I ♥ Coldspur Fridge Magnet

I received the above item in the mail a few weeks ago – completely out of the blue. It arrived from Greece, and the envelope included a packing-slip that informed me that the item had been bought from Mundus Souvenirs on Amazon Marketplace, and that the buyer’s name was ‘David’. The condition of the item was described as ‘New’, so I was happy that I was not the beneficiary of a re-tread. But who could the semi-anonymous donor be?

I know of only three ‘Davids’ who are aware of coldspur, and also have my home address. None of them is renowned for wearing his heart on his sleeve, but maybe each does adorn it on his refrigerator. It was a superbly innovative and generous gesture, and I determined to get to the bottom of it.

Maybe coincidentally, I happened to hear from David Puttock soon after. David lives in Hamilton, Ontario. We go back a long way: we studied together in the Sixth Modern at Whitgift, and we both went on to read German and Russian at Oxford, David at New College, I at Christ Church. We have met only once since 1968 – at a Gartner Group conference in Toronto ca. 1990, but have maintained a sporadic email correspondence, and the exchange of Christmas cards (heathen that I am), since his retirement. And, indeed, when I asked him about the magnet, he admitted that he was the benefactor.

David told me that he found the item by googling ‘coldspur’, and that the amazon link appeared on the first page of the selection. When I performed that function, however, amazon was nowhere to be seen, but my site gratifyingly appeared before the township of Coldspur, Kansas. The magnet was probably intended for the good citizens of that community, who may think they have stumbled into an alternative universe if they mistakenly look up www.coldspur.com. In any case, those coldspur enthusiasts who feel an urge to have their ardour more durably expressed know where to go. I vaguely thought of buying a stock of magnets, and making an arrangement with Mundus to send them out to well-deserving readers of coldspur, those who post congratulatory or innovative posts in response to my bulletins, but it all sounded a bit too complicated. For about $8.00, you can buy your own. (The SKU is mgnaplilo103600_1, in case you have difficulty. See

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08RZBNVJ3?ref_=cm_sw_r_ud_dp_F2MAMV1SC49R799FBKWJ.) Lastly, I am of course delighted with the magnet, as my enthusiasm for coldspur is boundless. But what about David? Did he purchase one for himself at the same time, for proud display to his friends on the Puttock refrigerator? I hope so.

Contents:

Introduction

Sonia and The Professor

Operation PARAVANE

The Coldspur Archive

‘Hitler’s Spy Against Churchill’

An Update on Paul Dukes

The PROSPER Disaster

2022 Reading:

General

Spy Fiction

‘The Art of Resistance’

‘The Inhuman Land’

‘Secret Service in the Cold War’

‘A Woman of No Importance’

Language Corner

Bridge Corner

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

Since I spent two weeks in Los Altos, California, in June, staying with our son and his family (whom we had not seen for two-and-a half-years), my research has been somewhat lagging. So I thought for my July bulletin I would perform a mid-year round-up instead. Not that there is much new material to report, but I usually find a few points of interest when I carry out this exercise. Moreover, the exercise of writing it all up helps to clarify my opinions on these research topics, and acts as a kind of journal and memoir should posterity (i.e. my grand-daughters) ever want to track down what was really going on.

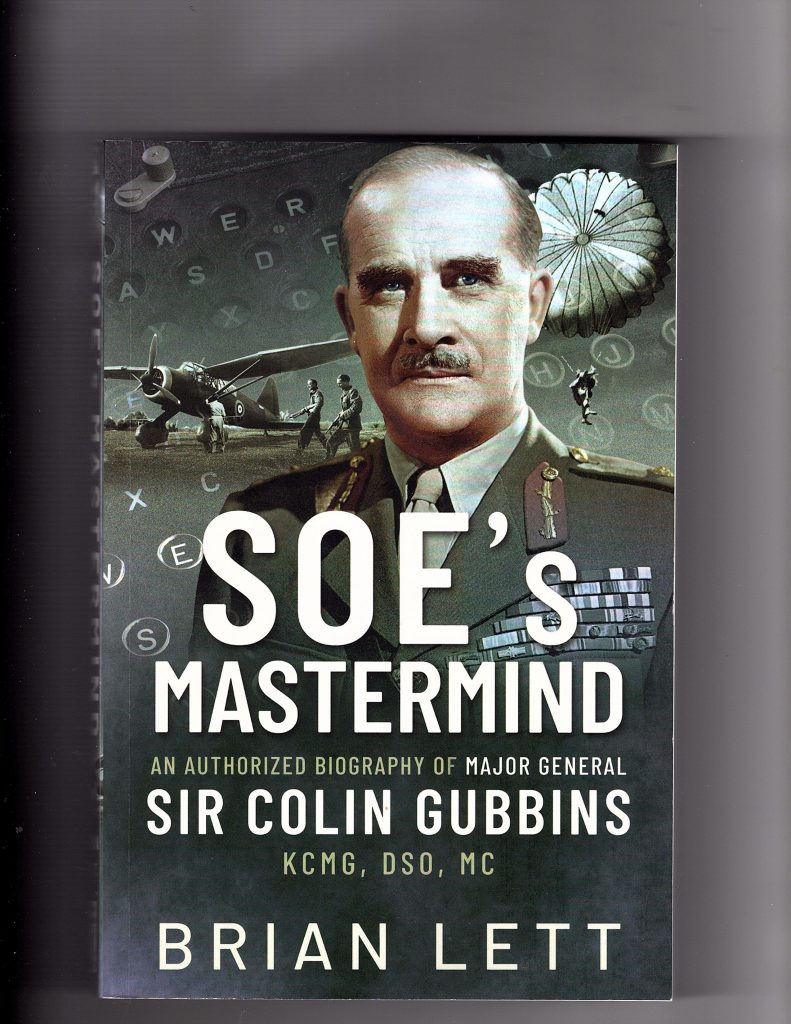

I suppose that I must record a certain disappointment that my research in the first half of the year has resulted in a resounding tinkle. I would have thought that the disclosures that Henri Déricourt had definitely been recruited before he arrived on British shores in 1942, that SOE was harbouring a dangerously vulnerable cipher officer in George Graham when it set up its mission in Moscow and Kuibyshev in 1941 and 1942, and that Graham was later driven to madness, that M. R. D. Foot’s history of SOE in France is evasive and unscholarly, since Francis Suttill almost certainly made two visits to the United Kingdom in the months of May and June of 1943, shortly before he was arrested, that Peter Wright behaved in a scandalously irresponsible and mendacious manner when he claimed that Volkov’s hints in 1945 pointed to Hollis rather than to Philby, and that Colin Gubbins was not the innovative hero that his biographers have made him out to be, might have provoked some rapt attention in the world of spy-watching and intelligence connoisseurship. While I have received several private messages of support and approval, I have seen no public recognition – nor any challenge to my theories expressed. If I cannot receive due publicity for my pains, I would rather have someone step up and protest that my theories are hogwash, so that I could at least engage in a serious discussion about these outstanding puzzles.

If I were resident in the United Kingdom, I would eagerly take up any invitation offered to me to speak at any historical society that showed an interest in my subjects of study. I have undertaken a few such activities in the United States, but the good citizens of Brunswick County, while listening politely, are overall not particularly interested in predominantly British spy exploits of the 1940-1970 era.

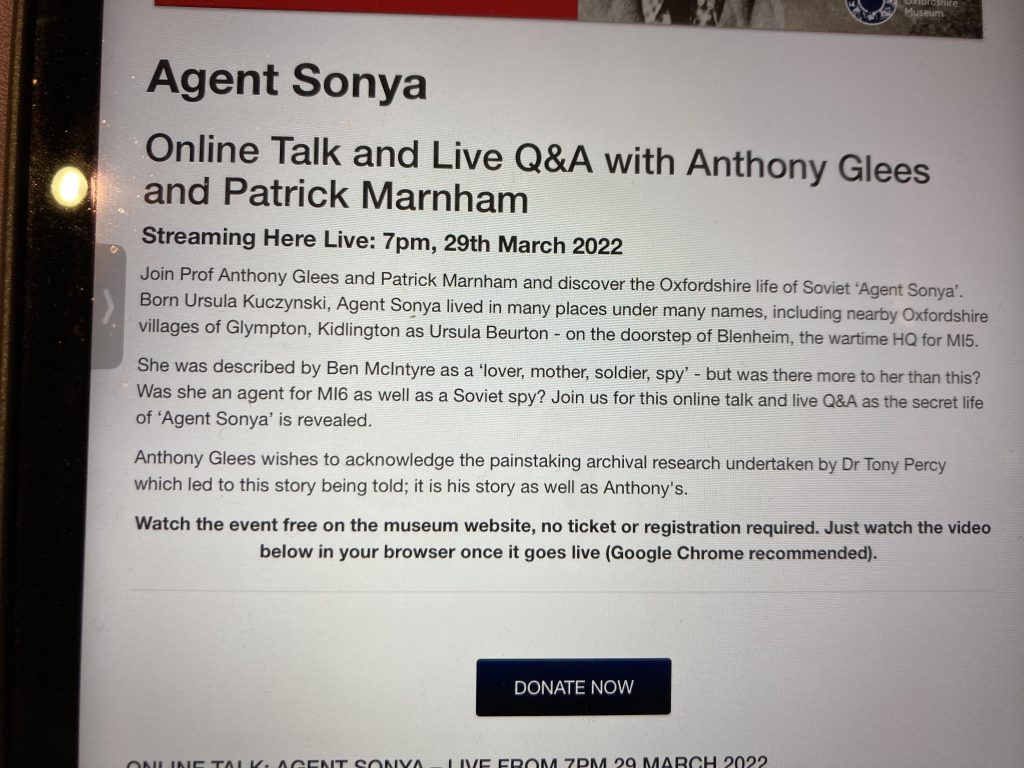

Sonia and The Professor

Thus it was with considerable excitement that I heard from Professor Glees a few months ago that he had agreed to speak to an historical interest group in Oxfordshire (the Soldiers of Oxfordshire Museum) about Agent Sonya (or Sonia), as I imagined this would generate some interest in coldspur. When I looked at the promotional material, however, I was slightly perturbed by the rather two-edged endorsement of my research. While Professor Glees spoke glowingly of my investigations, his overall message was that I was in reality a side-show to his own endeavours. “This is not just my story, it is his.” Considering that, according to my analysis, Glees has not written a word about Ursula Kuczynski since his book in 1986, I considered this observation rather troublesome. I was further dismayed when I listened to and watched the recording of his presentation. Coldspur gained only one mumbled acknowledgment. While the promotional material for the talk highlighted Ben Macintyre’s biography Agent Sonya as a teaser, Glees ignored completely my careful review of the book, which demolishes most of the falsehoods that Macintyre promulgated about his subject.

Furthermore, I believe that Glees grossly misrepresented my researches, and dug himself a hole when attempting to answer a question as to whether Sonya had been a ‘double agent’. Glees seems to be under the impression that it is he alone who has revealed that Sonya had been ‘recruited’ by MI6, but that her intentions may not have been entirely honourable. (“I made it very clear that the archival research aka ‘the trees’ was yours, not mine, & the thought that Sonya was an SIS agent aka ‘the wood’ was mine,” he wrote to me afterwards.) He appeared to be unaware of what I had published on coldspur back in 2017, when I showed that MI6 had been fooled by Sonya when she agreed to their terms in order to be exfiltrated from Switzerland, and her life effectively saved. She had no intention at all of serving British Intelligence loyally, and would have had to contact her Moscow masters in order to gain approval for the scheme of her marriage to Beurton, the resultant adoption of UK citizenship, and her subsequent escape to England. The fact that she then became a courier for Klaus Fuchs proves that she never intended to be of any useful service for Menzies and his pals, who were grossly hoodwinked. I do not know where Glees derived the illusion that it was he who prised out these discoveries.

