(My original plan was to publish this essay at the end of September, since I had a few weeks ago completed a study of the problems of Goronwy Rees and Anthony Blunt in the summer of 1951 that was ready for the August coldspur issue. I thus started work on a piece on Victor Rothschild, targeted for September. And then a correspondent alerted me to the fact that Tim Tate’s new book, To Catch A Spy, enhanced with the subtitle How the Spycatcher Affair Brought MI5 in from the Cold, was going to be published in August. I immediately pre-ordered the item from amazon.uk, but decided that I needed to put my stake in the ground on Rothschild, Wright, Pincher and the Spycatcher business before I was influenced in any way by what Tate wrote. Thus I accelerated the development of this month’s piece: Rees and Blunt will now appear at the end of September. My copy of To Catch A Spy arrived a couple of days ago: I shall start reading it today. I shall dedicate my October bulletin to a review of Tate’s book, and to an update on the Borodin affair – which is turning out to be even more sinister than I earlier described.

P.S. This piece was created in some haste. I intend to re-structure it at some stage to give it a more logical flow. I hope that my readers will be indulgent, and will understand my desire to lay out the facts of my story promptly.

P.P.S. I have just noticed a report in the Times dated August 16 that describes Margaret Thatcher’s collusion with Sir Robert Amstrong, using Rothschild and Pincher, to promulgate the Hollis accusations that derived from Wright. See: https://www.thetimes.com/uk/history/article/margaret-thatcher-approved-leak-m15-rml5xdgrd .I imagine this matter is covered comprehensively in Tate’s book, and shall comment in my October posting.)

Contents:

Introduction

- Molehunting:

‘The Climate of Treason’

Rothschild and Wright

‘Their Trade Is Treachery’

An Impossible Delivery

Manipulation and Misinformation

Pincher’s Version

2. Agent of Influence

3. Zionism

4. MI5 & MI6 Postwar

5. The Kew Archive:

Introduction

Surveillance

Investigations (1)

Investigations (2)

Disclosures and Explanations

Rothschild’s Self-Importance

Burgess as Financial Advisor

Tess and Blunt

6. Conclusions

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

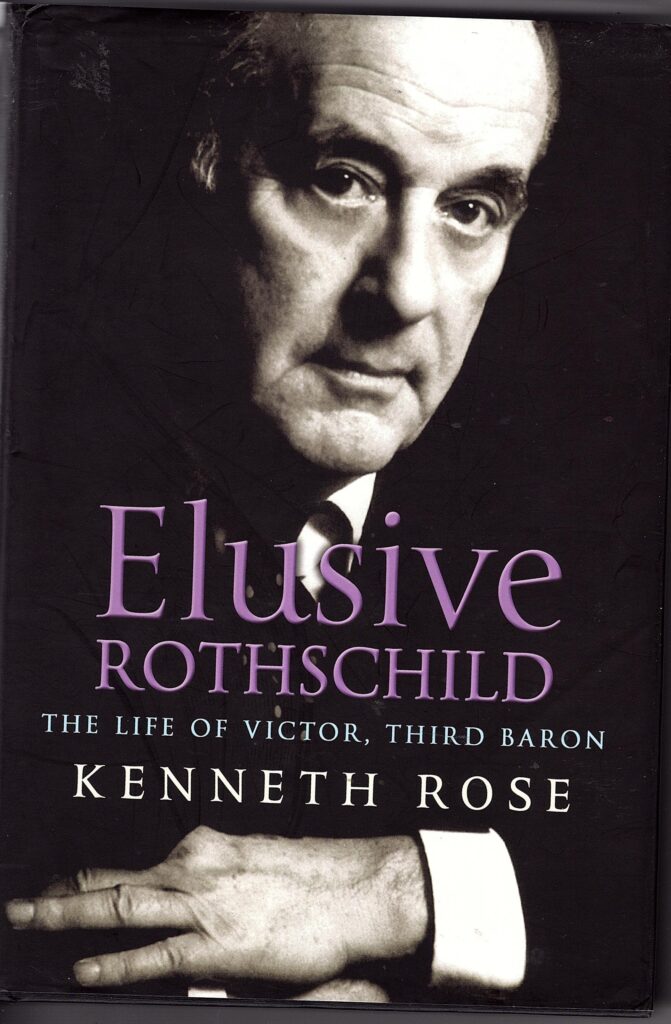

What was Lord Rothschild up to at the end of World War II? And why was he so inextricably involved with the intelligence leakages of the 1980s? The questions about his loyalties, his connections with the Cambridge Five, and his activities in support of the Israeli effort to build an atomic bomb continue to float around in various memoirs and articles. Yet it is hard to pin down a reliable account of his life: what one might expect to be the gold standard of accuracy and integrity, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, has not updated its entry since 2010, and it is based largely on Kenneth Rose’s generally favourable but shallow biography of him, Elusive Rothschild. Since then, both Russian and British archival material has appeared (with several large files having been deposited at Kew by MI5 in 2022), yet no authoritative new account has appeared, so far as I know. The Wikipedia entry is a little more exploratory, but likewise deficient: it was updated recently, but apparently only because of the death in February of Jacob Rothschild, Victor’s eldest son. The Andrew Lownie Agency has recently announced that Weidenfeld & Nicholson has acquired the rights to Roley Thomas’s biography of Victor, titled The Spy and the Saboteur: the Untold Story of Victor Rothschild (see https://www.andrewlownie.co.uk/authors/roley-thomas/books/the-spy-and-the-saboteur-the-untold-story-of-victor-rothschild). In what way Rothschild was a ‘spy’ or ‘saboteur’ (as opposed to a counter-espionage officer responsible for detecting sabotage attempts) is undeclared: I shall have to watch out for the publication of this volume, which is not due until late next year.

The most damaging claim against Lord Rothschild is that he had been a Soviet agent of some kind – perhaps simply an ‘agent of influence’, but also, in a more imaginative leap, the ‘Fifth Man’, at a time when Cairncross’s role had not been established. (Roland Perry’s assertion that Rothschild was the ‘Fifth Man’ can be quickly rejected, even though Perry dug out some intriguing ‘facts’ about his Lordship.) I dedicated a chapter in Misdefending the Realm to the phenomenon of agents of influence working in the shadows to assist Soviet objectives, and included Rothschild as the leading figure in that category. That same claim appeared from the Russian side, with the recollections of Ivan Serov, one-time chairman of both the KGB and the GRU (who died a month before Rothschild in early 1990), revealing through his posthumously published memoirs that Rothschild had for a short while been a valuable agent of influence.

In this piece I explore several critical aspects of Rothschild’s career. First of all, I examine closely the extraordinary role he played in the molehunting sagas of the 1970s and 1980s, as one in a triumvirate of deceptive characters. I consider this period very significant, because it brought parts of Rothschild’s hitherto private career into the public eye, and he began to realize that he could no longer control the narrative of his life. I believe that that recognition buffeted his ego, and his sense of prestige, and he never recovered from it. I next delve into other dimensions of his roles, using a variety of archival sources, that highlight some of the major conflicts in his life. Lastly, I offer a detailed analysis of the MI5 Personal Files on him and his wife (KV 2/4531-4534), recently released, which I believe are revealing as much for the inertia displayed by MI5 over the Rothschilds’ prevarications as they are for the intrinsic accounts that the couple gave of themselves.

I shall not cover in detail Rothschild’s career in his official capacity at MI5 during the war. He notably set up the B18 counter-sabotage section (in 1941 renamed B1c), and displayed some courage in his dismantling of bombs, although the self-aggrandizement of his feats, leading to the award of a George Medal, did not endear him to his colleagues. His other remarkable achievement was to introduce Anthony Blunt to Guy Liddell, who subsequently recruited him as his personal assistant, with disastrous consequences. He was also responsible for helping Eric Roberts set up the ‘Fifth Column’ to penetrate a group of Nazi sympathizers. (For a comprehensive account of this operation, see Robert Hutton’s Agent Jack, and my comments at https://coldspur.com/a-thanksgiving-round-up/ ). At the end of the war, Rothschild successfully recommended to Liddell that his assistant, Tess Mayor, be awarded an M.B.E. for gallantry in Paris, but the objectivity of his judgment was somewhat tarnished by the fact that in 1946 he divorced Barbara and married Tess in August of that year. Overall, his reputation within MI5 – and outside – was good, to the extent that Duff Cooper even suggested that he should be appointed Director-General when Petrie retired.

