The Review

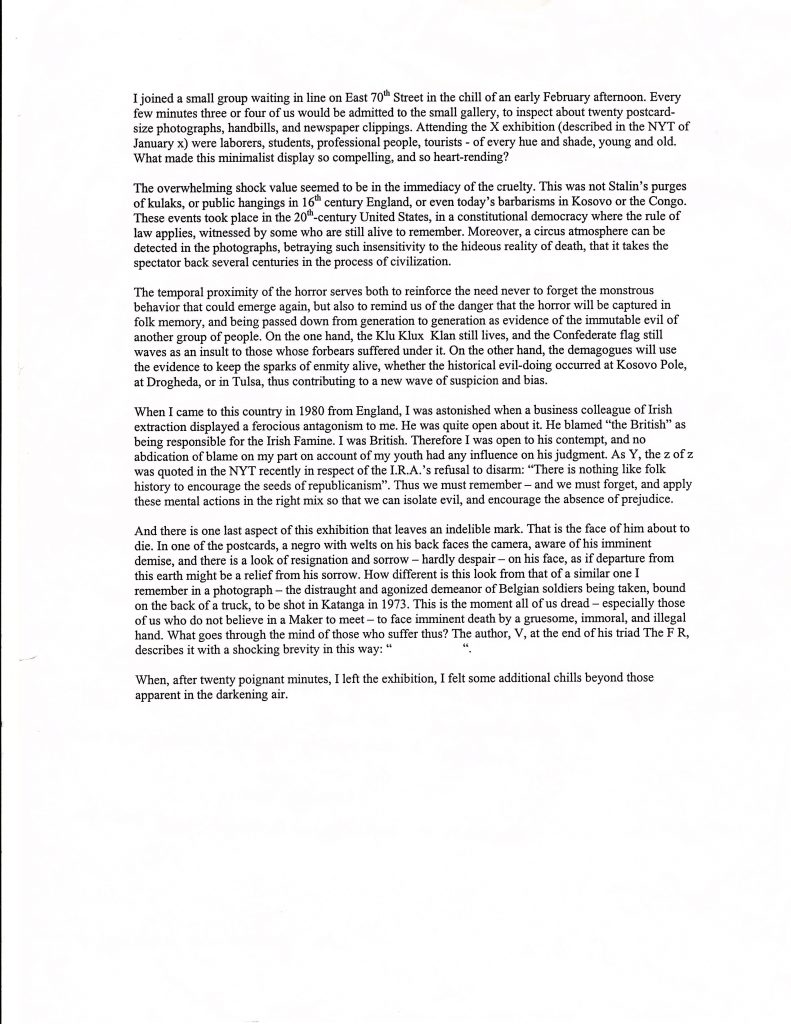

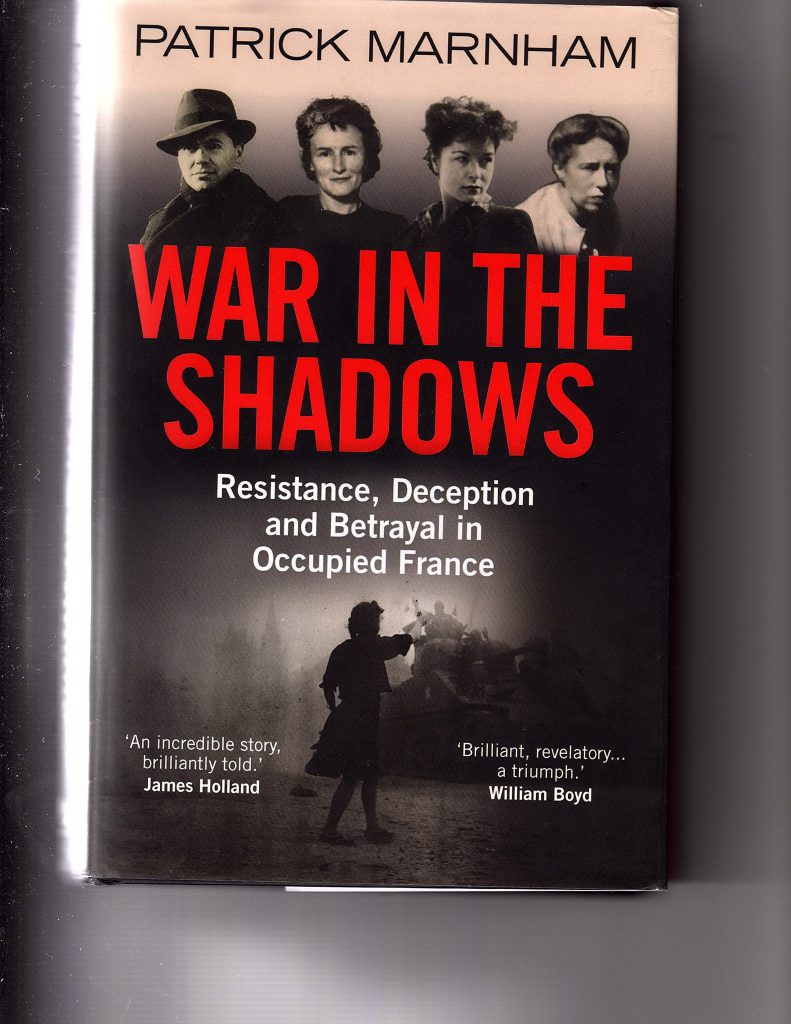

I must confess that, while I am a keen subscriber to the Times Literary Supplement, I do skim over many of its book reviews. For instance, in recent months there has been a surfeit (not just in the TLS, but in the press generally) of lengthy reviews of biographies of such tiresome persons as Philip Roth, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, and one can digest the sordid aspects of their lives only so many times. Occasionally, something startling appears, and a review in the issue of December 4, 2020 especially caught my eye. It was headlined ‘Lost in a hall of mirrors: Did Britain betray Jean Moulin?’, and it covered a publication by Patrick Marnham, titled War in the Shadows: Resistance, deception and betrayal in Occupied France’, which offered new theories about the fate of the illustrious SOE (Special Operations Executive) emissary and resistance leader. The review was written by Nigel Perrin, described as ‘a lecturer at the University of Kent’, and author of a book about SOE agent Harry Peulevé.

My interest was piqued on several fronts. Decades ago I had read such popular biographies as The White Rabbit (of ‘Tommy’ Yeo-Thomas), and Carve Her Name With Pride (of Violette Szabo), but had never properly internalized exactly what was going on with SOE and its various divisions. When I retired, I started catching up with my reading, and eagerly absorbed such SOE-related works as Leo Marks’s Between Silk and Cyanide, and Sarah Helms’s A Life in Secrets, about Vera Atkins. Yet it was only when my study of wireless interception in WWII became more intensive that I read the more serious histories of SOE, such as those by William Mackenzie and M. R. D. Foot, as well as a number of not utterly reliable biographies and memoirs that handled the use of wireless by agents in occupied Europe, and the efforts of the Gestapo to intercept and locate their transmissions. Nevertheless, I would have had to admit that I still had only a sketchy idea of the manner in which many of the Allied networks in France had been penetrated and broken down, in contrast to what I had learned about the notorious ‘Nordpol’ operation in the Netherlands.

Patrick Marnham was a name I recognized, mainly in association with the magazine Private Eye. He had been heavily involved with the Jimmy Goldsmith case, and had written a history of Private Eye (a copy of which I own) that apparently infuriated its editor Christopher Booker, an achievement that must constitute a special irony, I imagine. Marnham was obviously a sound investigative journalist, but I had not got round to reading any of his other books. And then there were the compelling code phrases ‘hall of mirrors’, ‘deception and betrayal’, that drove the story right into my territory, with echoes of the ‘wilderness of mirrors’, as imagined by James Angleton, and the betrayals inherent in John le Carré’s novels.

The review was quite scathing. Marnham had written a book on Jean Moulin in 2000 (The Death of Jean Moulin), where he had investigated the murky background to the way in which the first President of the National Council of Resistance occupied that post for only two months before being betrayed and then tortured by the infamous Klaus Barbie, and then dying in captivity on July 8, 1943. The circumstances of the betrayal of Moulin and his comrades are controversial, and still hotly debated, but Marnham’s new book (so Perrin stated) suggests alarming connections between the death of Moulin and the demise of another SOE network named PROSPER, led by the eponymous Prosper, namely Francis Suttill. As Perrin described it: “If Moulin’s demise is a complex subject, the downfall of Prosper is positively labyrinthine.”

Marnham’s fresh research and conclusions were prompted by veiled hints provided to him in writing by an anonymous character he calls ‘the Ghost’, sent to him after the publication of his earlier book. The Ghost encouraged Marnham to investigate links between Moulin and Prosper. And this is where my interest rapidly swelled, as Marnham’s claim is that the PROSPER network was sacrificed as part of a scheme to convince the Germans that an invasion of France would occur in 1943 (when Churchill, Roosevelt and all their planners knew that it could not possibly be attempted until 1944). Thus was the COCKADE deception plan designed, a piece of which was Operation STARKEY – a project to keep enough of Hitler’s forces occupied in France by convincing them that the cross-Channel assault would occur in September of that year. It was also useful as a sop to Stalin, who had become increasingly frustrated by the misleading promises that his Allies had made to him about opening what Stalin called ‘the Second Front’ (an inaccurate term that he had managed to have picked up by his friends in the West).

