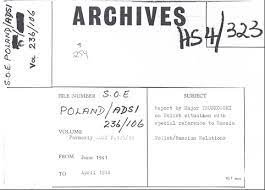

My objective in the postings for this month and the next is to determine how and why the Chiefs of Staff, in the first half of 1943, allowed SOE to engage in a maverick operation in France that had a disastrous outcome for its networks, as well as causing a breach of trust with French Resistance forces.

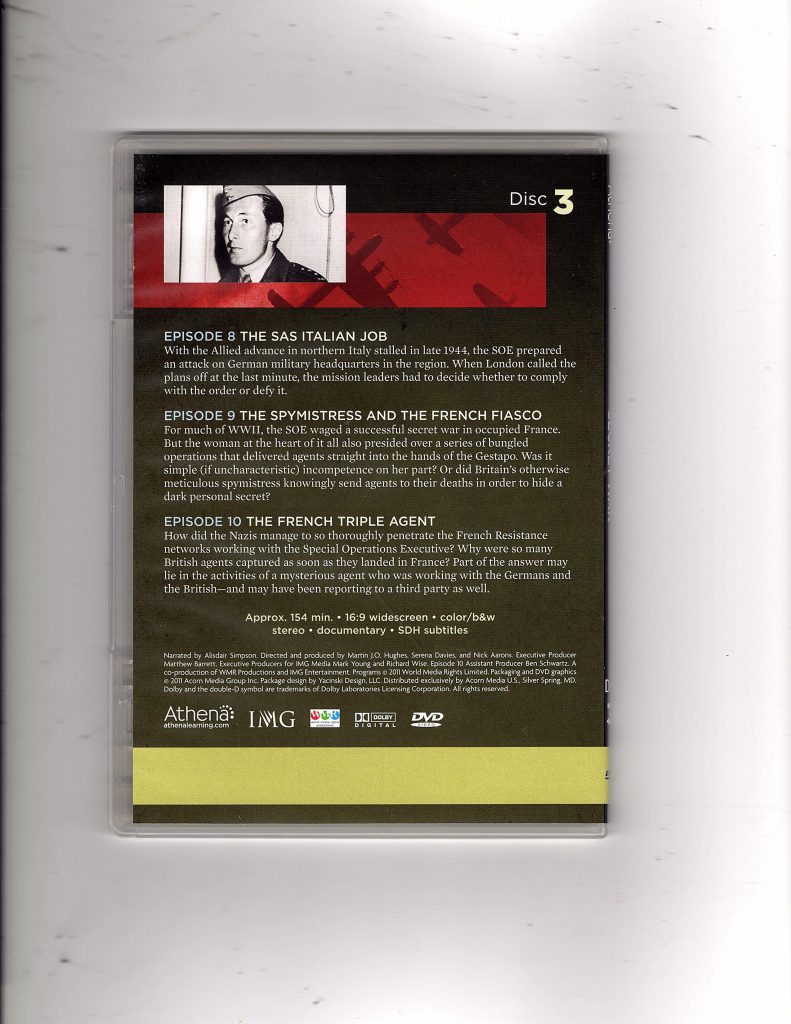

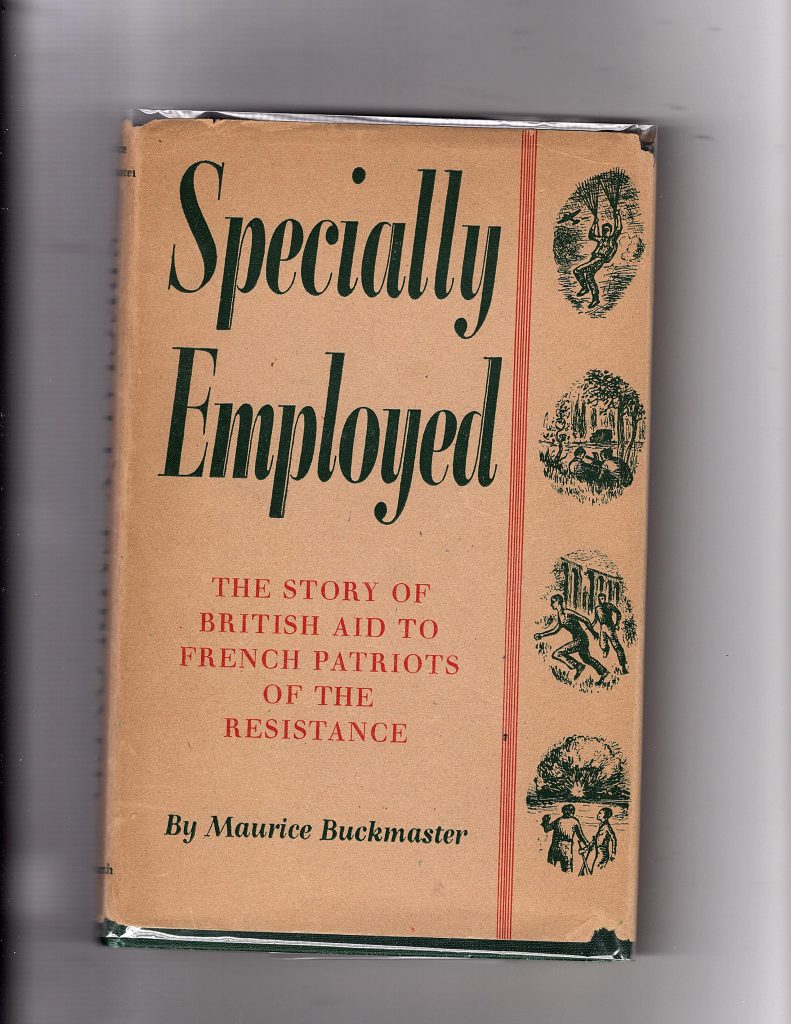

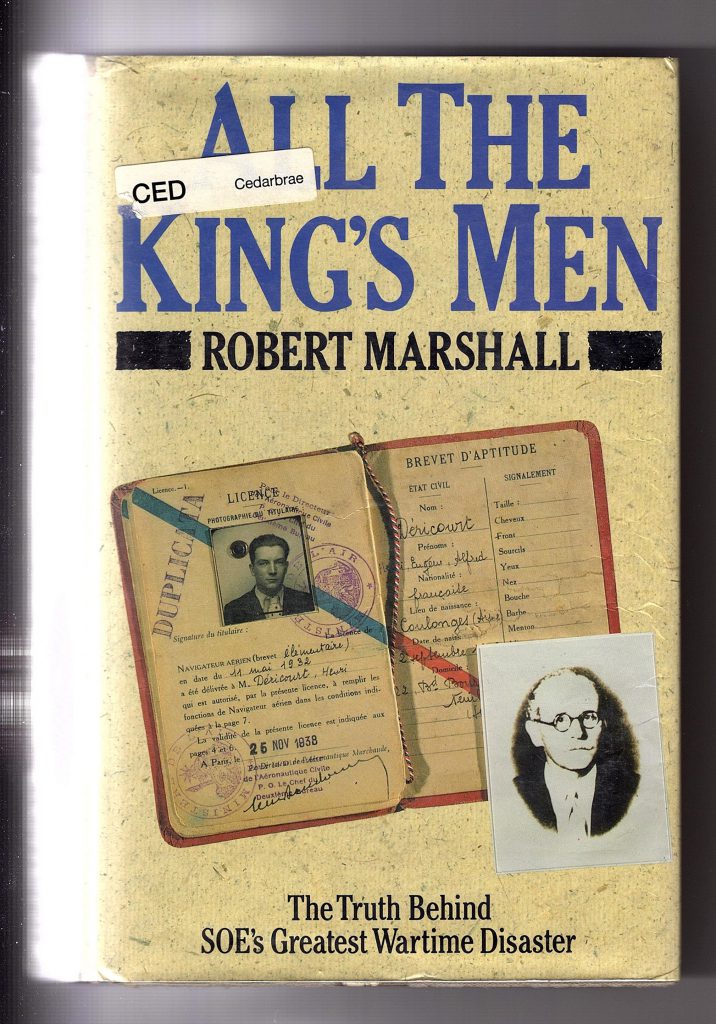

It is inarguable that a large supply of arms was dropped to the French Resistance in the first half of 1943, that the Resistance believed an Allied assault on the NW French coast was imminent when in fact none was planned, that the Sicherheitsdienst and the Abwehr discovered and took possession of most of the arms caches, that dozens of SOE agents and French citizens lost their lives in the process, and that the actions of Henri Déricourt, who was working for both British and German intelligence, contributed to the disaster.

But what has not been established is why an operation of this scale was never officially named, described, or approved by the Chiefs of Staff, or who authorized an exercise that contravened SOE/Chiefs of Staff directives on arming patriot forces as well as the priorities of then-current military objectives, or why Bomber Command agreed to provide the aircraft to enable the arms drops to occur, or why the operation was not aborted when clear signals of security breaches appeared.

In this first report I analyze events up to the debatably successful execution of the OVERFLOW deception operation at the end of 1942.

But first a review of the Allied Operations for Western Europe that were considered, and sometimes executed, between 1942 and 1944. Imagine yourself a member of the Chiefs of Staff, with your epaulettes clearly visible, surrounded by aides and scribes, trying to remember and distinguish all of the projects that come up in the discussion, and hoping that you do not get any of the code names mixed up when your turn to speak arrives.

