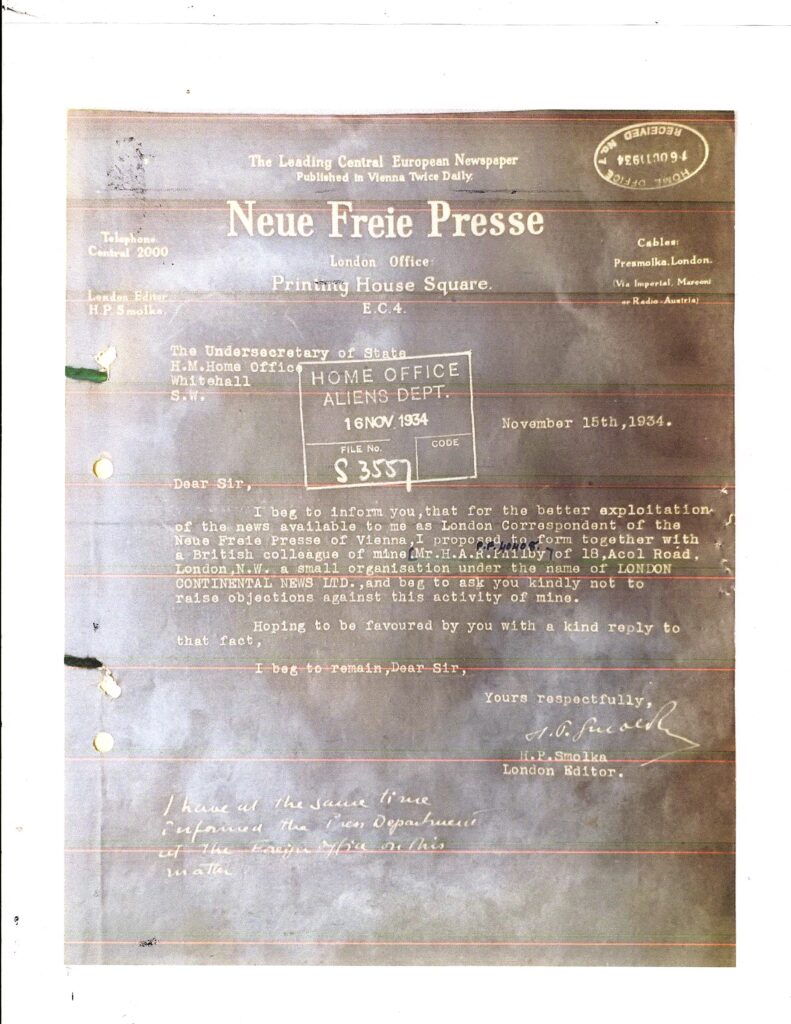

An Announcement: Before introducing this month’s report, I want to draw attention to an item that may have escaped the notice of some readers. In mid-February of this year I posted an analysis of the first of the Kim Philby files released by the National Archives (see https://coldspur.com/special-bulletin-not-the-kim-philby-personal-file/) . But I omitted to add an entry for it on the ‘About’ page of coldspur. Earlier this month, I posted a ‘Comment’ that explained this oversight, but that has long since disappeared from the visible ‘Recent Comments’ section. Now I do not know how most readers become informed of new coldspur postings. I suspect most just take a look at the beginning of each month, although I know the more advanced have special messages triggered when anything new appears. Many may miss the occasional mid-monthly Special Bulletin that I post. In any event, I wanted to ensure that those regular readers who may not have seen the item were aware of it, as it does contain some important information on Philby’s lies. Now, back to our normal programming . . .

Contents:

Introduction

Part 1:

The Rees File

The Blunt File

The Burgess File

Further Liddell Revelations

Intermediate Summary

The Chronology

Part 2:

Cold War Deception Planning

‘Double Agents’

The JIC Chairmen

Guy Liddell’s Accounts

The Defection

The Aftermath

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

This bulletin (‘B’- class) is a follow up on my report on the Soviet biologist and defector Nikolai Borodin (see https://coldspur.com/biological-espionage-the-hidden-dimension/). It does not extend the period under review, but digs more deeply into the circumstances, and the activities and statements of the participants. I recommend a re-examination of that piece – especially the section dealing with Liddell’s observations in his diary – for deriving optimum value from this report. I mention here that this topic has been one of the most challenging that I have addressed, with a uniquely high percentage of archival documents that look as if they had been designed to deceive. Remember, this story has been almost completely suppressed. And there must be a reason for it.

The story as previously outlined: In August 1948, the Soviet biologist Nikolai Borodin defected in the UK. At least, he appeared to. It may have been a stunt orchestrated by his bosses in Moscow, so that he might continue to feed back intelligence on Britain’s progress in producing penicillin, and its plans for bacteriological warfare. It could have been owing to an ill-advised move by the Foreign Office and MI5 to approach the scientist, in the belief that Borodin could be used for deception purposes. The incident was complicated by some disturbing events: for example, earlier in 1948 Goronwy Rees, the dubious colleague of the Soviet agents Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt, who was working part-time for MI6, was shown to be employed as a director of a firm called Pontifex, in the business of constructing brewing and distillation equipment useful for the creation of penicillin, and Borodin had been visiting that plant. That same spring Guy Liddell was discussing with Rees, as well as with Burgess and Blunt, the concern held by British Intelligence that the Soviets might be trying to acquire penicillin plant for the purposes of creating bacteriological warfare agents. A year later, in August 1949, Borodin turned up to give a lecture at an intelligence course in Oxford – hardly the behaviour of someone who had been in fear of his life – and he was heckled by Rees, Burgess and their ally in MI6, David Footman. Various government organizations were tripping over each other at this time, with the Joint Intelligence Committee searching for ways to increase its knowledge of Soviet strengths in atomic and bacteriological warfare, and other units trying to work out whether the Double-Cross successes of World War II (against the Germans) could be replicated in peace-time (against the Soviets) in order to mislead the perceived enemy about the UK’s intentions.

I pick up the threads of this extraordinary story with the following questions in mind:

- What else can be determined about Liddell’s schemes in trying to use Blunt and Burgess?

- Were such exploits approved by any higher intelligence or military authority?

- What were the facts behind Borodin’s defection, and why was he invited to the Intelligence Conference in Oxford?

- What was the current policy of the UK concerning deception, and the delivery of disinformation to the Soviet Union?

- How do these events relate to published rumours about the deployment of ‘double agents’ in mimicry of WWII successes against the Germans?

- Was Philby part of the team, and was Burgess’s visit to Philby in Turkey in August 1948 related to the project?

I set out to answer these questions first, in Part 1, by exploiting some fresh research material. The Personal Files of Goronwy Rees, Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt reveal some startling new facts. In Part 2, I report on my inspection of files concerning the revival of the wartime London Controlling Station (responsible for deception against the Germans), and its controlling body, the Hollis Committee (chaired by General Leslie Hollis, no relation to Roger). I have studied relevant Ministry of Defence, Cabinet, Joint Intelligence Committee, and Foreign Office archival material. I have read a few books relating to early Cold War strategy. I found two articles on deception operations during the late 1940s, by H. Dylan, of King’s College, London, useful, although they make no mention of Borodin, or of the Liddell exploits, and curiously elide some astonishing statements made by Stewart Menzies, the MI6 chief.

Part 1

I start by reviewing how the various material in the Personal Files relates to the schemes of MI5’s Guy Liddell, at the time Deputy Director General to Percy Sillitoe

The Rees File

In my earlier report, I had referred to the anecdote cited by Richard Davenport-Hines in his letter published in the Times Literary Supplement, which was unsourced, and appeared to go against the grain of what I had earlier discovered. I have since found that it comes from one of the earliest items in Goronwy Rees’s Personal File, in 1949, which I had earlier overlooked [see below]. Yet I first jump forward to Rees’s recollection of the events many years later, since it is the sole account deriving from him, the central player in the drama, and contains some important but erratic flourishes. These later records also help to provide a framework for the ‘Davenport-Hines’ piece that was written by James Robertson in 1949.

In an interview by Peter Wright on March 19, 1965 (KV 2/4607), Rees admitted his role at Pontifex (the new owner of Bennett Sons & Shears), when he told the MI5 officer that he had worked in an engineering firm that had some contracts with the Russians, and ‘had a lot of Russians to see us’. One day, William Skardon of MI5 had waltzed in without authority. At that point, Rees complained to Anthony Blunt, who speedily got in touch with Guy Liddell. (Rees misdated the event as occurring ‘in about 1950’.) Rees stated that he ‘went and protested’ to Liddell, and that the speed with which Blunt got hold of Liddell convinced him of their close association. He volunteered nothing more about the meeting [but see under ‘Blunt’ below], and then described the Russian engineer who later defected, adding, rather oddly, that ‘Anthony talked to me about this and wanted me to know all about it’. Instead of pursuing that line, Wright verified from Rees that the defector was in fact Borodin, and asked Rees whether he had any role in the defection. Apart from stating that he told them ‘everything I knew about him’, Rees denied any involvement. A few portions of the conversation are ominously and provocatively redacted, and then Rees disclaimed any knowledge of the defection itself, although he asserted that Blunt was in the thick of it.