- Molehunting:

‘The Climate of Treason’

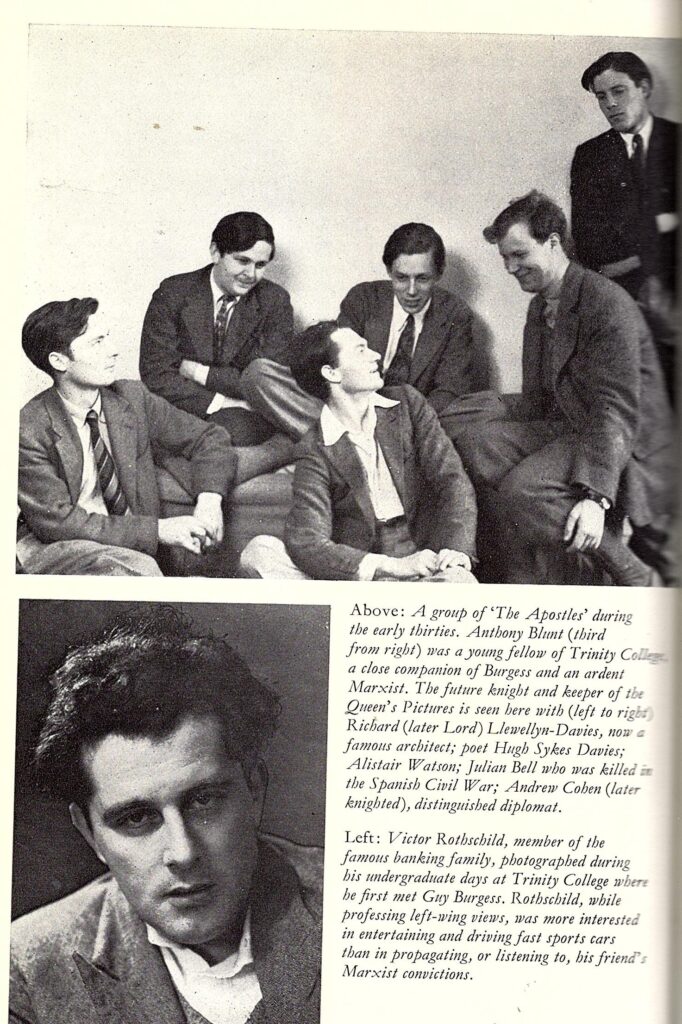

Victor Rothschild’s problems started when he gained some unwelcome attention after the publication of Andrew Boyle’s Climate of Treason in 1979. Not only did a prominent photograph of the noble lord appear under one of a set of ‘Apostles’ from the 1930s (which included Blunt, ‘a close companion of Burgess and an ardent Marxist’), Rothschild was also described in potentially damaging ways in the text. He was presented as ‘the amiable Trinity neighbour’ of Burgess at Cambridge, who ‘professed sympathy with Socialism, but took no noticeably active part in proceedings of the non-Communist rump of the Labour Club to which Philby and Lees both belonged’. That was in fact a distortion of the politics of the Cambridge University Socialist Society, but the juxtaposition was nevertheless a little embarrassing. Furthermore, Boyle explained that Burgess had received Rothschild money for services rendered, and that he had been a tenant of Rothschild’s flat in Bentinck Street during the war.

A more serious incident reported by Boyle occurred during the winter of 1944-45, when Philby, Burgess and Malcolm Muggeridge were staying at the Rothschild mansion in Paris. Rothschild (as described by Muggeridge in his 1973 memoir Chronicles of Wasted Time) was provoked to criticize the withholding from the Soviets of Bletchley Park secrets concerning the German order of battle. That was a sensitive matter, as it suggested that Rothschild (and the others debating with him) knew for certain that such material had been withheld, as if they had all been privy to the highly secret way in which intelligence had been passed on to the Soviets. One could pose the questions: had any members of the group been told by Moscow that it was not receiving unrefined ULTRA transcripts through official channels, and how did the NKVD come to that conclusion? If that was indeed the case, whom did Moscow tell?

This gathering of anecdotes had started a buzz of chatter, which the journalist Auberon Waugh picked up in an article in the Spectator in June 1980. This piece was even significant enough to be copied into PREM 19/3942, a file curiously titled ‘Security of the Secret Service – Professor Blunt: Terms of Reference of the Home Affairs Select Committee with regard to the Security Service’. The whole text of the article (‘Lord Rothschild is Innocent’) can be seen on page 101. Of course it is a provocative title, since it implies that the subject had perhaps in some quarters been regarded as guilty, and Waugh is out to vindicate him. Yet Waugh had a notorious gift for irony, and the attention given to Rothschild surely displeased Waugh’s subject.

What Waugh had done was to identify that the anonymous hereditary peer who (according to Boyle) had been one of those persons questioned by MI5 after the defection of Burgess and Maclean was in fact Lord Rothschild, and Waugh qualified his revelation by stating that it would be very surprising if MI5 had not asked him to help in their investigations. Furthermore, ‘any suggestion which implied that Lord Rothschild could even have been under suspicion by MI5 as a Soviet agent or witting concealer of Soviet agents is so preposterous as to belong to the world of pulp fiction. . . .’. Waugh skillfully avoided any libel suit with this wording, but, according to Roland Perry in The Fifth Man (1994), Rothschild was very worried, and sensed trouble ahead. Perry’s mission was, however, to prove that Rothschild was indeed the ‘Fifth Man’, and he was as wrong about that as he was in underestimating John Cairncross’s contribution.

Chapman Pincher later went on to defend Rothschild’s reputation in Too Secret Too Long (1981), where he stressed Victor’s war-record, his working for MI5, and his award of the George Medal for bravery in anti-sabotage activity (something that the vainglorious lord had promoted a bit too eagerly). Pincher expanded on the Bentinck Street charivari, but absolved his lordship since he asserted that he could have had no knowledge that the residence he had sub-let had been harbouring two spies. “Innuendoes about his loyalty are completely groundless as his part in the exposure of Philby alone showed”, he wrote, an ingenuous statement that in its dubious logic downplayed the role of intrigue. Moreover, Pincher failed to mention Rothschild’s close association with the communists at Cambridge, and their memberships of the Apostles.

In 1980, Rothschild’s reputed contribution in exposing Philby was almost certainly not broadly known. Flora Solomon’s From Baku to Baker Street, in which she described her encounter with Rothschild in Israel, in 1962, where she informed him of her strong belief that Philby and Tomás Harris had been spies, was not published until 1984. (Did anyone make note of Pincher’s insight at the time?) By this time, however, Rothschild was beginning, in a defensive manoeuvre, to become involved in a curious triad consisting of himself, Chapman Pincher, and Peter Wright, an arrangement that would cause some enmities and jealousies, but which eventually led to the highly successful publication of Wright’s controversial Spycatcher in 1987. Pincher probably became acquainted with Rothschild in the mid-1970s. In Treachery, he describes how Rothschild had introduced him to Dick White ‘several years before’ 1982, and he also states how he had been in regular touch with him ever since the exposure of Blunt in 1979. In 1980, Pincher had been giving Rothschild advice concerning a possible libel action over the media speculation that he might have been a Soviet agent, even the infamous ‘Fifth Man’ of the Cambridge quintet. The Auberon Waugh article was a major irritation. Suddenly, on September 4, Pincher received a telephone call from Rothschild asking him to come and meet an ‘overseas acquaintance’ of his – who turned out to be the disgruntled Peter Wright. Pincher emphasized the unexpectedness of this call. But how did the participants arrive at this strange encounter? Sadly, the testimonies of all those involved – including Dick White – are riddled with untruths.

Rothschild and Wright

The association between Wright and Rothschild went back much further. As Wright explained in Spycatcher (1986), Roger Hollis had introduced Wright to Rothschild in 1958, when Wright was trying to set up a scientific department in MI5, and Rothschild’s enthusiasm for what Wright was doing started a long period of admiration for Rothschild in the frequently under-appreciated MI5 officer. (One has to be wary of relying on what Wright wrote in Spycatcher, but these anecdotes sound authentic.) The pair maintained a supportive relationship, and Wright was asked to install Special Facilities (i.e. microphones) in Rothschild’s flat when Arthur Martin interviewed Flora Solomon there in the autumn of 1962. Rothschild was nervous about this, and sceptical that the devices would be disabled afterwards. As Wright wrote: “Victor was always convinced that MI5 were clandestinely tapping him to find out details of his intimate connections with the Israelis, and his furtiveness caused much good-humored hilarity in the office.” Rothschild would presumably have been shocked to learn of the surveillance carried on against him in 1951 when he and Tess were in regular contact with Anthony Blunt. In his 1979 book, Inside Story, Chapman Pincher refers to an unnamed ‘dissident’ MI5 officer (who must have been Pincher’s informant) who sought help from ‘a senior Whitehall personality’, known as ‘Q’. There is now no doubt about their identities.

A very stagey and melodramatic episode then followed, according to Wright’s largely apocryphal account. As he told it, shortly after Blunt had confessed (in 1964), he (Wright) was summoned to Hollis’s office, where he also found Rothschild and Furnival Jones. Hollis had just informed Rothschild about Blunt’s recent confession, and Rothschild looked ‘devastated’. The upshot was that Rothschild wanted Wright to be the bearer of the news to his wife, Tess, who had been very fond of Blunt (and had some sort of an affair with him, if what Pincher wrote in Treachery, based on what Kenneth Rose told him, can be trusted). “To her,” wrote Wright, “Blunt was a vulnerable and wonderfully gifted man, cruelly exposed to the everlasting burden of suspicion by providence and the betrayal of Guy Burgess.” Why Rothschild did not feel capable of taking the news to his wife, and why he thought that she would think better of him for delegating the task to the technical officer from MI5 (who admittedly had come to know Tess very well), was not explained. The mission was accomplished. Wright went with Evelyn McBarnett. Victor left the room. Tess was incredulous, and went ‘terribly pale’ as Wright told the whole story. The story is assuredly untrue, as the Rothschild Personal File reveals [see below]. It was a ruse to absolve Rothschild and his informer (Dick White) of breaching confidences, and Victor of recklessly informing his wife about the confession. In his account recorded in the Rothschild file, Wright knew that Tess had already been told about Blunt’s confession.

