I recently read Barbara Honigmann’s memoir about her father, Georg, originally published in 2021. (Barbara was the child of Georg and Litzy, née Kohlmann, who had been married to Kim Philby between 1934 and 1946. See https://coldspur.com/litzi-philby-under-the-covers/, https://coldspur.com/kim-philby-always-working-for-sis/, and https://coldspur.com/life-with-the-honigmanns/ for a comprehensive background to his story.) It was a fascinating experience, challenging my facility with the German language, which had lain largely unexercised for more than fifty years. I was pleasantly surprised that I did not have to resort to a dictionary on more than a handful of occasions. The text reflects the German predilection for long, but mostly carefully crafted, sentences containing multiple subordinate clauses (although I was occasionally surprised by the running-on of separate main clauses in a single sentence, without any co-ordinating conjunction). In this report I reproduce key passages from the book, provide my own translations, and offer some commentary on controversial items, and those of particular interest for what they shed on Honigmann’s career. Ms Honigmann’s study relied on both oral and written evidence from her father, as well as communications with other relatives and friends.

P 11 “Außerdem hatte er in Laufe seines Lebens noch viele Geliebte, von denen ich, wie gesagt, manche traf, von manchen nur wusste oder hörte, und von anderen wurde mir erst nach seinem Tod erzählt, dass er nämlich zum Beispiel, als er nach dem Krieg aus England nach Deutschland zurűckgekehrt war, während meine Mutter, die zu dieser Zeit seine Frau war, noch in England darauf wartete, dass er in Berlin eine Wohnung fand, sich dort auch sofort wieder eine Geliebte angschafft hatte.ˮ

Besides, in the course of his life he had several lovers, many of whom, as I said, I met, of many I merely learned of or heard about, while others were described to me only after his death, for instance that he had in fact immediately found a new lover when he returned from England to Germany after the war, at the time that my mother, who was his wife at this time, was still in England, waiting for him to find accommodation in Berlin.

This is an extraordinary statement by Barbara Honigmann, claiming that Litzy was already Georg’s wife when he absconded to Berlin. It directly contradicts what she writes later, and it is amazing that neither she nor her editor picked up the anomaly. Whether Georg carelessly provided such information is, of course, impossible to determine, but the fact that he was not married to Litzy at the time casts a slightly different moral shadow on his romantic affairs, while confirming his reputation as a ladies’ man.

Pp 19-20 “Später in England unterzog er sich einmal ein paar Wochen oder Monate einer psychoanalytischen Kur, wahrscheinlich hatte ihm Ruth, die damals seine Frau war, dazu geraten, denn Georg litt seine ganzes Leben an Depressionen, verstummte and versteinerte dann fűr einige Tage oder Wochen. Das haben alle seine Frauen so erlebt, sie haben es mir so berichtet, Ruth, Litzy, Gisela und Liselotte . . . ˮ

Later in England he once underwent a psychoanalytical course of treatment for a couple of weeks or months: Ruth, who was his wife at the time, probably advised him to do so, for Georg suffered his whole life from depressive attacks, and would lapse into silence or impassiveness for days or weeks at a time. All his wives experienced it, as they let me know, Ruth, Litzy, Gisela and Liselotte.

Gisela was Gisela May, a famous German actress, who married Georg in 1956. They divorced in 1965, after Gisela had an affair in Italy that was particularly painful to Georg. Barbara constantly refers to her simply as ‘die Schauspielerin’, the ‘actress’.

P 20 “Aber auch űber die Analyze bei Winnicott hatte er nur Schlechtes zu berichten und tat diese Seelenkur, die den Theorien und der ärtzlichen Praxis seines Vaters so nah war und der er sich offensichtlich gegen seinen Willen, nur unter dem Druck seiner Frau unterzog, als Unsinn ab, spottete noch jahrelang darűber. Vielleicht haben dieser Spott und die Ablehnung zur Trennung von Ruth beigetragen, die, nachdem sie wie er Journalistin gewesen war, in England noch einmal Medizin studierte, sich auf die Psychiatrie spezialisierte und dann viele Jahre am Charing Cross Hospital in London an der Heilung gestörter and kranker Menschen arbeitete. Im Gegensatz zu Georg konnte sie kein Heil in der politischen Bewegung entdecken, die er später durch Litzy, meine Mutter, in London kennengelernte – den Kommunismus. Georg aber fűhlte sich vom Kommunismus offensichtlich ebenso angezogen wie von Litzy selbst, und der wurde dann zur ‘dritten Sacheʼ des neuen Paares, die sie einige Jahre zusammenhielt.ˮ

