Contents:

Introduction

Topical News

Litzi Philby

The Martin Interview

Candidates for the Mystery Interviewee

Helen Fry & ‘Spymaster’

A Fragile Marriage

Kim’s First Spell in Spain

Kim’s Second Spell in Spain

Litzi in France

The Approach of War

The Honigmann Era

Life in the East

Conclusions

Postscript: Charlotte Philby & ‘Edith and Kim’

* * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

From comments offered by readers of coldspur, I understand that substantial interest endures in the affairs (both political and amorous) of Kim Philby and his first wife, Litzi. In recent months several useful contributions have been posted, and I now take up the challenge of trying to make sense of the fragmented archival material and memoirs that exist. To me, the burning questions outstanding could be framed as follows:

- Why was Litzi deployed by Soviet intelligence when there was a severe risk of exposing Philby in so doing?

- Why were Philby’s connections with Litzi and her communist associates not picked up and taken seriously by British intelligence?

and, as a specific inquiry into a very bizarre period:

- What was Philby up to in Europe in 1945?

I originally intended to address all three questions in this month’s report, but I had so much material on the first to consider that I shall defer addressing the latter two until next month.

But first, I want to comment on some recent relevant events.

Topical News

A few weeks ago, one of my most loyal readers, David Coppin, alerted me to an on-line article from the Daily Mail that described Andrew Lownie’s efforts to have a ‘Seventh Man’ identified (see https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3797379/The-seventh-man-Letter-reveals-new-1950s-Cambridge-spy-suspect-judge-rules-t-named-alive.html). I have to admit that my first impression was that this was a recent revelation, until I saw that the item was dated September 19, 2016. Nevertheless, since I had not seen the piece before, it set my mind racing, and I wondered about the unreality of it all. It referred to a letter in which the ‘seventh man’ had been identified, and that he was moreover part of the 1950s Cambridge spy ring. Yet the person could not be named because, as the judge Sir Peter Lane explained in his ruling, he was still alive and it was ‘quite possible that personal relationships could be jeopardised’. Tut! Tut!

Now, by the 1950s, this Cambridge ‘spy ring’ was in disarray. Burgess and Maclean had debunked to Moscow in 1951, Philby was under suspicion, Blunt was dormant, and the outlier Cairncross had had to retire from the Civil Service in 1952 because his ‘indiscretions’ had been detected. Wilfred Mann lived in the USA. To be genuinely part of that ‘ring’, any spy would have had to be one of the ideological true believers of the 1930s, and would thus have been born in the years between 1905 and 1915. For any such person to have survived until 2016, he would be a centenarian of some repute, and I thus cannot understand how the judge could confidently maintain that such a person (not George Blake, who was never a member of the Cambridge ring anyway) was both a close associate of the Cambridge Five and also among the living in 2016. (Even Eric Hobsbawm had died in 2012.) Had an MI5 officer perhaps rather playfully referred to a ‘seventh man’ even though he might have been a less harmful fellow-traveller, or even a less important younger agent who had been convinced of the righteousness of Communism? Remember, after the brutalities of Stalinism in Eastern Europe after the war, there were few fresh champions of Soviet-style Communism in the West. Most spies from this time had mercenary motives, or were blackmailed into the game.

The article did not mention the Oxford Group (Wynn, Floud, Hart & co.), but they too were, as far as we know, all dead anyway. How many ‘men’ there were in this cabal is a source of endless fascination – even whimsy. I can imagine a cricket-team of Stalin’s Men, all A-listers, with a twelfth man waiting in the pavilion should any one of the select XI become disabled. I see them taking the field, with Rees and Maclean to open the bowling. Mann is behind the stumps, Philby and Blunt can be seen discussing who should be at Third Man, Burgess perches uncomfortably at Square Leg, Leo Long has a despondent air at Long Off, Cairncross and MacGibbon are crouching nervously in the slips, Michael Straight has been correctly placed at Silly Gully, and, my goodness, could that be Lord Rothschild patrolling the covers as captain . . .? Despite such bathetic ruminations, I still wondered where this Freedom of Information inquiry stood. Seven years later – surely Sir Peter Lane, who is apparently still busy on his various benches, must have volunteered some fresh insights by now. Was his mystery man still alive?

I decided to contact Andrew Lownie, whom I knew from several years ago, and had met in London. I had also tracked his tribulations with the Mountbatten papers in Private Eye. He responded very promptly, but was singularly unhelpful and unimaginative. His first message stated that ‘the case was still rumbling on’ (shades of Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce), and he asked me whether I had any ideas who the person might be. Not having seen the evidence, I declared I had no idea, and explained my reasoning given above. I asked him for further details on what he had found, and he merely wrote back ‘All I know is the original file number which is in the tribunal decision’. And there the matter lies: all very unsatisfactory.

Next, an obituary in the New York Times on February 19 caught my eye. It was of Arne Treholt, a Norwegian diplomat convicted in the mid-1980s of spying for the Soviets. Here was a trusted high-flyer, discovered with sixty-five confidential documents in his briefcase as he tried to leave Oslo airport to meet his KGB handler, Colonel Gennady Titov, in Vienna. Tipped off by Soviet defectors, the Norwegian authorities had already found piles of cash in his apartment. After his plea of idealism, ‘wanting to lower tensions between nuclear-armed antagonists’, failed to influence the court, he resorted to claims that he had been subject to blackmail after compromising photographs had been taken of him at a party in Moscow in 1975. Treholt was sentenced to twenty years in prison – the maximum allowed – but then was inexplicably released and pardoned in 1992.

But worse was to come, as the Times reported: “After his release, Mr. Treholt received the equivalent of about $100,000 from an anonymous donor, money he used to start a new life in Russia. Along with his investment activities, he became an advocate for Russian interests: most recently, he wrote articles defending the Russian invasion of Ukraine.” Thus the idealistic peacemaker, abetting the brutal communist regime, effectively switched sides, supporting the neo-Fascist Putin, whose policy of trying to come to the help of ‘ethnic’ Russians living in places like Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and Latvia most closely resembles that of Hitler, trying to bring ‘ethnic’ Germans scattered from the homeland into a greater Reich.

To call Treholt a ‘worm’ would be an insult to the entire worldwide vermiform community. It reminds me of Kim Philby, professing how he could not turn down an offer to join an elite force. So long as that membership gave him attention, and made him feel that he was doing something worthwhile in the vanguard of humanity, it probably did not matter which totalitarian secret police force it was, either the Gestapo or the KGB. But at least Philby didn’t accept piles of cash.

To show how allegiances have been turned upside down in the twenty-first century, I next cite the case of Carsten Linke, a former German soldier, who was recently arrested in Bavaria on charges of treason and spying for Russia. No clear financial incentives had been detected, but Linke was known to have been linked to the far-right party, AfD (the Alternative fűr Deutschland). As the New York Times reported: “Over the years, far-right groups have grown increasingly sympathetic to Russia, enamored of Mr. Putin’s nationalistic rhetoric.” The German Federal Intelligence Service (the BND), notoriously leaky from Cold War days, had recently appointed Mr. Linke to head personnel security checks, and he probably passed on masses of information about possible informants to his Russian controllers. The same KGB officer in Leningrad who plotted to help overthrow the imperialistic and fascist West, Vladimir Putin, has now become the role model for the worst tendencies of a movement whose mission had originally been to demonize the Communist regime that Putin defended and served so loyally. And yet Putin characterizes those who assist Ukraine as ‘fascists’.

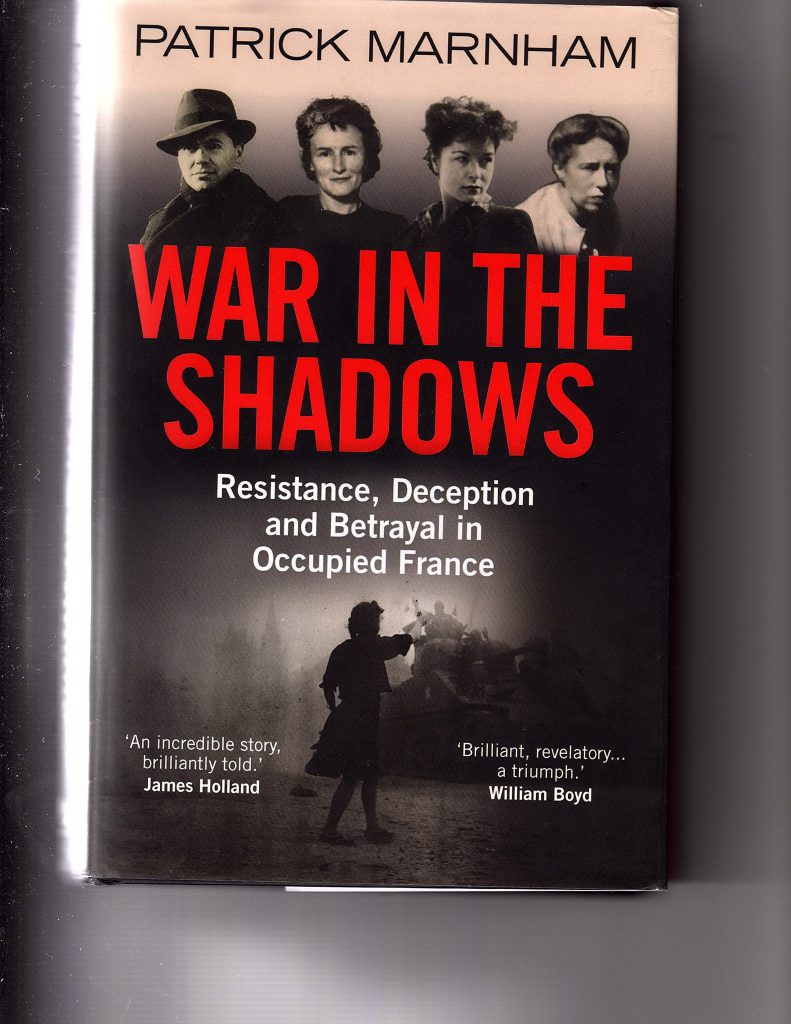

Lastly, a mention of Nigel West’s latest book, Spies Who Changed History. It is more out of a sense of duty than excitement that I have acquired West’s recent publications, but I diligently ordered this new item, despite the trite and overused formula of its title. (Of course no one ‘changes’ history, as history is invariable.) It is subtitled The Greatest Spies and Agents of the 20th Century, not to be confused with West’s 1991 offering Seven Spies Who Changed the World, which somewhat diminishes the focus, if ‘agents’ (recruiters, couriers, agents of influence and the like) were to be included. So which central figures were to be given this fresh analysis?

