How did the Foreign Office and MI5 so massively mess up the surveillance of Burgess and Maclean?

This month I explore the first topic concerning the ‘Missing Diplomats’, an affair that continues to perplex – see last month’s bulletin: https://coldspur.com/the-missing-diplomats-literature-since-1987/. I am dedicating a complete report to this first set of questions, as its scope is so large, the analysis is pivotal to the exercise, and the implications are very significant. I shall cover the remaining questions at the end of April.

This is how I introduced the topic:

- ‘The Third Man’: Was the Third Man the leaker who first gave the warnings about HOMER? Or was he the person who supposedly precipitated the escape at the last minute? Did the UK authorities deliberately make the question ambiguous? Did the question help to divert attention from Blunt’s true ‘third man’ role?

Contents:

Dispelling the Rumour

The Third Man

Hoover Intrudes: The Commons Debate

The Petrov Files: The Defection

Burgess & Maclean

MI5 Reacts

Further Entanglements

Reinspecting Cookridge’s Claim

Nervousness in London

Philby’s Story

The Washington Connection

Summary and Conclusions

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Dispelling the Rumour

On July 1, 1963, Edward Heath, Lord Privy Seal, appeared in the House of Commons intending to put the longstanding ‘Third Man’ rumour to rest. He addressed the Members of Parliament with the probable intention of forestalling any public announcement that Kim Philby, who had disappeared from Beirut earlier that year, might soon make in Moscow. After claiming that no evidence had been found in 1951 that Philby had been responsible for warning Burgess and Maclean, or that he had betrayed the interest of his country, he declared:

The secret services have never closed their files on this case and now have further information. They are now aware, partly as a result of an admission by Philby himself, that he worked for the Soviet authorities before 1946 and that in 1951 he had warned Maclean through Burgess that the security services were about to take action against him.

This statement contained so many ambiguities and half-truths that it should have provoked further questions, even at this late stage. When was the admission by Philby made, under what circumstances, and to whom? Had Philby really stopped spying for the Soviets – phrased as the almost respectable ‘Soviet authorities’ – in 1946 (something he erroneously claimed in his ‘confession’ in Beirut)? How did the secret services know that for sure? What other sources had led the secret services to their conclusions? How and when had Philby (located in Washington at the time) communicated with Burgess to warn Maclean? How imminent was the ‘action’ to be taken against Maclean? If the security services had been about to make such a move against Maclean (alone), why did Burgess accompany him?

Marcus Lipton, a member of parliament who had originally raised the possibility of Philby’s being the ‘Third Man’ in a parliamentary debate in October 1955, had been forced soon after to make an apology when Philby, after conducting his notorious press conference, was publicly exonerated. Eight years later, Lipton now asked: “Does the Lord Privy Seal’s statement mean that Mr. Philby was, in fact, the third man that we were talking about at the time of the disappearance of Maclean and Burgess?” He received Heath’s reply: “Yes, sir”.

Yet had anyone (‘we’?) in fact been talking about a third man in June 1951? Apart from a vague and unsupported rumour aired in the Daily Express on June 21, the answer is ‘No’. Had the memory of the honourable and gallant member for Brixton really been so frail? At first, the Foreign Office had claimed that it knew neither the reason for the duo’s sudden departure, nor whither they had vanished – let alone that a collaborator had aided their escape. This was despite the fact that, in an unguarded moment, Percy Sillitoe, the MI5 director-general, had told the Daily Express in August 1951 that the pair were ‘behind the Iron Curtain’ (see KV 2/4106, sn. 273b). The mood of studied relaxation continued. A year later, in July 1952, Anthony Nutting, the Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, answered a question from Lipton in the House of Commons by stating that the search was still continuing, adding rather nonchalantly that Burgess and Maclean had been dismissed from the service on June 1.

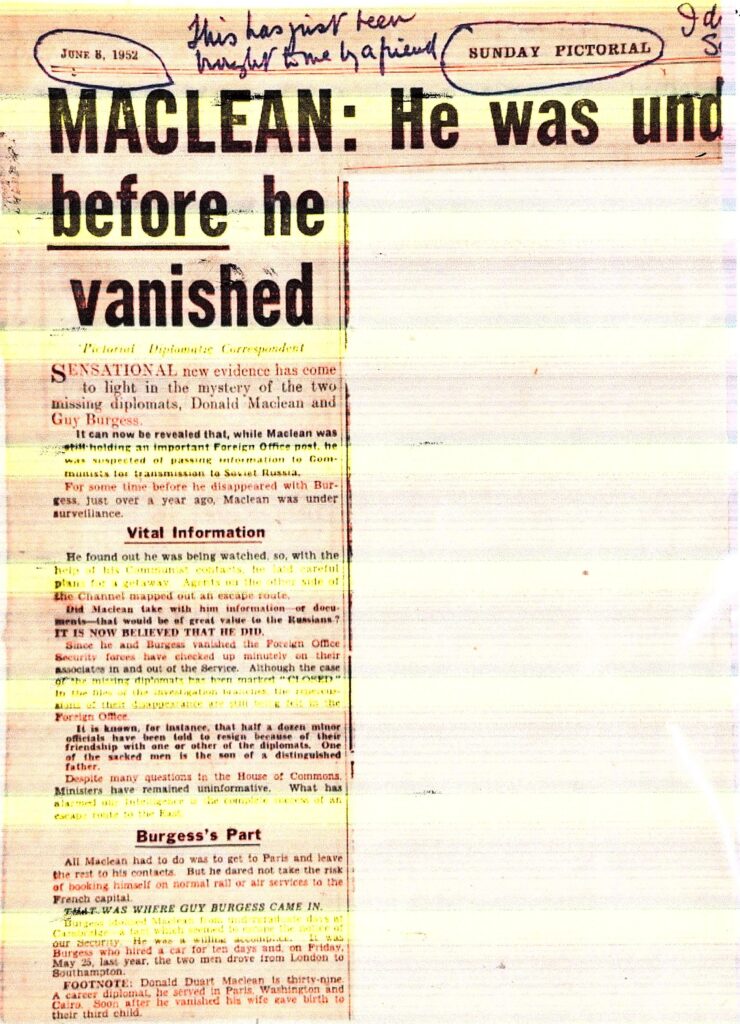

With rumours about their possible political unreliability floating around, the popular press analysis was that the primary problem behind the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean was the fact that they had still been employed by the Foreign Office at the time, not that their employer had been derelict in failing to prevent their escape. Extraordinarily, one or two stories in the Press were overlooked. On June 8, 1952, the Sunday Pictorial published a column that claimed that Maclean had known that he was under surveillance, that he had been suspected of being a Soviet spy, and that Burgess had helped his escape by hiring a car. Lady Maclean (Donald’s mother) brought it to the attention of the Foreign Office, asserting that it was libellous. But nothing happened. And the period of what the Daily Express called the ‘Four Years’ Silence’ continued.

By 1955, however, the Foreign Office was forced to make an announcement in the wake of the defection of Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov in Australia, and it was only then that the concept of a ‘third man’ (a ‘tipoff man’) took root. The Petrovs had defected in April 1954, in very dramatic circumstances, and Vladimir had immediately begun to talk – both to the press, and in a series of debriefings carried out by the ASIO (Australia Security Intelligence Organisation) officer G. R. Richards. Edward Heath, nine years later, took the opportunity to remind his listeners of the circumstances of that time, trying to convoy the notion of a ‘third man’ through the potential minefield. He explicitly confirmed the substance of such an entity, but he felt confident enough to discount any possibility that Philby might have been suspected of filling that role:

Both Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, when he was Foreign Minister, and former Prime Minister Sir Anthony Eden, now the Earl of Avon, had told the House in 1955 there was no reason to suspect Philby had been the tipoff man in the Burgess and Maclean case.

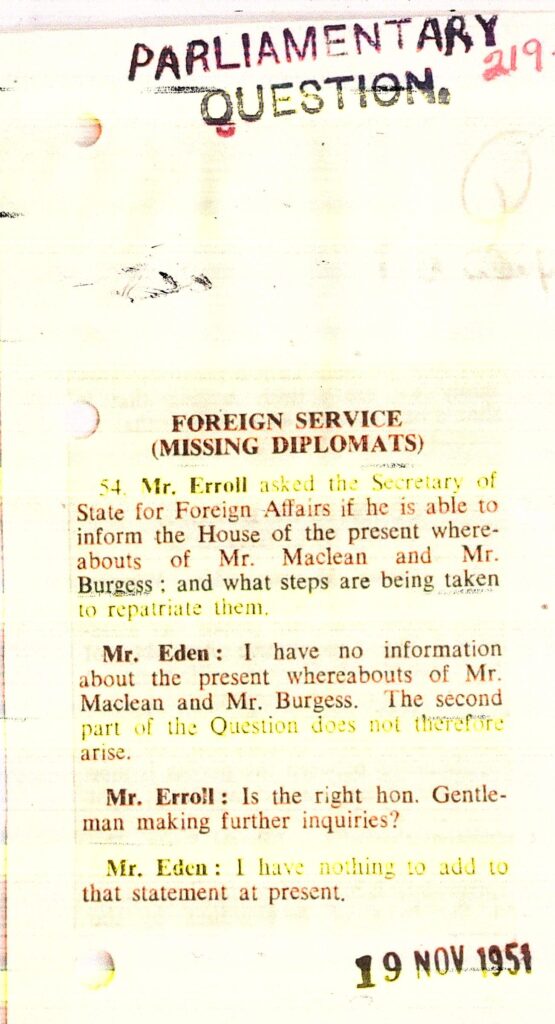

Heath did not explain to his audience exactly what Macmillan and Eden had been told at the time by their intelligence chiefs, or how such guidance contributed to their confident judgments. They probably did not have a clue: the FBI and the CIA knew more about the case than the leading members of the UK government. For example, after the Conservatives won the November 1951 election, Prime Minister Churchill and Foreign Secretary Eden were, according to Foreign Office mandarins, told the ‘full story’, namely that Maclean had come under suspicion because of his mental breakdown in Cairo. Eden gave a peremptory answer to a parliamentary question, namely that he had no knowledge of the ‘present whereabouts’ of Mr. Burgess and Mr. Maclean. I doubt whether Eden, if pressed, could have explained the circumstances of the ‘tipoff man’. So where and when did the ‘Third Man’ story originate?