Yet he had only bad things to say concerning Winnicott’s analysis of him, abandoned as absurd this therapy, which was so close to the theories and medical practice of his father, and which he had undertaken openly against his desires only because of the influence of his wife, and ridiculed it for years afterwards. Perhaps this scorn and rejection had contributed to his split from Ruth, who, some time after she had become a journalist, like him, specialized in psychiatry, and then worked for many years at Charing Cross Hospital in London, treating mentally ill and sick persons. In contrast to Georg she could find no solace in political agitation, something that he later became acquainted with in London through my mother Litzy – Communism. Georg felt himself attracted by Communism as much as by Litzy herself, and it then became the ‘third person’ in the new couple’s relationship, which kept them together for some years.

Douglas Winnicott was an influential paediatrician and psychoanalyst who apparently had his own psychological problems. The timing of Georg’s intimacy with Litzy is intriguing: this fragment suggests that Georg was indoctrinated into Communism well before he was interned in Canada, where he apparently came under the influence of Leopold Hornik, and that the relationship with Ruth had by then broken down – contrary to the impression that Georg gave to the Home Office when he was seeking his wife’s release in late 1940. Milmo’s report on the PEACH case indicates that Litzy began living with Georg only in 1942, but Philby had declared that the pair were living together when he arrived back from France in the summer of 1940. Thus we can probably safely conclude that Georg and Ruth were indeed estranged by the time the policy of internment was more aggressively pursued in June 1940, and that serious differences over Communism had contributed to their disaffection. Ruth became a loyal British subject, married Henry Blunden (or Blumenthal) in January 1946, and lived in the United Kingdom for the rest of her life. She died on December 5, 1984.

P 23 “Es war noch vor dem Bau der Mauer, und so fuhren sie einfach los und verbrachten ihre Ferien in ihrer verlorenen Heimat und zeigten sich gegenseitig die Orte, wo sie Kinder gewesen waren.ˮ [Die Schauspielerin]

It was still before the construction of the Wall, and they [Georg and Gisela] were able simply to go away and spend their holidays in their lost home, and they showed each other the places where they had grown up as kids.

The Berlin Wall was built in August 1961, and transit to the West was possible before then. Clearly no restrictions were placed on the Honigmanns’ movements – something that might have alarmed the Home Office and MI5 should they (or Litzy) have wanted to visit the UK, where Georg had several relatives. MI5 later showed some alarm when Litzy was reported to be planning a visit to the UK.

P 49 “Und doch ist es so gekommen, aus dem Bohemien war ein Kommunist geworden. Georg selbst konnte den Zeitpunkt und den Ort genau bestimmen, an dem es geschehen war: während seiner zweiten Ehe, der mit meiner Mutter in London, und dann im Internierungslager in Kanada 1940, wohin die Engländer die enemy aliens verschifften.ˮ

It thus came about that a Bohemian turned into a Communist. Georg could himself accurately pinpoint the place and time where and when it occurred: during his second marriage, that with my mother in London, and then in the Internment Camp in Canada in 1940, where the English shipped out the enemy aliens.

Again, the lie about Georg’s marriage to Litzy is reproduced, and astonishingly overlooked. Moreover, Georg’s clear memory of the conversion is sharply undermined by the fact that he qualifies it with the later experiences in Canada that involved Leopold Hornik.

