Before I present this month’s main course, on George Graham, I want to comment on a few other items:

When I published the 2021 Year-end Round-up last month, I was either tempting fate, or articulating a very sensible long-term strategy. Three days afterwards, on January 3, I suffered a heart attack, was rushed to hospital (after which I lay in a corridor for four hours), and the next day was moved to another hospital where I had a stent inserted in the artery that had undergone the big blockage. I was discharged on January 5, at mid-day, but was back in the Emergency Room at 1:30 the next morning, suffering from fever, wheezing, and chronic shortage of breath. I imagined such symptoms might be what serious COVID patients experienced, but I was fully vaccinated, and had had a negative test the day before. It turned out that I had pulmonary edema, a build-up of fluid in the lungs, caused by the somewhat erratic behaviour of the heart trying to re-adjust the system after the assault. Oxygen pumps and powerful diuretics soon stabilized me. I was discharged four days later.

In order to explain my lethargy in concurrent email exchanges, I have described the events to those of my communicants with whom I was in active contact at the time, but thought that I should post a notice here, even if it will be Too Much Information for many, and there is nothing more boring than an Old Fogey rabbiting on about his medical problems. I expect this event will mean some operational changes (although I have been very attentive to diet in the past few years). My heart is, fortunately, overall in good health – and has always been in the right place, of course – and I do not believe the pace of my research activities will have to be slowed down at all. Indeed, I should have more time available for cerebral pursuits since such activities as tree-felling, bush-hogging and yard work will clearly be proscribed by the doctor. No more for me the Reaganite removal of brush and repairing of boundary fences on the ranch. I most cordially thank all of you who have passed on your messages of goodwill.

With a new regimen of medicines to be taken, I told my wife that I felt like one of those old persons who cannot read the small print on the vials, and have to have instructions laid out to be sure of taking the correct purple oblong pill after breakfast. I now realize that I am officially one of those persons.

When I was discharged, I was earnestly encouraged to sign up for a Cardio Rehab course in a week or two, to handle with my fellow-sufferers such items as appropriate exercise and strategies for handling stress. I am very wary of such collegial activities: you will not see me standing in a pool with other rehabilitants, waving my hands in the air. I know best, because of the scar tissue from multiple back surgeries, and resultant neuropathy, what exercise I must avoid in order not to irritate further the heel (where the stabbing occurs). Moreover, several sessions on stress avoidance will be offered. Yet there has been no stress in my life in recent years (apart from the tribulations of dealing with local service contractors of any kind, and reading laudatory reviews of Agent Sonya), and nothing would be more stressful to me than having to listen to a lecture on ‘Mindfulness’ when I could be spending my time more fruitfully among the archives.

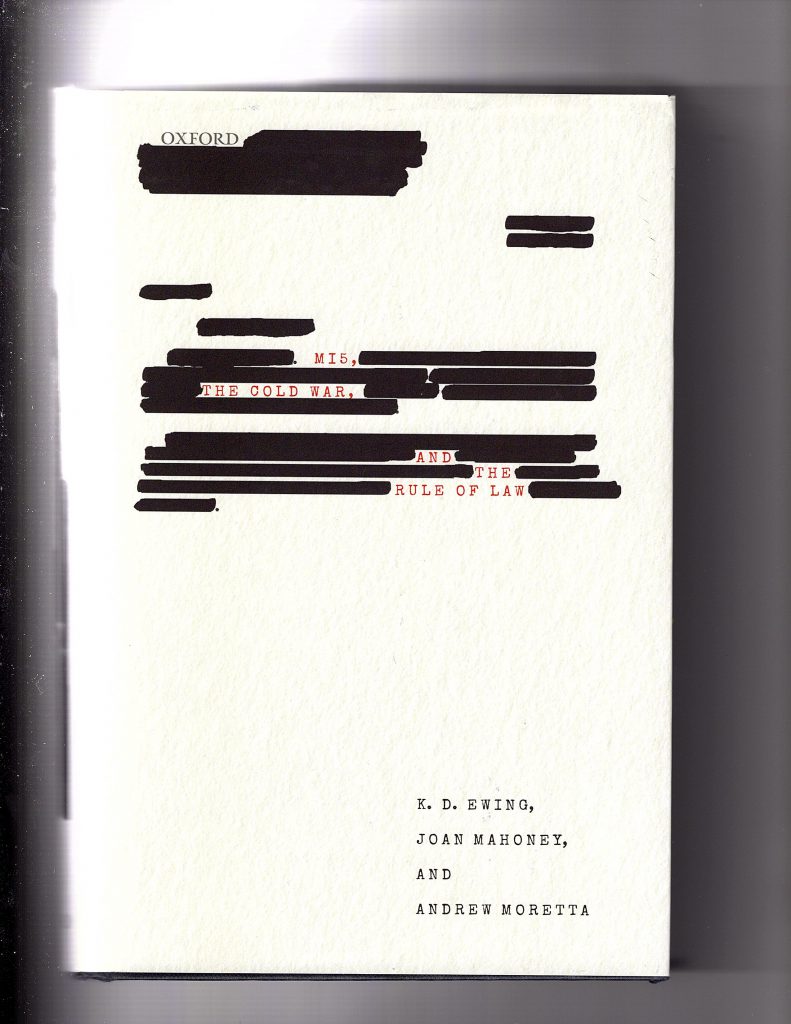

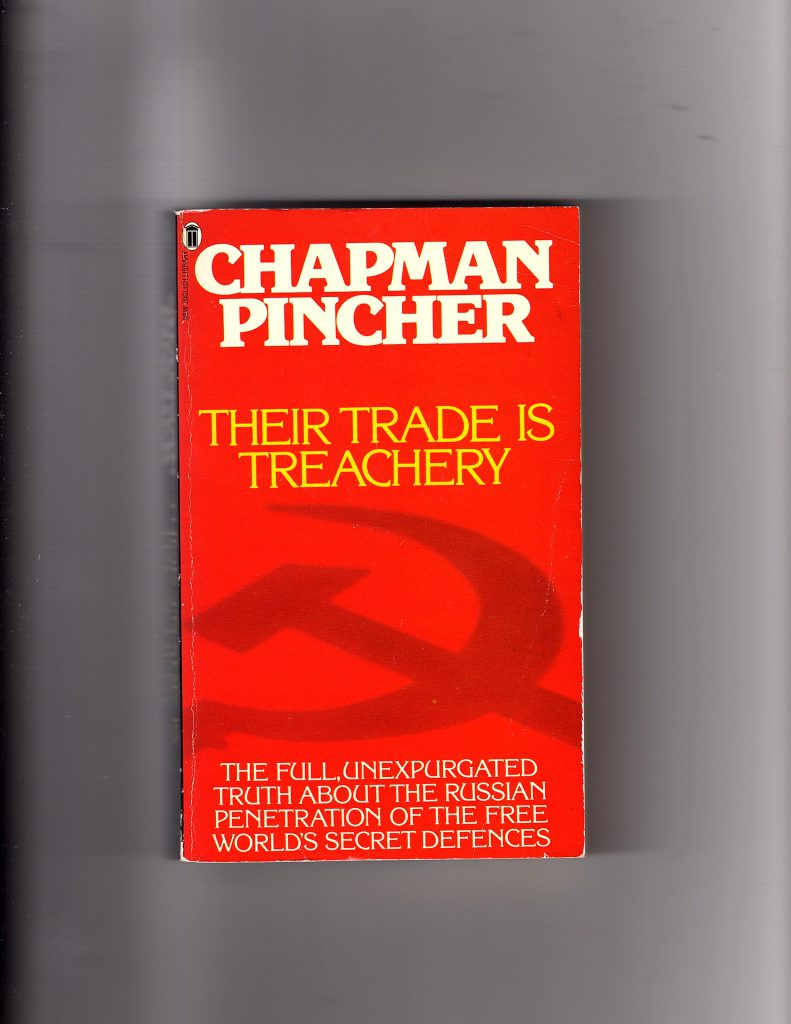

Thus it was with some chagrin that, when I picked up my copy of the January 6 issue of London Review of Books on my return home, I found a review of Ben Macintyre’s Agent Sonya by someone called Malcom Gaskill, described as an ‘emeritus professor at UEA’. His webpage at the University of East Anglia records the following as his ‘Areas of Expertise’: “Social and cultural history of Britain and America 1550-1750; history of crime, witchcraft, magic and spiritualism.” So one might naturally wonder why he was selected to review the book, so late in the day, unless he had some alarming new theory about Sonya’s dabbling in the black arts, or the story of her reincarnation. I accordingly wrote a letter to the Editor, as follows:

I was both astonished and dismayed by Malcolm Gaskill’s review of Ben Macintyre’s ‘Agent Sonya’ in the LRB (January 6). Astonished, since, while your description informs us that the book was published in September 2021, it was actually issued a year beforehand. It is difficult for me to imagine how you judged that a review after all that time was justified. Dismayed, since Gaskill, while producing a very competent and readable synopsis of Macintyre’s work, appears to bring no external knowledge or expertise to his analysis, and has been taken in by many of Macintyre’s fictions in the same way that Macintyre was hoodwinked by Ursula Kuczynski’s GRU-driven memoir, and his conversations with her offspring.

