To welcome the New Year, I present a potpourri of current heartwarming stories, mostly from the world of intelligence. I wish all coldspur readers a happy, prosperous and inquisitive 2025!

[Coldspur: ‘Purveyor of Conspiracy Theories to the Gentry’ ®]

Contents:

When Victor Met Venetia

(An odd sighting of Victor Rothschild and Venetia Montagu, with links to Blunt, Burgess and Maclean)

False Alarms: Sisman, Trevor-Roper and Philby

(Philby is falsely accused of prolonging the war)

‘The Airmen Who Died Twice’

(Some reflections on the romanticization of many WWII memoirs)

An Update on the Blunt Confession

(MI5 engineered Blunt’s confession before the Attorney-General approved it)

Philby the ‘Double Agent’

(Further hints that Philby was admitted to be working for MI6 and the RIS at the same time)

Christopher Andrew and the Minor Biographies

(Did the renowned authorized historian actually read his latest book?)

Borodin: Deception, Defection and Interception

(The experts let me down)

The Biography of Margaret Thatcher

(A slight quibble with Charles Moore’s masterful biography)

. . . and an aside on awards . . .

(Exactly that)

Michael Holzman, Proletarian

(A bizarre re-appearance of Holzman’s indigestible Kim and Jim)

Ruthenia Revisited

(Culture is not inherited)

‘Richie Benaud’s Blue Suede Shoes’

(A famous 1961 Test Match, and my association with it)

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

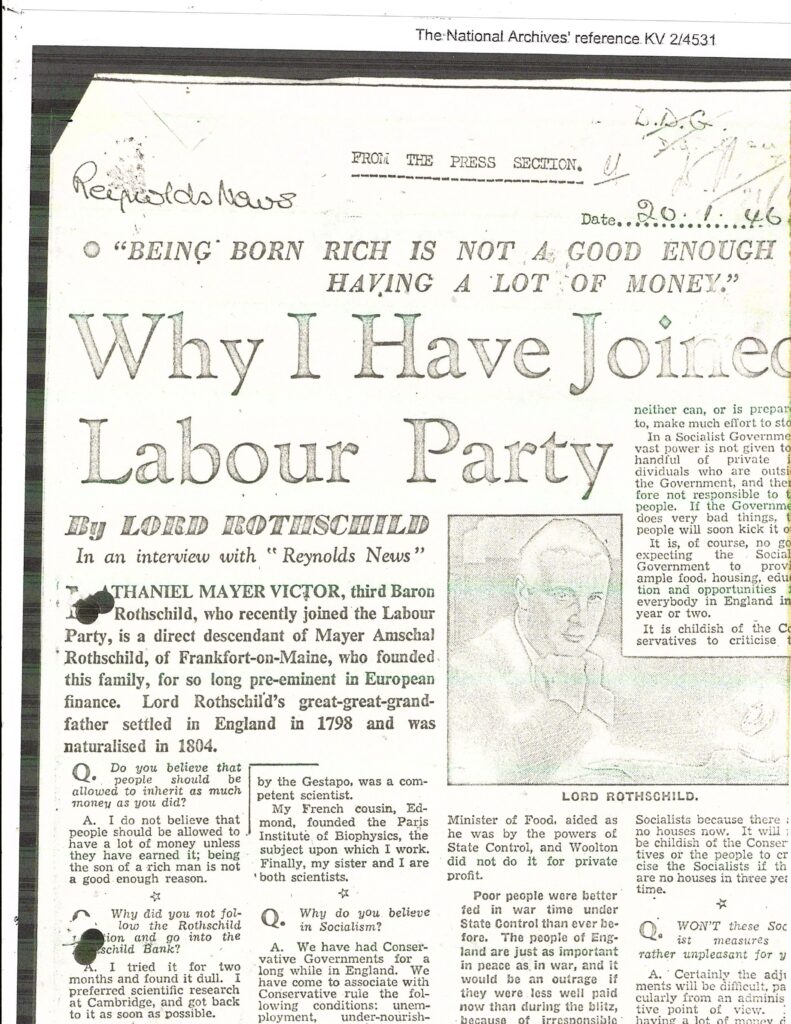

When Victor Met Venetia

While I was pursuing my research on Victor Rothschild, a correspondent alerted me to an article in the Daily Mail that claimed that the infamous Venetia Montagu (née Stanley) had had an affair with Rothschild (see https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-13804049/Torrid-trysts-bedroom-wheels-Prime-Minister-Asquith-lover-35-years-junior-lost-Britain-WWI.html ), where he is described as ‘the immensely rich scientist, spy and polymath Victor Rothschild’. (This article was prompted by the publication of a ‘novel’ about the affair between Prime Minister Asquith and Venetia, written by Robert Harris, and titled Precipice.) Now my immediate reaction was that such an alliance was highly unlikely: Venetia was twenty-three years older than Victor. It is of course possible that he could have been her toy-boy, but other snippets reinforced my doubts. The article suggested that Venetia’s described flings with her string of lovers occurred before 1924, when her husband, Edwin Montagu, died. Victor would have been a callow thirteen-year-old at Harrow School at that time.

It may have been a case of mistaken identity. The Mail itself, in an article in 2016, described Venetia’s fling slightly differently, as being with ‘the banker Victor Rothschild’ (see https://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/books/article-3634319/The-PM-daughter-love-girl-Venetia-Stanley-won-heart-Herbert-Asquith-host-men.html ). Now Victor never described himself as a ‘banker’ (or even a ‘bonker’), and he denied strongly the assertion of a certain ‘Colonel B.’ to that effect, as his memoir Random Variables explains (page 92). I initially suspected that, if a Rothschild had been involved with Venetia, it is much more probable that it was Victor’s father, Nathaniel Charles who was the Rothschild who had been enchanted by her. Charles (as he was known) committed suicide in 1923 by slitting his own throat. His obituary indicates that he had encephalitis, but maybe he was also lovestruck, and brought to despair by the fact that Venetia no longer had time for him? While a keen entomologist and conservationist, he was primarily known as a banker. Victor excluded any mention of his father in the few memoirs he recorded.

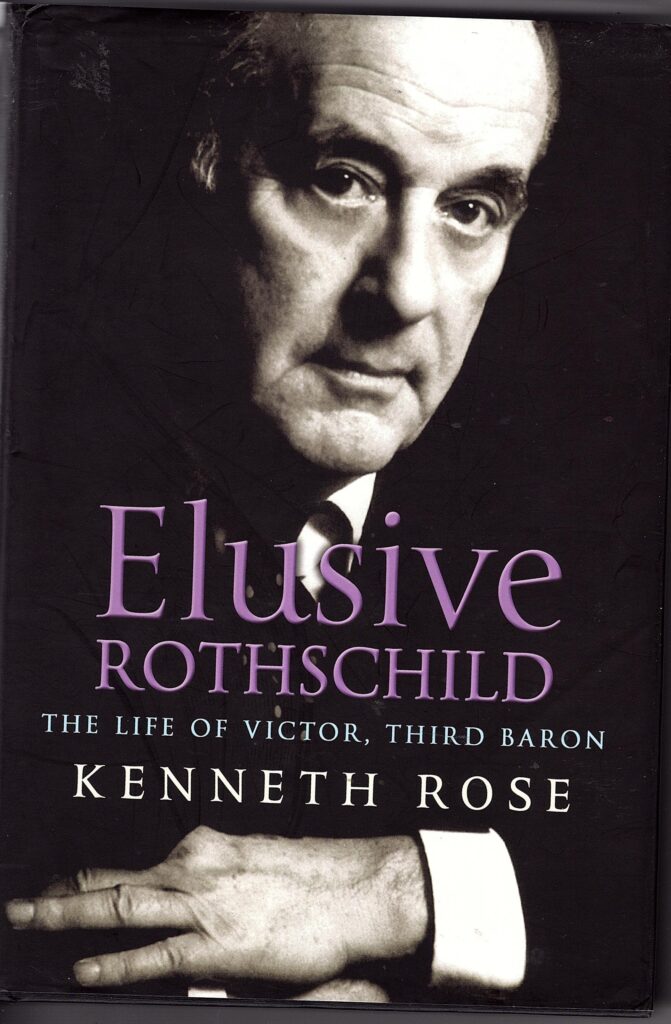

An inspection of Kenneth Rose’s Elusive Rothschild deepened the mystery, however. Charles had apparently been struck with St. Louis encephalitis in 1916, and, on medical advice, left for Switzerland that year, while his wife remained in England to look after their four children. Charles returned to Tring, but he was not cured. After a few years of depression and debility, he gave up the struggle in 1923. (I discovered I had a copy of Frederic Morton’s 1962 history of the Rothschild family, The Rothschilds,in my library. All it says of Charles (‘Nathaniel’), ‘a gifted natural historian’, is: “Conscientiously but unhappily, he performed his duties at the bank until his suicide in 1923.”) Charles had an older brother, however, named Walter, who retreated from reality in a different way. His heart was also not in banking, but in zoology (as was Victor’s). He was forced to sit at a desk at Rothschild’s during the week, but he loathed it. And he led an unconventional life. As Rose puts it, exploiting Miriam Rothschild’s biography of him: “For years . . . his emotional life had been of labyrinthine disorder. Two mistresses, by one of whom he had a child, fought each other for his favours. A third, a peeress, systematically blackmailed him for thirty years by threatening to tell his strait-laced mother of their defunct liaison. Only Lady Rothschild’s death in 1935, two years before his own, defused that aristocratic conspiracy.” Walter sounds a much more likely candidate – but he was definitely not a banker.

Venetia was not a peeress, either – merely the daughter of a baron. Edwin Montagu was also a son of a baron, Lord Swaythling, and thus brought no elevated nobility to his wife. Strangely, he was also judged to have died from encephalitis. Venetia bore a daughter in 1923, Judith Venetia, but her Wikipedia entry states that Judith’s father ‘was said’ (that weaselly anonymous expression) to have been ‘William Humble Eric Ward, then Viscount Ednam and later 3rd Earl of Dudley’. What these aristocrats got up to! Were ‘they’ correct about Viscount Ednam, or had the father in fact been Walter – from whom Victor inherited the baronetcy in 1937? As Miriam Rothschild writes in her biography: “Walter’s irreverent nieces remarked that it was a wise man who knew which Rothschild was his own father . . .”.

