[I had been intending to study closely Goronwy Rees’s files at Kew ever since they were released in October 2022. My correspondent Edward M. prompted me to bring forward my analysis when he recently drew my attention to MI5’s tentative idea about offering immunity to Anthony Blunt soon after the abscondment of Burgess and Maclean. I thank him for his percipience. Here is my analysis. In short, Blunt should have been nailed in 1951 . . . Now read on.]

Contents:

Introduction

Players and Predicaments

The Sources

Phase 1: May 7 to May 25

Phase 2: May 25 to June 2

Phase 3: June 4 to June 12

Phase 4: June 13 to August 27

Conclusions

Envoi

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

When Donald Maclean disappeared in May 1951, while it was a setback and an embarrassment to MI5, the Service could hardly have been shocked. After all, Maclean was shortly to be brought in for interrogation after a confident conclusion had been made, arising from the VENONA decryption project, that he was the spy HOMER who had passed on confidential material to the Soviets from Washington in 1944. The surveillance on him had been very obvious, but not comprehensive. On the other hand, his accompaniment by Guy Burgess by all accounts astonished and perturbed Guy Liddell and Dick White. Burgess was a troublesome character, but he was apparently not suspected of any treacherous activities. While he had had meetings with Maclean since his return to the UK in April, MI5 did not believe that the couple maintained a longstanding relationship. Yet Burgess had resided with Kim Philby, already under some suspicion, in Washington, and if a maverick like Burgess could have been a Soviet agent, what others might be lurking?

Moreover, the escape carried a strange twist. According to Burgess’s long-time friend, and former conspirator, Goronwy Rees, whose account of the events has been allowed to dominate the histories, MI6 and MI5 were alerted to Burgess’s disappearance – and maybe to the suspicion that he might have fled to the Soviet Union – the day before Maclean’s absence was officially noted by his employer, the Foreign Office, namely Monday May 28. (It may amuse some readers to learn that on Tuesday, May 29, J. D. Roberston of B Division applied for a Home Office Warrant to intercept Maclean’s mail. It was granted the same day.) The reason that Rees was ahead of the game was because Burgess had carried on a long and rambling telephone call with Margie, Rees’s wife, the morning of his escape, and her husband decided to inform MI6 and MI5 of his hunches when he returned home on Sunday, May 27, and learned about the conversation. Why would the academic draw unnecessary attention to his own dubious past, and his association with the traitors, at such a perilous time? And how could he have been so sure, after Burgess had been absent for just a couple of days, and before he knew that Maclean had also disappeared, that he had absconded to Moscow? This report explains the story that other accounts have overlooked. As with many of his cohorts and contemporaries, Rees left behind him a deceitful memoir, but his main adversaries in MI5 also showed a false trail.

Players and Predicaments

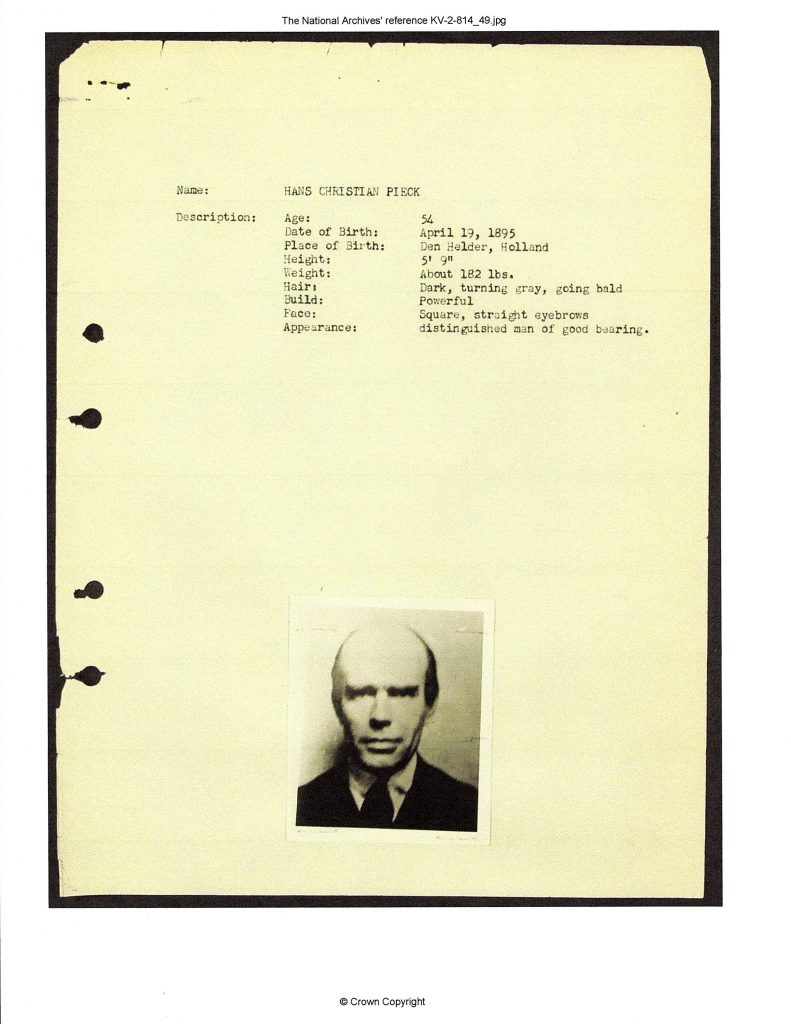

The action takes place between May 7 (a Monday), when Guy Burgess returns in disgrace from Washington, and August 31, when MI5 takes a closer look at Goronwy Rees’s collusion with Anthony Blunt. The key figures are Burgess, Blunt, Rees, David Footman (an MI6 officer), Guy Liddell (deputy director-general of MI5), and Dick White (head of B Division).

Burgess: Guy has been sent home in disgrace, and he is shortly facing dismissal from the Foreign Office. He thus needs to find a new job. With the net closing around Donald Maclean, he must quickly assess his own vulnerability, and ascertain from his fellow-spy Anthony Blunt what plans are in place to exfiltrate Maclean. He realizes that events in recent years, including his residing with the Philby household in Washington during his spell there, will provoke suspicions about his integrity. He must also check whether he can rely on his old friend and recruit Goronwy Rees, who had disastrously changed sides at the time of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, and whom he wanted killed at the time, not to denounce him. He has thus set up early assignments with Blunt (who, according to some reports, meets him at Southampton), and with Rees, at whose house in Sonning, Berkshire, he arrives later on the day he landed, May 7.

Blunt: Anthony Blunt, who left MI5 at the end of the war, has been kept informed of the progress on the HOMER case by his handler Yuri Modin, fed via Moscow Centre by the communications of Kim Philby, who, as MI6’s representative in Washington, has been privy to the investigation, and has passed on information to his handler. Contrary to many accounts, Moscow was thus not dependent on the arrival of Burgess to learn that Maclean indubitably fitted the profile of HOMER, identifiable by his trips to New York. Blunt is nervous: he had been recruited by Burgess in the 1930s, and he has a more obvious shadow hanging over him because he was known to have had communist sympathies in the past, and to have been caught passing on military information to the Soviets in 1944. That misdemeanor appears, however, to have been forgiven as a case of exuberant solidarity with the wartime ally, and he remains good friends with Liddell and White. Yet the possibility of a chain of disclosures, what with Philby coming under deep suspicion in the preceding years, and Burgess’s closeness to him in Washington, seriously unnerves him.

Rees: Goronwy Rees has three dark clouds hanging over him: i) in the late 1930s, he had agreed to supply Burgess with information (to the extent that he was given a cryptonym by the NKVD), although he knew that his friend was working for the Comintern; ii) he knew that Blunt had fulfilled the same role, since Guy had told him so; and iii) he has never disclosed any of this information to MI5, out of loyalty to his friends. The longer that time passes, the more awkward it would be to explain away any of these embarrassments. Since the breach with Burgess in 1939, he had restored his friendship with him, and after the war seen him frequently, to the chagrin of his wife and relatives, but he is grateful that Burgess has recently been an ocean away. He assumes that Blunt made a similar breakaway in 1939, but he is not certain. A recent chance encounter, and a verbal assault by a drunken Maclean, accusing him of ‘ratting’, has caused him to think that Maclean may have been a Burgess recruit, as well. Thus, when Burgess writes to him from the U.S.A., requesting to visit, it fills him with some anxiety, even though he knows nothing about the revelations gained from the VENONA project. Rees had been working alongside David Footman in MI6 – though only part-time – at least until September 1949.

Footman: David Footman is a minor player, but as a friend of Burgess, Rees and Blunt, and as a vital conduit from MI6 to MI5, plays an important role in the scenario. When Burgess was working at the BBC in 1936, Footman had recruited him to report on communist activities in the universities. He is a novelist, and an intellectual historian of some stature in MI6, but also not utterly trusted because of his left-wing views. Indeed, items in Goronwy Rees’s file explicitly state that MI5 suspected that Footman had himself at some time been an agent of the Russian Intelligence Service. This testimony may have been supplied by Stuart Hampshire, whose identical claim can be seen in the Personal File of the Rothschilds.

Liddell: The deputy director-general of MI5 has had an uncomfortable time under Percy Sillitoe, a figure out of his depth and little respected by his subordinates. Liddell is not closely involved with the day-to-day counter-espionage projects, since the more politically astute Dick White has kept the HOMER investigation under his wing. As Blunt had been his personal assistant during WWII, Liddell retains a close admiration for him, and treats him as a consultant, meeting him frequently. One critical aspect of the case is that Liddell is away on leave in Wales from June 3 to June 12, a fact that is vital for verifying some of the claims made by Rees.