I have a special interest in a corrective to the mostly laudatory reviews of the book, and my review of it appeared in the on-line version of The Journal of Intelligence and National Security as far back as December 2020, under the title of ‘Courier, Traitor, Bigamist, Fabulist: Behind the Mythology of a Superspy’. (Please see: https://coldspur.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Courier-traitor-bigamist-fabulist-behind-the-mythology-of-a-superspy.pdf ) I have received multiple congratulatory messages on this piece, thanking me for setting the record straight, and for pointing out Macintyre’s errors and flights of fancy. I am surprised that Professor Gaskill did not come across it in his researches – or, if he did, why he ignored its conclusions.

Professor Gaskill touches lightly on the major enigma of Sonya when he writes: “A puzzle emerges from Macintyre’s telling of Kuczynski’s life: how did she not get caught?” Yet a predecessor question, just as important, would be: “Why did MI6 facilitate a bigamous marriage for Sonya, a known Communist subversive, in Switzerland, and then facilitate her passage to the United Kingdom at a time when the Soviet Union was in a pact with Nazi Germany, and providing materiel to support the German war effort against Great Britain?” I would refer your readers to my observations, and the sources listed in my review, so that they may learn about the machinations of Claude Dansey and other MI6 officers, abetted by their counterparts in MI5, to deceive lower-level counter-espionage officers in MI5, such as Milicent Bagot, and deter them from doing their job.

I would be the first to praise Ben Macintyre’s superb story-telling expertise, but would challenge his boasts of commitment to factual history-telling (as expressed in conversations with John le Carré before the latter’s death). The bare bones of Sonya’s life and career are no doubt true, but Macintyre has greatly exaggerated her role as a ‘spy’, misrepresented her ability to escape detection, and studiously ignored the evidence of collusion by British Intelligence over her survival. Bland and uninformed reviews by such as Professor Gaskill sadly reinforce the mythology instead of taking a critical eye to one of the most astounding mis-steps by British Intelligence in World War II.

To my letter I attached a postscript – not intended for publication, which ran as follows:

I attach a highly relevant letter that I sent to Mary-Kay Wilmers a few months before Macintyre’s book was published. I never received any acknowledgment or reply. The London Review of Books could have accomplished a scoop of considerable proportions.

And here is the text of this earlier letter, sent on April 9, 2020:

Dear Ms. Wilmers,

I should like you to consider an article for publication. I am approaching you, exclusively, since I believe that you may have a personal interest in the story, that the LRB is the best vehicle for getting a piece like this out quickly, and that it would be of compelling interest to your readers.

In essence, it a scoop about a woman who has been called the ‘greatest woman spy in the twentieth century’, Ursula Hamburger/Beurton, née Kuczynski, aka ‘Sonia’ (or ‘Sonya’). Ben MacIntyre will be publishing his book on her in September of this year. MacIntyre claims access to privileged sources in Russia, Germany and the UK, but I strongly doubt whether he has investigated her life with the depth that I have.

I gained my doctorate in Security and Intelligence Studies at the University of Buckingham in 2015, and my book based on it, Misdefending the Realm, was published in 2017. Since then, I have been delivering further research on Sonia on my personal website, www.coldspur.com.

My main claim is that SIS (MI6) tried, with the connivance of MI5’s senior management, to manipulate Sonia in World War II. It facilitated her marriage to Len Beurton in Switzerland in 1940, an event that allowed her to gain a British passport, and then contributed to her safe passage to Britain. This was presumably an attempt to get Sonia to lead them to her networks, to pass disinformation through her, and to gain access to Soviet codes and ciphers. When Len Beurton, who was a communist and had fought with the International Brigades in Spain, was also aided in getting to Britain through a faked passport in the summer of 1942, MI5’s anticommunist section woke up, but was essentially stifled.

Yet the exercise went horribly wrong when Sonia managed to act as courier for Klaus Fuchs and Melita Norwood, right under the noses of SIS and MI5, while her husband, Len, transmitted clandestinely on her behalf. The intelligence services have never been able to admit their mistake.

What makes this story especially newsworthy is the analysis of an overlooked document in the Kuczysnki/Beurton files at Kew. It is a letter from Victor Farrell, the Passport Control Officer in Geneva, to Len Beurton, written as if from a private address. It offers incontrovertible proof that, early in 1943, SIS in Switzerland tried to encourage the communist Len Beurton to communicate with them by wireless, betraying that they had some kind of agreement with him. Beurton would inevitably have passed that information on to his wife, Sonia. Thus she would have known for certain that SIS and MI5 were surveilling her.

I attach the version of the story that I have been preparing for my website. As you will see, it is a work in process, and continually evolving. It assumes readers will be familiar with my earlier research, and I look to them to provide information and tips. I know the piece would require some fundamental rework for publication as an LRB article, to set the context properly, remove detailed comments, and provide a more definitive conclusion. I can do that quickly. The main story is very solid.

I do ask you to read at least the introductory few paragraphs, and the latter sections headlined ‘Analysis’ and ‘Conclusions’. Please let me know if this sparks your interest in publishing a revision of the piece. And, if you decide that it is not suitable, I shall simply proceed with posting it on my own website.

If you need to have a second opinion, my doctoral supervisor, Emeritus Professor Anthony Glees, is very supportive of my research and findings, and has agreed to act as a reference. He can be contacted at xxxxxx@xxxxxx.

Thank you for reading this far.

The very next day, I received an email from the Editor, saying that they were considering my letter for publication (as well they should have). Yet it did not appear in the issue of January 27. Maybe there is a natural delay. Maybe Mary-Kay Wilmers (who retired last year, but is still around as ‘consultant editor’) would prefer the story to be buried. I shall keep an eye out for the next issue. If nothing appears, it is not exactly censorship, but it is irresponsible. The guardians of officialdom (Ben Macintyre at the Times, Mark Seaman and Nigel Perrin at the Times Literary Supplement, and Mary-Kay Wilmers at London Review of Books) keep the contrarians at bay. I am not saying that they are acting conspiratorially, of course. It just looks like it.

* * * * * * * *

And now to this month’s main story:

The Strange Life of George Graham

1. Introduction

2. Leontievs in exile

3. Alexander Shidlovsky

4. Paul Dukes

5. Nadine Nikolaeva-Legat

6. Dukes in the 1930s

7. WWII – Dealing with the NKVD

8. George Graham – marriage and SOE

9. Post-War Tragedy

10. Summing-Up

*

- Introduction:

For someone of my generation, the name ‘George Graham’ summons up the rather lugubrious figure of the Arsenal football player, and later manager, perhaps accompanied by grainy video of Chelsea’s Ron ‘Chopper’ Harris taking down Graham’s team-mate Charlie George on the edge of the penalty-box. ‘George Graham’ is a decidedly Scottish appellation, neither common nor rare, and has a pleasing solidity to it. At some time, however, this same moniker was chosen to signal the new identity of one Serge Leontiev, a Russian émigré who was recruited for a dangerous mission with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) in Moscow in 1941. This report outlines what I have so far been able to discover about his life, and explores how a callow and inexperienced young man was carelessly plunged into the cauldron of espionage on Stalin’s home turf.

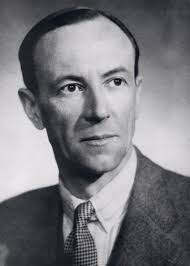

I reproduce first the brief snippet from Guy Liddell’s Diaries that brought my attention to him. The entry occurs soon after the defection of the Soviet cipher-clerk Igor Gouzenko in Canada in September 1945. After receiving hints about a possible spy named ELLI, Liddell started to investigate possible security leakages in the Moscow SOE station, led by George Hill. He had a meeting with Alexander Boyle, the chief security office for SOE (the wartime sabotage unit which would shortly be disbanded and absorbed into MI6). The date is November 16, 1945, and the text runs as follows:

I went to see Archie Boyle about the ELLI case and discussed with him at length SOE’s set-up in Russia. He again expressed to me confidentially his grave suspicions about George Hill, and also about one George Graham whose real name is Serge LEONTIEFF, a White Russian. The two are very closely tied and one always backs up the other.

I have written before about the highly dubious decision to employ a tsarist émigré for intelligence work in the Soviet Union (a phenomenon that does not appear to have fazed Liddell) and shall recapitulate it later in this bulletin. My primary objective in this report is to tread back to Mr. Leontiev’s early years (the transcription of his name that I shall primarily use, even though many of the documents favour the alternative spelling) to his arrival in the United Kingdom, and to his exposure to new influences. All information given here (unless I indicate otherwise) has been derived from records publicly available in the United Kingdom.

2. Leontievs in exile:

Serge was born on August 18, 1910, in Peterhof, the palace in St. Petersburg built by Peter the Great, modelled on Versailles, thus implying fairly grand connections. His father was Alexander Ivanovitch Leontiev, described as a musician: his mother Olga Leontiev, née Briger, was born on January 2, 1892, the daughter of Alexander Briger, a Lieutenant-General in the Russian Navy. (In a Gilbertian touch, Olga’s sister wrote that her father ‘was an officer in the Russian navy, but at no time that I remember was he actually at sea’.) Olga and Alexander Leontiev had been married on April 26, 1909, and escaped at some unspecified time during the turmoils of the Revolution.

Yet the marriage appeared to have broken down relatively early: Mrs. Leontiev had been living separately from her husband for several years when Serge made his request for UK naturalization on June 20, 1933. She divorced her husband on November 4, 1929, on account of ‘desertion’, and then married her second Alexander, surnamed Shidlovsky (described as a bank-clerk), on November 23 of that year. In his naturalization request, Serge gave his address as 31 Longridge Road, Earl’s Court, in London: his father lived nearby, in 46 Colet Gardens, London W.14. He had a brother, Dimitri, younger than him, born on May 2, 1915, who lived at 3 Ridge Close, Hendon, London NW 14, and who died on November 27, 1938, aged 23. Olga’s address was given in the naturalization papers as 5 Ridge Close, next door. This will be seen later to be a slight error.

