This Round-up is a typical ‘C’ (‘Congenial’) Report, offering a potpourri of observations and updates, many even serious, but none too deep or complicated for holiday reading. Impress your friends at those New Year parties by being the first with the latest coldspur news!

Contents:

Rights of Citizenship

The Illegals

What about Hollis?

‘When Philby Met Hollis’

Brian Simon’s Mischief

Lights! Camera! Action!

Agent Werther

Arthur Crouchley and the Contribution of Memoir

VENONA: When did the Soviets Rumble It?

The Mysterious Other Leggett

Jane Archer

The Letter to GCHQ

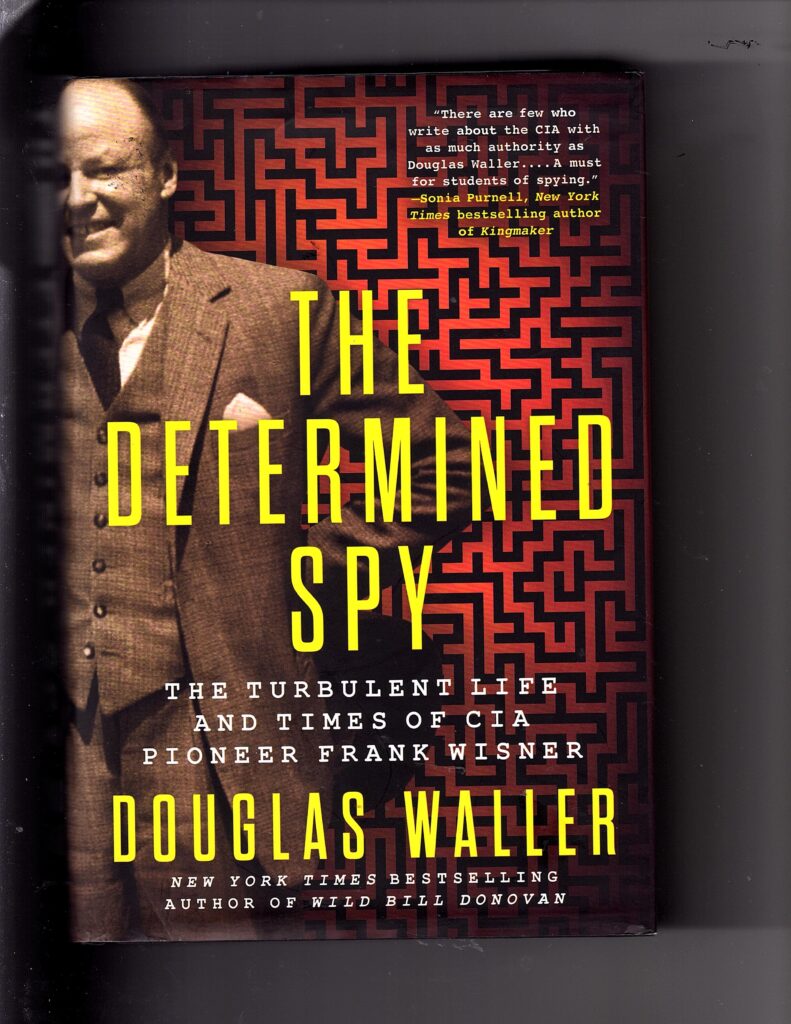

Some Books Read

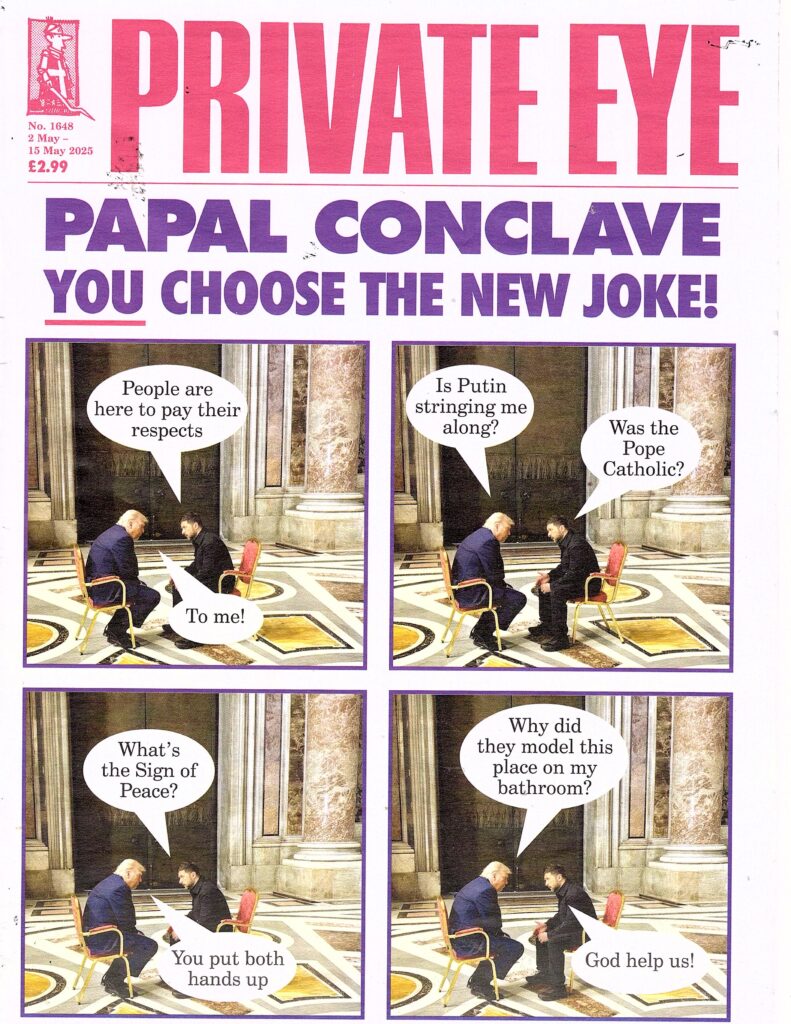

Postal Woes

‘Le Genou de Coldspur’

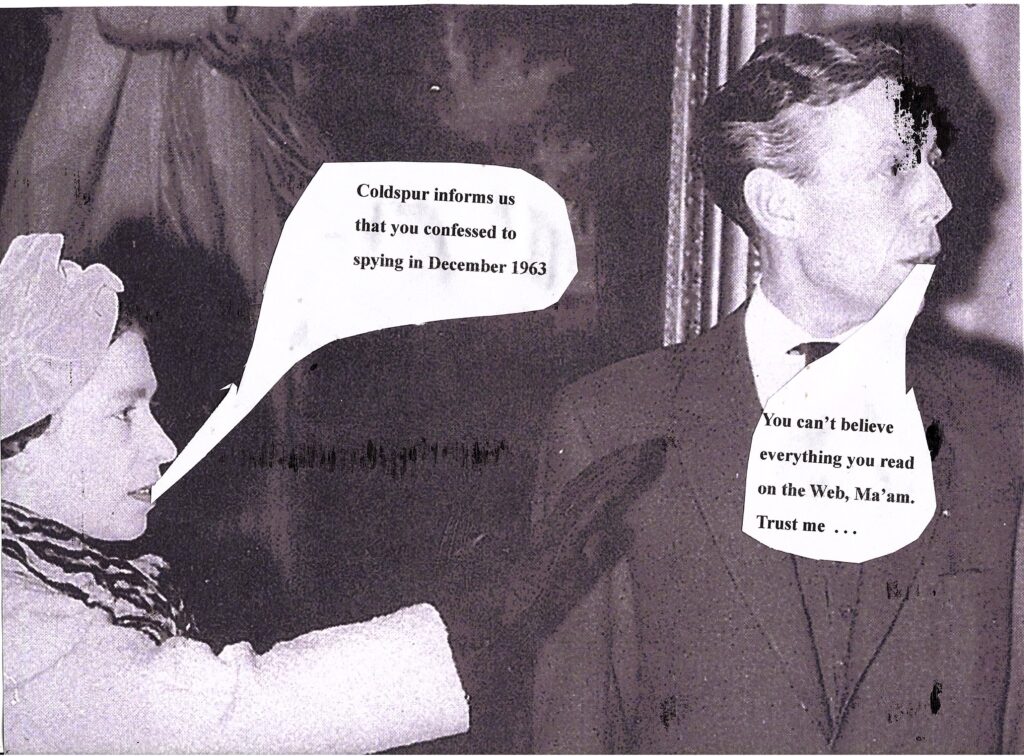

ELLI Unmasked at Last!

Quotation of the Month:

“A man in his eightieth year does not want to do things.” (Winston Churchill, from p 238 of Lord Moran’s Churchill: The Struggle for Survival 1945-1960, on December 30, 1953. I started my eightieth year on December 16, 2025.)

Rights of Citizenship

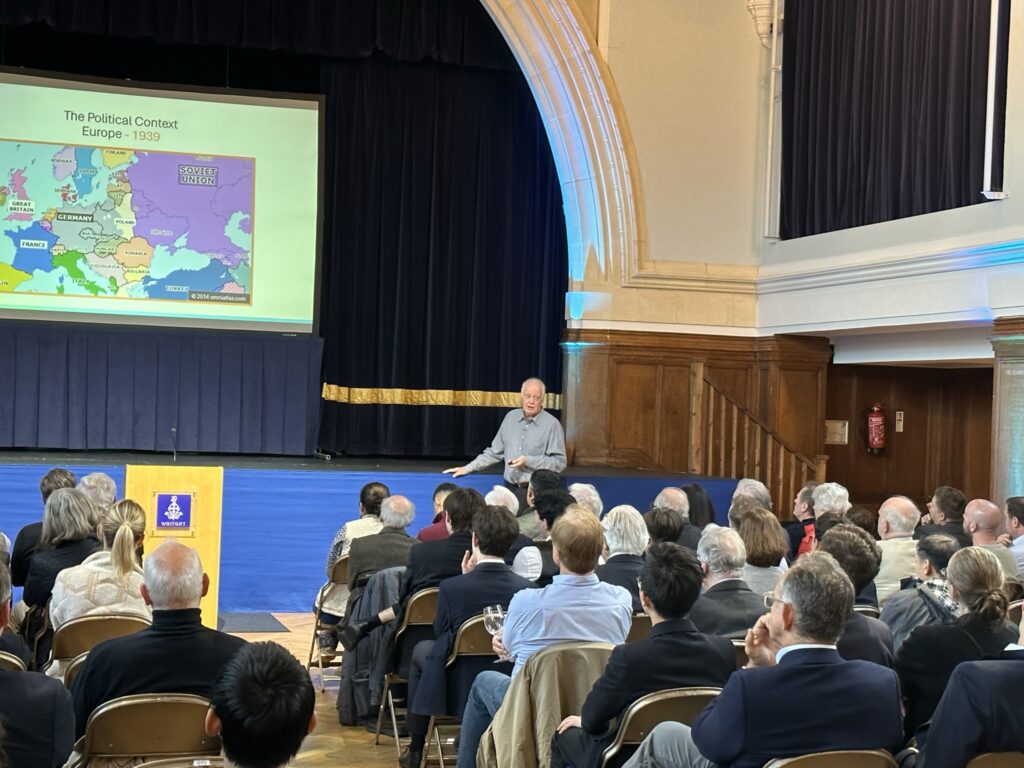

In my presentation at Whitgift School last September, I pointed out how unbalanced the laws of the United Kingdom concerning British citizenship had been in the 1930s and 1940s. The Soviet intelligence services (OGPU/NKVD and GRU) exploited the fact that, if a British man married a foreigner, that spouse would automatically gain the benefits of being a subject of the UK. Thus the Soviets were able to send to the United Kingdom three agents who had the legal cover of living and working there, namely Litzy Philby, née Kohlman, divorced from Karl Friedmann, Edith Tudor-Hart, née Suschitzky, and Ursula Beurton, née Kuczynski (agent Sonia), whose marriages were imbued with controversy.

When Kim Philby married Litzy in Vienna in February 1934, it enabled Kim to exfiltrate his new wife from the threats to her safety caused by her subversive work with the communists. My belief is that Moscow at that time regarded Litzy as the prime asset in the marriage: Kim was an unknown quantity who had obviously expressed communist sympathies through his actions in Vienna, and across the Austrian border, but it would take time for him to be able to insinuate himself into any position of strategic access to secret information. In 1933, Edith Suschitzky married Alex Tudor-Hart, a doctor of leftist views, whom she had met in 1925, and they fled Vienna for England (and then Wales) that year so that Edith could escape persecution. I do not believe that Edith’s role and importance were ever so mighty as others (especially Anthony Blunt) have made out. Ursula Kuczynski had married Rudolf Hamburger in 1929, but their union had broken down by 1939, when he left Switzerland for China. In 1940 Ursula’s visa was about to expire, and the fascist threat to her was looming. Owing to perjurious testimony from Alexander Foote, Ursula gained a divorce from Rudolf, and with the help of the MI6 office in Geneva, married Len Beurton and managed to escape via Portugal to a new life in the United Kingdom. Her career will be familiar to regular readers of coldspur.