Yet I soon found that there were connections between Victor and Venetia. When Venetia eventually married Edwin Montagu in 1915, she had to convert to Judaism so that Montagu could keep his inheritance. This was an exact forerunner of what Victor’s first wife had to undertake to become accepted by the Rothschilds. Moreover, the files on the Rothschilds at the National Archives show that Victor and Venetia socialized, possibly through their acquaintance with another Cambridge scientist named William Grey Walter.

In the extensive follow-ups to the defections of Burgess and Maclean, when Victor was dribbling names of leftist Cantabrigians from the thirties to his MI5 interviewers, Walter’s name came up, on February 16, 1966. Evelyn McBarnet (D1, who appeared to be leading Peter Wright in the exercise) reported that Rothschild had recalled four more names since their last meeting: Mickie Burn, Harry Collier, Grey Walter and a man named Katz. (McBarnet noted that this was a very disingenuous offering by Rothschild.) Rothschild described Walter in somewhat alarming terms:

A very beautiful young man whom he thought of as a queer fish. He recalled that on one occasion when visiting a certain Venetia MONTAGU, a much older woman with whom Grey WALTER was closely associated, he had met MACLEAN staying at her house.

Walter had a file already, PF 765553, so he was therefore known to MI5, but McBarnet did not then pursue the inquiry. Why Rothschild would choose to describe Walter in that way (his pretty looks did not survive into middle-age, it would appear) is bizarre, but the veiled hint is that Walter, who was born in the same year as Rothschild, was having an affair with Venetia. The implication was perhaps that Walter was tarnished in some way by the Maclean connection. But why was Rothschild visiting Venetia? Was Walter having an affair with her then? If Rothschild knew Walter well, why would he complicate matters by introducing Venetia?

MI5 followed up later – much later. On August 26, 1969, an officer (whose name for some strange reason has been redacted) interviewed Walter at his office in the Burden Neurological Institute in Bristol. The archived note does refer to an earlier discussion from August 4, and the interviewer sought clarity on something Walter had said about Guy Burgess. He wanted to know the date of a holiday that he had spent at Rothschild’s villa in Cap Ferrat, and who besides Burgess had been in attendance. Walter fumbled a bit: he thought it had happened before he was married, but he could not recall the exact date of the latter event. He concluded the visit was probably in 1932. (A note on the file says that Walter married his first wife, Katherine Monica Ratcliffe, in 1933. They divorced in 1945.) Walter then adds that the other attendees were Mary Rothschild, Venetia Montague [sic] and her small daughter, Anthony Blunt, and an auctioneer whose name he could not remember. I can find no trace of a ‘Mary Rothschild’ in the comprehensive Rothschild family tree which appears as an endpaper in Morton’s book: nor does Miriam Rothschild show one in the tree she provides with her biography of Walter. Did Victor perhaps present ‘Mary’ as some kind of relative? How did Walter misremember this person? Why did MI5 not follow up?

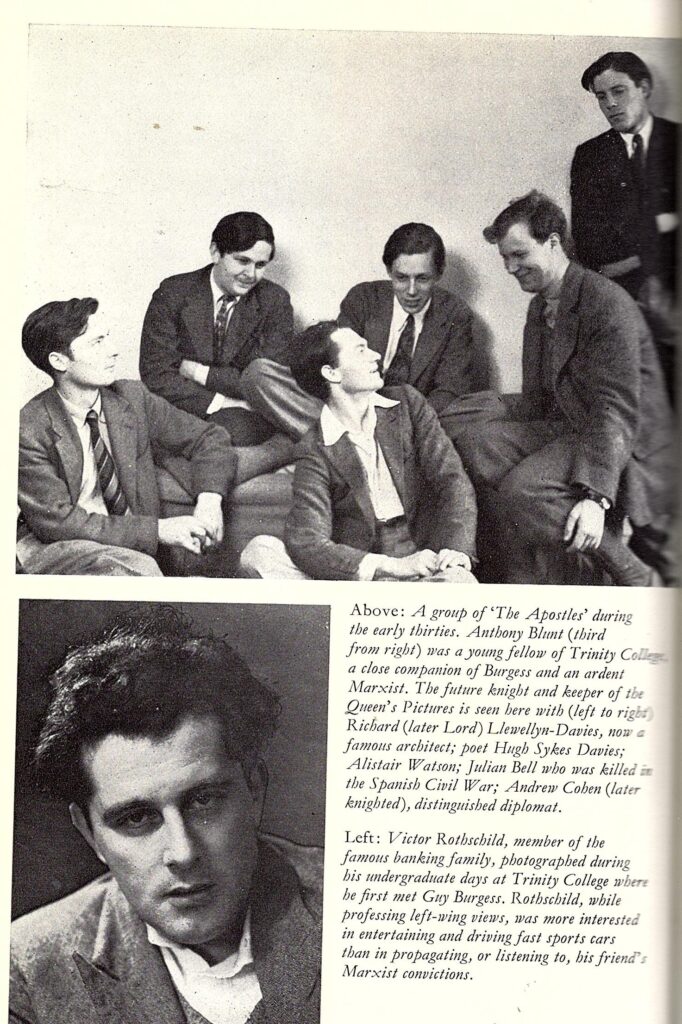

The report from the August 4 session is also perplexing. Grey Walter claimed that he had been Victor’s supervisor at Cambridge, which can hardly make sense, given that he was about six months older than Rothschild. He then expanded on his relationship, stating that he recalled attending parties at Llewelyn-Davies’s house in London after meetings of the Apostles. The report goes on: “The last, he thought, was about 1943, which, together with a lot of people he did not know, the following attended: Blunt, Burgess, Chesterman, Victor Rothschild, Alister Watson. . .”. He also expressed the opinion that it was paradoxical that a man of Rothschild’s wealth should join the Labour Party. Perhaps he might have wondered in that case why Rothschild had remained an Apostle, and had continued to mix with such a subversive lot.

So why was Victor friendly with Venetia, and inviting her (and her daughter) to his villa? Was it part of an obligation founded in his uncle’s abandonment of her? And did he introduce Venetia to Grey, or was the story of their affair all a pretence, to distract from his own entanglements? And what was going on with Burgess, Maclean and Blunt? I am not going to shell out $100 to buy Stefan Buczacki’s My Darling Mr. Asquith: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Venetia Stanley, which might help solve the mystery, but perhaps someone out there in coldspurland can contribute to solving the puzzle. Hallo, Nigel Platts! Hey, Richard Davenport-Hines! Help me out! (Has anyone read Precipice, and thus might be able to tell me if Harris has discovered any useful information?)

Lastly, I should mention that Grey Walter’s elder son was Nicholas Walter, a prominent irritant to the authorities as a civil disobedience activist when I was growing up in the nineteen-sixties – a member of the Committee of 100, and of Spies for Peace. I notice that he also learned Russian while working for Signals Intelligence. His daughter, Natasha, carries on the family tradition, being an ardent feminist, anti-racist and climate activist (‘Extinction Rebellion’). She has also written a novel (A Quiet Life) based on the life of Donald Maclean’s wife Melinda Marling, which I have subsequently acquired. Perhaps being a gadfly is – ahem! – in her DNA. Then I noticed that she had written a memoir about her parents and grandparents, so I thought I ought to read that too, to see what she said about her paternal grandfather.

The book, Before the Light Fades, is primarily an elegy to the author’s mother, Ruth, who committed suicide as her dementia got worse, and Natasha spends a lot of time analyzing her own grief and sense of guilt. (As she admits, she makes ‘heavy weather’ of her grief.) She also describes the growth of the anarchist-protest movement that brought her parents together, and she appears to want to bear all the world’s woes on her shoulders. (You may not be surprised to learn that she is Honorary Professor of Climate Crime and Climate Justice [!] at Queen Mary University, without appearing to bring with her any appropriate qualification in meteorological science. As Dr. Heinz Kiosk constantly reminded us: “We are all guilty!”.) I found the story of her maternal grandfather’s sufferings under Nazism very poignant, but I was not moved by the overlarded lament about her own predicament and conflicts. In fact, I harbour some sympathies with her complaints about the condescending obscurantism and obsessive secrecy of British governmental institutions, but I have no time for persons who selfishly push their case by disrupting the ability of their fellow-citizens to carry on with their lives, and to go about their daily business. Moreover, the author is typically naive about the Soviet threat and influence during the Cold War. She writes nothing about the corresponding noisy protests demanding nuclear disarmament that did not take place in Russia while she and her friends were demonstrating so boisterously in Britain.

The disappointment was that I learned little about her paternal grandparents, since she concentrates on Ruth’s parents, Jewish refugees from Germany. I thus sent her an email (care of her press agent, of course), asking whether she was aware of the snippets in the Rothschild file, and whether she could add any information on her grandfather’s friendships and relationships. I received a very pleasant response from her, in which she revealed that she knew about Grey’s ‘connection with Victor Rothschild and Venetia Montagu’ – which statement implies that Venetia was closer to Victor than Grey was. She added that Venetia had given Grey a silver cigarette-case inscribed with the worlds ‘for services rendered’ – but what those services were is unknown. She said that her father had told her that her grandfather appeared to enjoy his association with the Cambridge spies, but that Nicholas believed that his father was probably not one himself. Apparently, Rothschild treated him poorly, refusing to see his old friend in 1970 after Grey underwent a serious accident. Maybe Rothschild felt awkward about having passed on his name to the authorities. And that was it.

I did read A Quiet Life. It is excellent. Walter’s novel was inspired by the life of Melinda Marling, but it does not attempt to embellish it. Instead, the author has written a very accomplished work of original imagination. Only towards the end, when the denouement of Edward Last’s escape is described, does Natasha Walter falter, as her details too closely mirror the circumstances of Donald Maclean, and a few jarring errors occur.