When I gently protested to Glees about his misrepresentations, and his failure to give credit to my discoveries and analysis on coldspur, he was very patronising and dismissive, exaggerating his own ability to see ‘the woods’, and suggesting that I had been concentrating on ‘the trees’, while at the same time he compounded his forgetfulness (or inattention) over what I had written. In a responding email he wrote: “As I explained the release of KV 6/41 a few years ago, found by you, dissected by you, and read by me, thanks to you and esp[ecially] the Farrell letter which I ‘decoded’ to you, if you recall, & was imo [in my opinion] key to solving the riddle. You’ll remember that I put this to you, along with the notion that the simple fact this file from 1941 existed, showed that MI5 were aware of Sonya’s existence in Oxford.”

But that is absurd. Glees did not ‘decode’ the letter for me. My researches in 2017 showed quite clearly that MI5 was aware of Sonya’s presence in Oxford at that time. Glees’s ignorance is dumbfounding. I did indeed introduce him to the file KV 6/41, which Glees appears to believe constitutes an exclusive exposure of Sonya’s activities. But it stands out because it is the only digitized file on the Kuczynskis: I had inspected the others at Kew several years ago, and published my analysis of them. I tried to explain to Glees that these other files revealed much of her goings-on in Oxfordshire, but he did not want to listen. I am confident that he has not looked at these files (although I have shared my notes on them with him).

And his claim that he alone can see the ‘big picture’ (he is a ‘woodsman’, while I am only a ‘trees’ man’) is insulting and patently absurd. His distinction between different aspects of the forest was nevertheless exceedingly murky: in his talk he made some bizarre assertions that Sonya must have developed some useful contacts within the Oxford intelligentsia, without offering a shred of evidence (‘the trees’, about which matters he was punctilious when he was my doctoral supervisor).

He then accused me of behaving like M. R. D. Foot (the historian of SOE) wanting to stake proprietary claims about a sphere of research, and trying to prohibit anyone else from stepping on his turf. After saying that “No one will want to engage with someone who fires off furious emails at the drop of a hat”, he wrote:

You know I’m one of the biggest admirers of your work & have always made others aware of it. It’s easy to be cross & resentful, as MRD Foot, for example, excelled in being (an academic version of ‘outraged of Tonbridge Wells’) but much better to be charitable, particularly where you ought to be as here. You’re really way off beam here. Few people have done more to bring your work to the attention of others but at the end of the day it was I, and not you, who were giving this talk.

I graciously accept the compliment inherent in this, but on this public occasion Glees did all he could not to bring my work to the attention of others. Second, my email was not ‘furious’: it was regretful and calm, and tried to discuss real issues – which Glees side-stepped. (I could make the email available to anyone who is interested.) His reaction merely points to his own prickliness and egotism. Moreover, I am not sure where ‘charity’ comes in. Am I really supposed to be grateful for Glees for mangling my research. and failing to give me proper credit? And perhaps I should be pleased to be compared with M. R. D. Foot, a famous ‘authorized’ historian?Yet I could really not harbour any such protective ambition, as I was communicating through a solitary private email from 4,000 miles away! And then Glees tripped himself up over the absurd ‘double agent’ business. It appears that the professor has not bothered to read my research carefully, and does not understand the distinctions between penetration agents, traitors, and double agents. I have thus ignored his lectures to me. Some woodsman; some lumber.

It is all rather sad. I do not understand why an academic of Glees’s reputation would want to engage in such petty practices, and try to distort my researches in such a non-collegial manner. (I have indeed helped him on several matters when he has sought my advice.) Yet, in a way, I do understand. I have seen enough of the goings-on at the University of Buckingham to be able to write a David Lodge-type novel about the pettiness and jealousies of provincial English university life. I have described some of those exploits on coldspur already: I shall refrain from writing up the whole absurd business until another time (I would hardly want to lower myself precipitately to that level, would I?), as I presently have more important fish to fry. When I have run out of other research matters, I may return to the shenanigans at the University of Buckingham.

Yes, I admit this is all rather petty on my part, too. It was just the Soldiers of Oxfordshire museum, not an invitation on In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg. But, if ‘one of my biggest admirers’ can get things so wrong, what is he doing the rest of the time? I wanted to set the record straight. Besides, it is quite fun to bring the Prof down a peg or two.

And then, by one of those extraordinary coincidences that crop up more frequently than they should, I read these words in the July Literary Review, by the biographer Frances Wilson:

. . . . most memoirs, if not loaded guns, are written for the purpose of retribution and revenge. This is by no means a criticism: retribution and revenge are strong reasons for writing a book. You want to put the record straight, to tell your side of things, to correct a wrong. Even the mildest-mannered memoirs have reprisal at their hearts.

Thank you, Ms. Wilson.

Operation PARAVANE

I have not yet received anything substantial on the piece compiled by Nigel Austin and me, The Airmen Who Died Twice. That does not surprise me much, as the PARAVANE operation is a little-known episode, a side road to the main WW2 excursion. Yet the posting of my bulletin on June 3 placed an important marker for the story, and immediately made a synopsis available worldwide as a reference point for anyone who might be trawling on the Web for information on PARAVANE.

I shall not reveal here the astonishing denouement of this extraordinary series of incidents, but one aspect of the exploit merits some attention. And that is the uncharacteristically cooperative behaviour of the Soviet Air Force. It was only at the end of August 1944 that RAF Bomber Command concluded that an attempt to use the new ‘Tallboy’ bomb in a direct raid from Scotland was not feasible because of fuel capacity, and considered using a base in the northern Soviet Union, near Murmansk, as an intermediate destination after the raid at Alta Fjord. That Air Marshall Harris could take for granted at this late stage that the Soviets would agree to such an initiative indicates that negotiations for such must have been in place for some time, as the Russians were extremely wary of allowing foreigners on Soviet soil. Any such move would have had to be approved by Stalin, and recent events at Poltava and Warsaw had indicated that the Soviet military command was keen to obstruct any such cooperative operations.

For the relationships between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union were indeed at their lowest ebb at this time. (See https://coldspur.com/war-in-1944-howards-folly ) Stalin, having encouraged the Warsaw Uprising over the radio, then refused permission for air support operations by the western Allies to the Poles to be launched from Soviet territory, the missions having to be directed from the UK, and from Brindisi in Italy, and back. It was at the end of August, when the PARAVANE operation was being planned, that Churchill pleaded with Stalin to allow Soviet airfields to be used to support the Warsaw rebels, but Stalin was obdurate, and Roosevelt would not join Churchill in his appeal. Soviet forces waited the other side of the Vistula river until the uprising was quashed by the Nazis, at enormous loss of life.

Moreover, a precedent for the use of Soviet airbases had recently occurred in Operation FRANTIC, where the Soviets granted rights to the USA Air Force to conduct bombing-raids on German territory between June and September 1944. I have recently read books by Glenn Infield (The Poltava Affair) and Sergii Plokhy (Forgotten Bastards of the Eastern Front) which tell the sad story of how the Americans were misused by the Soviets, especially when, on June 21, Soviet air defences failed to prevent a highly destructive raid at Poltava by German airplanes, all of which escaped intact. By then, in any case, with the Soviet land forces moving close to Germany, the value of the base had sharply diminished.

Thus when Bomber Command had a further change of plan, and was apparently able to decide, on September 4, without further consultations with the Soviet Air Force, that the aircraft of the PARAVANE operation would better land in Soviet territory, and preferably at an airfield further away from German airbases than Murmansk, and thus less likely to be strafed, it was extraordinary (in my opinion) how smoothly and quickly the negotiations continued. In a matter of days, Yagodnik had been identified as suitable, and made available, but a week later, an even bolder version was aired. The new plan – to have the squadrons fly directly to the Archangel area, and rest and refuel, before launching the attack on the Tirpitz, and then return to that airbase – was likewise immediately approved by the Soviets. I believe that the groundwork must have been prepared some time before, and that the Number 30 Military Mission to Moscow (Air Section), which had been boosted in the summer of 1944, must have presented a case for the usage of airfields well before early September.

The fact is that Stalin was extremely wary of any Soviet citizens’ being exposed to foreign influences, and the NKGB and SMERSH were trained to consider all such persons on their soil as spies. While the cause of protecting convoys to Murmansk was no doubt genuine, it was becoming less important by this stage of the war, and Stalin must have had ulterior motives (such as the acquisition of the latest military technology) in granting such rights to the British squadrons. The Foreign Office, in its misguided belief that ‘cooperation’ with the Soviet Union would lead to harmonious relationships when the war ended (an echo of the attitude taken by President Roosevelt and his sidekick Harry Hopkins), was quick to see this offer as a sign of Soviet goodwill – a ridiculous mistake. I have started to investigate the 30 Mission records for further clues, as the RAF records are disappointingly vague.

I was able to make email contact with Professor Plokhy, and asked him whether he had any insights into the complementary PARAVANE operation. Unfortunately he did not, but he directed me to someone who, he thought, would be able to help, a Liudmila Novikova, in St. Petersburg, an expert (so Plokhy said) on British units in the Soviet Union. I was unable to gain any response from her; perhaps I went straight into her spam folder, or maybe she has uprooted because of the recent turmoil. Does anyone know her?

Lastly, one correspondent, having read the PARAVANE piece, drew my attention to another mysterious aircraft accident of 1944, in Newquay, Cornwall, the details of which have ever since lain in obscurity. The informant was Mark Cimperman, the son of the FBI’s wartime representative in London during the war, Frank Cimperman (who appears frequently in Guy Liddell’s Diaries). I tracked down the event at http://wartimeheritage.com/storyarchive2/storymysteryflight.htm , and was astonished at the eerie characteristics that patterned those concerning the crash at Nesbyen a few months later. Mark told me that the researcher for the story, David Fowkes, had written to the Cimpermans, believing that Frank might have known something about the accident. Sadly, Cimperman had died of cancer in 1968 at the age of sixty.

The Coldspur Archive

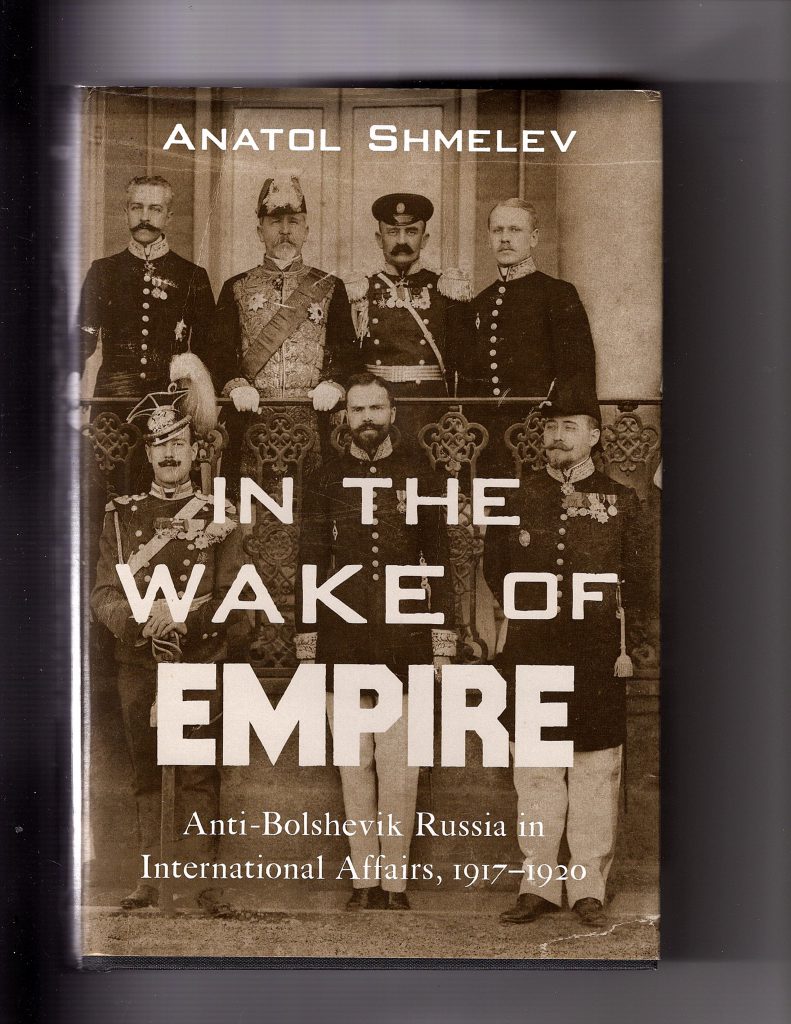

As part of my project to preserve the coldspur archive, I made contact in early May with the Hoover Institution at Stanford University in Palo Alto, and eventually received a very courteous response from Dr. Anatol Shmelev, a research fellow and Robert Conquest curator of the Russia and Eurasia Collection. Over email, he had advised me to seek out a smaller university as a destination for my book collection, as he believed there would be too many overlaps with what the Institution held for Hoover to be an appropriate donee. I have thus since attempted to contact the Librarians at a couple of other universities, but have received no response to my approaches. I arranged, however, to have a meeting with Dr. Shmelev, during my visit to the area, and it turned out that he and his family live a few minutes away from our son in Los Altos.

