Preface:

This Special Bulletin consists of the first two chapters of a report ‘The Airmen Who Died Twice’, the culmination of a project to investigate a mysterious airplane crash in Norway in September 1944. The events were first described in June 2022 on this website at https://coldspur.com/special-bulletin-the-airmen-who-died-twice/. The complete article contains eight chapters: I shall publish two more in each of the following three months. In that way, the full account shall be available for the British authorities to respond to in time for the solemn eightieth anniversary of the crash of PB416 at Saupeset in Norway on September 17, 2024. I believe the relatives of those crew members killed in the accident deserve a proper apology for the deception and attempt at a cover-up that quickly followed the incident.

I want to give full credit to the role that my collaborator, Nigel Austin, played in this research project. The original idea was his. He discovered some traces of the clumsily muddled story, and uniquely identified the contradictions in what little archival material existed. He then doggedly chased down resources and spokespersons for various organizations that were involved. He contacted me for assistance in providing some method and structure to his endeavour, and I was gripped enough by the drama and paradoxes in his outline to want to work with him. Unfortunately, some personal problems prevented Nigel from completing his side of our agreement, and I decided to take over the project before the details escaped from my overtaxed brain. I thus performed some original research on my own, and also turned Nigel’s observations into a narrative that I hope both instructs and explains. I also believed that it was very important that the story be published well before the eightieth anniversary, and, since no commitment from any historical magazine had been secured in time, I decided to use coldspur as the medium.

Readers will notice that the report lacks any Footnotes. I took this approach in order to broaden the appeal of the text. However, I believe that the narrative is adequately sprinkled with references that will convince readers of the scholarly nature of the investigation. Sources can be supplied, and I shall list them separately, later. On the other hand, many of the communications that must have occurred are not traceable, and probably never will be. That is in the nature of highly confidential government undertakings. Thus the work is a hypothesis lacking firm proofs, but offering enough credible evidence to provide as watertight an argument as can be expected. I hope that, through the publication of these eight chapters, readers around the globe may be prompted to discover and present fresh memoirs, letters, or other documents that will flesh out the story. Or, of course, blow it apart. Because historiography is never finished.

Appearing here on February 15: Chapter 3 (‘The RAF in Yagodnik’) and Chapter 4 (‘The Crash at Saupeset’). Enter the date in your calendar now! And, if you have observations or details to add to the story, please send them to me at antonypercy@aol.com.

Chapter 1: Introduction and Historical Background

The saga of ‘The Airmen Who Died Twice’ is a story about a rash deviation from a serious World War II aerial operation that went horribly wrong. It is a tale about hazardous decisions made under pressure, in a climate of tensions across political, geographical, linguistic, cultural and temporal boundaries. It contains aspects of deep secrecy, betrayal, deception and self-delusion, and has ever since remained a mystery to most British government officials who have had to deal with its legacy. And, above all, it is a story of sacrifice, of brave young men who, having committed to risk their lives in genuine opposition to a real enemy, perished in an unnecessary and highly risky enterprise that should never have seen the light of day.

