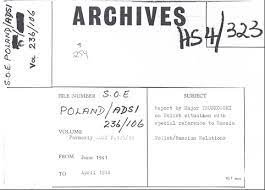

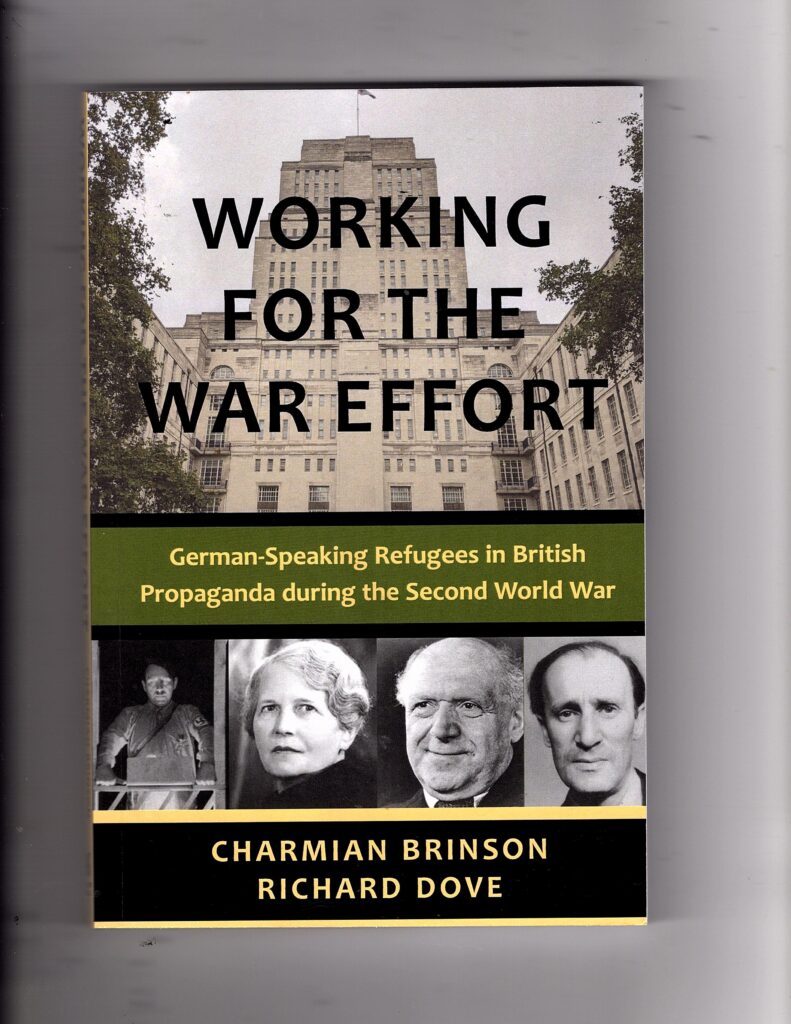

[Disclaimer: While I was researching last month’s piece on Smolka, I discovered a seminar delivered by Professor Charmian Brinson, of Imperial College, London, on November 9, 2017 – see https://www.imperial.ac.uk/events/99573/nothing-short-of-a-scandal-harry-peter-smolka-and-the-ministry-of-information/. I sent Professor Brinson an email, asking whether a transcript of her address was available. She did not reply. As I reported in my piece, I had found that an Austrian periodical had published such an article, but I had been unable to gain any response when I tried to order it on-line. Then, on February 1, one of my correspondents alerted me to the fact that Brinson had written a book on German-speakers working in British propaganda during the war. I had overlooked it, since it is not listed on her sadly out-of-date Publications page at Imperial College – see https://www.imperial.ac.uk/people/c.brinson/publications.html. I instantly ordered it, but also sent at that time an early draft of the following bulletin (an almost verbatim copy of what can be read below) to Mark Hollingsworth. The book arrived on February 5, and I saw that her Chapter 7 covers some of the same ground that I tread on. Her chapter is very strong on Smolka’s activities during the war, since she uses archival material that I have not seen, but she is otherwise cautious, and does not present any startling insights, in my opinion. Mr. Hollingsworth can attest to the fact that my research was carried out without her help, or access to her publication, in any way.]

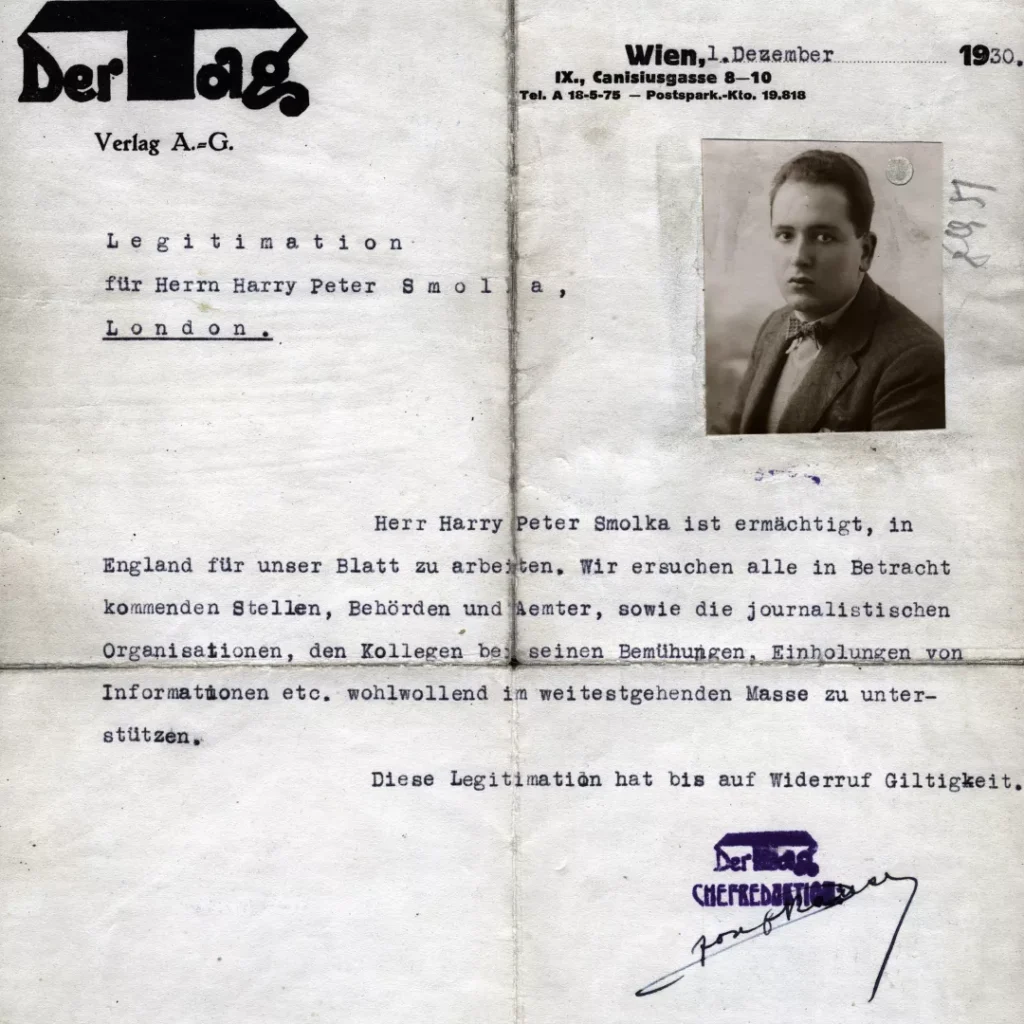

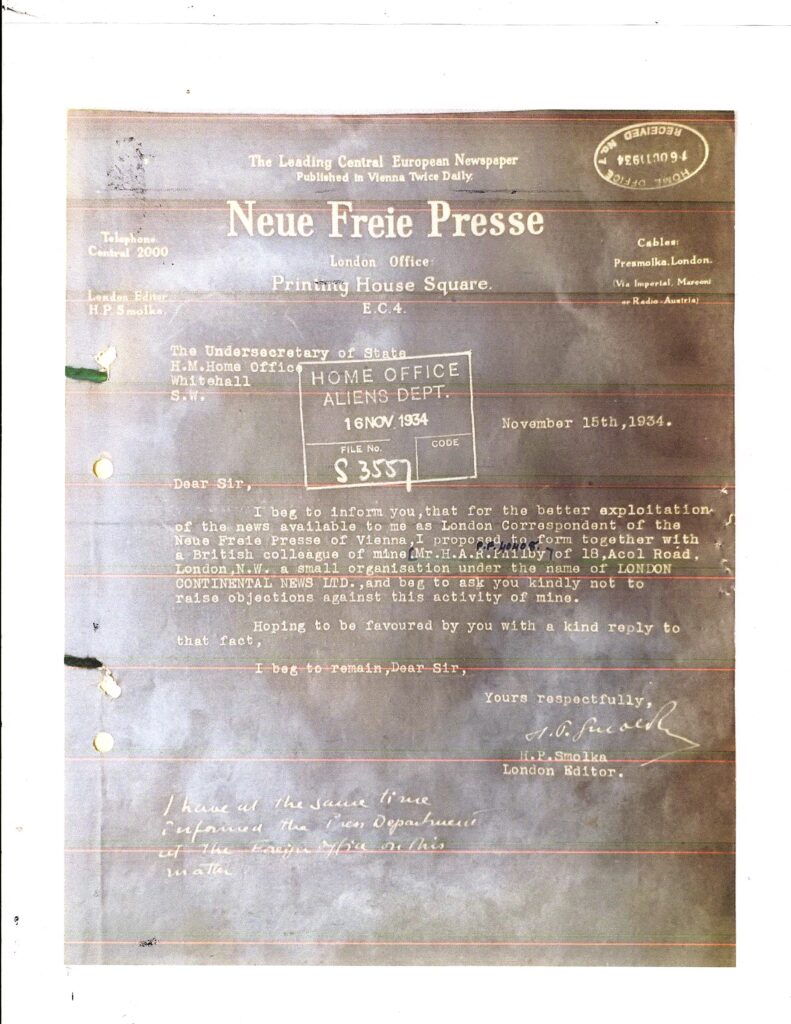

In the first bulletin of this two-part report (see https://coldspur.com/peter-smolka-background-to-1934/ ), I introduced Peter Smolka, presented a detailed analysis of the literature about him, and gave a brief description of the archival material on him released by Kew a few years back. Using his Personal File as an anchor, I then performed a detailed investigation into what I classified as the first chapter in his association with British Intelligence, namely the years between his arrival in the UK in 1930, and his rather bold declaration of his collaboration with Kim Philby in November 1934. This segment addresses the remaining five chapters in his career.

Chapter 2: 1934-1939 – Building Connections

Special Branch and MI5 continued to keep a watch on Smolka, although their quarry spent an increasing amount of time abroad. By the time that the Home Office replied to his request for permission over the London Continental News, on January 3, 1935, he had left for undetermined places. He boarded a boat to Dieppe on December 27, 1934, not returning until May 31, 1935, when he landed at Croydon Airport. No interest is expressed in his point of departure; no questions are asked how the journalist might have sustained himself during his travels. Lotty is not recorded as accompanying him. Nor is there anything on file until a report from the Immigration Officer at Tilbury, dated August 8, states that Smolka was ‘one of the outward-bound passengers on the M.V. ‘Felix Dzerjinsky’, when she left Hay’s Wharf for Leningrad via Dunkirk on 17.8.35.’

Smolka returned on the ‘Jan Rudzutak’ from Leningrad on September 24, but, again, no interest is apparently shown in what the intrepid traveller might have been up to. In fact that is the last entry in the file for 1935. Smolka was a little late to have been able to attend the Seventh World Congress of the Comintern, held in Moscow, but one might imagine that MI6 would have been intensely interested in learning more about how the Popular Front, activated after the Soviet Union’s treaty with France in May, was being received by the citizenry. After all, it had no other sources of intelligence within the country. Yet no evidence has been left behind of any debriefings.