Dimitri, whose profession was given as ‘journalist’ on his death certificate, died at home of cancer of the bile-duct – which must surely have been rare in someone aged only 23. The informant, present at the death, was his father-in-law. Maybe his mother was too distraught, but his father’s continued absence from the scene is puzzling. His body was cremated (according to the cemetery records on March 3, 1938, which must be wrong) and his ashes reinterred at the Kent and Sussex Cemetery in Tunbridge Wells on March 17, 1977. Tunbridge Wells, the home of so many disenchanted letter-writers to the Daily Telegraph, will come to play an increasingly important role in this story.

Serge likewise had lived with his mother for most of the time he had been in England. After their escape from Russia the family had arrived – according to Serge’s statement – in Malta in the summer of 1918, where they spent nine months before moving on to Rome. After ten months there, they arrived in England on January 17, 1921. (The dates do not compute, however: nineteen months back from January 1921 would take them back to June 1919.) As a minor, Serge presumably did not need separate identification papers, but he was granted a certificate of identity T. C. 4761, issued by the Home Office on September 20, 1926, which was due to expire on August 30, 1933. Strangely, he could not produce a birth certificate, something one would imagine his mother would have maintained a close eye on: indeed, when his step-father was naturalized, on July 31, 1931, the record states that documentary proof of the births of both sons was seen.

Serge provided some rich details about his career in England. He attended St Paul’s School, in Baron’s Court, and Heath Mont School, in Hampstead until the age of 16, whereupon (so he claimed) he studied in France for a year (1926-1927?), and then was hired as a clerk with E. W. Tate and Company. After a few months, Serge left for a similar position with M.D. Aminoff, carpet merchants, where he worked for two years. What is provocative is his asserting in his 1933 naturalization application that he in 1930 took the name ‘George Graham’ for journalistic purposes, as he was publishing articles for The Skating Times. (He was also described as a ‘BBC artist’.) The minutes to his naturalization papers rather enigmatically state: “When he becomes a [subject?] he will be at liberty to use any name he pleases, and S. of S. [Secretary of State] does not propose to take any action regarding his past use of the name ‘George Graham’.” Why this might have been controversial is not made clear. Yet, around 1929, his life had been significantly changed by his relationship with a prominent intelligence officer, as I shall explain.

The pattern of Serge’s movements will be shown to have some special significance. When he listed in detail his periods of residency – in His Majesty’s dominions – in order to complete his naturalization request, he gave ‘Malta’ for the period April 1919 to January, 1920, and then skipped over the time in Rome to an address of 94 Kensington Park Road, where he had arrived on January 17, 1921, and stayed for five months. Thereafter he recorded a rather peripatetic existence (three months in Quainton, Bucks.; seven months back at Kensington Court; one year and eleven months at Northway, N.W. 11; five months in Kilburn; a month in Southend-on-Sea in August-September 1924 – which sounds like a holiday; three years at Gloucester Walk, W8; three years and nine months at 3 Ridge Close in Hendon; and finally one year and nine months at 46 Colet Gardens, the address he was living at when he made his submission, the home of the Russian School of Ballet. (The last claim is a little puzzling: one sheet in his application states that his permanent address has changed to 31 Longridge Road, in Earl’s Court, while another indicates that he was ‘temporarily’ residing at 294 Earl’s Court Road.) He totalled that up as living in the United Kingdom for eleven years, seven months, with nine months spent in the dominions (Malta). The year in France seems to have been conveniently overlooked: elsewhere in his naturalization application, he described a two-month absence in France undertaken to recover from pneumonia.

Little appears to be recorded about Serge’s father, mainly because he never applied for naturalization. A newspaper report (in the Winnipeg Tribune) shows that ‘Alexander Leontieff, a former Colonel of the Imperial Guard, led the Old Moscow Balalaika Orchestra at a concert in London on May 30, 1931’. On Serge’s marriage certificate, he is described as ‘Colonel Retired’. And when he died at Middlesex Hospital, on August 28, 1957, his profession was given as ‘musician’. Serge was listed as the informant, with the given name of ‘George Graham’, and an annotation on the death certificate provocatively states: ‘Son’s name changed by War Office instructions’ – presumably referring to the occasion of his original new appellation rather than an interference in the procedures of the registrar, with George having to explain why, as a son, he carried a different surname. Thus the story about Serge’s already having assumed that name for his journalism appears to look rather suspect. Alexander Leontiev was buried in Hendon, and his gravestone is clearly marked.

3. Alexander Shidlovsky:

In fact the naturalization papers of Serge’s step-father, Alexander Shidlovsky, shed much more light on Serge’s background. Shidlovsky was born in Voronezh on June 25, 1896, was educated at the University of Petrograd [sic], and was a member of the Imperial Page Corps in that city. He had joined the Russian Army on June 1, 1915, serving as lieutenant until the end of 1917, when he was discharged due to ill-health. He then joined the White Russian volunteer army, and in April 1919 arrived at St. George’s Barracks, Malta, where he resided until September 1919. (Thus Serge’s arrival in Malta coincided exactly with that of Shidlovsky.) The record then indicates that Shidlovsky served in General Denikin’s Army in 1919-1920, and next obtained a position as an interpreter with the British Military Mission in South Russia, with which he was engaged for a month or so before the complete withdrawal of the expeditionary force. If the statements made by Olga and her second husband are true, there would not appear to be any overlap in their presences in Malta, but since Olga’s declaration about the Mediterranean movements does not hang together, one might conclude that there was an attempt to muddy the waters in this respect.

Moreover, Shidlovsky’s statement of residential addresses almost directly mimics those of Serge, detailed above. He arrived in the United Kingdom on March 27, 1921, and hied immediately to Kensington Park Road on that same day, where Olga and sons were presumably awaiting him, moved with them to Quainton, and then returned en quatre to Kensington Park Road. Shidlovsky then accompanied Olga and family to Northway, although he described the location as Hampstead Garden Suburb, not Hendon, and moved with them all to Brondesbury Villas in Kilburn, in March 1924. Likewise, he shared the holiday in Southend with Olga and her sons, and spent the following two years at Gloucester Walk. His statement breaks off at this point, but the address provided on his application (of July 2, 1931) is his marital home at 3 Ridge Close, Holders Hill Avenue, NW 4. Thus Olga and Shidlovsky had been living together quite openly for more than a decade, and the question of her husband’s ‘desertion’ must be highly questionable (unless he abandoned her in Malta). Yet they all came to England, Alexander Shidlovsky making a definitive choice of coming to the UK to follow Olga when his relatives primarily opted for France or Estonia as their place of exile.

The list of referees for Shidlovsky’s naturalization application includes one or two distinguished names. Sir Bernard Pares, then lecturer at the School of Slavonic Studies at University College, London, claimed that he had known the applicant for over twenty years, having been friends with his father. Retired Vice-Admiral Aubrey Smith testified to his good character and loyalty, and likewise dated his friendship as lasting over twenty years, when he (Smith) had been British Naval Attaché in Russia between 1908 and 1912. Yet Sir Aubrey wrote a more cautionary letter in responding to a communication from ‘Sir John’, suggesting that the application may have been made to further his career at the Ottoman Bank, and that his case was perhaps not of the highest priority.