While the Beurtons stayed married until their sudden flight to East Germany in early 1951 (and enjoyed the rest of their life together), the Philbys drifted apart soon after they settled down in London. Yet they failed to divorce – a bizarre lack of an action that would have helped Kim’s cover. Even the ‘divorce’ that Kim claimed to have occurred in 1946 is bereft of any evidence, and was logistically unlikely, so his subsequent marriage to Aileen Furse in September of that year may have been as bigamous as was Ursula Hamburger’s to Len Beurton, or Litzi’s to Georg Honigmann. It has occurred to me that the lack of pressure imposed by the NKVD on Philby to distance himself from his wife may have been due to its institutional belief that Litzy would lose her citizenship if she were no longer married to Kim, could lose her right of residency, and thus her utility as an agent would be destroyed. (Where she would have been expelled to in wartime would have been a puzzle.) Yet that was not the case. Foreign women who had so wisely selected a Briton as their partner were allowed to continue to enjoy the fruits of their decision even if the marriage failed.

That was not how it was with British women, however. Lasses were supposed to marry a solid British husband, not Johnny Foreigner. As Clare Mulley explains in her recent biography of Elżbieta Zawacka, Agent Zo, when Audrey North, a WAAF attached to the Special Operations Executive who had been brought up in Croydon, Surrey, fell in love and married a Polish officer named Kazimierz Bilksi, known as ‘Rum’, in 1944, she automatically lost her British citizenship, according to the laws of the time. When their son, Andrew, was born in 1945, Rum realised that his future lay in Britain, he settled in Croydon, and eventually became a naturalised British citizen in 1954, thus restoring his wife’s nationality, and passing it on to their children. The law that had deprived Audrey of her citizenship and allegiance had been repealed in 1948, but it had no retroactive effect.

Andrew Bilski started his education at Whitgift School a year before me, in 1955. I do not recall our ever being in the same class, but I remember him as a serious, beetle-browed young fellow. He wrote an unpublished memoir about discovering some of his father’s secrets as a daring officer in the Polish Army, titled Secrets of the Green Box, which Ms. Mulley was able to use in her book. I wonder how much Andrew knew at that time about his father’s exploits. Probably not much. Most men returning from the war were not outgoing about what they had seen and experienced, and (from my experience) ten-year-olds regarded whatever familial background they had experienced as simply being the norm, and buckled down simply to stay out of trouble, and learn from what they saw and heard.

I am not sure how to categorize this obviously masculinist legislation, with its uneven treatment of native British and foreign women, the latter being treated preferentially. Presumably, when it was crafted, the lawmakers believed that other countries would have enacted similar laws. (A research opportunity for someone.) Yet the declaration includes some strong paternalistic Victorian sentiment, satirized by W. S. Gilbert. “But, in spite of all temptations, to belong to other nations, she remains an Englishwoman” not only does not scan, it was also verifiably untrue, as Audrey North found out. And then, in 1948, Enlightenment occurred with the passing of the British Nationality Act, although I doubt whether it became law because of the Bilskis.

The Illegals

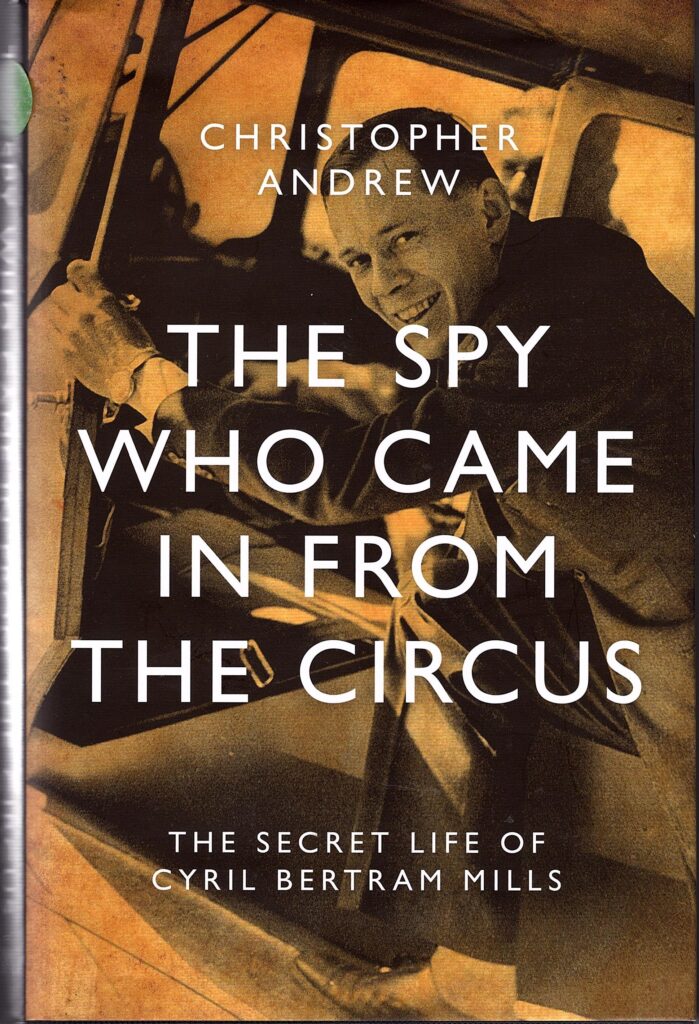

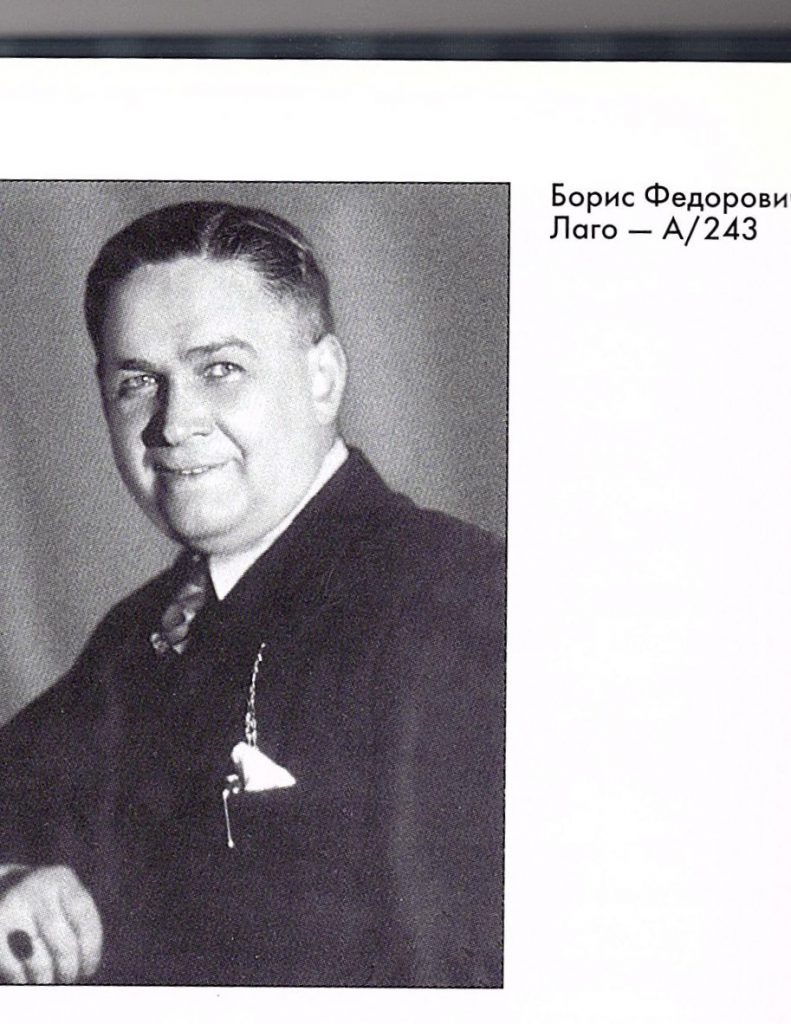

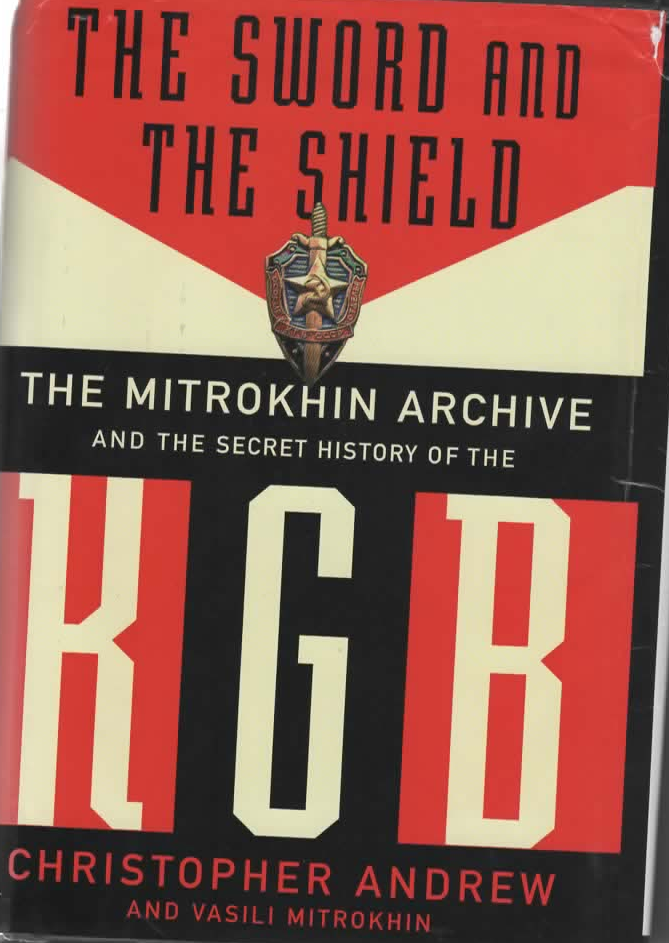

After reading my review of two books on Soviet and Russian ‘Illegals’ in my June posting, a correspondent wrote to me in early August, pointing out a few relevant chapters in The Mitrokhin Archive, compiled by Christopher Andrew from the resources of Valery Mitrokhin. He wondered whether I had overlooked what the book said about the ‘Illegals’ program. Now, I have to confess that, when I tackled this work several years ago, I SKIMMED it. I concentrated on those sections that were most important to me at the time, and failed to notice much engrossing material, of which Chapters 10, 11 and 12 constitute an important part. I have now resolved to return to those chapters.

I had traditionally thought of ‘Illegals’ as foreign citizens, working on behalf of the RIS, gaining residency in a Western democracy by means of forged identity papers, or passports acquired by illicit means. They worked in parallel with the ‘legal’ residency that functioned under the aegis of the Soviet Embassy, and were thus not protected by diplomatic immunity should they be detected in any illegal activity. By these criteria, Arnold Deutsch (who is widely celebrated as being one of the ‘Great Illegals’ of the 1930s) was not an Illegal, since he came to the UK using his own name, with a valid passport, and a declared motive of study. So long as his activities were confined to missionary work, and clandestinely recruiting agents to the Communist cause, he was a subversive, but not an Illegal. If, however, he had progressed to activities such as accepting confidential information, and acting as a courier, he would have become part of the illegal agent network. Thus there are three aspects of ‘Illegality’: false authorization of identity and residence; complementary function to the legal intelligence entity; and engagement in illicit behaviour. It occurred to me that these categories could be defined more carefully: indeed, I posited to myself that they could be covered by respective adjectives, namely ‘unlawful’, ‘clandestine’ (the default ‘illegal’,) and ‘illicit’. In turn, these have their Russian equivalents: ‘bezzakonniy’, ‘nelegal’niy’, and ‘nezakonniy’.