Primary Operations & Code Names (in approximate chronological order):

GYMNAST (November 1941 plan for amphibious landing in French North-west Africa)

HARDBOILED (an early 1942 notional attack on the Norwegian coast)

ROUNDUP (Eisenhower’s early 1942 plan for a Spring 1943 invasion of northern France)

TRIDENT (Roosevelt-Churchill conference in Washington, May-June 1942)

IMPERATOR (plan for a raid on, and withdrawal from, a French port in summer 1942)

RUTTER (Dieppe raid preparation, summer 1942)

JUBILEE (final Dieppe raid, August 1942)

JUPITER (1) (Churchill’s plan for assault on Norway & Finland, as alternative to OVERLORD, strongly opposed by Chiefs of Staff)

SLEDGEHAMMER (April 1942 plan for limited cross-Channel invasion in 1942/3)

TORCH (final name for invasion of French North Africa in November 1942)

– OVERTHROW (deception plan for assault on Calais/Boulogne in October 1942)

– CAVENDISH (unrealised plan for diversion for TORCH)

– SOLO (deception plan for assault in Norway as diversion for TORCH)

– KENNECOTT (a plan to allay Vichy suspicions over the TORCH convoys)

– TOWNSMAN (plan to conceal real role of Gibraltar in TORCH)

– QUICKFIRE (plan to suggest US TORCH forces were going to the Middle East)

HADRIAN (capture and retention of Cotentin peninsula)

LETHAL (capture of Channel Islands)

BRIMSTONE (operation to take Sardinia, proposed in January 1943)

SYMBOL (Casablanca Conference in January 1943)

COCKADE (June 1943 deception plan to keep German forces in the West)

– TINDALL (plan for sham landing in Norway)

– STARKEY (plan for sham amphibious invasion in Boulogne)

– WADHAM (plan for sham landing in Brest)

HUSKY (plan to invade Sicily in July 1943)

– BARCLAY (deception plan)

– MINCEMEAT (deception plan involving corpse)

ANVIL (preliminary plan for invading Southern France in 1943)

POINTBLANK (bomber operation to cripple German air fighter production)

BOLERO (military troop build-up in UK)

– LARKHALL (build-up of US troops)

– DUNDAS (build-up of UK troops)

– SICKLE (build-up of airpower to support BOLERO)

JAEL (London Controlling Section’s deception plan of August 1943)

CONSTELLATION (operation against Channel Islands in 1943)

HIGHBALL (bouncing bombs)

– UPKEEP (naval version of HIGHBALL)

OVERLORD (plan for assault on Northern France in 1944)

– BODYGUARD (deception plan to cover OVERLORD)

– ZEPPELIN (deception plan to tie down Germans in Balkans and France)

– FORTITUDE (deception plan to mislead Nazis about time and place of assault)

– NEPTUNE (naval component of OVERLORD)

JUPITER (2) (July 1944 offensive in Normandy)

CROSSBOW (project to counter the V-bombs)

CASCADE (deception plan for Mediterranean theatre: replaced by WANTAGE in February 1944)

DRAGOON (landing in Southern France in August 1944, replacing ANVIL)

This is only a partial list, and of course covers only a section of the European theatre of war, while the Chiefs of Staff had to consider world-wide operations. Is it not surprising that feints and realities were sometimes confused?

Contents:

- Stalin and the Second Front

- MI5 & MI6 in Double-Cross

- The XX Committee and MI6

- The Twist Committee

- OVERTHROW and Rear-Admiral Godfrey

- SOE, the Chiefs of Staff, and Churchill

- War Cabinet Meetings: June-December 1942

- Conclusions

1. Stalin and the Second Front:

‘Chutzpah’ (a word from which, according to some imaginative etymologists, the term ‘hotspur’ is derived) could have been devised as the most appropriate noun to describe the initial Soviet representations to Britain after the Nazi invasion of Russia in June 1941. Five days after Operation Barbarossa, on June 27, Soviet Ambassador Ivan Maisky approached Lord Beaverbrook, Minister of Supply, and asked him to raise the question of the Second Front with the War Cabinet. When Major Macfarlane arrived in Moscow on June 28, as the leader of the military mission to Moscow, Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov immediately ‘demanded’ of him that the British open a Second Front.

For almost two years, the Soviet Union had been in a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany. It had supplied Hitler with raw materials, minerals and grain which enabled Germany to wage war more effectively against Great Britain, which, after the fall of western Europe, was fighting alone with its dominions and remnants of exile armies. (The United States would not enter the war until December of 1941.) The Soviet Union had brutally invaded and occupied the Baltic States, and moved its army into Finland, exactly the types of aggression over which Britain had gone to war. The notion that the onus now fell on the embattled United Kingdom to relieve pressure on the Soviet Union, where Stalin had disparaged all intelligence reports about a forthcoming invasion, was expressed without irony by Stalin himself, by his humourless sidekick Molotov, and by his scheming and insidious ambassador in London, Maisky. It was a typical shameless ploy by Stalin to make demands and then test the resolve of his new allies to see how far they would go to challenge him.

Moreover, Stalin appeared to overlook the fact that Britain was already engaged in a bitter battle with Germany on other international fronts, primarily in the Mediterranean and North Africa. Stalin may have deprecated such operations as ‘imperialist’, as indeed they were in a sense, since they were activated as a measure to protect oil supply-lines from the Middle East, and were masterminded largely from Cairo, in Egypt. (Of course, quite unlike the Soviet Union’s imperialist annexation of the Baltic States.) Yet the presence of troops in North Africa necessarily drew in large armies of Italian and German forces: indeed, Barbarossa itself was (fatefully) delayed a few weeks because Hitler had to divert army divisions to suppress anti-Nazi revolts in the Balkans before turning his attention to the Soviet Union. ‘Second Front’ was thus a misnomer that Stalin was able to use for vital effect in his propaganda objectives. Yet it was also hypocritical: when the Germans invaded, Stalin expressed disbelief that they would wage war on a ‘second front’, thus implicitly conceding that a ‘first front’ with Britain already existed.

The last aspect was the absurdity of Britain’s attempting to stage an assault on the French coast as early as 1941. Only a year before, Hitler had abandoned his effort to subdue the United Kingdom because he knew that he could not attempt a naval landing until he had secured the skies, and destroyed the Royal Air Force. It would have been impossible for the British alone to raise an assault force that could have landed on French soil without being pushed back swiftly into the sea, with disastrous consequences for morale, and eroding future chances of success. Great Britain would have been able to muster only about six divisions, against Germany’s twenty to thirty. In addition, Churchill had immediately promised Stalin all manner of material support (tanks, ammunition, metals) which inevitably degraded the country’s ability to wage war around the world.

Yet, while staging an assault in 1941 would have been suicidal, the re-entry into Northern France (Eisenhower resisted calling it an ‘invasion’ as that term would suggest a hostile attack on alien territory) could probably have been undertaken before the eventual date of June 1944. For example, in 1980 Walter Scott Dunn Jr. published Second Front Now, subtitled An Opportunity Delayed, which made the claim that, had the Allied command seized the challenge of diverting landing-craft to the operation, an assault could have been made in 1943, when the German forces were actually weaker than they were in 1944. It consisted of a careful and in some ways an appealing thesis, but did not pay enough credit to the fact of the Allies’ unavoidably split command, or to the pluralist method of making decisions.

Sir Alan Brooke, as Commander of the Imperial General Staff, masterminded the overall strategy, which had as its objective a Mediterranean assault first, taking Italy out of the war, diverting German troops from Russia in so doing, before then making re-entry into France. Yet he was challenged on all sides: by Churchill, who made impulsive decisions, interfered continually, and was forever mindful of the personal commitment he had made to Stalin; by Portal and Harris of the RAF, who believed the war would be won by saturation bombing; by the somnolent and ineffective Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound (who died in 1943); by Director of Naval Intelligence Admiral John Godfrey, who questioned his estimates of the strength of German forces, was a continual irritant on the Joint Intelligence Committee, and had to be eased out by its Chairman Cavendish-Bentinck in the summer of 1942; by the Americans generally, and specifically General George Marshall, who continually pressed for a cross Channel operation first, or else became diverted by needs in the Asian theatre; and, last but not least, by the ‘Second Front Now’ campaign organised by the press baron and sometimes Cabinet Minister, the boorish and dangerous Lord Beaverbrook. It all drove Brooke to distraction. One should not overlook the fact, however, that watching the two totalitarian powers attempt to destroy each other brought temporary comfort to the British military staff. What they overlooked was that, if one of the two foes eventually conquered the other, the victor would come back with a vengeance.

What is certain is that the Chiefs of Staff lost the propaganda war. By not countering Soviet demands resolutely enough when they were first made, the notion of the ‘gallant Soviet people’ fighting the Hun almost alone, with casualties in the millions while Britain was not resolute enough to sacrifice such armies, was promoted by the Communist Party, and by its agents of influence in government. (The Soviets lost over 3 million men between July and December 1941.) Of course, the British did not have such numbers to spare, and, if it had incurred large losses in such vain exploits, Churchill would have been thrown out of office. All this serves to explain why the tactics for taking on the Germans in Europe during 1942 and 1943 stuttered and stumbled so painfully.