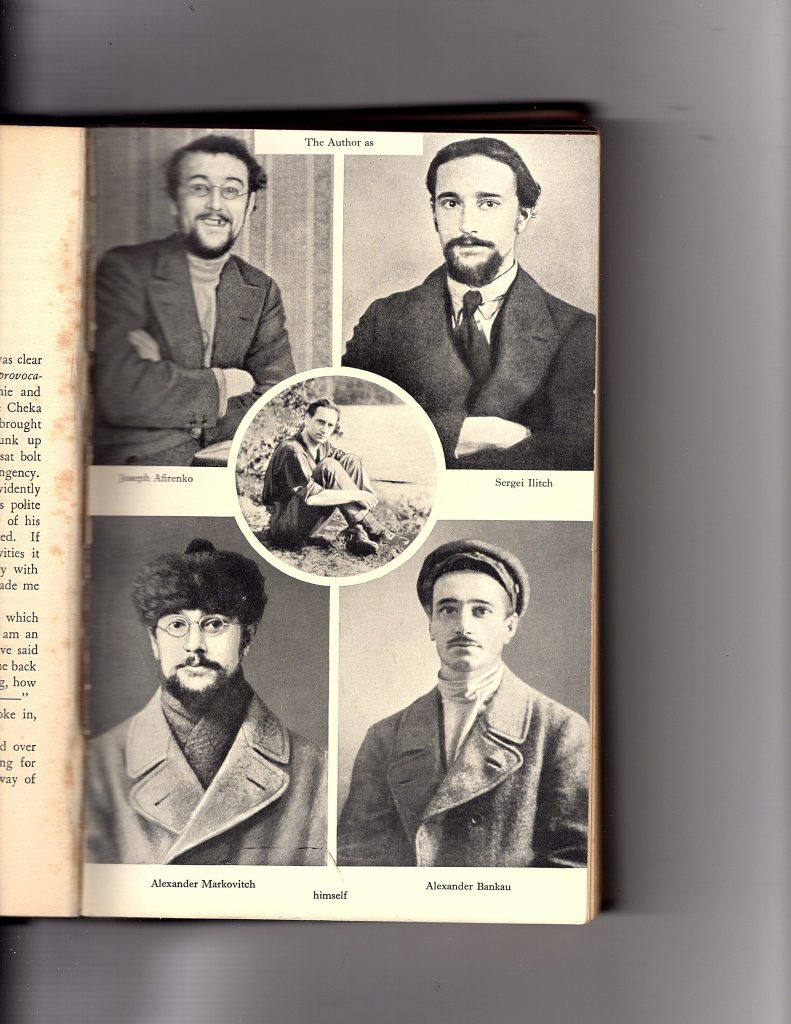

A quick search on the Web brings more facts about Alexander’s lineage to the table. When he married Olga Leontiev, he gave his father’s ‘rank or profession’ simply as ‘Russian nobleman’, He did indeed come from an illustrious aristocratic background, his father being a prominent member of the Duma (see https://prabook.com/web/sergei_iliodorovich.shidlovsky/3775124). This page indicates that Alexander ‘finished the Page Corps, worked as poruchik [‘lieutenant’] in horse artillery lifeguard’ before migrating to England. He, his brother, and his father all appear to have been educated at the Tsarskoe Selo Lyceum, while Nikolay Shidlovsky (1843-1907), who chaired the 1905 Commission named after him, was probably a semi-distant relative. Alexander’s mother, still alive in Paris when he applied for naturalization, was named Alexandra, née Saburov. (I shall leave further exploration and explication of the Shidlovsky family to other genealogists who may chance upon coldspur.)

Thus, at first glance, the story of the Leontievs-Shidlovskies would appear to be like many other accounts of exiled White Russian aristocrats: déraciné, nomadic, slightly louche, mixing with their fellow-sufferers, perhaps vainly hoping that tsardom would somehow be restored in their native land and that they would be able to recover their lost estates. Yet this clan is somehow different: they do not seem to be short of money, and they go about their business with confidence. No humble careers of taxi-driving or washing dishes (in the way that so many Russian aristocrats ended up in Paris) for them: Serge was sent to good schools, and could afford to spend a year in France. Shidlovsky settled down to a solid job as a ‘bank clerk’, which may understate his role: elsewhere he is described as a ‘bank official’. There seem to have been no furtive counter-revolutionary gatherings, with risks of infiltration by Soviet spies, as happened so frequently in Paris. Yet they were definitely ‘former people’, with counter-revolutionary tendencies, and to be watched by Soviet intelligence. In addition, there was one common figure behind much of their life-events. And his name was Sir Paul Dukes.

4. Paul Dukes:

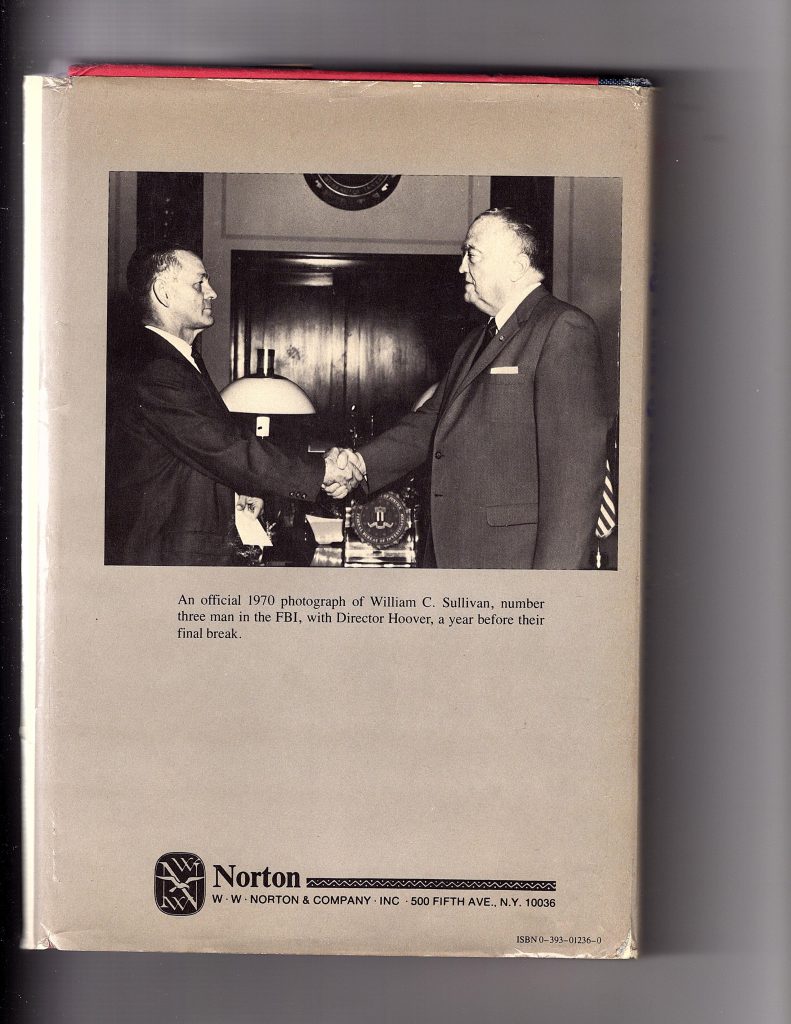

The archives supporting George Graham show three key events where the name of Paul Dukes appears. Chronologically, Dukes’s name first appears in the marriage certificate for Olga and Alexander, dated November 23, 1929, since he and N. Nicolaeva-Legat are listed as witnesses to the event. It next comes up in Serge’s statement about his employment, made within his naturalization request in June 1933. After the period with Aminoff, Serge’s application states that he became secretary to Sir Paul Dukes, Chairman of British Continental Press Ltd., probably in 1930. Dukes acted as referee for Serge’s naturalization request, and described Serge as ‘an upright and conscientious young man’. And these connections present a whole new dimension to the fortunes of George Graham and his extended clan, and their links to British Intelligence, since Dukes networked with British military personnel with experience in Russia after the revolution, intelligence officers in MI5 and MI6 in World War II, and an influential Russian émigré community in between. Serge Leontiev’s career appeared to take on a dramatically new – and superficially positive – turn after he met Paul Dukes in 1929, and began his metamorphosis into George Graham.

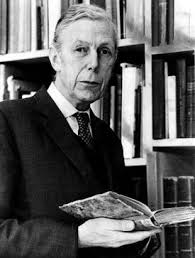

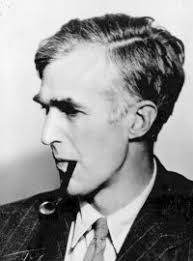

Dukes’s career has to be viewed in two dimensions: one, as a prominent musician and conductor; two, as an informant to the Foreign Office and recruit to MI6. His life is infused with much mystery: he was not granted any DNB entry until 2004, despite an illustrious early career, and what has been published (written by Michael Hughes) is a very sparse and vague affair that does not exploit any archival material. Dukes’s Wikipedia entry (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Dukes) is likewise imprecise on dates, and erratic in its facts. Much of the information about him derives from his own memoirs: Red Dusk and the Morrow (1922); The Story of ‘ST 25’ (1938): and An Epic of the Gestapo (1940), a source genus that is frequently unreliable. Some snippets of information have percolated into the writings of Christopher Andrew, Keith Jeffery, and Michael Smith, with the latter alone providing identifiable archival sources to support his account. Thus contradictions in the timing of events have to be resolved in order to present a cohesive story.

The musical side of things is relatively simple. In 1908, he took up a teaching position in Riga, Latvia, and the following year moved on to St. Petersburg, where he was accepted at the Petrograd Conservatoire. He was encouraged by Albert Coates, who was the Principal Conductor of the Russian Imperial Opera at the Mariinsky Theatre, and also served as English tutor at the Naval College. In 1913 he graduated from the Conservatoire, and Coates hired him to assist in the training of soloists in their operatic parts. It is highly unlikely that he would have been recruited by Mansfield Cumming of MI1c at this time, although he probably did act as an informant to the Foreign Office, ‘ostensibly as a King’s Messenger’, as Jeffery writes. The milieu, however, allowed him to be introduced to several illustrious names in the world of dance, and guided his introduction to eastern mysticism.

The war caused his artistic plans to stumble, and he was co-opted to the Anglo-Russian Commission in early 1915, where he worked under the leadership of the novelist Hugh Walpole, and was given the task of tracking the Russian press across the whole country. This Commission, according to Phillip Knightley, was an office of the British Department of Information established in 1915 that was involved in arranging war supplies from the United Kingdom to Russia, although more sober descriptions suggest it was much more a propaganda outlet, that it struggled with its task, and was dissolved in March 1918, after the revolution. Hughes indicates that Dukes did return to London during this time, so his importance and reputation were surely further recognized. In a provocative aside in The Story of ‘ST 25’ (a gripping memoir of life evading the Cheka, which merits being re-issued), Dukes wrote: “In the summer of 1916 a lady who was a great personal friend of mine and had much influence on my life at the time confided in me her secret thought of making away with the infamous ‘Monk’ [Rasputin]’ Who was the mystery lady?