White: Dick White, the head of B Division, has steered the HOMER investigation, sometimes in ways that indicate that he would prefer the whole project be abandoned, yet he has been pushed to the climax by the growing evidence. He struggles in trying to control his sister intelligence organizations, GCHQ, which has exclusive control over some vital decrypts, MI6, which is overall protective of Philby, as well as the Foreign Office, which wants to prevaricate. He is, however, a more commanding figure than Sillitoe in the multiple meetings that take place. His main concern is that the FBI should not find out about the identity of HOMER before MI5 can inform them, and he is intent on controlling the damage when the news does come out. While he judges that Maclean is acting alone, he has for a few years held, alongside Liddell, strong suspicions about the possible treachery of Kim Philby, but he has been reluctant to speak out because of the entrenched support for him held by senior MI6 staff. He has, however, recently instructed his team to create a dossier on Philby for passing clandestinely on to the FBI, and this package contains suspicions about Burgess, partly owing to his close companionship with Philby in Washington. Yet White’s failure to act earlier means that he might later be held partially responsible for Philby’s disastrous posting to Washington.

(For further background reading, see https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-devilish-plot/ and https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-tangled-web/.)

The Sources

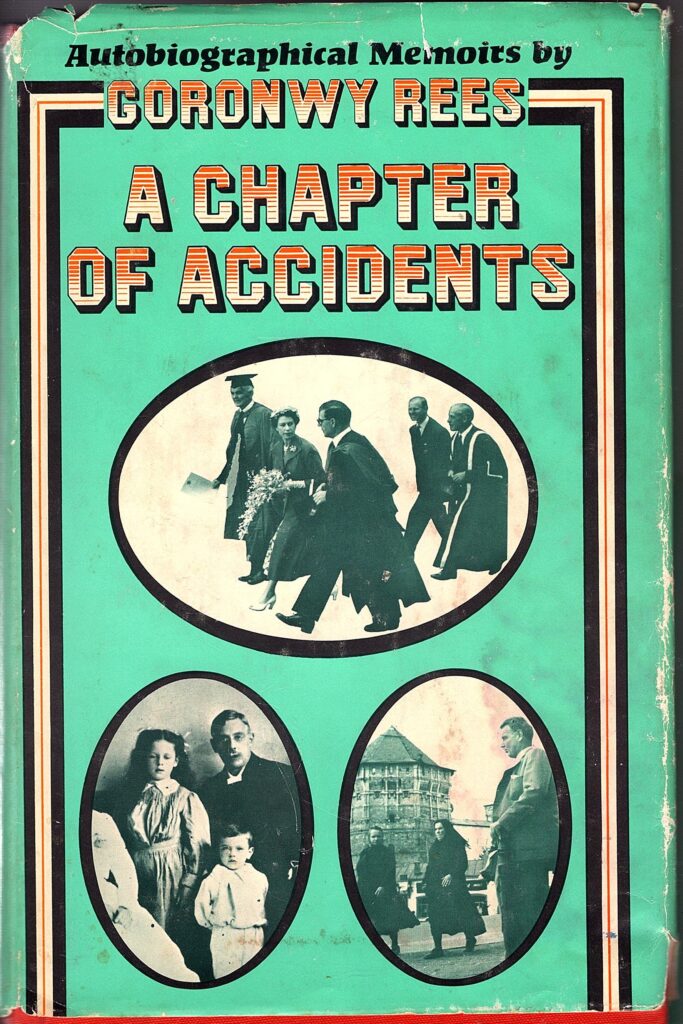

The primary sources are the memoirs (as personally written, or as described to biographers) of Goronwy Rees (A Chapter of Accidents, 1972), Dick White (The Perfect English Spy, 1995), and Yuri Modin (My Five Cambridge Friends, 1994). Rees’s contribution is extended by the reflections of his daughter, Jenny (Looking for Mr. Nobody, 1994 & 2000). Yet all these volumes must be treated with some caution, as each participant had reasons for disguising his exact role, and thus for omitting certain events, or for providing misleading information. A faulty memory (especially in the case of Rees, who drank more heavily than most of his colleagues and friends) may play a part.

Also important is Andrew Boyle’s Climate of Treason (1979), the revelations of which largely derived from what he was told by Rees. Conspiracy of Silence, by Barrie Penrose and Simon Freeman (1987), is a noble endeavour to unravel the complexities of the Blunt case, but relies too much on oral testimony, and the authors fail to resolve the multiple contradictions that their narrative throws up. John Costello’s Mask of Treachery (1988) offers a solid couple of chapters on the events: Costello brings some very useful analysis of the FBI files to the case, and is good on the American connection, but he is less insightful on the aspects of the case concerning Rees. Boyle and Tom Bower (who took over the biography of White after Boyle’s death) conducted multiple interviews with persons who knew, or who were associated with, Blunt, Maclean and Burgess in 1951: these individuals occasionally provided dates to encounters that can probably be regarded as reliable, but The Perfect English Spy is overall a very untrustworthy guide to the events of this period.

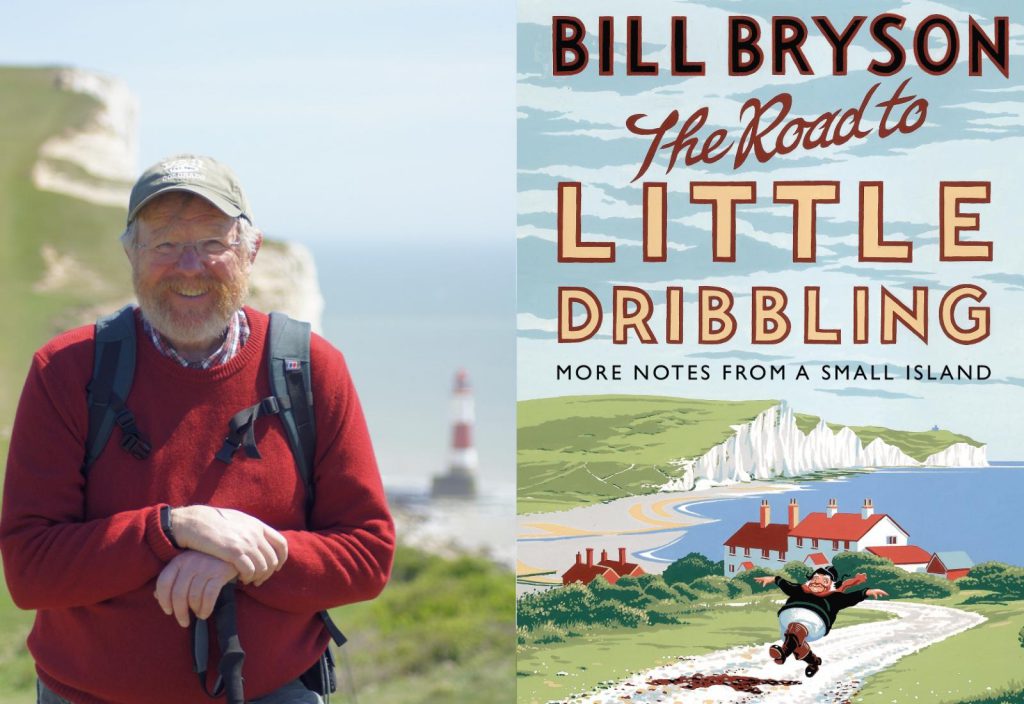

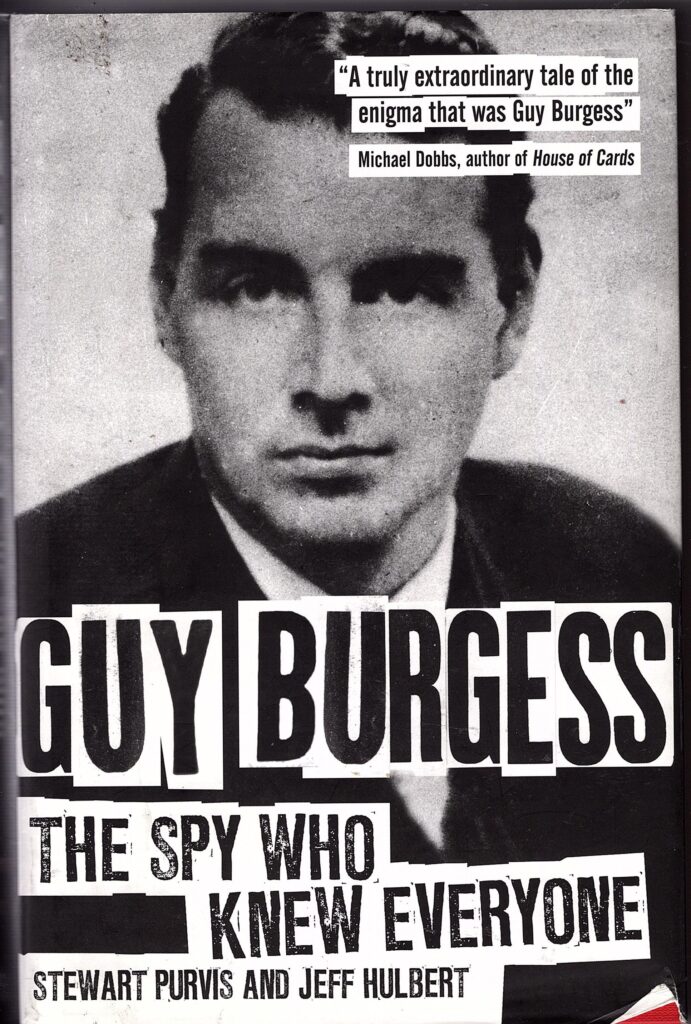

Two biographies of Burgess are useful. Andrew Lownie’s Stalin’s Englishman (2015) and, even more so, The Spy Who Knew Everyone (2016) by Stewart Purvis and Jeff Hulbert, bring some important background research to the table. For example, Purvis and Hulbert’s research into David Footman is particularly enlightening. Miranda Carter’s profile of Blunt, Anthony Blunt: His Lives (2002), is insightful, though now much out-of-date. The most significant source, however, is the set of files on Rees released to the National Archives in October 2022 (KV 2/4603-4608), which were obviously not available to Purvis and Hulbert when they wrote their book. KV 2/4603 is the most relevant to this inquiry, although some of the interrogations and interviews carried out in the 1950s and 1960s shed important light on the accuracy of statements made in 1951. (I hope at some stage to analyze in depth the five other files.) This resource is complemented by a rich timeline detailing the activities of Maclean and Burgess in the critical weeks of May 1951, which can be inspected at serial number 607P in KV 6/145, one of the files concerning the investigation of the ‘Leakage of Top Secret Foreign Office Telegrams in the U.S.A.’