False Alarms: Sisman, Trevor-Roper and Philby

One of my correspondents, Moshe Evan-Shoshan, contacted me earlier this year to challenge me (very politely) over my treatment of Kim Philby, suggesting that I had downplayed his baleful influence on the course of the war, compared to the other members of the Cambridge Five. He referred me to a passage in Adam Sisman’s biography of Hugh Trevor-Roper, An Honourable Englishman, p 121 (in the USA edition), where the author claimed that Philby (as acting head of Section V of MI6, with Cowgill ‘out of the country’ at the time) had refused to allow a report by Trevor-Roper’s Radio Analysis Bureau (RAB) to be circulated further. The report, exploiting intercepted traffic, had reputedly indicated that the Sicherheitsdienst was encroaching on the work of Admiral Canaris’s Abwehr, pointing to a struggle for power between the Nazi Party and the German General Staff. “It implied that there was an opportunity for the Allies to exploit this widening rift”, wrote Sisman. Stuart Hampshire, representing RAB at the meeting with Philby, was reputedly astonished by Philby’s obduracy. When Trevor-Roper originally wrote about it, this incident had been eagerly picked up by other writers, such as Richard Deacon in The British Connection.

It was apparently not until two decades later that Hampshire and Trevor-Roper concluded that Philby had been carrying out Stalin’s orders, strongly discouraging any ‘dickering’ (as Philby described it in his memoir) with the Germans, as it was not in the Soviet interest to have the western allies colluding in any way with conservative Germans. Yet the strange thing about Sisman’s narrative here is that he provides no sources for any of his facts – neither the identity of the ‘Canaris and Himmler’ report, written by Hampshire in November 1942, nor its contents, nor the record of the meeting between Hampshire and Philby, nor the statement claimed to have been made by Hampshire immediately afterwards that ‘there was something wrong about Philby’. I dug around, and found that Edward Harrison, in his Foreword to Trevor-Roper’s Secret World, had identified the repository of the report as being HW 19/347 at the National Archives. So I turned to my London-based researcher, and asked him to photograph it: a couple of weeks later I received the package. I was at that time, however, consumed with other projects and distractions, and unable to give it any focussed attention for a while.

At about the same time, in April of this year, the Journal of Intelligence History published on-line an article by Renate Atkins and Brian Cuddy titled ‘The German opposition question in British World War II strategy: interpreting Hugh Trevor-Roger’s wartime intelligence reporting’. Moshe and I examined it. The authors were similarly puzzled. They had also located the ‘Canaris and Himmler’ report in HW 19/347, but they pointed out that it had a date of June 5, 1943. Sisman knew about this file, as he provides an Endnote to a report written in August by RIS (Radio Intelligence Service, the successor to RAB) titled ‘Abwehr Incompetence’, but all he writes about the puzzle is that the ‘Canaris and Himmler’ report was issued ‘in a bowdlerized form’ in June. That event occurred soon after Trevor-Roper had escaped a reprimand from Valentine Vivian, and been appointed the head of the new group, RIS, reporting directly to Menzies. (Sisman does not state who told him that it had been ‘bowdlerized’, or who had carried out such revisions.) On the other hand, Atkins and Cuddy, in their Footnote 27, gently undermine Sisman’s judgment concerning the virility of the struggle, pointing out that that opinion is not expressed in any of the three points that constitute the report’s conclusion, and that no recommendation for Allied intervention was made. They add that other scholars, such as P. R. J. Winter, who has written about the bomb plot against Hitler, have unwisely accepted unquestioningly what Sisman wrote, and they conclude that Trevor-Roper may have undergone an ‘embellished recollection’ when he wrote about the events in 1968. Yet Atkins and Cuddy do not express any scepticism about the claim that the earlier version of the report did exist.

An inspection of the file shows that the report, offered with Hampshire’s initials, and a date of June 5, 1943, could hardly be considered controversial. Its main conclusion is that Himmler’s Sicherheitsdienst was indeed intruding on the territory of the Abwehr, and that Canaris was therefore emphasizing tactical operational intelligence. Its issuance did provoke some minor debate, with Palmer, from Hut 18 at GC&CS, disputing some of the evidence. That prompted a partial climb-down from Trevor-Roper, who stressed that the conclusions were indeed tentative. So what happened to that more outspoken earlier version? Sisman writes that Trevor-Roper, frustrated by Philby, had enjoyed a meeting, probably in early April 1943, with his ally Lord Cherwell, Churchill’s top scientific adviser, and given him the earlier version of the paper. This news had found its way to Valentine Vivian, the vice-chief of MI6, who demanded, in a meeting with Menzies, that Trevor-Roper be fired for bypassing the proper channels. Trevor-Roper managed to defend himself, and even gained his promotion after the incident.

Yet, again, Sisman provides no source for the events apart from Guy Liddell’s diary, since Trevor-Roper had looked for sympathy from his friend at MI5 when his ideas kept being rejected. As it happens, Liddell wrote admiringly of Trevor-Roper’s report in his June 19 entry, quoting large chunks of it – but he expressed no knowledge of the earlier ‘unbowdlerized’ version. Sisman did not start work on his biography until after Trevor-Roper’s death: he had access to diaries and other papers, but he refrains from citing them in reference to these episodes, so it is impossible to verify the claims he makes. The description of the events in the summer of 1943 sounds realistic, but what about the skirmish with Philby the previous year? Trevor-Roper was not present. Did Sisman rely on the testimony of that very dubious character Stuart Hampshire? And was Hampshire embellishing his description of the Philby meeting as a way of bolstering his anti-communist credentials, and highlighting his good nose for spies? After all, what Philby stated about not wanting to circulate the paper would have harmonized well with what Churchill himself had instructed about not negotiating with any Germans, as Sisman himself acknowledges on page 122. Philby would have had the support of Cowgill, Vivian, and Menzies.

Another sub-plot was carrying on at this time, however. Sisman describes how Trevor-Roper, frustrated by the excessive secrecy and territorialism of his new boss, Cowgill, had contacted Cherwell on December 17, 1942, seeking his help in finding him a new job. He had been feuding with Cowgill for over a year. This was just a month after the supposed creation of the elusive first folio of the ‘Canaris and Himmler’ report. Sisman does not tell us what Cherwell’s response was, but it seems rather anomalous that Trevor-Roper would not have discussed with him then the essence of his controversial findings, and the regrettably undated contretemps between Hampshire and Philby, but instead have waited until April the next year to ‘mention casually’ to his mentor the fact that his unit had detected ‘signs of a power struggle’ in Germany, and passed him a copy of his report only then.

Elsewhere, Trevor-Roper wrote equivocally about his dealings with Philby. In his book The Philby Affair (the first chapter of which, rather confusingly, is also titled The Philby Affair), he provides two passages concerning these events. The first, in The New Machiavel, describing his summons to the meeting with Vivian and Menzies, runs as follows:

I was, I fear, distrusted by our superiors, who suspected me, with some justice, of irreverent thoughts and dangerous contacts. I was secretly denounced as being probably in touch with the Germans, and more openly – and more justly – accused of consorting with the more immediate enemy, M.I.5. I was once summoned to be dismissed.

Here, however, he does not single out Philby as being the prime agent of the accusations, or of behaving obstinately. Indeed, Trevor-Roper did not report to Philby, but to Cowgill (his immediate ‘superior’). The accusation of ‘being in touch with the Germans’ does, however, suggest a stronger liaison/sympathy than the eventual paper expressed, but Trevor-Roper’s failure to attribute to Philby the dramatic action which Hampshire described is a bizarre oversight.

A second passage (which is cited by Atkins and Cuddy, and of which Moshe carefully reminded me) appears in the chapter An Imperfect Organisation. Now Trevor-Roper is highly specific about Philby’s obstructiveness, and I reproduce the vital passage:

Late in 1942, my office had come to certain conclusions – which time proved to be correct – about the struggle between the Nazi Party and the German General Staff, as it was being fought out in the field of secret intelligence. The German Secret Service (the Abwehr) and its leader, Admiral Canaris, were suspected by the Party not only of inefficiency but also of disloyalty, and attempts were being made by Himmler to oust the Admiral and to take over his whole organization. Admiral Canaris himself, at that time, was making repeated journeys to Spain and had indicated a willingness to treat with us: he would even welcome a meeting with his opposite number, ‘C’. These conclusions were duly formulated and the final document was submitted to security clearance to Philby. Philby absolutely forbade its circulation, insisting that it was ‘mere speculation’.

I noted a few things about this passage. Nowhere does Trevor-Roper state that his report made a call for high-level action, as asserted by Sisman, or that the information, in Sisman’s words, ‘implied that there was an opportunity for the Allies to exploit the widening rift’. He does not explain why the report had to be approved by Philby: he says nothing about Cowgill’s absence. (I cannot even find evidence that Philby was officially Cowgill’s deputy at the time.) Philby was a junior officer who had been with MI6 for just over a year. How could he be expected to voice an opinion on behalf of Menzies, when the Chief was explicitly named in the report? Even if he had been deputizing for Cowgill, would he not have pushed the issue upstairs, rather than making a rash and very revealing decision on his own?

Moreover, Trevor-Roper is sophistical about his citing of Philby’s comments about ‘dickering with Germans’. Philby made these in the context of the state of the war at the end of 1943, not at the beginning. Philby himself writes that it was then clear ‘that the Axis was heading for defeat’. For Trevor-Roper to link his probably imaginary report of late 1942, and Philby’s apparent rejection of it, with the emerging dissentient voices in Germany a year later, is deceitful and unworthy. Neither Trevor-Roper nor Hampshire nor Philby was in a position to exert any influence on strategy, and the historian’s posturing looks like a piece of grandstanding, trying to show his moral superiority at the time, but also suggesting that he was outwitted by the evil Phiby.