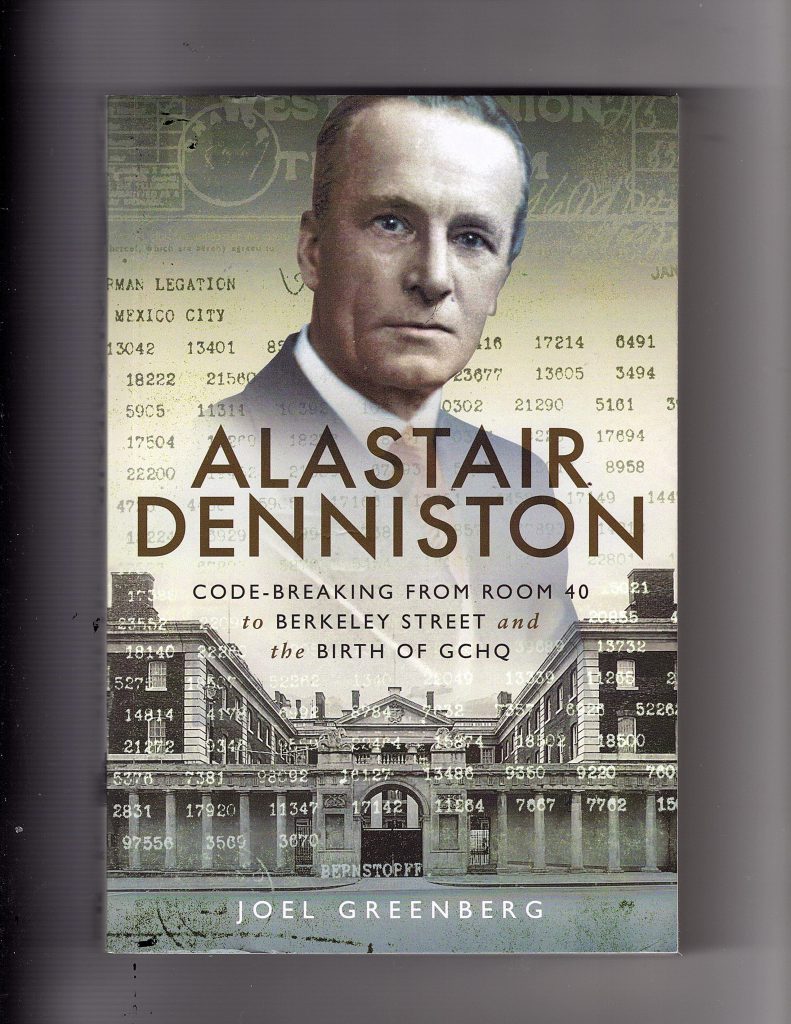

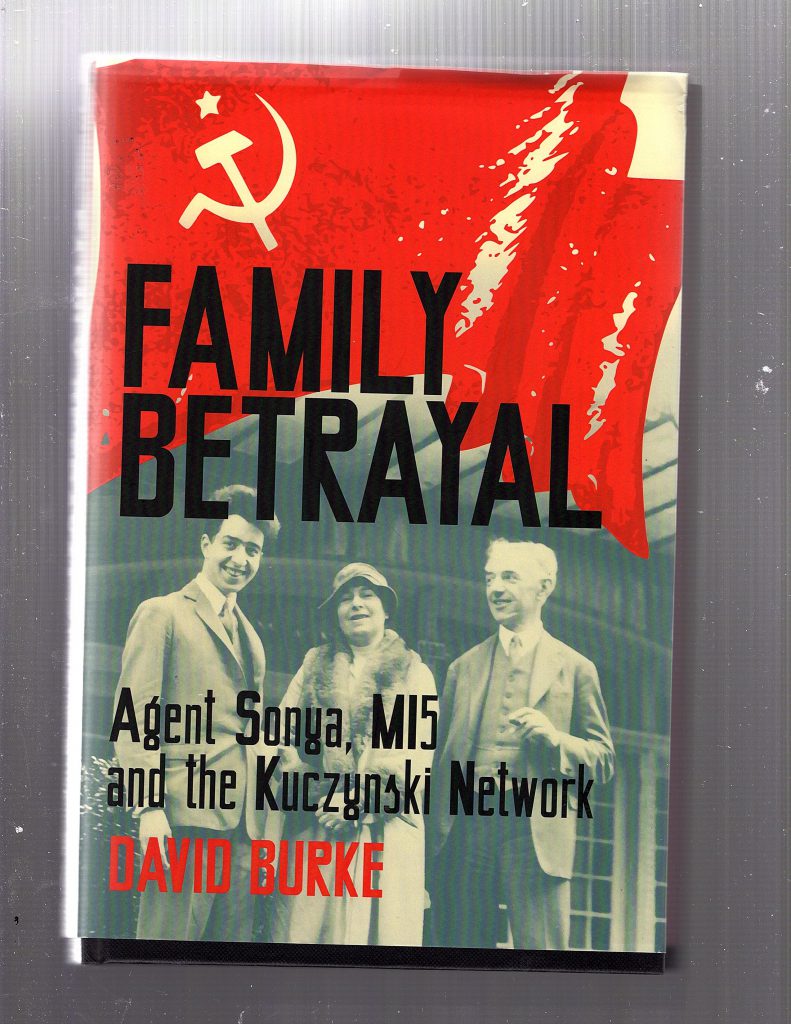

My heart skipped a beat when I noticed a photograph of Edith Tudor-Hart (née Suschitzky) on the cover, since I was naive enough to believe that I might learn a lot more about this intriguing character who played a perhaps overstated role in England as recruiter, courier, and photographer in the Comintern’s conspiracies of the 1930s and beyond. Yet she is not in the list of West’s fourteen history-changing agents, a roll-call that ranges from Walter Dewé to Gennadi Vasilenko (yes, of course you recognize those names!). The only reason that she appears on the cover is that she was one of the prime recruits of Number 4 in West’s catalogue, Arnold Deutsch, who was never a spy in his life, but a Soviet illegal. (That portraiture on the cover must constitute some kind of misrepresentation.) To distract his readers even more, in his Acknowledgements West offers his gratitude to over a hundred persons who assisted his research, nearly all of whom are dead, and whose number include Anthony Blunt, John Cairncross, Len Beurton, and Ursula, Robert and Wolf Kuczynsky [sic]. I hope they all advised him with honesty and integrity. This is a very sorry work, replete with pages and pages of transcribed archival material, that should never have been published. A few decades ago, Nigel West developed a brand that indicated high competence in research: for example, this month I read his excellent 1989 book, Games of Intelligence, which gives a fascinating overview of the intelligence and counter-intelligence institutions of the UK, the USA, the Soviet Union, France and Israel, and their successes and failures. What a falling-off there has been.

But to return to my main topic . . .

Litzi Philby

Matters were relatively simpler back in the 1930s. Diehard communists for the most part remained loyal to their totalitarian boss, even though they had a devilish time concealing their ideological roots when they went under the cover of the British intelligence services and other institutions. Litzi Philby (née Kohlmann, then Friedmann, then Philby, then Honigmann, with several lovers throughout this period) was an extraordinary exception, since, as an open Communist Austrian-born Jew, she never hoped or planned to be able to work for the British establishment, but neither did she make much effort to conceal her loyalties. She remained an agent of the NKVD, acted as a vital courier, was lavishly supported by the NKVD for a while, and even sent back from Paris to England in 1940 as the Nazis approached. In approving and effecting her return to her husband’s haunts, however, it would seem that her bosses undertook an enormous risk that Kim Philby might thereby be exposed. Why did they do it? I explore that conundrum in this text.

For those readers who may not be closely aware of the role that Litzi played in Philby’s treacherous career, I refer to her Wikipedia entry at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Litzi_Friedmann. This is overall a serviceable though flawed summary, and shows the difficulties of trying to verify details of her life and background from somewhat dubious sources, including the mendacious account of her own life that she bequeathed to her daughter. It also omits some critical events in her career. Moreover, why she should be known as Litzi Friedmann, I have no idea. Her maiden name was Kohlmann, her marriage to Friedmann lasted only about a year, and she was Mrs Philby from 1934 to 1946, which represents the essence of her puzzling career trying to stay under cover.

Tracing the recruitment of Soviet agents with confidence is a notoriously difficult business. In Misdefending the Realm (pp 37-39) I detailed seventeen different accounts of how, when and where Kim Philby had been recruited, and I cited the author Peter Shipley, who wrote: “No fewer than twelve individuals have been identified as the recruiters, and, or, controllers of Kim Philby between 1933 and 1939”. Moreover, the event of ‘recruitment’ is necessarily fuzzy. Potential serious candidates for infiltration may have worked first as couriers or spotters; they may have been given a cryptonym before being ‘officially’ recruited – a process that required approval from Moscow. They may have been members of the local Communist Party, or one of its cover organizations. A superficial distinction was made between working for the Comintern and the more serious Russian Intelligence Services (the NKVD or the GRU). Memoirists may have had ulterior motives in misrepresenting what happened: drawing attention to their own successes as a recruiting-officer, for example, or concealing the importance of another agent by misrepresenting the role of a minor figure. Kim and Litzi plotted how they should separately explain their story should they be blown: Litzi openly lied to her daughter about the course of events, but claimed that she had forgotten many of the details – maybe a protection mechanism against decisions and activities she later regretted.

The outline of the story seems uncontested. In 1933, Philby, on the guidance probably of his Cambridge tutor Maurice Dobb, sought out the IOAR (International Organization for Aid to Revolutionaries) in Vienna, a communist front. He discovered that Litzi headed the group in the ninth district, lodged with her and his parents, and was seduced by her in between more formal activities of helping communists oppressed and chased by Dollfuss’s government. Philby became the treasurer of the branch, raising and distributing money. His British passport enabled him to travel as a courier to Prague and Budapest. With Litzi under threat, they married on February 24, 1934 to give her authority for making her escape to the United Kingdom, with her new spouse in tow. They arrived, via Paris, in early April.

