(For those readers who have expressed interest in the disposal of my Library I should like to draw your attention to the following press release, issued by the University of North Carolina on February 6: https://giving.uncw.edu/stories/new-special-collection-to-make-randall-library-a-destination-for-researchers-worldwide.)

The first two chapters of ‘The Airmen Who Died Twice’ can be seen at https://coldspur.com/special-bulletin-the-airmen-who-died-twice-part-1/.

Chapter 3: The RAF in Yagodnik

When the decision to launch the attack from Soviet soil was made at this late stage, on 11th September, the security questions raised in April 1943 were sadly overlooked. Bomber Command (or whoever was calling the shots) was apparently able to take the final decision without further consultations with the Soviet Air Force. Amazingly, approval for this revised plan must have been received immediately. It is probable that Stalin now encouraged it, as it would enable him to lay his hands upon the Tallboy itself, and not simply bombers with empty payloads, as well as to exploit the homeward flight of a Lancaster for his own devious purposes. It is certain that an agreement in principle had been hammered out some time beforehand, but that Stalin had wanted to wait until the Warsaw Uprising had been quashed before granting permission.

Preparations for the refined operation were very hurried. One significant outcome of the new arrangement was that, on that same day, 11th September, the Lancasters flew directly from Bardney and Woodhall Spa in Lincolnshire to Yagodnik, while the Liberators (which were originally scheduled to arrive in an advance party to prepare for the Lancasters’ arrival) proceeded to Lossiemouth, and then Unst in the Shetlands, for re-fuelling. This was to have serious implications when one third of the Lancasters lost their way in looking for Yagodnik. One of the reasons that the Liberators were originally supposed to arrive before the Lancasters was to provide improved VHF radio guidance, and the reliance on confusing Soviet signals and beacons certainly contributed to the errant landings and resultant written off aircraft. Moreover, the weather in Yagodnik was, in McMullen’s words, ‘appalling’. Whatever forecast had been issued from London was completely off the mark, and the Soviets (who had surely provided the forecasts themselves, and in fact given one for the day after the arrivals) were amazed that the planes had attempted the journey in such conditions.

Thus, ironically, while the ground-rules of the Operational Order had been ostensibly changed because of unfavourable weather forecasts for Altenfjord, the whole mission was jeopardized because of a failure to predict very poor weather in Archangel, the error in not implementing proper communications and signalling protocols, and the delay in sending out the Liberators which were intended to guide and welcome the Lancasters to Yagodnik. It all comprises an extraordinarily incompetent example of leadership and decision-making. One might suspect, nevertheless, that the Soviets were not too concerned about the safe arrival of all the planes. After all, there was valuable new technology to be inspected and exploited. In the developing saga of the disaster at Nesbyen, the immobility of some grounded aircraft in the swamps and forests around Archangel would turn out to have dire and unexpected consequences.

Group Captain McMullen, in his report following Paravane, stated that atrocious weather conditions from the Finnish border, incompatible call signals between Russian and English alphabets, lack of WT beacon information, and maps without towns or railways led to the scattering of one third of the planes of Squadrons 9 and 617 on arrival in Russia. Only twenty-three Lancasters, one Liberator, and one Mosquito, from a total of thirty-nine aircraft, landed safely at Yagodnik on 11th September. The remaining fourteen planes and forty-two Lancaster crewmen, with their hi-tech munitions, crash landed or were diverted to Kergostov, Vascova and Onega. These became the object of a frantic Anglo/Soviet search and rescue operation on September 12. One of the pilots added that lack of fuel was a major cause for these forced landings. McMullen did not mention this factor in his report.

In spite of the lack of English-speaking Russians or RAF interpreters there was a concerted and effective drive to locate and retrieve the fourteen lost planes and crews. Soviet efforts are illustrated by the parachutist who was dropped by one crash-site and then guided the crew to a lake where it was collected by a Soviet flying boat for return to Yagodnik. Squadron Leader Harman noted in the official diary: “We were very fortunate that we have no casualties”. All forty-two RAF crew were safely returned to their Squadrons within forty-eight hours. McMullen and his Soviet counterpart Colonel Loginov worked closely to coordinate the rescue so that, by 14th September, twenty Lancasters with Tallboys, six Lancasters with Johnny Walkers, one Mosquito film unit and both Liberators were in place at Yagodnik ready for the assault on Tirpitz.