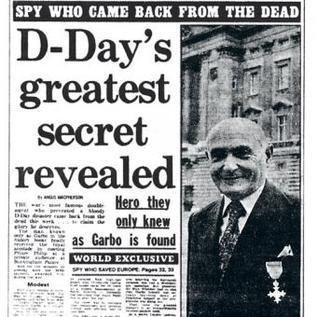

Key to the whole story is the role of one Henri Déricourt, rather inaccurately described as a ‘double agent’, who turned out to be a down-and-out traitor. Déricourt arrived in England in September 1942, was recruited by SOE, and then trained as an ‘air movements’ officer. He was parachuted back into France in January 1943, but was soon informing the Gestapo of everything that was going on, so that the Nazis were gradually able to mop up the whole network – while probably ascribing their success to detection of illicit wireless. Two valiant SOE officers, Francis Suttill, and his radio operator, Gilbert Norman, were captured and later executed, as well as scores of members of the French resistance. Yet Marnham’s most challenging assertion is that, behind the general scheme to delude the Germans, Claude Dansey of SIS was an active agent in the operation, and had even taken Déricourt under his wing in 1942, in the knowledge that he had already been recruited by the Gestapo.

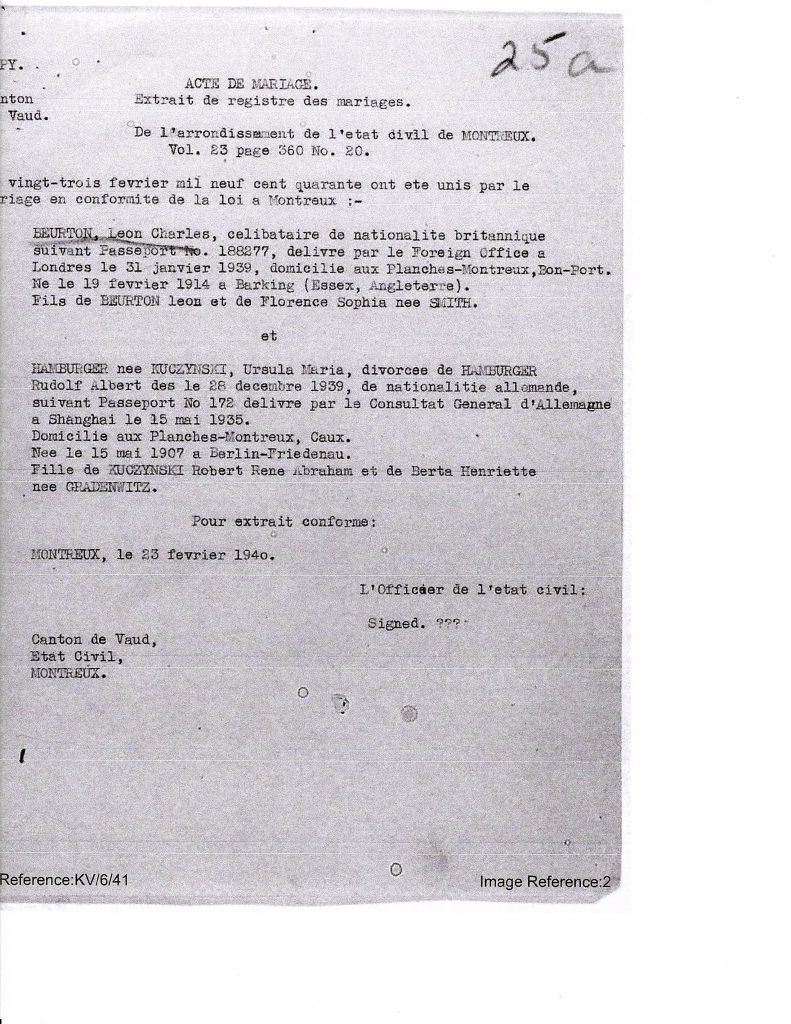

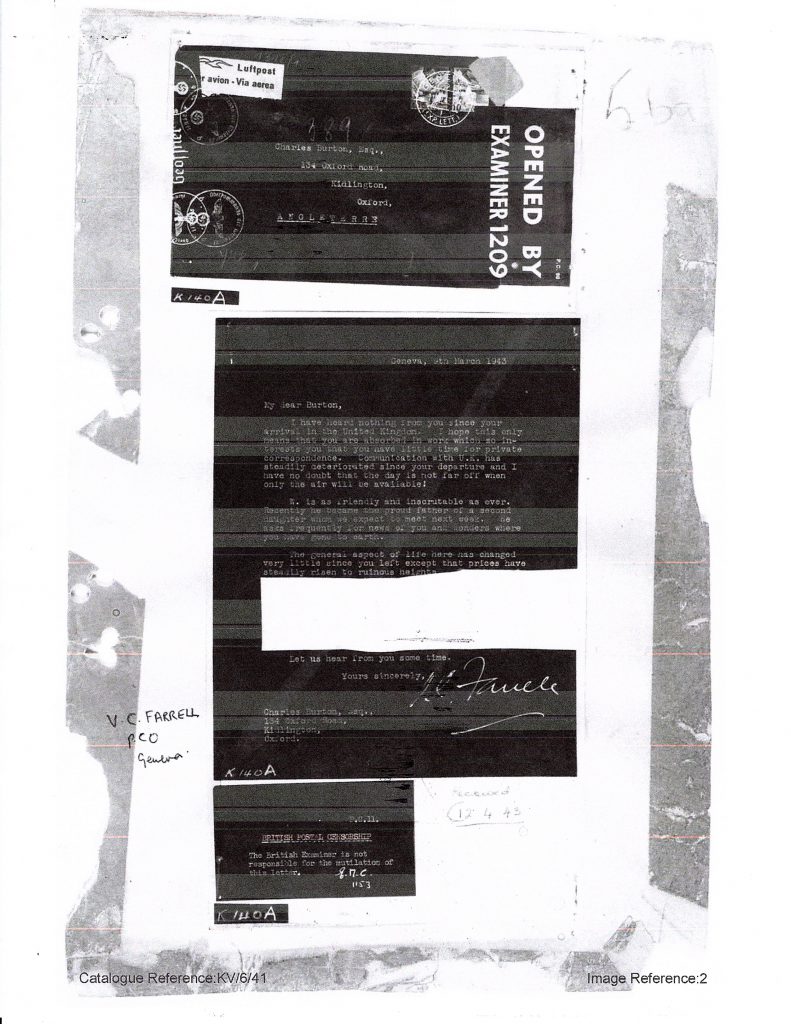

Now, Claude Dansey’s antipathy to SOE, and his fear that its madcap saboteurs would interfere with SIS’s proper intelligence-gathering, is a well-known fact, but it is a much more serious charge to suggest that Dansey was actually responsible for more malicious and destructive initiatives. According to Perrin, Marnham goes further. He claims that Nicolas Bodington, an SOE staff officer who, in July 1943, after the arrest of Prosper and four other F section agents, went to Paris to investigate the Prosper affair (and made it back unscathed) was an SIS ‘mole’. In addition, Dansey was reputedly also involved in Moulin’s arrest, since he had used an agent Edmée Delettraz, ‘a courier for an SIS network based in Geneva’, who had been arrested in Lyon, and thereafter agreed to work for Klaus Barbie. Readers who are familiar with what I discovered about SIS and Victor Farrell in Geneva, and his mysterious communications with Len Beurton, (see Sonia and MI6’s Hidden Hand), will perhaps understand why this particular story suddenly gained some new appeal for me, with my curiosity over exactly what Farrell and co. were up to in 1943.

This was all too much for Perrin, who did not see the evidence required to support Marnham’s thesis. “Amid a wealth of conjecture, supposition and insinuation, one is hard pressed to find any solid evidence to support the extraordinary claims being made”, he wrote. Perrin saw all the mysterious riddles emanating from the Ghost as leading readers down a pointless rabbit-hole, and regretted openly Marnham’s exploits into ‘the realms of speculation’. I made a mental note that I should read the book at some stage, but had other fish to fry at the time.

The Correspondence

What followed was a provocative exchange of letters in the periodical. I always turn first to the Letters page of the TLS when I receive my copy (as I do with the London Review of Books), as some of the letters turn out to be far more engaging than most of the book reviews. In fact, I wish both magazines devoted more space to letters from subscribers. Admittedly, many of them contain only very obscure or pedantic points, but a few present lively new perspectives on matters arising from the reviews themselves. (As an aside, let me point out that the LRB would do well to focus on its mission rather than dedicating so much space to long essays on political matters. That is part of the stylistic legacy of the recently retired editor Mary-Kay Wilmers, but in the past few years I have become heartily fed up, for example, with pages occupied by yet another diatribe telling me how awful Donald Trump is. I could understand why the left intelligentsia wanted to let off steam on this matter, but what on earth had it to do with a London-based Review of Books?? And the pattern continues.)

To return to the correspondence. First appeared a predictably peeved rebuttal from Mr. Marnham, on December 18. I found it persuasive. He carefully dismissed Perrin’s complaints about a lack of ‘solid evidence’, painstakingly referring again to the documents that he had found that proved links between Claude Dansey of SIS, T. A. Robertson of MI5 (the most prominent member of the Double-Cross Committee), and the Gestapo agent Henri Déricourt. He corrected Perrin for ascribing to him a statement by M. R. D. Foot, and reminded readers of his own chapter that painstakingly exposed some of Professor Foot’s errors. He alluded to an admission by Vera Atkins, made in France after Déricourt’s trial (at which Nicolas Bodington appeared as a defence witness), and not previously published in the United Kingdom, that Bodington, the F Section officer that she had worked alongside during the war, had ‘probably worked for SIS’. On the link between Prosper and the arrest of Moulin Marnham was a little more guarded, implying that much of the story remained problematic. This reply certainly reinforced my wish to read his book.

Three weeks later, a rather emotional letter appeared under Francis J. Suttill’s name. Mr Suttill stated that he had written a book titled Shadows in the Fog, published by the History Press in 2014 that covered the wartime activities of his father, Major Francis Suttill. Now, that was a very poignant revelation: it is impossible to understand the particular grief that Francis Suttill must have suffered, having never known his father properly (he was born in 1940), and I am filled with admiration for the many years he had spent investigating the events that led to his father’s arrest. Yet no historian should be exempt from a ruthless inspection of any new evidence that appears, or not be prepared to re-analyze his or her conclusions in the light of such discoveries.

