Chapter 1

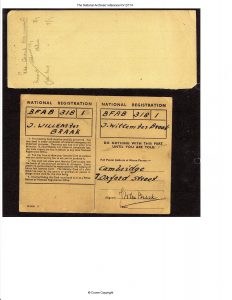

A G.P.O. detector-van, circa 1925. Note the well-camouflaged postilion on the roof of the vehicle.

The successful invasion of France by the Allied Forces in May 1944 was achieved largely because of the successful project to mislead the Germans about the planned landing site – the Pas de Calais rather than the actual beachhead in Normandy. Operation OVERLORD was a winner because of Plan BODYGUARD and the latter’s Directive for FORTITUDE. Yet the ability of the Abwehr – and hence the Wehrmacht – to be deceived so comprehensively by the group of double agents recruited by MI5, and run by Britain’s Double Cross (XX) Committee, opens up the management of these agents to some searching inspection. The relentless question, posed by many historians of this period, can be expressed essentially as follows: Why did the XX Committee allow such intensive wireless transmissions (especially from agent GARBO) to take place, knowing that any respectable interception agency would have located them and arrested the operators?

The Strategic Dilemma

In last month’s blog, I started analyzing the statement by Sir Michael Howard, the author of Volume 5 of British Intelligence in the Second World War (‘Strategic Deception’) concerning the challenges the Abwehr faced in exploiting its agents in Britain. Howard wrote: “The most satisfactory channel was radio transmission, but for this three problems had to be solved. First, the agents had to be provided with transmitting and receiving sets, and after June 1940 this was easier said than done. Secondly their missions had to evade detection by the security authorities; and finally they had to communicate in a secure cypher.” What were Howard’s sources in divining this strategy?

Howard was strangely subdued as to how the Abwehr went about its mission, or how the German intelligence service overcame these supposed challenges. He records a few sporadic observations, and refers to Professor Sir Harry Hinsley’s and C. A. G. Simkin’s Volume 4 (‘Security and Counter-Intelligence’), which also writes about the XX Committee, but says little about Abwehr strategies. As I have pointed out before, it seems that the authors of this volume did not want to engage the technical challenges too energetically. The discussion of such is relegated to a very amateurish and inadequate Appendix 3 (‘Technical Problems Affecting Radio Communications by the Double-Cross Agents’), written by an anonymous ‘former MI 5 officer from his personal experience’, which only skims the surface of the intricate subterfuges and negotiations that were undertaken to allow the agents to communicate with their supposed controllers in occupied Europe.

In fact the wireless strategy of the Abwehr was haphazard, tentative, and frequently incompetent. At the end of 1940, when the main wave of agents arrived on UK shores, mainly by parachute, most of the spies were equipped only with transmitters, not receivers, as they were planned to be used only as temporary informants before the imminent invasion. Howard’s description of the Abwehr’s objectives thus misrepresent its intentions. The chances of a heavy wireless set, strapped to the parachutist, surviving the fall from a low height, were not considered healthy. When one of the surviving sets (belonging to Wulf Schmidt, agent TATE) was at last made operable, the Abwehr gave advice for charging it up from motor-cycle batteries that, if followed, would have burned the valves. When Lily Sergueiev (agent TREASURE) was, after an inordinate amount of bureaucratic muddle, finally given her visa by the Abwehr to leave France for Madrid, as late as October 1943, her advised method of communication was still invisible ink, even though she had been trained in wireless operation. The acquisition of agent GARBO’s (Juan Pujol’s) wireless set had to be arranged by MI5: TREASURE likewise had to convince her Abwehr boss that she could go to Lisbon to pick up a set, under cover of being employed by the Ministry of Information. Agent BRUTUS (Roman Czerniawski) appealed to his controller to send him a more powerful transmitter, but the Germans prevaricated. It was as if the Abwehr only very late in the war considered seriously the use of wireless as a means of communicating intelligence.

The British, on the other hand, as they started to realise that the double-agents could be used more for strategic deception than simply gathering information about the enemy’s intentions, concluded that critical information needed to be forwarded in a timely fashion. Letters with invisible ink or microdots, sent to intermediaries, simply took too long, and the XX Committee thus inveigled the Abwehr into more intensive use of radio. Yet this was a very delicate path to follow, for the double agents would have to deploy their wireless sets as if the whole exercise had been initiated by the Abwehr itself, complemented by the ingenuity of the spies themselves. Thereafter, once radio communication had been set up, the XX Committee, and the officers of B.1.a of MI5 who controlled the agents and liaised with the Radio Security Service (RSS), had the outwardly conflicting goals of a) ensuring crisp and reliable communication between the agents and their handlers, and b) pretending that their powers of radio-detection and location-finding (generally known as ‘D/F’, for ‘direction-finding’, even though the term does not explicitly include ‘locating’) were so poor that their own agencies were incapable of intercepting the transmissions and hunting down the culprits.

One can thus present the dilemmas faced by the architects of strategic deception as follows:

- The authorities had to ensure that no unauthorised enemy transmissions were made from UK soil. Hence good detection and direction-finding were paramount.

- They had to be confident that the Abwehr trusted the communications of their agents and that they were kept in place providing ‘useful’ information. Hence D/F had to be shown to be inadequate, or extraordinarily imaginative transmission techniques, masking location, or using wavelengths close to dominant broadcasters, had to be used.

- At the same time, MI5 had to discourage illicit broadcasts by embassies and governments-in-exile, since information might be passed on that would undermine the ‘bodyguard of lies’ being woven by the official deception agency. In order to do this, an effective interception and D/F operation had to be managed.

- Thus all illicit broadcasts, by such agencies, or by rogue private operators, had to be shut down. If news of this got out, the Abwehr would no doubt hear of it, which would lead them to conclude that the operation was an effective instrument of surveillance. How, therefore, could the Abwehr be convinced that the British D/F operation made sense?

- The British experts needed to keep informed about the capabilities of the Nazi D/F operation. This process would mature soon, when SOE, the Special Operations Executive, started up its insertion of wireless agents into France, Belgium and the Netherlands, and later in the war when the shared Soviet-British espionage network in the neutral territory of Switzerland was pinned down by Gestapo technology and silenced in 1943. Would the Germans not assume that its enemy’s capabilities were as advanced as its own? Thus the XX Committee, abetted by the RSS, focused on such practices as reducing radiation emissions as far as possible without weakening the signal so much that it could not be picked up across the Channel.

- Meanwhile, doubts lingered over the efficacy of the domestic interception operation. RSS was known to be very capable at locating, fairly broadly, transmitting stations in occupied Europe. It also gave great assistance to the MI5 in testing the strength of agents’ signals when the location of the transmitter was known. But how good – or committed – was it at detecting all other sources (such as the Communist transmitters that MI5 was nervously following)? If known operators could bypass RSS detection, what unknown agents were doing the same? This knowledge of undetected transmissions (some acknowledgeable, others not) increased suspicion of the efficacy of RSS processes.

This chapter starts to explore the evolution of this tangled operation. The official histories provide little guidance: there is no comprehensive account of the RSS organisation outside some mainly affectionate memoirs. Frank Birch’s multi-volume history of British Sigint is opaque, and often self-contradictory: it is overloaded with obscure organizational subtleties, and fails to make crisp conclusions. Some facts can be gleaned by a close inspection of the agents’ folders at the National Archives: occasionally a fascinating handwritten note of ‘Copy to Wireless Folder’ can be seen on documents, but no such Folder has been released. Several documents listed in the Indices of the agents’ folders have been plainly destroyed (some entries having a line through them with the descriptor ‘DEST’!). Yet enough tidbits of information can be gathered from the National Archives, including the unedited (but redacted) original of Guy Liddell’s very revealing Diaries, to indicate that the challenge of masking the D/F operation was taken very seriously by some intelligence officers. Strangely, however, many reckless decisions were made, too, that could have jeopardized the whole campaign.

Four Phases

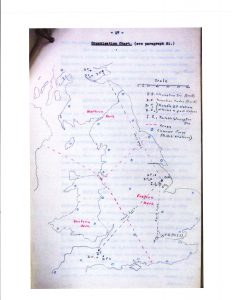

I have divided the period in question into four segments. The divisions are in some respects arbitrary, but they do delineate some clear shifts in trends, and in the conduct of the war (up to the Normandy landings).