McMullen made clear that very few of the expected facilities to ensure a successful mission were in place on site. The essential refuelling was limited by bowser numbers and capacity to 6 x 350 gallons instead of the 8 x 3,500 gallons and 4 x 2,000 gallons expected. As a result, the Squadron was not ready to fly for another twenty-four hours, delaying action until 14th September. It is almost an understatement when he asserted: “Misleading intelligence of this kind can be most embarrassing and can even ruin all chances of success”. What is not clear is whether he was blaming British 30 Mission in Moscow, 5 Group in UK, or the Soviet authorities at Yagodnik for the misinformation supplied to Squadrons 9 and 617 before 11th September. He concluded that close cooperation with 30 Mission was essential to operate in Russia, implying that this had not been a priority for 5 Group in the UK.

Ralph Cochrane, Air Vice Marshal at 5 Group Headquarters, Swinderby was responsible for coordinating the Squadrons for Paravane, reporting to Arthur Harris, Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command. Cochrane had no doubt that the careful work of his planning staff at 5 Group was responsible for the success of the operation, as he declared to Harris on 15th October. He acknowledged none of the practical problems which plagued McMullen in Russia nor why basic technical coordination with the Russians essential for navigation was not prepared by his planning staff and communicated to the crews.

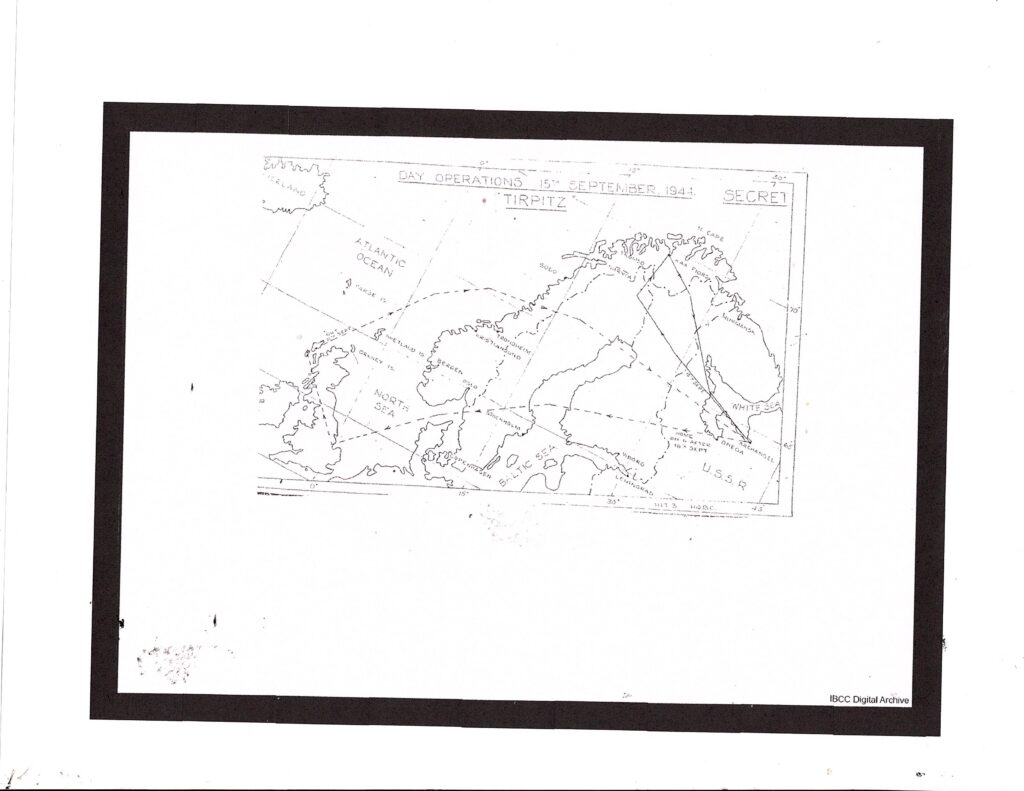

On the 15th September at 9.30 am, over a twenty-three minute period, twenty-six Lancasters and one Mosquito took off to attack the Tirpitz in Altenfjord. They flew at 1,000 feet until they reached the Finnish border, when an altitude of 12,000-14,000 feet was maintained over Norway. Within sixty miles of the target all planes, in four waves, would dive to bombing height to despatch their Tallboy and Johnny Walker bombs. Flak was intense from shore and ship, but it was ineffective. There was no German fighter plane opposition. Although surprise was achieved by using the southerly approach against Tirpitz, the smokescreen to hide the battleship was in place within seven minutes of the RAF arrival.

In the debriefing after the attack the crews confirmed that one of the seventeen Tallboys had hit the target: sixteen did not. The outcome from the deployment of the Johnny Walker bombs designed to target the hull of the ship ‘walking’ through the sea was uncertain. At 18.20 the battleship remained afloat. The Mosquito film crew was not able to secure a damage report until 20th September: it appeared to show a possible hit. The disappointing result was heightened by the knowledge that Tallboy and the SABS (Stabilized Automatic Bomb Sight) were radically new weapons designed to be accurate within a hundred yards and to destroy any obstacle. Only Squadron 617 was equipped to deliver the 12,000 lb. rotating bomb guided by computerized SABS at 715 mph, which detonated only from inside the target. On 15th October Cochrane told Harris: “None but the heaviest and strongest type of bomb could penetrate (Tirpitz’s) horizontal armour and burst within the ship.”