Then other questions occurred to me. If Trevor-Roper had indeed stepped too far in interpreting intercepts, and recommending action, how come that Menzies (who needed to keep in favour with Churchill) had so swiftly accepted his arguments, and promoted him after the tense meeting with Vivian and Menzies? And why, if Cherwell had received a copy of the original RAB report, had it not surfaced in the Cherwell archive – perhaps with some indication of the action he took? Moreover, in the light of Trevor-Roper’s appeal to Cherwell in mid-December 1942, had the celebrated historian perhaps behaved especially provocatively in order to try to be transferred somewhere else? And why was Guy Liddell seemingly unaware of the earlier version of the report that got Trevor-Roper into so much trouble? Unfortunately, the historians involved here do not help much. Trevor-Roper’s Wartime Notebooks (edited by Richard Davenport-Hines) say nothing about the business. (It appears that the diaries have not been abridged.) Sisman uses Cherwell’s papers less intensely than does Edward Harrison, who, in Secret World engages in deep analysis of the disagreements between Trevor-Roper and Palmer, but studiously avoids any coverage of the genesis of the ‘Canaris and Himmler’ paper, or the resulting controversy.

I dug around a bit more. Guy Liddell’s Diaries were very revealing. They show that, in the winter of 1942-43, Liddell, as the chief of counter-espionage (B Division) at MI5, paid regular visits to St Albans for meetings of the RSS Committee, where Section V was based at the time: Trevor-Roper worked out of nearby Arkley, but reported to Cowgill of Section V. Thus Liddell kept in close contact with other Committee members, and was involved with the disputes over sharing ULTRA intelligence. Moreover, Cowgill was clearly present at the weekly RSS Committee meeting on December 3, 1942, at which everybody except Cowgill and Maltby voted not to dissolve the Committee. My records show that it was in early December 1941 (not 1942) when Cowgill and Montagu went to New York to help Stephenson with Double-Cross activities. It is highly unlikely that Cowgill would have left the country at such a critical period for the Committee – certainly for any length of time that meant he had to appoint someone to deputize for him. On January 7, 1943, Liddell and White discussed Cowgill’s behavior with Vivian, and Vivian had to admit that Cowgill’s perceptions were narrow.

I had also been surprised by Liddell’s reaction to the July version of the report, since his comments clearly tell (unless he was being massively deceptive) that this was the first time he had seen it – whether bowdlerized or not. His knowledge at the time would appear to be confirmed by another diary entry. On January 17, 1943, he comments on intelligence gained from Abwehr POWs about the incursions of the Sicherheitsdienst into Abwehr affairs, but Liddell makes no reference to any earlier RAB conclusions. Since he was in constant communication with Trevor-Roper (the contact that Vivian so strongly deprecated), it would be astonishing if the case of the inflammatory report had not been described to him by his friend.

Moreover, Liddell had known about Canaris’s dubious loyalty for some time. In his diary entry for November 12, 1940, he refers to testimony that the Soviet defector Walter Krivitsky had given MI5 the previous January, namely the suggestion that Canaris was in Russian pay. (This item does not appear in the official report, but Liddell had enjoyed private sessions with Krivitsky.) Liddell even suggests a possible meeting in Portugal, and he indicates that he has recommended to Valentine Vivian that they should ‘try to get at’ Canaris. Over a year later, on January 7, 1942, he makes the astonishing observation that the Times has reported that Canaris ‘is intriguing with Gen. Marschner for the overthrow of the Nazi regime’. Thus intelligence of rifts in the German ranks and specifically of Canaris as a rebel, that, according to Sisman’s allegations, was gathered by Trevor-Roper, was hardly news, and was even in the public sphere. Trevor-Roper may well have been echoing received wisdom within MI6 when referring to the possibilities of a rendezvous in Portugal.

The obvious answer was to contact Sisman, and to ask him why he had published such claims with so flimsy material to back him up. Accordingly, I sent to his agent (no direct email access to Mr. S. being available, as he is an important man) on August 8, a ten-point questionnaire, preceded by a suitable introduction. It ran as follows:

* Who was the source of this story?

* Have you seen the original RAB report?

* Where may the report be found/inspected?

* How do you know that it was later bowdlerized?

* What changes were made to Hampshire’s original draft?

* Where is the evidence that Trevor-Roper sent Hampshire to St. Albans to discuss it?

* What evidence is there that Philby refused to allow its circulation?

* Did Hampshire write up the outcome of his meeting with Philby?

* Where did Hampshire record his statement that ‘there was something wrong with Philby’?

* Who were the other RAB officers who were ‘baffled by Philby’s obduracy’?

I should greatly appreciate any other information you can give me on this puzzling incident.

I never received any acknowledgment from Sisman, let alone a response. He has thus been added to my ‘List’. I wonder whether he is embarrassed by what he wrote: he should be.

Thus the claim that Philby may have helped to frustrate a rebellion and coup against the Nazis lies on very shaky ground. Philby’s probably mendacious boast is not backed up by any other evidence. The story of Hampshire’s indignation, and of Trevor-Roper’s frustration, is supported by no archival evidence, not even a confidently attributed conversation. Cowgill was around in November to process the report himself. Any relevant exchanges between Trevor-Roper and Cherwell remain elusive. The true cause of Trevor-Roper’s summons by Vivian and Menzies cannot be determined. The so-called ‘unbowdlerized’ report has not been located. Guy Liddell did not appear to be aware of its existence. I cannot identify any reference by Stuart Hampshire to the incident. Moreover, if Philby had obstructed a report that encouraged Britain to interfere in a potential conflict between the Nazi Party and the General Staff, he was only expressing a policy that emanated from Churchill and was passed through Menzies, Vivian and Cowgill to him.

As with so many incidents, we outsiders should be very wary of trusting what so-called ‘experts’ write on intelligence matters, whose authority relies solely on the fact that they have developed a certain reputation. If their unsupported pronouncements go unchallenged, they frequently become cast in stone, are cited and reinforced in other works, and thus become very difficult to dismantle. (I explored this problem seven years ago, in Officially Unreliable, at https://coldspur.com/officially-unreliable/, but the defect is not restricted to authorized histories.) Historical figures, irrespective of their reputation, tend to embellish their own achievements, and biographers should be very cautious before accepting such claims. Sisman has been shown to be a very slippery and imprecise chronicler, and his subject, Trevor-Roper, turns out not to be the completely ‘Honourable’ Englishman that Sisman dubbed him.

‘The Airmen Who Died Twice’

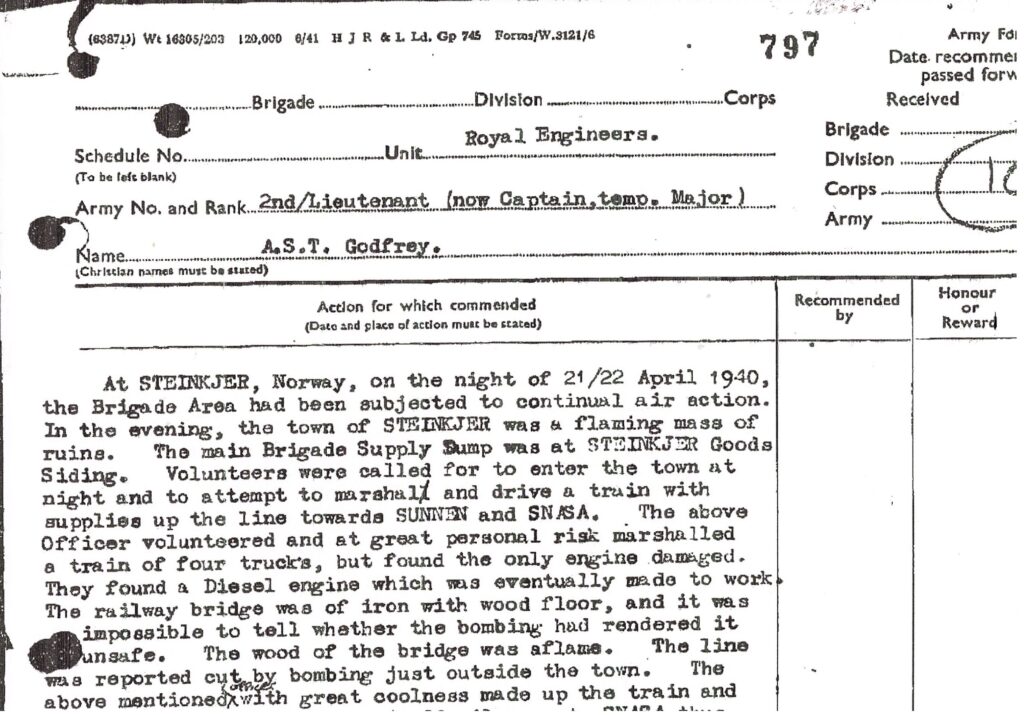

I must confess to an enormous amount of disappointment that my researches into the crash of Flight PB416 did not result in any recognition by the authorities (Squadron 617, the Foreign and Colonial Office) that the disaster was the result of an incredibly stupid decision that turned fatally wrong. My dismay was intensified by the fact that it was the official historian at the F&CO who had put me on to the Crash Report where I discovered the shattering but embarrassing facts about the subsequent investigation which confirmed my theories. I posted my analysis of the file well in time before the eightieth anniversary of the event, but it was sadly ignored. I had imagined that the British Embassy in Norway would be participating in a commemoration service at the church in Nesbyen, as they had done ten years ago, but its representative informed me that they had not been invited to any such event.

I feel that I have been let down by several persons – not just the obtuse ‘historians’ at the 617 Squadron Association and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, but also by reporters in the national media, whose invitations for stories were clearly bogus, as the newspapers did not even acknowledge my emails. I failed to gain any response from more independent reporters who should have had a professional interest in what I wrote, and there even ‘friends’ I had acquired through coldspur who made promises, but turned out to be utterly useless. And the person who started the whole project off has turned out to be an empty vessel, and has done nothing detectable to promote my story in the UK. It is all quite astonishing, as my ‘conspiracy theory’ offers much substance, and a good deal of hard evidence, and I repeat my suspicion that some kind of celestial D-Notice may have closed out any discussion.

In late September, I noticed on Facebook that the 617 Squadron Society had posted a story, with photographs, reporting that the ‘Nes’ [presumably ‘Nesbyen’] Historical Society had held a ceremony at the crash site in September, and it offered photographs of those attending, including the mayor of Nesbyen. I immediately posted a message of support, recognition, and thanks, and provided a link to my analysis of the Crash Report. By the end of the month, fifty-three persons had indicated their approval of the ceremony: none had showed any appreciation of my message, which is prominently displayed. Is that not weird? I then dug out the email address of the mayor from the Web, and sent her a message explaining the history, and providing a link to my analysis. I never heard back from her.