Phase 1: Learning the Ropes (September 1939 to the end of 1940):

This phase is characterised by a fear of invasion, and of supposed ‘Fifth Columnists’ assisting it. It is a period of organisational dysfunction, with no clear command over the personnel and technology required to intercept illicit transmissions, or the detection of strategic wireless communications from overseas. British Intelligence quickly learns, from its experiences with the suspected triple agent SNOW, and the rather undisciplined attempts by the Germans to land spies in the UK, the lessons deriving from analysis of radio traffic, and the role of detection-finding. The W Board and the XX Committee are set up as a structure to explore ways of handling double agents, but by then MI5 is losing control of an important asset with insights into the problem of interception.

Phase 2: Conflicts and Tensions (January 1941 to June 1942):

Organisational change brings improved management and leadership to MI5, but the placement of RSS under SIS (with which MI5 was initially happy) leaves the Security Service with a sense of lost control. SIS’s tightness over security means MI5 does not receive the decrypts it regards as essential to the task of running its double agents, and RSS’s mission shifts more to overseas work. Both MI5 and SIS try to deal with their prima donnas. Even the Controlling Officer of Deception faces political attacks. RSS is outwardly cooperative in direction-finding, but MI5 questions its ability and commitment to the Security Service’s aims. The situation regarding the Soviet Union is clarified by its entry to the war as an ally, but is then complicated by the wireless activity of Soviet spies.

Phase 3: From Defence to Offence (June 1942 to May 1943):

Progress is made: Masterman persuades the head of SIS to release decrypts to the XX Committee, and he confidently declares that the operation controls all German spies. The new Controlling Officer of Deception (Bevan) brings energy and imagination to the overall deception plans for OVERLORD: the strategy for double agents evolves to using them to mislead the enemy about the proposed landings in Europe. Knowledge of Abwehr communications has increased. With the arrival of GARBO, the XX Committee develops plans to expand the usage of wireless telegraphy among the agents it is controlling, as the method of communication will be faster, and more reliable.

Phase 4: High Stakes (May 1943 to June 1944):

As the pressures on the security of the Double-Cross operation increase, doubts surface. MI5 expresses anxiety about RSS’s abdicating monitoring of Army transmissions, a loophole the Abwehr seems to be aware of. Gambier-Parry, head of Section VII in SIS, is not fully trusted. Concerns intensify about the volume of traffic being sent, but that remain undetected by British surveillance. Concerns are expressed about rumours of suspicions within the Abwehr about the reliability of their spies in England. Interception of Abwehr messages, however, appears to confirm that the messages of the double agents are overall being trusted. Transmissions by third parties (embassies, Soviet spies and visitors) alarm MI5, which reflects on its technical lack of expertise. While periods of radio silence have to be imposed, the double agents (especially GARBO) continue to send long-winded messages, remaining on the air for hours. Yet the deception is successful.

This chapter covers Phase 1. The other Phases will be examined in future postings.

RSS & The Fifth Column Threat

For the first nine months of the war, MI5 was focussed almost entirely on the risk that a Fifth Column, taking its instructions from German radio broadcasts, might aid the Nazi invasion when it came. The Germans had set up several radio stations broadcasting in English, of which the New British Broadcasting Station was the most prominent. Apart from the obvious propaganda in its messages, MI5 believed that the signals included coded instructions that subversive refugees – and ardent British Union of Fascists – would decipher. The Security Service even believed that some privately-owned transmitters were sending information back to their masters, even though the use of unregistered transmitters was illegal. Prime Minister Chamberlain chartered his Minister Without Portfolio, Maurice Hankey, with investigating such leaks, and in November 1939 a new unit, MI8(c), was set up to take over responsibility for wireless interception from MI1(g). Guy Liddell, head of Counter-Espionage in MI5, did not think anyone was taking the matter of disguised radio codes seriously enough: no one – neither MI8, nor GC&CS, nor SIS, nor MI5 itself – was adequately equipped or motivated to assume the work.

The problem endured into Churchill’s administration, which took over the reins in May 1940. Ironically, Churchill was the most vehement about the Fifth Column threat, installing a new layer of management over the intelligence services, and firing the veteran head of MI5, Vernon Kell. An apparently valuable expert in telecommunications and cyphers, Lt.-Colonel Simpson, had recently been lost from the service. As a possible replacement, an officer from the BBC, Malcolm Frost, who started to work with Liddell, reinforced the claim that the NBBS was sending coded messages to subversives, and Frost probably saw an opportunity to enter the limelight by taking on the challenge of deciphering them. Yet, by the spring of 1940, the RSS (the Radio Security Service) had concluded that the lack of domestic wireless transmissions suggested that the threat from a Fifth Column was minimal. It came to these conclusions in an imaginative fashion, but the logic behind that judgment was to come to harm relationships between SIS (to whom RSS eventually reported), and MI5, responsible for domestic security.

The exact origin and identity of RSS are murky, some accounts suggesting that it was subsumed into MI8(c), and in fact became the bulk of that section, which officially reported to the War Office – a clash between militarism and amateurism that would lead to later tensions. (Please see SoniasRadioPart2 for a fuller account of the origins of this unit.) Some official archives suggest that RSS had been set up in 1938, and was a team composed largely of Voluntary Interceptors – amateur radio hams – who watched the ether for unusual signals, and a team of mobile direction-finding units nominally reporting to the General Post Office. That latter part is clearly true, but Frank Birch’s Official History of British Signals Intelligence indicates that, when the financial approval for an organisation called IWI (Interception of Illicit Wireless Communications) was granted in March 1939, that unit was soon named MI1(g), later reassigned MI8(c), and that the definitive organisation permanently known as RSS developed under MI8(c)’s control. (Some archival documents tantalisingly refer to an entity titled the ‘Radio Section’, as if it had been a department of M11g, and then lent its name to the larger organisation.) Internal MI5 documents, such as Dick White’s Notes for Counter-Espionage Training in 1943 (KV 4-170), strongly assert that RSS was set up only at the outbreak of war. In any case, the section known as RSS had moved to Wormwood Scrubs, in the same building as MI5, in September 1939, and thus enjoyed close collaboration with MI5’s officers while keeping its separate identity. The official history informs us that the completion of the transfer from MI1(g) did not take place until November.

The critical conclusion that RSS made was based on the interception of transmissions from the German intermediary ship, the Theseus. The relevant sentences from Hinsley’s history are worth quoting in full: “The organisation responsible for the interception of illicit wireless transmission, the future RSS, continued to be controlled by the War Office – by MI 1(g) till November 1939 and by MI8 (c) after that date – with the GPO acting as its agent for the provision of men and material and the maintenance and operation of the intercept stations. By the outbreak of war its headquarters staff had been located close to GC and CS, which was to be responsible for cryptanalytic work on the intercepts, and it had finally established the beginnings of a network with the decision in March 1939 to establish three fixed and four mobile stations and the recruitment, from June 1939, of an auxiliary observer corps of amateur radio enthusiasts. But it had listened in vain for transmissions from the United Kingdom – in vain because it was still the case that no transmissions were being made apart from those on Snow’s set which was operating under MI5’s control. Since Snow’s signals had not been heard before MI5 took control of him, the failure to intercept others was understandably attributed to the inefficiency of the watch or to technical problems, notably the difficulty of picking up low-powered high frequency signals except at very close or very long range. By December 1939, however, it had been recognised that the difficulty did not apply to transmissions made from Germany to agents: they had to be able to receive their control stations’ signals, and if they could hear them, so could the RSS.”

What Hinsley does not explicitly state is that the task of deciphering these messages was undertaken by a Major E. W. B. (Walter) Gill of RSS, in conjunction with his aide, Hugh Trevor-Roper. Gill, who had served as a wireless intelligence officer in World War I, had been recruited by Colonel Worlledge only that same month, December 1939. Exactly why Gill had joined at this critical moment is unclear from the familiar accounts: John Bryden, in Fighting to Lose, describes Gill as primarily ‘a Canadian army signals officer’, and explains that a unit in Ottawa had picked up ‘the clandestine wireless traffic from Canada’, whereupon Gill had arrived at the War Office ‘looking for advice on how to handle it’. Bryden clearly states that the clandestine traffic was the Germany enemy-agent transmissions, and that Gill’s mission was to ensure that RSS abandoned its beacon-searches for the newer phenomenon. If Gill needed advice, why did the War Office not turn to Simpson, first, rather than planting Gill at MI8c with a directive role? Why could it not give those instructions to Worlledge directly? Who was making these critical decisions?