With the safe return of all Lancasters late on 15th September from Altenfjord, McMullen had two priorities: first, the refuelling and repair of the planes for return to the UK and active duties over Germany, and second, the salvage of the munitions scattered across the region. By 19th September Thomas Williams, assistant Chief of Air Staff, was anxiously demanding information from Harris and Cochrane on radar equipment, gun sights and bomb sights on board the Lancasters that had crashed on arrival on in Russia. A systematic campaign was launched by RAF to salvage or destroy any technology which their Russian hosts might be keen to acquire, although the RAF remained awkwardly reliant on Russian aircraft to reach the remote wrecks.

By the 20th September the chief engineer reported that all fuses and detonators had been removed from the remaining Tallboys and returned to the UK. McMullen was under instruction to retrieve everything of value from the wrecks. Despite Williams’s concern that the Russians would not allow retrieval of the Tallboys, 30 Mission was able to confirm their safe shipment to the UK on 3rd November. As a Soviet engineer wryly observed of his RAF allies: “The British dismantled or destroyed radars, radio stations, bombsights. All aircraft were stripped of the most scarce power units.” The limits of Anglo-Soviet military cooperation were clear.

The enthusiastic cooperation leading to the Tirpitz attack was replaced by growing strains between both sides. Squadron Leader Harman’s official diary charted this tortuous breakdown. On 18th September McMullen secured agreement from Loginov for the use of the Russian Dakota to inspect crashes at Belomorsk and Vascova. On the 19th September the plane was suddenly not available. Finally, on 20th September, ‘after a lot of pressure had been put on the Russians’, McMullen was able to visit the sites. When, however, a repeat exercise was attempted on 24th September with the RAF Mosquito, fuel was denied by the Russians. While thirty Lancasters, with one exception, had returned safely to the UK by 17th September; the Liberators loaded with the salvaged equipment were trapped at Yagodnik as the weather deteriorated. McMullen tried to secure Russian permission on 22nd and 24th September to fly south via Moscow to escape the northern storms: this was refused. At one point Harman despaired at the prospect of spending the winter in Russia.

Was this Russian recalcitrance due to disappointment at the apparent failure of the RAF attack on Tirpitz? Had the Russians become angry that the British were so determined to deny them access to the Tallboy and SABS technology? A report on 5th October by Mikhail Ryumin, head of SMERSH Secret Police in Archangel to his Moscow Head Office provides a clue. Describing the activities of Flight Lieutenant Abercrombie seconded from 30 Mission Moscow ‘who sought permission to take photographs as he pleases’, he added that he ‘persistently asked where the radio and power stations are located in Archangel.’, while his colleague Wing Commander Hughes was carefully recording the size and state of various Russian airfields.