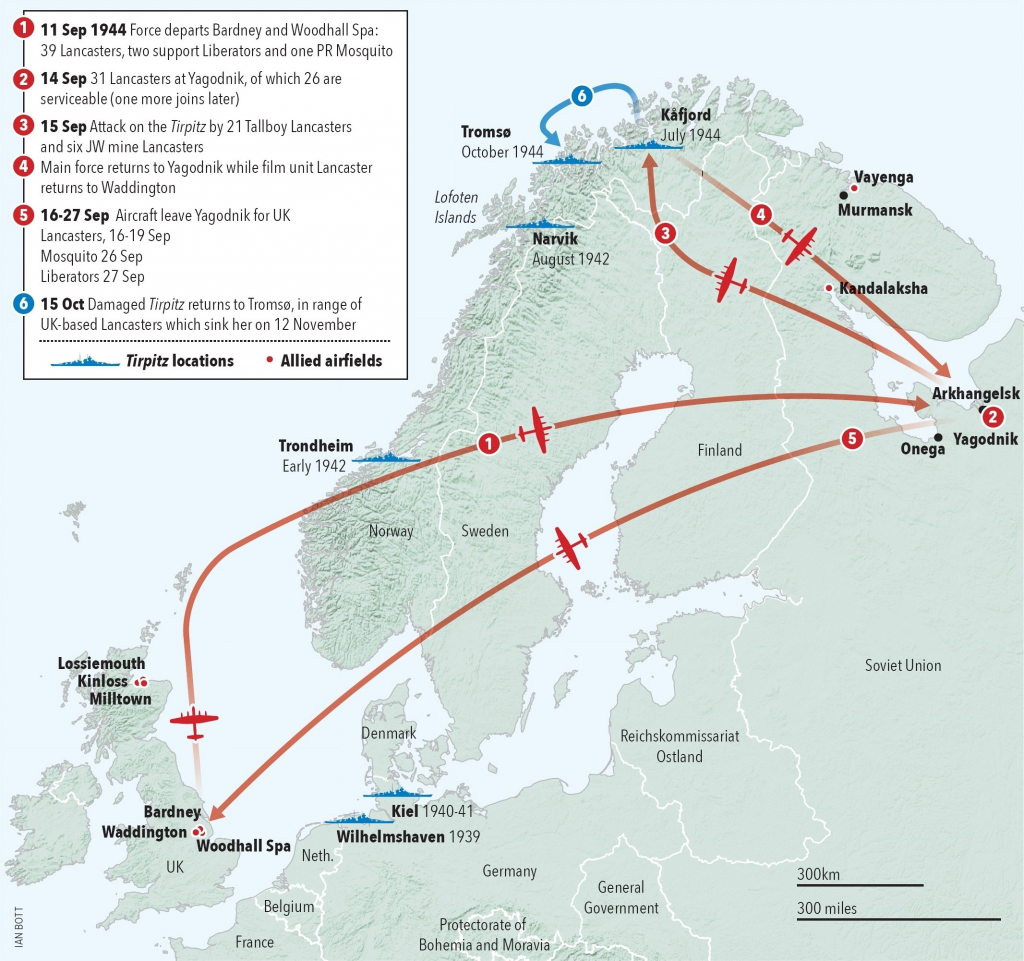

The official – and well-documented – engagement was Operation PARAVANE, which was prepared in August 1944, and took place the following month. PARAVANE was a project undertaken by the RAF to bomb the Nazi battleship, Tirpitz, lying in a Norwegian fjord, and ready to attack the British-American convoys that were transporting valuable matériel to Stalin, via the ports of Murmansk and Archangel. After the foray against the Tirpitz was completed, launched from Soviet territory, and a reduced set of aircraft was being prepared to bring the airmen home to the United Kingdom, a decision was made to re-route one of the aircraft over Swedish airspace to a location over southern Norway, where two parachutists were to be dropped to undertake a dangerous mission. Having arrived at its destination, the plane crashed into a mountain, and all aboard lost their lives. This series of articles offers an explanation of what events and negotiations led to the disaster.

At the time that Operation PARAVANE was executed, the war against the Axis forces was considered by most military experts to have been nominally won. The Western Allies had made a successful re-entry to Normandy in June 1944, and were advancing steadily towards the German borders. By the end of August, Paris had been re-occupied. The Soviet Red Army had advanced on a broad front from Bucharest to the River Dvina in Latvia, and General Rokossovsky’s Army was approaching Warsaw. British, Canadian and American troops had begun to cross the Gothic Line in the Apennines of Italy. Inside Germany, opposition to Hitler was mounting. On July 20, the plot to assassinate him had taken place, although the dictator escaped with injuries. The Allies demand for ‘unconditional surrender’ meant, however, that many more months of intense fighting would take place before the Germans capitulated.

Great Britain and the Soviet Union had always enjoyed a fragile relationship in the conflict with Nazi Germany. When the contradictions of the Nazi-Soviet pact were unveiled by Hitler’s attack on Russia in June 1941, Churchill had immediately expressed urgent support for his erstwhile ideological foe, who had helped Germany with valuable matériel in its assault on Britain. Stalin had responded by quickly making unreasonable demands on Britain, and used his network of spies to gain intelligence, and his agents of influence and ‘useful idiots’ to further the Soviet cause with the British citizenry. After making a private foolish and unauthorized commitment to Stalin about launching a ‘second front’ in France way before the Allies were ready, Churchill was continuously nervous about the dictator’s moods. Yet, after the Soviets repelled the German advance at Stalingrad in February 1943, the balance of power shifted markedly.