The Third Man

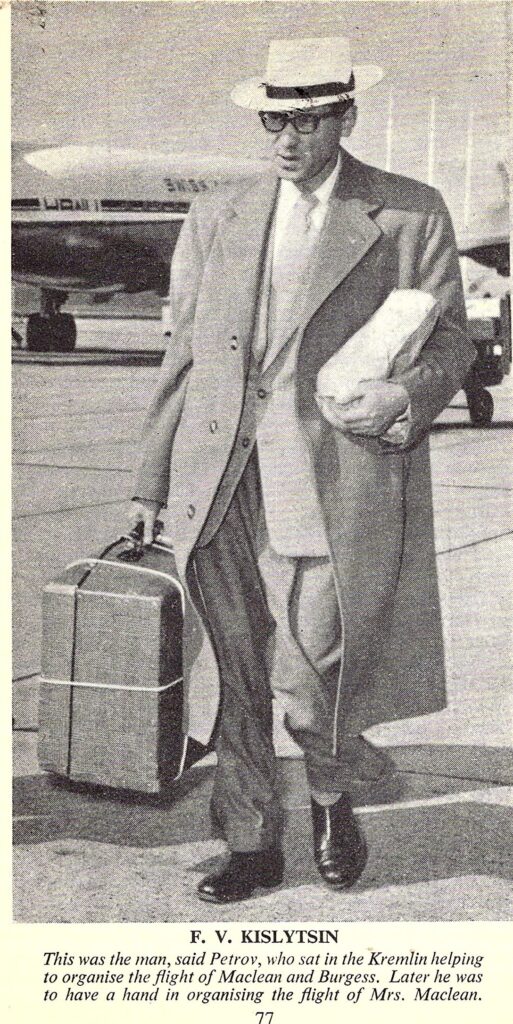

One prominent source appeared in a book that traded on the concept. In his 1967 volume profiling Philby, The Third Man (a title to which the author does not really perform justice), E. H. Cookridge – an Austrian-born journalist who had known Philby well in Vienna in 1934 – described how the Australian Royal Commission on Espionage, on September 18, 1955, had delivered its report on the discoveries made by the revelations of the Petrovs. According to Cookridge, the report contained Petrov’s deposition that Burgess and Maclean had supplied the Soviets with a rich trove of photographs and other documents from the Foreign Office. Vladimir Petrov stated that he had learned these facts from a cypher clerk who worked for him in the Canberra rezidentura from October 1952, one Filip Kislitsin, who had provided operational support to Burgess and Maclean when he worked in London during the late 1940s, and had later, in Moscow, helped organize their exfiltration from London. Kislitsin was proud of his performance in this case and boasted that it had gone off ‘exactly as we had planned’. When the news of Melinda Maclean’s successful break-out to join her husband in Moscow was published in 1953, Kislitsin had been prompted to tell Petrov what he knew about the Burgess-Maclean business, and Petrov had skillfully elicited further information from him.

Cookridge then made a startling claim, introducing a new actor on the scene:

Also in Petrov’s deposition was the statement that Kislitsin had told him that a ‘third man’ in Washington had informed Colonel Vassilyi Raina, head of the First Directorate of G. U. R., that Maclean was under investigation and there was a danger that he might be arrested. This ‘third man’ had apparently warned Maclean by sending a friend to London. Kislitsin was obviously unaware that the emissary was Burgess; neither did he know the name of the ‘third man’ in Washington.

Note that this claim carefully points to the tipoff occurring while Burgess was still in the USA: it is a general warning about the investigation, not an alert about an imminent arrest. It suggests that Philby was, improbably, in direct contact with Raina. It also provocatively implies that Raina and his organization did not have the means to contact Maclean directly, and that the Soviets had had to rely on Philby to provide the alert by very circuitous means. In any case, if this assertion by Cookridge were true, it pointed to a shocking oversight by MI5 and the Foreign Office. Had a direct pointer to a person undeniably identifiable as Philby been made public as early as September 1955? The British authorities had appeared ignorant of this disclosure by Petrov (or had believed that they could safely repress it), as they published, on September 23, a notorious statement on the defections that took no account of the assertion, in the form of a White Paper titled ‘Report Concerning the Disappearance of Two Former Foreign Office Officials’. How could they have ignored the statement to which Cookridge referred?

It seems that the Foreign Office had been waiting for the dust to settle in Australia before delivering the paper, but it had also been pushed into activity when an item about Burgess and Maclean that had been published in the Australian press appeared in an article in The People on September 18. It was an extract from the Petrovs’ ghost-written and as yet unpublished memoir Empire of Fear. Rebecca West wrote that an enterprising journalist called the Foreign Office for comments, fully expecting to get rebuffed, but instead received confirmation of all the basic facts about the pair and their escape, including the critical one that they had left because they knew that they [sic!] were being investigated. Two cats were out of the bag.

The Government’s White Paper did contain two important paragraphs concerning the defections, however. Paragraph 11 read:

It is now clear that in spite of the precautions taken by the authorities Maclean must have become aware, at some time before his disappearance, that he was under investigation. One explanation may be that he observed that he was no longer receiving certain types of secret papers. It is also possible that he detected that he was under observation. Or he may have been warned. Searching enquiries involving individual interrogations were made into this last possibility. Insufficient evidence was obtainable to form a definite conclusion or to warrant prosecution.

The suggestion of a tip-off man was very tentative, and was restricted to the possibility that Maclean had been warned of the investigation ‘some time before his disappearance’. Nevertheless, the end of paragraph 26 ran as follows:

It was for these reasons necessary for the security authorities to embark upon the difficult and delicate investigation of Maclean, taking into full account the risk that he would be alerted. In the event he was alerted and fled the country together with Burgess.

The tone has changed: the notion of a tip-off man is firm. Yet this is a different dimension: it suggests that the tip-off occurred at the last minute, and that it probably provoked the flight. It shows confidence that Maclean had been alerted – yet how did the security authorities know that for sure? I do not believe the scandalous implications of this second statement have ever been analyzed closely. The government made an explicit admission that it knew that Maclean had been alerted, but never stated what the evidence was, or why such evidence did not lead to the source. It also did not explain how the authorities thought Maclean might have been alerted: were their own security procedures so frail, or did they suspect that Maclean had conspirators in high office? It was also ingenuously vague and incongruous about the circumstances: ‘embark[ing] upon the difficult and delicate investigation’ suggested an extended process that in fact went back several months, while the description of the alert, and Maclean’s subsequent flight, indicated a more sudden event. This assertion had another very important implication: by indicating that the twosome had been able to make a quick decision to abscond, it finessed the whole question of the need for a Soviet logistics effort to enable their passage to Moscow once they reached France.

The extent of the confusion – or self-deception – can be shown by other archival sources. The Foreign Office file FCO 158/133, a heavily redacted 1955 report claiming to analyze the possible penetration of the Foreign Office by Soviet agents includes the following passage:

The suggestion that Maclean (or Burgess) may have been ‘tipped off’ by someone in the Foreign Office proper or in the Foreign Service overseas has been exhaustively examined. While a deliberate warning cannot be entirely ruled out, or an inadvertent and innocent ‘tip-off’ conceivably given in London to Maclean, it has been concluded that the disappearance of the two men, at that particular time, can be explained quite independently of any warning.

So much for the White Paper confirmation that Maclean indeed ‘was alerted’. Maybe the report was simply trying to exculpate the Foreign Office, and detach it from MI5’s rather shabby account. Yet leaks in the Foreign Office had indeed been recognized early on. As recorded in KV 2/4104, Malcolm Cummings in B4 of MI5 had on June 12, 1951 described ‘slipshod security’ at the Foreign Office. A member of the cypher staff there had informed MI5 that a large number of people at the Foreign Office were aware of the investigation into Burgess and Maclean. There was little evidence of the ‘exhaustive’ examination claimed by the anonymous official, in that case. A simpler admission of this fact could have saved the Government a lot of grief.

Moreover, other contradictions were obvious. Another internal Foreign Office memorandum, by Arthur de la Mare, dated November 7, 1955 (see FCO 158/177), recorded that members of the Press had noticed that the White Paper told how ‘Maclean and Burgess made their escape when the Security Authorities were on their [sic] track’, when elsewhere the Report had stated that Burgess had not been under suspicion. De la Mare tried to explain away the contradiction by saying that the impression was given by the account of Petrov’s testimony in paragraph 23, but it was not a convincing defence. Foreign Office high-ups were aware of the contradictions.