Mr. Suttill came across as a little intemperate. Mr. Marnham’s claim was ‘nonsense’, he declared, and he further categorised War in the Shadows as a ‘novel’. Yet he offered no detailed evidence to support his case, merely suggesting that his own book was the final and irrefutable account of what happened, and expressing his belief that Marnham must have ignored what he wrote since it did not fit in with his theories. He explained the appearance of Bodington at Déricourt’s trial as the repayment of a debt, since Déricourt had saved Bodington’s life in 1943. Suttill completed his script, rather oddly, with the following statement: “Jack Agazarian was betrayed by three SOE agents. His fellow wireless operator, Gilbert Norman, then in the hands of the Gestapo, set the trap. Bodington, despite knowing it was a trap from Déricourt, ordered Agazarian to go to the rendezvous as their host at the time later testified.” For me, this stirred up the pot even more mysteriously rather than clearing up any unfinished business. Suttill certainly did nothing to unravel the ‘labyrinthine’ tangle that Perrin had alluded to: if anything, he hinted at conspiracies that called for the kind of plausible theorizing that Marnham was engaged in.

Alongside Suttill’s letter appeared a longer submission from Nigel Perrin. He started his riposte with a defence of ‘official’ history. While he acknowledged that new evidence might be able to ‘overturn’ it, this was perhaps not the strongest card he could play, given the established reputation of various ‘official’ and ‘authorised’ histories for selectivity, obscurity – and error. He then went on to question the solidity of Marnham’s evidence, claiming to be familiar with the detailed items that Marnham cited, but minimising their significance, and dismissing Marnham’s case as purely speculative. It was clear that the public debate was winding down, and close inspection of Marnham’s text (and maybe the archival material quoted, too) would be necessary for the independent reader to make a proper judgment. Marnham was afforded a last short opportunity to reply, in which he repeated his claim that Perrin was misquoting him, and conceded that an informed assessment on his claims would have to reside with the interested reader. Rather surprisingly, Suttill was given a last bite of the cherry, where he merely disputed the number of casualties arising from the betrayal of the Prosper circuit.

Other Reviews

I thus ordered the book, and, while waiting for it to arrive, took a look at one or two other reviews. Now, I am usually quite cautious in my consideration of book reviews in this sphere. I want to know what the credentials of the reviewer are for having any authority to offer judgments on such works. My dismay over the many amateurish assessments of Ben Macintyre’s Agent Sonya was a prime motivation in my accepting an offer to write a review for the Journal of Intelligence and National Security. I was pleased that, in the Times recently, one Oliver Kamm was on hand to give Anne Sebba’s fawning and inaccurate biography of Ethel Rosenberg the proper dismissive treatment it merited, despite the puffs from Philippe Sands and Claire Tomalin that the book displayed on its cover. (Not that the Rosenbergs deserved the death penalty, but they were guilty.) Moreover, if the book in question is one that focuses on topics close to my own domain of interest, I do not want my reactions to be swayed unduly by what professional critics have written.

I did inspect two reviews – one in the Spectator, and one in the Times. That in the Spectator (October 10, 2020) was a little perfunctory, provided by Allan Mallison, who is a former army officer, and writer of novels set in Napoleonic times. He combined his review with one of Helen Fry’s MI9, and he showed that he had no particular expertise in these matters. A good chunk of his review is taken up by direct quotation, he provides no detailed analysis while commending Marnham’s ‘painstakingly forensic’ approach, and he merely concludes: “This is a masterly analysis, impeccably presented.” This was good for Marnham, but the magazine should have commissioned the usually excellent Clare Mulley (who normally reviews such items on its pages) for this particular task. (I have just noticed that Mulley wrote a sympathetic review of Sebba’s biography in the Spectator of June 19, where she claimed that Ethel Rosenberg betrayed nobody! Adam Sisman echoes this stance in his evaluation in Literary Review.)

Roger Boyes, in the Times of November 9, provided a more serious analysis. Boyes is a staff journalist who has written books on Russian history, and he engaged with Marnham’s argument more expertly. He focused on the coincidence that Moulin’s arrest and the mopping up of the PROSPER network occurred on the same day (June 21, 1943), and explained how Marnham’s interest was spawned because, as a teenager, he had stayed for a while with the woman who had been the leader of the betrayed group. Boyes perhaps dwelled on her activities a little too much, but used that introduction to describe how the group’s regular sabotage operations were overtaken by the dropping of large amounts of armaments to be deployed to support the D-Day landings. The French Resistance was to be used to convince the Germans that they needed to maintain a strong force in the West.

“But it was a bluff that cost lives as the Germans cracked down,” wrote Boyes. Moreover, even though the Nazi general von Runstedt was fooled for a few months, the backlash from the lies and trickery endured much longer. Boyes commended Marnham for capturing all this intrigue with verve, but criticised him for his ‘relentless feuding’ with the official chronicler of SOE activities, the late MRD Foot, as if he had a personal animus against him. That remains to be seen: Foot was notoriously protective of ‘his’ story, and disliked any other historian treading on his turf. Boyes was also of the opinion that Marnham had not performed enough justice to the German side of the story.

His final assessment, however, was that Marnham did not promote unambiguously a strong conspiracy theory, but left the question of whether the British betrayed the French Resistance as part of a deception exercise for the reader to decide. Some (perhaps including Boyes) might consider that an evasion of responsibility, but I can sympathise with the dilemma, having placed myself in a similar position. Fresh evidence can frequently evolve and modify the conventional wisdom, but dogmatism is never appropriate, no final account can ever be written, and the open-minded historian can hope only that fresh evidence and fresh inquisitive students will allow a more accurate picture to be portrayed.

I was left with one very serious thought, however. Boyes quoted a minute of Churchill’s (of April 14, 1943): “Stalin not to be informed that 2nd Front is now cancelled.” (It was not clear at the time whether Marnham cited this instruction in his text. I later discovered that he does indeed quote it, on page 94.) Apart from the fact that my understanding has been that Stalin was well aware by the spring of 1943 that there would be no English Channel landings that year, this instruction showed extraordinary naivety on Churchill’s part. What with Stalin’s spies infiltrated in MI5, MI6, SOE, GC & CS, the Foreign Office, The Home Office, The Ministry of Information and probably other government institutions, it would have been practically impossible to prevent a ‘secret’ of that magnitude from reaching Stalin’s ears. (Not that Churchill realized that at the time, of course, but that is another story. Moreover, if it reached the Kremlin, it could have been passed surreptitiously on to the Germans.) That is another dimension of the ‘betrayal’ that Marnham reportedly covered – that Stalin would consider his Allies even more perfidious because he gained access to intelligence that they did not pass to him on official channels – just like the Enigma decrypts. I experienced an increased interest in learning how Marnham dealt with these issues.

The Book

War in the Shadows arrived, and it came with some impressive blurbs on its back-cover, from James Holland, Antony Beevor, and William Boyd: ‘an incredible story brilliantly told’ (Holland); ‘a brilliant and revelatory work of modern historical investigation’ (Boyd). Yet it had to wait a while before I finished reading a series of books related to MI5 after the war, and to the Gouzenko affair, that had been lined up in series. Unlike some of those items I had just completed, however, Marnham’s book proved to be what I believe is referred to in the popular press as a ‘page-turner’.