Ironically, more recent research (Pechanov & Reynolds, echoed by O’Keeffe and Dimbleby) indicates that as early as the end of 1941, when the Germans were forced to retreat from Moscow, Stalin had re-assessed the resolve of his Soviet troops, and had also come to understand the impracticalities of a hasty mainland offensive by GB/USA forces in western Europe. He and Molotov then decided to play the ‘Second Front’ card in order to assume the moral high ground, and obtain concessions elsewhere. In seeking an early assault by his allies, however, it should not be overlooked that Stalin’s intentions may not have been entirely honourable. Moreover, he had the advantage over Churchill. He was receiving reports from his spies in London: Kim Philby notoriously passed on to Moscow the news that his boss, Valentine Vivian, knew that officers briefed on TORCH immediately got in touch with their Communist contacts. Irrespective of these essential facets of political intrigue, the timing and location of the re-entry into France would obsess the Chiefs of Staff over the next couple of years.

2. MI5 & MI6 in Double-Cross:

The Chiefs of Staff recognised that careful deception plans would be a necessary part of the eventual operation to make a successful assault into France. They had the experience of “A” Force in the Middle East as a model to be copied. Yet the mechanisms to deliver such capabilities took time to mature. At the urging of Dudley Clarke, who ran “A” Force, an embryonic London Controlling Section (LCS) had been set up under Oliver Stanley in October 1941 to replace the rather passive Inter-Services Security Board, but Stanley struggled with recruiting staff, and gaining the respect of the forces. This was partly due to the fact that he was Controller only part-time: he was also managing a group known as the Future Operational Planning Section (F.O.P.S.). In fact, while the departmental history at CAB 154/100 refers to the unit as the LCS from this time, it was not formally given that title until Bevan’s appointment in May 1942. In any case, Stanley neglected to build the requisite strong relationships with other government bodies, the Services, and the intelligence organizations.

The Double-Cross (XX) Committee had been established in November 1940, but it still had a very defensive focus as late as August 1942, when it cautiously came to the realisation that there were no Abwehr spies operating from the mainland of the United Kingdom of which it was unaware. And then, in the summer of 1942, factors conjoined to make serious deception planning a reality. John Bevan replaced Stanley as head of the LCS; General Wavell impressed upon the Chiefs of Staff the value of deception; the Chiefs of Staff finally had some concrete operational plans for assault that of course had to be in place for any deception game to play against. Critically, Churchill reinforced to his Chiefs of Staff the importance of robust deception plans.

It would seem that the XX Committee was at that time perfectly poised to assume a greater role in military deception plans through the use of its ‘double agents’. The matter of using DAs to ‘direct the attention of the Germans to a phoney major operation’ in France had been discussed at the W Board meeting in May 1942. Yet that did not happen. What went wrong? Was there something implicitly awry in the XX set-up?

Unfortunately, the authorized history of Strategic Deception [Volume 5 of British Intelligence in the Second World War], by Michael Howard, while representing an eloquent exposition of the main threads, is an inadequate guide to the politics and controversies. The main deficiencies of his analysis centre on his oblique coverage of the roles of SOE and MI6, and of Howard’s studious refusal even to mention the obscure units set up by Bevan, namely the OLIVER, TORY, TWIST and RACKET committees, which were established as a response to what some saw as the XX Committee’s weaknesses. (Thaddeus Holt’s The Deceivers is slightly more useful in this regard.) For the role of MI6 and SOE in handling ‘double agents’ – or as Bevan preferred to call them ‘special agents’, or ‘controlled enemy agents’ – was paradoxical and problematic. (I shall, for reasons of economy and precision – except when citing other authors and documents – hereon refer to such persons as ‘DA’s, since that abbreviation, though regrettably inaccurate, is the one used in contemporary documents.)

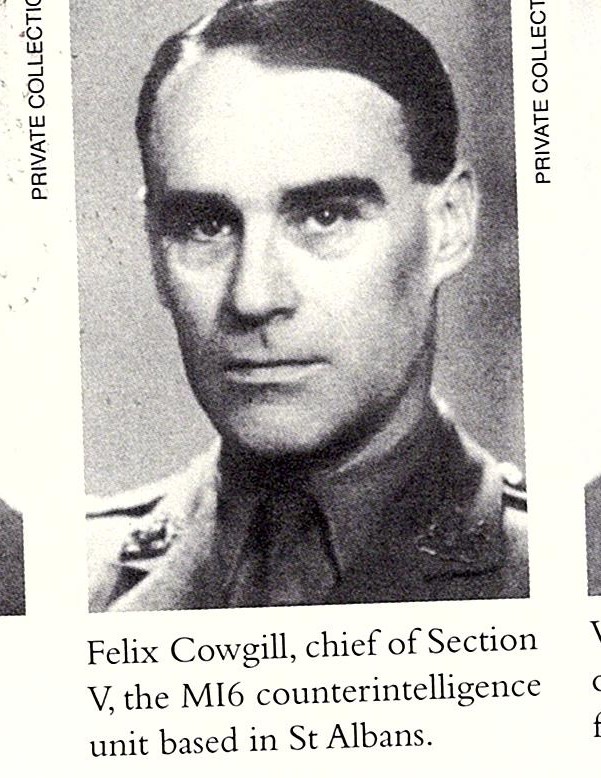

In essence, the controversy lay in territorial management. MI5 was responsible for counter-espionage on imperial soil: MI6 in foreign countries. The first challenge that this division generated was the fact that agents naturally operated across such boundaries, and thus competition between the two services for ‘ownership’ arose. If a prospective DA emerged in, say, Spain, but were to travel to the United Kingdom, who would manage him or her? And who surveil him or her when he or she had to travel back to the Continent to meet his or her handler? This conflict caused a lot of friction, especially when Major Cowgill of MI6 behaved very protectively about ULTRA transcripts (produced by The Government Code and Cypher School, or GC&CS, commonly known as Bletchley Park, which reported to MI6) that relayed vital information about the meetings between the Abwehr and the agents, and Cowgill withheld such information from his MI5 counterparts.

A more important factor, however, was the issue of operational control and security. If agents used exclusively by MI6 for deception purposes resided on foreign territory, or in countries overrun by the Nazis, how did MI6 officers know that the DAs were working loyally for them, and that they would not betray the confidential relationship to their Abwehr handlers as soon as they were out of sight? Since the XX Committee could not control their wireless messages or invisible ink letters (as MI5’s B1A unit did with domestic controlled agents), an enormous exposure existed with MI6 agents. This was highlighted, for example, by MI6’s attempt to ‘turn’ German POWs and parachute them behind enemy lines in 1944. In April, Hermann Reschke (a POW) immediately denounced his colleague Frank Chamier to the railway staff at the local station south-west of Stuttgart, as Stephen Tyas reports in his book SS-Major Horst Kopkow. Only if intercepted and deciphered wireless traffic showed that the deception was successful could an exercise be considered safe: that in turn required that the Abwehr station communicate with Berlin via wireless, not telephone, and there was still a chance that a counterbluff was being used.

Yet, while all the chroniclers refer to the fact that MI6 (and sometimes SOE) managed DAs, they hardly ever identify them – except when their cases are also managed by MI5 (such as GARBO and TRICYCLE), or they are of a very dubious quality (such as ARTIST, the Abwehr officer Jebsen). Keith Jeffery, the authorized historian of MI6, leads the way. He makes the conventional bland assertion: “As regards double agents, broadly speaking those run in the United Kingdom and from British military bases abroad were an MI5 responsibility, while those operating in foreign countries came from SIS” (p 491). He adds another vague statement on page 569: “While the running of double agents was in practice a joint SIS-MI5 responsibility (through the XX Committee), MI5 took primary charge of those operating in the United Kingdom, and SIS of those in foreign countries.” Again, the message is clear: MI6 managed its own DAs. XX Committee authority was weakened.

And how many of those SIS agents were there? Jeffery adds: “During 1944, for example, some 113 double agents were operating under Section V’s control” – an astonishing claim, not just numerically, but in the shocking assertion that MI6’s Section V, not the XX Committee, managed them. Admittedly, twenty-seven of those were GARBO’s notional (i.e. non-existent) sub-agents, but surely the remainder deserved some coverage? Yet Jeffery restricts himself to mentioning only ARTIST (Jebsen, a dubious case, as noted above), ECCLESIASTIC (an unidentified woman in Lisbon who had an Abwehr officer as a lover), and OUTCAST, in Stockholm, who was not really a ‘double’ at all, as he had had recruited before the war, and then penetrated the Abwehr. Earlier Jeffery had mentioned the Frenchman BLA, over whom Menzies had in May 1942 personally interfered, trying to have him run through the XX Committee, but BLA turned out to be a traitor, and was shot. Why the coyness, Professor?

Michael Howard is of even less use. He writes: “That [‘running the double agents’] was the work of MI5’s section B1A, and in certain cases overseas MI6” (p 8); “For both MI5 and MI6 their [‘the double agents’] principal value lay in the information they provided about enemy intelligence services and enemy intentions” (p 9). On page 19, Howard reports that Sir Findlater Stewart was brought in ‘to investigate the possibility of a closer co-ordination between MI5, MI6 and the Special Operations Executive [sic!] as it affects the work of the Twenty Committee’. This turned out to be embarrassing, and the head of SOE ‘agreed to forget all he heard’. Howard does not explain why SOE had a role in running ‘double agents’ at this time, or how their activities were directed and managed. It is a shocking oversight. On the other hand, on page 29, he quotes John Masterman’s justifiable claim that ‘the Security Service alone is in a position to run XX agents’, but does not explore the paradox he has revealed to his readers.

