Contents:

- Publicity

- Richard Davenport-Hines

- The coldspur Library Project

- Blunt Lessons

- Detective Work

- Roger Hollis in Australia

- VENONA

- Victor and Venetia (continued)

- Car accidents?

- The Illegals

- ‘Murder in Cairo’

- Other Books Read

- Ethnicity

- British Magazines

Publicity

Every week, I receive several unsolicited emails from around the world, coming from consultants who have discovered coldspur, and want to improve my SEO (Search Engine Optimization) performance. The messages follow a regular pattern: the firms have detected multiple errors on my site, with their help I could vastly improve coldspur’s rankings with Google and other search engines, and I could therefore dramatically increase the number of visitors as well as the revenue derived from them. They all want me to respond by requesting a cost proposal. Fortunately all these messages go into my Spam folder, and individually they trouble me no more.

Yet I believe these outfits would not have noticed coldspur unless it had already cropped up frequently in search engines. These chaps have clearly not even looked at what I publish, since they would have realized that the tight editorial procedures imposed by the coldspur team mean that coldspur does not contain errors – and if one or two do slip through, they are quickly rectified. Moreover, if they had spent only a cursory glance at the coldspur format, content and delivery, they would have understood that it is a vanity project, with no advertising, and no subscription service, and thus carries no opportunity for increasing revenue. Lastly, I believe that coldspur already ranks very highly with search engines. For example, I have just typed in to the Google search bar ‘Missing Diplomats’, and the first relevant item listed is a page from coldspur. I next typed in ‘Peter Smolka’, and coldspur appears second, after the Wikipedia entry. That looks to me as if my reports are receiving due attention. Or is some kind of AI bot gratifying me? Is this the experience of others? ( I suspect Google results vary from country to country, and maybe by user.)

Thus I do not think that my visit to the UK in September is going to make much difference to the visibility of coldspur. I had vaguely thought about putting some effort into arranging further talks around the one arranged at Whitgift School, in order to help publicize my research, but I am not now going to bother. I have been let down in this area before. Readers may recall the nonsense with the University of Aberystwyth a few years ago, as well as the incident of the Norwegian professor who last summer promised me a slot in Oslo to talk about the PB614 disaster at Nesbyen. Stimulated by his enthusiasm, I started to make plans in the UK, and then his deal fell through. Earlier this year, I was grossly insulted by the Friends of the National Archives (who completely ignored me), the Friends of the Bodleian are too busy, and after four weeks of waiting for Christ Church to respond to my offer to speak on Dick White, I have given up in disgust. I shall probably abbreviate the length of my stay by a few days, and simply enjoy meeting individual friends and contacts, and maybe visiting one or two archives or museums – especially the MI5 exhibition at the National Archives, which is reported to be displaying some special items on Philby ‘loaned’ from MI5.

Richard Davenport-Hines

Readers will recall my expressed frustration with trying to get in touch with the renowned historian, biographer and critic Richard Davenport-Hines. The Times Literary Supplement had published a letter from him on the Borodin business, and, in a correspondence with the Letters Editor at the weekly, I had sought an introduction so that I could discover what the source of Davenport-Hines’s very fragmentary – and dubious – evidence was. I had worked out that D-H had discovered my review of Agent Sonya, but he declined to contact me. Eventually, however, I was able to get an alternative email address from an acquaintance of his, and I was very gratified to receive a response from him. Sadly, D-H had undergone a stroke, which had affected his memory, and he apologized to me, since he had assumed that he had already communicated with me.

In the meantime, I had stumbled upon the source of his intelligence – some items at the front of the Goronwy Rees file that I had overlooked beforehand. I had not come across the Borodin affair when I first studied the file, and those components had meant nothing to me at that time. Since then I have discovered much more about the very bizarre goings-on involving Guy Liddell, Goronwy Rees, Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt and the attempted disinformation campaign (as I am confident it was) to deceive the Soviet Union, as well as details of how the 1949 Conference at Worcester College, Oxford was set up, and what its detailed agenda was. These details are all to be found in Guy Burgess’s Personal Files, and I shall report on them at a later date. I was happy to explain my ignorance to D-H, pointing to my coldspur posts to demonstrate why I thought much more sinister activities were afoot.

D-H was gratifyingly very positive about my research. I was amazed that the first paragraph of his message to me was: “What a wonderful source Coldspur is! I have been reading through it, & have learnt much, & been given much to think about. I had consulted Coldspur in the past, but because of my brain damage, had forgotten all about it: I won’t forget again: it is too good to miss.” He went on to compliment me on Misdefending the Realm: “Your mastery of the sources, and your fairness in evaluating them, is first-rate,” and he went on to encourage me to get the Borodin story published in a book, since it was ‘very original stuff’. We exchanged some thoughts about Donald Maclean and David Footman, but the exchange has since died out. No matter: I am enormously pleased that such a celebrated expert should have recognized my contributions to intelligence research, and just deeply sorry that his skills as an analyst and story-teller may have been impaired by his disability. Here I publicly wish him a full recovery.

He is not the only coldspur-reader who has urged me to write another book. Yet I doubt that will happen. After my last experience, when I had to do practically everything myself (even ordering a review copy from amazon.uk for the TLS since my publisher had gone on holiday to India without informing me), I do not really want to embark on another book-production venture, with no agent and no publisher, and being domiciled 3,500 miles from the action. The opportunity cost of tidying-up, repackaging, index and sourcing one of my major stories in the hope that a publisher would accept it is too high. I have too many other projects that I wish to address before I shuffle away in my slippers, hang up my boots, or pop my clogs. My stuff will continue to appear on coldspur – subject to the accessibility of my library.

The coldspur Library Project

Progress has been made in transporting books from my library to the Percy Family Special Collection at the University of North Carolina in Wilmington. In January, a team arrived at my house to box up over a thousand volumes – items not critical for my ongoing research, but still significant. (I have already reached out for a volume of the old Dictionary of National Biography only to be reminded that that set was included in the first shipment). At the end of this month, a further two thousand books – history, biography, poetry, miscellaneous – were boxed up and transported. It is with mixed feelings that I see the departure of these items: I have to keep telling myself that this is what I wanted. It was my strong desire to see my collection housed properly in an academic institution, but I shall adjust poorly to trying to work when I can no longer have immediate access to a vital publication. Eventually even the ‘core’ component of one or two thousand books on intelligence and espionage will have to go too, and my ability to perform my traditional research will dissipate. A visit to the university, thirty-five miles away, will have to be carefully planned so that I shall be able to access efficiently what I need.

Thus I can envisage the day – perhaps at the end of 2026, when I shall have entered my eighty-first year – when the nature of coldspur will change. I may then focus on shorter analyses of digitized archives, and on book reviews, and not attempt such deep, multi-dimensional analysis. I may concentrate on more autobiographical entries, and gradually wind the blog down. Yet the whole purpose of the exercise is to ensure that the coldspur archive, already over three million words almost exclusively on intelligence matters, will be permanently available. Not only will my library be available for visitors, but an electronic portal will be constructed that will introduce visitors to my research, and provided indexes to other paper archival material (articles, letters, magazines, clippings, etc.) as well as the vast electronic vault of information (notes to books, registers of personalities in intelligence, summaries of archival meta-data, articles and other digitized information, photographs of undigitized archives, correspondence with other researchers and historians, etc., etc. as well as my ‘Crown Jewels’, the enormous Chronology of Events for the twentieth century that comprises over four hundred pages of line entries on Word, with sources.

My objective is that, as the National Archives eventually declassify more material during the rest of this century, historians will be able to pick up my research, and extend it when they interpret the files that have been hung on to for far too long. That is why proper organization of the portal, and appropriate marketing of the facility, are essential. When future historians need to consult original published volumes on intelligence, they will find no more comprehensive collection of texts available in one place than in the Percy Family Special Collection. I have to report with some regret that I have had some problems convincing the authorities at UNCW of the seriousness of the project, but I am hopeful about sorting out such teething problems soon. In that respect, the Bodleian Library has since reacted with greater interest to my announcement from last year than has UNCW! I have been a Lifetime Friend of the Bodleian for many years now, and, in its centenary Special Edition magazine, the story of my arrangement with UNCW, and long-standing relationship with the Bodleian, were featured. (I do not believe that this periodical is on-line, but I can send a pre-release electronic version to anyone who is interested.)

Blunt Lessons

The nature of my research frequently encourages me to move towards a culmination of a particular topic, as in my recent theory about the management of the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean. Yet that is an illusion: the research process is endless, and my continuing study of the Burgess, Maclean and Blunt Personal Files has unveiled events and accounts that are vital for extended interpretation. Thus I occasionally insert fresh discoveries into what should be summary pieces. It may appear clumsy, but I am in a hurry to publish new analysis, with sources identified. Occasionally I go back and revise an earlier piece, a practice I dislike (as an anecdote below exemplifies), but I am careful to annotate where and why I have done so. That is, at least, a benefit of having control of an on-line publication.