The records suggest that someone [name obliterated] came to consult Rees about Borodin at some length after the Skardon visit, and that Rees claimed that Blunt knew all about the Borodin case. Further redactions appear in this particular transcript, concerning events of 1951: some of them may be an attempt to disguise the fact that Rees was working part-time for MI6 during these years. Even allowing for his drink-sodden condition at this time, Rees recalled some incidents, but not the vital events concerning Borodin, and his own role in the affair. It is a shoddy attempt at a cover-up.

A few years later, on May 15, 1969, when Rees was under further investigation, an entry was made in Rees’s file that echoed what Liddell had written in his diary [Source: WALLFLOWER] on January 19, 1948 and March 11, 1948: a handwritten note confirms that the same material lies in Borodin’s file, here given as PF 73525, but remaining unreleased. Liddell’s diary entry concerning the first of these two incidents adds one or two enigmatic flourishes, however. The entry starts, shockingly, as follows: “Anthony Blunt came to see me about a story which had reached him from Garronway [sic] Rees, via Guy Burgess.” After describing how he followed up with Skardon to discover what he had been up to (namely searching for information on the activities of the Russians)

Anthony asked me to meet Garronway Rees at his club that evening, which I did, and explained to him the circumstances. He said he thought the whole story had got considerably distorted, and that his fellow director had misunderstood our purpose. He told me there and then that the Russians were buying penicillin plant, and that his firm had received from Tito an order for a liquid oxygen plant. He thought, however, that it might be useful for us to be in touch with Neville, the Chairman – or Secretary – of the Chemical Plant Manufacturers Association. I told him that provided Neville had not already been approached by someone else, I should be quite interested to meet him. Rees promised to arrange this.

It is hard what to make of this. One might expect the immediacy of the report to reflect reality better than the garbled recollection by Rees seventeen years later (when he cannot even recall the year), but, of course, Liddell might have been dissembling. My inchoate thoughts run as follows:

- Liddell’s introduction of Burgess into the narrative is clumsy, but telling. Neither Rees nor Blunt mentioned that Rees had contacted Blunt through Burgess, and Liddell’s gratuitous insertion should be interpreted as being reliable. Rees’s closeness to Burgess at this time is very incriminating.

- It is hard to interpret Liddell’s involvement of Burgess and Blunt in the exercise as anything but foolhardy (Blunt had left MI5 in 1945), but Rees must surely have known that they were colluding in some way.

- The dispatch of Skardon into the plant without the owners’ (or at least Rees’) being informed, and under such furtive cover (he had forgotten his ‘credentials’) was spectacularly clumsy, and inexplicable. MI5 could have gained the information it needed simply by calling in Rees (who was working part-time for MI6, of course).

- Rees’s protestations were thus disingenuous, and easily appeased. His suggestion that the story had been distorted was evasive. It was not a question of his fellow-director’s misunderstanding MI5’s purpose: if the director had genuinely not been inducted into the scheme, he would have remonstrated at the uninvited entry itself, not its objectives.

- Liddell’s suggestion that it was Rees who informed him for the first time of the Russians’ intentions is as naïve as Rees’s protest. He must have known of the affair, which involved a visit by the Soviet Trade Delegation into which Borodin may have inserted himself. That is why Skardon was sent in in the first place.

- Rees’s fellow-director (certainly Henry York, aka Henry Green, the author) probably suggested that Rees go through the charade of protesting in order to preserve appearances, and protect his (York’s) reputation.

- The business of Neville and the Chemical Plant Manufacturers Association seems to be an irrelevant piece of nonsense designed to make the whole charivari sound humdrum. Possibly Liddell was being encouraged by Rees to contact Neville to verify that the Soviet visit was pukka, but Liddell’s response does not make much sense.

(If anyone can correct or enhance this interpretation, please let me know.)

The important item which I had previously overlooked, the source of the Davenport-Hines anecdote, however, is J. C. Robertson’s report dated April 4, 1949, which appears as sn. 3F in KV 2/4603 of the Rees PF. It is worth paraphrasing the bulk of its text here.

Robertson is clearly following up on Skardon’s visit, although the delay of a year is highly problematic. It is also apparent that Robertson has met Borodin (or possibly has read a report of his), since he records that Rees’s work colleague, Mason, is ‘just as JULEP [Borodin’s cryptonym] described him’. (Mason must surely be an alias for York.) Yet Robertson goes on to describe Borodin’s defection in very odd terms: he expresses surprise that Rees and Mason knew nothing at all about ‘JULEP’s resignation’. He continues: “I admitted that their assumption that he had resigned and was available in this country was correct, but emphasized that this fact was known only to a very few people and that knowledge of it must continue to be carefully restricted, both in the national interest and in the interest of JULEP’s own safety”. The safety issue was paramount, of course, but Robertson’s observations were naïve in the extreme: no one was free to ‘resign’ from Stalin’s organs or institutions, especially if they were on business in the West, and Borodin’s fears for his security are made clear when Robertson reports that Borodin had stated that ‘this country is too small for him’. Robertson then declares that MI5 was indeed planning for a way for Borodin to start life in a new country – surely Canada, as an earlier minute by Robertson had suggested.

The discussion then turns even weirder. Mason reiterates (so Robertson asserts) what Rees had already proposed to Liddell, namely that Pontifex seeks JULEP’s advice on ‘the relative merits of present day processes for manufacturing penicillin’, and, if the short-term project is successful, they would seek his help if they were able to place contracts for the delivery of penicillin manufacturing equipment to various overseas countries. Robertson reported that Rees and Mason seemed to be in somewhat of a hurry, as they feared losing their markets, and they were also suspicious of what the renowned biologist Ernest Chain might be doing behind their backs. Robertson promised to consider the matter of a further meeting, but pointed out that the firm’s proposal might conflict with the plans for sending Borodin abroad. Two further notes (one heavily redacted), dated April 1, confirm Robertson’s making arrangements, under conditions of strict secrecy, to have consultations with Rees and York before bringing Borodin up from his lair in Gloucestershire.

As I pointed out earlier, this seems utterly nonsensical. Borodin had been learning manufacturing techniques from Chain himself, and was on a legitimate mission to try to purchase penicillin plant, no matter how high the price. Why would a British firm use a Soviet defector, who had illegally been stealing secrets from Chain, to help them protect their markets, with MI5’s assistance, when MI5 had already known about Chain’s relationship with the Soviet scientists, and had allowed him to depart for Italy unscathed? Why, if Borodin had needed to be removed to Canada for safety reasons in August, 1948, was he still in the country? It seems to me that the whole entry is a plant, a Soviet-style ‘spravka’ to distort the facts, and leave a false trail. Robertson’s contribution is another feeble attempt at a cover-up.

I shall later (under ‘Aftermath’) analyze another extraordinary piece of background information to this report, but first: What do other recently released files tell us about the events?

The Blunt File

A few months after the Rees interview, on July 12, 1965, Blunt was interrogated by Arthur Martin, now with MI6, and Peter Wright (see KV 2/4708). It was an important event, with an odd prologue. In a preliminary interrogation on June 26, Blunt himself had brought up the subject of Borodin. “What, you once said you wanted to ask me about a white – uhm – no someone called BORODIN whom I’d gone to see Goronwy about”, the art historian somewhat elliptically interjects. When Wright responds that he cannot remember the dates, Blunt volunteers that it must have been ‘about 1948’. Wright states that Borodin was a Russian defector ‘over here as a scientist, in some form of liaison with Goronwy’s firm’, an opinion with which Blunt agrees. But when Wright elaborates, as follows: “And he defected and you went to see Goronwy, whether what is not clear from the Office file, I shall have to look it up again now, is whether you went to see Goronwy, at Goronwy’s instigation, or somebody’s else’s instigation.”, Blunt immediately disclaims all knowledge of the affair: “I have absolutely no . . . . He was a scientist?”.

Wright’s performance is feeble. He has not prepared himself properly on the case, and Blunt, having introduced the name Borodin a few minutes ago, now gets away with giving the impression that he is unaware that he was a scientist, having forgotten he had concurred with Wright’s description of Borodin’s profession a few minutes beforehand. Wright’s suggestion that Borodin had already defected is in direct contradiction to what Rees had stated, namely that he defected after the Skardon visit. Had Rees been lying? Did Blunt indeed go back to see Rees later in 1948, after the defection? Did Wright actually know the truth? That latter postulation seems unlikely, as the evidence from Liddell’s Diaries indicates that the idea for defection was originated by Hayter in the Foreign Office in February 1948, that the Skardon incident occurred later that month, and that the actual plans were not set up until May. It is no wonder that, since Wright was so unprepared, he could not dismantle Blunt’s prevarications more effectively. Blunt continues to show amazement when he is told that he and Rees met, and that he had made a recording of Rees’s statement after that meeting. Wright then introduces his main thrust, namely that he wanted to ask Blunt whether he had told Burgess about the meeting, since he would have expected that Guy would tell the Russians. “Why did the defection happen?”, he asks, forgetting that he has recently stated that the defection occurred before these events. Wright has to retreat in confusion, and vows to come back to the topic later: several last exchanges on it have been redacted from Blunt’s file.