Thaddeus Holt is similarly vague. He does, indeed, cite one important document. When Oliver Stanley was appointed the first Controller of Deception, MI5 offered a carefully worded memorandum, accurately summarized by Holt as follows: “ . . . while it had always been contemplated that the double agents would be used for deception, that should not jeopardize their fundamental counterespionage role, and [MI5] emphasized further that MI5 and MI6 [sic], not some deception officer, should be the sole judges of how they should be used.” (p 152) Otherwise, Holt’s coverage is scanty. He makes reference to another dubious MI6 DA, an Armenian businessman in Istanbul code-named INFAMOUS, and dedicates one brief clause to COBWEB and BEETLE, Norwegian DAs run by MI6 in Iceland.

John Masterman, who reputedly wrote ‘the book’ on Double-Cross operations, The Double Cross System, hints at MI6’s role, but with scarce recognition of any of their DAs, drawing attention instead to the illogical but unavoidable rule of responsibilities split by geography. Yet he cryptically introduces MI6’s involvement: “At every meeting [of the XX Committee] an account of the activities of the agents was given by the M.I.5 and M.I.6 representatives, so that all members of the Committee were apprised of what was going on in connection with the cases”. (As the Minutes will show, this is a travesty of what actually happened.) Despite his opinion quoted above, Masterman then blandly echoes the policy of the W Board (from October 1941): “The Security Service and M.I.6 remain normally the best judges as to how the machine under their control can be put into motion to the best advantage” (p 104). Some machine; some control. And Masterman, reflecting happily as to how the unnamed Cowgill’s intransigence was eventually overcome, concludes: “In particular the services, whatever their views may have been as to the share in control which belonged to the W. Board or to the Security Service, never questioned or adversely criticized the practical control and the running of the agents by M.I.5 or M.I.6.’ [Note: ‘M.I.5 or – not “and” – M.I.6.’, and omitting the fact that the XX Committee was supposed to be in charge.] Yet the only MI6 agent Masterman names is SWEETIE, an ‘MI6 double-cross agent in Lisbon’, who has otherwise been lost to history.

Another doyen of the popular set of writers on intelligence matters, Nigel West, is also vague. In his 1983 account of the agency, MI6, West asserts that the XX Committee ‘co-ordinated the activities of all the double agents based in the United Kingdom’ [my italics]. West thus by default avoids any suggestion that MI6 was supervised by the XX Committee in handling DAs on the European continent, and completely ignores the activities of MI6 DAs wherever they were supervised. West then moves smoothly on to the Thirty Committee, which managed such entities in the Middle East.

Lastly, we have the breezy work of Ben Macintyre, in Double Cross. He focusses entirely on MI5’s and B1A’s handling of the agents, frequently highlighting the rivalries between MI5 and MI6, while ignoring completely any agents whom MI6 may have been handling. He raises his readers’ interest, perhaps, when he writes of the deception projects behind FORTITUDE: “The French Resistance, Special Operations Executive agents, saboteurs and guerrilla teams, MI6, the code breakers at Bletchley, secret scientists, and camouflage engineers would each play a part on this great sprawling, multifaceted deception campaign” (p 176). Yet the precise nature of those parts is beyond his scope or understanding. No exclusively MI6 DAs appear in his Index.

So what was the exact mission of the XX Committee, and why the evasiveness over the MI6 and the SOE contribution? Why is so little written about MI6’s DAs? To try to resolve this conundrum, and understand why the TWIST committee was set up, an inspection of the XX Committee’s minutes is necessary.

3. The XX Committee & MI6:

The minutes of the XX Committee reinforce the message that its chairman, John Masterman, unwittingly left for posterity in his book: he was confused as to whether MI5 and MI6 jointly ran DAs who crossed their territories, or whether the Committee was overall responsible for DAs who were separately managed by each of the two services. This might appear a trivial point, and it was not entirely his fault, but I believe it is very important. Within MI5, there were mechanisms, and a section, B1A, which took the recruiting and control of DAs very seriously. There appeared to be no equivalent section within MI6: at least no records have been made available. Masterman probably did not believe that he had the clout to challenge the authority of the very difficult Felix Cowgill, who was the dominant MI6 representative during the first eighteen months of the XX Committee’s existence. Thus the joint oversight by the XX Committee did not occur properly.

In contrast, Michael Howard (p 8) makes the point that the task of the XX Committee was not to ‘run’ the double agents, adding: “That . . . was the work of MI5’s section B1A, and in certain cases overseas MI6”. By stating this, however, he opens up the question of the existence of equivalent processes in MI6. He describes the role of the Committee as a routine administrative one, for eliciting, collating, and obtaining approval for ‘traffic’ to be passed by the DAs, and to act as a point of contact between other institutions. Moreover, Howard draws attention to the anomalous reporting structure: the XX Committee’s chairman, John Masterman, was responsible to the Director-General of MI5, but at the time of its establishment, David Petrie had not been appointed. The Committee itself was a sub-committee of the W Board, but that turned out to be a less than satisfactory entity. As Christopher Andrew writes (p 255): “This elevated committee, while considering broad policy issues, inevitably lacked the time to provide the detailed, sometimes daily, operational guidelines which became necessary following the expansion of the Double-Cross System in the autumn and winter of 1940.” The XX Committee thus lay in some sort of limbo.

The ambivalence is shown in the initial memorandum that Masterman wrote, back in December 1940, appealing for the creation of this new committee to handle the management of DAs, including the greater release of information from the service departments: “Since the recognition in July, 1939, by the Directors of Intelligence of the importance of the ‘double agent’ system, M.I.5 and M.I.6 have, both independently and conjointly, built up a fairly extended ‘double agent’ system under their control”. Perhaps in recognition of the challenge of dealing with MI6, part of Masterman’s recommendation was that the committee should report to the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC). A hand-written note states, however, that the Director of Naval Intelligence, John Godfrey, ‘informed us that he would not allow the Committee to be attached to the J.I.C. and that it must be attached either to the W Committee or to the Directors of Intelligence.’ This was a typical outspoken objection by Rear-Admiral Godfrey, and would be a harbinger of later controversies. Yet it suggests a serious intent. One might wonder what the fine distinction between ‘attachment to the J.I.C’ and ‘attachment to the Directors of Intelligence’ represented, but Godfrey was very aware of the secrecy attached to the W Board, and no doubt believed that its activities would inevitably be slowed down – or even suspended – if the news on what it was doing spread too far. In this assessment Godfrey surely overlooked the fact that the XX Committee was already in contact with such bodies as the Service Departments.

The relationship with the W Board could be the subject of a completely fresh study. The W Board was an informal body, its members being the three directors of service intelligence (initially Godfrey, Davidson and Boyle), Liddell from MI5, Menzies from MI6, and Findlater Stewart as representative of the Civilian Ministries. In its postwar history (at KV 4/70), its mission was defined as ‘the general control over all deception from the U.K. to the enemy’ but its author claimed that, with the appointment of the Controlling Officer (implicitly Bevan, not Stanley, whose tenure it overall ignored), the Board ‘still maintained general control of all work of this nature through double agents’. Sadly, this assertion was not true in more than one aspect. It delegated work to the XX Committee, but failed to give it a proper charter or guidelines.

That MI6 was handling DAs ‘independently’ is soon apparent, since the records show that the constitutionally reclusive Cowgill, for most of the time the only MI6 representative on the Committee, was required to submit orally his reports on agent activity. It is not possible to determine whether the sketchy information recorded in the minutes about MI6’s DAs is due to secretarial discretion, or because Cowgill was simply reticent, but a few of his submissions can be noted. He introduces the IRONMONGER case on February 13, 1941, but two weeks later states that ‘the Germans are reported to have executed IRONMONGERY [sic]’. On March 13, POGO and his family are reported to have been arrested by the Spanish Police. A plan STIFF, involving RSS (the Radio Security Service), and a drop of a wireless set, is aired. Cowgill has a contact for Plans ATKINS & L.P.. On May 22, Cowgill refers to a Plan PEPPER involving WALDHEIM in Madrid. On June 5, Cowgill has to present his method of grading sources, perhaps suggesting some scepticism on the part of the other members of the Committee, but nothing more is said.

Yet the catalogue continues. On July 3, Cowgill is recorded as giving ‘an account of a “triple-cross” which he had called VIPER, which had been attempted in Lisbon, and which he is taking up’. The next week, he reports on PASTURES (in Lisbon) and YODELER (not further described). THISBE appears in August, and MINARET and CATKIN (active in the USA) soon after, followed by TRISTRAM. On September 18, YODELER is reported to be ‘disorganized’, but the following week, three new DAs are introduced: SCRUFFY, BASKET and O’REEVE.

It is not necessary to list all of Cowgill’s contributions: the implications are clear. MI6’s handling of DAs was a mess: it had no methodology for recruiting DAs, or detecting their true allegiance, yet no one on the Committee appeared keen to press Cowgill (or his boss, Menzies) too hard. And this situation would continue until Masterman and his allies became utterly frustrated with Cowgill’s refusal to disclose traffic from ULTRA (Most Secret Sources) that would allow those managing the messages of deception in B1A to verify that their bluffs were being accepted by the Abwehr. It all came to a head in April 1942. Findlater Stewart was invited in. Masterman wrote a careful letter to Menzies, and Menzies replied positively, thus forcing Cowgill’s caution to be curbed, with Frank Foley of MI6 also brought on to the Committee to help smooth things over. Yet Foley continued the practice, introducing new DAs without any clear background information, such as FATIMA (a male in France), SEALING WAX, SPOONER and PRIMULA.