E. W. B. Gill

Bryden’s explanation does not really make sense. Indeed, it does not appear that Gill was shipped over from Canada. According to a biographical article by Dr. Brian Austin, Gill was aged 56, and employed as Bursar of Merton College when he volunteered for duty on the outbreak of war. Indeed, Gill had plenty of relevant experience for his role as head of the ‘discrimination section’ at RSS. In WW I, he had been instrumental in interpreting the wireless messages of the Zeppelins, and had also set up wireless intercept stations in Egypt. After demobilization, in July 1919, Gill was put in charge of the wireless intercept station at Devizes, where, as Austin notes, the attention of the listening devices including listening to allies as well. With an OBE awarded, Gill then returned to civilian life in the Electrical Laboratory at Oxford, and in 1934 published a short memoir of his life in the military titled War, Wireless and Wangles. Dr. Austin, who has performed intensive research into Gill’s life, reports that he was identified in a scheme of Lord Hankey’s as a potentially useful asset in signals intelligence (sigint), and assigned to RSS to work on discrimination, an aspect of traffic analysis that isolates signals of interest. Given Hankey’s charter at that time, as described earlier, that makes excellent sense.

Trevor-Roper, who described Gill as ‘a genial philistine with very little respect for red tape, hierarchy, convention or tradition’, confirms for us that Gill was Bursar of Merton College when he invited Trevor-Roper to join him at the RSS, an observation that does not sit tidily with that of a sudden visit from Canada, and an order from the War Office. MI5 records that GC & CS turned down RSS’s requests for assuming the task of inspecting the messages, as it was too busy, and thus Gill and Trevor-Roper set about decrypting them themselves. By late January, 1940, Gill and Trevor-Roper had solved the cipher, and thus informed GC & CS of their achievement. That provoked Denniston’s ire. (Gill had performed a similar act in World War I, but the War Office had reacted positively to his breaking of the rules.) Perhaps as a punishment, Gill was then ordered – on loan – to Oxford to set up a radar-training school, but, on returning to duty, was demoted and sent to the Siberia of Catterick. He must surely have upset someone with influence, and Hankey could not save him.

Yet, if RSS dabbled dangerously into GC & Cs’s domain of cryptography, it perhaps departed too rapidly from its own mission of interception and counter-espionage. It overlooked a very pertinent fact. Gill’s report, written in November 1940, states, on the basis that ‘it takes two to make a wireless communication’, that ‘if the agent can hear his replies, so can we, and the watch on the German agent stations is thus of first importance to see if they are working to any station we may not have heard’. The serious flaw in RSS’s logic, which I do not believe anyone has picked up, is that SNOW had been supplied with a transmitter only. Since any undetected agents would likewise probably have no receiver capability, there would not have been any messages sent out to them by their ‘control stations’, and thus absence of evidence of acknowledgment or guidance from Abwehr controllers was no solid indication that there were no other agents in possession of transmitters. Gill’s conclusions about the likelihood of undetected wireless agents in Britain may have been sound, but it was based on the assumption that these agents had receivers. If this was an acknowledged flaw in Gill’s reasoning, he could have been reprimanded, and the decision overturned. But it was not: his recommendations were adopted, and echoed by the official histories.

Thus Gill, with his disdain for the proper procedure, was ultimately responsible for a major strategic decision while gaining enemies on all fronts. At exactly the same time that Lt-Colonel Simpson was bolstering RSS and pressing for tight domestic surveillance, Gill turned its attention elsewhere. He incurred the annoyance of Denniston in GC & CS for stepping on its turf, and, with his boss, Worlledge, later touting his achievements in a case involving espionage in Morocco, he also trod on the sensitive toes of Major Cowgill in SIS. While the known technical difficulty of picking up medium-range signals could still have inhibited the detection of active agents infiltrated by the Germans, Gill persuaded his superiors that interception efforts should be focussed overseas. This new policy was articulated in the following account of the decision (at MI5’s 1943 training session of intelligence officers): “As far as stray agents in the U.K. were concerned it was held that rather than try to get on to their ground waves, they would watch the controls in Europe and would get the reflection of the existence of an enemy agent in the U.K.” Yet Dick White’s report includes a very misleading and surprising statement, relating to Gill’s discoveries of early 1940: “He [Gill] therefore obtained from M.I.5 (Captain T. A. Robertson) full information concerning double-cross W/T agents run by M.I.5, and directed the machinery of R.S.S. to a systematic study of first the control, then the other out-stations, of the enemy W/T system thus penetrated.” White is unambiguously referring to the time when the detected traffic was sent to GC& CS, and rejected, early in 1940. There was, however, no network of double-cross agents being run at that time. SNOW was the only candidate. What was White’s intention here in misrepresenting the facts, so soon after the event? Might have he wanted to inflate the breadth and depth of RSS’s capabilities, and to underline the correctness of its new mission?

Nevertheless, out of convenience, and because of the difficulties in picking up short-wave radio signals from close proximity, a policy was adopted of abandonment of any attempt to detect illicit wireless at source, replaced by a reliance purely on reflected signals. Liddell hints at a tortured fear several times in his Diaries without every describing the explicit reasons for his sense of horror – namely, that he knew agents might have transmitters only, and that not all dangerous illicit transmissions were actually issuing from enemy (i.e. German) agents. Moreover, this concern echoed further, and was even represented by one of the historians (Curry) as a disaster of almost existential proportions.

Gill’s demise is astonishing. Here was an officer with an outstanding WWI record in wireless interception, awarded an OBE, bearing an impressive résumé of original scientific analysis in the inter-war years, sponsored by an influential minister, Lord Hankey, and recognised for some important analysis of German radio traffic. He was then dumped unceremoniously, not even being informed of his sacking, demoted from Major to Captain, and despatched to the Royal Signals Training Centre at Catterick. The obituaries written about him all point out his puckish humour, and his impatience with any cant or humbuggery. He must surely have spoken up in inappropriate terms about Denniston, or made other unpublished criticisms, to incur such treatment, but Denniston himself was under the gun, disliked by the Armed Forces staff, and shortly to be demoted himself. It is a mystery that suggests there was more going on than has been recorded. Was Gill really such an unpopular performer in the eyes of the Top Brass?

Such tensions between cryptography and interception had been highlighted by ongoing disagreements between GC & CS and the intelligence units of the Armed Forces, who were all investing more money and personnel into sigint, but who were resenting the amount of control that GC & CS wielded over the committees that made decisions about interception. The Y Committee, which was responsible for wireless interception policy, had held a meeting on December 28, 1939 (chaired by Denniston), that did not succeed in reconciling the disparate views expressed, representable mainly as the conflict between Service independence and inter-Service centralised control. In familiar tradition, the Minister Without Portfolio, Lord Hankey was asked to arbitrate. Hankey was a committee man, and his recommendation of strengthening the Y Committee, under a new chairman from the Admiralty, and joint secretaries nominated by the War Office and the Air Ministry, was adopted on March 1, 1940. In May, this new committee officially recognised RSS’s vital role in exploring these overseas groups before handing them over for attention by the Service analysis stations.

Double Agents

Meanwhile, MI5 had been exposed to its first experiences with double agents. (The primary reference for the double-cross operation is John Masterman’s The Double-Cross System, but, while giving a first-class breakdown of the mechanisms and principles of the operation, it is as much a work of public relations as it is formal history. Ben Macintyre’s Double Cross is engagingly written, and an excellent guide, but contains many mistakes.) This period was dominated by the case of agent SNOW, a Welshman named Arthur Owens. Owens, who was a businessman specializing in batteries, had been an occasional agent for SIS, but was discovered by MI5 to have been in contact with the Abwehr on business visits to Germany. He had been given a wireless transmitter by his Abwehr controllers, and started signalling in early September 1939. He was by then, however, under MI5 supervision, and his messages were initially sent from Wandsworth Prison. (A lively account of Owens’s career as a double, and possible triple-agent, can be found in James Hayward’s Double Agent Snow.) What is important for the story of detection and deception is what MI5 learned early in the cycle, before the mass of would-be spies arrived in the autumn of 1940, with the result that the Security Service was prepared when the tide arrived. It was at this stage that many of the formative ideas about deception, and what was required to make it successful, were forged.