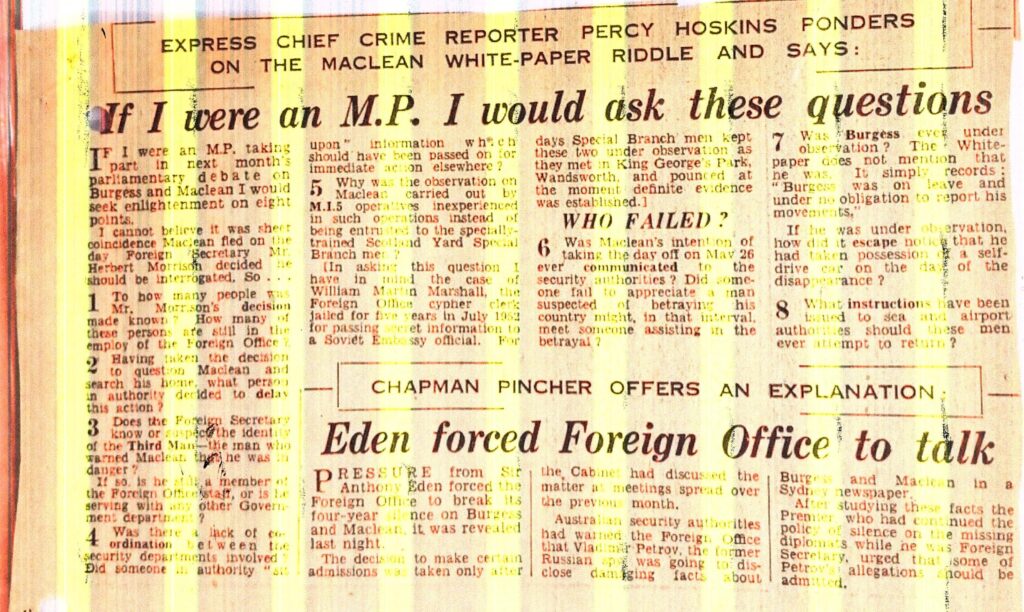

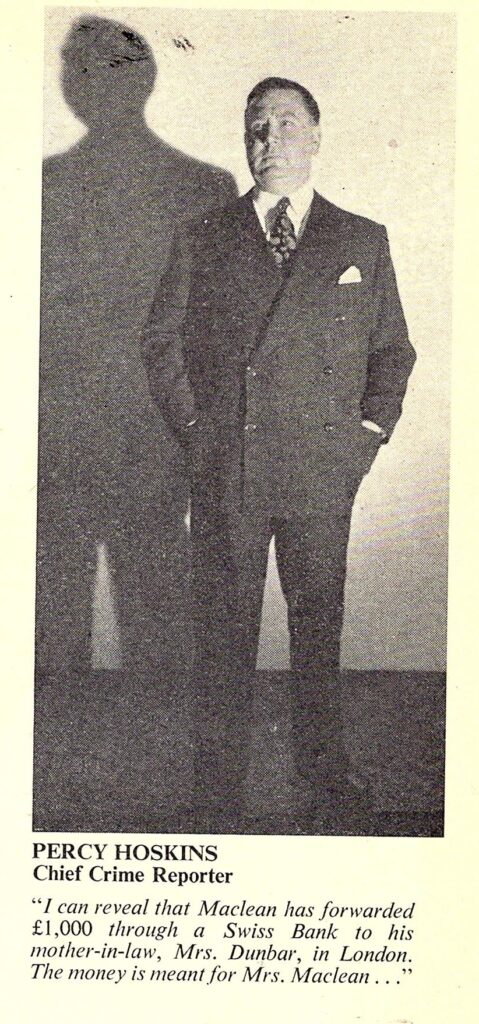

The British Press immediately picked up on that critical phrase: ‘he was alerted’, and the concept of the Third Man thus took root – in September 1955. Yet the journalists overall did not cover themselves with glory over these ambiguous signals. Percy Hoskins of the Daily Express tried valiantly to energize the discussion, and in one column listed ‘eight points’ – questions he believed MPs should be asking in the forthcoming parliamentary debate, which astutely highlighted some of the anomalies in the White Paper. He drew attention to such embarrassing items as Maclean’s taking the day off on May 26, without any indication of concern by his bosses. (The column can be seen at sn.502 in FCO 158/7.) The Foreign Office was alarmed enough over the adverse criticism it received in the Press to create a tabulation of the questions raised: this in itself could have acted as a comprehensive assault on the flimsiness of the case presented. At the end of September, the Foreign Office was preparing some tentative responses that Prime Minister might be able to deploy when the inevitable Commons debate took place. Yet, perhaps because the media were so fragmented and competitive, no concerted challenge evolved. Members of Parliament were either distracted, confused, or cowed into silence, and presented no substantive confrontation.

As an example of how scattered and random the criticisms were, in one of the reflective pieces which Hoskins supplied between the issuance of the White Paper and the debate in the House of Commons, he raised again the subject of the tip-off man. wrote: “It has been assumed that he [Burgess] had been tipped off by a contact in Washington or London, that he had hired the car to flee . . .”. (Note that it is now Burgess, not Maclean, who has been tipped off: Hoskins had sharply pointed out that it was absurd to consider that Burgess should have been able to escape after renting a car on the day of his disappearance, but the lead was not pursued.) Who had made that assumption is not stated: Hoskins was no doubt using an insider source who had given him the hint concerning an informant in Washington. *

[* An intriguing entry in Guy Burgess’s file KV 2/4104, at sn. 203z, dated June 25, 1951, declares, based on evidence from Judy Cowell: “The leakage to the Daily Express occurred in Percy Hoskins’ bar – his flat, at Arlington Court, is a rendezvous for civil servants, police officers and officers of the Security Service.”]

There appears to be no paper-trail of these fragmented revelations, although they obviously came to the notice of Cookridge as well. My first reaction was that any relevant records that emanated from Australia must have been weeded by MI5, and that a disgruntled insider had passed them on to Cookridge. I had to remind myself that, back in April 2109, I had concluded that Guy Liddell had been Cookridge’s informant: see the second section of my posting at https://coldspur.com/the-importance-of-chronology-with-special-reference-to-liddell-philby/. Liddell had resigned from MI5 in May 1953, so would not have officially been exposed to the Petrov business at close hand. The Petrov files, however, show that he visited Australia, with the knowledge of ASIO, in the autumn of 1954, returning after a satisfactory visit in November. He may well have been on an undercover assignment to gather information on Director-General White’s behalf. He certainly had an interest in diverting attention away from Blunt to Philby, which this ‘extract’ undeniably does. Thus he might have continued to feed information to Cookridge, while Cookridge may have added the flamboyant flourish himself.

Yet Hoskins, who acted as the doyen of the journalists, never asked himself: How could a Third Man in Washington have given a last-minute tip off? Hoskins never re-assembled the dual dimensions of leakage that had explicitly been stated in the White Paper, and instead he applied the secret intelligence he possessed solely to the phenomenon of the last-minute alarm. Marcus Lipton’s question to Prime Minister Eden had similarly failed to grasp the nettle, since he concentrated on the ‘Third Man’ activities of Harold Philby, when it was well-known that Philby returned to Britain after Burgess and Maclean had disappeared. An opportunity was missed: any properly focussed attention was probably distracted by an event across the Atlantic.

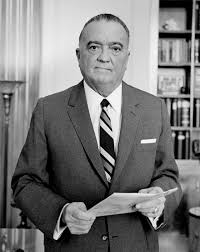

Hoover Intrudes: The Commons Debate

It would appear that the information described by Cookridge had slipped out already – even to the USA. J. Edgar Hoover, the F.B.I. chief, who had, as I have explained elsewhere, been tipped off by Dick White, via Arthur Martin, in June 1951 as to Philby’s role as the ‘alerter’ in Washington, entered the fray. (Please see the following bulletins for the full story: https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-devilish-plot/ and https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-tangled-web/ ). At that time, White’s logic had been as follows: Philby was already under suspicion; he was indoctrinated into the HOMER inquiry; his close friend, Burgess, stayed at his house outside Washington; Burgess returned to the UK, and consorted with Maclean; Burgess and Maclean absconded. Thus Philby was responsible. Instead of having to battle with Philby’s employers and allies at MI6, why should White not induce the Americans to force the issue, and have him outed? White’s scheme had been received enthusiastically by Geoffrey Patterson, the MI5 representative in Washington. In fact, Philby had been recalled before the Americans took action.

When the Petrov story broke, Hoover pursued his own investigation, however. According to David Horner’s Official History of ASIO: 1949-1963, in August 1954 Hoover ‘arranged for an FBI liaison officer to visit Spry in Melbourne’, which led to more solid relations between the two agencies. Horner continued (p 380):

Hoover then wrote directly to Spry asking for various pieces of information from the Petrovs. The information was cross-checked against that provided by the Soviet defector Rastvorov in the United States, and both ASIO and the Americans were satisfied that Petrov’s evidence was reliable.

Rastvorov had defected in Japan in February 1954, after receiving a recall instruction in the wake of the purge of Beria’s men. Horner’s attention to detail is regrettably lax, however. His source for this item is an unidentified ASIO memorandum dated July 9, 1974: the chronology does not make sense. What Rastvorov claimed about Burgess and Maclean is thus not easily verifiable. (Rastvorov contributed three articles to Life magazine at the end of 1954, but they contain only a cursory reference to Burgess and Maclean.)

White’s little game with the FBI was a dangerous one: he was suffering from delusions of grandeur. His behaviour in 1951 and 1952 had been one of the most disreputable aspects of the whole affair. He had for a long time believed that he was running the whole show at MI5, and he had given that impression to others. In a diary entry for January 28, 1948, Malcolm Muggeridge, having just lunched with White, wrote: “He is now more or less head of MI5”. Sillitoe was just a figurehead, and Deputy Director-General Liddell had been carefully sidelined. Having executed his ruse of leaking his strong suspicions about Philby to the FBI via Arthur Martin’s dossier, White then had to face the prospect of having Philby interrogated when the latter was recalled in June 1951, and he took on the responsibility himself. He was, however, mentally, psychologically, and technically unprepared for this task, as the transcripts in the PEACH files show. He had probably expected that the reaction from the United States would have eliminated Philby by then – or even pushed him to defect, too.

