Contents:

Introduction

‘The Airmen Who Died Twice’

The coldspur Archive

Helen Fry’s ‘Women in Intelligence’ (2023)

The Darkrooms of Edith Tudor-Hart

‘Nothing Short of a Scandal!’

Guy Burgess at Kew

A Death in Nuremberg

Holiday Reading: Volodarsky et al.

Coldspur under stress

News from Academia

Similarity and Identity

* * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

Readers can probably imagine the flurry that takes place in the days just before the publication of the monthly coldspur. After I have submitted my copy, my team of fact-checkers goes over it, verifying names, dates, titles, and professional positions. Thelma, my lead grammarian and Sensitivity Reader, goes over my text with a toothcomb, looking for dangling participles and ensuring that the subjunctive mood is deployed properly, checking nounal and verbal agreements, and verifying that colons and semicolons have been used correctly. She also has an eye out for any offensive remarks I may have made concerning disadvantaged minorities. (She is not certain whether the category of ‘authorized historians’ comes under that rubric.) My Editor next reviews the overall style of my piece, and analyzes it for any opinions or assertions that may have legal implications: we discuss them, and make any necessary changes. Meanwhile, my Graphics Editor has been scouring the Web for suitable images to decorate my pallid prose. Lastly, cross-referenced urls have to be reconciled and verified, and the posting properly indexed for optimization by search engines. On the last day of the month, before breakfast my time, the piece goes into Production status, and eager readers, from Memphis to Murmansk, from Montevideo to Melbourne, can pick up their monthly fix.

Thus my absence in California at the end of June, accompanied by my wife and daughter to visit our son and his family, caused a fair measure of disruption at coldspur HQ. We did not return until the early morning of July 3, and the staff had to interrupt their Independence Day plans in order to meet the new deadline. I thank everyone for their sacrifices and noble efforts. Life will be so much easier when Conspirobot© takes over completely.

‘The Airmen Who Died Twice’

I was relieved to have completed writing the saga of the 1944 crash at Saupeset, and to be able to publish it, by the end of March. I have had several complimentary messages from coldspur readers around the world, and it has been my intent to drum up interest in the story in time for the eightieth anniversary of the incident in September of this year. I strongly believe that the relatives of the sacrificed airmen deserve a full explanation and apology from the Ministry of Defence. I also believe that my story is strong, and very defensible, with incontrovertible evidence about the impersonated airmen and their subsequent tragic deaths, even if the documentation behind the conspiracy is sadly missing. I also feel it is appropriate, among all the celebrations surrounding the liberation of 1944, that honest appraisals of mistakes be made as well. For example, several recent books have disclosed the massive French civilian casualties that were caused by RAF and USAAF bombing after the D-Day landings, in places like le Havre, and the manner in which such slaughter was given justification, in the context of the objective of destroying German units, is receiving fresh attention from historians.

One of the early converts to my story was Professor Torgrim Titlestad, who has a very special interest in Peter Furubotn, the Norwegian Communist who defied Stalin. He has spent a large amount of time in updating a biography of Furubotn, one first published in Norwegian in 1997, but not yet published in English (A synopsis of his life is available through his website at https://furubotnarkivene.no/en/about_peder_furubotn/index.html). The Professor believed that what I wrote shed fresh light on Furubotn’s career – and on his avoidance of an early grave. Moreover, he had a close connection with Furubotn, as his father had been Furubotn’s security officer in 1944, and had accompanied him in his escape from the Gestapo. If any academic were to be sceptical about theories of assassination plots via RAF aircraft, it would have been the Professor.

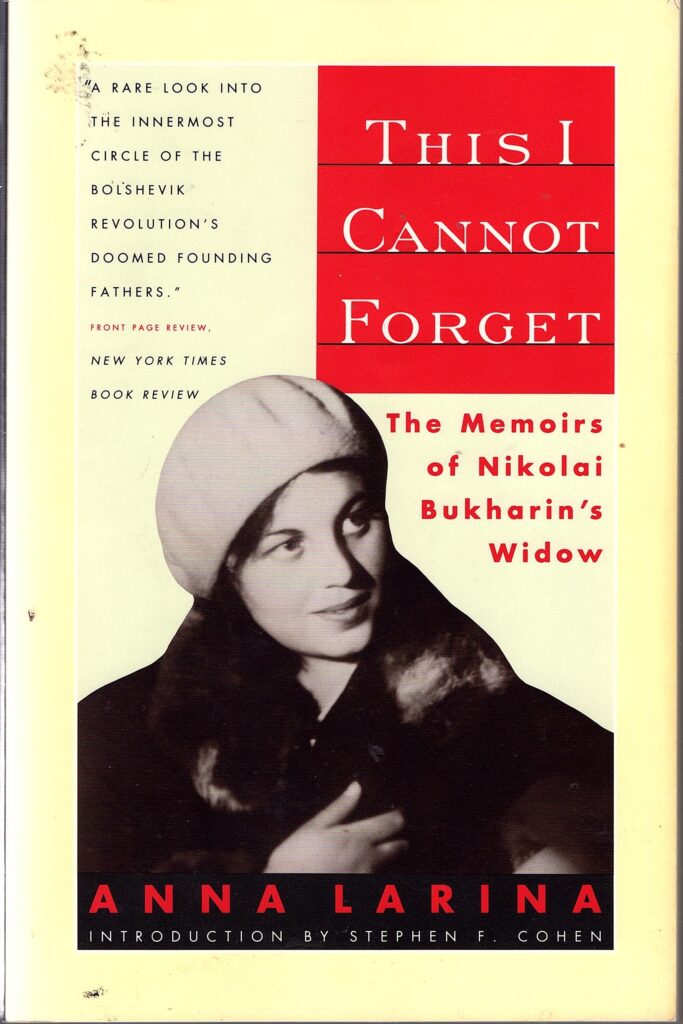

At one stage earlier this year, Professor Titlestad even invited me to speak on the subject at a conference in Oslo later this year. I jumped at the opportunity, and started planning possible speaking events in the United Kingdom to leverage my presence in Europe, believing that I had interesting stories on such as Philby and Smolka to relate, as well as the ‘Airmen’ saga. I very much enjoy public speaking, and dug out my passport to see if it needed renewing. The Professor even asked about my expenses, and how I thought they should be met. I responded promptly –and generously, I think – but then the Professor went quiet. I did not go begging to him to determine what happened, but am dismayed by his behaviour. I do not know whether a political dispute interfered with the invitation (the Norwegians are still at loggerheads over some aspects of the wartime resistance), or whether the Professor decided he did not care for my revisionist views of Furubotn. As the conclusion of my piece clearly states, I am dismissive of the Professor’s attempt to present Furubotn as some kind of ‘Eurocommunist’ liberal, and found the references to Bukharin ill-advised. In any event, I had to withdraw my preliminary approaches for other speaking events, which was very annoying.

I thus turned my attention to media outlets who I considered might be interested in the story. My on-line colleague Keith Ellison had kindly converted the web pages of the story into PDFs, so I now had a version I could distribute rather than simply referring addressees to coldspur. I saw two classes of outlet – a) institutions with some responsibility for, or ownership of, the case, and b) investigative journalists with a penchant for uncovering breakthrough stories. In the first category, I picked the Squadron 617 Association and the magazine RAF News (‘the official voice of the Royal Air Force’). Neither entity even acknowledged my email. As for the second, I wrote to Private Eye and the Mail on Sunday (who had used material by Anthony Glees and me on Sonia a few years ago). Again, neither even acknowledged my message.

I had to change tack, obviously, and approach individual names. Having exchanged emails with the historian Andrew Roberts a few years ago (before he became Baron Roberts of Belgravia), I had joined his distribution list for updates on his new books. I thus tried to invoke his help. He responded very promptly, said the domain was however outside his sphere of interest, but immediately copied in a journalist at the Daily Mail, one Andrew Yates. I never heard back from him, either. I contacted a couple of historians with whom I had become acquainted via the SOE chat-site: they were both very enthusiastic about my research, but they could not offer any leads to further promotion. At about this time (early May) I also reached out to the journalist Mark Hollingsworth, with whom I had created a friendly rapport after I had reviewed his book Agents of Influence on coldspur.

Mark was very supportive (he was impressed with my research on Smolka), and he suggested that I create a synopsis of the material, in order to enable easier assimilation of the rather complicated story, and that I contact historians and journalists with expertise or interest in the war in Norway. I thus boiled the story down to 2000 words (see https://coldspur.com/the-airmen-who-died-twice-synopsis/) , and prepared to search out a list of likely candidates. I disagreed, however, with part of Mark’s guidance. He felt that no journalist or historian would touch the story without documentary evidence of the major plank in the story – that Churchill and Stalin must have exchanged messages of some kind in order for the flight and impersonations to have occurred. As my conclusion boldly stated, I felt it extremely unlikely that anything would appear, given the extraordinary circumstances of the enterprise. I could quickly list multiple events from World War II that have been discussed in serious terms when primary documentary material was not available. The authorized historians Foot, Hinsley and Andrew had all made categorical statements about events that had no documentary back-up. There were enough established facts about the case to warrant its broader promulgation. Besides, everyone likes an aspect of mystery. So I continued.

I picked out the names of six prominent historians whose books related to the subject I had read: Tony Insall, Ian Herrington, Richard Petrow, Patrick Salmon, Olivier Wieworka, and Max Hastings. Sadly, Petrow has died. I then tried to find email addresses for them, but such figures normally hide behind their agents and publishers. Apart from Insall, this was the case, so I had to craft individualized messages to those who represented them, asking for my package of synopsis and PDFs, with a brief explanation of what I was trying to achieve, to be forwarded to the relevant author. That was on May 16. The same day I made a separate approach to the Chairman of the Squadron 617 Association. Soon after, I sent personalized emails to journalists Ben Macintyre (of the Times), and Ben Lazarus (of the Spectator), both of whom I had exchanged messages with – concerning Sonia, of course – a few years ago, and suggested that they might be interested in promulgating the story. I never heard back from either of them. At the end of the month I posted a piece on FaceBook that drew attention to the new Synopsis now available on coldspur.

And then, at the end of May, I had two glimmers of light. None of the other historians responded to my approach, but Professor Patrick Salmon, who had edited Britain & Norway in the Second World War, published almost thirty years ago, responded with interest. He regretted that he was no longer close to Norwegian affairs, but he would try to help. He is now Chief Historian at the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, which sounds like an influential position. Shortly afterwards, I received a long email from Dr. Robert Owen, Official Historian, 617 Squadron Association, to whom my message had been routed. A few days later I responded in kind, with a polite and thorough analysis of his points. The outcome was, however, tremendously disappointing. I felt that our communications deserved greater publicity, and I accordingly posted the exchange as a Special Bulletin on coldspur on June 11 (see https://coldspur.com/the-617-squadron-association-historian/).