A last, but problematic, resource is Nigel West’s Cold War Spymaster (2018), which contains a long (ninety-page) chapter on the Burgess-Maclean business, and how it contributed to Liddell’s decline. It offers a rich array of facts and background material, but it is densely packed with long extracts from Liddell’s Diaries, and from the archival material on MI5’s investigation, and is short on proper integrative analysis. Rather alarmingly, West cites as a source Goronwy Rees’s files (which he erroneously lists as KV 2/3102-4106), yet they were not released until October 2022, four years after his book appeared. Whether West was given privileged access to this material, or whether he was simply advised of its existence and future release, is never stated. In any case, he fails to exploit the files and the contradictions implicit in them, or to compare the ‘facts’ in them with other accounts, as I have set out to do.

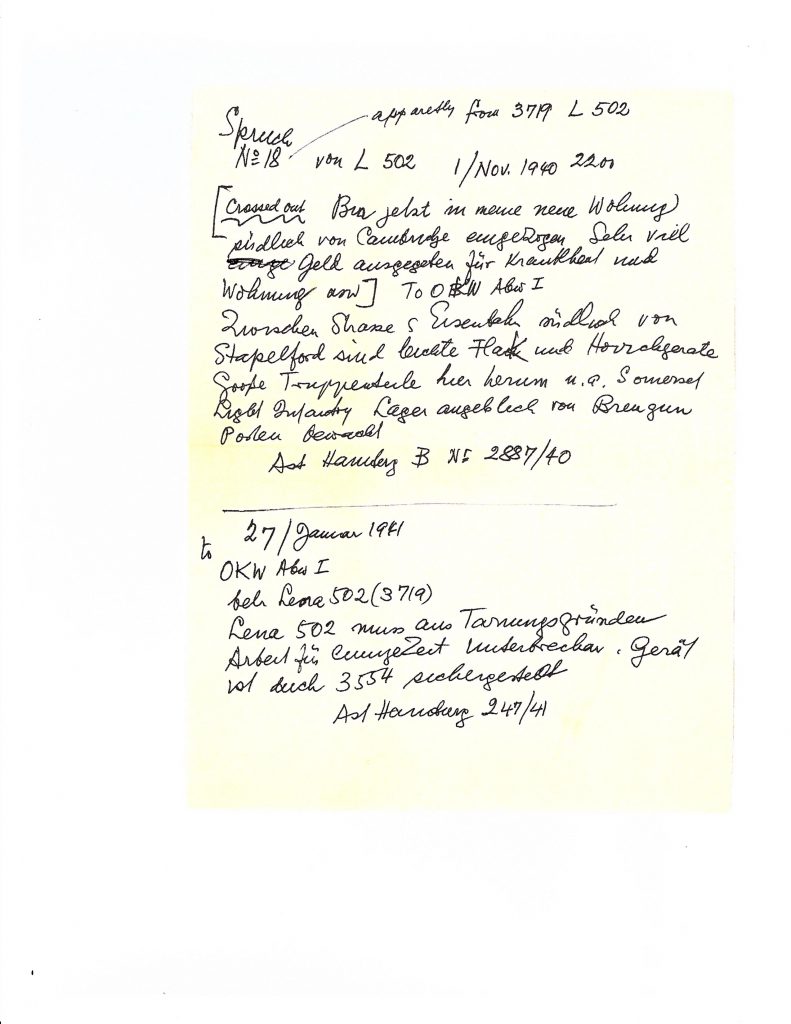

One of the most significant aspects of this timeline is the detail concerning Burgess. Whereas Maclean was under constant surveillance (and thus his encounters with Burgess reliably recorded), and Maclean told Burgess that he knew about it, Burgess was officially not under suspicion. Yet the chronology shows many of his May 1951 activities when he was not in Maclean’s company. Regrettably it rarely indicates the source of each datum: while some may have been compiled from interviews with his friends and associates after the disappearance of the duo, many would suggest that Burgess himself was under surveillance from the time he landed at Southampton docks. (And he admitted to Blunt that he believed he was, a claim that Blunt passed on to Robert Cecil.) For example, the first entry upon his arrival on the Queen Mary on May 7, 1951, states that he was met at Victoria Station by Blunt and Burgess’s boy-friend Hewit, and that he or Hewit then telephoned Rees. This is contrary to other accounts that assert that Blunt met Burgess in Southampton, including statements made by Peter Wright. It strongly suggests that he was immediately being closely surveilled, even to the extent of a phone warrant. If the story about the telephone call had come from Rees, he surely would have recalled who it was on the other end of the line? Moreover, Burgess’s visit to the Reeses the same day is attributed to ‘Rees’s signed statement’, suggesting that the other information was gathered by less conventional means.

The last vital source consists of the Diaries of Guy Liddell. Since they had immediacy, being written up almost exclusively every night, they are probably very accurate – although Liddell certainly dissimulated occasionally. Moreover, much critical information has been redacted. Yet the journals show unfailingly Liddell’s attitudes, especially towards Blunt and Burgess, and help pinpoint some critical meetings.

There are many accounts of this period in the literature, but I believe all are flawed by relying too much on the testimony of Rees, Philby, Blunt, Burgess (via Driberg), and Modin, all of whom probably distorted the facts deliberately. The stories told by Costello, and by Purvis and Hulbert, are probably the most comprehensive. Overall, so many contradictions are evident, such as in the multiple claims that were made as to whose idea it was that Maclean should escape to Moscow. In my analysis, I shall not attempt to reconcile all the conflicts, but instead concentrate on summarizing the evidence as it relates to Rees’s behaviour. I shall occasionally present parenthetical comments to identify some common traps into which writers have stepped.

Phase 1: May 7 to May 25

Burgess did not immediately seek out Maclean when he arrived in England: his first encounter was with Blunt, whom he had telephoned from the Queen Mary to request to be met at Victoria Station. He then went that afternoon to stay with the Reeses at Sonning. In his memoir, Goronwy described how he had received letters from Guy outlining his speeding incidents, and the fact that he was being sent home in disgrace. Burgess wrote that he would probably have to resign from the Foreign Office, and he added that he wanted to discuss a job opportunity with Goronwy. Strangely, Rees wrote that he arrived ‘after a night in London’, a timing that does not tally with the surveillance record. After some spirited debates, Guy explained that he had received an offer as diplomatic correspondent to a national newspaper (the Daily Telegraph). He was also on his best behaviour, to the degree that Rees invited him to stay the following weekend (presumably that of 18-21 June).

That did not turn out: Rees (who had been ill) called off the invitation by telephone. During that call, Burgess told him that he had since shared with Maclean a contentious memorandum he had shown Rees, which came as a surprise to Rees. He stated in his memoir that he never saw Burgess again, but in his interrogation by Peter Wright in March 1965, he told him that he did in fact meet Burgess again a few days later, and that it was then that Burgess told him about the exchange with Maclean over his memorandum. (Whether that was a lie, or a failure of memory, is not clear: the surveillance reports do not indicate a second meeting.) Rees wrote that he ‘later’ [unqualified] heard from friends that Burgess had relapsed into erratic patterns of behaviour again, drinking heavily and taking lots of medication of various kinds. Indeed, Burgess seemed intent on being visible in the company of his friends at regular drinking-haunts: he had lunch with David Footman at the Reform Club on May 8; he lunched with Cyril Connolly the next day, and with Footman again on May 11, and was noticed at the Reform Club the following day.

Yet, by then, moves to exfiltrate Maclean had quickly developed. (The Mitrokhin Archive, as cited by Christopher Andrew, indicates that it was at Philby’s insistence: I have not been able to inspect the original note.) According to Yuri Modin, his Soviet handler, Blunt had passed on to him news from Burgess, the day Burgess left Sonning, and Modin was perturbed enough to contact his superiors in Moscow. (Much has been made of the fact that Burgess’s role was to deliver news about Maclean from Washington, but that is clearly absurd given the time it took him to make his passage, as I have explained elsewhere.) On May 10, Modin met Burgess and Blunt, accompanied by the rezident Korovin. Moscow had approved a strategy for Maclean to escape, and Burgess was instructed to prepare Maclean for the process. If the two met soon after, surveillance failed to pick up the encounter, although a telephone watch recorded that they spoke on May 14. Yet two provocative events occurred on May 11: Burgess was noticed telephoning Rees – a conversation that Rees did not record in his memoir – and that was the same day that Burgess had lunched with Footman. Had he perhaps confided in his two friends what was actually going on?

It would not be surprising that Burgess was under surveillance. In the past few years he had drawn undue attention to his behaviour and affiliations. It went back to 1940, when he was shown to be in touch with the Comintern when he embarked on an eventually aborted mission to Moscow with Isaiah Berlin. MI5 had opened a file on him in 1942, although Liddell wrote in his Diary, on June 15, 1951, that the Foreign Office had first referred his name to MI5 only in January 1950. He had misbehaved in Gibraltar and Tangier in December 1949, and soon after he was detected leaking information to Frederick Kuh, an American journalist with dubious connections. His misdemeanours, including other drunken incidents were investigated, but he was merely ‘admonished’, not ‘reprimanded’. He was, however, considered a security risk because of his association with Moura Budberg and the Halperns. Yet, despite this track-record, in 1950 he was posted to the highly visible and important Embassy in Washington, as second secretary, where Kim Philby agreed to have him as a lodger, in the belief that he could ‘control’ him better that way. But Burgess misbehaved there, too, and the association just confirmed the suspicions.

On May 15 (Tuesday), Burgess went to see Maclean at the Foreign Office, and lunched with him at the RAC Club. According to Modin, Maclean was depressed when Burgess had to tell him of the escape-plan, Burgess giving Korovin a report after the meeting. Maclean was judged to be in such a frail state that Moscow decided that Burgess should accompany him for part of the way, and then return to Britain. But this plan was quickly rejected as impracticable, and Burgess was set up to disappear for good. The availability of the weekend ferry from Southampton to St. Malo was discovered (by Blunt? Burgess? Modin?), and a plan to exploit it on May 25, the weekend before Maclean was originally due to be brought in for questioning, was developed. Some accounts have claimed that the day of escape was accelerated because of the imminence of the interrogation, but that is not borne out by the evidence. In addition, the stories about Kim Philby’s assumed role as the ‘Third Man’, and his supposed ability to warn Burgess so late in the day by sending him a coded message, ignore the impossibilities of his passing information from Washington to London, and the fact that the logistics of the escape, involving reception parties and transport in Europe, would not have been able to be adjusted at such short notice.

