I post this Special Bulletin, outside the normal monthly cycle, to offer an initial commentary on the recent MI5 declassification of several Personal Files. I concentrate on the first of the PEACH (Kim Philby) files.

“Government files that are allowed into the public domain are placed there by the authorities as the result of deliberate decisions. The danger is that those who work only on this controlled material may become something close to official historians, albeit once removed. There is potential cost involved in researching in government-managed archives where the collection of primary material is quick and convenient. Ultimately there is no historical free lunch.” (Richard J. Aldrich in The Hidden Hand: Britain, America and Cold War Secret Intelligence, p 5)

The January 2025 Release

I came across this text when belatedly reading Aldrich’s epic 2001 volume for the first time last month. It has a bold ring of truth, and I implicitly agree with it. Yet, as with any such broad-brushed assertion, I believe it merits closer inspection. Who are those ‘authorities’? Are the persons who decide that files may be declassified in 2025 in essence of the same calibre and school as the experts who judged that some of the information revealed in them was too sensitive seventy years ago or more, and had to be redacted? Is there a level of corporate memory in existence here? Are regular meetings held, and minutes taken, whereby the lore and potential exposures are solemnly recorded for posterity, so that wise decisions are always taken to protect the surviving family members – and of course the Institution of MI5, the Foreign Office, and perhaps MI6 themselves? Can any individual, or Committee, hold all the relevant facts at their fingertips to be able to judge what is safe to release? For example, who at MI5 today can explain the whole FEABRE/PHILBY imbroglio, and provide guidance on its implications? And are there perhaps some subversive agents at work, resembling those who once leaked the essence of some documents to outsiders out of frustration at the misdeeds of their senior officers, their successors now believing that the public deserves to be told more? I do not know the answers to those questions, and I am not going to attempt any hypotheses.

The latest tranche of KV (MI5) Personal Files provides an excellent case-study. The announcement from The National Archives of January 14 was headlined by the following statement: “The release reveals new details in the cases of the Cambridge spies Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt, and John Cairncross, including their confessions, and also sheds light on related cases including Constantin Volkov, and Philby’s first wife Litzi.” It then lists ninety-seven consecutively numbered Personal Files (PF), comprising those maintained on the three listed above, as well as several others (see https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/about/news/latest-release-of-files-from-mi5-2/). Is this a counter-example to Aldrich’s ‘free lunch’?

