[A warning: the narrative in this bulletin is quite complicated. So many competing accounts of the events leading up to Kim Philby’s recruitment by the Soviets trip over each other: untangling them is a challenge. I have no wish to oversimplify the story, and I consider it imperative that I leave as full an analysis as possible for posterity.]

Contents:

Introduction

Sources and Method

Edith’s Movements

Acquaintances in Vienna

Recruitment

Kim’s Recruitment

Interim Conclusions

Jungk’s Quest

Russian Archives

The Legendary Edith

* * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

I use ‘legend’ here not in the Westian sense of ‘someone who was occasionally famous or notorious’, but as a way of suggesting that the familiar story of the role of Edith Tudor-Hart as a queenpin in Soviet espionage is largely mythical. Of course, in intelligence lore the word has a secondary meaning. The ‘legend’, a false biography created by the OGPU/NKVD and GRU for agents (primary ‘illegals’, not necessarily using false identities, but without diplomatic cover) in foreign countries was an important part of the deception process, and the Russian Intelligence Service (RIS) generally created false stories in order to confuse the enemy – and, perhaps unwittingly, its own successor officers.

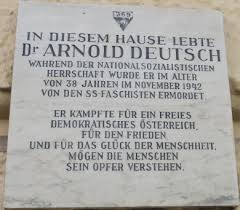

In this bulletin I inspect the assertion that Edith Tudor-Hart was the vital agent responsible for the recruitment of the Cambridge Five – one notably made by Anthony Blunt, who, under interrogation, described her as ‘the grandmother of us all’, despite the fact that Edith was born a year after him. (I would encourage readers to turn back to the June coldspur, at https://coldspur.com/summer-2024-round-up/ for my prologue to this investigation.) The dominant event in this scenario was the reputed recommendation by Edith to Arnold Deutsch, in May 1934, that he, on behalf of Soviet intelligence, recruit Kim Philby. Edith declared that Kim’s potential and reliability could be assured because of her close friendship with Litzi, Philby’s new wife, who could presumably be trusted to have made an ideologically proper marital alliance. This proposal resulted – according to the infamous narrative supplied by Philby himself – in Kim’s meeting the anonymous Deutsch for the first time on a bench in Regent’s Park. Deutsch was impressed, and the ominous relationship and expansion of the group of penetration agents, began. But can this story be trusted?

I believe that it is best tested through the analysis of the behaviour of the four main actors (Kim and Litzi, Edith and Arnold) in two critical periods, namely in the summer and early autumn of 1933 in Vienna, and in London in May and early June of 1934. Some of the questions that strike me as important are: Did Arnold know Kim from those days in Vienna, or was Kim a stranger to him in Regent’s Park? Did Edith really have an opportunity to meet Kim after her rapid marriage to Alexander Tudor-Hart in August 1933 and before her departure for England a few weeks later? Had Kim already been recruited by Soviet Intelligence when he was in Vienna? What was Litzi’s standing as an agent before she left for England with Kim in the spring of 1934? Which aspects of Kim’s account of the events of that summer are verifiable? I refresh my previous research on this matter with an analysis of Edith’s files at the National Archives (released in 2015), a closer inspection of important works that appeared in the 1990s, as well as a study of other books published in English, German and Russian during the past couple of decades.

Sources and Method

I covered some of the anomalies and contradictions in the tales of Kim’s recruitment in Misdefending the Realm, but only skimmed the surface of the puzzle, since my intention then had been solely to point out the chaotic nature of the accounts of subversive activity in the 1930s, and the danger of relying on the memoirs of untrustworthy persons as a guide to the facts. At that time I barely touched on the role of Edith Tudor-Hart. For those readers who do not have a copy of my book close at hand, I here reproduce the relevant section (pp 37-39):

“One of Philby’s main assertions is that he was recruited by Arnold Deutsch, known as Otto, on his return from Vienna with his new bride, Litzi Friedmann, in the summer of 1934, and only then committed himself to supporting the communist cause. That story has been distorted and misrepresented repeatedly over the years, as the following analysis shows:

- In My Silent War (1968), Philby elides over his recruitment, merely stating that when he left Cambridge in the summer of 1933, he was convinced his life would be dedicated to Communism. [i]

- In Deadly Illusions, Costello and Tsarev claim that Alexander Orlov supervised and was ultimately responsible for directing Philby as agent. Because of Soviet attempts to get Orlov back (who had defected and made a deal with Stalin), Philby was not permitted by the KGB to even hint at how he was recruited.) [ii]

- In The Third Man (1968), Cookridge says that Philby did not return to London until the end of summer, 1934, where he was recruited by Simon Kremer at the Soviet Embassy. [iii]

- In The Philby Conspiracy (1968), Page, Leitch and Knightley (who interviewed Philby’s children in Moscow), reported that Philby told his offspring that ‘I was recruited in 1933, given the job of penetrating British intelligence, and told it did not matter how long I took to do the job.’ [iv]

- In Philby: The Long Road to Moscow (1973), Seale and McConville report an earlier return to London, in early April, but that Philby was not recruited for some months, and still only on probation, the first steps being ‘directed by intelligence officer on the staff of the Soviet Embassy’. [v]

- In The Fourth Man (1979), Andrew Boyle indicates that Philby was already a novice agent on probation when he went to Vienna in September 1933. [vi]

- In The British Connection, (1979), Richard Deacon suggests that Deutsch probably recruited Philby when the latter was visiting Vienna. [vii] [This actually makes the most sense, as will be explored later.]

- In The Master Spy (1988), Phillip Knightley introduces the idea of the obvious lie: ‘Litzi said that KP took no part in Communist activities in Vienna – a cover story that KP confirmed to Knightley that they had planned she would say.’ He adds that the Philbys did not leave Vienna until May 1934, and stopped off in Paris on their way back to London. When he interviewed Philby in Moscow, he was told: ‘My work in Vienna must have caught the attention of the people who are now my colleagues in Moscow because almost immediately on my return to Britain I was approached by a man who asked me if I would like to join the Russian intelligence service. For operational reasons I don’t propose to name this man, but I can say that he was not a Russian although he was working for the Russians.’ [viii]

- John Costello, in Mask of Treachery (1988) observes that Philby’s expressed intention to sit Civil Service exams (as he told his tutor at Cambridge) reflects Soviet determination to press moles into government, adding ‘That Philby would even consider a Whitehall career after deciding to become a Communist agent suggests that he too had come under cultivation by the Soviets before he left Cambridge.’ [ix]

- Deadly Illusions (1993), by John Costello and Oleg Tsarev, gives the impression that Soviet Intelligence had successfully stirred the pot. Litzi is reported as not receiving her passport until late April, and the Philbys set off for Paris via Germany. ‘That Philby had approached the CPGB before his first meeting with Reif is itself confirmation that he had not, as previously believed, been recruited in Vienna. This is corroborated by NKVD archival records, and by KPO’s 239-page deposition.’ The authors add that, in the spring of 1934, Philby went to CPGB HQ, to renew [sic] links with the CP before he was approached by Reif, but received a frosty reception at CPGB headquarters. Litzi Philby invited her friend, Edith Tudor Hart to tea, and Edith was impressed by Philby, and thus reported his candidacy to Deutsch, who consulted with Reif. Reif approved Philby’s recruitment in June 1934. ‘My decision to go to Austria was taken before I had decided to join the Communist movement,’ Philby is quoted as saying. [x] But Costello and Tsarev are far too trusting of the reliability of Philby’s memoir, and they attribute to ‘faulty memory’ many of the contradictions between Moscow’s and Philby’s account that occur in their flawed narrative.

- Treason in the Blood (1994), by Anthony Cave-Brown, has the couple leaving Vienna on May 2, and spending a holiday in Paris before arriving in London in mid-May. Philby celebrated June 1 as the day he was approached by Deutsch. [xi]

- The chronology shifts in The Philby Files (1994) by Genrikh Borovik. Philby decides to continue Party work with Litzi in England, and is back there in time to participate in the May Day parade in London. Again, Philby seeks out contacts at the Soviet Embassy, but this time a man [i.e not Edith Tudor Hart] he met in Austria sought him out, to introduce him to Deutsch. Philby considered ‘it very lucky this chance happening occurred’. [xii]

- Yuri Modin (the handler of the ‘Cambridge Five’ after the war), admits, in My Five Cambridge Friends (1994) to all the confusion, but clarifies it all for us by saying that the NKVD was not involved, and that, ‘from 1934 to 1940, the Soviet secret service was the last thing on their minds. What he means, of course, it was the innocent Comintern that was involved: he confirms the meetings with Deutsch, but claims it was another unknown NKVD officer [sic] who directed his work. [xiii]

- The Crown Jewels (1998), by Nigel West and Oleg Tsarev, has some interesting things to say about Deutsch, but merely repeats the June 1934 recruitment. [xiv]

- In A Time For Spies (1999), William E. Duff follows the Costello/Tsarev account, but points out the contradictions between Costello and Tsarev, indicates that Costello gives too much credit to Orlov, and observes that Tsarev’s original source material has not been examined. [xv]