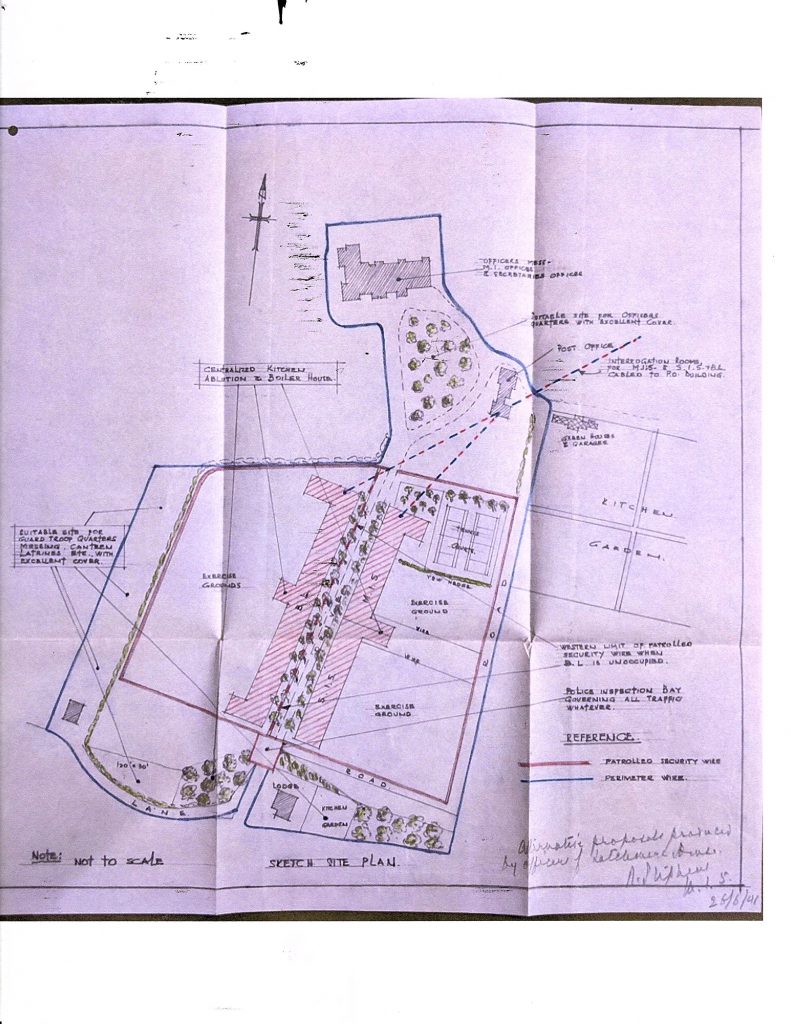

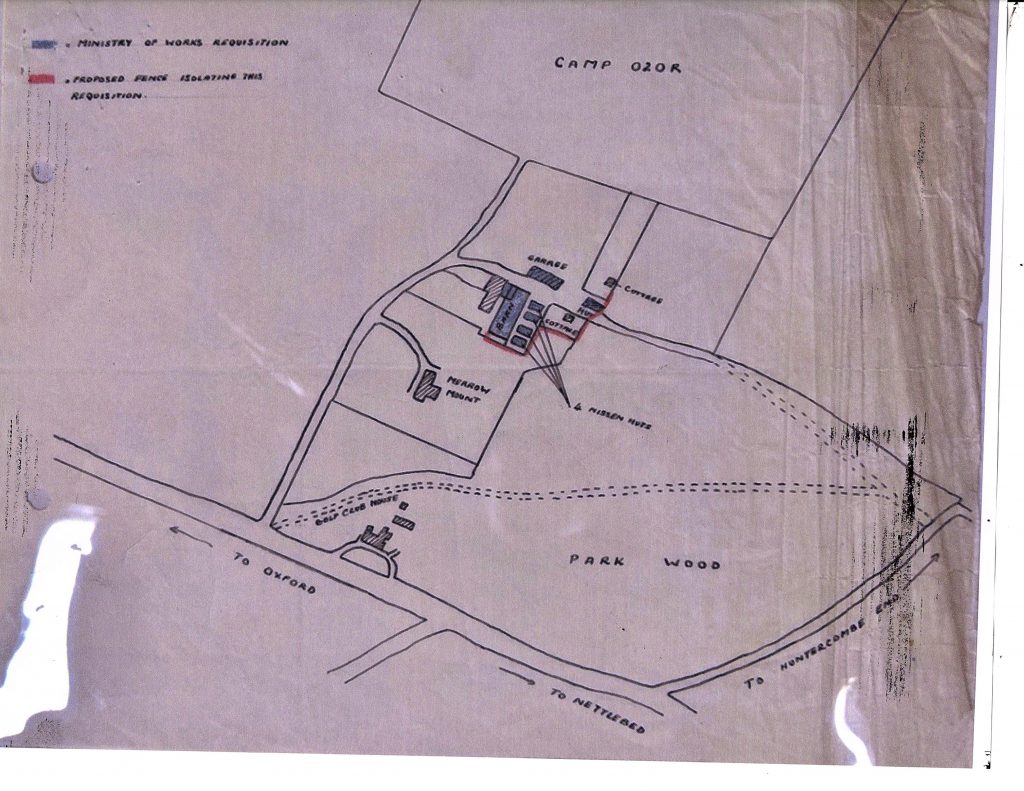

Marnham approaches his main topics carefully and methodically, explaining the circumstances of his stay in the Sologne in 1962, and his becoming acquainted with Souris (Anne-Marie de Bernard), one of the heroines of the story, and how she and her friends and family helped refugees after the fall of Paris. He outlines the background to the war in 1940, and what prompted Winston Churchill to set up the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Yet SOE’s beginnings were infected with conflict from the start: by opposition from SIS (MI6), which was focussed on intelligence-gathering, not sabotage, and resented SOE, and from rivalries within SOE itself, as de Gaulle’s government-in-exile wanted control of French operations, and ended up running its own section (RF) alongside SOE’s native French unit (F).

The kernel of Marnham’s story is the tale of two parallel, and almost symmetrical, betrayals of SOE agent networks, at the end of June 1943. The first, in Paris, that of the PROSPER network, led by Francis Suttill and his radio operator, Gilbert Norman, was engineered by Henri Déricourt, a Gestapo spy who had infiltrated SOE to become the air movements officer for ‘F’. The second, that of the movement behind Jean Moulin, who was de Gaulle’s chosen leader of the resistance movement, occurred in Lyon. It was facilitated by the activities of Edmée Delettraz, a courier managed by Colonel Groussard, of SIS in Geneva, who was befriended by another Gestapo infiltrator, became his mistress, and led her lover’s police force to the place where Moulin was holding a meeting with resistance colleagues. Suttill, Norman and Moulin were just three of hundreds who were rounded up. All were tortured horribly. After brutal treatment by Barbie, Moulin died in transit to a German prison. Suttill and Norman were later executed.

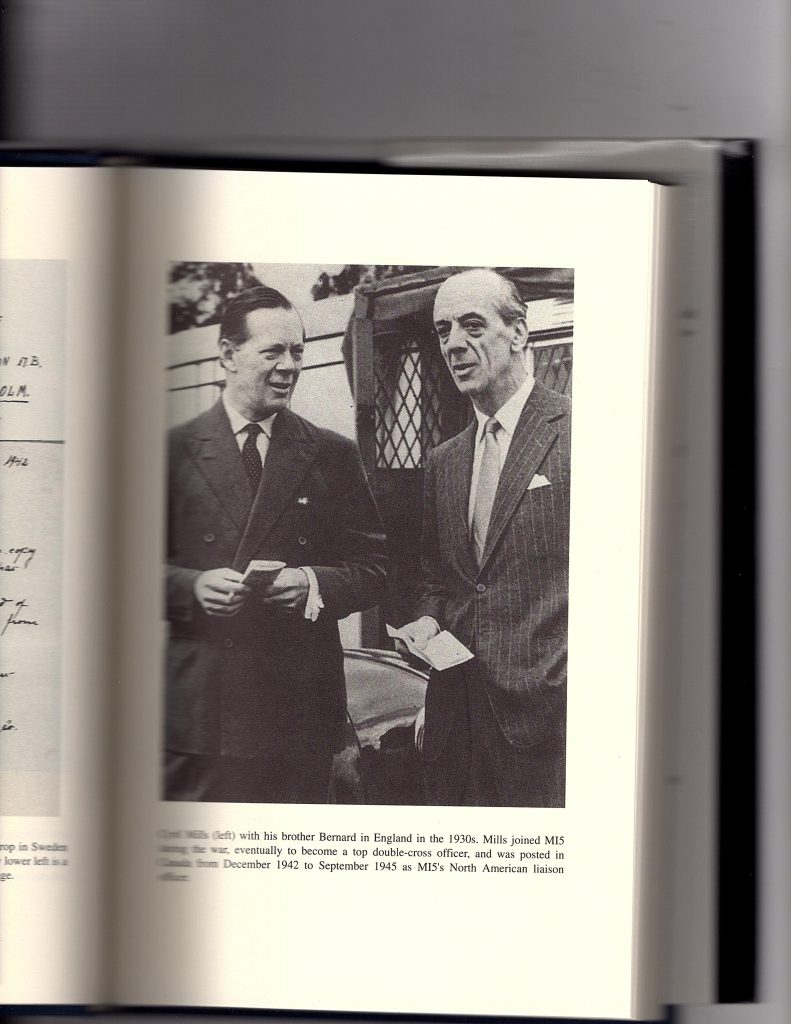

This might have been a relatively simple tale of incompetence and confusion, but Marnham makes a stronger claim (not the first to do so, incidentally, but the first to come up with more convincing evidence) that a malign, and plausibly evil, plot lay behind the betrayals. And the common element was Colonel Claude Dansey, the vice-chief and director of operations of SIS, who was apparently playing a furtive role in manipulating SOE. One of the officers in his Z intelligence network, Frank Nelson, had worked in Geneva before being appointed head of SOE in 1940. Nicholas Bodington, who was second-in-command of F Section, had been placed there from SIS, and undeniably was aware of Déricourt’s associations with the Gestapo in Paris, yet persisted in sending Suttill and Norman to their doom. Delettraz and Groussard worked for Dansey’s current representative in Geneva, Victor Farrell. Groussard likewise knew of Delettraz’s liaison with Robert Moog, the Abwehr officer seconded to the Gestapo, but encouraged further contact.

The reason for Dansey’s treachery against the SOE was a fierce regard for the strategic goal of convincing the Germans that a large-scale invasion of France was imminent. The scale of armaments drops, and feverish resistance activity, was designed, as part of the STARKEY ruse, to convince the Wehrmacht that a large force needed to be maintained on the Western Front, in order to make Stalin’s task easier. Marnham’s research indicates that the Double Cross Committee was aware of the deception. Yet why so many noble lives had to be sacrificed in this endeavour, and whether it was these events that convinced the Germans that an attack was imminent, is never properly explained by Marnham. He refers briefly to Churchill’s decision that the camouflage Operation SLEDGEHAMMER should proceed, and that Stalin should not be informed that the real invasion will not go ahead, but he does not explore the obvious paradoxes in that statement, or how it was undermined by Stalin’s network of spies. (SLEDGEHAMMER is not precisely described, and does not appear in the index.)

Here, I think, Boyes’s observation about ‘the German side’ has some merit. Marnham cites SOE: 1940-1945, the 1981 book by J. G. Beevor (who was an officer in SOE) to indicate that Hitler was persuaded that Allied invasion plans ‘had suffered a setback’, but uses an even older statement by Foot (1966) to suggest that von Rundstedt remained convinced that an assault in 1943 was likely. His thesis appears to be that STARKEY was (partially) successful because the Germans considered the invasion threat real, and may have concluded that they had been able to stifle it because the Paris Gestapo was able to destroy the guts of the French resistance. Yet, as he states, London considered it a failure: would a planned assault have been abandoned simply because of the effective German mopping-up operation? “In July,” Marnham writes, “the situation changed because the Sicily landings forced Hitler to fight on a real second front, and this took some of the pressure off the deception staffs.” This is a topic that deserves some deeper analysis.