P 55 “Zu Beginn der Nazizeit konnten seine Eltern noch eine Stelle in Barcelona finden, nach dem Franco-Putsch jedoch fűhlten sie sich dort auch nicht mehr in Sicherheit und schickten deshalb ihre beiden halbwűchsigen Söhne nach London, wo sich Georg als älterer Onkel – immerhin was er mehr als doppelt so alt und hatte eine Frau, eine Arbeit und eine Wohnung – um sie kűmmerte und den jűngeren der beiden Brűder, Andreas, schließlich auch zum Kommunismus hinűberzog, von dem er selbst gerade erst von seiner neuen Geliebten, die später meine Mutter wurde, űberzeugt worden war. So erzählte es Andreas.ˮ

At the beginning of the Nazi era, the parents of Andreas [Georg’s cousin] were still able to find a place in Barcelona, but, after the Franco Putsch, no longer felt safe there and therefore sent their two adolescent sons to London, where Georg, in the role of an older uncle – after all, he was twice their age and had a wife, a job and a flat – took care of them, and eventually converted Andreas, the younger of the two, to Communism, to which he had just been won over by his new love, who later became my mother. That is how Andreas told it.

At last Barbara indicates that Litzy was not yet his wife when he converted to Communism. The circumstances of the acceptance in Britain of his cousins are not clear: Georg’s MI5 records do not reflect their presence at any time, so far as I can tell.

P 60 “Es war Zufall, dass während meines ‘Asylsʼ in Ilmenau auch Andreasʼ Bruder, der nach dem Krieg in England geblieben war und sich seither John nannte, gerade zu Besuch war, und beide Brűder erzählten wieder davon, wie fűrsorglich sich damals Georg ihrer angenommen hatte, als sie 1939 noch als halbe Kinder, ohne Geld, ohne Ausbildung und ohne die Sprache zu kennen, in dem völlig fremden London angekommen waren.ˮ

It was by chance that, during my refuge in Ilmenau, Andreas’s brother, who had stayed in England after the war, and since then was known as John, was visiting at the same time. Both brothers further explained how Georg had welcomed them, when in 1939 they had arrived in the utterly strange city of London as mere children, unprepared, without money, and not knowing the language.

Further startling facts about Georg’s extended family.

P 62 “So kam Georg 1931 als Korrespondent der Vossischen Zeitung nach London, lernte schnell Englisch, ‘denn wenn du Latein kennstʼ, sagt er, ‘lernst du alle anderen Sprachen im Handumdrehenʼ, lebte mit Ruth im gutbűrgerlichen Westen Londons zwischen Hyde Park und Holland Park, und dort heirateten sie endlich auch.ˮ

Thus Georg arrived in London in 1931 as correspondent for the Vossische Zeitung, quickly learned English, ‘for, if you know Latin’, he said, ‘you can learn other languages in a heartbeat’, lived with Ruth in a posh area of London between Hyde Park and Holland Park, and there they eventually got married.

Before being despatched to London, Georg had apparently bluffed his editor at the newspaper about his knowledge of English. Yet another lie appears: from his account, and the records in his Personal File, he returned to Germany to marry Ruth in December, 1932, in Frankfurt-am-Main.

P 63 “1936 hatte er gemeinsam mit Ruth die britische Staatsbűrgerschaft beantragt, die ihnen jedoch verweigert wurde. Seine deutsche Heimat sah er eben siebzehn Jahre später wieder.ˮ

In 1936, along with Ruth, he applied for British citizenship, which was, however, denied to both of them. He did not see his German homeland until seventeen years later.

This statement, rather curiously, excludes the German Democratic Republic as part of his homeland, but does fix a year (1953) in which he and Gisela visited West Germany.

P 64 “Der Horizont des Kontinents verfinsterte sich mehr und mehr, vor allem nach der Kristallnacht 1938 trafen immer mehr Freunde, Bekannte und Verwandte aus Deutschland in England ein, die Vettern und Cousinen aus Breslau, Hans und Franz, Ernst, Emil, Hedwig und Antonia mit ihren Kindern und einige Kinder und Jugendliche ohne ihre Eltern, wie Andreas und John, der damals noch Hans hieß.ˮ

The horizon of the Continent became darker and darker. After Kristallnacht in 1938, especially, many more friends, acquaintances and relatives arrived in England from Germany, the nephews and cousins from Breslau, Hans and Franz, Ernst, Emil, Hedwig and Antonia with their children and some children and young persons without their parents, such as Andreas and John, who was still known as Hans at that time.

The hitherto anonymous character of the extended Honigmann family and circle is quite remarkable.