- The Mitrokhin Archive (1999) by Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin suggests that the Tudor Harts had been recruited by Deutsch in London, and given the codename STRELA. The authors cite Deadly Illusions as their main source for the recruitment of Philby. [xvi]

- Now the unpublished memoirs of Philby are revealed by his fourth wife, Rufina Philby, with Hayden Peake and Mikhail Lyubimov, in The Private Life of Kim Philby (2000). Here again, the Philbys are able to enjoy the May Day march in Camden Town, and then they are visited by a male friend, whom Philby had seen two or three times since returning from Vienna. This friend introduces Philby to Deutsch (i.e. there is no Edith Tudor Hart in this variation). [xvii]

- Almost a decade later, Christopher Andrew changes his tune, owing to the discovery of an ‘untitled memorandum in Security Service archives’. Thus the official history of MI5, Defending The Realm (2009), allows Andrew to reveal ‘the truth’ about Philby’s recruitment, deposited on the eve of his defecting to Moscow in 1963. “Lizzy came home one evening and told me that she had arranged for me to meet a ‘man of decisive importance. …. Otto spoke at great length, arguing that a person with my family background could do far more for Communism than the run-of-the-mill Party member or sympathizer.” [xviii]

[I have omitted listing the endnote references, as they caused havoc when I tried to copy them in. Please refer to my book for details.]

Nevertheless, I continued my narrative by pointing out that Deutsch himself (whom I shall hereafter simply refer to as ‘Arnold’), in the autobiography he provided to his bosses in Moscow in 1938, claimed that he had recruited STRELA and JOHN in Vienna before moving on to London, where he recruited Edith Tudor-Hart, whom he ‘had already known in Vienna’. Since the heading of the Tudor-Harts’ (i.e. Alexander’s and Edith’s) file at the National Archives confidently states – assuredly based on the evidence of Andrew and Mitrokhin – that STRELA was the cryptonym of the Tudor-Harts, I see a conflict. At least one person is mistaken. I also wrote at that time that, if Arnold had been familiar with John Lehmann and the Tudor-Harts in Vienna, he would surely have encountered Kim Philby there, and thus the story of the first meeting in Regent’s Park was probably inauthentic. That may have been a clumsy conclusion, because of the chronology, as I shall soon explain, but it may have been correct for other reasons.

Even a casual study of the source material copied from my book, above, leads to some serious scepticism and confusion over what happened when. For example, Cookridge places Kim’s return to England at the end of summer 1934. Borovik even gets the year of Kim’s return to Britain wrong. Page, Leitch and Knightley, and then Boyle, refer to Kim’s recruitment of some sort in Vienna, or even earlier, as do Deacon and Pincher. Costello and Tsarev place considerable strains on the chronology by recording Kim’s and Litzi’s passage through Europe, thus requiring a number of events to occur before the park-bench meeting on June 1, a troubling time-line echoed by Cave Brown, who implied that he had inspected the police form in Vienna that gave their date of egress and their destination. Reinforcing Arnold’s claims, Andrew and Mitrokhin apply tight constraints by indicating that Edith was not recruited until Arnold came to London, which would tend to cast doubts on the experience and reputation she was claimed to own when she picked out Kim as a prospect. If, as Cave Brown asserted (and, incidentally, as Andrew and Mitrokhin repeated), Kim and Litzi left Vienna on May 2, they would have struggled to witness the May Day celebrations in Camden Town on May 1, an experience that Borovik, Parker and Lyubimov felt fit to record. As my re-inspection of A Time of Spies reveals, Duff even claims that the newlyweds left Vienna in March for Paris, ‘where they remained for more than a month before Kim brought his new bride in May of that year’. And so forth. My goal now is to unravel these – and other – contradictions and paradoxes.

My primary sources are, in chronological order:

- Deadly Illusions, by John Costello and Oleg Tsarev (1993). This is the first account that claims access to KGB archival material, and has been the most influential. Yet it should be remembered that this work was provoked by a desire by the FSB (the Федеральная Служба Безопасности, or Federal Security Service, the successor to the KGB for internal security matters, created in 1995) to put a more positive spin on the KGB’s achievements after the disclosures that Gordievsky provided, and that Tsarev’s access may have been carefully controlled – perhaps by the Russian equivalent of a ‘Foreign Office Adviser’. Later in this report I shall examine in detail the authenticity of the sources on which the book relies.

- The Philby Files, by Genrikh Borovik (1994). This account relies heavily on what Kim told Borovik, and is not enhanced by Borovik’s lack of method, and his rather shaky understanding of intelligence and counter-intelligence matters.

- Treason in the Blood, by Anthony Cave Brown (1994). Cave Brown’s book tends towards encyclopædism, and his management of dates is disorderly. He has a few fresh insights.

- The Crown Jewels, by Nigel West and Oleg Tsarev (1998), which applied some further spin, through Tsarev, based on access to KGB files, but also included some erratic observations. It suffers from the same dubious provenance as Deadly Illusions.

- The Private Life of Kim Philby, by Rufina Philby, with Hayden Peake and Mikhail Lyubimov (1999), which contains two missing chapters from Kim’s autobiography (but not the postulated one that would describe his time in Vienna).

- The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, by Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (1999), based on the transcriptions taken out of Russia by Mitrokhin.

- Ein Kapitel aus meinem Leben [‘A Chapter from my Life’], by Barbara Honigmann, the daughter of Litzi and Georg Honigmann (2004).

- The Young Kim Philby by Edward Harrison (2012), which contains some very shrewd insights but accepts many familiar narratives unquestioningly.

- The Lawn Road Flats by David Burke (2014), a rather discursive work that presents some revealing research – especially on Edith.

- Stalin’s Agent: The Life and Death of Alexander Orlov, by Boris Volodarsky (2015), a somewhat chaotic compilation by the ex-GRU officer, which nevertheless contains many useful nuggets.

- The Tudor-Hart files, released to the National Archives in 2015 (KV 2/1012-1014; KV 2/1603-1604; KV 2/4091-4092).

- Die Dunkelkammern der Edith Tudor-Hart [‘The Darkrooms of Edith Tudor-Hart’], by Peter Stefan Jungk (2017). Edith’s relative (second cousin once removed) had access to a wide and fascinating range of family letters and memories, but his account relies almost exclusively on works already mentioned for his analysis of Edith’s career in intelligence and espionage.

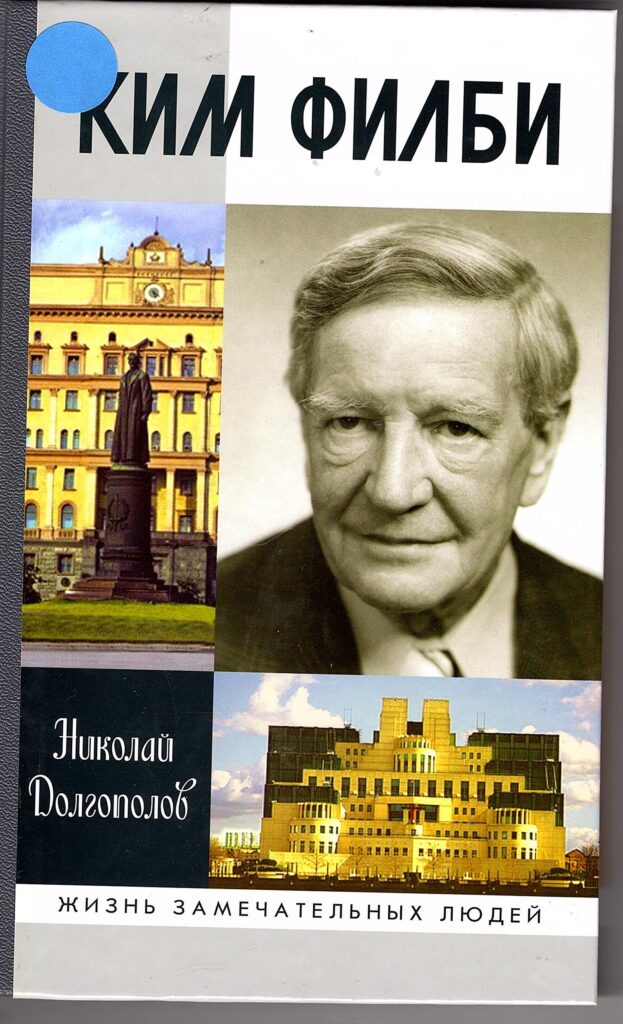

- Ким Филби by Николай Долгополов [‘Kim Philby’, by Nikolai Dolgopolov] (2018). Dolgopolov presents some fresh archival material from the Lubyanka.

