Contents:

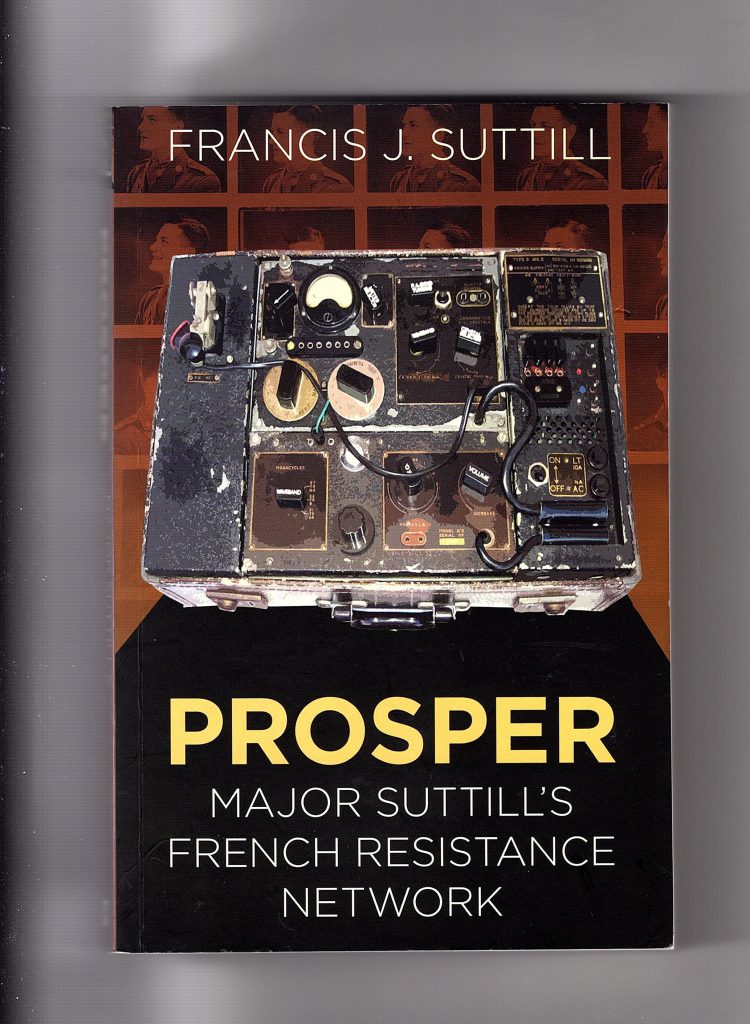

Denniston’s Honour

Secrecy over Bletchley Park

Polish Rumours

GC&CS Indifference?

The Aftermath

Conclusions

Envoi

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Denniston’s Honour

As I declared in my posting last December, my interest in the career of Alastair Denniston was revived by my encounter with some incorrect descriptions of the acquisition by the Government and Cypher School (GC&CS) of Enigma models, and evidence of decryption successes, from Polish Intelligence shortly before the outbreak of World War II. These anecdotes reawakened my interest in exactly what Denniston’s contribution had been. Irrespective of any mis-steps he may have made, I have always considered it inexplicable that Denniston, who apparently led GC&CS so expertly between the wars, should be the only GC&CS or GCHQ chief who was not granted a knighthood.

Now I am not a fan of the British Awards and Honours system. As someone whose career was exclusively in competitive commercial enterprise in the UK and the USA, my experience is that, if you did your job well, you kept it, or might be promoted, and if you failed, you were sacked (or demoted, or put in charge of ‘Special Projects’, or be moved over to an elephants’ graveyard, if your organization was large enough to sustain such an entity). Occasionally you could perform a stellar job, and still be sacked – probably because of political machinations. And the idea that someone should receive some sort of ennoblement because of his or her ‘services to the xxxxxxx industry’ displays a woeful understanding of how competitive business works.

Thus I am very antipathetic to the notion that awards of some sort should be handed out after a career that simply avoided noticeable disasters. (And in the case of one notorious chief of MI6, even that is not true.) It does not encourage the right sort of behaviour, and grants some exalted status to persons who have had quite enough of perquisites and benefits to sustain their retirement. Nigel West describes, in his study of MI6 chiefs At Her Majesty’s Secret Service, how senior MI6 officers were concerned that the pursuit of moles might harm the chances of getting their gongs.

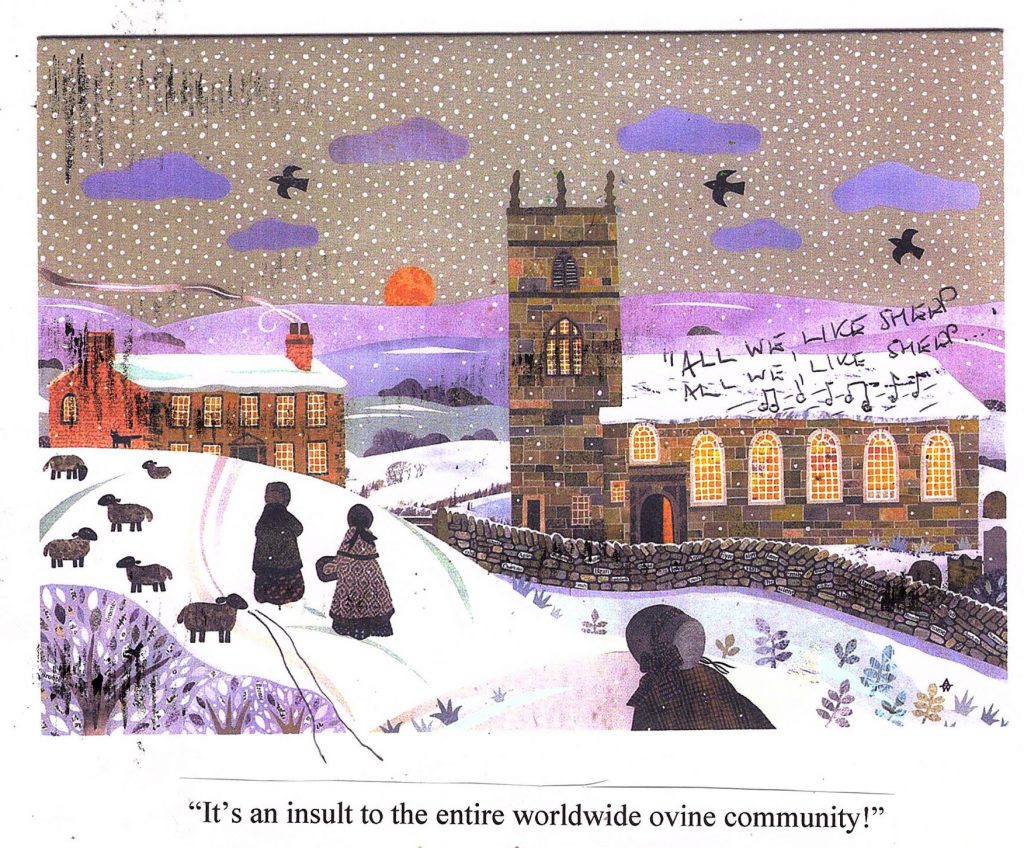

What is more, as I learned when studying SOE records, the level of an award is directly associated with the rank an officer of official has already received, which often meant that those most remote from the action were awarded ribbons and medals much more distinguished than those risking their lives on the frontline, such as those SOE agents who ended up with civilian MBE medals – quite an insult. I am also reminded of a famous New Yorker cartoon where one general is admiring all the ribbons on the chest of one of his colleagues, and points to one he does not recognize. ‘Advanced PowerPoint Techniques: Las Vegas, October 1998’, boasts the celebrated general. (I don’t see it at the cartoon website (https://cartoonbank.com/), but, if you perform a search on ‘Medals’ there, you can see several variations on the theme, such as ‘This one is for converting a military base into a crafts center’.)

As I was preparing this piece, I made contact with Tony Comer, sometime departmental historian at GCHQ, and he explained to me that, in June 1941, Denniston received only a CMG rather than a knighthood. But that did not make sense to me. Denniston was not demoted until February 1942. The notorious letter to Churchill that reputedly sealed his fate, composed by Welchman and others, was not sent until October 1941. What was going on? Fortunately, a follow-up email to Mr Comer cleared up the confusion.

Mr Comer patiently explained that the headship of GC&CS did not qualify, in Whitehall bureaucratese, as a ‘director’-level position. The CMG was indeed the appropriate award for someone at the ‘Deputy Director’ level. Stewart Menzies (who took over as MI6 chief from Sir Hugh Sinclair after the latter’s death in November 1939) was the director of GC&CS, and thus was entitled to the KCMG awarded him on January 1, 1943. In early 1942 Denniston was effectively demoted, while still maintaining the Deputy Director (Civil) title, after the mini-rebellion and his replacement as head of Bletchley Park by his deputy Edward Travis, now Deputy Director (Service). Denniston thereupon moved down to Berkeley Street to work on diplomatic traffic.

In 1944, Travis was promoted to full Director, while Menzies was promoted to Director-General. Travis was thus, owing to his newly acquired rank, awarded the KCMG in June 1944, despite having led the service for only two years, while Denniston, who had by all accounts performed very creditably for two decades (although he struggled during 1941 with the rapid growth of the department), was left out in the cold. Thus all Denniston’s valiant service as chief between 1919 and February 1942 was all for nought, as far as a knighthood was concerned. Since then, every chief of GC&CS, and GCHQ (which it became after the war) has benefitted from the raising of the rank to full directorship.

Thus it would appear that Denniston was hard done by, as several commentators have noted. For example, his biographer, Joel Greenberg, echoes that sentiment, albeit somewhat vaguely. In Alastair Denniston (2017), he offers the following opinion: “It is hard not to come to the conclusion that any public acknowledgement of AGD’s work at Berkeley Street from 1942 to 1945 might have drawn unwelcome attention to a part of GC&CS that the British intelligence community prefers to pretend never existed. Even the award of a knighthood to AGD might have raised questions about British diplomatic Sigint, both during the war and immediately afterwards.”

Yet this judgment strikes me as evasive and irrational. It would have been quite possible for the authorities to have awarded Denniston his knighthood without drawing attention to the Berkeley Street adventures. After all, as Nigel West informs us in his study of MI6 chiefs, when the highly discredited John Scarlett returned from chairmanship of the Joint Intelligence Committee to head MI6, at least one of the senior officers who resigned in disgust at the appointment (Mark Allen) was awarded a knighthood when he left for private enterprise. Moreover, Denniston was also treated badly when he retired in 1945. He was given a very stingy pension, and had to supplement his income by taking up teaching. This appeared to be a very vindictive and mean-spirited measure. Why on earth would Stewart Menzies have harboured such ill will towards a dedicated servant like Denniston?

I decided there was probably more to this story. I found Mr Greenberg’s book very unsatisfactory: it regurgitated far too much rather turgid archival history, without analysis or imagination, and frequently pushed Denniston into the background without exploring the dynamics of what must have been some very controversial episodes in his career. It was, furthermore, riddled with errors, and poorly edited – for example, the Index makes no distinction between the US Signals Intelligence Service and the British Secret Intelligence Service, and the text is correspondingly sloppy. I had an authoritative and technical answer to my question about Denniston’s awards, but continued to believe that there was more to the account than had been revealed, and suspected it had much to do with Enigma.