Professor Salmon, meanwhile, has continued to be very helpful. He recommended that I contact the Air Historical Branch of the RAF, and make a request for the Casualty File for Flight PB416 under the Freedom of Information Act. This I performed on June 13: Professor Salmon told me that the Branch has to provide a reply within twenty business days. On June 15, I received a confirmation of my request, and an indication that I should receive a reply by July 15. On the other hand, disappointments still occur. Mark Hollingsworth recommended that I contact a prominent historian of RAF matters, Paul Beaver. Through his publisher, I made contact, and he responded promptly, and with apparent interest in my story. After ten days, I had heard nothing, so I emailed him again, and he disappointingly wrote that he had been too busy to read it . . . And Nigel Austin, the man who initiated this whole project because he had a relative who was killed in the crash, expressed great enthusiasm when I completed the project, and vowed to promote the story. Yet he has now disappeared from the scene, and no longer responds to my emails.

I am finding this tepid response not only demoralizing, but also a little eerie. As one of my coldspur colleagues wrote to me, my story would make a great documentary. It has everything: mystery, disaster and tragedy, war, Nazism and communism, institutional confusion and cover-up – as well as a very timely anniversary. Yet several experts do not even show any interest in its potential or topicality, let alone engage in debate to challenge my hypothesis. It is almost as if a celestial D-Notice has been placed on my research. My mission at coldspur has been to reveal when government institutions – in my domain of interest, primarily MI5, MI6, the Home Office and the Foreign Office – have covered up the facts out of a desire to protect themselves, in the belief that the British public cannot be trusted to know the truth. Thus my investigations into (for example) the concealment of knowledge over Klaus Fuchs, the cover-up over Kim Philby, the refusal to divulge the clumsy attempt to manipulate Agent Sonia, the colossal mis-steps over Peter Smolka, the censorship of activities behind the demise of the PROSPER network, and the improper release of rumours to journalists to discredit officers like Hollis were all prelude to my research into the shenanigans with the disaster of PB416.

In the past few months there have been resounding echoes of such governmental misbehaviour in the willful mishandling of the Post Office HORIZON project, the revelations concerning the tainted blood fiascos of the 1970s (of which my sister was a victim, I believe), and, very recently, the investigation into the cover-up of Nazi crimes on Alderney. Not solely in the world of intelligence and military history are the issues too important to be left to the authorized and official historians to analyze and report on, and I shall continue to plough my furrow without concerning myself about upsetting anybody in authority, or the repercussions therefrom.

The coldspur Archive

As I reported a few months ago, I successfully arranged a home for my library of books and archival material (see the press release from the University of North Carolina, Wilmington at https://giving.uncw.edu/stories/new-special-collection-to-make-randall-library-a-destination-for-researchers-worldwide.). This is an important agreement, since it relieves me of the distress of fearing that my collection might be dispersed or even destroyed when I go to meet the Great Archivist in the Sky. (By the way, I shall not ‘pass’: I shall die.) I believe the value of the complete set, and its availability for researchers from near and far, greatly exceed the usefulness of the individual volumes. I suspect that, as an assemblage of books on intelligence and twentieth-century history and literature, primarily British but also American, it may be unmatched by even the most learned institutions. The University, as part of our deal, has committed to providing administrative support to catalog properly the whole collection, and to provide enhanced capabilities for an electronic portal to all my coldspur research, and the documents and systems that have supported it, such as my epic 400-page Chronology (my Crown Jewels and secret sauce), and notes made on a vast number of books and archival material.

The transfer of books will probably start at the end of this year. This will be a wrench, as I dread the idea of losing direct access to all the volumes that I have become accustomed to exploiting each time I create a coldspur posting. The Library at UNCW is about forty miles away, so I shall have to plan my visits very carefully if I am going to continue with my conventional research. I suspect, however, that I shall have to cut back the depth of my investigations, and gradually wind down to a more routine and less dramatic series of postings. Thus I shall spend the remainder of this year reviewing what important commitments I still have, and identifying what files I have on my desktop that have not been processed properly. I also have a lot of work to do in cleaning up electronic files and references, as well as documenting carefully the various paper items (letters, printed reports, sets of old magazines, many of which contain important articles, clippings, etc.) that will constitute an important part of the archive.

Meanwhile, the project to register all the books continues. Every Sunday morning I allocate a couple of hours to entering another hundred items on LibraryThing. I am now approaching 5,000 volumes recorded in my private on-line library, with a lot still to be processed. This can be an easy task, if the book contains an accurate ISBN, but the older volumes require some digging around to find the correct year and publisher, and some of the more antique items have to be entered completely manually. It has turned out to be a revelatory exercise, in which I have encountered books I had forgotten about – or even lost. (Some have been retrieved from obscure niches, having fallen down behind others.) There have been some duplicates, some deliberate, as I had purchased newer editions, but others by mistake, such as when I had acquired an item in a second-hand book-shop, and did not recall that I owned it already. Some I bought because the title was different – as often happens when a publication appears under a different name when it is released in the USA.

And there have been several interesting finds. Titles that I only skimmed, and shall probably never read cover to cover. (I am sure no other bibliophile has this problem.) Some classics that I should have read years ago: I think that, in my declining years, I would prefer to re-read Raymond Chandler or Kingsley Amis than tackle Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. And all those Trollopes! I enjoy him, but they simply take too long. Items that I had carelessly overlooked, and should have read long ago, such as E. P. Thompson’s account of his brother Frank’s death in Bulgaria on an SOE mission – which oversight was remedied last month. A few gems revealed, such as a very old guide to Oxford bequeathed to me by my father, in which he has written ‘1775?’ in the margin. And a few books that I had thought lost, such as the paperback of Raymond Williams’s Keywords, which I had been searching for a few months back. (It had been woefully misplaced in the Travel and Mountaineering section: members of staff have received a reprimand.) This had been a useful, though very earnest and cautious, guide for me back in the late 1970s, and had comprehensive entries on such concepts as ‘Class’, ‘Progressive’, ‘Status’, and ‘Imperialism’ (but not ‘Colonialism’). But it had no room for ‘Equity’, ‘Diversity’, ‘Inclusion’, ‘Identity’, or even ‘Populism’, ‘Race’ or ‘Ethnicity’– let alone ‘Intersectionality’! How did we manage to interpret social trends accurately and engage in intelligent discourse in those days, I wonder? [I was not aware that you tried, coldspur. I thought you were too busy playing cricket and having a thrilling social life. Ed.]

Helen Fry’s ‘Women in Intelligence’ (2023)

I did not have high hopes with this book, published last year, as I have found Fry’s approach to writing history lacking in discernible method and suffering from a very sloppy style. Yet I considered this item a necessary part of my reading agenda. As it turned out, I was pleasantly surprised in some ways. Fry has performed her usual diligent research, reveals a host of new facts, and someone has obviously given her some guidance on how to write more crisply and less elliptically. (In one of the blurbs, Kate Vigurs writes that ‘all is told in her usual inimitable style’. It occurred to me that the comment might not have been intended as a compliment, but I shall instead conclude that perhaps Ms. Vigurs has not been paying close attention.) I must question the whole endeavour, however: while it is important that the contributions from women be given their proper credit (as Jackson Lamb said somewhere: “You won’t find a more ardent feminist than me”), a description of exercises and operations that focuses almost exclusively on the achievements of the fair sex [is that expression still allowed, Thelma?] will be bound to distort the picture.

And so it turns out. Fry offers no explanation of how she approached the subject, or how she made her choices. (She mercifully does not engage in a debate about what ‘woman’ means in this decade, and how that term should be applied retrospectively to simpler days.) The blurb on the cover merely states: ‘The first full history of women in British intelligence across two world wars’. In many aspects, Fry’s work is a remarkable achievement. She has excavated some fascinating stories about women in the various intelligence services that had evaded this particular reader, and we should be very grateful to her. Unfortunately, the text reveals itself as a rather relentless catalogue of female success, and frequently distorts the broader picture, and misrepresents the facts. Along the way, a vast amount of familiar material has to be regurgitated to give the unwary reader context. Moreover, there is little room for records of failure, as one glorious contribution follows another. We are told, for instance (p 265) that ‘Hodgson and Holmes were the “brains” behind all operations into Austria, Yugoslavia and Hungary’, and (p 272) that ‘women such as Holmes, Stamper and Hodgson were the driving-force behind SOE’s success’, yet the incursions into those countries were largely disasters, and the unqualified trumpeting of SOE’s success when it clearly made a large number of mistakes does not contribute to valid and objective scholarship. Fry is also a little too trusting of what Vera Atkins’s personal file states.

Moreover, the history is not ‘full’, or consistently accurate. The author is strangely errant over the career of one of the most impressive of intelligence officers, Kathleen (Jane) Sissmore, who married John Archer (of MI5’s RAF liaison, a fact she does not mention) on the eve of the war. She mistakenly says that Archer was killed in 1943: it was his son who perished. Fry claims that Archer was fired because of her disrespectful comments on the previous MI5 director, Vernon Kell, when it was the acting director Jasper Harker who had been the subject of her derision. She overlooks Archer’s transfer to lead the group of Regional Security Liaison Officers, which task she performed very creditably for several months in the summer of 1940, and she suddenly places her with Philby’s counter-intelligence group in MI6. Archer did indeed move to MI6, but did not work for Philby until his new section was created in 1944. Fry says nothing about Archer’s subsequent return to MI5 at the end of the war, and what projects she was involved with, although the archives mention her occasionally. Nevertheless, Fry is confident enough to assert that Archer ‘would have made a brilliant director-general of MI5’.

And there are some notable omissions and mistakes. Fry writes nothing about the highly important Freya Stark, or Ann (Nancy) Lambton, who both played important roles in propaganda and intelligence-gathering in the Middle East. Since Fry does include a section on post-war activities, one might have expected her to mention MI5’s Evelyn McBarnet, who played a prominent part in the molehunts of the 1960s and 1970s, and had earlier worked on the Robinson papers of the Red Orchestra. (Peter Wright wrote that she had had many years more experience in counter-espionage than he or Arthur Martin, which suggests she was active in the war years.) Fry also neglects Anne Last (actually ‘Glass’), who had a very significant career in MI5, having joined in May 1940, and who later married Charles Elwell, an MI5 officer. Fry’s sketch of Joan Miller fails to mention a vitally significant episode of her career, when she detected the Major (probably but not incontrovertibly Leo Long) stealing information and passing notes to his communist contact in 1944. Ray Milne, the communist agent inside MI6, who was detected and forced to resign, is overlooked (perhaps because she was a baddie).