What is certain is that the Foreign Secretary approved the interrogation on May 25, but the actual date had been postponed until at least June 18, to allow time for Maclean’s wife to have her child. During that last week before the abscondment, the investigating committee continued to dither, with Sillitoe expressing extreme caution lest the FBI not be suitably informed first, but with further evidence mounting against Maclean. Burgess continued to lead a busy social life, being seen at several clubs, and lunching or dining with Maclean, and again with Footman, and meeting Tomás Harris, Halpern, Miller (his pick-up from the Queen Mary), Blunt, Pollock, Kemball-Johnston, and even his one-time headmaster at Eton, Robert Birley. His solitary drinking was recorded, which proves that a watch was being maintained on him. It was almost as if he was keen to gain attention, and to drag as many of his friends into the whirlpool that would be created when he left the country. One has to wonder what this garrulous individual said about his emotional stress and predicament to these close friends.

Burgess and Maclean made their infamous escape when Burgess, on the evening of May 25, picked up Maclean at his house, in Tatsfield, Surrey, and drove to Southampton, where they boarded the Falaise. The official MI5 account claims that Maclean’s absence was not noted until May 28. In his 1989 book, Molehunt, Nigel West, relying on MI5 insider information, asserted that a watchful Immigration Officer had noted Maclean’s identity when he passed through the port, and had alerted Leconfield House. The lack of acknowledgment of that tip might encourage theories that MI5 were in no haste to prevent the duo’s departure. West’s account is useful, although he is mistaken over the timing of the interrogation plans for Maclean, and he is also adamant that Burgess had not come under suspicion before he absconded – something we now know is not true. West includes the feeble White Paper written by Graham Mitchell concerning the defection, issued on September 23, 1955, as an Appendix to his book. He identifies multiple errors of fact in Mitchell’s text.

Phase 2: May 25 to June 2

Goronwy Rees had left for Oxford on May 24, to attend a meeting at All Souls, where he was the Estates Bursar, and he consequently missed some important action. Burgess had started the day on Friday May 25 by calling Footman, and then speaking to Blunt, where he gave his listeners a false alibi, telling them that he would be helping a friend over some difficulties during the weekend, but looked forward to having dinner with him the following week. After trying to contact W. H. Auden at the Spenders’, Burgess then apparently called the Rees household, wanting to speak to Margie. (He presumably knew that Goronwy would be away.) The events were recalled by Rees in his memoir, and were later described to his MI5 interrogators. There is an incongruous aspect to the account.

Margie called her husband on the morning of May 26 (Saturday), asking him whether Guy had come to Oxford to see him. She posed this question because Blunt’s boyfriend, Jimmy Hewit, had just called her in some agitation, as Burgess had not returned to the flat on Friday night. When Goronwy expressed only mild surprise at such an absence, she then informed him that Guy had telephoned her on Friday morning, but had rambled on in a very incoherent fashion. Rees again was not much perturbed, but it was not until he returned home on Sunday evening that his wife told him more about the conversation, which, rather oddly, Rees states occurred ‘the previous Friday’. Guy had implied that he was about to perform some startling act, and that he would not see the Reeses for some time.

Why had Margie waited until she saw her husband to describe the essence of Guy’s call? And, why, given what Guy told her, would she imagine that he might have sought her husband out in Oxford? Her behaviour simply does not make sense. Goronwy does not comment on the irrationality of her communications, but instead jumps to a highly controversial conclusion, interpreting Guy’s implied departure in the following terms: “ . . . having got so far I suddenly had an absolutely sure and certain, if irrational, intuition that Guy had gone to the Soviet Union.” Well, yes, intuitions are by definition irrational.

I believe Rees loses much credibility here. According to the book, he knows nothing about the Maclean investigation and threat to him, he believes that Burgess had probably given up his espionage some years before, and he recognizes only a vague friendship between Burgess and Maclean. He has recently dismissed Burgess’s absence as trivial. And then simply because of a puzzling speech by Guy to his wife, he makes an enormous conceptual leap in concluding that his friend has fled to Moscow – something he tells his wife. It seems to me far more likely that Burgess had confided in Goronwy (and probably in Footman, as well) what was afoot, and that Rees had concealed from Margie what Guy had told him.

In any event, Rees jumped into action. He claimed that, late on that Sunday night, he phoned ‘a friend, who was also a friend of Guy’s and a member of MI6’ [in fact, David Footman]. (A few years later, in March 1956, as his scandalous disclosures were starting to appear in The People, he would recall that these initiatives did not occur until the Monday morning.) He told Footman that Burgess had apparently ‘vanished into the blue’, said that he might have defected to the Soviet Union, and that MI5 should be told. Footman was incredulous, but promised to inform MI5 of what Rees had said. The following morning, Rees received a message from Footman saying that he had done as requested, and that MI5 would be contacting him. Before that, however, Rees wrote that he told another friend of Guy’s, ‘who had served in MI5 during the war’ [i.e. Anthony Blunt] what he had done, and that this person, ‘greatly distressed’, insisted on coming to see Rees the next day at Sonning, and there made a convincing case to him that his accusations concerning his friend were based on very flimsy evidence. He pointed out that Rees had not done anything when Burgess had told him, a long time before, that he was a spy. Rees nevertheless was determined to tell the authorities what he knew and thought, much to Blunt’s chagrin.

One can imagine Blunt’s consternation at this time. Rees believes that he is doing his friend a favour by declaring that Blunt had terminated any information-passing to Burgess in 1939. Yet Blunt must know that his ‘indiscretions’ of 1944, treated then as a foolish but well-intentioned act in reaching out to the Soviet ally, will be interpreted very differently if MI5 discovers that his unauthorized disclosures had in fact started in pre-war days. It is no surprise that he is ‘greatly distressed’ and wants to talk Rees out of his plan.

Rees’s story then goes astray, however. He wrote that he went to MI5 the next day (i.e. May 29) and saw an unnamed MI5 officer, to whom he poured out his story, being rather surprised that he was listened to with utter seriousness. The officer then startled him by saying that Burgess had not departed alone: he had been accompanied by Maclean, which made Rees think matters were even worse than they were. He completes his chapter by saying that he stepped out of the office, and immediately saw the newspaper headlines announcing that two British diplomats had vanished into the air. A few pages later in his memoir, he repeats the timing of his meeting: “When I first told them I believed Guy had gone to Moscow, it was largely out of a sense of desperation and urgency. Guy had hardly been two days gone . . .”

There are several things wrong with this story. First, Guy Liddell’s diary states that Rees came to see him on June 1. Second, Rees would later make much of the fact that, when Peter Wright questioned him in 1965 why he had not informed MI5 earlier about his suspicions, he had to wait ten days until the Security Service invited him in: see KV 2/4607. Third, the news that two diplomats were missing did not appear in the British press until June 7, when the Daily Express had a scoop. * Fourth, while a record of the meeting does occur in Rees’s file (at KW 2/4603, sn. 3H), and Dick White refers to it in his recollections to Bower, Peter Wright was completely ignorant of this June 1 meeting between Liddell and Rees. Wright reminds Rees that he came to Leconfield House on June 6 to see Dick White, and Rees agrees with Wright’s statement.

[* Newspapers.com does not maintain Daily Express issues from that time. I instead present a Daily Telegraph item from a few days later.]

Now it is possible that, in 1972, when Rees was completing his memoir, with his memory possibly impaired by drink, he might have conflated two meetings, but the circumstances are such that it appears he wanted – or was instructed – to bury the June 1 encounter with Liddell. It was definitely White who informed him, on June 6, that Burgess had been accompanied by Maclean, at which Rees feigned such surprise, but the build-up to those conversations was so extraordinary (as I shall explain in the next section) that it stretches the imagination to think that Rees could have got the details so wrong. He incidentally also dithered evasively to Wright in 1965 concerning the truth of whether he had called Blunt immediately after phoning Footman, something he had no trouble affirming when he wrote his memoir.

Rees also claimed to Wright at that time that all that he had told Footman on May 27 was that Burgess was missing, and that he had definitely not told him the whole story. It makes Rees’s claims in his memoir look even more threadbare. Yet Rees persevered with his original assertions, no doubt thinking that any MI5 records would remain secret. Indeed, Andrew Boyle, in The Climate of Treason (which relied very much on Rees’s disclosures to him) reported that Rees told him that he had informed Footman of his suspicions about Burgess and Moscow, and that Footman confirmed that Rees indeed told him that over the telephone. Boyle also reinforces the account that any meeting that Rees held with MI5 did not take place until much later (he actually states June 7), thus implying that Rees tried to conceal his June 1 meeting with Liddell from the author.

Liddell’s diary entry is perfunctory, and not very useful, but it shows little sign of shock, given that, at the time, Liddell and White knew only that Burgess and Maclean had disappeared in France, and, perhaps surprisingly, harboured no hunches that they might have moved on to Moscow. He wrote: “Garonwy [sic] Rees came to tell me about a conversation his wife had with Burgess before the latter’s departure. I said that I would very much like to have as accurate an account as possible. He promised to do this in conjunction with his wife and let me know. He thought the conversation sinister.” Either Liddell was being very deceptive and cagey, or Rees had backed off at the last minute from his intuitions, or perhaps he had even invented his description of them to Footman for the purposes of spicing up his memoir. What is also very suspicious is that accounts of the exchange that appear in Rees’s file in April 1956 state that Liddell ‘received a message’ from Rees that day: for some reason, somebody was anxious to conceal the fact from the officers in B Division that a meeting between the two had actually taken place. That misrepresentation was echoed in R. T. Reed’s note to file on June 6, where he states that ‘Geronwy [sic] Rees telephoned Captain Liddell last week to say that REES’ wife, MARGIE, had a very ‘alarming’ conversation with BURGESS the day before he left this country.’