Thus Wright returned to the topic on July 12. Well into the session, Wright, presumably better informed this time (he claims he has been doing some homework), suddenly changes the subject from other possible contacts of Blunt’s – to Borodin again. In responding to the questions from Wright and Martin, Blunt shows all his most infuriating traits: rambling and evasive responses, an inability to recall anything clearly (attributing that failing to an abnormal memory), and a frustrating way of hypothesizing how he would have behaved at the time had he known the facts that his inquisitors claim he must have been aware of. At the same time, he gently mocks Wright’s ignorance. Wright tells him that Rees called Blunt to get him to tell Liddell to ‘call his wolves off’, following which Blunt introduced [sic] Liddell to Rees at ‘the Club’. “Did Guy not know – er – Goronwy?”, he asks, receiving the answer “Apparently not.” Liddell had died in 1958, so he was no longer around to explain, but his diary entry for January 19, 1948, confirms that Blunt asked Liddell to ‘meet’ Rees that evening. Blunt’s query suggests that they were probably familiar to each other, as does Liddell’s first mentioning of him. (I can find no evidence of an actual encounter before then, but Rees’s career would suggest that Liddell must have known about him.) Again, Wright had not done his homework. Liddell also recorded that Rees’s request came via both Burgess and Blunt: that fact had also escaped Wright’s preparation.

Wright rambles a lot as he tries to get to the point, mixing up dates. His claim was that Skardon started making his inquiries because, first, the JIC (Joint Intelligence Committee) was very interested in the Russians’ attempts to find out how penicillin was made. They were ‘trying to buy a plant illicitly’ – probably, more accurately, trying to acquire the specifications for constructing a plant. (There was nothing ‘illicit’ about their endeavours.) Second, ‘during the course of these inquiries we discovered that BORODIN wanted to defect’. Whether this desire was coincidental to the fact that Hayter of the FO wanted to lure Borodin into defecting is not stated by Wright. Now Wright reaches his climax again: “Well the relevance of all this is, basically can you remember anything about it and if you remember anything about it, did you tell Guy about it?”. Here Wright classically forgets that Liddell stated that the request from Rees had come through Burgess. Why Burgess had had to be inserted in that chain is also not clear, but even if it had been incidental, Burgess’s curiosity, and his known identity as a conspirator with Blunt, should have alerted Wright’s antennae.

One might hypothesize that, at this point, Blunt was so shocked at Wright’s inept display that he decided to play dumb himself. He professes ignorance as Wright goes over the events leading up to the defection on August 28 after Borodin had announced his intention, informally, on May 25, and formally, on August 20. Wright’s main interest is driven by the fact that Burgess went off to see Philby in Turkey at this time, and wonders why he went. (He does not give a date: Andrew Lownie writes that it was in early August.) Yet, instead of claiming ignorance, Blunt stumbles, saying that Burgess went ‘on business’, but had trouble explaining how he could finance the trip, adding that Burgess had some story that his mother had helped him. (It was probably not official UK Government business, although it might well have been part of a clandestine operation.) “So why did Burgess need to see Philby?”, ponders Wright, declaring that he could have informed his Russian masters in the UK of any vital, fresh intelligence. He is perplexed that Blunt has no recollection of the defection events at all, despite his familiarity with Burgess’s movements.

Blunt is then forced into his posture that what Rees said in the files doesn’t make sense, since he (Blunt) would have reported it to his controls, and the defection manœuvre would have been called off. He tries to sweep away the whole issue by stating that he might have introduced Rees to Liddell without knowing that a Russian was involved, clumsily contradicting what Liddell wrote in his diary. Wright reminds him that Rees claimed that he not only arranged for Blunt to introduce him to Liddell, but that he also told Blunt the whole story, since he himself had engineered the defection. The exchange then becomes farcical, and even more chaotic, with Blunt again blaming his faulty memory, and even attributing Rees’s vivid imagination to the fact that he was Welsh. Wright and Martin have to abandon their inquest, while Blunt promises to try to recall the details of Burgess’s visit to Philby in Turkey.

It seems obvious to me that Wright, conscious of the fact that the Borodin ‘defection’ went horribly wrong, is trying to determine whether the leakage extended to Philby, and whether Burgess had been the messenger. While this throws fascinating light on the possibility that Philby may have been part of some disinformation scheme (why else would Wright have brought up Philby’s name?), Wright ignores the obvious fact that Blunt, evidently much closer to the negotiations, could have – and would have – passed on such information to his controller. Blunt even admits this, but then claims to have forgotten all the details, taking advantage of Wright’s undisciplined approach to the interrogation. Wright’s obsession with Burgess’s role, and his overlooking the key facts of the case, represent an abject performance. He is not well aided by Martin. Meanwhile, Blunt is allowed to get away with an excruciatingly embarrassing display.

A few months later, Blunt was able to explain a bit more about Burgess’s visit. On October 5 (see KV 2/4709, sn. 539b), Wright met Blunt at the latter’s flat, and opened the discussion by saying that he had come across a report by a colleague who had visited Philby in Istanbul at the same time as Burgess. The man had said that Philby had been very worried after Burgess arrived, but had mistakenly interpreted that agitation as being due to Philby’s fear that Burgess might do something disgraceful. That did not make sense to Wright, and he brought up the fact that Blunt had said that the Russian Intelligence Service (RIS) had paid for Burgess’s trip to Turkey. Blunt now remarked that they had authorized it because ‘Guy was losing his nerve’, but could offer no explanation, and inquired of Wright whether he had any insight. Wright had none. This whole rigmarole sounds equally ridiculous. Why the RIS would respond to such a concern by drawing attention to an encounter with another suspect (as Philby surely was by now), funding a flight that Burgess could not afford, defies reason. There must have been something more important at stake, and Burgess must have convinced his controllers that it was vitally important that he see Philby in person.

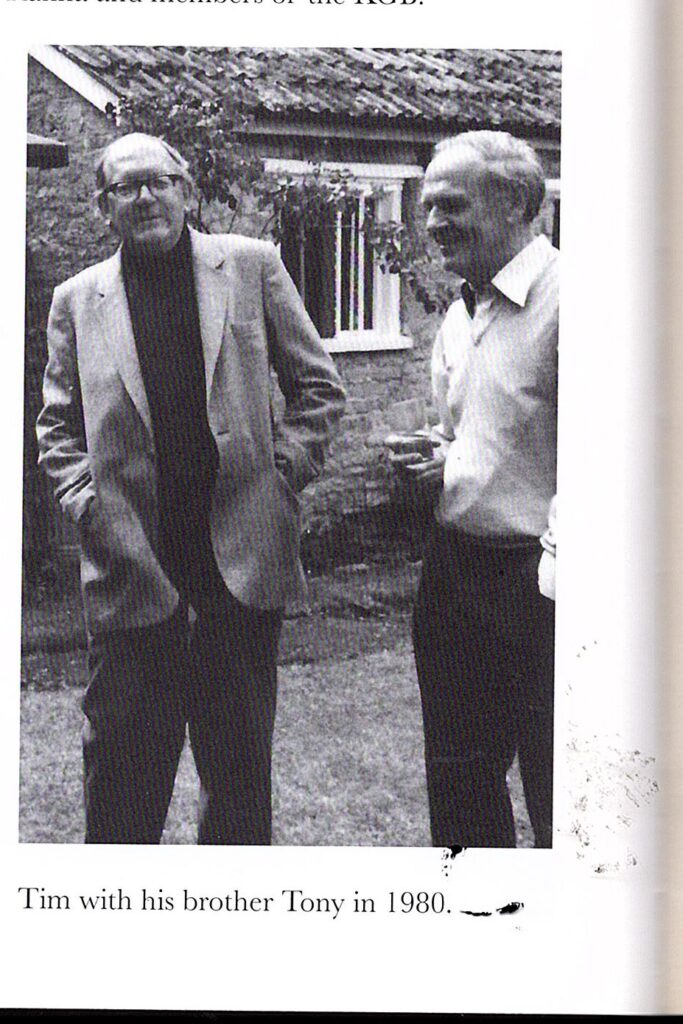

Mysteriously, the ‘colleague’ cited by Wright, who was certainly Tim Milne, gave a different account in his memoir Kim Phiby: A Story of Friendship and Betrayal. He implied that Philby had seen the visit as having been arranged by the Foreign Office, not the RIS. Milne interpreted Kim’s anxiety, however, as being over the possibility that Burgess, in some of his late-night escapades, might have been meeting the Russians. Even stranger, he reported that a telegram arrived from the Foreign Office informing Burgess that he was not needed back immediately and ‘could have another week in Istanbul if he wished’ – much to the chagrin of Kim and Aileen Philby. (‘The Man Who came to Stay for the Weekend’?!) One cannot trust Milne’s memoir: he was probably trying to help out his old friend. Again, too many deceptive stories are being told.

The Burgess File

Lastly, in this set, come items in Guy Burgess’s PF, including Burgess’s own testimony about the conference at Oxford. The first relevant entry, however, relates to Burgess’s visit to Turkey in 1948, as described above. On November 28, 1951 (see KV 2/4107, sn. 335b), J. D. Robertson (B2), in the thick of the deep investigations into Philby before the latter’s interrogation by Milmo, passes to Arthur Martin (B2b) some photostats relating to Burgess’s visit to Istanbul. They appear to be telegrams (not provided) that show that Burgess approached Philby at the end of May, 1948, to suggest he visit him, and that Burgess was in some haste, since he wrote by telegram, not letter. Robertson had suggested to Martin that, because of the suddenness, and the expensive air travel, Burgess might have got wind of the approaching defection of [redacted – obviously Borodin]. Robertson further claimed that Burgess would have known nothing about the defector except that he was a senior Soviet official, and thus might have feared that he might be in possession of information about both his and Philby’s activities. The result would be that he might seek advice from Philby as to whether either of them should contact the Russians, to inform them, but also to inquire whether [Borodin] did indeed possess dangerous information. To support his theory, Robertson attached extracts from [Borodin’s] file, showing the telephone checks that confirmed the possibility of Borodin’s defection on May 27. Robertson also described the role of Rees at Bennett Sons & Shears, and mentioned that the firm was in contact with C.P.R. (presumably the ‘Russian Communist Party’).