In this context, Churchill’s desire to destroy the battleship Tirpitz might be viewed as a bit obsessive. The U-Boat threat in the Atlantic had been largely eliminated, but Britain was still committed to delivering matériel to Stalin through the Arctic Convoys, and the presence of Tirpitz at Altenfjord in Northern Norway represented a large menace to their safety. After the disastrous scattering of the convoy to Murmansk, PQ17, in July 1942, the convoys had been suspended for a few months, and again in the summer of 1943, because of preparations for Operation TORCH. On October 1, 1943, however, Churchill, always eager to appease the demanding Stalin, had assured the Soviet leader that they would resume in mid-November. Moreover, the Soviets had been difficult and prickly over the British presence in Murmansk, ordering two communications stations there to close. In April 1944, British aircraft had tried to attack the Tirpitz from Scottish bases with Barracuda bombers, but they had caused little damage. They followed up during the summer with six further futile attempts, at considerable expense of fuel and ammunition, but were foiled by bad weather and the ship’s defences.

Shrewd observers – especially in the War Office – had already recognized that the Soviet Union was going to be an ideological and maybe real adversary after the war, as Stalin’s plans for subjugating the countries of eastern Europe became clear. Despite the Foreign Office’s enduring belief that Stalin and his commissars would behave like English gentlemen if they were approached with a spirit of cooperation, the Soviets remained uncompromising, suspicious, secretive, and very protective of their country’s subjects. Any intrusion from the West was interpreted as espionage, and as an initiative designed to subvert the Communist empire. Attempts to share intelligence between Britain’s services (i.e. SOE and MI6) and the NKVD had collapsed in mutual incriminations, and SOE was ready to withdraw its station in Moscow in the spring of 1944. Thus the opportunity for cooperation over bombing raids on the Tirpitz would have seemed to be unpromising.

Such qualms would be reinforced by the scandalous behaviour of the Soviet Union during the Warsaw Uprising, which had started on August 1. It was on the Poles’ behalf that Britain had declared war on Germany back in September 1939, and a vigorous Polish government-in-exile in London was keen to see it resume a traditional role in a freed Poland after the Germans had been expelled. Churchill (and, to a lesser extent Roosevelt) was anxious to provide all the help he could to the beleaguered Poles in Warsaw, but was restricted in having to launch support flights from bases in the United Kingdom and in Brindisi, Italy. Stalin had other ideas: he had created the so-called Polish Committee for National Liberation on July 22, and planned to install a Communist regime in Warsaw when the Soviets took the city from Germany. He refused to offer any support to the rebels from his troops on the other side of the Vistula, and rejected Churchill’s requests for landing-grounds behind Soviet-held territory. Stalin was now more universally accepted, even by Britain’s Foreign Office, as an untrustworthy partner.

Thus the Cold War could be said to have started, not with the revelations about Soviet atom spies in September 1945, not at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, but on the banks of the Vistula in September 1944. When Churchill later met Stalin at the ‘Tolstoy’ talks in Moscow in early October, a rather cynical carve-up of Europe was arranged. At this convention Stalin also made stringent demands for a new Polish-Russian border, roughly equating to the old Curzon Line, but forcing the important city of Lvov to be on the Russian side. Churchill was required to return to London to take this dismal message to the Poles, having already upset them with his refusal to challenge Stalin on the circumstances of the Katyn massacres of 1940. The political climate for the British gaining a high degree of collaboration from the NKVD and Soviet Air Force on an aerial mission that required the use of Soviet airfields for an assault on the Tirpitz would therefore seem to have been entirely hostile.