(I should also mention that, in the September 2023 issue of Magna, the Magazine of the Friends of the National Archives, appears an article by Phil Tomaselli, titled ‘MI5 women spies during WW2’. It is not a very accurate title, since MI5’s charter was counter-espionage rather than espionage – although it did maintain ‘agents’ who spied on subversive groups – and much of Tomaselli’s text is taken up by women who served during World War I. Nevertheless, Tomaselli lists a number of names who should be added to the roster, including Mary George, and Hilda Matheson of the Joint Broadcasting Committee.)

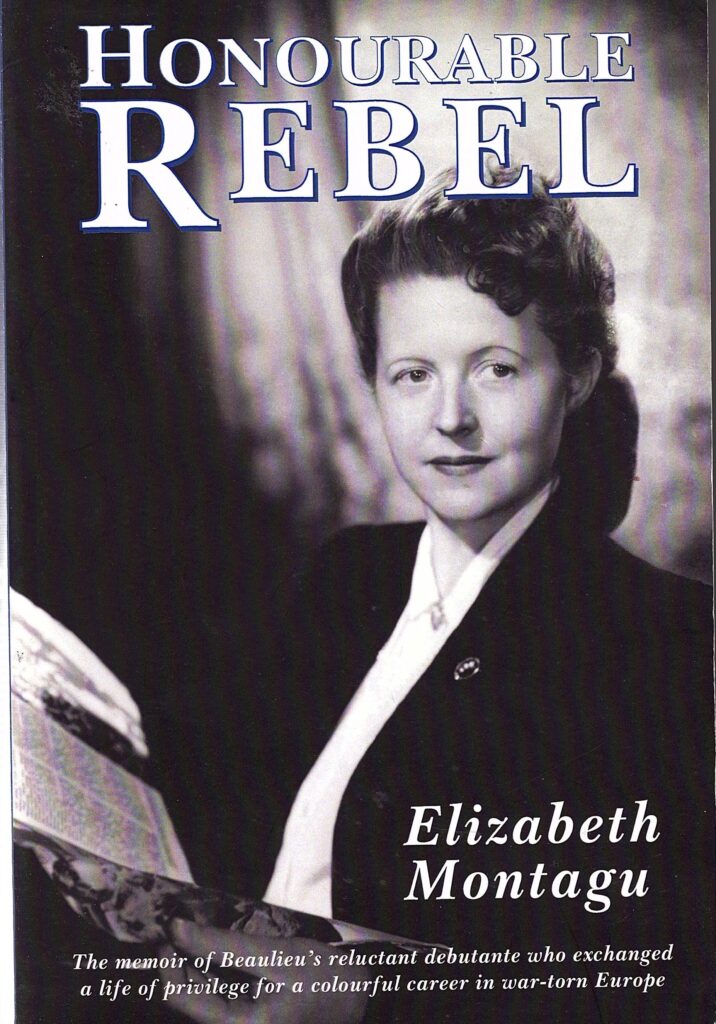

Fry briefly covers the five years that the highly dubious Tess Rothschild (née Mayor) worked in B18, the anti-sabotage section of MI5, but she presents a very odd interpretation of MI5’s suspicions of her after the Blunt confession. The failure to recognize the important pair of MI6 agents in Bern in WWII, Elizabeth Wiskemann and her sidekick Elizabeth Montagu (aka Scott-Montagu), is particularly egregious. Wiskemann received a prominent biographical treatment by Geoffrey Field last year (see https://academic.oup.com/book/44709/chapter-abstract/378977699?redirectedFrom=fulltext), and I have referred to Montagu in my writings on Smolka. The novelists Sarah Gainham, married to MI6’s Antony Terry, and Helen MacInness, married to another MI6 officer, Gilbert Highet, should perhaps have been covered as well, to give some variety and useful perspective. Of course there were some other notable British subjects, naturalized through marriage, working in intelligence such as Ursula Beurton, Edith Tudor-Hart, and Litzi Philby aka Feabre – and at least two native-born, Jenifer Hart, married to the MI5 officer Herbert Hart, and Melita Norwood – but since they were communist agents working against the interests of the United Kingdom they presumably fell outside her purview. Nevertheless, Nigel West returns the compliment that Fry recently granted him on his recent book: “A fascinating, minutely researched study of women in the espionage business.”

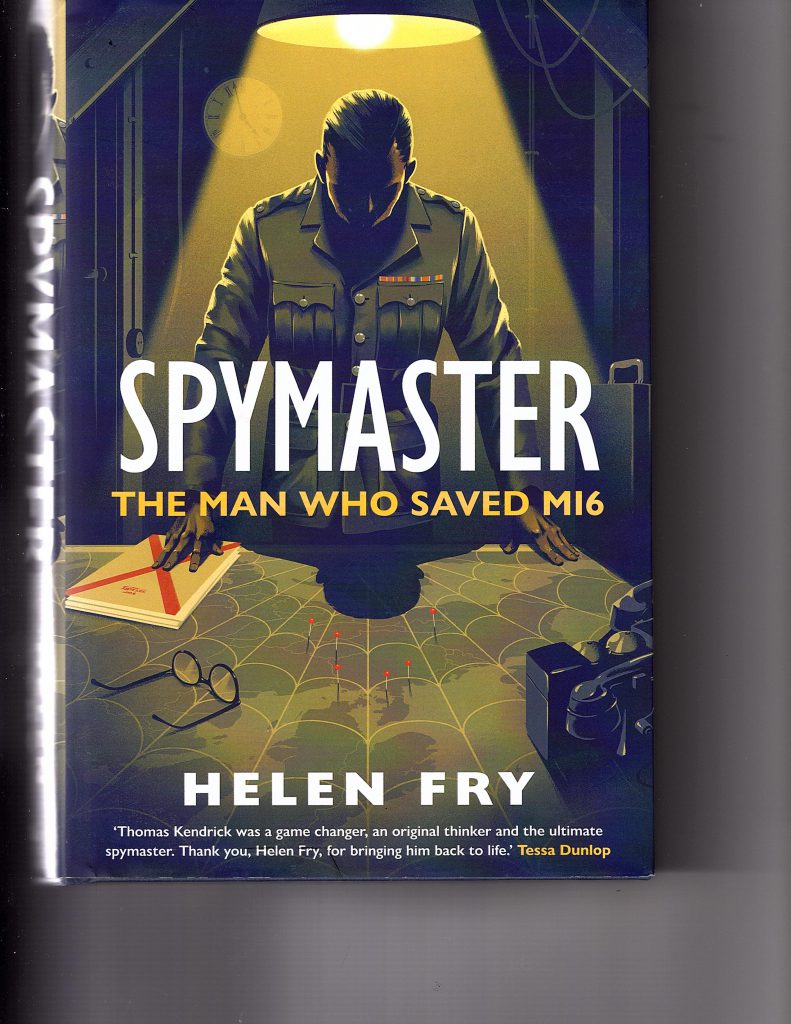

Thus the reader has to wade through a lot of extraneous material to pick out some splendid nuggets about meritorious heroines whose careers have very creditably been brought to light at last. The relentless feminist propaganda begins to chafe. Moreover, Fry can be both very risk-averse and highly provocative. At critical points, she steps back from providing any analysis of controversial incidents. For example, in wrapping up her section on SOE, she writes: “Exactly why Buckmaster and Atkins continued to send their agents into Europe remains the subject of debate.” That is a very cautious insertion that screams out for a more incisive inspection, and invites an examination of the dynamics of the situation, and whether there was any male-female dimension to the disastrous decisions that were made by the managers of F Section. On the other hand (as I pointed out in last month’s bulletin), she can lob a grenade over the parapet, as she does when she gratuitously reports (p 92) that, in 1933, the MI6 head of station in Vienna, Thomas Kendrick, alongside his agents and secretaries was tracking the movements of communist spies and activists ‘through journalists like Eric Gedye and a young graduate, Kim Philby’. This is a much more assertive and provocative statement than she allowed herself in Spymaster, and represents the claim that brought my female academic contact into apoplexy when I mentioned it to her a couple of months ago. So what say you, Westy? Did you spot that?

Because of the repetition, and the lack of valuable new insights, the volume should in my opinion have been better compiled as a biographical dictionary rather than a conventional narrative. It would in that way have been more usable, more concise, and more easily maintained. New histories of SOE, for example – focussing on country campaigns, rather than conventional broad-brushed approaches – are certainly desirable, and in such works the successes and failures of men and women should be clearly explained, as opposed to the romanticized and gung-ho narratives that are so frequently found. I entered in last month’s Commonplace collection what I considered a pertinent observation by a woman called Imogen West-Knights: “Perhaps I am letting feminism down to say it, but just because a group of women organised something, this does not mean that the organisation of that thing is naturally interesting.” Indeed. There should be no ‘feminist’ history – just history that gives comprehensive credit to the contributions of women and men equally.

The Darkrooms of Edith Tudor-Hart

I have always been prepared to admit to erroneous analysis and faulty conclusions displayed in my research. As Keith Ellison has pointed out to me, the Major observed by Joan Miller secreting notes may not have been Leo Long, as I claimed in Misdefending the Realm, and one of these days I am going to have to return to the records to verify the place, the time, and the institution, in order to confirm what was going on. Likewise with Edith Tudor-Hart: I have constantly expressed my amazement that such a transparently subversive, neurotic and muddle-headed woman could have played a major role in Soviet espionage, and I have treated Anthony Blunt’s claim that she was ‘the grandmother of us all’ (when she was in fact born a year later than the art historian) as a sour joke designed to disguise someone else. (Of course, similar doubts and objections were raised over the outrageous Guy Burgess.) And yet the attention swells, what with Charlotte Philby’s very bizarre Edith and Kim, and Edith’s great-nephew (or second-cousin once-removed) Peter Stephan Jungk contributing a biography in German, Die Dunklekammern der Edith Tudor-Hart (2015), which reinforces the myth that she not only led a parallel life to Kim Philby, but was as significant as he was, and that it was really she who was astute enough to identify Philby as a worthy candidate for Soviet Intelligence, and introduce him to Arnold Deutsch. I recently read Jungk’s book very carefully.