Agent SNOW (Arthur Owens)

SNOW’s exchanges with the Abwehr also provoked some highly important breakthroughs. This particular aspect of how the SNOW experience assisted cryptology generally has been told concisely and comprehensively several times (for example in Nigel West’s MI5), so I shall simply summarise it here, and add some commentary. The knowledge of the codes that SNOW used in his communications facilitated for Gill and Trevor-Roper, and then Oliver Strachey and Dillwyn Knox in GC&CS, the task of deciphering Abwehr messages. Some of these were based on use of the Enigma machine, but communications with agents in the field, and outlying bases that would not have been secure enough to be entrusted with Enigma machines, used hand cyphers (such as pinwheels with codes).

Early in 1940, RSS’s team of Voluntary Interceptors had been able to ‘pinpoint’ [a term that Nigel West provocatively uses] a vessel, the Theseus, lying in the North Sea as the originator of the transmissions received by SNOW, and the source of messages to other agents in Western Europe. It is, however, extremely unlikely that location finding was accurate enough at that time to give precise co-ordinates of any transmitter without local sniffers being required. It is not clear from the accounts whether a broad area was identified, and the precise location of the German vessel established by aircraft inspection, or whether a purely electronic identification of the location of the Theseus had been made. ‘Pinpointing’ is a regrettable term. Indeed, Frank Birch offers the following laconic observation about the state-of-the-art at this stage of the war: “The optimism of enthusiasts as to the pinpoint [sic] accuracy of D/F fixes was shattered early in 1940 by the Norwegian campaign.” Nevertheless, through this successful detection exercise, RSS was able to supply GC&CS with a constant stream of traffic to the cryptanalysts in Bletchley Park.

Yet the questioning of SNOW in early 1939, when he had informed his contacts in MI5 of the immediate plans of the Abwehr to deliver to him a wireless-set, are also very revealing, in that they show both the mixed ambitions of the Abwehr as well as the ignorance of MI5 about wireless matters. The set itself was delivered to a left-luggage locker at Victoria Station, and MI5 arranged for the equipment to be removed and inspected by SIS before allowing SNOW to explain its workings, and hand over its codes and callsigns that he was supposed to use. The device was small, and portable, and was claimed to have a range of 12,000 miles, using an ordinary 350-volt battery, and also to be activatable by plugging into a normal lamp-socket. Yet it was a transmitter only: SNOW was to inform his masters when transmissions would start by means of the regular mail service, and, in time, acquire a short-wave set that would allow reception. This is quite an extraordinary revelation, showing how unambitious the Abwehr was in its wireless plans at this time. A transmission without any mechanism for immediate confirmation was a highly quixotic venture, and the Abwehr’s relying on its agent to construct a receiver (a more complicated piece of apparatus than a transmitter) and manipulate it properly betrays an overall lack of seriousness that again belies Howard’s confident assertions about Abwehr strategy.

An earlier interrogation of SNOW had been carried out, in September 1938, by Edward Hinchley-Cooke, an enigmatic figure in the whole saga. Hinchley-Cooke is a puzzle, primarily because the authorized historian of MI5, Christopher Andrew, gives him no coverage at all after the early 1920s. He features regularly, up until 1943, as an interrogator of Germans in Liddell’s Diaries, but Nigel West (who also edited the published version of the Diaries) never places him in any of his organisation charts in his own history. Hinchley-Cooke had a German mother, and spoke German very fluently, which is probably the reason that he was brought into so many of the interrogations and prosecutions of Nazi agents. John Curry, in his history of MI5, suggests that Hinchley-Cooke was ‘attached to’ B Division in 1939, while working for the War Office, because of his interrogatory skills, but then clearly states that he was on the Director-General’s Staff after Petrie’s reorganization of summer 1941. John Bryden indicates that Hinchley-Cooke was the sole MI5 officer working on German counter-espionage up to the outbreak of the war. Moreover, Hinchley-Cooke’s questioning of SNOW was not very subtle. He failed to follow up on SNOW’s evasive answers, and it is clear that Hinchley-Cooke had no understanding of the principles of radio communication and codes. He was accompanied by an Inspector and Superintendent from Special Branch, but their names are redacted, and they contributed little to the proceedings. This lack of technical expertise would come to dog MI5 in a big way.

The Strange Career of Lt.-Colonel Simpson

Yet MI5 did possess competency – for a while. Even more astonishing than the oversight with Hinchley-Cooke is the failure of the authorised historian to include any reference to a key figure behind the events of 1939, one Lt.-Colonel Adrian Simpson. Perhaps Andrew’s omission (quite probably a matter of strong guidance to the authorised historian by MI5’s mandarins) is due to the fact that Simpson appears to have been appallingly mishandled. We owe it to Curry’s ‘official’ history, published for internal use in 1946, to describe for us how Simpson was appointed to advise MI5 on all matters relating to wireless after the Security Service had declined to take on the responsibility for establishing the Radio Security Service in late 1938. Simpson was well qualified, having been head of MI1(b), the code- and cipher-breaking agency in WWI, and an executive with the Marconi company between the wars. Nigel West’s Dictionary of Signals Intelligence informs us that in 1915 ‘Simpson established a General Headquarters cipher bureau at Le Touquet to analyse material collected from intercepted enemy landline communications’, and that ‘within a year, MI1(b) had built direction-finding stations at Leiston in Suffolk and Devizes in Wiltshire, with a control facility on the roof of the War Office in London’. MI1(b) was a core group that was amalgamated into the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) in 1919. So Simpson was eminently qualified to define the next generation of interception facilities. And it should be noted that Walter Gill had been the head of the Devizes station, possibly appointed by Simpson: one might expect him and Simpson to have been collaborators, even friends.

Simpson’s efforts appear, however, to have been wasted. Curry would go on to write: “One of the conspicuous illustrations of these tendencies has been the refusal in December 1938 to grapple with the problem of wireless and the consequent establishment of R.S.S. under M.I.8 with results recalling the principles of Greek tragedy.” This extraordinary uncensored commentary on ‘Greek tragedy’ must hint at disasters undocumented. If the war was won, and the Double Cross operation judged to be an utter success, where did the calamities lie? Which character would suffer in Act V? Would it be Liddell’s failure to be appointed Director-General of MI5 in 1953? Where were the bodies buried? Why did MI5 allow this judgment from Curry to appear?

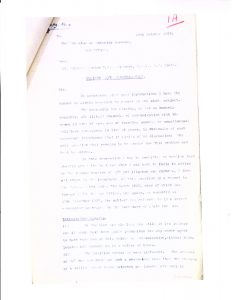

Curry states that B.3 (which Simpson headed, a section under chief of counter-espionage Guy Liddell) was not set up until the beginning of the war, but Simpson was clearly active in some influential capacity throughout 1939. He wrote (at least) three important papers, none of which appear to have survived. In an October 1938 report that surely provoked the December decision, he had crisply laid out the investments, equipment, and organisation that an effective Security Service would require to defend the realm against illicit wireless, pointing out that technology had advanced considerably in the past few years. This scenario would include three fixed Direction-Finding stations, and a corps of several dozen Voluntary Interceptors to track the airwaves. Hinsley and Simkins reinforce the importance of Simpson’s recommendations, writing that his report ‘reached the disturbing conclusion that interception arrangements were so inadequate that had recent developments led to the outbreak of hostilities a skilled agent could have established a reliable wireless service and maintained it for a considerable period with almost complete immunity; he added that such a service might well be already in existence.’