Secrecy over Bletchley Park

My main focus in this piece is on the pre-war negotiations over the acquisition of Enigma expertise. There is no question that Denniston struggled later, in the first two years of the war: his travails have been well-documented. He lost his boss and mentor, Hugh Sinclair, soon after the outbreak of war, and had to report to the far less sympathetic Stewart Menzies. A furious recruiting campaign then took pace, which imposed severe strains on the infrastructure. There were two hundred employees in GC&CS at the beginning of the war: the number soon rose into the thousands. Stresses evolved in the areas of pay-grades, billeting, transport, building and cafeteria accommodation, civilian versus military authority, as well as in the overall challenge of setting up an efficient organization to handle the overwhelming barrage of enemy signals being processed. All the time the demands from the services were intensifying. In the critical year of 1941, Denniston made two arduous visits to the United States and Canada, underwent an operation for gall-bladder stones, and suffered soon after from an infection. It was a predicament that would have tried and tested anybody.

But Denniston was a proud man, and apparently did not seek guidance from his superiors – not that they would have known exactly what to do. What probably brought him down, most of all, was his insistence that GC&CS was historically an organization dedicated to cryptanalysis, and should remain so, when it became increasingly clear to those in the forefront of decrypting the messages from Enigma, and carrying out the vital task of ‘traffic analysis’ (which developed schemata about the location and organization of enemy field units largely – but not exclusively, as some have suggested – from information that had not been encrypted), that that tenet no longer held true. A very close liaison between personnel involved in message selection, decryption and translation, collation and interpretation, and structured (and prompt) presentation of conclusions was necessary to maximize the delivery of actionable advice to the services.

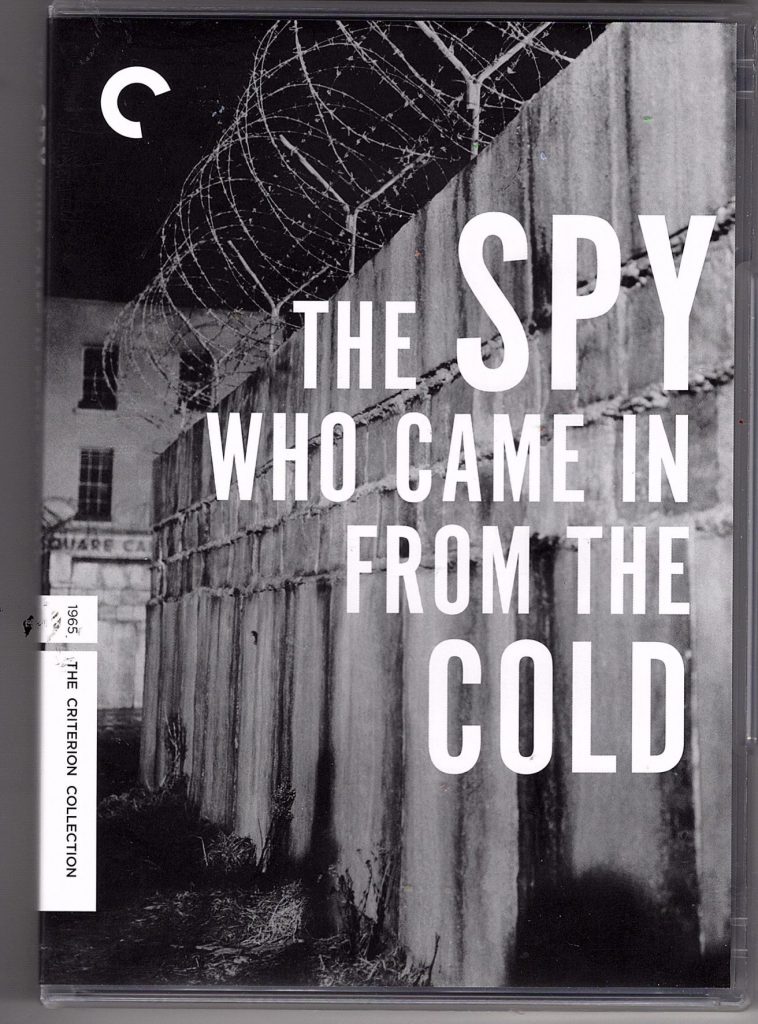

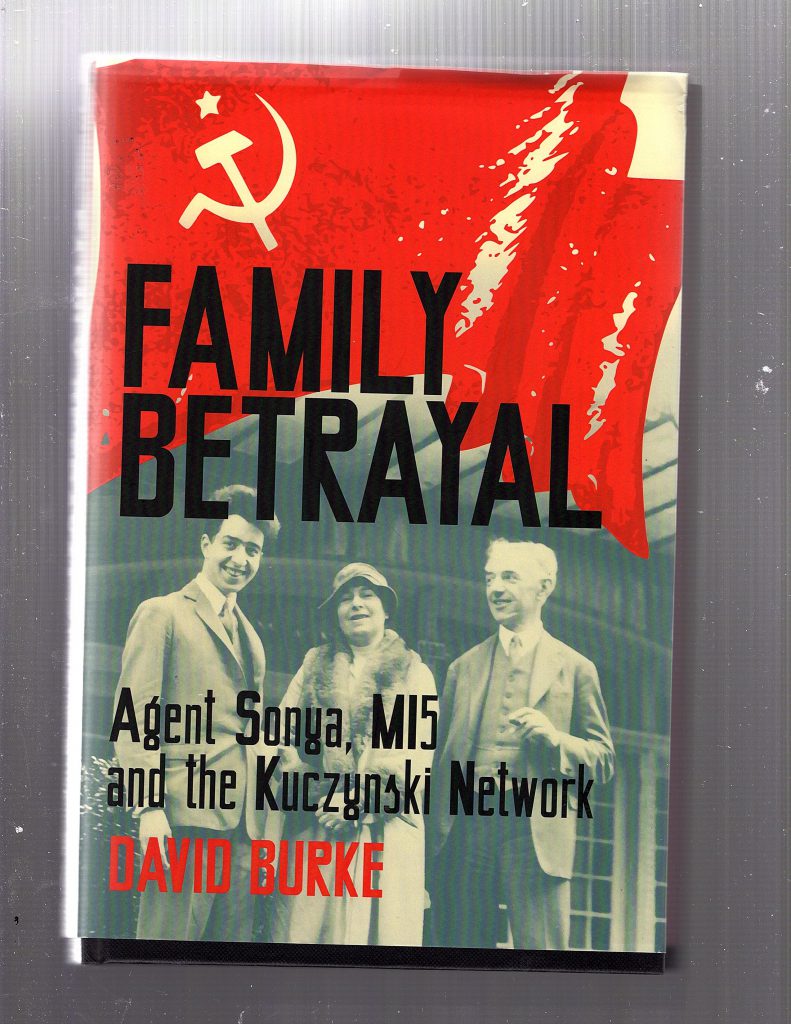

Yet it took many years for this story to appear. All employees at the GC&CS (and then GCHQ) were subject to a lifetime of secrecy by the terms of the Official Secrets Act – largely because it was considered vital that the match-winning cryptanalytical techniques not be revealed to any current or future enemy. It was not until the early nineteen-seventies that drips of intelligence about the wartime activities of Bletchley Park began to escape. The British authorities had believed that they could maintain censorship over any possible disclosures of confidential intelligence matters, but failed to understand that they could not control publication by British citizens abroad, or the initiatives of foreign media. This was a pattern that repeated itself over the years, what with J. C. Masterman’s Double-Cross System, published in the United States in 1972, Gordon Welchmann’s Hut Six Story, also in the USA, in 1982, Peter Wright’s Spycatcher, which was published in Australia in 1987, as well, of course, by the memoirs of traitors such as Kim Philby and Ursula Kuczynski.

As with the memoir of the Abwehr officer Nikolaus Ritter (Deckname Dr. Rantzau), which appeared in 1972, GCHQ was taken aback by the appearance in 1973 in France of a book by Gustave Bertrand, Enigma ou la plus grande énigme de la guerre 1919-1945. Bertrand had been head of the cryptanalytical section of the French Intelligence Service, and claimed that he had been prompted to write his account after reading a rather distorted story (La Guerre secrète des services speciaux français 1939-1945) of how the French had gained intelligence on a German encryption machine from an agent in Germany, written by Michel Gardet in 1967. Less accessible, no doubt, but probably much more revealing, was Wladyslaw Kozaczuk’s Bitwa o tajemnice [Battle for Secrets]published in Warsaw in 1967, which made some very bold claims about the ‘breaking’ of the German cipher machine that surpassed the achievements of the French and the English.

Thus, in an attempt to take control of the narrative, Frederick Winterbotham, who had headed the Air Section of MI6, and reported to Stewart Menzies, received some measure of approval from the Joint Intelligence Committee to write the first English-language account of how ULTRA intelligence had been employed to assist the war effort. (Note: ULTRA included all intelligence gained from message interception, decryption, translation and analysis, and was not restricted to Enigma sources.) Winterbotham had been responsible for forming the Special Liaison Units (SLUs) that allowed secure distribution of ULTRA intelligence to be passed to commanders in the field. His book, The Ultra Secret, appeared in 1974, and had a sensational but mixed reception, partly because many old GCHQ hands considered he had broken his vow of secrecy, and partly because he, who had no understanding of cryptanalysis, misrepresented many important aspects of the whole operation.

As an aside, I believe it is important to mention that Enigma was sometimes ‘broken’ (in the sense that it did not remain completely intact and secure), but never ‘solved’ (in the sense that it became an open book, and regularly decrypted). That distinction can sometimes be lost, and too many authoritative accounts in the literature refer to the ‘solving’ of Enigma. Dermot Turing’s recent (2018) book on the Polish contribution to the project, XY&Z, is sub-titled The Real Story of How Enigma Was Broken, and thus technically represents the project according to the distinctions above, but might give the impression that a wholesale assault had been successful. The Enigma machine was a moving target; before and during the war, the Germans introduced new features (e.g. additional rotors) that made it more difficult to decrypt. And each of the German organizations using Enigma deployed it differently. The degree of its impenetrability was very dependent upon the disciplines that its operators exercised in setting daily keys with their opposite numbers, and how casually they repeated text messages that could be used as cribs by the analysts. It supplemented very complex enciphering mechanisms (i.e. translation of individual characters) with the use of rich codebooks that allowed substitution of words and phrases with numerical sequences. Many variants of Enigma discourse were thus never broken. Mavis Batey’s biography of Dillwyn Knox is carefully subtitled The Man Who Broke Enigmas – but not all of them.

My approach that follows is overall chronological – to explore how the pre-war discovery of Enigma characteristics was understood and represented by various authors, and how the accounts of dealing with Enigma evolved. In this regard, it is important to distinguish when some accounts were written, and to what sources they had access, from the time that they appeared in print. For example, the report that Alastair Denniston wrote, The Government Code and Cypher School Between the Wars, was written from his home in 1944, but did not see the semi-public light of day until his son arranged to have it published in the first issue of the Journal of Intelligence and National Security in 1986 (see https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02684528608431841?journalCode=fint20) . About a decade later, it was released by The National Archives as HW 3/32.

Polish Rumours

For a concise and useful account of the relationship between Bletchley Park and the Poles, the essay Enigma, the French, the Poles and the British, 1931-1940 by Jean Stengers, found in the 1984 compilation The Missing Dimension, edited by Christopher Andrew and David Dilks, serves relatively well. It has a very rich set of Notes that lays out a number of primary and secondary sources that explain where much of the mythology of Enigma-decryption comes from. Yet the piece is strangely inadequate in exploring the early communications between the French and the British in 1931, and also elides over the exchange between Dillwyn Knox and Marian Rejewski in July 1939 which showed up Bletchley Park’s failings in pursuing the project, but then allowed the British endeavour to assume the leading role in further decryption.