Yet, having failed at his task, and with MI6’s senior officers rallying to Philby’s support, White had to delude his own team about the implications of the man’s guilt. In an extraordinary minute recording a meeting of MI5’s B2 team (Soviet counter-espionage) held in February 1952 (see sn. 387z in KV 2/4108), White explained to the officers present that, after Helenus Milmo’s interrogation of Philby in December 1951, he was known to be a Soviet agent and was deemed responsible for the leakage of information that led to the flight of Burgess and Maclean. White warned everyone in attendance that no mention of the case could be made to anyone not present. If the information became public, he explained, serious damage to MI5’s relations with the US security authorities might occur. B1 and B4 also received the lecture. Guy Liddell apparently did not get the message. It was a hypocritical and deceitful show of behaviour of the lowest order on White’s part. There would be many who would recall White’s recklessness in the years to come.

In any event, Hoover ordered a story to be leaked to the New York Sunday News, in which Philby was named as the ‘Third Man’. It appeared on October 23, 1955. The timing was extraordinary, since Hoover’s insertion simply caused all the attention in the UK to shift from the several relevant questions about the whole surveillance project to the more volatile and eye-catching theme of the tip-off man. (Might the story’s release and timing have been arranged behind the scenes? I do not regard it as impossible.) The disclosure encouraged the terrier-like but not outstandingly smart Marcus Lipton, at Prime Minister’s Question Time in the House of Commons on October 25, to shift his focus. He requested that a Select Committee be appointed to investigate the Burgess and Maclean business, and he followed up with the following question:

Has the Prime Minister made up his mind to cover up at all costs the dubious third man activities of Mr Harold Philby, who was First Secretary at the Washington embassy a little time ago, and is he determined to stifle all discussion on the very great matters which were evaded in the wretched White paper, which is an insult to the intelligence of the country?

It appeared that Lipton was brazenly, but confidently, using Hoover’s leak to exploit intelligence that could only have derived from the debriefing of the Petrovs – information that he had acquired clandestinely. Anthony Eden’s reply, however, was to fence off the whole matter:

My answer was “No” to the hon. and gallant Member’s Question, which was not about all that but asked for the appointment of a Select Committee. My answer remains “No.” So far as the wider issues raised in the supplementary question are concerned, the Government take the view that it is desirable to have a debate, and an early debate, on this subject, in which I as Prime Minister will be glad to take part.

The outcome was that a further debate did indeed take place, on November 7. Foreign Secretary Harold Macmillan’s long exculpatory speech can be seen at https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/1955-11-07/debates/45728b3c-a5e0-48ac-829f-a47d00fec839/FormerForeignOfficeOfficials(Disappearance) . On Philby, he made the following statement:

It is now known that Mr. Philby had Communist associates during and after his university days. In view of the circumstances, he was asked, in July, 1951, to resign from the Foreign Service. Since that date his case has been the subject of close investigation. No evidence has been found to show that he was responsible for warning Burgess or Maclean. While in Government service he carried out his duties ably and conscientiously. I have no reason to conclude that Mr. Philby has at any time betrayed the interests of this country, or to identify him with the so-called “third man,” if, indeed, there was one.

While the charge of having ‘had communist associates’ sounded a feeble reason for suspension (of how many leading members of various government administrations might that have been said?), it was allowed to pass. If that was all that Philby had been accused of, he could have borne justifiable grievances about his peremptory dismissal. (When one considers how Burgess and Maclean were kept on and sustained after their reprehensible patterns of behaviour, it is almost comical.) Also allowed to pass was Macmillan’s naïve but very characteristic questioning of the existence of a ‘Third Man’, even though the earlier government report had admitted that Maclean had indeed received a warning from someone of presumably humanoid origins. Moreover, the outcome of Macmillan’s clearance of Philby, the virtuoso performance to the Press by Philby at his mother’s home, and his subsequent challenge to Lipton to repeat his accusation outside the protection of the House of Commons, meant that Lipton had to make an abject apology. If Philby had been courageous, he might have declared that it was impossible that he could been the Third Man who gave the last-minute tip-off, since he was over 3,500 miles away from the action at the time. Yet he might thereby have rekindled the idea of an unidentified Third Man in Washington who much earlier had alerted Maclean to the investigation, and he thus could also have turned the spotlight afresh on someone else, the last-minute informant in London.

Yet how was it that the statements issued in the House, and the White Paper issued on September 23, could so glibly avoid the revelation that Cookridge later identified? And why did Lipton have to withdraw his remarks, if the evidence was so unambiguous? The Government had admitted that there had been a ‘Third Man’, but happily went along with Philby’s resolute denial that it had been he. In that case, however, the real Third Man was still at large. A more dogged approach by the Press and the Members of Parliament should have pushed the Government to explain why their investigations had failed to unearth who the true culprit was, and it could have applied pressure for it to explain the paradox about warnings from Washington and leaks in London.

The fact is, however, that in one critical respect Cookridge was completely wrong about the Washington-based alert. No such statement concerning a ‘Third Man’ had ever been published in the Australian proceedings. The Final Report of the Royal Commission on Espionage has no indexed entries for Burgess or Maclean, and the detailed transcripts of the Commission’s inquiries that lasted for one-hundred-and-twenty-six days, dating from May 1955, contain no testimony from the Petrovs that referred to the fact that Burgess and Maclean may have received a tip-off before they escaped. All the relevant information was concealed in secret exchanges between ASIO and MI5 in London. No doubt Cookridge, Lipton and Hoover, and senior members of the CIA’s counter-intelligence staff, all received the same damaging item from an insider source, but were constrained by the ethics of source protection. Thus the story died for a while, and the Foreign Office breathed again. The clandestine proceedings of the handling of the Petrovs were to reveal, however, that MI5 and the Foreign Office were in 1954 and early 1955 trying to protect some very dark but related secrets.

The vital aspect of the two paragraphs in the White Paper is the fact that they implicitly pointed to the possible existence of a Third Man as well as that of a Fourth Man, two separate persons giving warnings at different stages of the investigation! And this was, of course, precisely true, namely Philby (stage 1) and Blunt (stage 2). Dick White and his subordinate officer Graham Mitchell (head of D Division), responsible for the text of the White Paper, surely never considered that the wording of their statement might have given the whole game away. Neither the honourable members of Parliament nor the less honourable members of the Press could possibly imagine that there were two tip-off men involved, and they failed to pick up the obvious but probably unintended clues that had been thrown to them.

Where was the accountability? For four years, the British authorities had pretended there had been no exposure or malfeasance, but were then forced to acknowledge that the pair had indeed been spies, and that Maclean (at least) had been tipped off. They then forcefully denied that Philby had been the Third Man who had alerted the pair, and they defended him. Another eight years were apparently spent doing nothing – until Philby’s disappearance forced them to admit that he had indeed been that individual. In attempting to explain their dismal performance over the whole imbroglio, however, the Foreign Office and MI5 had opened a Pandora’s box of puzzles and conundrums that has never been closed. What exactly did the defection of the Petrovs uncover, and why were the disclosures not followed up with any vigour?

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Petrov Files: The Defection

The National Archives files on Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov are gigantic. They encompass KV 2/4339 to KV 2/4388 – fifty discrete files. Most of these, for reasons of size, are split into further sub-files, numbering from two, three, four, five – even to eight in one case. Most of these sub-files contain a hundred pages or so. They are a mess. The transcripts of the hearings (KV 2/3478 to KV 2/3487), comprising the full record, over one-hundred-and-twenty-six days, and consisting of photocopies of densely-typed pages, should have been extracted into a separate file, alongside the relatively brief official ‘Report of the Royal Commission on Espionage’, dated 22 August 1955, at KV 2/3488. The remaining files are a largely disorganized accumulation of memoranda, reports, telegrams, interviews, etc. etc. dealing with the investigations into the Petrovs, the attempts by London (the Foreign Office, the Ministry of Defence, MI5 and MI6) to control what was going on, and the arduous role of MI5’s Service Liaison Officer with ASIO in Canberra to act as a mediator.

There are many highly valuable items in the archive, such as fascinating reports on the structure and methods of Soviet Intelligence, and profiles of its agents abroad in many countries, but they are interspersed with much repetitive information, and a rather chaotic set of correspondence. Moreover, the files have been weeded and redacted. Since cable numbers were applied serially, the existence of missing items is obvious by virtue of the discontinuity of identifiers. Several items (including a few relating to Burgess and Maclean) that are listed in the Minute Sheets have been removed from the dossier. On the other hand, significant pieces concerning the pair are absent from the Petrov files, but can be found in the Burgess PF (in KV 2/4111). Names are frequently redacted. Memoranda are referred to, often as enclosures, but they are not attached. It is utterly chaotic – maybe deliberately so. Wading through these files is a laborious – but necessary – process.