Having made those distinctions when I retrieved my electronic copy of The KGB Lexicon, edited by Valery Mitrokhin, I concluded that the KGB had perhaps confused the first two aspects of the term, but that the network aspect rightly dominates. ‘Illegal’ is an overloaded noun. The generic term for an ‘illegal’ in Russian is ‘nelegal’, and the Lexicon divides the group at a high level into the ‘razvedchik-nelegal’ (the illegal who is a career intelligence officer, often referred to as ‘cadre’, although that word does not appear in the Lexicon), and the ‘agent-nelegal’ (the agent of various heritage, who is not a member of the KGB, but who may have benefited from training alongside career officers). But what would a career intelligence officer be doing under cover with a false identity in a foreign country? On the other hand, if he were part of the Embassy staff, but acting as a controller of the ‘Illegals’, would he not enjoy the protection of diplomatic immunity? Overall, however, it is the status of the network, namely whether under diplomatic cover or not, that is the primary definition of ‘illegal’. Thus Deutsch, despite his proper credentials, would be classed as an Illegal because he operated and communicated apart from the official rezidentura. I shall return to these definitions, since a glimpse of what Mitrokhin had to say was a bit of an eye-opener. I am going to have to defer proper analysis to a later coldspur post, however.

P. S. As I was putting this piece to bed, and going over it with my Chief Sensitivity Reader, I came across a passage from Peter Wright’s Spycatcher, on page 381, that I must have overlooked. Wright is discussing ELLI with Burke Trend, who has just remarked that there is no mention of ELLI in the intercepted traffic. “But I didn’t expect there would be”, replied Wright. “ELLI is an illegal, and, if that‘s the case, his communications would be illegal, not through the Embassy. If we found Sonia’s traffic, I am sure we would find ELLI. But we can’t.” So ELLI was an illegal, was he? That would appear to exclude Hollis from the lists of suspects, would it not? And since Sonia was in the country legally, as a British subject with a public identity, where would that place her? Moreover, after an initial foray, she sent all her information from Fuchs via her brother to the Soviet Embassy. Where does that leave things, Peter?

Daydreaming, I also noticed that ‘ILLEGALS’ spelled backwards becomes ‘SLAG ELLI’. I happened to read recently a story on the Internet that claimed that the ‘Great Era of the Illegals’ was all a hoax, since ELLI had infiltrated it as early as 1933, and passed on its secrets to MI5. The result was that several illegal cells were disbanded, and many of its members soon revolted in a campaign against the traitor, demanding he reveal himself, and then decamp. [Is this true? Ed.] Reading about that little saga prompted me to come up with a suitable palindromic summary: “OGPU Illegals wonder if ‘Era’ was stolen: indeed, nine (lots saw) are fired, now slag ELLI: “Up! Go!!”’. Is that significant, perhaps? I know that my correspondent Michael Morris would think so. In any event, it acts as a perfect segue into the next section.

What about Hollis?

One of my correspondents recently asked me (before my October posting on Hollis during World War II): “Do you know if the suspicions about Roger Hollis have definitely been laid to rest?”. I was intrigued, since it was on the surface a very valid and important question, but it is essentially unanswerable. After all, where is the Court of Appeal in which such matters might finally get resolved? On the other hand, there is no ‘definitely’ or ‘finally’ in historiography, as we who analyze the evidence should accept that something new will always come along, and conclusions may have to be revised or annulled. There should, however, be some open ground where the state of the game can be assessed.

So to whom should we look for a jury? To the experts and doyens? Nigel West seems to have gone into retirement, and is not publishing much new. Christopher Andrew, who may not even be responsible for the books now coming out under his name, has likewise largely disappeared from the public sphere. Moreover, he must have undermined his authority when he firmly announced, after collaborating with Oleg Gordievsky, that ELLI was certainly Leo Long. Richard Aldrich writes some splendid prose, but is frequently careless, and Calder Walton is likewise not disciplined or inquisitive enough to step into the shoes of intellectual leadership. By a similar token I see Michael S. Goodman, Charmian Brinson and Christopher Murphy as doughty chroniclers unwilling to put their head above the parapet. Jonathan Haslam has performed some impressive work, but lacks a strong public image, and now concentrates more on current politics. Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones? I had almost forgotten him. He has been productive, but has focussed more on USA matters, as has Christopher Moran, after his useful and entertaining Classified was published in 2013. Stephen Dorril, of MI6 and Lobster, is still around, but has been quiet recently. Michael Smith is another historian of MI6, and, while describing himself as a ‘journalist’, has been productive for a number of years writing books on intelligence. Ben Macintyre sparkles, but he is a journalist, not an historian, and we don’t forget his stumbles over Sonia. John Hughes-Wilson was an outside candidate, but he died recently. Richard Norton-Taylor, sometime with the Guardian, has been praised as a ‘doyen’, but he is more of a playwright than an historian, and, apart from a shared work on trade unions at GCHQ, has not undertaken the arduous process of writing a book.

What about the serious journals? I do not subscribe to any of the major three, the Journal of Intelligence and National Security, the Journal of Intelligence History, and the International Journal of Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence (all part of the Taylor & Francis stable), owing to that outfit’s punitively expensive policies for the independent historian. Yet, from a scan of their recent Contents pages, I conclude that I am not missing much. JINS appears to concentrate on more theoretical and sociological aspects of intelligence, JIH, naturally, on the historical, normally going back some way beyond the events of the last seventy years, while IJICI assumes more of an ethical stance. They all seem rather cautious in their approach to recent controversies (as does History Today, by the way). It is as if the problematic events of half a century (roughly from 1934, when Philby was recruited, to 1988, when Spycatcher was cleared for sale), are too remote to be of current interest, but too recent to be re-assessed seriously, because so much of the relevant archival material remains unreleased.

What is really needed is a forum to thrash these matters out. The Cambridge Intelligence Seminar (convened by Professor Andrew) would appear to be a good candidate, as the topics it offers are generally relevant. Yet it all looks rather exclusive, the talks are spread across individual days in the termtime, and its seminars are not record for posterity. The convention needs to be more public, more formal, more structured, and held in London. Might an institution such as the Royal Historical Society host such a show?* In that way, outstanding questions could be aired and discussed, and some methodology applied to processing the fruits of such as Chapman Pincher or Peter Wright, who have influenced public opinion so unduly. Perhaps a two-day seminar at Lancaster House? I would be delighted to contribute, as I could offer opinions on a number of fascinating topics. Indeed, I discussed this challenge in a coldspur piece in 2018, where I even presented ‘An Alphabet-Sized List of Intelligence Mysteries from WWII & After’ (see https://coldspur.com/confessions-of-a-conspiracy-theorist/). That list is a mixture of the wildly controversial and the mildly absorbing, so I would reconstruct it to focus on topics of major interest. I thus present the following intelligence conundrums:

- Who Was ELLI?

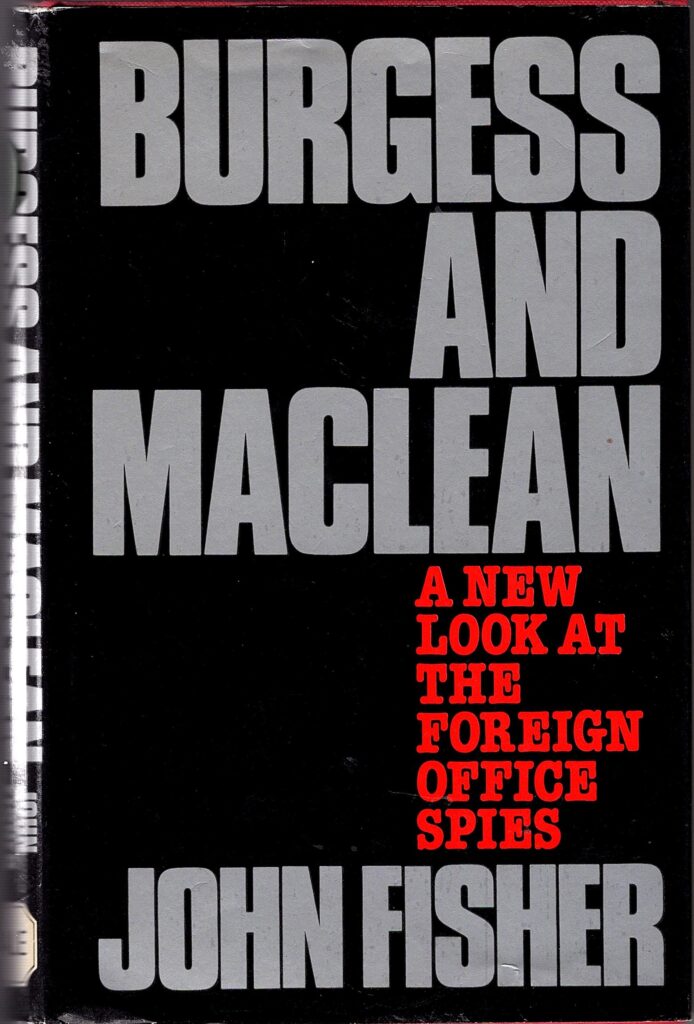

- How Did Burgess and Maclean Manage to Escape?

- Was Philby ‘Always Working for SIS’?

- Why Did Flight PB416 Crash?

- How Did Blunt Stay Unmasked for So Long?

- Was PROSPER Sacrificed?

- Did Gibby’s Spy Exist?

- Did Borodin Defect? Why Has His Case Been Suppressed?

- Why Were the Germans Taken In by Double-Cross?

- Why Was Agent SONIA not Detected?

- How Much Damage Did George Graham Cause?

- Did ter Braak Commit Suicide?

- Did Churchill Use the Rote Drei to Pass ULTRA Information to Stalin?

These items should probably be pared down to a core of ten, which would provide a substantial feast. And then perhaps a book could be written on them, to provide a ‘state of the art’ summarization to satisfy my correspondent’s question. Is there anyone out there with contacts at the Royal Historical Society, or a publisher, to get things weaving? I am ready to play my part.

[* I am reminded of those important scientific congresses that took place, mostly in the nineteenth century. Gordon Rattray Taylor pointed out how disputatious matters were addressed when he wrote: “ . . . when a panel of eminent geologists was asked to vote on the question ‘Is Eozoon canadense of organic origin?’ at the International Geological Congress of 1888, the vote was ‘No’ nine to four.”]

‘When Philby Met Hollis’

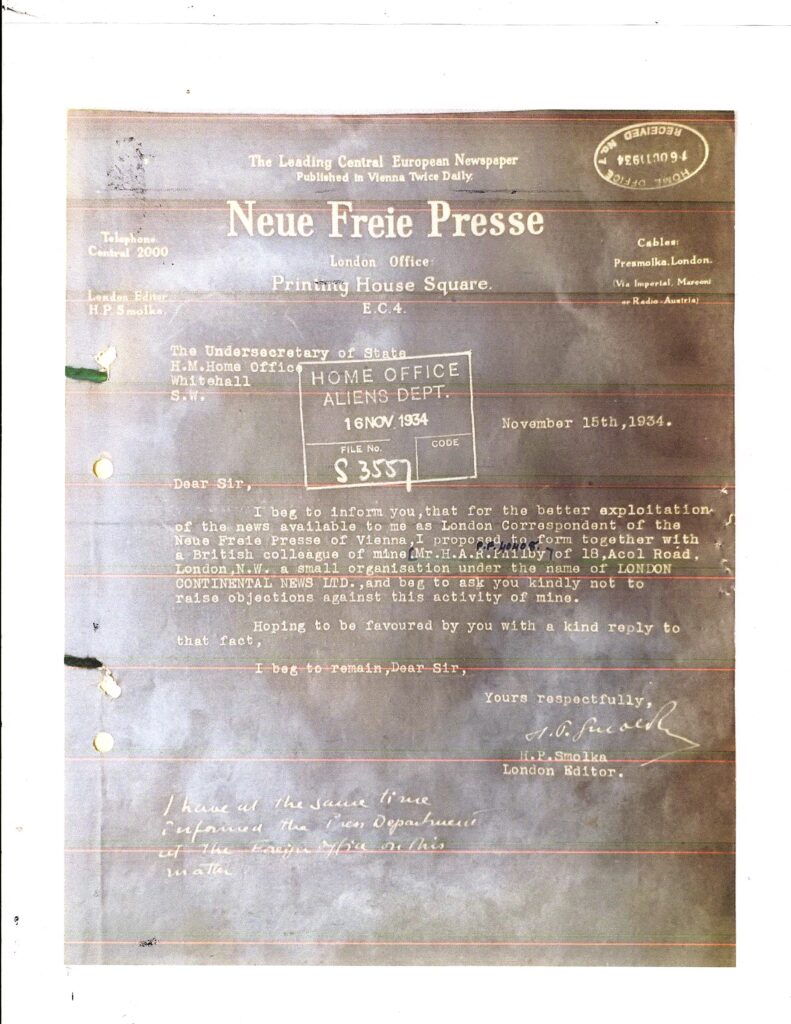

A short time ago, I read somewhere that Roger Hollis had divulged to Kim Phlby, probably in 1945, how his F2 organization worked. Since I had claimed to cover Hollis’s activities in WWII quite comprehensively two months back, I thought to ought to investigate this story while the events were still fresh in my mind, and not too much water had passed down the Volga. It turned out that the account of the event appeared in a report that Philby sent to his controllers in Moscow, and it is published in a compilation titled The Secret Agent’s Bedside Reader, edited by Michael Smith (the author of Part 1 of a history of MI6 up to 1939, titled Six: I am awaiting the second volume), which was published by Biteback in 2014. I therefore had to acquire it, and indeed, a statement at the end of the chapter claims that ‘the above document is held at the SVR Archives in Moscow’. Who accessed it, and how it was delivered, are not stated, but it looks kooky enough to be both genuine and authentic.

