(Sir Rudolf Peierls was a German-born British scientist whose memorandum, co-authored with Otto Frisch in early 1940, helped convince the British authorities that an atomic bomb was a possibility. He later earned some notoriety by recruiting Klaus Fuchs to what was called the ‘Tube Alloys’ project. Fuchs then proceeded to betray secrets about the development of nuclear weaponry to his Soviet controllers, both in the UK and the USA. He was identified by decrypted Soviet Embassy traffic in 1949, persuaded to confess, and in early 1950 was convicted of offences against the Official Secrets Act.)

One of the rarest books in my library must be a volume titled The British Connection, by Richard Deacon, which appeared in 1979. It looks to be a harmless publication, subtitled Russia’s Manipulation of British Individuals and Institutions – a subject obviously close to my research interests. I recall buying it via abebooks a few years ago, from Bradford Libraries, Archives and Information Services. A stamp indicates that it was ‘withdrawn’ at some stage, but the fact that it had been issued its Dewey categorization number, 327.120947, suggests that it may have rested on the library shelves for a while. A small square of paper stuck to the inside of the back cover includes the numbers 817 563 779 5, and the letters W/D handwritten underneath. Perhaps an enterprising young librarian decided to place it in the archive, and later, when all memory of the surrounding events had passed, the authorities decided to sell off surplus stock.

For all copies of The British Connection were supposed to have been withdrawn and pulped. The publishers, Hamish Hamilton, under threat from a lawsuit by Sir Rudolf Peierls, submitted to the claim that a libel had been written against the physicist’s good name. As Peierls himself wrote of Deacon’s book, in his 1985 memoir Bird of Passage (pp 324-325):

“It contained many unsubstantiated allegations against well-known people, including, for example, a completely unfounded slur on Lise Meitner, the well-known nuclear physicist. But nearly all the individuals mentioned were no longer alive, since in English law there is no libel against dead people. But for some reason the author thought I was dead, too, and made some extremely damning and quite unjustified statements about me.

Because of this I was able to take legal action very early, and a writ was served on the publishers and the author a few days after publication. The matter was settled out of court very promptly; the distribution of the book was stopped at once, so that the few copies that were sold are now collector’s items. I received a ‘substantial sum’ by way of damages. The speed of action was impressive: the settlement was announced in the High Court just thirteen days after I first consulted my solicitors. The publishers could have reissued the book in amended form, but they decided to abandon it.”

A

few copies must have escaped, however, which makes one wonder how rigorous the

process was. The Spectator even managed to commission the journalist

Andrew Boyle (the author of The Climate of Treason) to review it. In its

issue of July 21, 1979, in a piece titled Unnamed Names,

(http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/21st-july-1979/19/unnamed-names ), Boyle drew attention

to the book’s ‘unsightly scar tissues of transplanting and overhasty cutting’.

He expressed doubts about Deacon’s allegations concerning Pigou, Tomàs Harris and Clark Kerr, but overlooked the Peierls

references. The British Connection is still available at several

second-hand booksellers, and also at prominent libraries, so Peierls may have

been misled about the severity of the censors’ role.

I cited this whole incident in Misdefending the Realm (pp 206-207), but believe now that I identified the wrong passage as the offensive slur. I concentrated on Deacon’s statement that ‘Peierls was one of the first to be suspected’ (after the acknowledgment by the British government that there had been leakages by scientists to the Russians), and pointed out that it was an undeniable fact that Peierls had come under suspicion, as the voluminous records on Peierls at the National Archives prove. Yet, after I sent scans of the relevant pages to Frank Close, the biographer of Bruno Pontecorvo and Klaus Fuchs (who had not been able to read the book), we realized, when I discussed the text with him, that another passage was probably much more sensitive. (Three years ago, Close shared some thoughts with me about the passage, but asked me not to promulgate them. These comments thus represent my own reactions.)

I shall not quote Deacon’s statements verbatim – which might be construed as repeating a libel, even though the victim is dead. He implied that a source of intelligence on the atom spies in the late 1940s was Alexander Foote, whom regular readers of this website will recognize as an important figure in the saga of ‘Sonia’s Radio’. Foote had been trained as a wireless operator by Sonia, and had worked in Switzerland as an illicit transmitter during the war until his incarceration in 1943. After the war, he had been summoned to the Soviet Union, a directive he bravely accepted, where the KGB/GRU grilled him. Convinced of his loyalty, however, Moscow then despatched him on a mission to South America. Foote ‘defected’ to the British in Berlin in July 1947. He was interrogated, and then brought back to Britain. (See Sonia’s Radio: Part VI)

The essence of Deacon’s information was a ‘hitherto unpublished’ statement made by Foote, who had been extremely upset by the perceived lack of interest in what he had to say to his interviewers (or interrogators) from MI5 after his experiences in Moscow. Foote claimed he was obstructed in his attempts to warn the Home Secretary of the fact that MI5 had been negligent in its surveillance of Ursula (Sonia) and her husband, Len Beurton, despite repeated approaches through private letters and interviews to members of Parliament. The most provocative claim that Deacon listed was that Foote had been fully aware, by the late 1940s, that the important figures in Zabotin’s network in the USA and Canada were Nunn May and Fuchs, and that Foote also believed that Peierls had also played a role in this network, although not such a risky one as Fuchs or May. Had Foote picked up this intelligence in Moscow? In any case, this was probably the accusation that provoked Peierls to invoke his solicitors.

One needs to be a bit careful with Foote. He no doubt had a grudge with the way he had been treated by MI6 (who, I believe, had been his employers), and probably expected to be treated as a hero on his return, rather than with the evident suspicion that he faced, mainly from MI5 officers who were not aware of his MI6 connections. He was also probably by then under a death-sentence from Moscow, which must have disturbed his equilibrium. Yet his personal loyalties were not as clear-cut as he made out. One of Deacon’s key statements is that ‘Foote himself was convinced that the vital information he gave the British authorities concerning the Beurtons, then living in Oxford, was passed back to the couple through someone in MI5 so that they were able to escape to East Germany before action was taken.’ We now know that MI5 had kept a watch of some sorts on the Beurtons, and evidently knew what they were up to – but chose to do nothing – and that Sonia and Len made their escape to East Germany immediately they heard of Fuchs’s arrest. No ‘action’ was ever intended, as MI5 knew what the Beurtons were up to when Foote broke the news to them. And, presumably out of affection for his instructor in Switzerland, Foote himself had vicariously sent a warning message to Sonia.

I carefully stated in Misdefending the Realm that I believed that Peierls was never engaged in direct espionage himself, but that he was probably an ‘agent of influence’ who, for whatever reasons, abetted Fuchs in his efforts to steal atomic secrets. I have identified multiple patterns of activity and testimony that contribute to this opinion, not least of which is the fact that a file exists at The National Archives (or, more correctly, in some government office, presumably the Home Office) that is titled ‘Espionage Activities by Individuals: Rudolf Peierls and Klaus Fuchs’, and is identified as HO 523/3. The record has been retained by the Government Department in question: I have made a Freedom of Information Request, but am not hopeful that it will be declassified because of my beseechings. What intrigues me is that the title does not say ‘Suspected Espionage . . .’ or ‘Investigation into Claims of Espionage . . .’, but simply ‘Espionage Activities’. If Deacon’s claims can still be considered erroneous, is it not strange that the British authorities would publicize the fact that they have retained a file that explicitly makes the same claim that he did?

Other documentary evidence that cries out for a re-assessment of Peierls’s role consists of the following: his own memoir, which elides over, or misrepresents, some very important events in his life; the large files at The National Archive that are publicly available, which point out many contradictions in his and his wife’s stories; the FBI files on Peierls and his wife that point out contradictions in their stories; the memoirs and biographies of other scientists, which highlight some anomalies, especially in Peierls’ awareness of Fuchs’s early communist activities, and whether he ignored them; accounts from the former Soviet Union, which point out a distressing way in which western scientists were manipulated and threatened; facts concerning Peierls’ courting of, marriage to, and escape with, his wife, who was born in Leningrad; and the details of Peierls’ highly controversial visits to the Soviet Union, including one at the peak of the Great Terror, in 1937, that he attempted to conceal at the time. It is the last two aspects on which I focus in this coldspur article.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

On August 30, 1918, Moisei Uritsky, the head of the Petrograd branch of the Russian secret police, the Cheka, was murdered by a young Socialist-Revolutionary. The next day (according to some accounts, a couple of weeks later, according to others, confusion over which may be attributable to hesitation over adopting the New Style calendar), another Socialist-Revolutionary, Fanya Kaplan, fired at Lenin himself, seriously wounding him, but not mortally. She was very short-sighted, and may have struggled to line up her target. These two events provoked Lenin to activate what has been called the ‘Red Terror’ – a frightful orgy of executions of thousands who could be considered enemies of the Bolsheviks. Robert Service, in his History of Twentieth-Century Russia, wrote: “According to official records, 12,733 prisoners were killed by the Cheka in 1918-19; but other estimates put the figure as high as 300,000.”