Simpson took over responsibility for B.3, a section that was set up to liaise with the RSS, and to deal with suspected illicit transmissions, in person being involved with any search and prosecution decisions. He was clearly closely involved with the SNOW case during 1939, but was moved to write another report, dated February 2, 1940, which harshly criticized ‘the state of affairs concerning the detection of illicit wireless’, although he laid most of the blame at the General Post Office for its failure to provide the appropriate skilled staff in operating the sniffer-vans that would hunt down transmitters to individual residences. His career with MI5 effectively ended at that point, as he was reportedly moved over to General Wavell’s army in the Middle East: whether he was pushed out, or resigned in frustration, is not clear. The source of this story may be Stephen Dorrill, who writes in his 2000 history of MI6 (SIS) that Simpson was appointed by Wavell to prepare to counter possible Soviet intervention in Transcaucasia. Since Dorrill then states, however, that Simpson, ‘a former managing director of Marconi’ [correct], ‘had been ADC to the Grand Duke Nicholas in the Russian Army’s Caucasus “Savage Division”’, Dorrill may have got the wrong Simpson. That experience does not sound as if it comes from the ‘Memoirs of a Wireless Interception Man’. In any case, Curry’s observation that MI5 ‘lost his services’ at that time suggests that he resigned. An intriguing correspondence that Mark Rowe, author of Don’t Panic: Britain Prepares for Invasion, 1940, discovered in Bristol record offices, indicates that, in April 1940, Simpson was still recruiting Voluntary Interceptors to the RSS organisation. Maybe he did not move to the Middle East, but worked for a while championing what he saw as RSS’s true role, and applying pressure to his successor, Malcom Frost (see below).

Curry’s suggestion that Simpson stated that the fault lay with the staff operating the sniffer-vans may have been a political comment that veiled the truth. If sniffer-vans were going to be effective in following up triangulations of illicit transmissions, they would have to work in real-time in close communication with the Y Service that tracked signals. Sending them out the next day to try to detect noise would be a fruitless task unless the service expected the offenders to transmit at the same time that day. Moreover, the sight of such vans would immediately have deterred further transmissions, as we learned from the activities of the communist Green network (see SoniasRadioPart9). The Gestapo would soon perfect such an operation, with radio contact between vans and central control (which I shall describe in a later chapter), but one can easily imagine a more casual approach in island Britain at this time. Simpson’s criticisms, and imminent departure, hint at such more serious problems. Perhaps he had identified the inevitable conflict between efficient location-finding and controlled double agents using wireless, and his name has thus to be excised from the record, like one of Stalin’s commissars disappearing from a photograph?

What is even more astonishing is Guy Liddell’s almost complete exclusion of any reference to Simpson in his Diaries. The complete (but redacted) version of the diaries at the National Archives contains just one reference to Simpson by name (when he is called to investigate Verey lights at Harwich Harbour), and one veiled reference to his positional identity (B.3) when, on March 20, 1940, shortly before he resigned, Simpson attended a meeting with Liddell, Worlledge of M.I.I.8, and G.C.& C.S. officers and ‘cypher experts’, to discuss decrypted messages from Germany. Yet the organisation of B3 is very puzzling. If Simpson headed it (as Curry clearly states), T. A. (‘Tar’) Robertson must have been his subordinate, yet Robertson signs off his reports as ‘B3’ in the autumn of 1939, while a couple of anonymous memoranda, signed off as ‘B3.a’ while Robertson was away, may have been written by Simpson. Robertson worked closely with Simpson on the SNOW case: Robertson refers to Simpson’s attending a meeting at Robertson’s house without clarifying the management relationship.

Yet there may have been problems with authority and rank. Simpson was a Lt.-Colonel with a proper military background, while Robertson was only a Captain at this time (soon promoted to Major after Simpson left). In the rank-obsessed climate of wartime Britain, that would have been a problem if Simpson had truly been subordinate to Robertson. Curry muddies the waters even more, since elsewhere he writes that a subsection B.3.B was responsible for liaison with RSS. That is how the structure appears in his diagram of the organisation after the Petrie decisions in July 1941: I have found no specific reference to B.3.B in the time that Simpson was around. Maybe with some purposeful vagueness, without giving a precise date, Curry writes: “It [B.3.B] derived from the section under Captain later Lt.-Colonel Robertson and Lt. Colonel Simpson which, before and soon after the beginning of the war, was concerned with the arrangements for developing the R.S.S. organisation and for maintaining liaison with it . . .” If anything, it points to an awkward compromise joint leadership, akin to the role that Liddell was sharing with Lord Swinton’s pal Crocker at the time. William Crocker, a solicitor, was another disastrous imposition forced upon MI5, this time by Sir Joseph Ball, who was responsible for handling the Fifth Column ‘menace’ on Swinton’s Security Executive.

Liddell frequently talked to Robertson about the SNOW affair, but ignored – or bypassed – the expert brought in to design the RSS architecture, and makes no mention of his career, or the reasons for his leaving, even though what occupied Simpson’s time (the laxity over tracking down illicit wireless) was a subject that worried Liddell just as much. Robertson himself is recorded as speaking to Liddell in a fashion that passed on Simpson’s opinions (such as the criticism of the sniffer vans), and it appears that Robertson was content working under/with Simpson (unlike his relationship with Simpson’s eventual successor, Malcolm Frost). Thus Liddell’s studied rejection of Simpson’s significance is even more surprising. Did he perhaps resent an officer being foisted upon him? Did Simpson argue and activate too strongly for taking on RSS within the B3 section? It all points to a mysterious clash of personalities, or a disagreement over policy, not just a later embarrassment that might have required his name to be redacted. One must also wonder whether Gill and Simpson had crossed swords at some time. Gill, as I pointed out earlier, had been head of the interception station at Devizes, which was one of the monitoring posts established by Simpson. The highly oppositional strategies of a) RSS being consumed by foreign broadcasts, and being passed to SIS (Gill), and b) MI5 securing its control over illicit transmissions in Britain by taking over RSS (Simpson), would have clashed mightily. Is it possible that Gill was inserted into RSS to ensure that the unit did not fall into the hands of MI5? Moreover, the neglect by the authorised historian, Christopher Andrew, to write anything about B3 section must count as either a colossal oversight or an act of censorship – especially since Andrew recognised Simpson’s intellectual contribution in his earlier (1999) Introduction to the publication of Curry’s History.

SNOW’s Radio Activity

To return to SNOW. The coverage of SNOW’s radio activity after MI5 took control is infuriatingly elusive in the books that write about him, from Nigel West’s rather choppy MI5 (1981), through Volume 4 of The Official History of British Intelligence in the Second World War, by Hinsley and Simkins (1990) and Christopher Andrew’s authorized history of MI5 Defend the Realm (2009), to James Hayward’s breezy Double Agent Snow (2013) and John Bryden’s Fighting to Lose (2014). The archives on SNOW are typically disorganised, with much repetition, as well as many undated and anonymous reports, and it is consequently very difficult to identify exactly what wireless equipment is being referred to in the various documents.

The narrative on his wireless activity appears to run as follows: As outlined earlier, the Abwehr originally, in January 1939, provided SNOW with a transmitter only, suggesting that he himself construct a receiver. SNOW had been apprenticed as an electrical engineer, and was an expert on batteries, but constructing a reliable transmitter was no simple task. In the interim, it would mean that confirmation of receipt, transmission times, etc. would have to be conducted by letter, through SNOW’s purported business contacts in Germany – an extraordinary convoluted process, but one which was acceptable during peace-time. The Abwehr apparently had plans to send SNOW to the Americas at one stage: hence the extraordinary wide radius the transmitter enjoyed. The set was flexible and portable. It could be tuned to different wavelengths, unlike later models used, which required individual crystals. But it was unreliable, burning up under SIS/MI1(g) tests, and the boffins had to restore a resistance unit so that it would do the same again when SNOW tried to use it. In fact, SNOW was still having problems with it in July 1939, when he wrote to his contact Auerbach saying that he had at last rectified the faulty resistance. And transmitting successfully over 12,000 miles, had SNOW been able to smuggle his set overseas, would have required a very large antenna.

SNOW’s career was then disrupted by family matters: a jealous wife reported him to the authorities, telling them that he had disposed of his wireless set. MI5 tracked SNOW down to Surbiton, whither he had moved with his mistress on August 29, and, with his guidance, Robertson and his colleagues discovered a receiver in the bathroom cupboard, and his original transmitter buried in the garden. (Hayward notes that the receiver was a ‘crude’ device, and that SNOW had ‘apparently’ constructed it himself: maybe the experts from the Royal Signals had actually delivered it for him.) When war broke out, SNOW was arrested, and MI5 started broadcasting on his behalf, officially using him as a double agent. After the initial broadcast from Wandsworth Prison, the officers feared that the Germans might be able to triangulate the origin of the signals, and then ask themselves how a clandestine transmitter could be allowed to operate from such an institution. In fact they were being unduly cautious: locations could be identified only to the level of a large conurbation, and (certainly at this stage of the war) it would have taken a platoon of sniffer-vans, supported perhaps by portable equipment, to narrow the search to a particular building. Moreover, German goniometric techniques were inhibited by geography: it took at least three receiving stations to plot an accurate fix, and their dominant Eastern orientation meant it was more difficult for them to triangulate transmissions from the UK. The British authorities would nevertheless have been mindful of the successful, but highly complex, process that allowed them to home in on the illicit Soviet MASK transmitter in Wimbledon a few years before.