If this British research was simply practical preparation for Paravane a secret Appendix in the 15th October report to Cochrane appears to confirm the Secret Police’s worst fears: “Some details regarding North Russian Airfields were obtainable but it was not possible to get much information from the Russians without arousing their suspicions. For instance it is rumoured that a very big airfield is being constructed near Molotovsk, and during a flight from Yagodnik to Belomorsk the Russian pilot could not be induced to get off track to permit one to see this rumoured airfield.” This was the same flight which McMullen and Hughes took on 20th September in the Russian Dakota to inspect the Lancaster crashes.

Group Captain McMullen was at the centre of this swirling confusion of military cooperation and political subterfuge. His praise for the Russian military was generous. “They gave full and free cooperation in every respect”, he wrote, which contradicted Harman’s meticulous record of Russian obstruction from 17th September. McMullen blamed ‘misleading intelligence’ for almost ruining the Operation, much of which originated from the Russian sources at Yagodnik. His official final letter to Russian commanders and Yagodnik ground staff was glowingly uncritical: “Your cooperation enabled us to gather the force sent to attack the Tirpitz. For that we shall always be in your debt.” On the other hand, in private to Cochrane, he conceded: “The praise in the letters is lavish, but I was advised that the Russians value this kind of thing.”

Yet a man who tacked his position to suit the audience of the moment was adamant on one point: he strongly recommended to Cochrane that Colonel Loginov, Major General Dyzmba and Vice Admiral Pantaleyev be awarded the highest British honours for their service to the RAF in Yagodnik. Although Cochrane was silent on this point in his report to Harris, the Foreign Office obliged with CB and CBE honours to all three Russians. We can only surmise whether this repayment for the debt that McMullen confirms he owes his hosts was given freely or under duress.

On 27th September the two Liberators finally left Yagodnik, eleven days after the attack on Tirpitz and the subsequent mysterious crash of Lancaster PB416 in southern Norway.

Chapter 4: The Crash at Saupeset

At about 5:15 pm on 16th September, 1944, the first group of sixteen Lancaster bombers, with a total of a hundred and thirty-one crew, took off over a two-hour period to return to the UK, over the airspace of neutral Sweden, avoiding occupied Norway. Each plane, which normally had a crew of seven, was carrying extra passengers because of the disabled planes that had had to be left behind. Leading the group, Wing Commander Tait confirmed his safe return to the UK at 1:39 am on September 17, after a fair-weather flight. All the other planes returned safely, except the Lancaster piloted by Frank Levy, PB416.