The files do show a rather desultory interest shown by the Foreign Office in Smolka’s relationship with a Margherita Mantica (née Vesci), who had represented the Neue Freie Presse in the United States. An awkwardness can be detected in a concern that Smolka might trace any inquiry to the Foreign Office, but one fascinating new link crops up, in that Mantica is reported to be living in London with her brother-in-law, Lejos Biro, described as ‘a Hungarian, who is a literary supervisor and director of London Film Productions Limited’. As observant readers will recall, this was the company founded by Alexander Korda in 1932, and which was responsible for the Third Man project in 1948 and 1949. Biro was in fact Lajos Bíró, a playwright and screenwriter of some repute, who contributed a long list of titles to the Korda canon. Korda himself appears to have already been ‘recruited’ by Claude Dansey of MI6 by this time: some reports claim that it was Dansey who introduced Korda to Winston Churchill in 1934.

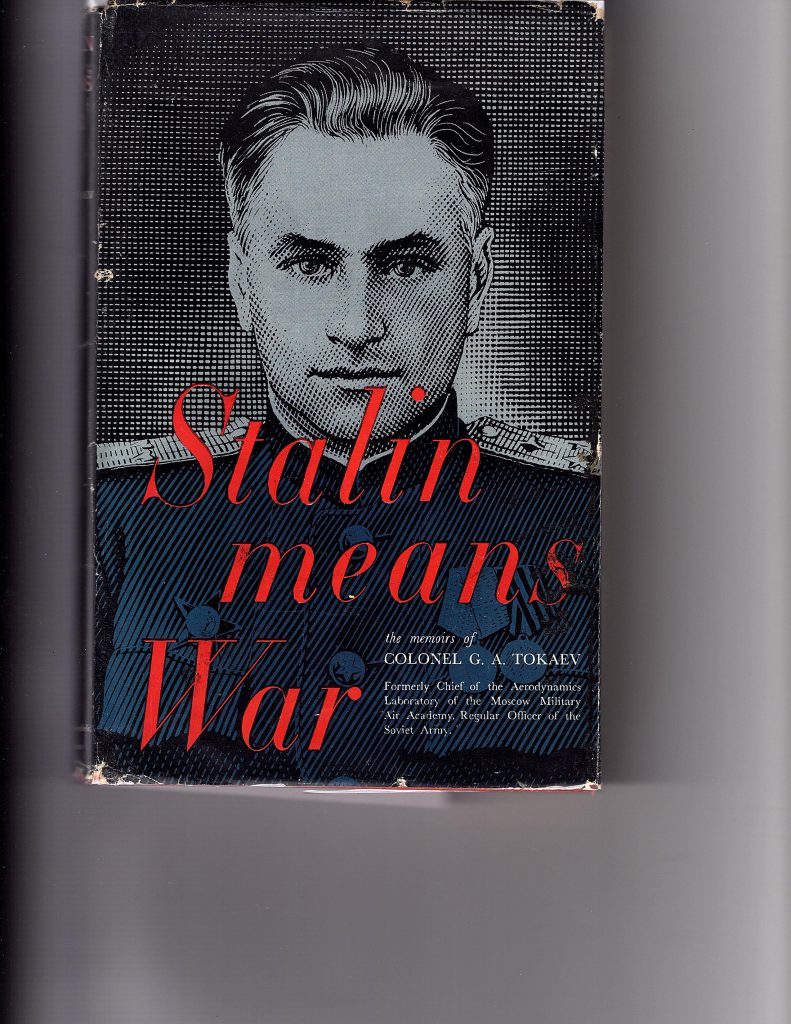

Nothing else is recorded until July 1936, when Smolka was shown to be off to the Soviet Union again, the Immigration Officer recording that he left on M.V. ‘Sibier’ for Leningrad on July 4. Strangely, there appears no record on file of his return. The reason for his voyage was to perform research for a series of articles that appeared in December 1936 in the Times, and was eventually published in book-form as Forty Thousand Against the Arctic, on April 29, 1937. Yet Smolka was very coy about the dates of his itinerary, neither specifying when his invitation to visit was made at the Soviet Embassy in London, nor when he left, nor when he returned. What is not in doubt is that his writings represented an utterly disgraceful show of Soviet propaganda, and the bravado with which Moscow perpetrated this ruse is matched only by the gullibility with which it was encouraged and endorsed by the Times. He had already delivered a paper at a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society on February 15, 1937 (‘The Economic Development of the Soviet Arctic’), in which he presented himself as an ‘unbiased non-Bolshevik’, again praising the initiatives of the Soviet government in opening up the Arctic, as they will prove ‘profitable and valuable to Russia and the world in general in the long run’.

In his Acknowledgments, Smolka first lists two Soviet apparatchiks, and then expresses his gratitude to ‘The Editor of The Times for allowing me to express again some of the thoughts first published in my series of articles in his columns’, next to ‘Sir Harry Brittain for his many acts of encouragement’, and then to ‘Mr. Iverach McDonald of The Times for acting as physician and surgeon to this book in its infancy’. What is extraordinary is the fact that the Editor of the Times during this period was Geofrey Dawson, a noted appeaser and member of the Anglo-German Fellowship. Harry Brittain was a Conservative politician with an unremarkable career. Iverach McDonald was an elusive character, described in the few items available on him as ‘an expert on Russia’, but where he derived his expertise, or whether that competence translated into a sympathy for the Soviet Union, is not clear. He was The Times’s Diplomatic Correspondent, and Dawson sent him to Prague in the autumn of 1938 to cover the Sudetenland crisis. Why all three gentlemen should have been taken in by this monstrous apology for Stalin’s penal colony is utterly perplexing.

I shall not spend time here summarizing the content of Smolka’s book. I leave it to the verdict of Andrew and Gordievsky: “The most ingenious fabrication in Smolka’s book was his portrayal of the hideous brutality of the gulag during the Great Terror as an idealistic experiment in social reform” (KGB, page 325). Yet the response of the two is unimaginative: they merely draw notice to the fact that Smolka’s reputation in the eyes of the Times and the Foreign Office was not damaged by this piece of propaganda was ‘curious’. (Then why not show more curiosity, gentlemen?) As for the author, he wrote in a note to the second edition (from New York, in December 1937): “I was immediately accused of having fallen victim to Soviet Russia’s exuberant and boastful optimism.” In his Appendix, he claims that ordinary people, ‘further away from the capital’ were able to talk to him freely, and that ‘their criticism of existing conditions and Government measures was even astounding to me at first’.

Yet Smolka’s fortunes improved markedly after this shocking event: little interest was shown in him. A routine inquiry from Indian Political Intelligence was made to Guy Liddell at the end of 1936. On July 13, 1937 Smolka thanked Erland Echlin, the London representative of Newsweek (who had been allocated a PF no., and apparently got into some trouble a few years later) for introducing him to his New York friends, and he must have departed soon after for New York. His departure was not noted, while an embarkation card shows him returning at Southampton on December 20. Likewise, no trace of his leaving the UK appears on file, but he is shown sailing in from Rotterdam on March 7, 1938. He had probably visited Austria, because a Special Branch report shows him as a member of the Austrian Self-Aid Committee on May 11.

His next step was naturalization, and Special Branch recorded his application on June 13, requesting a Search from MI5. His referees were the aforementioned Harry Brittain and Iverach McDonald (Diplomatic Correspondent of the Times), both of whom had encouraged and supported the creation of his notorious book, and Philip Burn, an editor at the Exchange Telegraph (who appears not to be related to Michael Burn, Smolka’s communist friend, of whom more below). Amazingly, nothing detrimental later than 1930 was discovered: it was if the Service turned a blind eye to the fact that this Communist had reinforced his admiration of Stalinism in his recent writings, which might indicate that his loyalty to the United Kingdom may have been in doubt. He travelled to Le Bourget from Croydon Airport on June 27 (itself an unusual and possibly proscribed activity while one’s naturalization request is pending), returning via Rotterdam on July 28. Maybe it was to visit his parents, Albert and Vilma, since a visa application on their behalf was submitted at the end of June. Despite some warning flagged in a police report concerning Smolka’s attendance at ‘certain meetings’, MI5 signed off on September 17 that there nothing ‘detrimental to the character of this alien’. Presumably the request was granted (the archive shows no evidence), and Smolka celebrated, on November 8, by announcing in the London Gazette that he was changing his name to Harry Peter Smollett. Two days later, he joined the staff of the Exchange Telegraph’s Foreign Department.

It is perhaps educational to compare the process that Smolka underwent with that of Georg Honigmann. On April 8, 1938, while pressing Smolka’s case, Rex Leeper in the Foreign Office brought to the attention of the Home Office the names of six other journalists whom the Foreign Press Association was recommending for naturalization, including Honigmann. Honigmann was an industrious journalist with artistic credentials, effectively exiled by the Nazis, who had gathered first-class sponsors with conservative leanings for his naturalization request, but, on bewilderingly pitiful evidence, had been twice rejected because his loyalty to his potential adoptive country was questioned. Smolka was an avowed communist, with dubious connections, who, having been installed as a journalist based in London, had swanned around Europe without being questioned about his business, and had engaged in heavy propaganda for a cause that was overtly opposed to the interests of the British Empire. Yet he breezes through his naturalization test. Many other worthy German or Austrian applicants were rejected. It does not make sense.

Next comes the puzzling gap in the record. In last month’s bulletin, I noted how nothing is recorded in sequence between November 1938 and September 1939, but a report at s.n.116k in KV 2/4178 (undated, but probably submitted by MI6 in December 1939) describes Smolka’s activities that attracted the attention of the Swiss military authorities. Having joined the Exchange Telegraph, Smolka built up a news service organization focused on Switzerland, Holland and Belgium. The report continues:

In April 1939 he went to Switzerland with letters of recommendation from Mr. Leeper, and in May he established a new service at Zurich, at the head of which he placed a Hungarian Jew named Leo Singer, who was subsequently expelled from Switzerland by the Swiss police. Smolka replaced him by Mr. Garrett, who represents himself as related to Mr. Chamberlain by marriage, and enjoys prestige on this account.

I shall return to the controversy of Smolka’s heavy-handed approach to trying to monopolize news delivery from Britain (and suspected intelligence leaks arising therefrom) in the next chapter, and simply note here that the apparent lassitude on MI5’s part in tracking Smolka at this period is more likely to be due to a policy of deliberate concealment. Smolka’s exciting adventures in Prague in March 1939 have been conspicuously omitted in the records of the Security Service.

As war approached, on August 30 Smolka’s name was submitted on a list of applicants for employment in the Ministry of Information, to which MI5 responded with a proposed ban on his employment. On August 31, Rex Leeper, head of the Political Intelligence Department in the Foreign Office, while claiming that ‘we’ did not suggest his name, defended the candidate, since Smolka ‘has been very well known to the Foreign Office for a considerable time past, and we have no reason to suspect him of any improper activities’. The very next day, a Mr. Strong (C2, Vetting), having spoken to Leeper, and being reassured about Smolka’s credentials, caved in, waiving the objection. The episode is all too pat, too prompt. In such a significant case, Strong would at least have had to confer with more senior officers outside his section. What is also extraordinary about Leeper’s enthusiasm for Smolka is that, in 1935, he had urged the removal of Harry Pollitt, General Secretary of the British Communist Party, from an influential BBC panel, shortly after Pollitt had returned from Moscow. Leeper was now committing a volte-face in favour of Smolka: one has to assume that he was being swayed by other more influential voices.