Some histories suggest that Lenin had been preparing for a fierce campaign of elimination of groups hostile to the Revolution for a while beforehand, and that he might even have set up the assassination of Uritsky as a justification for extreme measures. (Uritsky had been a Menshevik before joining the Bolsheviks, so he might have been considered expendable.) Uritsky had, however, gained a reputation for extreme cruelty, and enjoying the task of murdering aristocrats and members of the bourgeoisie. The man who killed him, with only one of eighteen shots finding his target, was a military cadet named Leonid Kannegiesser, a sensitive bisexual poet. Kannegiesser had been embittered and enraged when Uritsky killed his boyfriend in the Army, Victor Pereltsweig, that summer. Robert Payne, in his biography of Lenin, stated that Kannegiesser had also been revolted by the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and the fact that so many of the Bolsheviks were Jewish. Kannegiesser was cool enough to have spoken to Uritsky on the telephone the day he killed him, and to have played chess with his father an hour before the deed.

The Kannegiesser household had been a popular venue for artists and poets to meet. In his study Marina Tsvetaeva, The Woman, Her World, and Her Poetry, Simon Karlinsky writes: “The Kannegiser [sic: many variant spellings exist] home was a major artistic and literary center of the northern capital. Numerous writers of the Russian emigration were to remember it in their memoirs. Tsvetaeva saw a great deal of the Kannegiser family during that visit and became especially friendly with the elder son, Sergei. But she also got to meet the younger son, Leonid, a budding poet and a close friend of the celebrated peasant poet Sergei Esenin. (Tsvetaeva strongly intimates in ‘An Otherworldly Evening’ that Esenin and Kannegiser were lovers at the time of her visit, a supposition supported by a close reading of their respective poems of the summer of 1916.)”

After the attack, Kannegiesser escaped by bicycle to the English Club. Some reports say that he was a British spy, and Bruce Lockhart, in his Memoirs of a British Agent, recounts how, immediately after the attacks, he and Captain Hicks were arrested and taken to the Lubianka under suspicion of being accomplices. In any case, Kannegiesser was quickly arrested when he reappeared from the Club in a longcoat, a weak disguise. After torture, he was executed in October 1918. Yet his guilt and ignominy spread further, both among his artistic circle and his immediate family. In her record of the time Memories: From Moscow to the Black Sea, Teffi (the pseudonym of Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya), the author wrote that Kannegiesser contacted her a few days before the assassination, hinting that he was being followed, and that he did not want his pursuers to be able to track him to Teffi’s apartment. The poet Marina Tsvetsaeva explained in her Earthly Signs that Kannegiesser had been a childhood friend, and when she mentions it on a mission to barter goods for grain soon after Uritsky’s death, a Communist severely reproaches her. Nadezhda Mandelstam, in Hope Against Hope, relates how her husband Osip had met Kannegiesser, shortly before the deed, in Boris Pronin’s Stray Dog, which was a cabaret/club where all the leading poets of the day got together to recite. These associations surely tainted the police-record of Kannegiesser’s friends.

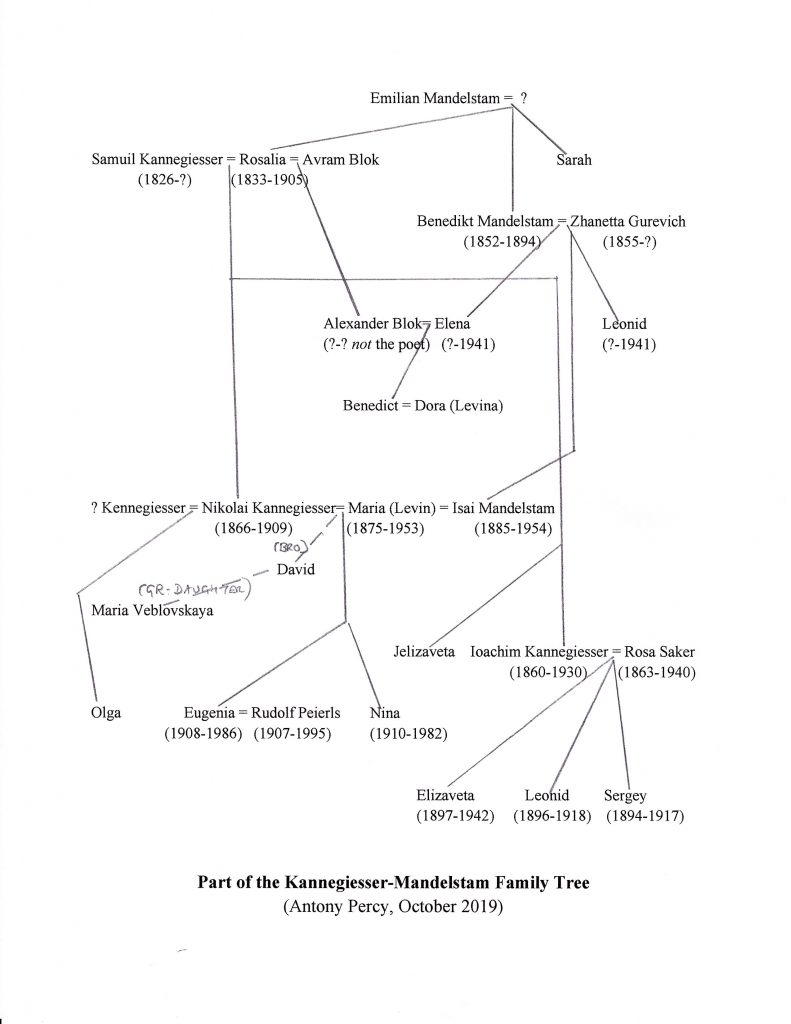

Reprisals were swift. Ivan Bunin, in Cursed Days, wrote that ‘a thousand absolutely innocent people’ were killed in retaliation for the murder of Uritsky. Kannegiesser’s telephone book was found on him, with nearly five hundred names in it, with the result that many of his relatives and friends, and other people in the list, were immediately arrested. Mark Aldanov, who also knew Kannegiesser well, and published an account of the event from Paris in the 1920s, wrote that a thousand persons were killed in two days in early September. Kannegiesser’s father was taken in the same day of the murder: his aunt’s second husband (Isai Mandelstam, a distant relation of the famous poet, Osip) the following day. His parents (Ioachim and Rosa, née Saker) were interrogated for months before being released in December, and they would be persecuted for years. Kannegiesser’s older brother, Sergey, had committed suicide in 1917, but the no doubt distraught couple was allowed to leave the country in 1924 with their sole remaining child Elisaveta (who would later die in Auschwitz). Isai Mandelstam was exiled and persecuted for decades. He was lucky, I suppose, not to have been shot, unlike Osip, who died on his way to the camps, in 1938.

Iochaim Kannegiesser, an engineer, was the son of Samuil Kannegiesser, a medical doctor, and Rosalia Mandelstam, who lived in St. Petersburg. To show how tightly bound the families of Kannegiesser and Mandelstam were (interleaving with the Levins and Bloks, also), Rosalia’s brother Benedikt, who married one Zhanetta Gurevich, had three offspring, one of whom, Elena, married Rosalia’s son, Alexander – from her second marriage to Avram Blok – while another was the same Isai mentioned earlier. [See the family tree below for clarification.] Moreover, Samuil and Rosalia had another son, Nikolai, who became a famous gynaecologist. He married Maria (another Levin), and had two daughters. But the genealogical record shows that Nikolai had another daughter, Olga, whose mother was apparently named ‘Kennegiesser’ (another variant). Whether from a previous marriage, or a child born out of wedlock, is not clear. Nikolai died from septicaemia in 1909, and his widow then married Isai Mandelstam, the very same individual mentioned above. Isai was an electrical engineer, but he had a flair for languages, and engaged in translations of western classics for much of his life.