Another area of imbalance is the purported equivalence of the Suttill-Moulin situations. Marnham asserts (p 226) that both Suttill and Moulin had been given the false impression, in the spring of 1943 that later landings ‘were likely, or at least possible’. Yet Suttill’s impressions were far stronger than Moulin’s. On page 96, Marnham states that, after his briefing in May 1943, Suttill had a new conviction in mind, namely ‘that the long-awaited allied landings were imminent’, and the entire Dansey plan revolves around that conviction. On the other hand, Moulin and General Delestraint (a rather mysterious figure, who is not fully fleshed out in Marnham’s account) were told in March that there was no plan to carry out landings before the end of the year, but that there remained ‘the possibility of establishing a bridgehead on French soil before the autumn of 1943’. Nevertheless, Marnham rather inconsistently presents Moulin, after his arrest, as harbouring ‘the misled belief that allied landings in Northern France might well be attempted within the following three months’, which is something of an overstatement, but also an equivocation. The levels of indoctrination were sharply differentiated, which prompts the reader to question the overall argument.

And, indeed, Marnham hints at an alternative motivation for the betrayal of Moulin. On page 221, Marnham suggest that the major reason for abandoning Moulin to the Gestapo wolves was the fact that he had become too successful and too powerful. He had successfully united the military and political arms of the Resistance movement into one body, and thus significantly increased the influence of the detested de Gaulle. He had also quashed the Communist element in the resistance, which the leftish SOE considered critical for the coming engagements. Therefore he had to be sacrificed. This may also have been a genuine ambition of Dansey’s, and thus does not undermine the overall story of his mischief, but it weakens Marnham’s major theme of a common military deception exercise directed through Suttill and Moulin.

Indeed, as the story progresses, it does become more difficult to track the cast of characters and their various roles, both official and in subterfuge, and their explanations of their activities. The task is not helped by a rather sparse Index, and the annoying lack of relevant page-numbers at the head of each Notes page. For example, I wanted to explore when it was that Bodington and Dansey (who engineered Déricourt’s entry to SOE, bypassing the normal channels when Déricourt had provided a false account of his escape to Britain) had first learned that he was working for the Germans. I wanted to go back and trace Déricourt’s recruitment by the Gestapo, and his various encounters with his handler, Karl Boemelburg. But ‘Gestapo’ has only one sub-entry under ‘Déricourt’, and there appear no sub-entries for ‘Boemelburg’. Thus the inquisitive reader has to go back, re-read whole chapters, and make his or her own annotations to develop a particular case-history. Likewise, too many events are left undated: Marnham presents a useful chronology at the front of his book, but the text itself could have been sharpened up in several places to make matters clearer.

I also believe that Marnham uses the terms ‘double agent’, and ‘triple agent’ a bit too carelessly. Any agent who starts to have regular communications with the enemy is essentially a lost resource. His or her allegiance remains not with a cause or, but solely to personal survival – such as with SNOW and ZIGZAG in Britain’s Double Cross operations. It is beyond the ability of most mortals to maintain consistent fictions with more than one master. And therein lies much of the hopelessness of Dansey’s mission, if indeed that was what it was. He may have believed that he was controlling Déricourt in support of his greater goal, and using him as a ‘double agent’. As I have explained elsewhere (https://coldspur.com/double-crossing-the-soviets/) , ‘double agents’ (or ‘controlled agents’) can be successful only when their masters have exclusive and complete control over their actions, movements, and communications.

But Déricourt was never a double-agent, as Marnham suggests he became in January 1943, after he renewed contact with Boemelburg (p 251): he was an out-and-out spy who infiltrated himself into SOE, and remained loyal to his cause. It was he who was controlling Bodington, and the proof of Bodington’s delusion was his willingness to appear at Déricourt’s post-war trial and state that he had essentially instructed Déricourt to stay in touch with the Germans, thus saving Déricourt from the hangman. On page 276, Marnham puzzlingly claims that Déricourt was ‘of course a classic candidate for a deception operation, a Gestapo agent unmasked on arrival in England’. I would say that he was nothing of the sort: SIS and SOE had no means of gauging his true loyalty, and they had no control over his communications. It consisted of a colossal misunderstanding of what ‘turning’ implied. It is not clear how or why MI5’s Double Cross committee, which was highly cautious in approving ‘controlled agent’ candidates, sanctioned the process.

Moreover, the psychology of the deception yearns for analysis. Bodington decided to advance Suttill’s work, and send him on another mission, even though he knew of Déricourt’s associations, and Suttill (who had suspicions about Déricourt) was under the impression that an invasion would follow soon. (Marnham informs us that it was Bodington who, before the war, actually introduced Déricourt to Boemelburg. Nigel West has pointed out, however, that this assertion, by Robert Marshall, is not verifiable.) Did Dansey and Bodington expect Suttill to collapse under torture, and betray the existence of a phoney attack? And were they thus thwarted by Suttill’s bravery? On the other hand, Norman, who tried to indicate that he was broadcasting under control, and omitted his security code, was rebuked by SOE in London, and thus brought to despair, agreeing to reveal the names in the network to the Gestapo. And what about Déricourt? Did he wonder why his meetings with the Gestapo were tolerated, and suggest to his masters that a clumsy deception campaign was under way, or was he completely amoral, ready to align himself with the probable winner (as Marnham intimates)? Did Déricourt ‘save Bodington’s life’ in 1943 (as Francis Suttill claimed) by insisting that the Gestapo let him escape? Marnham records the facts of this extraordinary series of events, but they raise some serious psychological questions. Perhaps they are candidates for a deeper treatment by Tom Stoppard, or someone similar.

There is much to admire in Marnham’s methodology. I found his criticisms of Foot incisive, but scrupulously fair. On two occasions (p 171 & p 259), he rightly calls Foot to task for displaying what I call ‘Professor Hinsley Syndrome’ – bringing up what is presented as a rumour (without explaining its source), and then blandly discrediting it without introducing a shred of evidence to show why that should be so. I can also appreciate from experience Marnham’s painstaking trawl through the archives, dealing with grossly weeded files, looking for loopholes, matching possible names to redacted references, integrating information from multiple sources, and drawing on his deep knowledge of surrounding events.

Overall, Marnham has produced an impressive and convincing, if not conclusive, account of a very murky business. He could have been a little more rigorous in his final analysis, I believe. Yet why Suttill and Perrin should have taken such an emotional objection to War in the Shadows, I cannot imagine. To categorize it as a ’novel’ is simply insulting, when both writers would have done better to study the details, applaud Marnham’s ability to exploit the archives, and then themselves make their contribution to an evolving work of history. Would Suttill have preferred the attribution of his poor father’s loss of life to simple incompetence, rather than to a malevolent spirit who was out of control? I do not know. It is all very strange.

Yet, as the regular reader of coldspur may already have concluded, my curiosity was rapidly ratcheted up. Colonel Dansey and Victor Farrell feature dominantly in my account of Sonia’s miraculous egress from Switzerland to the United Kingdom, and my assumption that Dansey believed that he could thereafter manipulate her. My original reactions were heightened and encouraged. Were these operations in some way related?

The Aftermath

I decided that I needed to get in touch with Mr. Marnham. Accordingly, I sent an email to his publisher, requesting that he pass on a message expressing my interest. I referred to my research on Dansey and Sonia, and gave him the coldspur url. I was very gratified to receive a prompt response, where the agent promised to forward my message.

The very next day, I received a very positive response from Mr. Marnham, which ran as follows:

I hope you are well and wish to thank you for contacting me about ‘War in the Shadows’. I am very glad you were interested in my book.

I have been looking through the impressive research you yourself have published on ‘Coldspur’, and much regret that I was not aware of this when I was still at work.

The papers you have published are very extensive and I will be able to absorb your theories properly in the next few days.

The clear link and chain of command you have established between Dansey and Farrell, and the astonishing evidence of their role in the success of Agent Sonya, provides considerable support for my own more tentative theories. I was of course delighted to read it.

You seem to be in North Carolina at the moment but I do hope this will not prevent us from exchanging views and lines of enquiry. I am just completing work on revisions for the paperback edition of ‘War in the Shadows’ and with your permission would like to refer to some of your conclusions in an Afterword.

I was naturally delighted with this response, and encouraged Mr. Marnham to use my research as he felt fit. We have communicated occasionally since then, and I eagerly await the appearance of the paperback version of his book. He has given me some comments on Francis Suttill’s account of Prosper, and I have subsequently ordered the book in the hope that I might better understand what Suttill’s particular concerns and grievances are, and why he disagrees so violently with Marnham’s analysis.

It is an extraordinary pattern of activity by Claude Dansey. The fact that he could meddle so influentially in so many places, all apparently under the strange belief that he could manipulate hostile agents (both German and Soviet) to Great Britain’s advantage, is something that the historians have overall overlooked. The connection with Archie Boyle is also particularly poignant. Boyle was responsible for overall security within SOE, and Marnham points out that Dansey and Boyle (who was an Air Commodore) had previously worked together. As Director of Air Intelligence, Boyle sat on the W Board, where Dansey sometimes deputized for Menzies. Keith Jeffery, in his authorised history of MI6 (to which Marnham briefly refers), wrote that Boyle had been the Air Ministry’s candidate for Chief of SIS in 1939, and that in September 1941 he and Dansey ‘took charge of the circulation of all information from SIS to SOE’. Using evidence from SIS files (which we common-or-garden historians are not allow to see), Jeffery claimed that ‘Boyle was respected and trusted in SIS and got on particularly well with Menzies, Dansey and Vivian’.

Moreover, Marnham attributes Boyle with a significant role in recruiting dubious candidates to SOE. He strongly suggests that Boyle had a hand in bringing Bodington into SOE (page 258), and on page 264 offers the following startling commentary: “An SIS ‘spotter’ at the LRC (London Reception Centre) quickly identified Déricourt as a German agent and turned him. His previous connection with Bodington was established and he was introduced into SOE (as Bodington had been) by Air Commodore Boyle or possibly by André Simon.” Yet this evidence must be questionable: apart from the unlikelihood of a German agent’s being casually ‘turned’ at the LRC, Marnham uses Jeffery (page 366) as a source for his claim, but while Jeffery states that an SIS spotter in May 1941 reported that he had recruited twenty-eight agents, and passed on five further names, Déricourt is not specifically identified.