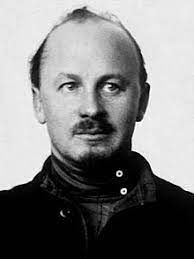

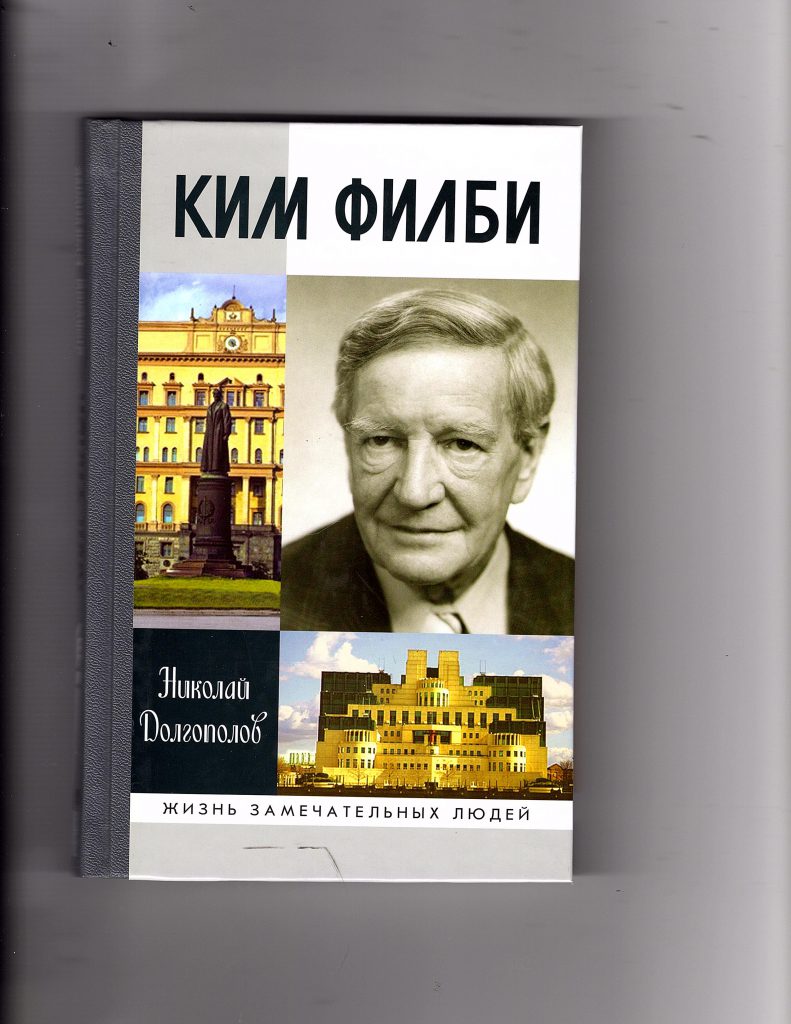

The final pre-war incident of note is Phiby’s putative recruitment of Smolka as an NKVD agent. The primary source for this event is Philby himself, and his account is typically deceptive and contradictory. According to what Oleg Tsarev discovered in the KGB archives (The Crown Jewels, p 157), in 1980 Philby had made a statement to his bosses that described the initiation. The key sentences run as follows:

Once, on my own initiative, I decided to recruit an agent, a Henri Smolka, an Austrian who was the correspondent of the right-wing Neue Frei Presse. In spite of working for the magazine, Smolka was hundred percent Marxist, although inactive, lazy, and a little cowardly. He had come to England, taken British citizenship, changed his name to Harry Smollett and later headed the Russian department in the Ministry of Information.

West and Tsarev comment that ‘this account coincides with the explanation offered by Philby to Gorsky and Kreshin in 1943, although in his original version he had given a few more details’. (They never state how they knew what Philby said at that time, nor do they provide documentary evidence of it. Kreshin had taken over from Gorsky as handler of the Cambridge Five sometime in 1942: Gorsky was replaced as rezident by Kukin in June of 1943.) I point out that Philby never gives a precise date for his ‘recruitment’ of Smolka: his reference to the Neue Frei Presse would indicate pre-January 1939 (since it ceased publication that month); the adoption of ‘Smollett’ simply indicates post-November 1938; the citation of the Ministry post as a future event defines some time before June 1941.

This claim needs dissecting carefully. Remember, Philby was talking to his KGB handlers, who, he must have presumed, were not entirely clueless about both Smolka’s and his own history. Philby never indicates that he knew Smolka in Vienna (or had even collaborated with him in the sewers), or that Litzy had been a friend of his. That the Presse was ‘right-wing’ is probably correct (elsewhere in Smolka’s file, it is described as an ‘Austrian Catholic Monarchist paper’): that it closed down in January 1939 is not debatable. It is perhaps significant that Philby refers to the defunct Presse and not the Exchange Telegraph, on which he and Smolka collaborated. Philby describes Smolka as a committed Marxist. He describes the latter’s career as the routine progression of an émigré, overlooking his visits to the Soviet Union, and his publication of pro-Soviet propaganda, but he appears to contradict his own assessment of Smolka’s character by pointing out his rapid rise in an important British Ministry. Lastly, the year should be noted: Smolka died in 1980, so Philby may have been asked to provide a false legend, now that the subject could say no more. The whole deposition looks like a clumsy ruse to conceal the KGB’s relationship with Smolka.

In The Philby Files (1994) Genrikh Borovik presents a slightly different tale (p 137). The KGB had agreed to let the playwright interview Philby in depth. Borovik relates what Philby told him:

In London there was a correspondent of the Austrian newspaper Neue Freie Presse, a man named Hans Smolka. I had met him back in Vienna. Whether he was a Communist or not, I do not know. He seemed to be, judging by his theoretical views – we had chatted more than once. But from the point of view of his own lifestyle, his love of comfort, I would not consider him a Communist.

This is another disingenuous item of testimony, bringing in Philby’s ‘acquaintance’ with Smolka, and introducing the notorious Vienna connection without describing the close connection through Litzy and Lotty. At the same time Philby underplays his knowledge of Smolka’s political affiliations, which must have been obvious to anyone exposed to the agent’s propaganda. The flow of Borovik’s narrative suggests that the recruitment occurred in the autumn of 1939, but Philby adds that he and Smolka ‘used to run into each other at receptions and cocktail parties’, indicating an extended pattern of social acquaintance before the ‘recruitment’ occurred. Yet Philby did not return to England from Spain until late July, met Gorsky for the first time in early September, and left for France as a reporter for the Times in early October, not returning permanently until June 1940. Gorsky was out of the country for most of 1940, but he reported meeting Philby again on December 24 of that year.

The absurdity of the saga is further intensified by commentary that West and Tsarev then make:

Philby’s recollection in 1980 of the ABO episode, which he considered mildly amusing, had caused pandemonium in the rezidentura and the Centre. Who was Smollett? Was he a counter-intelligence plant? What was the extent of his knowledge about the Cambridge ring? (The ABO episode concerns an infamous message from Moscow to London, dated June 14, 1943, in which the Centre assessed that the unreliability of the Philby/Burgess group had been confirmed by the unauthorized recruitment of Smolka, aka ABO.) Maybe this is simply an unfortunate choice of syntax by the authors, but the sentence declares that it was Philby’s ‘recollection in 1980’, not the ABO episode itself, that had wreaked such havoc in the rezidentura and Centre. That must surely be unintended. The suggestion is that the KGB in 1940-41 had no idea who Smolka was, and that Philby’s reckless move of introducing Smolka to Burgess and Blunt had caused irreparable damage to the security of the ring.

Yet, even if Gorsky and Kreshin in London, and Ovakimyan in Moscow, had indeed lost track of the status of some of their agents owing to the execution of so many in the purges (recall that when Ozolin-Haskin, shortly to be killed himself, reported from Paris to Sudoplatov about SÖHNCHEN’s [Philby’s] arrival in June 1939, Moscow did not know who SÖHNCHEN was), it beggars belief to imply that the London residency (Gorsky included) did not know who Smolka was. After all, he had publicized himself in his Times articles, his book, and had enjoyed a sponsored tour of the Soviet Union’s gulags. This farce is put into sharper focus by Gorsky’s report dated August 1, 1939, where he discusses the next step for deploying Philby productively:

In accordance with your instructions we recommended that he try to get a posting in Rome or Berlin. As for the proposal of ‘Smolka’ for ‘S’ [SÖHNCHEN] to become the nominal director of the Exchange Telegraph Agency, we write about it below, in a different section. ‘S’ is not inclined to accept that at the moment.

This must be a genuine article, provided to Borovik by the KGB. (And if it is a fake, an item of misinformation, it clumsily contradicts other plants.) It proves that Smolka was in regular contact with Gorsky and the residency before the war, and Gorsky’s openness in describing his activities indicates that he must have been a familiar figure to Moscow Centre. What is slightly surprising is the fact that Smolka is not identified here by his cryptonym, but the ‘Smolka’ in quotation marks may simply be the result of a transcription process. Moreover, the fact that Smolka had at one time been given the name of ABO (Абориген? = aboriginal?) would also show that he had been approved and recruited by the NKVD. Philby would not have had the authority to allocate cryptonyms, and the whole episode reinforces the notion that it was a clumsy attempt at planting a ‘spravka’ in the file by the KGB.

Indeed, the Mitrokhin Archive is the culprit here. On page 84 of The Sword and the Shield (by Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin) appears the statement that Kim and Litzi [sic, i.e. both] recruited Smolka in 1939, and that he was given the cryptonym, ABO. The story is attributed to Volume 7, Chapter 10, Item 4 of the Archive. As I have shown in the chronology above, such timing of the ‘recruitment’ was impossible: the entry is an item of disinformation. In KGB Andrew and Gordievsky were right, and Smolka had been recruited well before then. The whole account of Philby’s recruitment of Smolka is an absurd fiction.

Chapter 3: 1939-1945 – Propagandist in War

As soon as Smolka was recruited by the Ministry of Information, he started throwing his weight around and antagonizing people, yet continued to be defended by his chief mentor, the inscrutable Rex Leeper. One of the ongoing projects he took under his wing was the husbanding of a press agency called Defence and Economic Service, which sent ‘six articles a week on military and economic subjects in English and German to 568 newspapers on the continent’. Before the war, this had been an independent commercial enterprise, but by December 1939, Smolka had gained a subsidy from the Ministry to encourage wider dissemination on the Continent. Its editor was, rather astonishingly, an Austrian who had apparently passed the Aliens’ Tribunal, and was thus considered safe – one Dr. Paul Wenger. On December 2, Smolka felt emboldened enough to introduce him to the Press Officer at the War Office, a Mr. McCulloch, asking for information.

If the distribution in German, by an Austrian, of material gathered and synthesized from open sources widely around Europe was not considered controversial, the inclusion of possibly restricted information from the War Office should have raised eyebrows. Whether Defence and Economic Service was an alibi for the Exchange Telegraph is not clear, but Smolka soon resorted to threats when he expanded his service to Switzerland. A note on file reads: “Smolka has threatened to get the head of the Agence Suisse (Keller) deprived of his British visa, if he refused to take his news service”. It adds that Reuters and Havas have refused to take Smolka’s service, with the result that Smolka ‘had a virtual monopoly of British news in Switzerland, Holland and Belgium’.