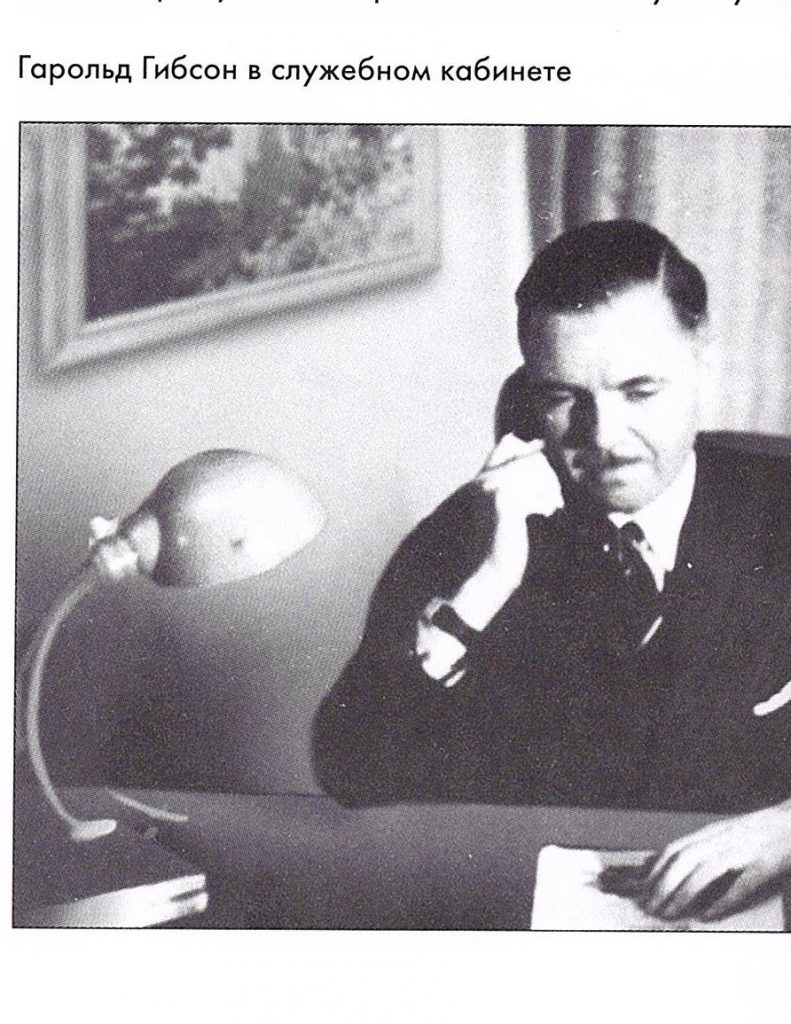

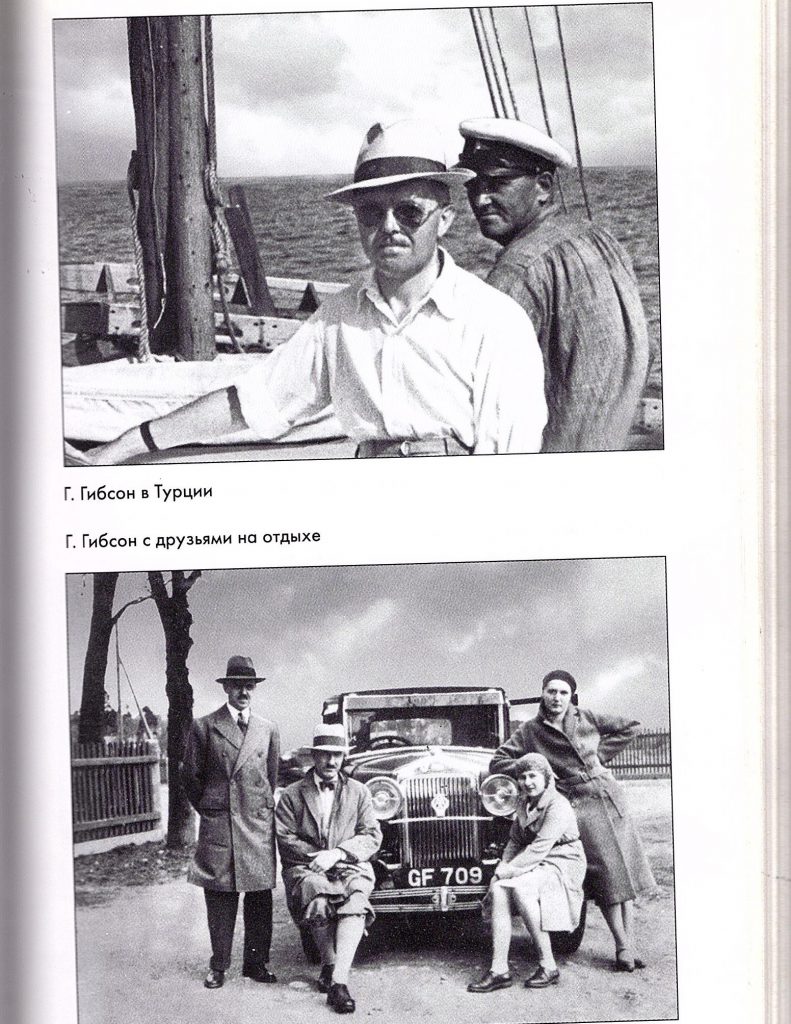

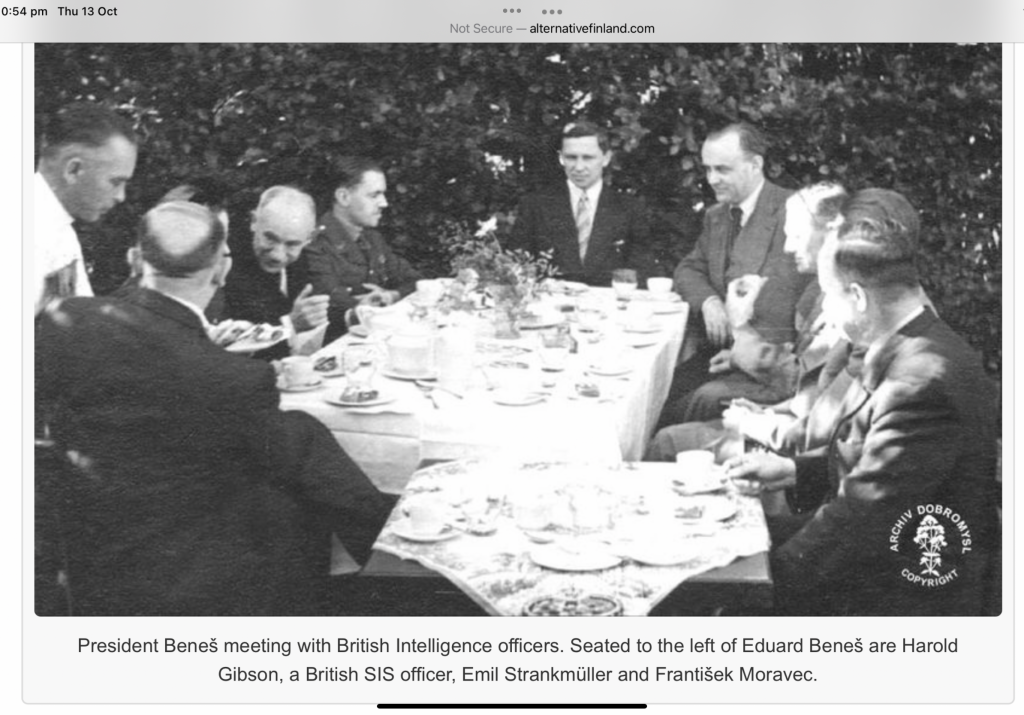

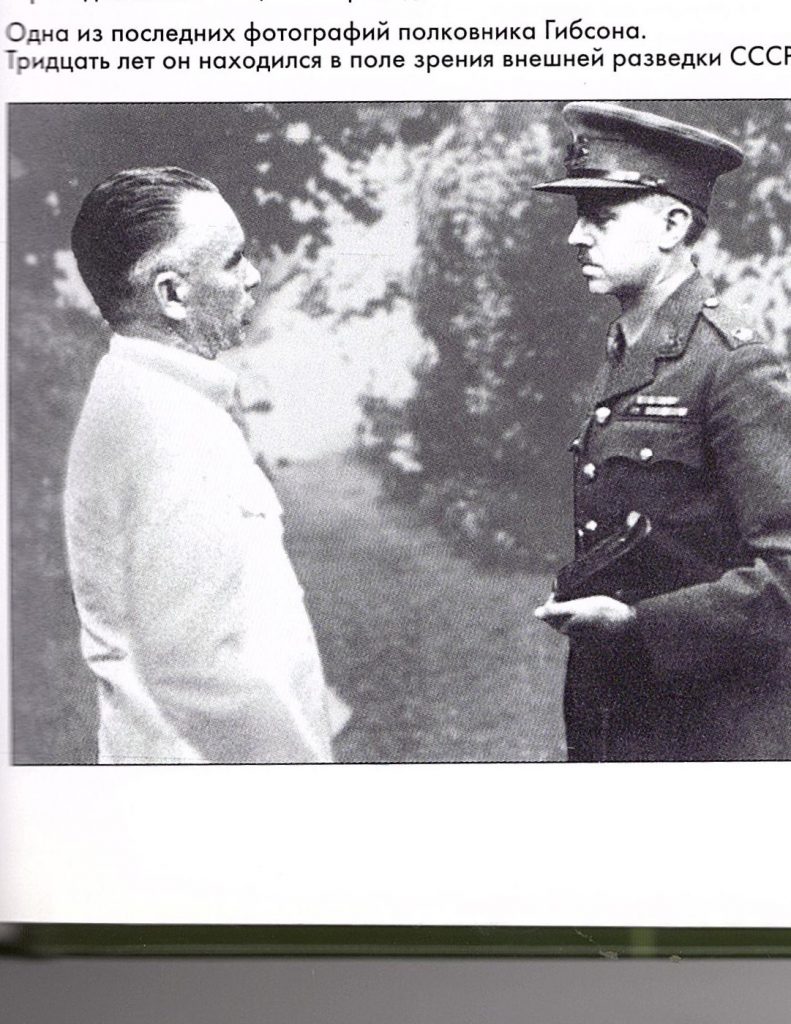

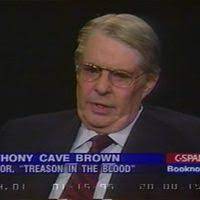

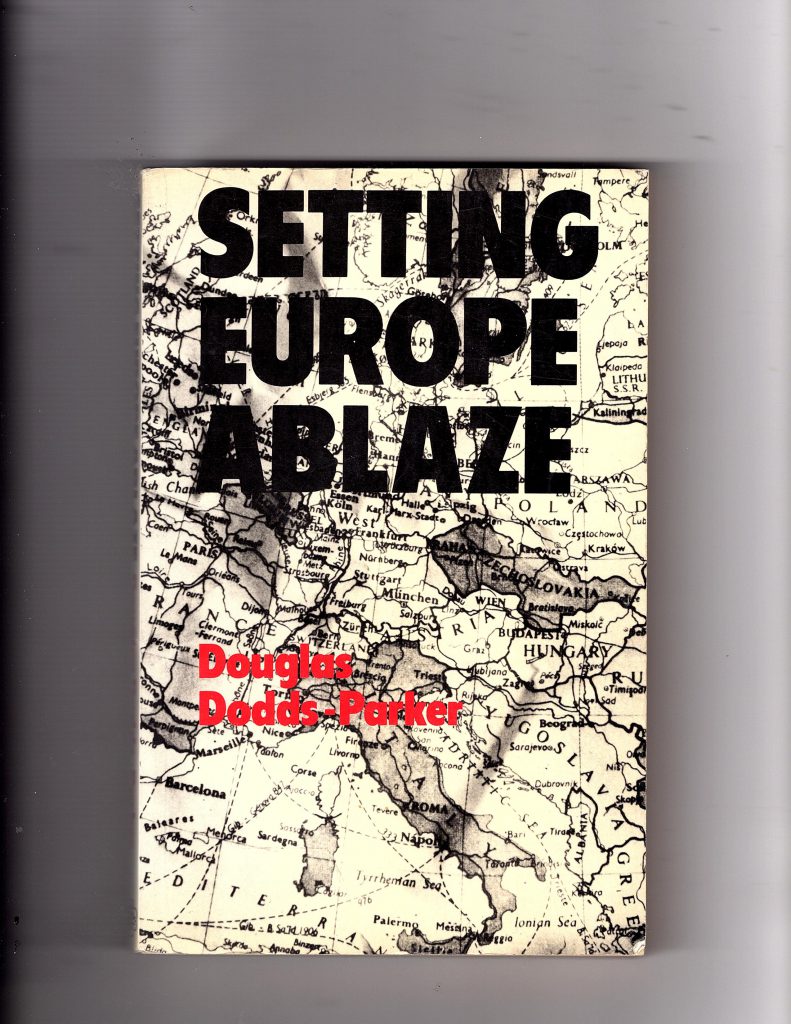

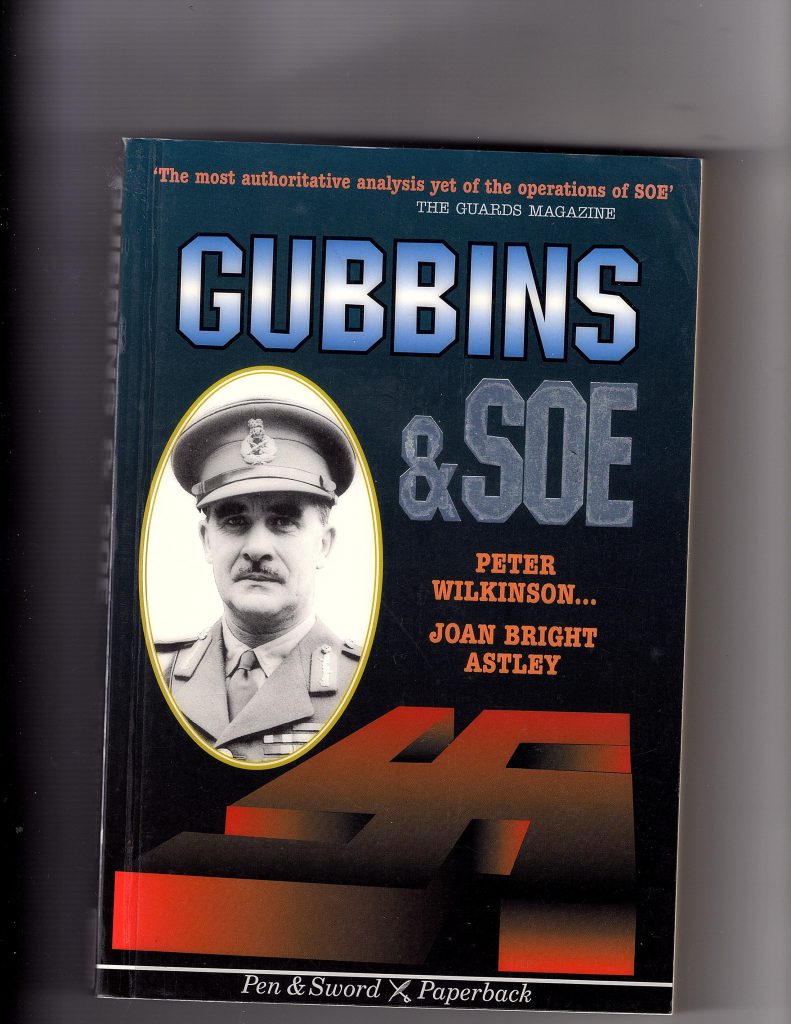

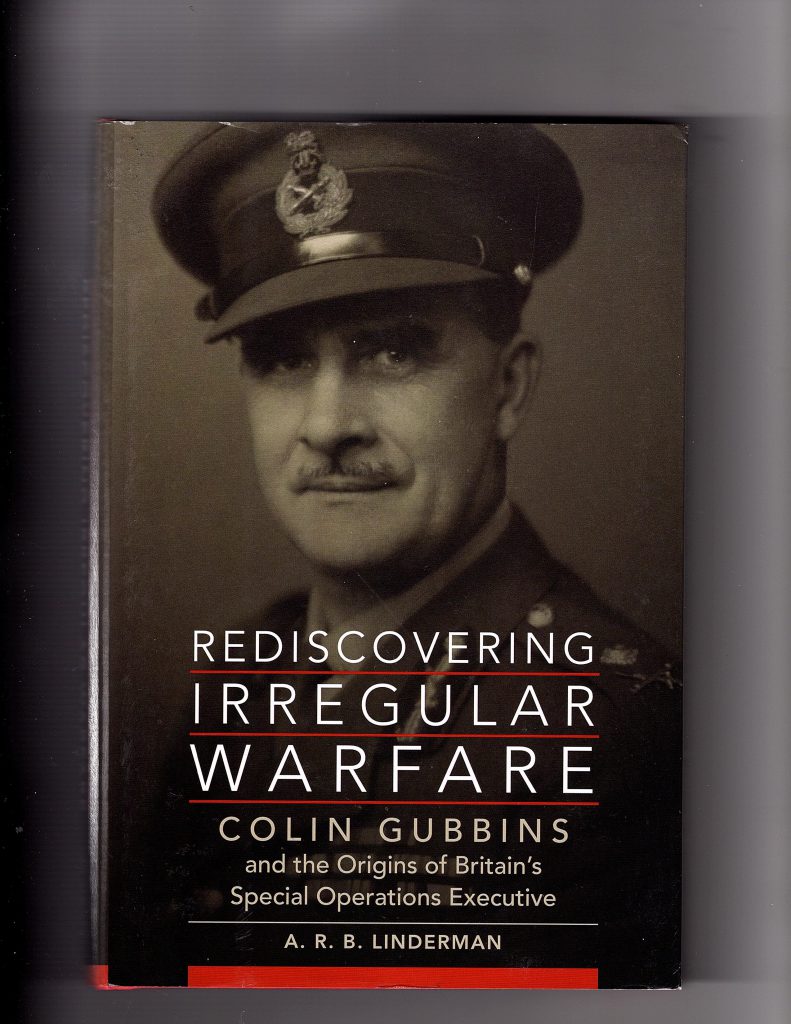

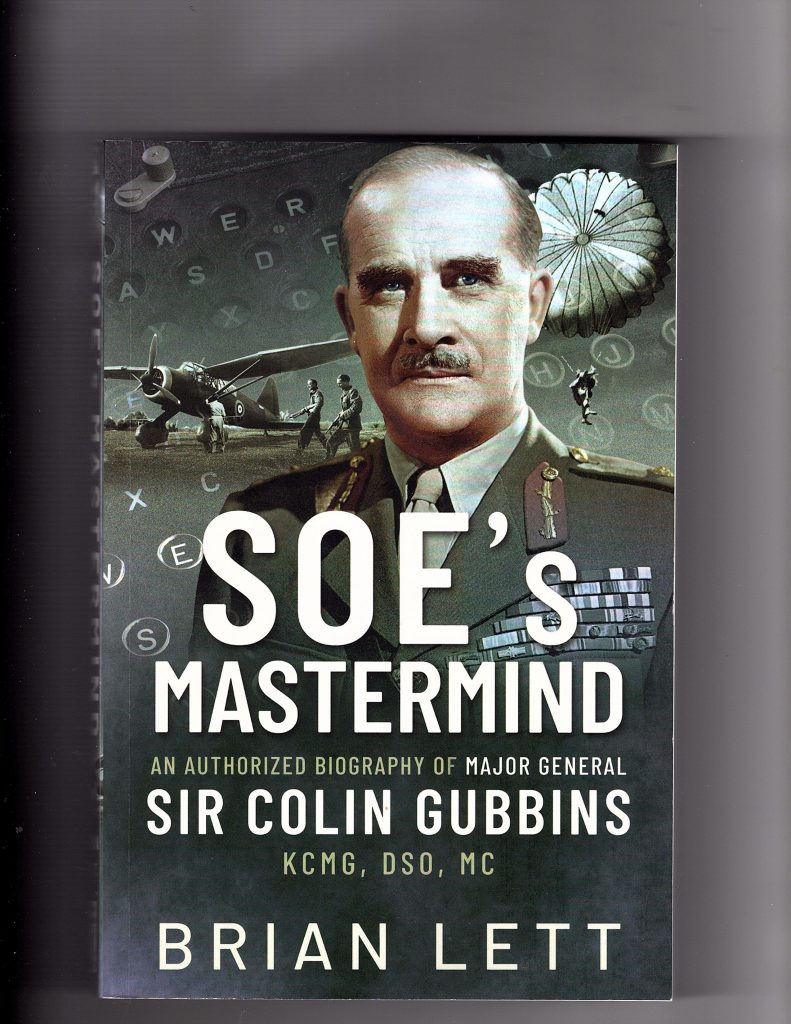

When Winterbotham published his book in 1974, it contained some recognition of a Polish contribution. Yet this was based on a rumour that must have been encouraged within GC&CS, while being utterly without foundation. The French writer Colonel Gardet, in La Guerre Secrete [see above], had claimed that a Polish mechanic working on the Enigma had been spirited out of Germany and had reconstructed a replica in Paris – a story that Winterbotham picked up with enthusiasm. It was later embellished by that careless encyclopaedic author Anthony Cave-Brown. And it was Cave-Brown who introduced the imaginary character, Lewinsky. He also implicated ‘Gibby’ Gibson, who reputedly spirited Lewinsky and his wife out of Poland, as well as the SOE officer Colin Gubbins, reported as taking Enigma secrets with him to Bucharest in September 1939. Both these preposterous anecdotes have found eager champions on the Web.