I believe that a strange dynamic is at work here. I detect a very strong interest from amateur historians and aficionados in the fortunes of WWII frontline soldiers, airmen, seamen and agents – especially those who lost their lives in a good cause. Much of this derives from an appreciation of their heroism in confronting dangerous odds, and sometimes having to undergo unspeakable cruelty. I believe that a continuing remembrance of what they went through is admirable, and I have shown my support in my attention to the victims in F Section of SOE, and to the unfortunate casualties from Flight PB416 of the ‘Dambusters’ squadron.

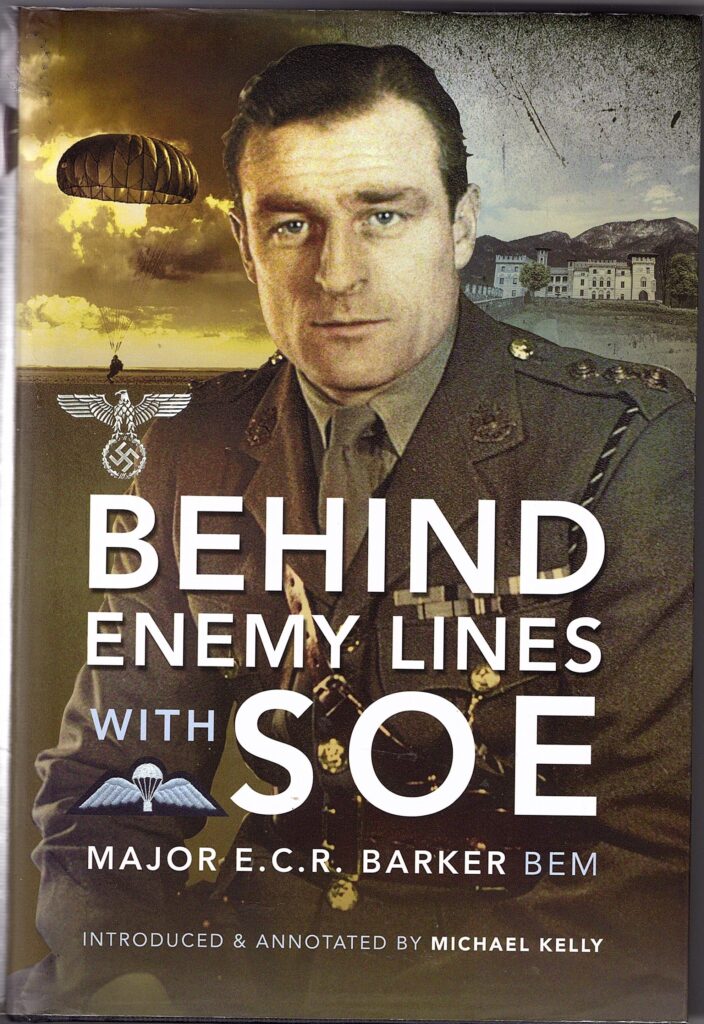

Yet such concerns display all too often a sentimental and unrealistic side. Many books are written about the failed operations in which these heroes and heroines took part, and many of them are not very well put together. I have learned, from some of the chat-sites on the Web, that the mere publication of a book is an occasion for intense excitement and congratulations, irrespective of its quality. There are a few excellent authors out there, such as Clare Mulley and Stephen Tyas: on the other hand, too many clunkers are published. I recently read one, titled Behind Enemy Lines with SOE, based on the memoirs of Major E. C. R. Barker, introduced and annotated by Michael Kelly. It is a clumsily compiled work, and poorly edited. It is an account of Barker’s participation in Operation Arundel of the CLOWDER mission in the Balkans, which took place in the autumn of 1944. As the flyleaf describes: “The team’s brief was to find safe routes into Austria and infiltrate agents in order to encourage resistance against the Nazis.” It carries the obligatory blurb from Nigel West: “At last a brave officer on a clandestine assignment in the Balkans receives the recognition he deserves”.

This was, however, a foolhardy mission, conceived with poor intelligence, and launched without sensible logistic support. It should never have been undertaken. Yet to suggest that some of these schemes dreamed up in London were hare-brained frequently touches a nerve of those who are very reluctant to accept that the adventures of their relatives and heroes might all have been in vain. (Barker actually survived the CLOWDER operation, although Hesketh Pritchard, about whom I have written, did not.) Such persons can become very defensive about the units (SOE, Squadron 617, Bomber Command, etc.) for which the subjects of their attentions served. The epitome of this syndrome is Francis Suttill, Jr., who, naturally holding a life-long grief about the death of his father in the collapse of the PROSPER network, cannot face the facts about its betrayal and his father’s subsequent execution, as it would depreciate the sacrifice that he made. It is as if a criticism of the Gubbinses, Wilkinsons, Buckmasters, Harrises – all looking out carefully for the medals to be awarded to them – implies a criticism of the agents and airmen they sent out, many on doomed missions. As an antidote to some of the romanticism depicted in books about such exploits, I recommend Jim Auton’s bitter, but balanced, account of his aerial experiences, mostly in eastern Europe, titled The Secret Betrayal of Britain’s Wartime Allies.

I cannot help feeling that the lack of interest in my findings displayed in The Airmen Who Died Twice is largely explained by the same reluctance. The doubters would rather believe that the crash was a sad accident, an incident in which an airplane went off-course in a storm, rather than the outcome of a cruel and desperate project, devised by Churchill in a desire to appease Stalin, which could have enjoyed no satisfactory outcome whatever. It is, of course, complemented by the desires of the authorities I named earlier to bury any theories that might provoke very awkward questions as to why they had ignored the facts for so long.

An Update on the Blunt Confession

I have on this site occasionally referred to the startling discoveries of archival items that suddenly vindicate my previously tentative judgments, or break open startling new research avenues. These include – but are not limited to – the note on Burgess’s contacts with the Comintern, the letter to Len Beurton from SIS in Geneva, the reference to Francis Suttill’s two visits to France in 1943, the report by Jane Archer on Philby, the admission by Guy Liddell that George Hill’s cipher clerk with the SOE in Moscow, George Graham, was actually a Russian born as Serge Leontieff, and the reference to two Russians in the PB416 crash report. I now draw attention to a recent revelation, which might have been overlooked by some readers when it appeared in the September coldspur.

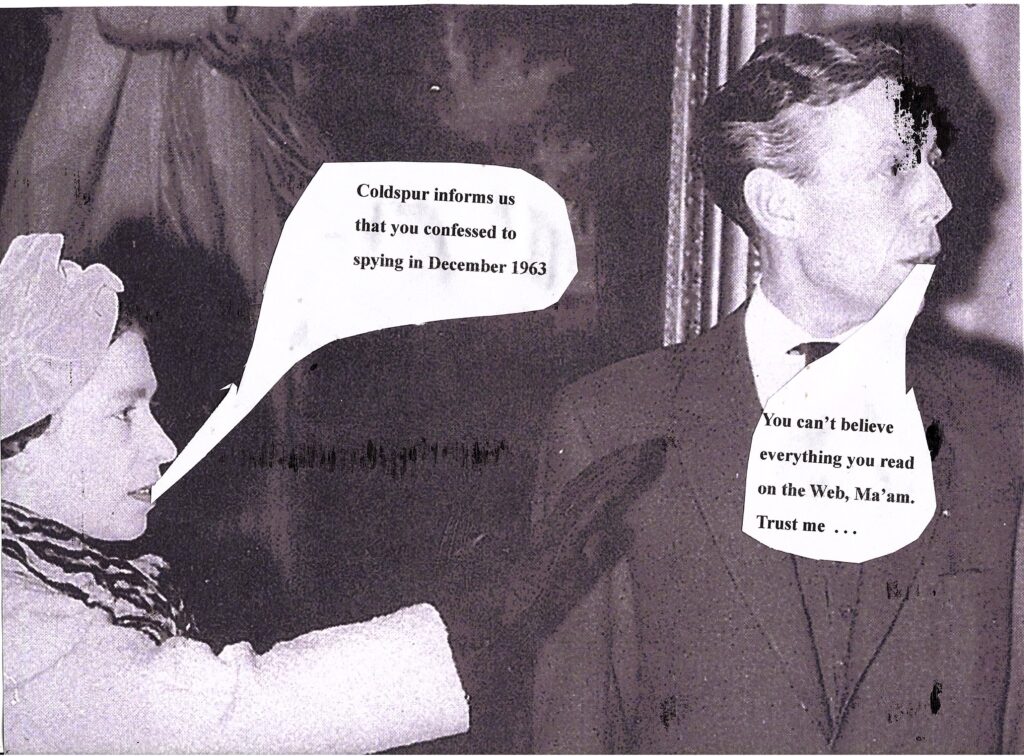

Readers are no doubt familiar with the story of Blunt’s ‘confession’. Andrew described it on page 437 of Defending the Realm, and accounts since have emphasized that MI5 sought the permission of the Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions and the Attorney-General before approaching Blunt on April 23, 1964. The Cabinet Secretary, Sir John Hunt, described the episode thus to Prime Minister Jim Callaghan in December 1978, and his successor, Sir Robert Armstrong, wrote similarly to Margaret Thatcher in November 1979. Thatcher’s statement to the House of Commons on November 15, 1979, spelled out that the Attorney General concluded that ‘the public interest lay in trying to secure a confession from Blunt’, which duly occurred in that April of 1964, and she echoed the claim that new information had arrived earlier in 1964 (when the revelations from Straight had in fact been received the previous summer).