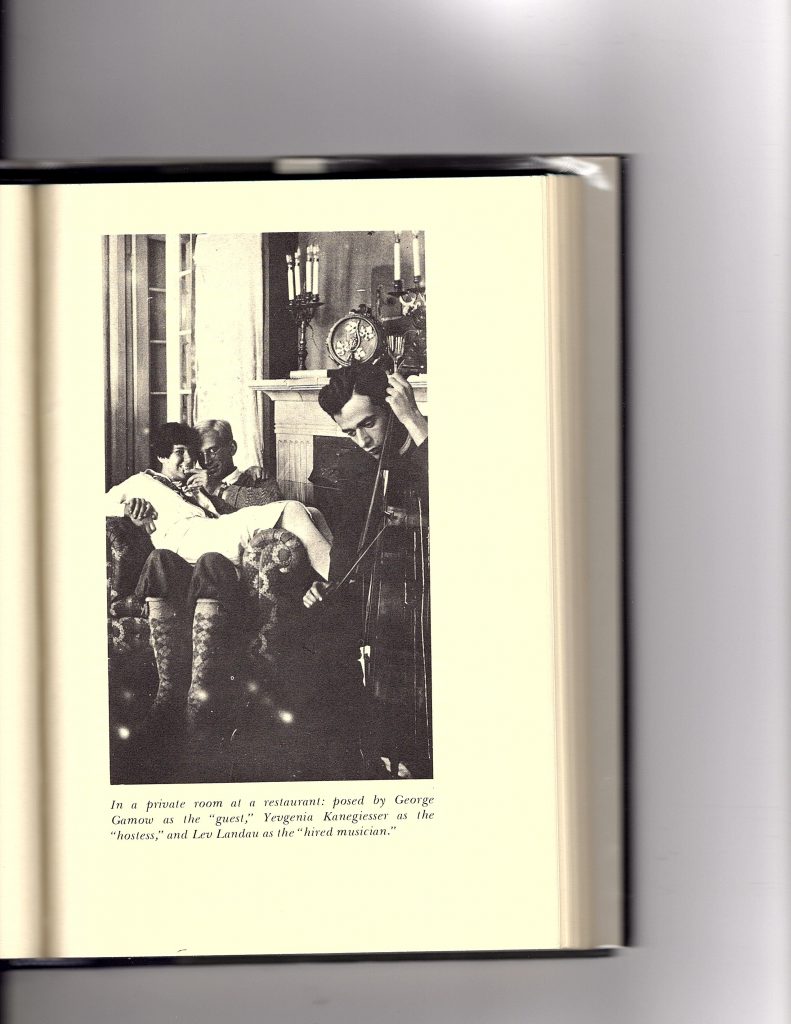

Nikolai’s premature death, at the age of 43, meant that his first daughter, Eugenia, was not yet two when he died, while his second daughter, Nina was born posthumously. Eugenia became a physics student at the University of Leningrad (as St. Petersburg, next Petrograd, had now been named), and was an exact contemporary of the future Nobelist Lev Landau. The two of them joined up with other young physicists, George Gamow, Dmitri Ivanenko, and, later on, Matvei Bronstein, in a group known as the ‘Jazz Band’. Bronstein was killed in the purges of 1938; Landau was arrested the same year and freed only on the intervention of the influential and courageous physicist Pyotr Kapitza; Ivanenko was arrested in 1935, but survived until 1994. In 1930, from August 19th to the 24th, the All-Union Congress of Physicists was held in Odessa. It was attended by Eugenia Kannegiesser, Gamow and Landau, as well as by several foreign guests. Amongst these was Rudolf Peierls, attending as an assistant to the Austrian theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who was introduced to Eugenia. They fell in love, were married in Leningrad the following year, and after some bureaucratic hassles and delays, were allowed to emigrate at the end of 1931.

* * * * * * * * * * *

You could have searched in vain for published details of Rudolf Peierls’s connection with the assassin of Moishe Uritsky, and the revenge harboured by Lenin and Stalin against the kin of murderers of the Bolshevik vanguard. Both his Wikipedia entry and his citation in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biograph, simply refer to his encounter with Genia, and their subsequent marriage. In his memoir Bird of Passage, written as late as 1985, Peierls merely ascribes his invitation to Odessa, even though he was not at that time a scientist of renown, to Yakov Frenkel, a prominent member of the Ioffe Physico-Technical Institute in Leningrad. (Abram Ioffe was also at the conference in Odessa.) Peierls describes how he met Genia (‘a recent physics graduate’) on the beach at Lusanovka, but does not mention George Gamow in this context, even though a photograph from the Segré archive shows him, Gamow and Ioffe talking together in Odessa. Gamow and Genia had been close friends for a while, as the photograph below, taken from Gamow’s autobiography, shows.

(The very perceptive follower of these events might have noticed, in an article by Sabine Lee in the Winter 2002 issue of Intelligence and National Security titled The spy that never was, an observation that Peierls ‘had enough reasons for hating their [the Soviets’] system like poison’, with a clarification relegated to a footnote that ran as follows: “His wife’s family had been persecuted by the Stalinist regime, because one of her cousins had been an outspoken counter-revolutionary who had assassinated the then head of the Russian secret policy [sic], Uritzky.” The author, who did not delve deeply into the matter, and was clearly echoing what Peierls himself wrote, used as her source the letter to Viscount Portal found in the Peierls Private Papers held at the Bodleian: the MI5 files on Genia and Rudolf were not declassified until 2004. I shall return to Lee’s article later.)

Thus the account of the couple’s courtship, and trials in managing to gain a visa for Genia, must be viewed with some scepticism. Later, Peierls wrote of a time in 1934: “It was in their [the Shapiros’] house that we awaited a telephone call from Leningrad that brought us some disturbing news. Genia’s parents and her sister, Nina, had been exiled from the city to a small town some distance east of Moscow. One did not have to ask for a reason for this order; exile or arrest were then hazards that struck people at random, like lightning or disease. One tended to speculate about what factors might have contributed to this result, but this would never be known.” This can now be seen as disingenuousness of a high order – and it was before the assassination of Kirov, which did provoke more reprisals. Frank Close, in commenting on Genia’s reaction to Fuchs’s arrest in Trinity, states simply: “In Russia, members of Genia’s family had been incarcerated on the whims of the authorities.” There was random terror in Stalin’s Russia, but Stalin’s organs carried out more carefully targeted campaigns. Peierls undoubtedly knew the reasons.

I had found only one clue indicating that Peierls ever admitted that a dark cloud hung over his relationship with the Soviet government. It is to be found in one of the files on Peierls at the National Archives, namely KV 2/1662. After accusations had been made against Peierls in early 1951 because of his association with two academics at Birmingham University, known to be communists (referred to as ‘Prof. P’ – certainly Roy Pascal, and ‘Dr. B.’ – possibly the economist Alexander Baykov, but more probably Gerry Brown, a former Communist Party member in America, whom Peierls, shortly after Fuchs’s sentencing, had invited to a post at Birmingham University), in April 1951 Peierls had a conversation with Viscount Portal about the relationships. Portal had been chief of the Air Staff during World War II, and was Controller of Production (Atomic Energy) at the Ministry of Supply from 1946 to 1951. In a letter he sent to Portal after their conversation (the same one identified by Sabine Lee), Peierls tried to defend himself against the accusations, suggesting his associations were harmless or short-lived, and then presented the following tentative declaration:

“On the other hand, is it known that my wife is the cousin of Kannegiesser, a counter-revolutionary who assassinated Uritsky, who was then head of the Russian secret police? With the same, very rare surname, she was never allowed to forget this connection. It is known that her family was banished from Leningrad in 1935, partly because of this connection, and partly no doubt because of her marriage to a foreigner. They have not dared communicate with her for several years, and we do not know whether they are still alive.”

Peierls misstates Uritsky’s level of responsibility, but this paragraph is highly important. The scientist used this strange admission to shed doubt about the credibility and intelligence of his accusers, yet dug a pit of his own in so doing. The statement is to me remarkable, for the following reasons:

- His feigned ignorance as to whether the authorities [presumably] knew about Genia’s connection with Leonid. If he had not volunteered the information at any time, why would he expect them to know? And yet, if he seriously considered that it was the responsibility of intelligence organisations to uncover such facts, why was he not surprised that he had not been challenged by the association, given all that had recently happened?

- The claim that Genia was ‘never allowed to forget this connection’. Given that Peierls’ stance was that he and his wife were in complete ignorance of the persecution of her family members, what agency or person was constantly reminding her of the connection? True, she and Rudolf made a return visit to Leningrad in 1934, where she would have learned from her sister and her mother what was happening, but in 1937, at the height of the terror, Peierls went to Moscow alone. Was Genia in touch with members of the Soviet Embassy, and were those the persons who continued to threaten her, and presumably kept her informed on the fate of her relatives?

- The deliberate vagueness of ‘it is known that her family was banished from Leningrad in 1935’. Known by whom? Peierls claimed that, during his oppressive visit to a physics conference in Moscow in 1937, he managed to engineer a meeting with Genia’s sister Nina, who would have updated him on Stalin’s persecution. (Indeed, Stalin probably arranged for this meeting himself, as it would have been fatal for Nina otherwise, Peierls at that time being considered a German spy. I shall discuss this unlikely sequence of events later.) But who else would have known about this state of affairs, unless Peierls himself chose to tell them?

- When Peierls came to write his memoir, over thirty years later, he chose to overlook this particular exchange as he told his life-story, no doubt believing that the unfortunate episode and its aftermath were safely buried by then. Perhaps he thought the letter to Viscount Portal would never come to light.

We have no exact record of how Portal responded, but the outcome was favourable for Peierls. (The story of revenge executed on family members of defectors and enemies should have been known to MI5: Walter Krivitsky’s three brothers-in-law were killed after he and his second wife Tonia escaped to Canada, and he published his articles denouncing Stalin.) By March 1954, F3 in MI5 was able to confirm the Uritsky story, but also concluded that there was no doubt as to Peierls’s loyalty. Rudolf Peierls was knighted in 1968, and a succession of honours and medals followed. He died in 1995. In 2004, the building housing the sub-department of Theoretical Physics at Oxford University was named the Rudolf Peierls Centre.

