war on grounds of Germany’s aggressive action to deprive the Poles of their independence’ (a line shortly to be undone by Moscow’s rebuke of the CPGB), but, oddly, Hollis is also brought into consultations on British Fascists (September 25). On December 11, Liddell reports that Hollis’s notes on Willie Gallacher and Captain Archibald Ramsay (the fascist sympathizer) have been shown to the Prime Minister.

Moreover, on February 13, 1940 (just before Krivitsky returned to Canada), Liddell records that he ‘had a talk with Roger Hollis about the Communists in the event of a war with Russia’, suggesting that Hollis already had an authority beyond what the managerial structure would indicate, and that he was not solely involved with communist subversion. Jane Archer was no doubt completely occupied with Krivitsky at this time, and preparing her report, but it is clear that she has nothing now to do with possible suppression of the British press. Liddell has further discussions with Hollis on how the CPGB and Communist shop stewards should be dealt with should war with the Soviet Union break out. By March 18, Liddell is able to report that ‘Roger’s plan for dealing with the Communist Party here is now complete and is being sent to the Home Office’, a plan that includes arrangements for internment. It is Roger’s plan, not Jane’s.

It is now that the pair go to talk to the mysterious G. H. Leggett (see https://coldspur.com/astbury-simon-long-and-blunt/), Hollis’s actual status and office in MI5, and his professional relationship with Archer in MI5, remaining undisclosed. They seek Leggett’s advice on ‘what to do about Communists?’. Yet Liddell had gone to see Leggett, without Hollis in attendance, on January 4, when he reported that Leggett thought that the Daily Worker was making a fool of itself over the Finland business [the Soviet Union’s attack on the nation], and that Labour leaders were revelling in its clumsiness. Thus Leggett believed there was no point in trying to suppress the newspaper now, although he thought it should not be exported. Did Liddell use this occasion to feed Hollis with guidance on what would be a sensible strategy? It is all very strange. On February 20, Hollis had gone to see Leggett, alone, and Leggett strongly suggested that interning CP leaders would receive strong support in Trade Union circles. Liddell (to whom Hollis must have reported this conversation) reflects that he is not so sure, and shows himself to be a ditherer, and not a good delegator.

Soon afterwards, Hollis is indisputably collaborating with Dick White, as in early April they jointly present a memo that outlines the threat for espionage and sabotage represented by communists. The advice is firmly in favour of internment, and restrictions of movements. By June, however, Hollis visits Leggett again, who does not want to use 18b (Defence Regulation B, allowing internment without trial) against communists, unless there were exceptional circumstances. This advice would suggest that Leggett was at this time part of the Legal team in MI5. The service had enough on its plate at this stage of the war, since, with Churchill’s arrival as Prime Minister, the pressure for interning more right-wingers – as well as any refugees from Germany – intensified. From an intelligence standpoint, however, the moves would suggest that MI5 was taking the Nazi-Soviet Pact seriously, and did not yet regard it as merely a tactical convenience.

In echo of this assessment, a significant entry for August 26, 1940, contains the startling conclusion by Hollis that Moscow is intent on fomenting conflict, revealing its message that ‘no steps should be taken to oppose a German landing in this country since a short period under a Nazi regime would be the quickest way of bringing about a Communist revolution’. Hollis had studied CPGB documents that had been in the possession of one Eric Godfrey (a mysterious figure who was something of an irritant within the CPGB: how MI5 gained access to such papers is not explained). While he seems to have taken on a responsibility that should properly have been handled by the Joint Intelligence Committee, a crisper reminder of the danger from Moscow could not be asked for. In fact, Hollis’s concerns did reach higher echelons, since he and Liddell met with the Vice-Chief of the Imperial General Staff on October 5 to discuss Communism and troop morale.

The record on Hollis for 1941 is sparse, although tensions can be seen by early April, with the new Director-General, Petrie, devising plans that would effectively relegate John Curry (who had become Liddell’s deputy in September 1940), and Hollis, in favour of Theo Turner, who would command an overriding ‘Aliens block’. After Curry, Hollis and Liddell conferred with Menzies and David Footman about setting up a cross-service group to handle ‘contemporary social movements’, that initiative was quashed by Petrie’s re-organization of April 22, when the new F Division was set up under Curry, relieving B Division of subversives and aliens control. Curry, with his keen insights into the Comintern’s machinations, felt he was being sidetracked. Liddell wrote how depressed Curry was at his loss of status, and in early October, he was moved into a staff position under Petrie. (Curry elsewhere stated that he could never work under Dick White.) Thus the position of head of F Division, with the title ‘Assistant Director’, fell into Hollis’s lap.