Wright had kept up his association with Rothschild over the years. Rothschild would help him in his molehunts, dropping hints, and arranging another meeting with the reluctant Flora Solomon, who gave a lead to Sir Dennis Proctor, whom Wright believed had leaked information to Burgess. Rothschild had been appointed head of the Central Policy Review Staff (CPRS) by Edward Heath in 1970, and thus had useful connections in government. Wright’s account of the events seems somewhat inflated, although the records in the Rothschild archive show a close level of familiarity. Rothschild soon addresses his letters to Wright as ‘Dear Peter’. On the other hand, Wright received some antidote to his enthusiasm for Rothschild: he wrote that the defector Anatoliy Golitsyn had told him in 1968 that the agents DAVID and ROSA named in the VENONA transcripts were in fact Victor and Tess Rothschild. Wright probably did not pass on this insight to his idol.

Thereafter Rothschild was involved with Wright in MI5 Director-General succession planning, using his influence to thwart Civil Service preferences. (Wright’s claimed position of influence here is not convincing.) And in 1975, when Blunt was dangerously ill, Rothschild expressed some nervousness as to what he might reveal in any testament to be made available after his death. He pressed Wright to provide a full briefing on ‘the damage Blunt could do if he chose to tell all’, indicating some serious alarm. While Rothschild ingeniously presented this as a concern for the reputation of current politicians and members of the government, he was surely holding his own interests paramount. In any event, Wright agreed that a full outline of the Ring of Five and their sympathizers should be compiled, listing all names even if no proof were attachable, and he duly composed it. It apparently pleased Robert Armstrong in the Cabinet Office (a close chum of Rothschild’s through the CPRS connection, and at first glance perhaps a surprising participant in this scheme), but how this project related to the possible exposure by Blunt, or whether Rothschild’s name appeared among the forty names listed, is not made clear. Spycatcher concluded when Wright said ‘farewell’ to Rothschild, and left for Australia. It would be left to others to describe the messes that followed.

Exactly what were the interactions between Rothschild, Pincher and Wright is hard to pin down, as much of the testimony comes from Pincher himself, who was duplicitous in attempting to conceal the fact that he had known Wright for some time, and had already been using his leaked intelligence, at the time that he was ‘introduced’ to Wright by Rothschild in September 1980. In Molehunt (1987), Nigel West devoted a chapter (‘The Red Shield Connection’) to the negotiations: it is a rich and fascinating account, benefitting especially from references to many comments appearing in the press in 1986, but impaired by West’s tendency to go off on many barely relevant tangents. West very capably draws out many of the contradictions implicit in the statements made by Pincher and Wright concerning the negotiations. In any event, Rothschild’s strategy in paying Wright’s airfare to come to Britain, and then setting up mechanisms for Wright to be paid royalties from the ensuing book by Pincher based on Wright’s memoirs (Their Trade Is Treachery), was astonishing. Rothschild was essentially encouraging a retired civil servant to breach the Official Secrets Act, and rewarding him for it. This was either a very reckless move, or else had some official blessing. What was Rothschild thinking?

‘Their Trade Is Treachery’

West expressed puzzlement over Rothschild’s motivations in encouraging Wright: he judged that his lordship was surely over-reacting to the Prime Minister’s statement of November 1979 that had justified the immunity arrangement with Blunt on the grounds that he might be able to assist MI5 in investigating Soviet penetration. West hinted at some possible underlying reason for Rothschild’s embarrassment by listing the conventional aspects of his career that may have alarmed the baron: the Burgess connection and payments; the DAVID and ROSA allegations; the Bentinck Street affairs. Yet the first items would have been known only to MI5 insiders, as would the other startling fact that West introduced – Rothschild’s recommendation to Guy Liddell in 1940 that he recruit Blunt to MI5. This was a startling revelation by West, as Liddell’s Diaries had not yet been published, and it should have generated much more interest than it appeared to. It must have been the secret that caused Rothschild the most anxiety. Yet again, his hyperactivity in wanting to control the narrative indicated a measure of guilt rather than innocence.

The precise nature of the communications that occurred between Wright, in Tasmania, and Rothschild, in Cambridge, leading up to Wright’s visit in September 1980 was for a long time unclear. From the authorized corner came Christopher Andrew, in Defend the Realm (2009), customarily exploiting ‘Security Service archives’ without identifying them. He suggested that Wright had written to Rothschild some time between 1976 and 1980 complaining about his pension arrangements and voicing his belief that writing a memoir might bring him in the money he needed. At that stage, Rothschild alerted MI5’s Director-General to Wright’s plans, suggesting that at that time he (Rothschild) was not unnerved by phenomena such as the Blunt confession, and was firmly on the side of the authorities. Yet when Wright wrote again in 1980 – Andrew provides an extract from the letter, but does not date it or source it – his letter explained that he thought he could publish his memoir, but believed he could avoid any penalty under the Official Secrets Act by staying in Australia. Now Rothschild took a different tack: he encouraged Wright, did not inform MI5 of what Wright was planning, and instead paid for Wright’s passage to the UK that summer. This was a shallow analysis by Andrew.

The story was in fact more complex than that. In 2003, Kenneth Rose had in Elusive Rothschild provided a closer breakdown of the events, having been able to inspect some of the correspondence. He stated that the first letter was sent in November 1976, thus confirming that the Director-General was Hanley. In this letter, Wright hinted that he wanted to write about some of the confessions that Blunt had made to him – which must have severely alarmed Rothschild. (Rose does not make that point, but since Rothschild had already expressed to Wright the previous year his concern about Blunt’s revelations, Wright’s intentions should not have been such a surprise to him.) Rothschild accordingly had not been idle, although why he thought that some enhancements to Wright’s pension might deter him from spilling the beans is not clear. Knowing the problem concerning the pension, he followed up with Hanley, suggesting a review of the arrangements. Hanley was unable to get the Civil Service to change its rules, and Rothschild had to inform Wright of that decision in May 1977. Two months later, when Wright expressed his determination to continue writing, Rothschild tried to assume a more active role of caretaker for Wright’s effusions, believing that in that way he would be able to control the narrative. Tess Rothschild also wrote to Wright, referring to the rumours circulating about a projected book by Andrew Boyle, and also mentioning that Anthony [Blunt] was nervous about his possibly being named.

Rose added further twists to the story. Tess wrote to Wright again just before Boyle’s book came out, updating him on developments. Her husband was not unduly harmed when it did appear (apart from the placement of the photograph), but his health suffered badly in the first few months of 1980, and, when the revised edition of The Climate of Treason was issued a few months later (with Blunt named, and three columns of indexed entries dedicated to him), it contained veiled references to two members of the House of Lords who had been questioned back in 1951, and Rothschild was soon identified as one of them. That brought events up to the Auberon Waugh article [see above], and, according to Rose, Rothschild panicked. Having made a vain attempt to ingratiate himself with Margaret Thatcher, he turned again to Wright in the hope that he might be able to produce a paper that would list all his loyal services to MI5, and thus exonerate him. That led to the visit by Wright in late summer, armed with a three-page testimonial and ten chapters of his embryonic book. Rothschild later told Rose that he had destroyed the testimonial. Yet Roland Perry was able to provide a summary of all the achievements that Wright compiled to portray Rothschild’s loyalty in his chapter ‘Victor’s List’ in The Fifth Man.

According to West, when Rothschild saw Wright’s chapters, he changed his plan, and decided to assist in the publication of the book. The essence of the text now consisted mainly of charges against Roger Hollis, and Rothschild believed that it would thus powerfully distract the attention of the world from himself. Wright was quoted in a statement to the press in December 1986 that he showed the ‘true facts’ about Hollis in a paper that he laid before Rothschild. Yet the embryonic story still held troubling information about Rothschild, and probably other MI5 officers. By the time it arrived in print as Pincher’s Their Trade Is Treachery it had been censored: it conveniently did not include a single mention of Rothschild. A whole chapter on the peer had already been removed, at Rothschild’s insistence. It would seem that Wright and Rothschild must have come to some sort of agreement that guaranteed support as a quid pro quo for some excisions from Wright’s text.

In any event, Pincher was then introduced, and a deal was quickly struck, with Wright requesting 50% of any net profits that the book would bring. Rothschild set up the banking arrangements, and then largely absented himself from the proceedings. The correspondence between Pincher and Wright that followed made coded references to what ‘our mutual friend’ was undertaking to pass on revenues. We can see now that in his letters to Rothschild Wright had hinted at some of the possibly embarrassing disclosures he was prepared to make, and that Victor probably alerted his friends in MI5. They probably then all agreed to a deal whereby Rothschild would help Wright in exchange for Wright’s silence over sensitive issues, especially those potentially damaging revelations about Rothschild himself. The story was primarily about Roger Hollis. The point was, however, that any embarrassing revelations could not be restricted to Rothschild alone. Intelligence high-ups were happy to delegate the project to the safe pair of hands – and deep pockets – of Victor Rothschild.

An Impossible Delivery

While it is tangential to the Rothschild story, I believe the delivery of Their Trade is Treachery merits further attention, since the timeline defies credibility. Perry wrote that Pincher had to fly to Tasmania in October to carry out further research with Wright, where he discovered that he would have to ‘discard Wright’s document of nine chapters – 9000 words in all, after the removal of the chapter on Rothschild’. Pincher returned to London, gained the enthusiastic interest of his publisher, William Armstrong, at Sedgwick & Jackson, and set to work. Yet the book was published as early as March 13, 1981. Pincher had managed, apparently from scratch, to compile a book of over 100,000 words, in a few months. Moreover, as Pincher wrote in his ‘Postscript’ to the second edition of the book (the version in my possession), he claimed that MI5 had gained a copy of the script ‘at least a week in advance and probably well before that’, which telescopes the gestation period even further.