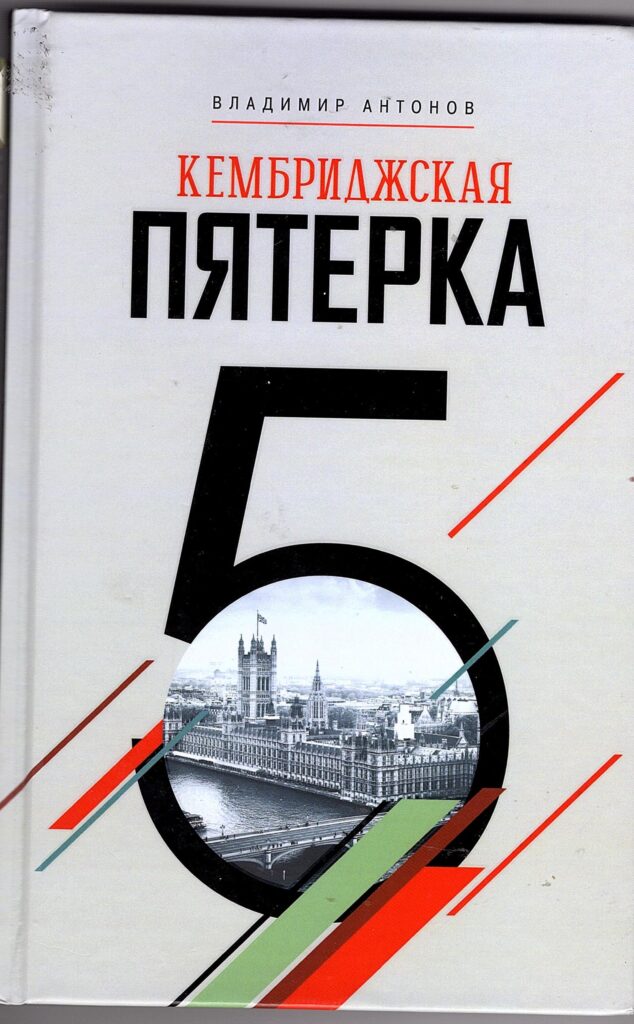

- Кембриджская Пятерка by Владимир Антонов [‘The Cambridge Five’, by Vladimir Antonov] (2022). A slightly different perspective on the careers of the Cambridge Five.

The method I decided to deploy is to address the primary questions by starting with the key assertions made in Deadly Illusions, and to test and compare them with statements made elsewhere.

Edith’s Movements

What were Edith’s exact movements? According to Deadly Illusions: “Edith. . . . arrived in London after escaping prosecution for her illegal Party activities. Like her friend Litzi Friedman, she had sought refuge by marrying an English medical doctor named Alex Tudor Hart [sic], who sympathized with the Comintern. . . . Her file discloses that she had been active in the Communist underground in Vienna in 1929 and served as one of the trusted ‘cultivation officers’ of the London ‘illegal’ rezidentura. Her job was to spot sympathizers who were potential candidates for recruitment, like Philby. Although short-sighted, which led to her being criticized for not being careful enough, she established a reputation as a very loyal and resourceful comrade who carried out important assignments for Moscow.” The authors add, in Endnote 47: “Precisely when Edith Tudor Hart arrived in Britain is not clear from her NKVD file, but it was 1933 and almost certainly May, the year before Philby set out for Austria.”

This is a complete mess. It strongly suggests that Edith first crossed Britain’s shores only in 1933, when her MI5 file shows that she had resided there on multiple occasions in the 1920s until she was expelled early in 1931. The month of May is ridiculous: that was the month in which she was arrested. It implies that Edith imitated the matrimonial plan of her friend by marrying an Englishman, when she had in fact married Alexander on August 16, 1933, before Kim had first set foot in Austria. Her MI5 file (which is curiously very silent about the movements of Alex and Edith in 1933) indicates, in a Special Branch Report to MI5, that the marriage took place at the Embassy in Vienna, and that the couple left for England a few weeks later. Kim did not set out for Austria in 1934: he arrived in the autumn of 1933, and left the country with his new bride in April (or May) of 1934. The gap between 1929, when Edith had reputedly been active in the Communist underground, and her stated role as a ‘cultivation officer’ is ludicrous. (The suggestion that Edith was only one of many such ‘cultivation officers’ raises the question of who the others were, and why they have not been celebrated.) Edith had been imprisoned in Vienna in the early summer of 1933 for suspicious activity, having been expelled from the UK two-and-a-half years earlier. The idea that she might in 1933 have been a talent-spotter, and the suggestion that she might even have chosen Kim as a potential agent at that time, are palpably absurd. Costello and Tsarev cite the KGB TUDOR HART file, No 8230 Vol. 1, for this, including a profile of her supplied by Arnold, but much of it must be the work of a vivid imagination.

Tsarev and Costello must have been fed this information, since they provide no source documents for her admitted activity in Vienna in 1929. Similarly, the claims about ‘a very loyal and resourceful comrade’ carrying out important assignments lacks documentary support. In fact, the only document cited (the profile by Arnold, in Endnote 47) draws attention to her deficiencies in general, especially her carelessness, although it does not describe the famous occasion in 1937 when she temporarily lost an address book with the names of comrades in it. That would not have endeared her to Moscow Centre. In KGB, Andrew and Gordievsky state that she was used mainly as a courier, and it would appear that the claim about ‘important assignments’ was an exaggeration.

What is astonishing is the lack of surveillance reports by British counter-intelligence on Alex and Edith during this period. Between an MI6 report from Vienna, dated July 8, 1931, which reveals that Edith is working for TASS (the Soviet news agency) and a note on April 23, 1935, indicating that she is running a photography business at Haverstock Hill, there is nothing apart from the Special Branch report of February 21, 1934, which covers Alex’s recent career, and records their marriage in Vienna in August 1933. What it does indicate, however, is that Dr. Tudor-Hart took up a position at St. Mary Abbott’s Hospital in Kensington in June 1933. Given the intense interest in the pair of them, the fact that no reports on their correspondence and movements (such as Edith’s presumed letter of appeal to him to come and rescue her, or his travel to Vienna, or their joint return as a married couple) were submitted to the file, both beforehand and afterwards, is a highly provocative phenomenon.

Yet evidence elsewhere confirms that MI5 was indeed intercepting correspondence at this time. A report from December 1, 1951, (in KV 2/1604) states that “Alexander paid another visit to Vienna to see Edith in early April 1931, Edith maintaining contact with him by letter until August 1933, when he returned to Vienna to marry her.” (An item in KV2/1603 indicates that Tudor-Hart left in August, but the exact date is obscured, as is the date appending a note indicating that he was a member of the Hampstead Anti-War Committee at some time in September.) Further: “Edith’s letters from this period show that there were certain legal complications and obstructions to her (Edith’s) marriage to TUDOR-HART at this time.” Why were these intercepts not filed?

These observations serve to contradict a later source – Jungk’s account of Edith’s tribulations. For some reason, Jungk has Alexander Tudor-Hart coming to Vienna in the spring of 1932, whereupon Edith moves in with him, although she ‘does not love him in the same way she loved Arnold’. Thus Alex is around at the time Edith is arrested, in May 1933, and is ‘shocked’, like all her friends, who include Litzi Friedmann, long separated from her husband. Yet Jungk’s tale then gets more absurd: he claims that Edith was released one month later, and that she then repaired to Litzi’s flat, where she met a new lodger who had been there a few days, namely Kim. Moreover, she is so taken with him that she confessed that ‘if she hadn’t been so tied to Alexander, she could have fallen in love with him’. The problem is that when such anecdotes so gravely break the rules of time and space, one has to wonder how much of the rest of the cavalcade of reminiscences is delusionary. (I emailed Mr. Jungk about these anomalies: he has not replied.)

I would judge that MI5’s record of Alex’s hospital service, and of his presence in England, is more accurate: the testimony of his son, Julian (also a doctor, the offspring of Tudor-Hart’s relationship with Alison Macbeth, b. 1927, d. 2018) confirms his father’s appointment at St. Mary Abbots Hospital. Yet the willingness of the British authorities to sanction the marriage between a suspected communist and a known agitator who had already been expelled from the United Kingdom, and to allow the solemnization of that ritual within the British Embassy in Vienna, suggests some possibly darker objectives at hand, and might explain why all records of the negotiations thereto – such as the letters identified above – have not appeared in the archive.

Acquaintances in Vienna

How well did Arnold, Edith, Litzi and Kim know each other in Vienna? Two passages from Deadly Illusions provide some background: “It was Edith Tudor Hart, who had also known Litzi Friedman in Vienna, who invited her old comrade to tea shortly after the Philbys had returned to London in May 1934. Litzi brought along her husband, since he was at a loose end while waiting impatiently to hear whether he would be accepted into the Communist Party. Over the teacups the couple gave vivid first-hand accounts of action on the Vienna barricades. Philby announced that the experience had made him more determined than ever to find some way of continuing to work for the Party in England, despite, as he told it, the off-hand way he had been treated at CPGB headquarters. Philby’s ardor and the cool manner with which the pipe-smoking young Englishman recounted his missions impressed Tudor Hart”; and “She [Edith] did not tell him at the time, but as an undercover Soviet agent she saw at once that Kim, rather than Litzi, could be turned into a valuable asset for the Soviet underground network to which she belonged.”