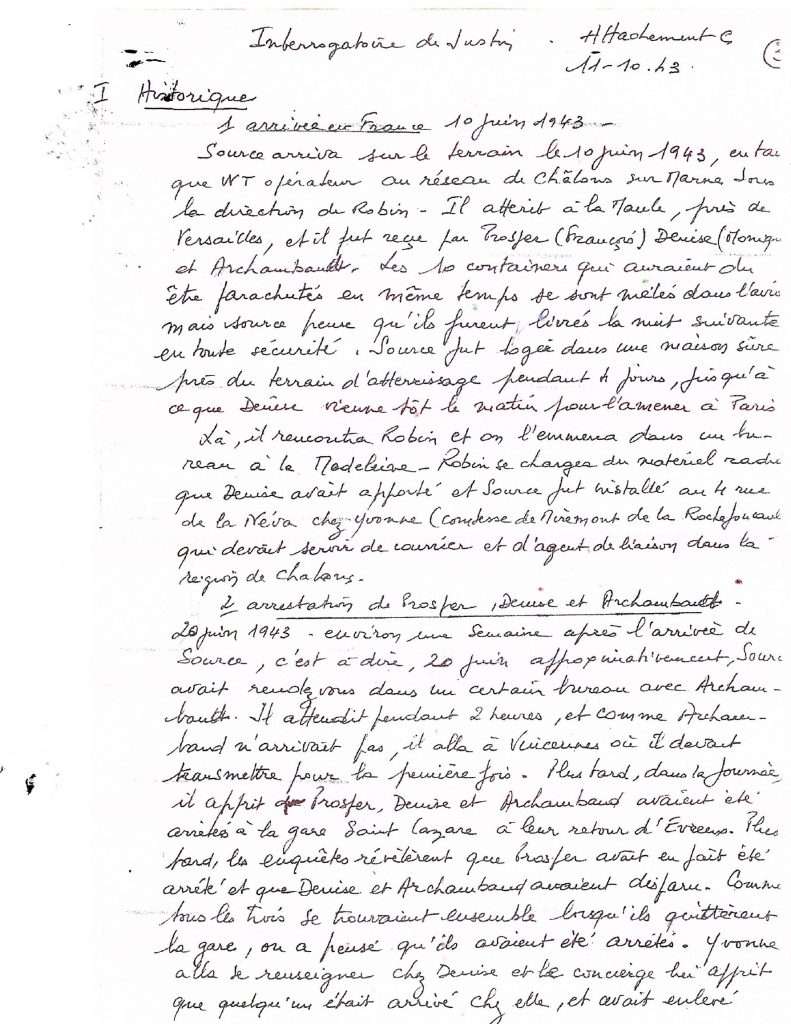

The Martin Interview

In October 1951, in the wake of the abscondment of Burgess and Maclean, Arthur Martin of B.2.B in MI5 was busily investigating the possible involvement of Philby. He had invited a known acquaintance of Edith Tudor-Hart to an interview on MI5 premises, and he was accompanied by an unidentified ‘Captain’. (Tudor-Hart was a forerunner of Litzi’s. She had been a Communist in Vienna and had married a British doctor, thus enabling her to reside in Britain, where she led a nefarious cell – the Austrian Communist Party in exile.) Martin explained that the enquiry was ‘more than usually confidential’, and thus he requested utmost secrecy from his interviewee. He further explained that the subject of the enquiry was Lizzy [sic] Philby, and that he wanted his subject to recount all that he knew about her. [The record of the conversation is held in one of the Tudor-Hart files, KV 2/1014, at the National Archives. Unsurprisingly, Litzi Philby’s file has not been released.]

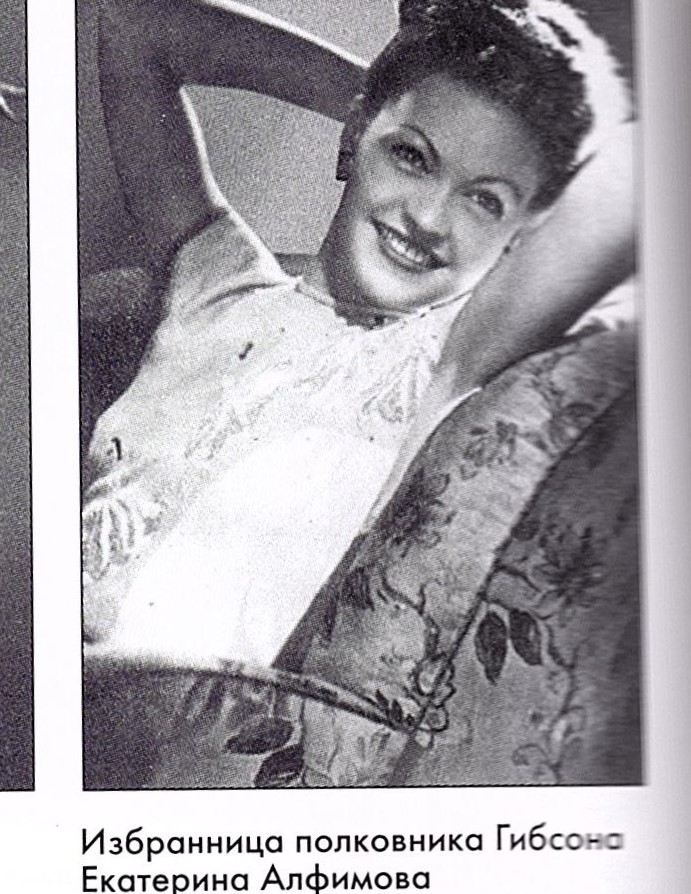

The interviewee, whose name has been redacted from the report, started by saying that he had met Litzy ‘spasmodically’ between 1944 and 1946 in London, and thus had personal exposure to her, but that most of the knowledge of her background came from Edith Tudor-Hart. Martin recorded his assessment of her character as follows:

. . . a woman who, though an out and out Communist, enjoys good living and is certainly not the self-sacrificing type. She is attractive to men. Xxxxx said that he had always been curious about Lizzy because she was so obviously above the level of card-carrying Communists and never seemed to want for money. He compared her standing in the Party with that of Arpad Haasze, a Communist he had known in Vienna in the early 1930’s. Haasze, said Xxxxx, had definitely worked for Soviet Intelligence.

Now, is this not a startling testimony? The interviewee appears to know a lot about Litzi’s life-style, and admits that he had ‘always’ been curious about her. That is a strange choice of qualifier for an acquaintance that has outwardly been only occasional, and restricted to a couple of economically austere years at the end of the war. Furthermore, the overt reference to movement in Communist circles in Vienna in the early 1930s provides a solid clue as to the person’s identity, while also casting doubts on the honesty of his narrative. How did he learn about Litzi’s ‘standing within the Party’ from meetings in war-time London? I shall return to this matter, but Martin had further questions about Lizzy’s pre-war activities, and wrote up Xxxxx’s responses as follows:

Xxxxx had heard that Lizzy was first married (he presumed in Vienna) to a wealthy Austrian whose name he could not remember. He did however make a guess which was sufficiently close to convince me that he meant FRIEDMAN. Xxxxx did not know when or whence Lizzy came to the U.K., nor did he (until a few weeks ago) know anything more about her second husband than his name was PHILBY. He still has no idea when or where they were married or when they were divorced. His one firm conviction was that Lizzy had lived in a flat in Paris before the war on a fairly lavish scale. When asked how he knew she lived well while in Paris, Xxxxx said that he remembered Lizzy had a bill for £150 for storage of her furniture in Paris throughout the war, from which he had deduced that her possessions there must have been fairly substantial.

How kind of Litzi to confide to such a nodding acquaintance the secrets of her personal finances! Martin, however, did not follow up on this provocative assertion. He moved quickly on to their subject’s association with H. A. R. Philby, to which Xxxxx responded (apparently forgetting what he had stated a few minutes earlier): “Xxxxx said that (until a few weeks ago) he knew nothing of PHILBY except that he and Lizzy were divorced by 1944.” Martin notes that this latter fact was not true, but does not record that Xxxxx had been found out in an obvious lie, he having previously denied knowing when they had been divorced. Unfortunately, the bottom of this page of the record is torn and undecipherable, although it does indicate Martin’s apparent interest in how Xxxxx had learned of the event.

Moreover, the character whom the interviewee compared with Litzi, Arpad Haasze (or Haaz), was known by MI5 to have been Edith Tudor-Hart’s partner (both professional and amorous) in Vienna at this time. The tracking of Haasze went back many years: a note from May 3, 1935 records that Edith had cabled £25 to Arpad Haas [sic] in Zurich. Haas also had had a Personal File (68890) created for him at this time, although the author said that Haas ‘is probably quite O.K.’ MI5 would in time learn otherwise. A note in Edith’s file, dated February 24, 1947, records that she had worked for Russian Intelligence (she confessed this fact to MI5), ‘and ran a photographic studio in Vienna as a cover for her Intelligence work, together with a Russian who was also her boy friend.’ And a further note, dated August 16, 1947, includes the following:

Mrs TUDOR-HART’s partner in the Russian Intelligence set-up in Vienna before the war, who after the discovery of the ‘activities’ by the Austrian authorities, fled from Austria and was later reported dead by the Russians, has suddenly appeared in the Russian Zone of Austria. Mrs Tudor-Hart recently received a letter from him in which he stated that he is now working with the Russians. He does not give any details of his work. He is an Hungarian named Arpad HAAZ and gives his address as: c/o U.S.S.I.W.A , 25 Glauzing Gasse, Vienna XVIII.

Through these hints of familiarity, the interviewee shows himself be a close friend of Edith Tudor-Hart (whom he describes in the record as ‘a sick woman, highly neurotic, and suffering from persecution mania’). He indicates that he has been having regular conversations with her.

I shall return to the remainder of the interview later, when I analyze Lizzy’s relationship with Georg Honigmann, but I need to speculate here on the identity of the interviewee. Here is what we know about him (apart from the fact that he is a clumsy deceiver):

- He is an apparently well-trusted source, a man of some standing

- He is someone who was intimately involved with communist movements in Vienna in the early 1930s, to the extent of being acquainted with assuredly genuine Soviet agents, such as Haasze

- He knows Litzi from occasional encounters between 1944 and 1946, yet is aware of her standing in the Communist Party

- He knows Litzi had been married again, to someone called Philby

- He did not know who ‘Philby’ was until a short time before the interview

- He knew that the Philbys had been divorced in 1944

- He is much more familiar with Edith Tudor-Hart

Yet what is also remarkable is the reaction of Martin and his partner, and their subsequent interaction. They appear to be utterly unsurprised by Xxxxx’s admission that he was familiar with the communist underground in Vienna in 1933, and, likewise, Xxxxx does not attempt to conceal such activity. They are, moreover, completely incurious about the man’s activities in Vienna, having presumably failed to do any homework, and miss the obvious opportunity to ask how he had not been aware of the collaboration and affair between Kim and Litzi. They never ask why he has associated with both Litzi and Edith Tudor-Hart, both of whom were known to MI5 as dedicated communists, probably involved with espionage. Why would Edith have told this person so much about Litzi Philby? While listening solemnly to the account of how the interviewee knew many details of Litzi’s extravagances in Paris, they never ask why the facts about her marriage to Philby were not revealed to him. Why did the name ‘Philby’ mean nothing to him until the autumn of 1951, when Litzi would have borne the name ‘Philby’ when he met her in the mid-forties, and presumably provoked his interest? It is all utterly unreal – and unprofessional – as if the whole exercise were a charade.