Far too late in the day, probably by virtue of external prodding, MI6 was asked to account for itself. The minutes of the meeting on September 3, 1942, show that John Masterman, the Chairman, stated to the attendees that ‘the list of M.I.6. agents had been circulated’. Yet it was a mixed bag. Masterman then said that the list ‘included some straight double-cross cases and some where the enemy were operating captured agents’ sets, and it was felt that these latter might be brought into play in the near future.’ This is an extraordinary admission, suggesting that MI6 (and maybe SOE) was aware that the Germans had captured some of their agents, but, instead of closing down the relevant networks (when they must have been unaware of the expanse of the damage), they were keen to exploit the situation for deception purposes. The disclosure of this policy has profound implications for the study of the PROSPER network.

This is quite a remarkable state of affairs. The B1A DAs within MI5 are very well documented, with their own KV folders in the archive, and Masterman’s mostly straightforward account of how the whole scheme was managed. We can understand the cautious way that the officers had to approach their agents, to manage their communications and monitor their loyalty, and to seek out information to be passed on that could deceive the enemy without giving away sensitive secrets. Yet about the MI6 DAs (if they really were such) we know hardly anything, and even the authorized historian has skated over the topic apparently without realising that all those codenames had surfaced in the XX Committee minutes. Why have all these names been left off the official lists? Because they were not DAs at all? Because they were an embarrassment, an exposure, a security risk? It seems that senior MI6 officers were keen to escape the nosiness of the XX Committee, and that is why they sought out an alternative mechanism.

4. The TWIST Committee:

On May 21, 1942, the Chiefs of Staff approved Lt.-Col. John Bevan’s appointment as head of the London Controlling Section, replacing Oliver Stanley, with the announcement being made several weeks later, in August. Almost immediately, Bevan started negotiations with the Directors of Intelligence. On July 13, Guy Liddell reported in his Diary that the Director of Military Intelligence, Major-General Francis Davidson, wanted Bevan brought on to the W Board. On August 25, Liddell noted that the Director of Naval Intelligence, Rear-Admiral John Godfrey, believed that Bevan should be Chairman of the XX Committee: Liddell pointed out to him that Bevan was already a member of that body. (His first attendance was at the eighty-second meeting, on July 30: he had been briefed on the details of the Double-Agent scheme, a privilege not granted to his predecessor.) And then, on September 7, at the eighty-seventh meeting, Bevan made a startling announcement.

The Minutes start inauspiciously, with a note that ‘the list of M.I.6 agents was not yet available’, hinting at a fresh Committee desire for greater disclosure from MI6. Soon afterwards the following brisk statement appears:

Colonel Bevan reported that the Chiefs of Staff had directed that he should undertake a large scale deception during the autumn and for this purpose he had formed a small sub-committee, with DMI’s approval, for putting his plans into operation. In this connection it was agreed that Major Robertson, who was a member of the sub-committee, should read all proposed traffic before it was sent for approval, in order that it should not run counter to the major deception policy. The normal approving authorities, therefore, could be satisfied that nothing would be submitted to them which would be inadmissible from the point of view of this deception.

This is a puzzling minute. It suggests that Bevan’s deception project was a singular event, and of short duration (though ‘large-scale’), and that whatever traffic it generated would be supervised by Robertson and the traditional clearing-house, as if the W Board were in charge of ‘the major deception policy’. Bevan’s statement also refers cryptically to ‘his plans’: were they plans he himself cooked up, or had they been approved by the Chiefs of Staff? It is not clear, since Bevan refers only to the DMI’s (Davidson’s) approval. Ironically, the post-war history of the W Board (cited above) asserted that the XX Committee was able to work much more freely than the Controlling Officer (Bevan), since the latter ‘had a “charter”’, and had ‘to refer matters to the Chiefs of Staff’.

On the other hand, at a ‘witness seminar’ held in London in 1994, Professor Michael Foot (the SOE historian) presented the LCS as ‘the controlling centre for deception, which so far as I can make out was the boss among the secret services because anything that it asked to get done was done’. This latter view would appear to be reinforced in a telling anecdote from Thaddeus Holt. The American Bill Baumer recalled visiting Bevan, and recorded that the Controller made a decision and started implementing it even before the Combined Chiefs of Staff had authorized the real operation. (That sounds like the pattern that COCKADE would take.) “Baumer asked him about this and asked to whom Bevan was responsible”, writes Holt. “‘To God and history,’ said Bevan.” He clearly had an ego and a sense of entitlement. Perhaps the W Board historian did not know what was going on, but it is more likely that he indulged in some retrospective wish-fulfilment.

John Masterman, the XX Chairman, felt himself under siege. He submitted a very long memorandum to Liddell on September 5, in which he recounted the Committee’s history, stressing its role in counterespionage, while admitting that it needed greater assistance from the Services in order to boost its deception capabilities, so that it might contribute better to military deception as opposed to simply political deception. He reminded his boss of the letter which Rear-Admiral Godfrey had sent to the members of the W Board on August 22 (the letter that Liddell referred to, as described above), summarizing its message as follows:

In this he says that he has been wondering whether the activities of the Twenty Committee are under the best possible direct supervision and has come to the conclusion that the position is not satisfactory. He says that the Chairman is not in touch with the requirements of the Chiefs of Staff or the Joint Planners, and that it is impossible for him (D.N.I.) or probably for other members of the W. Board to provide the necessary day to day guidance. He therefore suggests that Colonel Bevan should be appointed Chairman of the Committee.

In light of the increasing requirements for operational (or offensive) deception, the Directors of Intelligence were presumably becoming unhappy about the devolution of authority to the XX Committee and Major Robertson of B1A (see below). Evidence of a policy clash appears. Bevan was probably under pressure from Churchill to accelerate deception efforts, and the Directors of Intelligence believed that the amateurs of the XX Committee were too far removed from the Service needs to be effective. Thus they believed that they needed to take over the XX Committee through Bevan. Yet Bevan did not want that job, and Masterman and his team resisted. Masterman added a telling, but highly confused, comment:

It is clear from this letter that D.N.I. holds the view that the XX System is run almost exclusively for purposes of operational deception, and that he regards the agents as being under the direct control of the Twenty Committee, acting on behalf of the W. Board, and not under that of M.I.5 and M.I.6. The ‘day to day guidance’ which D.N.I speaks of, and which neither he nor others members of the W. Board can provide, is in fact provided by M.I.5 alone.

Thus Masterman blew a large hole in the role of the XX Committee, and exposed the fact that MI6 supervision of DAs was, for all intents and purposes, non-existent. He also openly regretted that a note written by Petrie, the Director-General of MI5, from August 29, that reinforced the successful role of MI5, was not distributed to the W Board.

Masterman recognized that Bevan’s sub-committee threatened the functions of the XX Committee and B1A, but fought strongly against it, suggesting that whatever problem was perceived could be addressed by encouraging better liaison between the Committee and the Service representatives. Furthermore, he observed that:

I think that Colonel Bevan’s sub-committee will inevitably only be concerned with operational deception, and that the more effectively it works the more danger there is that the counter-espionage side of double agent work will fall into the background.

This was a false alarm: counter-espionage was correctly ‘falling into the background’. His allusion to ‘only . . . operational deception’ betrays the lack of importance that he grants to this function. With some political astuteness, however, Masterman creatively suggested that Godfrey’s letter should be used as a stimulus to re-energize and re-define the Committee’s charter, with the approval of the W Board and the Director-General.

One puzzling aspect of this whole debate is the absence of input from MI6. One might have expected Menzies and Cowgill to have spoken up for the XX Committee, yet no indication of their opinions is apparent. One could interpret that absence as an indication that they were quietly supportive of the Bevan agenda. Liddell, on the other hand, capitulated. As I reported last December, as early as mid-August Liddell had shown his enthusiasm for Bevan’s new scheme, and I shamelessly re-present my text here [I am not paid by the word]:

On August 15, 1942, Liddell wrote: “I saw Archie Boyle with T.A.R. [Robertson], Senter and Lionel Hale. We agreed that on matters of deception it was desirable to persuade the Controller to set up a small committee consisting of T.A.R., Lionel Hale for S.O.E., Montagu for the services and someone from S.I.S. T.A.R. will take this up with Bevan.” What I find remarkable about this observation is the fact that SOE, which was of course responsible for sabotage, appeared to be driving the intensified deception plans. Liddell does not explain in this entry why the London Controlling Section was not itself adequate for this role, or why the XX Committee was also considered inappropriate. Soon afterwards, however, he took pains to explain to Rear-Admiral Godfrey, the Director of Naval Intelligence (who wanted Bevan to chair the XX Committee) that that Committee’s prime role was viewed at that time as counter-espionage, not deception, a claim that is borne out by other evidence. In addition, I suspect that the group wanted a more private cabal away from the prying eyes of the LCS’s American partner (the Joint Security Control). The timing from this record looks far more accurate than the two claims that have appeared in print.