But where does this come from? No source is given. Edith had apparently only just been recruited. How would she know anything about the ‘Soviet underground network to which she belonged’? (Individual agents were supposed to be isolated.) If she had only just met Philby, how could she quickly form the judgment that he could be turned into a valuable asset? Was the utterly irrelevant, and hardly unusual, fact that he smoked a pipe a powerful indicator? One could interpret this passage in two ways: i) that Edith was indeed a deeply placed expert recruiter, with shrewd powers of observation, and that her legend was well-earned, or ii) that this was a clumsy item of invention passed on to Tsarev. Given Edith’s very recent return to the UK, and recruitment by Arnold, I would strongly favour the latter, reflecting an official policy of switching the attention from Litzi, who is explicitly presented here as being a strong candidate for espionage, to Edith. (The characterization of Kim has all the hallmarks of having been written by Philby himself.)

Moreover, this is another sloppily crafted excerpt. Previously, Litzi had been described as Edith’s ‘friend’. Now the authors state that she ‘had also known Litzi Friedmann in Vienna’. Well, of course she had. They were not strangers, striking up a friendship in London, since Edith had invited ‘her old comrade’ to tea. Comradeship signified a much closer bond than ‘acquaintance’ or even ‘friendship’. And what does that ‘also’ mean? In addition to Kim? Surely not, if Litzi introduced her husband to Edith. To Arnold? He is not featured in the preceding paragraphs. Certainly the impression given here is that Litzi and Edith had been active agitators in Vienna for quite a while, but that this was Edith’s first encounter with Kim. This flies in the face of what Jungk wrote about Edith’s being bowled over by him when she met him in Vienna. On the other hand, why meet at Edith’s residence? Given the previous surveillance of Edith, and her track-record of having to flee Vienna because of communist agitation, having Litzi and Kim visit her on her domestic territory was highly irregular, in violation of defined tradecraft, and potentially very dangerous. She knew she was under surveillance!

As for the relationship between Arnold and Edith, Deadly Illusions records (using Deutsch’s file 32826 in the Russian Intelligence Service Archive, RISA) that Arnold had known Edith since 1926, and that he had worked with her in the Vienna underground. What it does not report (if Jungk’s account can be trusted) is the torrid affair that they had had back in 1926, and that, when it was broken off by the discovery by Arnold’s fiancée, Josefina (Fini), of love-letters written by Edith to Arnold, the heartbroken Edith fled to England to become a kindergarten schoolteacher. It seems that Arnold thus dangerously lied in the curriculum vitae that he provided to the NKVD in December 1938 (which can be read in toto in The Crown Jewels, pp 104-107). Here he states that he married Fini in 1924, when she would have been sixteen or seventeen years old. Elsewhere in his bio, he wrote that he lived with his parents until he was 24, i.e. in 1927 – a dangerously contradictory disclosure! Other accounts indicate that they did not get married until 1929: Volodarsky even traced the marriage record to March 12, 1929, although he rather ingenuously remarked (p 691) that the statement cited in The Crown Jewels should be considered a ‘slip of memory’. Astute husbands (and wives) do not get wrong the date of their wedding a decade ago – let alone by five years – unless they have a goal of deception.

Arnold’s coyness about his marriage reflects a deep uneasiness concerning his relationship with Edith. His first affair with her (which he fails to mention in his c.v.) occurred while he was engaged, perhaps unofficially, to Fini. Thus Arnold’s statement that he recruited EDITH ‘whom I already knew in Vienna’, was delightfully vague. If he arrived in Vienna in October 1933 (as he claimed), the acquaintanceship to which he referred must have been between January 1931 (when Edith arrived after her expulsion) and January 1932 (when Arnold’s work for the Comintern had been discovered, and he was summoned to Moscow, where he was soon after appointed to the Foreign Department, OMS). He deftly elides over their relationship from the previous decade.

I shall investigate the questions about the recruitment of each to Soviet intelligence in the next section, but note here that Kim made an important observation in the testimony (‘memoir’) that he provided to the KGB in 1985. Costello and Tsarev write (p 135): “Philby, apparently through lapse of memory, alluded to his having met Tudor Hart in Vienna, which the NKVD reports show as another case of his memory being in conflict with the records.” But, of course, the records could not prove a non-event, namely that he had not met Edith in Vienna. All they could do is show that the file on Edith indicated that she claimed that the tea gathering was the occasion on which she had been introduced to Kim. But perhaps that assertion was untrue, since Kim’s testimony is confirmed by Jungk? Sadly, the National Archives reinforce the confusion through a vague and unverifiable statement that appears on the announcement of the release of the Tudor-Hart archive: “Edith was close friends with Litzi Friedmann, who would become Philby’s first wife, and MI5 believed it was through this connection that Philby came to know Tudor Hart [sic] in the early 1930s.” A couple of weeks in August-September 1933 is expanded to a number of years. And whoever wrote this discounts the evidence that Litzi introduced Kim to Edith in London, or else has overlooked it.

What is also astonishing is the translated text of the message that Ignaty Reif (MAR), the illegal rezident, sent to Moscow in June, announcing the positive meeting between Arnold and Kim, and identifying the potential new candidate for cultivation. It is a clumsy and muddled statement: “In future Philby will be called SYNOK [Russian for ‘SONNY’]. Through Edith, who is known to you, who had worked for some time under ZIGMUND in Vienna, we have established that the former Austrian Party member, who had been recommended to Edith by our former Party comrades, has arrived in Britain from Vienna, together with her husband, an Englishman. He is also known to Arnold. Edith has checked their credentials and has received recommendations from her Vienna friends. I have decided to recruit the fellow without delay – not for ‘the organization’, it is too early for that, but for antifascist work [emphasis added]. Together with Arnold and Edith, I worked out a plan to meet with SÖHNCHEN [German for ‘SONNY’] before SÖHNCHEN moved to his father’s flat. Arnold Deutsch’s meeting with SÖHNCHEN took place with all precautions. The result was his full readiness to work for us.”

I note that Costello and Tsarev state that this cryptogram was ‘undated’. That is not surprising, as it shows all the signs of having been faked. The flow is illogical. Reif introduces Philby and his cryptonym first, without explaining the background. Why, having stated that Philby will be called SYNOK, does Reif quickly switch to SÖHNCHEN ? He then suggests that ‘the former Austrian Party member’ (i.e. Litzi) had somehow been recommended to Edith (the implied Big Cheese of the operation) by our former Vienna comrades (why ‘former’?). Yet how had this recommendation been received, and why would it not have been considered by Reif first? Reif then mentions that the unnamed person’s husband is an Englishman, as if Moscow had no idea of what Kim and Litzi had been up to, and were ignorant of the circumstances of their marriage. Moreover, since Party comrades in Austria had already recommended Litzi to Edith, and Edith was prepared to recommend Kim on the basis of his being known by the reliable Litzi, why on earth did she need to check the credentials of both of them?

Furthermore, Kim ‘is also known to Arnold’. Why is Arnold not referred to by his cryptonym, ‘OTTO’? And what does that statement mean? That he has met him, and is acquainted with him? Why would Reif insert that if Arnold has supposedly just met Kim for the first time? Does it not sound as if Arnold had encountered Kim in Vienna? Or could it mean simply that his name is known to Arnold? But again, that makes no sense given the recent encounter between the two. Kim told Borovik that ‘a man he had known in Austria sought him out’, suggesting that Arnold had met Kim in Vienna, and had instigated the meeting. That would tend to undermine any leading role ascribed to Edith. In any case, Edith no longer needed to be protected by the time Philby gave his testimony to Borovik: she died in 1973. (One longs to see the original Russian.)

Tracking Arnold’s movements at this time is difficult. Some sources suggest that he was in Vienna in August 1933, and it was then that he recruited STRELA. At some time after that he moved to Paris, and was told that he would be sent to England for his next assignment. Yet Arnold’s own biography, reproduced in The Crown Jewels, tells a different story, indicating that he was informed in October 1933 that he was going to be assigned to work in Britain, at which time he moved from Paris to Vienna, where he recruited STRELA and JOHN. (I note here that Boris Volodarsky has confidently identified STRELA as Charlotte Moos, who was in England at the time.) If that is true, he would have arrived too late to recruit Alexander Tudor-Hart. Yet, since the MI5 file confirms that Tudor-Hart visited Edith in Vienna in April 1931, Arnold probably met him at that time, and could have recruited him then.

In any event, by the early part of 1934 Arnold had indeed moved to London, ahead of the Philbys. Costello and Tsarev, referring to Arnold’s bio in his KGB file, indicate that he arrived in February; Cave Brown states it was in April (but adds that his wife was with him then, which is wrong); Burke offers May. I referred earlier to my conclusion that Arnold probably met Kim in Vienna because of his acquaintance with Lehmann and the Tudor-Harts. If we trust Arnold’s timeline, the encounter with the latter now seems impossible, given Alex’s short visit to rescue Edith, but Arnold was clearly moving in those same circles after the Tudor-Harts left for Britain in early September 1933, and had ample opportunity to get to know Kim.