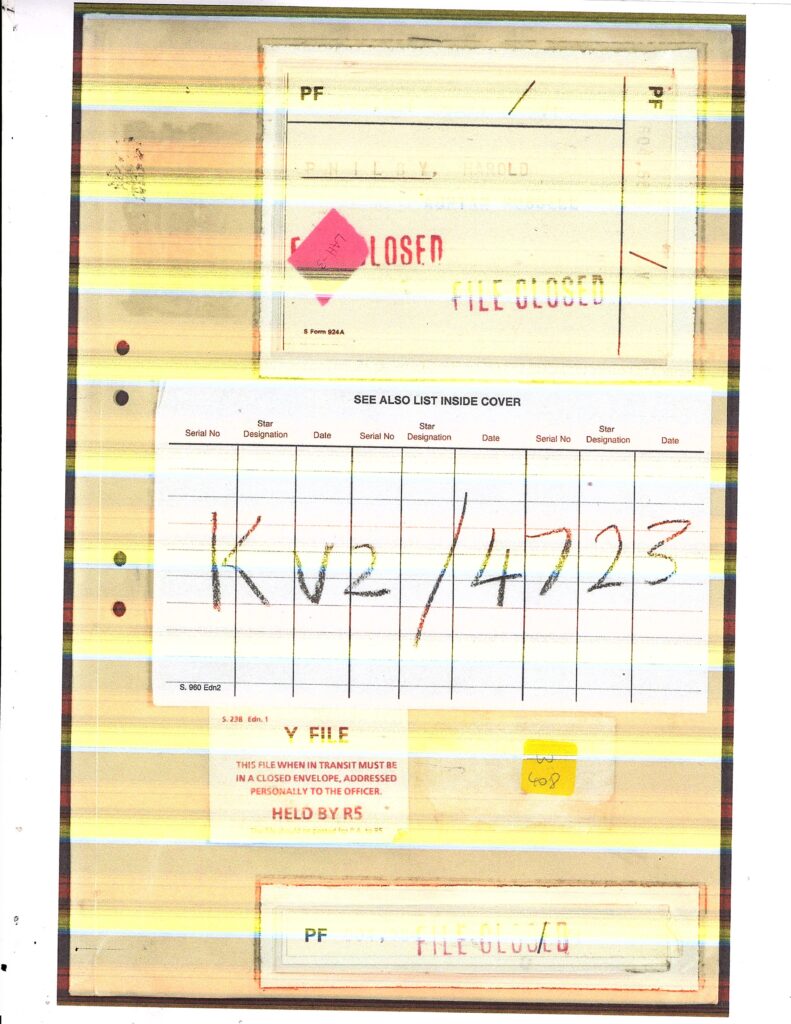

Apart from stating the obvious that it will take anyone months and months to analyze and interpret this material properly, I shall restrict my comments in this piece almost exclusively to one file, the first of Kim Philby’s set of twenty-one, comprising KV 2/4723-4743. I make a very important point, however, that I think has eluded other commentators. These files derive from Philby PF 604584, namely the file created when Philby emerged as the subject of the June 1951 investigation known as the PEACH Inquiry, PEACH being MI5’s codename for Philby. Indubitably, much information on him was maintained before the events surrounding the escape of Burgess and Maclean, but it is scattered among other files, the most important of which (in my judgment) has not been declassified.

Files on the Philbys

Notes on Kim first appeared in the file of his father, Harry St. John Philby (PF 40408), which was created in 1926, and was declassified as KV 2/1118 & 2/1119 in October 2002. Kim came to the notice of MI5 as a member of the Cambridge University Socialist Society in 1933, but the service presumably thought that, since the son had a famous father already under watch, it was appropriate to post occasional items about him in PF 40408. I have written earlier about the exchanges between Valentine Vivian and Guy Liddell concerning Kim’s application to join MI6 in 1939, which can be found there. Yet, in late 1939, a file was opened on Lizy [sic], aka Litzy or Litzi, Philby, in which can be found very provocative, and perhaps incriminating, information concerning her husband, such as a full list of the many trips abroad that Litzy made in the 1930s. (It seems that that information was collected only in June 1951, after Philby was called back to the UK: Helenus ‘Buster’ Milmo tried to exploit it in his interrogations of Philby in December, but he failed to break the suspect.)

This file is numbered PF 68261, and it was released simultaneously with the PEACH files listed above, as KV 2/4663-4667, and does not terminate until 1974. The catalogue description states that the file was opened on October 26, 1940, but it contains entries dated from 1939. (In fact it contains NO entries for 1940, which is very suspicious.) The presence of entries from 1939 is due to the transplantation of relevant items from her father-in-law’s file after her own file was opened. Yet, beyond these desultory items (that extend into 1942), the first entry in the file bears the date September 16, 1945, and several of them refer to a Litzy Feabre ‘who had married an Englishman’, the authors presumably unaware of her real identity. It is remarkable that the file was developed seriously only at that late date: with her background, Litzy surely must have come under MI5’s microscope before then, especially since her husband had been a ‘person of interest’ during the 1930s. Why would a file be started on her only at the exact time that her husband became an officer in MI6, but then no entries made until the war was over? Her file shows clearly that many of her multiple trips abroad during the 1930s were recorded, and her activities during the war were surely worthy of notice. I suspect that PF 68261 was a holding-place for a whole lot more, but the evidence has been carefully weeded.