I debunked this account in my two pieces in January and February 2021, titled ‘The Hoax of the Blunt Confession’. My reasoning was primarily as follows: 1) Michael Straight had admitted, in the early summer of 1963, that Blunt had recruited him at Cambridge; 2) Roger Hollis visited the FBI soon afterwards; 3) Straight came to Britain that October, and had meetings with Blunt and with MI5; 4) John Cairncross, whom Blunt shopped, ‘confessed’ to Arthur Martin on American soil in February 1964; 5) the very stagey confrontation with Blunt, described in very melodramatic (and conflicting) terms, did not officially take place until April. My conclusion was that the deal had taken place in December 1963, and that Blunt had accepted the offer of immunity, and (partially) confessed.

[Incidentally, when reading Christopher Andrew’s recently published profile of Cyril Mills, an officer in B1A in MI5, titled The Spy Who Came in from the Circus, I noticed, in a Footnote on page 275, the following laconic text: “In 1963 Blunt had made a brief confession in return for a promise of immunity from prosecution.” 1963? Andrew has always, so far as I know, dated Blunt’s confession to April 1964! Why did he revise his opinion? No source or attribution is given, but I can only assume that the Professor has been reading coldspur, and that he was persuaded by my analysis. In any event, it would be useful for all of us to hear the facts from him.]

Yet, when I wrote those pieces about the Blunt Confession, I rather simplistically assumed that the approval process had also taken place that December, before the actual interrogation that gained the result that MI5 wanted. A couple of months ago, however, I stumbled upon another minute written by Sir John Hunt, this time to Harold Wilson, dated July 3, 1974. Here he wrote: “Following his [i.e. Blunt’s] confession, the case was referred to the Attorney General of the day, Sir John Hobson, who decided that the public interest lay against prosecution.” It was obvious from this that MI5 had forged the immunity deal when it lacked the authority to do so, and that the officials properly responsible had been informed after the fact. Hobson had to decide whether they should honour MI5’s clumsy initiative, or whether they should indeed prosecute Blunt, and explain to him that the offer had been made fraudulently. The authorities (presumably Prime Minister Douglas-Home – although he later claimed to have been uninformed – Cabinet Secretary Sir Burke Trend, Home Secretary Henry Brooke, and the Attorney-General) chose the safer course. And thus the myth was promulgated.

Cabinet Secretary Sir John Hunt

Gave the game away about Blunt.

In a careless memo he conveyed

That the ‘confession’ was all a charade.

One important aspect of the deal is the legal wording that protected Blunt. In Thatcher’s statement she refers only to ‘the offer of immunity’, i.e. without a guarantee that the fact of his espionage would not be disclosed by the government. In the Epilogue that Andrew Boyle wrote for the paperback version of The Climate of Treason (in which he very provocatively presented Jim Skardon, not Arthur Martin, as being the successful emissary!), the author described how Thatcher’s Attorney-General, Sir Michael Havers, having studied the documents, felt strongly that Blunt ‘deserved to be shielded from exposure as well as from prosecution’. But Thatcher overruled him. Nothing could have prevented Blunt from being exposed by the media, of course, though that might have entailed a costly libel action. But did the agreement actually spell out the implications of non-prosecution and non-disclosure? I suspect the original, non-authorized, offer was given only orally, and discussed in a collegial fashion after Blunt was faced with the Straight evidence. In any case I can’t imagine Blunt saying: “Oh, I’d better check that with my lawyer before I sign anything”. Moreover, the official version not so smoothly elides over the business of a written document to be signed. If Blunt had been unprepared, would he have not simply rejected the whole idea indignantly, rather than asking Skardon/Martin to show him the paperwork? Any hesitation would have given the game away. It is all very absurd.

While on the subject, I record here another story on Blunt. I read somewhere that T. E. B. Howarth, in his book Cambridge Between Two Wars, which appeared in 1978 (i.e. the year before Blunt was unmasked) had contained broad hints about the identity of the Fourth Man, and I wondered whether his disclosures had helped fuel the Fleet Street rumours. I acquired the book, and noticed that the text on the end flap encouraged such speculation, since Howarth harboured his own suspicions. The author wrote in his Preface (dated 1977) that the hypothetical ‘Fourth Man’ ‘was believed to have recruited [believed by whom? a passive formulation I abhor] Philby, Maclean and Burgess as Soviet spies’, but stated that he doubted whether the truth would come out without access to Soviet sources. Nevertheless, with his suspicions, he added: “Now that the period is being intensely studied, it would not be surprising if more light were soon to be shed on these murky corners. Perhaps a few glimmers may be found in the following pages.”

The most obvious statement would appear to be one found on page 210, where Howarth writes: “In a 1937 compilation of left-wing essays, characteristic of the times, and ironically titled ‘Mind in Chains’, we even find a future Keeper of the Queen’s pictures, Anthony Blunt, then a fellow of Trinity, torturing his critical sensitivity to conform with the new orthodoxy. He quotes Lenin to Clara Zetkin: ‘Every artist . . . has a right to create freely according to his ideals, independent of anything. Only, of course, we Communists cannot stand with our hands folded and let chaos develop in any direction it may. We must guide this process according to plan and form its results.’” The absurd aspect of this public expression is that Blunt, unlike Burgess, Philby and Maclean, made no attempt to conceal his true political opinions, right up to his recruitment by Military Intelligence in 1939. And yet he was the last of the Five to be exposed.

Lastly, my loyal correspondent Andrew Malec encouraged me to watch the 1987 TV movie on Blunt, The Fourth Man. I initially intended to offer a short review here, but its story and origins are so fascinating that I shall dedicate a coldspur bulletin to them. It will appear next month.

Philby the ‘Double Agent’

This one will not go away. Regular readers will be familiar with my disdain for writers who refer to members of the Cambridge Five (most frequently Kim Philby) as ‘double agents’. They were more correctly ‘penetration agents’, initially recruited by the Russian Intelligence Service (a useful term to represent Soviet Military Intelligence, the GRU, and its companion Federal Security Agency, in the guise of the CHEKA, OGPU, NKVD, MGB, MVD, KGB, etc. over the years), who then infiltrated various British offices and intelligence agencies under false pretences, with their undivided loyalty remaining to the Soviet Union. Just because a Soviet agent happened to be employed by a British intelligence organization did not make him or her a ‘double agent’.

A ‘double agent’ is one who is believed by his (or her) new employer to have switched his allegiance from an enemy service to the domestic one, without the initial recruiting agency’s being aware of the change of allegiance. Of course, the representation might be false, and the enemy might actually still control the individual. That is why John Bevan of the London Controlling Section in WWII preferred to refer to the agents working on behalf of the Double Cross System as ‘controlled enemy agents’. That was also a misnomer, however. It was an accurate term only for those agents – e.g. Wulf Schmidt (TATE) – who had been recruited as loyal Nazis before being poached by MI5. Some of the agents were in fact ‘penetration agents’ who had been recruited by the Abwehr while intending all the while to work for the Allies – e.g. Pujol (GARBO) and Popov (TRICYCLE).

Yet the ‘control’ aspect is vitally important. With Schmidt, for example, all his wireless messages were prepared to be transmitted under his name by MI5 officers, and of course he was never let out of the country. If he had been, he surely would have blown the whole operation (in the early days, anyway). On the other hand, part of the ruse with Popov was that he was allowed to meet his Abwehr handler on neutral territory – a sure sign that he was trusted completely by his British mentors. If control could not be ensured, and doubts came to threaten the confidence the institution had in an agent – as happened with Arthur Owens (SNOW), or Eddie Chapman (ZIGZAG) – then that agent had to be dropped. That was a difficult operation, as the enemy might have wondered why the agent had been taken out of service, and perhaps it would have suspected that its negotiations and discussions with the gentleman in question could have been intercepted.

The inevitable conclusion from all this is that the life of a double agent is normally a very perilous one. It demands a great ability for dissimulation, and the commitment to memory of stories and facts supporting each discrete role. The threat of being caught out by the crueller of the two powers will cause immense stress – unless, of course, the person is safely ensconced in a remote house, such as Schmidt, with the work being done on his behalf. Yet, even up to the end of the war, Schmidt feared for his life that the Germans would discover who he was, and how he had allowed himself to be used in the Allied cause. Overall, true ‘double agents’ do not last long (and the disposition of such by the Soviets in World War II tells a very gruesome story.) Their eventual loyalty is solely to their own survival.

I was thus pulled up in my tracks, when reading John Fisher’s 1977 book Burgess and Maclean: A New Look at the Foreign Office Spies, by a brief assertion the author makes, on page 100, when writing about the leakages attributable to HOMER. The passage starts as follows: “Kim Philby, the spy who, all along, had been a double agent, says that he was briefed in London . . . .” What does this mean? It is not written in the context of a careless reference to Philby’s treachery. It follows a serious evaluation where Fisher writes: “In some cases they [counter-espionage officers] are prepared to work with double agents, that is, men who are betraying information to both sides, in the belief that they can feed more false information to the enemy through a double agent than he can feed to them – or alternatively they hope to win over the agent so that he or she will work exclusively for them in the future.”

It sounds as if these nuggets were fed to Fisher by some naive officer in MI6 who truly believed that such a policy would work with Soviet agents, but, more astonishingly, that Philby had actually been cast in that role, and was carrying out such disinformation exercises to his original masters in the belief that the messages would be trusted. But what if the first thing that Philby had done was to inform his NKVD handler that he was under British ‘control’, and that nothing he was passing on to the Soviets should be trusted? I have made the same point about Anthony Blunt, when the historian Michael Howard absurdly claimed in the Times that Blunt was being used for such purposes. And why would Philby submit to such a scheme, since he must have realized that, if ever he were suspected of having switched sides, his remaining days on this earth would have been drastically reduced? If he did consider volunteering such a recusancy to MI6, and agreeing to be ‘turned’, the first thing he would have done would be to contact the NKVD and gain its permission to do so. (One major irony of this whole exploit is that, for a while in 1943, the NKVD deemed that Philby and the rest of the Cambridge Five were indeed under control of British Intelligence and passing on misinformation to the Kremlin.)