Hereafter the story becomes contradictory. SNOW did make contact with his Abwehr controllers on September 19, but, given the problems he was experiencing with his apparatus, Hamburg promised to send him a new transmitter. MI5 reported how unreliable the current transmitter was. On February 29, Liddell noted that SNOW’s set had blown up, and a telegram had had to be concocted to send to the Abwehr to indicate that he had not been raided. His apparatus required a 98 foot antenna, which did not work reliably if misaligned. (The device had a knob – a ‘tuner’ – to control frequencies, but required corresponding changes to the antenna length if a frequency was switched. Using a knob would have been less reliable as a way of selecting a frequency than the insertion of a fixed frequency crystal.) Signals were not strong: Hamburg said they were weaker than those coming from Ireland. MI1(c) had been monitoring SNOW’s transmission: they said that jamming by a powerful station was causing interference. A note of February 29, 1940 indicates that the intrusion of dampness caused the equipment to burn up, with advice to use an outside antenna to avoid the use of the relay circuit.

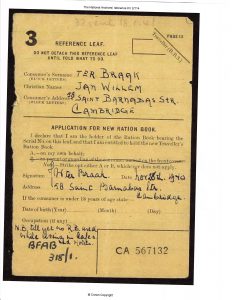

A typical British suitcase wireless transmitter/receiver of early WWII

Yet, in another Case History, undated, but probably written in April 1940, as it refers to events that month as in the recent past, and describes how ‘every two or three months’ SNOW travels to Antwerp to meet Dr. Rantzau (whose real name was Ritter) – a record which must have preceded the Nazi invasion of the Low Countries. Here the writer tells us that SNOW ‘broadcasts every evening’. At some stage, SNOW’s set must have been improved after the stumblings earlier in the year: the archive notes that seamen couriers (quaintly described as ‘lascars’) did bring over new parts in April 1940, but the arrangement of having a separate receiver and transmitter was clumsy, and maybe the range of the machine made it more liable to direction-finding. Back in March 1939, MI5’s B.3 (i.e. Lt.-Colonel Simpson) had sought the opinion of Colonel Yule of MI1(g) as to how long he thought it should take for ‘our internal intercept and D/F organisation’ to locate SNOW’s transmitter, clearly concerned about what the Germans were thinking. Yule had organized some rather casual efforts to track SNOW’s frequency, and even mentioned detector vans, but the initiative appeared to fizzle.

Despite his studied ignoring of Simpson, Guy Liddell himself showed remarkable foresightedness in understanding the sensitivity of this issue, and the value of downplaying the radio-detection capabilities of the British security organs. In a diary entry for October 28, 1939, he wrote: “Brigadier Martin of MI.1 has suggested that a representative of the News Chronicle who thinks he had detected an illicit wireless station, should be shown the apparatus we use and taken round in a van in order to get a cross-bearing. He would then write up the story in the Press. D.S.S. telephoned Martin to say that we had strong objections to any publicity being given to this matter. It was in our interests that the Germans should regard us as grossly inefficient in these matters, particularly as ‘Snow’ is sending them weather reports. If they thought our organisation was that good they might well ask how it was that he managed to get his messages through.” This episode shows how quickly Liddell summed up the value of subterfuge against the obvious appeal of propaganda, at a time when the British press was very keen on providing the public with ammunition against the Fifth Column threat.

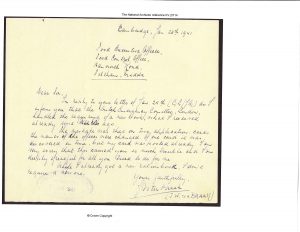

Nikolaus Ritter, Chief of Abwehr Air Intelligence

Direction-Finding

The British were not the only group to be thinking about wireless detection. When SNOW visited Rantzau in Antwerp in early April, 1940, prepared by MI5 to probe the enemy’s thoughts on detection-finding, Rantzau told him that he should not be concerned about being detected, as ‘as it was a very difficult thing to track down short wave wireless sets’. This information – that shortwave sets were immune to detection and direction-finding – was one he had originally given to SNOW as early as January 1939, a revelation that SNOW had passed on to a sceptical Robertson. Now, in April, 1940, Rantzau even mentioned the Abwehr’s strenuous efforts to track down such sets closer to hand. The details are redacted, but these were probably sets managed by the Soviet Red Orchestra. Rantzau told SNOW that a transmitter had been detected in the Wilhelmshaven area, but it had been impossible to run it down. In the light of later experience with this communist network, and with SOE wireless operators inserted into Nazi-controlled territory, primarily in France, this rather sanguine opinion would need to be changed.

“This is nonsense”, declares Bryden, perhaps too brusquely, implying that Rantzau was being devious, and in his book he gives an oversimplified account of how triangulation worked. In the early part of 1940, techniques were surely not that advanced. I quote Bryden’s summary in full: “Obviously, in order to survive in enemy territory, it is helpful for a spy to change frequencies and call signs as often as practical., but the most important necessity is to send from different locations. DR. RANTZAU was not asked the most critical question: Was it safe for JOHNNY – the name Ritter preferred to use for Owens – to always be sending from the same place? The Germans were soon to provide the answer when Britain’s sabotage agency, Special Operations Executive, began landing its agents into occupied Europe. Their wireless transmissions were DF’d and they were caught by the score. The only MI5 officer with the technical clout to challenge DR. RANTZAU’s advice – Colonel Simpson – had left. In his absence, Robertson chose to believe his German opponent.”

What is extraordinary is that, the very same month (April 1940), SNOW’s transmissions had been picked up by the French ‘illicit wireless service’, as Liddell reported. The French were, of course, conveniently at a distance where clear signals could be picked up. Fortunately, the French had sent a report to GC&CS, whence Commander Denniston forwarded it to Gill in RSS, who contacted MI5. “We are telling them to lay off”, wrote Liddell. Robertson sent a letter to Major Cowgill of SIS, telling them that MI5 knew all about the station. But, if a French service had been able to pick up SNOW’s signals, and to determine that it was probably an illicit set operating from the United Kingdom, why did MI5 not imagine that the Germans would conclude that the British should have been able to do the same, making allowances for the dispersion of their interception stations? (This is a vital point that Bryden makes, although he does not discuss the subject of ‘dead’ zones.) And was it not a careless mistake to brush off the interest of the French so casually? It could have been a leaky organisation, and the rumour that the British were manipulating a German agent could have spread.

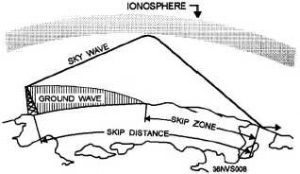

Despite the provocative but fortuitous French experience, the problems in performing accurate direction-finding of short-wave radio signals were officially well recognized at the time. Frank Birch, in his Official History of British Sigint, 1914-1945, wrote: “Intertwined with the problem of interception was that of D/F, greatly complicated since 1918 by the development of shortwave transmissions and the general awareness among signals personnel of the need to defeat, as far as possible, D/F operation”, rather cryptically hinting at defensive methods that British signals would need to employ against German capabilities. Surprisingly, Birch did not explain why short-wave transmissions were less easy to detect: it was because their signals were bounced off the ionosphere, which gave them a greater range, but made their isolation more difficult. M.R.D. Foot, in his book on SOE, informs us that this phenomenon is called ‘skip’: the signals bounce between the ionosphere and earth, and create ‘zones of silence and zones of good reception that may alternate all around the globe – and may vary according to time of day, season of the year, or prevalence of sunspots.’ (As will be shown below, Simpson offered a similar explanation of this phenomenon.) These signals were also subject to interference from local electronic activity, but, if that were too intense, it would have affected reception on behalf of the intended audience as well. Birch also pointed out that, while the Germans were able to specify their frequencies to the level of one kilocycle, the British were precise only to five, and ‘and in practice measurements were often up to a hundred kilocycles out’. Birch went on to write: “Now, its frequency was an attribute of a signal on which both traffic analysts and cryptanalysts partly based their work, and by February 1940 the nuisance of inaccuracy had become generally recognised as acute. But the remedy was still far to seek.”