My conclusion is that Wright and Pincher must have been collaborating on the book that turned out to be titled Their Trade is Treachery for some time beforehand. Pincher did not inform his publisher of his source, or of the Rothschild connection, and it simply seems impossible to me that he could have put together such a monumental (though wrong-headed) work in that time when he was the other side of the world from Wright, and, according to his account, had had to discard everything that Wright had written. My suspicions were reinforced when I went back to Pincher’s Treachery (2011), where he reported that there was ‘disappointingly little meat in the chapters I saw’, and, extraordinarily, that ‘there was no mention whatever of the Hollis case’. (In November 1986, however, Pincher told the Daily Express that Wright had shown him a list of traitors, including Hollis, with which he proposed to deal.) Pincher said that he had to take notes from the chapters, as Wright would not let him carry with him anything that could be traced to him. He claimed, however, that he was able to extract from Wright all he knew about Hollis in ‘nine long days’. He arrived back home on October 24, and started work on the book immediately. Pincher then claimed that he wrote the book in less than four months, and delivered the typescript on January 13, 1981.

Against this lies a timeline offered by Nigel West that makes the project look totally impossible. In Molehunt, he has Pincher arriving in Tasmania on October 19 for a visit lasting two weeks. Returning to Britain (‘carrying Wright’s draft manuscript’ [!]), Pincher next offered a two-page synopsis to his publishers, and signed a contract with Sidgwick & Jackson on December 12, 1980. Pincher himself wrote, in A Web of Deception (see below) that the contract did not become valid until December 23. On that same date, miraculously, Pincher wrote to his publisher, William Armstrong, that he was ‘nearing the end of my labors’, ‘incorporating Wright’s information with what I already knew’. (Yet, several years later, he was able to state that MI5 had been able to prove that Wright had been a major source for the book.) According to West, Pincher was unaware that a copy of his synopsis had been handed to MI5, but Pincher stated that he knew that the shorter, two-page version of the synopsis had been shown to Sir Arthur Franks, the head of MI6. Pincher continued to work on his manuscript, which he delivered, with required legal changes, at the end of January, 1981. That constituted a very productive effort right through the festive season. The question must also be asked: why was Pincher so quick to agree to dedicate 50% of his royalties to Wright if there was so little that was new, and Wright would not even hand over his notes? It reinforces my view that Their Trade is Treachery had been largely written before Pincher ‘met’ Wright at the Rothschilds in September 1980.

In any event, by my reckoning, the period between October 24 and January 13 is less than three months, so I do not know how Pincher performed his calculations, nor whence he derived his source material, if all he had was notes taken from talking to Wright. He does not explain what happened to the chapters that Wright brought over to show Rothschild. The comment about the lack of coverage of Hollis is bewildering, given what West wrote, the fact that that story was one of the features that provoked Rothschild’s interest, and the obvious truth that Wright had a big grudge against Hollis. (In fact Wright did not publicly denounce Hollis until his Granada TV appearance in July 1984.) In addition, Rose provocatively quotes a letter from Rothschild to Pincher, written in July 1980, where Rothschild was ‘so convinced of Hollis’s innocence’, that he warned Pincher ‘against a small number of people who have got the subject on the brain to the extent of paranoia . . .’. If Rothschild and Pincher were discussing Hollis the month before Wright was summoned to the United Kingdom, what was their business, and who had already been feeding Pincher with the material for Their Trade is Treachery? Was it Wright’s testimony – and maybe threats – that changed Rothschild’s attitude towards the accusations against Hollis, and make him more supportive of them? It sounds like that to me.

Manipulation and Misinformation

Pincher was obviously duplicitous about the whole affair. He continued to claim that he had not met Wright until Rothschild introduced him that summer, and providing contradictory information about the material he had access to. Yet he needed an intermediary to maintain the fiction that he and Wright had not met before: else Wright could simply have contacted him about assistance with writing and publication. In Treachery, Pincher stated that he had ‘been looking for someone like Wright for forty years’, ignoring the fact that his books must have been dependent on carefully managed leaks from within MI5. In Molehunt, Nigel West wrote that Pincher ‘had few, if any, sources within the British intelligence community’, but then went on to describe incidents that plainly showed he was the beneficiary of multiple leaks. He craftily showed that an episode in Inside Story (p 153), could easily be traceable to Wright as the ‘dissident MI5 officer’ involved in Operation SATYR. If Pincher was already speaking to such dissidents ready to talk to him, why would he suddenly deny their existence when retelling the encounter of September 1980? In any event, a war of words, with Rothschild and Pincher both trying to control the narrative, would erupt after the fall-out from the publication of Their Trade Is Treachery, spilling eventually into the controversial cauldron of the Australian law-courts.

It was the possibility that someone in intelligence had been manipulating and encouraging the publication of damaging accusations against Hollis that aroused these contrary narratives. The case is best couched in retrospect by a discussion between Peter Wright and his counsel, Malcom Turnbull, in pre-Spycatcher trial discussions in late 1986. Wright had argued to Turnbull that he believed that the involvement of Rothschild somehow gave a degree of official approval to his disclosure of information. Kenneth Rose quotes what Wright put on the record:

I knew Lord Rothschild to be an intimate confidant of successful heads of British intelligence establishments. I could not conceive of him embarking on such a project without knowing it had the sanction, albeit unofficial, of the authorities.

I sensed I was being drawn into an authorised but deniable operation which would enable the Hollis affair and other MI5 scandals to be placed in the public domain as the result of an apparently inspired leak.

All I know about Lord Rothschild and the ease with which ‘Their Trade Is Treachery’ was published leads me to the inescapable conclusion that the powers that be approved of the book.

Now this may have been sophistical cant, and Turnbull correctly was cautious. After all, had Rothschild not warned MI5 about Wright’s plan to write ‘vengeful memoirs’? Moreover, Wright was initially reluctant to drag his friend into the morass. Much later, however, Rothschild told his biographer about an influential friend who had visited him in hospital some time between February and April 1980. This visitor suggested to him the plan that culminated in the publication of Their Trade Is Treachery. Rothschild would not say who that figure was. Rose reasoned that it was probably Maurice Oldfield, partly because both Dick White and Robert Armstrong denied their own involvement when he spoke to them about it, and both suggested that it was most likely Oldfield, who had been the head of MI6 between 1973 and 1978. Yet it was perhaps unprofessional and dishonourable of both gentlemen to accept so quickly that there had in fact been such a leak, and to accuse someone who had never worked for MI5, and who was no longer around. Oldfield had conveniently died in March 1981.

I suspect the man was much more likely to have been Dick White himself. He had been a notorious, though vaguely anonymous, informant to Andrew Boyle behind the scenes, as Nigel West describes in Molehunt, in the chapter ‘Cover-up’. He had a dishonorable track-record of diverting attention to Hollis in the series of searches for traitors within inspired by the CIA’s noxious James Angleton, and adopted by Arthur Martin and Peter Wright. In fact he had a habit of casting aspersions on his professional colleagues (e.g. Liddell, Hollis, Oldfield, Rothschild) – but only when they were deceased and thus not able to counter the charges. Be that as it may, Wright’s action in going public with his claims, effectively ‘throwing Victor to the wolves’, in his own words, immediately brought some harsh attention from the press. In addition, Wright coloured his affidavit with so many untruths and misinterpretations that he caused his erstwhile friend a lot of grief. Rose may have been a bit too convinced of Rothschild’s essential innocence, since he deplored Wright’s evidence that Rothschild had thus lured ‘an innocent patriot into disloyalty.’ Wright was by no means an innocent patriot, but Rothschild was certainly one who loved intrigue and conspiracies, and manipulating matters behind the scenes, as Wright accurately portrayed him.

The central question still must be: why would Rothschild expose himself to the very serious charge of abetting someone to break the OSA, simply as a way of gaining publicity for a cause (the denigration of Hollis and the praise for Rothschild) that might distract from the negative publicity that Rothschild was receiving? After all, here was a man of some stature, known to have brought in a real mole into MI5, and now seen to have helped two dedicated molehunters, equally obsessed with unmasking Hollis, in publicizing their philippics! It was that conundrum that prompted Paul Greengrass, a member of Turnbull’s defence team (and the eventual ghost-writer of Spycatcher) to share his suspicions with the CIA that Wright and Rothschild had been encouraged to collaborate by MI5 (i.e. by Furnival Jones), and to use Pincher as the medium. In other words, the British Government wanted Their Trade is Treachery to be published. Yet, if that were true, Rothschild displayed a large amount of naivety in accepting the gauntlet, knowing that the act would be denied should accusations to that effect ever take place. In that situation, however, he would hardly have wanted to encourage and abet the struggling would-be author to bring his thoughts and memoirs to the printed page, and he would probably have preferred to let him fade away in rural Tasmania.

A further hypothesis was presented by Anthony Cavendish in his 1990 memoir Inside Intelligence. Maurice Oldfield had been outed by Chapman Pincher in 1987 as a practicing homosexual who had had his security clearance dropped in 1980. According to Cavendish, the only other two persons to whom Oldfield had confided his secret back then were Sir Robert Armstrong and Victor Rothschild. Cavendish speculated that Rothschild may have shared this knowledge with Pincher in an attempt ‘to take the heat off the Wright case’. Yet that strikes me as rather absurd. While it could be interpreted as the mirror-image of Oldfield’s encouraging Rothschild to pursue the Hollis disclosures as a means of diverting attention from his own predicament (see above), such attempts at distraction would probably have only raised the public’s interest in the obsessions of the authorities concerning secrecy, and their clumsy efforts in disinformation exercises. One can hardly imagine Rothschild’s using his friend in such a mean and petty fashion, even if Oldfield had been dead for six years.