The same telegram is introduced in The Philby Files, however, and the paraphrase/transcription generates further confusion. Borovik is, however, a bit more precise about dates and formats, and offers some observations about the text itself. He annotates that ‘documents are presented with the original style intact. The only changes are to orthographic mistakes and typographical errors’. He states that telegram No. 2696 was sent by Reif to Moscow the day after the Regent’s Park meeting, briefly informing the NKVD, rather bizarrely, that ‘the son of an Anglo agent, advisor of Ibn-Saud, Philby, has been recruited’. Later, a long letter was sent to Moscow with the details, dated June 22 (incidentally sent via courier, probably Reif himself, to Copenhagen before routing).

I present the first few sentences of the text, so that a close comparison can be made: “Philby. From now on we will call him ‘Sonny’ or ‘Söhnchen’. Through ‘Edith’, whom you know and who worked at one time for Siegmund in Vienna, we established that an Austrian Party member with recommendations from Viennese comrades to ‘Edith’ arrived on the island with her English husband from Vienna. She is also known to Arnold. ‘Edith’ checked the recommendation and got confirmation from all our Viennese friends. In Vienna the press reported on the happy marriage of a young Viennese woman with a prince of the court of Ibn-Saud (clippings will follow). According to the Viennese friends of Edith and the ‘newlyweds’ themselves no one knows about their sympathies and work for the Party either in Vienna or on the island (with a few exceptions). Sonny was never a member of the Party and tried to hide his sympathies for the Party, since he was planning a diplomatic career after Cambridge. Edith’s references on Sonny are highly positive.”

It is hard to decide who is being deluded here. The first astonishing difference is that Arnold’s acquaintance with a member of the happy couple has shifted to Litzi (‘she is also known’). But here the ‘also’ makes even less sense, as it cannot sensibly be as juxtaposition to Edith, and to claim that Arnold knew Litzi as well as Kim at this stage would suggest that, in Vienna, Arnold had been more closely acquainted with Kim than Litzi! Again, the lack of the original text in Russian is enormously frustrating: it is difficult to imagine how either Tsarev or Borovik could have misconstrued this simple sentence. If there is one thing the Russian language is precise about, it is the gender and declension of personal pronouns. Thereafter the anomalies concern the business of the marriage, and the political sympathies of Litzi and Kim. Why a rezident in London would be informing Moscow of Viennese press reports, and promising to send clippings, when the NKVD was surely digesting them itself, is illogical. Furthermore, the notion that Kim and Litzi had been able to escape attention, and keep their sympathies private, is absurd, given that the whole point of the marriage had been to allow Litzi to escape before she was arrested, and that Litzi had used her new British passport to perform missions to Czechoslovakia in March and April 1934. (This knowledge was revealed by Helenus Milmo to Philby when he interrogated him in December 1951.) Lastly, the idea that they could possibly have undertaken work for the Party ‘on the island’ (i.e. in Britain) is ridiculous, given that they arrived only a few weeks beforehand. And what about those ‘exceptions’? Would Moscow not have demanded an instant explanation? It is all a charivari.

Recruitment

Given that all four could conceivably have known each other, in the short time between Edith’s release from prison and her departure with Alex that overlapped with Kim’s first few weeks in Vienna, when was each recruited by the Soviets?

‘Recruitment’ is a nuanced notion. A candidate could be watched performing useful assistance (perhaps as Kim was when he started aiding Litzi) before being signed up. Various couriers and helpers were used without stringent testing of their loyalty. In Stalin’s Agent, Volodarsky comments on Arnold’s claim of recruiting Edith in London, as reported in The Crown Jewels (p 106). Arnold had written: “In February 1934 I went to London where I recruited Edith, whom I already knew in Vienna.” (Was that a deliberately vague statement, since it must have referred to an earlier period, as Edith had left Vienna before he arrived? And why does Arnold completely overlook the critical encounter with Kim in his biography?) In an Endnote (p 545), Volodarsky writes: “Regarding her [Edith’s] recruitment at the time, it was perhaps a pun rather than an error or slip of memory. In Russian, the expression privlekat k cotrudnichestvu (to co-opt an individual) and verbovat (to recruit) can often substitute one another. Edith was indeed co-opted to carry out Soviet intelligence assignments while in Vienna but was formally recruited as an agent much later (see Appendix II).” This is not all that helpful, especially since Volodarsky in the Appendix clumsily writes that EDITH ‘was recruited by Deutsch in 193? [sic]’. He finesses the whole troubled saga of Edith’s recruitment, suspension, and re-activation.

Be that as it may, and irrespective of whether those two terms were really used interchangeably, any approach concerning a firmer commitment would have been made carefully, normally through ‘false-flag’ manœuvres (for example, Guy Burgess suggesting ‘working for peace’, without mentioning the Comintern; Reif referring to ‘anti-fascist’ activity), and the critical assessment made by someone who will not easily be harmed (e.g. Arnold taking precautions over the interview with Kim). [Costello and Tsarev offer a useful summary of the process in Note 14 on p 451 of Deadly Illusions.] But once a commitment was made, there was no going back. When the Nazi-Soviet Pact was announced, giving an opportunity for hirees like Goronwy Rees to falter, Burgess wanted him killed, lest he betray them all. If they did not receive explicit warnings about apostasy, agents would have been well aware of how Stalin’s organs chased down and killed defectors or traitors.

It seems certain that Edith had become a serious agent during her relationship with Arnold, and before she came to England. Borovik writes that Arnold recruited her in 1929. The Crown Jewels, using Arnold’s KGB file, states that in 1930-31 a girl he knew introduced him to an officer in the (O)GPU [see below], who entrusted him with a few tasks. “Deutsch in his turn introduced the Soviet intelligence officer to EDITH, who later went to Britain.” Arnold should perhaps have presented that information in his c.v., but again may have wanted to suppress any connections because of his affair with her. In any case, that evidence would seem proof that Edith was a fully signed-up member of the Soviet Intelligence Service when she was sent to Britain in 1930. (This reference to EDITH is maddeningly absent from the Index to The Crown Jewels, which also erroneously lists her there under ‘Hart’.)

The comments that Edith expressed in her letters, especially those concerning Maurice Dobb, indicate that she indeed had an important subversive role to play at that time. David Burke has revealed that Edith kept up a correspondence in 1930 with Trevor Blewitt, who was having an affair with Phyllis, the wife of Maurice Dobb, and who eventually married her in 1934. He states that it was MI5’s interest in Blewitt, and in his friendship with Edith, that led to her arrest at the Trafalgar Square demonstration in late October 1930. Yet the clumsy and visible actions of protest in which she and Alex took part in indicate that she was either poorly-trained, or was disobeying instructions. Her being expelled as a known agitator should have prompted Moscow to consider her a permanent liability, since she would obviously be surveilled if she ever returned to the United Kingdom. (Volodarsky provides the link between Arnold’s statement and the Reif telegram by informing us that the officer to whom Arnold introduced Edith in Vienna, namely Siegmund [ZIGMUND], was one Igor Lebedinsky, the legal rezident, who also went under the name of Igor Vorobyov.) One would assume that Arnold knew about Edith’s past problems with the British authorities, and that he was simply recommending her for work in Austria.

Thus Arnold’s claim that he ‘met’ Edith soon after his arrival in Britain, and that she ‘immediately agreed to work for us’ sounds very bogus. Moreover, Edith’s claim about the ‘secret network to which she belonged’ can be seen to be mendacious in the context of her recruitment. It would again have been poor tradecraft for her to know of the existence of a network and its members – and certainly so just after Deutsch brought her in. The arrangement of the rendezvous also reflected poor judgment on the part of this ace subversive. Nevertheless, if he really had been intent on recruiting Edith, he would presumably have had to gain permission from Moscow before re-engaging such a volatile property. I return to the texts: the references to her suggest some subtle distinctions. Costello and Tsarev introduce her as follows: “Through Edith, who is known to you, who had worked for some time under ZIGMUND in Vienna, . . .”, while Borovik offers a slightly different spin: “Through ‘Edith’, whom you know and who worked at one time for Siegmund in Vienna . . .” Yet the original text seems tentative. If Edith is known to Moscow, why does that have to be spelled out? Perhaps it is a suggestion that Edith had been made dormant, but has now just been resuscitated, reinforcing the comment made by Arnold.

Given that uncertainty, the attention given to Edith’s prestige and influence is quite remarkable. It is she who checks the recommendation (although the translators differ over ‘credentials’ and ‘recommendation’) and receives confirmation about the genuineness of the two new candidates from her Viennese friends, a fact that both commentators agree on. The charade is maintained that Edith’s friends in Vienna are recommending both ‘the former Austrian Party member’ and her husband as candidates for recruitment, but it is not clear why Litzi cannot be named, unless the custodians of the archive thought that in some way they could disguise her identity, and regarded her anonymity as paramount. Moreover, it would appear strange that, having received written testimonials, Edith would then have to verify them with her erstwhile comrades.