The focus now shifts to his espionage role. Michael Smith informs us that Dukes next joined a relief mission in the South of Russia, one funded by the American YMCA, but was soon recalled to the United Kingdom that summer, suggesting that the Foreign Office was keeping close tabs on him. It was then that Mansfield Cumming, the head of MI1c, the emerging MI6, recruited him as agent ST/25, with a mission to help finance and accelerate the plans of the National Centre for insurrections in Petrograd and Moscow. The National Centre was an underground counterrevolutionary movement: as the Great Soviet Encyclopedia recorded: “Between July and November 1919, the VChK [Cheka] eliminated the Petrograd branch of the National Center, which was headed by Shteiniger, as well as the espionage network directed by the head of British intelligence in Russia, Paul Dukes, who was in contact with Shteiniger’s group.”

For Dukes had succeeded in smuggling out intelligence to MI1c in Finland, which guided the celebrated raids by Augustus Agar on the Kronstadt naval base in June 1919. Dukes was in great danger, but could not easily be exfiltrated: despite gaining a reputation for being a master of disguise (‘the Man with a Hundred Faces’), he was outwitted by the Cheka, and had to make a desperate flight through Latvia back to the United Kingdom. He escaped with the help of Alessandro Gavrishenko, a former Imperial naval commander and member of United Great Russia. Dukes just avoided execution, but Gavrishenko and other allies were shot. Dukes was a marked man. He later admitted, when arriving with his new bride in Paris on January 22, 1923 that the Bolsheviks had ‘put a price on his head for the last three years’. He was more explicit when he published The Story of “ST 25” in 1938. Scandinavian newspapers had printed an interview with him while he was still in Latvia, and given his real name. He wrote: “ . . . long before I reached London I realized that Red Russia was closed to me, perhaps for ever. Moscow, enraged at my escape, was broadcasting denunciatory fulminations to the four corners of the globe and a price was set on my head if I ever returned.”

Dukes’s reputation back home was secured, and he had brought much acclaim to MI6 in political circles. Early in 1920, Agar earned a Victoria Cross, and Dukes was knighted. At this time, he met again by chance Alexander Briger, whom he had known well in St. Petersburg. He was soon employed on secret missions again. In May 1920, he went to Poland, with Rex Leeper, of the Foreign Office’s Political Information Department, masquerading as the latter’s ‘secretary’, and submitting intelligence reports. He toured eastern Europe with Sidney Reilly and Vladimir Orlov, recruiting agents, and, as Jeffery reports, nursed ambitions of returning to Russia as an agent himself. Yet his ensuing activities, lecturing and writing, his contacts with unreliable White Russians, and the attendant Bolshevik interest in his movements effectively disqualified any further exploits. In 1919 he had also joined a cabal of other MI6 officers in becoming members of the Bolshevik (or ‘Bolo’) Liquidation Club, an entity dreamed up by our friend Stephen Alley. That was not a move designed to endear him to the Kremlin. And it would be a significant consideration when I pick up his story in the late 1930s.

Moreover, Dukes could not stop talking about his exploits. As Michael Smith writes: “Paul Dukes wrote a long series of highly-publicised articles in the Times, thus eliminating the possibility of his being used for secret service missions again.” Jeffery dubbed him ‘an inveterate self-publicist’. Hughes refers, in addition, to the possibility that the establishment was ‘uneasy about Dukes’s somewhat eccentric interest in various forms of eastern mysticism’. He also promoted himself in the USA, and his career took on a new-agey turn in that country. Hughes again: “About 1922 he joined a tantric community at Nyack, 15 miles from New York, led by Dr Pierre Arnold Bernard (known as the ‘Omnipotent Oom’)”. While living there, Dukes married Margaret Rutherfurd (whom he would divorce in 1929): she was the former wife of Ogden Livingston-Mills, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, and the daughter of Anne Harriman, the second wife of William Vanderbilt. Rutherfurds, Harrimans, Vanderbilts, capped with the Omnipotent Oom: it was all a heady mixture.

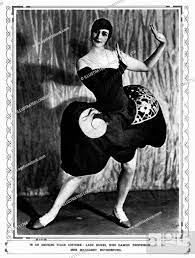

Lady Dukes

But before I move forward to the intelligence plots of the late thirties and early forties, an investigation into his partner at the Olga Leontiev-Alexander Schidlovsky wedding in November 1929 is called for. Who was N. Nicolaeva-Legat?

5. Nadine Nikolaeva-Legat:

Nadine Nikolaeva-Legat (as her name is more commonly spelled) was born Nadezhda Briger in 1895, the daughter of Alexander Briger (1861-1931), a Lieutenant-General in the Russian Navy (see above), and the sister of Olga, Xenia and Vladimir. She became a dancer with the Imperial Russian ballet, and married another dancer, Nicolas Legat (1869-1937), as his second – or possibly, third – wife, probably around 1915-1916. He was notably almost twenty-seven years older than she: she describes him in her memoir as ‘principal soloist to his Majesty the Tsar of Russia, Ballet master and Professor at the Imperial School of St. Petersburg’. According to the Wikipedia entry of her husband, she rose to become the Prima Ballerina of the Imperial State theatres of Moscow and St. Petersburg. Because of the age difference between the couple, and parental disapproval, they had to elope. During World War I, they performed in Paris and even in London, at the Palace Theatre, in The Passing Show, before returning by minesweeper to their parents’ home in St. Petersburg, with Nadine now pregnant.

The Legats were separated from the family at the Naval College after the revolution, and arrests and shootings dominated their lives. In a somewhat cryptic passage in her memoir [see below], Nadine indicates that Rose, her loyal dresser, was a Bolshevik, and might have been able to obtain a pass for her. Yet her sister Olga was designated to try to reach the family and possibly arrange for their escape. (“My sister, Olga, pointed out that it was better that she should go, for she was married to a wealthy Guards officer with an estate in Kiev and her own position was open to question.”) Indeed, Olga did engineer the escape of the parents and sister Xenia to Kiev, although Xenia had by then lost her husband in the fighting. Olga’s trials were nevertheless not over: she and her husband were threatened with shooting by the Communists in Odessa, and only intervention by the French Commandant, and an exchange of twenty Bolshevik prisoners for the lives of Nadine’s father and brother-in-law (Serge’s father), allowed them to gain a ship to Constantinople. King George V himself intervened to offer the refugees hospitality in Malta. Since Alexander Briger was a Director of the Anglo-Baltic Shipping Company, he was able to take advantage of a job offer by the company in London, and moved there with his wife, with Xenia, and with the daughters of Xenia and Nadine.

After the revolution, however, Nicolas and Nadine were celebrated enough to put on balletic exhibitions around what was then the Russian Soviet Republic. According to Nadine, their plans for reforming the Moscow State Ballet School were met with approval, and in 1922 they were eventually able to gain permission to go abroad for six months, partly because Lunachatsky [sic, actually Lunacharsky], the highly influential Superintendent of Education, was a family friend. They then toured Europe for several years. They travelled to Berlin, where Nadine encountered her brother, Vladimir, and learned that her family was safe in London, although her father had struggled with finding a regular job after the Anglo-Baltic Company had been dissolved. They landed up in the United Kingdom in 1923, but after a couple of years, left to spent several seasons touring in Europe, primarily with Dhiagilev. In 1928 they returned for good, to teach the Legat System of Ballet, at 46 Colet Gardens. They thereby fostered such prominent stars as Anton Dolin, Margot Fonteyn, Andre Eglevsky, Moira Shearer and Nathalie Krassovska. The Russian Ballet Association was formally registered in 1938.

A member of the Briger family in Australia let me know about Dukes’s relationship with Nadine. The Australian side of the Briger family has been well documented. Nadine’s nephew, Andrew (born in Berlin in 1920), the son of her brother Vladimir (1885-1971), travelled between Paris and London, and occasionally helped run the ballet school while he was studying architecture at the Regent Street Polytechnic. Because of his connections with the famous ballerina, when he emigrated to Australia, he was introduced to Elizabeth Mackerras, who was the sister of the famous conductor Sir Charles Mackerras, and he and the family found common interests in opera and the Russian heritage. Andrew and Elizabeth married in 1957. My contact described Dukes in these terms: “I knew Sir Paul Dukes quite well – he was a very distinguished man in his day, knighted for his work – ended up travelling the world (including Australia) teaching yoga and I have his yoga book. Apparently he was also Madame Legat’s lover for a while, certainly gave the school a lot of money, for no particular reason.”

Thus, if Dukes was squiring Nadine Nikolaeva-Legat in November 1929 (and openly enough to be companions at a prominent marriage ceremony, and official witnesses to the event), it is perhaps no surprise that he had been divorced from Margaret Rutherfurd that year. The New York Times announced, on January 20, 1929, that Lady Dukes had been awarded a divorce in Paris on the grounds of her husband’s desertion, and added, provocatively, that ‘among her friends, there have been persistent rumors that she intends to marry Prince Charles Murat’. (The Prince’s desires in this arrangement are not recorded, but it appears that the determined Margaret Rutherfurd gained her objective.) The fact of Dukes’s generosity to the Ballet School should be noted also, as the behaviour would point to a certain carelessness with money.

Yet there was another aspect of this relationship. While it is not central to my story, the matrilineal line of Nadine and her brother, Vladimir, has an incidental fascination all of its own. Vladimir’s cousin, Prince Felix Youssoupoff, had led the group that assassinated the Russian court lothario Rasputin. That would, in turn, link the family to Stephen Alley who, though without definitive proof, has been noted (for example, in Douglas Smith’s biography of Rasputin) as having been involved in Rasputin’s murder while working for the British Control Office in Saint Petersburg. What is more interesting is the appearance of other family members in the photographic record.