The succeeding events can be read in Rose’s chapter ‘Spies and Spycatcher’. As I indicated before, the essence was that Rothschild had been brought to a measure of despair by the criticisms, and by a question in the House of Commons as to whether he had been the ‘Fifth Man’. He perhaps protested too much, looking for someone who might vindicate him, and point to his loyal service. He turned to his old friend, Dick White, but had become estranged from him. It is not a convincing tale. White told his biographer that he maintained close social relations with the Rothschilds in the 1970s, after he retired from MI6, and that he and Victor discussed and dissected MI5 ‘endlessly’ during the Whites’ visits to Cambridge. Why White should have been so indulgent to the Rothschilds, since he must have been familiar with the alarming information held in the MI5 files, is puzzling. He must have been very naïve, or simply complicit. And, if the two of them enjoyed endless congenial discussions about the predicament of MI5, it hardly seems likely that they would have stepped around the emerging Wright business.

White wrote to Kenneth Rose in January 1991 (i.e. the year after Rothschild’s death) that he had warned Victor, in the summer of 1980, to keep out of intelligence matters. “He was too close to Peter Wright. I told Victor that if this continued, Wright might ask him to do things that went too far and put him in danger. He resented my warnings and ceased to consult me.” Yet this was before Rothschild summoned Wright to England. Rothschild might have been trying to help Wright, but he was hardly ‘close’ to him any more. Why, at that stage, would the mighty Rothschild not have been able to resist any requests made to him by Wright? Moreover, since the revelations that Wright was threatening to disclose would embarrass White as much as they would Rothschild, it does not make much sense that White felt that he could simply distance himself from the whole project. White claimed that he had been offended when Victor did not consult him about the plot to bring together Pincher and Wright. Yet he would have had to say that, to protect his own reputation. White was almost certainly involved in the deception.

Later, Rothschild ended up writing a letter to the Daily Telegraph, published on December 5, 1986,requesting that the Director-General of MI5 ‘state publicly that it has unequivocal, repeat unequivocal, evidence that I am not, and never have been a Soviet agent’. That was absurd, histrionic, and illogical. Margaret Thatcher’s statement in response that ‘I am advised that we have no evidence that he was ever a Soviet spy’, was correct, as how could evidence to the contrary ever be collected? (Pincher would foolishly write that a record of Rothschild’s positive work for MI5 would have constituted ‘the unequivocal evidence’ he sought, forgetting that a similar statement might have been said about Philby.) It was not a vindication, but Rothschild had brought it upon himself. And the truth was more complex. Rothschild was never the ‘Fifth Man’. He had been careful never to purloin secrets and pass them on to an adversary, but he may well have been ‘an agent of influence’.

As a coda, Rothschild was required to submit to interrogation between January and April 1987, as a consequence of Wright’s testimony in the Spycatcher trial. The Serious Crimes Squad of Scotland Yard invited him to help with their inquiries in light of the fact it appeared that he had breached the Official Secrets Act. Remarkably, Rose’s account of the process is dependent largely on the records that Rothschild himself kept of the interrogations, and what he subsequently told his biographer of the proceedings. Rothschild did not acquit himself well, but then neither did his prosecutors. The latter had not challenged or inspected closely the truth of what Wright had said, and he was not about to come to the UK to give evidence in any trial. The outcome was predictable: the authorities did not want any further public laundering of their dirty washing. Despite Rothschild’s prevarications over his role, and the reputed introduction of Wright to Pincher, the Director of Public Prosecutions determined that there was no justification in bringing proceedings against Rothschild – or Pincher, who was also a subject of the inquiry.

Pincher’s Version

Pincher had a rather different take on the events. His opinion was coloured by a) the fact that Their Trade Is Treachery had not been quite the success he had hoped for, after Margaret Thatcher in March 1980 effectively dismissed his accusations against Hollis; b) his obsession over the guilt of Hollis; and c) his later irritation that Wright had broken off communications with him in 1984, probably because Wright had demanded some of the proceeds of Pincher’s following book, Too Secret Too Long, and had seemed committed to writing his own account of the affairs. He would probably mull ruefully over the fact that the mixture of truth and lies submitted by an insider (Wright, abetted by Pincher’s rival, Greengrass) had turned out to be commercially more successful than a similar medley by an outsider (himself). First of all, Pincher denied that there had been any secret deception project by which MI5 had conspired with Rothschild and himself to disclose truths that could not be stated publicly. When the publicity about the ‘Fifth Man’ crescendoed, Pincher misrepresented the controversy by first suggesting that the rumours emphasized that Rothschild had encouraged Wright ‘to give Pincher the information about Hollis so that the former MI5 chief would be exposed as the Fifth Man’, and then by demolishing this argument because Hollis had been at Oxford, and thus could not have been the last of the Cambridge Five.

He then disingenuously implied that he had been ignorant of the Hollis claims until Wright came along, claiming that Rothschild had known all about ‘the Hollis case as it unfolded in MI5 because Wright had kept him informed’Rothschild could (he wrote) have simply given the information to Pincher. Yet, as shown above, Rothschild did not believe in Hollis’s guilt, and Pincher had clearly been researching Hollis, with the help of Wright and others, long before the staged encounter in September 1980. Rothschild may have seen an opportunity to distract attention from himself, but it was not because he firmly believed in Hollis’s guilt, or that Their Trade Is Treachery was going to make a solid case about it. Pincher later described (in the chapter ‘Brush with the Police’, in Treachery) how Rothschild and he, while being interrogated separately ‘demolished Wright’s statements with insider table documents and facts’. How he knew how the Rothschild interrogations evolved is not stated.

Pincher had earlier expanded on the saga in his book A Web of Deception: The Spycatcher Affair, (1987) which is essentially a diatribe about Wright’s motives, activities, and pronouncements about the whole business, and a paean to the noble Lord Rothschild. (I discovered, acquired, and read this work only in the middle of August.) He offers a prolonged defence of Rothschild that is naive and misguided. He denies that Rothschild introduced Blunt to MI5, or that Rothschild was under surveillance at all after the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean. He attributes to Wright assurances that ‘Rothschild’s file in the MI5 Registry contained only material to his credit’, when, as my analysis below shows, that is simply not true. (How come your process of verifying what Wright told you did not work here, Chapman?) He is unable to imagine that his friend, with his ‘intellectual brilliance and flair for original thought’, could ever have done anything ignoble.

His main thrust, however, is that the authorities allowed Their Trade is Treachery to proceed out of a muddled concern for secrecy, rather than as an active conspiracy. Yet the volume is itself self-contradictory and evasive: for instance, the author claims that Rothschild was concerned about Wright’s ability to write his book in a professional manner when in fact the reason that Wright came to see him was because he felt physically incapable of writing the book himself. Pincher admits that the only texts that he brought from Tasmania were transcribed notes, and that Wright convinced him to mail them to friends in separate envelopes to avoid security detection. He states that it was Jonathan Aitken who first told him about Hollis, but not until the end of April, 1980. (And Aitken could not have known the whole story.) Pincher boldly declares that neither Arthur Martin nor Stephen de Mowbray had ever met him or given him any information. Dick White, on the other hand, openly stated that Wright had been Pincher’s primary source.

And his account of the final steps does not make sense. He absurdly claims that he was able to use the skills of a professional researcher (namely his son) to confirm most of Hollis’s information when he returned to London, and only then decided to write the book – something that must have taken additional weeks, of course. Elsewhere in the book, however, he sophistically states that, when he decided to write Their Trade is Treachery, ‘It was entirely as a means of placing on public record old history [sic!] which I felt to be in the national interest’ –pure humbuggery. Moreover he slipped up on several matters, such as the investigation by Lord Trend into the Hollis affair. How he was able to verify Wright’s claims, except perhaps by checking back with Wright’s old crony, Arthur Martin, is not stated. The book follows this vein throughout. In summary, A Web of Deception is exactly what the title says – but it was Pincher’s Web as much as it was Wright’s or that of the British authorities.

The conclusion must be that only a very detailed examination of the contrary claims in the testimonies of Wright and Pincher might lead to a clarification of what really happened. Too many lies were being told. Here were two charlatans, at daggers drawn, both with an unhealthily exaggerated and unmerited respect for Rothschild. That is beyond the scope of this article. The paradox is that Pincher’s role as an investigative journalist, in a world dominated by too much secrecy and by rules of confidentiality, is an extremely important one, but such a function has to be carried out with method, discipline and integrity. In that regard Pincher failed miserably. Yet it was Rothschild, after his clumsy and naïve foray into the world of investigative journalism, who was the person most harmed when his two admirers started to bicker and fall out. And White’s constant involvement with Rothschild, his own nervousness about what Wright might reveal, and his known desire to turn attention towards the hapless Hollis, all point towards his close collusion with Rothschild and Pincher. And that was the nub of the defence’s argument in the Spycatcher trial.

- Agent of Influence

I dedicated Chapter 6 of Misdefending the Realm to the topic of Agents of Influence, focussing on Rothschild, Gladwyn Jebb, and Isaiah Berlin. I explained that such persons were careful never to place themselves in positions where they could be accused of handing over confidential documents, but instead worked behind the scenes to influence domestic policy, or to facilitate the activities of genuine spies. In that role they could in the long run be far more dangerous. In that respect, I outlined how the three gentlemen identified above abetted the progress of Stalin’s Englishmen, especially that of Guy Burgess.

