Over the past few months I have been collaborating with a researcher in the UK over a WWII mystery. Nigel Austin, who had been investigating the puzzle, found me on coldspur, and contacted me. We quickly determined that our knowledge was complementary, and that we could work together remotely. Now, having almost exhausted our research sources, we are ready to start telling our story.

The piece below serves as an introduction to our planned article, as well as a teaser. We present it here with two goals in mind: 1) to seek any insights on the operation that coldspur readers may have; and 2) to ask whether any reader has suggestions, or better still, contacts with any magazine or periodical that would be keen to publish our final piece. Please write to me at antonypercy@aol.com if you have any contributions or ideas.

‘The Airmen Who Died Twice’ by Nigel Austin and Antony Percy

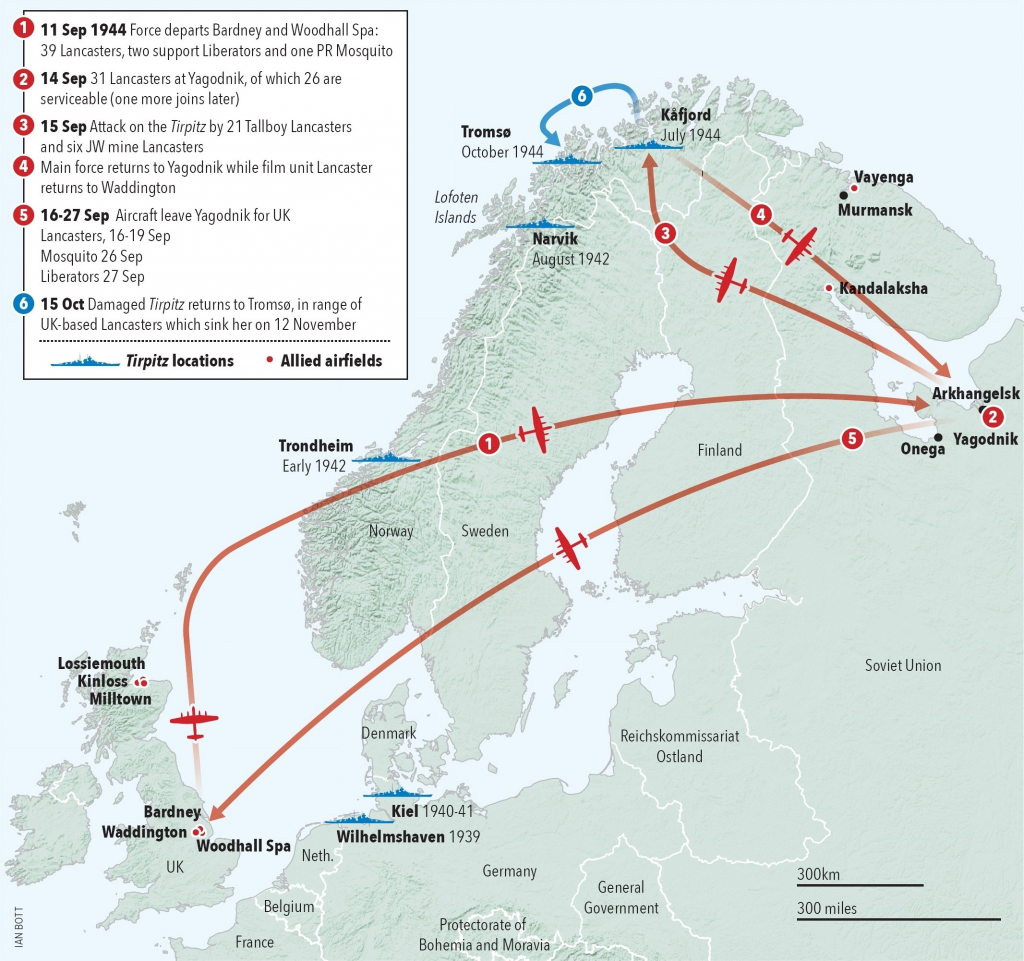

On September 11, 1944, two squadrons of Lancasters, Numbers 617 and 9, left Bardney and Woodhall Spa in Lincolnshire to fly to Yagodnik airfield in the north-west of the Soviet Union, near Archangelsk. Some aircraft stopped at Lossiemouth in Scotland for refuelling. Their mission was to use Yagodnik as a staging-post, for further refuelling, and then attack the German battleship Tirpitz, berthed in Alta Fjord in northern Norway. This fresh operation, named PARAVANE, had been conceived as a way to exploit the ‘Tallboy’ bomb that had proved its efficacy against U-Boat pens along the Normandy coast, as part of the preparation for D-Day.