Nadine died in 1971, and the memorial at her grave in Tunbridge Wells (above) is an informative artefact. It memorializes Alexander Briger (her father), Ludmilla Briger (probably her mother, 1861-1954), Vladimer de Briger – in an alternative Frenchified form of the name (her brother), Zenaida de Briger (Vladimir’s first wife, fully Zenaida Pavlovna Sumarokov-Elston, 1886-1954) and her husband, Nikolay [Nicolas] Gustavovich Legat. The person who surely arranged for this memorial to be set up was her sister, Olga, mother of Serge aka George Graham, and widow of Alexander Shidlovsky who had died, also in Tunbridge Wells, in 1969. Olga died in the same town on December 14, 1975.

In 2021 Nadine’s memoir The Legat Story was published by Cadmus Publishing. It is an appealing but slender offering, dedicated to showing her devotion to her husband and an admiration for his legacy. But it is also deceptive. She has little to say about her sister Olga (about whom she appears a little jealous), restricting her observations to a few comments such as ‘my sister Olga always asserted that a man without a uniform was scarcely a man at all’. She.maintains the fiction that Olga and her first husband were living together in London (“Later Olga and her husband also came to England and found a house in Golders Green where they could all be together”), and writes nothing about Serge and Dimitri. It is almost as if she disapproved of her sister’s liaison, although she was, of course, the prime witness at Olga’s marriage to Shidlovsky.

Nadine also reveals more about Paul Dukes, although she is silent on any question of an affair. She met him again in Paris, and they discovered a shared interest in yoga, vegetarianism, and the teachings of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. She must have found in Dukes a soulmate, since Nicolas was very dismissive of her spiritualist enthusiasms. And then Dukes started to realize one of his own ambitions, taking ballet classes from Nicolas and Nadine. She considered him ‘an unusually apt pupil’ and even started partnering him, billed as ‘Paul Dukaine’, in such dances as Le Jardin Exotique, for which Dukes created a new score. While on tour (unaccompanied by Nicolas) they ‘argued’ far into the night; Dukes’s role was not well publicized until they reached Hull in May 1930, and he was unmasked. Soon after, Dukes was invited on a speaking tour in America, and the professional partnership was broken up. But they must have enjoyed their period of intimacy.

6. Dukes in the Thirties:

A possible sequence of events emerges. Having concluded his world tours in the late 1920s, including the conducting of his own musical compositions for the Ballet Moderne in New York, Dukes returned to London. His exploits in the ballet, and his relationship with Nadine, passed unnoticed by the world at large (and indeed his ODNB entry is silent on the accomplishments of Paul Dukaine). Here Dukes struck up again his acquaintances with the Brigers and other exiles from the musical world of pre-war St. Petersburg, most notably Nicolas and Nadine Legat. Since his divorce for desertion came through in early in 1929, his misconduct must have become public some time before that (as Nadine’s account of their balletic exploits would tend to confirm), and Nadine was courageous enough to be seen as her lover’s companion when they both witnessed the marriage ceremony of her sister and Shidlovsky in November 1929. Meanwhile, Nicolas’s heath was fading. He was taken ill with pneumonia, and then pleurisy, and eventually died on January 24, 1937.

The occasion of Olga’s second marriage makes perfect sense as the time when Dukes would have been introduced to her nineteen-year old son. The following year, Dukes was appointed chairman of the British Continental Press, and gave his protégé an opportunity by appointing him his secretary. It would not be capricious to suggest that Dukes at this time decided to groom the young Leontiev for a role that he could no longer perform himself. He managed to have Serge (and his father) installed with the Legats at 46 Colet Gardens, where their Dance School was housed.

Dukes’s relationship with Nicolas Legat appears on the surface to have been cordial still. In 1932 the firm published Legat’s The Story of the Russian School, a volume that had been translated from the Russian by Dukes, who also provided a Foreword. Other books on dance appeared, such as Lincoln Kerstein’s study of Fokine, in 1934. It is difficult to imagine that the Press thrived on such a limited range of works, and, as the decade progressed, Dukes was perhaps feeling a lust for further adventure. He gave up his chairmanship of the Press in 1937, according to his New York Times obituary. In any event, some very bizarre press releases were suddenly issued indicating the demise of Sir Paul, perhaps designed to ward off any Soviet persecutors who might still be wanting to have him eliminated.

On May 20, 1935, the Perth Daily News (of Western Australia) published a report from Paris that ‘the death occurred here today of Sir Paul Dukes, K.B.E., the English composer and author, aged 46’. This was echoed in the Melbourne Herald the same day. Yet I can find no trace of the story being reported anywhere else in the world. Dukes certainly had an interested audience in Australia, but why he (or his bosses) would try to channel the message of his demise so clumsily is a mystery. To mount a comprehensive disinformation campaign is one thing: but to launch a half-hearted one, and then not disappear from this earth, so that the opposition would be wised up that some deception was planned, was simply amateurish.

What might Dukes have been thinking? The only possible clue that I have detected is the factoid that I cited in an earlier report. A short piece (in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram) announced that on November 10, 1934, Alexey Leontieff, a former colonel in the Czarist Army, and manager of a local machine supply office, faced a firing-squad in Novosibirsk, for failing to provide proper machinery to a nearby collective farm. Out of all the possible events, why on earth would the NKVD release such a gobbet, when so many millions were being murdered during Stalin’s purges? Was Alexey a brother of Alexander? Was the announcement provocation? Did the NKVD intend to lure ‘the Man with a Hundred Faces’, its Public Enemy Number 1, to the Soviet Union? Was Dukes asked by the Leontiev family to help rescue a relative? I have no answers.

In 1938 he published his memoir The Story of “ST 25”, which was essentially a richer version of Red Dusk and the Morrow. To this he added a bizarre and equivocal Epilogue where he appeared to have been hoodwinked by Stalin’s new constitution of 1937, and, despite the turbulence of the Show Trials, suggested that the Soviet Union was making moves towards democracy, and was supporting capitalist impulses. One can interpret this only as his attempt perhaps to get back into Stalin’s good graces (not that he would ever have been in them) so that he might visit the country again, but all he achieved was to ruin his reputation as a sworn enemy of totalitarianism, and undermine his position as a reliable analyst of the Soviet Union. (In a report written by Elena Modrzhinskaya, Head of Department 1, Third Section, of the First Directorate of the NKVD, in April 1943, cited in Nigel West’s Triplex, p 319, appear the following sentences, which would appear to confirm Dukes’s intentions: “A senior British intelligence officer, Paul Dukes, is involved in training intelligence personnel on Soviet matters. Before the war he spent some time in Berlin, where he is said to have been linked with Goebbels; in 1939 he attempted to re-enter the USSR, citing his ‘pro-Soviet’ views.”)

The record is disappointingly thin about his exploits after leaving the Press. The ODNB entry states: “On the eve of the Second World War he was asked by some acquaintances to visit Germany in order to trace the whereabouts of a wealthy Czech businessman who had fled from house arrest following his imprisonment by the Nazis.” He wrote up those exploits in his 1940 book An Epic of the Gestapo, which describes his confrontations with the Gestapo in the summer of 1939. Yet here he renewed his expressions of antipathy to both fascism and communism, drawing the attention of any watching NKVD officer, and had thus abandoned any attempt at subterfuge. In his Introduction, he wrote:

Despite the antagonism that existed between the Nazi and Bolshevist leaders until August, 1939, I was struck from the outset of the Hitlerian regime by the remarkable similarity of its methods to those of Moscow. In the spring of 1939 I began a study of these resemblances. Somewhat paradoxically, I conducted negotiations at the same time for the publication in Germany of my Russian memoirs in which I strongly criticized the Moscow administration, and assistance was spontaneously offered me in this by the hardy diplomat, Richard von Kuhlmann, who played a prominent part on the German side in the framing of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Soviet in 1918. Furthermore, at the suggestion of the Japanese Ambassador in London, M. Shigemitsu, I had a number of conversations with General Oshima, the Japanese Ambassador in Berlin, on the subject of the Anti-Comintern Pact, of which he was one of the authors.

Paul Dukes had arisen from the dead. Meanwhile, after the death of her husband in 1937, Nadine Nikolaeva-Legat was left to run the studio classes alone. When war broke out, she sought an alternative location, first in Mersea Island, near Colchester, Essex, and then in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. At the end of the war she moved her Russian School of Ballet to the town of Tunbridge Wells, in Sussex, and later to larger premises at Finchcocks Manor, in Goudhurst, Kent.

7. WWII – Dealing with the NKVD:

After his mission in Germany, Dukes joined British Ambassador Sir Nevile Henderson on the last plane to leave Berlin before Britain declared war on Germany, on September 3rd 1939. Obviously wanting to assist the war effort, he looked around for appointments. His ODNB entry merely states: “In the Second World War, Dukes lectured on behalf of the Ministry of Information, and served as a director of companies involved in aircraft production.” Certainly, in his final paragraphs of An Epic of the Gestapo, he predicted that, despite the short-term accommodations, the autocracies of Germany and Soviet Russia, even though they had so much in common, would come to blows eventually. “Where Nazi Germany and Bolshevist Russia must eventually come into conflict is in the contradiction between the hypernationalistic ideals of Hitler and the neo-imperialistic and ultimately world-revolutionary aims of Stalin. Here clash is inevitable.”