Thus the TWIST Committee took off. It was neither small (contrary to how Bevan presented it), nor, as it fatally turned out, restricted to a single project that autumn. I have earlier pointed out the contradictions in the accounts of its inception. The paper passed on by Anthony Blunt to the NKVD (see Triplex by Nigel West and Oleg Tsarev, p 275) stated that the TWIST Committee was ‘organised around September 1941’. That must be wrong. Blunt is unlikely to have confused the timing around the appointment of Oliver Stanley with that of John Bevan, as he (Blunt) he was on the Committee: it must be a translation error. Roger Hesketh’s claim (in Fortitude) that TWIST was initiated in 1943 must be a distortion for political purposes. Moreover, I have discovered one reference to TWIST in the minutes of the XX Committee. It appears on April 15, 1943, and runs as follows:

Colonel Robertson reported on the functions of the Twist Committee and on the arrangements being made for putting into effect the troop movements and physically carrying out the deceptive policy agreed by that Committee. This would be under the control of the Chief of Staff who had been appointed to the Supreme Command of the West. The question of putting over traffic suggested by the latter, by means of double agents, was discussed and it was agreed that all traffic, whatever the source, should continue to be submitted to the appropriate Approving Authorities before being sent.

I shall review the implications of that highly controversial statement in the context of April 1943 operations in next month’s report. It serves as an independent verification of the survival of the TWIST Committee beyond the OVERTHROW Operation. And I simply reiterate here the point I have made before: the initiation of the TWIST Committee occurred exactly at the time when MI6 and SOE were arranging the arrival of dubious characters to Britain. Len Beurton arrived in Poole on July 29; Henri Déricourt reached Gourock on September 8. And it was undoubtedly the role of Déricourt that caused the TWIST Committee to continue its activities after the initial project in the autumn of 1942 had been successfully concluded. That has all the manifestations of being a deceptive measure by Bevan against his own bosses.

The departmental history, however, is very attentive in emphasizing how proper co-ordination occurred, and how nothing slipped through. “Complete co-ordination between the LCS, the Strategic Planning Section and the JIC was maintained throughout the whole course of planning.” Yet the history reflects an imperfect understanding of the functions of MI5 and MI6, and also puts a spin on the exercise that is not borne out by the evidence. It stated that ‘MI5 was responsible for counter-espionage in the UK, MI6 for espionage abroad’ (a false contrast, and not something that Menzies would have agreed with), and continues by claiming that “co-ordination between the Section and the Secret Services was in this matter effected through the Twenty Committee, where the London Controlling Section representative was able to indicate the general Deception policy or any particular aspect of it which had to be put across to the enemy.”

It thus exaggerated its relationship with the XX Committee, and then minimized the role of the TWIST Committee, explaining that

At the same time it was very necessary that the circumstantial and important messages passed directly to the enemy Intelligence staff through the Secret Service channels should not be compromised by low-level rumours or obvious propaganda emanating from us. Close similarity would raise suspicion. To ensure co-ordination, therefore, two Committees were established by the Section within itself, known as the TWIST and later the TORY Committee at which members of M.I.5., M.I.6. and S.O.E. attended.

At least the existence of the TWIST Committee was admitted, but the retrospective description grossly distorts what in fact happened.

Two last points in this section. In my previous posts, I had overlooked the contribution that Thaddeus Holt made to the TWIST topic, in The Deceivers, and I thank Keith Ellison for bringing it to my attention. Holt concedes that multiple channels for passing disinformation were involved – but only in the context of the TWIST Committee, not the XX Committee. He writes (p 201): “. . . they met weekly or fortnightly with representatives of SOE, MI5, MI6, and other offices, to make sure the themes were consistent with – but not too obviously similar to – the circumstantial messages being passed by the double agents, and to allocate misinformation assignments among the available channels”, adding, as a way of differentiating TWIST from OLIVER, TORY and RACKET: “The Twist Committee dealt with allocation of channel assignments by way of double agents.” Yet Holt stumbles over the contrast of the TWIST Committee’s media with messages passed by DAs elsewhere.

Secondly, the membership of the two Committees needs to be noted. Of the twelve attendees at the September 3, 1942 meeting of the XX Committee, no less than five (Masterman, Bevan, Montagu, Foley and Robertson) are described in the Blunt document as being permanent members of the TWIST Committee. Masterman, notably, is described as being the TWIST Committee’s secretary, so it is clear that his loyalty was acquired by being drawn inside. (For what it is worth, Bevan had been an undergraduate at Christ Church, Oxford, the college from which the don Masterman had been hired by MI5, and he had been at Eton with Stewart Menzies.) Furthermore, MI6’s Lloyd, also a member of TWIST, occasionally sat in on the XX proceedings. Foley’s task was defined ominously as ‘the transmission of disinformation to the enemy through double agents of the Secret Intelligence Service abroad’, while Lloyd was responsible for analysing ULTRA decrypts. This overlap could be interpreted positively, indicating close collaboration between the two bodies, or negatively, since such overlap indicated a high level of redundancy and wasted effort. Yet, to me, it suggests a much more troubling outcome: how on earth did the proceedings and achievements of the TWIST Committee become reflected neither in the official histories, nor in Masterman’s own account of Double-Cross?

5. OVERTHROW and Rear-Admiral Godfrey:

So who was calling the shots? In the Directive given to Bevan by the Chiefs of Staff on June 21, 1942, Item 3 (c) carefully stated: “Watch over the execution by the Service Ministries, Commands and other organisations and departments, of approved deception plans which you have prepared.” This instruction specifically did not give Bevan the authority to establish a new unit to execute his own plans, and also required that Bevan’s deception plans be submitted for approval. Very oddly, a further instruction informed Bevan that he was ‘also to keep in close touch with the Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee, Political Warfare Executive, Special Operations Executive, S.I.S., and other Government organizations and departments’, cryptically overlooking any direct reference to MI5, the W Board or the XX Committee. Was that deliberate, or merely careless? It seems extraordinary that the Chiefs would highlight MI6 and SOE while ignoring the primary deception mechanism at their disposal.

In fact, Bevan saw a role for MI5 – but only in the promotion of domestic rumours. And that did not work out well. In a post-mortem memorandum to the War Cabinet on December 12, he wrote:

It is realized that the spreading of false rumours in the United Kingdom is not consistent with the main functions of M.I.5., and it is therefore suggested that some other body, possibly the Ministry of Information, in co-operation with the London Controlling Section, should be responsible.

That may have been correct, but to ignore the potential of MI5’s contributing with its DAs was bizarre, to say the least. Guy Liddell had discouraged it, however. The DAs controlled by the XX Committee (and B1A) did in fact contribute to the deception plans in the summer and autumn of 1942, but then for many months took a back seat in Bevan’s conception of things. Ewen Montagu, the Royal Navy representative, wrote a memorandum highly critical of Bevan, in which he described the breach that had occurred between the LCS and the XX Committee. As Thaddeus Holt reports it:

By Montagu’s account, there was ‘considerable friction’ between the Twenty Committee and the London Controlling Section after the North African landings and during 1943 ‘when the Twenty Committee chafed at the fact that no strategic deception went over from the U.K. between then and OVERLORD’.

This was a massive admission concerning the events of 1943.

I do note, however, that, when Bevan made his initial announcement to the XX Committee, he stated that the Chiefs of Staff had authorized him to undertake a deception plan. Yet the decision to create a new committee appeared to have been his own, and his claim that the DMI had given his approval to use his new sub-committee to execute the plan (rather than just develop it, gain approval for it, and arrange for others to execute) would appear to fly right in the face of the directives of the Chiefs of Staff. The departmental history, moreover, is very ambiguous about Bevan’s entitlement to execute plans himself, writing that the LCS ‘operated actively not only as a formulator of the main strategic deception policy and of specific deception plans to cover operations, but as the main agency through which, in so far as the United Kingdom was concerned, these plans were implemented’ [my italics]. So how did this initiative get by?

According to the authorized history, the initial project went according to the books. The deception operation that had been delegated to Bevan’s new committee was indisputably OVERTHROW (a feint across the Channel), since SLEDGEHAMMER had been discarded shortly before Bevan got started. (Churchill told the Cabinet on July 6 that SLEDGEHAMMER had been abandoned for 1942, yet advised Roosevelt on July 14 that both SLEDGEHAMMER and JUPITER were still active. Was he being duplicitous, was he merely confused, or was he simply trying to simplify matters for the President? I have no idea.) Bevan thus prepared a plan for OVERTHROW by August 5, and it was approved by the Chiefs of Staff on August 18. Michael Howard then proceeds to describe smoothly how the plan was executed: “It was implemented partly through visual displays, partly through the spreading of rumours, partly through the messages passed through the ‘special means’ of B1A.” But there is no mention of TWIST – or even the oversight of the XX Committee, as it happens. Howard then goes on to describe how the Germans were taken in, with Field Marshal von Rundstedt keeping defences strengthened against the assault that never came. “Overall, Operation Overthrow must be judged a major success”, Howard concludes, since German forces were kept on the alert right up to the eve of the TORCH landings in November.

On the other hand, Anthony Cave Brown embellished the story in Bodyguard of Lies. He described a misinformation campaign of planting seeds that an invasion was imminent, that the BBC warned the French not to take up arms until they received the signal, and he even declared that ‘MI-6, SOE and the XX Committee primed their agents with similar reports’. In so doing Cave Brown carelessly reinforced the notion that the XX Committee was exclusively an MI5 affair, but also strongly indicated that MI6 and SOE were given a role outside the controls of the XX Committee. Yet Cave Brown is not a wholly reliable source: while his descriptions are florid, his chronology is frequently haphazard: many critical events are undated. He muddied the waters by making the August 17 Dieppe Raid the core event of this deception, ignoring the fact that the OVERTHROW Operation was not approved until after the Dieppe Raid took place, and lasted until November. Such are the perils of trying to pack too many events into a narrative, and listening to too much personal testimony without careful attention to timelines.