I had essentially finished the research that appears above by October 1 of this year. That day the book Love and Physics landed on my doorstep. Subtitled The Peierlses, it was published earlier this year, and is the work of a professional Russian-speaking theoretical physicist, Mikhail Shifman, now a professor at the University of Minnesota. (From information in Shifman’s book, I have been able to extend the details on the family tree I created, which is richer than the one Shifman offers, but not so extended. Otherwise, the research is my own.) Love and Physics is a valuable addition to the Peierls lore, since it combines letters written between Rudolf and Genia (extracted from Sabine Lee’s compilation of the correspondence), items from Rudolf’s diaries, reminiscences from such as Genia’s sister, Landau’s students, and the Peierlses’ friends, as well as archival material from both Russian, American and English sources (including the complete text of the notable letter to Viscount Portal quoted earlier.) Remarkably, it also contains the text of letters sent by Genia’s mother and stepfather, exiled to Ufa, from 1936, and a photograph of a postcard sent by Genia on November 25, 1936 to them. This correspondence presumably ended with the onset of the Great Terror, but the Soviet censors were surely familiar with its contents.

Yet Shifman singularly fails to interpret the material synthetically. The volume is essentially a scrapbook – a very rich scrapbook, but still a scrapbook. (I learned towards the end of this month that Love and Physics has been withdrawn by its publisher, because of copyright infringements. So now I own another rarity.) The various escapes (of the Peierlses, of Gamow, even of Landau) are ascribed to miraculous intervention. Shifman sees no anomalies in the fact of Peierls’s being invited to a conference in Moscow during the Great Terror at the same time that Isai Mandelstam was being interrogated in jail about Peierls’s activities as a spy. He seems completely unaware of the work of Pavel Sudoplatov, who boasted of engaging scientists in the West to provide secret information under the threat of their relatives being harmed. He criticises Peierls for being ‘naïve’ in helping carry out the Soviet Union’s message of ‘Peace’ over nuclear weapons after the war, but delves no further. The Uritsky episode is described in detail, but he makes no linkage between Genia’s plight, or the conflict in Peierls’s own testimony about the connection. The volume has been put together with the intent of gaining ‘re-assurance’ from various witnesses and participants that Peierls’s role was entirely honourable.

Shifman does refer, however, to one significant event in the saga. On May 29, 1999 the weekly magazine the Spectator carried an article by Nicholas Farrell which picked up the necessarily abandoned claim by Richard Deacon that Peierls had been a spy. Commentators have assumed that Farrell gained his information from the historian of intelligence Nigel West, who had recently published his book on the VENONA project. On the assumption that the identities behind the cryptonyms FOGEL/PERS and TINA were Rudolf and Genia Peierls, the author took advantage of the fact that Peierls was now dead to try to breathe fresh life into the theory that the couple had been working for the Soviets. It should be remembered that Nigel West had been a researcher for Richard Deacon as a young man, and Deacon’s stifled accusations probably still resonated strongly with West. Unfortunately, the identification was a mistake (and in Misdefending the Realm, I unfortunately echoed the Farrell/West hypothesis). The Spectator article was carelessly prepared, and overemotionally presented. Later research showed that TINA was Melita Norwood, PERS was Russell McNutt, and MLAD was Theodore Hall.

In 2002, Professor Sabine Lee, now Professor of Modern History at the University of Birmingham, the institution at which Peierls spent most of his academic life, published the article referred to earlier, The spy who never was. It stated as its objective the investigation of the claims that Peierls and his wife had spied for the Soviet Union. (Lee made an acknowledgment of thanks to the British Academy for supporting the research on which the article was based: why the British Academy felt it had to get involved with such an endeavour is not clear to me, since the piece appears only to exploit information available at the Peierls Archive at the Bodleian Library, and on the MI5 files on Peierls and Fuchs accessible online from the National Archives. Lee’s Acknowledgments in her editions of Peierls’s Letters credit both the British Academy and the Royal Society for funding the project, which is a phenomenon worthy of analysis some other time.) Lee painstakingly took her readers through Peierls’s career and his relationship with Fuchs, and, concentrating on the erroneous assumption concerning VENONA, treated these items as the only significant evidence for the prosecution. Yet she omitted to analyse all the other incriminating evidence: hers was a whitewash job that showed that she failed to understand the complexity and subterfuge of the agencies of Soviet intelligence, and the strains that many western scientists were put under. Lee correctly dismantled the Farrell/West allegations, but failed to address the core of the matter.

Thus a triad of academics has lined itself up to protect Peierls’s reputation: Frank Close, the author of Trinity, who was taught by Peierls at Oxford University; Sabine Lee, who is the lead historian at Peierls’ primary seat of learning, the University of Birmingham, and has edited a comprehensive set of the Peierlses’ letters, as well as a biographical sketch of Peierls (which appears in Shifman’s book); and Mikhail Shifman, whose thesis adviser at the Institute of Theoretical and Experimental Physics in Moscow was Professor Boris Ioffe, who worked under Kurchatov when Fuchs was supplying purloined information to the Institute. (Ioffe may have been a distant relation of the first director of the Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Abram Ioffe, who chaired the notorious 1937 conference in Moscow attended by Peierls.) Shifman comes to no outright conclusion on Peierls, but he is very respectful of Lee’s expertise and research, and admits to looking for ‘reassurance’ about Peierls’s loyalty from both Lee and the Peierlses’ offspring. Lee admits to having been much inspired by Peierls’s former protégé, the communist Gerald Brown: her edition of the Peierls-Bethe Letters is dedicated to him. None of these three writers appears to be familiar with the memoirs of Pavel Sudoplatov, Special Tasks, which outlined the strategies of issuing personal threats adopted by Soviet Intelligence to aid the country’s atomic weapons research.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

I wrote about Sudoplatov’s statement in a posting of three years ago: ‘Mann Overboard’. It is worth reproducing the extract in full again here. Pavel Sudoplatov was deputy director of Foreign Intelligence of the NKVD from 1939 until 1942, and in July 1941 was appointed director of the Administration of Special Tasks. ‘Special Tasks’ involved both assassination abroad (Sudoplatov had personally killed Konovalets in Rotterdam in 1938, and had supervised the assassination of Trotsky in 1940, so he was well qualified for the job), and stealing of secrets to assist the Soviet atomic bomb project. Sudoplatov wrote:

“There was one respected scientist we targeted with both personal threats and appeals to his antifascism, George Gamow, a Russian-born physicist who defected to the United States in 1933 when he was permitted to leave the Soviet Union to attend an international meeting of physicists in Brussels, played an important role in helping us to obtain American atomic bomb secrets. Academician Ioffe spotted Gamow because of his connections with Niels Bohr and the American physicists. We assigned Sam Semyonov and Elizabeth Zarubina to enlist his cooperation. With a letter from Academician Ioffe, Elizabeth approached Gamow through his wife, Rho, who was also a physicist. She and her husband were vulnerable because of their concern for relatives in the Soviet Union. Gamow taught physics at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and instituted the annual Washington Conference on theoretical Physics, which brought together the best physicists to discuss the latest developments at small meetings.

We were able to take advantage of the network of colleagues that Gamow had established. Using implied threats against Gamow’s relatives in Russia, Elizabeth Zarubina pressured him into cooperating with us. In exchange for safety and material support for his relatives, Gamow provided the names of left-wing scientists who might be recruited to supply secret information.” (Special Tasks, p 192; published 1994)

Sudoplatov’s account has been challenged: he did get names of some spies wrong, for instance, but most of it has been confirmed by other sources. (Sudoplatov’s disclosures provoked wrath from some diehard KGB officers.) He does not specifically identify the Peierlses as targets, but Genia’s intimate friend Gamow had almost certainly been recruited in the Soviet Union: the comic-opera story of his plans to escape the country, followed by an absurd plea made to Molotov, can be inspected in my piece ‘Mann Overboard’. The prolonged delay of six months after the Peierls marriage before Genia’s exit visa was approved indicates that the decision was made only after very careful planning, with sign-off occurring at the highest level. In a testimony provided to Shifman by the scientist Freeman Dyson, the latter wrote of Genia’s ‘long experience of living in fear of the Soviet police’, which indicates that she and Rudolf confided to their closest friends how they were being threatened.

Yet even the somewhat starry-eyed Shifman shows a realistic assessment of the horrors of 1937, when he describes the intensification of the Great Terror in July of that year, and directly echoes Sudoplatov’s claims:

“Working on my previous book, Physics in a Mad World, I looked through a notable number of files from the archive of the German and Austrian sections of the Comintern. This archive is now kept in the Russian State Archive of Social and Political History (RGASPI) in the public domain. I was amazed by the number of German and Austrian communists who were agents of the Comintern in Western Europe and carried out the order of Stalin with an iron fist. In many dossiers there is a note ‘performed special assignments’. ‘Special assignments’ is a euphemism that could mean anything: from espionage to discrediting opponents among Russian emigres, from eliminating disobedient agents, to assassinating defectors from the ‘socialist paradise,’ Trotskyists (and Trotsky himself), and other ‘undesirable elements’.”