I referred to the existence of PF 68261 in coldspur postings two years ago (March and April 2023: see https://coldspur.com/litzi-philby-under-the-covers/ and https://coldspur.com/kim-philby-always-working-for-sis/ ), and assumed that it was a designated Kim Philby file, in which his wife was joined. I had found several references where items (from Georg Honigmann, for example) had been copied into the thinly disguised ‘Lizzy Feavre’ file, Feavre (or Feabre) being a clumsy and mysterious alibi for Litzi Philby. Now that it has been declassified, we can see that it is truly dedicated to Litzy, with attention paid towards the end of the war to her relationships with such as Edith Tudor-Hart and Georg Honigmann. By this time, of course, her husband was established as an upright officer in MI6, and thus no longer merited any special attention – apart from the incidental questions raised by the behaviour and actions of his spouse. I shall have to return to the fascinating revelations from Litzy’s file another time.

What is nevertheless significant is that KV 2/4723 explicitly draws attention to the existence of PF 40408, and the annotations indicate that a few items have been extracted from it to be inserted in the PEACH file. Some have been removed to the PEACH file, and thus appear only as vestigial entries in the Minute Sheet of KV 2/1118. Curiously, the two items representing Vivian’s communications with Guy Liddell concerning Kim’s recruitment by Section D (sn. 57b and sn. 64a, of September 24 and October 2, 1940 respectively), have not been transferred to the PEACH file – whether this was by oversight, or done deliberately, I have no idea. What is still surprising is the fact that so little information about Philby’s activities in the 1930s exists. We can be sure that some potentially damaging observations were recorded, by virtue of those few items that have survived after being extracted to PF 604584, but the cupboard is very bare. If there had been another Philby file, I believe there would have been references to it somewhere – unless the weeders have done a superlatively conscientious job.

One of the reasons that the research potential of these records is so great is the light they show on the suspicions about Philby. Last March, in ‘Dick White’s Tangled Web’ (https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-tangled-web/ , I drew attention to a passage in Bower’s biography of Dick White that ran as follows:

Shortly after that encounter, White immersed himself in the research prepared by Arthur Martin and Jane Archer about Philby’s past. For the first time, Archer produced a thin MI5 file compiled in 1939 and then forgotten. A report contrasting Philby’s communist sympathies at Cambridge and his sudden espousal of fascism made a deep impression. Alongside was Philby’s own résumé. One coincidence was interesting. Philby mentioned his employment by The Times covering the Spanish civil war. Krivitsky had claimed that among the Soviet agents he controlled from Barcelona was one unnamed English journalist.

I note a few important points from this passage. The encounter was White’s so-called ‘interrogation’ of Philby immediately after his return – actually three separate interviews on June 12, 14 and 15. (Transcripts appear in KV 2/4723, and I shall report on them later in this piece.) Bower states that White immersed himself in Martin’s research after the encounter: of course, he should have done so beforehand, in order to prepare for the interview properly, and surely had given it at least a cursory look-over, as Martin had left for Washington on June 11, with the dossier on Philby. Thus Archer would also have produced the ‘thin file’ some weeks before. Yet what was this ‘thin file’? It was clearly not the file on Philby père, which was quite fat. Moreover, that file does not contain any report contrasting Philby’s youthful communism and sudden conversion to fascism. Neither does it contain Phiby’s own résumé. The Litzy Philby file was indeed opened in 1940, but does not contain these two items, either. The PEACH file has been populated with five brief items from the 1930s, taken from PF 40408, (which I analyze below), but it does not contain those two critical pieces identified by Bower’s inside informant.

I thus conclude that a further file – maybe the special ‘List’ file for Kim and Litzy, namely L.212 (884), which is frequently referred to in the recent Philby batch – exists, and is yet to be released. How it could have been ‘forgotten’ is simply unimaginable. It may well have been given special security status, so that no prying eyes of junior officers could casually look it over, but I am in no doubt that White and Liddell knew about it, and Jane Archer (who had returned to MI5 some time after the war, following her banishment to MI5 at the end of 1940) would have been extremely interested in it. I do not regard it as likely that she knew about it when she was still employed by MI5, as her sharp eye would have made the connection between Krivitsky’s hints and Philby’s admitted role as a journalist in Spain. Unless, of course, she was party to the Philby * volte-face as well . . .