And yet this leaker indicates that Philby had been a double agent ‘all along’. Since when? Since Vienna in 1933/34? Since September 1939? Since he was recruited by SOE in 1940? By MI6 in 1941? It is not clear, but it echoes other vague assertions that I have noted in my previous research. (The conundrum implicitly posed by Fisher is irritatingly not addressed, let alone resolved, in his later chapter focused on the ‘Third Man’.) The murkiness of the Vienna days still bemuses me, but I have made a strong case that Philby did indeed offer his services to British Intelligence in September 1939, when, fearful of possible revelations from the coming Krivitsky visit, he used the Nazi-Soviet Pact as a pretext for coming to an ideological volte-face. He thus pretended to have recanted from his former Communist allegiance, and he promised that he and Litzi would now work for the Allied cause.

The continued belief held by many officers in MI6, even after the events of the summer of 1951, and Philby’s recall from Washington, that Kim had been a loyal officer throughout the war, and beyond, would tend to support my theory that he very skillfully effected a change of heart in 1939, deluding the big shots in MI6 and MI5. The problem was that the leaders of British intelligence simply did not understand guile and subterfuge, and certainly did not understand how the intelligence agencies of their enduring antagonist, the Soviet Union, worked. Their first reaction was to pat themselves on the back for the coup of gaining a Communist convert, when they should have been suspicious, sent Philby into exile in the Outer Hebrides, and asked themselves: “How many more might there be out there?”.

So where does that leave Philby’s status? To MI6, he was a counter-espionage officer who had been reformed, and seen the light, after the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, and could be relied upon to pass on disinformation to his former controllers, who had been gulled, and (so they thought) continued to believe misguidedly in the loyalty of their agent. That illusion started to crumble after the Volkov incident of 1945, the embarrassment of the Litzi/Georg Honigmann elopement in 1946, and the association with Burgess in 1950 and 1951, with the ensuing ‘Third Man’ suspicions. In that sense, doubters of his integrity might justifiably have offered the opinion that Philby was some variety of ‘double agent’, working at times for both sides, but one who was not ultimately controlled by MI6. As for the Soviets, they believed they had installed a very capable agent who had hoodwinked British intelligence, until in 1943 they started to harbour doubts about the reliability of the information they were receiving, and considered that Philby might indeed be a creature of British intelligence. For a while they might too have judged that he was a ‘double agent’. (And later, in Moscow, they protected state secrets from him, still not trusting him utterly.)

I can think of no analogous example the other way – of a native German or Soviet citizen recruited by MI6 who confessed to his totalitarian organs his past role as a traitor, and volunteered to work for his national intelligence services in some role – while thinking that he could continue his work as a spy. I maintain that such a person in that situation would more probably have been executed on the spot. It could only happen in Britain, where the Soviet Union was a temporary ally, under a non-totalitarian system, with radically different cultural norms, accompanied by a rather simplistic approach to security by its intelligence services, that such events could be allowed to happen. Meanwhile, these hints about Philby’s transfer of allegiance continue to accumulate, without yet offering any conclusive evidence . . .

In that last respect, a dishonourable thought occurred to me. When Michael Howard wrote that notorious letter to the Times, he might have entertained one of two contrasting beliefs. The first might have been that he was disingenuously offering a cover story for MI5’s lamentable failure to prosecute Anthony Blunt, not seriously believing in the pap he offered to the newspaper. On the other hand, he might have been one of those intelligence officers who had convinced themselves that Philby had been working on behalf of British intelligence since the outbreak of the war, had been helping to pass misinformation on to the Soviets, had included Blunt (and maybe Burgess, too) in his team of fresh loyalists, and that such exercises were actually successful. After all, why was Liddell ‘consulting’ with Burgess and Blunt over the Borodin business unless he devoutly believed that they were reliable assets who would pass on disinformation to the Soviets? Such an idea is so preposterous, it might even have some validity.

Christopher Andrew and the Minor Biographies

Scattered around my shelves are the biographies of minor players in the intelligence world – those of Kitty Harris, Klop Ustinov, ‘Tar’ Robertson, and the like. I had to read them all, because there were bound to be nuggets that appear only within their pages. But many of them are indifferent – and frequently have to be padded out with historical background material since there is not enough to write about the character to fill a book properly. Thus, for the neophyte who seeks an introduction to the hoary old stories (the Cambridge Five, ULTRA, the birth of SOE, the Double-Cross System, Gouzenko, etc. etc.) they can represent an engaging few hours of productive leisure-reading, but I cannot imagine anyone who is unfamiliar with the broad outlines of the canvas wanting to pick up such specialized volumes, unless they are dedicated aficionados like me, or are perhaps members of the extended family of the subject.

I have read at least four such books over the past year: A Faithful Spy: the Life and Times of an MI6 and MI5 Officer, by Jimmy Burns (about Walter Bell: the rather sad ‘Life and Times’ highlights the problem); Spy Runner by Nicholas Reed (a 2020 re-issue of the 2011 memoir of his father, Ronnie Reed); The Spy Who Came in from the Circus, by Christopher Andrew (about Cyril Mills of the circus family: I suppose he actually came in from the circus into the ‘Circus’, namely MI6, of John le Carré); and A Suspicion of Spies – Risks, Secrets and Shadows, by Tim Spicer (about the no doubt ‘legendary’ but elusive figure of Wilfred Dunderdale, who rejoiced in the nickname of ‘Biffy’, at home alongside all those ‘Jumbos’, ‘Busters’, ‘Fruitys’, and ‘Sinbads’). I plan to write in detail about these four books in a coming coldspur bulletin, but wanted to make a few observations now about Andrew’s enterprise, as I found some aspects of its delivery very puzzling.

I can live with that that rather ponderous title: Mills was actually a spy before and after the war, while working in counter-espionage for MI5 during it. Andrew does have to cover, however, for the fact that Mills was not actually involved with many of the events that he describes, reflected in such speculative phrases as: ‘Though only twelve, Cyril Mills cannot fail to have been struck’. . . ; ‘He must have been impressed by Ramsay MacDonald’s acceptance. . . .’; ‘Abrahams must have told Cyril. . . .’; ‘Mills could not fail to have been moved by the speech . . .’; ‘The key intelligence breakthrough, of which Mills was unaware . . .’; and perhaps the most classic of all: ‘Cyril and Mimi . . . were not present on 8 July 1961 . . .’ (at Cliveden, on the day that Ivanov and Profumo first met Christine Keeler), alongside a lot of other more famous names who were curiously absent from the scene that day.

Yet it is the presentation by the author himself that I find bizarre. He offers an absurdly long bibliography (of which no less than seventeen items are by Andrew himself), and in his Footnotes adds a number of personal touches, describing his own interactions. In at least one, however, he refers to himself as ‘Christopher Andrew’ (p 201), instead of ‘the author’, or ‘me’, the more frequent designation. Furthermore, one remarkable passage appears as follows (p 102): “Despite this mess, the somewhat singed and water-damaged files from the First World War and interwar period, saved by Mills and his helpers, were a crucially important source for the history of MI5 published almost half a century later by its official historian, Christopher Andrew.”

Why would the author want to refer to himself in this pompous manner, in the third person, as if the readers have not already been reminded enough of his history of MI5 by now? And why ‘almost half a century later’? He is referring to the fire in Wormwood Scrubs in 1940: Defending the Realm was published seventy years later. How could he commit such an obvious error? Lastly, why would he refer to himself as the ‘official’ historian of MI5 – a mistake reproduced in the inside flap? He was the ‘authorized’ historian – which is quite another category. (He makes the same mistake about Keith Jeffery, described as the ‘official’ historian of MI6.) One wonders: did Andrew really write this book? And did he even read it before it was published?

Borodin: Deception, Defection and Interception

I enjoyed the exercise of researching and writing about N. M. Borodin, the biological spy. It was a change from the regular beat, and I learned a lot in the process. I was happy with the way my piece turned out, with a pattern evolving that allowed a reasonably coherent story to be laid out, while still leaving some unanswered questions. I have made one significant discovery since. Stewart Purvis and Jeff Hulbert, having inspected the Burgess file KV 2/1115 (which I am awaiting from my London-based photographer), wrote in their biography of Burgess (p 287) that, one of the visiting speakers at a joint MI5-MI6 event held at Worcester College in 1949 was ‘a defector from Soviet military intelligence, Nikolai Borodin’. While that description is wrong (and Borodin has no entry in the index), the note in the archive records that Burgess, Rees and Footman were in the forefront of those who attacked Borodin’s credibility after he spoke. It is the brazenness of that onslaught that amazes me, and I believe that it is very significant.

Amazingly, on December 30, I stumbled on a remarkable passage on Borodin, written by Guy Burgess. It was buried deep in one of Petrov’s voluminous files, KV 2/3453. A letter from Moscow, perhaps to Tom Driberg, had been intercepted, dated March 15, 1956, and the passage read as follows:

Of course what you say about PETROV is true – he was ‘paid nark. As far as I can make out, he gave his original information C.O.D. and subsequently added to it – in different and self-contradictory forms in England and America – on the hire-purchase system. They always do – and the Foreign Office and Intelligence services should know that perfectly well. I remember I once stayed for some days at a joint Secret Service-M.I.5 ‘house-party’. One of the visiting lecturers was a Soviet defector, rather like PETROV, called ‘Borodin’. After he had given his talk containing sensational secret revelations about the USSR, he was whisked away. The audience, all of whom, except me, were members of either the Secret Service or M.I.5 and hence people of whatever experience the officers of those strange services do have – even they smelt obtrusive rats in the revelations we had heard. They attacked the organizer of this proto-PETROV. This was an officer of great experience. He sadly admitted that scarcely a word was to be believed, but that it was always the same. People had to invent to earn their keep. He quoted the cases of KRIVITSKY, KRAVCHENKO and others as examples. Had PETROV been about then, no doubt he would have cited him.

The attitude of the officer who was responsible for bringing in Borodin is even more fascinating than that of Burgess himself. I shall have to return to these matters before long.

Yet the immediate aftermath has had its disappointments. Having performed my due diligence, I wanted to return to the letter by Richard Davenport-Hines in the Times Literary Supplement, which seemed more absurd the more I looked at it. I had written a long letter to the journal at the time, but its content represented augmentation rather than refutation, since I had not yet carried out my research. So I re-approached my contact at the TLS at the end of November, inquiring whether the Supplement would consider another letter. Unsurprisingly, he responded that the matter was no longer topical, but he did promise to alert Mr. Davenport-Hines to my piece after I published it a few days later.