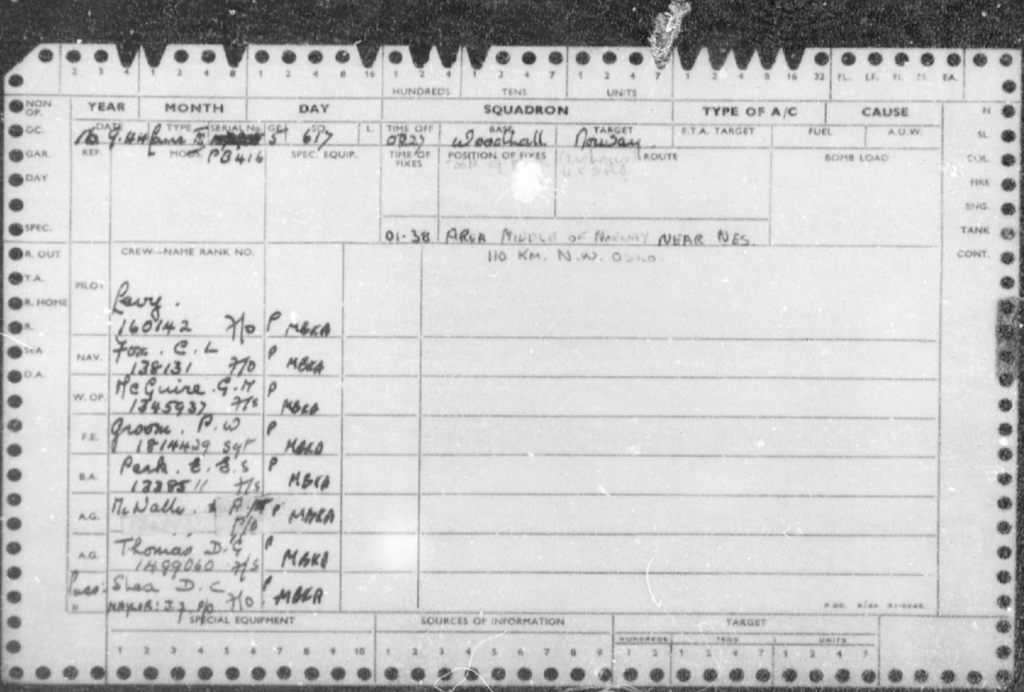

At 5.20 pm the following day, Group Commander McMullen, on temporary assignment in Yagodnik, near Archangel, sent a Top Secret WT (wireless transmission) concerning the disappearance of Lancaster PB416, assumed missing, to Ralph Cochrane, Commander of 5 Group, to Sir Arthur Harris, Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command, to Sir Thomas Williams, Assistant Chief of Air Staff at the Air Ministry in Whitehall, and to the 30 Mission in Moscow. It ran: “Following were crew of Victor 617 Squadron: Levy, Groom, Fox, Peckham, McGuire, McNally, Thomas, Naylor, Shea.” McMullen was responsible for the overall organisation of Operation PARAVANE, the air assault on the German battleship Tirpitz, from the airbase at Yagodnik, including liaison with his immediate RAF commanders in the UK, Cochrane and Harris. He also reported to Williams at the Air Ministry in London, who was responsible for defining operational requirements, and to 30 Mission Moscow. 30 Mission coordinated the project with the Soviet armed forces as well as with the British base at Archangel across the river Dvina from Yagodnik.

In the ORB (Operations Record Book) entry from the end of September Squadron Leader Tait stated: “This aircraft was lost on the return from Yagodnik to base on 17/9/44. An acknowledgement for a QDF (map location fix) from Dyce was received at 0121 GMT. Nothing else was heard from this aircraft.” Willie Tait had recently been promoted commander of No 617 Squadron that had achieved fame for its ‘bouncing bomb’ raids against the Möhne and Edersee dams in 1943. He held responsibility for the attack on the battleship Tirpitz launched by the RAF squadrons at Yagodnik. At 15.05 on 17th September Squadron Leader Harman had confirmed the coordinates of the QDF request from PB416 in the Squadron Diary as 60 50 North 009 45 East. Harman was both a Squadron Leader and Acting Adjutant for Operation PARAVANE. In the latter role he compiled a daily diary of the Operation, which was supplied to Group Commander McMullen.

The QDF coordinates refer to Oystogo, in southern Norway, a remote hamlet in a grassy valley with steep mountains on two sides. The river Etna runs through the valley. It is about fifty miles from Saupeset where Lancaster PB416 crashed, three-hundred-and-thirty miles off course from the rest of the group of sixteen Lancasters returning to the UK. The RAF Flight Loss Card for PB416 confirmed the crash location as lying approximately 110 km north-west of Oslo at about 0138 GMT. Nine crewmen were shown on board, the same as the details on McMullen’s wireless telegram.

It is both curious and provocative that Norway was identified as the target. There was no indication that this aircraft had been engaged in Operation PARAVANE and was supposed to be flying home from Yagodnik. In general RAF records present specific, functional, and accurate data. The clerk who completed the Loss Card would have used information provided by RAF No 617 Squadron. This is the only known official record confirming Norway as PB416’s target for this date, and it was clearly not considered a problem to state the target as Norway so soon after the crash. In other words, PB416 was meant to be over Norway and had confirmed its target by the transmission of its coordinates, over Oystogo, to RAF Dyce Aberdeen. By this reckoning the location of PB416 was not an accident: it had reached its target by 0121 GMT on 17th September and confirmed the same to the RAF base in the UK.