[* ‘The Philby ‘volte-face’ refers to my theory, unconfirmed by any archival material, that, after the Nazi-Soviet Pact of late August 1939, Philby, fearing that the defector Krivitsky might soon unmask him, broke cover, used the Pact as a pretext for claiming to MI6 that he (and Litzi) had renounced their communism sympathies, and announced that he was ready to serve British Intelligence. See https://coldspur.com/kim-philby-always-working-for-sis for further details.]

KV 2/4723 – Analysis

I now proceed through the file, offering comprehensive analysis of the miscellaneous items before moving to the bulk, which originates from 1951.

- Pre-War Miscellanea

1a is extracted from 16x of KV 2/1118, dated 7.9.1933: a notice that H.A. R. Philby is a member of the Cambridge University Socialist Society.

2a is extracted from 17b of KV 2/1118, dated 15.11.1934: it refers to Smolka’s planned partnership with Philby (which exists in the Smolka file as well).

2b is dated 16.8.37, and is sourced from OF.511/3: it notes that Philby is now a member of the Anglo-German Fellowship, according to its 1935-1936 Annual Report. A directive indicates that it should be extracted to PF 604584, but, since that PF did not yet exist, the procedure may not have happened until December 1967, a date printed on the item.

3z is an undated extraction from a Special Branch Report on Smolka, dated 19.8.1938, in which Philby is mentioned. The original full report can indeed be seen at 220D in Smolka’s file at KV 2/4169.

3a is dated 27.9.39, and consists of the Trace Request from Section D of MI6 to MI5, recording that Philby was a correspondent with the Times during the Spanish Civil War. This has likewise been extracted from PF 40408, sn. 44a, confirmable from the Minute Sheet, although the item does not specifically state the source.

4z is another freshly typed extract from 121b in the Smolka file.

4a describes information gained from Special Branch about the Philbys from an acquaintance, a Nazi sympathizer named Gerhardt Egge, dating from 19.12.39, but not entered until 9.2.40, apparently in PF 68261/Y, as sn 1w. This item appears as 47a in KV 2/1118, and is noted there as being moved to PF 68261.

6a, dated 19.6.40, is another Trace Request on Philby from Section D of MI6 (although it had three days earlier been absorbed into SOE), to which MI5 notes the previous request, and confirms that Philby is working as B.E.F. correspondent for the Times. It is not explicitly sourced.

6b and 7a really concern Philby senior, the latter having written a letter referring to Kim, which had passed through censorship on 26.5.40. They reflect (but are not images of) sn.s 54a and 53b in KV 2/1118.

8ab & 8abb are minor items taken from Smolka’s file by Brooman-White in B1g, dated 12.9.42.

These few items constitute the total up to the end of World War II, confirming that the items ‘discovered’ by Jane Archer have not yet been released, and that the L.212/884 (List) file probably holds the key. The single entry for ‘5’ has been redacted.

The next few items are important records, but mostly unremarkable. Philby’s divorce from Litzy is noted as having been made absolute on 17.9.46 (without any details), and his marriage to Aileen (25.9.46) is recognized on August 1, 1947. The record then jumps forward a few years. On June 6, 1951, B2A recommends that a Home Office Warrant be placed on Philby in Washington, unaware that he is being ordered home the same day. Philby’s famous ‘re-think’ memorandum concerning Burgess, dated June 4, is registered. Data on Philby’s relatives are assembled, and Ronnie Reed seeks his passport papers. A note on June 11 points to White’s interview the following day, and indicates that B2b is preparing a brief for it – a bit late, one might say. Parts of an interview White has with one Flanagan (PF 604589), who knew Burgess and Philby well, are recorded.