This seems to me like another bogus entry from Robertson. He knew that Burgess had been involved with the Borodin business, and Burgess thus would have known that Borodin was a ‘mere’ scientist, and not tightly engrained into the MGB’s espionage practices. If Burgess had deemed it appropriate to consult his local controller, he could have done that off his own bat, without lengthening the process by an ostentatious and expensive flight to Istanbul. (By all accounts, Philby was at this time feeding information to Burgess in private mail correspondence, which Burgess passed on to Yuri Modin, his controller.) Burgess did not leave until early August, by which time two valuable months had been lost, which does not suggest urgency over a possible exposure. And did those telegrams exist? Were Burgess’s communications being intercepted at this time? Other information suggests that Burgess arrived in Istanbul unannounced. I should say that Robertson was concealing the truth from Martin, and sending him on a wild goose-chase.

The next item – which would appear to undermine Robertson’s testimony – was submitted by MI6 to Ronnie Reed on December 14, 1955, in a long memorandum titled ‘GUY BURGESS and the Military International Affairs Study Group, Worcester College, Oxford, on 9th-12th September, 1949’. It starts off by stating that the Assistant Chief of MI6 was looking for subjects and outside lecturers, and wondered whether Goronwy Rees would be able to offer Borodin to talk on defection? David Footman had recommended Burgess and Blunt as speakers, and suggested that someone in MI5 be approached over Borodin, as Rees was away. There follow some fascinating details about other speakers, of marginal relevance to this story, and a notorious anecdote about Burgess’s borrowing from Carew-Hunt a handbook on Russian forged documents, and never returning it. (The list of attendees has been redacted: one of them had certainly advised Burgess of the existence of the handbook.)

Yet the most astonishing aspect of this saga is the invitation to Borodin. Robertson had the previous year stressed how exposed Borodin felt, and he added that the Russian was going to be whisked away to Canada after his defection, away from the claws of the MGB. Yet now he was going to be invited to a conference to speak about his experiences! It makes no obvious sense, from any angle. For some reason, his life is no longer in danger. Moreover, MI6 and MI5 conspire to bring him out into the open, where any loose lips might betray his presence to Soviet Intelligence. David Footman behaves recklessly, even traitoriously. If Borodin had any value as a defector (a questionable assumption, in the first place), he must by then have surely told the British authorities all he knew about Soviet capabilities for making penicillin, which were flimsy in the first place. Why would Borodin have been set up in this way, and why would he have agreed to it?

On April 11, 1956, Maxwell Knight sent to Reed a photostat of a recent letter from Burgess in Moscow to Tom Driberg (KV 2/4115, sn. 689a). It contains Burgess’s view of the conference, and the passage is worth quoting in full:

Of course what you say about Petrov is true – he was a ‘paid nark’. As far as can make out, he gave his original information C.O.D. and subsequently added to it – in different and self-contradictory forms in England and America – on the hire purchase system. They always do – and the Foreign Office and the Intelligence services should know that perfectly well. I remember I once stayed for some days at a joint Secret Service-M.I.5 ‘house party’. One of the visiting lecturers was a Soviet defector, rather like Petrov, called ‘Borodin’. After he had given his talk containing sensational secret revelations about the USSR, he was whisked away. The audience, all of whom, except me, were members of either the Secret Service or M.I.5 and hence people of whatever experience the officers of those strange services do have – even they smelt obtrusive rats in the revelations we had heard. They attacked the organizer of this proto-Petrov. This was an officer of great experience. He sadly admitted that scarcely a word was to be believed, but that it was always the same. People had to invent to earn their keep. He quoted the cases of Krivitsky, Kravchenko and others as examples.

Who was that officer? In a note to file, Reed kindly offered an explanation the following day: For the sake of the record it should be said that BORODIN was accompanied and introduced by U.35 [‘Klop’ Ustinov] who left with BORODIN immediately after the lecture. Those who were forefront in the attack upon BORODIN were BURGESS, REES and FOOTMAN. So far as I recall the ‘organiser’ who spoke of BORODIN was either Carew-Hunt or [redacted]. However, neither said that ‘scarcely a word was to be believed’. They said in fact that BORODIN did not know as much as he claimed to know, and that he was rather a stupid man who was intent on claiming more knowledge about Soviet policy and personalities than he did in fact possess.

Yet that statement raises even more questions. If he was considered ‘stupid’, why did they invite him to the conference? How could the trio of Rees, Footman and Burgess (an outsider from the Foreign Office) get away with such insulting and disreputable behaviour? Who was in charge here?

Further Liddell Revelations

Apart from an objection by MI5’s Legal Adviser that a passage on Borodin be deleted from Tom Driberg’s book on Burgess, that is almost the totality of the archival record on Borodin, so far as I can judge. (Of course, his PF has not been released.) Yet, since my initial report, I have unearthed some further passages from Liddell’s Diaries – describing possible defectors, presented anonymously – that I believe shed more light on the events leading to Borodin’s defection. A few months after the critical JIC meeting on February 4, 1948, at which its Chairman, William Hayter, had talked to Liddell about Borodin’s potential as a defector, Liddell starts referring to ‘the case’ in his diary. It is obvious that this terminology actually refers to two cases of defection – one for someone seeking asylum in the USA, which appeared not to be problematic, and the other undoubtedly describing Borodin (whose name has been rather unnecessarily redacted, given its high visibility in recent posts).

On June 24, the day after another JIC meeting, Liddell recorded Hayter’s current concerns with Case No. 2, as he explained them to his officers Moreton-Evans and Marriott:

Hayter had grave doubts about our proceeding with xxxxxx and said that he would have to consult Orme Sargent [his boss] and possibly Bevin [Foreign Minister]. Before doing he would see Courtenay [not Courtenay Young, but one Commander Courtney]. This seems to raise quite serious issues. If it is desired to obtain defectors here the initial move must be made by someone in official circles who knows the defector fairly intimately and in whom the defector has confidence. This obviously involves certain risks and unless the authorities are prepared to be tough and to say that they know nothing about it they will have to make up their minds that any form of provocation on the matter of defection in this country is out of the question.

This is rather a belated warning by Liddell. If his advice makes sense (which it does), he should have presented it to Hayter back in February. One cannot help wondering whether it is a posting to cover himself and Hayter, with Moreton-Evans and Marriott brought in as stooges.

On June 29, he made a similar showy declaration to one Baker-Cresswell (certainly Joe Baker-Cresswell, deputy-director of Naval Intelligence, who had, somewhat alarmingly, been educated at Gresham’s School, Holt, but had redeemed himself by being the naval office responsible for retrieving the submarine U-110’s Enigma machine and codes in May 1941). Baker-Cresswell was asking whether the xxxxxx case (the American one) was dead, and Liddell reported:

I said that as far as I knew it was dead. The case did however raise certain definite issues which I thought should be thrashed out in the J.I.C. It was abundantly clear that if we were called upon to provoke defection two basic assumptions would have to be accepted in principal; (1) that the person promoting defection would have to be a Government official known as such to the defector; (2) that this Government official would have to be known and trusted to the defector. It would further be necessary that if things went wrong and questions were asked, the Government would have to make some sort of denial that any approach had been made. In this particular case they would have to say that xxxxxx’s wife had completely misunderstood Commander Courtney. The F.O. point is that even if such a denial were made the Foreign Secretary would not be prepared to face the issue in view of the recent trouble about TASSOEV.

Tassoev was a Soviet defector who had recently changed his mind, and the authorities were undecided as to what to do with him. In any event, the exchange shows how sensitive all defection cases were at the time, and Liddell is building his cover as a cautious policy-maker. Baker-Cresswell was apparently satisfied with the response he received.

Yet the following day Liddell and Hayter have changed their tune. After the June 30 JIC meeting, Liddell entered the following:

I spoke to Hayter after the J.I.C. today about the case of xxxxx. I told him that xxxxx was ready to defect but wanted to disappear. He would like a boat half-full to be washed up on the Brighton beach and for a report to be put round that he had been seen going out in it. This meant that if any questions were asked or a demand was made for him by the Russians on the grounds that he had misappropriated funds, it would be necessary for the Government to say that they had no idea as to his whereabouts. Hayter seemed to doubt whether they would be prepared to give an answer of this kind.

So much for high-level approaches and approval. Hayter and Liddell are continuing their plotting outside the confines of the JIC meeting itself. And there is no doubt that this is case number two, as Liddell goes on immediately after to report on his discussions with White and Marriott on the American candidate. Borodin is under pressure: his local minders know something is afoot – but they have not secreted him or returned him to the Soviet Union, a lack of drama that is highly significant. These intermediate passages lead straight into the events of July 2, where Borodin turns up at Professor Florey’s at Oxford, as I reported in my previous bulletin. Was he being dangled by the Reds?