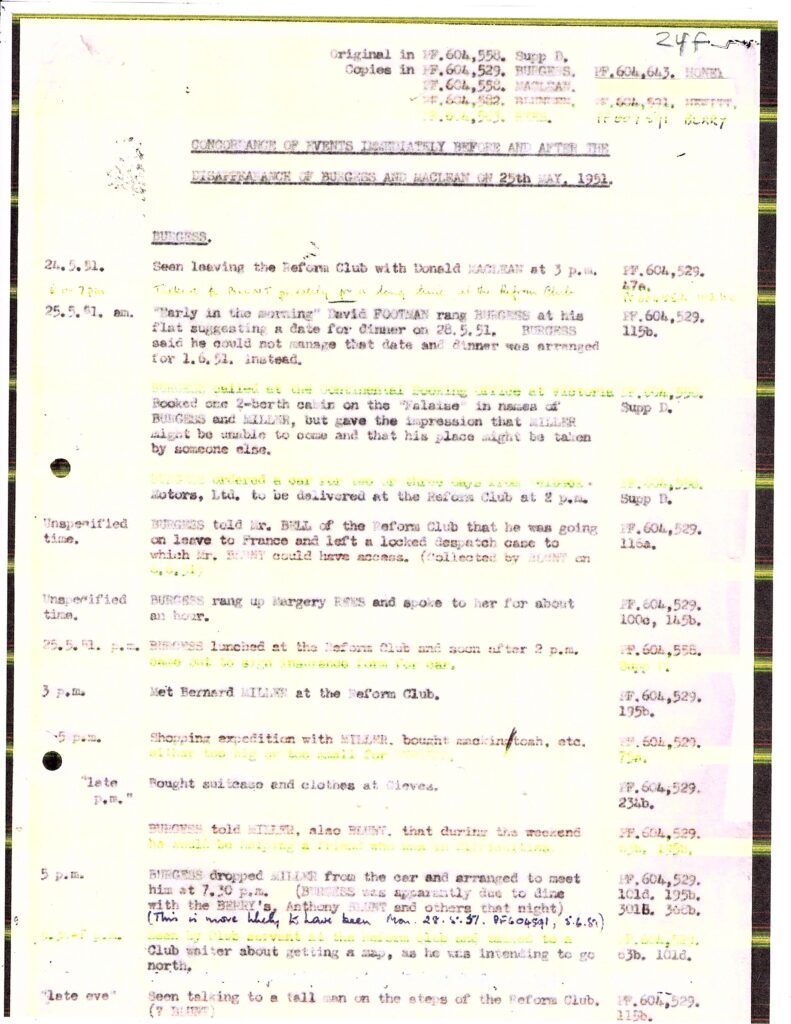

Two recent experiences with the vast Blunt (‘Blunden’) Personal Files – KV 2/4700-4722 – highlight the challenge. I decided, in mid-May, that I needed to start work on them even though I had not finished with the Burgess and Maclean PFs. After showing a useful miscellany of pieces from 1935, KV 2/4700 starts the ‘modern era’, i.e. post-May 1951, at sn. 24f, on page 186 of 316 (working backwards). It consists of a very familiar report, ‘Concordance Of Events Immediately Before And After The Disappearance Of Burgess And Maclean On 25th May, 1951’, the original of which appears in Maclean’s PF 604558 at sn. 98z, on page 10 of KV 2/4140-2. Yet I immediately noticed an anomaly (see image below). A hand-written entry has been inserted for Burgess’s activities on the evening of May 24, reading as follows: “Talked to BLUNT privately for a long time at the Reform Club”, with a reference of PF 604582 1112 bc.

This was rather shocking. When had that entry been made? If the fact had been known early on in the investigation, it should have provoked a serious inquisition of Blunt, in order to determine what he and Burgess had been discussing the day before the escape. This version of the report is undated, but I verified that the original was compiled by J.A. of B2B on October 14, 1952. I needed to inspect the source at 1112bc in KV 2/4720. It turned out that it derived from an interview with Squadron Leader Richard Leven undertaken on August 18, 1972. (I wrote about that encounter in last month’s coldspur.) The MI5 officer Maconachie who wrote up the meeting added, helpfully, that ‘the information that BLUNT and BURGESS had a long conversation in the Reform Club in the early evening of either day [sic] seems to be new to us.’ Who are the ‘us’, one might ask? Who in 1951 was still around in 1972? And might that information have been known at the White level, but withheld from junior officers?

In any case, I think the insertion without a date was a very irregular and irresponsible practice. It could lead a researcher to believe that the information had indeed been officially known in October 1952, and thus should have been acted on. The implications are very controversial: maybe someone decided to insert the annotation for that very reason. If Burgess had been under such strict surveillance as the rest of the record suggests, and his activities at the Reform Club closely monitored, such a meeting would have had profound significance, and Blunt should have been questioned about it. In the master schedule in KV 6/145 (which was compiled in June 1953), Blunt is indicated as being seen with Blunt at the Reform Club on May 23, and as speaking with him on the telephone at 10:00 am on May 25, but no record of the May 24 meeting is presented. In fact, it presents a conflicting dinner engagement between Burgess, Peter Pollock and Bernard Miller at the Hungarian Csardas Restaurant that evening. (Did that event really take place?) Moreover, all questioning of Blunt on his involvement with Burgess before the disappearance is restricted to the telephone call on the morning of May 25. It is outrageous that Blunt’s inquisitors had not familiarized themselves with the chronology, and had let him get away with claiming that his short meeting with Burgess on the morning of May 25 was his first exchange since the Monday of that week.

So, how to interpret the insertion? Remember, these events occurred between Blunt’s confession (1963) and his unmasking (1979), at a time when MI5 was concerned about the truth coming out. J. A. Cradock (of K7, which was responsible for investigating Soviet penetration), to whom Stella Rimington gave her report on Leven, appears confused by the chronology in his memorandum of January 3, 1973 (at sn. 1128a). Another hand-written annotation appears on it, apparently by ‘LK’, drawing attention to the ‘long talk’, but inexplicably getting the date wrong (May 25). The handwriting is the same, so LK must have been the officer who made the amendment to the Concordance in KV 2/4700. [Unfortunately, Stella Rimington makes no mention of her personal projects on Blunt, Burgess and Leven in her memoir, Open Secret.] Yet both items are undated, so it is impossible to determine when, and with what authority, the change was made. My enduring questions: “What did he or she know at that time, and what did he or she see as her task?” face perpetual challenges.

The fact that the annotation was made on a file that would not have been generally available suggests to me that it was made with high authority. Leven must have been deemed a trusted source, and LK must have judged that the omission was important enough to appear on the record, perhaps as a subtle hint that the investigation into Blunt had not been as thorough and objective as the official story told. On the other hand, the utterly careless approach to chronology is bewildering, as is the lack of open recognition that the several meetings or exchanges between Blunt and Burgess in May 1951 should have come under closer scrutiny. There must be fresh secrets to be revealed – especially when I come to unravel the antics of Peter Wright (whom Rimington did not think highly of).

The other lesson derives from an interview of Blunt carried out by Ronnie Reed and Courtenay Young on May 15, 1956 (sn. 207c in KV 2/4702). It makes painful reading: the inquisitors are anxious to extract information from Blunt without antagonizing him, which means they do not challenge him vehemently on the obvious holes in his stories. One topic does, however, appear to rattle Blunt, and that is when Courtenay Young informs Blunt that a member of British Counter-Intelligence in London had handed over to the RIS dossiers on members of the Soviet Embassy, so that they could be photographed. (Razin is not mentioned by name, but this episode clearly has its roots in the Petrov affair.) While Blunt is given time to collect his thoughts, Young interpolates that the only candidates who had access, and were in London around that time were Hugh Shillito, Young himself, and Blunt. Young then excludes himself, claiming that he was also out of London at the time. “I think this certainly is a real tougher one,” ponders Blunt, earnestly.

Blunt’s explanation is that, to his immense chagrin, he took documents back to Bentinck Street to read in the evenings. Young interrupts to ask whether Burgess was a photographer (the implicit suggestion being that, if the dossiers were to find their way to the Embassy, Burgess would have had to photograph them quickly, before he was noticed.) Blunt does not think that was one of Burgess’s talents, so Reed helpfully suggests that Burgess must have handed over the originals for photographing. Yet, instead of querying how Burgess could have managed to convey the dossier to the Soviets without Blunt’s noticing (when he had, after all, brought them home only for the evening), Young disastrously lets Blunt off the hook, suggesting that Burgess, who came into the MI5 office frequently, could have gained access to the documents – which were presumably lying around instead of being locked up. (Young and Blunt agree that security was pretty shambolic.) Of course, Blunt cannot remember clearly whether he had left Burgess alone in a room or not. Despite the fact that the evidence points to a stream of files being passed on over a period of time, the conversation peters out, as if three old codgers were reminiscing.

The whole exchange was recorded, and can thus be read. Young’s summary of the discussion (dated June 5, 1956) is feeble. He admits that Blunt could offer no plausible explanation as to how the leakage occurred, and instead he reports Blunt’s revised assertion that he would have not taken the dossiers back to Bentinck Street, since there was no reason for him to study them, or to take action. Young concludes his paragraph by quoting Blunt again: “I think this is extremely obscure and I am sorry I cannot offer any help.” Ten days later, the Deputy Director-General Graham Mitchell noted: “D.1. [Young] and Reed conducted the interview with pertinacity and skill.” It makes one weep. [Calm down, coldspur. It’s just counter-espionage. Ed.]

The ineptitude in not following up the obvious holes in the case is enormous: If Blunt took the dossiers to Bentinck Street, how could he consider such an appalling security lapse? How big were the dossiers? When did Burgess have the opportunity to inspect them? Read them? Photograph them? Then why did the report state that the originals had been taken to the Embassy for photographing? And why did Blunt change his mind and suggest that Burgess had borrowed them at St. James, where MI5 was housed? And how come such files were conveniently left hanging around, over a period of time, for Burgess to pick and choose? [I note here that, in his ‘confession’ to Arthur Martin in April 1964, Blunt claimed that he had never seen any PFs of Soviet Embassy staff!] Even if Mitchell and his crew felt uneasy challenging Blunt over such points in their ‘interview’, they should have returned for a much colder and well-prepared interrogation at a later date.

Lastly, this episode represents a spooky echo of what happened in June 1951, when Dick White undertook his similarly disastrous interview of Philby immediately after the latter’s return from the United States. It is not clear what White’s objectives were in this interview, but he gives every impression of trying to let Philby off the hook, instead of challenging him on the points of the critical dossier on his subject that he had just sent to the FBI. In my earlier report (https://coldspur.com/special-bulletin-not-the-kim-philby-personal-file/) I explained how White raise the notion that Burgess might have got wind of the HOMER investigation by snooping around the British Embassy in Washington – a notion that Kim Philby encouraged. It is almost as if White had trained Blunt what he should say should he ever be confronted with the embarrassing evidence coming from Razin. I shall be exploring these conundrums further in next month’s coldspur.