- Philby’s Statement

There next follow two long statements (11 and 7 pages, respectively) typed by Philby, at Dick White’s request, undated, describing his relationship with Burgess, and providing a potted curriculum vitae. It is scattered with outright lies, mischievous asides, and unlikely lapses of memory. His life-story is quaint: he claims that is father pushed him into the Cambridge University Socialist Society in 1929. About his time in Vienna, he states that his money ran out, and that he (not ‘he and his wife’) decided to return home in May. (So much for attending the May Day Parade in Camden Town, as Chapter 2 of his memoir, published in The Private Life of Kim Philby, later recalled). He also states that the marriage was ‘hurried’, and that it took place in April, two or three weeks before his [sic] return. He was only two months late in his dating: it is a foolish man who forgets the date of his own marriage. He claims that the marriage was ‘wrecked’ by the end of 1936, but he conveniently cannot remember his wife’s travels at this time. He vaguely remembers helping her get a passport in September or October 1939. (What he does not say is that, in his appeal to help Litzy get to Paris on September 26, 1939, he referred to the fact that they shared a lease on the flat in Paris, which would expire in October, and that Litzy needed to travel there to remove their effects – see KV 2/4663, sn.17a.)

When he joined SIS in 1940, he considered divorce, but his lawyers told him his chances were slim. He claimed he did not see Litzy between that year and 1945. (There is no mention of the job reference he gave her, as described to Seale and McConville by Vivian.) And then, in that same year, Litzy contacted him, wanting a loan. He helped her out, and raised the divorce question again. His lawyers were now optimistic, and Litzy agreed to start proceedings, ‘which were successfully concluded the following year’. After that he claimed that he neither saw her or heard from her, apart from visiting her in Maida Vale during the proceedings. Thus the sudden travel abroad in the summer of 1946, with Litzy meeting him in Vienna or Paris for the quickie divorce, is completely ignored. (If, indeed, a divorce had been granted in the UK, there would be a record of it. How come no one has been able to locate it?) An attached note recording the PF numbers of everyone mentioned in Philby’s statement indicates that he made his deposition on June 12, after White’s first interview.

At this stage, a clumsy attempt to obscure the name of Esther Whitfield, Philby’s secretary, is made. (She had a PF 604688.) White cables Washington, reporting on his ‘interrogation’ ‘(I saw Philby yesterday’). He is eager to promote the notion that Guy Burgess may have picked up information on the Embassy leaks from Ms. Whitfield, or happened to have seen relevant documents in Philby’s office. Philby deemed it impossible that Whitfield could have been indiscreet, but he also gave helpful hints about Burgess’s visits to New York, and White even ventures that Guy may have made contacts with Russians in America. A transcript of White’s discussion with Goronwy Rees of June 7 is then inserted in the file.

Director-General Sillitoe next sends a cable from Washington (dated June 14), reporting on the urgent investigations of the FBI and the CIA. “If they discover his first wife was a Communist realizing we had withheld this would inevitably disrupt present good relations with F.B.I.”, he wrote. Poor Sillitoe had been kept out of the loop. He did not realize at the time that Philby’s marriage to the Communist Litzy had been Point 4 of the dossier that Arthur Martin had carried with him when the pair travelled to Washington together. White responds the same day, indicating that Philby had been twice questioned. He confirms the Litzy details, but generally waffles about the outcomes. Another interrogation is set up for Saturday June 16. And thus we come to the main course.

- The Philby ‘Interrogations’

I am not going to parse the transcripts of these interviews in detail. Yet I will strongly claim that the methods displayed by White are an object-lesson in how NOT to conduct interrogations. They took place in a room in which the noise of telephones and other movements interrupted the conversation, and interfered with the sound-recordings. White showed himself to be hopelessly unprepared for the exchange, not having read and internalized the papers prepared for him. He had not thought out the questions he wanted to pose to Philby, and, in those cases where the question was loaded, he did not know the answer when he should have done so. He interrupted his subject, talked too much, and mumbled vaguely when he opened his mouth. He led Philby by feeding him possible ideas. The whole exercise was not an interrogation at all, but an attempt to make Philby agree to make some sort of statement on the whole business while incriminating Burgess. Overall, White made Arthur Martin look like Buster Milmo. Moreover, while White did go back over the transcripts to correct the obvious errors, and undetected names, he did not perform a comprehensive job. He should have been – and probably was – utterly embarrassed by his whole performance.