Intermediate Summary

I present an intermediate summing-up before proceeding to deliberations of the various government groups involved in deception planning. This was not a normal defection. Intelligence services welcome defectors because either a) they may constitute a propaganda coup; or b) they have valuable information to impart; or c) they may be precious assets that must not be allowed to fall into an adversary’s hands (as happened with many German officers and scientists at the end of WWII). If ongoing tapping of information is desired, agencies would prefer to maintain the asset as an ‘agent-in-place’, provided, of course, that there existed a mechanism for contacting the asset and extracting the information. Borodin did not fit into this scheme: he was actually pilfering secrets from the British. The plan did not make strategic sense from the side of the Foreign Office, nor did the operational aspects seem logical from the point of view of Borodin. In summary:

- This was not a routine defection, but probably a disinformation exercise that went sadly awry.

- William Hayter (in the Foreign Office) and Liddell probably cooked up a plan that lacked overt authorization.

- Liddell tragically involved Burgess and Blunt in his preliminary research.

- Goronwy Rees was at the centre of the action, but clumsily concealed his involvement.

- The plot for defection had fallen apart by the time Borodin was paraded at Oxford.

- Robertson and Milne tried to cover up the traces by planting misinformation.

The Chronology

And, to enable later correlation with the decisions of the governing bodies, I provide a timetable of ‘events’ (some of which may not be real, of course):

1948

Jan 19 Rees, Burgess & Blunt report on Russians acquiring industrial secrets (L)

Jan Soviets make overtures to Distillers & Glaxo over penicillin (CA)

Feb 4 JIC meets on Bacteriological Warfare. Borodin is buying up penicillin equipment (L)

Hayter asks about possibility of Borodin becoming defector (L)

Feb 18 Liddell discusses Borodin with Strong & Lamb of JSTIC (L)

Feb 26 BW Committee: Fildes discusses use of penicillin plant to create BW agents (L)

USA has sold manufacturing rights, and may refuse plant & know-how (L)

Mar 5 Borodin may need to be exception to policies on Soviet citizens (L)

Mar 11 Liddell informs Rees & Blunt about risk of penicillin plant being used for BW (L)

May 19 Florey contradicts Fildes, saying no harm in allowing Russians to purchase plant (L)

May 25 Borodin announces his intention to defect (KBL)

Jun 24 Liddell warns of unauthorized defections (L)

Jun 29 Liddell fobs off request by Naval Intelligence on defections (L)

Jun 30 Liddell and Hayter discuss Borodin’s urgent predicament (L)

Jul 2 Borodin has turned up at Florey’s, asking for assistance (L)

Marriott will go to Oxford to see Florey (L)

Borodin thinks he will be liquidated if he returned: promises to help (L)

Jul 20 Borodin agrees with Chain for provision of penicillin equipment for SU (S)

Aug (beg.) Purge of All Union Academy of Agricultural Science takes place (B)

Aug Burgess leaves for Ankara to stay three weeks with Philby (LO)

Aug 20 Borodin formally announces defection plan (KBL)

Aug 27 Borodin writes two letters of high treason (B)

Aug 28 Borodin defects (KBL)

Late summer Chain provides 100-page report on manufacturing penicillin, for Russians (CA)

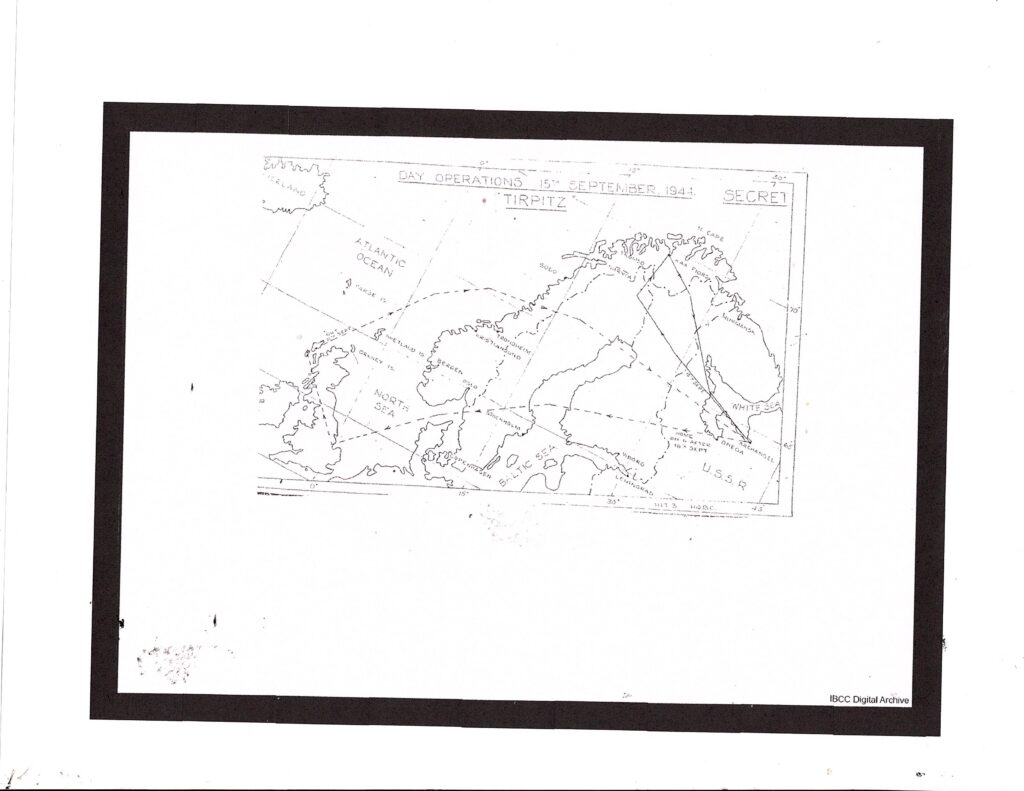

Sep 24-26 MI6-MI5 Conference is held at Worcester College, Oxford (MD)

Sep 30 Florey says Chain made improper contact with Soviets (L)

Chain has gone to Italy ‘for year’s holiday’ (L)

Oct 7 Ernst Chain marries Anne Beloff: Chains move to Italy (EC)

Oct 14 CIA writes report on Soviet penicillin capabilities (C)

Nov 23 Second CIA report on Soviet penicillin capabilities (C)

1949

Mar 7 Rees approaches Liddell about recruiting Borodin for Bennetts & Shears (KR)

B & S are negotiating with Chain for selling plant in India (KR)

Plans are underway for relocating Borodin to Canada (KR)

Mar 14 Liddell seeks Footman’s guidance on Rees’s business interest (KR)

Apr 4 Robertson meets Rees & Mason of Bennetts & Shears (KR)

Mason wants Borodin’s advice as he does not trust Chain, who is expensive (KR)

Jun 17 Footman recommends Burgess & Blunt for Oxford conference (KBU)

Jun 27 Mitchell invites Blunt to event in Oxford on September 11 (KBL)

Robertson is to approach Borodin for same (KBL)

Jul 23 Mitchell confirms to White about Blunt & Borodin for September conference (KBL)

Aug 9 Borodin & Burgess speak at conference on Russian affairs at Oxford (L)

Borodin is introduced by Klop Ustinov: Rees, Burgess & Footman heckle him (KBU)

Sources: B = Borodin

C = CIA

CA = Capocci (‘Cold Drugs’)

EC = Clark (‘The Life of Ernst Chain’)

KBL = Blunt PF

KBU = Burgess PF

KR = Rees PF

L = Guy Liddell Diaries

LO = Lownie (‘Stalin’s Englishman’)

MD = Muggeridge Diaries

S = Shertseva

Part 2

I now move on to inspect the various government units dealing with Cold War policy, concentrating on the opportunities for deception.

Cold War Deception Planning

The Post-War Planning Staff (PWPS) was set up in 1944 by Churchill and his Chiefs of Staff to do precisely what its title expressed – to consider diplomatic and military plans for an uncertain peace. As the project was handed over to Prime Minister Attlee after the war, the committee (now dubbed PWHP, Post-War Hostilities Planning) soon found itself challenged by a series of problematic topics, namely:

- The fact that a recent ally in the war, the Soviet Union (all too frequently erroneously identified as ‘Russia’) was the dominant threat;

- A sensitivity for Labour Party and public opinion that refrained from identifying who that threat was, a reluctance reinforced by a desire not to ‘provoke’ Stalin (which had echoes of the appeasement of Hitler);

- Uncertainty about the nature of future warfare, especially in terms of atomic and biological weaponry, and the effect the latter would have on attack and defence;

- The new realities about a diminished Commonwealth, and what that meant for defence obligations and industrial supply-lines;

- Watchfulness on what the new United Nations organization would bring, and concerns that it might be another League of Nations;

- Mixed feelings about the role of the USA as a partner, and its relationship with Western Europe, what with its distance and its recent decisions to exclude Great Britain from atomic secrets;

- The stringencies of post-war austerity, when Attlee’s demands for reduced expenditure came into conflict with his Chiefs of Staff and the Foreign Ministry (under Bevin);

- A host of new organizations and units that had to be involved in strategic planning in a Cold War environment, when the illusions of ‘peace’ made for more bureaucratic decision-making than was allowed in war.