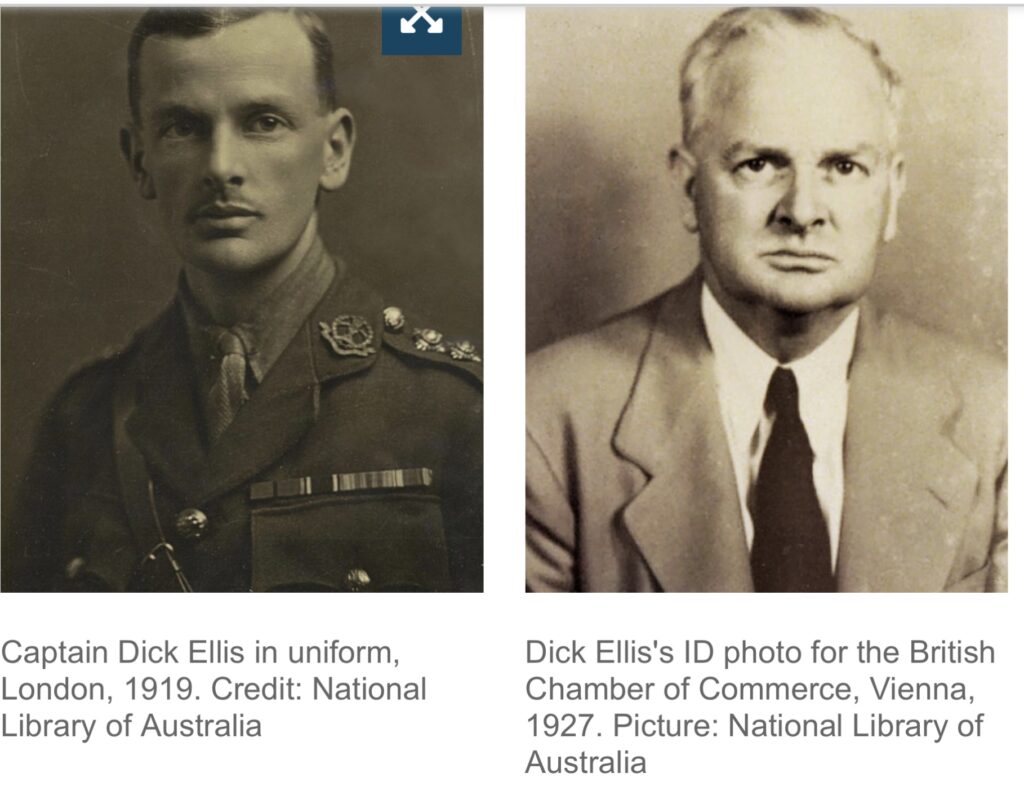

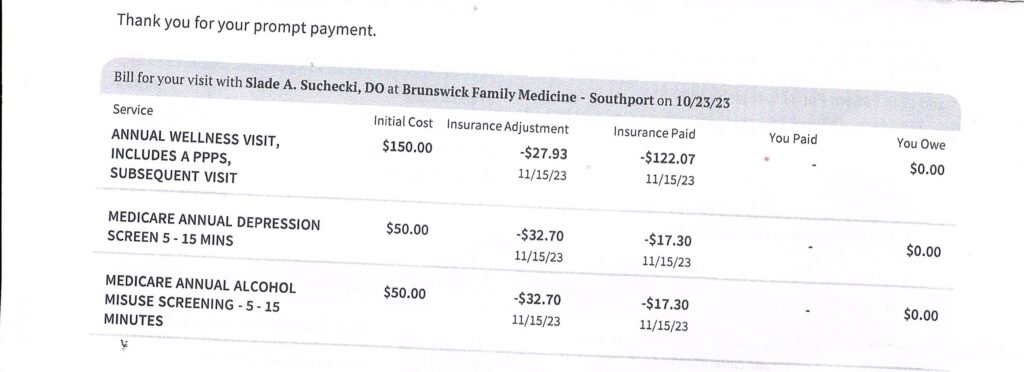

Indeed, on January 12, 1940, Major-General Frederick Beaumont-Nesbitt, Director of Military Intelligence, was moved to complain in writing to the head of MI5, Sir Vernon Kell, drawing attention to leakage of confidential information, pointing the finger at Smolka, and, after noting that he knew that Smolka had been hired despite the objections of MI5, observed, in manuscript, that ‘Smollett’s employment in his present position seems to me nothing short of a scandal!’. His deputy, Brigadier Penney, approached MI5 simultaneously at a lower level (Major Lennox), and the complaints came to Dick White’s attention.

White’s response was meek. He instructed Mr. Maude of ‘S.L’ (in actuality Section B19, ‘Rumours’) to help him formulate a reply. A letter of January 19 merely temporized, indicating that ‘Smolka is not an easy problem’. But not much happened. War Office people sniffed around; B7 in MI5 (a section that must have been soon closed down, since no reference to it appears in Andrew, Curry or West) interviewed Wenger, confirming that his salary was being paid by the Ministry, and concluding that he was genuine. A Mr Bret, London representative of the French Commissariat á L’Information, reportedly echoed the rumour of leakage. Special Branch noticed wireless equipment at Smolka’s house at 16 Fitzjohns Avenue, N.W. 16.

A long report on Smolka was submitted by Maude on February 4, 1940. At first glance it seems extraordinary that such an important undertaking should be delegated to such an irrelevant section. Nigel West, in MI5, reports as follows:

At one point before being posted to Washington [elsewhere he states that Maude became a Regional Security Liaison Officer], John Maude was in charge of a ‘B’ Division section, B19, which ‘investigated the source of rumours’. He soon discovered that the unit, which consisted of about a dozen solicitors, was doing very little useful work and these legal brains spent much of their time answering letters that had arrived denouncing various individuals as enemy agents. Maude wrote a firm memo to Richard Butler and the greater part of B19 were transferred to more productive duties.

It seems irresponsible: the DMI had made a significant inquiry into a possible case of information leakage, yet the task was given to a solicitor investigating rumours. It is more likely that White personally trusted Maude (who would later become a K.C.) to perform a more thorough job than anyone else, or else wanted to keep the investigation out of the mainstream. If White orchestrated a response to Beaumont-Nesbitt, it has not survived.

After providing a recapitulation of Smolka’s career (which in its details reflects precisely what is on file, suggesting perhaps that it had been weeded already), Maude makes a number of points. He suggests that Mr Christopher Chancellor of Reuters may have been casting aspersions on Smolka’s character. He introduces the name of Sir Robert Vansittart as a Smolka champion, alongside Charles Peak. He had interviewed M. Brett [sic], and discounted what he said as evidence that Smolka had contributed to the leaks. He concedes that Smolka was unpopular, and offers the following opinion: “I must say that to me it passes all understanding that the Ministry of Information should employ a German [Dr. Paul Wegner, actually Austrian] to write articles on English military matters.” He notes that Smolka had put forward a proposal that all reports from British Press Attachés should pass through his hands and be edited by him before being issued, (which appears to me a preposterous suggestion) and concludes that ‘the power and influence of Mr. Smollett has [sic] been increasing and ought to be halted’. At least, the Ministry of Information should have been closely surveilling all material that the Exchange Telegraph sent out of the country.

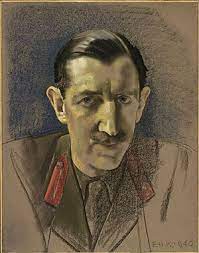

Valentine Vivian of SIS then puts in his oar. On April 8, Vivian writes to Major Marshall of MI5, referring to the latter’s minute of March 29 on MI6’s ‘Vetting’ Form dated February 13. The Minute Sheet lists the arrival of the Form from SIS on February 16 as item 122x, but the entry has curiously been pasted over another item. Indeed, the original trace request is present, directed at Captain Butler, and it expresses a desire to ascertain the reliability of ‘Smollett, possibly Smolka’, who ‘was formerly with one of the news agencies in Switzerland’. Marshall responds with the conventional bio of Smolka, describes him as ‘very able’, states that he is second-in command to Professor E. H. Carr, the Director in the Publicity Department of the Ministry of Information, but does add that Smolka acted in a very high-handed manner in Switzerland in April 1939.

What is going on here? How could anyone in SIS with the authority to submit a Vetting Form be so ignorant about this prominent character? And why would he be interested in the circumstances of a domestic ministerial role, which was MI5’s responsibility in the first place? Was it a test to determine how much the grunts in MI5 knew? Whether SIS was grateful for the information it received is not recorded, but all that Vivian has to say is:

It may just interest you to know that out information is to the effect that Mr. Smollett is in no sense second in command to Professor E. H. Carr, but occupies a much more subordinate position as Foreign Relations Press Advisor in the Ministry of Information.

Well thank you, Vee-Vee, for that shrewd contribution. Those kinds of insight are what led you to having a corner office, I suppose. It is all quite absurd. Moreover, the archive declares elsewhere that Carr was subordinate to Smolka, who exerted a strong influence over him.

On May 17, 1940, the Minister of Information, Duff Cooper, cancelled Smolka’s Daily Press Review as a waste of paper and time. An announcement about it in the Evening Standard was noticed by Indian Political Intelligence, who reminded B4b of MI5 of the suspicions previously harboured over Smolka, and inquired whether MI5 was now satisfied with him. Dick White responded on June 8, attributing the suspicions to the fact that Smolka had ‘a most unattractive personality’: he was otherwise politically reliable. Meanwhile, Smolka was pushing ahead, trying to get his father a place in the Ministry. Leeper then tried to gain him (the son) a post on Intelligence Duties in the War Office, which prompted Colonel Jervois to seek MI5’s advice. On July 26, B19 (a John Phipps?) replied, judging that Smolka could not be trusted absolutely, and thus recommended that he not be hired for such a role. Yet this was absurd: if the Director of Military Intelligence had protest strongly about Smolka six months beforehand (a complaint not formally responded to, according to the records), why on earth would the War Office be considering him for intelligence duties?

The rest of the year proceeded in similar fashion, with occasional questions raised about Smolka’s reliability, while the man himself increased his influence. His secretary, Stella Hood-Barrs, was investigated for passing on possibly encrypted information to German emigrants in Holland, a charge that Vivian dispelled. Albert Smolka, his father, was released from internment in August. The Air Ministry showed interest in Smolka fils in October: Squadron-Leader Pettit (of D3 in MI5) cleared him again, but reminded Wing Commander Plant that he should not be employed on Intelligence duties.

In that way the archive peters out for 1940, with no further entry until March 1941. It was a puzzling year, since any searching questions about Smolka’s reliability appeared to have been quashed without any documentary evidence. What was Beaumont-Nesbitt told, and what was his response, for instance? That dashing officer was forced from his post on December 16, 1940, having made a mess of signalling an invasion alarm in September (see https://coldspur.com/the-mystery-of-the-undetected-radios-part-vii/), but there had been plenty of time for him to follow up on his vigorous inquiry. Perhaps someone had had a quiet word in his ear. Maude’s judgment from April 1 would seem a fitting analysis of the situation: “My own view is that Mr. SMOLLETT has now entrenched himself behind a sort of super Siegfried Line erected by the Foreign Office and it is quite impossible to dig him out at this stage of the war.”

Smolka was heading the Central European Division of the Ministry of Information at the start of 1941. His progress was marked in August, soon after Barbarossa, when the Soviet Union became an ally, by his being appointed head of the Anglo-Soviet Liaison Section at the Ministry. Andrew and Gordievsky, in KGB: The Inside Story (pp 326-328), using Ministry of Information and Foreign Office archives, give an excellent account of Smolka’s labours for Soviet propaganda during the war, and I shall thus not repeat the whole story here. Last month I recommended W. J. West’s The Truth About Hollis as an extremely valuable contribution, and I can now suggest that readers turn to Chapter 7 of Charmian Brinson’s Working for the War Effort for a comprehensive account of all that Smolka did to promote the Soviet cause in the UK – as well as enabling the Russians to understand a lot more about Britain’s culture and its war effort. Meanwhile, Smolka and his cronies were still being watched carefully. A furtive telephone call with Andrew Revai is listened to in May: Revai was a journalist, a Hungarian exile who had been recruited by Guy Burgess, and had been given the cryptonym TAFFY (not that that was known by the Ministry of Information at the time). Smolka tried to get him into the Ministry (or the BBC), but experienced resistance. Using an inside source, B8c reported, in August, that ‘Smolka is a Communist and has good connections with the C.P.G.B’.