Yet these tales took time to die, and the claims about a spy in the heart of Germany’s cypher department (the truth of the matter) were initially distrusted. In Ultra Goes to War (1974), Ronald Lewin, perhaps overestimating the confidences told him by Colonel Tadeusz Lisicki (who had worked on the Enigma team, and took up residence in England after the war) echoed the claim that the Poles had, in 1932, ‘borrowed’ a military Enigma machine for a weekend. Lewin had read Bertrand’s account, but considered it ‘overblown’. He was very sceptical of the story that a Polish worker had smuggled Enigma parts over the border, but considered the assertion that an officer in the Chiffrierstelle had made overtures to the French in 1932 [sic: the occurrence of ‘1932’ instead of ‘1931’ is a common error in the literature, originating from Bertrand] only slightly more probable.

In fact, it was a review by David Kahn of Winterbotham’s book in the New York Times (on December 29, 1974) that brought the name of the spy, Hans-Thilo Schmidt, to the public eye. (see https://www.nytimes.com/1974/12/29/the-ultra-secret.html?searchResultPosition=2). In his later publication, How I Discovered World War II’s Greatest Spy & Other Stories of Intelligence and Code (2015), Kahn described how he had tracked down Schmidt’s name, and then confronted Bertrand with his discovery. Bertrand had wanted to keep his spy’s identity secret, and was outraged at Kahn’s disclosure. Yet, even at this late date (2015), Kahn misrepresented what actually happened, and failed to explain the true story about the Poles’ success – as I shall outline below.