Liddell’s diary entry was a verbatim reproduction of a memorandum that Liddell posted in Rees’s file that same day, which proves that Liddell’s fellow-officers (e.g. White, Reed, Robertson, and much later, Wright) should have known about the conversation. It does not display any element of outrage, which one might have expected if Rees had related his full story, including his own, and Blunt’s, transgressions, and his strong belief that Burgess had fled to Moscow. Of course, he was not supposed to know of Maclean’s disappearance (and maybe he did not), and, if he had leaked that, he would surely have raised the alarm, and would have been brought in for sharper questioning. Liddell’s note has been delivered in a very low-key manner, although Reed the same day imaginatively interprets Rees’s statement that Burgess’s comments were ‘alarming’ that it ‘presumably means that he intended to go to Russia’. This is a very paradoxical entry: was Reed much sharper than Liddell, or was he merely echoing what the Deputy Director-General had hinted to him orally? Liddell’s opinion about Burgess, expressed a couple of weeks later, might indicate the former, even though the March 1956 entry (see above) attributes the statement about Russia to Liddell himself. In any event, Dick White’s team in B Division was further along in the investigation than White later claimed.

The initial conclusion might be that Rees had been persuaded by Blunt to restrain his disclosures, and stick to the bare facts, which immediately casts doubt on how much Rees told Footman on the Sunday evening, and how little Footman in turn passed on to Liddell. Yet events were a little more complicated, I suspect. I judge that Blunt was not aware of Rees’s meeting with Liddell on June 1, and that he believed that his successful later insertion into the interview with Dick White was part of the first encounter that Rees had with MI5 officers.

[As an aside, Tom Bower presents an utterly incongruous account of the events of this week. He has Blunt calling Liddell on the morning of May 29 (the reason not given), when we know from Liddell’s diary that Blunt had been out all day, and that Liddell had called Blunt that evening. According to Bower, Liddell then confided in Blunt that Burgess had disappeared, and Blunt feigned surprise. Bower’s other illogical observations concern Rees’s lunch meeting with Liddell ‘later that week’. He declares that one outcome of that meeting was that Liddell ‘fell under suspicion as a Soviet agent’. That would imply either that Rees at the time expressed that view to other MI5 officers, or that Liddell learned of that belief from Rees himself, and passed it on to White and company. It is all very nonsensical. Rees did much later voice his concern (to Wright) that Liddell might have been a Soviet agent, but Liddell had been dead for several years by then.]

As Liddell’s diary entry confirms, however, he had instead, on the evening of May 29, asked Blunt what he knew about Burgess’s disappearance – perhaps as a reaction to Footman’s message, wanting to consult his friend before he met Rees. Blunt volunteered to him that he knew that Hewit had reported Burgess missing. The next day, Blunt and Tomás Harris (the MI5 officer who had been GARBO’s minder, and who was later also suspected of being under the control of the Soviets) came to see him, and Liddell (rather irresponsibly) told them that Burgess had left the country with another Foreign Office official. Thereupon Blunt asked whether that official was Maclean. Liddell confirmed that it was, at which Blunt gave his thumbnail sketch of Maclean, saying how astonished he had been at returning to Cambridge in 1934 to find that he and Burgess, as well as Cornford and Cornforth, had drifted into the Communist camp.

Blunt and Harris then shifted gears. They explained that they had come to their supposition about Maclean because Burgess had told Blunt that he would, that weekend, be having to help a friend who was in some sex trouble and was being blackmailed. The pair had speculated that the friend might have been Maclean, since he was known to be a homosexual. The three of them then discussed the money that Hewit had found in Burgess’s luggage when he returned from America, and pondered over its source – from the Russians? Lastly, Liddell gained an assurance from the two of them that they would not disclose to anyone that Burgess had been accompanied by Maclean. Yet the naive Liddell had already gone too far, disclosing such information to outsiders. His action in seeking out Blunt, and speaking confidentially to him, suggests to me that he had no inkling of the seriousness of Rees’s charges at the time. Moreover, Blunt and Rees must surely have discussed the matter in depth by then.

Liddell was also to enjoy a long discussion with Harris on the night of May 30, since Harris and his wife had the previous Wednesday entertained Burgess, who had apparently become quite emotional. Burgess had burst into tears when asked about Kim Philby, avowing how wonderful Philby had been to him. Liddell showed how out of touch he was with the whole situation by writing in his diary: “There may possibly be some significance in this, in spite of everything the Philbys had done to keep him straight, he had betrayed Kim through getting to know something about the MACLEAN case and acting on the information. There is no doubt that Kim Philby is thoroughly disgusted with BURGESS’s behaviour both inside his house and outside it.” Thus did the finest mind in British counter-intelligence work, with his firm belief in the good nature of those persons he liked: hoodwinked by Blunt, Burgess, and Philby, and even forgetting his recent (1947) suspicions about Philby, Liddell seemed to lag the insights then held by his protégé, Dick White, about the menace represented by him.

Dick White returned from Paris on June 1, and Liddell was able to tell him that Blunt had been ‘helpful’, and to describe his meeting with Rees earlier that day, explaining that he had asked Rees to provide a written account of the Burgess phone-call. But how much did he tell? He surely did not let White know that he had revealed to Blunt and Harris that Maclean had been the official who had accompanied Burgess (see below). My belief is that Rees had communicated to Liddell his serious accusations, but that Liddell had instructed Rees to write a much less incriminating report, and instead to save his critical exposures concerning Blunt and Burgess in 1939 for his session with White. Liddell thus posted a harmless note on file, failed to give White the full details, and tried to wash his hands of the whole business. It was all too painful for him. Yet the record of the ‘meeting’, not just a telephone conversation, endured.

Saturday June 2 was a working day: Liddell also engaged Blunt to explore possible places in France and Italy where Burgess and Maclean might have stayed. Then Liddell left for his week’s holiday in Wales, delegating the management of the case to White, having advised Sillitoe on his coming visit to Washington to appease the FBI. It was not the most auspicious time to take leave, but, as readers may recall when Philby explained the dalliance over the Volkov business in 1945, leave arrangements were treated with a high degree of respect in the intelligence services. Liddell felt he probably needed a breather, given what Rees had told him, but to absent himself while Rees was creating his report was very eccentric. He was nevertheless much more comfortable delegating everything to White, and letting him sort out the Blunt problem.

Phase 3: June 4 to June 12

Monday June 4 was a busy day for White, having to deal on his return to the office with a clumsy memorandum from Philby attempting to distance himself from Maclean, and to set about organizing the final dossier on Philby and Burgess. Arthur Martin took over preparing a brief for Sillitoe should his planned trip be finalized. Obviously pre-occupied, White agreed that no further interviewing of Rees should occur until his report had arrived and been digested. Little happened on June 5, although plans were being made to recall Philby, and MI6’s Drew left for Washington with a letter to be handed to him. Telephone intercepts allowed Blunt and Hewit to be overheard discussing how depressed Goronwy and Margie Rees were.

The next day (June 6) Rees handed his statement to Footman, who delivered it to White at 2:30 pm. The formal interview could now take place. Yet again, Rees’s account (as he passed on to his daughter) does not hold water. In Looking for Mr. Nobody, Jenny Rees writes: “When Rees met Guy Liddell, on 7 June [sic], he was surprised to learn that the meeting was not to take place in an office, but at an informal lunch. When he arrived, he was even more surprised to find Blunt there, too.” This is absurd, since Liddell was of course in Wales at the time. And in fact it was White who experienced the surprise. Rees’s MI5 file suggests that White was taken aback when Rees turned up for his interview (on June 6, incidentally) accompanied by Blunt! What is also outrageous is the fact that, in March 1956, after Rees had had his scandalous stories about Burgess published in The People, provoking fresh interest in him by MI5, he told Reed that, on the morning of his interview (on May 29!), he had dropped by at Blunt’s flat, and Blunt had insisted on accompanying Rees to the meeting . . . (See KV 2/4605 sn.165a)

A very amateurish recording of the meeting was made. White had hardly had time to read Rees’s report, since the time-stamp on the meeting reads as 3:10 pm. Yet what Rees put together was underwhelming. Far from spilling the beans on Burgess’s shady past, and Rees’s suspicions of him, Goronwy had put together an anodyne document that hardly touched on the dynamics of the Margie-Guy conversation as he represented it in his book. The report is spent largely describing Burgess’s professional problems, saying nothing about any communist links. Contrary to how Margie had characterized Guy’s demeanour beforehand, Burgess comes across as coherent, almost sensible. Only in the last sentence is a suggestion of turmoil hinted at: “M. said that during the conversation she had the impression that, if G. had come to some decision, he had only just made up his mind and had not made any definite plan.” This was a very timid performance by Rees, and sharply shows that the testimony he later provided in his memoir was an undignified show of braggadocio. If his report did truly correspond to what he had told Liddell a week beforehand, it is no wonder that the Deputy Director-General did not get excited. On the other hand, as I have suggested, Liddell had probably instructed Rees to turn in a very subdued account.

White made several mistakes in trying to interrogate Blunt and Rees at the same time. He should have rejected their group approach and insisted that they be interrogated separately. He should have prepared himself for the encounter, so that he knew what questions to ask, and would not have been caught out in so many mistakes of memory or ignorance. And he should have arranged for a proper transcription of the exchanges. As it is, the record is a technical failure, and an intelligence disaster. One outcome, however, of Rees’s stumbling effort to describe Burgess’s experience with the Comintern in the 1930s, and Rees’s and Blunt’s involvement with him in 1937, is that Rees was obliged to write up a more coherent account of what he admitted during the interview. And he did so immediately afterwards.