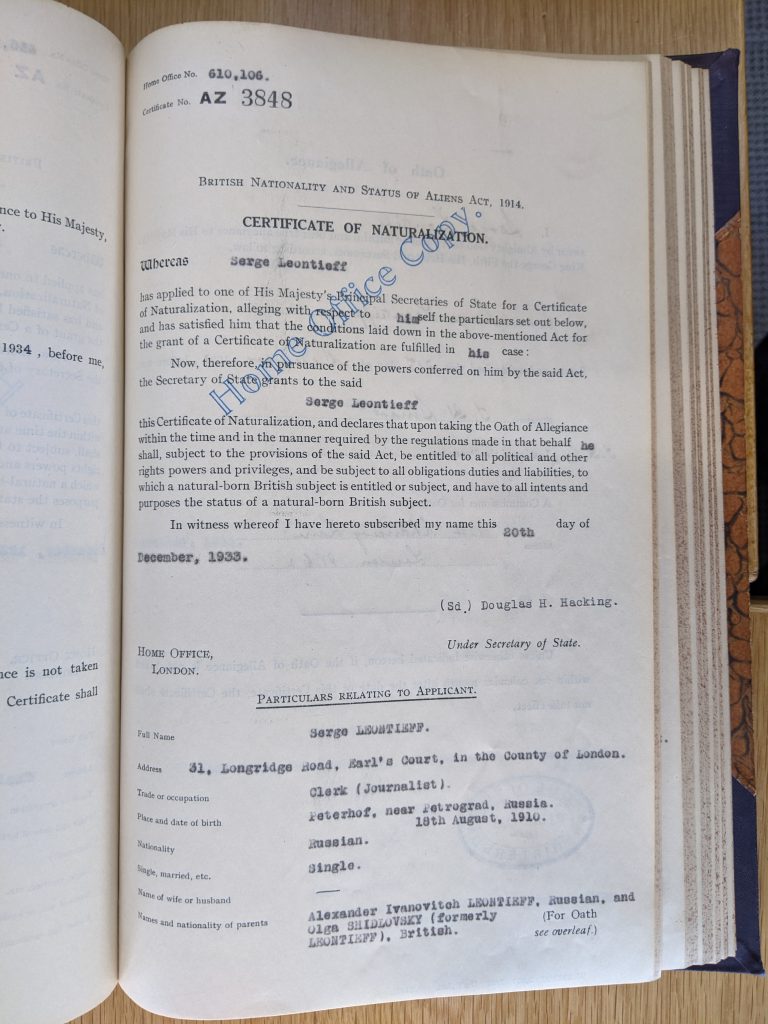

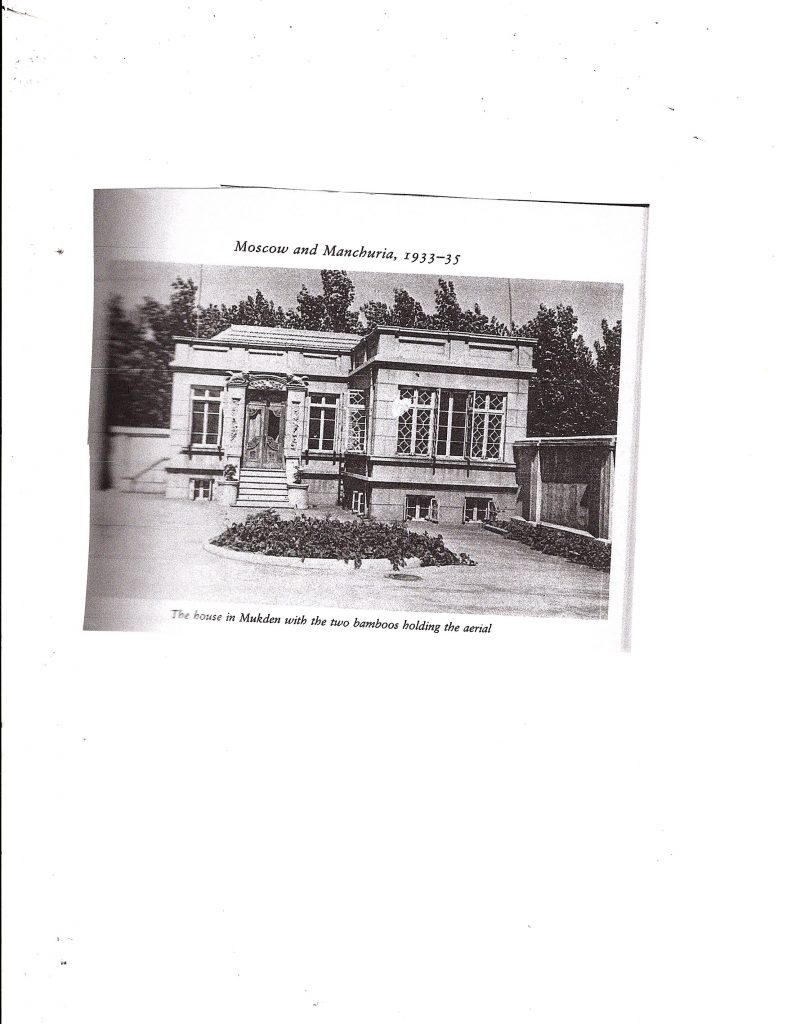

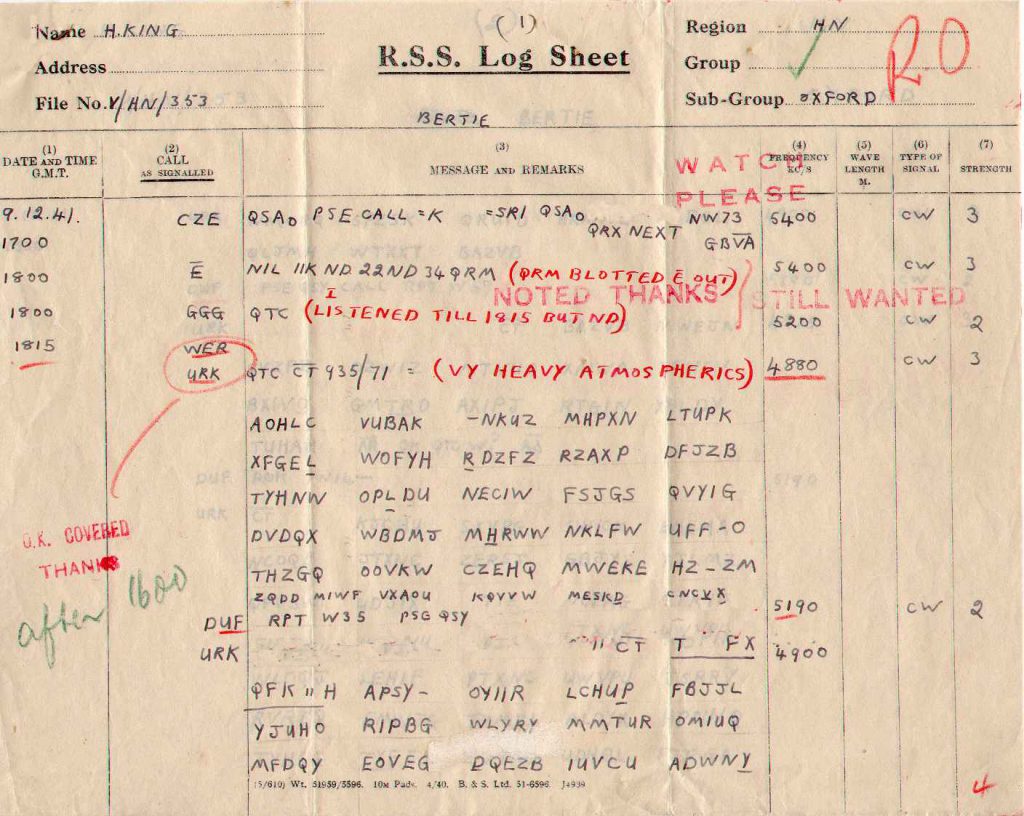

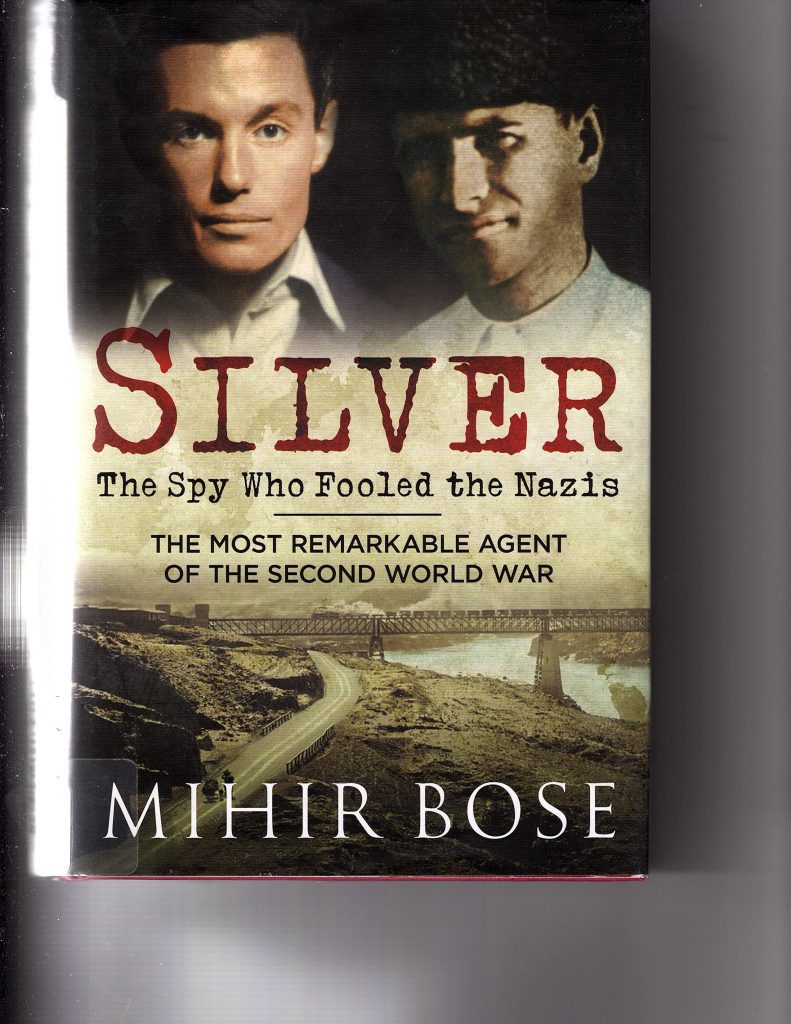

In my piece last month on coldspur, (Who Framed Roger Hollis?), I introduced readers to the strange case of George Graham, né Leontieff, who was mysteriously infiltrated into the SOE mission to Moscow, led by George Hill, at the end of 1941. I can detect a possible link between Dansey and this highly irregular recruitment (although Boyle claimed to be ignorant of Graham’s true identity when he spoke to Liddell in 1945). In his book Silver: The Spy Who Fooled the Nazis, Mihir Bose indicated that George Hill, who had been an SIS officer in World War I, was approached in 1939 by SIS, on Churchill’s request, to help out SIS. Menzies and co. must have been ignorant of the rumour that Hill had sold secrets to the Germans when under financial stress, which led to Menzies’s facilitating Hill’s entry into SOE. (That was the explanation reinforced by Len Manderstam, the head of the SOE Russian section.) Here the story enters even murkier waters that I am not (yet) prepared to plunge into – the tale of ‘Agent Silver’, the cryptonym for the native Indian named Bhagat Ram. Bhagat Ram has been classified by such as Dónal O’Sullivan (in Dealing with the Devil), as a ‘quintuple agent’, a highly imaginative soubriquet, and was eventually controlled (with the term perhaps being loosely applied) by none other than Peter Fleming.

The reason this story is fascinating is that Hill’s counterpart, Ossipov, had suggested to Hill that the two sides should share intelligence information. He revealed to the British that Bhagat Ram was actually spying for the Soviets and gaining intelligence on German plans – an extraordinarily open break from NKVD tradition. The Soviet Union’s need to repel the Germans outweighed its desire to oust the British from India. Moreover, Ossipov was looking for intelligence on the Chinese. When Hill found it difficult to reciprocate, he cabled London in frustration, but it was Menzies who replied to him! As O’Sullivan writes: “On 31 November 1942, ‘C’ [Menzies], while regretting the delay due to ‘our decentralised system’, ordered Hill to transmit the following message to the NKVD: “We have no information on the Siberian Chinese frontier. NKVD will realise that this area is outside our sphere of interest.” The content of the message is not as important as the reality of the communication. Menzies was bypassing the correct channels of command to give instructions directly to Hill as if he were an employee of SIS, not of SOE.

And, indeed, O’Sullivan’s citations from HS 1/191 at the National Archives (which I have not yet inspected myself) show an extended correspondence between Hill and SIS (nominally Menzies, but more probably Dansey). It provides inescapable evidence that the SOE mission in Moscow was in reality an outstation of SIS. It had been staffed by SIS, and was no doubt intended to fill the Secret Intelligence Service’s notable gap in intelligence-gathering in the Soviet Union. Hill went through the motions of liaising with Ossipov on SOE matters, but his superior interests were in intelligence-gathering, and working with Ossipov on Bhagat Ram, a case that he completely overlooks in his memoirs. I do not believe this anomaly has been studied properly anywhere.

This was an unholy mess. The NKVD made no distinction between SOE and SIS, regarding them both as ‘British Intelligence’– rightly so, as we can now understand. Hill was supposed to be representing an organisation dedicated to sabotage, and had no brief to discuss intelligence and counter-intelligence matters, but he did not want to disappoint his counterpart, and he maintained a confidential link with his true bosses in SIS. O’Sullivan conjectures that SIS may have concluded it had a dangerous and unreliable agent (Hill) on its books, but that assessment is surely at fault, as Hill was not officially responsible to SIS. It is more probable that SIS, desperate to gain intelligence from inside the Soviet Union, was trying to insert its own spy under cover of Hill. SIS had probably facilitated the infiltration of the highly suspect George Graham, in the belief that he might be a useful asset, but it turned out that he was blown, and certainly exploited by the NKVD. Thus, without informing SOE, Menzies (or maybe Dansey) tried to take advantage of the Bhagat Ram opening to allow Hill to recruit a more experienced SIS officer to work for him in Moscow. Archie Boyle must have been in a total spin.

Moreover, another thunderbolt struck me as I was completing this piece towards the end of June. I have recently acquired a copy of Nigel West’s book Secret War (The Story of SOE), in a new imprint of 2019. I was not at all surprised that this volume appears to be a facsimile of the 1992 impression, unrevised (and thus very dated in its commentary *), and including all the original errors, since I had quizzed West about the republication of his books a year ago. (See Late Spring Round-up, of May 2020). I have not yet read the book cover-to-cover, but on scanning pages indexed by ‘Claude Dansey’, I discovered, on page 222, the following: “Whilst SIS and SOE must have realized the vast scope for overlap and misunderstandings during the invasion, with competing rival missions operating in the same territory, there was an added complication, namely SIS’s responsibility for running all of SOE’s double-agent operations. While this was a perfectly sensible arrangement, ensuring a single conduit for the dissemination of controlled information to the enemy, there were to be continuing suspicions concerning the sensitivity of the material being conveyed.”