The post mortem by the Chiefs of Staff was a little more sanguine. The minutes of November 26 (CAB 80/66-1), based on Bevan’s report, record that ‘the postponement of “TORCH” to 8th November rendered “OVERTHROW” a less probable operation, while shortage of invasion craft and the decision to cancel all troop and air movements for “CAVENDISH” robbed it of much of its plausibility.’ Other factors ‘militated against the success of this deception’, and ‘the enemy was not seriously concerned with the “OVERTHROW” threat’. Furthermore, the report was very lapidary about the role of Double-Cross, referring to the implementation by LCS in these terms: “Suitable messages to indicate a threat to Northern France were prepared and passed through various channels to the enemy.” Did the Chiefs really inspect the plan? And where did Howard’s confident appraisal come from? For what it is worth, the Minutes of the XX Committee never mention OVERTHROW, but much detail has been left out of the proceedings of that body.

Moreover, other chronological anomalies can be detected. Both Bevan’s representation to the XX Committee, and Liddell’s enthusiastic endorsement of the rival Committee, which gave such a prominent role to SOE and MI6, took place on August 25. Howard reports, however, that Bevan, on September 2, ‘complained to the Chiefs of Staff of the absence of machinery to implement his ideas’. He received the brush-off, being explicitly told to work with the departments that already existed. Yet by that time he had already announced to the XX Committee the formation of the TWIST Committee, and had the support not only of Liddell, but also implicitly of the top SOE and MI6 officers. Bevan was not being straight with the Chiefs of Staff, who were either ignorant of the TWIST Committee, or were turning a blind eye to it.

Another factoid that is highly anomalous, but maybe significant, is that Colin Gubbins, according to his Service Record at HS 9 630/8, was appointed CD (i.e. Chief of SOE) in September 1942, thus nominally replacing Charles Hambro. Yet all the conventional histories assert that Hambro did not relinquish his role, with Gubbins replacing him, until he was forced to resign by Lord Selborne in September 1943. If Churchill, who continually championed Gubbins, and prevented him being transferred to regular military duties, was trying to influence more directly the activities of SOE, Gubbins’s ascent to leadership would be evidence of such, and the concealment of the fact very suggestive.

Bevan was aware of the invidious position he had been encouraged to take up, and made a very puzzling and unsatisfactory statement to the XX Committee on October 1. The minutes record:

Colonel Bevan made a statement with regard to the directives issued by himself and with regard to the difficulties in which, in certain circumstances, he found himself. He agreed nevertheless that the Approving Authorities should be supplied with such general directives as he might issue from time to time, and would arrange for this to be done. He or his representatives would attend the meetings of the Twenty Committee in case any explanations were necessary.

The gobbledegook of this minute was inexplicably approved at the next meeting. (If Masterman had encountered such sentences in an undergraduate essay, he would surely have applied his red pencil to them.) It is difficult to know to what to make of it: to me, it suggests that Bevan was under pressure to execute something not completely above board, and beyond the ken of the Approving Authorities and the Chiefs of Staff. What ‘directives’ was he authorized to issue, for instance? That ‘nevertheless’ is telling, however, since it indicates that he felt entitled to conceal some of his enterprises from the eyes of his masters. That was the last XX Committee meeting he attended.

The role of Rear-Admiral Godfrey in this charivari is very peculiar. It will be recalled that he argued strongly for Bevan’s taking over the Chairmanship of the XX Committee – a position that Bevan did not want, as he may have had other ideas by then. Liddell had had to explain to Godfrey why the XX Committee was not ready for full-scale military deception. His Diary entry of August 26 describes how he outlined to an astonished Donaldson (the Director of Military Intelligence), accompanied by Montagu, why Bevan should not be Chairman, and how the transmission of deception messages might harm the DA network. The outcome was that Donaldson collaborated with Liddell on a letter to Godfrey explaining why his idea would not work.

The next time that Godfrey appears in the Diary is on September 17, where the following entry appears:

T.A.R. and I went over to congratulate the D.N.I. on his promotion to Vice-Admiral and to give him one of the POGO B/E notes and a clock fuse. Rather I fear with my tongue in my cheek, I thanked him for all the help that he had given us in connection with the Twenty Committee. He seemed pleased and said that he was deeply touched.

Why ‘tongue in cheek’? The comment has several overtones. As background clarification, I first cite Godfrey’s entry in the Dictionary of National Biography:

Godfrey’s insistence that intelligence must adopt a critical, sceptical and scientific approach and present its findings without fear or favour had led to early clashes with (Sir) Winston Churchill and, by mid-1942, his uncompromising and at times abrasive attitude had aroused the hostility of his colleagues on the joint intelligence committee who appealed to the Chiefs of Staff for his removal. The first sea lord, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, although he had only recently extended Godfrey’s appointment and approved his exceptional promotion to vice-admiral on the active list (September 1942), informed him that he would be relieved as soon as a successor could be found, a decision considered by many, including the historian Stephen Roskill, to have been both ill-judged and unjust.

So what was going on here?

‘Mid-1942’ is distressingly vague, but the first conclusion might be that Godfrey’s days were already numbered by the time that John Bevan took over, and all the frantic planning for OVERTHROW began. Historians have speculated over exactly why Godfrey was fired. Michael S. Goodman, in his Official History of the JIC, relegates to an Endnote in his Conclusions chapter a statement that his colleagues on the JIC prevailed upon the Chairman Cavendish-Bentinck to have him removed, with Pound performing the deed. David O’Keefe implies in One Day in August that Godfrey had to take the rap for the disastrous Dieppe Raid in August 1942, but has privately echoed to me the Goodman thesis. Is it possible that Godfrey challenged Churchill one time too many when the irregular TWIST Committee was set up?

The idea that it was Churchill behind Godfrey’s sacking is echoed in the work of another historian, Patrick Beesly. In his 1977 study of the Admiralty’s Operational Intelligence Centre during the war, Very Special Intelligence, he describes Godfrey’s challenging the Prime Minister’s estimates of U-Boats destroyed and his assessment of future strengths of the fleet, with Churchill trying to have Godfrey (and his ally Talbot) silenced. Beesly writes (p 36):

As for Godfrey, this was not the only brush he was to have with Winston, and may well have been one of the reasons for the astounding, not to say shameful, lack of any recognition of his immense services during the war, and omission which was, incidentally, deeply resented by every member of the Intelligence Division.

Thus the stories of Godfrey’s failure to be a team-player on the JIC may have been a canard put out to conceal the true reasons for his demise.

Liddell’s sophistical message of congratulation to Godfrey suggests to me two things: first, that he knew about the firing, and was not sorry to see Godfrey go, but also, that he may have accepted that the D.N.I. had genuinely the best interests of operational deception at heart, but did not want to recognize that openly. For it is easy to conclude that Liddell was the Villain here, and Godfrey was the serious intelligence officer who was searching for a way to convert what the XX Committee had built into a more relevant force in the military deception game. His method of doing that was to encourage Bevan to take it over: Liddell and Masterman saw that as a threat rather than as an opportunity.

The behaviour of Liddell was quite abject. He had obviously been targeted by Dansey, and maybe Menzies, and had been convinced that engaging SOE and MI6 agents and operatives in a deception game that was complementary to what the XX Committee was doing, without the disciplines of his B1A team, was a sensible strategy. He resorted to the weak argument that the XX Committee was too involved with counter-espionage (i.e. detecting other attempts by the Abwehr to insert spies into Britain) when that battle had already been won. The XX Committee was ready to take on tasks more vital to military deception, but for some reason Liddell funked it.

It is evident that he was outgunned by Menzies. At a meeting of the W Board on September 24, Menzies, with Cowgill’s assistance behind the scenes, made a play to diminish MI5’s role in deception. When Liddell stressed how his boss, Petrie, would strongly resist if the DA network were threatened by being forced to put inappropriate information through it, Menzies riposted that ‘he would put his foot down if certain action by the Twenty Committee did not meet with his approval’ (this from Liddell’s Diary entry). “It was now clear however what would happen if C’s interests and ours were in conflict”, Liddell added. Menzies tried to undermine the raison d’être of MI5’s creature, drawing attention to the fact that the ‘Twenty Committee had no charter’, also using as an excuse for his criticism the fact that Godfrey’s proposal that Bevan become chairman had been rejected.

These journal observations are confirmed by the official minutes, where Menzies expressed some outrage that MI5 had unjustly received much more recognition than had MI6 in the setting up of the XX Committee. A handwritten annotation declares the fact of the XX Committee’s lacking a charter, and the desirability of creating one. That was a scandalous admission by Menzies; after all, he was the senior intelligence chief who had presided over the W Board for almost two years, and if anyone was responsible, it was he. Donaldson tried to smooth over the dispute, but the die was cast. The XX Committee became a unit for supervising MI5’s B1A alone from then on.

And then – as if it were an aside – a casual minute is recorded as follows:

Col Bevan mentioned that he had instituted a sub-Committee consisting of Major Robertson, Lt. Cdr. Montagu, Major Foley, and Lionel Hale [of SOE, but not specifically identified!] to discuss the working out of certain cover plans from the aspect of getting them over to the enemy through double agents, rumour, etc.

It was all delightfully vague, but clearly well-intentioned and honourable. The Board nodded.