Candidates for the Mystery Interviewee

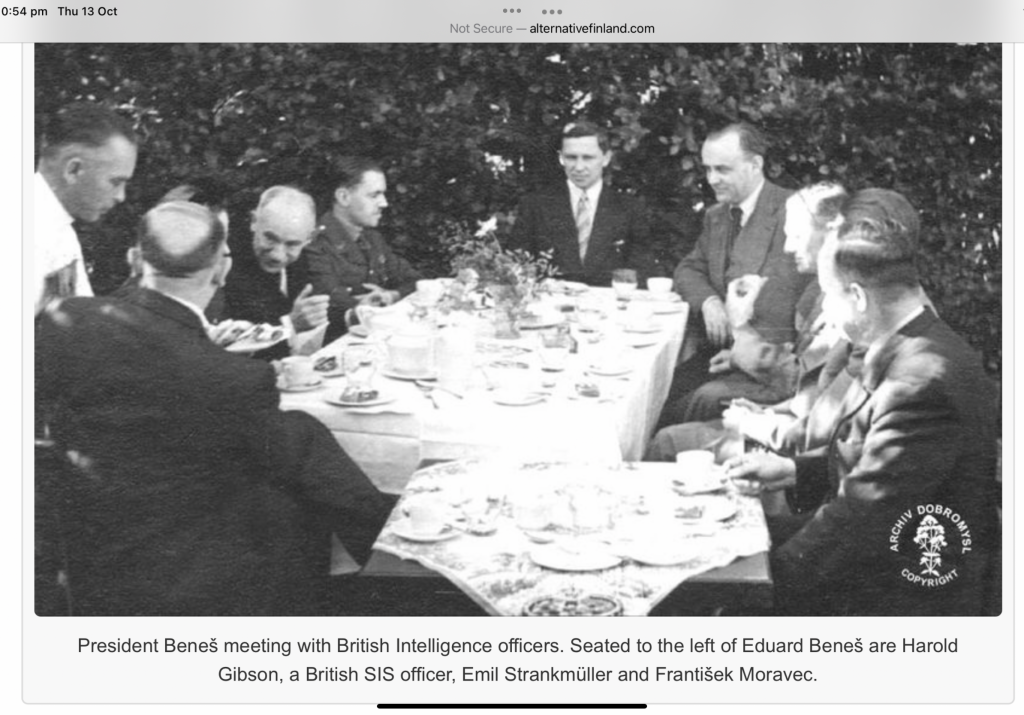

It is time to speculate on who the mystery man was. The redacted space where the name would have appeared is about five letters long. Two candidates come to mind: Eric Gedye and Charles ‘Dick’ Ellis, both of whom worked in some capacity for Thomas Kendrick, the head of the SIS station in Vienna, in 1933. It would have required such a presence for the person to be that intimately familiar with both Edith Tudor-Hart (Edith Suschitzky until she married Alexander Tudor-Hart in Vienna in August 1933) as well as the notorious Haasze. Yet there must be a major question-mark against both candidates.

(I should add that the journalist E. H. Cookridge could conceivably be considered a candidate, since he was born Edward Spiro, and that surname would fit. But I discounted him for several reasons: 1) It is unlikely that Cookridge, a foreign-born journalist, would have been welcomed easily into the interrogation halls of MI5; 2) He would probably have been known as ‘Cookridge’, not ‘Spiro’, at that time, since he published books in the late 1940s under that name; 3) He had surely not been embedded enough in intelligence in Vienna in 1933/34 to know Haasze; 4) Since he had been the most closely involved with Kim and Litzi in Vienna, he could hardly have got away with implying that he did not know about their marriage; and 5) Given his knowledge of Philby’s visits to the Soviet Embassy in Vienna, he would probably have volunteered such information in the wake of the Burgess-Maclean fiasco. Of course, if he were the interviewee, he may have done just that, but such insights might simply have been omitted from the transcript.)

Gedye was a journalist who had at one time worked for the Times and then represented the Daily Telegraph and the New York Times. Yet he was also an MI6 asset, passing on intelligence to the Vienna head-of-station, Thomas Hendrick, and, when Kendrick was eventually arrested in 1938, Gedye reported instead to Claude Dansey as part of the Z network. The main challenge to the theory is the fact that Gedye had been intimately familiar with both Litzi and Kim: he must otherwise have been dissimulating grossly to Martin and the Colonel. According to Boris Volodarsky, it was Gedye who welcomed Philby in Vienna by immediately recommending him as a lodger with the Kohlmann family, and Kim famously, by his own admission, took several suits from Gedye’s wardrobe as clothing to help his oppressed colleagues.

Gedye was in fact an accomplished political analyst with strong left-wing persuasions. He wrote Fallen Bastions (titled Betrayal in Central Europe when published in the USA in 1939, as my copy shows) and in his despatches was reported to have exerted a strong influence on Winston Churchill. Yet there was something very paradoxical about him. His Wikipedia entry includes the following statement: “In Vienna he became known among colleagues as ‘The Lone Wolf’ for keeping a certain distance from the group of Anglo-Saxon correspondents who often gathered in the city’s cafés and bars, including Marcel Fodor, John Gunther and Dorothy Thompson.” That strikes me as somewhat phony, as if Gedye himself were promoting that impression. In his book about Kim Philby, The Third Man, E. H. Cookridge wrote:

There were in Vienna several permanent British newspaper correspondents; their doyen was the genial and omniscient Eric Gedye, who had represented the Times since 1926 and was now working for the Daily Telegraph and the New York Times. These and other British and American journalists had made the Café Louvre their regular haunt, where they discussed the situation.

Gedye presided at these gatherings. Every afternoon and evening he received some furtive visitors, who darted in and out of the café, and imparted to him whispered messages. They were leaders and members of the illegal socialist groups, who has sprung up immediately after the putsch.

Some ‘Lone Wolf’. Moreover, Cookridge was one of those who gave information to Gedye. And it was at the Louvre that Cookridge met Kim Philby, who sometimes brought with him a woman whom he introduced as his fiancée, even though they had been married a fortnight after the putsch, on February 24. Thus, if the interviewee was Eric Gedye, he was behaving as ingenuously as Martin was acting obtusely. If, as he had claimed, the name ‘Philby’ meant nothing to him until the Burgess and Maclean affair, it was a monumental dissimulation: he must have earnestly wanted to conceal any connections, and he must have imagined that his interlocutor would not have the knowledge or the means to penetrate his deceptions. A riposte would be that this exchange shows that the interviewee was not Gedye, since the man in question was evidently unacquainted with Philby, and, despite his close relationship with Litzi’s close friend Edith Tudor-Hart, had not been informed about his marriage to Litzi until 1951.

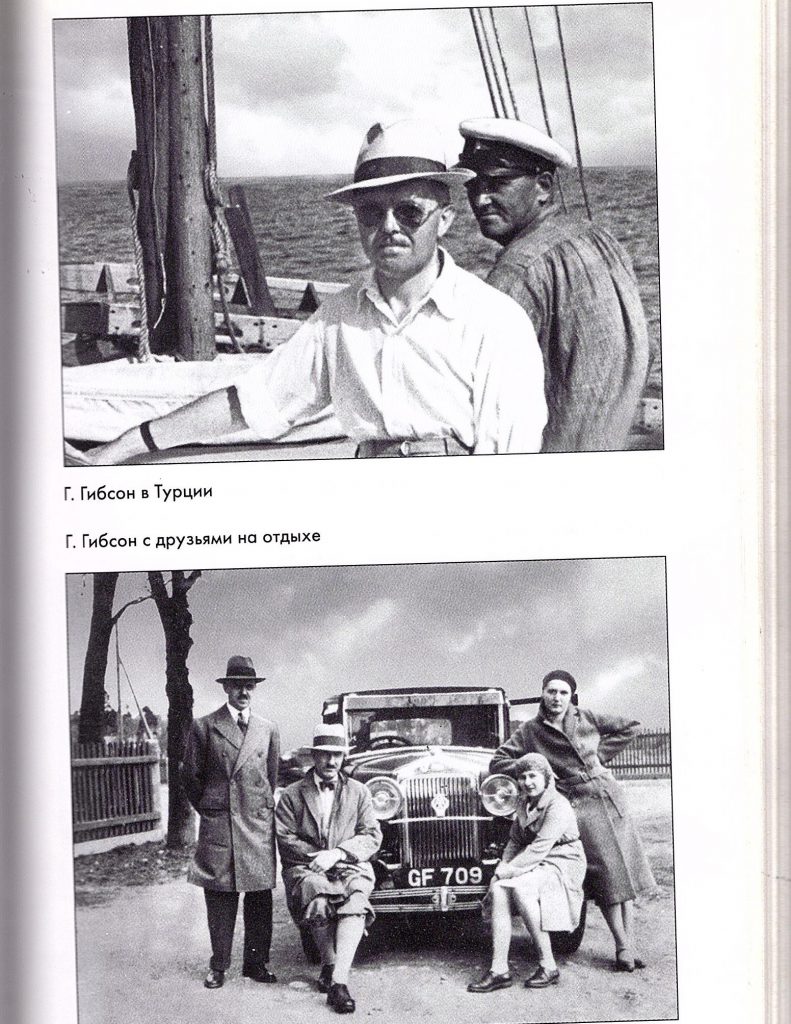

One important factor working against Gedye’s being the interviewee is chronology. According to his ODNB entry, Gedye spent the later war years with his future wife (also called Litzi) in Turkey and the Middle East, working for SOE. They were arrested by the Turkish police in 1942, released shortly afterwards, and relocated to Cairo. After the war, he apparently returned to Vienna, reporting for the Guardian, and was appointed bureau chief for Radio Free Europe in 1950. So it seems improbable that he could have mixed socially with Litzi Philby and Edith Tudor-Hart in London between 1944 and 1946, or have been available for an impromptu interview in October 1951.

Irrespective of the timeline, the proposition has its own absurdities. How could Eric Gedye, having introduced Philby to Litzi, and assisted Kim in his underground activities, not have heard about Philby and his marriage? After all, Hugh Gaitskell and his future wife Dora, Muriel Gardiner, John Lehmann, Stephen Spender, Flora Solomon, Naomi Mitchison, Teddy Kollek – and probably many others – all knew about what Philby was up to in Venna, and of his very public marriage to the communist Litzi. The scenario is preposterous either way. . (For my account of the adventures – amorous and otherwise – of Muriel Gardiner and Stephen Spender, please see the March 2016 piece, Hey, Big Spender!.)

So perhaps the mystery man was Dick Ellis? Yet that hypothesis contains its own paradoxes. Dick Ellis was a scoundrel in his own right, although the indictment of his career, recorded in Stephen Dorrill’s MI6, as well as in Nigel West’s Dictionary of British Intelligence, comes predominantly from Peter Wright in Spycatcher, and various writings of Chapman Pincher. Care is thus required.

Ellis was certainly working officially under Kendrick in Vienna in the early 1930s, so his testimony concerning Haasze can be regarded as authentic. Yet exactly the same criticisms of his statements that I have made about Gedye apply: how could a person in such a position be ignorant of the Kim/Litzi shenanigans, or expect to get away with denying any knowledge of them to an MI5 interrogator, unless the latter were an absolute greenhorn, or were contributing to a cover-up himself? Moreover, Ellis came under suspicion himself in the nineteen-fifties, in a case that has so many twists that it makes the head of the most patient sleuth spin.