I accordingly sent him an email on December 3, giving him the url. Shortly afterwards, I was alerted by academia.edu that someone had recently looked me up on Google, and had found my review of Agent Sonya on the academia website. It also told me that the inquiry had come from Hackney. I didn’t think much about it, until my contact told me that he was working at home, and that he had been blocked from inspecting my piece. Very innocently, I asked him whether he lived in Hackney, and he replied that he did – without asking me how I guessed. When I expressed my frustrations at the way that coldspur was routinely blocked in some parts of the UK, he replied that he did not think that Mr. Davenport-Hines lived in the Peoples’ Republic of Hackney, and he promised to advise one of the periodical’s major reviewers and correspondents of the existence of my article.

I never heard from him again – nor from Davenport-Hines. After a week or so, I inquired of him whether he had heard back, out of courtesy, from Davenport-Hines, noting at the same time that I was not greatly surprised by Davenport-Hines’s studied aloofness, and reluctance to engage with me, but thought that he should have at least responded to my contact. That email was ignored as well. However, on December 16, I received an email message from academia.edu informing me that Richard Davenport-Hines had accessed my review of Agent Sonya . . . Maybe the TLS had prodded him into action? Yet I have heard nothing since.

And then there was Kevin Riehle, an academic with whom I have enjoyed cordial exchanges in the past. He is the author of Soviet Defectors, which focusses on defectors working in intelligence, not trade groups. When an enthusiastic new coldspur reader pointed out to me that Riehle had claimed that Borodin had still been alive in 1979, I immediately emailed Riehle, asking him for the source. Within an hour, he had responded, regretting that he could not recall wherefrom he derived the factoid. I thanked him, and encouraged him to read my article, asking him specifically to comment on my analysis of Davenport-Hines’s text, and my interpretation of the ‘defection’ itself. I never heard back from him.

Regular readers of coldspur will recognize this distressing phenomenon: an established authority declines to engage in debate, or withdraws from it, because of self-importance, a sense of proprietorship, or simply embarrassment – or some combination of the three. I don’t know what happened to scholarship, but it is all very sad. I do not believe that the TLS would have published that letter had it not come from their insider, Davenport-Hines, and they trusted him implicitly. Yet my hunch is that he has been used, in the way that Alan Moorehead, Chapman Pincher and others were exploited for propaganda purposes.

The Biography of Margaret Thatcher

As I reported in October, my reading of To Catch a Spy prompted me to acquire, and read, the massive three-volume biography of Mrs. Thatcher by Charles Moore. I acquired a set (each in a different format) of all 2,500 pages from abebooks, at a cost of about $18, which must have been a bargain. It is a monumental achievement by Moore, who shows utter control of his material, and writes in (almost) impeccable English (even correcting Maggie’s frequent grammatical and syntactical lapses with a careful ‘sic’). I have to confess that I found many chapters stodgy: the negotiations over the Exchange Rate Mechanism left me slightly woozy, and trying to capture exactly what the Westland Helicopter crisis was about resembled attempting to come to grips with the Schleswig-Holstein question. Yet, overall, Moore covers his subject with not completely uncritical sympathy, and shows an amazing familiarity with the highways and byways of political manœuvering in Britain in the 1980s.

It is salutary to consider how alive many of the challenges that Mrs. Thatcher faced in her time in office remain with us (or with those of you in the UK, I should say) today – the threat of striking workers, and the power of the unions; the need for some sort of energy policy (I read about her struggles with Arthur Scargill the same week that I learned that the last coal-fired power plant in the UK was shutting down); the constant debate of how ‘Europe’ should be treated, with Thatcher uniquely recognizing that a steady move to complete political integration would consist in the disappearance of democracy at the national level; the threat from the Soviet Union, and the tentative idea that what replaced it should even become part of NATO; perennial problems with Northern Ireland (then involving terrorism, and the murder of two close friends, Neave and Gow); enduring financial stresses, concerning austerity measures and the attempt to balance the budget and reduce the national debt; the vexing problem of how to privatize organizations that were effectively public monopolies. For a while, Thatcher was even an early advocate in the cause of climate change – until she discovered what a negative effect drastic measures to curtail it would have on the economy, and on shared prosperity (the Reeves-Miliband conflict in all its barest dimensions). It was all very fascinating.

Perhaps the most striking – and controversial – aspect of Moore’s research is his exclusive access to Cabinet and Prime Ministerial files, indicated by his voluminous references to ‘DCCO’ (‘Document Consulted in the Cabinet Office’) – a phenomenon that is apparently restricted to Volume 3. I have commented in depth on the relevance of such to matters of intelligence (see my October report: https://coldspur.com/to-catch-a-spy-actually-no/ ), but my observations extend to all domains of Moore’s research into Margaret Thatcher’s premiership. The lack of attention paid to this disturbing phenomenon is astonishing. (A Google search on ‘DCCO and Moore’ comes up with nothing relevant.) Not only does some dedicated researcher need to catalogue these incidents: the unjust and discriminatory policy should be challenged at the highest level in the cause of the integrity of historiography.

Apart from Moore’s oversight in not discussing the creation of the University of Buckingham, Britain’s first private university which Thatcher supervised and encouraged – one aspect of Moore’s book really irritated me. It is a feature that attracts the attention of some of my coldspur correspondents, namely the use of Footnotes. Endnotes are a necessary component for the serious reader who needs to follow up references, and they do not interrupt the flow of the prose. But Footnotes can be disruptive, and should be minimized, in my opinion. If the incidental observation is important, the author should try to incorporate it into the main text. If it is largely irrelevant, it should be abandoned. And if it is of a repetitive, formulaic nature, it should be relegated to an Appendix.

Moore decided that, each time he introduced a new politician (or, occasionally someone from another sphere), a potted biography of him or her should appear as a Footnote. This information invariably includes the secondary school that he or she attended, and the college or university. And, with the politicians, the entry normally ends up with the date the MP was knighted (they are almost exclusively male), and, for many, when they were elevated to the peerage. I have no idea why the educational establishments are deemed to be of such interest, and it seems that even the less competent of Britain’s political representatives, so long as they hung around long enough, would end up with such awards or ennoblements. It just reminds me how absurd the whole UK Awards and Honours system is. (I have written about this before: see https://coldspur.com/enigma-variations-dennistons-reward/ ) All such entries should have been placed in an Appendix for the benefit of those readers who consider such details important.

And then I read in The Times of November 7 the obituary of Sir John Nott, which summed up the nonsense very well:

He was bitterly disappointed to be awarded only a KCB. Compared to the peerages that Thatcher bestowed on virtually all her former cabinet ministers, as well as many junior ministers, it was matter of comment and seen as a mark of her disapproval. Yet he had been offered and refused a peerage only to regret it and request in vain if the offer could be repeated. In public he said he was glad not to be in the Lords and did not need the £300 allowance.

This was an aspect of Thatcher philosophy – the exaggerated power of patronage – that the very traditionalist Moore did not analyze in his work: nor did he remark upon the Nott incident.

. . . and an aside on awards . . .

Moore’s Footnotes reminded me of my father, a schoolmaster and amateur (in the best sense of the word) historian. He wrote an excellent history of the school at which he was educated and at which he taught for several decades, and he acted as the honorary archivist for most of that time. He was dedicated to local social history and fine arts groups, and he was a frequent speaker at gatherings of such devotees. He thus garnered an enormous amount of respect for his intellect and research. Astute readers may recall that, when I asked Sir Anthony Seldon at my doctoral viva whether he recalled F. H. G. Percy (from his teaching spell at Whitgift), he immediately responded; ‘Oh, that great man!’.

In that vein, a few years before he died, a group of former pupils conspired to recommend him for an award, and put the necessary paperwork together. But when my father discovered what was going on, and that he was going to be recommended for an M.B.E., he declared that he would rather have nothing than be dignified with a medal that was customarily (as he put it) handed out to the Warlingham postmistress for managing the local office for thirty-five years. (This was of course a long time before the Horizon IT debacle.) That reaction may have seemed ungracious to the well-intentioned team who wanted to have his contribution recognized, but I understood his opinion entirely. He knew his own worth, and what he had achieved, he knew that the persons he respected appreciated it as well, and having those three letters after his name, after all that time, would mean nothing. Would he have accepted an O.B.E.? A knighthood? Probably. One of the ironies was that he religiously scanned each announcement of the Queen’s Honours and Awards to ensure that any Old Whitgiftian thus recognized did not escape the notice of the archivist.

I was amused to read John Cleese’s take on the charivari, quoted in Jonathan Margolis’s biography of him:

I’m very proud. With all these bloody silly showbiz awards around nowadays there are really only three left worth having – the CH, the OM and this one [The Queen’s Award for Industry]. I should mop that lot up in a couple of years. I certainly wouldn’t want any old OBE. They’re like school prizedays where you go up and get patted on the head for being a good boy.

And, as a final comment, I quote the irrepressible and ubiquitous Richard Davenport-Hines, from his review of Hugo Vickers’ biography of Clarissa Eden, in Literary Review. He cites the Duke of Wellington complaining to the Countess: “The trouble with the Order of the Garter these days is that it is full of field marshals and people who do their own washing up”.

Michael Holzman, Proletarian

I was surprised to see an advertisement, in the Times Literary Supplement of September 6, for a book by Michael Holzman rather exhaustingly titled Spies and Traitors: Kim Philby, James Angleton and the Friendship and Betrayal that Would Shape MI6, the CIA and the Cold War. It was placed appealingly below Richard Davenport-Hines’s review of To Catch a Spy, and it declared that the volume was ‘available now from all good bookshops’. Well, that ‘available now’ suggested that this was a fresh publication, but I thought ‘from all good bookshops’ was a slogan that went out of fashion a couple of decades ago, when so much book-buying started to take place on the Web. But hadn’t Holzman written a similar book, titled Kim and Jim, which I had rather disparagingly reviewed a couple of years ago? Was this a rewrite?