Detective Work

A few weeks ago, I was irritated by the theme in the Spectator crossword puzzle, in the issue of February 22, titled ‘Very large fellow’. It concerned someone named Richard Osman [‘OutSize – Man’ – geddit?], and the unclued entries were all characters in some obscure book that he had apparently been responsible for. The Spectator is supposed to be a magazine with an international audience, and the puzzle, by Doc (Tom Johnson), who is the periodical’s crossword editor, was typical of the trivialization of themes that he has encouraged over the past couple of years. Having to resort to the Web to hunt down the names, I discovered that Osman had written a book titled The Thursday Murder Club. I thought little of it, submitted my entry on-line, and awaited next week’s puzzle.

Some time afterwards – perhaps on Facebook – I picked up the fact that the movie rights to the book had been acquired, and that Helen Mirren and Ben Kingsley would be appearing in the film, which was impressive. Netflix has started advertising it. The reviews of the book seemed quite glowing (it had been a New York Times best-seller, but, since I no longer subscribe to that journal, the fact had escaped me), and I hence inspected a copy of the book at Barnes and Noble a few weeks ago, and bought it. It started off well and wittily – hokum, of course, but a pleasant diversion from my customary gritty reading – but then became rather tiresome as it wound down, with too many unlikely complications and some slip-ups in chronology. Yet it reminded me that what I try to do in my analysis of intelligence conundrums is precisely what the members of the Murder Club (Elizabeth, in particular) set out to do when a body drops in front of their eyes.

Take my latest puzzler – Milo John Reginald, Lord Talbot de Malahide, who was accused by some of being another Cambridge spy, and, in his highly dubious role as deputy Security Officer in the Foreign Office at the time of the Burgess/MacLean disappearances, spoke up much too late about his knowledge of what his cronies had been up to. Based on what Malahide’s friend Tony Scotland has recently written about him, he had been interviewed intensely at the time, but nothing had happened. Indeed, when his boss, George Carey-Foster, moved on the following year, Malahide was appointed acting Head of Security, which provokes all manner of observations about foxes, chickens and henhouses.

Moreover, was there a murder angle? On April 14, 1973, Malahide was found dead in his cabin on the M.V. Semiramis, ‘lying in bed as though asleep, with what looked like a broken blood vessel under the skin on his forehead’. His companion Hugh Cobbe assumed it had been a heart attack, and the ship’s doctor, who carried out a careful examination, formally confirmed death by natural causes. No post mortem was required. Now, I have been in this business long enough to be very suspicious when anyone associated with Soviet intelligence is found dead, alone, in a hotel room or other secluded area, with symptoms of having had a heart attack. I think of Harold Gibson and Herbert Skinner alongside the more well-recognized victims. Had this been some kind of revenge attack, or punishment, by the Special Tasks unit? Speculation in the Irish media afterwards suggested that it could have been a KGB or MI5 job.

Maybe that was going too far, but the case of Malahide is very odd. He had had a career in MI6 and the Foreign Office, and was brought into Carey-Foster’s security team (‘Q’ Section) in 1950, although his attendance was erratic. Yet, if he came under suspicion in June 1951, what happened to the transcript of his interview? Why was he allowed to leave for a holiday in Tasmania soon afterwards? Why, if there were undeniable claims about his close relationship with Guy Burgess from their Cambridge days, was he not invited to resign, as was David Footman in MI6? Why, in those circumstances, was he appointed as acting security officer when, in 1952, Carey-Foster moved on (to Rio, and then Warsaw, where he maintained a close interest in the Burgess-Maclean post-mortems)? Was Carey-Foster pushed out? Why, when the Foreign Office was cracking down on homosexuals and other dubious characters in the wake of the Cadogan Report, was Malahide promoted? And what was the role of Patrick Reilly, who had been a close friend of Malahide’s at Winchester College, and had gone on holiday to France with him in 1930? Had Reilly contrived to insert Malahide into the Security Office, since Carey-Foster’s attempt at broom-cleaning was proving very unpopular with the Foreign Office mandarins? Was Reilly behind Malahide’s promotion? And why was Malahide eventually forced to resign in early 1954 – before the Petrov incident blew up? Was he suspected of having been a Soviet agent in the Ankara Embassy in 1945, shortly before the Volkov incident? Had Malahide really been a Soviet agent, or was he perhaps an agent-of-influence, like Rothschild or Berlin, who was careful never to touch or pass on any confidential material, but could certainly help to manipulate events?

Rothschild himself is a conundrum. He was willing to dribble out names to MI5’s investigators, but may have deliberately concentrated on small fry. Why did Rothschild not identify Malahide when he was providing ‘helpful’ tips to MI5 about Burgess’s cronies? Malahide’s name first comes up overtly in March 1966, so far as I can tell, when Evelyn McBarnet and Peter Wright interview the Rothschilds. At sn. 74a in KV 4532, after a long discussion about Klugmann, Harris, Walter and others, the following note appears: “PMW read out a list of members of the Foreign Office who, by virtue of their age and university background, might have been connected with the ring. Only three names provoked any reaction. And the first was Milo TALBOT (Lord Talbot of Malahide), who was remembered as a friend of Richard LLEWELLYN-DAVIES, and ‘who certainly knew all the members of the Group very well’.” Yet what the reaction was is not recorded, as if Victor and Tess had nothing really to say.

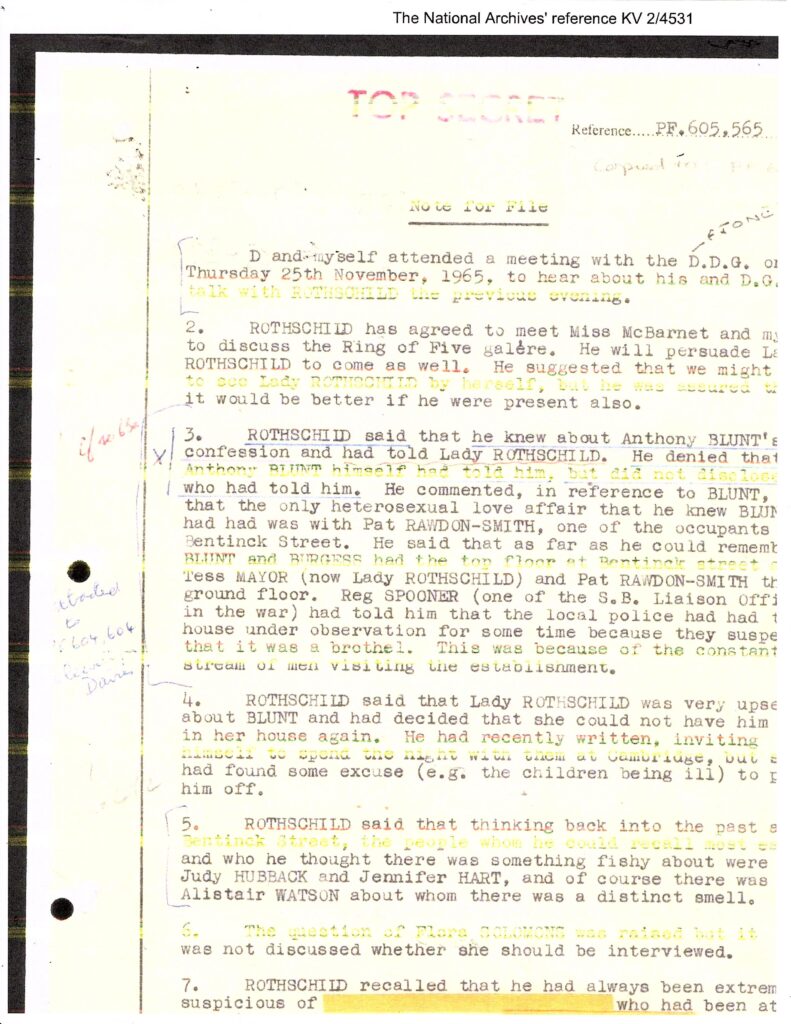

There may, however, have been a hint to Malahide the previous year. In November 1965, Rothschild was passing on names of dubious characters to Peter Wright, and admitted that ‘he had always been extremely suspicious of xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx’, a very long name redacted in KV 2/4531, sn. 49a. (See Item 7 in the image.) But why, if he had always been so suspicious of Malahide, had he not mentioned his name earlier? And why was the name redacted at this late stage in the game? And why did Peter Wright not do anything about it? William Tyrer, who has studied the complete Blunt files, let me know that Blunt had casually brought up Malahide’s name in one of his ‘interrogations’ by Peter Wright a few months beforehand, so Blunt may have warned his old friends, Tess and Victor, to be ready for any reference.

You can see what I mean. It is like a detective story. Too many dogs that did not bark in the night-time. And I continue to dive around archives and memoirs looking for clues. It never stops. I thought I had processed the Rothschild files comprehensively, taking extensive notes, but I go back, and find that there are extracts from the recorded interviews with David Footman that I had not considered significant, as well as a tantalizing reference to an anonymous person whose redacted name looks suspiciously like that of Lord Talbot de Malahide. Just count the characters. This one will run and run.

Roger Hollis in Australia

Later this year, I plan to provide a detailed analysis of Roger Hollis’s service to MI5 – including his time in Australia, where he helped set up ASIO, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation. As part of my research, I have read David Horner’s rather dry The Spycatchers; The Official History if ASIO, 1949-1963, where Hollis’s contribution is described. It presents a typical Hollisian endeavour – plodding, and with little imagination, since he recommended replicating the MI5 structure and procedures on the Australian continent, when its size and devolved political organization, as well as the nature of the Communist threat, really called out for a more inventive approach. Soon after, I started discussing Horner’s book and the story of Hollis with one or two of my Australian contacts, but was rather shocked by what I heard.