Thus 1941 wound down with further desultory efforts to track what Smolka was up to, some dubious broadcasts by the Hungarian section of the BBC taking up most of the bandwidth, and MI5 following lazily some of Smolka’s ‘Peace’ initiatives. His wife, Lotty, was cleared to work as a Research Assistant at the Political Warfare Executive. [Note: Her employer is not recorded here, but appears in a later bio from 1951, proving that several routine items have been weeded.] Likewise, little happened in the first half of 1942, until an important entry is made on June 30. Mr Wolfgang Foges writes to the Ministry of Information about a book titled Russia Fighting 1812-1942 that he has written in collaboration with Smolka, and to which Ivan Maisky, the Soviet Ambassador has consented to write a forward. In his letter, Foges notes that Smolka ‘has known me since childhood’: we thus have an important confirmation of the relationship described in his son’s memoir (see coldspur of last month). (Note: Foges was the founder of the firm Adprint, which introduced the technique of commissioning material and having it published externally. With some assistance from the Ministry of Information, in 1941 it launched the excellent series Britain in Pictures, of which I own several dozen volumes.)

Soon after, Kim Philby enters the picture. Roger Fulford, now Assistant-Director of F Division, had beforehand been responsible for tracking Peace Movements and related activities in F4. On September 10, he writes to Dick Brooman-White (B1g), enclosing an anonymous report (that probably came from elsewhere in F Division) that sets out the following statement concerning Smolka: “In November 1934 with a certain H. R. Philby he formed a small press agency called London Continental News Limited”. The couching of Philby in those terms is presumably not ironic, and it shows how well encapsulated the officers in MI6 were from even some members of its sister service. Yet Fulford knows more: he tells Brooman-White that the man referred to ‘is almost certainly our mutual friend in Section V’, and he requests of his colleague (who, being responsible for Spanish espionage, would have been the liaison with Philby at the time) that he contact Philby to learn what information on Smolka he can give them.

Philby might have been a little alarmed at this connection having been unearthed, but tried to play it off with a mixture of lies and dissimulation. Having spoken to Philby, Brooman-White responds to Fulford, two days later, as follows:

The press agency in question never actually functioned but Philby knew Smollett quite well at the time. He says he is an Austrian Jew who came to this country about 1920 [!!], did well in journalism and is extremely clever. Commercially he is rather a pusher but has nevertheless a rather timid character and a feeling of inferiority largely due to his somewhat repulsive appearance. He is a physical coward and was petrified when the air-raids began. Philby considers his politics to be mildly left-wing but had no knowledge of the C.P. link-up. His personal opinion is that SMOLLETT is clever and harmless. He adds that in any case the man would be far too scared to become involved in anything really sinister.

A shrewd but still clumsy item of denial. Yet it appeared to settle things.

1943 is a barren year for the Smolka archive, with only one insignificant entry in January. The cupboard for 1944 is similarly bare. The only event is the appearance of Baroness Budberg, the mistress of H. G. Wells, and another Soviet agent. A Special Branch report dated April 27, 1944 reveals that Budberg ‘was instrumental in getting . . . . SMOLKA . . . his job as chief of the Soviet Relations Branch of the Ministry of Information, displacing a non-Communist’. No source or explanation of this snippet is provided. Suddenly, the war is over, and the archive jumps to December 8, 1945, where a report from E5l (‘Germans and Austrians’) reveals the following important information:

Hans WINTERBERG, Hilde SCHOLZ, Dr. George KNEPPLER and Dr. Walter HOLLITSCHER are reported to be leaving for Austria in the course of the next few days, most probably for Prague. W. HOLLITSCHER has made an arrangement with Peter SMOLLETT, correspondent of the ‘Daily Express’, to live in his house in Vienna. SMOLLETT and his wife, Lotty, are back in London after having visited Austria, Hungary, Jugoslavia, and Roumania, but intends to go back to Vienna. Though not party members, they are regarded as sympathisers, and, as well as Walter HOLLITSCHER, they are on friendly terms with Lizzy FEABRE, nee Kallman (see report of 9.9.45) and Fred GREISENAU [?] @ HRJESMENOU (see report of 3.9.41).

A hand-written note enters ‘PHILBY’ over ‘FEAVRE’.

Smolka is now apparently so well-established that no questions are asked about the purpose of this highly provocative travel. Moreover, an extraordinary visit to Moscow in 1944 (never an easy journey) has been omitted completely from the record. A correction is entered, however, four days later. While Lotty is recorded as remaining in London, Peter is now in Prague, and is supposed to be going to Vienna shortly. Will our gallant security personnel be able to keep tabs on him?

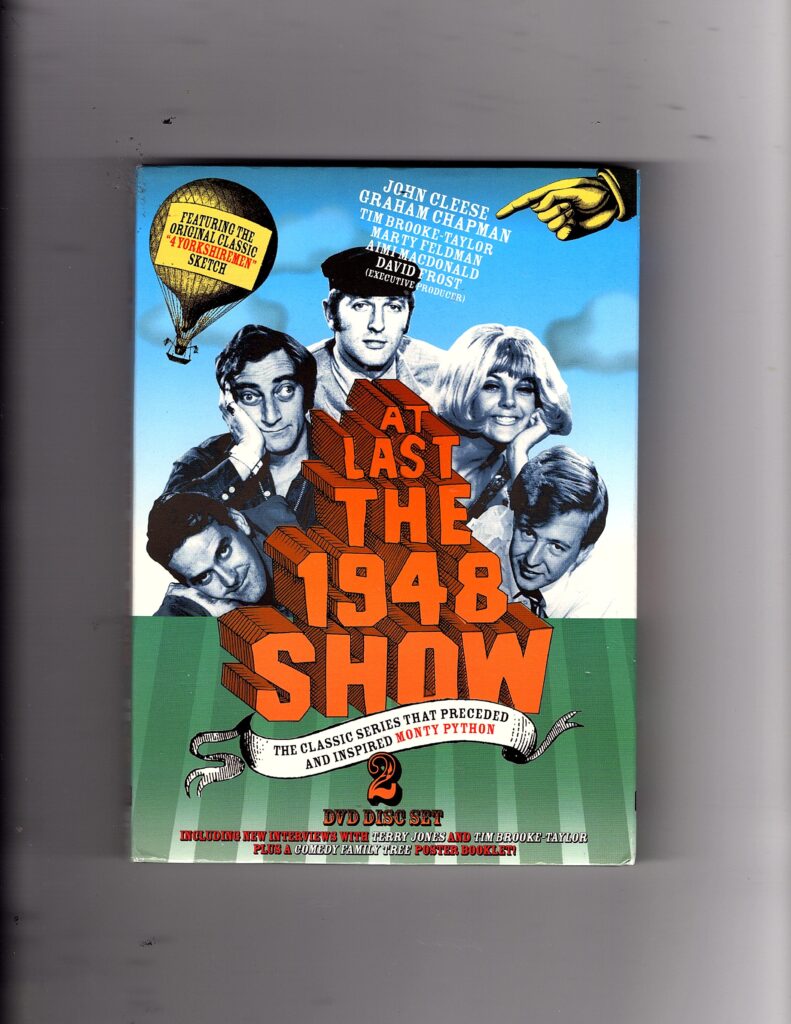

Chapter 4: 1946-1948 – The 1948 Show

It is in fact Kim Philby who kicks off the 1946 Smolka season. On February 26, 1946, he writes a brief letter to Major Marshall, reminding him of the February 1940 vetting form, and inquiring whether MI5 has any information about Smolka’s activities since then. Had MI6 lost track of him, perhaps? John Marriott of F2c responds on March 12. He describes Smolka’s role at the Ministry of Information, remarking that he visited the U.S.S.R. in February 1944, on official duties, but left the Ministry in June 1945, or near then. He goes on to list a number of associations that Smolka had with known Communists between 1941 and 1945, including Betty Wallace alias Shields-Collins, Agnes Hagen, and Eva Kolmer, as well as the afore-mentioned Hollitscher and Hrjesmenou. At the end of June 1945 Smolka went to Czechoslovakia as Central European Correspondent accredited to the Daily Express.

Since Marriott also asked Philby for any further information he had, a reply came back on March 29 (not necessarily from Philby: it is unsigned), declaring that MI6’s representative in Vienna has said that Smolka is now representing the Daily Express there, and adds the somewhat disturbing news: “There are indications that he has been asking questions about Austrian Barracks Unit, and about our representative in VIENNA. Also that he is cultivating Ernst FISCHER, former Minister of Education and his wife, and is in contact with TITO Yugoslav circles in Vienna.” This was, however, not the Ernst Fischer residing in the UK, a communist who worked for the BBC during the war, and whose PF number is annotated as 45068 (unavailable at Kew) on the letter, but another Austrian Communist, a future Minister of Education, who had spent the war in Moscow.

A follow-up revealed that Smolka must have returned to the UK to pick up his family, as a Special Branch report of April 24, 1946, indicates that they all left from Croydon Airport for Prague that day. MI6 had not been doing a stellar job of tracking his movements. Another report suggests that Smolka remained in Britain while his wife and daughter flew to Austria, but on May 2 M. B. Towndrow of F2a informed Philby of the departure of the four, and he follows up by stating that the renowned Communist Hollitscher is still staying at Smolka’s flat in Vienna. (One might expect the MI6 station in Vienna to be responsible for collecting such information, rather than MI5, but no matter.)

B2B starts to get excited about Smolka again, and it compiles another dossier. A source called ‘VICTORIA’, who had accompanied Smolka to the Czech-Austria frontier in 1938, has submitted a note that endorses Smolka’s communist sympathies. But the wheels continue to grind slowly. In November 1946, MI6 developed a report on Political Journalists in Austria, in which Smolka featured, and it shows an increasing trend. An extract reads:

He [Smolka]came to Vienna as a representative of various English newspapers. His articles are regarded by Austrian Government circles as anti-Austrian, particularly those in ‘Reynolds News’. His fortnightly ‘tea’ soirées at his villa in Hietzing, VIENNA XIII, are a meeting place for leading Russian and Austrian Communists. He has been having difficulties with his British employers and is now trying to gain a firm footing in the Vienna Press. Ernst FISCHER has engaged him as Foreign Editor for ‘Neues Österreich’ and it was he who reported on Dr Gruber’s recent activities in Paris at the Conference.

In these circumstances it might seem odd that Smolka would return to Britain. But maybe MI6 facilitated his return, as it had business to discuss. A report dated February 10, 1947, indicates that Smolka is once more leaving the country, destined for Austria, that he is still employed by the Daily Express, and that he has ‘O.B.E.’ proudly attached to his name on his passport, issued in July 1945. By July, Milicent Bagot is being warned of Smolka’s alarming behaviour. A letter from MI6, based on intelligence from the Vienna station, says that Smolka ‘attends Mr. Helm’s confidential background talks to British newspapermen concerning H.M.G.’s policy, etc.’. It was presumably hard to turn away an accredited journalist for the Daily Express who had been awarded the O.B.E., but suspicions about Smolka’s true allegiances must have been growing. MI6 believes that it has ‘adverse information of a security nature’ against Smolka, and Helm wants to know what it is. Its representative (Philby is no longer around, having been removed from his post as head of Soviet counter-intelligence in December 1946, and been posted to Istanbul) writes to Miss Bagot:

To assist us in concocting this prophylactic, we should be very grateful if you would please send us a summary of your more recent adverse information about Smollett.