Yet a careful examination reaps great rewards. To a small extent, the MI5 officers who studied them have helped researchers. They were on the lookout for references to Burgess and Maclean in the transcripts, and inserted their hand-written notes where information needed to be extracted to the defectors’ files. Thus, when the examiner is trying to pinpoint the date when Kislitsyn (aka Kislitsin) arrived, in KV 2/3485 (Day 93, February 2, 1955), Evdokia Petrov helps the investigator by indicating when the news was received that Melinda Maclean had made her escape. At the top of the first page of the Transcript for each day, the MI5 officer has carefully listed all the Personal Files that need to be updated with relevant information from the record, and the officer responsible (R. T. Reed, a name that will be familiar to many coldspur-readers) has faithfully listed Maclean (D.D. – to distinguish him from an unrelated Australian Maclean) and Burgess for processing with items on page 2002. Thus, if Reed and his colleagues were doing their job properly, we should be able to rely on them for a comprehensive collection of Burgess and Maclean sightings. The gems derive from the mass of other material.

This was not a normal, clandestine defection. Vladimir Petrov had been under close inspection ever since he arrived in Australia, and ASIO had marked him out as a potential defector in July 1953. While Petrov had been discreet in his negotiations, he had not been open with his wife, Evdokia, who worked alongside him as his cypher clerk. She was torn between loyalty to her husband and her concern for relatives left behind in the Soviet Union, and she actually defected two weeks after Vladimir. A very public attempt at abduction of Evdokia by KGB goons was caught on camera, and the world’s press was alerted to a major story. Vladimir was interested in milking the highest bidder to pay him for what he knew, and the Australian government knew that it could not keep him quiet. Petrov brought very little documentary evidence of espionage with him, however: most was in the heads of him and his wife.

There was also much political controversy, since an election was to take place on May 29. The incumbent Prime Minister, and leader of the Liberal/Country Coalition, Robert Menzies, had feared a strong challenge by dint of the free-spending promises of Dr. Evatt, the opposition Labour leader. When Menzies won the election, Evatt, a communist sympathizer, claimed that Premier Menzies had arranged the defection for electoral purposes, and that the documents were fake. Tension existed between the fledgling ASIO (set up and trained by Roger Hollis) and the MI5 officers in London. ASIO wanted to show its independence in what it saw as an Australian affair, while the UK was concerned about the broader implications, and was already uneasy in its relationship with the Americans because of VENONA-related leakages in Australia. Indeed, VENONA cast a shadow over the whole proceedings, since many of the identifications of Soviet agents that the Petrovs were able to make could not be revealed in open court because of the secrecy behind the VENONA programme. Yet, owing to a coincidental acquaintance, the Petrovs had some fresh secrets to reveal about events way beyond Australia. They had insider information about the abscondment of the Missing Diplomats.

Burgess & Maclean

The fact that what the Petrovs had to say about the Burgess-Maclean business was based on second-hand evidence was of no concern to such as the Daily Express, but it was a critical concern for MI5 and the Foreign Office, who went to strenuous lengths to make sure that anything inflammatory was described as purely speculative. As early as April 7, 1954 (i.e. a couple of days after Petrov defected) the Security Liaison Officer (SLO) in Canberra, Derek Hamblen, summarized in a cable the major points Petrov had already revealed: that the NKVD had recruited Burgess and Maclean as students; that, when the pair considered they were under surveillance, the MGB ordered their retrieval; that the escape arrangements were handled by Kislitsyn; and that the spies had taken valuable information with them. MI5 was very concerned about the details behind these allegations, and it wanted to prevent any fresh bare facts from coming out.

The references to the university background of the recruitment of the pair might have provoked greater concern than was apparent. After all, if you find a couple of dead bats in your attic, it is unlikely that there are not many more who have decided to roost under your rafters. The public at large may not have thought twice about this phenomenon, but any MI5 officer who had been exposed to the Krivitsky disclosures should have reacted with alarm. If Burgess and Maclean, what about Philby, Blunt, Rothschild, for starters – and that was just Cambridge? White, Liddell, and Archer (especially) all knew about the Imperial Council spy and the journalist in Spain. Could the lid be kept on that part of the story?

One of the hitherto unspoken areas of interest must have been the implication that Burgess and Maclean contacted their Soviet handlers when they realized that they [sic!] were under surveillance: since the pair had been closely watched since Burgess’s arrival, and no contact with members of the residency had been noticed, who had been the messenger? This conundrum would not have been apparent to the outside world, but it was of critical importance for MI5. When the first report from Australia on Petrov’s testimony on Burgess and Maclean arrived in London on April 7, declaring that the Soviet Embassy had ordered their withdrawal after the couple had told them they were being surveilled, someone has inscribed: ‘How did they know?’. Indeed, Robertson immediately replied, in a message visible at sn. 519a in KV 2/4111, but which (I believe) is absent from the Petrovs’ PF: “Urgently interested to know why BURGESS and MACLEAN considered Security Service were on their track.”

[I insert here what I believe are important comments about the organization of MI5 at the time. In May 1953, Dick White had been appointed Director-General to replace Percy Sillitoe, much to the chagrin of the Deputy D-G Guy Liddell, who retired to work at AERE Harwell. White, who knew where the bodies were buried, and was determined not to let their whereabouts harm his career, set out to re-build MI5. In October 1953 he implemented his changes. Roger Hollis moved from C Division to become White’s deputy. Divisions now became Branches. F Branch was re-formed to intensify domestic surveillance of subversive movements. The Counter-Espionage B Division was reconstituted as D Branch: in what must have been a surprise move, the relatively inexperienced and untested Graham Mitchell (who had been responsible for ‘Vetting’ under Hollis in C3) was appointed head of D. Whether James Robertson, who had worked closely with White on counter-espionage projects such as the Blunt business in 1951, was miffed by this apparent snub, cannot be ascertained. Robertson (as head of D1, the Soviet counter-espionage section) continued to lead the Burgess/Maclean inquiries while his boss, malleable under his new protector, learned the ropes. The Petrov case immediately applied pressure on the somewhat unworldly Mitchell, while Robertson disappeared from D Branch records late in 1955 – perhaps because he was disgusted with the shape that the White Paper had taken – although he did resurface as ‘D’ in July 1956. That was the month in which Roger Hollis replaced White as Director-General, and Mitchell was moved into the deputy spot. Courtenay Young, who had served as Special Liaison Officer between ASIO and MI5 from 1952 to 1955, and also ghost-wrote Alexander Foote’s memoir Handbook for Spies, had joined D1 from B1k earlier in the year, but in June 1956 he reported that Rodney Reed had been taken away from him. Young was left to hold the fort on Burgess and Maclean himself as D1, until D. M. Whyte was moved in a couple of months later. Thus there were certainly continuity problems in D Branch, and probably some concerning morale, as well.]

Very curiously, moreover, the narrative takes two different courses at this point. The relevant Burgess Personal File (KV 2/4111) includes documents that are not to be found in the corresponding Petrov Files (KV 2/3440 and 2/3442). KV 2/411 shows that a contentious exchange of cables took place at the end of April 1954, in which Charles Spry, the head of ASIO, accused the Foreign Office of making unauthorized and unnecessary comments on confidential material. London, in response, suggested that leakages of information to the Press had occurred in Australia, and that it was a mistake for the Australian authorities to be arranging press conferences for the Petrovs. In fact, ASIO had to concede that a source close to Evatt had leaked information to the Press after a Cabinet meeting. The Burgess file does include a fuller attempt by the SLO to explain what Petrov knew and had said about the communications between Burgess and Maclean and the Embassy, but the defector’s story varied, possibly because of translation issues, and the Petrovs started to clam up as they did not want to say anything that might damage their ex-colleague, Kislitsyn.

Returning to the annotation of puzzlement above, I declare that this simple reaction has very deep implications. First of all, the author of the note was probably interested in knowing how the couple knew that they were being surveilled, but it could also refer to an explanation of how the Soviet Embassy learned of their suspicions. After all, if Burgess and Maclean were being closely surveilled, any contact with Embassy personnel would surely have been picked up. Yet there is a degree of naivety in the inquiry: since the surveillance of the duo was so very obvious (and maybe designed to frighten them into an indiscretion such as arranging a meeting with their Soviet handlers), why would Robertson appear to be so surprised that Burgess and Maclean had detected that they were being watched? Was he perhaps ignorant of the true nature and purpose of the surveillance exercise? This would not be the only occasion when aspects of the project were being withheld from lower-level MI5 officers. It seems that Petrov had assumed that the pair had been alerted rather than working it out themselves, but he may have been fed a leading question.

The response could have been very provocative, and a little troubling, but it is not clear that Robertson’s question was directly addressed. An item in the ‘Kislitsyn’ file maintained by ASIO (Volume 3: A6119, p 17), recording an interrogation of Petrov that took place on April 13, confirms the evidence: “According to GLEB [Kislitsyn] they [Burgess and Maclean] reported to the contact man that they were fairly certain that Security were taking an unusual interest in their activities. Sometime later the Soviet arranged their escape.” A ‘contact man’, eh? Who might that be? I could not find this nugget in the KV Petrov files. And MI5’s Watchers had not noticed any meetings between Burgess or Maclean and members of the Soviet Embassy. Yet Anthony Blunt had been in plain sight. Was there a possible exposure here?