Yet some measure of cooperation had taken root in the summer of 1944. A combined military mission to Moscow had been established as long ago as July 1941. At that time the role of the 30 Mission (as it was dubbed) was more of an intelligence-gathering exercise, as the British War Office and Foreign Office believed then that the Soviet Union would collapse in a matter of weeks before the Nazi onslaught. It was led by a rather foppish Major Macfarlane, whose intelligence background irritated his hosts. In April 1944, however, just as NKVD-SOE relationships had broken dramatically apart, a Lieutenant Abercrombie was sent out to try to define some manner of shared objectives. These background negotiations turned out to be pivotal for the ability of Bomber Command to make rapid changes to its plans at the beginning of September 1944. After the success using the Tallboy bomb in raids on French ports, a fresh approach using these new weapons was considered, initially involving bombers stretching their fuel resources by flying again from Lincolnshire and Scotland to the northern fjords of Norway.

It was in this context that the plans for Operation PARAVANE were made.

Chapter 2: Planning for PARAVANE

It was only after June 1944, when successful operations using the 12,000 lb. Tallboy bomb were carried out in France, that the Royal Air Force started to consider using the weapon against the German battleship Tirpitz, berthed at Altenfjord in northern Norway. Yet there was a catch: the only aircraft that could carry such a heavy bomb was a modified version of the Avro Lancaster. After detailed analysis RAF Bomber Command concluded in August that an operation to deploy a squadron of Lancasters for a direct raid from Scotland was not feasible because of the aircraft’s fuel capacity. They thus considered using a base in the northern Soviet Union, Vaenga 1, near Murmansk, as an intermediate refuelling station after the raid.

This airfield, Vaenga 1, was already known to the RAF, as it had been used by Coastal Command (151 Wing) back in 1941, shortly after the Soviet Union became an ally. Hampdens and Mosquitoes had been sent there for training Soviet crews. In April 1943, Coastal Command had evaluated Operation HIGHBALL, using the newly formed 618 Squadron with specially modified Mosquito aircraft, and the Barnes Wallis-designed bouncing bomb, to attack the Tirpitz. Vaenga had been considered as a possible destination, or even launching-site for the operation, but concerns were expressed about the security aspects of exposing technological secrets to the Soviets, and for a variety of reasons the project was abandoned.

At the instigation of the Americans, who first came up with the idea of using Soviet bases for shuttle bombing, General Ismay, at the Moscow Conference of October-November 1943, had made a request for the provision of such bases on Russian territory. The Joint Chiefs of Staff also made a request for the Russians to exchange codes and procedures for communicating weather information, and instructed the US and GB Missions in Moscow to follow up. In April 1944, the question of bombing the Tirpitz was raised by Admiral Fisher at the first Mission Conference held by General Burrows (who had replaced General Martel in March). In May Burrows started defining procedures for how airmen stranded in Soviet territory should identify themselves, suggesting strongly that some agreement for the RAF to operate over Russia had been worked out. Briefly, negotiations appeared to improve, as the Soviets articulated plans for attacking the Germans in Northern Norway, which the British believed might assist the BODYGUARD deception. While that venture came to nothing, by August 1944 it appears to have been Bomber Command’s understanding that gaining approval for an operation that required landing on Soviet soil would be a formality. A message dated August 28 indicates that permission would nevertheless have to be sought through the Mission in Moscow.

The formal request was made on September 1, for an operation scheduled to take place on September 7 – an alarmingly short period for gaining approval, and then planning and implementing all the support and infrastructure required. While that approval appeared to be very quickly forthcoming, however, a setback occurred. Vaenga was quickly deemed to be unsuitable. The same day, Air Vice-Marshal Walmsley of Bomber Command, working on a survey recently undertaken by a Squadron Leader in the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit, wrote to Air Commodore Bufton in the Air Ministry requesting that alternatives in the Archangel area be investigated. The primary obstacle seemed to be that Vaenga’s proximity to the target meant that it could be exposed to raids from the German Air Force (although it should not have needed photographic research to confirm that). Moreover, the runways were probably of inferior quality.

The outcome was that from a shortlist of a few other airfields, Yagodnik, on an island south-west of Archangel, almost 400 miles from Murmansk, rapidly became the favourite. It possessed a solid runway that could be extended to 1500 yards – shorter than that at Vaenga, but adequate, as the minimum length required was 1400 yards. One intriguing fact is found in a report describing the airfield, dated as far back as May 22, 1944. That survey pointed out that Yagodnik had been used by fighters and bombers, specifically the Petlyakov PE-8, a rather clumsy and accident-prone heavy bomber formally known as the TB-7. The fact that British personnel had been given permission to inspect such facilities, without any accusations of spying, suggests that negotiations for possible use by the RAF had been going on for some time. That may explain why Air Marshall Harris could take for granted at this late stage that the Soviets would agree to such an initiative, despite their customarily extreme wariness of foreigners. Any such move would have had to be approved by Stalin, and the role of 30 Mission as an intermediary in Moscow reinforces that assumption.