Hollis is viewed unfavourably by many influential Australians, it seems. I recall the infamous investigation by the FBI, seeded by the Australian Paul Monk, that used ‘argument-mapping’ to come to the conclusion that there was an ELLI in the heart of MI5, and that Hollis probably fitted the bill. (See https://fbistudies.com/2015/04/27/was-roger-hollis-a-british-patriot-or-soviet-spy/). Monk advertised how much he had relied on Chapman Pincher’s Treachery for extracting ‘all the salient facts about Hollis’, as well as exploiting Christopher Andrew’s Defend the Realm. If that was the extent of his research, he should have been banished from the investigation, but he nevertheless participated remotely from Melbourne. It was all a very shallow exercise, far too much influenced by the lies and distortions peddled by Pincher, but it seems to have lasted well over the ten years since it was so earnestly presented.

The reason I say that is that I was astounded by something one Australian colleague wrote to me. He had described himself as a long-time enthusiast for Misdefending the Realm, and a fan of coldspur, and we enjoyed some very cordial exchanges by email. In February of this year he introduced me to a book by a former secret intelligence officer Molly J. Oliver-Sasson, who had died last year at the age of 101. At her funeral, my contact had delivered a tribute to her (written by a friend who could not be present), and he also sent me a review by the notable intelligence author Hayden Peake of the memoir, titled More Cloak Than Dagger. (The book contains a gratuitous and out-of-place slur against Hollis, simply reproducing Pincher’s assertions.) My colleague then introduced Peake’s review by stating that ‘an unexpected bonus’ in it was ‘that he was prepared to go on the public record to describe Hollis as a “suspected Soviet agent”’.

I immediately challenged such a crass error of judgment, considering that it was undignified and unscholarly. It is one thing to harbour doubts about Hollis, but quite another to welcome some superficial analysis as confirming what I can only call a prejudice – especially from someone who was presumably familiar with my coverage of ELLI, Gouzenko, and Hollis. I wrote, very politely: “And why would you be so enthusiastic about this opinion being aired, I wonder, given that the case against Hollis has almost entirely been dismantled, with no solid evidence against him. Is the prevailing opinion in ASIO, and in Australia generally, that Hollis had been a Soviet agent?” My colleague provided me with some further information about the defector Tokaev (whom Sasson had nursed), and promised to provide more detail about Peake, and his judgment, but I have not heard from him since.

I thus took up my case with an experienced Australian in this business (who has asked to remain anonymous), asking him where the conviction that Hollis had been a traitor derived. In all seriousness he replied: “Ethnocentric bias. He was a Pom.” He went on to describe some of Hollis’s operational failings, but I was already dismayed. I told my contact that his explanation was feeble. Now, I understand some of the bias held against Britons (I have experienced it myself on business trips Down Under) because of the patronizing way some of them/us behave, but this was absurd. I can also understand that, in the Spycatcher trial, Robert Armstrong made a fool of himself in the courtroom trying to defend the indefensible actions of the Cabinet Office, and he would have provoked further Oz mockery of the typical British toff.

Yet the prime accusers of Hollis, Peter Wright and Chapman Pincher, were both members of the upper drawers of British society (although Wright’s later costumes and habits tended to undermine that status), and they should thus have been regarded with the same disdain. This pervasive judgment shows an utterly casual and sloppy attitude to what should be a serious business. Is Dick Ellis considered not to be a traitor because he was Australian-born, and thus not a Pom? But, of course, there were many Australian citizens revealed by the VENONA transcripts who, despite their presumably working-class background, and non-patrician manners, became willing and eager servants of the Soviet state. One of the criticisms given by my friend was that Hollis was too ‘impressionable’, but I could lay that accusation on a large number of the ‘thinking’ Australian public, it seems. Hollis in Australia – that would be a good idea for an opera, on the lines of Nixon in China. A great sequel to that blockbuster, Who Framed Roger Hollis?

VENONA

During my work on the investigation of Donald Maclean, I was constantly reminded of the role that the VENONA transcripts had played in his identification as the spy in the Washington Embassy, while I remained uncertain of exactly what cryptological breakthroughs had been made when. (VENONA was the program that decrypted – at least partially – a large number of messages sent between various Soviet Embassies at the end of the war, when the security of such was undermined by the reuse of One-Time-Pads by the cryptographic staff.) Indeed, it was VENONA itself that revealed that vital messages exchanged between Halifax and Churchill concerning the fate of Eastern European countries had been purloined, and then paraphrased, and that an important agent ‘G’, later expanded to ‘GOMER’ (= HOMER) had been responsible for passing them over. What civil servants reminded each other consistently at the time was the necessity of saying nothing about this source, for fear, presumably, that the Soviets would learn that their methods had been broken.

Yet I could never understand why such an attempt at secrecy was necessary. William Weisband, a linguist at Arlington Hall, had informed his Soviet masters of the project, and by 1948 the Soviets were able to undertake a total overhaul of their encryption procedures. Kim Philby also informed them of the progress made on the exercise. Yet the Foreign Office (who admitted to being controlled by MI5’s demands) stubbornly insisted that there was a security risk. As late as September 28, 1953, Talbot de Malahide (yes, he!), responding to a request by Patrick Dean as to why the Office was against releasing all our knowledge of the Maclean/Burgess affair, wrote:

The argument roughly is that it is most important to conceal from the Russians our knowledge of Bride [i.e. VENONA] material. They cannot, of course, now prevent us from extracting what we can from it. But if they knew we were doing this, they could take defensive action which would probably ruin any chance we still have of making use of the knowledge we obtain in this way. [FCO 158/126]

Dean annotated: ‘Thank you! I agree.’, thus endorsing the code of silence. Yet why Malahide and co. thought that the Soviets would not already be taking ‘defensive actions’, based on their knowledge of the exercise, rather than waiting for the British to declare to the world what they had discovered, defies explanation. Of course, those illusions would shortly be shattered by the Petrov revelations a few months later.

For some reason, American institutions also decided to try to keep the details about VENONA secret until writers like Chapman Pincher and Robert Lamphere started leaking details in the 1980s. It was not until 1995 that an admission was made, and a bi-partisan commission started releasing materials. From my study of the archives, I would conclude that the professed anxiety about admitting the VENONA programme to the public was attributable more to the embarrassment over the way that British institutions had been infiltrated, and to the decisions made about re-instituting Burgess and Maclean in prominent positions, than it was to the concern about divulging damaging secrets to the Soviets.

While there was a justifiable conviction that trying to use the transcripts themselves as evidence in any criminal trial, because of the use of cryptonyms and the lack of transparency in how the decryptions themselves had been made, it seems to me that a substantial propaganda coup could have been made by explaining the stunning achievements of the exercise. It was not that it would have alerted the Soviets: they had made the necessary adjustments as soon as they learned of the exposure. It was not like the secrecy over the ENIGMA project, and the corresponding British Type-X equipment, which had been supplied to other countries after the war, and thus might have provoked embarrassing questions. This was a once-off example of a lapse in procedure, and a spectacular effort to exploit it. Chrsitopher Andrew wrote: “The value of VENONA as a counter-espionage tool was diminished, sometimes seriously, by the extreme secrecy with which it was handled.” (Defend the Realm, p 380)

It seems to me that a fresh re-appraisal of VENONA is needed. I have been trying to work out who called the shots in that critical period between 1948 and 1951 – how much did Dick White know when Maclean returned to Britain in April 1950, for instance? MI5 was supposed to be in charge of the whole project (to the chagrin of Carey-Foster in the Security section of the Foreign Office), but several tensions existed. Sir Robert Mackenzie (ex MI6, and the Security representative at the Embassy in Washington) clearly did not appreciate receiving instructions from a greenhorn like Carey-Foster. Valentine Vivian of MI6 spread his wings, sometime misinforming his boss, ‘C’, Stewart Menzies, while communicating with his own representative, Peter Dwyer, in Washington, and busied himself investigating wartime British Security Co-ordination and retrieving missing telegrams from the Moscow Embassy. Arthur Martin, Dick White’s assistant, seemed to be working in parallel with Guy Liddell, but occasionally he and White veered off on tracks not aligned with those of the deputy director-general, while Martin communicated with MI5’s representative in Washington, Dick Thistlethwaite. Edward Travis of GCHQ was negotiating on cryptographic sharing with his counterparts at Arlington Hall, but often very secretively. And they all had to consider how to deal with the FBI, and how they could make inquiries concerning the lamentable security procedures at the Embassy without upsetting anybody, or alerting the spy (who might still be in residence) as to what they were up to.

I see a number of opportunities. First of all, a renewed attack on partially deciphered messages, using much faster computers, and probably advanced AI techniques, could surely reveal much more about the traffic and persons involved than was decrypted decades ago. Second, an integrative approach to the interpretation of information would be highly desirable since records released during the past twenty years for the Foreign Office, MI5, and GCHQ, as well as resources like the Mitrokhin Archive, would probably point to conflicting missions, and oversights in analytical opportunities. Third, much of the material that has been published has been redacted because of old sensitivities to living persons, and also contains errors or partial information that could be easily corrected based on intelligence that is now available. With the passage of time, and the deaths of such persons, such names should be restored. One of the most frustrating aspects of VENONA decrypts is that it has been impossible to determine what breakthroughs were made, when, which has complicated the task of historical interpretation.