On June 11 I thus enjoyed a very pleasant lunch with Anatol and his wife, Julia, who was born in St. Petersburg, and who acted as research assistant to Robert Conquest in the latter years of his life. Robert Conquest was someone I admired greatly (another significant writer whose hand I hoped to shake, but he was too infirm by the time I wrote to him just before his death): his Great Terror and Harvest of Sorrow made a deep impression on me, as they must have done on many students of Russian history. He was also a close friend of Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin, two more of my enthusiasms, although their private correspondence betrays opinions that are highly inappropriate in today’s sensitive times. It was a privilege, nevertheless, to meet two academics who had worked so closely with Conquest.

Anatol gave me some further tips about finding a home for my books, suggesting that I seek the support of members of the history faculties at such universities rather than the librarians/archivists themselves. We had a lively and fascinating discussion about many topics of Russian literature and history, and intelligence matters, as well as regretting the obvious fact that many book collections are simply pulped when the cream has been skimmed off them. I would hate to see that happen to mine, but that is presumably what everyone says. I did also immediately order Shmelev’s recent book, on Russia’s path immediately after the Revolution, In the Wake of Empire. I expected it to be a fascinating companion to Antony Beevor’s volume Russia, Revolution, and Civil War, 1917-1921, which has received excellent reviews in the British press already, but will not be available in the USA until September.

Indeed, Shmelev’s book was absorbing – quite brilliant. The author had access to a large trove of correspondence between the exiled Russian diplomats and their military counterparts, such as Admiral Kolchak and General Denikin, and has exploited them to show the futility of a fractured opposition to the Bolsheviks. I had not understood all the dimensions of the conflict, what with outlying nations of the old Russia straining for independence, the struggles between those wanting to restore the old land-owning aristocracy, or even an emperor, and those who accepted that land reforms and a more democratic constitution were absolutely essential in order to give credibility and authority to any future regime. The challenge for pluralist political entities to counter effectively a determined and single-minded dictatorial force was brought home to me by the fact that not only did the Whites disagree among themselves, the Allies all had diverse interests, as did the borderland national territories of old Imperial Russia, and, even within one nation’s administration, the British War Office disagreed with the Foreign Office on policy, and within the Foreign Office itself, factions had sharply divided views on what the representation and constitution of the future Russian governing body should be. Eventually, Communist Might meant Right. Shmelev’s judgments are sure – authoritative without being dogmatic – and shed much light on the tortured dynamics of the civil war. I shall defer a full discussion until later, when I have read Beevor’s book.

Incidentally, Dr. Shmelev also wrote a book on Russian émigrés, titled Tracking a Diaspora:

Émigrés from Russia and Eastern Europe in the Repositories, and I believe that the story of Serge Leontiev (aka George Graham) and his forbears, friends, and associates will be of interest to him.

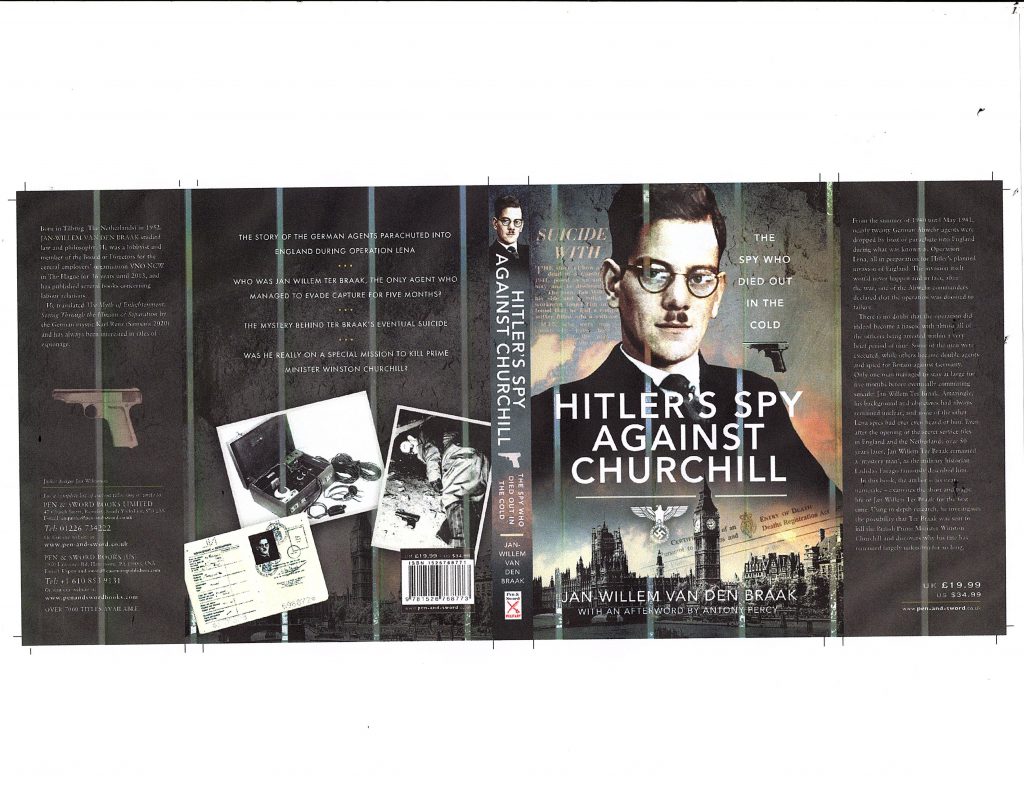

‘Hitler’s Spy Against Churchill’

This book, by Jan-Willem van den Braak, is now available – both in the UK and the USA – and I encourage coldspur readers to acquire it. It constitutes a very valuable addition to the chronicle of the Abwehr spies sent to the United Kingdom in the autumn of 1940, its subject, ter Braak, managing mysteriously to remain undetected for several months before committing suicide, or so the story goes. (I did supply an Afterword for the book, which I would not have done had I not thought that the author had carried out a stellar piece of research. In that piece I voice an alternative theory about the spy’s demise.) I have not seen any reviews of the work yet, but I know these things take time.

An Update on Paul Dukes

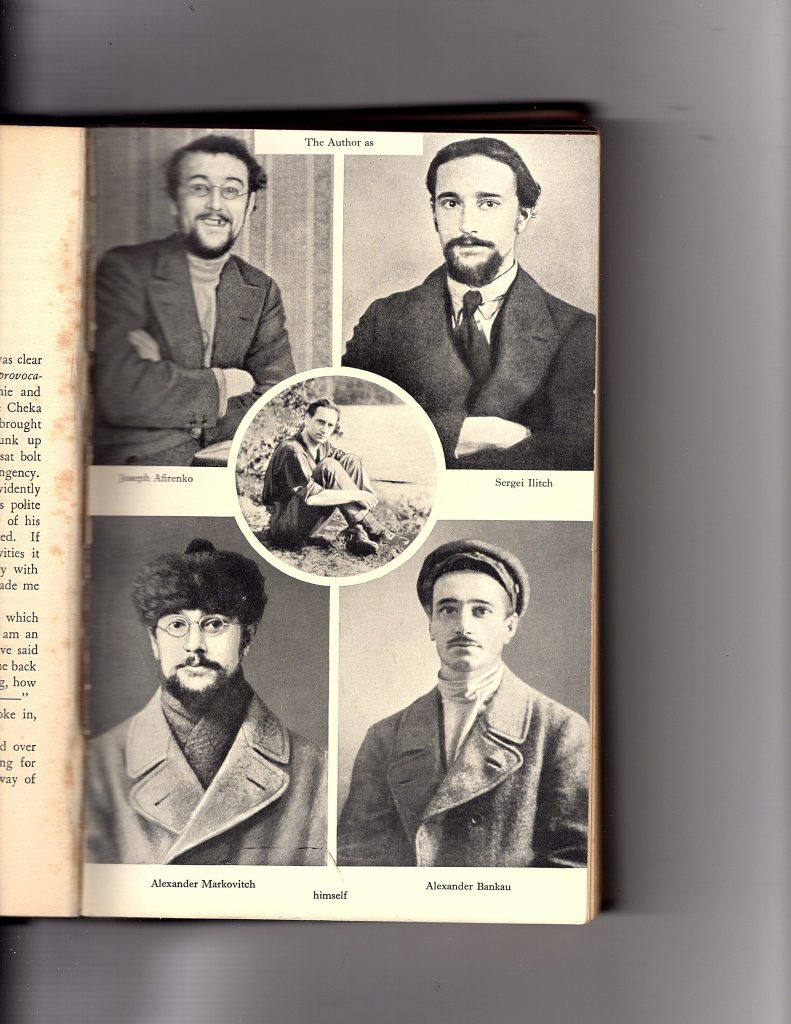

In my piece on George Graham, I had expressed some puzzlement over the behaviour of Paul Dukes in the 1930s, finding the official biographical records somewhat wanting. And then, while I was researching the Volkov business, I discovered that Keith Jeffery, in his Postscript for the new paperback edition of his history of MI6, had inserted some new analysis of Dukes’s activity at this time.

The essence of the account is that MI6 did attempt to exploit Dukes’s plans, in May 1934, to take a predominantly Russian troupe of ballet-dancers to Eastern Europe and to the Soviet Union. When Admiral Sinclair, the head of MI6, heard about this, he sent Harold Gibson to Vienna to discuss how Dukes might help develop intelligence sources in the U.S.S.R., since MI6’s sources there were practically non-existent (if, indeed, there were any at all). Yet the project soon foundered. Illness and disappointing box-office returns meant that the company never reached further than Italy, and, twelve months later, Dukes was in such bad favour that Sinclair told Monty Chidson, head of station in Bucharest (who asserted that Dukes was involved in arms dealing with Sofia) that he was to have nothing to do with Dukes.

MI6 belatedly realized that Dukes was a faded product: he had mixed too closely with White Russian emigrants (very true), and he would now constitute quite a security risk. Valentine Vivian issued him some advice before Dukes left London in August 1934, warning him to minimize his risks, but then minuted that the characteristics that had helped him become a valuable agent in 1919 would work against him now. Later, MI5 apparently took an interest in him, for Vivian posted another memorandum in February 1940, where he was forced to concede that Dukes’s finances were considered to be ‘catastrophic’, and that his sense of balance was considered by some to be ‘deficient’. Perhaps that was intelligence-speak that he was losing his marbles. Vivian went on to write: “His temperament is essentially artistic, and while his knowledge of things and people is encyclopaedic, his tastes rather run towards the eccentric and he would not be acceptable to those who look for a uniform service mentality”. In other words, no bohemians wanted.