While it is difficult to unscramble the flow of the discussion from a very garbled transcription, White’s lack of reaction to what Rees (who dominates the briefing) says is extraordinary. He does not appear to be unduly perturbed when Rees describes Burgess’s association with the Comintern, and Blunt’s involvement in passing information to him. When Rees states that ‘Anthony was of course working for him’, White merely interrupts mildly, saying: “Can we stop a second – Were you consciously doing that, Anthony?”. When Blunt replies ‘No’, White simply echoes the ‘No’, but Rees then carries on in full flow before White can pick up the thread. White must have recalled the Comintern connection from Burgess’s aborted trip to Moscow with Isaiah Berlin in 1940 (see Misdefending the Realm, Chapter 4), and Blunt’s being detected passing on secrets to the Soviets in 1944. At this juncture, White should have reacted with horror at the news that Blunt had a possible espionage track-record going back over a decade, and had been helping Burgess in the 1930s. Either he was simply very slow on the uptake, or it came as no real surprise to him, since Liddell had already confided in him, and he concealed his horror. I suspect the former: he was simply overwhelmed, and his head was in a spin.

White does not give a very poised performance. He appears confused over the list of names of furtive Burgess cronies given to him by Rees (e.g. Katz, Arnesto, Pfeiffer). In any event, White suddenly discloses that Burgess was not alone when he disappeared, saying, with a Bondian flourish: “He’s not alone. He’s with a man called Maclean. Donald Maclean”, as if his two interlocutors would not have known who that person was. A few minutes earlier, Rees had even mentioned Maclean’s name alongside that of Blunt as one of those ‘who always worked with Burgess’, but White could not have been thinking clearly. Moreover, he was also unaware that Liddell had already confided in Blunt (and Harris) that Burgess had been accompanied by Maclean. So much for close cooperation: Liddell had not told him all.

At the close of the meeting, Rees was then instructed to provide a write-up of what he had just said. I do not believe that his report has been reproduced anywhere: it should be. I extract from it the following main points:

- Rees knew Burgess as an active Communist in 1932-1933. He left the Party in 1935, an action that offended many of his friends.

- After the rift, Rees became friendly with Burgess again in 1937.

- Burgess told Rees that he had left the Party under direction, and was now working for the Comintern.

- Burgess sought help from Rees, and stated that Blunt was also assisting him with information.

- Rees believed that Rolf Katz and Edouard Pfeiffer were two of his Communist associates, and he thought that Burgess was acting as an intermediary between Daladier and Chamberlain.

- Burgess told him that he passed on information to a Russian whom he met in small cafes.

- After the Nazi-Soviet Pact was announced, Rees told Burgess that he wanted nothing more to do with his organization. Burgess said that Blunt was of the same mindset.

- Burgess pleaded for silence over the relationship: Rees told him (untruthfully) that he had deposited a statement about it in his bank.

- Rees nevertheless said that he believed that Burgess had given up his pro-Soviet commitment at the time of the Pact.

- Since then, and especially recently, Burgess had expressed anti-American views.

- May 7 was the last time that Rees saw Burgess, but the latter had a strange and long conversation with his wife on May 25, on which Rees had reported elsewhere.

I believe that Numbers 4 and 7 are the most important items in this statement – Rees’s explicit incrimination of Blunt as a communist sympathizer like himself, who had similarly been assisting Burgess in his criminal endeavours, but who reputedly had abandoned his ideological commitment in September 1939. This should have been a red flag to White. It was the outstanding fact that Liddell did not want to deal with.

Yet it was this confession that White later stated brought him to apoplexy, in the way he described it to his biographer. White claimed that he challenged Rees on why he had not come forward beforehand, to which Rees responded that he thought that MI5 knew all about Burgess’s background. Both men were distorting what happened to aid their particular mission: Rees to conceal his moral dilemma, White to assert his individual ignorance about Burgess’s accepted misdemeanors, and to blame someone else for MI5’s institutional failure. What is important to underline, however, is that this statement was not made by Rees when alone with Liddell soon after the disappearance, as Rees claimed, but to White, in the company of Blunt, who must have been compliant in the story Rees told. (Bower’s account is muddled and chronologically wrong, by the way. For instance, he introduces Rees’s accusations against Hampshire and Liddell being made at this time, which is patently untrue.)

Unfortunately, Jenny Rees is responsible for further confusion surrounding these events, mixing up the chronology. She has her father meeting Stuart Hampshire ‘shortly after Guy and Maclean had disappeared’ at a party, where Rees expressed his terror over a meeting he was soon to have with Jim Skardon. (Yet Rees had no planned meeting with Skardon at this time.) Rees had confided in him that Blunt had been an agent, too, and Hampshire, to his eternal shame, admitted to Jenny that he had advised Rees to do nothing, and let MI5 sort it out for themselves. Yet Jenny places this before the June 7 meeting, and associates it with Rees’s accusations against Zaehner and Liddell, which happened much later. She also quotes what Rees reputedly wrote after the June 7 meeting with Liddell [!], in which Rees claimed that Liddell and Blunt tried to talk him out of his delusions about Burgess. (I cannot trace this passage: it is certainly not in A Chapter of Accidents, and Jenny Rees provides no sources.) Rees claimed he dug his heels in, and then, a few days later, kept a further meeting with Liddell and White. It is another sorry mess.

Yet there was a June 7 meeting, this time between White and Rees alone, which was also recorded – and with greater quality than that of the previous day. This time, White and Rees chat as if they were old friends, and they try to identify the roots of Burgess’s alienation, discussing Burgess’s friends and associates, and, after a tortuous discussion, coming up with the name of James Klugman as a probable recruiter. Rees also voices his suspicions about Footman. The whole exchange is very rambling, and does not reveal much, except to point out that White and Rees obviously enjoyed a collegial relationship, and the exchange was not at all antagonistic in the way White framed it later. White was far more perturbed about Blunt than he was angry with Rees.

Nothing dramatic concerning Rees happened for a few days. White was busy arranging for Martin to accompany Sillitoe to Washington, charged with taking the dossier on Philby and Burgess with him. The same day that Sillitoe and Martin flew out of London, Philby was in the air returning to Britain, and White prepared to interrogate him immediately he arrived, on July 12. Liddell had returned from his leave on June 11 (Monday), and he started catching up with what had happened in his absence. White updated Liddell on the meeting with Rees and Blunt, indicating that he had gained an unfavorable impression of Rees, who seemed very nervous, but White apparently did not tell Liddell about the more amiable discussion the following day. Liddell would surely have mentioned it in his diary if he had.

Liddell did record that King George VI had shown an interest in the case, and had requested that Liddell speak to the King’s secretary, Tommy Lascelles. Liddell said there was not much more to tell than could be read in the newspapers, and that the disappearance of the pair was probably due to blackmail or ‘to some espionage past’. He went on to write: “I was a little inclined to fear the latter, only there was no firm evidence on which to do beyond the fact that both parties had gone through a period of Left Wing activities while at the University. It seemed to me unlikely that a man of Burgess’s intelligence could imagine that he had any future in Russia, and I was rather forced to the conclusion that he might have thought that his past was catching up with him and the alternative was a stretch in Maidstone gaol.”

Yet this assessment was contradicted by a later diary entry for that day. After describing White’s experiences in interrogating Philby, and positing that Burgess may have had access to secret files on Philby’s desk, Liddell brings up the Volkov incident, and how badly it reflected on Philby’s role. He then records having dinner with Blunt, who felt he was being hounded by the Press – a revealing declaration that proves that the Burgess-Blunt association was public knowledge. “No new facts emerged”, Liddell wrote, “except that I feel certain that Anthony was never a conscious collaborator with BURGESS in any activities that he may have conducted on behalf of the Comintern (vide Rees’s statement).” At least White had informed Liddell about the Comintern connection, but it was a very lazy and unimaginative conclusion by Liddell, who was too trusting of what Blunt told him, and still reluctant to face the truth.

Phase 4: June 13 to August 27

Meanwhile, Rees was undergoing further setbacks. His ‘confession’ prompted Reed, on June 14, to submit a Home Office Warrant request to tap his telephone. When Burgess’s flat was searched on June 7, hundreds of letters addressed to him had been found in a guitar-case at the bottom of his wardrobe, including a few from Rees, which might have been incriminating. (Source: KV 2/4605, sn. 177a). And an enterprising journalist had uncovered telephone records from the Reform Club, which showed that Burgess had called the Reeses at Sonning just before he absconded. The Reeses’ house was soon besieged, and Goronwy and his family were severely harassed.

Yet Rees in fact enjoyed a brief respite from MI5’s attentions. The tranche of letters discovered in Burgess’s flat prompted a broader large-scale inquiry, with multiple new files opened and acquaintances interviewed, with the Rothschilds in particular becoming a focus of attention. Martin and Sillitoe were still in Washington, and the ruse to plant the dossier on Philby and Burgess was proceeding satisfactorily: they returned to London on June 18. White’s interrogation of Philby was inconclusive, but Menzies was persuaded that Kim would have to resign from MI6. Liddell reported that awkward questions had been asked in the House of Commons concerning the lack of screening of Burgess, and on June 23 Prime Minister Attlee agreed to set up a committee, under Alexander Cadogan, to investigate Foreign Office security.

Rees then drew unnecessary attention to himself. He gave an interview to a reporter from the Daily Mail, which resulted in a story headlined: ‘Burgess: One of the Nicest Men I Know’ appearing on June 18. Starting by saying ‘To my knowledge he is not a communist’, Rees went on to offer a grovelling defence of Burgess as a patriotic Englishman who would never harm his country. He attributed any eccentricities of his conduct to a fracture of the skull he incurred a few years before when he fell down some stairs. Why Rees volunteered this hypocritical nonsense is unclear: the malfeasance of Burgess and Maclean was becoming very public, and MI5 knew that Rees had given strong evidence incriminating Burgess. It made Rees look very foolish, and MI5 eventually decided to haul him in again.

On June 19, Robertson noted that Rees had been suspected of helping the Soviets acquire equipment for making penicillin from America, something the USA had been trying to ban. (This was an extraordinary series of incidents, involving the defector N.M. Borodin, that merits detailed coverage. Rees was not honest about his business relationship with the writer Henry Green, and the Pontifex company, at a time when Rees was working for MI6. I plan to pick up this story in my November bulletin.) The same day, John Lehmann, in an interview by Jim Skardon, criticized Rees and Blunt for not notifying the authorities of the politics of Burgess and Maclean. Around this time, Lehmann’s sister, Rosamund, had informed MI5 of the fact that Rees had told her in the late thirties that Burgess was working for the Comintern: Skardon interviewed her in October 1951 to confirm her story. Rees had told Reed and Robertson on July 24 that he had confided in Rosamund. MI5 maintained the telephone check on Rees: when his wife phoned Hewit on June 27, they learned that Rees had been ‘in an awful state over Guy’, not sleeping, and weeping every night. Following some ‘unusual’ conversations between the Reeses and Blunt, on July 6 Reed requested a re-imposition of telephone checks on Blunt.