Whatever plans evolved, they were subject to some extraordinary decisions that introduced noted Communists to the administration. Professor Blackett (familiar in these pages because of my recent coverage of Peter Astbury) gave professional advice that recommended unilateral nuclear disarmament. (Many of his papers have been carefully ‘lost’.) Professor Bernal was an outright Stalinist who was brought in for advice on scientific matters. As Julian Lewis meiotically wrote, in Changing Direction (p 224): “The involvement of Bernal in the revision of the Tizard report, notwithstanding his co-authorship of the original version, would appear to have been an early instance of the implications of the change in potential enemies not being fully thought through in terms of governmental personnel recruited during the war.”

The possibilities of misleading the enemy quickly became a key theme in hostilities planning. Tracking the decisions made by the deception groups after the war is, however, a complicated business. The core responsibility was maintained by the London Controlling Station (LCS), the unit that had been a spectacular success in WWII when it co-ordinated the activities of the TWIST Committee and the Double-Cross (XX) Committee in preparing and executing deception plans. It had been reduced to a rump of three members by 1946, including General Leslie Hollis, the Secretary to the Chiefs of Staff. The initial moves to resuscitate the deception staff are quite clear, but thereafter, one has to sift through the records of the Ministry of Defence (where the LCS reported), the Cabinet Office (which had a keen interest in the proceedings because of the Cabinet Defence Sub-Committee), and the Foreign Office (which regarded deception in peacetime as highly relevant to foreign policy, and whose officials, Harold Caccia and William Hayter, were the chairmen of the Joint Intelligence Committee in the relevant years). A small group called the ‘Hollis Committee’ was charged with supervising the LCS, taking over the responsibilities of the declining wartime ‘W’ Board – although the latter refused to die in the minds of some persons. One can find many common documents in all three sets of archives, but each retains its own idiosyncrasies and commentaries, and together they often express contradictory statements about events and decisions.

The Joint Intelligence Committee (as it was upgraded to in January 1948, having before that existed as the Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee – an important differentiation in protocol) was the kernel of the decision-making. Its minutes are sometimes highly detailed, but not all of its deliberations were recorded (as Liddell’s diaries prove). Thus there could be three classes of decisions made, namely i) formal decisions appearing in the minutes; ii) decisions that were secret and confidential, and thus off the record, and iii) decisions and actions that were not authorized by the Committee, but may have been hatched from its discussions. We owe it to those diaries of Guy Liddell, who was a regular attendee at JIC meetings, normally substituting for Sillitoe, and was a confidant of both Harold Caccia and William Hayter, for a healthy sprinkling of commentary on what was said within and without the meetings, including the occasional summarization of items that were ‘off the record’. (I analyze that commentary below.) Liddell was also a regular member of the JISC Deputies Committee, which met less regularly, and thrashed out items to assist the full JISC or JIC meetings.

The early moves are straightforward to track. In June 1946, the Service Chiefs, conscious of the new Soviet threat, recommended setting up a Future Operational Planning Section. The following month the Joint Technical Warfare Committee concluded that atomic and biological weaponry would constitute a major change in how war was conducted. At that time, the Cabinet Defence Committee approved a report from the Tizard Committee that went into detail what the effects of atomic warfare would be. In September, the Committee of Imperial Defence was replaced by the Cabinet Defence Committee, and a new Ministry of Defence was set up in January 1947. In September, William Hayter (an important figure in this saga) was chosen to replace Harold Caccia as Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee. The Foreign Office then stepped in, advocating greater preparedness in the light of Soviet moves, and, on October 16, Foreign Minister Bevin convinced the Cabinet of the necessity of having a British atomic bomb. That same month, the Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee (under Hayter) was charged with assessing possible Soviet attacks.

Back in September 1945, Leslie Hollis (whom I shall refer to as ‘Hollis’ hereafter, since the distinction between Roger and Leslie is now clear) had written a paper that emphasized how deception would be necessary in times of peace, as preparation for possible war. In May, 1946, Stewart Menzies, the MI6 chief, had recommended the revival of the LCS, arguing, rather provocatively, and very significantly, that Soviet spies (which he described as ‘pervasive intelligence gathering channels’) might be manipulated to ‘provide suitable channels for the transmission of deception material to the Russians at a later stage’. After the inevitable conflict between communism and capitalism (an erroneous contrast, as I have written elsewhere) was clarified early in 1947, Prime Minister Attlee came around from his appeasement of Stalin to a more aggressive approach. Thereafter, in March the Cabinet agreed to an active and bolstered London Controlling Section, including that supervisory committee named after Hollis himself, and the LCS began to draw up new proposals for deception in peacetime, in the belief that misleading the Soviets about Britain’s capabilities in atomic and biological warfare might deter the foe from aggressive action. The Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee approved this set-up in July 1947 – rather belatedly, it would seem, and perhaps grudgingly, as its approval had not apparently been sought.

The LCS struggled to keep its discussions tight and secure. Deception in peacetime was an entirely different proposition from that in wartime, when strict information controls and a highly focused campaign against a known enemy abetted some daring plans. It began by thinking that it should exaggerate the country’s war potential in time of peace, but worried whether that might spur the enemy to greater vigour. That policy soon evolved into one of ‘deterring the Russians from armed aggression’ (July 29). It encountered obstacles. It started defining a deception policy for Atomic Research and Production, but then realized that it did not have enough scientific competence, and wanted to set up a scientific advisory committee. Tizard was not enough. With the recent experiences of Blackett and Bernal fresh in their minds, that was a cause for concern. In September, it broadened its scope to include Weapons of Mass Destruction generally, thus including biological warfare, but then realized how little it understood about Soviet competence in this field.

Further complications arose. In October 1947, the JIC’s Hayter urged for more deception to counter communist infiltration, which was evident from the multiple trade missions under way, where the Soviet Union hoped to acquire strategic technology (such as jet-engines). Menzies wanted more co-operation with SOE’s planning staff, in itself a bizarre observation, even while he carelessly forgot that SOE had actually been dissolved in 1945, with its rump incorporated into MI6. The LCS’s political stance was not helped that same month by the Foreign Office’s Christopher Mayhew stating that Britain should attack capitalism as well as communism, while Hankey openly deplored any appeasement of the Soviet Union. When Lord Portal, Controller of Production (Atomic Energy) at the Ministry of Supply, was approached in November concerning deception on atomic matters, he immediately insisted that the Americans be involved. (Two later visits to the USA, in 1948, by Hollis, and then Drew and Wild, turned out to be fruitless.) Portal’s sidekick, Perrin, judged that the Soviet Union was way behind the USA and the UK in atomic weaponry capabilities, an opinion that would reinforce the general conclusion that the Russians would not be ready for war until about 1956. MI5 and MI6 (whose leaders, Sillitoe and Menzies, attended meetings, but were not actually members of the LCS) were charged with plans for exaggerating the nation’s strengths.

Early in 1948, a new challenge appeared. The Cabinet decided to create an Information Resource Department in the Foreign Office, a secret unit dedicated to anti-Soviet propaganda. That raised issues of how propaganda related to the LCS’s mission of deception, and who was in charge. Further second thoughts followed. On February 3, Drew of the Cabinet Office questioned whether the Committee had a sound idea of whom in Moscow it was addressing with its deception plans. (It clearly had not considered that: some very arrogant and dismissive statements about the unsophistication of the Russians can be found in the published minutes of LCS meetings.) During 1948, fresh overseas issues raised their heads. A deception exercise in Belgium had prompted uncomfortable questions from Soviet contacts: how should they be handled? The operations in Palestine demanded real-time war deception strategies. In September, Ivone Kirkpatrick of the Foreign Office (an unlikely champion of SOE-type activities in Eastern Europe) asserted that his IRD was the only body charged with carrying out ‘cold war’, and he also emphasized the role of the FO’s Russia Committee as the primary planning staff. In November, the LCS had to issue a new paper on the ‘Western Union’ – the outcome of the Brussels Treaty of March 1948, with its separate charter of guarding against armed aggression in Europe. Attlee’s Cabinet was reluctant to have the Soviet Union identified as the potential enemy in any documentation. In the autumn of 1948, the Hollis Committee had to sort out the relationship of the LCS with a murky body called VISTRE – Visual Inter-Service Training and Research Establishment – which was also involved with deception. By the end of the year, the LCS was feeling besieged, and Hollis began to question whether deception had any viable role in peacetime.

Thus it appeared that, by the onset of 1949, no European deception activities (apart from in Belgium) had been carried out. Yet a very curious minute had appeared in June 1948, as shown by DEFE 28/118. In his progress report on the fourth of that month, Colonel Wild explained that the LCS no longer used the idea of ‘double agents’, drawing on the fact that ‘a very limited number of double agents have been started, but in each case they have terminated through one cause or another before any useful build up has been achieved.’ This is, to me, an astounding admission – which must have derived from Menzies. On which authority had these agents been activated? Who were they? How had they been chosen? Why could they have been trusted? Whom did they contact? What had caused them to be ‘terminated’? Had any damage been done because of the exercise? Maybe the remainder of the Committee were too overwhelmed by the complexity of the operation that they did not know what questions to ask. If they did discuss the problem, any record of their debate was suppressed.

The LCS had one important other occupation at this time. Grigori Tokaev had defected in October 1947, and his knowledge of the Politburo, and Soviet military plans of weaponry, had prompted the LCS to engage in deep consultations with him as to how they might rock the Soviet cradle. Much of this debate was focussed on the idea of ‘deception’, but the nature of such a project was more on how to mislead Stalin and his gang on potential dissensions within the Soviet Empire (particularly in the Caucasus, from where Tokaev came), and to provoke rivalries within the Kremlin, than it was to deceive the foe on Western atomic or bacteriological warfare capabilities. The planning went on for years, with Tokaev (like all defectors) probably using his imagination too wildly and being criticized for it. He thus influenced the atmosphere at the LCS and the Hollis Committee, but his very public story (now that the relevant DEFE archives have been released) was tangential to what happened to Borodin, whose tale has been permanently muffled.