The closer proximity of Yagodnik to Alta Fjord, and the desire to attack from the south-east with an element of surprise, made the location doubly attractive. Despite recent spats between the Allies over the US airbase in Poltava, and Stalin’s refusal to assist the Polish Uprising, Bomber Command had gained Stalin’s agreement to the operation at short notice. The Soviet leader presumably believed that the destruction of the Tirpitz would lead to the greater safety of the Arctic convoys, but he probably also had an eye out for gathering secrets of advanced British technology.

The journey to Yagodnik was not without peril. Communications with the Soviets were fragile, because of problems with radio frequencies and callsigns. The weather was poor. The outcome was that several of the Lancasters lost their way, and crash-landed just before running out of fuel. No deaths occurred, but some of the aircraft were thus unavailable for the attack, and could not be repaired in time for the return flight to Scotland. On September 15 the raids took place. The outcome was indistinct: smoke flares meant that the target was swiftly obscured, and damage could not accurately be assessed by photographic sorties. Yet all planes managed to return safely to Yagodnik.

With a smaller number of planes available to carry home the total number of crew-members, each plane that returned to Scotland on September 16 had to take on additional passengers beyond the standard crew-number of seven. At about 5:15 pm the first group of sixteen Lancaster bombers, with a total of a hundred and thirty-one crew, took off over a two-hour period to return to the UK, over the airspace of neutral Sweden, avoiding occupied Norway. Leading the group, Wing Commander Tait confirmed his safe return to the UK at 1:39 am on September 17, after a fair-weather flight. All the other planes returned safely, except the Lancaster piloted by Frank Levy, PB416.

For some reason PB416 took a path further north and west than the defined route across neutral Sweden and the Skagerrak. At 01.21 am on September 17 an acknowledgement for a location was received at RAF Dyce Aberdeen from Frank Levy’s Lancaster. The coordinates confirmed “a fix in position 60°50’N 009°45’E”. These bearings convert to a site near the village of Oystogo in rural Etnedal, South Norway – a remote grassy valley by a river, surrounded by steeply wooded terrain. It is fifty-five miles from the mountain at Saupeset, near Nesbyen, where PB416 crashed later that night. There were no survivors. Ten casualties were recorded, marked at the crash-site by ten nails on a simple cross, and later by their ten names inscribed on a memorial panel. Identifiable solely by their ID-tags, the bodies were buried in a mass grave. They were subsequently exhumed and re-interred. Ten white grave stones stand today in Nesbyen churchyard.

“These graves tell about freedom, they tell about young men fighting for their country and Europe against the Nazi tyranny”, Wing Commander Iverson eulogized on a visit to Nesbyen in 1987. “It is still a mystery how this could have happened”. Tony Iverson’s ‘mystery’ has generated much speculation since the crash. Why was a Lancaster, from an elite RAF Squadron, without bombs, alone, three hundred and thirty miles adrift from the rest of the Squadron over occupied Norway? Was it due to mechanical problems, a lack of fuel, pilot error, or bad weather? If the plane was lost, why did it report its location without mention of any of the above issues?

The RAF Flight Loss card for PB416 from 1944 bizarrely shows nine airmen. Among those identified as casualties were Squadron Leader Wyness and Flight Lieutenant Williams, who were ‘guests’ on PB416. Yet a few weeks later, on October 7, these same two officers were brought down during a raid on the Swiss-German border, at the Kembs barrier, and summarily executed. This article analyses the mystery of the airmen who died twice, and suggests why the Royal Air Force and the War Graves Commission have attempted to cover up the facts of this embarrassing disaster for nearly eighty years.