And the muddle continued. In Most Secret War (1978), R. V. Jones declared that the Poles ‘had stolen the wheels’ of an Enigma machine, and the following year, a rather strange account by F. H. Hinsley appeared in the first volume of British Intelligence in World War II. Hinsley attempted to bring order to Gardet’s garbled story, and Bertrand’s subsequent controversial response, by openly describing the contribution of Schmidt, incidentally identified by his French cryptonym ‘Asché’, which appears to represent nothing more than the French letters ‘HE’. At the same time, however, Hinsley introduced his own measure of confusion. (He had not been a cryptanalyst.) Perhaps out of a desire to undermine the claims of the Poles, he reported that a 1974 memorandum by Colonel Stefan Mayer, head of Polish intelligence, made no mention of Asché’s papers and explicitly cast doubt that espionage had played any part in the project, as if it had been pure Polish ingenuity that had achieved the results. Moreover Hinsley contributed to the mythology by adding that ‘from 1934, greatly helped by a Pole who was working in an Enigma factory in Germany, they [the Poles] began to make their own Enigma machines’.

Yet Hinsley stated that he had discovered evidence of the French approach in the archives, although he circumscribed Bertrand’s account by characterizing what the Frenchman wrote as merely ‘claims’. (It appeared that he had, at least, studied Bertrand’s book.) Hinsley had also been prompted by a letter to the Sunday Times in June 1976 by Gustave Paillole [see below] that contested Winterbotham’s version of the events. Hinsley wrote (without identifying the archival documents):

GC and CS records are far from perfect for the pre-war years. But they confirm that the French provided GC and CS (they say as early as 1931) with two photographed documents giving directions for setting and using the Enigma machine Mark 1 which the Germans introduced in 1930. They also indicate that GC and CS showed no great interest in collaborating, for they add that in 1936, when a version of the Enigma began to be used in Spain, GC and CS asked the French if they had acquired any information since 1931; and GC & CS’s attitude is perhaps explained by the fact that as late as April 1939 the ministerial committee which authorized the fullest exchange of intelligence with France still excluded cryptanalysis.

This passage is important, since it strongly suggests that senior GC&CS members were aware of the French donation of 1931, and in 1936 rightly tried to resuscitate the exchanges of that time to determine whether any fresh information had come to light – a behaviour that strikes me as absolutely correct. Nevertheless, the official historian should have displayed a little more enterprise in his analysis. The head of GC&CS himself had apparently forgotten about the 1931 approach. When Denniston wrote his memoir in December 1944, all he stated about the French/Polish contribution was (of an undated event some time in 1938 or 1939): “An ever closer liaison with the French, and through them with the Poles, stimulated the attack.” Joel Greenberg cited a statement made by Denniston in 1948:

From 1937 onwards it was obviously desirable that our naval, military and air intelligence should get in close touch with their French colleagues for military and political reasons. The Admiral [Sinclair] had always wished for a close liaison between G. C. & C. S. and SIS but I have always thought that Dunderdale, then in Paris, was the man who brought Bertrand into the English organisations. Menzies, it is true, had a close relationship with Rivet under whom Bertrand worked but I think it was Dunderdale who, entirely ignorant of the method of cryptographers, urged the liaison on a technical level.

This appears, to me, to be a very naive observation by Denniston. It contradicts what Bertrand asserted about direct relationships with GC&CS and overlooks the 1936 overtures to the French, noted by Hinsley. By highlighting the lack of expertise in the matter held by the chief officer in MI6’s Paris station at the time, his statement might help to explain the embarrassments of 1931. At the same time, the comments of both Hinsley and Denniston suggest that the edicts of the ‘ministerial committee’ that prohibited discussion of cryptanalytical matters with the French could perhaps be defied.

Frank Birch, a history don who re-joined GC&CS in 1939 as head of the German Naval Section (he had worked in Room 40, which had been a Sigint Centre for the Royal Navy, between 1917 and 1919), and later became GCHQ’s historian, also covered that period superficially. When he wrote his internal history of British Sigint (he died in 1956 before completing it), he was similarly laconical about the pre-war co-operation, writing: “In the summer of that year [1939], as a result of staff talks with the French and the Poles, the head of GC&CS and Dillwyn (Dilly) Knox, a pioneer of Enigma research, visited Warsaw. There they learned of some successful solution of some earlier German traffic and the construction of an electrical scanning machine known as ‘la bombe’.” Just like that: staffs decided to converse. It was a very superficial account.

Yet there was at this stage evidence of a desire to conceal the fact that the British had been approached by Bertrand in 1931. Józef Garliński had published his account, Intercept, in 1979, and acknowledged the help he had received from Colonel Lisicki. (Garliński had served in Polish Intelligence, and was an Auschwitz survivor who did not come to England until after the war: he is best known for his memoir, Fighting Auschwitz.) He explicitly described the approach by Schmidt to the French in 1931, but omitted any reference to Bertrand’s first turning to the British. As he wrote about Bertrand’s reactions after receiving the first documents:

Captain Bertrand’s thoughts immediately turned towards Poland. He knew that Polish Intelligence had for some years past been trying to break the Germans’ secret. The Poles had been co-operating and exchanging information with him and now he could present them with a discovery of incalculable value.

This grandstanding account directly contradicts what (for example) Dermot Turing later wrote – that Bertrand turned to the Poles almost in despair after the British and Czechs had shown no interest. Moreover, there was no discussion of sordid financial negotiations, apart from the statement that Schmidt ‘had been given a substantial advance payment’. The impression given is that the French were quite happy to pay Schmidt, but passed on his secrets to the Poles for free. The author never suggests that the French might have turned to perfidious Albion first. Yet Garliński, in his Acknowledgments, singled out Harry Golombek and Ruth Thompson from Bletchley Park, and listed several other veterans who had helped him, including Mavis Batey, Anthony Brooks, Peter Calvocoressi, and Frederick Winterbotham He also paid thanks to a few British subjects close to the participants, a group that included Robin Denniston, Penelope Fitzgerald and Ronald Lewin. Did none of them attempt to put him right about the British Connection, or did they simply not know about it? Were they not aware of the archival material that Hinsley exploited in his publication of the very same year? One would expect these people to meet and talk, and at least be aware what was being written elsewhere. Significantly, perhaps, Garliński had not interviewed Hinsley or Wilfred Dunderdale.

Gordon Welchman also admitted his confusion when his Hut Six Story was published in 1982, not knowing how much to trust the various accounts of the Poles’ access to Enigma secrets. Apart from his exposure to Stengers, Hinsley, Lewin, and even William Stevenson’s highly dubious A Man Named Intrepid, Welchman had started to pick up some of the information disclosed in non-English media. He was aware of the activities of Schmidt, and described how the latter had passed documents to Bertrand in December 1932 [sic]. Notably, however, he referred solely to the fact that, since French Intelligence was not interested, Bertrand had passed the material to the Poles. There was no mention of any approach to the British at that time.

After publication (and the furore that erupted with American authorities about security breaches), Welchman realized that he needed to make changes to his account. As his biographer, Joel Greenberg, wrote: “He had learned some of the details of the pre-war work by the Poles on the Enigma machine too late to include them in his book.” He was also engaged in some controversy with the Poles themselves. Kozaczuk had diminished the contribution of the British in his 1979 work, Enigma, and in the 1984 English version had explicitly criticized The Hut Six Story. At the same time, Welchman had come to realize that Hinsley’s official history was deeply flawed: Hinsley had not been at Bletchley Park in the early days, and had obviously been fed some incorrect information. Welchman judged that Hinsley had been unduly influenced by the sometimes intemperate Birch.

Welchman gained some redemption when Lisicki came to his rescue, confirming the original contributions that Welchman and his colleagues had made, and eventually even Kozaczuk had to back down. The outcome was that a corrective article (From Polish Bomba to British Bombe: the Birth of ULTRA) was published in the first issue of Intelligence and National Security in 1986 – and eventually appeared in the revised edition of Welchman’s book. (Denniston’s son was manœuvering behind the scenes, as his father’s wartime memoir also appeared in that first issue of the Journal.) The issue at hand was, however, the contribution from British innovation and technology in 1940 – not the question of access to purloined material in the early 1930s.

Similarly, Christopher Andrew, in his 1986 work Her Majesty’s Secret Service (titled simply Secret Service when published the previous year in the UK), and subtitled The Making of the British Intelligence Community, left out much of the story. He obviously credited Stengers, who had contributed to the anthology that he, Andrew, edited with David Dilks [see above], and he also referred to Garliński’s Intercept (re-titled The Enigma War when published in the USA). Andrew echoed Garliński’s claim that Rejewski had gained vital documents from Schmidt back in the winter of 1931. Yet Andrew gave no indication that the British had been invited to the party at that time: he merely observed that, since the French cryptographic service had shown no interest in the documentation, Bertrand passed it on to the Poles. One might have imagined that the discovery of a spy within the Chiffrierstelle would have sparked some greater curiosity on the part of the chief magus of our intelligence historians, and that Andrew would have studied Hinsley’s opus, but it was not to be. And the story of Bertrand’s approach to the British was effectively buried.

Thus the decade approached its end without any confident and reliable account. Nigel West’s GCHQ (1986) shed no new light on the matter, while Winterbotham, in his follow-up book The Ultra Spy (1989), felt free to reinforce the fact that the French had been approached by a German spy in 1934 [sic], but that Bertrand had then turned to the Poles, echoing Andrew’s story that the British had been told nothing. It still seemed an inconvenient truth for the British authorities to acknowledge that GC&CS (or MI6) had treated with too much disdain an approach made to them in the early 1930s, and the institution’s main focus was to emphasize the wartime creativity of the boffins at Bletchley Park while diminishing the efforts of Rejewski, Zygalski and Różycki.

One final flourish occurred, however. In Volume 3, Part 2 of his history of British Intelligence in the Second World War, published in 1988, Hinsley (assisted by Thomas, Simkins and Ransom) issued, in Appendix 30, a revised version of the Appendix from Volume 1. (Tony Comer has informed me that this new Appendix was actually written by Joan Murray. I shall refer to the authorship as Hinsley/Murray hereafter.) She wrote as follows:

Records traced in the GC and CS archives since 1979 show that some errors were introduced in that Appendix from a secondary account, written in 1945, which relied on the memories of the participants when it was dealing with the initial breakthrough into the Enigma. Subsequent Polish and French publications show that other errors arose from a Mayer memorandum, written in 1974, which apart from various interviews recorded in British newspapers in the early 1970s was the only Polish source used in compiling the Appendix to Volume 1.

Oh, those pesky unreliable memoirs – and only a short time after the events! While the paragraph issued a corrective to Colonel Mayer’s deceptive account, Hinsley/Murray seemed ready to accept the evidence of two ‘important’ French publications that had appeared since Bertrand’s book of 1973, namely Paillole’s Notre Spion chez Hitler, and an article by Gilbert Bloch in Revue Historique des Armées, No. 4. December 1985. Hinsley/Murray went on to confirm that Bertrand ‘acquired several documents, which included two manuals giving operating and keying instructions for Enigma 1’, and added that, ‘as was previously indicated on the evidence of the GC and CS archives, copies of these documents were given to the Poles and the British at the end of 1931.’ Yet this was a very ambiguous statement: by ‘these documents’, did Hinsley/Murray imply simply the ‘two manuals’, as he had indicated in the earlier Volume of his history, or was he referring to the ‘several documents’? The phrasing of the quoted clause clearly suggests that the Poles and the British were supplied with the same material at the same time, but his own text contradicts that thesis.

The puzzle remained. Exactly what had Bertrand passed to the British in 1931, and who saw the material?

GC&CS Indifference?

In 1985, Paul Paillole, a wartime officer in France’s secret service, published Notre Spion chez Hitler, which, being written in French, did not gain the immediate attention it deserved. (It was translated, and published in English – but not until 2016 – under the inaccurate title The Spy in Hitler’s Inner Circle.) Paillole’s role in counterespionage in Vichy France is very ambivalent, and he tried to show, after the war, a loyalty to the Allied cause that was not justified. Nevertheless, his account of the approach by Schmidt to the French, and the subsequent negotiations with the Poles, has been generally accepted as being reliable.