The evidence I collected for my piece suggests that Dukes was trying to rehabilitate himself for a foray into the Soviet Union after these setbacks (John Stonehouse-like faked death, pro-Soviet writings), but it is not clear why anyone would have been sponsoring his intelligence-gathering aspirations. And, if he did now have an official assessment as being a loony and a spendthrift, why would anyone have listened to him when he came to recommend Serge Leontiev/George Graham as cipher-clerk for George’s Hill’s mission to Moscow? Sinclair was dead by then, but what was Valentine Vivian thinking? It is all very odd.

And then I alighted on another odd reference to Dukes while checking something in Michael Smith’s Station X (about Bletchley Park). While discussing the imaginary British spy Boniface (who was used as an alibi for Enigma decryption sources) Smith quotes R. V. Jones, who reported something he had been told:

Gilbert Frankau, the novelist, who held a wartime post in intelligence, told me that he had deduced that the agent who could so effectively get into German headquarters must be Sir Paul Dukes, the legendary agent who had penetrated the Red Army so successfully after the Russian Revolution.

This statement does not appear in Most Secret War, so probably comes from an article that Jones supplied to the journal Intelligence and National Security in 1994. I note that appalling use of ‘legendary’ again, presumably not meaning that Dukes was a mythical being, but that many tales were told about his exploits, and that a good proportion of them were tall. The irony here was that, instead of Dukes being able to infiltrate the Nazi command, he had, through his recommendation of George Graham, unwittingly enabled the Soviets to break into the supposedly clandestine exchanges of MI6 and the Foreign Office.

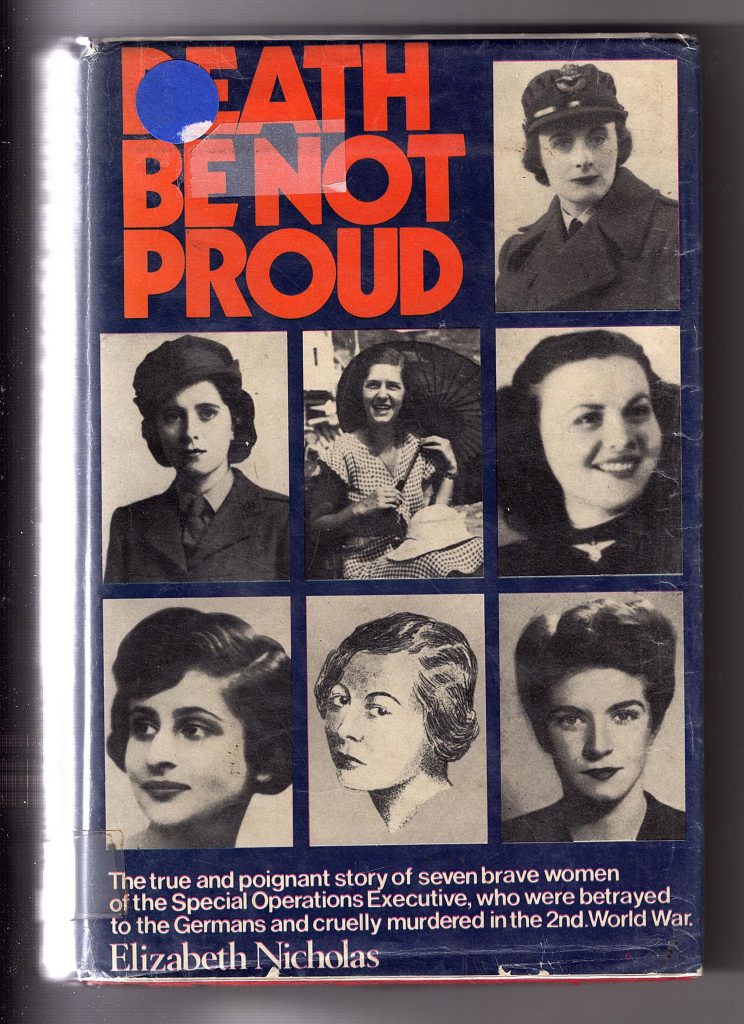

The PROSPER Disaster

As I was starting to write this piece, the thickness of the fog that surrounds the relationship between the Allies in the UK and French resistance during World War II was brought home to me. I was reading a review of Graham Robb’s France: An Adventure History in the Wall Street Journal when I encountered the following sentence: “Rather, he notes the Allies’ fatally tepid support of the Resistance and turns a sad gaze on the reprisals that tainted every corner of the mountains with ‘some ineradicable act of cruelty’.” The impression – and I suppose that it is Robb’s, but one endorsed by the reviewer – is that a potentially decisive opportunity was lost by the Allied armies (or SOE and OSS) in not supporting an extensive secret army that was simply waiting in the wings for a chance to make vigorous assaults on the German occupiers. Yet the story in fact played out on the following lines: initial experimental attempts to infiltrate agents; some vastly exaggerated claims about the size of secret armies; struggles to get the RAF to ship arms and equipment; betrayals to the Germans; stepped up shipments with the false promise of an early Allied assault; disillusionment and multiple arrests; a recalibration in the months before the Normandy landings; some vicious attacks and reprisals by the Gestapo and the Wehrmacht; a few spectacular successes in support of the Allied armies. And then de Gaulle attacked anyone who had co-operated with the Allies and tried to perpetuate the myth that the French exclusively had liberated themselves. Thus the representation of Allied strategy as being a failure to support the Resistance is both a distortion and an oversimplification of what actually happened.

I have still to post the concluding segment to my analysis of the betrayal of the PROSPER circuit. This will involve a close inspection of the minutes of the War Cabinet and Chiefs of Staff in June and July of 1943, as well as a closer study of the Bodington and Déricourt files. I do not intend to reproduce simply what has been published before, but I believe the current accounts are deficient in different ways. Robert Marshall’s All The King’s Men is on the money, but it is a little too hectic, and relies too much on oral testimony that cannot be verified. M. R. D. Foot’s SOE in France is packed with detail, but is fatally flawed by the constraints laid upon him and is still rooted in a 1960s perspective, which means that he evades the strategic issues. His Chapter XIV, Strategic Balance Sheet, completely ignores the premature attempts in 1943 to arm resistance forces with promises of an imminent arrival of Allied forces. (Moreover, the text of that summarization remained unchanged in 2004, nearly forty years after it first appeared – an extraordinary gesture of disdain towards all who had written about SOE in the interim.) Francis Suttill’s Prosper is driven by a need to track down all the details of his father’s circuit, but it is error-strewn, and he ignores the evidence in front of him in his eagerness to discount any conspiracy behind his father’s demise. Patrick Marnham’s War in the Shadows is very sound overall, but choppy: Marnham misrepresents some of the key events of 1942 and 1943, in my opinion, and weakens his case by introducing the Jean Moulin side-plot.

I therefore judge that my account of the saga needs a tidy conclusion, and I suspect that the evidence from the archives will embellish the assertion confidently made by Marnham and Marshall that the French Resistance was willfully misled as to the imminence of an Allied re-entry to the French mainland in the summer of 1943. I believe that my hypothesis that Suttill made two trips to England in May and June 1943 (see https://coldspur.com/feints-and-deception-two-more-months-in-1943/) contributes to a clearer picture of his motivations and disappointments. My next report on this saga will appear at the end of August.

It is a continuing research question of mine: what strategy was SOE executing when it tried to ship weapons to sometimes unidentifiable teams of resistance members in 1942 and 1943? According to their own records, at least 50% of arms were lost or fell into the hands of the Nazis. The submissions of SOE to the Chiefs of Staff about the potential of ‘secret armies’ showed that they had been completely misled by the claims of some of their agents. Furthermore, they showed a dismal lack of understanding of what would be required to store and maintain weaponry in good condition, and to train guerrilla forces in how to deploy it. Supplemented by some further reading of memoirs and biographies, such as in my study of Colin Gubbins last month, and the new biography of Virginia Hall (see below), I plan to provide soon a more detailed exposition of the controversial events of the spring and summer of 1943. Moreover, I have ordered a copy of Halik Kochanski’s Resistance: The Underground War in Europe, 1939-1945, in the hope that its 932 pages may reveal some fresh insights on the events of 1943 that the primary histories (including Olivier Wieworka’s recent The Resistance in Western Europe: 1940-1945) have in my opinion severely mismanaged.

P.S. As I was putting the finishing touches to this piece, I came across the following sentences in The Quiet Americans: Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War (2020), by Scott Anderson (p 294):

In most Nazi-occupied countries of Western Europe, whatever partisan formations existed only became a factor on the battlefield when the arrival of Allied armies was imminent. Nowhere was this truer than with that most vaunted of partisan forces, the French Resistance. Despite the popular notion of a France united in undermining the rule of their German conquerors, in reality, the Resistance was little more than an intermittent and low-grade pest to the Nazis until their numbers suddenly swelled in June 1944.

Precisely! This was the colossal mess that Gubbins presided over, and which M. R. D. Foot, either through lack of imagination, or by intimidation, failed to reveal in SOE in France.

2022 Reading

As I peruse the Times Literary Supplement, the London Review of Books, and the New York Review of Books, I am constantly reminded of the earnest volumes that are issued by the University Presses. Should I be reading The Kingdom of Rye: A Brief History of Russian Food, or Legacies of the Drunken Master: Politics of the Body in Hong Kong Fu Comedy Films, or Harry Potter and the Other: Race, Justice and Difference in the Wizarding World (all titles advertised in the June 17 issue of the TLS)? Probably not: life is too short. And sometimes I can’t help feeling that my speculative second book, The Unauthorized but Authoritative History of MI5 (affectionately known as TUBA), might have a better chance of commercial success than some of these rather dire works. And then the reviewers! Most of them are able to boast what their last published book is, but occasionally one is signalled by such phrases as ‘she is currently working on a collection of essays’. It all sounds rather drear, like those American waitpersons who approach you to ask whether you have ‘finished working on your meal’ so that they might take the plate away. But my work is fun (mostly). And I don’t have to consider the dreadful chore of dealing with publishers and editors: I just post my current essay on coldspur, and move on to the next one.

On reviewing my spreadsheet of Books Read for the year so far, I note that it consists mainly of volumes related to my researches, of which more later. Yet I do try to relax with lighter works in between. I started reading the fiction of Elizabeth Taylor: I was not very impressed with the short stories in You’ll Enjoy it When You Get There or the somewhat clumsy A Game of Hide and Seek, but enjoyed Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont, and the well-drawn A View of the Harbour. And I am a keen reader of memoirs and biographies, The new edition of Konstantin Paustovsky’s Story of a Life, in a fluid and sparkling translation by Douglas Smith, gained some excellent reviews: I had let this work pass me by when it came out many decades ago. The reviews were merited: it is a beautifully written memoir of a vanished world, Paustovsky showing an ability to recall smells, sights, sounds, persons, conversations and situations without becoming over-lyrical or extravagant. As a picture of life before the revolution in eastern Europe (mainly in Ukraine), it is probably unmatched. For the short time about which he writes after the revolution, as in the escape from Odessa (Odesa), it lacks the irony and incisiveness of Teffi (Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya), whose Memories I read last year, but gives a very insightful picture of the rapid disillusionment that followed the drama and expectations of 1917. Paustovsky was a survivor in Stalin’s prison-camp: when many of his contemporaries were oppressed or even murdered, he managed to outlive the dictator (1892-1968), so must have had to compromise to be allowed to continue writing and avoid persecution.