In the first interview, White tried to get Philby to shed light on Burgess’s full career. Philby attempted to be helpful, actually winding White up. At one stage he replied: ‘That would be a – do you mean for instance, that there was an early tie-up between GUY and MACLEAN . .?’ and followed up with the speculation that MacLean’s nervous breakdown was ‘due to his catching some sort of wind of the Embassy leakage in Washington’. Philby then fostered his theory by describing how Maclean must have become on the alert since papers were being withheld from him, and how Maclean may have judged that, since Guy was okay after the leakage, he could organize the getaway. There are over forty pages of this stuff, the absurd aspect being that White has already made up his mind that Philby is guilty, something that Philby probably recognizes himself, yet they appear to be chatting away like old chums, with White’s objective at this time not to alienate Kim, and to have the indictment come from somewhere else.

White reported to Washington on his second ‘examination’ of Philby (which took place on June 14) on June 16, observing that Philby ‘answered all questions put to him about his own position and his association [with] BURGESS with frankness’. [Is that right, Sir Humphrey?] He emphasized Philby’s denial that he had ever been a Communist or in league with Communists, and that he had completed his separation from Litzy in 1936. Before the transcript of the second interview a few artefacts have been inserted, including copies of letters and a cable sent to Burgess by Philby from Ankara, an affidavit from his grand-mother, dated February 14, 1934, to support the legality of his marriage ceremony, and Kim’s letter from Washington of May 11 complaining about Lincoln car that Burgess abandoned. These items had all been recovered from Guy’s flat on June 7 (thus confirming an important date). Philby was apparently also interviewed by Percy Sillitoe, since the Director-General asked him to put on paper what he had said during their discussion. Philby’s report was entered on June 18. Next appears the highly inaccurate testimony by a diplomatic acquaintance (name redacted, but identifiable as Denis Greenhill) concerning Philby and Burgess ‘who were classmates at Oxford’.

This leads to the transcript of this second interview, delivered on June 19. It is another absurd, rambling conversation in which White again tried to encourage Philby to agree with him that Burgess may have had ample opportunity to pick up intelligence about the Embassy leakage. White even asked for useful facts from Philby which would help MI5 disassociate him from communists. He asked about Smolka, but got his first name wrong, and then became distracted by their bringing up names of Communists from the 1930s. It was all very pointless. White rather desperately brought up the abandoned trip to Moscow in 1940 made by Burgess and Berlin, but did not know what to ask about it. White confused MacArthur (the General) with McCarthy (the anti-communist Senator). They exchanged awkward sentences about homosexuals. White asked Philby whether he was ever a member of the Apostles. ‘No, no, no!’ was the reply. White wanted Philby to give the matter of a statement his utmost priority, and the session ended with his saying to his interviewee, with that crisp and elegant articulation for which intelligence chiefs are renowned: “I mean what is officially said eventually when this whole thing comes out according to how things go, I feel that sooner or later you will have to be in a position to make some statement, which you and ourselves can use vis-a-vis C.I.A. and F.B.I.” “Yes”, replied Kim.

For the dessert course of the meal we have a 57-page transcript of the third interview of June 16. At least by now White has read Kim’s statement about Burgess, and they compared notes about such important matters as the relative beauty of Goronwy Rees’s lover Rosalind [actually ‘Rosamund’: Ed.] Lehmann. White had very little to say about Philby’s statement on Guy, but was prepared to lay down the law: “I am afraid there is no escape GUY was working for the Cominform [actually, Comintern: Ed.] in 1936.” Kim was flabbergasted: “Is that so?????” (It is not clear why the transcriber has felt it essential to multiply the question-marks.) Dick reminded Kim that he [Kim] never was a communist, lest he forget. And so they meandered on, talking about Vienna and Kim’s marriage. Kim told Dick that Litzy never lifted a finger on behalf of the Communists in England, although the couple had to correct themselves over Smolka and the unnamed Honigmann (whom Kim later claimed that he has never heard of). The exchange resembled more of a ‘Desert Island Discs’ radio programme, with White performing his Roy Plomley role by offering helpful prompts, such as that concerning the Philby’s circumstances in London: “You weren’t very rich at that time”. Kim suggested that Litzy must have reverted to Communism because of the influence of that unpleasant Honigmann fellow. The story about Litzy, and her movements and her finances, is a mess, but White failed to attack, or point out flaws in Philby’s responses.