That is an odd choice of words. ‘Concocting’ and ‘prophylactic’ suggest that the process is merely a charade, a going-through the motions, and that, moreover, Bagot is in on the game. She was probably not the right person to jockey with on these matters, however. G. R. Mitchell, of B1a, then takes charge, but merely informs his MI6 contact that MI5 has nothing to add to the summary that was sent over on March 12, 1946. And then a new appointment occurs. On February 9, 1948, B1a reports that Smolka has just been appointed as Times correspondent in Vienna, replacing a Mr. Burns [actually ‘Burn’], who was also a Communist (and who incidentally had a PF, numbered 69202, created for him, again not available at the National Archives). Smolka had apparently switched from the Daily Express to Reynolds News as he did not like the paper’s politics, yet that newspaper can hardly have changed its political stance in the period that Smolka worked for it. MI6 confirmed this news to J. L. Irvine on March 2, reinforcing the fact that MI6 was a bit slow on the uptake.

Yet before this, Smolka had become friendly with two fresh visitors from Britain, Antony Terry and his wife Rachel. Terry, with a distinguished war record, had been recruited by MI6 through Ian Fleming, and had cover as a correspondent for the Sunday Times. In fact, MI6 had insisted that he, a divorcé, marry one of his girl-friends before being posted to Vienna, as they required their officers to have the profile of a stable married man. Terry and Rachel Nixon (also divorced) had consequently undergone a wedding ceremony in April 1947. In June, Rachel, a rather dewy-eyed ingénue as far as the realities of Communism were concerned, met Smolka for the first time – presumably in the company of her MI6 husband. As newsmen, the pair would have inevitably come across each other. (Prompted by an article by Philip de Mowbray of MI6 about Soviet spies, Rachel, writing under her nom de plume of Sarah Gainham, recalled the events in a letter to Encounter magazine in December 1984.)

Rachel became especially friendly with Smolka’s wife, Lotty, but Peter apparently also opened up to her. What is significant for the story is the fact that Smolka unabashedly declared his sympathies for the Soviet system immediately. He described his work in Moscow during the war as editor of a news-sheet called British Ally (and we thus learn what his mission there was about), while avowing to Rachel his admiration for the Soviet form of government, which was ‘more democratic’ than the British way. Rachel then explains that Smolka was uniquely served by the Soviet administration in south-east Vienna, in that his family factory in Schwechat, unlike all other such properties, was not appropriated by the Russian authorities. A sensational anecdote then appears (which text I recorded last month):

In November Picture Post wanted an article on a foreign correspondent’s life in an Occupied city, and Peter proposed this to my husband as something in his gift. Smolka had the permits necessary to go to such places as Klosterneuburg, impossible to get from the Russians except on an official level. He also invited us and the photographer, the wife of the editor of Picture Post, to dine at the British Officers’ Club with a woman Russian colonel, whose picture duly appeared with us all in the magazine. [The magazine identifies her as Major Emma Woolf: the photograph was taken at Kinsky Palace on January 10, 1948.] This was something so unheard-of that even I could see something odd in it. It could only have occurred with official Soviet approval, and to get permission for foreign publicity of that kind proved intimate and high-level contacts.

One could well imagine that Antony Terry, who had assumed responsibility for some of Kennedy Young’s agents, would have been initially impressed, but secondly shocked, by these events, and reported them to his boss. The timing is very poignant, for we are now in the middle of the period of the ‘Third Man’ extravaganza, about which Smolka’s files are ostentatiously silent. One might imagine that after the growing concerns about Philby after the Volkov incident (September 1945), the Honigmann business in the summer of 1946 (including the weird divorce), and the decision by Menzies to move him out of the critical counter-intelligence role, MI6 might have started to investigate some of Philby’s cronies. And Smolka would have been an obvious candidate. After all, if the Secret Service believed that Smolka had been some kind of asset of theirs, with the plan of his being able to help in post-war counter-intelligence work against Moscow and its satellites, and had protected and fostered him during the war, it would be of utmost concern if he drifted away, did not inform them of his movements, and increased his involvement with dedicated Communist cadres. This now appeared to be what was happening.

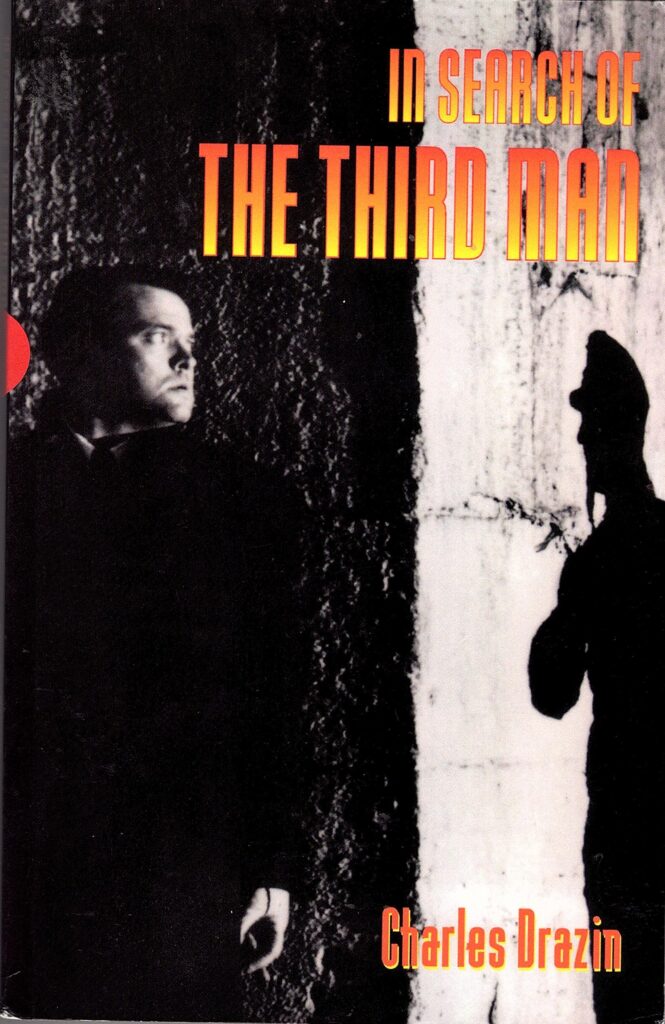

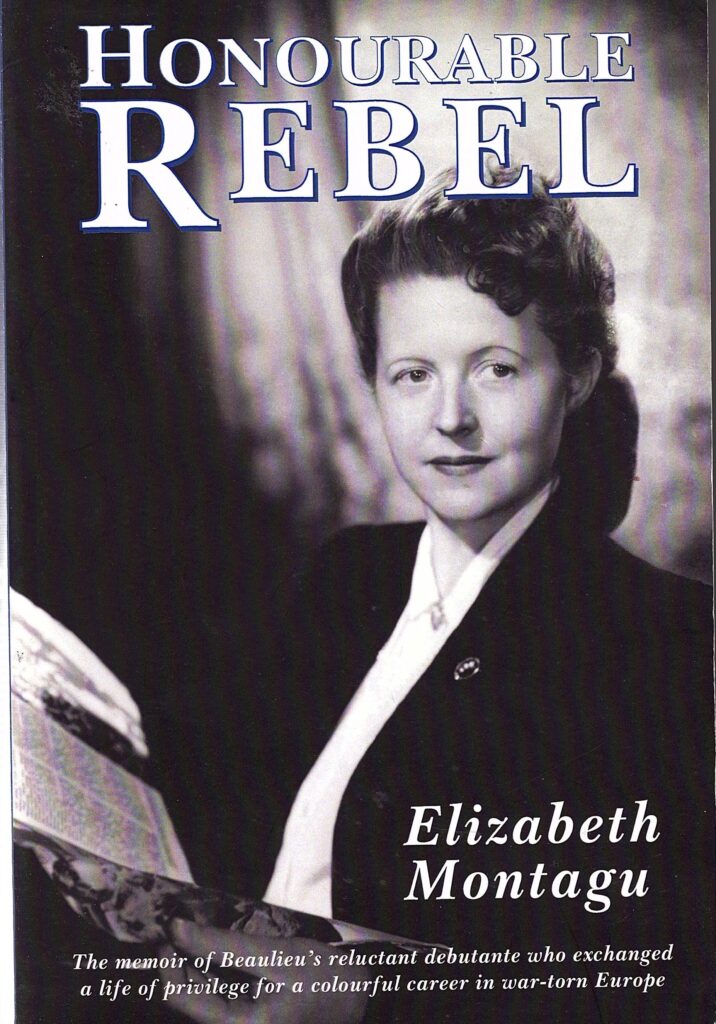

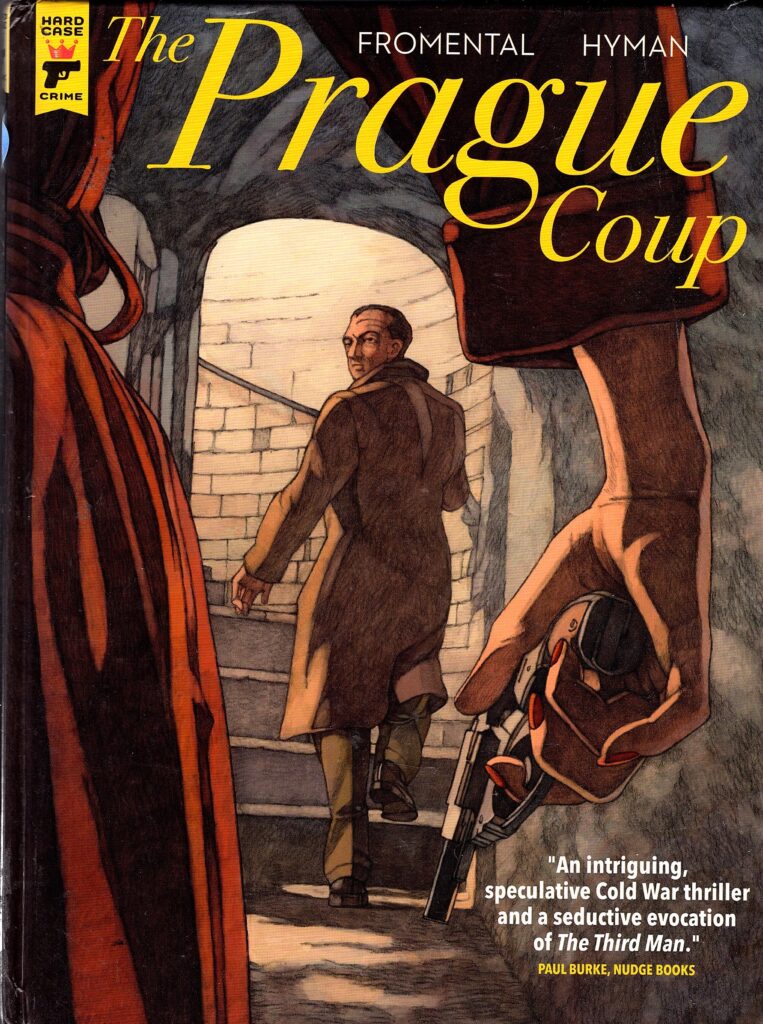

In last month’s bulletin, I laid out the discrepancies and contradictions in the accounts of Graham Greene’s meetings with Smolka in Vienna in early 1948. The dominant evidence is that Greene was asked to go to Vienna to sound out Smolka in as discrete a way as possible, with a plausible reason for being there, with his presence, as a known close colleague of Philby’s, representing no threat to Smolka, unlike what any approach by the local MI6 station would have constituted. I believe it is impossible to determine, from the sources now available, exactly what happened in the planning and execution of Graham Greene’s visit to Vienna and Prague. Every participant had a valid reason for obfuscating the truth. Yet the evidence of Drazin and Fromenthal (see coldspur last month) suggests that in November 1947 MI6 made a decision to send Greene and Montagu on the mission, and the arrangements were facilitated by the close relationship that Korda enjoyed with the Secret Service.