[* Typical of the book’s superannuation is West’s description of the PICKAXE operations conducted by SOE for the NKVD, ‘which numbered nearly two dozen but are still shrouded in mystery’. (p 67)]

This was for me an extraordinary claim – as well as a very dubious judgment by West concerning the ‘sensibility’ of the arrangement. (SIS would clearly have had to be responsible after the Normandy landings, but not before June 1944. The ‘ownership’ of agents who crossed from imperial to non-imperial territory was a constant cause of friction between MI5 and SIS.) I have not yet found the place where West introduces the assertion, and thus have not been able to verify the source. I have peered inside three books by Foot, without reward. I plan to inspect Hinsley and Jeffery to seek a confirmation of this unlikely story. The use of double-agents (or ‘controlled enemy agents’) had to be authorised by the London Controlling Section, and managed by the W Board and the XX Committee, with primary delegation to MI5 (on UK soil). For SIS to have taken the initiative in managing such persons on behalf of SOE is an astounding phenomenon, and would have jeopardized the remainder of such subterfuges.

The security and integrity of the Double Cross Committee, and its control of double agent operations, have always been a point of pride with MI5. Yet, on a second reading of War in the Shadows, I encountered a claim that I had overlooked before. On pages 264 and 265, Marnham (partially) quotes J. P. Masterman’s observation from The Double-Cross System: “In particular the services, whatever their views may have been as to the share in control which belonged to the W. Board or to the Security Service, never questioned or adversely criticised the practical control and the running of agents by M.I.5 or M.I.6.” And Masterman praises the general harmony between MI5 and MI6 that prevailed on the Committee, especially after ‘the M.I.6 representative on the Committee was changed.’

But was the Committee fully informed about all of MI6’s ‘double-agent’ ventures, or that it was managing such operations on behalf of SOE? Masterman tantalisingly explains how ‘the bulk of the agents described were those in the British Isles’, but makes no reference to SOE at all in his book. That suggest that he was either unaware of such activities, or knew about them, but considered them better buried. None of the authorised (i.e. Howard) or unofficial (e.g. Macintyre) histories of deception refers to the role of SOE, Déricourt or Suttill in the STARKEY operation, with all double-agent operations being ascribed exclusively to MI5’s B1A team. (William Mackenzie’s history does describe a role for SOE in STARKEY, but he could not acknowledge any double-cross operations at the time he wrote his work.) Yet one of Marnham’s significant achievements was to extract from Déricourt’s file a hand-written note by. T. A. Robertson that indicated that ‘GILBERT [Déricourt] was well-known to this officer during the war’. Does that claim appear to confirm that the Committee had approved of Dansey’s and Bodington’s intrigues with Déricourt, but thereafter preferred to delete any record from history? The matter screams out for further investigation.

It is difficult to assess exactly what Dansey was trying to achieve with all his vexatious meddling. Did he really believe he had been successful, as Marnham concludes on page 265? To whom was he accountable? Who was giving him instructions? And why did everyone put up with his destructive activity? Were they all scared of him? The only common driver in his policies would appear to be the delusion that he could control hostile agents (Déricourt, Delettraz, Ursula [SONIA] and Len Beurton, maybe Graham) and manipulate them to channel deceptive messages to adversaries – a vast misconception. As with any major failure of British Intelligence (e.g. with Klaus Fuchs), one has to judge to what degree the fault was one of Incompetence, Negligence, or Treachery. In Dansey’s case, it would appear to involve all three.

Postscript

I showed an earlier draft of this piece to Mr. Marnham, and he very graciously gave it some close attention. I have incorporated corrections to some errors, and revised some passages where I had overlooked parts of his argument, but I decided that the multiple elaborations and explorations around key items should be treated separately. One reason is that I want to complete my study of Nigel West’s book, read Francis Suttill’s account of his father’s demise as well as Robert Marshall’s All The King’s Men, and inspect the relevant files at the National Archives to bring me up to speed. I also want to re-examine Christopher Murphy’s Security and Special Operations, which has a weighty chapter on Déricourt that had been of only secondary interest when I read the book several months ago. I thus re-present Marnham’s other comments here (with minimal editing), without any response from me. It is appropriate that he have the ‘last word’ for a while.