Thus, like other Tory grandees opposed to both forms of totalitarianism (e.g. Sir Robert Vansittart), Dukes, with his expressed anathema to Communism, was probably taken aback by Churchill’s over-expansive embrace of the Soviet Union when Hitler invaded it in June 1941. Yet he would have swiftly realized that some accommodation with Stalin’s regime was necessary to defeat the Nazi foe. And the overtures towards some intelligence-sharing with the Soviets came quickly. Hugh Dalton, the Minister responsible for the Political Warfare Executive (and SOE) came to an agreement with Menzies, the head of MI6, that approaches should be made to Moscow. George Hill, the veteran agent from 1918 in Russia, was appointed head of an emergent Russian Section of SOE in August 1941.

The SOE-NKVD agreement was a strange one. While the Foreign Office was very sensitive to the opinions of the (mostly conservative and aristocratic) governments-in-exile, SOE was notoriously gung-ho about co-operating with leftist elements, and thought that native communists in western Europe would be a valuable source of subversion and sabotage. Hugh Dalton had, ever since his push to be appointed SOE’s minister, seen the agency as a mechanism for introducing socialism to western Europe after the war, while MI6 was institutionally nervous about having anything to do with the Reds. For their part, the Soviets were desperate to use the British to help replace their sources of intelligence in Western Europe. Their Rote Kapelle network was being mopped up, and their courier-lines were broken. Their aircraft could not travel far enough to drop spies in western Europe, and make the return home. Yet, if the Soviet objective was primarily to gain information about German military strength and deployment, the mission did not harmonise well with what was the business of SOE, namely sabotage. Fortunately (for the health of the accord, anyway), the NKVD appeared not to discriminate between MI6 and SOE: the agencies were both seen as ‘British Intelligence’, and whoever arrived on Russian soil to operate would necessarily be regarded as a spy, since espionage was what Soviet citizens abroad were required to do, and hence such activity was automatically ascribed to imperialistic foreigners who were admitted to the Soviet Union.

As the heads of MI6 and SOE strategized about the mission to Moscow, it might appear that Paul Dukes carried clout beyond his current authority. Yet the influential figures in intelligence were all familiar with his WWI role. Churchill himself, who frequently directed SOE’s business behind the back of his War Cabinet, had urged intervention in Russia in 1919. Desmond Morton, Churchill’s intelligence adviser, had in 1919 been head of MI6’s Section V, spurring anti-Bolshevism efforts. Colin Gubbins, director of operations for SOE, had served on General Ironside’s staff in Murmansk in the summer of 1919. And then there were Dukes’s old colleagues: Robin Bruce Lockhart, imprisoned for his role in the ‘Lockhart Plot’ (which Dukes claimed was not a ‘Lockhart’ plot at all, but a scheme engineered by Sidney Reilly), was head of the Political Warfare Executive; his 1920 partner in Poland, Reginald Leeper, was again head of the Foreign Office’s Political Information Department; George Hill was the head of the new SOE Russian Section; and Stephen Alley in MI5 was guarding any challenge to British interests from intruders from the Baltic States.

Stewart Menzies thus saw the Anglo-Soviet agreement of September 1941 as an opening to build some espionage capability in the Soviet Union. As I have written elsewhere, George Hill effectively reported to Stewart Menzies, not Colin Gubbins, during his time in Moscow and Kuibyshev. And it was through the exploitation of his reputation, and his long-established relationships, that Dukes was able to introduce George Graham to the SOE mission to Moscow.

8. George Graham – Marriage & SOE:

The Anglo-Soviet agreement between SOE and the NKVD was not signed until September 30, 1941. Yet Hill, on HMS Leda, and his staff members Truskowski and Graham (on another ship in the convoy) left the Clyde on September 20, clearly anticipating the formality. Thus Graham’s preparation as a cipher clerk must have begun a long time beforehand. In his memoir, George Hill claimed that he had selected Graham himself out of the Intelligence Corps. Yet the official historian of the Intelligence Corps has informed me that there is no record of his service in that distinguished cadre.

But first, Graham himself entered marriage. Whether this event was arranged for him, in order to boost the solidity of his curriculum vitae, or whether it was a true love-match, cannot be easily determined. On June 30, 1941, the Register Office in Amersham, Buckinghamshire, solemnized the marriage between Serge Leontieff, bachelor, of First House, Seer Green, and Edith Manley Axten, four years older at 34, spinster, of Twitchell’s End Gardens, in Beaconsfield. Serge’s mother and step-father were the witnesses. Graham gave his rank as Private 10850488, in Intelligence, and declared his father as Alexander Leontieff. Another marriage certificate was created, however. In the second version (which clearly describes the same event, as the names, date, and addresses are otherwise identical), Graham/Leontiev gives his parents’ names as Philippe Leontieff and Anna Grigorieva. Presumably, with obvious capabilities as a native Russian speaker, any identity as ‘George Graham’ would not have fooled the Soviet authorities, so he had to have a lineage invented to distance himself from the aristocratic Leontievs. Maybe the NKVD, when vetting Hill and the members of his team, demanded to see some supporting documentation.

There may not be much significance in the timing of this late June marriage, so soon after Churchill’s announcement of support for the Soviet Union, yet, two days earlier, Mason Macfarlane’s advance guard of 30 Mission had arrived in Moscow and started passing on veiled ULTRA secrets to the Soviets. If a role had already been identified for George Graham, the final steps in the procedure were being out in place.

[I shall now re-present what I wrote in my May 2021 bulletin about Graham’s time in the Soviet Union.]

About Graham, Hill said little, only that the Lieutenant was in the Intelligence Corps, and that Hill had selected him as his A.D.C. Nevertheless, he relied upon him extensively. One of the items that the Hill party took with them to Moscow was a heavy Chubb safe in which to lock the codes and ciphers each night, but when the embassy was evacuated to Kuibyshev, soon after their arrival, because of the proximity of Hitler’s army, the safe had to be left behind. When an apartment had been found for the SOE office in Kuibyshev, Hill wrote in his diary: “We take care never to leave the flat alone; poor Graham is practically chained to it. Our files and codes are kept under lock and key when not in use. Not in a safe, deary – we ain’t got one – but in our largest suitcase, which is nailed to the floor.” [Much of Hill’s memoir derives from letters that he sent his wife.]

Yet a few months later, Graham and Hill were separated. When it was safe, after a few months, to return to Moscow, Ossipov went first, followed by Hill in early February. But Hill had to leave ‘Trusco’ and Graham behind, much to Hill’s chagrin. “I don’t like being separated from Graham, though, especially on account of coding,” he wrote. Trusco was scheduled to return to England in mid-February, so Graham would have sole responsibility for the flat. Before Hill left (by train), he had to write out orders for Graham, ‘covering every likely eventuality’. “Codes and cash we deposited with the Embassy, otherwise poor Graham would have been tied to the flat for keeps: he will do his coding at the Embassy”, he continued.

Hill’s chronology is annoyingly vague (and not much helped by Peter Day in Trotsky’s Favourite Spy), but it seems that Hill did not see Graham again until he returned to Kuibyshev in about July 1942, to renew his passport, as he had been recalled to London for discussions. Even (or especially) in wartime, strict diplomatic protocols had to be obeyed. Thus Graham had been left for several months without any kind of formal supervision. As a member of the Intelligence Corps, his credentials were presumably considered impeccable.

I add a few annotations. In his memoirs, entrusted to his daughter, Truskowski made fleeting mentions of Hill and Graham. “My little mission was composed of a swashbuckler called Hill, a rather dim type. There was an equivocal type who spoke excellent Russian called Graham; he was not what he purported to be but he really was dim.” And in 1988, in a letter to Mark Seaman (the ‘SOE historian’), Truskowski wrote: “As for Graham, he was rather a colourless type, no match for his boss.” On what aspect of his personality Graham let himself down it is not clear, but it must certainly have been dangerous to have left him alone under the surveillance of the NKVD.

And then there appears more damaging suggestions. My informant in the Briger family (who had been told by relatives that Graham ‘had been a spy for the English in Russia’) wrote to me with the following tidbit about Graham: “He also fell in love while spying in Russia, which made it so difficult and worse. A real spy story.” Yet foreigners in the Soviet Union did not simply ‘fall in love’ after chance meetings. Any encounter would have been arranged by the NKVD, as a ‘honey-trap’, and the amoureuse would have been selected, instructed, and then been required to report in full to the secret police. Clandestine photography would have been employed, in the fashion that the British Ambassador to Moscow, Sir Geoffrey Harrison, was blackmailed by the KGB in 1968. Thus Graham would have been threatened with disclosure if he did not reveal information – probably his codes there and then, and surely further secrets when he returned to the United Kingdom.

One has to assume that all communications between London and Moscow at this time were intercepted and decrypted by the NKVD. If one inspects file HS 4/334 at the National Archives, for instance, one can find dozens of cables discussing SOE activity in eastern Europe (such as incursions into the Baltic States) that were laid open for the Soviets to interpret, and change their negotiation tactics. These matters deserve a completely independent study which could be dramatic enough to cause the history of the onset of the Cold War to be re-written.

Graham’s time in the Soviet Union was undeniably a disaster. He was ill-prepared, an obvious plant, and utterly unsuited to the position that required a high degree of maturity and attention to security procedures. Archie Boyle’s comment to Guy Liddell that Hill and Graham were ‘very closely tied and one always backs up the other’ takes on a new significance. Hill very openly took up with his mistress, Luba Polik, the hotelier, and would have defended his aide and cipher clerk if security breaches occurred because of the latter’s carelessness or romantic dalliances.It is no wonder that Guy Liddell dropped any further reference to him when he discovered the gory details. And the experience would lead to serious problems with Graham’s mental health.