They rambled for a while about Spain, and Philip Jordan (did he know Guy?). Klugman was discussed. And then they moved on to an important connection – which could be almost overlooked. An incoherent exchange concerning Burgess led them to discuss ‘Freddie’. The transcriber cannot make out the name, so she writes ‘(Coombe?????)’. Kim responded very positively to this reference, and Dick continued, as the transcriber valiantly tried to make sense of it all: “That’s one of the (things??) that were? under examination before he went out to (the United States???)”, helpfully adding ‘from security’, to suggest that Burgess was under surveillance because of the Coombe business. Kim got excited, and told Dick that he is ‘almost certain’ that he was correct in saying that Guy met the Coombe fellow in Washington.

White again failed to pick up the point, but then he was probably aware that he had said too much. For it came to me that this ‘Freddie Coombe’ was in fact ‘Freddie Kuh’, a notorious American journalist and spy for the Soviets. Burgess had been discovered passing secrets to Kuh in London before he left for Washington, as Guy Liddell’s diaries confirm (see especially January 23, 1950). The reason this is so important is that White had declared elsewhere that Burgess had been under no suspicion at the time he returned from the USA, and his revelation here confirms one of the multiple reasons for keeping a close eye on Burgess, as I related in my piece on Rees and Blunt a few months ago (see https://coldspur.com/an-anxious-summer-for-rees-blunt/ ). White notably did not correct the name of ‘Coombe’ in the transcript.

Philby then described Burgess’s recall to London, explaining that it was all arranged by Burgess as a successful ‘wangle’. The pair discussed Burgess’s possible motivations for plotting with Maclean, with Kim suggesting that Guy perhaps felt responsible for his comrade. Kim helpfully added that the Russians must have come in at an early stage on the escape plan, and that it could have been Guy in the USA, or Guy in London. Or else through the Dane (Klixbull, probably, whose name came up in the Flanagan interview, though as Kilxbull) – a whole new vista to be opened. Dick nervously wondered whether Guy must have had a collaborator – who could have been Russian, of course. The discourse continued incoherently for several more pages. I leave it to Charlotte Philby to make sense of it all.

The file petered out with some details about Philby’s two sisters, and a note that there had been no trace of Lizzie Honigmann or Philby during the past two years. A cable from Washington dated June 26 indicated that the FBI wanted the results of the Philby and Auden interviews. (Readers may want to return to My Silent War to re-assess Philby’s account of these interrogations, the first of which, so he claimed, Jack Easton attended. Philby points out that White missed out on the opportunity to trap him over his expenses in Spain, when he had been a freelancer.)

Conclusions

- I re-emphasize that what we have been given on Philby is an assortment of three separate files: the traditional file on Harry St. John Philby, and the newly released files on Litzy, and on PEACH. Vital information has still been withheld, and it will probably be found in the L 212(884) file.

- Readers should be wary of trusting what breezy and broad-based analyses of these newly-released files may emanate from experts such as Calder Walton or Ben Macintyre. What I have presented above concerns just one file on Philby. There are another twenty to be processed. They need to be inspected closely.

- If you ever wanted confirmation that Philby was mendacious and slippery, and that his word should never be trusted on anything, this file should provide it.

- The ‘interrogations’ were a disaster. Dick White was a clown, and his antics were shocking. He was a man utterly out of his depth. He could not imagine how his plots could blow up, but he managed not only to survive, but to be so highly regarded that he headed both MI5 and MI6 in his career. Quite amazing.

- Who are Flanagan and Klixbull? A pair of music-hall artistes? Or spies? Answers on a postcard, please.

[Postscript: 8:08 PM, February 14: I believe that FLANAGAN represents a clumsy attempt to conceal the name of David FOOTMAN. I notice that the PF allocated to FLANAGAN at sn. 11e in this file is 604589, the same as that allocated to FOOTMAN elsewhere.]