Exactly how Edith managed to communicate with these people in such short order is never explained – as if letters could be safely entrusted to the mails without interception, let alone the fact that the events all took place quite speedily in that hectic May/June period. Telephone calls? Highly unlikely, I would say. Moreover, the telegram asserts that the anonymous Party member (Litzi) had arrived with recommendations for Edith. Again, apart from the fact that we know that they had been acquainted for some time, and had agitated together, it would have been quite extraordinary for such endorsements to be sent to Edith, presumably as ‘letters of credit’ that Litzi brought with her, if Edith had only just been re-recruited by Arnold. What may be significant is that Peter Smolka paid a visit to Vienna that summer, leaving London in early July and returning a month later, so he may have been used as a courier to verify the references.

And then Edith makes an independent decision that Kim is a superior candidate over Litzi for the undercover Soviet network to which she (Edith) already belongs. Was that selection within her authority, or is the narrative an attempt to bury the potential for Litzi to have any role at all? As I have written before, the NKVD considered Litzi a far more important prospect than Kim at this time. This seems to me to be a classic example of disinformation, a rather disingenuous attempt to draw attention away from Litzi to Kim at a time when Litzi was established, and Kim represented a very speculative venture. Again, I refer to Kim’s statement to Borovik that Arnold knew him already and had sought him out – probably a foolish claim designed to amplify his own importance that undermined the whole shaky edifice of the Legend of Edith Tudor-Hart. In KGB: The Inside Story, Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky, exploiting the latter’s insights, even declare, shockingly, that ‘Deutsch arrived in England with instructions to make contact with Burgess as well as Philby’. That has alarming possibilities, since Burgess had not yet visited the Soviet Union, and his name could hardly be known by the OGPU/NKVD. Overall, however, it is another sorry mess.

But when did Litzi become a recognized Soviet asset in the West? And when did she become MARY? References are few. Volodarsky writes: “As mentioned, in February 1934 Deutsch went to London alone and Reif joined him there in April. They worked together until June, when Reif left for Copenhagen again. By the summer their network of agents, helpers, talent-spotters, and couriers included Edith Suschitzky (alias ‘Betty Grey’); her husband Alexander Ethel [sic] Tudor-Hart (alias ‘Harold White’); Alice ‘Litzi’ Friedmann, the first wife of Philby, later recruited as agent MARY; Kim Philby himself, then only a candidate for recruitment; agents PFEIL (also GERTA or HERTA, in Russian STRELA, unidentified, . . .”. I should also mention that Christopher Andrew, in his history of MI5, exploiting yet another unidentifiable source in the Security Service archives, cites (p 169) a statement that Kim made ‘on the eve of defecting to Moscow’ – a bizarre construction given that Philby was in Beirut, far away from MI5, at that time: “. . . Lizzy came home one evening and told me that she had arranged for me to meet a “man of decisive importance”. So much for tea and sandwiches at Edith’s place: MARY had been hard at work.

Volodarsky regrettably does not offer here a date for Litzi’s ‘later’ promotion to MARY, although in an Appendix he states that MARY was recruited in 1935 by Deutsch with the help of Edith Tudor-Hart – another illogical observation. On the other hand he implies that a whole bevy of hangers-on could be entrusted with important roles without yet being ‘recruited’. It may or not be notable that he does not credit Edith with being EDITH, yet he confirms that Edith and Alex were ‘recruited’ in some way. (It is simply difficult to imagine Alex as anything but a fully committed agent.) Yet in an endnote he denies that the pair were STRELA: “In both The Mitrokhin Archive and TNA: PRO KV2/1603, Edith Tudor-Hart is said to be sharing a joint code name STRELA/PFEIL with her husband Alexander. However, further research revealed that PFEIL and EDITH were recruited at different times and in different places; besides, in the balance sheet of the London NKVD station of June-July 1935 both PFEIL and EDITH are mentioned as receiving payments for their foreign travel.” What to make of this? Was PFEIL perhaps simply Alex, recruited in Vienna? And did Edith really travel abroad in this period? I can find no record of such movements, either in her MI5 file, or in Jungk’s narrative. And the problem with Volodarsky’s accounts is that he appears sometimes to be as reliant on unidentified sources as do Costello and Tsarev.

Borovik puts his own spin on the process, again showing his haphazard grasp of chronology and geography. On page 301 he writes: “It was she [Edith] who brought him [Kim] to a bench in Regent’s Park. . . . It was that woman who helped form their entire group. Austrian by birth, she had emigrated to England and married an Englishman. Philby thought that Edith had started working with the OGPU either in England or in Austria [a safe guess!].” And Borovik added a note: “From the archives, it seems that Edith Tudor-Hart was recruited by Deutsch (‘Stefan’) in 1929. In 1934 she recruited Litzi Friedmann (‘Mary’) and recommended Philby for recruitment.” Apart from the fact that Litzi had married her Englishman in Vienna, and thus was no longer ‘Friedmann’, and that elsewhere (in Deadly Illusions) Edith had supposedly rejected Litzi as an inferior candidate for agent work, and that there seems to be no other suggestion that Edith had the authority to recruit Litzi (let alone before she recommended Kim), who, as the senior partner, would not have needed recruiting by Edith, this seems an utterly convincing example of NKVD propaganda.

I have previously pointed out a reference to MARY, in my piece from last March, at https://coldspur.com/litzi-philby-under-the-covers/. The British intercepted a message sent on November 7, 1934, from a Soviet agent in the London suburbs to Moscow that reports on MARY’s ‘safe arrival’, suggesting perhaps that the cryptonym MARY had been applied to Litzi when she was in Vienna. Yet the message carries some ambiguity: was six months an inordinately long time to report the ‘safe arrival’ of an agent when the rezidentura had already described her arrival several months before? Moreover, the context and the content of the message, referring to Litzi’s ‘artist friend’, do not appear to make a lot of sense. Nevertheless, I stick to my previous conclusion that Litzi was regarded at this time as much more important than Kim, and that the marriage had been encouraged as a way of facilitating her entry into the country.

Kim’s Recruitment

As for Kim, the story of his recruitment is inevitably riddled with contradictions. Costello and Tsarev point to Kim’s visit to the CPGB HQ, immediately after his return, as proof that he had not been recruited by then, as it would have been a foolhardy venture for any new recruit to be seen near King Street. But of course we cannot be sure that Kim’s account of that visit has any veracity, no matter how colourfully he related it to Borovik. We have the evidence from Knightley that Kim told his offspring that he had been recruited in 1933, and Pincher recorded that Kim had told Nicholas Elliott in Beirut that Deutsch had recruited him in Vienna early in 1934. Moreover, the timeline of Kim’s movements in London in May 1934, as described in the chapter of his biography supplied in The Private Life of Kim Philby needs to come under close scrutiny.

Within a day or two of the couple’s arrival (so Kim wrote), they [sic] visited the CPGB HQ, introducing themselves to Willie Gallacher and Isobel Brown of the communist elite, who were presumably fortuitously both present and available for the encounter. (In a careless, throwaway line, Kim told Borovik: ‘One of my friends, I don’t remember who, warned them that I was coming, and they let me in.’ He thereby indicates that he went to the Embassy alone!) Having been given the brush-off, and told to come back in six weeks, Kim applied himself to completing the forms for his Civil Service application – another couple of days, perhaps. Seale and McConville indicate that he then sent off letters to potential referees in Cambridge, and a flurry of correspondence occurred. The authors are very prodigal with supplying dates, however: it is not clear whether all this happened before the supposed meeting with Arnold – an event of which the authors were totally ignorant. Cave Brown claims it occurred after the meeting with Deutsch.

Then, ‘after a few days with my parents’ (a lie, as his father was absent in Saudi Arabia at this time), he and Litzi moved into a furnished room in East End Lane. He does not state how long it took to find this abode. Here appears another conflict, since Reif’s telegram reported that he had ‘worked out a plan for Arnold to meet with SÖHNCHEN before SÖHNCHEN moved to his father’s flat’. Cave Brown introduces a possibly important factoid here, having apparently had access to the archive of Kim’s father, St. John. He writes (p 182) that St. John had asked his mother, May, to ‘inspect’ Alice, and that she found the couple ‘pigging it’ in a scruffy unfurnished room which they shared with a Hungarian, possibly Peter Gabor, ‘who had introduced Kim to Alice’. Yet Cave Brown cannot be relied upon easily: he backs this anecdote up with the claim that Dora Philby was ‘still on the high seas’ at this time, with St. John present in London, when the situation was in fact reversed.

In any case, Kim resumed his studies in his new accommodation and renewed contacts with old friends – perhaps another week? He visited Cambridge to meet with pals from the Cambridge University Socialist Society. Seale and McConville are again the source for this, but are still distressingly vague about dates. (We do know that Guy Burgess wrote to Isaiah Berlin in May, informing him that Kim had just returned from ‘fighting in Vienna’, so the Cambridge visit must have preceded the Regent’s Park business.) Lastly, Kim claimed that he and Litzi on May 1 went to Camden Town to join the annual May Day march. This is either a sloppy sequence of chronology, or a clumsy invention. If taken literally and logically, Kim’s narrative would indicate that they had been in the country two or three weeks by then, leading to a projected arrival date of about April 10.