Liddell continued to come to Blunt’s defence. On June 27, he reviewed a report on Philby that MI6 was about to send to the FBI. He deemed that it was too sympathetic to Rees’s claims concerning Burgess and the Comintern, he trusted what Blunt had claimed about ignorance of Burgess’s affiliation, and he judged that Blunt would have been very unlikely to get involved in such political activities. Moreover, he expressed his disbelief that Burgess could have been ‘a Comintern agent or an espionage agent in the ordinary accepted interpretation of these terms’. So what had Burgess been running from? And, if Maclean, why not Burgess or Blunt? Liddell does not examine such ideas.

Nevertheless, the interest in Blunt increased. On July 7, Owen O’Malley, a retired Foreign Office diplomat, informed Sir William Strang, the Permanent Under-Secretary, that Blunt had been a Communist at Cambridge alongside Burgess. And Dick White asked Liddell to arrange an interview with Blunt in the light of correspondence found in Burgess’s flat. Liddell took the opportunity to have lunch with Blunt, and quiz him about his communist activity at Cambridge. Blunt finessed the issue, stating that he had taken an intellectual interest in Marxism, but had never been attracted by the Russian implementation of it, and reiterated his belief that Burgess had been working for British Intelligence. Liddell seemed impressed enough with this testimony to pass it on immediately to White and his lieutenants, recording that what he told them appeared to ‘dispel their suspicions’ on a number of points. Robertson and Martin accordingly interviewed Blunt on July 14, when he gave them an utterly mendacious account of his association with Burgess, suggesting that the disciplines of the Communist Party were objectionable to Burgess, and, again, that any information that he had given him was in the belief that Burgess was working for British intelligence.

Yet sharper counter-espionage officers would have asked more penetrating questions. How could it be that Blunt received such a different impression from that of Rees, never believing that Burgess was working for the Comintern? Why would Rees have implied that Blunt was assisting him in that goal? Had Blunt not been a communist himself? (It seems that Robertson and Martin had not been informed that Blunt had been suspended from an Intelligence course at Minley Manor in 1940 because of his communist sympathies.) And why would Burgess have been ‘stunned’ by the announcement of the Nazi-Soviet pact, if he had simply been working for British intelligence? Had Blunt really not worked everything out only when Rees recently told him that Burgess’s active work for the Russians had ceased? In that case, when had Blunt believed that Burgess had really been working for the Russians? Yet the opportunity was missed.

On July 18, Dick White wrote a letter to Rees, asking him in a friendly fashion whether he could ‘look in’ at the MI5 office for an hour or two the following week. The outcome was that Rees underwent a more searching interview by Robertson and Martin on July 24. Yet he immediately tried to control the process, refusing to provide a full account of his knowledge of, and association with, Burgess, but stating instead that he would simply answer direct questions. What ensued was not a very revealing exercise: overall, Rees stuck to his guns, although he tripped up occasionally, describing Burgess’s attention to security in contradictory fashion, and letting some facts slip out about which he had previously expressed ignorance. His representation of Burgess as ‘the most complete Marxist he had ever known’, while expressing doubt as to whether Burgess would have considered spying after 1939, was, to me, a very flabby argument, but was not picked up by his interrogators. Robertson and Martin concluded that Rees was holding something back, instead revealing a part of the story as an insurance policy against MI5’s discovering the facts on their own. They also made the significant observation that ‘he may also have conferred with BLUNT before making his statement in order to give BLUNT the opportunity of producing his own denial’. They also noted that Rees had been very keen in trying to elicit from the two of them whether his statements concerning Burgess had been confirmed by any other source.

After reflection, Robertson wrote a note to White concerning the interview, in which he repeated some of the frustration arising from Rees’s evasiveness and contradictions. He pointed out the curious manner in which Rees and Blunt had presented themselves at the office to volunteer a statement, and then he turned the spotlight on Blunt, who seemed to him to have much more to lose because of his public position. “It seems to me very possible”, he wrote, “that, REES having informed BLUNT that he could no longer withhold from the proper authorities at least a part of what he knew about BURGESS, the two men came to an agreement whereby each would make a mutually agreed statement. This agreement would include an understanding that REES, in implicating BLUNT in Burgess’s activities, would do so in a manner that would not prevent BLUNT from denying it convincingly.”

This was a shrewd observation from Robertson, but his follow-up was less than stellar. He had suggested to Liddell himself that the latter ‘attempt to draw’ Blunt on the subject before the latter left for Greece, but the opportunity had not arisen. How a softball approach from Liddell, Blunt’s crony, might extract any breakthrough insight is not clear, but then Robertson himself displayed a similar indulgence towards Blunt. Addressing his boss, White, he wrote: “I should be grateful if you could now reconsider the matter yourself, with regard to the possibility of our telling BLUNT, on his return to this country, that we do not accept the truth of his statement unreservedly, at the same time guaranteeing to him (if you think we can go so far), that he will not suffer in his career or reputation, if he tells us with complete frankness of his knowledge of BURGESS’s espionage.”

This was a dramatic conceptual leap: suddenly considering immunity from prosecution for someone who had apparently been treated as a loyal ally up till then. Thus did the steely minds of MI5 deal with potential traitors in their midst. White could not have been happy that his junior officers were now starting to suspect Blunt. Maybe he had put Robertson up to this suggestion: White referred the memorandum to Liddell, and asked whether the Deputy Director-General would be prepared to interview Blunt. But nothing happened for a while. By the time Blunt returned from Greece, Liddell had left for the USA, being absent for the whole of September. Nevertheless, Liddell had time to issue a more disciplined riposte to White, who, on August 27 (having just returned from leave himself) reported to Robertson that Liddell had firm objections to giving Blunt open assurances without any considerations of the consequences of what he might say. (Liddell’s lack of expressed surprise at this initiative is telling: it was a canny attempt to cover his back.) White minuted to Robertson that they would have to re-think their strategy. It is clear that White again would have preferred that the whole matter be hushed up. Thus did the days of summer wind down, and the intensity of the investigation fade away. Not long afterwards, an officer in MI5 was present at a cocktail party also attended by Rees, and the latter was notably relieved to learn that the officer’s interpretation of events was that the BURGESS/MACLEAN case was being dropped.

Conclusions

Guy Burgess created havoc before he absconded. Aware that he was being watched, he drew in as many of his friends and associates as he could, leaving an obvious trail behind him. The cause of this may have been a degree of spite, not seeing why he should be singled out for banishment, but it may have taken place with the objective of causing MI5 to spend an inordinate amount of time and effort in chasing down his links, and in that way distract attention away from Blunt. In this project, the Security Service may have trawled up one or two confirmed miscreants (such as Alister Watson), but they also interviewed at length a number of misguided leftists from the 1930s who were now reformed characters, and no danger to the nation. The fact that the Foreign Office had not sacked Burgess earlier, but instead searched to find him a comfortable job, is shocking.

Anthony Blunt played a wily game, but he should have been doomed. Even Goronwy Rees’s reduced accusations should have been enough to condemn him. He believed that he had shrewdly manipulated Rees, and for most of the summer of 1951 appeared to be able to exploit his good relationships with Guy Liddell and Dick White to present himself as a useful consultant rather than a potential candidate for conspiracy. He was able to gain some respite because of their absences, and the welter of other events. That situation would not last, of course, but he surely persuaded his Soviet controllers (who had ‘ordered’ him to defect as well) that he was more useful keeping a watchful eye on matters back in London, and frustrating MI5’s inquiries. The insinuations made against Blunt at the end of this summer confirm the fact that he was by then already under grave suspicion as a Soviet agent of some long standing.

MI5 itself was dysfunctional. It was led by an ex-policeman, Sillitoe, who had to cable back to London from Washington for instructions on sensitive matters. His deputy, Liddell, largely stayed out of the picture, recording his private impressions and thoughts in his diary, and failing to take a leadership role in the investigation of Maclean and Burgess. A single man again, he could not even consider cancelling his summer holiday at a time of great intensity for the project. That was possibly because he keenly wanted to adopt a low profile. He did not communicate regularly with White, head of B Division, who himself did not show the discipline appropriate for a mature counter-intelligence officer. White had started to guess as to the enormity of the errors that MI5 had committed in its indulgence to communist sympathizers, and he feared that any public acknowledgment of the recruitment disasters that MI6 and MI5 had undertaken would probably destroy his career, as well as the independence of MI5.