Smith’s Introduction states that Philby’s report was in fact written in October 1944, when Philby was ‘in his new role’ as head of Section IX, the Soviet counter-espionage unit. Philby did not assume leadership until Curry relinquished it at the end of the year, but he was obviously waiting in the wings at this stage. The interview was at Hollis’s request, seeking future collaboration with him and his own anti-subversion section, F2, which was then working out of Blenheim Palace.

One might step back and consider the possible combinations of roles and knowledge assumed by Hollis in engaging Philby: what were his intentions? I see four profiles:

- Hollis is a penetration agent (of the GRU), and believes or knows that Philby is likewise (of the NKVD).

- Hollis is a penetration agent, and believes Philby to be a loyal British intelligence officer.

- Hollis is a loyal British intelligence officer, but suspects that Philby may be a Soviet agent.

- Hollis is a loyal British intelligence agent, and believes that Philby is likewise.

If ‘1’, Hollis and Philby (especially if the latter knows of the former’s role) would be very cautious about meeting alone. Besides, Hollis would have already informed his controllers of his organization, and would not deem it necessary to brief Philby, certainly not at length. Philby would wonder why he was being told all this: he gives no indication in his report of Hollis’ allegiance as a ‘friend’.

If ‘2’, Hollis might want to go through the formalities, but would not want to give Philby more information than he really needed to know. He would not have wanted any exterior officer snooping on his turf, and would have waited for an overture by Philby.

If ‘3’, Hollis would be very cautious about giving Philby any information at all. He would have raised his suspicions with his boss, Petrie, who, if he shared Hollis’s knowledge of Philby’s history and was suspicious of his apparent volte-face, would have supported his policy of reticence.

If ‘4’, whether he thought that Philby had always been clean, or had the insider knowledge that in 1939 he had switched his allegiances, and trusted him, Hollis would have warmly welcomed Philby’s imminent appointment, and sought out ways to collaborate. There were no other reasons to doubt Philby’s loyalty in 1944.

The sketch that Hollis gives Philby has some intriguing highlights. He tells him that B Division was split into two ‘as the war got under way’, with one part dealing with enemy espionage and sabotage, and the other with subversive political movements and Soviet espionage, from which F Division was born. (We know that this is not completely true, however, because of Dick White’s shadowy operation against the Beurtons, for instance.) He describes how F2 (the anti-communist section) is split into three, with Hugh Shillito having a symbolic supervisory role in heading F2B (it was better to have a man in charge!), which is in practice run by Milicent Bagot. Bagot deals with foreign communists in the UK, Shillito with Soviet espionage, although how they divvy that work out, or make their determinations, is not clear. Hollis considers Bagot the most valuable member of the whole Division: she has been working on the transnational Communist problem for over twenty years, and has an encyclopædic knowledge of the subject. (Not information you would want to pass on to a suspected spy.) While Hollis judges that Shillito works well on details (such as his work on the Oliver Green spy case), he says that he is not so comfortable with the broader picture.

Hollis then continues to describe various techniques and relationships: his dealings with the ‘Watchers’; his use of Maxwell Knight’s agents, who spy for the whole of MI5; telephone checks and postal censorship; and most vital of all, the microphones inserted in CPGB headquarters, from which F Division derives ‘about seventy pages of information a day’. Philby overall gained a good impression of Hollis, who, he said, put forward ‘the view that Soviet policy might well be designed to make the Anglo-Soviet pact a reality, and consequently to temper the revolutionary spirit of the Communist Party’. (Dream on, Roger!) Hollis added that it was very difficult to monitor the Russian [sic] Embassy or the Russian Trade Delegation, and no Soviet officials were being shadowed partly owing to the timidity of the Foreign Office.

Philby also shows from his report that he has been in direct contact with David Clark of F2a. Clark offered him useful information about the Springhall case, and updated him on the escape of Graur (see https://coldspur.com/to-be-perfectly-blunt/ ), who left the UK a few days after Springhall’s arrest. Clark also told him how he had tricked the name of Desmond Uren (the spy in SOE) out of Helen Grierson in Glasgow, and Clark also pointed him towards two defectors (one named Yegoreff), both former NKVD officials who had been captured by the Germans. One of these had told the true story about the Katyn massacre.

Thus it sounds like a second-rate but loyal officer trying to bolster his achievements, and foolishly giving away more than he needed to. Philby lapped it up.

Brian Simon’s Mischief

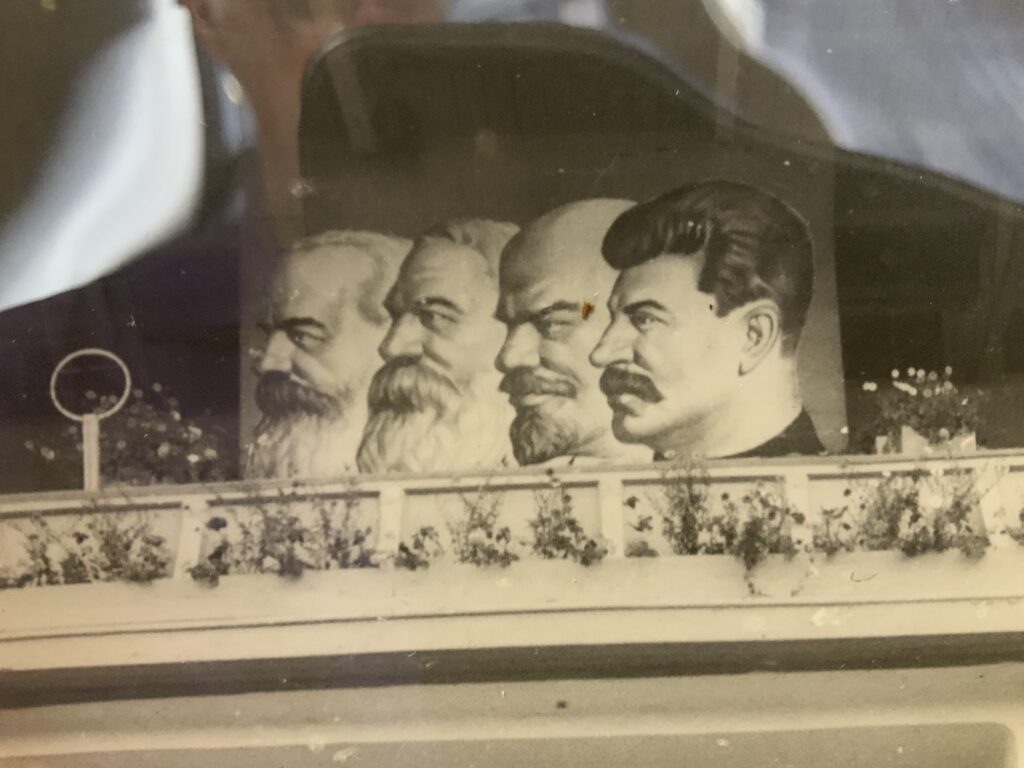

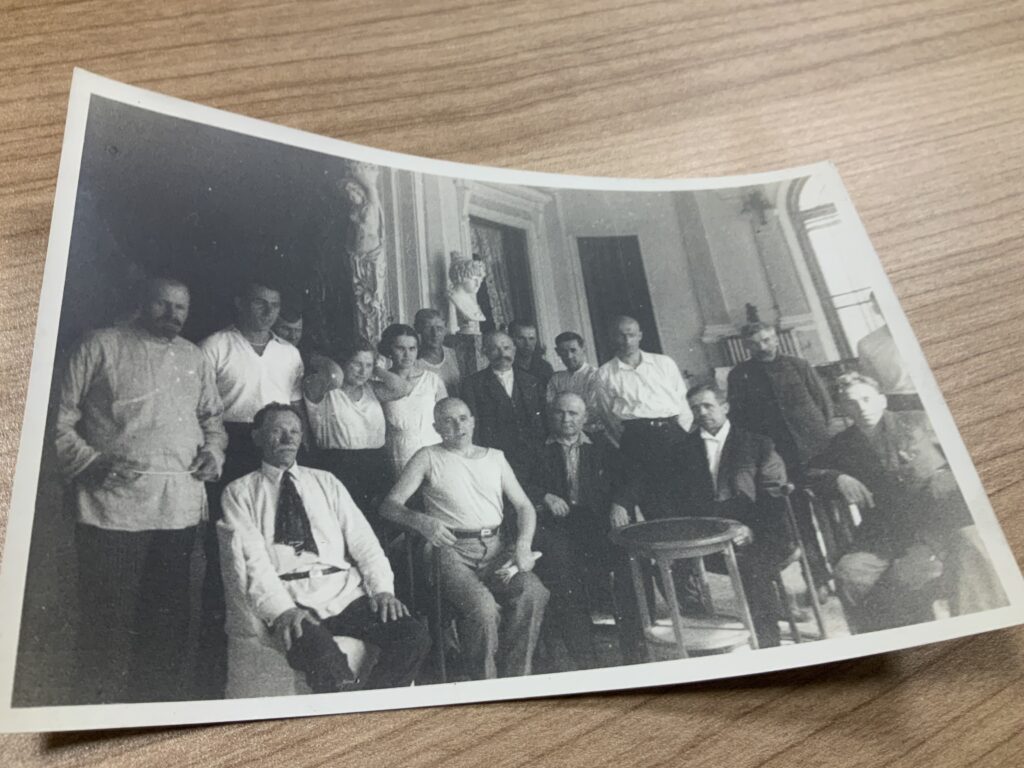

In my September report, I described how I had studied the material concerning Brian Simon’s visit(s) to the Soviet Union in the 1930s, viewable at the Library of University College, London. I pointed out that the first file in the ‘Visits Abroad’ section, 6/1, is simply titled ‘Soviet Union’, but contains no text of memoir, only a selection of photographs and postcards. I showed, however, that one of the postcards was dated 1936, so it obviously could not have been gathered while Simon was on the well-documented 1935 tour of the Soviet Union with Anthony Blunt, Michael Straight, Michael Young, Christopher Mayhew, and other worthies. On my return to the USA, I was able to inspect the remaining Simon PFs that Kevin Jones had photographed for me, and I discovered that he had indeed been detected in visiting the U.S.S.R. since his initial tour.

The evidence is at sn. 8a in KV 2/4175, and is dated September 1, 1937. When Simon arrived at Dover from Calais, an immigration officer checked his passport, and noted that Simon ‘has recently visited the U.S.S.R.’. Since all sailings from the UK to Leningrad were carefully watched (and Simon was already being surveilled because of his communist sympathies), it is clear that Simon must have travelled to the Soviet Union via another country, and that, furthermore, his visa arrangements must have been made surreptitiously on his behalf, which is somewhat alarming. He could not hide his itinerary completely, as there must have been entry and exit stamps from the intermediate country. J. Blackburn of Special Branch put in his report, noting that ‘a discreet search of his baggage by H. M. Customs revealed nothing of interest to Special Branch’.

MI5 must have taken a sharp interest, because, on September 10, the Passport Office replies to a request from a Miss Tughill [?] to see Simon’s Passport Office file. Indeed, the request appears to have been submitted by Kathleen (Jane) Sissmore via S.3.a, since the signature indicates ‘M.G. for K.M.M.S.’, and a request was received for the papers to be returned on September 15. The request contains the Passport number (LO 49049) and simply echoes the statement that Simon ‘recently visited U.S.S.R.’ Someone has inscribed: ‘1935 – or more recently?’, which would suggest a keen interest in knowing more about the subsequent visit. ‘Recently’ does not sound like 1935, in this context, yet the outcome of the inspection has been lost.

Nothing much happens until January 1940, when an anonymous memorandum, probably from ‘DVW’, is sent to Roger Hollis, asking for information on Simon, since he has been reported as being in touch with ‘various aspects of the Student Movement in India’ – always a dangerous threat of subversion. On February 2, Hollis replies to ‘I.P.I.’ (not the International Press Institute, but an MI5 department involved with Indian affairs). He provides some details about Simon’s career to date, mentioning that he spent a months [sic] holiday in Russia in 1937, but writing nothing about the suspected follow-up visit. Rather a lazy effort, Roger, but why had your recent boss, Jane Archer, not followed up and made an entry in the file? If a customs officer could spot an anomaly, why could B4 not do the same?