The career of the four-time married Ellis is an extraordinary story of mis-steps and indulgence. He was born in Australia, and educated at Oxford. After the First World War, he was recruited by MI6, and posted to Berlin in 1923. He then moved to Paris where, like many of his colleagues, he made the bad judgment of marrying a White Russian woman – his betrothed bearing the name Zilenski. Yet this woman was connected to an agent named Waldemar von Petrov. Walter Krivitsky, the GRU defector called to London in January 1940, actually informed Jane Sissmore of MI5 that the GRU had recruited Petrov, who was working for the Abwehr, shortly before the war. Dorrill picks up the story:

When an Abwehr officer was interrogated after the war, he confirmed that von Petrov had claimed to have had an excellent source of information inside MI6. He said that he had worked through an intermediary called ‘Zilenski’, whose source, ’Captain Ellis’, had supplied documents revealing MI6’s ‘order of battle’ and information about specific secret operations, including the tapping of the telephone of the German ambassador in London, von Ribbentrop. Disturbed by the allegations, MI5 sought permission to interrogate Ellis, but MI6 refused, contemptuously dismissing the allegations by suggesting that the German officer had faked the evidence.

Could Martin have been unaware of these events? Dorrill’s account suggests that the aborted investigation occurred soon after the war, but Peter Wright indicates that MI5 began to re-evaluate Krivitsky’s depositions seriously only after the Burgess/Maclean defections in 1951 – that is, at exactly the time of the Martin interview. Yet Wright’s chronology is typically loose. He wrote, after describing how MI6 had rejected the possibility that Ellis could have been a spy:

In any case, Ellis had opted for early retirement, and was planning to return to Australia. Dick White, newly appointed to MI5 and not wanting to aggravate still further the tensions already strained to breaking point by the gathering suspicions against Philby, agreed to shelve the case.

Ellis, who headed MI6 in Singapore, retired to Australia in 1953. (Wright also wrote: “Within a year of Philby’s falling under suspicion Ellis took early retirement, pleading ill-health”, which is also incorrect.) 1953 was the year White became MI5 chief, not ‘newly appointed to MI5’. If, indeed, MI5 did not pick up the Krivitsky threads until the time of the White regime, it might, however, explain how MI6 was able to fob off an unsuspected Ellis to MI5 in October 1951.

Wright’s account of the investigation into Ellis (pp 325-330) is fascinating otherwise, and one of the most convincing sections of his book. The fact is that Ellis eventually (much later, the date is not given) confessed – in the same room where Martin carried out his interview – to passing on secrets to the Abwehr, through his brother-in-law, when under financial pressures. He also came under suspicion of being a Soviet informant, perhaps being blackmailed by Russian Intelligence because of his known Abwehr connections. Contributory photographic identification was gained from the widow of Ignace Reiss, Elizabeth Poretsky, and from Mrs. Bernharda Pieck (the wife of Henry Pieck, the Dutch agent of the GRU, who had worked for Reiss), but Ellis was not conclusively pinned as such.

The dates fit much better for Ellis. He worked for British Security Coordination in New York and was appointed head of the Washington office in 1941. He spent some time in Cairo in 1942, rejoined BSC later that year, and then returned to London in 1944. Thus he would have been around to renew his contacts with Edith Tudor-Hart, as he described them. And if, indeed, the revivified investigation into the Krivitsky files did not take place until 1953, he would have been a safe choice by MI6 to condescend to speak to MI5 and lie on behalf of the service. Yet the same urgent questions apply to the lack of disciplined follow-up by Martin and the Colonel. Why did they not interrogate the interviewee about his admitted interactions with the two women, and why did they not challenge the contradictions in his story? Why did Martin’s boss, Dick White, not challenge the officer over his inept performance, and why did MI5 post such a damaging report in the archive? Whoever the mystery interviewee was, this entry looks like an elaborate charade.

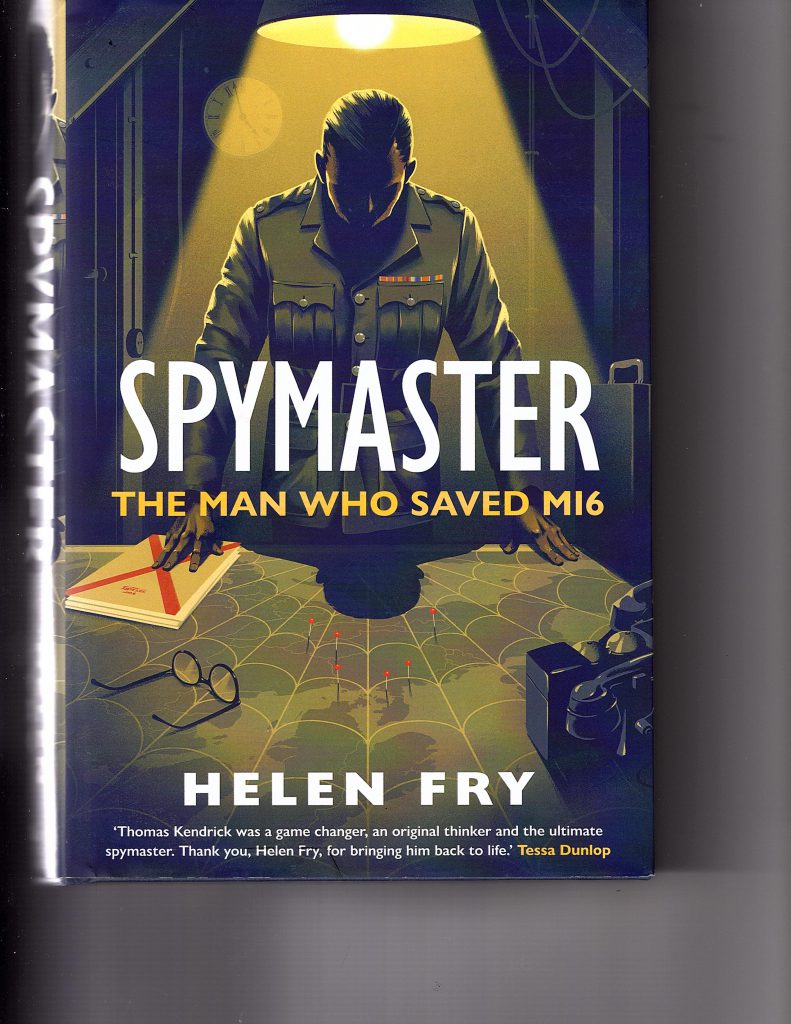

Helen Fry & ‘Spymaster’

One writer who has questioned the activities of MI6 in Vienna at this time is Helen Fry. The revision of her biography of Thomas Kendrick, Spymaster is sub-titled The Man Who Saved MI6, and it was issued in 2021. As I have written before, it is in many ways an irritating book, containing too much irrelevant material and unexplained asides, and stylistically very clumsy. For example, it suffers from overuse of the passive voice (‘it is believed that’, ‘it is thought that’) with the result that the reader has no idea which persons are responsible for various activities and opinions. Yet Fry has read widely, and is prepared to stick her neck out in admirably unconventional ways when dealing with paradoxical information. In this respect, she finds much that is bizarre in the conduct of Philby, Ellis and Kendrick during the frenzied events of 1933-1934 in Vienna.

Since Kendrick had proved himself to be a very adept spymaster, and had shown an ability to penetrate communist networks, Fry finds Kendrick’s lack of interest in Philby’s associations with Litzi quite astonishing, and wonders to herself why had Kendrick not been tracking her before Philby arrived on the scene. She introduces the hypothesis that Philby may actually have been given the task to infiltrate Communist networks rather than being coincidentally led to Litzi by Gedye. She supports this theory by mentioning that E. H. Cookridge noted that Philby had made contact with two figures at the Russian embassy in Vienna, one of whom, Vladimir Alexeivich Antonov-Ovseyenko, was suspected of being a Russian spy’. (He was later to supervise activities for the Soviet mission in Spain during the Civil War before being recalled and executed in the Purges.) Cookridge in fact claimed that Philby told him he could get money to help the socialist groups that Cookridge worked with, and he concluded:

The money which Philby offered could only have come from the Russians, and the last thing my friends and I wanted was to accept financial help from Moscow. Philby was told this in unmistakable terms and our relations with him and his friends came to an abrupt end.

Yet no breach with Kendrick occurred, nor any reprimand. “Could the spymaster have instructed Philby to get close to members of the Russian embassy there? Was Philby, in fact, one of Kendrick’s agents?”, writes Fry. She thus ventures the possibility that Philby was sent to Vienna in 1933 to penetrate the communist network for SIS, and uses this conjecture to explain the indulgence of SIS, in 1940, over the fact that their new recruit had an overtly communist wife. It would also explain Philby’s apparent insouciance during the war concerning a divorce. He may have believed that he did not have to distance himself from Litzi so demonstrably, since his bosses knew the real story.

Even if that were true, however, Philby did not have to further his enterprise to the extent of marrying Litzi, an action that gives a whole new dimension to the notion of penetration. And that union may have been directed as a Soviet counter-thrust: have Litzi seduce a naïve Englishman, and then marry him, in order to allow a valiant female agent to become installed legitimately in Great Britain. After all, Litzi already had a firm CP and agent pedigree: she had been the mistress of Gábor Péter, a communist activist from Hungary who (according to Philp Knightley) was the first officer to recruit her. The Soviets had already accomplished the same objective with Edith Suschitsky, and, of course, Ursula Kuczynski would (in 1940) become another famous beneficiary of marriage arrangements that granted UK citizenship to women who took advantage of it to set about undermining their adoptive country.

A Fragile Marriage

Neither Kim nor Litzi expected the marriage to last long. According to Seale and McConville, Kim informed his parents, when writing to them about the event, that he expected the marriage to be dissolved ‘once the emergency was over’ – a strange formulation that perhaps suggested that he thought that Litzi would before long be able to return to Austria. Litzi declared that she had held some true affection for her husband, but she was in no two minds about the precipitate course of events, and for what purpose the two of them had been united. Predictably, Litzi was not warmly welcomed by Kim’s mother at Acol Road in Hampstead (his anti-semitic father being in Saudi Arabia at the time): she found Litzi too strident and showy, and the fact that she was Jewish, a communist, and a divorcée did not help her cause.

And Kim needed a job. While his left-wing ideas blocked him from a civil service career, he looked for a post in journalism, and in the summer of 1934 (or maybe early in 1935) was appointed editor of Review of Reviews. Meanwhile, Litzi socialized regularly with other Austrian communist exiles, such as her close friends Edith Tudor-Hart and Peter Smolka, whom both she and Kim had known from Vienna. What is surprising about this period is the nonchalance with which both went about their business, Litzi mixing with friends who were being watched by MI5, and Kim collaborating with Smolka to set up a press agency, the London Continental News, Inc. It would appear that, at this stage, Kim did not have a clear idea as to how he could be useful to the Communist cause.