Paillole had joined the Deuxième Bureau of the French Intelligence Department on December 1, 1935, and, hence, was not around at the time of the initial assignments made between Schmidt and Rodolphe Lemoine (‘Rex’), a shady character of German birth originally named Rudolf Stallman, who was detailed to respond to Schmidt’s overtures of July, 1931. Paillole first learned of the spy in the Chiffrierstelle from Gustave Bertrand, who had joined the department in November 1933 as head of Section D, responsible for encryption research. His book is many ways irritating: it has a loose and melodramatic style, and lacks an index, but it contains a useful set of Notes, and boasts an authoritative Preface by someone identified solely as Frédéric Guelton (apparently a French military historian of some repute) that reinforces the accuracy of Paillole’s story. It also includes references to KGB archival material, and the involvement of two fascinating and important NKVD spy handlers, Dmitry Bystrolyotov and Ignace Reiss, which could be a whole new subject for investigation another day.

Typical of Paillole’s rather hectic approach is his account of how Bertrand told him the story about Schmidt. We are supposed to accept that, one day early in 1936, Bertrand pulled Paillole into his office and started to deliver a long description of the negotiations, a discourse that continued over lunch. Moreover, an immediate conflict appears: while Guelton had indicated that Bertrand ‘arrived on the scene’ in November 1933, Bertrand claimed that he had established Section D in 1930. Notwithstanding such chronological slip-ups, Bertrand told a captivating story.

Somehow, Paillole was able to reproduce the whole long monologue without taking any notes, including the details of the material that Schmidt had handed over in late 1931, namely seven critical items mainly concerning the Enigma, including ‘a numbered encryption manual for the Enigma I machine (Schlűsselanleitung. H. Do. G. 14, L. Do. G. 14 H. E. M. Do. G. 168)’. Since this information must have come from a written report, it is hard to understand why he felt he had to dissemble. (This represents an example of an ‘Authentic’ release of intelligence, but not a ‘Genuine’ one.) For the purposes of this investigation (the exposure to the British), however, the exact form of Bertrand’s report is less significant. Early on, Bertrand offered the following insight: “I’ve used the good relationships our Bureau has with allied bureaus in London, Prague and Warsaw to comparing our level of knowledge with theirs and work to share our intelligence efforts. The British know less than us. They show a faint interest in the research in Germany and cryptography. The only ones who are passionate about these problems are the Poles.”

Now, one might question the timing of this activity: ‘I’ve used’, instead of ‘I used’ suggests a more recent event, but that may be an error of translation. Yet a later section expresses the idea more specifically. After presenting the documentation to Colonel Bassières, the head of the Intelligence Department, and receiving a depressing rejection because of the complexity of the challenge, and the lack of resources to undertake the work, Bertrand described how he approached his British allies:

In Paris, I entrusted the photographs of the two encryption and usage manuals for the Enigma machine to the representative of the Secret Intelligence Service, Commander Wilfred Dunderdale. I begged him to inform his superiors of the opportunities that were available to us. I proposed to go to London to discuss with British specialists the common direction we should take for our research.

If any approach were to succeed, I had secretly hoped that it would encourage the interests of French decoding services. Naturally enthusiastic, Dunderdale, convinced of the importance of the documents I possessed, immediately went to England. It was November 23, 1931. On the 26th, he was back. From the look of dismay on his face, I knew that he had been hardly any more successful than I had been in France.

Thus Bertrand turned to the Poles.

Certain aspects of this anecdote do not ring true. This was of course the same Dunderdale who, in the words of Denniston, ‘was entirely ignorant of the method of cryptographers’. Yet it is he who immediately understands the importance of the documents, while his superiors in London reject them. (My first thought was that Denniston deliberately downplayed the insightfulness of Dunderdale in an attempt to extinguish any trace of the 1931 exchanges.) Moreover, if Bertrand enjoyed such a good relationship with the ‘allied bureau’ in London (GC&CS, presumably, not SIS/MI6), and knew enough to be able to state that his British counterparts were less well informed than the French, why did he not indeed visit London to meet Denniston himself, instead of relying on an intermediary with less experience? (Tiltman visited Paris, but not until 1932, to discuss Soviet naval codes, and struck up a good relationship with Bertrand, which aided in Tiltman’s inquiries with the French over Enigma in September 1938.) Can Bertrand be relied upon for the intelligence that Dunderdale actually went to London himself to make the case?

Yet the account presented a tantalizing avenue for investigation. Was there any record of that British response to be found in internal histories of British Sigint, or in memoirs of those involved?

In Seizing the Enigma (1991), David Kahn, the celebrated author of Codebreakers, tried to dig a little further, although he was largely dependent upon the accounts of Bertrand and Paillole. At least he brought the French sources to a broad English-speaking audience, as well as the voice of authority. One significant aspect caught my eye. When Bertrand brought his photocopies to Colonel Bassières of French Intelligence, he waited two weeks before returning to find out how he had progressed: it took that long for Bassières to digest the contents of the material, and to conclude that it would be very hard to make any progress without knowledge of the wiring of Enigma’s rotors and of the settings of the keys on any particular day. Yet only three days elapsed between Dunderdale’s receipt of the same material (in Paris, on November 23) and his report that the British likewise judged them to be of little use.

Is that not astonishing? Surely, MI6 – and GC&CS, if it were contacted – would not have made any judgment based on a cabled summary from Dunderdale? They would have demanded to be able to inspect the source documents carefully. Bertrand implied that Dunderdale took them with him to England. But for him to set up meetings in London, travel there, have the documents assessed, and so swiftly rejected, before returning to Paris, seems highly improbable. He was informed on a Monday, and was back on the Thursday to deliver his verdict. Did the cryptographically challenged Dunderdale really follow through? Had he actually taken the samples with him to London?

The 1988 analysis from Hinsley/Murray appears to confirm that Dunderdale did manage to get his material through to GC&CS in London, and that, as Bertrand reported, the two manuals giving operating and keying instructions were received by the appropriate personnel. And Hinsley/Murray confirmed the lukewarm response:

On the British lack of interest in the documents, GC and CS’s archives add nothing except that it did not think them sufficiently valuable to justify helping Bertrand to meet the costs. It would seem that its initial study of the documents was fairly perfunctory [indeed!] since it was not until 1936 that it considered undertaking a theoretical study of the Enigma indicator system with a view to discovering whether the machine might be reconstituted from the indicators if enough messages were available.

The suggestion that GC&CS personnel did truly get an opportunity to inspect the two documents in 1931 is vaguely reinforced by an Appendix to Nigel de Grey’s internal history of GC&CS, although his text is irritatingly imprecise, with a lack of proper dating of events, too much use of the passive voice, and actors (such as ‘the British’) remaining unidentified. He acknowledges that GC&CS had access to two documents from Bertrand, but his evidence of this claim is a memorandum from September 1938.

Silence from the British camp over the incident appears therefore to have derived from embarrassment, not because the transfer never happened. Yet the Hinsley/Murray testimony introduces a new aspect – that of money. It suggests that Bertrand may have been requesting payment, or perhaps a commitment of investment, for the treasure he was prepared to hand over. At the time of that revisionist account, all the senior figures who could have been involved were dead: Denniston (1961), Knox (1943), Travis (who might have used any misdemeanor to disparage Denniston, 1956), Tiltman (1982), and Menzies (1968). No one was around to deny or confirm.

On the other hand, Bertrand had not been entirely straight with the British. His account never indicates that he asked the British for funds, but that he was offering a sample out of his desire for cooperation. If he turned to the British first, why did he offer them only two items, when he handed over the complete portfolio to the Poles a week later? It is true that the remaining documents might not have been so useful, but why did he make that call? As it happened, the Poles were overjoyed to receive the dossier on December 8, although they eventually would come to the same conclusion that they were stymied without understanding the inner workings of the machine, and some daily keys. Moreover, no account that I have read suggests that Bertrand asked the Poles for payment. Yet the French Security Service needed cash to pay Schmidt, and it is unlikely that, having been turned down by the British, they would agree to hand over the jewels to the Poles for free. They needed to sustain payments for Schmidt, but were not making use of any of the material themselves, and were not even being told by the Poles what progress they were making. It does not make sense.

Nevertheless, over the next few years, Bertrand continued to supply the Poles with useful information from Schmidt, and Rejewski’s superb mathematical analysis enabled the Poles to make startling progress on decrypting Enigma messages. The British heard nothing of this: Hinsley/Murray report that a memorandum as late as 1938 indicates that they had not received any fresh information since 1931. They also wrote:

In all probability the fact that GC and CS had shown little interest in the documents received from Bertrand in 1931 is partly explained by the small quantity of its Enigma intercepts; until well into the 1930s traffic in Central Europe, transmitted on medium frequencies on low power, was difficult to intercept in the United Kingdom. It is noteworthy that when GC and CS made a follow-up approach to Bertrand in 1936 the whole outcome was an agreement to exchange intercepts for a period up to September 1938.

This strikes me as a bit feeble. (Since when was Germany in Central Europe? And was interception really a problem? Maybe. The British were picking up Comintern messages in London at this time, but the Poles would have been closer to the Germans’ weaker signals.) Yet surely GC & CS should have been more imaginative. They had acquired a commercial Enigma machine: they could see the emerging German threat by the mid-thirties, and they were intercepting Enigma-based messages from Spain during the Civil War. (Hinsley/Murray imply that no progress had been made on this traffic, but de Grey, in his internal history, reported that Knox had broken it on April 24, 1937.) It is also true that the Poles were better motivated to tackle the problem, because of their proximity to Germany and the threats to their territory, but Denniston and his team were slow to respond to the emergent German threat, no doubt echoing the national policy against re-armament at the time, but also failing to assume a more energetic and imaginative posture.

After all, if the War Office had started increasing the interception of German Navy signals during the Spanish Civil War, it surely would have expected an appropriate response from GC&CS, whether that involved shifting resources away from, say, Soviet traffic, or adding more cryptographic personnel. GC&CS did respond, in a way, of course, since Knox set about trying to break the Naval codes. He had had much success in breaking the messages used by the Italians and the Spanish Nationalists, but, soon after he switched to German Naval Enigma, the navy introduced complex new indicators. He thus started work on army and air force traffic under Tiltman. GC&CS might have showed a little more imagination, but, as Hinsley/Murray recorded, they were constrained (or discouraged?) from discussing decryption matters with the French. Despite that prohibition, Tiltman was authorized to go to Paris to discuss cryptanalysis with Bertrand in 1932. Was he breaking the rules?

I looked for further confirmation of the nature of the material handed over, and who saw it. That careful historian Stephen Budiansky covers the events in his 2000 book Battle of Wits. He lists an impressive set of primary sources, including the HW series at the National Archives, but admits that he was very reliant on Ralph Erskine ‘the pre-eminent historian of Naval Enigma, who probably feels he wrote this book himself’ for supplying him with answers to scores of emailed questions. He writes, of Bertrand’s transfer of material to the British: “Copies of the documents were sent to GC&CS, which dutifully studied them and dutifully filed them away on the shelf, concluding that they were of no help in overcoming the Enigma’s defenses.” Yet his source for that is the Volume 3 Appendix, and his comments about defenses contradicts what Hinsley/Murray wrote about Enigma not being considered a serious threat at that time. This is disappointing, and strikes me as intellectually lazy.