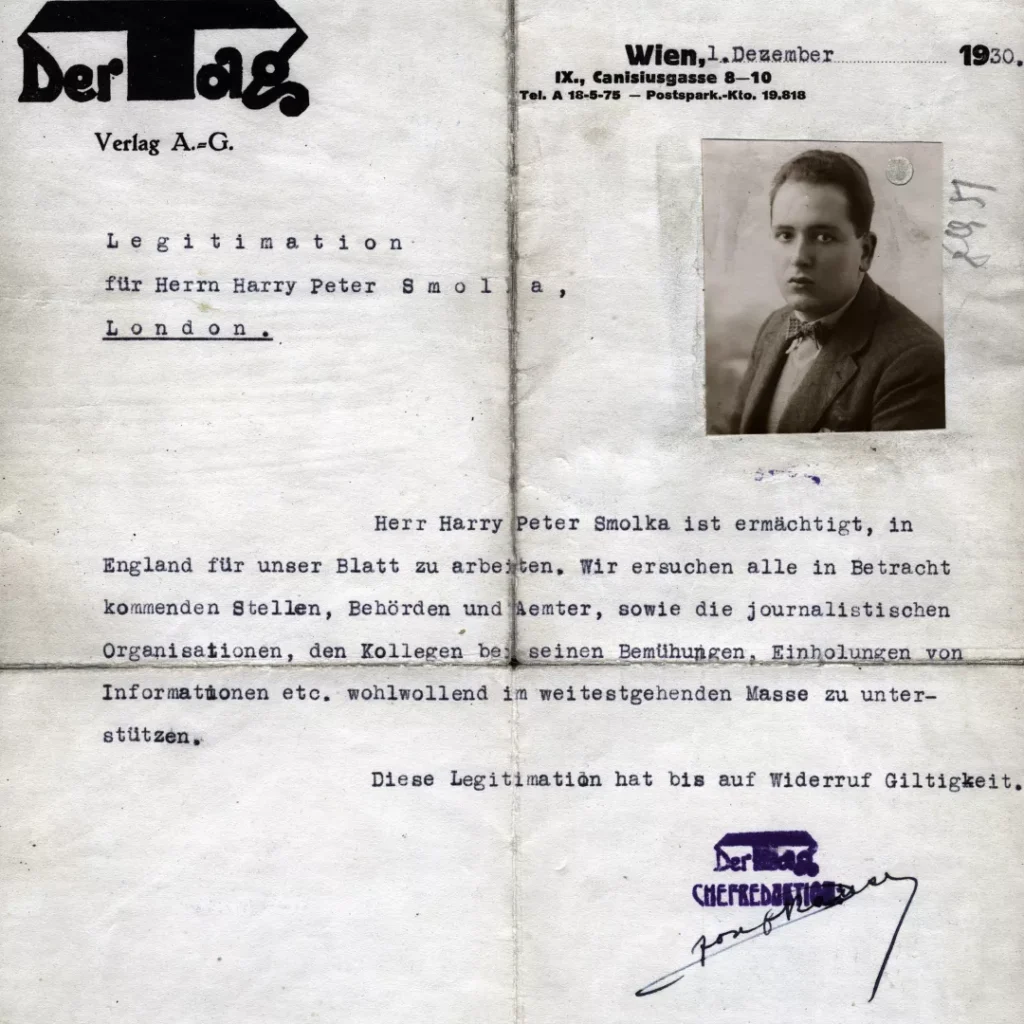

Thus I continue to inspect the evidence to check whether I am wrong. (Care is need when treating sources such as Wikipedia and Spartacus, which are very cavalier with dates, and the accounts of Tudor-Hart’s activity in Deadly Illusions and The Crown Jewels, both of which boast Oleg Tsarev as a contributing author, are so riddled with errors, contradictions and anomalies than I am inclined to treat them as disinformation.) What I find extraordinary is that MI5 opened a file on her (as Edith Suschitzky) in 1930, when she was noticed mixing with known communists at a demonstration in Trafalgar Square, and she was expelled from the country. From Vienna, she immediately wrote to Tudor-Hart, asking him to testify that she was a solid communist, as the local cadres mistrusted her! Thus, while the evidence undermined any official authority she might have had, she stupidly drew attention to her subversive objectives.

MI5 (and MI6, when she was in Austria) thereafter kept a close watch on her for over twenty years. She was known to be a communist, she married her lover Alexander Tudor-Hart in Vienna in August 1933 when she got into trouble with the law there, and consequently was able to flee to Britain as a subject through her marriage. She was allowed to have her mother join her in 1937 (her father having committed suicide). In 1938, she was interrogated by MI5 over her undeniable involvement in the Percy Glading case, since a receipt for her Leica camera had been found on Glading’s premises, but the authorities did nothing. Despite the constant surveillance, she was allowed to continue her associations with subversive groups in exile unhindered. MI5 devoted an enormous amount of time tracking her activities – all to no avail. Perhaps it was because they thought that she would lead them to bigger and more dangerous fish, but maybe, since they could not haul her in on any charge, they just wanted her to know that she was under constant watch, in order to frighten her. Yet they overlooked some of her most obvious activities, such as her affair with Engelbert Broda, the atom spy, and her role as a courier.

Yet the burning question remains: Why would the NKVD entrust any clandestine role to a person who so obviously was a communist agitator? She was expelled by the British early in 1931 for that reason. From Vienna she appealed for help from her lover to confirm her communist credentials, she was imprisoned for suspected subversive activity in May 1933 (when another lover Arpad Haasz, left the country in a hurry), and Tudor-Hart, who had at last divorced his wife, arranged their marriage in August 1933 so that she could escape to the UK. Agents of the NKVD normally took instructions from their bosses concerning their marital arrangements, but, if the agency had serious plans for Edith, it surely would have forced her to provide a better cover story than this, and it would have been very wary about the British authorities’ picking up where they left off when Edith had been banished in 1931.

And, indeed, her romantic entanglements were a mess. The management of her affairs tended to be clumsy, and she was often mistreated and manipulated by the men in her life. She fell in love with Arnold Deutsch in the late 1920s, but his girl-friend Josefina, absent from Vienna for much of the time, discovered her love-letters to him, and Deutsch soon married ‘Fini’ in 1929, and then left with her for Moscow. Jungk says that Edith had several other meaningless affairs during this time. When she returned to England, she picked up with the still married Tudor-Hart. After her expulsion to Vienna, she took up with Arpad Haasz, a fellow-conspirator, who fled when the going got hot. After Edith’s marriage to Alexander, he mistreated her, and abandoned her and her young son when he went to work as a doctor helping the Republicans in Spain. During the war, she developed a relationship with Engelbert Broda, but he also left her, in 1945, telling her that he was going back to Austria to marry his girl-friend (a decade older), from whom he soon separated. Edith then fell in love with the psychiatrist, Dr. Donald Winnicott, who was treating her severely autistic son, and they had a very unprofessional relationship. But Winnicott would not leave his wife, and tired of Edith’s clinginess. Edith developed a crush on the architect Baron Holford of Kemp Town, but he had to reprimand her in writing for stalking him.

I shall be writing further when I have completed a deeper analysis of her files, and the stories built around her, but here I simply want to mention two items that caught my eye recently. In his 2012 profile of Philby, Young Kim, Edward Harrison made a very shrewd observation over some text in a letter (in German) that he found in Edith’s file, sent to Tudor-Hart on June 22, 1933, and intercepted by Special Branch. It makes a reference to students at Cambridge, and the need to convert intellectuals to the cause, and asks the question: ‘What is M.D. doing?’. At the time, Special Branch interpreted ‘M.D.’ as referring to Alison Macbeth, who was a doctor, and then married to Tudor-Hart. It was not until December 1951 (in the heat of the Burgess-Maclean-Philby investigations) that MI5 went over the passage again, and decided that ‘M.D.’ stood for Maurice Dobb. So Edith had been acquainted with Philby’s tutor at Cambridge.

This should perhaps not have come as any surprise, since Dobb had written to Alexander Tudor-Hart in December 1930, in dismay, offering sympathy at the detention of Edith after the Trafalgar Square incident, and the subsequent report of her expulsion order. (All letters to Tudor-Hart were being intercepted.) Thus an immediate link between Soviet conspiracy, and the planned contributions of a Cambridge academic, are visible three years before Philby was sent on his way to Paris/Vienna by Dobb. And there is even an attempt by Edith to mask Dobb’s identity – a successful one, of course. What had the three of them discussed, one wonders? Tudor-Hart was a contemporary of Dobb’s, and both had studied under Keynes at Cambridge, so they were natural communist allies. Tudor-Hart had also studied orthopaedics in Vienna in the 1920s, so may have encountered Edith there. 1930 would obviously have been an early date for Philby’s potential to have been recognized (he did not enter the university until October 1929), but Dobb’s interactions with Edith are undeniable.

The other item of interest to me is Edith’s exposure to Philby, and her supposed role in recommending him to her former lover, Deutsch, in May 1934. I find it difficult to pin down the exact relevant dates of the early autumn of 1933, as even Jungk’s account is vague, but the other accounts (which claim to be based on KGB archives) are divided as to whether Edith became impressed with Philby’s potential when she knew him in Vienna, or whether she came to that conclusion when her friend Litzy introduced her to him in May 1934, soon after the Philbys arrived in London. Jungk first tells us that Edith married Alexander on August 16, and that they left for the UK a few weeks later. Yet, later in his book, he informs us that, on her release one month after her imprisonment in May, she went immediately to the apartment of her best friend, Litzy Friedmann, and discovered that Litzy had a lodger named ‘Kim’, who had been there just a few days. This is, of course, nonsense, as Kim did not arrive in Vienna until late August, at the earliest. Moreover, The Crown Jewels asserts that Edith’s famous photograph of the pipe-smoking Philby was taken in Vienna during those precious few days before she left with her new bridegroom, while Jungk asserts that it was taken in Hampstead the day after Philby met Arnold Deutsch in Regent’s Park. It is all an inglorious muddle.