‘Double Agents’

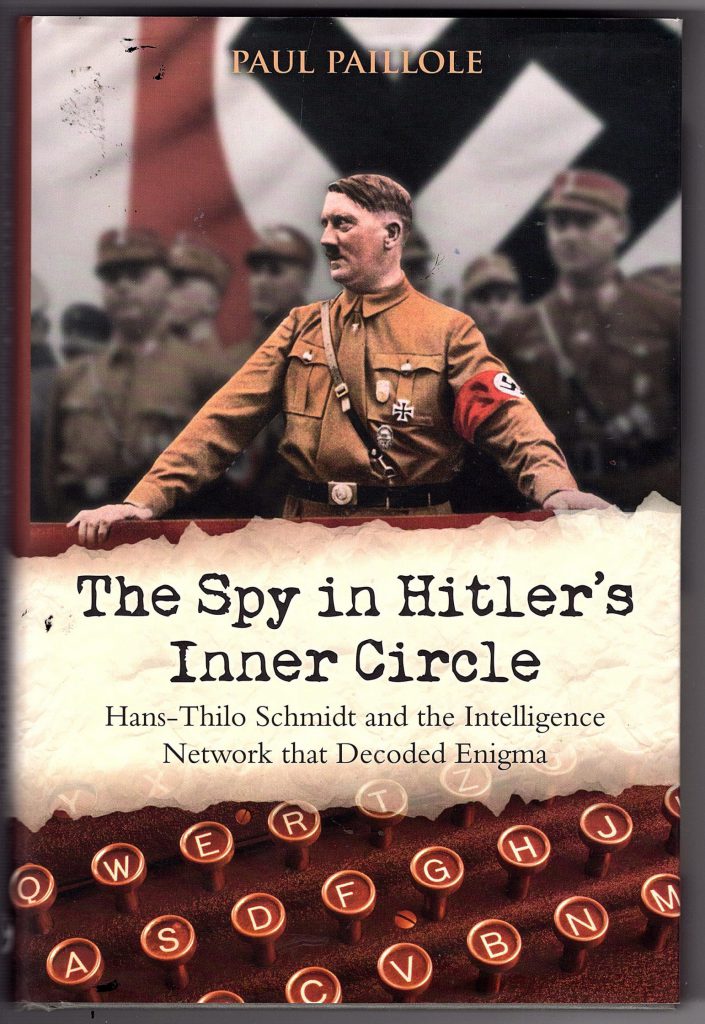

How would ‘double agents’ be used against the Soviets? It is timely to recall what was unique about the WWII Double-Cross operation, why it was successful, and why it almost failed spectacularly. As I have reported before, John Bevan, who led the LCS in wartime, disapproved of the term ‘double agents’, since it necessarily described persons who were by definition working for opposing forces, and whose true loyalties were thus unknown. He preferred ‘special agents’, or ‘controlled enemy agents’. In fact, his troupe of performers was a mixture of penetration agents (such as Garbo and Tricycle, whom the Abwehr trusted but whose loyalty to the Allies was firmly believed in by the XX Committee), spies parachuted in by the Abwehr (such as Tate, and Mutt and Jeff, who were either easily ‘turned’ ideologically, or kept under strict control to ensure they had no unauthorized communications with the Germans), and fake identities created under the illusion that they were sub-agents recruited by the spies. The deception exercise was successful because it was tightly focused on one objective – misleading the Germans about the location of the continental landings, and MI5 was able to monitor the effectiveness of its disinformation through ENIGMA intercepts. Yet it played only a supportive role in the creation and maintenance of a dummy army that was being prepared to land in the Pas de Calais. And it should certainly have been questioned by the enemy, because of such absurd practices as Garbo’s two-hour transmission at the eleventh hour, when the Reichsssicherheitshauptamt (which had absorbed the Abwehr by then) should have concluded that British detection and direction-finding of illicit wireless could not possibly be that feeble to have overlooked such broadcasts. (see https://coldspur.com/the-mystery-of-the-undetected-radios-part-8/ for a full analysis.)

So, given that, in peacetime, the communications of such agents could not be controlled, in what category were the ‘double agents’ to whom Wild referred? Were they agents who had penetrated the RIS (Russian Intelligence Services), and were now in contact somehow with their ideological controllers, presumably MI6? Were they contacts in place in the Soviet Embassy in London, to whom false information could reliably be fed because of legitimate diplomatic or business relationships, whether they were intended defectors or communist loyalists able to be manipulated? Or were they perhaps British intelligence officers and diplomats who pretended that they had a loyalty to the Soviet Union, and could therefore feed their Soviet contacts with false information as well as a careful selection of factual chickenfeed? The record does not say: only that they have been ‘terminated’, which probably does not mean that they have been murdered, but that they have simply been dropped as a possible channel.

That third scenario is very alarming. What if those intelligence officers had in fact made false claims about their loyalties, were in truth committed soldiers for Stalin, having declared to MI5 and MI6 that they had foresworn their temporary and misguided service to the NKVD in favour of a renewed dedication to the imperial cause? We know, for instance, that Anthony Blunt had been caught red-handed passing over secrets from MI14 to the Soviets in 1944, but was unpunished by the action. It was certainly part of the deal that, to conceal his assumed change of heart, he had to provide occasional secrets to the Soviet Embassy to protect himself. Thus my recently developed theory that Philby, Burgess and Blunt effectively turned themselves in after the Nazi-Soviet Pact of August 1939, and were then allowed to tunnel into MI6, the Foreign Office, and MI5, takes on extra life. Yet the dating of Wild’s observations in June 1948 seems rather premature for invoking the trio: after all, Philby was in Turkey at the time, Burgess’s visit to Istanbul came after Wild’s disclosure, and the antics between Liddell, Burgess and Blunt started only in the first half of 1948.

The first scenario is very unlikely, since penetration of Soviet intelligence services by persons with allegiance to a foreign power (as opposed to those who may have become jaundiced during service) has probably never happened. The second scenario, that they were probably Soviet spies, had however been endorsed by Menzies back in 1946, as my note above suggests. He had then indicated that MI6 knew about some prominent Soviet agents, and that they might be manipulated to pass on ‘intelligence’ which their bosses were looking for. His remarks were submitted by Leslie Hollis to the JISC in May 1946, and are worth presenting, since they show the MI6 chief at his most bureaucratic and opaque:

In the course of the past eighteen months, various contacts have been established with Russians seeking intelligence about British activity, policy and strength. These contacts offer opportunities of increasing our knowledge of the Soviet intelligence services and the direction of their effort. If adequately developed, they may provide suitable channels for the transmission of deception material to the Russians at a later stage. Whatever may be the use to which these contacts are put, the first requirement (without which they will certainly wither away) is machinery designed to provide and approve information that can be passed to the Russians.

The machinery set up for similar purposes during the war worked well, and it is submitted that our peace time needs would best be served by similar machinery functioning on a smaller scale.

What was Menzies talking about? He seemed to be suggesting that contact with a whole cadre of probable Soviet spies (‘Russians seeking intelligence’) has been maintained since before the end of the war, and that the commitment of these characters to their cause was so flaky that they might instead be used to channel disinformation back to their masters. What ‘adequate development’ means is uncertain, but Menzies appears to be under the impression that MI6 alone could judge the true loyalties of these persons, and that none of these candidates would spot what is going on, or would tell Moscow about the game that is afoot. Did he really believe that a technique such as the XX Operation would lend itself to the conditions of the Cold War, or was he simply repeating what he had been told by one of his subordinates? And then that awful beloved word of the Whitehall elite – ‘machinery’, as if all this works like a well-oiled engine, when in truth anything that happens relies on a complex set of relationships, back-room deals, rivalries, buck-passing, and concealment.

What is also astonishing is that the cream of Britain’s intelligence staff did not appear to question what Menzies had introduced. ‘Who were these Soviet spies?’, they might have asked. Were they perhaps members of trade missions looking to purchase critical technology? As mentioned earlier, the probing by Soviet officials with authority to visit industrial premises was a recognized problem at this time. In a diary entry for November 3, 1947, Liddell refers to the penetration by Communists in scientific and research establishment, of which R.A.E. Farnborough and T.R.E. Malvern were the worst. It is possible, therefore, that one of these Russians had made an approach to someone they considered ‘friendly’, who in fact had reported their overtures to MI5. If one of such had been encouraged to offer information that had not been asked for, the Soviet official might well have become suspicious. But Menzies was looking retrospectively over the past eighteen months: the phenomenon of potential spies in the factories was a recent one.