As I recorded in a note to my August piece on Astbury and Simon, I spotted also an entry in Goronwy Rees’s PF (KV 2/4608, sn. 400c), dated May 2, 1966, where Peter Wright recorded an interview with Blunt. He wrote: “That, so far, people identified as spies had not suffered the due consequences of the law. For instance, he himself, Leo LONG, John CAIRNCROSS, Brian SIMON and Peter ASTBURY were all still free men.” That would appear to seal the deal for Simon as Number Eight of the Cambridge Spies. (It is an extract, paragraph 5, from Wright’s full report on the interview on April 27, available in Blunt’s PF at KV 2/4709, sn. 439b.) It is possible, of course, that Wright may simply have been echoing Blunt’s anecdote about Simon and the GRU. Simon may have been an agent, and a dangerous one, but never actually handed over any confidential material. The significance of this posting is that the hint about Simon had been in the public domain for three years before the full record was issued in the Blunt PF earlier this year.

Simon was a thoroughly bad lot, and I suspect there is far more to be discovered. I was slightly amused, when dipping lightly into his file of correspondence at UCL, to find an exchange of letters between him and Boris Ford of the Turnstile Press in December 1955. Simon had submitted an article titled ‘Educational Standards in the U.S.S.R.’, and Ford had rejected it on the grounds that it was not objective and lacked evidence to support its conclusions. Simon was indignant, and responded with one of those ‘Don’t You Know Who I Am?’ letters. But Ford stuck to his guns, and carefully and politely spelled out where he thought the article was at fault. At least Simon kept a record of the correspondence.

Lights! Camera! Action!

I have recently referred to the fact that I have been slowly catching up with my movie-watching: last January I reported that I had just watched The Fourth Man, and expressed my intent to watch Philby, Burgess and Maclean, distributed in 1977. I achieved that goal this summer, and also re-watched Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (the original with Alec Guinness), as I had only a hazy recollection of the action, although certain scenes (Jim Prideaux at the preparatory school, the interviews of Connie Sachs) had imprinted themselves quite sharply on my mind. It was an intriguing exercise: PB&M was quite well done, I thought, although it suffered from having been created before the Blunt disclosures came out, and his absence from the screenplay made it rather awkward and flat. And I had to sort out what the actor Anthony Bate was up to. He played Philby in PB&M, but I thought he was badly miscast, not having the charm, guile and personality that attended the real Kim: Bate was much more appropriate as the rather dull civil servant Oliver Lacon in TTSS.

Seeing TTSS again was something of a surprise. First of all, I had to watch the American version, which was compressed from seven into six episodes, with the consequent loss of several scenes. I am sure that the conversations between Smiley and Sachs were one of the casualties, as I remembered them being much longer in the British TV series in the autumn of 1979. I had completely forgotten the marvellous encounters between Smiley and Roddy Martindale, the latter played with great panache and style by Nigel Stock, who had been a memorable Dr. Watson. In my naivety, I had back then utterly failed to grasp the significance of the relationship between Ricki Tarr and Irina, which was now all clarified. I appreciated much more the feline performance by Michael Aldridge as Percy Alleline. And Smiley was exactly as I had remembered him, down to the polishing of his eye-glasses.

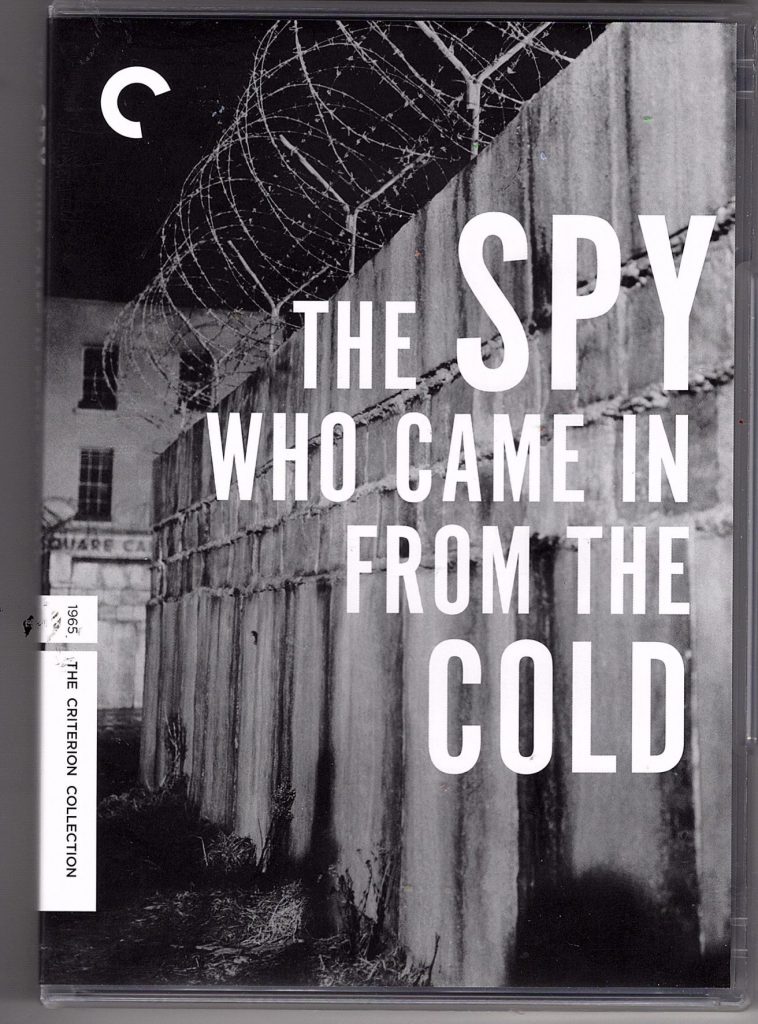

Yet I was shocked – yes, shocked – by one scene in particular, and that was the ambushing of Jim Prideaux in Czechoslovakia, as he goes out to try to rendezvous with the Czech traitor General Stevcek. (Prideaux was played, incidentally, by that fine actor Ian Bannen, whom I had first seen as a very striking Hamlet at Stratford in 1961.) Readers may recall my bewilderment at the clumsy plotting, and absurd melodrama, of le Carré’s The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, in 2022 (see https://coldspur.com/2022-year-end-round-up/), when I commented on the highly improbable way in which Leamas and Nan Parry were allowed to escape to the Wall, only to be shot down. The shooting of Prideaux was an exact echo of that shoddy misrepresentation of how a Communist secret police force would act. They would have spirited Stevcek away, and arranged for Prideaux to have an unfortunate accident. What they would not have done would be to set up a noisy and attention-drawing shoot-out, the details of which were bound to have escaped after the event. Not only that: dozens of sharpshooters appear to be on the scene, but their aim is so bad that Prideaux receives only a couple of non-fatal bullets in the back, which allows him to be captured alive. And then he is later exchanged in a spy-swap, so that he can recount the gory details on his return. What was le Carré thinking?

It occurred to me that perhaps the screenwriters had got carried away, and that the author might not have been aware of what they did, or that he had been overridden because the producers needed some action. But that didn’t sound like our old chum le Carré, at all. So I went back to the text: pages 250-251 in my 1975 Pan edition. There it all is – theatrical shooting, floodlights, flairs exploding, Very lights going up, even tracer. Driving the car away, ‘he was almost clear – he really felt he was clear – when from the woods to his right someone opened up with a machine-gun at close quarters.’ More bullets flew. “The woods must have been crawling with troops.” Two shots caught him in the right shoulder, and then an ambulance came. (It was thoughtful of the Czechs to arrange for emergency medical services in the event that there might be non-fatal casualties from the assault.) But had it not been the intent of the Czech secret police to murder Prideaux, what with all that fire-power? Machine-guns?? So why did they take so much trouble to try to kill him, if they needed to grill him about the organization back in London? In any event, he was taken to a prison, interrogated intensely, and then to a camp, where he recuperated, until one night ‘he was taken to a military airport and flown by RAF fighter to Inverness’. Just like that. “With one bound Jack was free.”

The flaws in le Carré’s understanding of espionage tradecraft were brought home to me when I read about the current exhibition at the Bodleian, ‘John le Carré: Tradecraft’, an attempt to highlight the writer’s craft with the pen or typewriter. For instance, Literary Review of November 2025 offered a two-page encomium to the author’s meticulous plotting, referring to ‘the intricate grisaille of his fiction’. (“Search me, guv.”) John Phipps (whose qualifications are stated to be that he ‘is a contributing writer for The Economist’s 1843 magazine, and lives in London’) went on to write: “Yet as this exhibition makes clear, he worked hard to leave his readers with an impression of more-than-fictional truth. ‘Espionage is one of the few proud cases’, he [le Carré] once wrote, ‘in my thoroughly biased view, in which historical truth has been better served by fiction than by . . . confections of warmed-up fact.’” Towards the end of his appreciation, Phipps wrote: “No one could match the brilliance of his plotting, or imitate the unfolding and rambunctious poetry of his prose.” No further questions, m’lud.

Agent Werther

One of the most astonishing books I have read this year was Louis Kilzer’s Hitler’s Traitor. I do not recall where I saw the reference to it, or the recommendation for it, but its subject matter made it a must-read. The topic is the betrayal of German battle plans through the Red Army spy-ring in Switzerland to Moscow Centre. It was published in 2000, but for some reason I had overlooked it, despite my deep interest in the activities of the Rote Kapelle, Agent Sonia, Alexander Foote, Rado, and all the rest of the gang, about which I have written much. The author’s thesis is that the source of the information, known as Werther, was none other than Martin Bormann, who had replaced Rudolf Hess, after the latter took flight to the UK in 1941, as head of the Nazi Party, and was a close adviser to Hitler. Kilzer died last year.

Apart from indicating that Bormann had motive (he was a secret admirer of Stalin’s communism), opportunity (he was present at all cabinet meetings, and controlled the secretariat that recorded decisions), and means (he had access to a private Enigma machine and transmitter that could make contact with agent Lucy in Switzerland, similarly equipped) Kilzer founds his case on the assertion that Soviet archives show that the nature of the intelligence sent (such as who attended particular meetings) could have come only from someone in Bormann’s position. While giving due credit to the notion that Churchill revealed Enigma-derived intelligence, in disguise, via the Swiss network, using the known entity Alexander Foote as the wireless transmitter, Kilzer asserts that the British could not have derived the variety of specialized information which the Soviets received from intercepted and decrypted Enigma messages. (And nor could spies like John Cairncross, for example, who was awarded a medal for his intelligence on Kursk.)

I found this thesis quite extraordinary. The idea that a high-up like Bormann could endanger himself and others in such traitorous behaviour, causing the loss of life of hundreds of thousands of German and other Axis soldiers, and get away undetected, simply did not make sense to me. (Other traitors have been suggested in the literature, such as Oster, but they also fail the smell test.) How the Gestapo and the Funkabwehr could not have noticed that a couple of spare Enigmas were being regularly used, and that their resultant communications were not picked up, defies comprehension. Moreover, the exercise would have required a vast effort of diligent work performed by clerks and others to compile the information, and keeping those activities clandestine must have been an enormous challenge. Furthermore, Kilzer claims that Moscow was so impressed with the intelligence received that it sent detailed questions back, which were sometimes answered within twenty-four hours.

For example, I quote the following nonsensical passage (p 172):

The next day, the Center ordered Rado to get from Lucy ‘information on the Caucasian front and the most important news on the eastern front as well as the dispatch of new divisions to the eastern front without delay and with priority over all other information.’ [Source: RG 319, Box 59]

Werther acted immediately. Within twenty-fours of receiving [sic!!] this request, the Center sent the Swiss net the following message: ‘Our thanks to Werther for the information on the Caucasus front.’ [Source: Rado, p 153]

It was here that my credulity snapped completely. If one considers the stages that messages had to go through, such speed was physically impossible. By the end of 1943, Foote was the only radio operator left, and he had to take on the whole load himself. Rado did not operate a receiver/transmitter. Foote did not know any Russian: he had some French and elementary German. He had his own codes. He received instructions from Moscow, which must have been sent in English. He claimed he did not have time to read the messages he processed, implying that they were written in English before he decrypted them. That means that questions would have to be translated from Russian to English before being sent to him. He then had the arduous task of decryption, which often kept him up all night (from 11 pm to 9 am). Any encryption/decryption or transmission errors would mean that the process would have had to be re-started.