By the end of 1934, Kim had been officially ‘recruited’ by Arnold Deutsch. The accounts of this engagement have been grossly melodramatized over the years: Edith Tudor-Hart has been identified as being the queenpin in the operation to spot new recruits, but it all seems rather ludicrous. Anthony Blunt famously named Edith as ‘the grandmother of us all’, but it is hard to reconcile such a categorization with the frail, neurotic, exploited and clumsy woman who could not even carry out her photographic business without drawing hostile attention to herself. It is far more likely that Blunt described her as such to distract attention from Litzi herself. Moreover, Deutsch had known Litzi and Edith in Vienna: Borovik claims that he had ‘recruited’ Edith back in 1929, and that Edith ‘recruited’ Litzi as MARY in 1934, after which Edith talent-spotted Philby. Yet, according to what Philby told Borovik, he had also known Deutsch in Vienna. Why did Deutsch therefore have to undergo such clandestine efforts to meet Philby and check him out?

After his formal recruitment at the end of 1934, Philby was told (via Edith) to keep away from party work in London, and to distance himself gradually from his ideological background. Thus Philby began to recommend his Cambridge friends, more suitably placed and with less obvious drawbacks in their curricula vitae, for conspiratorial work while his own career was still in limbo. Yet Philby was obviously not ordered to separate from Litzi at this time, an omission in policy that seems quite extraordinary: in fact they spent the summer of 1935 together on a holiday in Spain. One interpretation could be that the NKVD at this stage considered Litzi a much more vital asset than Kim, even if she was public in her affiliations. Significantly, Nikolsky (known as Orlov), who for a few months in 1935 was a rezident at the Soviet embassy in London, observed that ‘with such a wife, Philby had hardly any chance of getting a decent job.’ Volodarsky notes that no-one expected him to be able to join the secret service, and thus be of use to his masters.

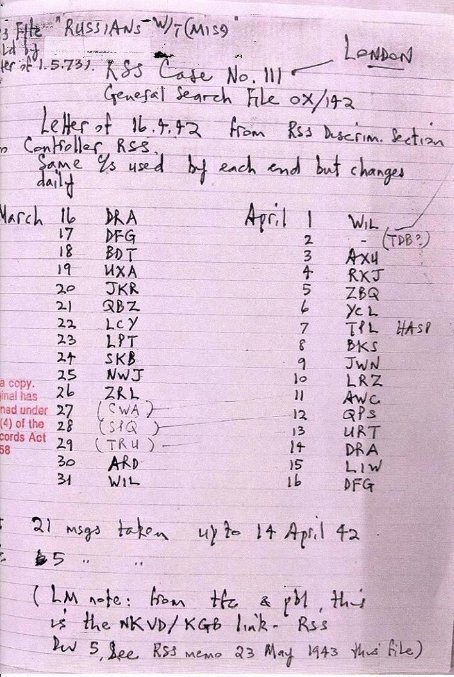

Litzi, as MARY, continued to be busy, and Nigel West has identified her in the clandestine wireless traffic between the Comintern and its agents in London that was picked up and decrypted by the Government Code and Cypher School. While some of the references to MARY in the transcripts seem to denote a male character, one entry for November 7, 1934, appears to point incontrovertibly to Litzi:

ABRAHAM: ‘MARY has arrived safely and she asks you to take special care of her artist friend who you will meet and who is a very special person.’ HARRY.

As West observes: “If MI5 had succeeded in linking MARY to Litzi Friedman, and then connecting her to Kim Philby, his subsequent career might have taken a rather different course.”

Kim started his gradual process of moving to the right, and distancing himself from his communist connections. This strategy had both public and personal aspects. Edward Harrison informs us that a friend from Westminster School, Tom Wylie, introduced him to a businessman named Stafford Talbot, who was planning a journal focussed on Anglo-German trade. (Historian Sean McMeekin states that Wylie was the agent named MAX, who supplied information to Burgess and Philby from the War Office.) Both Talbot and Philby joined the Anglo-German Fellowship, a move that was designed to provide his Soviet bosses with intelligence on covert links between the German and British governments. As Phillip Knightley wrote:

Philby had worked so enthusiastically part-time for the Fellowship that in 1936 it offered him a full-time job. He was to start a trade journal, which would be financed by the German Propaganda Ministry, and which would have the aim of fostering good relations between Germany and Britain. Philby flew to Germany several times for talks with the Ministry and with the Ambassador in London, von Ribbentrop.

Yet this initiative stalled, as the Fellowship selected a rival publication as its outlet. The Anglo-German Review was launched in November 1936. While Knightley judged that, despite that setback, ‘Philby’s control must have been pleased with him’, Edward Harrison claimed on the other hand that, since Philby’s efforts to secure Nazi financial backing for his trade journal had failed, ‘by the end of 1936, Soviet intelligence described the situation as a fiasco and Philby’s attempts to spy on unofficial Anglo-German relations had yielded little’. It was a very tentative start by Philby to a career in espionage, and his bosses had to look for a new role for him. Moreover, the presence of his Jewish, communist wife was a permanent handicap. In June 1936, Philby divulged to his old coal-miner friend Jim Lees that he would have to get rid of Litzi. Lees stormed out of his house over Philby’s attitude towards Germany and his proposed treatment of his wife.

What is extraordinary about this period is the amount of travel that Litzi was undertaking – activities that MI5 was apparently watching closely. When Helenus Milmo interrogated Philby in 1951, he presented him with the following dramatic description:

He further concedes that his wife had no resources of her own and was earning no money. Nevertheless, it appears that between 6th March 1934 and 15th April Lizzie Philby made no less than three journeys into Czechoslovakia from Vienna on her British passport which she obtained two days after her marriage. Philby is unable to explain the purpose of any one of these visits. On their return [sic] to England, she went to France on 4th September 1934 and entered Spain on the following day. Ten days later she left a French port and on 21st September 1934 she entered Austria where she remained over a month. On 8th April 1935, she paid a week’s visit to Holland and on 16th August she arrived in France, entering Spain on the following day. On 3rd April 1936 she entered Austria and a week later went on to Czechoslovakia, returning to Austria again on 22nd April. Between 25th May 1936 and 22nd July 1936, she made a visit by air from this country to Paris and on 22nd July and 28th December 1938 she made further journeys across the channel.

Philby must have been crushed by these revelations, but admitted nothing. Yet what is perplexing is why these peregrinations drew no attention at the time. Were the facts collected only in retrospect? If she had been tracked closely at the ports during this period, one might have expected MI6 to have been invited to investigate who her contacts were in all these places.

Kim’s First Spell in Spain

In February 1937, on the instructions of Theodor Maly, Philby travelled to Spain, in an endeavour to breach General Franco’s security, and to determine how he might be assassinated. At some stage after that, Litzi left the UK for France. The role of Litzi in supporting Philby’s exploits in Spain, by acting as a courier to take messages from him to Soviet controls in Paris is, unsurprisingly, a not well-documented one, and pinning dates on their encounters is a very hazardous exercise. The primary source for events at this time is Genrikh Borovik’s Philby Files, but that work – by a planted KGB officer – is severely impaired by Philby’s own dissimulations in speaking to Borovik, the latter’s gullibility in accepting what Philby told him, the confusing information in the NKVD files, Borovik’s own unfamiliarity with the personages involved, his lack of foreign languages, and his inability to bring any discipline to his analysis. Matters were further complicated by the consequences of Stalin’s Purges, whereby several agents who had recruited or controlled Philby and his colleagues had been executed, with a loss of ‘corporate memory’, and a distrust of anybody who might have been recruited by such counter-revolutionaries and ‘foreign spies’.

Philby’s first visit to Spain was brief, for about three months, when he travelled as a freelance journalist, with letters of accreditation from The London Central News and the London International News Service, as well as from the Evening Standard. His status was not fully trusted by Moscow Centre. Maly reported that Soviet Intelligence in London (maybe the GRU) had discovered papers in Philby’s flat in London that suggested that he was working for the Germans. Maly had to clarify matters for Moscow, and rebuke Philby on his return. The major incident during this period, however, was when Philby was arrested, and had to surreptitiously swallow some paper containing his secret codes for communicating with Paris.

At this time, Philby was sending out information, written in invisible ink, in letters to a Mlle. Dupont in Paris. (Philby was later to discover that the address to which he sent these letters was in fact the Soviet Embassy – an atrocious piece of tradecraft that, if Franco’s intelligence had been on the mark, would have ensured his death.) Borovik implies that Litzi received these missives, as he was accustomed to receiving quick responses from ‘MARY’. But, when Philby wrote requesting a new dictionary, the response came not from MARY but from Guy Burgess, who suggested that they meet in Gibraltar. And here, Borovik starts to trip over his own details, writing: “As for Mary, he never saw her again”. Awkwardly, there were two MARYs in Philby’s domain. The first (according to what Philby told Borovik) had been a Russian woman whom Maly had introduced him to in London, a good-looking woman in her twenties, who was designated as being the person he should contact in an emergency. But it hardly makes sense that messages would be sent via Paris to MARY in London, with responses being able to be sent thence by her frequently and openly to him in Spain. Moreover, that would have undermined the whole point of an ‘emergency’ contact. Philby makes no mention of this association in My Silent War. This was surely an invention by him, and probably designed to confuse Borovik (which he did) and divert attention from the true MARY.

Indeed, in a letter to Moscow Centre dated March 9, 1937, Maly briefed his bosses about the slowness of the mails, since ‘the censors hold on to the letters for a long time’ (so much for Philby’s statement that ‘he didn’t have to wait long for an answer’), and indicated that he needed help from a cut-out to get the nature of the current assignment (the assassination of Franco) to their man. He mentions a woman candidate, INTOURIST, but she is unwilling to travel, as she would be too conspicuous. Moreover, she and Philby have never met (so she could not have been the London or the Paris MARY). So Maly suggested that Litzi, who would have a valid reason for contacting her husband, should try to arrange a meeting, and also carry the murder equipment with her. Even more confusingly, he states that he will refer to Litzi as ANNA.

Yet, according to what Philby told Borovik, by April 9 Maly had found a new candidate for emissary – Guy Burgess. Exactly what Burgess brought with him to Gibraltar is not clear, but Philby had neither the means, the gumption nor the opportunity to attempt to kill the Nationalist leader. And, if he had tried, it would have been a disastrous failure and a colossal embarrassment. Whether this emissary really was Burgess must be questioned: Philby may again have been trying to minimize his wife’s involvement. Litzi’s daughter, Barbara, wrote that her mother told her that she and Philby ‘met in hotels in Biarritz or Perpignan, and even in Gibraltar, where he gave her information that she then carried to her control officer in Paris’.

What it does suggest, however, is that Moscow did not think highly of the enduring value of Philby (now known as ‘SÖHNCHEN’ – SONNY) for their cause – risking his life in two ways, one, by encouraging him to send incriminating letters to France, and two, by encouraging him to sacrifice himself in a probably hopeless assassination attempt. (Ben Macintyre, rather incongruously, regards this fiasco as evidence of Philby’s ‘growing status’ in Moscow’s eyes.) Philby left Gibraltar at the end of April ‘with his tail between his legs’, as Edward Harrison writes. Maly informed Moscow that Philby had returned on 12 or 13 May ‘in a very depressed state’ because of his ineffectiveness. Maly was, however, able to direct Philby to write some attention-grabbing article about the Spanish situation for the Times, an initiative that sealed the next stage of Philby’s career. As for Maly, that was his last act before being recalled to Moscow, to be shot.