Another possible category allied to the ‘Soviet spies’ group could be Soviet citizens who had ‘defected’ in the British Zone of West Germany, or in Austria. In a very muddled note reporting on a JISC meeting on October 22, 1946, Liddell had referred to ‘renegades’ (presumably persons not important enough to be deemed ‘defectors’) who had turned up in Germany, and might be considered for espionage or counter-intelligence purposes. Someone on the committee had suggested bringing ‘a limited number’ (a weaselly phrase) to this country, on the basis that, if they were given ‘some inducement and a home here’, some information might be acquired. Liddell sensibly shot this down, as it would be a very two-edged weapon, and ‘invited the Russians to plant people on us’. The country had enough infiltration already, of course. Any suggestion for using such ‘renegades’ to pass deceptive information to the Soviets would also have been haphazard, and maybe disastrous, as Moscow would have wondered why such persons returned to their native land with unexpected intelligence. The channel had to be trustworthy.

In any event, one might gain the impression that, by June 1948, the notion of ‘double agents’ was well and truly dead. On the other hand, it could have been a feint. As I have suggested, many things that were discussed at the meetings of the LCS were not recorded, and it might have been with the goal of misleading posterity that some items were omitted. The notion of deception exercises using other means was still alive, however, and it seems that the JIC may have taken over the baton as the LCS started winding itself down. How would it accomplish its goals without using some sort of intermediary?

The JIC Chairmen

William Hayter was the second in a series of self-regarding but not very impressive Chairmen of the Joint Intelligence Committee after the war, succeeding Howard Caccia, who held the post from November 1945 to August 1946 (a very short time) and being followed by Patrick Reilly, who served (according to the official history) from November 1950 to April 1953. Yet even these dates are unreliable. In his Appendix 1 of his official history of the JIC (from which the above statements derive), Michael S. Goodman has Hayter in the post until November 1950 when it is clear from Hayter’s own memoir that he left in November 1949. (Wikipedia states that Hayter did not become Chairman until 1948: the facts are elusive.) Goodman is intuitively flattering about these appointees, asserting that Victor Cavendish-Bentinck was able to instill ‘in the FO a recognition that it should provide top class candidates for JIC Chairman’, adding that the careers of each benefitted from the role: ‘ . . . certainly a spell as the JIC Chairman was good for future progression’. Goodman fails to analyze how qualified Caccia and Hayter were for job he characterizes as something of a stepping-stone, although he inadvertently sheds some light on their relative inexperience by stating that ‘unlike his predecessors, Reilly had already had a varied and in-depth involvement with the intelligence world’.

Goodman’s study is of little use in the context of this analysis. His Index contains no mention of ‘The Hollis Committee’, ‘The London Controlling Station’, let alone ‘Borodin’, ‘defectors’ or even ‘double agents’. He lists an enormous range of sources, but has overlooked Guy Liddell’s diaries, which often breathe some life and gossip into the dry-as-dust formal archives, and even reveal JIC discussions that were ‘off the record’. Goodman describes Hayter as ‘another high flyer’, yet writes nothing about what his contribution to the JIC was, apart from the fact that each Chairman had other responsibilities, such as leading the Permanent Under-Secretary’s Department (PUSD), and thus liaising with MI6, GCHQ and MI5. In his 1974 memoir, A Double Life, Hayter never mentioned the JIC, but did refer obliquely to his role by describing it as head of the ‘Service Liaison Department’, the head of which ‘sat in with the Joint Planners under the Chiefs of Staff, and dealt with all Intelligence questions’. He declared that the appointment took place in August 1946.

Yet, in a revealing aside that shows Hayter’s inexperience, the Chiefs of Staff, with a familiar but deplorable obsession with rank, had complained that Hayter’s position as Counsellor was too junior to collaborate with them. He had already been moved sideways from the Washington Embassy to the less prestigious General Department in the Foreign Office in London, a transfer that Hayter was not happy about. After the Chiefs’ complaint, Hayter wrote that he was given ‘a totally unmerited promotion’, which apparently satisfied the top brass. Hayter also described his disappointing move, at the end of 1949, to become Minister at the Paris Embassy, a transfer he first learned about through ‘rumours’, suggesting that his period with the JIC had not been totally auspicious, and that he was perhaps not yet the lofty flier that Goodman described him as being. Appointing someone with such mediocre credentials to chair such an important body was indeed a strange decision.

Hayter quickly built up a strong relationship with Liddell, however, and he frequently consulted him on topics on which he felt exposed. An analysis of Liddell’s diaries shows some sub-currents not evident from the official records. I intersperse his accounts with excerpts from those JIC minutes and reports.

Guy Liddell’s Accounts

By May 1946, Guy Liddell had built up a strong relationship with Harold Caccia. They used the forum of the JISC to discuss topics of shared interest. On May 30, when they offered each other insights on the vexing matter of Cabinet secrets being leaked to the newspapers, Caccia encouraged Liddell to attend meetings more regularly. He wanted more open discussions, and probably felt a bit intimidated by the Services’ Intelligence Chiefs, who occasionally expressed their resentment that the Committee was being led by a young Foreign Office chap. It was Caccia who wanted a Security Section established in the Foreign Office, and who looked for officers from MI5 and MI6 to help staff it (with Carey-Foster becoming the eventual head). Yet Caccia’s controversial departure (or ouster) receives no mention in Liddell’s diaries, primarily because a large section dated August 2, 1946, significantly headed by ‘JIC today’, has been completely redacted. Liddell must surely have made some comments that were considered disrespectful or confidential by the weeders. The next entry on Caccia, dated October 2, reports solely that MI5’s Ede had been turned down for the FO security job.

Thus Liddell had to build up a new alliance with the incoming William Hayter. He and Sillitoe took Hayter to lunch on January 20, 1947, and it is clear that Liddell was more impressed by Hayter than he was (say) by General Hollis, who comes across as something of a buffoon. The new JISC chairman seems to be sympathetic to MI5’s needs: he is supportive of MI5 representation in SIME (Security Intelligence Middle East), and he is even tougher on the question of Professor Blackett’s reliability. In February 1948, he welcomes MI5’s comments on a JISC paper on Russians penetrating secret establishments. Thus the pair was developing a strong alliance of civilians among the military brass, who continued to show their confusion about some elementary matters.

Hollis’s influence nevertheless increased. During the summer, the replacement of the W Board by the Hollis Committee became official, although at the JIC on June 25 some peculiar views were aired, including this particular statement from the Director of Military Intelligence, who was clearly out of his depth. Liddell reported:

The DMI raised the question of Russian defectors in the British zones of Germany and Austria. He said that he could get little help out of the Americans, who were passing all the bodies on to the British after a short interrogation. The numbers were increasing and he was anxious to find some way of disposing of the bodies. He could not send them back: firstly, because this would discourage other, and secondly, because after interrogation they would have valuable information to impart to the Russians. The Secretary then handed round a note on the Ministry of Labour scheme for bringing D.P.s into this country. It was suggested that possibly Russian defectors disguised as Czechs or Balts could be included.

Liddell probably attended more JISC meetings than did chairman Hayter, whose memoir shows that he engaged on some hectic overseas travel during his tenure (including a visit to the Macleans in Cairo). Moreover, Hayter’s position became under attack. He received a challenge in October 1947, when Sir Douglas Evill, who had been commissioned to create a report on British Intelligence organizations, tried to have the post of chairman, customarily from the FO, occupied permanently by a Services Director, in rotation. “Evill probably wants the job for himself”, observed Liddell. Hayter remained on the sidelines of the debate, but survived, and Liddell and Hayter continued to have their off-campus discussions about the threat from the Soviet Union, and other matters. Crucially, at this time, what with the disturbances in Palestine, the application of deception measures for circumstances of actual conflict, though not war, gained greater attention. Early in 1948, Hayter and Liddell had their way when Blackett was turned down for the post of head of the Atomic Research Committee, and Hayter must have felt confident enough of his stature to criticize openly Evill’s report as ‘cumbersome’.

It is now that the crucial Borodin business came to the fore. How much did Liddell know about Borodin before the distress call came from Rees on January 19, 1948? The impression he gives is that it was a surprise that Borodin was nosing around Bennett & Shears. Had MI5 not been tracking him since his recent arrival? (He had returned to Moscow from the USA only in December 1947, so he cannot have been in the country long.) Who would have introduced him to the firm? Moreover, Rees, working for MI6 part-time, must surely have informed his bosses of the presence of multiple Russians at the factory, and they must in turn have been keeping Liddell informed. (One of those Russians was surely an MGB man keeping a close eye on Borodin.) The elevated concerns about snooping Russians in sensitive locations had been a pressing issue for months. Why otherwise would Skardon have been sent in in such a fortuitously timely manner? Liddell must surely have known about the visit in advance. To pretend otherwise suggests that Liddell was not in control of his troops.

The matter of official tracking of visits by Russians to factories should have been a pressing one, yet the records are curiously vague. As far back as January 1947 the War Office had proposed to the JISC much tougher restraints on any visitors from ‘Russian [sic] or Russian satellite countries’. Brigadier Hirsch even made the shocking recommendation that ‘prospective visitors should, at the same time as applying for visas, declare the industrial concerns they wished to visit, and the visas should be endorsed with permission for them to do so.’ It would seem an eminently obvious policy to pursue, but, from the minutes, the committee ‘was unable to accept the War Office proposals, for the reasons as stated in the discussion’. Leading those reasons would appear to be the fact that some visitors were in the country already, on two-year missions, and while they could be stopped from seeing work on the ’Secret List’, it ‘would not be possible to prevent them from seeing factories’. This seems a pusillanimous decision, but it may not have been revisited for a long time. Pontifex must surely have been on that ‘Secret List’, however. What was the state of Borodin’s visa, and how had he managed to find his way there a few weeks after his arrival?