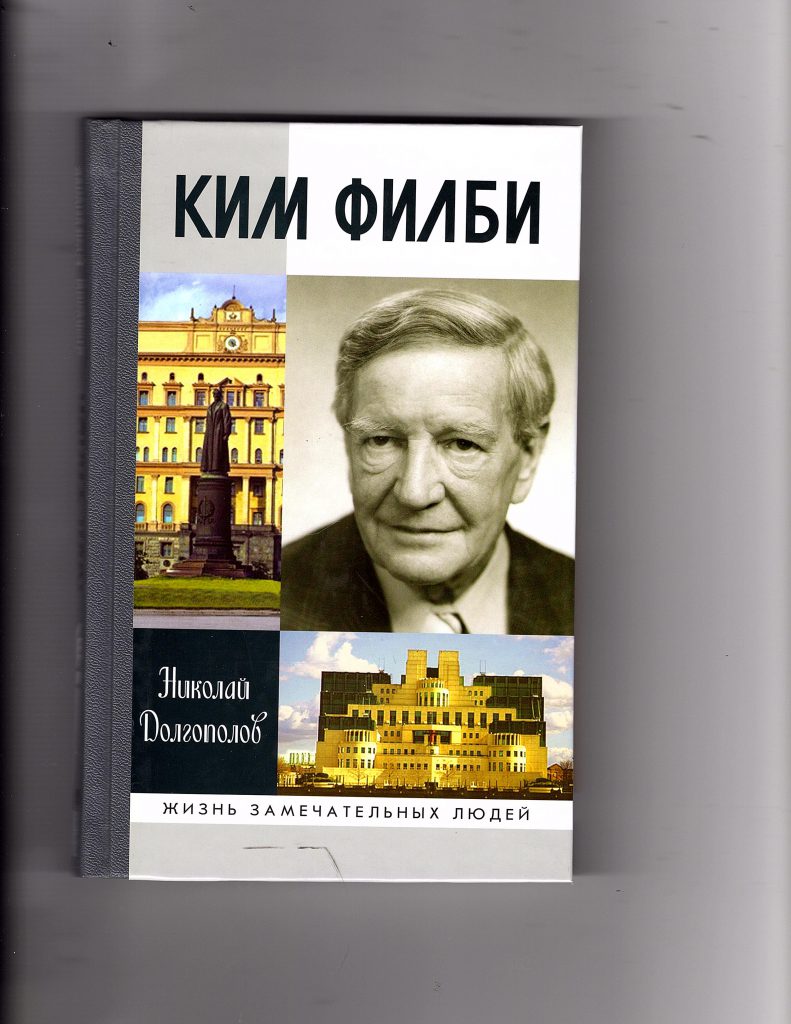

The irony is that Jungk, in his eagerness to find out the truth about Edith, went to Moscow in the 1990s, and tried to chase down historians and archivists to let him see the secret files on her. He was devastated when the officials (including Dolgopolov, the biographer of Philby) directed him solely to Deadly Illusions and Borovik’s Philby Files. Whether they had more which they were not prepared to reveal cannot be determined. But the implication is that the mess that has accumulated and been carelessly echoed over the decades in the western media may be all that there is. There are too many competing narratives tripping over each other, of which I have shown here only a sample. I shall explore all the paradoxes and conflicts of 1933 and 1934 in my end-of-July posting.

‘Nothing Short of a Scandal!’

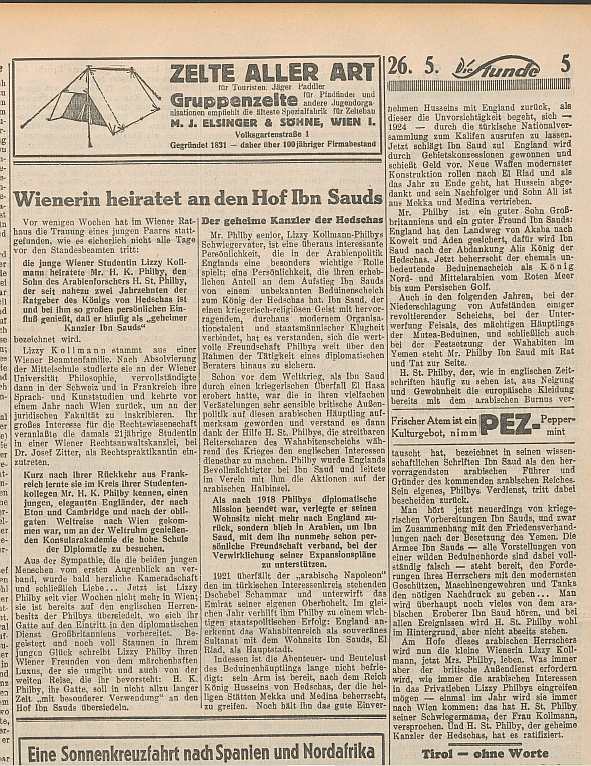

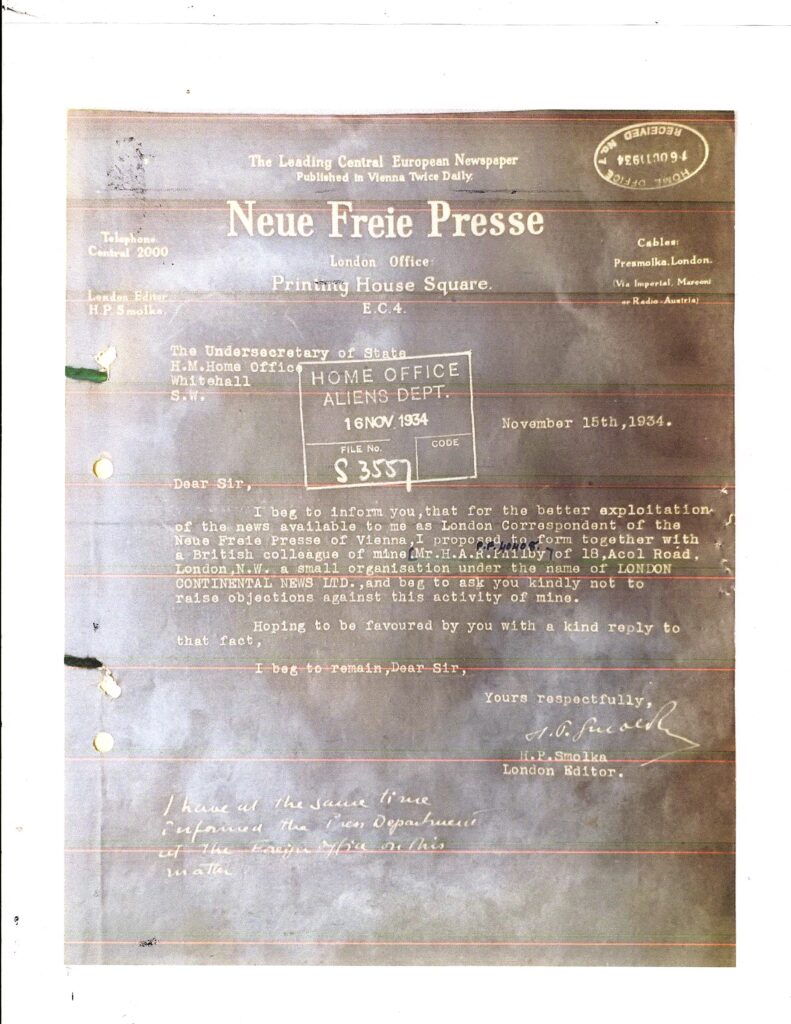

In my February bulletin I reported that I had located an article by Charmian Brinson on Peter Smolka, titled ‘Nothing Short of a Scandal’, but had been frustrated in my attempts to read it, as neither Professor Brinson nor the Austrian periodical that published it had acknowledged my emails. Thanks to Andrew Malec, I was able to find the complete text at academia.edu (of which I am a member), and, as promised, I am now offering a summary of what Brinson brought to the table. (She is not, incidentally, the mystery female academic who behaved so ill-manneredly to me in the email exchange on which I reported in March.)

I have to characterize Brinson’s contribution as ‘workwomanlike’, but not very imaginative. She has performed a vast amount of relevant research: she has read (almost) all the right books, memoirs and histories, British and German, and gone deep into the archives, from those of MI5 and the Home Office, to the records of Czechoslovakia’s show-trials. She has dug our articles in remote places, located papers from obscure universities, accessed old items from newspapers such as the Times in the 1930s, and recovered interviews with Smolka’s sons. And yet her conclusion is simply the rather bland: “So Smolka was and remains a man of contradictions”, as if that could not be said of countless other persons in intelligence who have left a confusing trail behind them. It is as if Brinson wants to serve up all she can find and leave it to the reader to make a judgment. Each time that she appears to be about to explore a fascinating aspect of his life – such as the confirmation that Smolka was a spy, with the cryptonym ABO – she steps back from providing any penetrating analysis. I believe historians – as opposed to chroniclers – should go farther than that.

So I simply note here some of the information that was fresh to me, and some observations on her commentary. She exploits the memoirs of Bruno Kreisky, who was the Austrian Chancellor from, and those of Hilda Spiel, the novelist. Both were close to Smolka in his teens. Brinson supplies the background to Smolka’s highly biased view of Siberia evident from his reports in the Times, and his subsequent book, but shows no interest in trying to discover why he received so much good publicity. She does not attempt to explain why he received the degree of support from the Foreign Office in the late 1930, or what the oily Rex Leeper was up to. She leaves the ‘nothing short of a scandal’ incident undeveloped, treating Smolka’s apparent redemption as routine.

On the other hand, her coverage of Smolka’s work for the Ministry of Information during the war is very thorough, although she doesn’t attempt to adjudicate on the tricky question of when Smolka was recruited to Soviet intelligence, and by whom (a topic which I dismantled a few months ago.) She highlights some important questions about Smolka’s energetic pro-Soviet stance, raised by MPs and others, but offers only a lukewarm explanation as to how he was able to get away with it, before moving calmly on to the discovery of papers produced on his typewriter that were found in Guy Burgess’s flat. And then she suddenly jumps from 1951 to 1961, where she briefly covers the Arthur Martin interview, without astonishment. She does, however, offer an insightful anecdote about the extent of Smolka’s anglicisation, sourced from Hilda Spiel, who also expressed surprise that Smolka would want to return to war-damaged Vienna with his young family once he had had a taken up British citizenship. Brinson also offers useful evidence of Smolka’s pro-communist reportage in Vienna after the war, and describes his relationship with Ernst Fischer, the Minister of Education.