Yet Milmo (as I explained in my March 2023 piece at https://coldspur.com/litzi-philby-under-the-covers/ ) had confronted Kim with the fact that Litzi had used her new passport to travel to Czechoslovakia as late as April 14, 1934. (Costello and Tsarev wrote that she had to wait two months after the marriage on February 14 to receive her passport, which obviously cannot be right.) Given that she had to return to Vienna, and that the couple then travelled by motorcycle across Europe, stopping in Paris for sightseeing purposes, the chronology can instantly be seen as utterly impossible. Even if we can trust the statement in the Smolka archive that the Philbys left Vienna on April 28, and that Kim’s account of his activities was not related in chronological order, the key event of May 1 makes the whole edifice crumble. Philby must have concocted a complete fantasy, and presented the sequence of events utterly carelessly. Edward Harrison is right in suggesting that Kim wanted to protect the Tudor-Harts since they had been ‘the central link joining activists from Cambridge, Vienna and London in an international communist conspiracy’. But what he does not state is that the ruse itself must have been fuelled by his Moscow bosses.

Moreover, we have Kim’s inconsistent accounts of the set-up with Arnold to deal with. I referred earlier to the mysterious note in the MI5 files where Kim explained that Litzi came home one evening and told him that she had set up a meeting with the man ‘of decisive importance’. In his autobiography, Kim switches the activity to a male friend whom he had seen two or three times since returning from Vienna. (The implication is that the friend was English.) This friend confided in him that he had been approached by a man who had heard of his Viennese exploits, and was interested in talking to him. He was told not to say anything to Litzi yet, and Litzi was fittingly ‘too disciplined to ask questions’ when he returned home. By the time Kim speaks to Borovik, he casually mentions that ‘a man whom I had met in Austria sought me out’: now it is ‘a very serious person’ who could help with Kim’s career supporting the cause that his acquaintance wants him to meet. When the rendezvous is made, the person who led him there is more explicitly identified as an ‘Austrian friend’. The former ‘man he had met’ has been transformed into a ‘friend’. Kim eventually informed Borovik that this person was Edith Tudor-Hart.

And what about the view from Moscow? Nikolai Dolgopolov claims to have had access to the Russian intelligence archives at Yasenevo, but there are no footnotes or endnotes in his narrative, and his book conventionally does not carry an index. He includes some official telegrams in an Appendix, but none earlier than 1941. He provides a rather shaky chronology, showing that Deutsch arrived in Britain in 1933, not 1934. He does declare that Kim worked as a courier in 1933, but was not recruited until June 1934 – in fact, a somewhat premature assessment. Thus it is not possible to determine whether Dolgopolov is simply using the same sources as conventional western historians and journalists, or whether he had access to some original documents. As an aside, in describing Litzi’s escape to England, he rather coyly introduces the maybe gratuitous comment that ‘Kim did not like working with women. He preferred to socialize with them in other ventures, and different situations’. One can understand the implications of the second part, but the first assertion is not borne out by the facts.

His account of Arnold’s and Edith’s roles in the recommendation of Kim is thus familiar and humdrum. He provides a sketch of Edith, but it is very spotty, and does not perform justice to her complex background. He makes out that it was Arnold who laid before Edith her anointed role as a talent-spotter, but he provides no insight into her connections with Maurice Dobb from some years before, and overlooks completely the story of Edith’s expulsion. His overall message is to attribute to Edith a major role in determining Kim’s destiny as a spy. He assumes that Litzi introduced Kim to her, but allocates Litzi overall a very minor role, perhaps taking on a function parallel to her husband. He records the meeting with Deutsch, but does not quote or discuss any of the infamous Reif telegram. It is all very bland.

Surprisingly, Vladimir Antonov gives a more lively account of Kim’s recruitment than does Dolgopolov. He provides more historical and biographical background information, and declares that he has actually studied the Tudor-Hart archive. Yet his story is very conventional. He does mention one or two western sources (such as Seale’s and McConville’s Long Road to Moscow), but overall follows Philby’s narrative line. He offers more background information on Edith and her hasty marriage to an ‘aristocrat’, and he echoes the familiar claim that she and Kim became acquainted in Vienna, where she was able to assess his potential. He provides one or two clues on chronology, stating that Litzi and Kim left Vienna in May, travelling to London via Paris by motorcycle, without realizing that that assertion drives a coach-and-horses through Kim’s claim that he attended the May Day parade. Antonov allocates an imaginative role for Edith in London, confirming that she quickly met up with Deutsch, was given the task of talent-spotting, and, when she learned of Kim’s visit to the CPGB HQ, she quickly had to set up the meeting. Antonov expresses surprise that the British authorities never arrested Edith, after its intense surveillance, but never explores the paradox of why the NKVD continued to use such a vulnerable and obvious subversive. It seems he is following the Party line.

Interim Conclusions

I draw two major observations from this analysis: 1) that Kim Philby’s mendacious testimony has been accepted and promulgated by too many writers who ought to know better; and 2) that the archival material concerning the events of 1933 and 1934 is distressingly frail.

Philby’s accounts of his activities, in his memoir, in the recovered chapter that was omitted from My Silent War, in the biography he submitted to the KGB, in the interviews he gave to various journalists, from Knightley to Borovik, and in what he told his own family, are notoriously unreliable. I say that because of the obvious chronological impossibilities, but also because of the blatant contradictions. For example, he said he went to the Embassy with Litzi: he also stated that he alone was let in. He identified Litzi as the person who introduced him to Deutsch; he also claimed that it was a male he had known in Vienna; he finally admitted that it was Edith. He claimed that he stayed with his parents in Hampstead – but his father was away in Saudi Arabia. He said he had been recruited in Vienna in 1933. He said he had known Deutsch in Vienna: he presents the Regent’s Park encounter as a first exposure to him.

What surprises me is not that he lied and dissembled so much: that was his métier as a spy. The astonishing aspect for me is that he has been allowed to get away with it. Good agents are supposed to be meticulous in representing the details of their life. All it takes is a careful comparison of his claims, and the construction of a solid timeline, complemented by a correct geographical context, to identify the holes in his story. Of course, analysts can state that, yes, he dissimulated (about Edith, for example), as he needed to protect her. But then one cannot simply accept everything else he wrote simply because it sounds plausible, and adds some romantic glow to his adventures. For there are no third-party confirmations of the claims he made – of the date he and Litzi arrived in the UK, of the visit to the CPGB, of the May Day parade, of his visit to Cambridge (apart from the valuable Burgess-Berlin exchange), of the park-bench meeting with Deutsch. Yet these stories are echoed and solemnly sourced in the biographies and ‘histories’ of the period.

And that leads on to my second observation – that the archival material is very bizarrely silent about these crucial events. Why were there no documents placed in M5’s Tudor-Hart file at the time, reflecting Edith’s anguished letter of appeal for Alex to come and rescue her, Alex’s reply, Alex’s travel to Austria, the procedural challenges to the marriage before it actually took place at the Embassy in Vienna, or their arrival at customs in the United Kingdom? Either side of the critical period, both Alex and Edith were being closely surveilled. Yet interest seemed for some reason to evaporate between 1931 and 1935. That information was being maintained on their activities can be verified by later posts in their files, but the gaping hole in the records for the most critical time in their careers is simply inexplicable according to most norms. For instance, the later posts refer to complications and obstructions concerning their marriage: how were these overcome, who intervened, and why? It is so clumsy that it provokes most searching doubts about the policies and objectives of the intelligence services.

And what about the Russian archives that were opened for a few vital years? Costello and Tsarev identify a Tudor-Hart file alongside the multiple extracts from the Deutsch and Orlov files. In Note 48 to Chapter 5, they refer to a profile of her submitted by Deutsch, which can be found in ‘File no. 8230 Vol. 1, p. 52’. Yet this is the only extract that I could find in their book! Surely a file that contains at least one volume, and several dozen pages, should have more useful revelations to disclose? The authors astonishingly note: “Precisely when Edith Tudor-Hart arrived in Britain is not clear from her file, but it was 1933 and almost certainly May, the year before Philby set out for Austria.” If the NKVD/KGB did not keep track of her movements, and were dismally wrong about the timing of her escape to Great Britain, yet dedicated that many pages to her, how important could she have been, and what nuggets could have been found there? The lack of interest displayed by the authors is almost shameful, but unfortunately both are now dead.

Moreover, West and Tsarev failed to grasp the nettle a few years later. Their coverage of Edith is remarkably patchy, and they make some egregious mistakes. In a Postscript, they boost her reputation by crediting her with establishing the Oxford ring through ‘the mysterious’ SCOTT (Arthur Wynn, whom they do not identify), but their evidence is thin, citing a report to Moscow in October 1936 where Edith was simply attributed with the opinion that SCOTT had even more potential than SÖHNCHEN. The biographical information on her relates mostly to her photographical career in England, and uses no fresh material from her KGB file. Moreover, the authors clumsily state that the only link that MI5 was able to establish between Kim and Edith was that her former husband had been a contemporary of Kim’s at Cambridge. But Alex Tudor-Hart attended the university with Maurice Dobb, not with Philby.