On pages 140-144 of my book I described many of the facts about Rothschild’s career that are sprinkled around this report, including more details about Liddell’s negotiations with him when Rothschild had been working on matters of sabotage and unconventional warfare, as personal assistant to Sir Harold Hartley, for the government department MI/R. I also referred to a letter (cited by Andrew Lownie in his biography of Burgess) that Michael Straight had written to the journalist Michael Costello, claiming that it was Rothschild’s ties with Soviet Intelligence that had driven him to fund Wright’s enterprise with Spycatcher in a way that would totally exclude any such analysis or innuendo. I pointed out that Straight’s accusations should not be accepted unconditionally, although it was his evidence that eventually unmasked Blunt. Yet it was Rothschild’s continued association with and support for former Cambridge ‘Apostles’, primarily Blunt and Burgess, when it should have been apparent that their behaviour was suspect, that would more permanently taint him.

Moreover, in recent years, evidence from Russia itself has reinforced the idea of Rothschild’s role as an influential agent of the Kremlin. In 2013, the memoirs of Ivan Serov, who led the KGB from 1954 to 1958, and the GRU from 1958 to 1963, were discovered, and published in 2016 (Zapiski iz Chemodana). Serov had been one of Stalin’s most loyal servants, and supervised many of the repressive measures taken by the vozhd. A vital entry in Serov’s diaries appears from the year 1956, when he accompanied Khrushchev to London, and met Rothschild. It runs (see https://espionagehistoryarchive.com/2018/03/27/victor-rothschild-soviet-spy/ .)

I met Victor Rothschild only once, at the Embassy. This person was well-known from very long ago as an ‘heir’ to the Philby affair and others. He knew perfectly well that these people, having certain inclinations, were connected to us, and used them to pass on information to Moscow, including false information.

Serov was not impressed with Rothschild, possibly because he distrusted the sincerity of his information leakage: he also suggested that the connection to Rothschild compromised the loyalty of the spies in Moscow’s eyes. Moreover, the creation of Israel put an end to his usefulness, since Rothschild started to take up a strongly Zionist stance. In fact, Stalin had initially supported such goals, until he soon realized that the ferment was encouraging separatist and divisionist leanings at home. Zionism and Stalinism were suddenly in opposition, and Stalin quickly turned against any Jewish resurgence in the Soviet Union. Serov finally dismissed Rothschild as a ‘fellow-traveler’, one rung down on the ladder of Communist sympathizers, probably just above ‘useful idiot’, and praised instead such allies as ‘Bernal, Ivor Montagu, and major scientists’. He considered that Rothschild was someone who simply followed his own goals rather than owning loyalty to any group or creed – probably an accurate assessment. That was a line that Jonathan Haslam echoed in his Near and Distant Neighbors (2015), where, using Victor Popov’s 2005 monograph on Blunt, Sovetnik korolevy, he stated that Rothschild provided cover for the Cambridge Five while ploughing his own furrow.

An intriguing footnote is offered in Mark Hackard’s article, namely that Theodore Mally recruited Rothschild at a concert in London in August 1934. That claim was made by a retired KGB officer, Victor Lekarev, who had worked in the London residency. In 2007, he had written an article characterizing Rothschild as the ‘sponsor’ of the Cambridge Five. It can be viewed (in Russian) at https://argumenti.ru/espionage/n40/33679 , and shows how Rothschild, on the recommendation of Kim Philby, was encouraged to accept a free ticket to a concert where he met Mally, and was then recruited for some role with the OGPU. If we can trust what Lekarev writes, it would have been the ‘Cambridge Six’ if Rothschild had been recruited as a penetration agent, but, if only as an agent of influence, it would indicate that he probably knew about the statuses of the original Five. In any event, owing to his connections with the political elite (and eventual membership of the House of Lords in 1937), Rothschild was thereafter privy to much confidential information, and was able to exert his influence even on Churchill, claims Lekarev, who clearly categorizes Rothschild as an ‘agent of influence’. In his profile, he also indicates that Rothschild was actually working at Porton Down on bacteriological warfare when war broke out, a fact that I have not been able to verify, although an entry in Rothschild’s MI5 Personal File does confirm that one of his roles was to advise MI5 on that very topic. Lekarev also stresses how important Bentinck Place was as a rendezvous and location for the passing on of secrets, a claim that is probably exaggerated.

The conclusion might be that Rothschild had such a high opinion of his own ability to manipulate events that he was not a durable ‘agent of influence’ for any institution. His evolving political philosophies (communist, anti-fascist, socialist, Zionist, conservative free-enterpriser) reinforced that unreliability. Yet his undeniable actions supporting and abetting communist infiltrators in the 1930s and 1940s ensured that he did indeed play a malignant role helping Soviet goals in that critical period.

- Zionism

Rothschild’s reputed support for Zionism has a dubious pedigree. After all, the Rothschilds were a prime example of a well-assimilated family, and Victor in many ways became a quintessential landed Englishman, augmented by his expertise at cricket and golf. He was a non-believer: Rose wrote that ‘he looked on religious belief with the confident agnosticism of a Victorian freethinker, a Huxleyan rationalist’. His first wife, Barbara Hutchinson, was not Jewish, and it was on the insistence of Victor’s grandmother that Victor’s fiancée converted to Judaism before the marriage, so that any offspring would be ‘Jewish’ (that attribute traditionally passing through the mother.) I find that doubly absurd: the notion of some racial-tribal identity being transferred through such an arrangement, and the obvious hypocrisy of a woman’s swiftly changing her religious beliefs to appease a misguided matriarch.

Being assigned the role of some figurehead for British Jews did not always suit Victor. In December 1938, after the assassination of Von Rath in Paris, he did write to the Times about the plight of persecuted Jews in Germany. Roland Perry, citing with apparent authority Guy Burgess’s KGB file No. 83792, declares that Burgess wrote to Moscow Centre in December 1938 to say that his boss in D Section, Lawrence Grand, had given him the task of activating Rothschild in a tactic to split the Jewish movement by creating opposition to the Zionists, who were represented by Chaim Weizmann.

On July 31, 1946, Rothschild gave a noted speech in the House of Lords in the wake of the Irgun terrorism in Palestine, specifically the murdering of ninety-one persons in the King David Hotel bombing. Rose dismisses it in one brief sentence as ‘a courageous but embarrassed attempt on his part to explain the historical background to the Palestine conflict and the murder of British soldiers by the Stern Gang’. Yet it was an equivocal and dishonourable display that calls for deeper analysis.

Rothschild started off by identifying the conflict he felt as a recent member of the British Army. “It was only a few months ago that he was a British Army officer”, he said. Yet he spent the war in MI5, and did not see combat (“even though one may not have been very near the front line”). “No Jew”, he continued, “can fail to feel despair and shame when confronted with the stark fact that his co-religionists . . . should have been responsible for the deaths of British soldiers”. “Co-religionist” is the language of a Foreign Office mandarin, not of a Jew, and in any case Rothschild himself demonstrated that not all Jews are Judaists. He next described his attitude towards Zionism, saying that he had never been a supporter of Zionism, or political Zionism (whatever that meant), and that he had never been associated in any way with Zionist organizations.

Yet he then effectively made a plea for the Zionist cause, assuming that he could accurately generalize about the mentality of ‘the Jews’ in Palestine. “Palestine”, he declared, “is the only country where the Jews, after 2000 years, have been able to get back to their business of tilling the soil and living on the land”, forgetting perhaps that the Rothschilds, in England, if not actually ‘tilling the soil’, had been able to live comfortably on their landed estates, and instead echoing the oversimplified trope about the Jewish diaspora. (Rothschild’s interests in soil-tilling were rewarded by his being appointed chairman of the Agricultural Research Council in September 1948.) Rothschild regretted that ‘the Jews, having found the Promised Land’, find their fields are ‘burnt and ravaged by gangs of marauding Arabs’. His plea sounds like an apology for terrorism and murder, and is unworthy. Moreover, his final statement was to sit on the fence: “I do not entirely share the aspirations of the Jews in Palestine”, as if he conceded that the displaced Arabs, who probably considered that the fields were ’theirs’, might be justified in their grievances about increased immigration, although he did not say so. It was not a very noble performance by the noble lord. It probably derived more from clumsiness than from deviousness, but Rothschild’s opinions were rapidly evolving at this time.

Rothschild’s House of Lords speech was designed as a response to the government’s recent proposal to split Palestine up into four areas, and allow 100,000 European Jews to be settled in the ‘Jewish Province’. In 1947 the United Nations Partition Plan was adopted, and in May 1948 Britain abandoned its mandate. The agency chartered with managing security in Palestine was the cross-departmental unit based in Cairo, SIME (Security Intelligence Middle East), led by an MI5 officer. When Palestine cased to be a British territory, however, responsibility for gathering intelligence in Israel/Palestine shifted uneasily from MI5 to MI6, and that had serious implications for Rothschild as well, in relation to where he tried to exert his influence. His views may well have been evolving to a more pro-Zionist stance: according to Christopher Andrew (p 364) Kim Philby was an energetic supporter of the terrorist campaigns as a way of undermining British imperialism in the region, and Rothschild may have owned a similar perspective. A note in Liddell’s diary dated January 22, 1948, reports that Rothschild had been dealing with Chaim Weizmann, the prominent Zionist publicist, who was becoming frustrated in his attempts to gain access to Attlee. Rothschild had advised Weizmann not to go straight to Churchill instead: furthermore, the Government was much more interested in ‘fixing things up with the Arabs’. (An intercepted conversation between Burgess’s mother Mrs. Bassett and Blunt from 1956 discloses that Weizmann had vigorously tried to convert Rothschild to Zionism, when Burgess had argued strongly against it, but the event was not dated. Blunt told Tess that he thought the debate had occurred ‘during the war’ at the Dorchester hotel.)