One thing that caught my eye was the statement, again from Spiel, that one George Knepler, a musician, had been living in Smolka’s house at this time (1948). Knepler was a name I knew, as it was he to whom Kim Philby had been directed in 1933. Knepler described the lavish parties that Smolka held for leftish acquaintances and public figures. What did surprise me, however, was the fact that Brinson dedicated only one sentence to the complex ‘Third Man’ business, apparently trusting the story that Smolka provided Greene with his anecdotes. She does not explore any of the contradictions of this bizarre chain of events. On the other hand, she does provide more substantive details on the accusations against Smolka at the Slansky trials, made by an unfortunate liar, Eugen Loebl, who had probably been tortured.

Brinson accurately covers the stories of MI5’s vain hopes to convince emigres like Smolka to ‘defect’, but without any attempt to explore the sense or stupidity of such ventures. She appears to trust the accounts of Smolka’s deteriorating health, which did not prevent him from founding and editing, in the 1970s, the journal Austria Today, at Kreisky’s request. Both Kreisky and the Times gave him a generous obituary when Smolka died in 1980, which leads to Brinson closing her piece with the radically different opinions of Siegfried Beer, who deemed Smolka a Superspy, and those of Smolka’s widow and elder son, who perversely continued to claim that he had never been a spy at all. Thus, for the Smolka devotee who wants to hoover up all the bare facts about his life, Brinson’s article will be a valuable contribution, but as a work of historical analysis it is disappointingly sterile.

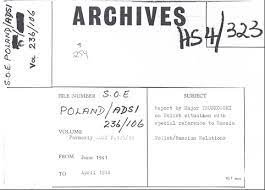

Guy Burgess at Kew

I have previously drawn attention to the scandalous state of records pertaining to Guy Burgess at Kew. My detailed analysis of the FCO 158 series (“Foreign Office and Foreign and Colonial Office: Record Relating to Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean (known KGB spies) and subsequent investigations and security arrangements”) shows that nearly three hundred separate files are listed, most of which have not been digitized. Many of these are needlessly fragmented: thus we can see, for instance, FCO 158/111, ‘Correspondence with member of the public on Burgess & Maclean’, followed by FCO 158/112, ‘Question from member of the public’. There is no reason why several of such items could not have been collected into one file. The objective must be to make it more onerous for anyone to order these files and trail through them.

Moreover, a large number are closed, without proper justification. For example, FCO 158/15, ‘Guy Burgess Private Papers’ is simply listed as ‘Closed and retained by FCO’, with no release date, as are a variety of other papers on topics such as ‘Foreign Office Key Points 1951’, ‘Security Recommendations at DWS’, ‘Correspondence with Irene Ward’, and dozens of records of individual vetting operations from the 1950s that are described only in terms of ‘Vetting of “name withheld”’, with the relevant year following. A file on Petrov, the defector from Australia, is similarly marked.

Others indicate a release date, sometimes with highly spurious reasons for the retention period. Thus some extracts from the contact of Burgess and Maclean with Foreign Office officials under the PEACH inquiry (FCO 158/30/1) – which sounds very bizarre – has been declared ‘closed for security reasons: open January 1, 2035’). One vetting of ‘name withheld 1951-80’ will be made open on January 1, 2073 [should any of us live that long . . . And will left-wing academics still be railing against ‘late-stage capitalism’ in the London Review of Books at that time?]. A file titled ‘Allegations against “name withheld” 1948-1955’ has been ‘closed for Health and Personal info’, but will be available the same date. A closed extract from the Cadogan Inquiry (FCO 158/206) will be opened on January 2032. There are many others of similar characteristics: a minute of September 5, 1952 (FCO 158/254/1) has been closed ‘for health reasons, and will be opened on January 1, 2073’. Maybe the frail subject of that inquiry will have recovered by then.

I believe this is all shameful and scandalous. Why the public cannot be trusted with seeing these records of seventy years or so ago, or why the Foreign Office believes that the disclosure of such items would harm national security, is beyond belief. It must point only to an enormous institutional embarrassment, or simply a loss of any expertise with any incumbent officials to know how to make proper judgments about the material. It is just simpler to pretend that no problem exists, and to hope it goes away. Yet the registration of all these incriminating morsels, and the sensitivity of the Foreign Office about them, points to the existence of highly disturbing testimony to the foibles of British intelligence at the time.

What should happen, of course, is that Freedom of Information requests should be made over all these files. I am advised, however, that block requests are unlikely to have the desired effect, which means that individual files would have to be selected. But where to start, and who has the time to do that? Can some sort of mass public protest be mounted? Come on, ye doyens, get weaving!

Lastly, I was intrigued to read, amongst the Rothschild papers (KV 2/4533-1), in a report dated January 27, 1971, that Guy Burgess’s file was created only in 1942! (That note suggests to me that the writer thought it should have been created earlier.) Of course, MI5 has never admitted that it existed, and his Personal File 604529 (one of dozens created during the PEACH investigations of 1951) is the only one recognized in the various letters, notes, reports and memoranda that emerged during the interrogations of Blunt and the inquiries with the Rothschilds. What prompted that 1942 event is something worth considering. It was a fairly quiet year for Burgess, since he was working for the BBC in the Talks Department, arranging pro-Soviet speakers. Was it perhaps his selection of the Soviet agent Ernst Henri, masquerading as a journalist, that triggered MI5’s fresh interest in him?

A Death in Nuremberg

After an important reference somewhere, I was prompted to acquire Francine Hirsch’s 2020 book Soviet Judgment at Nuremberg, since it claimed to provide fresh information on the trials derived from an analysis of Russian government files. I was especially interested because I wanted to know more about Nikolai Zorya, one of the Soviet prosecutors, who was found dead in his hotel room during the trial. This had been judged by Western participants as very suspicious: the Soviets claimed that it had been an accident that occurred as he was cleaning his rifle, but others considered that his mishandling of the episode of the Katyn Massacre had been the event that led to his demise.

I have long been interested in cataloguing the deaths, in mysterious circumstances, of western civilians with possible past ties to Soviet intelligence. While Boris Volodarsky’s 2009 book The KGB Poison Factory provided a solid guide to many prominent cases, I do not believe that enough attention has been paid to other questionable deaths or accidents that occurred when no one was around to witness exactly what happened. (I have just acquired Volodarsky’s follow-up book, Assassins, and shall be writing about it at some stage.) Any occasion in which someone died of a heart attack in a remote hotel room should especially have been investigated with utmost urgency. The unresolved cases of Tomás Harris and Hugh Gaitskell are quite familiar, but what caused Alexander Foote’s early demise (1956)? Has Herbert Skinner’s premature death in a Geneva hotel (1960) been explained? Or Archie Gibson’s death by shooting in his Rome apartment (1960)? What had happened to Hugh Slater when his body was discovered in Spain (1958)? Did Victor Serge really have a sudden heart attack in Mexico (1947)? Was the event that killed Georg Graham’s son truly an accident? Was Paul Dukes’ car crash purely providential? Did John Costello really die from food-poisoning?

Zorya was of course not the only Soviet citizen to be targeted since the war. (The death of Konon Molody, aka Gordon Lonsdale, from eating poisonous mushrooms, has been laid at the door of the KGB.) But the openness of his probable murder was shocking. As Hirsch writes: “It would have been more typical for Stalin to call someone back to Moscow and then have him arrested and shot.” She goes on to write that Zorya’s son maintained that ‘his father had grown uneasy about the Katyn case and had asked to return to Moscow to talk to Vyshinsky about flaws in the Soviet evidence’. In that case, the NKVD might have been concerned enough to decide that no time should be wasted, lest Zorya share his thoughts with members of the American and British delegations – something he may already have done.

The obstinacy of the Soviet prosecutors in highlighting the Katyn Massacre as an example of Nazi war crimes was really obtuse. Stalin had gone to enormous lengths to show that the killings of 22,000 members of the Polish military and intelligentsia had taken place when the Germans had occupied Belarussia rather than in the summer of 1940, when it was under the control of the Soviet Union. Churchill and Roosevelt were confident that it had been a Soviet crime, but were shabbily reluctant to challenge Stalin over it. When it came to Nuremberg, Moscow naively believed that the trials would be held like those from the 1930s Purges, with defendants tortured and trained what to say, no proper defence counsel offered, guilty verdicts pre-arranged, and summary executions carried out. The Soviets were then surprised that principles of western democratic justice were to be applied to the Nazi criminals, and the prosecutors struggled to adjust to the process. They somehow wriggled out of the embarrassing situation. Zorya was the victim: it was not until 1990 that Moscow admitted that the wartime communist government had been responsible for the massacre.

Holiday Reading: Volodarsky et al.

As my primary serious reading during our holiday/vacation in California, I packed Boris Volodarsky’s recent book, The Birth of the Soviet Secret Police: Lenin and History’s Greatest Heist 1917-1927. Like Volodarsky’s other works, I found it both utterly fascinating and extremely annoying. I had submitted several pages of corrections (mainly typographical) to Volodarsky when his Stalin’s Agent appeared in 2014 – a submission that he eventually thanked me for about two years later. His latest book is very similar, jam-packed with stories of subversion, and profiles of those who carried it out in Europe (mainly), but it desperately needed an editor. Volodarsky has no sense of historical narrative, and owns what I suspect is the inability of someone with a photographic memory to exclude any related facts from his story, which means that he has presented a largely indigestible set of mini-biographies, a compilation of acronyms, aliases, birthplaces, marriages, mistresses, etc. – with the dominant outcome for the participants being a bullet in the head, in the Lubyanka cellars, in 1937 or 1938. Moreover, the text has a woefully large number of typographical and grammatical mistakes, many the mis-spellings of proper names, but also some blunders and direly botched edits that indicate that no one read the final electronic version carefully.

It is not that Volodarsky has the wrong intentions. Halfway through his screed he offers the very sensible guidance: “An absolute sine qua non is that all sources, even primary, must be checked, double-checked and rechecked again. There’s a lot of stuff in the archives that got there by chance, like a forgery accepted as a genuine document, or a report based on a biased interpretation or opinion but nevertheless duly filed. Sometimes a testimony, even of a seemingly credible witness or reliable defector, or a source described as ‘a subject of undoubted loyalty’, may be completely invented and include false claims which later leak into the books and articles. There, as it happens, they are sometimes further misinterpreted or misrepresented.” He uses this method to pass out some harsh words on some of his fellow-historians, such as Helen Fry, whom he chastises for swallowing whole the reputation the SIS representative in Vienna, Thomas Kendrick, had acquired for his provision to his bosses of alleged valuable information, when Volodarsky believed it was totally the invention of money-seeking phoneys. He also has harsh words for dupes like John Costello and Nigel West, being taken in by the wiles of the KGB and its stooge, Oleg Tsarev. Intriguingly, he keeps some of his choicest words of disparagement for Christopher Andrew, whom, while he praises some of the latter’s work (Volodarsky was, after all, a member of Andrew’s intelligence seminar), he criticizes for his naivety in such matters as the Zinoviev Letter, and for his credulity over what Gordievsky fed him.