On 15th October Cochrane confirmed to Harris: “With the exception of one aircraft which is presumed to have crashed in Norway all aircraft in Russia less the six which could not be repaired had arrived back in this country by September 28th”. The site of the crash is well documented. At a height of about 3,500 feet, Saupeset is a steeply wooded ridge overlooking a valley with the village of Nesbyen below. Saupeset is used for summer pasture with few human inhabitants. A Lancaster bomber exploding on impact with at least one third of its fuel unused would have been a colossal shock to the remote rural scene. In the days following, a shallow mass grave was dug in the rocky ground close by the crash, most probably by local residents from Nesbyen. No names were permitted to be recorded by the German authorities, whose Gestapo Headquarters at Gol was about ten miles away. With active Norwegian Resistance from Milorg in the Hallingdal area the Germans were determined to minimise any boost to local morale which this unexpected British Lancaster might have supported. In spite of the Germans, the local Norwegians erected a simple wooden cross with ten nails to represent the ten bodies they had buried.

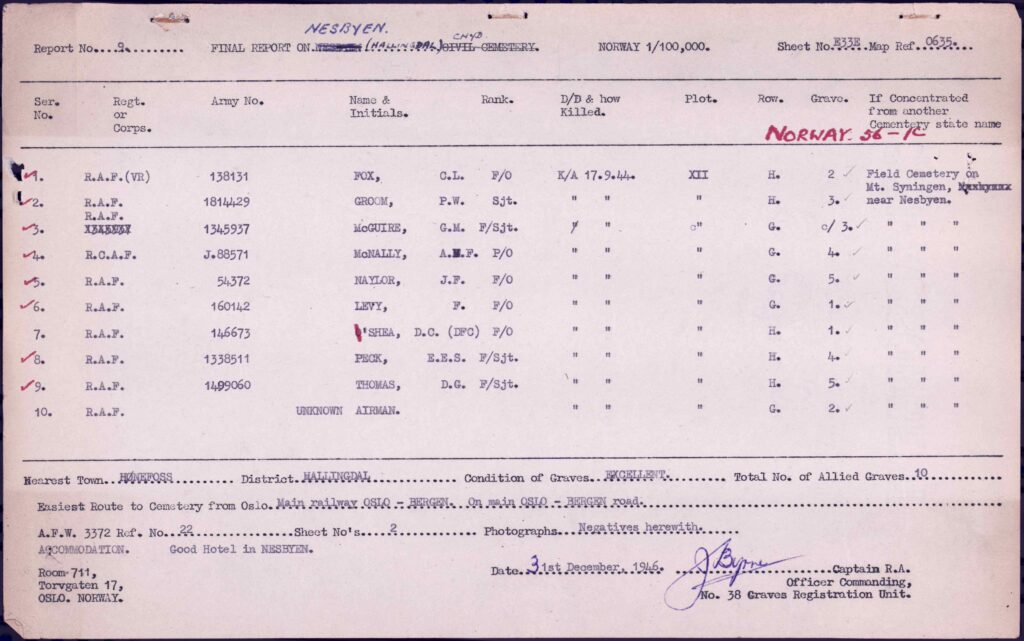

The next official document to appear was the initial registration made by the GRU (Grave Registration Unit) on 24th July 1945, two months after the German surrender in Europe. This was the first stage of the task of the War Graves Commission, namely to identify graves, reconcile names of casualties and where required prepare reburial to a designated military cemetery. This July registration by Captain Byrne confirmed eleven bodies as casualties of the crash of PB416. Strangely the same document was amended on 22nd August 1945 by Captain Byrne to show only nine bodies, which of course tallies with the RAF Crash Card from September 1944. The two names deleted in August from the initial July register were Squadron Leader Wyness and Flight Lieutenant Williams.