What next? Foote resided in Lausanne. He had to take the transcribed messages to his boss, Alexander Rado, at a pre-arranged meeting-point, probably after a phone-call. Rado lived in Geneva, about fifty miles away. After they had been handed over, someone would have to translate them into German, perhaps Rado, perhaps the next person in the chain. Rado (who never met Lucy, a man named Roessler) then had to travel to Lucerne to meet Roessler’s cut-out, Rachel (Sissy) Dübendorffer, who was very protective of her source, and did not allow anyone else to meet him. Lucerne is about one hundred and sixty-five miles from Geneva: more impromptu arrangements to be made for the handover, and then a meeting with Lucy arranged. After translation, Roessler would have to start work on his Enigma in order to get the requests to Berlin as fast as possible.

But the Enigma was not an automated transmission device. It was an encryption machine. Photographs of the device in use show that it really required two operatives to use it effectively – one to dictate the source message, and another to enter the characters for encryption and read out the result from the illuminated panel, so that the first operative could transcribe it. That would have been an immense challenge for Roessler, who was not known for being savvy with advanced equipment, and had not evidently undergone specialized training. He would have worked at night as well, so someone (or preferably two persons) would have to be available all the time the other end in Berlin to receive the message, decrypt it, and present it to Bormann for analysis and action. And then the whole operation would have to be initiated in reverse.

Kilzer never analyses the logistics of this whole enterprise, let alone suggests that it is a problem in his theory. He just ignores it. And I have not yet found anyone who throws cold water on his story. Yet it is patently absurd to conceive that such exchanges could occur so smoothly over such distance, and through such a long chain, with all the corollary complications that I have spelled out. You can look up Wikipedia for the Rote Drei, and Lucy, and Werther, etc. etc. , but the entries are a complete mess, tripping over each other with contradictory claims. Kilzer’s book is mostly totally ignored. (I encourage anyone who has found a serious and deep review of the book to let me know where I may find it.)

So what is the explanation? First of all, the Soviet archives may be largely a hoax – some reconstructed items to accompany what were genuine messages, perhaps in an attempt to annul the fact that the Red Army had depended on help by Great Britain. Thus the exclusive link to Bormann and his cabinet could be an utter lie. Second, there might have been a direct link from Berlin to Moscow, but that again raises such security and detection issues that it hardly seems possible. (The Harnack/Schulz-Boysen cell of the Rote Kapelle, which did transmit to Moscow, had been discovered in the summer of 1942.) It is true that the Nazis did exploit the Trepper network in Brussels for a while, sending a mixture of false and accurate intelligence back to Moscow in a Funkspiel. It started in December 1942, but sent mostly low-grade information of local interest, and of scant military value, in the months in which it worked through 1943. And above all, why, since the Nazi authorities must have been able to detect the transmissions, did they allow them to continue?

Perhaps readers will understand why Item 13 in my list of conundrums (which I compiled before I finished Kilzer’s book) is so important, but it should probably be restated, probably along the lines of ‘What other channels apart from MI6’s link to the Rote Drei were used to send vital Nazi battle-plan information to Stalin?’

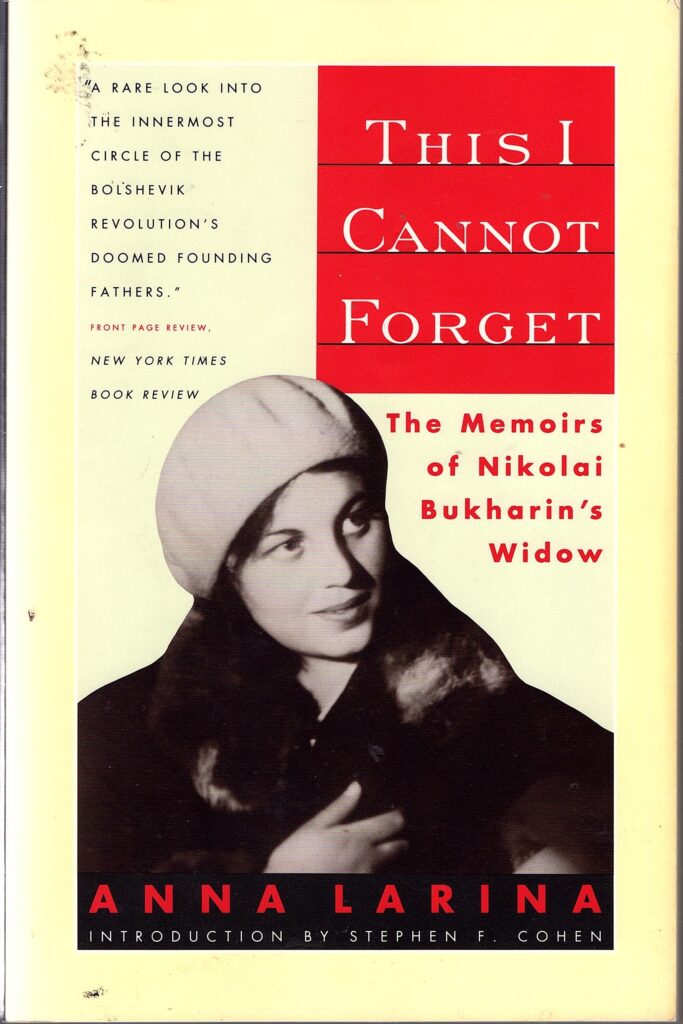

Arthur Crouchley and the Contribution of Memoir

I have occasionally pointed out how enlightening it would be if some previously unknown memoir, or batch of letters, were to surface that might shed light on some of the perplexing events in intelligence and counter-intelligence during the critical mid-twentieth century. Indeed, that resource might be the sole contribution should the absurdly restrictive practices of UK government departments endure. Perhaps David Petrie’s Diaries (which were in fact written, but then destroyed at the author’s bidding, as Christopher Andrew tells us) might magically be found? The trove of letters found at Burgess’s flat after he absconded? Jane Archer’s Diaries? The Aileen Furse-Flora Solomon Letters?

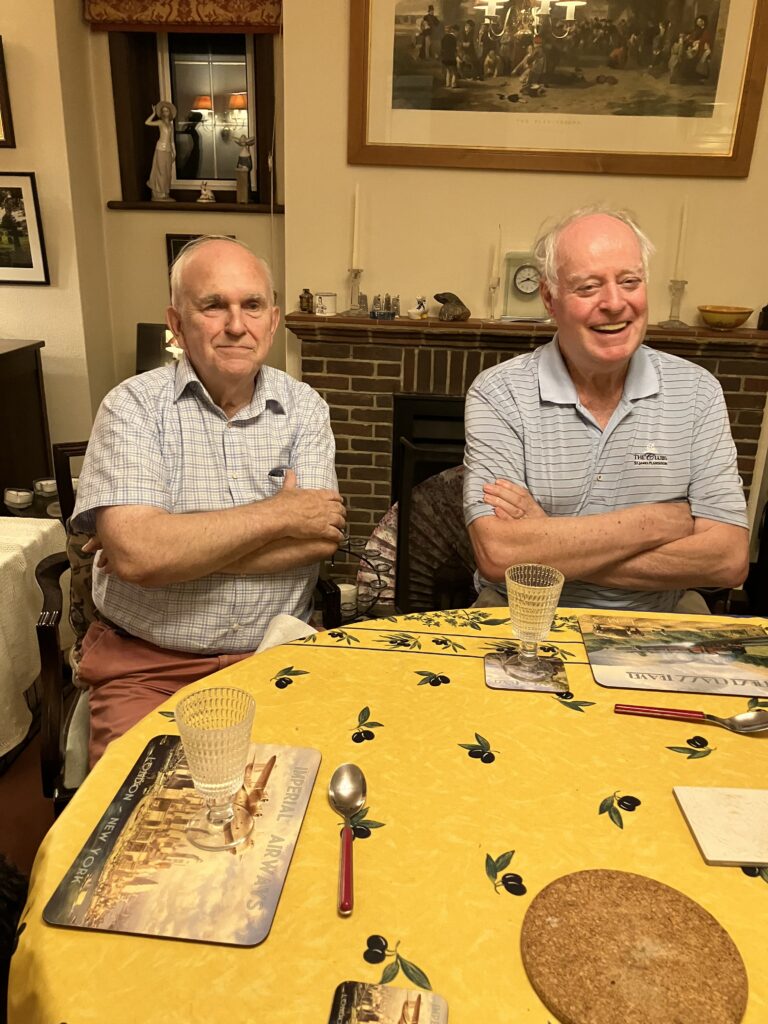

I was thus excited when I met a very spry Anthony Morris, in his nineties, when I gave my talk at Whitgift School. He had come from Nottingham to hear my presentation – his first visit to his old school in sixty years. And he generously showed me some notes that his father-in-law, Arthur Crouchley, C.B.E., had compiled. Crouchley had joined MI6 in 1946, and risen to become Northern Area Controller. I gratefully promised to look into them, and to try to work out to what exactly they referred, and on what they shed light.

There were three passages that caught my interest. The first ran as follows:

The defection to the Soviet Union of Maclean and Burgess in 1951 caused major problems for SIS. The Soviets had changed their codes and moved over to OTPs (One Time Pads) and this had a devastating effect on GCHQ whose reports to us virtually ceased. The fruits of years of work and substantial expenditure vanished almost overnight . . . . The view initially held in the Office about the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean was that they had merely ‘gone on a binge’.

I was puzzled by this statement, as it did not tally with my sense of chronology. I had an exchange with Morris to try to pin down further details, but he sensed that Crouchley, who recorded these reminiscences only in the late 1980s, might have misremembered the events. I believe that there was a lot of disinformation being passed around at this time. I suspect that the information being passed by GCHQ to SIS was in fact VENONA material. When the Burgess/Maclean fiasco occurred, at a high level, I imagine that the cabal of Strang, White, and Menzies decided not to release any more, as it might disclose far more than the senior officers wanted revealed. Crouchley and co. may have been told that it was because the Soviets had changed to OTPs, but that was a fiction. The ‘secret’ of VENONA was that OTPs had already been deployed for well over a decade, but had undergone a challenge in 1942, when, under pressure, the NKVD reused OTPs and distributed them to all dependent stations and sections as new. The Soviets had learned, from Weisband and Philby, of possible breakthroughs in decryption made by GCHQ and NSA, and had, as a response, issued new codebooks and OTPs. The last VENONA decrypts occurred in August 1948, when the Australian Embassy belatedly replaced its OTP. (This is a simplification of a story that needs refining: I expand on it in the following section of this report.)

Thus there was nothing significant, from a cryptological standpoint, about the escape of Burgess and Maclean in May 1951. Of course, it could be posited that Burgess and Maclean took with them intelligence that other codes had been compromised. That seems to be the rationale behind Crouchley’s statement that the defection caused problems, with the drying-up in 1951 closely following the escape, but that hardly makes sense. Burgess and Maclean would not have had access to any such insider information (and I doubt whether Blunt did at that time, six years after he had left MI5). If they had, they could have informed their handlers at the London Embassy at any time before they absconded. The discovery would not have to wait until Burgess and Maclean were debriefed in Moscow. My conclusion is, sadly, that Crouchley and his fellow officers were strung a line. Crouchley does not indicate how long ‘initially’ lasted, but the facts behind the disappearance were clearly withheld from junior offices. His narrative indicates how he was continually misled, and that he, like many other MI6 officers, was convinced of Philby’s innocence right up to his own flight. That was just after Dick White (so Crouchley wrote) informed his team that Nicholas Elliott had been sent out to Turkey to interrogate Philby over a claim that he had tried to recruit a woman in Berlin to the Soviet cause . . . Another falsity, or a fascinating new lead?

I am following up some aspects of these events, since I see many unresolved questions about the nature of any progress made against Soviet traffic after the war, thanks primarily to the vague and unhelpful statements on the subject made by John Ferris in his history of GCHQ.

The second example has some historical significance, and deserves some background information. When Dick White appointed Crouchley to head a new Directorate in 1957, he explained that he wanted to establish a new section in London to gather intelligence about Soviet intentions, since MI6 had no sources inside the Soviet Union. White had picked Crouchley to leapfrog over Peter Lunn and other officers who had been senior to him. In his note, Crouchley explained that such a move might tread on MI5’s toes, writing:

One of my first problems about the London-based station was to clear the position with the head of MI5. This was a tricky one. MI5 held firmly to the view that MI5 had the sole right to operate inside the UK. The division between the two services was, in their view, the simple concept that MI5 operated in the UK and MI6 operated abroad. This was, in fact, an oversimplification. The real division between the two services was, and still is, a division of functions. MI5 was, and is, responsible for security while MI6 was, and is, responsible for intelligence. In its simplest terms it may be said that MI5 was responsible for catching spies working for “enemy” nations while MI6 was responsible for gathering secret intelligence about enemy states, “enemy”, in both cases, having been narrowed down by this time mainly to “Communist”.