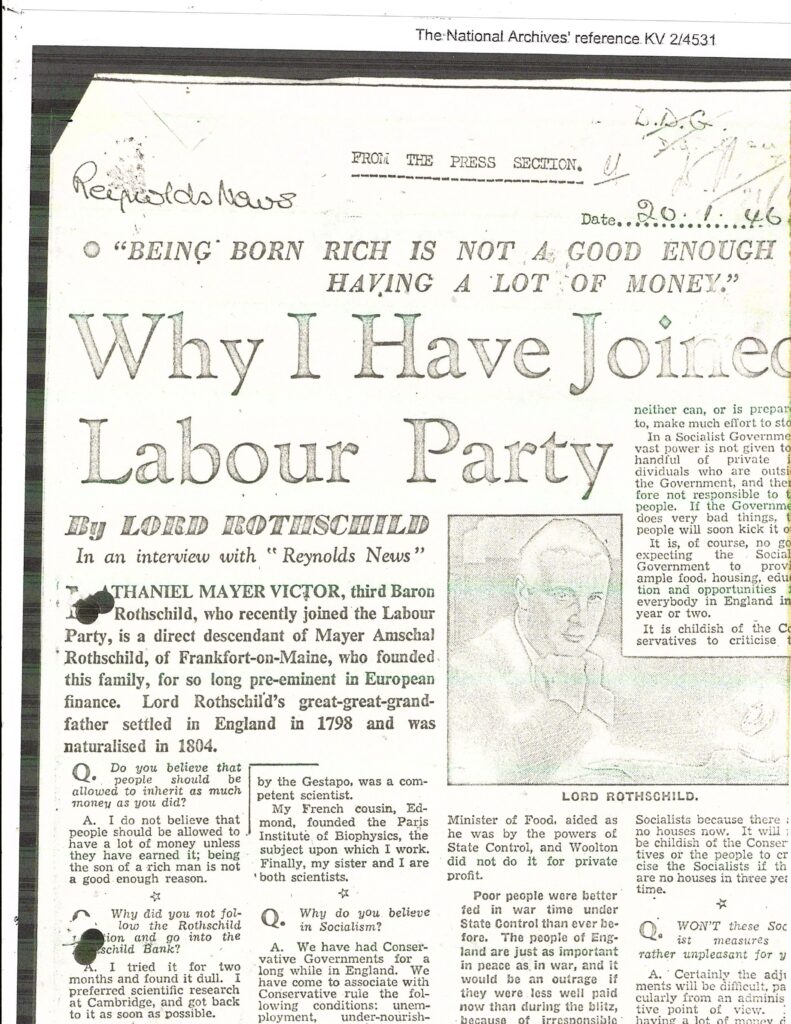

For Rothschild had by then very openly changed his political affiliations. On January 20, 1946, he had made a very pompous public declaration (in Reynolds News) that he had joined the Labour Party. “We [ = who?] have come to associate with Conservative rule the following conditions: unemployment, undernourishment, unpreparedness, unpopularity abroad, unequal pay, education and opportunities, undeveloped resources, and lack of opposition to Fascism.” Given that a coalition government led by the Conservative Churchill had just concluded the war against Hitler, and that the United Kingdom had been the only country in Europe not to have been occupied by the Axis powers or to have declared neutrality, this was another ill-mannered, provocative and ingenuous statement that for some reason did not materially harm Rothschild’s reputation among the elite. He was gently rebuked by Petrie, since his political utterances might be in conflict with MI5’s neutrality on such matters, but Sir John Anderson wanted to keep him on, leaving it to his lordship’s judgment. (Why Anderson was influential at this time is not clear, since Churchill’s administration had by then been replaced by Attlee’s.) Rothschild resigned from MI5 on May 7.

- MI5 & MI6 Postwar

MI6 records are of course not available. In MI6: Fifty Years of Special Operations, Stephen Dorril limits his references to Rothschild to his role as a conduit used by MI6 to pass on payments to the editors of Encounter. Guy Liddell’s Diaries offer a few insights into Rothschild’s involvement with MI5 after his resignation. I recall Peter Wright’s comments about Rothschild’s ‘intimate connections with the Israelis’, and wonder how serious Rothschild’s anxieties were at having his telephone tapped. Maybe MI5 knew of such relationships, and Rothschild was joking. Wright also referred to Rothschild’s work for Dick White and MI6 in the late nineteen-fifties, but these likewise represent murky goings-on. In his testimony in Australia, he stated that Rothschild had been involved in the MI6 plot to overthrow Iran’s Mossadeq. The excerpts available from Liddell are fragmentary, and do not by themselves offer a very cohesive narrative, so I simply record them in sequence.

Even before the war was over, Rothschild seemed to be plotting with Kim Philby for a future with MI6. On March 7, 1945, Kim came to Liddell, saying that he was anxious that Victor should work for Section 9 (his new counterpart-intelligence organization) while in Paris. Indicating that he already had approval for such a scheme (presumably from Menzies), Philby claimed that Rothschild had some very valuable contacts in the French capital, some of which had already proved to be useful. Liddell sounded guardedly alarmed, and promised to look into the matter. Two weeks later, having discussed the matter with Bobby Mackenzie (of the Foreign Office), he told Philby that it would not be a good idea. He minimized the value of Rothschild’s personal contacts (‘French officials’), and pointed out that Victor still had much to do with building up intelligence at home. His final comment was, however, again cryptic: “ . . . It was particularly important that Victor should not run paid agents in France, not because he would not do the job admirably but because it would spoil his usefulness if there was any sort of come-back.”

Whether Rothschild’s changing political views were related to the successful deployment of atomic weaponry, and the subsequent end to hostilities, is not clear. In May 1945, he had been occupied training the British Control Commission in Germany on counter-sabotage techniques, but when he returned home, he immediately started busying himself with scientific research. The Joint Intelligence Committee had proposed that efforts on scientific intelligence-gathering should be increased, and on June 29, Guy Liddell suggested to Stewart Menzies, the MI6 chief, rather cryptically that ‘there might be a place in all of this for Victor, both on the offensive and defensive side’. Liddell discussed the opportunity with Rothschild when he returned on July 31, Victor stating that MI5 had been too passive. In any event, Rothschild became very interested in the Nunn May case (concerning the passing of atomic secrets to the Soviets) when it blew up in September, and managed to join a highly-select committee to discuss security over atomic matters, strongly arguing that such aspects were not being addressed aggressively enough. How sincere his motivations were in getting close to the hub of affairs is not clear: on October 2 he downplayed his interest when speaking to Liddell, suggesting instead that he would tidy up some affairs and then write a history of his B1c unit.

On November 1, however, he renewed his vigorous campaign, saying that Wallace Akers, the director of the Tube Alloys project, was not taking security seriously enough. A month later he shifted his position, declaring to Liddell that he would more effectively work informally, exploiting ‘his own personal high-up contacts’, while accepting that such an approach would require the approval of some higher authority. What it appeared he wanted to do was highly irregular – snooping around in the laboratories to find informants who knew the political leanings of scientists like Nunn May. Was this a defensive move prompted by the threats to other spies? Such an idea should not be discarded completely. By mid-January 1946, it seemed that he was being successful. Petrie had approved Rothschild’s idea, and had agreed to write letters to Sir John Anderson and Edward Bridges to allow Rothschild to carry out his inquiries, the subjects of which include some novel uses of uranium that he hoped to learn from Lord Cherwell. And then, on May 9, Rothschild wrote a letter to Harker suggesting that his official connection with MI5 should be severed, while ‘he would of course remain at our disposal as adviser on scientific matters’. That was a generous gesture! He presumably had gained the authority he needed. Indeed, Liddell recorded in his diary on May 22 that the irritating pamphleteer Kenneth de Courcy was suggesting that Rothschild now had some kind of mandate from Menzies, the MI6 chief.

One of the most intriguing incidents at this time concerns Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, a controversial figure suspected of fraud in many exploits. He was the uncle of Tess Mayor, Rothschild’s assistant (and eventual wife), but he also lived with Teresa (‘Tess’) Clay, a woman much younger, who assisted Rothschild on the ‘Fifth Column’ project with Eric Roberts. Clay was also a close friend of Victor’s sister, Miriam. Thus the connections with the Colonel were tight: Victor considered him a close friend. In November 1946, Clay reported to Guy Liddell that a representative from Irgun had approached Meinertzhagen, saying that the group would not execute any terrorist activities on British soil for fear it would jeopardize its fund-raising opportunities. Liddell noted that Meinterzhagen was known to possess sympathies with ‘Zionist revisionists’, a group which promoted expansion of Jewish settlements – even beyond the Jordan River.