And then some startling new insights appeared in Mavis Batey’s profile of Knox, Dilly, which appeared in 2009. Batey had joined GC&CS in 1940, and had worked for Knox until his death in February 1943. She introduced some facts that bolster the hints of the mercenary character of Bertrand’s offer, but at the same time she also indulged in some speculation. Batey suggested that Bertrand’s main liaison was Dunderdale (this minimizing his claims about close contacts in London), and that, when he offered Dunderdale the documents, Bertrand demanded to be paid for them. Yet her text is ambiguous: she writes that Bertrand ‘wanted a considerable sum for any more [sic] of Asché’s secrets’, thus implying that he had already received some for free. Moreover, when Dunderdale contacted London, he received a negative response, for reasons of cost.

The request was turned down flat. It was a political matter of funding priorities and it seems that Denniston, Foss, Tiltman and Dilly [Knox] were not consulted. Dunderdale did have the original batch of documents for three days and in all probability photographed them, allowing Dilly to analyse them later, but the ban on paying any money for them cut the British off from the rest of Asché’s valuable secrets.

This is an astonishing suggestion – that no employee of GC&CS, and probably no MI6 officer, either, even saw the documents at the time, but that MI6 (Sinclair?) simply sent a message of rejection by cable based on a message from Dunderdale. If that were true, it might explain the singular lack or recollection of the events on the part of Denniston and others. (One has therefore to question the Hinsley/Murray interpretation of the archive.) But the text is also very disappointing. Batey does not identify the ‘original batch’: were they the set of seven, or just the two on operating instructions and key settings? Did Dunderdale actually photocopy them, or was that not necessary, given Bertrand’s indication that he offered those two – which were themselves photographs, of course – for free? Did Knox really analyze them later? (The evidence of others suggests that this is pure speculation.) And, if the documents that Asché provided in the following years were truly ‘valuable’, to what extent was the British decryption effort cruelly delayed? (The Poles would later admit that the stream of documents after 1931 was critical to their success.) Did the quartet complain vigorously when they were able to inspect Dunderdale’s copies, and did they inquire about the source, and whether there was more? Unfortunately, Batey leaves it all very vague. What she does confirm, however, is that, in 1938, Sinclair ‘anxious to increase co-operation with France, authorized Denniston to invite Bertrand over for a council of war’.

One might imagine that, with the passage of time, greater clarity would evolve. Yet that is not the case with Dermot Turing in his 2018 book X, Y & Z, the mission of which is to set the record straight on the Polish achievements. While his coverage of the Polish contribution is very comprehensive, Turing shows a muddled sequence of events in the early 1930s, and his analysis is not helped by a rather arch, journalistic style. He refers to ‘Bertrand’s sniffy friends across the Channel’, and informs his readers that ‘the British had sniffed around the Enigma machine before’. Nevertheless, he is ready to describe John Tiltman as ‘the greatest cryptanalyst’ they had, and explains that Tiltman had visited Paris around this time, as I noted earlier.

In 1932, he had been in Paris, asking the French to help with a perennial problem – that Britain’s precious Navy might be under threat from the Soviets. Tiltman came with an incomplete set of materials on Soviet naval codes, which he hoped the French might be able to complement. Alas, the answer was no, but the potential for cooperation had been established.

Unfortunately, Turing then moves from this event to declare that, after an Enigma machine had been inspected back in 1925 by Mr Foss, who made a detailed technical report that was put on file, the link established by Tiltman facilitated an initiative by the British to discuss the Enigma with the French. He writes:

But now Captain Tiltman had made the diplomatic link between GC&CS and Captain Bertrand’s Section D, perhaps the boffinry [sic] might be extracted from its file and put to good use. The question was duly put, via the proper channels, which is to say MI6’s liaison officer in Paris.

Bertrand’s bathroom photographs were carefully evaluated at MI6. The photography was good, but MI6 independently came to the same conclusion as the Section de Chiffre. The documents were, unfortunately, useless.

Turing, perhaps not unexpectedly, provides no references for this mess. Tiltman’s initial visit occurred after Bertrand made his 1931 approach. Turing provides no rationale for the British suddenly making timely overtures to the French. (He was probably confusing the 1938 overtures with the events of 1931.) He has MI6, not GC&CS, making the evaluation, which is superficially absurd, and may echo the reality that Batey described, but undermines his disparaging comments about the sniffy boffins at GC&CS. Yet his conclusion is the same: ‘the British were a dead end’.

And what of Gustave Bertrand? He was a very controversial figure: he was arrested by the Germans in 1944, but managed to escape to Britain, claiming that he had agreed to work for the Nazis – though what he was going to reveal, how they would control him, and how he would communicate with them is never stated. Paillole himself investigated the affair, and determined that Bertrand was innocent of any treachery. Dermot Turing also gives him the all-clear in X, Y & Z, but it would not be out of character for Bertrand to have withheld some information from the British in 1931 when he wanted to keep much of the glory to himself and the French service. His petulant behaviour during, and immediately after, the war, when he showed his resentment at the achievements of the British, was noted and criticized by the Poles. He was not going to give anything away in a spirit of co-operation, and he left for posterity an inadequate account of the financial aspects of the deal. He may also have handed the documents over to the Czechs, as he hinted at in his book, and as David Kahn claimed he told him. If so, they would have been forwarded immediately to the Russians.

Whatever Bertrand’s motivations and actions, however, I have to conclude that GC&CS did not show enough energy and imagination in the second half of the 1930s decade. It moved too sluggishly. The fact that GC&CS historians felt awkward in admitting that it would not have made sense to pursue the matter in 1931, but affirmed that the service should have revisited it in 1936, suggests to me a widespread embarrassment over the advantage that they unwittingly conceded to the Poles. While we are left with the conflicting testimonies from Denniston and Hinsley/Murray, it seems clear that neither Sinclair nor Denniston was prepared to take a stand. Yet the vital conclusion remains that, if indeed MI6 had concealed Bertrand’s approach, and the accompanying documents, even from the chief of GC&CS, the responsibility for the lack of action must lie primarily with Sinclair.

The Aftermath

Especially in the world of intelligence, the evidence from memoirs and interviews is beset with disinformation, the exercise of old vendettas, and a desire for the witness to show him- or her-self in the best possible light. So it is with the Enigma story. The whole saga is beset with contradictory testimonies from participants who either wanted to exaggerate their achievements, or to conceal their mistakes. One has to continually ask of the participants and their various memories: What did they know? From whom were they taking orders? What were their motivations? What did they want to conceal? Is Mavis Batey implicitly less trustworthy than Frank Birch or Alastair Denniston? Thus the addressing of the two important questions: ‘To what extent did the hesitations of the early thirties impede the British attack on the Enigma?’, and ‘How was Denniston’s reputation affected by the leisurely build-up before the war?’ has to untangle a nest of possibly dubious assertions.

Of all the cryptanalysts who might have felt thwarted by any withholding of secret Enigma information, Dillwyn Knox would have been the pre-eminent. It was he who led all efforts to attack it in the 1930s, although the accounts of his success or failure are somewhat contradictory. According to Thomas Parris in The Ultra Americans, Knox had been on the point of retiring in 1936, wishing to return to teach at King’s College, Cambridge, but was persuaded to stay on to tackle the variant of Enigma used by the German Military, Italian Navy and Franco’s forces during the Spanish Civil War. (The claim about his retirement aspirations may be dubious, however. It cannot be verified.) Stengers wrote that Knox had applied himself to the task with vigour, and had ‘cracked’ the cipher. On the other hand, Milner-Barry stated that Knox had been defeated by ‘it’, but he was probably referring to Knox’s efforts in tackling the more advanced German naval version. Denniston’s son, Robin, wrote that a more intense project had started after the Spanish civil war, and that Knox worked on naval traffic, with some help from Foss, while Tiltman concentrated on German military uses, and Japanese traffic. He also mentioned that Knox had cracked the inferior version used by the Italian navy. Those were Batey’s ‘Enigmas’. And she strongly challenged the view that Knox would have been ‘defeated’ by anything.

Knox was by temperament a querulous and demanding character, and was outspoken in his criticisms of Denniston over organizational matters in 1940, which the chief sustained patiently. Thus, if he had believed that he had been let down by GC&CS over the acquisition of Enigma secrets, he surely would have articulated his annoyance. But all signs seem to point that he was unaware of any negotiations between the French and the British, or of the existence of a long-lived chain of communication from internal German sources to the Poles when he had the famous encounter with Rejewski at Pyry, outside Warsaw, in July 1939. After the initial fencing, when neither side was prepared to reveal exactly what progress it had made, Knox posed the vital question ‘Quel est le QWERTZU?’. By this, he wanted Rejewski to describe how the keyboard letters on the Enigma were linked to the alphabetically-named wheels (the ‘diagonal’). When Rejewski rejoined that the series was ABCDEFG . . ., Knox was flabbergasted. One of his assistants had suggested that to him, and he had rejected it without experimenting, believing that the Germans would not implement something so obvious.

The irony was that Rejewski had experienced that insight back in 1932, and had been helped by the supply of further keys and cribs from Schmidt since then. (According to Nigel de Grey, Rejewski later implied that the information on the diagonal came directly from Schmidt, and de Grey cites, in French, a statement from Rejewski that, even so, ‘they could have solved it themselves’. Most accounts indicate that Schmidt was never able to hand over details of the internal wiring of the machine.) Knox knew nothing of that. He was sceptical of the ability of the Poles to have made such breakthroughs unaided, but he never understood the magnitude of the advantage they had. Admittedly, in a report he compiled immediately on his return from Poland, he mentioned that Rejewski had referred to both ‘Verrat’ (treachery), and the purchase of details of the setting as contributing to the breakthrough, but Knox never explored this idea. Rejewski’s more mathematical approach was superior to Knox’s more linguistic-based analysis, it is true. But seven years in the wilderness! Welchman wrote in 1982 that Knox could have made similar strides and ‘arrived at a comparable theory’ if he had had access to the Asché documents, yet (as Tony Comer has pointed out to me) that judgment ignores the fact that no mathematical analysis was possible at GC&CS until Peter Twinn joined early in 1939.

Why did the services of the three countries – all potential sufferers from German aggression – not collaborate and share secrets earlier? It boils down to money, resources and lack of imagination on the part of the British, money, proprietorship of ownership, and skills with the French, and primarily security concerns with the Poles. Because of geography, and political revanchism, the Poles were the most threatened. They believed for a long while that they could handle Enigma on their own and, moreover, had to protect against the possibility that the Germans should learn what they were up to. In 1931, two years before Hitler came to power, they could not count on Great Britain as a resolute ally against the Germans. They therefore did not share their experiences until the pressures were too great.

An important principle remains. If Sinclair, in 1931, justifiably did not press for funds to pay for Schmidt’s offerings, a time would come when the German threat intensified (perhaps with the entry to the Rhineland in 1936, as I suggested in On Appeasement) to the point when he should have taken stock, recalled the missed opportunity of 1931, and followed up with Bertrand to try to revivify the relationship, and the sharing of Enigma intelligence. That might have involved a confrontation with the War Office, but, as I have shown, that Ministry was then starting to apply pressure off its own bat. Hinsley/Murray make the point that an anonymous person did in fact attempt such contact, but that the outcome was sterile, because of policy. The general silence of inside commentators over the decisions of the early 1930s suggest to me that they were not comfortable defending Sinclair’s initial inaction (which was, in the political climate of 1931, indeed explicable), or his lack of follow-up when conditions had sharply changed.

While Denniston can surely be cleared of any charges of concealing important intelligence from his lieutenants, the accusations made that he had been too pessimistic over the challenge of tackling Enigma have some justification. Denniston’s position was originally based on his opinion that radio silence would be imposed in the event of war (an idea derived from Sinclair), but also on a conviction that the demand on costs and resources would be too extravagant to consider a whole-hearted approach on decryption. Frank Birch became a strident critic of his bosses:

To all this, are added the ‘most pessimistic attitude’, ascribed to the head of GC&CS ‘as to the possible value of cryptography in another war’ and the fear expressed by the director of GC&CS [i.e. Sinclair] after the Munich crisis ‘that as soon as matters became serious, wireless silence is enforced, and that therefore this organisation of ours is useless for the purpose for which it was intended.