MI5 Reacts

In any event, MI5 jumped into action – before the date of the above ASIO minute. It expressed great interest in trying to persuade Kislitsyn to defect, too, as a cable from Robertson, sent as early as April 9, reveals. ‘Prepared to go to any reasonable limit financially’, he adds. This was assuredly because the KGB officer might have been able to shed light on how the London residency learned of the investigation into Maclean. MI5 had its suspicions of Blunt’s disloyalty by then, of course (with White wanting to give him immunity for a full confession back in the summer of 1951), but the Security Service had apparently not seriously considered that he had acted as an emissary between the Missing Diplomats and the MGB. Information from an insider might give them vital information. However, as with Petrov, it was a two-edged-sword. If Kislitsyn were to defect, and start talking casually to the Press, MI5 and the Foreign Office would lose control of the process, and embarrassing stories might emerge. As it happened, Kislitsyn, who witnessed Yevdokia’s struggles at Darwin airport, accused the Australians of trying to kidnap her, and coolly continued on his route to Moscow. Moreover, the chief of ASIO, Charles Spry, had enough defectors on his hands: he did now want to have to deal with Kislitsyn as well. *

[* Astonishingly, when questioned by the panel at the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security, in February 1976, Spry twice referred to Kislitysn as ‘probably one of the most important defectors ever to defect from the Soviet Union’. It is clear from the context, however, that he was referring to Anatole Golitsyn, and that the stenographer mis-recorded the name. The error was never noticed, and the document never corrected. In such a manner do mistakes in chronicles occur, and erroneous history is written.]

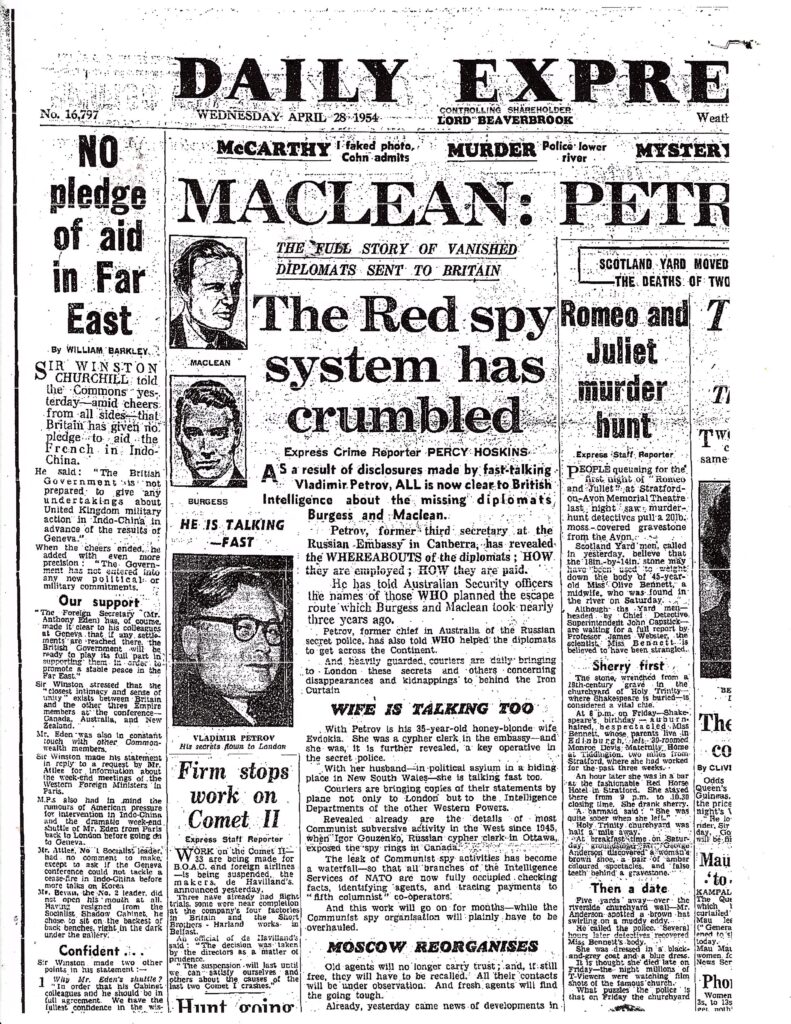

After Evdokia made her choice, the Petrovs were made available for press questions as early as a couple of weeks after Menzies’ announcement of April 13 that an official inquiry into Soviet espionage would take place. By the end of the month, MI5 was urgently requesting full details of exactly what the couple had already said. The local Daily Express stringer, Morley Richards, was feeding information to Percy Hoskins in London, and the newspaper started to publish stories. An alarming article appeared in the Daily Mirror (Sydney) on April 28, 1954, citing a column in the Daily Express from the same day, in which Petrov was claimed to have told reporters who planned the escape of Burgess and Maclean from Britain, and who helped them across the Continent. It is probably safe to assume that messages on this topic were being exchanged between MI5 and the SLO about this article, but any record of such has been weeded out from the files.

In his Soviet Defectors (pp 244-245), Kevin Riehle in an Endnote explicitly highlights this Daily Express article for the revelations of Petrov (whom he identifies as ‘Shorokhov’), and he provides the headline ‘Maclean: Petrov Tells: The Full Story of Vanished Diplomats Sent to Britain’. I have tracked the article down [see image introducing this report]. It is unremarkable – more titillating than revelatory. It dramatically indicated that the authorities now knew who had arranged the escape, and where Burgess and Maclean were now resident, questions that may have been of great interest at the time, but it did not describe exactly what the Petrovs had disclosed.

Nevertheless, MI5 was alarmed, and thus requested, on April 29, further details on exactly what Petrov had divulged, and from whom he had gained the information. MI5 pleaded that ‘nothing the Petrovs say (especially regarding Burgess and Maclean) is made available for publication except after consultation with us’. Perhaps in recognition that this was a futile request, MI5 then changed tack, starting to emphasize that the testimony of the Petrovs was based on second-hand (or even third-hand) evidence, and was thus only ‘hearsay’. That line was adopted when questions were asked in the House of Commons on May 3, to which Selwyn Lloyd replied that ‘such information about Burgess and Maclean which had so far been elicited was of limited and general character and it was not known whether it was based on Petrov’s personal knowledge or hearsay’. For several months, this strategy seemed to work. By July, however, fresh alarm bells began to ring, as Foreign Office and MI5 sensitivity to scrutiny came under intense media pressure, probably fuelled by MI5 insiders dissatisfied with the cover-up.

The greatest concern for MI5 and the Foreign Office was the possibility of stories appearing in the press about i) the claim (much later referred to by Cookridge) that there had been a British officer in Washington who had managed to communicate an early warning to Maclean about the investigation, and ii) the notion that the local Soviet residency had instigated the exfiltration, based on knowledge acquired clandestinely, rather than responding solely to the beliefs expressed to them by Burgess and Maclean that they were under surveillance. (Yet even that theory had its dangers, as I suggested above, and shall later explain.) The exposure of these tales would have been disastrous: it would have confirmed all the accusations against Philby, and unveiled his associations with Burgess, and it would have also strongly reinforced the idea that the Soviets were receiving regular updates on the situation from a friendly source in London as well. There is no evidence, in April 1954, that a specific reference to a Washington link in the chain had been revealed to ASIO and MI5 by the Petrovs. But matters were to become a bit messier.

Further Entanglements

A further shock must have been an item published in the Brisbane Sunday Mail, on May 23, when another Soviet defector, Nikolai Khokhlov, appeared on the scene. Rather dramatically titled ‘The Burgess-Maclean Mystery Is Solved’, the short piece concentrated on the escape of Melinda Maclean and her children that had been facilitated by the KGB, but it also stated that Khokhlov had provided an accurate story to his US debriefers of how Burgess and Maclean ‘slipped behind the Iron Curtain’. Khokhlov had been on a mission to assassinate the Russian opposition activist Okolovich earlier in 1954, but had felt horror at the last minute, admitted his role to his would-be victim, and then defected to the Americans in Germany on February 19, 1954. The CIA gave him a thorough debriefing. How the news filtered through to Brisbane, but apparently nowhere else, is puzzling. Yet, since ASIO picked up the story, and has a clipping in its files, the information presumably went to London, too.

More information followed. On June 30 (see KV 2/3456, sn. 79a), the SLO reported that Petrov had provided additional information about the set-up in London, with Chichaev (the NKVD representative to SOE) named as playing an important role in the escape. Petrov also described the size of the MGB cadre in London at the time. And on July 14, the SLO provided, by cable, identified as Y.262, a very focused, single item of information gained from the interrogation of the Petrovs (see KV 2/3457, sn. 91b). The item was troubling, and its essence contained the following sentences:

RAZIN informed P. it would be very useful if they could secure agent inside Swedish Service who might be able to tip them off about surveillance and other counter espionage measures against N.K.G.B. RAZIN said (?they had) such a man in London who worked in British counter-intelligence and passed on valuable information to N.K.G.B. about British counter measures. RAZIN gave P. NO other information.

It concluded by stating that the report would follow by diplomatic bag.

The full report contained several additional items, and it was indeed sent by diplomatic bag the same day. (It appears at sn. 101z in KV 2/3457.) These ancillary statements were not so shocking: they simply add background as to the means whereby Razin might have learned the information. For the record, I present the slightly fuller text that appeared as the first item in this Report (‘RAZIN’s reference to an Agent in the U.K.’)

While RAZIN was the N.K.G.B. Chief Legal Resident in Sweden (i.e. 1944-1945/6), he told PETROV (who was his N.K.G.B. cypher clerk) that it would be very useful if they could secure an agent inside the Swedish Counter-Intelligence Service who might be able to tip them off about surveillance and other counter-measures practised against the N.K.G.B. RAZIN added that they possessed just such a man in London who worked in the British Counter-Intelligence Service, and passed on valuable information to the N.K.G.B relating to British measures. RAZIN gave no further details.