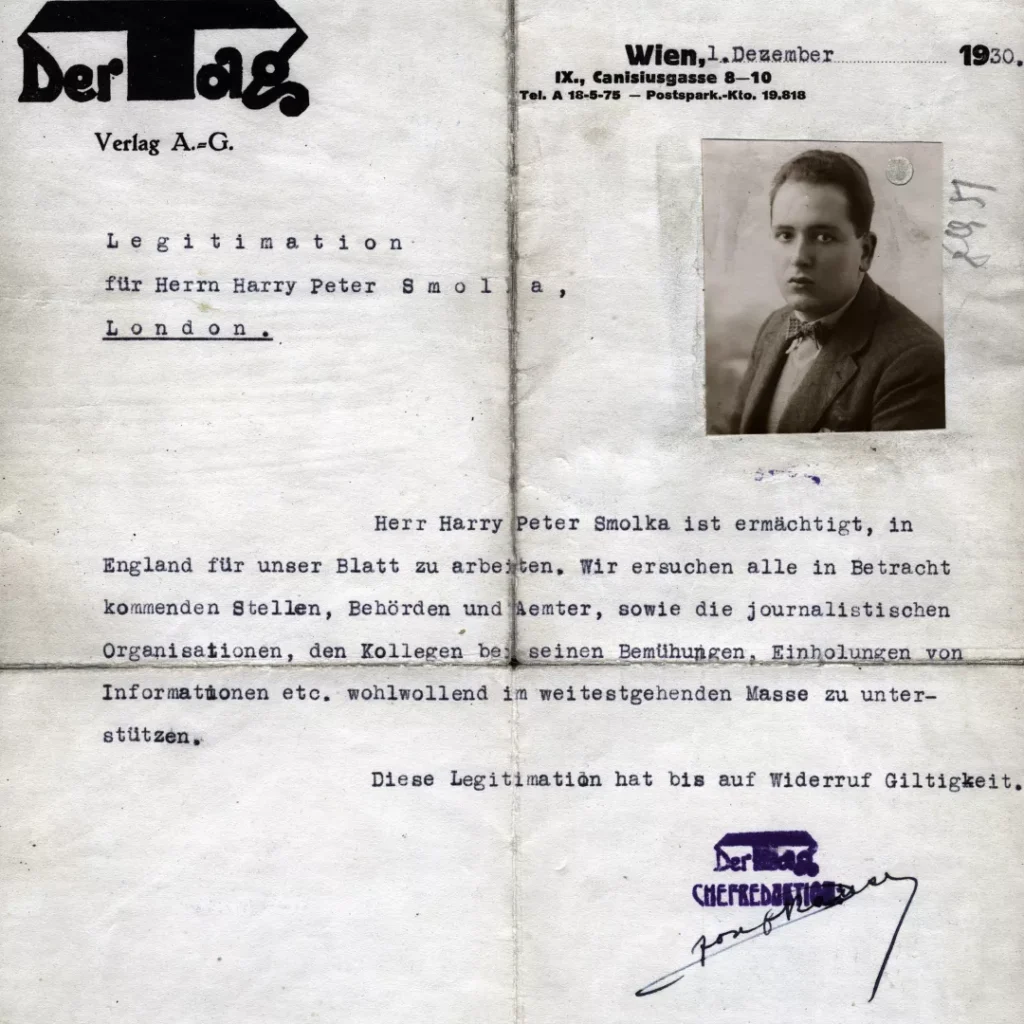

The problem was that MI5 had no strategy in place for proceeding after the probable guilt of Soviet agents had been established. VENONA evidence could not be brought to any trial, and a confession from the subject was thus a necessity. The latter tactic worked in the case of Fuchs and Blake (who were not true-blooded Englishmen anyway, and thus should not have been trusted), and with Nunn May, but the thought of bringing Maclean to trial, after he had confessed (as he was surely about to) must have filled the hearts of White and his colleagues with extreme nervousness, when the indulgences over (for instance) Maclean’s abject behaviour in Cairo would have been received derisively. The theory that Maclean had been allowed to escape should not be discarded completely, as it was a pattern with Philby and Smolka, among others. Moreover, the skills of the interrogators were inadequate. They did not have the historical training to understand fully the political background to the events. They ambled into their sessions unprepared, they were not briefed properly, they were too deferential, and they were outwitted by university graduates who demonstrated sharper mental acuity. Dick White was a poor role model.

The other aspect was the pretence that such suspects should be allowed off scot-free on the condition that they told their inquisitors everything they knew. It probably started here, with Blunt. Of course, this policy of granting immunity from prosecution was based on self-delusion. How would they know that the candidate would tell them everything, or that what was divulged was true? Yet the indulgence was considered, for the benefit of a quiet life. John Cairncross was encouraged to resign at this time when confidential notes from him were found in Burgess’s apartment, while MI5 at this stage had no idea about the duration, breadth and depth of Cairncross’s espionage. Liddell’s cautiousness in this regard was praiseworthy (thought it may have been a ruse), but it was not authoritative enough, and he was not to last much longer in MI5.

The most troublesome, but also revealing, event is the meeting between Rees and Liddell, which Rees stifled in his memoir, and the existence of which was later concealed from junior MI5 officers, being downgraded to a ‘telephone conversation’. Indeed, soon after the meeting, on June 6, Reed confirmed it as such, but indicated that Liddell had used the word ‘alarming’. My suspicion is that Rees did indeed tell all to Liddell, who demanded that he downplay his suspicions in his immediate report, and that he reserve his full disclosures for his future interviews with MI5, namely with White. Liddell sanitized the essence of the discussion in his diary entry and his posting to Rees’s file, gave a careless hint to Reed, but withheld the frightful news from White, preferring that White discover it for himself. If Liddell now began to harbour severe misgivings about Blunt, he did not share them, but his laconic response when reading White’s suggestion for immunity for Blunt indicates to me that he understood the severity of the problem. It took Michael Straight to accuse Blunt, and prompt his confession, over a decade later, but Rees’s fury over the lack of action undertaken against him would lead to the eventual exposure of the art historian.

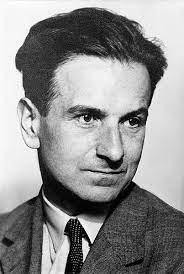

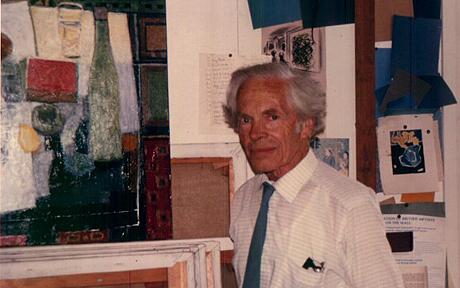

As for Rees, he comes out of this adventure with his reputation even more tarnished. It is difficult for me to understand how someone reputedly so smart as he (he was awarded a Fellowship at All Souls, after all) could be so gullible and impressionable. A mild flirtation with communism in the early 1930s was perhaps pardonable, but for him to reject Stalinism only in 1939, at the time of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, shows a cavalier and obtuse blindness to the evils of Stalin’s oppression and purges. (The photograph below shows Rees at the May Day Parade in 1935.) Moreover, Rees had visited the Soviet Union in 1935, and he could have seen for himself what Communism meant in practice.

His admiration for those two charlatans, Burgess and Blunt, is also astounding. Apparently impressed by Burgess’s brilliant mind, and his vivid and convincing explanation of Marxism, he was equally attracted to that woeful humbug, Blunt. And that breach in 1939 did not allow him to reset his opinion of Burgess, despite the latter’s admission that he had broken with Communism, and taken up the fascist chant, on Moscow’s orders. Thereafter, Rees showed, in his mendacious and self-serving memoir, that he himself was a humbug who could easily be manipulated by Blunt, and he did not have the courage to tell a consistent story. He lived and died in the belief that the archival records would never appear to disprove his story.

Five years later, his world would fall apart when he was reckless enough to sell his story to The People, in which he pointed the finger closely at Blunt, without naming him, but brought down bitterness from his former friends for making such outrageous accusations. By that time, he was furious that Blunt had managed to escape undamaged and protected while Philby had been hounded and expelled from MI6. That outburst leads me to believe that he at some stage learned much more about Blunt’s long-standing espionage and treachery. He may have shared this with Liddell alone, but he had to soften his accusations when he underwent his formal interrogations, since Blunt was present. He set out doing what he did what he did out of a desperate attempt to salvage his honour, and to protect him and his friend from criminal charges, but he ended up feeling betrayed by Blunt.

Envoi

This article was prompted by my correspondent’s noticing the initiative to offer immunity to Blunt as early as 1951, and that episode is the main driver of this revision of history. When I wrote about the dissimulation over Blunt’s confession three-and-a-half years ago (see https://coldspur.com/the-hoax-of-the-blunt-confession-part-1/ and https://coldspur.com/the-hoax-of-the-blunt-confession-part-2/ ), I noted that Arthur Martin had been credited with the idea of offering Blunt immunity, but regarded the gesture as highly dubious. The evidence in Rees’s file proves that the idea had been simmering for thirteen years.

Moreover, while other Prime Ministers had inquired of their Cabinet Secretaries the circumstance of the Blunt immunity deal (with Jim Callaghan perhaps being the most perspicacious), it was Margaret Thatcher who was obliquely required to draw attention to it. I quoted in my first piece part of her statement to the House of Commons in November 1979, and I reproduce the key paragraphs here:

It was early in 1964 that new information was received relating to an earlier period which directly implicated Blunt. I cannot disclose the nature of that information but it was not usable as evidence on which to base a prosecution. In this situation, the security authorities were faced with a difficult choice. They could have decided to wait in the hope that further information which could be used as a basis for prosecuting Blunt would, in due course, be discovered. But the security authorities had already pursued their inquiries for nearly 13 years without obtaining firm evidence against Blunt. . . .

They therefore decided to ask the Attorney-General, through the acting Director of Public Prosecutions, to authorise them to offer Blunt immunity from prosecution, if he both confessed and agreed to co-operate in their further investigations.

Yet I believe I accepted too much of what Thatcher said, and I misrepresented the facts back in February 2021. I wrote: “Straight was invited over to the UK in October [1963], where he briefed Hollis and White, and a highly confidential immunity agreement for Blunt was made with the help of Cabinet Secretary Trend, Home Secretary Brooke, and Attorney General Hobson.” I am now certain that the deal was not arranged until April 1964 – but was done in haste. When John Hunt, the Cabinet Secretary, in December 1978 described to Prime Minister Jim Callaghan the events, he declared that MI5 had approached the Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions on April 18, with a following exchange of letters, and that it was all set up for the ‘interrogation’ of April 23. A similar (but not identical) account, given by Robert Amstrong in November 1979, appears in PREM 19/120. Everything was performed with a speed uncharacteristic of the wheels of bureaucracy.

It was all part of the hoax. As the Times reported in July 2020: “The distinguished art historian was offered complete immunity if he confessed, a sordid deal with no legal basis that was agreed by the then attorney-general, Sir John Hobson.” Hobson was presented with a fait accompli, and he had to agree to it. An astonishing nugget from the Prime Minister’s folder on the case, PREM 16/2230, contains the following statement from the same John Hunt, written on July 3, 1974, and addressed to Harold Wilson, which carelessly confirms what happened: “Following his confession [my italics!] the case was referred to the Attorney General of the day (Sir John Hobson) who decided that the public interest lay against prosecution.” Thus the timing of the confession was staged to reflect Hobson’s approval after the event. The sequence could not have been spelled out any more plainly.