Yet Volodarsky himself commits similar sins. I was enormously impressed with the author’s encyclopædic grasp of the literature, in books and obscure articles, in multiple European languages, which allowed him to integrate an enormous amount of information. Yet a process of verification must allow not only the primary author to ‘check, double-check and re-check again’ his or her sources: third-party researchers must also have the opportunity to inspect them. Volodarsky frequently refers to (O)GPU (i.e. emergent KGB) files without identifying them. His Endnotes contain acronyms presumably defining Russian archives (e.g. GASPI, GA RF) that are never explained. He cites such sources as the State Military Historical Archives of Bulgaria (an institution probably beyond the reach of most enthusiasts) without explaining why they can be trusted. He refers to documents that exist only in his personal archive, and ‘secret’ files of MI5. (If they have been declassified, they are not ‘secret’). It is as if the rules do not strictly apply to him.

As an example of his style, I quote two passages concerning a subject and period that I have been focussing on recently: “A quick recap: in February 1934 Deutsch went to London and Reif joined him there in April. They worked together until June when Reif left for Copenhagen again. By that time, they already had under Soviet control a considerably large network of sources; agents (in today’s terms – intelligence agents, facilities agents and agents of influence) as well as talent-spotters, confidential contacts, couriers, and so on. In August or September Glading (GOT) introduced Deutsch to an important source whom Deutsch immediately named ATTILA. He usually gave codename to his assets by association . . .” Elsewhere he writes: “Nevertheless, there are reasons to believe that Arthur Willert had evolved from a major source of information inside the Foreign Office in the early 1920s into a fully-fledged Soviet agent named ATTILA while his son was recruited as agent NACHFOLER [sic], translated from German as successor, follower, or replacement. All three definitions pass perfectly. This unsophisticated but quite appropriate code name was given by Dr Arnold Deutsch, the recruiter of Philby and two dozen other Soviet agents in London in the 1930s.”

Apart from the typical misprint (‘NACHFOLER’ should be ‘NACHFOLGER’), I find these assertions about a ‘considerably large network’, developed in such a short time (February-June 1934), utterly preposterous. Philby was interviewed (if his account can be trusted) only in June, and he was not formally recruited until months later. Volodarsky claims that Deutsch recruited two dozen other agents in the 1930s: nowhere does he explain how he is sure of this fact. Nor is the significance of ‘London’, as opposed to Oxford and Cambridge, made explicit. (Moreover, it is not clear why a volume that is supposed to take us up to 1927 dabbles in these events, in any case.) The agent ATTILA, whom Volodarsky in one section confidently identifies as Sir Arthur Willert, is much more tentatively described as unknown in another passage. I find it highly unlikely that Percy Glading, an open member of the CPGB who worked as an engineer at the Royal Arsenal, would move in the same circles as Sir Arthur Willert, or that, if the latter had been a potential agent, he would risk being seen in the company of such a character. Volodarsky suggests that Willert was named ATTILA because he reminded Deutsch of an Austrian actor he knew: it sounds to me as if it were just a simple contraction of ArThurwILLERt’s name.

Amidst all the complexities and muddle one can find many useful insights. Volodarsky performs a solid demolition of the accounts of the Zinoviev Letter. He brings the overhyped Sidney Reilly (‘Ace of Spies’) down to size. He makes an intriguing and provocative identification of PFEIL (‘ARROW’ or ‘STRELA’) as Margarete Moos (who had visited Krivitsky in New York after his story in the New York Post appeared in April 1939). Deutsch wrote, however, that he had recruited STRELA in Vienna, at a time when Moos apparently was in London: more research is needed. Volodarsky offers some very useful notations about the highly suspicious (in my mind) Rex Leeper, who was Willert’s deputy, and later helped Peter Smolka (a story that Volodarsky has not reached yet.) He is rightfully scathing about the propaganda ruse executed against the British in the KGB-controlled Oleg Tsarev collaborations with Costello and West. There are innumerable fascinating leads to be followed up.

Yet he seems so wrong on many points – for instance, in his assessment of Krivitsky, whom he savagely debunks, resurfacing his criticisms from Stalin’s Agent, and in his throwaway claim that GC&CS was able to start decrypting Soviet traffic at the outbreak of war in 1939, a highly controversial assertion for which he offers no evidence. The merciless display of sometimes trivial facts about a host of dubious characters wore this particular reader down. Some day I hope to give the book a more thorough treatment. And incidentally, why the ‘Secret Police’? Policing is a task for internal security forces, not active subversion undertaken in foreign countries. The KGB did both, but the title is inaccurate. A volume for the diehards only.

While I was away, I read five books borrowed from the excellent Los Altos Public Library. Mary Kathryn Barbier’s Spies, Lies, and Citizenship was a weak, unimaginative and poorly-written account of what the Office of Special Investigations did concerning the hunt for Nazi criminals who had been allowed to escape (C+); Scott Miller’s Agent 110, about Allen Dulles’s attempts to go beyond gathering intelligence to forging deals with the Germans in Switzerland was a respectable and restrained integration of several key stories, but revealed little new, and could have benefitted from more rigour in background history (B); Howard Blum’s Night of the Assassins addressed a potentially gripping and important topic, namely the German plot to kill FDR, WSC and Stalin in Teheran in 1943, but Ben Macintyre would have done a better job. Despite an impressive list of primary sources, and a pragmatic approach to truth-telling, Blum provided a long-winded and cliché-ridden concoction – replete with ‘doe-eyed, raven-haired’ mistresses, ‘lantern-jawed, broad-shouldered’ intelligence officers, and too many incidences of ‘Jawohl, Herr Obergruppenführer’ (C+). Sleeper Agent, by Ann Hagerdorn was excellent. The story of how George Koval, born in the USA, went with his parents to their birthplace, the Soviet Union, in 1932, and then was infiltrated back in 1940 to become one of the most important atomic spies for the GRU, was very compelling. He absconded back to the Soviet Union in 1948, just in time to experience Stalin’s renewed persecution of the Jews, but he was not identified by the FBI until decades later, partly because of Solzhenitsyn. A remarkable piece of investigative research by Hagerdorn, free of rhetoric, padding, and cliché, although it is diminished somewhat by the fact that her Acknowledgments list hundreds of persons who helped her (was she a project manager or an author?). The lack of identification of GRU archival material is also a letdown, since she relies too much on Vladimir Lota (A-). Never Remember: Searching for Stalin’s Gulags in Putin’s Russia, an essay by Masha Geesen with photographs by Misha Friedman, is a poignant description of how Putin has undone all the revelatory work that Memorial performed to bring home the horror of the Gulag.

While in Silicon Valley I bought Jason Bell’s Cracking the Nazi Code, a volume that I had ordered some weeks ago from the History Book Club, who informed me, just before we set out for California, that it had no copies left. It’s a misleading title, since it refers to the achievements of Winthrop Bell, the Canadian philosophy professor who was recruited by MI6 at the end of WWI to advise on how to handle a defeated Germany, in interpreting various German political initiatives. It is an extraordinary book in many ways, since the author (no relation) was able to exploit the Bell archive, opened in 2012, to discover how Bell had alerted the British and Canadians to the dangers of nazism well before Hitler’s arrival, in the activities of Ludendorff and the Freikorps in 1919. He echoed these warnings in 1939, when he pointed to the coming mass murders of non-Aryans. I do not believe this story has been told before: I would have given it a higher marking had the author, in the last third of the book, not become so repetitive, or distracted by the story of radar, and not indulged in so many observations about phenomenology. He overall provides decent context, but is a little too consumed with the excellence of his biographical subject (B+).

Coldspur under stress

My friend of many years, Nigel Platts, recently informed me that, while he was on holiday in Cumbria, he was unable to access coldspur, the browsing of which must be a highly desirable diversion in those wild and occasionally bleak parts of the United Kingdom. Sky, his broadband provider, informed him that its ‘shield’ had blocked the site on the grounds that it was associated with ‘hate, gore, and violence’ (or similar wording), which came as a bit of a surprise to us both. Even my invectives against charlatan historians could hardly be described as inflammatory, so I wondered whether my descriptions of Cheka outrages over a century ago could somehow have engaged the censor’s attention. (Of course the exclusion could have been performed by some AI-enhanced mechanism, which would explain a lot).

Yet this was not the first occasion of blocking that I have come across. A long-time correspondent in the Liverpool area used to tell me that he had to deploy some devious tricks to get round a similar prohibition. I recall also that, when I was working at the National Archives in Kew, coldspur was permanently unavailable, which perhaps hints at some more deliberate attempt at security, and at preventing pollution of correct thinking among the country’s elite researchers. Could browsers who have had similar experiences perhaps inform me of them? I shall need to maintain a dossier to provide evidence if and when I take this further.

And then I had to deal with the Chinese. I received a strange email from a businessman in Shanghai, who claimed that one of his clients wanted to use coldspur.cn and coldspur.com.cn for their business. The fellow claimed that he had tried to talk his clients out of it, but they were insistent, and he invited me to register the names myself, so that my ‘business’ could be protected. Of course, I didn’t believe a word of it. He was just trying to collect registration fees from me. According to that logic, I would have to register coldspur with every other national suffix to prevent my hordes of eager browsers from being misdirected.

Oh, the trials of being a website administrator . . .

News from Academia

In the middle of May I received the following message from the University of Oxford American Office:

| Dear Tony, June is LGBTQ+ Pride Month in the US, and this month we are celebrating by highlighting the exciting work being done to teach LGBTQ+ history at Oxford and how you as an alumnus can help. There is an enormous appetite for LGBTQ+ History among graduate students, and scholarships associated with the Jonathan Cooper Chair of the History of Sexualities, the UK’s first permanently endowed Professorship in LGBTQ+ History, will allow these students to pursue their interests and become future thought leaders. |

| The Jonathan Cooper Chair Named after Jonathan Cooper OBE, an expert in international human rights law and activist for LGBTQ+ rights across the globe, the Cooper Chair, held by Professor Matthew Cook since 2023, explores histories of sexual diversity in all their variations, exploring their intersection with categories such as race, class, generation, occupation, education (dis)ability, nationality and community. Professor Cook is the first postholder of the Cooper Chair, made possible by the generosity of philanthropists. There followed a message from Professor Cook: “This work matters not only to LGBTQ+ individuals and communities but to us all: histories that look from the margins provide fresh perspectives on shifting norms and enhance our understanding of wider social, cultural and political realms. Scholarships are key to this mission: I see so many talented students diverting away from further study because they lack the funds – an issue especially for those who lack family support. Underpinning their further study is an investment in their talent and in histories which play a key part in the drive for social justice.” – Professor Matthew Cook |

I was astonished, and a couple of days later, responded as follows:

I thought at first that this message must be a spoof, but I then realized you are utterly serious. How can you pretend to any academic excellence when you ascribe such importance to this non-subject?