The willingness of Stalin to cooperate needs to be analyzed in the context of events in the recent past. Chapter 1 of this story described the ill feeling that had been engendered by his lack of support for the air drops of his western allies, who were trying to assist the Warsaw Uprising. Yet a lesser known scheme involving the United States at Poltava (an airbase in the Ukraine, west of Kharkiv) should also be taken into account. This precedent for the use of Soviet airbases had recently occurred as Operation FRANTIC, whereby the Soviets granted rights to the USA Air Force to conduct bombing-raids from Poltava on German territory between June and September 1944. This operation was not without controversy, however: the Americans were abused by the Soviets, especially when, on June 21, Soviet air defences failed to prevent a highly destructive raid on US aircraft by German airplanes, all of which escaped intact. Moreover, by that time, with the Soviet land forces moving close to Germany, the value of the base had sharply diminished. The important manufacturing targets identified by the Soviets were actually closer to Great Britain than Poltava.

What is more, the Soviets had exploited the presence of American aircraft on their soil by stealing technology secrets. In the light of their own very weak capabilities in this domain, they were keenly interested in the American technique of strategic bombing. Stalin issued strict instructions that every detail of American advanced technology be recorded by the Soviet Air Force, and the latter salvaged materials from aircraft that had crash-landed on Russian soil. They also learned all about the procedures of American ground-to-air-to-ground communications. Thus the opportunity to learn from the RAF about the Tallboy bomb and its method of delivery would have been highly valuable for future Soviet military capabilities. Stalin may have been sympathetic to the project to eliminate Tirpitz, but he had more devious goals in cooperating with Bomber Command. While the vozhd was extremely wary of any Soviet citizens’ being exposed to foreign influences, and the NKGB and SMERSH were trained to consider all such persons on their soil as spies, the arrangement of procuring advanced British technology on Russian soil (or swamp) would deliver more important prizes.

In fact, a more detailed examination of the War Diary of 30 Mission indicates that Stalin had become a more encouraging force behind the project for launching air operations over Norway. When General Burrows took over from the rather ineffectual General Martel, he started to introduce more discipline and determination into his dealings with the Soviets, including better treatment for casualties from convoy operations, and a loosening of the absurd rules about the issuance of visas to returning British officers. He pursued more aggressively the return of radio equipment seized by Soviet customs officials. And, as mentioned above, he started seeking procedures for assisting British aircrew members, possibly stranded on Soviet soil, to help identify themselves to the Red Army or the NKGB, a measure that must indicate that he expected British planes to be operating over Soviet territory. The Soviets were habitually unco-operative, but Burrows learned that they responded better to hard bargaining.

In any case, following the positive signal from the Kremlin, more detailed preparations were briskly made. To accompany the squadrons of Lancasters, Liberator aircraft would be required to carry maintenance engineers and spares. Group Captain McMullen was made responsible for the discipline, quartering and messing of all crews, and was scheduled to fly out in a Liberator in advance of the Lancaster squadrons. His role was to establish communications protocols, and rules for the use of beacons, and relay them to the UK, so that the arriving aircraft could safely find their way to Yagodnik. He had to arrange for the provision of fuel and oil to supply the aircraft for their journey home. He was also to be responsible for dispatching the operational air party on its return flight, or should the original operation have been abortive, on a repeat operation. He was to keep in close contact with British Naval authorities in Archangel and the Air Attaché in Moscow. All in all, it was an astonishingly complex and difficult task to be completed in just a few days, with issues of terrain, security, politics, language and electronic communications to be sorted out. Despite all the challenges, on September 7, the Operational Order was issued for all aircraft to be moved to the forward bases at Lossiemouth, Kinloss and Milltown.