Spy Fiction

I have also dabbled in a genre that is called ‘spy fiction’, and has received much media attention of late. I read Gard Sveen’s The Last Pilgrim because it is a book about the Norwegian resistance, and includes in its cast a real person, Kai Holst, who was of interest to me because of his strange death in 1945 soon after the Swedes received secret cipher material from the Abwehr. Holst was a Norwegian resistance fighter, resident in Stockholm, who died in mysterious circumstances in June 1945. Some writers have suggested that he was murdered because he knew too much about Operation Claw, a venture whereby the Americans and the Swedes gained vital intelligence material on Soviet ciphers from the Germans, something that would have embarrassed the Swedish government because of its claimed neutrality. The file at Kew, FO 371/48073 (https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C2805368) was supposed to be released under the 75-year rule in 2020, but is still marked as being retained by the Foreign Office. As for the book, it won several awards, but I found it rather laborious and repetitive, and the mixing of real and fictitious persons and events irritating.

And then there was Mick Herron. I read a few reviews of his Slow Horses, and decided that I ought to give him a try, and have since also read Dead Lions, Real Tigers, and Spook Street, volumes in his series concerning Slough House, an imagined dumping-ground for MI5 officers and personnel who committed some career-breaking faux pas during the cause of duty, and have been exiled to this dumpy office in London. The books are hilarious. Slough House is managed by a very sharp but foul-mannered slob, Jackson Lamb, who makes Horace Rumpole look like Jacob Rees-Mogg. Herron captures the essence of his characters with wickedly humorous speech patterns and dialogue, and his prose has a Wodehousian creativity and zaniness about it. I found the larger-scale plots a bit absurd (for instance, could there really have been a colony of communist sleeper agents of influence in the British countryside in the 1990s?), but they were not damaging enough to spoil the rollicking fun. I see that a TV series has been made of Slow Horses: I have not seen it yet, but Aunt Edna would probably not approve of the language (although these days, of course, Aunt Edna probably swears like a trooper).

One important point occurred to me as I read Herron’s books. The plots of spy fiction these days have to be dependent upon, and coherent with, the technology of its time, yet that technology is constantly changing. I vaguely recall reading a thriller by Charles Cummings a decade or so ago, sprinkled with Nokia mobile phones, VCRs, payphones, and SCART connections, all of which immediately date it, but also drove the plot. (I am constantly amused that my 2011 edition of Chambers Dictionary includes an entry for ActiveX.) Between the time an author starts writing his text and the date of the book’s publication, much of the technology must change radically. Herron sensibly does not identify many products so specifically, but such features as Google, (which was there in Cummings’ world of 2010), YouTube, and the dark web are prominent in his plot, and Twitter appears in Spook Street. Yet there must still be risks: I was astonished how Herron allows so many mobile phone-calls between different members of MI5 to be carried on in unencrypted mode. Was nobody listening? And how come no one seems to use their phone-camera? Pinpointing current technologies, and lavishly exploiting them, give verisimilitude – but also raise questions of accuracy and authenticity. And future novels involving flashbacks will have to be very precise about the technical context of the time. (‘Snapchat was not around in 2010!’) That was not a problem faced by Arthur Conan Doyle, or Eric Ambler – or even John le Carré.

I also picked up, on an impulse, An Unlikely Spy by Rebecca Starford, who is described as ‘the publishing director and cofounder of Kill Your Darlings, and, more alarmingly, as having ‘a PhD in creating writing from the University of Queensland’. I am not sure how Fyodor Dostoyevsky or Charles Dickens managed to be successful without some degree in Creative Writing, but then I am an old fuddy-duddy. The plot sounded intriguing, however: “In 1939, with an Oxford degree in hand and war looming, Evelyn finds herself recruited into an elite MI5 counterintelligence unit” (as opposed to those non-elite Slough House-type backwaters, I suppose).

I soon discovered that the book was originally published in Australia with the title The Imitator, so I suppose the reworked version was superior, as I doubt whether my eye would have been caught by the rather drab earlier headliner. And it turned out to be well-written, although it did carry that annoying post-modern trick of jumping around in chronology all the time, rather than approaching events in an orderly serial manner. (Is that what your Doctors of Creative Writing tell you to do? Do you get extra credits for displaying this habit?) I thus quickly entered the spirit of the plot, and started to acclimatize myself to the carefully placed markers of London in 1940, and the offices of MI5 at Wormwood Scrubs, as Evelyn Varley is recruited to help out with deciphering work.

A flicker of recognition then slowly dawned upon me, however. Evelyn Varley was a thinly-veiled representation of Joan Miller, author of One Woman’s War; Bennett White, her boss, was clearly the MI5 officer Maxwell Knight; Nina Ivanov was undoubtedly Anna Wolkoff. The whole story was a re-play of the Tyler Kent story, where the American cipher clerk stole copies of documents from the US Embassy in order to have them passed to the Germans. It reminded me of another clumsy effort at faction, Kate Atkinson’s Transcription, about which I wrote a few years ago. I really do not see the point of these ‘novels’: the authors take some characters from history, and then massage events and names to make it appear as if they have created a convincing psychological study. I quickly lost interest.

Ms. Starford admits her ruse in her ‘Reading Group Guide’, where she is also vain enough to offer some ‘Questions for Discussion’. She proudly describes her research activities (including a generous acknowledgment of Christopher Andrew’s history of MI5), and how she decided to ‘create’ Evelyn from the scraps of Miller’s memoir, and even manages to bring in ‘Brexit, the rise of far-right populism in Australia and abroad, and the ascent of Trump’ as a relevant backdrop to her writing, and even claiming that the fear and anxiety that those phenomena provoked found its way into her characters. What nonsense! And how pretentious to offer a review of her own book as collateral!

Moreover, she also offers an ‘Author’s Note’ to explain her deceptions, writing that she ‘tried to remain as faithful as possible to the history of these events’, but then declares that she had to make some ‘adjustments’ in order to provide a convincing story. She then lists a catalogue of her chronological changes to events that explicitly undermines the integrity of her story. All utterly unnecessary and distracting. In sum, I do not know why such works are attempted or encouraged. Either perform some innovative research to uncover the true facts about events, or use your imagination to create a convincing artificial world. These factional books are not for me.

The only interesting item I derived from the book is the statement from Stanford that Joan Miller ‘died in a mysterious car crash in the 1980s not long after she had published a memoir about her time in MI5’. Readers of Misdefending the Realm will recall my analysis of why MI5 tried to get her book banned, but this was the first I had heard about a suspicious car-crash. Sounds like an echo of the demise of Tomás Harris, or the accident involving George Graham’s son.

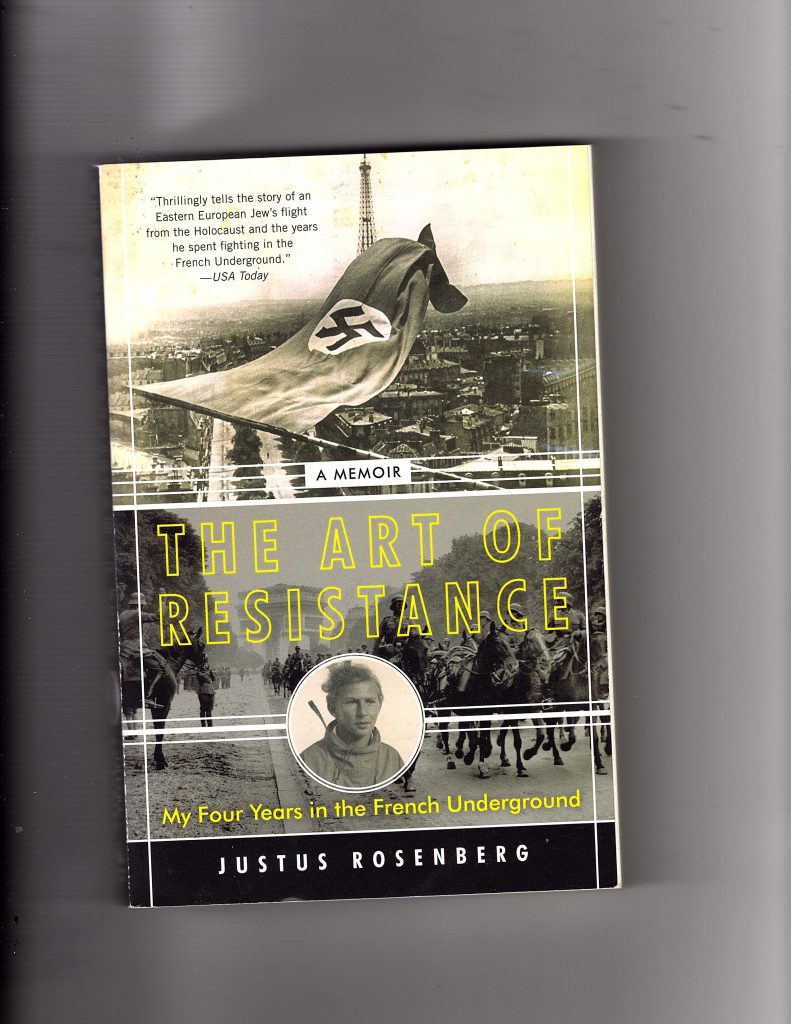

The Art of Resistance

I have also read some remarkable books peripheral to my main course of research. Justus Rosenberg published his memoir The Art of Resistance in 2020, and in an epilogue wrote:

I will not write here of my extensive travels in the Soviet Union and its satellites during the Cold War, in Cuba just after the revolution, in the People’s Republic of China, of my visit with the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, or of the interesting material I found about me in my FBI file under the Freedom of Information Act. Nor will I explore my years of teaching at Swarthmore, the New School for Social Research, and Bard College. I hope to deal with all these things in future memoirs.

The main problem with this plan was that Rosenberg was ninety-seven years old when he completed his memoir, and died in September 2021 at the age of 100. If his follow-up had been as action-packed and insightful as The Art of Resistance, it would have constituted another extraordinary work. Rosenberg’ s life was of interest to me mainly because of his experiences with the French Resistance in World War II. Born in Danzig in a secular Jewish family, Rosenberg managed to conceal his ‘race’ from the Germans when he escaped to France, where he eventually linked up with the American Varian Fry. After the latter had to return to the United States in some disgrace in 1941, Rosenberg worked in various roles for the French Resistance, achieved a miraculous escape from a prison hospital by simulating the symptoms of peritonitis (although I wondered whether he had in fact swallowed those special SOE pills that triggered the symptoms of typhoid), and ended the war by joining the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. He then gained a visa to the United States, where he enjoyed a distinguished career as a professor of literature.

I found Rosenberg an exceptionally level-headed and unmelodramatic chronicler, as well as a brave man. He was clearly a very smart and practical thinker, and was not caught up with the rhetoric of any ideology or religion. He has some illuminating things to say about Varian Fry (whose contribution to the escape of many European intellectuals has been over-romanticized), and scatters his memoir with many incisive vignettes and anecdotes. On two elements, I question him. He is one of those many who errantly contrast Soviet communism and ‘American capitalism’ as rival ideologies, when (as I pointed out in Misdefending the Realm) that it is a false contrast, since capitalism is neither a totalitarian ideology nor a political system, but an approach to the creation of wealth, and the comparison should be made between totalitarian communism and various forms of constitutional, pluralist democracy, whether presidential or parliamentary.