Nigel West’s book, VENONA, and that by Haynes and Klehr, VENONA: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, were published in 2000. Defend the Realm (2009) has a decent and provocative chapter on it. Romerstein’s and Breindel’s Venona Secrets appeared in 2014, but it has a strictly American focus. Andrew’s coverage in The Secret World (2018) is shallow: he could not even find room for an entry to VENONA in his Index. John Ferris’s Behind the Enigma (2020), the history of GCHQ, is feeble. A fresh look is required. Intellectually, I would find it an appealing challenge, but much of the material is contained in undigitized GCHW (HW 15 series) files that would have to be photographed. Furthermore, I am still working my way through the Burgess and Maclean PFs, and some residual FCO files, and still have (for example) the Philby and Blunt files to work on. Ars longa, vita brevis.

Victor and Venetia (continued)

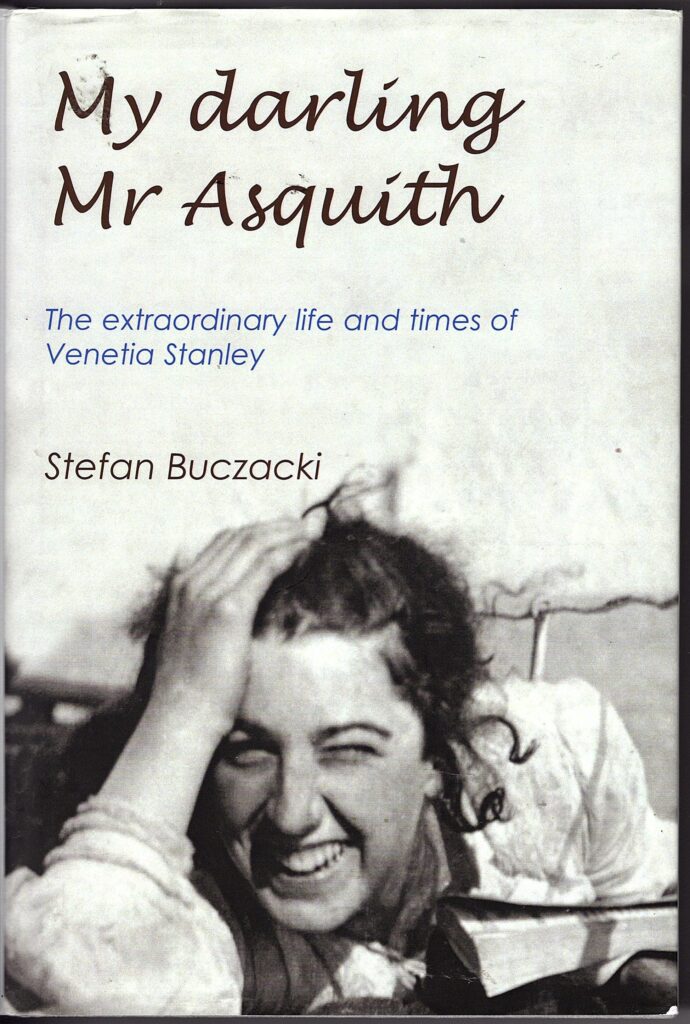

Readers may recall my investigation into the society figure, Venetia Montagu, and her dalliances with men young enough to be her son, from last December’s Round-up (see https://coldspur.com/2024-year-end-roundup/). At that time, I stated that I was not going to shell out $100 to read Stefan Buczacki’s My Darling Mr. Asquith: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Venetia Stanley in order to learn more. Well, the price came down, I acquired it, and have since read it.

I was intrigued by Mr Buczacki’s interest in this range of not very attractive aristocratic persons from the Edwardian era, and beyond. I sought to learn more about him, since it sounded as if he might have fascinating antecedents deriving from some corner of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (actually, more likely to be Poland, though borders in that region have been very fluid over the past one hundred and fifty ears). I was delighted to discover that he simply describes himself as ‘English’, but I have been unable to determine whether he comes from the Huntingdonshire or the Somerset branch of the Buczacki clan. No matter. He has written a vastly entertaining book, although his understanding of the correct use of the comma is woeful, as are his occasional lapses into ‘from whence’, and the occasional erroneous ‘whomsoever’, when ‘whosoever’ was required. And, of course, no qualified editor was around to help him.

I shimmied my way through the perverse attentions to young women of the Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, and the assortment of Wodehousian characters of whom Venetia’s set consisted – such as ‘Crinks’ Johnston, ‘Scatters’ Wilson, ‘Bongie’ Bonham-Carter – to find my way to the meat of the book, where Venetia meets Victor. Sadly, there is not much more to learn. Venetia probably met him because Victor’s father must have known Edwin Montagu, Venetia’s husband, in the Ministry of Munitions in 1916, and both were keen naturalists with an interest in East Anglian fauna (although Edwin liked to advertise his infatuation by shooting many of them). Buczacki states that Victor was at Trinity when Venetia ‘was passing through a phase of taking a sightly unorthodox interest in young research students’.

Buczacki does not believe that Venetia and Victor ever had an affair, but they remained friends, and Victor apparently took a ‘surrogate paternal interest’ in Venetia’s daughter Judy (thirteen years younger than him) after Edwin’s premature death from an infection picked up in South America. She did meet William Grey Walter through Victor, however, and he became ‘the most unlikely of all her lovers’, but, for some reason, that distinction does not merit Walter’s gaining an entry in Buczacki’s Index. Walter was just eight months older than Victor, was elected to the Apostles at the same time as Victor in 1933, and later became the Society’s secretary. “He was further to the left however and a serious fellow-traveller,” notes Buczacki, so MI5 were probably justified (to the extent that any of these surveillance activities were at all useful) in opening a file and keeping an eye on him. Isaiah Berlin met Venetia, but there is no mention of Guy Burgess or Donald Maclean, and that strange summer get-together in Cap Ferrat goes unnoticed. I tried to contact Buczacki via his website, but was put through such a hostile privacy rigmarole, being required to download some software that I did not trust, that I abandoned the idea.

I did discover, however, a reference to the sojourn in the Blunt archive, from August 27, 1969, when he was interviewed by Peter Wright and Cecil Shipp (sn. 729a in KV 2/4713). Blunt said that he was sure that the incident occurred in 1934, and that, apart from him and Burgess, the following had attended: ‘Dadie’ Rylands, Anne Barnes, Venetia Montagu, Penelope Dudley-Ward, Gerald Cuthbert, Claude Phillimore and Arthur Marshall. (Isn’t it extraordinary how reliably Blunt’s power of recall worked when it would not adversely affect him?) When Wright later jolted his memory about Grey Walter, Blunt did reflect that he might well have been in the party. He judged that Walter, also an Apostle, was an ‘extremely cold fish’, an opinion that one must assume was not shared by Venetia Montagu, whose embraces Walter was enjoying. He reinforced the laboratory link between Victor Rothschild and Walter, but did not remember him as a friend of Burgess, adding the intriguing observation that he thought ‘Burgess would have got to know him through Lettice Ramsey, whose boyfriend he had been for some time.’ History does not tell us whether Wright followed up this intriguing lead.

Car Accidents?

I mentioned earlier the suspicious circumstances in which Lord Talbot de Malahide died, and referred also to similar cases involving Harold Gibson and Herbert Skinner. When reading recently Michael Braddick’s biography of Christopher Hill, I learned that Hill and his second wife, Bridget, in August 1957 ‘were involved in a tragic car accident, in which their eleven-month-old daughter, Kate was killed’. That set my mind racing about other car accidents that had befallen Communist apostates or traitors, or their families. What about the death of George Graham’s son in 1949, in High Wycombe, when an errant wheel flew into his face? Or that of Paul Dukes, who died in South Africa in 1967, the result (according to his wife) of a serious motor accident in England the previous year? And what about Tomás Harris, who died in a mysterious motor accident in Mallorca in 1964? Nor should we forget Goronwy Rees, who almost died from a hit-and-run-accident in 1977. It seems to me that, statistically, these persons who had defied the KGB suffered an unusually high accident rate from motoring exploits.

I mention again the long list of deaths of such characters – including those who maybe simply knew too much – under other suspicious circumstances. Added to Malahide (found on a yacht with mysterious markings on his body), Skinner (found alone in a hotel room in Geneva, with symptoms of a heart attack), Gibson (found shot in his apartment), I would list the following deaths that have not been properly examined and explained:

- Humphrey Slater, died in Linea, Spain, at age 51

- George Placzek, physicist, died in Zurich in 1955‚ ‘probably a suicide’

- John Costello, journalist, died on flight to Miami in 1995

- Aileen Philby, wife of Kim, who might have committed suicide, or been murdered, in 1957

- High Gaitskell, who was diagnosed with lupus after visiting the Soviet Embassy in January 1963

- Victor Serge, who died ‘of a heart attack’ in Mexico in 1947, and whose son believed he had been poisoned by NKVD agents

- Konstantin Umansky, who died in a plane crash in 1945, cause unknown

- Victor Kravchenko, defector, who died from a gunshot wound in New York in 1966, his son believing he had been murdered

I have come across rumours affecting other premature deaths over the years, such as Alexander Kojève, Gordon Lonsdale (Molody), Alexander Foote, George Orwell even. These may simply be ‘conspiracy theories’, and easily debunked. I don’t know. And a whole host of earlier assassinations have been recorded by such as Boris Volodarsky, including (but not limited to) Miller, Serov, Kutepov, Krivitsky, Poyntz, Frunze, Agabekov, and Ryumin, as well as the famous cases like Trotsky. I noted Nikolay Zorya, found dead from a gunshot wound in his hotel room at the time of the Nuremberg trials in 1946, in an earlier coldspur. Molly Oliver-Sasson [see above] writes about the assassination attempt on the defector Tokaev, whose handler she was. I am thus sure that there were more assassinations than have been officially recognized. A project for someone else to pick up.