“In 1934-36, many of the Comintern agents fled or were recalled to Moscow, and almost all disappeared in 1937-38: they were either sent to Gulag, or were executed immediately after their arrest by the NKVD.” (Love and Physics, p 265). There were other emotions than Love involved with Physics, for sure.

Thus Rudolf Peierls’s extraordinary trip to Moscow in the autumn of 1937 has to be analysed very closely. What was he thinking, walking into the lions’ den, still a German citizen who knew that the Germany Embassy would not come to his aid if anything untoward happened, at a time when Stalin was persecuting Germans scientists, especially those of Jewish origin? I start with Peierls’s account of the enterprise:

“In the summer of 1937 I was invited to a nuclear physics conference in Moscow, and Genia planned to come with me. But we were warned that her presence might prove an embarrassment to her friends and relatives, so she did not go. I went by myself, stopping for a week in Copenhagen. I then went . . . to Leningrad, where I met Genia’s sister, Nina, who had by then been allowed to return to Leningrad. Landau was very worried by the state of affairs, a fact he mentioned only when we were walking in a park, and were secure from being overheard. Nevertheless, the scientific discussions at the conference itself were normal and fruitful.” (Bird of Passage, pp 129-130)

A dissertation could probably be written on this paragraph alone, given the numerous items that are left unsaid. Now that historians can pick up so much more background to the events in the Soviet Union and Copenhagen at the time, multiple questions have to be posed as to the accuracy of Peierls’s statement, from the circumstances of his departure to the question of whether, given the flimsiness of his account of it, he even attended the conference. I organize these questions around the following five subjects: 1) Arrangements for travel; 2) Logistics of the conferences; 3) The political climate in the Soviet Union; 4) Proceedings in Moscow; and 5) The meeting with Nina.

Arrangements for Travel

Remarkably, Sabine Lee completely overlooks the 1937 Moscow visit in her biographical sketch. This oversight is doubly strange because Peierls assumed his new position as Professor of Mathematical Physics at Birmingham University in October 1937. (He was offered the chair, in the spring of 1937, by Professor Mark Oliphant, who himself did not take up his chair of physics at Birmingham until the same month.) The Conference in Moscow took place from September 20th to the 26th. I suspect no record of the exchange between the organisers of the conference and the Peierlses exists (if indeed it was conducted by mail), but the event conveniently fell between the end of Rudolf’s period at the Mond Laboratory, where his position had been financed by the availability of funds released by the unexpected detention of Pyotr Kapitza in the Soviet Union, and the assumption of his new post.

So who warned Rudolf and Genia that Genia’s presence might prove ‘an embarrassment’ to her friends and relatives? That gesture showed an unusual amount of sensitivity and compassion on the behalf of the Soviet authorities. Given, however, that Genia’s parents were at that time in disgrace, exiled in Ufa, it seems unlikely that they would have been discomfited further by the presence of Genia in Moscow, unless, of course, the physicist’s wife made some sort of public protest – a highly unlikely happening. It would appear to me that Genia would have been mortally afraid of returning to the Soviet Union at this time, and might even have attempted to persuade her husband from going, had she not been aware that his summoning was a vital part of any arrangement made to protect her family from the direst outcome.

As will be shown, Rudolf combined his excursion with a visit to Copenhagen, which contains its own contradictions. Moreover, Rudolf was clearly aware that a visit to Moscow at this time might provoke some difficult questions from his British hosts. He must have gained a Soviet visa (his German passport had been renewed in Liverpool in 1934, for a period of five years), because an alert customs official at Harwich noticed the Soviet stamps in his passport – but not until Peierls returned from a holiday, ‘spending his Easter vacation’ in Copenhagen, in April 1938. As part of the report on his arrival at Harwich declares: “During the examination of his passport it was noticed that it contained a Soviet visa and Russian control-stamps for 1937, but the alien, when questioned, beyond confirming that he had visited the U.S.S.R. last year, did not appear to be willing to give any reason for his visit to that country, and, in view of his substantial position as a professor, Peierls was not further questioned on the subject.” (TNA, KV 2/1658/2, serial 1A)

Why Peierls should have to behave so furtively about a legitimate conference in Moscow is not clear. Had he perhaps concealed the whole adventure from his new supervisor, Professor Oliphant? One would have thought that the timing of the conference was excellent cover for whatever other business he had to attend to in the Soviet Union, about which he was clearly diffident to talk. If he had given a straight answer, perhaps no report would have been filed, and no one would have been any the wiser. Instead, MI5 opened a file on him, one that eventually ran to eight bulky folders.

One other aspect that has not been analysed properly is the financing of Rudolf’s and Genia’s travel in the 1930s. It was not as if they were flush with money, yet they flitted around Europe and the Soviet Union with seeming ease. Shifman informs us (via Sabine Lee) that Rudolf’s father, Heinrich ‘provided some financial support to the young family, through wire transfers first to Switzerland and then to England, within the limits imposed by the Nazi government of Germany’, but Henrich was very cautious. He had not approved of Rudolf’s marriage in the first place, and he regarded their ventures to the Soviet Union as risky and hazardous. It was unlikely that, under these circumstances, he underwrote their extensive voyages, many of which were not even traced at the time.

For example, Sabine Lee’s edition of the Peierlses’ Letters (Volume 1) proves that Rudolf and Genia engaged in a lengthy and enigmatic visit to the Soviet Union in 1932 (completely ignored in Bird of Passage, which is an astonishing lapse), when Rudolf had already expressed how difficult it would be for the married couple to survive in Zürich on his meager salary after their marriage. For some reason, in the spring of 1932, Rudolf went to Moscow without Genia, and there applied for a visa for his wife to join him. It took so long that he had to leave the Soviet Union before Genia gained her visa, after which she was able to travel to Leningrad to stay there several weeks without him. (In the interview with Weiner [see below], he deceptively stated that he ‘came back earlier than my wife, who was staying longer’.) It sounds very much as if the granting of Genia’s visa was conditional on some effort or commitment by Rudolf. (Professor Lee offers no commentary at all on this highly controversial visit.) MI5 slipped up massively in not pursuing aggressively Kim Philby’s source of funding when he was sent as a journalist to Spain in early 1937. It probably should have been more pertinacious in ‘following the money’ when it came to the Peierlses’ travel arrangements. Yet the Security Service probably knew nothing about these journeys at the time: Rudolf and Genia were not yet resident in the United Kingdom.

Conference Logistics

Elsewhere, Peierls has given some vague descriptions of the movements of that summer, so threadbare that one might be justified in wondering whether he did in fact attend it. We owe it, however, to Paul Josephson, in his book Physics and Politics in Revolutionary Russia (1991) to confirm that Peierls did actually attend the conference. “The second all-union conference on the atomic nucleus, held in Moscow late in September 1937, drew over 120 Soviet scholars, and several physicists from abroad including Wolfgang Pauli, Rudolph Peierls, a longtime associate of L.D. Landau, and Fritz Houtermans”, he wrote. Josephson cites official Russian records in his footnotes to this passage in Chapter 6, so this account can presumably be trusted. Yet Josephson does not mention Bohr, whose presence would certainly have been sought in normal circumstances, given his prominence and reputation. Izvestia sent him telegrams in November 1937, seeking his opinions on Landau’s discoveries, which indicates the level of regard in which he was held in Moscow. Bohr had spent some time in the Soviet Union in the summer of 1937, however, lecturing, and meeting Kapitza, so he presumably did not need to return so soon.

Peierls indicates very clearly that he spent a week in Copenhagen first, before advancing through Stockholm and Leningrad. Presumably that week must have taken place in the first half of September. But what was the purpose, and whom did he meet? It is very odd that he does not mention an important Scientific Conference reportedly organised by Niels Bohr, of which a very famous photograph exists, with Peierls sitting among many luminaries in the second row [see below]. Shifman reproduces this photograph, with the caption “The famous A auditorium of the NBI: Photograph by Nordisk Pressefoto, Niels Bohr Institute, courtesy of the AIP Emilio Segré Visual Archive, Fermi Film Collection, and Niels Bohr Archive, Copenhagen.” It all sounds very authentic – but the occasion is undated. (This image, with attendees named in manuscript, can be found, but it has a question mark after ‘1937’.) In her commentary to the Letters, Sabine Lee indicates that Genia accompanied Rudolf to a conference in Copenhagen at the beginning of September – a fact that appears to be confirmed by a reference in a letter to Rudolf from his father – after which Rudolf proceeded to Moscow alone, but no details are given. And in that case, why did Rudolf write that he ‘went by myself, stopping for a week in Copenhagen’? Was a meeting in Copenhagen a cover for a visit to Moscow?