And I found him very loose on the practices of armed French resistance. He lists various categories: ‘partisans’, ‘freedom fighters’, ‘maquisards’, ‘guerrillas’, ‘underground armies’, ‘resistance fighters’, ‘saboteurs’, without explaining what characterized each. He recognizes the differences required in occasional guerrilla raids and the full engagement of an occupying army, and describes the rigorous training that was required to bring a raggle-taggle band up to proper military strength. Yet he also relates how ‘the French Underground Army’, described as ‘Resistance fighters waiting to join the Allied forces’ suffered a catastrophic defeat in the Vercors mountains, when a large section was annihilated by a glider-led force of 12,000 SS paratroopers. This vexed issue of the remote management of insurrectionist forces is a perennial interest of mine, as I believe that proper justice has not been performed to the topic in the writings about SOE and OSS in France. A book titled The Art of Resistance disappoints when it covers authoritatively such matters as the practices of secrecy, clandestine communications, and the isolation of networks, but does not explore what the implications of providing weapons to ‘secret armies’ were, and how such tasks should have been executed.

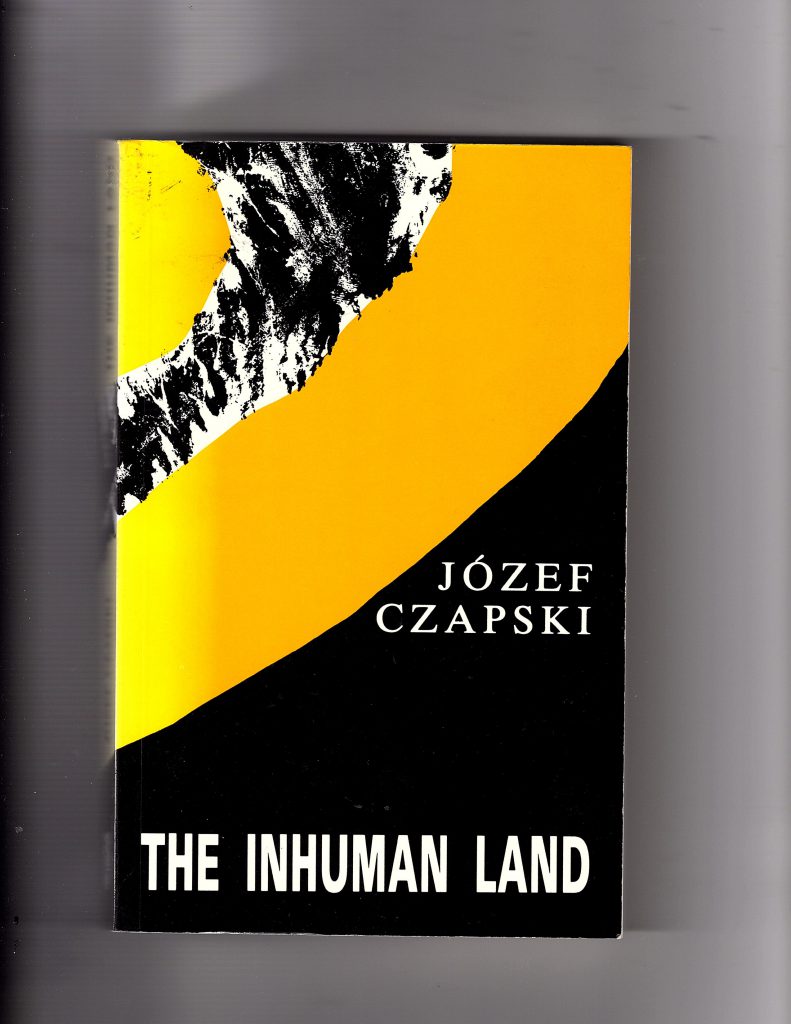

The Inhuman Land

Another valuable work was Jozef Czapski’s The Inhuman Land. I found that I had a copy of the 1951 edition on my bookshelf – a volume that I had never got round to reading. It has recently been resuscitated by New York Review Books, with an introduction by Timothy Snyder, but my edition (according to the price on abebooks) is now something of a rarity. Czapski’s book is vital, since, with the post-war knowledge that the NKVD had in the spring of 1940 slaughtered twenty-thousand Polish officers (of whom 4,421 were executed in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk), the author, who had managed to avoid the killings, described his attempts to discover what had happened as he worked as propaganda minister for General Anders’ emerging Polish Army, gathered in the Soviet Union.

The evil of the NKVD’s massacre was compounded when the Soviet Union tried to transfer the blame to the Nazis, who had themselves uncovered the graves in April 1943. When the Polish government-in-exile requested that the International Red Cross investigate the incident, Stalin broke off relations with the Poles. What made the whole business even more sordid was the fact that Churchill and Roosevelt, while privately acknowledging the Soviet guilt, did not dare challenge Stalin on the matter, fearful that they might lose his support, and that he might even abandon them in some fresh deal with the Germans. It was an abject display of appeasement.

What is remarkable about Czapski’s work is the fact that he was essentially allowed a free hand, from inside the Soviet Union, to investigate what had happened to so many of Poland’s elite force, who appeared to have disappeared from the face of the earth. He maintained a file of all missing officers, and was allowed even to make inquiries of the NKVD, when a careless and grudging admission that ‘mistakes were made’ led him first to conclude the awful truth. The other side of this effort was that he also learned at first hand a lot about the hideous cruelty of Communism from all manner of oppressed tribal people, forcibly migrated national groups, common citizens who had been split apart from lost family members, or dispossessed because of dekulakization, or who had simply witnessed the barbaric cruelty of the Soviet organs. And that he was able to commit it all to memory, or write and conceal encrypted notes, which allowed him to tell the whole grisly story after the war. The Inhuman Land was first published in French in 1949.

Amazingly, Czapski, born in 1896, died as late as 1993. I regret coming round to his work so late in life. One of the many whose hand I should simply like to have shaken before they died. Like Gregor van Rezzori (1914-1998), or Robert Conquest (1917-2015), or the recently encountered Justus Rosenberg, all long-lived witnesses to such chaotic times, who wrote about them so poignantly.

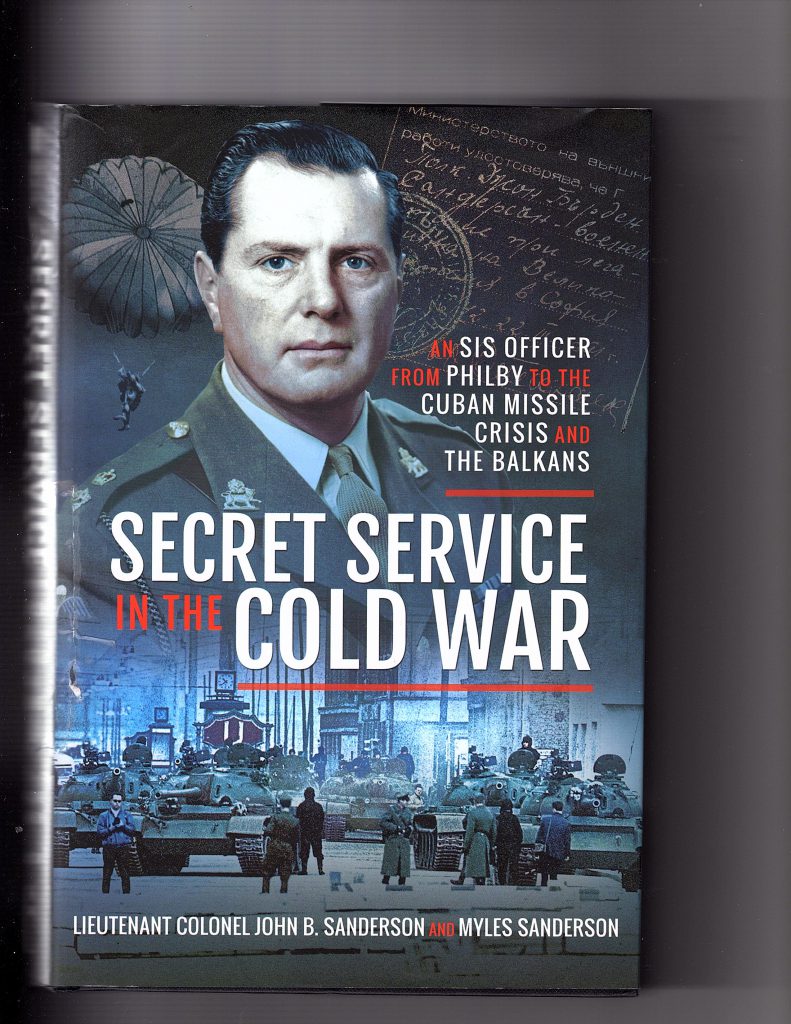

Secret Service in the Cold War

Readers may recall that I noted, in my recent study of the Volkov affair, the existence of the interpreter Sudakov at the Ankara consulate in 1945. “The name of ‘Sudakov’ is an intriguing one. In An SIS Officer in the Balkans (2020), John B. Sanderson and Myles Sanderson write: “The First Secretary of the Soviet Embassy in Ankara was a Brigadier General Sudin, in charge of “illegal residents” (spies), within Turkey, some of whom were Bulgarians. Penkovsky was a friend of Sudakov’s (Sudin’s alias) and would have passed over to his SIS handlers useful intelligence on Bulgarian espionage in Turkey, picked up in conversation with his high-ranking friend.”

From the sources given by Myles Sanderson, it did not appear that any fresh light would be shed on the character of Sudakov, but I acquired the book, of which the full title is Secret Service in the Cold War: An SIS Officer in the Balkans. It is a compilation by the subject’s son, using unpublished memoirs of his father, and supplemented by some lengthy description of Cold War politics. It is an unusual, and overall praiseworthy study, as it tries to provide a thorough political background to all the espionage and counter-intelligence activities going on throughout John B. Sanderson’ s career. Yet, as time marches on, the contribution that Sanderson Senior made to counter-intelligence activity becomes very thin and strained, and thus the focus of the book likewise becomes very fuzzy.

The good points: as a general compendium of significant historical events, and the intelligence activity behind them, the book is probably unmatched, as many of the reviews posted on amazon confirm. Nearly all general histories of the winding-down of WWII, and the onset of the Cold War, do not do justice to the contribution made by Stalin’s agents to the ability of the Soviet Union to manipulate and outwit the democracies, especially Great Britain and the United States. Studies of intelligence and espionage are normally so wound up in the intricacies of spycraft and treachery that they do not pay enough attention to the political results of such activities. The second major quality of the book is the insight that it gives on the exploits of John B. Sanderson in his early career, culminating in a valiant role at the battle of Sangshak in Burma in 1944. He then served as a military intelligence officer in Eastern Europe, primarily in Bulgaria (Bulgarian being a language he had learned), when the show trials were held.

Yet the lack of discrimination in using sources drags the book down. Myles Sanderson (who seems not to be a qualified historian) has assimilated a vast number of books – many of which were new to me – but uses them in a completely unselective way. If Peter Wright (for example) states something he thinks might be relevant, he quotes it, and that goes for countless other references. Thus a large number of misunderstandings and errors have crept into his text, such as an endorsement of Wright’s fresh interpretation of Volkov’s letter, a reference to the perpetuation of SOE beyond 1946, the claim that Britain had a crew of agents working inside the Kremlin, and a simplification of GCHQ’s successes in ‘finally cracking the Soviet ciphers’ in 1976.

And a major question must revolve around the fact of whether Sanderson was an MI6 officer or not. His son even claims that his father was about to replace Philby as liaison officer with the CIA in Washington, and could even have risen to be chief of the Secret Intelligence Service – quite an astonishing assertion. Yet Sanderson pêre was a military attaché, and there is no clear evidence that he was ever strictly employed by MI6, as opposed to being someone who provided them with intelligence occasionally. Stephen Dorrill (who wrote a long, unauthorized history of MI6) expressed strenuous doubts about Sanderson’s affiliation in a brief review in 2019, and I had a similar reaction, based on the evidence shown in this book.