Jungk’s Quest

The possibilities of unearthing fresh secrets about his controversial relative consumed Peter Jungk. He wrote to the Moscow authorities. After first receiving a brush-off, and being referred to the Swiss Red Cross for information in Edith, he gained an introduction from a Professor K., at Graz University, to Sergey Ivanov, the director-general of the FSB Archive. The written reply he received stated that the institute had no information to give him, that the public was not allowed access to its archive, and he instead pointed Jungk towards Deadly Illusions! Undeterred, and without speaking Russians, Jungk decided to visit Moscow to seek his fortune.

Quite extraordinarily, he was able to gain access to the Comintern Archive building and present his question, aided in translation by a young American who happened to be undertaking research on Zinoviev. He asked about any files on Edith Suschitzky/Tudor-Hart. The archivist disappeared, returning after twenty minutes to inform Jungk that they had no files on Edith. Jungk could not believe it. He thus contacted by telephone Nikolai Dolgopolov, who had just published his book on Philby. (That dates the events as around 2019, by which time Putin had severely tightened the screws on the availability of intelligence secrets.) When Dolgopolov understood his relationship with Edith, he happily agreed to a meeting: he spoke English perfectly.

The encounter with Dolgopolov was a touch bizarre. Dolgopolov claimed that he had had access to the Philby files in the archive for the purpose of writing his biography, which Jungk describes as ‘durch und durch űberraschende’ (‘utterly startling’ – although how he could make that judgment is not clear). As Dolgopolov read passages from his book, translating as he went along, it occurred to Jungk that they reminded him of what Borovik, who had been able in 1988 to exploit the KGB archives shortly before his death, had written. But Borovik’s book was available only in English. Jungk thus asked him whether he was familiar with The Philby Files, to which he received the slightly uncomfortable reply from Dolgopolov that he had never been influenced by Borovik, attributing the fact that the texts sounded similar to his acquaintance with Kim’s widow, Rufina.

The meeting ended awkwardly. Dolgopolov poured water on any notion that Jungk might be able to gain access to Rufina, or the files, and then made some discourteous comments about Jungk’s father when he realized that his visitor was the son of Robert Jungk. He made some arrogant and tactless remarks about his own residence in Paris in the 1980s: Jungk realized that his interlocutor had been a KGB officer. Moreover, Jungk concluded that even the expert biographer had nothing more to reveal than what could be found in Borovik’s book. He tried to see Borovik, but the latter was too ill to have visitors – or even to discuss Dolgopolov’s biography and research over the telephone. His friend Petrov reminded him how protective and insular the Putin regime had become, and how the group Memorial had been policed and constrained.

In the last chapter of the saga, Jungk was introduced to a former Colonel in the KGB, Igor Prelin, who was a close friend of Sergey Ivanov. Prelin explained to Jungk that, in the early 1960s, he had personally been involved with transferring the files on Edith from the less secure Comintern building to the highly secret KGB archive. If Jungk wrote a letter to him outlining his needs, he would ensure that he received Ivanov’s attention. He even pointed out to Jungk the building where the records of the FSB (domestic intelligence) and the SVR (foreign intelligence) were kept. Jungk thus wrote a simple letter, and handed it to the unreconstituted KGB loyalist (who regarded the break-up of the Soviet Union as a tragedy). Jungk’s spirits were raised: he had to leave Moscow, but eagerly awaited the outcome.

After a few days, he heard from Prelin that his request had been acknowledged. Prelin was optimistic. Jungk then had to wait another three months before he received his answer, again transmitted via Prelin: “Can you get hold of the book Deadly Illusions by John Costello and Oleg Tsarev, which was published by Verlag Crown in 1993? This book contains on pages 133-139, 142, 154, 207 all information on this foreigner that the SVR Archive has released and passed to O. Tsarev.” Jungk decided that he should better laugh than cry, and thanked Ivanov for his efforts.

Russian Archives

So where do things stand? Can these Russian archives be trusted?

First, just because the Russian authorities claim that highly confidential records were transferred to more secure facilities in the 1960s, it does not necessarily mean that files on Edith Tudor-Hart were among them. After all, Ivanov did voluntarily recommend that Jungk inspect Deadly Illusions to ascertain what research was available. Moreover, if the files had been made even less accessible, how was it that Tsarev was able to study any of them? Furthermore, if he did access them, how come that the only item of interest concerning Edith that he reproduced was a very anodyne and equivocal biographical sketch of her by Arnold Deutsch? If Edith had been an agent of some substance and achievement, it would have been far more probable that, during the last few years before the Soviet system fell, the KGB would have highlighted her achievements, as they did with Ursula Beurton (née Kuzcynski), Melita Norwood, and Kim Philby himself.

It seems to me more likely that the NKVD/KGB had very little information on Edith, and did not know much about her career. She was someone whose name occasionally cropped up in telegrams, but did not merit special attention. Indeed, since the only known entry is the biographical detail by Deutsch that disparages her reliability, one might imagine that they discouraged using her at all. Yet that hypothesis immediately has to deal with the paradox of the apparent size of the ‘Tudor-Hart file’, No. 8320, of which Volume 1, with at least fifty pages, is identified. Why, if Tsarev was able to get his hands on it, did he not reveal more of its contents? If it had been filled with junk entries, why did he not draw attention to that fact? Moreover, since Jungk should have been aware of its identity, why did he not describe it accurately in the letter he sent to Ivanov via Prelin?

We must remember that Costello’s and Tsarev’s work was undertaken with the guidance of the KGB, as a propaganda exercise to improve its image. The Chairman of the KGB, General Vladimir Kryuchkov, had made that decision in 1990, as a means of countering what Andrew and Gordievsky had recently published in KGB. The focus of Deadly Illusions was to provide a very positive account of Alexander Orlov, the defector who had challenged and defied Stalin, but who had remained loyal to the mission of the Soviet Union and the KGB by not betraying any of the penetration agents still active in the West. John Costello wrote that Kryuchkov ‘approved the policy of making selected historical records public’, but that careless and inaccurate statement distorts the means by which Tsarev (and he alone) was able to inspect the archives of the KGB. The process of ‘publication’, or ‘declassification’, of archival material normally implies that any researcher can inspect it, and verify sources.

Boris Volodarsky has been quite scathing about the reliability of The Deadly Illusions. In his 2023 book, The Birth of the Soviet Secret Police, he points out that Tsarev had been a KGB operative working in London, until he was expelled in the early 1980s, whereupon he was employed by the Press and Public Relations office of the KGB. Volodarsky also questions Costello’s competence as a historian, suggesting he accepted whatever documents he was given at face value, because of the monetary reward. Volodarsky’s conclusion? “Nevertheless, it became an international bestseller and is still being quoted as an indisputable source by many intelligence writers although it has long been exposed as a fake history, a KGB deception.” Volodarsky’s comments would have been more useful if he had translated that last passive clause into a more active explanation.

Tsarev gives the impression that he was allowed fairly free rein among the rather chaotic sets of documents in the First Chief Directorate headquarters at Yasenevo. (He admitted that the collections could hardly be classified as ‘archives’ in the western sense of the word.) He describes speculative paper-chases that involved looking at much irrelevant material before possibly coming up with reports of value. He writes that many of the documents were undated, or had wrong dates, and that ‘some of the reports in the files are not even stitched into the bound volumes in chronological order’. Thus an immediate paradox appears: if the documents were so chaotic, how come his text and Endnotes regularly include apparently precise identification – such as with the ORLOV, DEUTSCH, PHILBY, MACLEAN et al. files? And that goes for TUDOR-HART as well. Is it possible that these identifiers were created retroactively, in order to offer a stronger impression of authenticity? In these circumstances, the existence of a tidy operational file dedicated to Edith Tudor-Hart seems very bizarre. On the other hand, if the sole identifiable reference was for No. 8320, it may have been because that was the only document on Tudor-Hart that was given to him – or on which he alighted serendipitously, and he (or his minders) decided that it should be given a number.

At a high level, Christopher Andrew described this tortuous process in the first chapter of The Sword and the Shield, the compilation based on documents smuggled out by Vasiliev Mitrokhin, which was published in 1999. These revelations greatly irritated the SVR (the Foreign Intelligence Service), which must have believed that it had been in control of the whole release process. It was, however, very disingenuous of Ivanov to pretend, when responding to Jungk, that these disclosures had never occurred, since a secondary swipe at the material had obviously taken place – without authorization. For some reason, Jungk does not appear to be aware of the Mitrokhin exercise or of this volume: else he would surely have mentioned them, or commented that Prelin’s claims that all highly secret documents had been moved to inaccessible storage some decades before, never to be seen by Westerners, were a hollow sham.