Searching for details of the Niels Bohr conference on the web is a mostly fruitless task: the photograph is the most regularly cited item. One rare specific reference to a Bohr conference that autumn comes from N. L. Krementsov, who, in his International Science Between the Wars: The Case for Genetics, writes: “Just a few weeks earlier, in mid-November [1937], he [Otto Mohr] had spent several days with Muller in Copenhagen (at a conference organized by Niels Bohr) . . . ” But mid-November does not work with Peierls’s calendar. Another famous photograph shows Niels Bohr chatting with Werner Heisenberg in Copenhagen some time in 1937, yet again it is sadly undated. (Bohr’s Collected Works confirm that a meeting of the Copenhagen Academy was held on November 19: it states that the photograph was taken at Fredericksborg Castle.) The scene looks as if it were a conference, at some kind of open-air cocktail party: most of the attendees are wearing overcoats. But I find it extraordinary that, if so many famous scientists were assembled at such a critical time, there would not be some more tangible and reliable record of the proceedings.

Peierls added to the confusion by explaining, in Nuclear Physics 1919-1952, a work he edited, that Bohr was on a lecture tour of Japan in the early summer of 1937, and in June gave an address on nuclear physics in Moscow during his return home. In October 1937 he apparently spoke at the Congrès de Paris, but Ruth Moore, one of Bohr’s biographers, informs us that ‘in late September, not long after the Bohrs had returned to Copenhagen, Bohr went to Bologna, to attend the centenary [sic] celebration for Galvani.’ Abraham Pais, however, records that the Bohrs returned home as early as June 25: Moore’s ‘not long’ has to be interpreted vaguely. Further research indicates that the actual bicentennial of Galvani’s birth occurred on September 9, but the event was celebrated between October 17th and the 20th . Moore continues by stating that Bohr was expecting to see Ernest Rutherford in Bologna, but there learned that Rutherford had died after a fall from a tree. (The dates now mesh.) Bohr thus rushed to England for the funeral service shortly after Rutherford’s death on October 19. No mention is made of a conference in Copenhagen amid all these activities.

Thus the facts about the Copenhagen conference, and Bohr’s activities in September, are very elusive and contradictory. No Bohr archival record or biographical work appears to refer to an early September conference: Volume 9 of Bohr’s Complete Works, edited by Peierls himself, contains an entry in its Index for ‘Copenhagen Conferences’, but for years 1932, 1933, 1934, 1936, 1947 and 1952 only. An early trawl through biographies of scientists appearing in the ‘1937’ photograph shows no reference to such an event. (The search will continue.) As I mentioned before, in his memoir, Peierls specifically indicates that he spent a week in Copenhagen before Moscow, in discussions with Bohr, but makes no reference to any conference. In the Letters, however, hints are planted at the holding of such an event, Peierls’s father echoing his son’s description of the coming function. In her own account, Genia travelled to Copenhagen, but then went home. Yet Peierls later wrote that he travelled to Copenhagen alone. In the Letters, Peierls and Hans Bethe discussed Bethe’s visit to Europe that summer, and they planned a ten-day motoring tour in Paris in early September, as Bethe was due to sail back to the United States in the third week of September. The September conference is like a refined version of Schrödinger’s Cat, where the box emblazoned with the photograph of the gathered scientists can be opened, but nothing is to be found inside.

Thus the only recognised conference in Copenhagen that autumn occurred much later, and was noted by Peierls when he edited Volume 9 of Bohr’s Complete Works. He wrote that Bohr delivered a paper back in his hometown in November: “Of a paper read to the Copenhagen Academy on 19 November 1937, only an abstract is published . . .” So was that the occasion when the photograph was taken? If so, how did Peierls manage to attend it? Did he return to Copenhagen in November, fresh in his new post? If so, why did he not describe it? It is all very puzzling: I have written to Professor Sabine Lee to ascertain whether she can shed any light on the matter. In her initial response, she offered to help, but evidently completely missed the point of my questions: she had evidently not inspected coldspur. I followed up with more detailed questions about Peierls’s puzzling movements, and even offered to send her the current draft of this piece, so that she could enjoy a sneak preview.

Professor Lee eventually responded, on October 24. She failed to address my questions, however, simply writing: “As far as I can see, all the issues relating to the Peierlses and security have comprehensively been addressed in many thorough and serious explorations which, in my view, have proved beyond reasonable doubt that there is no question about the integrity of the couple.” I must surely have overlooked some important works. I found this attitude astonishing in its lack of intellectual curiosity, and for its untenable suggestion of ‘proof’, but also thought it a not unusual reaction for an academic with a territory and position to protect. Having appointed herself as the editor of Peierls’s Letters, Lee has shown a disappointing lack of energy in providing useful exegesis: if she encounters an event that can be confirmed by Bird of Passage, she refers us to such a text; if a phenomenon is ignored by Peierls, she likewise ignores it. And she appears to have little understanding of the world of intelligence.

The Political Climate in the Soviet Union

Summer 1937 was a dangerous time in Moscow – especially for Germans. Three major show trials had recently taken place. In August 1936, the prominent Party leaders Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev were among a group of sixteen who had been found guilty of plots against Stalin, and executed. In January 1937, Karl Radek and others were accused of plotting with Nikolai Bukharin against Stalin, Radek delaying his own demise by implicating Bukharin and Marshal Tukahchevsky. Nearly all were executed immediately. In late May, Tukhachevsky was forced to sign a confession that he was a German agent in league with Bukharin in a bid to seize power. He was tried and found guilty on June 11, and executed a few hours later. (Bukharin was executed the following March.) At this stage, Stalin was executing anyone – including his Comintern agents recalled from overseas – who could have been tainted by exposure to Western influences.

Shifman refers to the dangers that German scientists faced at this time. He reports how Hans Hellmann (1903-1938) emigrated to the Soviet Union after being dismissed from the University of Hanover on December 24, 1933. In Moscow, he assumed leadership of the Karpov Institute’s Theoretical Group. On March 9, 1938, however, he was arrested on the charge of spying for Germany, and was sentenced and executed on May 28, 1938. Fritz Noether (1884-1941) was a mathematician who likewise emigrated to the Soviet Union, where he was appointed professor at the University of Tomsk. He was arrested in November 1937, and on October 23, 1938, found guilty of sabotage and spying for Germany. He was sentenced to twenty-five years of Gulag, but executed on September 11, 1941.

Fritz Houtermans, who was described erroneously as a visitor from abroad, attending the conference with Peierls, was a German Communist who had worked for EMI in England – near Cambridge, where Peierls worked – before emigrating to the Soviet Union in 1935. Houtermans’ biographer states that Houtermans was arrested by the NKVD in December 1937. He was tortured and confessed to being a Trotskyist plotter and Gestapo spy (as his charge sheet, reproduced in Mikhail Shifman’s Physics in a Mad World, described), out of fear from threats against his wife, Charlotte. They had married in Tbilisi in August 1930 (or 1931), and Peierls and Pauli had attended the ceremony. However, Charlotte had already escaped from the Soviet Union to Denmark, after which she went to England and finally the USA. On May 2, 1940 Houtermans was extradited to Germany and arrested by the Gestapo at the Soviet-Polish border. Owing to the intervention of another scientist, he was released to work on German nuclear research, and survived until 1974.

According to Herbert Fröhlich’s biographer, G. J. Hyland, another member of the ‘Jazz Band’, Dmitri Ivanenko, had been arrested on February 27, 1935, in the wake of the Kirov assassination. (Kirov was head of the Party organisation in Leningrad, and was assassinated on December 1, 1934. Some accounts suggest that Stalin had himself arranged the murder.) Shifman reports that Ivanenko and Landau had quarrelled in 1928, and Ivanenko had moved to Kharkov, but writes, however, that Ivanenko was not arrested until March 4, 1936. Whichever date is accurate, Ivanenko had then been exiled to a labour camp in Karaganda, but Vladimir Fock – another physics student whom Genia Kannegiesser/Peierls mentioned in a poem and in letters to Rudolf – managed to engineer an extraordinary intercession with Fröhlich before the latter escaped from the Soviet Union. Fröhlich was then able to gain further pressure from Pauli and Paul Dirac, and Ivanenko‘s sentence was commuted to exile in Tomsk.

Most poignant of all was the fate of Matvei Bronstein, another of the ‘Jazz Band’ alongside Landau, Gamow and Genia Peierls. He was arrested on the night of August 6, 1937, when aged thirty. According to the archives, his captors demanded that he hand over his arms and poisons, to which Bronstein responded with a laugh. He was sentenced and executed, on the same day, in a Leningrad prison in February the following year. It is not surprising that Lev Landau spoke to Peierls in tones of terror when they met the month after Bronstein’s arrest. Landau, a future Nobelist, was himself arrested on April 27, 1938, for comparing Stalinism to Nazism.