Yet a very late revision to the plan occurred. As a further complication, Bomber Command had, after intense calculations and trials, concluded on September 11 that PARAVANE would better be launched from inside Soviet territory (and not simply use such bases for refuelling). The reason offered later was that the weather was primarily responsible, but also because the closeness of the Russian bases to northern Norway was less demanding on fuel requirements. In addition, the location would enable a surprise, and thus potentially more successful, attack from the south-east, since German Radio-Detection Finding apparatus would be less effective in spotting raids from that direction. Thus the new plan required the squadrons to fly directly to the Archangel area, there to rest and refuel, before launching the attack on the Tirpitz, and then returning to Yagodnik.

Who actually conceived this new plan is an enigma: the conclusions appeared to have been arrived at without consulting the Soviets. More sympathetic messages had recently been arriving from Stalin, however. At the end of August, he had floated the idea of creating an International Air Corps, to which Churchill responded enthusiastically. And on September 9, Stalin had announced that he would allow Allied planes to be launched from Ukrainian territory to support the Warsaw uprising – a hopelessly late gesture to save the Poles, but an indication that the presence of the RAF in northern Russia would now be treated more positively. This move was all the more significant since the Soviet Foreign Minister Vyshinski had recently forbidden any US planes assisting the Warsaw Uprising from returning to their base at Poltava.

This change of plan also presents some paradoxes. The archive does not state who made the decision: some historians claim it was Harris. At the end of August, Air Vice-Marshal Cochrane had been involved in intense trials with Squadron-Leader Tait that suggest that he had set out to ‘prove’ that the Tirpitz would be out of range, as if he had been commissioned to provide evidence for a decision already made. Despite coming to conclusions, presumably, that a direct flight to Altenfjord for the assault before landing in northern Russia would not be feasible, the existing plan must have been passed up to Harris for him to adjudicate. Why did Cochrane not propose an alternative plan? He either a) wanted the whole operation called off; b) was not aware of the possibility of an alternative approach by launching the attack from Soviet territory; or c) was party to an elaborate ruse, and pretended to play the innocent.

One account suggests that the USAAF had been the Soviets’ preferred choice as a collaborator for the assault on the Tirpitz. While Stalin did not have serious designs on occupying Norway (he was not even considering re-entering his contiguous neighbour Finland, despite the fact that it had been an adversary during the war), he was interested in gaining part of the Finnmark territory to the North, which would give him access to valuable mines, but yield a short frontier with Norway. In this regard, he still considered the Tirpitz a threat. But he disparaged the multiple, expensive, but unsuccessful series of raids on the battleship by the British, and hoped that the Americans might consider a second base in northern Russia. The Americans had been too chastened by the Poltava experience, however, and, with Germany on the run, Roosevelt was not interested in further buccaneering exploits in the European theatre of war. Thus Stalin turned to the British.

The archival material does suggest that a higher authority was involved. Harris’s memorandum announcing the change is directed to the Admiralty, with a copy sent to Bottomley at the Air Ministry. A memorandum from the Air Ministry informing 30 Mission of the change of plan has a time-stamp of three minutes earlier, however, indicating perhaps that both Bomber Command and the Air Ministry had recently been informed of the new directives. The Air Ministry memorandum attributed the change of plan to ‘weather conditions’ in the target area being too variable: Harris does not provide that as a reason. Moreover, Harris does not take responsibility in his own text, writing instead that ‘It has now been decided’ that the bombers will fly directly ‘from English bases’ (i.e. not via Lossiemouth or Unst) to Yagodnik. The implication is that the decision to launch the attack from Yagodnik had already been made, and it was the details on the route that were important. It is clear, from the anomalous and incongruous cables exchanged between Bomber Command, the Air Ministry, the Admiralty, the Naval Station in Murmansk, and 30 Mission in Moscow that an elaborate smokescreen was being created to conceal the secrecy and irregularity of the agreement with Stalin to use Soviet bases. The apparent rapid decision about a direct flight would have alarming and fateful consequences.

Hello

Could the person who has written this article please contact me . My grandfather was the 11th person . My mother has just died and to honour her ( and my grandfather whom she was very close) my son os an aspiring young film maker and is looking into making a short film about this . I contacted Nesbyn some 4 years ago to start the trail

of information finding whoever to date I have yet to connect the historian Magnus Lingdahl

Thanks, Gaynor. I have responded via email.

Tony.