Borovik adds that when Philby arrived in Southampton, Litzi was there to meet him, and he notes: “In Kim’s absence Otto [Deutsch] had maintained constant contact with her, and so she could tell her husband when he could meet his Soviet colleague.” This, again, is puzzling. Had Litzi been in the United Kingdom all this time, and not sending replies to her husband from France? Alternatively, how had Deutsch managed to stay in constant contact with her over a three-month period?

Kim’s Second Spell in Spain

Philby’s successful articles, submitted to the Times, had gained him a permanent appointment with the newspaper on May 24, 1937. It is probable that Litzi moved, semi-permanently, to Paris soon thereafter, in the summer of 1937, staying there until early in 1940. So was Litzi acting as a courier for her husband when residing in Paris? The mainstream biographies of Philby are very vague about his methods of communication with his controllers: Harrison is the most careful, but when he writes:

Before Philby returned to Spain, Deutsch explained the schedule for future meetings with his spymaster. Once a month Philby was to cross the border into France and take the train from Bayonne to Narbonne, where he would meet his contact and provide both a written and an oral report. This contact turned out to be Alexander Orlov, whom Philby had already met in England.

Harrison’s source is stated to be Knightley (p 66). But Knightley says no such thing: all he writes is (on p 60):

Philby would make an excuse to The Times for a visit across the border, to Hendaye, the town astride the frontier, or to St Jean de Luz, where most of the correspondents took their leave periods. These places seethed with gossip and intrigue, and were thus not only convenient for passing of information but for gathering more.

Moreover, Orlov would have been a very unlikely courier. He had been appointed head of the NKVD operation in Spain in February 1937, and was busy exterminating Stalin’s enemies.

Seale and McConville are similarly vague, describing the sorties into Hendaye, but veiling their ignorance with colourful digressions, such as an account of the dancing skills of Philby’s new lover, Frances Doble. Burgess is re-introduced as his contact, without any source being given:

His orders were to transmit his information by hand to Soviet contacts in France or, in the case of urgent communications, to send coded messages to cover address outside Spain. This fitted in well with the pattern of his movements as a journalist, and it was one of his regular excursions to the Basque country that he again met Guy Burgess who, Kim later revealed in his book, brought him fresh funds.

Just like that. This seems simply a careless transposition of dates, with no attention to chronology.

Thus I have to return to Borovik to try to establish what role Litzi played as a cut-out. Borovik suggests that Philby sent over a report ‘with Guy Burgess’ in mid-1937 that reached Moscow. That may however be a misunderstanding of how it actually reached his colleague. After Philby’s near-death in a bombing incident, and his commendation by Franco, Moscow was apparently ‘pleased by the information coming from SONNY’, Borovik noting afterwards (probably based on what Philby told him) simply that Philby turned in his monthly or bimonthly report to his Soviet colleague. Yet Philby spun Borovik a tale when the latter asked him whether Litzi knew about his affair with Frances and whether she worked with him:

Yes, she knew about my work for Soviet intelligence. She was a good friend. When we moved to London from Austria and I started working for the KGB, she was in a delicate situation. She had to break her ties to the Left, like me, stop working with the Communists, otherwise she would compromise me. But it was too great a sacrifice for her. I understood. We discussed the whole problem calmly and decided that we would have to separate. Not right away, but as soon as there was a reasonable opportunity.

This is vain and sophistical nonsense. It exaggerates Philby’s standing at the time. It ignores the facts, since Litzi was not easily able to shed her persona, nor did she attempt to. They could have separated immediately, if they had been so ordered. Their personal lives were not carried on at their own discretion and preferences. Philby was again trying to conceal his wife’s role.

Indeed, Philby’s account of his contacts with his Soviet handlers/cut-outs is both contradictory and absurd. He claimed that, before his second departure to Spain, he was told that he would take the train from Bayonne to Narbonne, two or three weeks after his arrival, and meet his man there. The figure would be Orlov, whom he knew from London, and he was scheduled to meet him once a month, to hand over written and oral reports. They met at the railway-station square in Perpignan, and Orlov got out of a big car, very obvious in a bulging raincoat, and they chatted carelessly for a while, as Orlov told him of his exploits in ‘suppressing’ the Trotskyite organization.

This is like a scene from a bad movie. To think that the chief executive of the NKVD in Spain would so brazenly step out in a public place to spend hours chatting to a reporter associated with the Nationalists, is beyond belief. It was all part of a game by Philby to boost his reputation, and give him a chance to offer an opinion on the loyalties of Orlov (who defected a year later, having performed a remote deal with Stalin not to reveal anything.) Moreover, it goes completely against the grain of what the official story was. A few pages later, Borovik writes:

According to the documents, when Philby came to Spain for the second time in the summer of 1937, he did not have a meeting with Orlov right away. His first contacts with the Centre were apparently through ‘Pierre’ (Ozolin-Haskin, from the French residence, later shot in Moscow).’Pierre’ would take the materials from Kim and bring them to Paris, from where they would be sent on to Madrid (sometimes via Moscow).

Borovik adds that this process was very slow, and that, in September 1937, Philby would meet Deutsch in the lobby or café at the Miramar Hotel in Biarritz, as Maly had suggested, where Deutsch would tell Philby that he would be working with Orlov. But Maly was dead by then. In addition, Borovik later undermined his own shaky testimony by pointing out that Ozolin-Haskin did not take over the Paris rezidentura until some time in 1938, replacing the anonymous ‘FIN’. A farrago of disinformation.

Litzi in France

So did Litzi play a role here? In another flight of fancy, Kim informed Borovik that Litzi was spending her time in France by attending the university in Grenoble, but that was not the life as Litzi herself recalled it. She did explain to her daughter that his mission in Spain ‘had been the first real assignment that the Soviet espionage service had given him’, and that she had therefore taken an apartment in Paris so that she could be his cut-out, his intermediary. In fact she spent most of her time partying – and having fun with her new Dutch lover, an artist.

Yet this rather hedonistic period was interrupted by a very bizarre event that needs to be noted first. I believe it was first recorded by Seale and McConville (1973), and then echoed by Knightley (1988), that Litzi returned to Vienna in 1938 to exfiltrate her parents and bring them to London. Neither author gives a source for this story, or explains under what conditions the venture was able to take place. It is presented as if it were more in the nature, say, of a day-trip down to Worthing to bring the aged Ps up to the Metropolis. To accept that Litzi could have somehow contacted her parents and gained their assent, returned without fear of arrest to Vienna, convinced the authorities to grant them an exit visa, to have prepared the Home Office in London to allow them entry and permanent residence, and then fund and arrange their travel before herself returning to Paris, all without noticeable alarm from MI5 or the Home Office, stretches one’s credulity to absurd limits. Was this story really true?

I doubted it, until I started to explore ancestry.com and other records of detained aliens in 1939.

The registers are a little confusing, since there was more than one Israel Kohlmann who escaped to England at this time, but I eventually found the proof I needed – two death certificates from 1943. Adolf Izrael [sic] Kohlmann is registered as dying in Bishop’s Stortford, Hertfordshire, in April 1943, although his birthdate (December 31, 1868) is here given incorrectly, reflecting another refugee of the same name who was born in Nűrnberg, Germany in 1879. (I am confident about this analysis, although as I returned to verify, I could not trace my exact steps.) The death of Izrael’s wife, Gisella (nee Fűrst) Kohlmann, who was born on April 14, 1884, occurred in July 1943, in Amersham – her name is incorrectly listed as ‘Kollmann’. Moreover, an item in the Appendix to Helenus Milmo’s report on Philby in early 1952 (FCO 158/28) runs as follows:

In 1939, Lizzie’s mother, in an application to the Aliens’ Tribunal for release from restrictions, stated that PHILBY was paying £12 per month towards her maintenance.

MI5 was clearly keeping a close eye on the activities of Litzi and her clan at this time.

What were Litzi’s parents doing in the heart of what would become Philby country, either side of St Albans? How could they have been ceremoniously dumped in the British suburbs, with their daughter returning to France, and their son-in-law in Spain? Their escape must have had assistance from MI6, but the lack of curiosity on the part of the traditional historians in this remarkable exploit is to me dumbfounding. And what caused their deaths, in that same summer of 1943, in towns separated by a few miles? I am tempted to order up their death certificates, but I wonder whether any coldspur reader can shed light on this strange episode.

Meanwhile, our communist heroine was living it up. As she told her daughter:

Soon after my arrival in Paris, I collected a group of artists around me, painters and sculptors, students of Maillol, mostly Hungarians or Dutchmen. The Hungarians were terribly poor, the Dutch relatively well off, but at that time I was quite well off, since I was picking up a check every month at Lloyd’s, Kim’s salary from the Times, with which I maintained the apartment. Never again in my life did I live in such grand style and toss money around that way – it was all great fun. I bought clothing and hats – you know my passion for hats – big hats with wide brims, with feather boas, dernier cri, nouvelle collection! And my artist friends gave me paintings, pieces of sculpture, and drawings. And that’s when I bought the two Modigliani drawings that got lost along with all the other things somewhere in London, sometime or other, with all the moving from one place to another during the Blitz.

That observation about her husband’s salary was utter nonsense, of course: the NKVD was funding her very lavish lifestyle, but would eventually claw back on such self-indulgence. Ozolin-Haskin (‘PIERRE’) confirmed her occasional role as a cut-out. When the newly installed officers in Moscow Centre, mystified as to who these agents were, asked about SÖHNCHEN and MARY, PIERRE wrote, on December 25, 1938, that MARY was SÖHNCHEN’s wife, that she worked as a messenger, and was ‘totally aware of the work of SÖHNCHEN, MÄDCHEN [Burgess] (despite the fact that I meet MÄDCHEN separately), and many other people whom she knows from her old work in England.’

After this, the trail becomes very confused. According to a report in late March 1939, Philby apparently met Maclean in Paris, and complained about the irregularity of communications. Pavel Sudoplatov in Moscow Centre questioned why no materials had been received from SÖHNCHEN. Gorsky (‘KAP’, the new rezident in London) then entered the stage, but Borovik declares that he was soon shot as a Polish spy. That was not true, and Gorsky survived to have an illustrious career in London and the United States, where he was honoured to have clandestine meetings with Isaiah Berlin. PIERRE, before he was hauled back to his death in Moscow, had again to explain who MARY was, and that she was most easily reached through MÄDCHEN. KAP then took over, and had to confess his bewilderment in a message of July 10, 1939:

MARY raised the question about paying EDITH. I asked her to write about it and I am sending you her letter. I know nothing about this case, and your instructions would be highly appreciated . . . MARY announced that as a result of a four-month hiatus in communications with her, we owe her and MÄDCHEN £65. I promised to check at home and gave him £30 in advance, since she said they were in material need . . . MARY continues to live in the SCYTHIAN’s country [identified as ‘the OGPU residence in France’] and for some reason, she says on our orders, maintains a large apartment and so on there. I did not rescind those orders, since I do not know why they were given; however I would ask that you clarify this question.