A report in Ukrainian Week from June 2019 (Landau worked in Kharkov) reinforces the fact that Landau and his circle had been under pressure for a while. It reports: “Already in 1936, the NKVD had begun to build a case against ‘a group of counterrevolutionary physicists at UPTI led by Professor Landau.’ The police interrogated Lev Rosenkevich, who was then the head of the radioactive measurement lab at the Institute. During this interrogation, Rosenkevich supposedly confessed that back in 1930 Landau’s ‘counterrevolutionary group’ had already been active at UPTI, and included Shubnikov and the head of the x-ray laboratory, Vadim Gorsky. The NKVD acted swiftly and in November 1937, Shubnikov, Gorsky, Rosenkevich and nuclear physicist Valentin Fomin were shot.” Thus we have further evidence of the horrors that Landau must have confided to Peierls in their furtive meetings of September 1937.

Another study might draw some interesting comparisons between those Germans persecuted in the Soviet Union and those like Charlotte Houtermans who were able to engineer a miraculous flight from the terror. Herbert Fröhlich was another who reputedly managed to ‘escape’. Fröhlich had been invited to work at the Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute in Leningrad by Yakov Frenkel, the same scientist who had invited Peierls to the Odessa Conference in 1930, and he thus left the University of Freiburg in 1933 for his new life. He in fact sought employment in the United Kingdom first, but failing to be awarded any funding, accepted Frenkel’s offer, waited six months to pick up a visa in Paris, and arrived in the Soviet Union only in the late summer of 1934. Thereafter, Frohlich’s account becomes increasingly dubious, however.

Fröhlich blamed his disillusionment on the assassination of Kirov in December 1934, and the ‘Great Terror’ that followed. Yet that was a premature assessment: the Great Terror is not generally recognized as starting until 1936, and foreign scientists were not persecuted at that time. Fröhlich, through another miraculous series of events that almost matched George Gamow’s picaresque adventures (see ‘Mann Overboard’), including a fortuitous exit visa planted in his passport, and his ability to buy a sleeper ticket on a train to Vienna with rubles without the NKVD’s noticing, managed to escape to Austria in May 1935. (Fröhlich’s ODNB entry states that he was ‘expelled’ from the Soviet Union. If Moscow wanted to punish him, it would surely have handed him over to Germany.)

What is also significant, as Christopher Laucht informs us in Elemental Germans, using part of the Peierls correspondence not published by Sabine Lee, is that Peierls was also involved in helping Fröhlich’s egress. With whom he communicated, and what exactly he achieved, are not clear, but any lengthy exchange with the Soviet authorities does not match with the more frenzied activity by which Fröhlich described the events. In any case, the community of German leftist émigré scientists in England no doubt took notice of his adventures. In England, Fröhlich took a position under Nevill Mott in Bristol, alongside Klaus Fuchs, and eventually became Professor of Theoretical Physics at Liverpool University. Even more astonishing is the fact that Fröhlich, despite all his tribulations with his Soviet hosts, apparently seriously considered an invitation by Frenkel to return to Russia soon afterwards. Even his biographer was moved to note: “Why he should ever have entertained this course of action is not at all clear, given his earlier experience there, and the fact that Stalin was still conducting his Great Purge.” The naivety of émigré Germans scientists was matched only by the clumsiness of the NKVD.

Thus Peierls’s decision to visit Moscow in the late summer of 1937 seems incredibly rash, unless he had some kind of relationship with the Soviet authorities. He was not yet a citizen of the United Kingdom, while his wife was in England with two children: he owned a German passport. It would be unlikely that the Germans would come to his rescue should he encounter any difficulties. He must have gained a clear understanding of the horrific goings-on in the Soviet Union. He admitted that Landau furtively explained to him the general oppressions of the Terror, but did not explain how Landau and his associates themselves were being persecuted at that time. A subtle point that has been overlooked, moreover, is this: if Landau was under intense investigation at the time, why did the authorities allow him to travel from Kharkov to Moscow for the conference, to meet a ‘Gestapo spy’? The NKVD surely intended him to speak to Peierls, and reinforce the fear that he should hold for the Soviet secret police. He might well have impressed upon his friend that, unless Peierls continued to co-operate, his (Landau’s) life would be in danger. Otherwise, exactly what the benefits of attending such a conference would have been were extremely murky, as the following section makes clear.

Conference Proceedings

For someone who recalled so many events so crisply, Peierls was remarkably vague about Moscow in 1937. In an interview conducted by Charles Weiner of the University of Seattle in 1969, Peierls said: “I don’t remember much in detail about the conference. It was a time when work on cyclotrons in Russia had started. People were reporting on the progress. I don’t think they had a working cyclotron yet . . . “, adding later: “There was a conference in Moscow and when already the chance of foreigners to go there was already deteriorating, when the mass arrest had started. This was heading for Stalinism.” Apart from the outrageous misrepresentation about the nature of Stalinism, and how long Stalin’s murderous policies had already been in evidence, Peierls here completely finesses the point of why he had gone to Moscow. Given the poisonous atmosphere of the mid-1930s, might he perhaps have verified how useful such a gathering would be before agreeing to attend? And would he not have been required to submit a report on the proceedings his return? Yet he struggled to recall what the conference was about: “I think it was nuclear physics”. He recalls Bohr’s having been in Moscow in the summer, but mistakenly described George Gamow as being present that September, and had to be corrected by Weiner (who appears to be confused about the ‘conference’ at which Borg spoke in June, and the September event). Weiner was overall a very incisive interrogator, and had done his homework, but he missed an opportunity here.

The atmosphere in Moscow in 1937 must surely have been memorable, apart from what appears to have been a very meaty set of presentations. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists provides the following details about the agenda: “Twenty-three of the 28 papers were by Soviet authors, and they covered five main problems: the penetration of matter by fast electrons and gamma rays; cosmic rays; beta decay; the interaction of the nucleus with neutrons; and the theory of nuclear structure. There were also discussions of high-voltage apparatuses used for penetrating the nucleus.” The chairman of the conference was Abram Ioffe, who also chaired the conference in Odessa in 1930. He must have had special significance for Peierls, since his daughter, Valentina, was one of the ‘Jazz Band’ group of which Genia, Landau and Gamow were members. In view of Ioffe’s position, one might wonder whether information about the not totally reliable group filtered back to Ioffe himself. Landau was arrested soon after the conference, and I have already described what happened to Ivanenko and Bronstein.

A report on Ioffe’s address to the conference (from the Bulletin of Atomic Sciences) is worth quoting in full:

“Ioffe’s opening speech at the second conference reflected the forces at work under Stalin in the late 1930s and indicated that the field of physics was not immune to the political currents of the day. He spoke about the tremendous achievements of Soviet science, which under socialism was devoid of the slavery and exploitation of capitalist science. He described how advances in nuclear physics served to verify the validity of dialectical materialism. Ioffe praised the emergence of proletarian scientists who replaced the old intelligentsia and highlighted the great strides made since 1933: the creation of a large network of physics research institutes, and the fact that in four years the number of nuclear physicists in the Soviet Union had quadrupled to more than one hundred.

On a more somber note. Ioffe acknowledged the failure of Soviet physicists as yet to achieve ‘any kind of practical applications’. And while the Academy of Sciences Presidium, in the protocol issued at the end of the conference, touted the achievements of Soviet nuclear physics as outlined by Ioffe, it also drew attention to the failure to begin construction of a new, powerful cyclotron.”

Peierls obviously found this unremarkable, not noting the irony of the fact that Soviet scientists were being persecuted and murdered, while ‘capitalist science’ was reportedly riddled with ‘slavery and exploitation’. Nor did he comment on the final communiqué issued by the attendees to the person who inspired the whole affair. According to the archive, “On September 1937 at the Second All-Union Conference on nuclear physics in Moscow, the participants addressed Comrade Stalin with these passionate words of admiration: ‘The successful development of Soviet physics occurs against the background of a general decline of science in capitalist countries, where science is falsified and is placed at the service of greater exploitation of man by man. . . Vile agents of fascism, Trotsky-Bukharinist spies and saboteurs . . . . do not stop short of any abomination to undermine the power of our country . . . Enemies penetrated among physicists, carrying out espionage and sabotage assignment sin our research institutes . . . Along with all the working people of our socialist motherland, Soviet physicists more closely unite around the Communist party and Soviet government, around our great leader Comrade Stalin . . .’”

Either Peierls did not hang around to hear this nonsense, or listened, and concluded it was not worth recording for posterity when he returned to the United Kingdom. I repeat his only technical conclusion: “Nevertheless, the scientific discussions at the conference itself were normal and fruitful”, as if it had been just another conference, like one in Brussels, or Bath, perhaps. Why did this experience not solidify his resolve against the dark forces of Communism? On the other hand, his colleague David Shoenberg at the Mond Laboratory, with whom he worked on a paper on magnetic curves in superconductors in 1936, returned from Moscow in late September 1938, and told everyone about Landau’s arrest and incarceration. Shifman rather oddly suggests that Fuchs should have spoken to Shoenberg to learn the truth of Stalin’s oppression: but his mentor Peierls would have been just as capable, and much more conveniently placed.