It is puzzling why there should have been such confusion over the most simple of tasks, namely confirming the number of crew on board a Lancaster departing the Soviet Union and determining the number of bodies found at the crash site of the same plane on a remote mountain in Norway. The evidence is moreover contradictory. One clue was an unofficial memorial panel, hand painted with Norwegian text, which was installed at the crash site. According to local sources it was attached to the cross with ten nails as soon as the Germans had retreated from the area in May 1945. The panel confirmed ten RAF crew as casualties, including Williams and Wyness. These were the same airmen who were included on the British GRU report in July and then deleted in August 1945. Curiously the Norwegian panel omits Flight Sergeant McGuire, who is included in all RAF and GRU records. If McGuire’s name had been added to the Norwegian memorial panel in May 1945, the total number of casualties would have been eleven.

The Norwegian list was based on the physical identity of the casualties before burial in September 1944. Their names were confirmed by the ‘dog tags’ worn on the wrist and the ID on each serviceman’s uniform. A severe crash and explosion might have made verification of bodies difficult, but the Norwegian panel confirms the clear identity of ten airmen, with the exception of McGuire, which tallies exactly with the same ten names in the GRU report in July. This implies that the ‘dog tags’ were readable on ten bodies. This assessment further suggests that the initial British GRU list in July 1945 was based both on RAF records and cross referenced with local Norwegian records including the memorial panel. Otherwise the names of Williams and Wyness would not have been included. It is unlikely that the mass grave on Saupeset was exhumed by the British in July 1945, since the fact that McGuire’s ID was missing would otherwise have been questioned by Captain Byrne in his report to the RAF. The question must be asked: Why did Captain Byrne delete Williams and Wyness from the GRU list on 22nd August 1945? The reason is that, although the ‘dog tags’ and uniforms of these two airmen were found at the crash site, these two officers were not on flight PB416 from Yagodnik.

The Squadron records show Williams was hospitalized at Yagodnik with severe dysentery on 16th September when PB416 took off. (Perhaps that is the reason his uniform was ‘borrowed’). Wyness did indeed leave Yagodnik with the sixteen Lancasters on 16th September, but as a passenger on Flight Lieutenant Iveson’s Lancaster ME554, which landed safely in the UK at 0124 GMT on 17th September. (Wyness’ own plane had crashed on landing on 11th September and was abandoned in the Soviet Union.) But both the Norwegian memorial and July 24th GRU record confirm the identities of Williams and Wyness at the crash site. If Williams and Wyness were not on board PB416 on 16th September, who, then, were wearing their uniforms and IDs when the plane crashed at Saupeset?

We know for certain that Williams and Wyness were not passengers. Their fate was one shared by many brave airmen who served their country and flew with Bomber Command. Together with six other Lancasters of 617 Squadron, on a mission to bomb the Kembs barrier on the river Rhine, their plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire and crashed at Rheinweiler, Germany on 7th October 1944. Although they successfully bailed out before impact, they were captured by German troops and executed, in breach of the Geneva Convention for the treatment of prisoners-of-war. Wyness, aged 24, the pilot, was buried at Choloy, in France and Williams, aged 22, was buried in the Dürnbach Cemetery, in Germany.

By 1946, further notifications in the record had been made. The Grave Registration document early that year shows ten allocated graves in the cemetery, one of which, XII G2, has been left blank and is later overtyped, “UNKNOWN BRITISH AIRMAN 17.9.44”. This document confirms the reburial of the bodies from the top of Saupeset to individual graves in the church yard below. These details were reconfirmed in the Graves Concentration Report of 9th August 1946. The record now states that ten bodies had been transferred from Saupeset and re-interred at Nesbyen, with nine names matching those in the RAF Crash report plus one ‘unknown British airman’. McGuire was included: Wyness and Williams had been withdrawn. The resolution thus appears to reflect faithfully the RAF Flight Loss Card, perhaps ascribing the extra body to a clerical oversight.

When asked about the inconsistency of GRU and RAF records for PB416 the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) confirmed that all data was based on the lists supplied by the Germans at the time of the initial burial, forwarded to the Red Cross and subsequently to the RAF. When the Red Cross and International Red Cross were requested, however, for their record of the accident, both confirmed that they had no information of either the crash or any of the casualties at Saupeset on 17th September 1944. When asked about the Norwegian memorial from May 1945 the CWGC said they had no knowledge of its existence.