Whether the projected research into the ‘Third Man’ plot was a lucky coincidence, or whether Greene’s findings in Vienna actually drove the decision to stage the film there is a fascinating question. The plan had hitherto been to have the action take place in London: Korda’s claim that he needed to use the Austrian capital since he had pre-war assets there cannot be relied upon. He was notoriously bad with money, and it is not clear what form those assets took, or whether they were in fact liquid. Moreover, all the later explanations of Smolka’s contribution to the plot, with their apparently convincing details about his literary agents, may have been an elaborate fiction, designed to turn attention away from the real reason that Greene needed to spend time with him.

Smolka was in a precarious situation. As a Soviet agent and a British subject, he could have stayed in the United Kingdom relatively safely, unless he started making anti-Soviet noises, when Sudoplatov’s Special Tasks forces would have been sent out to assassinate him. But he was of little use to the NKGB in London, having lost his job when the Ministry closed down, the war propaganda cause complete, and his lack of access to vital secrets negating any value he may have had as a spy. Smolka would have been needed back in Austria or Czechoslovakia to help build Socialism. And that is where his MI6 sponsors, having nurtured and protected him for so long, wanted him, too, to deliver on his side of the bargain, and inform them about the communist cadres. Hence the cover of a journalist, which, after all, was his trade.

Yet it would have been difficult to masquerade as a bemedalled British toff at the same time as exercising a role as a servant of Stalin. The Austrian Communist Party would be looking for his full, energetic support, and that would not involve high-living it with his English colleagues at the Press Club. Furthermore, there would be many communists in Prague and Vienna who did not know that he had been recruited by Stalin’s organs fifteen years earlier, and they would have harboured great suspicions about this rather obvious plant. When Smolka travelled to Czechoslovakia on his way to Austria, the customs and immigration authorities in Prague would have noticed his British passport (although the O.B.E appendix would not have been present in June 1945). Indeed, that later got him into trouble at the Slánský trial in November 1952, when he was publicly denounced as an ‘imperialist agent’.

Thus Smolka had a decision to make, and soon decided that he had to boost his Communist credentials, and slough off the British Intelligence skin. That is presumably why he started praising Soviet democracy to his English colleagues, vaunted his connections with Soviet Military Intelligence, and did not conceal the help he received in restoring his father’s business to health. In addition, he started squealing early in 1948. Sarah Gainham wrote: “It became clear that we were in disfavour, and a Czech interpreter ‘blabbed’ to my husband that he and another correspondent had been denounced by Smolka as spies.” She continued: “It indicated a wish to please the new Czech government, and therefore the Russians who were the direct manipulators of the takeover”, and she concluded that Smolka’s concern to please the Russians was of much greater importance to him than his position with the British.

Smolka would have been more likely to confide in the state of the game directly with his sympathetic old acquaintance Graham Greene, and to give him the depressing news (for MI6, no doubt, since Greene would surely have found the whole business utterly entertaining) that the game was over – or that, in fact, the game had never even begun, since he had been working for the NKVD since 1933. And that illumination must have sent shock-waves and curses throughout MI6. Readers will recall the episode where George Kennedy Young reported that one of his assets had gone over to the other side, as well as the coldspur bulletin I submitted in November 2019 (https://coldspur.com/a-thanksgiving-round-up/ ) where I wrote of my frustrations dealing with the BBC in a report on a letter written by Eric Roberts: “The matter in question concerns an intelligence officer, Eric Roberts, who was informed in 1947 by Guy Liddell of suspicions about a senior MI6 officer’s being a Soviet mole, but was then apparently strongly discouraged from saying anything further in 1949, when he (Roberts) returned from an assignment in Vienna.” The disclosure of this artefact caused Christopher Andrew to react as follows: “It’s the most extraordinary intelligence document I’ve ever seen. It’s 14 pages long – it will keep conspiracy theorists going for another 14 years.” Yet Andrew refused to say any more, claiming loss of memory.

The 1947 suspicions were clearly about Philby (Smolka may have been a loose MI6 asset, but he was never a ‘senior officer’), but the follow-up strongly suggests that the ‘confession’ by Smolka led MI6 to review the connections between Smolka and Philby, having probably learned through Greene of the collaboration in the sewers of Vienna in 1934, and taken a fresh look at the evidence of their joint venture, The London Continental News. Guy Liddell must have known what was going on, and he had had access to all the documents that did not find their way into the Smolka PF. It is no surprise that Roberts was strongly discouraged from saying anything when he returned from his very fruitless stint in Vienna in 1949.

Czechoslovakia obviously plays a big part in this drama, but I do not yet interpret Greene’s unpremeditated move to Prague after his time in Vienna as necessarily linked to Smolka. MI6 received rumours of a coming Revolution in the capital, and it needed boots on the ground. Of course Greene would not want to boast of his work for MI6 in his memoir, but his sharp eye and his contacts would have made him a useful asset, and other commentators have fleshed out the story. Apart from the return by Greene to Vienna in June, where he met Smolka again, reportedly to discuss copyright arrangements, but probably to buy his silence, and square him off, there is little else from 1948 to add about the spy – except for one revealing last anecdote . . .

A letter to Irvine (now B1a) from MI6, dated July 5, 1948, informs him of a difference of opinion between the Czech Foreign Office and the Czech Ministry of Information as to whether Smolka should be granted a visa for Czechoslovakia. Klinger, head of the Foreign Office Press Department ‘is strongly opposed to it on the grounds that SMOLLETT is working for the American and other foreign intelligence sources’. It took an intervention by the Austrian Communist Party to have the visa granted. This follow-up includes the priceless explanation:

The grant of a visa was originally opposed by the Czech Foreign Office because SMOLLETT let it be known during his last visit that he was on a secret mission for the KPÖ. This story was checked by the Czechs and found to be without foundation. It was therefore assumed that SMOLLETT was using the story as cover for an intelligence mission for the Western Powers.

Smolka was clearly out of his depth, and he needed help. I recall the irony of Philby’s comment that Smolka would be ‘far too scared to become involved in anything really sinister’. But, for MI6, the 1948 Show was over.

Chapter 5: 1949-1951 – Evidence of Espionage

So what should the response of the Intelligence Services have been? After all, there was nothing illicit in an émigré’s applying for naturalization, pursuing a career in a British Ministry, providing propaganda for a wartime ally while not disguising his or her political sympathies, with the overall contribution being recognized via a medal. And the holder of a British passport would be entitled to travel wherever he or she wanted (indeed Smolka would not have been allowed to go to Prague and Vienna without one) in an accredited role as a newspaper correspondent. Yet anyone’s intensification of associations with communist organizations when the Cold War was hardening, and the apparent demonstration of a lack of commitment to returning to his or her adopted country, would naturally provoke questions. One of the statements that Smolka had to make in his naturalization request was to express an intention ‘to reside permanently within His Majesty’s dominions’. The Metropolitan Police report on him records: “He states that in the event of a certificate of naturalisation being granted to him he will make no effort to retain his Austrian citizenship”, and: “He wishes to become a naturalised British subject because he is not in sympathy with the present regime in Austria and desires to accept the responsibilities of a British subject.”

Those involved can be divided into two groups: those senior officers in MI5 and MI6 who had devised the plan to recruit Smolka as an asset for MI6, or to whom the plan had been confided, and those junior officers who had been left uninformed, and regarded the events more routinely. This latter group would have considered Smolka’s behaviour as an example of how not all those aliens who had come to the United Kingdom before the war, and had taken advantage of its hospitality, even becoming naturalized, were loyal admirers of its political system. The strange case of Georg Honigmann and Litzy Feabre would have been fresh in their minds. The former group would prefer that the whole matter be hushed up, since, even if Smolka had done something illegal (such as passing on confidential information), the last thing they wanted was for the whole messy business to come out in the open, and thus reveal their colossal misjudgments. (How could they have imagined that Smolka, with that résumé, would have been able to carry out a productive role as a spy on the communists in Vienna or Prague, for example?) As for the second group, they would have been professionally earnest in going over the evidence to detect whether the procedures had been followed, whether any oversights had been made, whether there were any clues to Smolka’s future behaviour that had been overlooked, and whether he had had any accomplices that they should investigate.

But Smolka was not going away. He kept both groups busy in the next few years.

MI6 kept Irvine of MI5 informed of Smolka’s recent moves. On 5 February, 1949, the anonymous officer wrote, based on information from the Vienna station, that Smolka was anxious to get a permanent visa for Czechoslovakia, ‘as he claims to have property there’, and Smolka hoped to be successful as he had good connections with Toman of the Ministry of Interior. Someone has written on the letter that Toman had been imprisoned by then, so maybe Smolka’s hopes were dashed. (A later annotation on file states that Smolka was put on the Czech blacklist on January 11.) Yet it sounds as if the Vienna station has another spy in the camp, since the letter next states:

Our representative has learnt from the same source that SMOLLETT’s connections with the Communist Party were not ‘overt’, because it was agreed that he was more useful in his capacity as ‘Times’ correspondent and preferred to remain incognito for that reason. At the same time it has been agreed in the Party that he should be given facilities equal to those of a Party member.

One would expect the Times not to be happy to receive this intelligence. Yet over a year passes before the next entry on file, when, on May 17, 1950, MI6 writes (this time to W. Oughton of B1a) that the French Sûreté has let them know that Smolka, described still as ‘correspondent of the Times newspaper in Vienna’, is said to be in touch with Soviet and Communist circles in Vienna. Not news, at all (as the writer admits), except that it shows the planned move to Czechoslovakia had not been successful. The writer shows his disdain, however. “But we have heard nothing of this creature since our letter to you of 5.2.49.”, he adds, and inquires whether Smolka is still the Times correspondent, and whether Oughton is still interested in him. It takes a while for the facts to emerge, but Norman Hinsworth (B4c) informs Morton Evans (B1a) that Smolka ceased working for the Times at the end of May 1949. So it appears the information was passed on.

It should be remembered that George Orwell had sent his list of ‘Crypto-Communists and Fellow Travellers’ to the Foreign Office’s Information Research Department on May 2, 1949, and Smolka was on this list. Orwell (correctly) believed that it was Smolka who had tried to prevent Animal Farm from being published. Orwell wrote to Celia Kirwan that same day: “. . . it isn’t a bad idea to have the people who are probably unreliable listed. If it had been done earlier it would have stopped people like Peter Smolka worming their way into important propaganda jobs where they were probably able to do us a lot of harm.” The Foreign Office and MI6 were probably not comfortable when they received this news. And fifty years later, Peter Davison (who compiled The Lost Orwell, in which Orwell’s denouncements appear), was ordered to apologize by influential members of the German Press, as well as by members of Smolka’s family, for repeating assertions made by Michael Shelden that Smolka was a traitor. Very sensibly, Davison refused.

By then, however, MI6’s view of Smolka was becoming less charitable. A letter to Oughton dated 20 June provides an update on Smolka’s activities in Vienna, primarily concerned with running his father’s button factory while staying in close contact with various Austrian communists and fellow-travellers. It goes on: “Subject still lives at Vienna XIII, Jagdschlossgasse 27, and suffers from severe diabetes. We wish DR. BANTING had not discovered insulin”, a sentiment that implicitly expresses a hope that a Soviet-style assassination squad would take care of this troublesome person. At this time, the British and US occupation forces were still in bitter conflict with the Soviet Union over the running of the country, and the management of the economy. The Marshall Plan was starting to take effect, Austria being the major beneficiary of that project. Smolka’s preferential treatment by the authorities in the Soviet zone, and his unique ability to run his own business, must have raised the hackles of those who had regarded him as an ally.