On the last bizarre sentence of Suttill’s letter to the TLS:

In the last paragraph of his letter FJ Suttill inadvertently supports my argument. He has abandoned the position stated in his book and now agrees with me that during that Paris trip Bodington betrayed his own radio operator, Jack Agazarian. But Bodington did not sacrifice Agazarian to save his own skin. He sent his radio operator into a trap to protect Déricourt, who, if he was to continue working as a deception agent, needed to provide regular information for the Gestapo. Agazarian was eventually executed in Flossenburg, while Bodington returned to London and Déricourt stayed in France, where he could continue to inform and misinform German intelligence in the run up to D-Day.

On Perrin’s repeated misquotation in his letter to the TLS:

Two examples: the ‘single memo’ I have uncovered linking Déricourt – an F section field agent – and the vice-chief of SIS, Claude Dansey, does not just ‘mention their names’ as Perrin claims. That is nonsense. The memo actually shows that Dansey was directly intervening in MI5’s long-running campaign to have Déricourt recalled. Nor was my discovery ‘a single memo’. It formed part of a six-month series which I have reconstructed, and which reveals that a second (unidentified) officer from SIS, in this case from Section V (counter-intelligence), was also intervening in the MI5 campaign.

Perrin again massages the evidence when he refers to another document in the National Archive records that I publish for the first time. This note – from T.A.Robertson, the former head of the XX (deception) Committee – does not ‘merely show’ (in Perrin’s words) that Robertson ‘knew about MI5’s investigation into Déricourt’. In an initialled scribble Robertson warns a fellow MI5 officer that he has information about Déricourt ‘that will greatly supplement what appears in our files’. Had Mr Perrin quoted the note correctly it would have saved him from making his next mistake – demanding to know why there is no mention in the XX Committee records of Déricourt giving information to the Paris Gestapo.

On Boyes’s assessment that Marnham had left the whole question of betrayal open:

Actually Boyes was wrong about this. I stated clearly that Prosper was betrayed as part of a deception operation. I distinguished this from the arrest of Jean Moulin, stating that I had failed to prove Dansey’s responsibility for this, but had established that he had the means and the motive to carry it out.

On my interpretation that Déricourt engineered the betrayal of the PROSPER network:

My argument is, to put it more precisely, that Déricourt did not so much ‘engineer’ their actual arrest as provide the SD with the necessary information to catch them, and then demoralize Prosper & Co. with Boemelburg and Kieffer’s knowledge of the secret messages Déricourt had passed on. See my pp .249-50

On my statement that the Double Cross Committee was aware of the deception:

They may well have had general knowledge of the first deception i.e. involving Prosper. They would not have been at all well informed about Dansey’s activities through Geneva.

On the attention I drew to the fact that Marnham’s historical references were somewhat dated:

My reference to this, a much stronger one, should have been ‘Michael Howard, British Intelligence in World War II: Vol. V (1990), p.103.’ Of course all generals want bigger armies, but there is pretty strong evidence that von Rundstedt was properly alarmed by Starkey.

On my observation that Marnham stated that the Sicily landings took some pressure off the deception staff:

What I was hoping (but clearly failing) to convey was that another credible advantage of Starkey/Prosper/Moulin –was that when the Sicily landings took place, the OKW would have concluded that the alarm about the build-up of weapons in France had been a distraction from preparations for Sicily. At the same time, the Gestapo’s success in recovering a huge Resistance arsenal and in seizing so many important commanders would have safeguarded and increased Hitler’s confidence in the Paris Gestapo’s competence. I agree, more thought needed.

On my questioning of the symmetry of the Prosper/Moulin deceptions:

I take your point and I explain this differentiation as follows: I do not think that there was a plan to betray Moulin as part of a deception operation in March 1943. I believe he was misled before his departure, as a precaution. So, if he was arrested, the precious (mis)information he held could – when ‘extracted’ from him – have become part of the deception. But by May 1943, when Suttill was misled, ‘Starkey’, and the need to alarm the OKW, had developed to a point where the penetration of Prosper could be disclosed to senior SOE officers (but not to F section). SOE’s leaders (Gubbins, Boyle and Sporborg) could then be informed that a decision had been taken ‘to exploit the situation’, see my p.264].

On my highlighting the political reasons for eliminating Moulin:

See my preceding note: to which I would add – Dansey was a loose cannon, accountable to ‘C’ (Menzies) for his ‘kosher’ activities in France via Commander Cohen and ‘Biffy’ Dunderdale, but accountable to no one when it came to operations via Geneva, where he was essentially running a pre-war, Z-style, parallel intelligence service. My other point is that by the time of his arrest, Moulin had so many enemies that more than one of them could have been involved in his betrayal. His enemies included – a. leaders of Combat in France, b. BCRA Gaullists in London, c. PCF (Communist) resistance leaders in France – but also the Chiefs of Staff in London, as well as Philby/Blunt in London who were priming the PCF via Moscow, see my p.297. I deal with a., b. and c. at length in my Jean Moulin book, and briefly in this book on pp.297-8. The new possibilities I have investigated in this book include the clear line involving Dansey and Victor Farrell, which your own research has greatly strengthened. There is also the use by SIS (i.e., Dansey) of Colonel Groussard, a really sinister figure, and a really strong link to the betrayal of Moulin. In addition there is the potential involvement of both Philby and Blunt in deception planning (Blunt) and execution (Philby).

On my suggestion that Déricourt was more a traitor than a double-agent:

Thank you for the correction about ‘double agents’, and it may be that you are right and Déricourt was just a traitor. But if he was ‘just’ a traitor it is rather odd that he was welcomed back to London in January 1944, and subsequently paid a very large sum of money from British public funds. I think his correct ‘status’ depends on how soon he was identified after his arrival in September 1942. My line is that he was picked up almost at once by an SIS spotter. For me this is the only explanation for the way in which MI5 were kept in the dark, from the start, and throughout 1943. The Security officers passed on warnings about Déricourt time and again and were consistently brushed aside. These warnings would normally have gone to Boyle’s security department, or would otherwise have been picked up by F’s deputy head, Bodington. So, Déricourt was clearly being protected by another agency, and it was not SOE, and obviously not F section. There are it seems to me two possibilities: either he was ‘turned’, as I have written – rather sloppily, as you point out – or a British Intelligence master of deception realized that he could be used without being recruited or ‘turned’. In other words, we could both be right. Déricourt could have been sent back as a bona fide SOE officer to win the SD’s confidence by providing accurate information about F section activities, and in due course be fed false information about far more important matters (e.g. the date and locality of the D-Day landings) which he would also pass on. That fits the Déricourt story, and Bodington’s consistent protection of him into the spring of 1944, reasonably well. But to devise that scenario you would need a senior SIS officer involved in deception, who had a total contempt for SOE, and was prepared to misuse its agents in the overriding national interest, as he calculated it. This officer would also need a large measure of autonomy. And in trying to identify him it would help if he also had a record of ordering the ‘elimination’ of untrustworthy agents – all of which Dansey had. Anyway, that is what I was working towards when I wrote ‘Déricourt was ‘of course a classic candidate for a deception operation, a Gestapo agent unmasked on arrival in England’. Incidentally, the XX Committee would not have had to ‘sanction’ the destruction of Prosper. As an MI5 outfit they were only responsible for double agents operating on British territory. Operations on foreign territory were strictly SIS. That note TA Robertson of MI5 wrote in 1946 (my page 284) could have referred to information he had acquired after the War, when evidence of Dansey’s misuse of F section emerged and was being energetically destroyed by SIS. Looking at this scenario from Déricourt’s point of view I am reminded of Trevor Roper’s observation that (I quote from memory) ‘the beauty of being a double agent is that you can defect either way’. The beauty of this plan from Dansey’s point of view is that it did not matter which side Déricourt eventually decided he was working for. The cosier he and Boemelburg felt about each other, the more effective Déricourt would have been as a tool of deception.

On my comments on the recruitment to SOE of Bodington and Déricourt:

I have since discovered new evidence about Bodington’s arrival in SOE, and a new rather sinister patron for him. It was not Boyle who recruited Bodington, it was probably Leslie Humphreys. And Bodington did not join SOE as his personal file shows (my p.61) on 18 December 1940. This was the date Humphreys (then head of F) switched Bodington into F from SOE’s planning department, where the ex-journalist had been working since at least 7 October 1940. (Source: David Garnett The Secret History of PWE (2002) p.52.) This correction will be in the paperback.

On my reporting of SIS using SOE’s George Hill as an SIS asset:

This is extraordinary. You have uncovered clear additional evidence that SIS was using SOE as a reservoir of conveniently ‘deniable’ (keyword) possibilities. And it was not just Dansey, it was ‘C’ as well.

* * * * * * * * * *

This exchange is, in my mind, an example of exactly how research should advance. I thank Mr. Marnham for engaging in discussions with me, and we plan to continue our investigations into the machinations of the mischievous Claude Dansey. Sadly, attempts are being made to silence Marnham. He spoke at the Chalke Valley History Festival last weekend, and one ill-mannered detractor, his chief antagonist, advertised on a hobbyist website that he would be attending to ‘attack’ Marnham. He was further encouraged by one of his sidekicks to ‘give him hell’. Moreover, this individual was supported in his plans by others who had not even read the book, but were confident in their scorn. Apart from the gaucheness of the announcement (rather like Eisenhower informing the Germans that the landings would take place in Normandy, in early June), such an approach is intemperate and unscholarly. Moreover, I detect a tactic of rubbishing ‘conspiracy theories’ on the grounds that such phenomena must be inherently and irredeemably flawed. Yet, if there is evidence of treachery, and that the authorities knew about it, but condoned it, or of plotting to endanger a colleague (something that Suttill explicitly admits), any intelligent observer has to try to develop a theory as to why such a conspiracy took place. I am very happy to provide space to counter such gross behaviour, and try to shed more light on the affair.

(New Commonplace entries can be seen here.)