9. Post-War Tragedy:

The Grahams had two children, one born during the war, after Graham’s return on leave, and the second after he had been demobilized. Again, the official records are a little troubling. On www. ancestry.com, the primary indicator of the birthdate of Christopher Graham is given as March, 1945. Thus Serge should have been in the UK in June 1944: indeed the archives of the Russian section of SOE show that Graham (D/P 103) arrived in London on leave on May 4, 1944. According to HS 4/331, on April 19, Hill had cabled London to suggest that Graham could accompany two Pickaxe agents [NKVD agents to be parachuted behind German lines by the RAF] to Bari before proceeding on to the United Kingdom: he had been in the Soviet Union for fifteen months without a break. Hill requested that Graham be returned after four weeks’ leave, something that was not fulfilled. Graham did, however, soon leave Moscow, unaccompanied.

His leave must have been extended while SOE discussed the future of the troubled Moscow Mission, where co-operation with the NKVD was steadily breaking down. A very enigmatic and incomplete telegram from Hill to London, dated October 30, 1944 (in HS 4/334) suggests that, while Captain Maclaughlin (D/P 106) was currently in Moscow, the NKVD would prefer to have Captain Graham (D/P 103) return to his post. Graham (recently promoted to Major) was reported to be with Hill at the latter’s farewell dinner in Moscow in May 1945, and had apparently returned from another visit to London with him in March. The father could therefore have been present at the birth.

Yet the actual birth certificate shows that Christopher John Graham was born on January 10, 1945. That would have required George to be in the United Kingdom in April 1944, which appears not to have been possible. [I plan to develop a stronger chronology for Hill’s and Graham’s movements after studying further files in the HS/4 series.] Irrespective of such irregularities, the birth of Jane Ann Graham followed after George’s demobilization in July 3, 1946, by which time George was described merely as ‘Journalist’. His skills as a Russian speaker meant that he eventually found a position with the BBC. Bush House records indicate that he worked as Assistant Programme Organiser in the Russian Section of the Eastern European Service of the BBC from 29 December 1947 to 31 October 1949. Yet no reference points to any particular contribution he made: it appears that the Russian Section had problems attracting suitable staff, and the issue of what tone talks should take in the climate of the intensifying Cold War must have been contentious.

And then the Grahams’ life was shattered by an unspeakable personal tragedy. The Buckingham Free Press reported on December 2, 1949 (a Wednesday):

When the offside rear tyre of an articulated lorry burst at Dashwood Hill, near High Wycombe, on Sunday afternoon, the lip of the wheel disintegrated, flew across the road and struck four-years old Christopher John Graham, who was walking on the footpath with his mother, his small sister, and another child.

Christopher, who lived at 8, King-street, Piddington, was seriously injured about the face and neck and died on arrival at High Wycombe War Memorial Hospital.

This must have been a devastating event for George and Edith. Yet stresses had already begun to appear. According to the news item, Mrs Graham had attended the inquest to identify the body, and stated that her husband ‘was formerly head of the Eastern European broadcast service of the B.B.C. at Bush House, London, but had not been working for some time because he was suffering from a nervous breakdown’, adding that he was ‘at present living at Tunbridge Wells’. This assertion was obviously not quite accurate: Edith exaggerated her husband’s role in the service, and did not point out that his official termination had occurred between the date of the accident and the inquest itself. Maybe George did not tell her the full story of his work at Bush House.

A further coroner’s report was issued a week later, adding some bizarre touches:

Mr. R. E. M. Proust, a superintendent of Colonial police, of 5 Albert Mews, N.W.1, said he was driving a car overtaking the lorry, which was going at five to seven miles per hour, when there was a loud bang and he heard a child screaming. He had noticed nothing unusual about the rear of the lorry.

Police-sergeant E. Smith said the lorry was loaded with aluminum ingots which were evenly spaced, and the load was well within the legal limits.

Should these reports be taken at face value? What were the chances of such a freak accident? How was it that a police officer happened to be overtaking the lorry at the exact time of the accident? And why would Proust trouble himself to have taken a look at the rear of the lorry if it was merely a routine encounter? What with the timing, and the precision, one has to consider that some devilish attempt had been made to scare (or punish) the Grahams, but the circumstances are beyond analysis.

Yet Graham’s nervous breakdown showed that he was probably being threatened. My Briger informant again: “When he retired he lived at the Legat School in Tunbridge Well for a while and went mad as he thought everyone was trying to kill him. He used to come out only at night and run from tree to tree in case he was spotted. Ending up paranoid, he didn’t know if he was Russian or English or which language he was speaking.” This speaks of justifiable terror, but, if the family lore is reliable, also provocatively indicates that George believed that his oppressors were not just the Russians, who were presumably dissatisfied with his performance after he returned to the United Kingdom. Did his erstwhile employees in SOE/MI6 likewise want him silenced, since he knew too much about the security breaches in Moscow and Kuibyshev?

Perhaps not surprisingly, the marriage broke up. On August 16, 1955, George re-married, in Willesden. George may have been rehabilitated somewhat by then, as his residence at the time of the marriage is given as 5 Greenhurst Road, N.W.2. His bride, who lived in Edgware, was Valentina Ivanov, at the age of fifty-four ten years older, whose previous marriage had also been dissolved. She was described as ‘Cook-manageress’, the daughter of Constantin Kikin, a Russian army general. She had studied in Belgrade in the 1920s and then worked in Yugoslavia as a teacher, where she married and had a daughter. She was deported to Germany during the war (and must surely have suffered there) before making it to the United Kingdom. At some stage George and Valentina returned to the support mechanisms of the Legat institution. Their home from May 1964 (at least) was 17 Sutherland Road, Tunbridge Wells, by which time Valentina was working as a needlework teacher at the Legat School, and as an art and craft teacher at Rosemead School in Tunbridge Wells. The official witnesses at the ceremony had not included George’s mother: they were his loyal aunt, Nadine, and his step-father, Alexander Shidlovsky.

Of the extended family, George’s father died first, in 1957. Next was George himself, of hepatic cirrhosis on February 8, 1968, at the house in Tunbridge Wells. Alexander Shidlovsky followed him on March 26, 1969, succumbing to coronary thrombosis and arteriosclerosis, nearby in Tunbridge Wells. Nadine died in 1971, and her sister Olga followed her on November 14, 1975, with cardiovascular degeneration given as the cause. Edith Graham died at her daughter’s house in Horsham, Sussex, on November 2, 1980, with cause of death given as myocardial infarction and coronary thrombosis and atheroma.

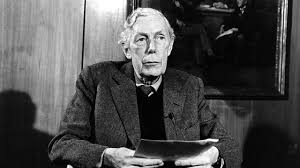

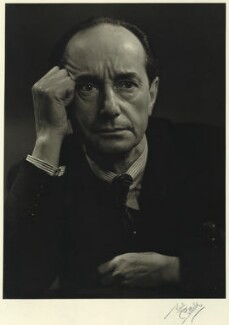

Paul Dukes did not enjoy a happy ending, either. The photograph used in his ODNB entry, taken in 1948, shows a man seemingly beset by a world of worry. He married his second wife, Diana Fitzgerald, in 1959, and died in Cape Town, South Africa, on August 27, 1967. In a local obituary notice, Lady Dukes was reported as saying that her husband’s death ‘was a direct result of serious injuries he suffered in a car accident in England last year’. The notice added: “They had come to South Africa hoping the climate would help him recover.” Was it a suspicious road accident, like that which took the life of former MI5 officer Tomás Harris in Majorca in 1964? In any case, there was no Omnipotent Oom around to save Paul Dukes. He left £374 in probate.

10. Summing-Up:

This is a story of exploitation, stupidity and secretiveness. It points to a massive breach of security that would have put any putative ‘ELLI’ problem in London in the shade. MI6 and MI5 later recognized that their premises in Moscow had been electronically bugged, but an admittance that the Soviets had had access to their ciphers and code-books would have knocked such goings-on into a cocked hat. Yet it is difficult to come to any other conclusion.

Serge Leontiev was exploited – by Paul Dukes, who seemed to have selected Serge as a surrogate for his own thwarted ambitions, and by the officers in MI6 and SOE (and maybe politicians, too) who connived with the misbegotten plan to send him into Soviet Russia without a serious thought of the consequences. The inevitable devilry by the NKVD occurred, and George Graham (as he now was) was left hanging high and dry.

The naivety shown by the officers of MI6 and SOE (surely Menzies, Dansey, Gubbins, Boyle and Hambro) over the NKVD’s methods, and how they would treat an obvious White Russian inserted into the Moscow mission, is breathtaking. Any perceived lack of acuity in poor George Graham was dwarfed by that displayed by those giants of ‘Intelligence’. The failure to consider essential security procedures and techniques reflects an amateurism that equals the appalling carelessness over German Funkspiele against SOE networks, primarily in the Netherlands and France, during the war.

If Guy Liddell had not made that single entry in his Diary, or if the censor had been careful enough to redact the name of Graham/Leontiev, presumably none of this story would have emerged. And SOE and MI6 were sensible in stifling the details, as the revelations would have caused damage far beyond their own province. Relevant papers were surely destroyed, and it is possible that all the ‘SOE advisers’ at the Foreign Office were shielded from these events. Thus the secrecy behind them is no conventional cover-up: it just represents one of probably many intelligence mis-steps that were capably buried at the time. Yet the story I have laid out above proves that the final word on any incident can never be written. I direct that message specifically at you, Mr. Mark Seaman.

New Commonplace entries can be seen here.