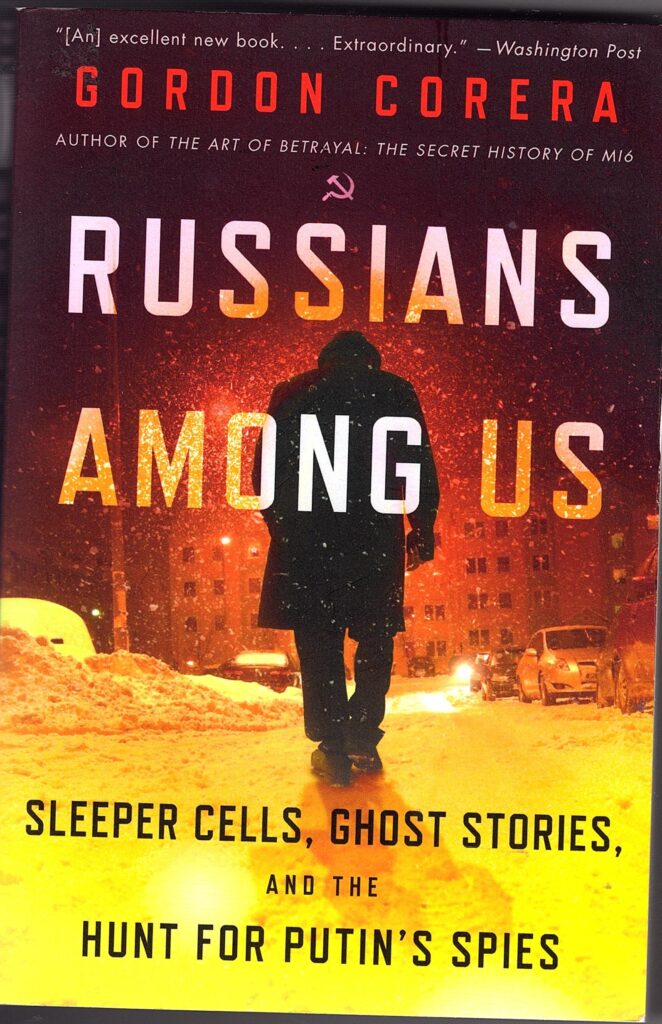

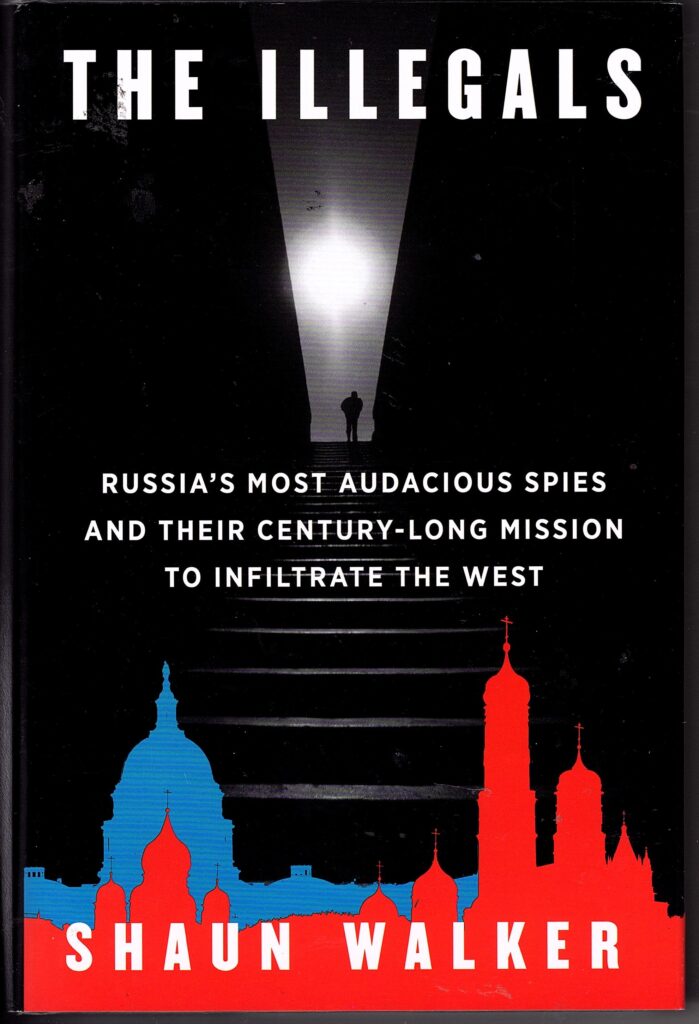

The Illegals

This spring I read two books on the Soviet-Russian ‘illegals’ programs, Russians Among Us (2020), by Gordon Corera, whom I knew through his Art of Betrayal, and The Illegals (2025) by Shaun Walker. As a reminder, the project for inserting long-term agents behind the borders of the western democracies, with false identities and ‘legends’, outside the protection of ambassadorial conventions (the ‘Illegals’), originated in the 1920s, and has continued well into Putin’s term as President of Russia. These two books take very differing approaches to updating the public, however. Corera’s book is a more journalistic effort that concentrates exclusively on the project since the dismantling of the Soviet Union in 1991. Alexander covers the same territory (and describes the actions and betrayals outlined by Corera in almost identical terms), but sets out to cover Russia’s century-long mission to infiltrate the West, as well.

Russians Among Us is more a work of its time. It contains no bibliography, and its sources are primarily reports from the press, and on-line blogs and bulletins. Corera tells a pacy story, well-crafted, with Macintyreish flair, about the Heathfields, the Murphys, and the notorious and glamorous Anne Chapman, who apparently inspired The Americans (a television series I own, but have not yet viewed). They were all betrayed to the FBI by Alexander Poteyev, who worked for the KGB, and then its successor, the SVR, and who was recruited by the Americans. Amazingly, he managed to escape just before the FBI started its arrests.

Walker is far more ambitious, setting out to describe the whole program since its inception by Meer Trilisser, born in 1883. I judge that Walker misses his mark in several ways. He offers a large bibliography, which includes the obvious work, Nigel West’s volume of the same name (1993), but fails to recognize a very important book, William E. Duff’s A Time For Spies: Theodore Stephanovich Mally and the Era of the Great Illegals (1999). Moreover he fails to cover this ‘era’ adequately. ‘Mally’ (or ‘Maly’) has no entry in his Index, and Walter Krivitsky is related to a minor footnote. He provides a chapter on the buccaneering character Bystrolyotov, but adds little new to what has already been published. It is a very disappointing coverage for anyone looking for a comprehensive and fresh approach to the subject.

Instead, Walker veers from his topic. He includes detailed coverage of an exercise from World War II, where NKVD agents were infiltrated behind German lines – but still on territory from the Soviet Union – to assassinate Wilhelm Kube, the governor of Belarus. Now, this is a gripping story – one that I had not encountered before – but the fact that the agents masqueraded as German officers in uniform does not make it an ‘illegals’ programme. Nor, by classifying the insertion into Afghanistan of a troupe of commandos to assassinate the troublesome Communist Party leader, Hafizullah Amin in 1978 as the birth of the ‘Fighting Illegals’, does the author shed any light on his core thesis. It is a muddle.

Both authors point out the drawbacks of the project as it was resuscitated in the 1990s. In the 1930s, the arrival of émigrés from Eastern Europe, bearing vague genealogies and questionable certificates, was hardly a cause for concern for the western democracies, what with the feverish ideological clashes between fascism and communism, and no obvious reason for the authorities to be on their guard against hostile penetration. And the period of the ‘great illegals’ came to an end because Stalin liquidated most of them. But it became increasingly difficult as the century wore on, with greater attention to stolen identities from gravestones, and better exchange of records between security departments.

When the program was resuscitated (with the USA especially targeted), intense energies were spent in providing watertight identities for apparently genuine citizens (normally originating in Canada). But part of this exercise meant that the illegals were a genuine married couple, living a typical American life, with a house in the suburbs – and children. That proved to be the most troublesome aspect of the arrangement, since the kids were encouraged to grow up as normal teenagers when they were being deceived by their parents, who were never supposed to reveal their true allegiance. This led to tensions when the fervent communist dad clashed with the natural interest in western delights shown by his son.

One last observation I make is that both authors appear to be tone-deaf to the possibility of the Americans running illegals in the Soviet Union – or Russia. Corera very naively attributes the lack of any such program to the obvious objection any CIA officer would have to spending decades in the country, completely ignoring the fact that attempting to live as an illegal, even if one had been born there, in totalitarian Russia would have been utterly impossible. Allen Dulles found that out the hard way (as Alexander briefly notes), but he should have worked it out before he initiated the CIA’s disastrous attempts to insert rebels into Belarus and other places in the 1950s. I also think that the authors misjudge the issue of allegiance in the twenty-first century, and why an illegals program was necessary. The illegals of the 1930s were able to recruit nationals to work for Moscow because of the ideological appeal of international communism, but once the horrors of Communism were laid bare after the war, what educated Briton (or American) would want to dedicate him- or her-self to that cause (as opposed to spying for financial reasons, or because of blackmail)? And why would Putin’s weird brand of Orthodox Christian ethno-nationalism motivate anybody outside Russia? It is no wonder that the resolve of the new illegals vacillated, with their bosses in Moscow never having any idea of exactly how they had to operate, but also fearful that they would adjust too well to their masquerades, and come to prefer the freedoms of a liberal democracy.

The project has now moved into the cyber space – a whole new game of subterfuge. For that reason, Alexander’s chapter on the ‘Virtual Illegals’ is worth reading.