Peierls, unlike Kapitsa, never petitioned Soviet authorities (except in a plea to Khrushchev for the emigration of Genia’s sister, Nina), never expressed or published any criticism of the murder and imprisonment of Soviet physicists under Stalin, including many eminent physicists and colleagues he had met at conferences in the Soviet Union. Nor did he support Soviet physicists who were active in the dissident movement, notably Yuri Orlov or Andrei Sakharov. His most fervent defense was for identified Soviet agents, such as Fuchs, and for suspected Soviet agents, such as Oppenheimer, and in his tortuous appeal on behalf of the convicted spy Nunn May.

The Meeting with Nina

The likelihood of Peierls’s being able to set up a safe meeting with his sister-in-law, Nina, in Leningrad at that time must have been extremely slim. Again, Peierls is terse about the occasion. From Bird of Passage: “I then went . . . to Leningrad, where I met Genia’s sister, Nina, who had by then been allowed to return to Leningrad. From there I went to Moscow.” No description of how he had managed to locate her, or what they discussed. Yet it would have been exceedingly dangerous for Nina to make contact with any foreigner. As Timothy Snyder has written in Stalin and Europe: Imitation and Domination, 1928-1953: “Well aware of the threat of total espionage from abroad, Stalin had by the 1930s created a system of ‘total counterespionage’ in the Soviet Union: ubiquitous surveillance and terror. Every contact with foreigners was watched. Every visitor to foreign consulates was investigated. Every immigrant was suspected as a possible foreign agent.”

Nina had been allowed to return from exile, of course. In March, 1935, she and her parents had been exiled to Ufa for five years, but, at the end of April, 1936, she had been allowed to return to Leningrad. Nina described this fortuitous event in these terms: “The slogan ‘Children are not answerable for their parents’ which Stalin suddenly produced at the start of 1936 immediately granted freedom to all young people who had been exiled from Leningrad as ‘members of the family’, and I was one of these. At the end of April I returned to Leningrad.” This fact is confirmed by a letter that her parents were able to send to Genia on May 9, 1936, when her mother writes that she knows only that Nina has gone to Leningrad. (The truth that Nina’s parents were as innocent as she was is irrelevant in this picture.) For some reason, however, Nina makes no mention of any meeting with Peierls in her memoir about her step-father, which was published posthumously in 1991. And maybe they did not meet in in Leningrad: Shifman writes elsewhere (p 13) that Nina, after her exile to Kazakhstan ‘returned to Leningrad after Stalin’s death’. Someone has the facts wrong.

What is more likely is that the whole encounter had been engineered by Stalin, to communicate to Peierls that his wife’s relatives were suffering, but that their situation could be eased by Peierls’s continued contribution to the Soviet acquisition of western atomic research. After all, it was no use threatening persons with the uncertain fate of their relatives unless you were able to confirm to your victim that they were still alive, but in permanent danger, and that others like them had been exterminated. And Isai’s fate would remain on a roller-coaster. Nina herself describes how autumn 1937 saw the start of arrests among people exiled from Leningrad, and that Isai was arrested in March 1938, and spent eight months in an overcrowded prison cell in Ufa. She remarks, about Isai: “He was interrogated twice: a repeat interrogation about the murder of Uritsky which had happened 20 years before, and on the ‘spying activities’ of Rudolf Peierls, who by that time already a physicist of world renown.” He was not physically assaulted, but subject to all manner of threats, as well as ‘screaming and foul language’.

We thus see the duplicity of the NKVD’s operation. On the one hand, it threatened an innocent man purely because of a distant (and non-blood) relationship with a known assassin, and sought to acquire knowledge from him of a German scientist’s supposed espionage simply because he (Isai) and his wife had been visited in 1934 by his step-daughter and husband, showing off their baby daughter. At the same time, they allowed this German spy to enter the country, unchallenged and unarrested, and permitted him to conduct a clandestine encounter with the prisoner’s other step-daughter, who had recently been released early from a term of exile, and converse with a suspected rebel (Landau), who was under close investigation. The contrast between the fate of other Germans, and Peierls’s relatively serene sojourn, and his ability to meet Nina unharassed, could not be more stark or provocative.

As a final twist in this saga of distorted memories and deliberate disinformation, I present the enigma of the text of a letter sent by Nina to Genia in May 1936, just before she returned to Leningrad, where she commented on the photographs of the Peierlses’ daughter. “Thank you for the pictures of Gaby”, she wrote. “We also received the Berlin pictures. Gaby there is a bit worse seen, but your Shweiger [father-in-law] is amazingly clear-cut; he has the face of an actor and resembles Isai. . . . Rudi looks best of all from the viewpoint of expressiveness.” Did Nina get the date or location wrong? Peierls never mentioned in Bird of Passage a visit to see his father in Germany after his own escape in 1933. He indicates that the next time he saw his father (and his step-mother, Else, his own mother having died in 1921) was in 1939, when they were allowed to emigrate, and stopped off in the UK on their way to the USA. Yet that is also untrue, as the letters from his father and his step-mother indicate very clearly that they visited Rudolf and Genia in England in June 1936, i.e. after Nina’s letter was sent. Heinrich Peierls also refers to meeting Genia and Gaby early in 1934, in Hamburg, so Nina could not have been referring to photographs taken on that occasion.

What was Peierls doing back in Germany in 1935 or 1936, and why would he conceal the fact in his memoir? His published Letters also show that he and Genia made a visit to the Soviet Union in 1936, which again he ignores in his autobiography. In a letter to L. I. Volodarskaya of 27 September, 1989 (printed in Volume 2 of Lee’s edition of his correspondence), he tells his addressee that he and Genia visited the Soviet Union ‘a few more times in the early thirties’. Yet he completely overlooks these events in his memoir. In a letter to H. Montgomery-Hyde of March 35, 1981, in Captain Renault style, he rebuked the author over his book The Atom Bomb Spies, writing; “I must say I am quite shocked by many inaccuracies and the general careless attitude to the facts which it reveals.” But Peierls is no better. How can one trust anything he says?

* * * * * * * * * * *

According to all accounts by friends and colleagues Rudolf Peierls was a decent man, an integrated, pipe-smoking, crossword-solving English gentleman, feted, honoured and respected. Even if the meeting with his future wife had been arranged, theirs was clearly a love-match, and Rudolf was an attentive husband and a doting father. He was a brilliant scientist, and an excellent teacher who inspired hundreds of students. As the awards tumbled over him in the last couple of decades of his life, he surely basked in the reputation he had gained among scientists world-wide, and with the British intellectual elite.

Yet the great secret must have haunted him – to the degree that he could never even hint at it in his autobiography. Apart from his confession to Viscount Portal, he could never admit to the world that his wife’s kinship with a mortal enemy of the Bolshevik regime had placed intolerable burdens on them both. For there is surely another narrative that has to be pieced together: the flight from Germany; the fortuitous acceptance of a post at Cambridge using funds released by Kapitza’s forced detention in the Soviet Union; the unexpected invitation by Frenkel to attend a conference in Odessa; the introduction to Genia by another manipulated deceiver, George Gamow; the struggle to gain a visa for Genia, and then their miraculous departure to the West; their unexplained and unreported return visit to Moscow in 1932, when Peierls laboured to gain a re-entry visa for Genia; the assistance given to Fröhlich to ‘escape’ from the Soviet Union in 1934; the unlikely direct correspondence with exiled ‘criminals’ in 1936; the concealed visit to the Soviet Union in 1936; the unnecessary and dangerous attendance at the conference in Moscow in 1937, and the problematic private encounter with Landau; the perilous meeting with Nina in Leningrad that same year; the evasive explanation for that visit given to immigration officers in 1938; the adoption of British citizenship to allow him to work on the MAUD project; the timely awareness that Klaus Fuchs would be a useful asset on the project, and the promotion of his employment; his nurturing of Fuchs despite the knowledge of his Communist past; Peierls’s continued friendships with open Communists such as Roy Pascal; his recruitment of Gerry Brown, an open subversive communist from the USA, to a post at Birmingham soon after Fuchs’s conviction; and his contribution to the Manhattan project followed by his immediate support of peace movements that were instruments of Stalin’s aggressive objectives.

It is very difficult for those of us who have never suffered under a totalitarian regime such as Hitler’s or Stalin’s to judge the actions of those who were subject to the kind of threats that the Peierlses, Gamow, and others underwent. The date on which Genia and Rudolf sold their souls to the Devil will probably never be verifiable, but when it happened, they must have quickly realised that they were being sucked into a vortex that was inescapable. And yet . . . Need Rudolf have been quite so diligent and dedicated in fulfilling Stalin’s wishes? Was he in fact specifically instructed to recruit Klaus Fuchs? Since his authority was at that stage minimal, could he have not found a way to exclude him from the project without damaging his own credibility, and thus possibly causing harm to Genia’s relatives? Did he and Genia not conclude that Stalin’s cruelty was capricious and random, in any case? Did he have to take so naively such an active role to promote the Atomic Scientists’ Association, since it had enough steam and authority to communicate its message without him?