The outcome was that Crouchley went to see Hollis to broach this subject, and Hollis was predictably opposed to the idea, stating that the division of labour was clear-cut on geographical grounds. (He had apparently forgotten that MI5 had frequently demanded representation on foreign fields, such as in Europe at the end of the war, and in Washington after that.) Thus Crouchley changed his tack, and reported it as follows:

Seeing that I was getting nowhere I said that I appreciated the point he was making and, to meet it, I said that I was prepared to arrange to keep him fully informed about our operations in this country and about any sources that we might recruit. At once his attitude changed. He no longer opposed. He agreed without further discussion and I left the meeting feeling that I had achieved an important breakthrough.

Crouchley did not read much into that change of heart at the time, but wondered later whether Hollis had suddenly agreed to let MI6 operate so that he could inform his Russian masters as to what was going on. It appeared to confirm what he had been told elsewhere [see below] about Hollis’s treachery.

I find this story absorbing. There is no doubt the encounter happened, but how should it be interpreted? First of all, I can find no other reference to White’s move to set up a domestic espionage operation: Stephen Dorril’s MI6 says nothing about it. In that sense, Crouchley’s insight is a dramatically fresh contribution to the history of the service. White presumably got his way. But what about Hollis? If he really had been a scheming penetration agent, skilled in subterfuge, would he not have simply succumbed to the initiative, and informed his masters about it, so that they could have been forewarned? Instead, he waited until an opportunity came for him to show his true colours, and to express enthusiasm at the prospect of gaining intelligence about émigré anti-Soviets that he could pass on. In that way he drew attention to himself. It is the old Pincheresque paradox: if Hollis let his guard slip, he was guilty. If he didn’t, it was because of his unmatched cunning.

I looked at it from another angle – that of management technique. If I had been in White’s shoes, I would have discussed this beforehand with Hollis (who, after all, had been White’s protégé), so that he would not have been surprised by Crouchley’s approach. It is possible that Crouchley was sent out to see Hollis in some kind of ability test, to see how he responded to Hollis’s planned resistance to the idea, and that Hollis then played his part in the charade. But maybe not. White may not have been that subtle. Yet, if he had really been determined to set up the new unit and it sounds as if he was), sending in a relatively inexperienced officer to break the news was not the surest of steps. Again, an enticing, but not very clear-cut, incident.

The third story relates to Roger Hollis and a nuclear scientist, in an event that Crouchley called to mind after he read Spycatcher in 1987. Crouchley recalls what he had been told in 1957 by two MI5 officers at a joint seminar on Russia at Magdalen College, Oxford.

There was no question in the minds of my MI5 colleagues (I forget their names) that Hollis was a spy. But they were bitter in their complaints of his direction. They were a very angry about a recent case where, as a result of Hollis’s orders to them, a nuclear scientist from Cambridge, whom they knew to have been in contact with the Russians, had been allowed to leave England and go to Italy to take up an appointment at a University there, taking with him a whole pantechnicon full of his papers and possessions. The scientist (I forget his name – I have in mind that he had a Jewish name like Chaim (?)) had been under observation by MI5 for some time and was known by them to be in contact with Russian agents. Then he obtained a position as Professor in a University in Italy. The MI5 officers wanted to move against the Professor but Hollis would not allow them to take any action.

Again, this is a fascinating anecdote that contains a measure of verifiable fact with anomalous detail. It is shame that Crouchley could not recall the names of the officers who, in the first year of Hollis’s tenure as Director General, deemed him a spy. (It occurs to me that the number of officers in MI5 who judged Hollis guilty were always outnumbered by those in MI6 who considered Philby innocent.) Readers of my recent investigation into Borodin will be familiar with the story of Ernst Chain, a biologist, not a nuclear scientist, who had indeed been in contact with the Russians, and did absquatulate to Italy to take up a Professorship for a number of years. Yet it all happened in 1948 – which was hardly ‘recently’. In any case, Hollis would not have then been in a position of authority to issue such orders. He had only that year been appointed head of C Division, and he was consumed with VENONA and Australian business. On the other hand, it seems very early for junior officers to harbour suspicions that Hollis was a spy. This was well before Golitsyn, and I have heard of no other evidence outside this bizarre case that would appear to incriminate him, or even to suggest that MI5 was protecting a spy.

Crouchley’s story contains some realistic-sounding details about the two officers having to safeguard the pantechnicon taking the scientist’s effects, all the way to Dover, to ensure that the Professor departed safely. While that might be considered an unlikely use of senior officers’ time, it also seems an unnecessarily flamboyant way for Hollis to draw attention to the fact that he was abetting a probable Soviet agent. Was the story a mingling of the cases of Chain and Pontecorvo, perhaps, since Pontecorvo was an Italian? Yet Pontecorvo defected in 1950, he did not work at Cambridge, and his escape did not involve a security detail on the road to Dover. The reference to ‘Chaim’ would appear to be the clincher, unless there existed a further atom spy who otherwise fitted the description. But what were those two MI5 officers up to telling Crouchley the story, and how come it has not – so far as I know – appeared anywhere else?

I do not doubt Crouchley’s integrity for one second, but these anecdotes prove how unreliable memory is. I think of all those biographies that rely largely on testimony from those who were around at the time, and whose confidence to the author are used to shed light on what Blunt, or Burgess, or anyone else, was up to at the time, and their thoughts are solemnly entered in the record.

VENONA: When did the Soviets Rumble It?

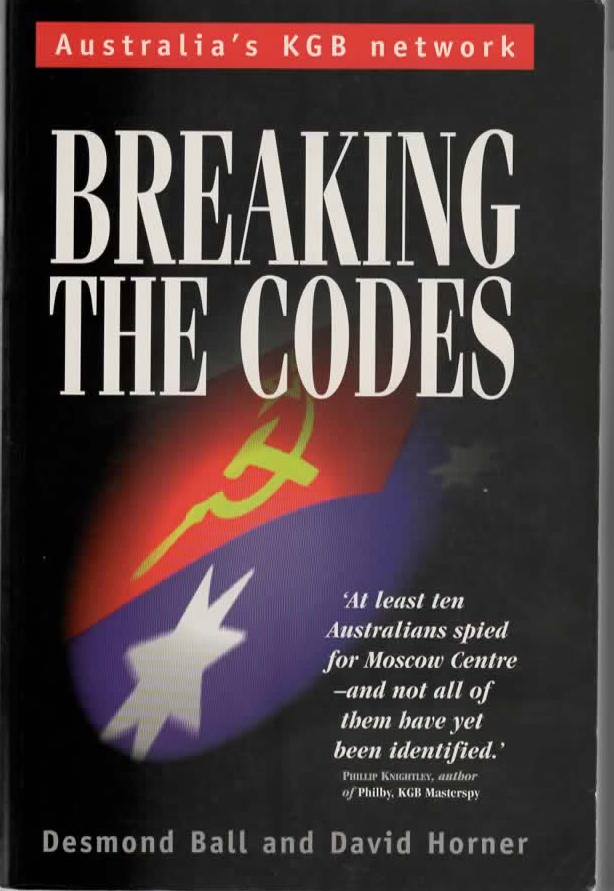

I was intending to write about VENONA this month when I was further motivated by a gobbet of intelligence on the Australia dimension of the project that fell into my lap. I had been ruminating over the fact that Richard Aldrich (in GCHQ) had quoted Ball and Horner (Breaking the Codes) as claiming that GCHQ had been decrypting NKGB Canberra-Moscow traffic in 1948 ‘almost in real time’. Several years ago, I had taken notes on the Ball and Horner book (published in 1998), which confirmed Aldrich’s claim. That seemed an extraordinary achievement, with many implications, and the fresh news shed some dramatic new light on the affair. I cannot tell the full story of the serendipitous revelation, but let’s just say that a joint NSA-GCHQ exercise resulted in the institutions’ deciding that I should be the beneficiary of their industry in intercepting some recent international email exchanges. We’ll leave it at that, shall we?

I intend to explore some of the puzzles of the VENONA project more fully in a later bulletin, but I wanted to lay out an idea here, in the hope of receiving feedback. As a reminder, VENONA was the decryption project carried out by US Army Signal Security Agency (SSA) and GCHQ analysts, starting in the late nineteen-forties, and continuing occasionally until 1980. It exploited careless procedures by the management of the GRU and the KGB [a useful generic term for the various guises in which Soviet foreign counter-intelligence took shape from the thirties until the eighties], notably the re-use of One-Time Pads (OTPs). Such devices, by their definition, should never be re-used if message security is to be maintained, but violations of procedure enabled MI5 and the FBI to identify many Soviet agents, including Klaus Fuchs and Donald Maclean. The coded names of that pair appeared in message traffic, and their identity was confirmed by factual details concerning their lives and movements.

One aspect that has always intrigued me is the question of when the Soviets realized how they had slipped up. It is important, first, to describe the three-way process by which messages were converted from Russian text (and words in English) into meaningless numerics. Agents and important figures (such as Roosevelt and Churchill) were given codenames, to start with – in the case of those two, KAPITAN and BOAR, respectively. (Even when great strides had been made in the decryption process, the anonymity of the subjects discussed caused problems in identifying agents until the NSA, the successor to the SSA, invoked the help of the FBI.) The next step was that as much of the text as possible would be replaced by 4-digit codes derived from a code-book, a kind of dictionary with a single entry for common terms used in intelligence traffic. If a word was not in the codebook, it could be represented by a look-up of entries for letters that were also in the book, multiple items sometimes being available for a single letter, with the exception routine being signalled by an ‘escape’ character sequence. The resulting string was then processed by a unique key taken from the OTP, a book of randomized numbers. The intermediate streams were treated by logically adding to the generated text the keys on a particular page of the pad, the existence of which was known only by the sender and the receiver, and kept under tight security. (Sometimes a further numeric-alphabetic translation occurred.) When the exercise was completed, the relevant page would be destroyed.

This system appeared to be watertight. OTPs were almost impossible to decipher without a lot of help – for the most part ‘cribs’, that is full plaintexts of messages sent, for instance the reproduction of stolen documents in their entirety, that could be compared with their encrypted correspondents. Such an exercise might help with the process of constructing the lexicon or codebook, which allowed the numbers to be translated back to intelligible language. The Soviets were quite confident about the security of the system, therefore. Even if a codebook were found or stolen, the security of the OTP should have protected the confidentiality of the traffic. Yet the Russians appeared very nervous about the integrity of the codebook. When rumours started reaching them, initially from Lauchlin Currie in 1944, that inroads were being made on their messages by the USA’s decryption experts, their first instinct was to change the codebook, even though a new codebook would also be subject to the rigours of the OTP system. Their failure to inspect the OTP system itself suggests that at that time they did not suspect any flaws in those procedures.

Even if they had suspected a problem with OTPs, however, they might have issued new codebooks, as a more rapid response, even though it would have been a nuisance, and require a period of familiarization in all the embassies. (And there might have been problems in wartime distributing such around the globe, so the process might have been slow.) Yet the more certain they had been about an OTP exposure, the more swiftly they should have reacted, even curtailing message transmission and using diplomatic bag facilities instead, or insisting on more cryptic expression of essential information. In that event new OTPs should have been created, and distributed urgently to all Embassies. The process of creating new OTPs, with proper random-number generation, and packaging them into separate OTPs for the five major lines of embassy traffic would have been even slower and more complicated than creating new codebooks, but it would have been an essential step.

Yet the Soviets did not do that, not even when their agent William Weisband in 1946 started getting close wind of what the Americans had achieved. (According to Weinstein and Vassiliev, he did not make contact with the NKGB until 1948.) That may have been partly due to the fact that most OTPs had been replaced by then. The truth was that the stock of OTPs ran out at different speeds in each station, depending on the volume of traffic. A station like Washington or New York would probably have been refreshed in 1945, before the bulk of the traffic from 1944 was analyzed and decrypted in the 1946-1948 timeframe. Thus it is quite possible that the Soviets were slow in realizing what had happened in 1942, when, under pressure from the Nazi invasion, and the movement of government offices from Moscow to Kuibyshev, a large set of OTP pages had been duplicated, and inserted into the various OTPs to be used. That drastic error was why the VENONA project enjoyed its narrow, but deep, success. And, if Moscow concluded that all the exposed OTPs had been replaced by 1945, they might have dropped their guard.

There was an outlier, however – Australia. The Canberra-Moscow link was one of the most revealing, definitely the most enduring, and surely the most overlooked channel. As I cited above, in 1948, GCHQ was ‘virtually reading the messages in real time’. When Weisband drew his bosses’ attention to continuing successes by GCHQ and NSA in early 1948, he probably identified a critical message that had been passed two years earlier, when a UK Post-Hostilities Paper was encrypted word for word, and transmitted to Moscow for reasons of urgency. That act must have provided an invaluable crib for the Western cryptanalysts. Yet by then MI5 was concerned about the leaks from Australia, especially since Woomera had been nominated as a guided weapons testing range. At the end of 1947, Prime Minister Attlee had to inform U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall of a possible exposure, and the necessity of re-considering Australia’s access to intelligence coming from BRUSA, the British-American Agreement. The Americans threatened to cut Australia out of any intelligence-sharing.