Litzi, if she had been a messenger, had clearly not been a very frequent or effective one, and was living high on the hog in the meantime. A few days later, a sterner reply was sent by Moscow, after someone had presumably performed some homework in the files:

Inform KAP that at one time, when it was necessary, MARY was given orders to keep an apartment in Paris. That is no longer necessary. Have her get rid of the apartment and live more modestly, since we will not pay. MARY should not be paid £65, since we do not feel we owe her for anything. We confirm the payment of £30. Tell her that we will pay no more.

It looked as if the sybaritic days were over for Litzi, and she would have to behave like a good Communist again. Meanwhile, the Centre also concluded, from deeper investigation of its files, that it did have a good assessment of SÖHNCHEN, who was ‘very disciplined’. It admitted that ‘communications with him were very irregular, particularly of late.’

The functions of the NKVD residences in Paris and London between 1937 and 1939 are overall very puzzling, as unnecessary travel seemed to be involved in getting messages to Moscow when more local approaches might have worked better. In London, there was a hiatus between Deutsch’s return to the Soviet Union, and Gorsky’s appointment in December 1938, during which an incomplete transition to the ineffectual Grafpen took place. Guy Burgess (for example) was handled by Eitingon in Paris until Gorsky’s arrival, and he was then shifted to control through London in March 1939. For Paris also had its troubles, with the doomed Ozolin-Haskin also falling into disfavour. That may explain why complex chains of messengers were used in both directions to route important information to Moscow Centre.

The Approach of War

As the Spanish Civil War wound down, with Moscow Centre stabilizing somewhat after the blood-letting, Litzi’s prestige and standing appeared to improve. In June, PIERRE wrote to Moscow with suggestions for how SÖHNCHEN should be deployed, and cited MARY’s recommendation that he should work in the Foreign Office, since his father was now back in the UK, and could presumably grease the wheels for his acceptance. Sudoplatov agreed, but then Borovik goes off the rails. Here occurs the incident over STUART that was the subject of some very useful annotations on coldspur a few months ago. (see Comments following https://coldspur.com/2022-year-end-round-up/)

Litzi had clearly made a visit to London, since KAP (Gorsky) reported, on July 10, 1939, that she had met there ‘one of her intimate friends’, a certain STUART whom, she says ‘we know nothing about’. Had Litzi made the trip back to the UK to meet her husband on his return? Harrison says that Philby left Spain ‘in July’, which hardly allows enough time. (Borovik says ‘late July’.) Yet she obviously felt free to meet with Gorsky, since she followed up by writing a detailed report on STUART, who had already recommended that SÖHNCHEN be considered for a post in ‘the illegal ministry of information’. She also gives the impression that she has seen Philby recently, as she talks about his ties with people in the British Intelligence Services as if they had discussed them in the very recent past.

When I first read this passage, it did not seem to me that the reference to STUART (Donald Maclean’s cryptonym) implied Maclean, as Borovik surmised and puzzled over, for any number of reasons, not least the fact that this STUART was working in London, while Maclean was with the Embassy in Paris. And the dedicated coldspur reader Edward M., who had been diligently trawling round, came up with the name of Sir Michael Stewart (not to be confused with the Labour Minister of the same name) who had been a contemporary of Philby’s at Trinity College, Cambridge, and (as Tim Milne recorded in his memoir) had accompanied Philby on a motor-cycle trip to Hungary in 1930. He would later be appointed Her Majesty’s Ambassador in Greece. Furthermore, Edward quoted a passage from Nigel West’s At Her Majesty’s Secret Service:

By the time Elliott was sent back to Beirut to confront Philby ten days later, he had disappeared. Tim Milne, then at the Tokyo station, was investigated and cleared, although his brother Antony, who had been at the Montevideo station between 1961 and 1965, was fired for failing to have declared a past relationship with Litzi Friedman, Philby’s first wife. A British diplomat, Sir Michael Stewart, who also had shared Litzi’s favours, was rather more lucky, and was appointed to Washington DC before going to Athens as ambassador, and receiving a knighthood.

I was intrigued to know where West had derived this information, and an inquiry from Keith Ellison ascertained that the sources were Peter Wright and that other impeccable functionary, Arthur Martin, MI5’s ‘legendary’ mole-hunter and incompetent interrogator. During the Blunt post mortem in 1980, the Cabinet Office reported that Sir Michael Stewart was one of Blunt’s acquaintances who had been investigated and (though the language is ambiguous) consequently cleared (see PREM 19/3942). The scope of the investigation has not been published.

Stewart remains a very elusive figure, but the connection sheds a little more light on the influential role that Litzi was playing behind the scenes, encouraged to move around between Paris and London in 1939 despite the Centre’s disapproval of her bourgeois extravagances. A likelier explanation was that she was preparing the ground for her husband’s return rather than welcoming him in person, although, if Philby and Stewart had been close friends for years, it seems odd that she would be needed as an intermediary in helping her husband find a job. (In the files on Victor Rothschild recently released by TNA can be found a note confirming Philby’s friendship with Stewart, and the fact that Stewart’s sister Carol was married to another dubious character, Francis Graham-Harrison.) This might explain why a vetting-form for Philby was filled out by SIS on September 27, 1939, as Keith Ellison notes in his e-book at https://www.academia.edu/50855482/Special_Counter_Intelligence_in_WW2_Europe_Revised_2021_?email_work_card=view-paper. On the other hand, Philby’s candidature may have been part of a routine sweep: Valentine Vivian informed Seale and McConville that his name came to SIS’s notice from a ‘pool’ – a list of potential recruits drawn up early in the war.

By then, however, great political shifts had occurred. The Nazi-Soviet Pact was announced, causing great heartache to Stalin’s loyalists in the West, and Britain declared war on Germany. Gorsky’s plans for sending Philby to Berlin or Rome were dropped. Philby arranged an important job for Peter Smollett (né Smolka), whom he had known in Vienna, and on October 9 the Times appointed Philby as Special War Correspondent with the British Expeditionary Force. Harrison suggests that he set out soon after that date, and whatever hopes he had for joining SIS were obviously shelved. Meanwhile, Litzi was apparently stranded in Paris.

This was a difficult period for Philby. In September, he managed to inform the London residency of his mission in France, and Gorsky set up rendezvous arrangements for him in Paris for late October and early November – not with Litzi, but with a representative named ALIM, who did not know him by sight. Philby had been unnerved by the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, and was unable to get away to Paris for his encounter until the back-up date of November 1. He presumably saw Litzi at this time as well, because a 1941 report referred to the disillusionment with Ozolin-Haskin at this time that he had expressed to her. Nevertheless, Philby handed over information about the British Expeditionary Force’s capabilities and equipment that could have been construed as treacherous, given that his Soviet masters might have passed it on to the Germans.

The fact that Litzi was able to regain entry into the United Kingdom, arriving at the port of Newhaven on January 2, 1940, is most intriguing. We owe it to a short item in the Minute Sheet of the personal folder of Kim’s father (KV 2/1181-1) for the confirmation of her arrival. That Philby facilitated her transit is shown by what he told Borovik:

When the war started. I knew she would be better off in England. If the Germans took Paris, she would not survive. At that time any movement between France and England – except for military movements – could be made only with permission from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I wrote a letter requesting permission for her to return to England. Legally she was still my wife, and they had no reason to refuse. The ministry gave its approval, and she moved back to London.

I find this a remarkable statement, for several reasons:

- December 1939 was a very early time to be making and executing emergency flight plans. The Germans were nowhere near to ‘taking Paris’. The haste is noteworthy.

- The NKVD would have made their own arrangements for exfiltrating their assets. Kitty Harris (Donald Maclean’s courier and former lover) was moved, with a false passport in the disguise of a wife of an Embassy official, to the Soviet Union as the Germans approached in May 1940. (Obviously, Philby would not have acknowledged that parallel.)

- The NKVD would have directed Litzi’s next move. It shows how highly they regarded her that, despite her irresponsibly prodigal lifestyle using NKVD funds in Paris, she was approved for a new assignment in the United Kingdom (instead of being sent ‘home’ to Moscow in disgrace), and they saw no risk in this decision. (Litzy had been making regular visits back to England in the preceding couple of years.)

- The installation of a well-regarded agent in London occurred at exactly the time that the rezidentura in London was being closed down, and Gorsky recalled to Moscow for the best part of a year.

- Philby must surely have met Litzi during this period, to make the arrangements. This assumption is confirmed by the fact that Gorshakov in the Paris residency reported that Philby provided valuable information in the period September – December 1939.

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs saw nothing unusual or suspicious in allowing a known Communist to regain entry to the United Kingdom, at a time when the Nazi-Soviet pact was in effect, and it reacted extremely promptly to Philby’s request.

- Philby’s implication is that, if he had been divorced from Litzi by this time, she would not have been allowed in the country. This represents a significant argument as to why they had indeed remained married for so long.

- Many years later, Litzi told her daughter that, after the outbreak of the war, she and Kim had returned to London, and that she had been able to terminate her relationship with the Soviet secret service. That was a double lie: Kim was still in France when she arrived, and individuals were not able to break away from the NKVD at their own whim.

Yet there are two further twists to this very odd tale. The first can be found in the Appendix to Helenus Milmo’s report (see above) where he writes as follows:

What I regard as particularly important and significant in this connection is a letter which PHILBY wrote to the Passport Office on 26th September 1939 in order to enable Lizzie to obtain the requisite facilities to get to France. If PHILBY’s story is to be accepted, at that time he did not know what his one-time Communist wife had been doing with herself in the course of the previous 2½ years.

What is going on here? Litzi was apparently already in France at this time, and Kim was not appointed BEF correspondent of the Times until October 9. Why, if travel restrictions had been imposed, would Philby so clumsily attract attention to his wife’s ambitions on the Continent? Milmo goes on to write: ‘The letter which he wrote contains a number of falsehoods and of course could only have been written because PHILBY was still Lizzie’s husband in name.” Apart from noting the fact that Milmo’s evidence would tend to support the fact that a file on Philby had been maintained at the time, I shall suspend judgment on this bizarre artefact until next month.

The second twist appears in a report submitted by MI5’s E5 (Alien Control: German and Austrians) to F2B (Subversive Activities: Comintern Activities and Communist Refugees) on September 13, 1945, which describes members of Edith Tudor-Hart’s circle. Here a reference to a ‘LIZZY FEABRE or FEAVRE née Kallman’ is made. It states that this woman was born in Vienna, which she left in 1934, and that later ‘she went to France, where she lived for three years and married an Englishman there thus acquiring British nationality’. The note then introduces her relationship with Georg Honigmann. (It is perhaps ironic that, the very same day that this report was written, Guy Liddell was meeting with John Marriott and Kim Philby to discuss what should be done with Nunn May after the Gouzenko revelations.)