Rothschild’s name does not appear for some time, but on September 24, 1949, when reports arrived indicating that the Soviets had successfully detonated an atomic bomb, he provoked a bizarre entry in Liddell’s Diary, which is worth quoting in its entirety: “Dick [White] saw Victor last night. The latter shares my scepticism about the Russian atomic bomb. He also takes the view very strongly, largely based on communications with Duff [Cooper], that a resurgence of Right Wing parties in Germany is the most serious menace at the moment. He thinks it might well lead to a tie-up with the Russians. Winston, I gather, takes a contrary view.” The ingenuousness and inanity of such utterings are bewildering. Klaus Fuchs’s confession was just about to burst out. On February 21, 1950, Menzies told Liddell (completely off the record) that he didn’t think the Russians had made an atomic bomb – an extraordinary admission from the head of MI6.

Yet Rothschild continued to snoop around, exploiting his previous rank and respectability. On January 27, 1951, he turned up at Liddell’s office, requesting a list of officers involved on atomic research. Liddell noted that ‘he will show it to Hans’ (i.e. Hans Halban, another shady character of dubious loyalty.) And there the record peters out. A few entries concern Rothschild’s behaviour in connection with the Burgess/Maclean fiasco, and I shall incorporate them into my study of Rothschild’s Personal File below. He was also involved with Liddell’s attempt, early in 1953, to find the spy Nunn May a job after the scientist was released from prison, but I do not believe his actions therein are of importance.

Overall, it seems that Rothschild transferred his allegiance to Menzies after his resignation from MI5, but facts about what he really accomplished are hard to find. For instance, rather alarmingly, Wright described Rothschild’s involvement with MI6 in these terms: “He maintained his links with British Intelligence, utilizing his friendship with the Shah of Iran, and running agents personally for Dick White in the Middle East, particularly Mr. Reporter, who played such a decisive role in MI6 operations in the 1950s.” Kenneth Rose, on the other hand, links Reporter, an important middleman to the Shah, to Rothschild only in the late 1960s, when Rothschild was head of Research at Shell, and was pursuing regular commercial opportunities in Iran. It sounds all rather careless and undisciplined to me. I notice that Stephen Dorril offers a contradictory comment about Sir Shapour Reporter, who worked for the Indian Embassy in Tehran, but ‘did not, as has been suggested [?], play a role in any operations’. He also records how enthusiastic a supporter of the Israeli cause Rothschild had been, but offers no details. Liddell’s diary comes to an abrupt close in May 1953 when he discovers that White has been appointed the new Director-General of MI5.

- The Kew Archive:

Introduction

The files on Victor and Tess Rothschild (née Tess Mayor, known at Cambridge as ‘Red Tess’ because of her communist sympathies, whom he married, as his second wife, in August 1946) fall into two primary tranches. The first section primarily covers the period immediately after the abscondence of Burgess and Maclean in May 1951, and gradually peters out in 1956. After a brief flurry because of the Flora Solomon disclosures in 1961, the story picks up in early 1964, after Anthony Blunt’s confession, and exploits Tess’s close relationship with Blunt. This investigation carries on for several years, with new teams of officers brought in, before running out of steam in 1973, with an inconclusive but overall favourable verdict. Thus, if the earnest researcher was hoping to find here a comprehensive description of the Rothschilds’ interactions with the authorities, he or she will be disappointed.

What intrigues me is that the first entry in Rothschild’s Personal File (PF 605,565) consists of a letter created on March 21, 1951, in other words well before the disappearance of the pair who came to be known as ‘the missing diplomats’. It is a relatively harmless item, representing a communication from Victor to Guy Liddell and concerning the suitability of a Professor Collier, whom Rothschild knew as a Communist from his Cambridge days, for a position at the Agricultural Research Council that Rothschild headed. Yet it obviously caught someone’s eye (that of Liddell himself?). The letter could be interpreted as a diversionary exercise by Rothschild, as an attempt to convince his former boss of his anti-communist credentials while the investigation into the leakages in Washington, resulting in the suspicion that HOMER was Maclean, was heating up. The letter was probably inserted into the file when it was created, probably in May 1951. The PF number and the date the letter was written (not when it was received) appear in the structure of a red stamp, with room for a signature, a date, and a target, as well as a note that the letter should be copied into PF 46,567 – that, presumably, of Collier himself, whose file has never been released. Liddell’s rather weak and equivocal response is also included.

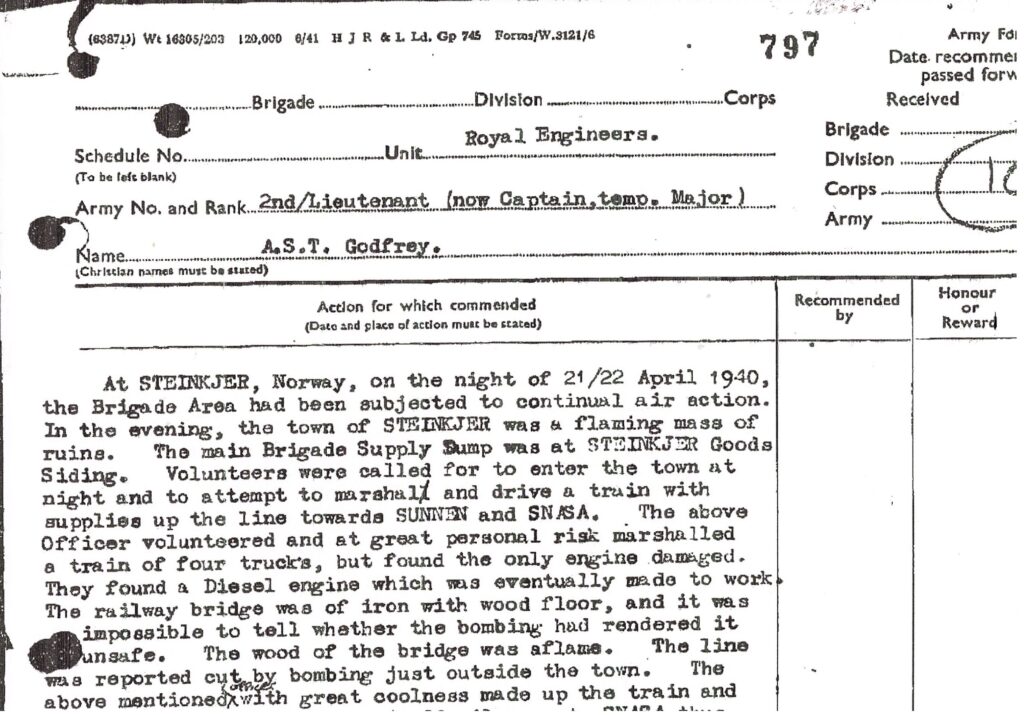

This is not the earliest entry in the file: others go back to 1940. Most are simply extracts from Rothschild’s personnel file at MI5, or other Security Service memoranda, recording such events as his introduction to MI5 by Liddell in May 1940, Victor’s own recommendation of Tess two months later, and his resignation in May 1946. His introduction of Anthony Blunt to Liddell is noticeably not included, although an important annotation by John Curry was inserted in September 1969. While Rothschild stated on his personal record form that he had been introduced by Guy Liddell, Curry pointed out that the lead for Rothschild had been orchestrated by a scientist and Trinity College contemporary, A. S. T. Godfrey, a friend of Brian Howard, who had recommended him to Curry. Godfrey was killed in action in Norway in 1942: it is not clear why Rothschild concealed this connection.

It is true that two further items from 1940 include the ‘PF 605,565’ stamp, but since the PF numbers were created sequentially, 605,565 belongs to the 1951 era. The two items (on Geoffrey Pyke, PP 983, and Claud Cockburn, 41,685) must have been copied from the original files at the time the Rothschilds’ file was being created. The Pyke item, especially, is of considerable interest, and I shall return to it later in this piece. Some items have been dredged out of much earlier files.

I identify several themes in the material on the Rothschilds:

i) The quite extraordinary level of surveillance, consisting of phone-taps and interception of mail, that was undertaken. It was not authorized against the Rothschilds directly, but they would have been extremely shocked had they learned of it. Yet MI5’s reaction was very sluggish.

ii) The readiness, under gentle pressure, displayed by Victor and Tess to make suggestions about possible Communist sympathizers they knew – especially at Cambridge.

iii) The high degree of self-importance and sense of entitlement shown by Victor, and the unjustified deference paid to him, especially when Peter Wright joins the team.

iv) The contradictory verdicts on Guy Burgess expressed by Victor, deprecating him one moment, the next having to admit that he used him as a financial adviser – a most unsuitable arrangement – and Victor’s highly dubious, even criminal, behaviour concerning investment tips.

v) Tess’s very provocative friendship with Anthony Blunt, and her duplicitous remarks concerning her awareness of his confession.

Surveillance

From what Peter Wright reported (see above) Victor Rothschild may not have been surprised by the fact that some of his mail had been intercepted, and his telephone chats occasionally tapped, but it appears that the surveillance was initiated vicariously. The activities of Guy Burgess were followed carefully in May 1951, and Blunt was one of his regular contacts. Thus a Home Office Warrant was requested for Blunt after the ‘diplomats’ disappeared, and the Rothschilds turned up frequently on the antennae, both in correspondence and on the telephone. This process went on for over ten years, and the warrant should thus have been renewed constantly. Furthermore, letters sent by Rothschild to Burgess from before the war were found in Burgess’s flat, as well as correspondence from Goronwy Rees that mentioned Rothschild, thus encouraging MI5 to believe that Victor and Tess might be able to help them with their inquiries. Kim Philby mischievously brought up Rothschild’s name as a close confidant of Burgess when he was interrogated. So did David Footman, when he was interviewed. It is possible that the Rothschild were on their guard whenever they spoke to Blunt, as Victor would have known how the Watchers operated.