The Foreign Office was alarmed. That it was embarrassed by what it knew, and that it was executing a cover-up, was indiscreetly recorded as early as November 1954, in an attempt to forestall what might emanate from the Petrov disclosures. A memo from A. J. de la Mare, freshly appointed as Chief Security Officer in the Foreign Office, to his boss, Sir Patrick Dean, appears in FCO 158/198, where he writes, on November 4: “The Security Service tell me that elaborate precautions are being taken in Australia to ensure that the proceedings of the Royal Commission will not disclose the source which revealed the treachery of these two men.” Apart from the clumsy phrasing (to whom was the ‘treachery’ revealed? or was the discovered treachery simply an accidental outcome of the source’s actions?), the implication is clearly that the identity of the source was known.

Officials continued to give the game away. A few months later, in March 1955, as work on the Petrovs’ book, ghost-written by ASIO officer Michael Thwaites, was under way, Graham Mitchell, the head of D Branch, made an extraordinary reference to the exchange from that previous July. His telegram is significant, and it deserves to be quoted in full:

- Foreign Secretary, after consultation with Cabinet colleagues, has decided to make no B and M comment.

- This decision reached in full awareness that PETROV will give publicity to story in due course and that this could happen at any time.

- Generally recognized here that events in Australia must be allowed to take their course. On behalf of F. O. and ourselves we express only the following wishes:

- The longer publication delayed the better;

- Assumption in paragraph 1 of our DS/2066 of 22.2.55, on which you gave welcome assurance in paragraph 1 of your Y.79 of 4.3.55, repeated with emphasis;

- As example of specially embarrassing matter which we hope will in no circumstances be made public, we cite RAZIN story first referred to in your Y.262 of 14.7.54, partly on general grounds, partly because of possibility of Press here connecting culprit with name of PEACH.

- Story such as that drafted by Thwaites and enclosed with your PF703 of 8.3.55 would be unobjectionable, subject only to it being made clear that it was B and M who warned M.G.B. of their danger and not vice versa. This would be in accordance with all known probabilities and with earlier recollections of PETROV as several times repeated.

- Spry’s sympathetic co-operation on this delicate matter warmly appreciated.

Notes: (1) RAZIN: Vasilli Razin had been the rezident in Stockholm (1943 or 1944 to spring 1945) when the Petrovs worked there. He is Cookridge’s ‘RAINA’.

(2) PEACH: PEACH was the name given to Philby in the eponymous 1951 inquiry.

(3) DS/2066 & Y79: These items appear in the Minute Sheet of KV 2/3462, but have apparently been withdrawn from the file.

(4) PF 703: This item is likewise missing from the relevant KV 2/3463 file.

What is remarkable is the fact that, while the passage containing the reference to a Soviet agent in London appears in the archive, the apparently obvious hint to the presence and contribution of PEACH in Washington was either never made, or has been weeded from the file. There is no obvious redaction in a long memorandum that describes what Razin knew (‘Supplementary Information from the Petrovs concerning aspects of the Burgess and Maclean Case’), in KV 2/3457, sn. 101a(i), apart from a possible final Item 23. It seems unlikely that a note on the Washington connection would have been extracted and despatched separately, but the message from Mitchell is incontrovertible. The key, however, is the reference to ‘Y.262’, which identifies the precise telegram number, as described above. It does not appear to have been doctored or redacted: there are only three paragraphs, and the third indicates sign-off by simply stating ‘Report follows by bag’.

Mitchell’s admission (in March 1955) that the matter was ‘specially embarrassing’ is very telling. What had been the reaction of MI5 when the message was first received? We do not know. No response is recorded, whether of surprise, or shock, or horror. Yet Mitchell’s communiqué suggests that the SLO was in on the guilty secret – that there was no surprise in the claim that a Soviet agent was (or had been) working in the guts of British Intelligence in London, but that nothing had been done about it. (And it was not Gouzenko’s ‘ELLI’: MI5 had put out feelers to the Petrovs on this possibility, but it had drawn a blank. Vladimir and Yevdokia did not respond to the name.) Was Mitchell simply being clumsy about the possibility of PEACH’s being identified as ‘the man in London’ from May 1951? Why, in March 1955, would he have been concerned about the possibility of the Press’s associating Razin’s defined NKGB agent as Kim Philby? Philby would officially have been an unknown to the Press at this time – and when journalists did learn about him, they would before long discover that he had been out of the country at the time of the escape. In the normal course of events, they would have known nothing about Burgess’s close friendship with Philby, or the fact that he had stayed with him in Washington. It suggests that rumours must have been floating around – kindled no doubt by disgruntled insiders in MI5 – that Philby indeed had acted in that role at some time, and that it was only Edgar Hoover’s publicly naming of him that prompted Lipton to bring the insinuations out into the open. That initiative was abetted, of course, by the People article of September 18 that reminded the British public that the government had been very evasive and secretive about the whole business. So what was the truth behind the ‘Third Man’ claims?

Reinspecting Cookridge’s Claim

Cookridge’s claim needs to be re-inspected. He specifically stated that the Third Man in Washington both alerted Raina (Razin) and sent a friend to London to warn Maclean. Where and how Kislitsyn gained these pieces of intelligence is not explained. Cookridge’s item appears bogus. For one thing, Philby would not have been in direct contact with Razin. Since Philby had been in touch with his Soviet controllers via Makayev in the USA, one would expect Kislitysn to have assumed that the customary secret backstage channels would have been used to alert Maclean. The other vital error is the fact that, as most commentators have now concluded, Philby never arranged for Burgess’s recall to London! A complete mythology has grown (as I explained last month) about the notion that Philby exploited Burgess’s traffic offences to send him to London bearing the bad news, and to alert Maclean. Even if Razin and Kislitysn had later been exposed to such a rumour (one that Yuri Modin reinforced, by the way), they would not, in the period of the escape and its aftermath, have been able to endorse such a story. Cookridge’s nugget states that Razin knew the names of neither the Washington-based agent nor his messenger. I conclude that Cookridge’s informant (probably Liddell) must have packaged up his gobbets of intelligence in more formal dressing in order to try to enhance their credibility. The author’s assertion in The Third Man thus loses all claims to genuineness and authenticity, even though it carries a hint of historical truth.

One has to wonder, again, how clued up Mitchell was on the whole operation, and how sharp he was. He was clearly unaware of the implications of the surveillance on Burgess and Maclean, since he stressed how important it was to clarify that ‘it was B and M who warned M.G.B. of the danger and not vice versa’. That judgment would have been considered dangerous by Dick White, since it explicitly pointed to the ineffectiveness of the surveillance process, or the awkward fact that there had been a messenger, someone who had been in MI5’s direct sights during those hectic May days, but who had been overlooked. Given the thoroughness of the surveillance process, the testimony should have been an enormous wake-up call for MI5: perhaps White and his cohorts did take it seriously, but buried the traces. In any case, it was careless of the custodians of the archive not to have noticed this inconsistency, and to have let Mitchell’s comments pass unredacted.

Another concern of Mitchell’s might have been the disclosure of these reports to the Americans. In David Horner’s 2014 official history of ASIO, Volume 1, from 1949-1963, The Spycatchers, the author writes “Nonetheless, despite initial criticism from MI5 that ASIO was not [sic] passing information to American agencies [sic: plural], from as early as June 1954 Spry was forwarding copies of the Petrovs’ statements to the Americans.” (Chapter 14, p 359). Horner cites as his source: ‘Memo, Spry, 3 June, 1954, ASIO records’. This was despite a published plea by MI5 and the SLO that Spry keep such communications in his private store. What Spry actually did, and why he would even selectively pass on any depositions when the matters were sub judice, is a mystery. Yet, if such information did reach the CIA and FBI, it would not have helped the cause of MI5 to keep a lid on its secrets. It remained under stress.

Nervousness in London

As work on the Petrovs’ book Empire of Fear progressed, the mandarins in London became more nervous, especially when the White Paper was being prepared by Mitchell in September 1955. On August 8, the SLO had informed MI5 that he regretted overlooking the fact that Petrov’s version of his recall had appeared as ‘my recollection’ rather than ‘my belief’. On August 19, Mitchell let J. E. D. Street in the Foreign Office know that he was edgy about requiring further changes to the text (which was, amazingly, already in the hands of various media outlets around the world) since it would draw attention to areas of sensitivity. A couple of weeks later, in light of an imminent press conference geared around the Burgess & Maclean revelations – an event approved by Charles Spry, the ASIO chief – the SLO advised London that the ASIO officers should be able to ensure that the Petrovs stick to a firm line, that the couple assert that the Thwaites draft covers all they know about the defectors, that they will refrain from further speculation, that they will not exaggerate Melinda Maclean’s role, and that ‘no mention to be made of Razin’s story concerning the U.K.’ [my italics].

Robertson and the Foreign Office reacted in alarm, wanting Spry to reverse his decision. In any event, they wanted the Petrovs’ pronouncements to be closely monitored. Apparently, the Petrovs must have been suitably cowed (or bribed), since the conference went ahead without incident, and an innocuous story appeared in the Melbourne Sun of September 17. With an almost detectable sign of relief, Mitchell was able to inform the SLO on September 20 that his White Paper would probably be published the next day, and that it contained no material concerning the story and exfiltration of Burgess and Maclean beyond the content of the Thwaites’ chapter 12, titled Maclean and Burgess (pp 271-176).

The chapter contained no fresh revelations, and covered the activities of Burgess and Maclean quite superficially. It did, however, make a strong but erroneous point about the surveillance of the pair, an assertion that would not have publicly embarrassed the British authorities unduly, but would provoke some anxious soul-searching privately: “When Burgess and Maclean discovered that they were under investigation by the British security authorities, they reported the matter to their Soviet contact in the utmost alarm.” As I have already pointed out, the subtleties of the joint discovery, and the relationship of the alarm to the notion of a ‘Third Man’ informer’ were lost on the journalists when the book was published in 1956, but the claim that the pair were able, despite close surveillance, to make swift contact with their Soviet control was a disturbing disclosure for the Foreign Office-MI5 team.