Earlier in this piece, I quoted the MI5 report about giving up on trying to ‘get on to their ground waves’. The way that short-wave transmissions worked, ground waves would be emitted from the antenna, as a source of radiation, and could be picked up until the curvature of the earth (or unusual geological formations) attenuated them completely. In order to reach a remote target, the antenna would also emit skywaves, which would use the ionosphere to ‘bounce’ those signals beyond the horizon. But there would be a dead zone between the area where the ground wave penetrated and the larger expanse where the signals could be picked up – both by the desired station, as well as by interception stations with roughly the same distance and sphere of receptivity. (see diagram) These areas are technically called ‘lobes’, and their dimensions are dependent upon whether the antenna is placed horizontally or vertically. And that is why the detection and location of illicit radio were problematical. Interception stations within the skip zone would receive nothing if they were also beyond the ground wave range. And it would require at least two stations in the right place to attempt a fix, while the distortions of the skip zone could confuse the analysts.

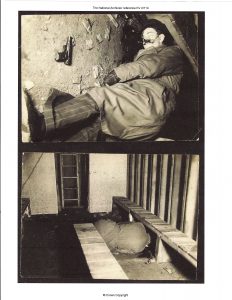

Ground waves, sky waves and the ‘Skip Zone’

Birch was even more outspoken elsewhere, and it is worthwhile quoting in full an important paragraph: “On its own, D/F has been described [here he cites a Naval source] as ‘by far the most important source of communications intelligence, if the cryptographers are out of form.’ This is no doubt true, but truer still is another authoritative statement that ‘independently of Special Intelligence, D/F was useful, but in a much narrower field’. Optimistic illusions as to its accuracy were shattered early in the war. ‘It was the exception rather that the rule for a fix to be obtained that could be classified as being within ‘forty-mile radius’, and there were many occasions on which even such fixes turned out to be very wrong indeed’. In spite of the multiplication of stations carefully sited so that as many as 30 or more bearings could be taken of a simple transmission, in spite of improved equipment by technical staffs and the working out of a mathematical method of calculating the position of a unit, based on the ‘weight’ or class of bearings, investigations by experts revealed that ‘a good operator was nine-tenths of the battle.’ In plotting, skill and experience mattered more than gadgets and quantity of bearings. In short, D/F ‘as practised from 1939 to 1945 was an art – not a science.’” That judgment would appear to contradict directly the rather overawed conclusion that the American intelligence officer Norman Holmes Pearson offered in his Foreword to John Masterman’s book: “The techniques of intercepting messages sent by wireless were highly developed. So was the science of direction-finding by which the location of the transmitting instrument could be determined.” That is how mythologies begin.

Simpson had himself contributed to the debate. Again, we have to rely on Curry. Before he left B.3, Simpson wrote the third report that we know of: ‘Notes on the Detection of Illicit Wireless 1940’, with a view to investigating reports of suspected illicit wireless transmission. In Curry’s somewhat clumsy words: “He explained the problems connected with Ionosphere or Reflected Ray communication and ground rays, and suggested that secret agents would be able to avoid bulky or intricate apparatus and that only low-power would be employed. He said that, assuming an efficient receiving station in Germany, it would be possible to select a suitable wave-length, having regard to range and seasonal conditions, which would give a regular, reliable service. If such a station were to be established in a carefully chosen locality in this country it would very likely not be heard at all by our permanent interception and D/F stations. Such a station could be situated in the centre of a densely populated area or alternatively installed in a small car. He set out detailed instructions for procedure in dealing with investigations in these circumstances.” What those instructions were, we shall apparently never know. But his advice appears to have been ignored – or to have been politically unsuitable.

Simpson’s message was picked up by Hinsley and Simkins in Volume 4 of their History. “Since Snow’s signals had not been heard before MI5 took control of him, the failure to intercept others was understandably attributed to the inefficiency of the watch or to technical problems, notably the difficulty of picking up low-powered high frequency signals except at very close or very long range”, they wrote, to which Bryden has a riposte. In a note concerning the official claim, he comments: “This is correct, but it does not mean that the transmitters could not be located. The British Post Office was already using mobile direction-finding units to pick up local transmissions, and the Germans in Holland and France were to develop the technique to a fine art.” He goes on to say ‘the spy could change frequencies by changing the crystals in his set.’ For 1940, Bryden probably anticipates a little too much, and credits the Post Office vans with a little too much finesse. (It is one thing to roam around potentially busy locations, like Embassy districts, and another to chance upon illicit transmissions from private residencies around the countryside.) We now know that Simpson criticized the skills of the mobile direction-finding units (as did Liddell), but they may have been limited by technology. Furthermore, changing crystals had other implications, and was not available to every operator at this time. The commentaries on SNOW’s apparatus inform us that, in order to change a frequency, if a crystal were inserted (or the change made by the advanced facility of using a knob), the length of the antenna had to be changed as well. Matters were not as cut and dried as Bryden represents them: the state-of-the-art was probably more in the vein of what Rantzau and Simpson independently stated at about the same time.

The confusion is reinforced by other conversations. Liddell had discussed the question of detection with Menzies, the head of SIS, in April 1940. By then, Menzies claimed that it had wireless sets ‘operating from German territory and all over the continent’, a boast that would incidentally appear to be belied by Keith Jeffery’s authorised history. Thus Menzies’s statement was probably more goal than reality. Menzies echoed the general confidence when he told Liddell that he thought that SIS’s newest sets were ‘extremely difficult to pick up’, and he doubted very much ‘whether any monitoring system however widespread will be effective against them’. Where Menzies derived this science is not explained (he had no doubt been briefed by his head of Section VII, the telecommunications expert Richard Gambier-Parry, who was known for treating non-technicians with some arrogance) but it led Liddell to compare SNOW’s set, even with its new valves, very unfavourably against the SIS’s latest technology. Liddell concluded that diary’s entry with a not unreservedly confident belief that the British were ahead of the Germans in this matter. Both Rantzau and Menzies would later have to revise their opinions.

[This whole puzzle of direction-finding is tantalisingly highlighted by the titles of a set of lectures given by Herbert Hart, Major Morton Evans and Major Frost at the MI5 training session for regional officers on January 5th, 1943. They were, respectively, ‘Intercept Intelligence and its uses’, ‘The work of R.S.S. Interception and discrimination of Axis secret communications and its bearing in detection of illicit W/T’, and ‘Investigation into illicit W/T’. Unlike Dick White’s comprehensive notes, the details appear to have been destroyed.]

In any case, SNOW was provided with a new transmitter/receiver in August 1940, when the courier BISCUIT (Sam McCarthy) went to Lisbon, and was handed over a suit-case containing a new apparatus, known as an Afu. This is the equipment described in a later 1941 report: “His [SNOW’s] second set was a mains operated transmitter and receiver of excellent construction, the reception frequency being 5,800 kcs and the transmission frequency either on 6636 kc or on 6536 kc. The even frequency was used on odd days, the odd frequency on even days. The antenna used consisted of about 90 ft. in one leg and counter-poise 15 ft. long in the other. There was no difficulty in erecting this or its subsequent many locations and no difficulty experienced anywhere.” Hardly the discreet apparatus that could be easily concealed from the landlady, but it presumably gave much more reliable service until SNOW was closed down in 1941, and his wireless taken over for other agents. But there was a cost, too, since only two frequencies were offered, appearing to be delivered by separate crystals rather than a controlling knob: more reliable, but with fewer options.

Thus the Abwehr’s initial experiments with wireless were very tentative. It was as if they did not take the need for close two-way communication very seriously. They did not supply SNOW with reliable equipment, and accepted long periods of silence with equanimity. This was, of course, when western borders of Europe were still open for travel. The Afu set was ideal for smuggling overseas, concealed in a suitcase, but was probably not robust enough to survive a parachute jump. The pattern of the next wave of agents to arrive would reinforce this phenomenon, however. Spies were not planned to be long-term subversives: their terms of activity were expected to be short as they facilitated conquest. Hitler was expecting a successful invasion of the British Isles after he moved through Western Europe, and won the air-battle. Investing in a miniaturised, robust and flexible combined transmitter/receiver was not a priority. This lack of imagination about the potential of agents equipped with wireless would require the British to take the lead, and help put ideas in the minds of their adversaries.