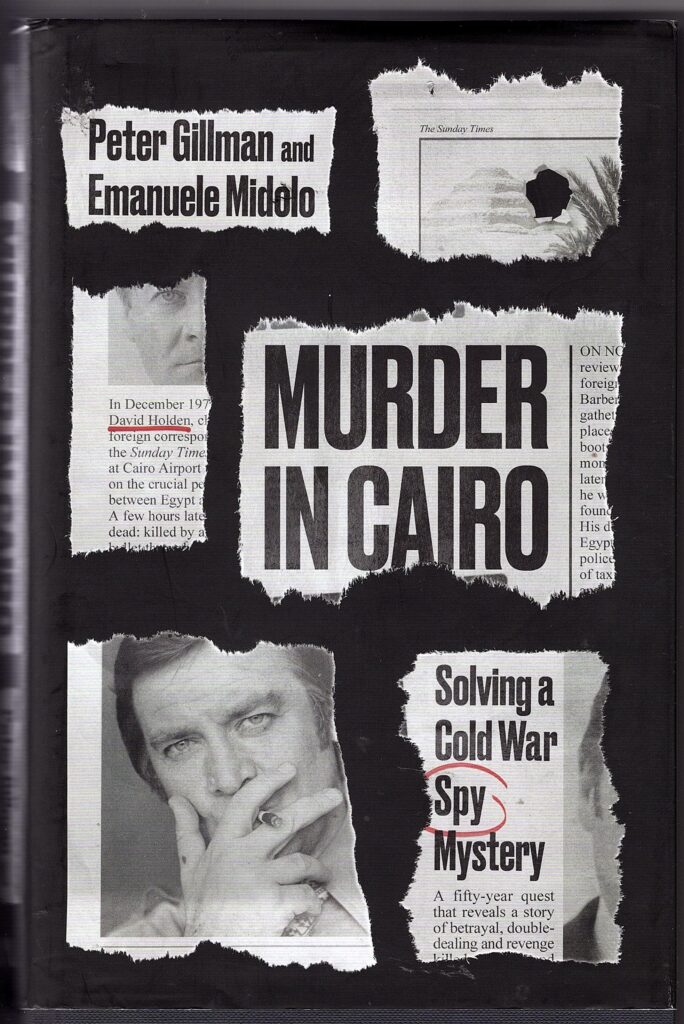

‘Murder in Cairo’

I stumbled on Murder in Cairo, by Peter Gillman and Emanuele Midolo, in a review in the TLS of May 9 by Stephen Glover. It concerned the killing of the journalist David Holden in Cairo in November 1977, and sounded intriguing. I consequently went to order it from amazon, although for some reason the book was described there as Desperate Times, by Peter Brookes, published in 2021, while the image of the cover indicated the current, correct title. Furthermore, when I tried to find it on LibraryThing with the correct ISBN, amazon likewise came up with the ‘ghost’ version (a phenomenon familiar to my colleague Andrew Malec). I thus ordered it anyway, thinking perhaps that a ‘ghost’ book might demand only a ‘ghost’ payment, and the book arrived, as Murder in Cairo, a few days later.

It comes with the conventional arresting and gushing blurbs, from such as Daniel Finkelstein, Tina Brown, and Richard J. Aldrich. Yet I wondered: did they read the same book as I did? Were they all pre-publication tributes, before they actually got round to working through it? (The back-cover did not say.) Going back to Glover’s critique, I judged it very fair. He was not unconditionally positive about the book, writing: “On finishing the book, some readers may reasonably exclaim: so what?” That was very much my reaction, as the denouement does not reflect any breakthrough analysis that was not apparent after about page 10 – that Holden was probably some kind of KGB asset, and that the CIA was somehow tied up with his assassination, and too embarrassed to discuss it.

Gillman had returned to the investigation after forty years, when Times editor Harold Evans had originally sent a crack squad to Egypt to work out what had happened. With the help of the more Internet-savvy Emanuele Midolo, he was able to discover a raft of new leads and tidbits, and to interview several more people who may have been involved (or had known, or were related to persons who had been involved, since most of the latter were dead by then). Yet they never found a smoking-gun, and the obvious questions were never answered. For what transgression had Holden been killed? And why would the murder have been carried out in such a gruesome and clumsy manner? And why then, on Holden’s first visit to Egypt for several years? And if Holden had somehow upset the applecart of Egypt-Israeli-Arab relationships (or whatever), why would the CIA have been involved in arranging the execution of a British citizen? Hadn’t other journalists done such, or worse? Even if he had been some kind of KGB agent of influence, he did not have access to confidential information, so was therefore not a spy.

The reader has to engage in a mass of tense investigation, which the authors are no doubt extremely proud of, but it involves a cast of thousands. It can be difficult to track the personalities, since the authors sometimes refer to persons by their first name, sometimes by their second, sometimes by the identity of their second (or third) marriage. Fathers and sons can be mixed up, and Gillman and Midolo provide no useful charts of organizations and relationships. The book contains references to most of the intelligence elite of the late twentieth century. For the aficionados, you will find here Kim Philby, James Angleton, Dick White, Frank Wisner, Allen Dulles, George Blake, Ralph Deakin, Archie Gibson, Edward Crankshaw, Antony Terry, Patrick Seale, Jeremy Wolfenden, Jan Morris, Peter Smolka, Phillip Knightley, Nicholas Elliott, Donald McCormick (aka Richard Deacon), Seymour Hersh, Fred Halliday, Oleg Gordievsky, Ian Fleming, Andrew Cavendish, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, Donald Maclean, and many more. The only obvious names missing were Goronwy Rees, Ursula Kuczinski, and Dame Edna Everage. (Yes, in case you asked, Ben Macintyre was interviewed.)

The problem is that, as the investigators search for ‘facts’ they come across persons who are dissembling half the time, and they do not know which half it is. The authors admit (and even boast of) this technique, inherited from the Sunday Times ‘Insight’ team, as if an accurate story could miraculously evolve from such a barrage. The impression I got from the descriptions of the actors is that a lot of unattractive people, if they were not plotting against their rivals, sat around in various watering-holes in the Middle East, getting sloshed at the tax-payers’ or their employers’ expense, while imagining that their gossiping constituted some advance in intelligence-gathering. My reaction is that Holden’s death might have been more because of what he might reveal than what he had actually written. Why he could not have been disposed of quietly, in an isolated hotel-room, with symptoms of a heart-attack, as the KGB’s Special Tasks squad would have carefully managed, is as much a puzzle as the reason for his being taken out. The assassins did not just want him killed, as retribution for his defiance or betrayal, they wanted to send a strong deterrent message. But who would have picked up any pattern? November 1977, eh? At exactly that time, Dick White was warning Andrew Boyle not to persevere with his questions about Blunt. That was a few years after Malahide met his sudden end, and a couple of years before Blunt was eventually outed . . .

As I was contemplating all these matters, I discovered Manifest Lies, a fictionalized version of the Holden case, written by Max Heaton, and published in 2024. As coldspur readers will know, I am not a fan of this particular genre. This novel is, however, quite well done, although I found the motives for Holden’s assassination far-fetched. Yet Heaton appeared to have trodden exactly the same research trails as had Gillman and Madioli, which set me wondering – who could he be, and why was he hiding behind an alias? I could find no footprint for Heaton on the Web, which was strange: moreover, the copyright notice in Manifest Lies was very odd. Perhaps Gillman was masquerading as Heaton, and, having been severely warned off publishing his real story by the CIA, had decided to write it up as fiction under an assumed name?

I took my theory to the Editor of hugejam, the publisher of Manifest Lies, first asking her whether she could tell me anything about Max Heaton. She replied promptly, saying that Heaton did not want anything about him disclosed, but she did not explicitly deny that Gillman could have been he. I thought that was provocative, as eliminating Hillman would not really have reduced the field by much. My next step, therefore, was to approach Gillman himself, and describe my interest and my hypothesis. He likewise responded promptly, energetically denying that he was Heaton.

I had a very fruitful exchange of emails after that. Gillman is a charming man, and happens to come from the same part of the world as I. We differed politely on one or two points of investigative journalism (he had read my quote from his book in my May coldspur by then), but I reinforced my view that, while the Sunday Times Insight team had performed a marvellous job in the 1960s and 1970s, too many authors today still followed the procedure of indiscriminately gathering as many ‘facts’ as they can about a case, and trying to weave a coherent story around them. Having been pointed to my website, Gillman said it was ‘terrific’, which was very gratifying. He said that he was also intrigued by the hidden identity of Max Heaton, who, he believed, had probably relied on Harold Evans’s My Paper Chase for much of his research. He also stated that he was close to homing in on him. I am hoping to meet Gillman when I come to the UK in September. (Despite the collegiality I developed with him, I have not altered my less than stellar review of the book by him and Madioli.)

Other Books Read

I present here a few thumbnail comments on other books on intelligence and history that I have read this year, and which have not been mentioned elsewhere (either in this report, or in earlier coldspur bulletins in 2025).

Red List by David Caute (2022)

Caute provides a compendium of the leftist intellectuals whom MI5 tracked in the twentieth century, rightly pointing to the enormous effort that was expended to little effect in surveilling hundreds of persons who may have been naïve, but whose influence was meagre. His work is marred by the fact that he appears to believe that all relevant information consists solely of the Personal Files released by MI5, and to show a barely concealed admiration of Stalinism and the Soviet Union. (B-)

The Mysterious Case of Rudolf Diesel by Douglas Brunt (2023)

A timely investigation of the life and mysterious death of the inventor of the diesel engine, Rudolf Diesel (1858-1913), who may have conspired with Germany’s adversaries when he saw how his technology was going to be used. Brunt has performed some innovative research, and has a lively journalistic style, but he pads out his story with too much repetition and digression. (B-)

The Traitor of Arnhem by Robert Verkalk (2025)

Verkalk’s thesis is that Anthony Blunt passed on to the Soviets information about the Arnhem operation, which they in turn gave the Germans, as a ploy to help the Red advance on Berlin. While his text contains some major errors, Verkalk presents some engagingly fresh research on the leaks of 1944. I am going to have to read this book again, very carefully, before passing full judgment, but it seems to me utterly impossible that Blunt (who did many stupid things) would have consciously leaked information to help the Germans, as he would have known that he would face the hangman’s noose if detected. Verkalk may have made some major mistakes of identification. (B)

Paris 1944 by Patrick Bishop (2024)