His disdain became very personal (to the extent that he even spelled his boss’s first name incorrectly as ‘Alistair’), and over the crisis of 1941, when Denniston resisted the introduction of wireless interception and analysis into his province, Birch resorted to undergraduate cliché to characterize Denniston’s approach: “Commander Denniston’s attitude was consistent with his endeavour to preserve GC&CS as a purely cryptanalytic bureau and, Canute-like, to halt the inevitable tide that threatened to turn it into a Sigint Centre.” Birch was no doubt thinking of Room 40, where Denniston, Birch and Travis had served.

Yet even Denniston’s initiative to change the intellectual climate at Bletchley Park came under attack. Some commentators, such as Kahn, Aldrich, and Ferris, have commended Denniston for starting the drive to recruit mathematicians, after the experience at Pyry. John Ferris even wrote, in Behind the Enigma, that Denniston had prepared his service for war better than any other leader of British intelligence, a view also anticipated by Nigel West:

For almost twenty years Denniston succeeded in running on a shoestring a new and highly secret government department. When his resources were increased on the eve of war, he began the expansion which made possible the achievements of Bletchley Park. [DNB] Many of his best cryptanalysts would not have taken kindly either to civil service hierarchies or to a Chief devoted to bureaucratic routine, Denniston’s personal experience of cryptography, informal manner, lack of pomposity and willingness to trust and deal get to his sometimes unorthodox subordinates smoothed many of the difficulties in creating a single unit from the rival remains of Room 40 and MI1b.

Maybe these positive assessments were based too much on what Denniston wrote himself. Again, Birch took vicarious credit for the execution of the policy. Ralph Erskine, in his Introduction to Birch’s History, wrote: “From about 1937 onwards, Birch played a major part in advising Alastair Denniston, the operational head of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), on choosing the academics, including Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman, who were to become the backbone of GC&CS’ wartime staff.”

The verdict on Denniston must be that he was a very honourable and patient man, a dedicated servant, and a very capable cryptographer, but one who excelled in managing a small team – as he again showed when he was moved to Berkeley Street. In an internal note, Tony Comer wrote:

His memorial is that he built the UK’s first unified cryptanalytic organisation and developed the values and standards which made it a world leader, an organisation which partners aspired to emulate; and that he personally worked tirelessly to ensure an Anglo-American cryptologic alliance which has outlived and outgrown anything even he could have hoped for.

I believe that is a fair and appropriate assessment. Denniston perhaps did not show enough imagination and forcefulness in the years immediately before war broke out, and the stresses of adjusting to the complexities of a multi-faceted counter-intelligence campaign taxed him. But he surely deserved that knighthood. There was nothing in the treatment of the French approaches, and the consequent negotiations, that singled him out for reproach, and he was out of the picture when the general desire to muffle the actions of 1931 became part of GCHQ doctrine. The initial suspicions I had that some stumbles over Enigma might have caused his lack of recognition were ungrounded, but the exploration was worth it.

Conclusions

As I noted earlier, one might expect that the historical outline would become clearer as the procession of historians added their insights to what has gone before. “All history is revisionist history”, as James M. Banner has powerfully explained in a recent book. But sometimes the revisions merely cloud matters, as with Dermot Turing’s XY&Z, because of a political bias, and a less than rigorous inspection of the evidence: the ‘definitive’ history eludes us. I believe I have shown how difficult it is to extract from all the conflicting testimonies and flimsy archival material an authoritative account of what really happened with the Asché documents. Perhaps the key lies with that intriguing character Wilfred Dunderdale – like some of his notable MI6 colleagues, born in tsarist Russia – who was at the centre of events in 1931, and for the next fifteen years, and thus could have been the most useful of witnesses. Denniston praised his role: the man deserves a biography.

It is nugatory to try to draw sweeping conclusions about the behaviours of ‘the British’, ‘the French’, and ‘the Poles’ in the unravelling of Enigma secrets. Tensions and conflicts were the essence of a pluralist and democratic management of intelligence matters, and that muddle was clearly superior to the authoritarian model. Sinclair was too cautious and he probably mis-stepped, Menzies was out of his depth, Denniston lacked forcefulness, Knox was prickly, Birch caustic, Travis conspiratorial. The mathematicians, such as Welchman and Turing, were brilliant, as was that cryptanalyst of the old school, Tiltman. Lamoine was devious and treacherous (he betrayed Schmidt in the end); Bertrand suspicious, resentful and possessive.

A significant portion of recent research has set out to correct the strongly Anglocentric view of the success of the Enigma project, and Dermot Turing’s XY&Z is the strongest champion of the role of the Poles. Perhaps the pendulum has temporarily moved too far the other way. His Excellency Professor Dr Arkady Rzegocki, the Polish Ambassador to the United Kingdom, wrote in a Foreword to Turing’s book:

In Poland, however, the story is about the triumph of mathematicians, especially Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henry Zygalski, who achieved the crucial breakthroughs from 1932 onwards, beating their allies to the goal of solving Enigma, and selflessly handing over their secret knowledge to Britain and France.

‘Solving’ Enigma again. No mention of the exclusive access the Poles had to stolen documents in the race with their allies (who were not all formal allies at the time), or who paid for the traitor’s secrets. No reference to the fact that they kept the French in the dark about their progress until they realized they desperately needed help. ‘Selflessly’ does not do justice to their isolation and needs.

Other experts have bizarrely misrepresented what happened. David Kahn (he who originally revealed Schmidt’s identity) in 2015 revisited the man he described as ‘World War II’s Greatest Spy’. He asserted that Poland had ‘solved’ the Enigma (while two other countries had not) because it had the greater need, and greater cryptanalytic ability – and was the only country to employ mathematicians as cryptanalysts. Yet in that assessment he ignores the fact that the Poles had exclusive access to purloined material that made their task much easier. It is a careless comparison from a normally very methodical analyst.

In summary, the Poles overall acted supremely well, although they were not straight with Bertrand over their successes, and should have opened up earlier than they did. For the same complementary security concerns that they had harboured in the 1930s, when the two surviving members of the trio (Rejewski and Zygalski) escaped to England in 1944, they were not allowed near Bletchley Park. It was all very messy, but could not really have been otherwise. It was a close-run thing, but the assault on Enigma no doubt was the overriding critical factor in winning the war for the Allies.

Envoi

As part of my research for this piece, I read Decoding Organization: Bletchley Park, Codebreaking and Organization Studies, by Christopher Grey, Professor of Organizational Behaviour at the University of Warwick. I picked up what was potentially a useful fragment of his text from an on-line search, and consequently acquired the book.

If the following typical sentences set your heart aglow, this book is for you:

What is problematic, at least in organization studies, is that this process of de-familiarizing lived experience has gone to extreme lengths.

Yet grasping temporality is not easy when research is conducted in a contemporary organization, whereas viewed from a historical distance it becomes easier to see how a process operates, or, as one might perhaps better say, proceeds.

In these and other ways, then, the BP case can serve as an illustration of both the empirical nature of modern organizations as located within a heterogeneous institutional and ideational network and the theoretical deficiencies of conceptualizing organization and environment as distinct spheres.

One of Professor Grey’s messages appears to be that those who experienced the labours at Bletchley Park are not really qualified to write or speak accurately about them, because they were too close to the action, and lacked the benefit of being exposed to organization studies research. On the other hand, the discipline of organization studies has become bogged down in its own complexities and jargon, with the result that the reading public cannot easily interpret their findings. Hence:

What I mean by this is that it has in recent years moved further and further from providing incisive, plausible and readable accounts of organizational life which disclose more of, and explain more of, the nature of that life than would be possible without academic inquiry, but which do so in ways which are recognizably connected to the practice of organizational life. Let me unpack that rather convoluted sentence. As is basic to all social science, organization studies is concerned with human beings who themselves already have all kinds of explanations, understandings and theories of the lives they live. These may be under-examined or unexplored altogether, or they may be highly sophisticated. Yet, as Bauman [1990: 9-16], amongst many others, points out, these essentially commonsensical understandings of human life differ from those offered by special scientists in several key respects, including attempts to marshall evidence and provide reflective interpretations which in some way serve to ‘defamiliarize’ lived experience and common sense.

When an academic writes admittedly convoluted sentences, but fails to correct them, and then has to explain them in print, it shows that the field is in deep trouble. The book contains one or two redeeming features. It presents one notable humorous anecdote: that Geoffrey Tandy was recruited because he was expert in ‘cryptogams’ (mosses, ferns, and so on), not ‘cryptograms’. And Grey supports those who believe that Denniston was poorly treated, and deserved his knighthood. But overall, it is a very dire book. Maybe those coldspur readers who arelocated within a heterogeneous institutional and ideational network might learn where your organization is failing you.

(I should like to thank Tony Comer most sincerely for his patient and wise help during my research for this piece, an earlier draft of which he read. He has answered my questions, pointed out some errors, and shown me some internal documents that helped shed light on the events. While I believe that our opinions are largely coincident, those that are expressed here, as well as any errors, are of course my own. Tony maintains a blog at https://siginthistorian.blogspot.com )

Primary Sources:

The Government Code and Cypher School Between the Wars by Alastair Denniston(1944)

The Official History of British Sigint 1914-1945 by Frank Birch (1946-1956 – published 2004)

The Ultra Secret by F. W. Winterbotham (1974)

The breaking up of the German cipher machine ENIGMA by the cryptological section in the 2nd Department of the General Staff of the Polish Armed Forces by Colonel Stefan Mayer (1974)

Bodyguard of Lies by Anthony Cave-Brown (1975)

Ultra Goes to War by Ronald Lewin (1978)

Most Secret War by R. V. Jones (1978)

British Intelligence in WW2 (Volume 1) by F. H. Hinsley (1979)

The Enigma War by Józef Garliński (1979)

Top Secret Ultra by Peter Calvocoressi (1980)

‘How Polish Mathematicians Deciphered the Enigma’, Annals of the History of Computing, 3/3 by M. Rejewski (1981)

The Hut Six Story by Gordon Welchman (1982)

The Missing Dimension edited by David Dilks & Christopher Andrew (1984)

The Spy in Hitler’s Inner Circle by Paul Paillole (1985; 2016)

GCHQ by Nigel West (1986)

The Ultra Americans by Thomas Parrish (1986)

Secret Service by Christopher Andrew (1986)

British Intelligence in WW2 (Volume 3, Part 2) by F. H. Hinsley, E. E Thomas, C. A. G. Simkins & C. F. G. Ransom (1988)

The Ultra Spy by F. W. Winterbotham (1989)

Seizing the Enigma by David Kahn (1991)

Codebreakers edited by F. H. Hinsley and Alan Stripp (1993)

Station X by Michael Smith (1998)

Battle of Wits by Stephen Budiansky (2000)

Enigma by Hugh Sebag-Montefiore (2000)

Thirty Secret Years by Robin Denniston (2007)

Dilly by Mavis Batey (2009)

GCHQ by Richard Aldrich (2010)

The Bletchley Park Codebreakers, edited by Ralph Erskine & Michael Smith (2011)

Decoding Organization by Christopher Grey (2012)

Gordon Welchman by Joel Greenberg (2014)

How I discovered World War II’s Greatest Spy & Other Stories of Intelligence and Code by David Kahn(2015)

Alastair Denniston by Joel Greenberg (2017)

XY&Z by Dermot Turing (2018)

Behind the Enigma by John Ferris (2020)

(Recent Commonplace entries can be viewed here.)