The XX Committee

Meanwhile, MI5 was increasing its attention on the strategic challenges of handling double agents. The original idea had in fact come from the French, In June 1938, the intelligence office Paillole had visited MI5 to instruct them on such a policy and practice, and in October 1939 Dick White, Liddell’s right-hand man, had gone to France to get a refresher. On January 10, 1940, Liddell entered the following observation in his Diary: “With a view to supplying double-agents with information, commands have been asked to send in reports on local information or rumour which they, as ordinary members of the public, can pick up from observation or from gossip. Xxxxxx xxxx xxxx [redacted], this information will be supplied for transmission to the enemy. It is hoped that once confidence is established in this way it will be possible to mislead the enemy at a critical time. In addition it is felt that the reports will provide M.I. with some picture of the extent of leakage that is going on.” Yet MI5’s resources in this field were now scant. SNOW, the only agent with a wireless snow under double control, was acting suspiciously. Moreover, his wireless blew up on February 29, and a false telegram had to be concocted to show that he his operation had not been raided. A series of adventures would ensue, but he was finally cut off on April 13, 1941. MI5 officers by then considered that his Abwehr control, Rantzau (= Ritter), had wised up to what was happening.

The Fifth Column hysteria confused practically everybody about a native threat to abet the coming invasion. Throughout the year, Liddell would report regularly on illicit broadcasts detected, but they would inevitably end up as being harmless, normally foreign embassies trying to break the rules. In July 1940, Malcolm Frost, the BBC man, was appointed to head a new branch (W) to coordinate SIS and MI5 activities concerned with Radio Security, supported on a committee by representatives from the RAF, the Army, and the Royal Navy. It looked like an auspicious move, although at about the same time, Churchill rather unhelpfully told the British public that the Fifth Column menace ‘had always been exaggerated’, perhaps forgetting that he himself had been the prime cause of that hyperbolic reaction. On October 1, Liddell rather enigmatically reported that a W Committee had been set up, at the instigation of the Director of Military Intelligence, ‘to control false rumours and disseminate false information’.

Tensions arose almost immediately. It did not make sense for a man recently recruited from the BBC for his radio expertise, with no experience in counter-espionage fieldcraft, to be put in charge of the new group responsible for locating enemy agents. In the summer of 1940, Liddell had reported that he was impressed with Frost (‘strikes me as an extremely able and knowledgeable person’). In July, Liddell and Frost discussed the new group that Frost would lead ‘under the guidance of RSS [MI.8]’, with Robertson as his deputy. As soon as they heard about this, MI.8 applied fresh pressure on MI5 that the Security Service should absorb RSS completely (including all the civilian Voluntary Interceptors). MI5 was generally still very wary over taking responsibility for activities deriving from foreign soil. Soon, moreover, Frost was bridling over the demands from MI.8 for him to hire dozens of military people to carry out the RSS’s mission – a demand that had been ironically crafted by Lt.-Colonel Simpson. Frost declared that he wanted to hire his own people. Frost was appointed head of W Branch in August, but it was soon subsumed into Liddell’s organisation as a section (B3) – Simpson’s old organisation, where Robertson worked. The W Committee soon morphed into the W Board, and delegated its detailed work to the XX (Double-Cross) Committee, which started to meet in January 1941. This was a dysfunctional mess.

By then, B3 was in tatters. Frost had always wanted his own Branch, reporting at the same level as Liddell, and his ambitiousness, arrogance, and intriguing started to grate. Lord Swinton, the head of the Security Executive (who had encouraged Liddell to charge Frost with setting up the new group on radio security only a few months before), said that the bumptious Frost had to go: Tar Robertson found Frost impossible to work for. Frost had of necessity (as head of B3) been an integral part of the debates over the German agents in the preceding months, but he had no expertise in this area. In December 1940, Liddell reported that Robertson and his group of agent handlers had been moved over to B Branch, as the new B1a section, ‘back where they belonged’. Yet the initial handling of captured agents was in fact carried out by a group named B8L: you will find no mention of that entity in Curry’s, West’s or Andrew’s book. [One should not trust official authorities on the structure of Liddell’s ‘B’ branch: memoranda in the TATE file show Robertson, after being identified as ‘W’ in November 1940, reporting as ‘B2a’ long into 1941, which would have put him under Maxwell Knight’s ‘Agents’ section. Andrew’s implication that B1a had been run by Robertson since early 1940 (p 249) is patently false. McIntyre makes the same blatant mistake (p 38).] It took the early 1941 arrival of David Petrie, as the new MI5 chief, to bring some permanent structure to the service. Yet Curry’s organisation chart for July 1941 still shows the unpopular survivor Frost in charge of B.3 (Communications), including B.3.B (Illicit Wireless Investigations; R.S.S. Liaison). Robertson is only then under Dick White in charge of B.1.a (Special Agents).

In the middle of November, the W Committee had set up objectives for the planned Double-Cross System, and, at exactly the time that Malcolm Frost was falling into greater disfavour, the Oxford don John Masterman (who had been tutor to Dick White) was interviewed to help the project. He became the highly successful chairman of the XX Committee, which had its first meeting on January 2, 1941, and was to convene weekly throughout the war, the last meeting being on May 10, 1945. The W Board (the new name for the W Committee, to which the XX Committee reported) was responsible for setting overall policy, but it left the details of managing double agents to Masterman and the team of B.1a, later led by a happier Tar Robertson.

Sir John Masterman, Chairman of the XX Committee

By then a new tactical thrust from the Germans had taken place. The Battle of Britain had started on July 10, 1940, and, in anticipation of a swift victory, Hitler ordered that spies be inserted into Britain to inform the invasion force of weather conditions, troop movements, the condition of aerodromes, etc. Between the beginning of September and the end of November, about a couple of dozen agents arrived on British shores. MI5 had used SNOW, however, to pass on examples of identification numbers for ration-cards to the Abwehr, so that the British were able to detect forgeries supplied to captured agents during this later swarm. This gave MI5 an inkling of the possibilities of deception, with some important feedback, and constituted one of the most important coups of the campaign, as it verified the trust that the Abwehr held in SNOW. Owing to SNOW’s information, predominantly the supply of false identity card numbers, and the decryption of the Abwehr hand cyphers, the British were ready for the infiltrators. A few arrived by sea, the majority by air. Most were arrested within hours. Several were executed: a couple committed suicide. And some were turned into double agents.

One remarkable aspect of the project was that, while most of the spies were equipped with wireless apparatus, it normally consisted of a transmitter only. That decision had been made primarily out of optimistic pragmatism: the Nazis expected the invasion force to arrive shortly afterwards, and there was no need for the spies to receive additional instructions after they had supplied the information they had been instructed to gather. But it was not an exclusive policy, nor one governed by the logistics of carrying a set by boat, or landing with a heavy unit by parachute. (Agent TATE was told that the type of set they were to use in England depended on whether they crossed by sea or by air, as there was not yet any shock-proof apparatus available. But that was clearly not the whole truth.) The first wave that arrived on the Kent coast on September 3rd all had transmitters only. Gosta Caroli (SUMMER), who was parachuted in three days later, brought a combined transmitter/receiver with him, strapped to his chest – but it knocked him unconscious when he landed. Amazingly, he had never experienced a practice jump. TATE (Wulf Schmidt), underwent a bad landing from low altitude on September 20, owing to poor weather, and he hurt his hand and ankle because of the weight of the equipment strapped on to him. Dr. Ritter (aka Rantzau) had informed TATE that arrangements were being made for him to take with him to England a separate transmitter and receiver and also a large transmitter (called a ‘Z.B.V.’) which would be dropped separately and which he could destroy if the smaller sets were unbroken after landing. How exactly a probably injured airman was supposed to grope around the countryside looking for another parachute with transmitter/receiver, and then conceal them, before looking for a safe haven, without provoking interest from the local population, is not addressed. The spies were expendable.