So why did the first GRU report of July 1945 include Williams and Wyness, while RAF records did not? The implication is that Captain Byrne of the GRU, on the first British visit to the crash site, took the details he had been given from the RAF crash card, which showed the nine names. On discovering the new names of Wyness and Williams from the local Norwegian memorial, he simply added them to give a total of eleven casualties. Yet McMullen was clearly aware that Williams and Wyness were not on board PB416 on 16th September and knew that they had become casualties in Germany on 7th October 1944, not in Norway. After submitting his list of eleven names to RAF on 24th July 1945, Byrne was surely advised to delete the names of Williams and Wyness, which he did on 22nd August. This left a total of nine casualties, consistent with the RAF version, but not with the Norwegian memorial that showed they had buried ten bodies, with ten readable ID tags, the year before. That may explain the need for the addition of the ‘unknown British airman’ for the reburial in March 1946 to bring the total number of graves at Nesbyen to ten.

How could one set of IDs been lost? PB416 was carrying approximately 800 gallons of fuel on impact, so it is quite possible that the eleventh body was so badly burned in the crash that the airman’s ID was unrecognizable. This probably explains why McGuire’s name was missing from the Norwegian memorial panel. Yet the lack of any process to reconcile differences is disturbing. When the RAF received Byrne’s report of 11 bodies at the mass grave on 24th July 1945 it was the first time that McMullen’s account of nine casualties on PB416 had been challenged. McMullen was still Commander at RAF Bardney at this time, and he was presumably a difficult man to challenge. His list of nine RAF airmen was partially accurate, but he had omitted the identity and existence of the two passengers who must have been wearing the uniforms of Williams and Wyness, which brought the true total of people on board PB416 to eleven.

A local story has circulated in Nesbyen that, after the first British inspection in July 1945, a transportation was arranged by British troops with local assistance to move one body from the Saupeset grave to the British Embassy in Oslo. If the story is true it aligns with RAF instructions to Byrne in August 1945 to reduce the number of identifiable casualties in the report from eleven to nine, while honoring the Norwegian memorial, with its count of ten. Unlike the GRU, the RAF and McMullen were aware of the number of people who boarded PB416 at Yagodnik on 16th September, 1944, and that by physically removing one casualty from the mass grave this would leave ten bodies on Saupeset. The RAF had to admit that Wyness and Williams had not been on the flight, because of subsequent events, but they had to bury the fact that their uniforms and IDs had been borrowed by unnamed passengers and had been found at the crash site. The final step in adjusting the body count was made public in March 1946 when the casualties were reburied at Nesbyen, ready for visits by families from the UK. A tenth body was now added to the adjusted GRU reports in March, confirmed in August 1946 and designated ‘Unknown British Airman’. It is certain that McMullen was aware that the tenth and eleventh bodies were neither RAF nor British: hence there was little risk of their families being aware that the GRU or the RAF had been involved with the burial of foreign servicemen in a British War Cemetery in a remote part of Norway.

This total perfectly aligned with the 10 new gravestones in Nesbyen cemetery for the ten bodies brought down from Saupeset in Spring 1946. It is likely that the instruction for this change by GRU was made and approved by the RAF in line with previous changes by the GRU. If the eleventh body was transported to the British Embassy in summer 1945 it would have required an order from the RAF and official sanction from the Foreign Office in London. Yet, by making one body physically disappear to the British Embassy in 1945, and the second body being made anonymous as ‘Unknown British Airman’ in 1946, it was as though the two persons wearing the uniforms of Williams and Wyness had never existed and certainly could not be traced.

But they did exist. What next has to be investigated are the questions of who might have been wearing the uniforms belonging to Williams and Wyness, why they were on board an RAF Lancaster three-hundred-and-thirty miles off route in Southern Norway, and why the RAF, the CWGC and local Norwegians still prefer not to discuss the matter. For they were certainly Soviet agents authorized at the highest level to be flown on a secret mission to Norway.