Sanderson was a military attaché in the key years after WWII, and that role itself induces some degree of amazement from me. What on earth would a military attaché be doing in a capital such as Sofia, except trying to gain intelligence about Bulgarian and Soviet intentions clandestinely? Such figures seemed to spend a lot of time at cocktail parties, where they would mingle with their counterparts from other western countries, and even banter with the opposition. Sanderson relates an incident where Sanderson suggests to a Soviet officer that he ‘come over to our side’, and the latter indicates that, despite his obvious criticism of communism, his life is too comfortable to be disrupted. And then, during that second tour of Sofia in 1961, Sanderson is caught photographing aircraft at an airfield outside Sofia. After claiming diplomatic immunity, he makes a quick escape across country so that he can evade the indignity of being expelled, something that he suspects would have damaged his career irretrievably. Astonishingly, he receives no reprimand on his file for behaving so stupidly. But maybe that was because it was not a surprise? Did his bosses expect him to gain such intelligence by using a camera himself, or should he have tried to use an agent? If he blew it, then he blew it, and should have been rebuked. On the other hand, might expulsion have been a point of pride in a Foreign Office career? The episode is all rather absurd.

In summary, Secret Service in the Cold War will be a rattling good educational read for the novice who is rather confused about the significance of various espionage stories during the post-war years, and how they related to each other, but will be somewhat irritating compilation for the more sophisticated reader, who will demand greater discipline, and an evident methodology in the exploitation of all the rich sources that Myles Sanderson has mined.

Lastly, I was going through the War Diaries of the 30 (Military) Mission to Moscow for 1943 and 1944 (to be found at WO 178/27 at Kew) when my eye alighted on the entry for June 8, 1943:

General Martel [head of the Mission] and Colonel Turner met General Dubinin and Colonel Sudakov, who appears to be Dubinin’s P.A. for the present discussions.

Could it be the same man? A promotion from Colonel to Brigadier by 1945 makes sense.

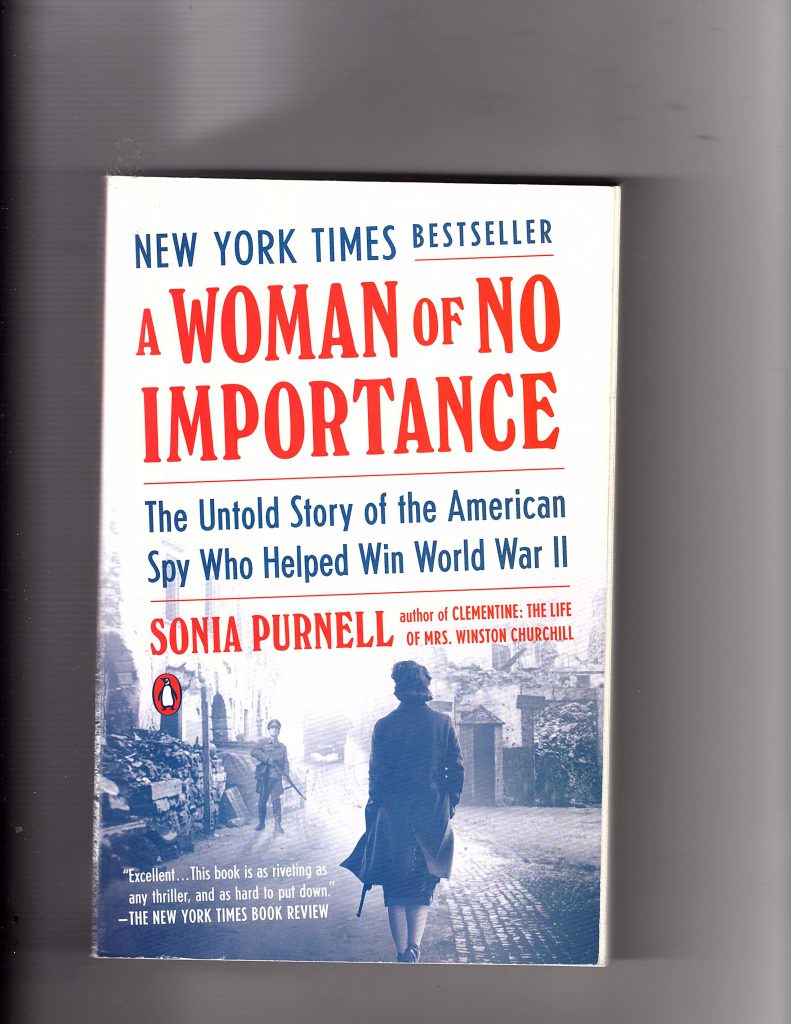

A Woman of No Importance

Sonia Purnell’s 2019 biography of the SOE-OSS agent Virginia Hall, A Woman of No Importance (which I read in the 2020 Penguin edition) arrived with an impressive set of blurbs from such as Clare Mulley and Sarah Helm, as well as a number of prestigious media outlets, even selected as ‘Best Book of the Year’ by the Spectator, the Times, and others. Were such encomia merited? I was keen to investigate.

Notwithstanding its bizarre title, the book is indeed very well written, and reflects a thorough exploration of many obscure sources on Hall’s life. It offers a very sympathetic – even hagiographic – version of the life and career of the American socialite who transformed herself (even with a partially amputated leg) into an effective recruiter and in some ways leader of guerrilla groups in southern France, working initially for SOE and then, in 1944, for the American OSS. Purnell has collected some startling information about the odious Abbé Alesch, who infiltrated F Section’s circuits on behalf of the Abwehr (and was executed in 1949), that I do not believe has been published before. (Alesch has no entry in M. R. D. Foot’s Index to SOE in France.) She describes the escape at Mauzac (engineered by Hall), and the maquisard attacks at Le Puy with great verve. The account of Hall’s escape across the Pyrenees is breathtaking. Purnell has a fascinating light to show on the relationship of Nicolas Bodington (familiar to readers of this site because of his dealings with Déricourt) with Hall. He in fact recruited her, and thus followed her progress with great interest, which must cause a re-assessment of Bodington to be made. She offers some tantalizing suggestions that the Germans may have been tipped off about Sicily (cf. Operation Mincemeat!) and about the Dieppe Raid, both stories that I need to investigate more deeply. All in all, a biography of Hall was earnestly required, and this work will fulfill that function – to some degree.

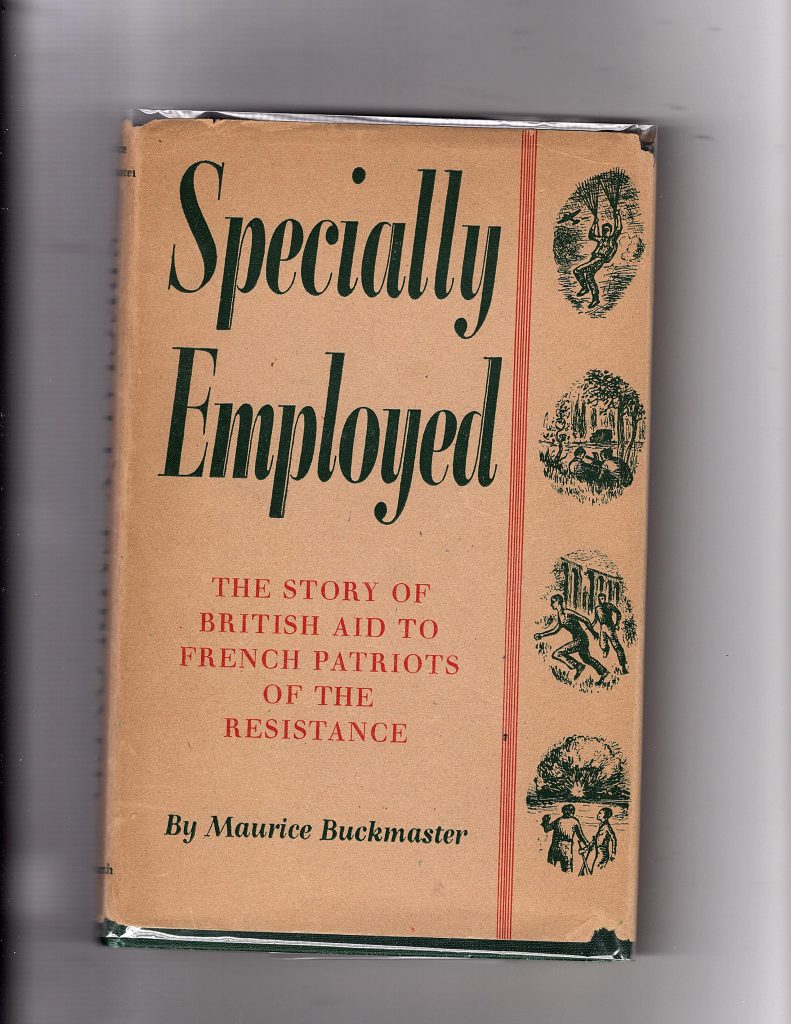

But is it a wholly reliable account? I have several reservations. I could not detect any methodology behind Purnell’s analysis of sources: she is a bit too keen to trust anything that she reads in official archives, and is caught out particularly when she quotes Maurice Buckmaster, both from his memoir and from his in-house history, which works reflect a lot of wish-fulfillment and outright deceit. It is as if the book had been compiled from a cuttings library of anything that mentioned ‘Virginia Hall’, and was then transformed into a Ben Macintyre-like adventure. The author treats SOE very superficially, neglecting even to identify officers when there is no enigma behind their identity. She overlooks the tensions between MI5, MI6 and SOE – maybe not the book she wanted to write – but in that way she drastically oversimplifies the politics that were driving subversive activities in France. She dismisses Britain’s Intelligent Services generally as being populated by ‘posh boys’ – far from the truth. She continually misuses the term ‘double agents’ when she intends to describe traitorous spies in the pay of the Germans, infiltrators, or penetration agents. She has swallowed verbatim too much mythology about German radio-detection techniques, and recounts some bizarre stories about guerrilla teams intercepting Nazi wireless messages – an assertion that cries out for stronger evidence. Her coverage of Hall’s activity under OSS, and the manner in which OSS exploited SOE resources, when SOE make remarks about her performance, is muddled. She breezes past the destruction of the Prosper circuit without any indication that she understands the way it was betrayed.

Furthermore, her narrative reflects a lot of contradictions. Even though Purnell describes Hall as continually ‘recruiting, training and arming’ guerrilla groups, it is not clear what expertise she really had. She did not go through comprehensive SOE training, and seemed to derive her expertise solely from reading the SOE Handbook, so it is unlikely that teams of raw recruits would be able to become proper saboteurs under her direction, especially given her gender. Indeed, elsewhere, Purnell reports Hall as waiting intently for experienced SOE trainers to supplement her meager knowledge. In some places, she insists that guerrilla groups had to work in isolation: at others, she indicates that they should have been more coordinated. Moreover, M. R. D. Foot plays down her role in direct operations, representing her more as a liaison officer, a role that involved a lot of travelling, but nothing too arduous or dangerous. He claims that her cover remained intact, ‘mainly because friends at Lyons police station took care not to inquire too closely into her doings’.

The coverage of the supply of arms is bewildering. Purnell observes that, as early as late 1942, the secret armies were being provided with the munitions for the Allied assault – but D-Day did not happen until almost two years later. By then, according to her, some arms had started to rot, and were frequently discarded, or even thrown into rivers in despair, contradicting the blithe statements from Buckmaster that Purnell cites. She encapsulates the activity in early 1943 in a weakly casual way (“Parachute drops of arms and explosives were generally being stepped up when clear skies and light winds permitted”), showing that she has not internalized the complexities of the situation. This topic cries out for a more close-grained analysis. Purnell moreover never resolves the ongoing question as to how closely sabotage activities were directed by SOE in London. Hall herself was admittedly undisciplined, frequently made her own decisions without approval from Baker Street, and herself complained about the wastage and unauthorized sabotage that was frequently undertaken. Foot writes that she had ‘an imperturbable temper’.