The immediate outcome was that the Director General of MI5, Percy Sillitoe, accompanied by Roger Hollis, was dispatched to Australia in February 1948 to investigate the leakages, and recommend solutions. To protect the VENONA source, they brought a cover story about a defector’s providing them with information about the critical Planning Document. Yet they immediately faced a dilemma: whom could they trust to ask questions about who had had access to such confidential documents? Sir Fredrick Shedden, Minister of Defence, helped identify candidates for interview. Inevitably, out of clumsiness and inexperience (Sillitoe was still a policeman at heart, and Hollis was not the sharpest counter-intelligence officer), some of the real spies and fellow-travellers were interviewed. As Weisband started to bring fresh insights, alarm bells began to ring in the Soviet embassy as they learned more about their codes having been compromised.

At this stage, in April 1948, the messages between Makarov, the NKGB rezident, and the head of the cypher group in Moscow, were still being intercepted and decrypted. London and Washington thus had a partial idea of what was being discussed, although some of the opposition’s messages must have passed by diplomatic bag, causing a delay. Some analysts have asserted that it was only then that Moscow concluded that some OTP keys had been compromised, and that it could have happened only through duplicated pages. On June 2, Moscow cabled Makarov to remind him that new books of OTP keys had been sent out to him that January, which implied that he should change the cypher immediately. The last message decrypted in the VENONA project was a cable sent three days later.

So what was going on here? Why, when Moscow sent out fresh OTPs in January, did it not insist that the new keys be used immediately? Why would it have assumed that Australia was somehow not affected by the exposures that had affected other locations, as Currie, Philby and (maybe) Weisband had already warned? Did they perhaps think that Australia was so geographically removed so as not to come under GB or USA surveillance? Were they perhaps not tracking exhaustion of OTPs, and did they not realize that Australia had not been refreshed for some years, unlike, say, London or Washington? Was it the factor of the inquiries made by Shedden that truly made them conclude, so late in the day, that duplicated OTPs had caused the exposure?

I then went back to Breaking the Codes, and re-read the chapters on VENONA (which I should have done at the outset). It is a useful book, with many valuable references, although the authors trust Chapman Pincher too much. I found the passage concerning ‘real time’, but, to my surprise, also a statement that, in June 1948, ‘the Residency in Canberra used up the last of the duplicated OTP pages’ (p 199). This comment was made without any note of astonishment or inquisition. The source for both claims appeared to be an item titled The KGB and the GRU in Europe, South America and Australia, Venona Historical Monograph No. 5, issued by the NSA in October 1996.

With the help of an on-line colleague I found the email address of Professor Horner, and sent him a message asking whether he could shed further light on these assertions. To my delight, he responded almost immediately, although he was on a cruise, informing me, however, that the relevant chapters had been written by his co-author, Professor Desmond Ball, who had since died. Horner was unfamiliar with the research behind them. (The perils of co-authorship!) But he promised that he would look into it when he came back to Australian shores. While we were communicating I did manage to track down that Monograph No. 5. Indeed, it does make the claim about ‘real-time’, as follows; “Unlike any other group of VENONA messages, some KGB messages on the Canberra-Moscow communications link were decrypted in near real-time, that is, close to the date of transmission.” Very well, not quite my idea of ‘real-time’, but close enough for government work, as they say. Yet the paragraph on Australia says nothing about the continued use of faulty OTPs enduring until the middle of 1948. Was that just an incidental remark by Ball, or did he pick it up from one of the many interviews and items of correspondence that the authors record in their Bibliography?

Another puzzle is the trove of Canberra cables. On pages 204 and 207 Ball and Horner display prominently two important Canberra-Moscow cables, from March 1946 and June 1948, but do not indicate where they are stored, or if they are available for inspection. When the major VENONA announcement was made, in 1996, the NSA stated that ‘all the VENONA translations – roughly 2,900 KGB, GRU, and GRU-Naval messages – are being released to the public’, and it issued the url to access them, namely www.nsa.gov:8080\. That url is no longer active. I could not find them on the new, appallingly designed NSA website ( https://www.nsa.gov/Helpful-Links/NSA-FOIA/Declassification-Transparency-Initiatives/Historical-Releases/Venona/ , where 100 pages of cables from around the world are listed, apparently randomly, totalling about 1500 cables only. The ‘Search’ facility does not work properly. What happened? My other source, the Wilson Center, is better organized, but does not show anything like the number of ‘over 200’ Australian cables that Monograph No. 5 claims were usefully decrypted. So where are they, and how are my unknown contacts managing to process them? All this secrecy over something that is as old as I am – why? (I have since been able to locate that particular message through the help of VENONA expert John L. Haynes, who shares my frustrations with the antics of the NSA. He kindly supplied me with a full set of the decrypted Canberra-Moscow traffic.)

And the bizarre behaviour of Moscow remains uninspected. I find it incredible that, given the sensitivity and high exposure of flawed keys, and the information about the VENONA project that, if it had already considered duplicate OTPs a problem, Moscow would not have intervened aggressively in the exchanges with Canberra in 1948, as it would have demanded abandonment of the current pads. In a famous report from London to Moscow in 1950, Kim Philby reported on the success the Americans and the British were having, and he identified as the prime reason for their breakthroughs ‘a one-time pad used twice’. This must have been intelligence that he picked up in his role as MI6 liaison officer in Washington, and passed on to Modin in the spring of 1950.* Was that the first inkling that Moscow had about the exact nature of the problem? I have seen no evidence that places it any earlier.

Yet the final conundrum is the relationship of all this to what has been dubbed ‘Black Friday’, that day late in October 1948 when the Soviets reportedly changed all their codes, and thus made further decryption impossible. Even if they did not know where they had failed, they had to make some drastic changes. I do not understand this. All the traffic from the non-Australian circuits was already unreadable since the replacement of OTPs in 1945, and the NSA was not able to make any further advances in decades, so we are told. Thus the overdue replacement of the Canberra-Moscow OTPs might simply have represented the last correction that Moscow needed to make. Did NSA somehow not want to admit that, and instead to blame Weisband and Philby for revealing (almost) all, blowing up the event into some major move by the NKGB? Moreover, none of the famous cribs would have been available, and the uncovering of the KLOD (CLAUDE) network, and the extended investigation that led to the setting-up of ASIO, would not have happened if Moscow had simply ordered Canberra to switch to a new OTP in 1945.

As Stephen Budiansky informs us in Code Warriors, there was much more to Black Friday than diplomatic and intelligence traffic, namely the wholesale reworking of the Soviet Union’s military and police systems, which constituted a huge blow to the decryption efforts of the USA. Yet he implies that the NSA ascribed the comprehensive changes to Weisband’s leaks, which would suggest that Moscow experienced a dramatic reaction only when it discovered that Canberra had been an exposure for three years longer than necessary, and that the Soviets thus went into overdrive at a time when the Cold War was considerably heating up. I am not absolutely sure that I am on the right lines here, but I intend to study the problem in full in the spring.

[* According to Liddell’s diary, Philby had returned to London in March 1950 for a while, having been called back by MI6 to discuss the Fuchs affair (see West’s and Tsarev’s Crown Jewels, p 181). That visit must therefore have been the occasion on which he passed on his intelligence to Modin. In Venona, Haynes and Klehr, citing The Crown Jewels, represent Modin’s report as being sent in February 1950, but that must be a misreading. The Crown Jewels suggests that Burgess failed to turn up for a meeting with Modin on March 20, using as an excuse Philby’s summons and presence in London, and Modin’s ‘lengthy’ report on the crisis was probably sent in late April, by courier, not by cipher.]

The Mysterious Other Leggett

In an earlier Annotation on coldspur I had drawn attention to a probable anomaly in my descriptions of a certain George Leggett who worked for MI5. When I was writing about Brian Simon and Peter Astbury last August, I had referred to a note by G. H. Leggett (B1F) about Leo Long, when Leggett, in late 1952, was making inquiries about Communists at Cambridge in the 1930s. I added a paragraph about Leggett, which I reproduce here for convenience:

Likewise, you will find no mention of ‘George Leggett’ in Andrew’s Index. This is quite astonishing, as he was a significant but controversial figure. He was indeed in charge of B1F in 1952, and had been carrying out a study of Cambridge academics with baleful influences at the time. (When Thistlethwaite had moved on, and whereto, are unclear: he must have still been in MI5, since he lectured to outsiders as an expert on Communism. Liddell reported that he received a promotion in April 1953.) The Maurice Dobb PF (specifically sn. 133a in KV 2/1759) shows that Leggett was investigating both Dobb and Piero Sraffa in the autumn of 1952. Leggett (who was half-Polish) joined MI5 during World War II (according to Nigel West’s Historical Dictionary of British Intelligence) and ‘spent most of his career studying Soviet intelligence organizations and their operations’. If that is true, it is remarkable that his researches are not more prominent. According to Trevor Barnes, Leggett is the figure behind the pseudonym of ‘Gregory Stevens’ in Spycatcher (pp 320-324), a character of somewhat dubious credentials who had run the old Polish section of MI5, and held on his résumé the assistance to Stalin on translations at Yalta, as well as having relatives in the Polish Communist Party in London. He was forced to resign in the wake of the Golitsyn revelations after Wright accused him of being the ‘middle-grade’ spy called out by the defector. A letter in Burgess’s PF (sn.737b in KV 2/4115) shows that Leggett had been MI5’s Security Liaison Officer in Canberra in June 1956. According to Adam Sisman, he had also been responsible for recruiting David Cornwell (aka John le Carré) to MI5.

I went on, however, to report that Guy Liddell had also been dealing with Leggett back in 1940, and that he and Roger Hollis had gone to consult Leggett for advice on what should be done with Communists in industry. I believe the first mention of Leggett is on February 20, 1940, when Liddell reports that Hollis went to see him about the question of interning members of the Communist Party. I had blithely assumed that it must be the same Leggett, as they were both some kind of expert on Communists, although the fact that Liddell and Hollis went to ‘consult’ him in May suggested that he was perhaps part of the Legal team. (In April, Leggett had written a letter to the Home Secretary, Maxwell, which would tend to reinforce that interpretation.) That Leggett also had to give some sort of approval to recommendations that Hollis put forward concerning cracking down on Communist would tend to support that notion. Unfortunately, Liddell does not offer any initials or first name for this individual.

And then a long-standing coldspur enthusiast sent me details of G. H. Leggett’s biography (facts that I could have divined myself, had I been enterprising enough). First, he introduced me to a seminal work on the Cheka that Leggett had published in 1981 (see https://dn790007.ca.archive.org/0/items/george-leggett-the-cheka-lenins-political-police-claredon-press-1981/George%20Leggett%20-%20The%20Cheka_%20Lenin’s%20Political%20Police-Claredon%20Press%20%281981%29.pdf) He retrieved a few other valuable items, including the assistance that Leggett gave to the Petrovs in Australia, and, most importantly, he provided some facts about Leggett’s life, such as a pointer to his archive at the Churchill College Archives at Cambridge University (see

https://archivesearch.lib.cam.ac.uk/repositories/9/resources/1686). From this we can learn that George Leggett was born in Warsaw in 1921, the son of Norman John Francis Leggett and Halina née Tuczyn. Other evidence indicates that he was not recruited by MI5 until after WWII, which makes sense, given his age. (I notice that he was educated at St Cyprian’s, the notorious institution attended by George Orwell and Cyril Connolly.)

So he could not have been the same person as the 1940 Leggett, as he would have been only nineteen at the time. I took a look at ancestry.com. Passenger Lists show that Leggett (‘Vice-consul’) arrived in London from Japan on August 15, 1920, aged 29, with his wife, Halina, aged 26, and that their country of last permanent residence was, somewhat alarmingly, given as ‘Siberia’. It seems unlikely that George was born in Warsaw in 1921, therefore. The 1901 Census tells us that Norman, who had been born in Camberwell, London in 1892 (about), lived with his mother and father in Bermondsey. He had a brother, Harry W Leggett, so, if the 1940 Leggett was a relative, he was quite a distant one. Norman died on May 27, 1971. Yet the records for George Leggett show something remarkable: he was born, not in Poland, but in Warsaw, Kosciusko, Indiana, USA (!), on September 25, 1921. George married Rani P D E Birch: she died the same year as George’s mother, in 1983. But the family tree on ancestry.com simply states ‘Warsaw’ as George’s birthplace. He died on May 1, 2012.