Whatever “LGBTQ+” means, it is a ragbag of genetic dispositions and behavioural choices (most of which should probably be kept private), a creature of the media and phony academics kowtowing to fashionable notions of ‘exclusion’, ‘victimisation’ and ‘identity’. What about adulterers, asexuals and foot-fetishists? Why are they excluded? How could anyone claim to be able to study ‘histories of sexual diversity in all their variations’?

‘Exciting work’, ‘enormous appetite’, ‘future thought leaders’, ‘LGBTQ individuals and communities’, ‘drive for social justice’, ‘constructs that disempower historically marginalized groups’ – what a lot of pretentious nonsense. It reads like a parody of an old ‘Peter Simple’ column in the Daily Telegraph. How anything useful or insightful could come out of such ‘research’ is beyond me. But I do know that the University has forfeited all chances of my making any further donation to any of its causes, however worthy.

Sincerely, Tony Percy (Christ Church, 1965)

Then, from the other end of the spectrum, on June 14, I noticed that Christ Church Development had posted an announcement on Facebook. It read:

His Majesty the King has approved the appointment of two new Regius professorships at Christ Church.

We look forward to welcoming Professor Luke Bretherton as Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology, and the Revd Professor Andrew Dawson as Regius Professor of Divinity in the coming months!

Ye gods! What possible fresh revelations could these two gentlemen come up with? I can understand the study of religion as a topic of interest under Anthropology, perhaps, but Chairs in Gods [and Goddesses? Please verify. Thelma.] and Godliness? I learn, however, that the Regius Professorship of Moral and Pastoral Theology was established by an Act of Parliament in 1840, and the show must therefore go on. But is it not time for a repeal? I also read that Professor Bretherton arrives from Duke University in North Carolina, where he has been Distinguished Professor of Moral and Political Theology. His latest book ‘provides a new, constructive framework for what it means to live a good life amid the difficulties of everyday life and the catastrophes and injustices that afflict so many today’. His role sounds more like a preacher or social worker, to me, rather than an independent and disciplined academic. I hope he will adjust quickly from the difficulties of living in Durham, NC to those of provincial England. I would also suggest Bretherton ought to get together with Professor Cook and work on the ‘social justice’ goals. Dr. Spacely-Trellis, where are you?

But then others will say: a doctorate in Security and Intelligence Studies? Can that really be an academic discipline? Seriously?? Maybe if it took up the ‘social justice’ cause . . .

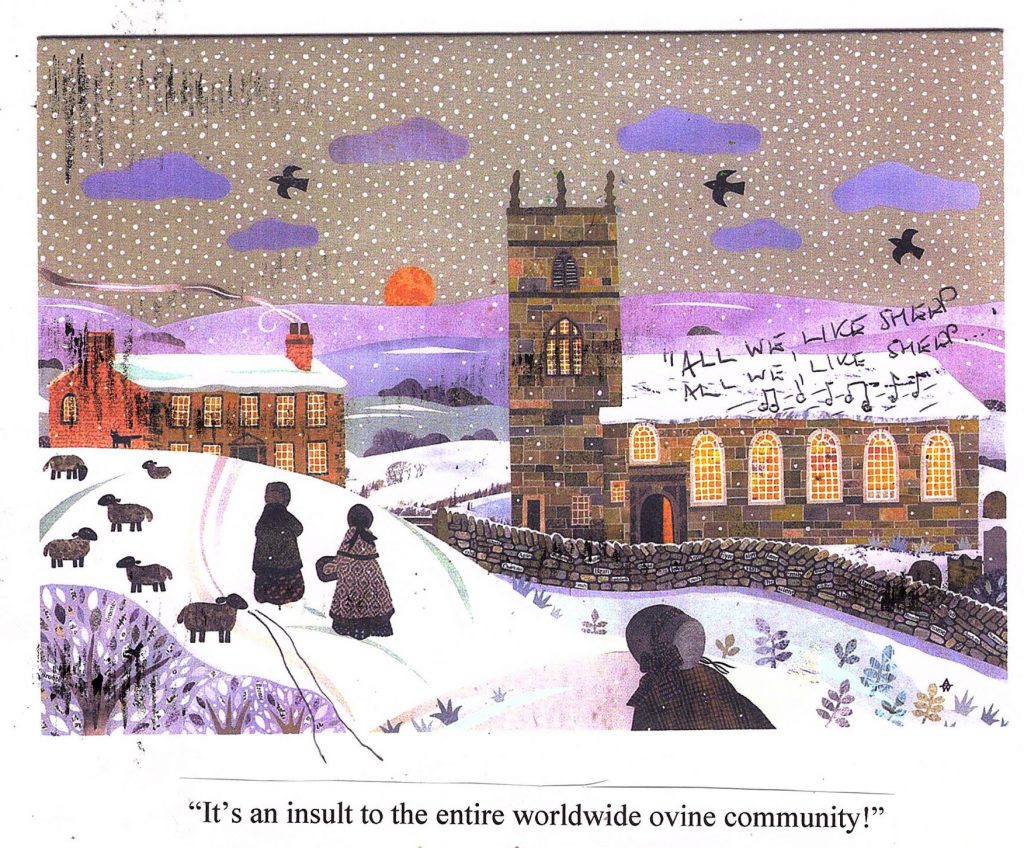

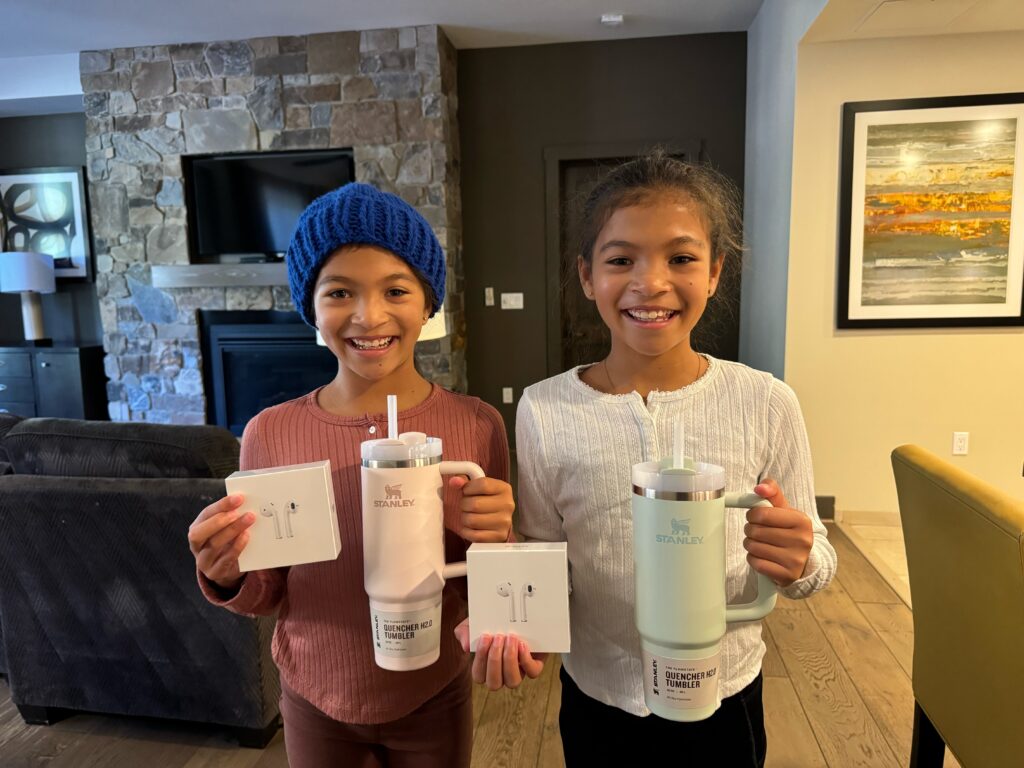

Similarity and Identity

The primary objective of our spell in Los Altos, California, was to re-engage with our three grand-daughters, whom we hadn’t seen for a couple of years. The twins, Alyssa and Alexis, celebrated their eleventh birthday just before we arrived, and the photo above shows them with the gifts we had given them. I was struck by the resemblance of Alexis (on the right) to (a younger version of) Emma Raducanu, who represents England – by way of Canada – as a tennis-star. Now I note that Ms. Raducanu has a Romanian father and a Chinese mother. Alexis is 50% Vietnamese, 25% English (whatever that means, with Huguenots, Germans and possibly the Perskys from Minsk in the running), 12.5% Irish (probably), and 12.5% ‘Black’ West Indian (more likely African than Black Carib, the descendants of the original islanders who still live on St. Vincent). Is the similarity not a bit uncanny?

I write this just to show how absurd all tribal identities can be. When I fill out government forms, I am always dismayed by the long list of entries under ‘race’, one of which I am required to fill out (although I can actually cross the ‘Decline’ box). I recall checking ‘South Pacific Islander’ on one fanciful and courageous occasion during my recent Tahiti phase, and, some time afterwards, I received a visit from a Census Bureau officer. He confronted me by suggesting that I had offered an untruth on a government form – rather like Hunter Biden denying that he was a drug user when he applied for a firearms license, or von Bolschwing omitting his membership of the Nazi party in his naturalization application, I imagine. I protested that I sincerely believed, with the current focus on ‘identity’, that a citizen was entitled to make any choice that he or she wanted to. If I could choose my own pronouns, why shouldn’t I pick my own ethnicity? After all, I didn’t see why an indigenous Quechua from Peru, whose forbears had been the victims of the Spanish Conquest, should be encouraged to enter the meaningless term ‘Hispanic’ when he or she applied for food stamps, or a passport renewal, or whatever. As proof of my ethnicity (or denial of any), I could now show any such official the photograph of Alexis. “Doesn’t she have the Percy chin, officer?”

(Latest Commonplace entries can be seen here.)