Purnell scatters her text with multiple examples of shoddy tradecraft, from ruinous meetings like that at the Villa des Bois and excessively prolonged wireless time on air, through careless and disastrous carrying of papers that revealed names and addresses of contacts, the casual mixing of circuits against instructions, the issuance of false banknotes with consecutive serial numbers, to the failure to deal with traitors ruthlessly. These patterns receive no analysis from the author, who also provocatively claims that Hall’s name was given to the Gestapo by MI6, but does not explore the implications and reasons for such a dramatic and severely troublesome move. The source for this story is probably a mysterious footnote 68 to Chapter XI of Foot’s SOE in France, where he archly reports, on Hall’s second mission in 1944: “It was not known in SOE that her real name and her role on her first mission had been communicated to the Germans late in 1943 in the course of a wireless game played by another British secret service.” (Foot chose not to identify MI6, even in 2004, unless he was simply lazy: the footnote remained unchanged after forty years.) Foot gives the impression that Hall had been re-accepted by SOE as a wireless operator at this time, since they had disqualified her as a courier, but he seems to be unaware that it was OSS who had signed her up for the second mission.

Perhaps Alesch was a figure in this dastardly MI6 plot, the details of which are probably hidden in some dusty file, and cry out for further investigation. (Was Bodington perhaps a common element in this sickly charade?) Hall herself was fooled by Alesch, even though he was reported to have come from an MI6 cell, and had not been vetted. He caused immense harm: Hall was identified, and could have been arrested by the Abwehr. The unit held off, hoping to entrap more members of the Resistance, and Hall narrowly escaped the Gestapo entry into Lyon, and consequently made her escape over the Pyrenees. Many arms-drops were carelessly carried out and equipment lost; money was handed out indiscriminately to groups who were fighting rival resistance groups as much as the Germans. Too many loose ends and unsubstantiated claims.

On one important event Purnell appears to venture a challenging opinion. When Paul Vomécourt (Lucas) discovered, in January 1942, that his wireless operator Mathilde Carré (‘La Chatte’) had become the lover of the Abwehr officer Hugo Bleicher, and betrayed dozens of her comrades, Vomécourt decided to try to play her back in the hope of deceiving the Germans. Purnell writes: “At this point, Lucas should have eliminated la Chatte, gone into hiding, and immediately contacted Virginia to let her know she was at best compromised, at worst about to be arrested.” Such an action would have reflected Gubbins’ rules (as I explained last month), and sealed the circuit from any further contamination. It is not immediately clear how Purnell derived this standpoint other than reflecting proper SOE policy.

But, of course, SOE policies were not carried out in a disciplined fashion. And Bernard Cowburn, who was an integral member of the ensuing deception concluded after the war that the attempted ‘triple-agent’ play had been successful. He considered (in his 1960 memoir No Cloak, No Dagger) that the ruse had prevented the Germans from exercising a ‘North Pole’ scheme against the French, in the manner they had exploited the Dutch, and wrote that he thought that Lucas had handled the situation in the ‘best possible way’. Cowburn met Bleicher after the war, and recorded:

He then looked at me almost pleadingly, and suddenly asked, ‘Tell me, I beg of you . . . La Chatte . . . is it true she was double-crossing me?’ This proved beyond a doubt that our manœuvre had succeeded and that for once the Germans had been properly fooled.

Yet I believe that is naïve. For Bleicher to have imagined that his mistress’s act against him was a double-cross without considering the nature of the deaths that she had incurred beforehand, was simply vain and amoral. He was probably more concerned about the shallowness of their affair. Cowburn, moreover, appeared not be aware of the more drastic ramifications of Carré’s treachery.

I think Purnell’s judgment is spot-on, although she probably derived her response from what M. R. D. Foot wrote about the incident: “The correct course for him to take was to vanish at once, not even pausing to assassinate her if her death was going to complicate her escape.” When Vomécourt eventually escaped to England, he had to be rebuked by Gubbins when he suggested that he and Carré return to France, to rescue what was left of the circuit, and also assassinate Bleicher. Gubbins put his foot down, and forbad such exploits: Carré was incarcerated for the rest of the war, then sent to Paris, where she was tried, sentenced to death, and then reprieved. She died in 2007, at the age of ninety-eight. A case-study in treachery: all a very messy business, with several lessons on how to deal with traitors, and on the perils of playing with such in the guise of thinking they can be ‘turned’ at will.

None of this sub-plot detracts from the bravery of Hall, but it does undermine the hyperbolic claims made about the contribution to the overall war success of Purnell’s subject, described in the book’s blurb as ‘the American Spy Who Changed the Course of the War’, a completely unwarranted assertion. Purnell is relentless in promoting Hall’s skills and achievements, but a less breathless assessment is called for. It appears that the author had too many sous-chefs, who may not have been rigorous practitioners themselves, assisting her researches. To write with depth and authority in this realm, you have to immerse yourself, work close to the coalface, get your hands dirty, and not rely on too many intermediaries. I do not believe that Purnell has done that.

Lastly, I note that a movie on Hall’s life is now under way, perhaps to accompany a hypothetical one on Agent Sonya, ‘the Soviet Spy Who Changed the Course of the Cold War.’ Oh, lackaday! ‘A Woman of No Importance’ is a significant contribution to the history of French resistance in WWII, but it should not be regarded as a definitive account, and needs to be integrated with and checked against more serious histories.

P.S. I should have made room to discuss Stephen Tyas’s SS-Major Horst Kopkow. I have read some clunkers on intelligence matters over the past couple of years, but this book, about the notorious Gestapo officer who engineered the sham deal with Suttill and Norman, and provided testimony that sent Kieffer to the gallows, is excellent. A must-read.

Language Corner

Regular readers of coldspur will be familiar with my high sensitivity to incorrect spelling and grammar, especially when such solecisms are committed by professional writers and broadcasters. My biggest gripe is with those who cannot deploy ‘I’, ‘me’ and ‘myself’ properly, and end up with such monstrosities as ‘between you and I’, and ‘he gave it to my wife and I’. I almost threw Anthony Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time (all twelve volumes) across the room because of his clumsy and excessive use of the reflexive ‘myself’ when he couldn’t work out whether he should have been using ‘I’ or ‘me’. I decry the decline of the subjunctive in conditional clauses, and, as a devoted student of German verb conjugation, get annoyed by any evident confusion over lie/lay/lain and lay/laid/laid.

Some of my objections are directed at the careless use of vocabulary that reflects lazy thinking, or politically correct viewpoints, such as Nobel Prize winning economists who use ‘plutocrat’ when they mean ‘rich people’ (Yes, Krugman P. at the back there, I am talking to you!), or the New York Times journalists who describe some region as ‘impoverished’, when they simply mean ‘poor’. (‘Impoverished’ implies that the region was at some time wealthy, but then was denuded by some oppressor, which is presumably the sub-marxist impression that the writers want to bequeath.)

My continuous and long-standing beef, however, is with the New York Times, and its inability to instruct its journalists to understand and use properly singular and plural forms of Latin words, even though the correct usage appears in its Style Guide. (I have been told as much.) This defect is shown mostly in the use of ‘bacterium ’and ‘bacteria’: dozens of articles over the years have deployed ‘bacteria’ with a singular verb, and I have collected the messages that I have sent to the editors in a single document, inspectable at NYTBacteria. I have surely not captured all the incidences during this period, since I must have overlooked many, and some I ignored because I forgot to write, but I believe the collection is rich enough. And now it is on-line, and the editors at the paper can use it as a teaching-tool. Bravo! (I would get out more, but my piles of books on intelligence are blocking the exit-doors.)

Bridge Corner

With the COVID epidemic ebbing, I have resumed playing face-to-face duplicate bridge, and normally play three times a week. It is an absorbing pastime, where the rewards are finding out how well you and you partner handle deals that will be played by all the other pairs of the same orientation during the session. Thus all the East-Wests compete against each other, as do all the North-Souths. The goal is to get a ‘top’ score on each hand, and minimize the disasters. One recent hand has absorbed me recently. I picked up as East:

(Spades): ♠ A K 10 9 6

(Hearts) ♥ A 6 3 2

(Diamonds) ♦ 8 3

(Clubs) ♣ 9 4

My partner, West, opened the bidding with 1 D; I responded 1 S; the opposition was silent; he replied 2S (showing 4 spades and regular opening values); and I jumped to 4S (a game contract that delivers extra points if made during the play), as I had 5 excellent Spades, and an outside Ace.

South led the King of Hearts, and West laid done his hand as Dummy, showing me the following cards:

♠ Q J 5 4

♥ 8

♦ K J 6 5

♣ A K 6 5

This was fine, but then every other pair would probably bid game, and thus face the same challenge. It looks fairly straightforward, as there is no side-suit that can be developed after trumps are drawn: win the Ace of H, draw trumps, hoping they split 2-2, take the Club winners, and trump Clubs and Hearts in both hands leaving a Heart loser, and the Diamonds to guess. (Who has the Ace? Who has the Queen?)

I thought I saw a superior play that would ‘guarantee’ 11 tricks, and maybe make 12, by exploiting my higher-value trumps, and get rid of that last pesky Heart loser, if Spades did indeed split 2-2. (And, if they don’t, I would at least match the less enterprising pairs). Thus I imagined 11 tricks: 2 Clubs, 1 Heart, 3 Spades in dummy, and 5 in hand, with a Diamond still to come as a possible twelfth. Win the Ace of Hearts, and trump a Heart. Play the Ace, then the King of Clubs, and trump the 5 of Clubs with the 9 of Spades (in case Clubs split 5-2), trump another Heart, play the last Club and trump with the 10, and lead the last Heart, trumping with the Queen. Lead the last spade to the Ace, and hope to draw the last two trumps with the King. Then see what the opponents do when I have to break Diamonds. I’ll hold on to my last trump just in case the owner of the Ace leads a Club or a Heart. (Defenders do not always keep count of the number of cards played in each suit.) South probably has two Diamonds and a Heart left, but probably not the Ace of Diamonds, as he or she might have bid over my 1 Spade with all those Hearts and the Ace of Diamonds. North probably holds two Diamonds and a Club: if he or she has Ace and Queen of Diamonds, it doesn’t matter, and just 11 tricks make (and all the ’conventional’ pairs will make only ten tricks). If South has the Ace of Diamonds, he or she will probably go up with it on the Diamond lead, and I am home and dry. If not, I have to play the Jack from dummy, losing to the Ace. I then make 12 tricks.

But I never got there! The Spades did indeed split 2-2, but the Clubs split 6-1, and South was able to trump the King of Clubs before I got going. Thus I had to guess the Diamonds properly in order to even make the game (10 tricks). Seven of the other pairs all made 11 tricks the obvious way (presumably), and must all have guessed the Diamonds correctly. Thus my partner and I received only 1 point, while seven pairs got 5 points each. A certain ‘Top’ was converted to a near ‘Bottom’ in an instant. The ninth pair made only nine tricks: presumably their East (a good player), played the same line as I chose, but mis-guessed the Diamonds. So much for enterprise and imagination. Those cursed computer-arranged hands!

The full deal:

North

♠ 8 3

♥ 7 5 4

♦ A 4

♣ Q J 10 8 3 2

West ♠ Q J 5 4 East ♠ A K 10 9 6

♥ 8 ♥ A 6 3 2

♦ K J 6 5 ♦ 8 3

♣ A K 6 5 ♣ 9 4

South

♠ 7 2

♥ K Q J 10 9

♦ Q 10 9 7 2

♣ 7

Such is the endless fascination (and frustration) of bridge. (‘A Bridge Too Far’? Do not worry: this column will not be repeated unless I receive overwhelming demand.)

Latest Commonplace entries can be seen here.