A handwritten addition to the minute ran: “This appeared to raise no difficulties”.

Thus Liddell – alongside the other MI5 officers involved, such as Robertson, Masterman and Blunt (!) – severely let down the security considerations of ‘double cross’ when they allowed the TWIST Committee to operate without proper oversight. OVERTHROW may have been enabled entirely through XX Committee DAs (as Howard claimed, but not Cave Brown), but TWIST was not dismantled in December, as a ‘small committee’ focused on a single ‘large-scale operation’. Moreover, if the TRIPLEX papers can be trusted, it had as many members as the XX Committee. We know (from Robertson’s careless comments in April 1943) that it took on a life of its own after the successful OVERTHROW deception. The TWIST Committee was not dismantled until its atrocious lapses became known to the Chiefs of Staff. And those lapses primarily involved SOE.

6. SOE, the Chiefs of Staff, and Churchill:

Since SOE was an upstart para-military organisation, while MI6 was an established intelligence-gathering unit, one might expect the Chiefs of Staff to have shown more interest in the activities of the former. One might also wonder whether their attention span was broad enough to keep up with what SOE was doing during 1942. Both these suppositions are probably true: the Chiefs of Staff were strong on strategy but negligent on tactics. As the overambitious plans for re-entry into Europe started to gel in early 1942, the Chiefs found the time to consider what SOE’s role should be, and to issue a careful directive on May 12, 1942. The document was titled S.O.E. Collaboration in Operations on the Continent, and the careful wording thus clearly excluded independent action. It should be pointed out, however, that the paper (in CAB 80/62) introduces the topic by stating that the War Cabinet ‘has approved that plans and preparations should proceed without delay for Anglo-US operations in western Europe in 1942 and 1943 [my italics]’. Thus a series of raids were planned for the summer of 1942, leading to ‘a large-scale descent [sic!] on western Europe in the spring of 1943’. Clause 3 ran as follows:

SOE is required to conform with the general plan by organizing and co-ordinating action by patriots in the occupied countries at all stages. Particular care is to be taken to avoid premature large-scale rise of patriots.

And Clause 5 described the kinds of subversive and disruptive activities that paramilitary organisations should perform, carefully framed as planned to occur as part of the Co-operation During The Initial Assault.

The instructions themselves are very clear: the suggestion of a timetable was, however, dangerously misleading. The Chiefs of Staff were well aware of the terrible reprisals that would take place if uncoordinated acts of sabotage or assassination were undertaken, and were thus careful to issue directives that the use of militias would have to be restrained until the timing were right. Colonel Gubbins knew this: as Director of Operations for SOE, he had disseminated, as early as April 1941, the following statement:

In conquered and occupied territories the eventual aim is to provoke an armed rising against the invader at the appropriate moment. It cannot, however, be made too clear that in total warfare a premature rising is not only foredoomed to failure, but that the reprisals engendered will be of such drastic, ferocious and all-embracing nature that the backbone of the movement will probably be broken beyond healing. A national uprising against the Axis is a card which usually can only be played once . . . . It is thus essential not only that these subterranean movements should be supported by us, but also that they should be sufficiently under our control to ensure that they do not explode prematurely. (from HS 8/272: reproduced in Olivier Wieviorka’s The Resistance in Western Europe, pp 33-34)

‘A card that can only be played once’: very solemn and authoritative words. Gubbins would refine and reinforce this philosophy in North-West Africa in early 1943. Yet an incipient problem can be identified: if the secret militias were substantively equipped with arms in the expectation of an early assault by professional forces, what would happen if that assault were delayed – from 1942 to 1943, and then to 1944? And how and when would the suitable candidate militia-men and -women be trained and kept at the ready? The enthusiasm of the secret armies had to be maintained (maybe a manageable problem), and the cache of dropped weapons had to be concealed from the Gestapo (a far more challenging task). And it is evident from other records of SOE activity that Gubbins’s instructions did not always percolate smoothly to all departments. Charles de Gaulle was a constant thorn, demanding more arms be shipped to the French paramilitary forces, and the Communists (who constituted a large section of the secret armies) were, in receiving their instructions from Moscow, far less scrupulous over the horror of reprisals, and were encouraged to engage in murderous attacks against Nazi officials.

Sir Alan Brooke was conscious of this policy, and obviously supported it. He had been appointed Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff in March 1942, and he took an active interest in the work of SOE, meeting with Gubbins and discussing with him how subversive operations in France might support the eventual landing. (The two had a close relationship: Gubbins had been Brooke’s personal staff officer at the Military Training Directorate from 1935 to 1938.) On June 2, he issued a memorandum that reinforced SOE’s role, and rejected calls for a Common Allied Staff to deal with subversive activities, claiming that ‘the present method by which S.O.E. works in close collaboration with our planning staff, and with the Chiefs of Staff Committee, enables activities in occupied Europe to be co-ordinated with the whole war plan’, words that should have come back to haunt him. But he had a lot on his plate and was otherwise engaged during the rest of 1942: he was spending the summer resisting multilateral efforts for a premature landing in France, and the pressures on him would endure for more than a year. On the other hand, one man reportedly kept a very close interest in SOE’s operations – Winston Churchill.

Churchill had avoided working with Hugh Dalton, the minister whom he had appointed with responsibility for SOE in 1940, partly because he disliked Dalton’s socialist ambitions for Europe, but also because he resented the booming lectures that the Labour man delivered to him. Dalton was, however, replaced by Lord Selborne in February 1942. Selborne, by subtly keeping Churchill informed of SOE’s achievements, renewed the Prime Minister’s interest in the exploits of SOE agents. Churchill was also enthused by the appearance of John Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down, an inspiring novel about resistance in Norway, which he read in late May 1942. These were exactly the type of adventurous enterprises that fired him up, although such picaresque ideas sometimes did more harm than good, as Sir Alan Brooke’s diaries constantly remind us. Selborne tried to talk him down, reminding him of the Gubbins doctrine. The Chiefs of Staff noted Selborne’s rebuff, namely that ‘scattering weapons and charges from the air for franc-tireur use . . . would lead to reprisals, and is therefore only recommended to coincide with an Allied invasion of the Continent and to enable saboteurs to cut railway lines of communication’. Yet Churchill’s enthusiasm could not be extinguished completely.

Moreover, another stronger bond was built. In Churchill & Secret Service David Stafford emphasises that John Bevan and the Prime Minster enjoyed a very close relationship. This account is probably trustworthy, despite the fact that Stafford’s employment of the facts is occasionally a bit wayward, and his use of sources is questionable. For instance, he suggests that the LCS was set up only in 1942, and that Bevan was its first head. (This is a pardonable error, as the unit was officially named the LCS only in June 1942, as I explained earlier.) The JIC had approved the new unit, to replace the Inter-Services Security Board, on October 9, 1941, and Stanley was appointed a few days later. The Chiefs of Staff were slow to recognize the LCS, and issued their first directive to it at the same time it formally received its name.

Stafford also refers to Operations JUPITER and SLEDGEHAMMER as being the deception operations undertaken to deflect attention from TORCH, when it was in fact OVERTHROW that superseded SLEDGEHAMMER. And he uses as his source for the claim that Churchill and Bevan ‘cooked up deception plots in late-night sessions over brandy’ (the LCS offices resided in the Cabinet Office complex) to Bodyguard of Lies by Anthony Cave Brown, not always the most reliable of chroniclers. Nevertheless, it is certain that Churchill had a much more collegial relationship with Bevan than he did with Stanley, and Bevan’s appointment may not have been coincidental with Churchill’s new-found enthusiasm for SOE derring-do.

Thus Churchill, with his revivified enthusiasm for maybe violent subversive activity, and unable to forget his private commitments to Stalin, perhaps became too close to the activities of SOE. In any case, he was well primed for some intense clashes with the Chiefs of Staff in the second half of 1942.

7. War Cabinet Meetings: June-December 1942

Despite the fact that the War Cabinet had agreed on June 11 that ‘we should not attempt any major landing on the Continent this year, unless we intended to stay there’ (a motion that Churchill himself proposed), Churchill continued to push his Chiefs of Staff about SLEDGEHAMMER, ROUNDUP and JUPITER. On June 15, he issued a memorandum on the necessity of engaging ROUNDUP with vigour. On June 21, he had a meeting with Roosevelt at the White House (with Brooke present), at which it was declared that ‘the United States and Great Britain should be prepared to act offensively [in Europe] in 1942’.

The Chiefs of Staff invited Paget (C.-in-C., Home Forces), Douglas (A.C.C.-in-C., Fighter Command, and Ramsay (C.-in.-C., Naval Command) to comment on Churchill’s memorandum of June 15. They were politely rather dismissive of their Prime Minister’s ideas, but did come up with a rather alarming conclusion about the use of ‘Patriot Forces’. It ran as follows:

The most suitable methods of raising the patriot forces in FRANCE and making use of their great potential value are under investigation in conjunction with S.O.E, and it is too early yet to state what can be achieved. It is obvious, however, that the deeper and quicker the penetration of the main assaults the greater will be the extent and value to us of the risings. Furthermore, judicious handling of the patriots may turn the diversions considered in paragraph 11 into large scale risings which will become a serious embarrassment to the enemy. In both cases, however, arms and equipment must be supplied in large quantities if the patriots are to be of any real assistance. For rapid distribution, such stores must be brought over in motor transport, the carriage of which, as we have shown already, is a serious problem owing to the shortage of landing craft.