An original approach to telling the story of Paris’s liberation, by describing it from the standpoint of an eclectic set of observers and participants. I was drawn to this book since I enjoyed Bishop’s The Reckoning, about the Stern Gang. Perhaps a bit too much on Hemingway, for my liking, but Paris 1944 is a refreshing and informative account of an ambiguous period, frequently misrepresented, and it gives an arresting account of the summary justice that was meted out before de Gaulle applied discipline. (B+)

The Secret History of the Five Eyes by Richard Kerbaj (2022)

Be very wary of books that announce themselves as the ‘Secret History’ of anything. For if the history is published, it is no longer secret. And, if it is based on insider leaks, it may well be unreliable, and certainly will not be verifiable. Much of the material published here has been presented before, but the later chapters provide a useful compendium to information-sharing between the USA, the UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – the Five Eyes of the title. (B)

Operation Biting by Max Hastings (2024)

A typically lively and gripping account by the renowned journalist/historian of the February 1942 Bruneval raid on the French coast to steal secrets of Germany’s radar network, specifically the Wûrzburg apparatus. This story was already familiar to me from George Millar’s Bruneval Raid (1974): Hastings has dug out some fresh sources, but the overall conclusions are not new. He does quote, however, one astonishing statement made by de Gaulle to a confidant that Patrick Bishop overlooked: “Between ourselves, the Resistance is a bluff which has succeeded.” (B+)

The Strategists by Phillips Payson O’Brien (2024)

O’Brien came up with the rather absurd notion that Churchill, Stalin, Roosevelt, Mussolini and Hitler were all competent ‘strategists’, and he inspects their individual experiences in World War I to show how their expertise was developed. Yet the idea is a clunker: none of the five really understood grand strategy or military strategy, and the occasional biographical insights do not make amends for what is an ill-conceived and clumsy book. (P.S. This book received a stellar review in the TLS issue dated June 13. I do not change my opinion one iota.) (C)

The Spy Who Helped the Soviets Win Stalingrad and Kursk by Chris Jones (2025)

This book wins my award for Worst Title of the Year. Jones (who consulted me on his subject, and has some nice things to say about coldspur), has valiantly attempted a biography of Alexander Foote, the radio operator for the Lucy Spy Ring in Switzerland, who later ‘defected’ back to the British. Jones has dug out some useful facts about Foote, but offers a very uneven assessment of his life, neglecting, for example, an explanation as to why two versions of his ghosted memoir Handbook for Spies were published. (B-)

Operation Splinter Factor by Stewart Steven (1974)

Professor Haslam encouraged me to track down Operation Splinter Factor (a CIA project to foster insurgencies in Eastern Europe) in the work of Richard Deacon. I found nothing in Deacon, but discovered Steven’s journalistic work – in many ways fascinating, but not very scholarly. It offers a bibliography, but no individual references, and grossly exaggerates the role that Allen Dulles played, as well as that of the Communist dupe Noel Field. The trials and purges were more a factor of Stalin’s paranoia. (B-)

The Future Is History by Masha Gessen (2017)

An essential volume for understanding how totalitarianism returned to Russia under President Putin. The author skillfully weaves personal stories of friends caught up in the maelstrom into an account of Putin’s rise and manipulative methods. The book is probably 100 pages longer than it needed to be, and it focusses rather too much on what I shall reluctantly have to refer to as the ‘LGBTQ’ aspect of suppression, but digesting it was still a very rewarding experience. (A-)

The Determined Spy by Douglas Waller (2025)

A comprehensive biography of Frank Wisner, the obsessive and bipolar head of the CIA’s Office of Policy Coordination, who committed suicide at the age of 56. Supported by Dulles, he pursued a relentless quest for subverting Soviet influence around the world, an activity that caused much havoc, and rebounded badly on the reputation of the USA. The author spends too much space on familiar exploits (such as Guatemala and Iran, where Wisner was not closely involved), and not enough (in my estimation) on Wisner’s capacity to charm, despite his demons, and on his personal relationships – such as why persons like Isaiah Berlin and William Deakin were drawn to him. (B+)

Naples ’44 by Norman Lewis (1978)

Brilliant! I was drawn to this book by a Lewis revival presented in the TLS, encouraged by my previous analysis of Allied invasions of Italy in 1943-44, and by my vague knowledge that my father must have taken part in them. Lewis, an intelligence officer, shows that not everything the American and British forces did was valorous and heroic, and he sheds an ironic and insightful eye on the superstitions of the Neapolitans, the inherent cruelty in a society driven by vendettas, and the baleful influence of the Camorra. I even forgive this fabled writer for his ugly deployment of unrelated participles. (A)

Christopher Hill: The Life of a Radical Historian by Michael Braddick (2025)

This could have been an engaging life of the Stalinist dupe, Christopher Hill. Braddick knows the ins and outs of CP factions in the 1950s, and the trends in historiography since, and he writes tolerably well. Yet he is so much in sympathy with Hill’s Marxism that everything is reduced to ‘class’ terms – ‘bourgeois’ culture, the ‘capitalist ‘press (when there were ten competing daily newspapers in England alone!), as well, of course, as ‘the capitalist class’, sounding as if it were taken from a cartoon in Krokodil, but in truth deputising for a variegated world of free enterprise, which itself consists of a complex set of entrepreneurs, small business-owners, investors, risk-takers, losers, profiteers, managers, directors, pensioners, regulators, competitors, unions, etc. Then there is the dreary figure of Hill himself, who as his life drew to a close, admitted that he did not really understand economics, and was no longer a Stalinist, a communist, or even a Marxist. It was a shame it took him so long to work that out. (B-)

Postscript: Reading the above book prompted me to go back and re-read R.N. Carew Hunt’s The Theory and Practice of Communism (I still own my 1964 Pelican edition). Carew Hunt was an advisor to MI5, and this book was distributed to MI5 officers after the war. It drives home how utterly stupid today’s ‘marxists’ are to adhere to the absurd, ponderous, self-contradictory ramblings of someone who lived one-hundred and fifty years ago, had no clue as to how the world worked, had no imagination, and saw society only through artificial class-dominated eye-glasses.

Ethnicity

Regular readers will be familiar with my disdain for sociologists and bureaucrats who try to classify me by ‘race’ or ‘ethnicity’. I am reminded of a management training course that I attended shortly after I arrived in the USA in the summer of 1980. The shiny and very confident instructor stressed to the class that it was against the law to inquire of any job candidate what his or her race was. (Ethnicity had not really made an impression by then, Human Resource departments were still called ‘Personnel’, and employees were not yet classified as ‘associates’.) Then, twenty minutes later, he was telling us that companies had to keep track of promotions and evaluations by racial classification, in order to ensure that no discrimination was taking place. I perked up, and asked, if employers did not know what the race of each employee was, were they relying on the employees to declare their race to Personnel, and how would the department know that they were telling the truth, and how would this information be divulged to each employee’s manager? Or did Personnel make a categorization of race based on what the employee looked like? It all sounded very invidious and unscientific to me. (This is the dilemma that the French and German governments have avoided by prohibiting the collection of such data.) The instructor was speechless for several seconds. I cannot now recall how he resolved the issue.

I am always on the lookout for intellectuals who are open about debunking these absurd notions, as a way of countering the proclamations of such as Ta-Nehisi Coates, and his calls for reparations. They are of course based on marxist ideas that each of us belongs to a class, and we are either ‘oppressors’ or ‘victims’, depending on what we have inherited. The fact that amongst one’s forbears there might be imperialists and slave-traders as well as serfs and slaves appears to have escaped such analyses. I have a well-developed resistance to any methodology that attempts to package people into oppressed ‘minorities’, and Thelma, my chief Sensitivity Reader, carefully goes over my text each month to make sure that I have included a slur against at least one of such groups, and that I have not been discriminatory in insulting any particular group less than another.

Thus it was with some pleasure that I chanced on a review by Professor David Abulafia in May’s Literary Review, where his subject was Laura Spinney’s Proto: How One Ancient Language Went Global. Professor Abulafia, when discussing the spread of Indo-European languages six thousand years ago, carefully dissected the myth that migrant tribes were united by language or ‘ethnicity’, and he went on to write: “Ethnic purity is a myth and we are all mongrels.” Splendid stuff! Yet, towards the end of his review, he wrote: “She [Ms. Spinney] makes it clear that there are still mysteries about how languages spread and are adopted, and about the relationship between language and ethnicity . . .” I was dismayed. Having just dismissed the notion of ethnicity, Abulafia professed to endorse it. I had to write to him for an explanation.

His response was prompt and charming. He apologized for the fact that the exigences of a short book review imposed simplifications of an argument, and he explained that his comment about ethnicity and language related to the lack of congruence between the origins of a tribe and the origins, real or imagined, of a language. We enjoyed a brief exchange where we agreed that many persons, encouraged by these experts to mix up ‘ethnicity’ with ‘identity’ (two notions at cross-purposes) often very selectively picked which one of their forebears they regarded as dominant in their ‘ethnicity’, and were taken in by the false notion that such culture was inherited, or ‘in their DNA’. The Professor signed off by stating that he was once asked by the British Academy to indicate his ethnicity after a public lecture he had attended, and he wrote down that he was a Martian. I (who once declared on a USA government form that I was a ‘South Sea Islander’) responded that the Academy probably paid somebody to check whether it was attracting a ‘diverse’ enough audience. Not enough Venusians, perhaps. Thank you, Professor! A true mensch.

And then I read, in The New York Review of Books (June 26), a review of a book titled Proust: A Jewish Way by Maurice Samuels, who wrote: “The debate over Proust’s relation to his Jewish identity ultimately turns not just on his personal attachments but on how he represents Jewish characters in his novel.” No it does not, Maurice! Proust’s father was a Catholic who insisted that Marcel was baptised at birth! So he could hardly have a Jewish identity, could he? Your so-called debate is completely artificial. Zut alors!