And then Smolka came to notice again because of the Peet affair. A few months ago (see https://coldspur.com/the-tales-of-honigmann/) I wrote about John Peet, and the way that Georg Honigmann had deputized for him in the Berlin press shortly before Peet defected to the Communists in 1950. Peet had been the Reuters correspondent in Vienna until 1946, when he transferred to a position with the agency in Berlin, and fled to the Eastern Zone in June 1950. British Military Intelligence in Austria became involved, and Sjt. J. W. Wardlaw-Simons reported that Peet’s predecessor in Vienna, a Mr. H. D. Harrison, had told him that Peet had always held extreme left-wing views, and had been ‘on intimate terms of friendship with the British Journalists SMOLLET and BURNS [sic]’, and asked whether he should approach ‘the subject’ directly.

The ‘subject’ was Mrs Christl Peet, née Guderus, who, shortly before her husband’s defection, had apparently returned to Vienna because of altercations with him. That Peet had foolishly fallen for Soviet propaganda is evident from an extract of a letter to her, where he wrote that he was now ‘on the side of the Peace-loving peoples of the World’. Wardlaw-Simons’ interview revealed little more about his relationship with Smolka and Burn. MI5 received the report in July, and then was sent a confidential memorandum on the Peet defection on October 18, when W. R. Hutton, assistant director of B.I.S. in Chicago, offered a long analysis.

What was B.I.S.? I had assumed it was ‘Berlin Intelligence Services’, but I was puzzled why that organization had an office in Chicago. And then Phil Tomaselli pointed me to the ‘British Intelligence Service’, which (as Wikipedia informs us) was a white-propaganda department of the Foreign Office established in 1941, and re-energized when the Ministry of Information was closed down at the end of the war. Hutton, who stated in his report that he had been in Chicago for about a year, had clearly been working in Vienna during the period in question, since he was intimately familiar with the players. Yet it occurred to me: had Smolka himself perhaps been transferred to BIS when the Ministry shut its doors, under cover as a journalist for the Daily Express?

Hutton described his role in Vienna as ‘information officer for the British element of the Allied Commission headquarters’. He expressed some surprise that both Reuters (in the person of Alfred Geiringer) and the British political adviser in Germany (Peter Tennant) had expressed unawareness of Peet’s political sympathies, since Peet’s fellow-journalists there in 1946 had no doubt that Peet was ‘a close “fellow-traveller”’, or even worse. Hutton identified an ‘unholy triumvirate of Peter Smollett (then DAILY EXPRESS), Michael Burn (LONDON TIMES) and John Peet (REUTERS)’. Hutton then added further incriminating details, including this remarkable passage:

When Michael Burn was moved to Hungary to await receipt of his Moscow visa (which never came – a great disappointment to him), he recommended Smolka for the London TIMES vacancy in Vienna, and despite the protests to the paper’s headquarters in London by legation and by independent British newspaper men, Smolka was appointed and continued as the TIMES correspondent until mid-1949. Though in ill health (Smolka suffers from glandular trouble), he combined this job, firstly, with that of assistant to Dr. Ernst Fischer when the latter was Communist foreign editor of the NEUES-OESTERREICH, triparty ‘independent’ paper. When Fischer, the only real brains of the K.P.O. was ousted, he went to work, it is believed, as the shadow foreign editor of the official Communist party paper. The pro-Communist news agency, TELE-PRESS, was apparently started by Smollett, and he is still a shareholder. On his ‘resignation’ from the LONDON TIMES (as a result of heavy pressure rather than the ‘illness’ which was announced), Smolka assumed managership of a button factory in the Soviet section of Vienna, formerly owned by his father-in-law [actually, ‘father’], and which, remarkably enough, he had managed to get released from Soviet control. He still maintains his interest with the Communist news agency, TELE-PRESS, and is allegedly writing books.

I take several lessons from this testimony. Smolka’s true allegiances seem to have been far more obvious to his journalist colleagues than they were to MI6, even back in 1946. The infamous Michael Burn (incidentally a one-time lover of Guy Burgess), who abetted Smolka’s career at the Times, had in fact been one of Smolka’s referees in his naturalization request, and MI5/MI6 had obviously been lax in not tracking this triad properly. Burn was a provocative character, but also a brave one, since he was captured during the St. Nazaire raid of March 1942. He published a biography in 2003, Turned Towards the Sun, that is predictably equivocal about his ideological sympathies. (He died in 2010, aged 97.) An intimate friend of Guy Burgess, he suggests that he was almost recruited by his lover to the Comintern cause, and he later got into some trouble for delivering Marxist lectures when in German prisoner-of-war camps. He claimed that he was never a communist, never a fellow-traveller, but admitted to having Communist Party ‘mentors’ in London after the war. At one point he writes that he wanted to get to Budapest early in 1948 simply to witness the trial of Cardinal Mindszenty, yet elsewhere describes his great disappointment in not gaining a visa to move to Moscow (as Hutton confirmed). He was in fact tipped off about the Mindszenty trial by Guy Burgess. In his book he makes only one brief mention of Smolka, when the latter attended a dinner in London at which the Austrian Ernst Fischer and his wife were present, which is disingenuous, to say the least.

Smolka was engaged in manifestly underhand and subversive work that could have been considered traitorous, and that could have called for his British citizenship to be revoked. His illness (of which much was made in successive years) may well have been a deceit: although apparently confined to a wheelchair soon afterwards, he survived until 1980. It all points to an unhealthy degree of toleration by MI6 for Smolka and his clique. Interestingly, a further provocative statement is made by Hutton on Antony Terry, whom he accuses of staying too close to Peet and Smolka, and of being influenced by them. Terry, who was ‘vehement in his declarations that he was not a Communist’, soon after received a firm defence from the Intelligence Organization of the Allied Commission. In his role handling agents under the aegis of the Vienna station, a certain amount of dissimulation on his part may however have been necessary.

Next came the highly charged and very critical year in British Intelligence history – 1951. In March, the analysts of the VENONA decryptions were closing in on Donald Maclean as the figure behind HOMER, the betrayer of secrets in Washington, and his identity was almost certain by the end of the month. Oliver Franks, the British Ambassador in Washington, informed Guy Burgess that he was seeking Foreign Office approval for his recall to London. Burgess returned at the end of March, and he and Maclean would abscond to Moscow on May 25. At some time during March, Smolka made a visit to the United Kingdom – but his arrival and departure were not noticed by the Immigration authorities.

The sole indication that is recorded is a series of intercepted telephone conversations between Smolka and someone identified as ANDREW, some of them undertaken in Russian. Who initiated the surveillance, and why, are not recorded, but D. Mumford of B1g receives a transcript of them, and wonders whether the Peter Smolka may be identical with the Smolka with whom MI5 is familiar with, and he makes a request that someone should check up whether the person was in the country on March 1. The outcome of that inquiry is not recorded, but on May 30, an investigation from British Military Intelligence in Austria is launched concerning a letter sent from a S. A. Barnett to Smolka, including information on biological warfare in China, and intercepted on February 1. James Robertson of MI5 asks his colleague in MI6 whether the service has any fresh news on Smolka, but receives the answer that there is nothing new in his file since June 20, 1950. Evelyn McBarnet of B2b agrees with her MI6 counterpart that ‘there is little doubt that he is a Communist’ – an assessment that would appear to be somewhat tentative and dilatory given the man’s track-record. On July 9, B1g is able to inform Military Intelligence in Vienna that Barnett is a biologist, a member of the Marylebone branch of the Communist Party, and a security risk.

It is evident that MI5 is trying to determine whether there were any links between Burgess and Smolka. MI6 in Vienna can find nothing. And then the bomb drops. The Minute Sheet to KV 2/4169 shows that Smolka, as early as August 21, 1951, had come to MI5’s notice in connection with the investigations by B1 & B2 into the Maclean/Burgess case. In November 1951, a trawl through correspondence found on Burgess’s abandoned premises reveals a sheaf of documents that were believed to have generated by Smolka. In an extraordinary pageant, seventy pages of these documents can be seen in Smolka’s third file, KV 2/4169: they have been copied from Burges’s unreleased file PF 604529. They merit a complete transcription, as they cover all manner of highly confidential topics, from notes made from Cabinet meetings, discussions of British strategy towards the Soviet Union, success of bombing raids, to details on armaments. They constitute an astonishing proof that Smolka was not merely an influential propagandist, but also acted as a genuine spy.

The introduction to the documents merits being reproduced in its entirety.

The enclosed documents, all of which were found in Guy BURGESS’s correspondence, are believed to have emanated from Peter SMOLKA @ SMOLLETT. They consist of: –

- Notes relating to R.A.F. bombing raids in SMOLLETT’s handwriting.

- Document describing conversations with various people. This document as typed on a machine with a faulty lower case “m” and has been annotated in SMOLLETT’s handwriting.

- A number of documents describing conversations with various people. All these documents typed on a machine with a faulty lower case “m”.

- Two documents similar in material and manner to III but typed on a different typewriter.

- Sample of SMOLLETT’s handwriting obtained from Ministry of Information File F.P. 8052/4.

This evidence is far stronger than the corollary claims on the typewriter technology made about Alger Hiss by Whittaker Chambers a couple of years earlier, after which Hiss was jailed for perjury. And the whole scenario shows how reluctant Smolka was to pass such documents to the new ambassador, Gusev, his predecessor and close friend Ivan Maisky having been recalled in August 1943. Smolka thus had to implicate the unreliable and undisciplined Burgess in his crimes, and rely on him to forward the information to their masters.

The first reaction by MI5 was to try to acquire a complete statement of Smolka’s immigration records. The request expresses the belief that Smolka may have visited the UK in March 1951, and follows with: “Discreetly obtain U.K. address and particulars of foreign visa and documents of interest and telephone arrival or departure to M.I.5.” The result was that Smolka was seen to have benefitted from a constant renewal of his passport: the original in 1938; a fresh one issued in Moscow on June 17, 1944; an exit permit to allow him to travel to Prague dated June 27, 1945; an application made that same day for a new passport tissued on July 5; a granting of a new passport by the Vienna consulate on July 30, 1947; and a further issuance on July 21, 1951. This last event is the most extraordinary of all, Smolka by then having reneged on his naturalization promises, and shown his utter opposition to British democracy, as well as a clear intent to reside permanently in Austria. What thought-processes did the authorities go through? After all, as his naturalization papers confirm, Section 23 of the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act, 1914, provides that:

If any person for any purposes of this Act knowingly makes any false representation or any statement false in a material particular, he shall in the United Kingdom be liable on summary conviction in respect of each offence to imprisonment with or without hard labour for any term not exceeding three months.

Maybe Smolka had reconsidered his ‘intention’ to reside permanently within His Majesty’s dominions, but he had omitted his early 1934 visit to Vienna when listing his various absences from the United Kingdom.

So what action did MI5 take on learning of this treachery? According to the archive, nothing. in October 1951, Martin had suggested that, should Smolka visit the UK again (as appears to be his practice) ‘we might wish to get in touch with him’. Indeed. It appears again that the lower-level officers in MI5 have not been brought fully into the picture. Yet an apparently harmless request may have caused greater soul-searching. On December 11, British Military Intelligence in Austria made a routine inquiry (on behalf of their US colleagues) about the activities of Smolka and another Austrian émigré, George Knepler, who had been staying at the Smolka domicile. It takes a while for MI5 to respond.

Chapter 6: 1952-1961 – Survivor and Diehard

On January 22, 1952, Arthur Martin, now B1g, wrote a report (heavily redacted in the archive) for British Military Intelligence in Austria. What remains of it is anodyne and stale. Five days beforehand, Martin’s colleague, R. V. Hodson, had recommended a cover-up of Smolka’s role with the Ministry of Information, as the allegations against him concerning his Communism might damage relations with the Americans. Martin notes that the FBI and the CIA have already started nosing around over Smolka, and that B2b has been in contact with them. The Americans can therefore not be fobbed off completely, and he recommends sending to the Intelligence Organisation Austria a sanitized version of his report to pass on to ‘the local American element’.