Yet the problem did not go away entirely. The revelations in Empire of Fear, mild as they superficially appeared, had a much more dramatic impact in Europe than they did in Australia. The Swedish Press was especially attentive to the affair, given Petrov’s disclosure about Soviet subversion in Stockholm, and various newspapers reported on the story – and on the British White Paper – with fascination. One report included the suggestive sentence: “It has not been disclosed whether the British Secret Service was aware of their flight plans”, as if that had been a distinct possibility. The SLO reported on November 12 that the Daily Express had offered £1000 to Petrov if he agreed to an interview with two of their reporters, and he followed up by stating that this opportunity could be used to the security services’ advantage provided that Petrov refused to indulge in speculation and ‘made no mention of the Razin story’.

Mitchell backed down in a cable two weeks later, but attached greatest importance to the elimination of any reference to Razin. The same day he informed de la Mare in the Foreign Office what was going on, again stressing that the interview would go ahead ‘so conducted as to exclude mention of the Razin story’. Like Basil Fawlty mentioning the war, he presumably believed that he would get away with it. Yet the panic might have passed. In December, Evdokia was very ill, and thus could not take part, and Vladimir was considering that his existing contracts might prevent him from taking the Express’s shilling.

Moreover, the previous month, further evidence of Philby’s guilt had arisen. Christopher Andrew writes (Defend the Realm, p 431) how a fresh VENONA decrypt had been provided to a group of VENONA initiates by Meredith Gardner on October 10, 1955. It referred to agent STANLEY’s contributions to the analysis of the Gouzenko affair in September 1945. The context clearly showed that STANLEY was Philby: one of those in MI5 who were indoctrinated into the disclosure was C. P. C. de Wesselow (D1a), the officer who had been carrying on the negotiations with ASIO over the Petrovs. Yet nothing was done.

Philby’s Story

Meanwhile, what of Philby? In the final chapter of My Silent War (‘The Clouds Part’), he described how the ‘next storm gathered’ after the defection of Petrov [sic: singular], and ‘some not very revealing remarks he made about Burgess and Maclean’, and he associated these disclosures with the Fleet Street quest for the Third Man. Yet he claimed that, before the events of April 1954, when he was seriously considering the possibility of escape, he received an encouraging message that prompted him to think again. He wrote:

Finally, an event occurred which put it right out of my head. I received, through the most ingenious of routes, a message from my Soviet friends, conjuring me to be of good cheer and presaging an early resumption of relations. It changed drastically the whole complexion of the case. I was no longer alone.

Who was the bearer of the message? Suspicion has fallen on the Australian Charles ‘Dick’ Ellis, who, having retired from MI6 when investigations into his loyalty were dropped, in September 1953 sailed out to Australia to work for ASIO on a two-year contract. Yet, after being present at a briefing by Charles Spry in November of that year when Petrov’s impending defection was being discussed, he suddenly returned to London. As Ellis’s biographer, Jesse Fink, relates, Chapman Pincher and others had theorized that Ellis had mistaken Vladimir Petrov for his old nemesis Vladimir von Petrov, and caught fright. He arrived in London on February 11, and, soon afterwards tried to contact Philby, suggesting they meet. In The Spycatchers, Dabid Horner cites a 1967 letter from MI5’s A. A. Macdonald to Spry, indicating that Fink and Philby probably never met.

Yet the recent release of the PEACH Personal File shows that Philby was still under surveillance, and that he and Ellis did in fact get together. KV 2/4731 indicates that they met at the Athenaeum on March 4, 1954, although the event is not recorded until May 12 (sn. 490a). From a telephone intercept, we learn that Philby told his girl-friend on March 3 that he would be meeting Ellis the next day. But there is no trace of his telling her that ‘the clouds are parting’ (a touch added by Pincher) after their meeting, and Philby does not appear to mention what had transpired to Tomás Harris [HONEY], with whom he was heavily involved in plans to write his memoir at the time. Thus, while the possibility that Ellis gave Philby a serious warning is real, it is unlikely that Philby would have interpreted Ellis’s signals as an opportunity to relax. (I recommend Fink’s Eagle in the Mirror for an analysis of this puzzle, although it was published before the record of the Philby-Ellis encounter was declassified.)

Ellis’s behaviour was very odd. It was one thing to make a very sudden and flamboyant journey from Australia to the United Kingdom, giving spurious reasons for his travel plans, but then seeking out Philby could have drawn even more attention to his intrigues. And, if he did intend to transmit a warning, what could Philby do? By then, he had no contact at the Soviet Embassy with whom he could communicate, and, if he had, giving an alert about the imminent Petrov defection, and thus pre-empting it, would only have drawn attention to his meeting with Ellis. Perhaps the visit makes sense only in the context of Ellis’s wanting to warn Philby to clear out, but was that gesture not a little excessive?

Philby believed that someone had leaked his name to the newspapers, and referred to a Daily Express article (undated), in which a ‘security officer from the British Embassy in Washington’ had been asked to resign. One of his friends in MI6 told him that the leak came from a retired senior officer of the Metropolitan Police, a gentleman they both knew ‘for his loose tongue’. Yet Philby adds that it took four years for the Press to get on to him, which would suggest that it was not until the summer of 1955 that the rumours started flying. That does not tally with the timing of the critical cables deriving from the intelligence from Kislitsyn and Razin that were sent in July 1954. Of course, nothing that Philby writes can explicitly be trusted, but perhaps all that is proved by these events is that Graham Mitchell did not have his ear very close to the ground.

The Washington Connection

So where did the story about the tip-off man in Washington originate? I summarize what I think are the relevant facts:

- Vladimir Petrov did not reveal anything about a Washington link in the interrogations undertaken before his wife joined him on April 20.

- The much-highlighted reports in the Press on April 28, 1954, from both Australia and the United Kingdom, were provocative, but melodramatic, and held little substance.

- On April 28, Morley Richards of the Daily Express in Australia claimed that the latest information had come from the Australian Government, ‘who was prepared to sell the whole Petrov story to the highest bidder’.

- On April 28, the Australian Government offered to make the Petrovs available for interview by six members of the Press.

- The event was scheduled for May 10, but was cancelled so as not to prejudice the Commission’s Inquiry.

- The Petrovs felt betrayed by the Daily Express article. Vladimir dried up, but he said he had already told all he knew. Yevdokia had a special relationship with Kislitsyn, and she may have known more.

- The SLO in Australia judged the Daily Express article to be contradictory, and suspected that it was angling stories in order to gain a reaction, whether confirmation or denial.

- There is no mention of the Washington link in any of the exchanges between Australia and London during April-May 1954. Nevertheless, since many cables are missing (as can be determined by noting the discontinuity of the numbers), complete exchanges may have been excised from the record.

- Both MI5 in London and ASIO were aware by July 14, 1954 of Razin’s allegation of a Soviet agent in London.

- Cookridge’s citation of a text (made in 1967) has a ring of genuineness (it sounds like an official message) but not authenticity (the content is dubious). The attribution of the statement to Petrov may have been guesswork on his part. His informant probably misled him, by dressing up a rumour in more official-looking garb. Cookridge was wrong about the assertion that Petrov’s evidence had appeared in the Commission Report.

- In the archival material relating to the events around July 14, 1954 [see above], no messages referring to the Washington link can be found, but that date coincides with the recent release of testimony given by the Petrovs to the Commission, specifically that of Yevdokia. [KV 2/3444, sn. 308a].

- By July 1954, testimony given by the Petrovs was considered sub judice, since the Commission had started its work,

- In a period of one month (January 24-18 February 1954) three other Soviet agents, Rastvorov, Deryabin and Khokhlov, had defected – in Japan, Austria and West Germany, respectively. Khokhlov, in particular, claimed to bring knowledge of the Burgess-Maclean escape with him.

- The head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, had in June 1951 been supplied with information by MI5’s Arthur Martin and Percy Sillitoe that marked Philby as a tip-off man in Washington.

- Hoover was in contact with ASIO Director-General Spry over the Petrov testimony, and had checked it against what the FBI had been told by Rastvorov.

- At some stage between the issuance of the White Paper (September 23, 1955) and the subsequent debate in the House of Commons (November 7), in an undated article, Percy Hoskins made reference to that same person in Washington.

- Insiders from MI5 or from the Special Branch of the Metropolitan Police had probably been leaking Philby’s name to the Press for some months before the Hoover disclosures.

There is no obvious place in the Petrov archive where the Washington reference could have been smoothly entered, and later redacted. Mitchell’s reference is specific, and verifiable. Even though its content is vague and not totally logical, it would seem that the story of a London-based agent emanated here, rather than from other defectors. On the other hand, outside Philby’s own testimony, no precise reference to a Soviet agent working in Washington has appeared apart from Hoskins’ rather vague statement in his article between the appearance of the White Paper and the debate in the House of Commons. Hoskins probably gained his main story from Hoover, although he was certainly being fed hints by disgruntled insiders as well. Likewise, the detail given in Cookridge’s statement suggests that an insider gave it to him, and that it came from an item in MI5 files subsequently weeded, but the authenticity of the piece is highly dubious. Cookridge had good contacts within the intelligence services: he used them to solid effect in his book on SOE. What is surprising is the fact that he waited until 1967 to tell the world, and he then got his facts wrong. I judge it unlikely that he invented the whole story, but he may have embellished a simpler version. Yet the discomfiture of Mitchell shows that Cookridge’s claim was essentially correct.

Summary and Conclusions