P 65 “Von der großen Reportage-Reise durch die USA, die Georg zu dieser Zeit unternahm, hat er später wenig erzählt, zwar erwähnte er manchmal eine Amerikareise, ohne sie aber in eine Zeit einzuordnen oder mit einem Ereignis zu verknűpfen, eigentlich hat er immer nur ganz allgemein vom Autofahren auf den Highways erzählt, was fűr ein Vergnűgen das gewesen sei . . . ˮ

Georg said little about the extensive reporting trip he through the USA that he undertook at this time. He did indeed mention an American visit from time to time without placing the date it took place or connecting it with any particular experience. He always spoke very generally about motoring on the highways, and what pleasure that had given him . . .

The visit took place in 1938.

P 67 “‘Bevor ich deine Mutter kennenlernte, war ich weit davon entfernt, ein politischer Mensch zu seinʼ, hat mir mein Vater in einem seiner Briefe aus der Kur in Bad Elster geschrieben, die der nun űber sechzigjährige Mann so gut wie jedes Jahr in Anspruch nahm.ˮ

‘Before I met your mother, I was a long way from being a political person’, my father wrote to me in one of his letters from the spa in Bad Elster, treatment that the now sixty-plus year-old claimed for himself practically every year.

A reinforcement of the influence that Litzy reputedly had over him. But can it be trusted?

P 67 “Meine Mutter ist er in London begegnet, geheiratet haben die beiden aber erst nach dem Krieg in Berlin, und dort ließen sie sich auch wieder scheiden. Litzy, die meine Mutter wurde, lernte er durch seinen Kollegen Peter Smolka kennen, der schon 1930 als Korrespondent der großen Wiener Tageszeitung Neue Freie Presse nach London gekommen war und dort zusammen mit seinem britischen Kollegen H. A. R. ‘Kimʼ Philby eine Presseagentur gegrűndet hatte, die die britischen Zeitungen mit Nachrichten aus Mittel- und Ost-europa belieferte und die er später an den Exchange Telegraph verkaufte.ˮ

He met my mother in London, but they did not get married until after the war, in Berlin, and it was there that they applied again for a divorce. He became acquainted with Litzy, who was to become my mother, through his colleague Peter Smolka, who had already arrived in London as correspondent of the major Vienna daily newspaper, the Neue Freie Presse, and who had founded in collaboration with his British friend H. A. R. Philby a press agency, which supplied the British press with news from Central and Eastern Europe, and which he later sold to the Exchange Telegraph.

At last Barbara acknowledges the fact that her parents married in Berlin. (But, concerning the divorce, why the ‘again’? Because they had both been divorced before?) The details about Smolka’s arrival in England are wrong. He was only eighteen years old when he arrived in January 1931, and he was registered as a student. Smolka did indeed, on November 15, 1934, when he was London editor for the Neue Freie Presse, request permission from the Home Office for him and Philby to set up London Continental News Ltd., a rather careless initiative that should have alerted the authorities to Philby’s political alliances. Why Barbara states that ‘Smolka’ later sold it rather than ‘Smolka and Philby’ is provocative, although Philby was in reality a ‘sleeping’ partner. And the origin and timing of his friendship with Kim are left unsaid.

P 68 “Die Frau von Peter Smolka war Lotte, Litzys beste Freundin noch aus Kindertagen, als sie zusammen in Wien zur Schule gingen, ebendie, die mir nach Georgs Tod noch so wűtend von seiner Affäre mit der spanischen Tänzerin erzählte, und Philby war Litzys Ehemann.ˮ

“Seit er meiner Mutter bekannt worden war, wurde Georg vom britischen Inlandsgeheimdienst MI5 beobachtet und bekam dort ein Dossier, weil er damit in Kreise eintrat, deren Nähe zu oder Mitgliedschaft in der Kommunistischen Partei bekannt war oder die gar der Spionage fűr die Sowjetunion verdächtig wurden. Dieser Verdacht hat sich in den meisten Fallen bestätigt und stellte sich Jahre später sogar als noch viel begrűndeter heraus, als es sich der MI5 in seiner schlimmsten Albträumen auch nur hatte vorstellen können.ˮ

“In dem engen Wiener Kreis um Peter Smolka, Lotte und Litzy traf Georg zum ersten Mal Menschen, meistens junge und viele jűdisch, die schon seit längerer Zeit politisch engagiert und aktiv in Vereinen organisiert waren, links oder zionistisch, oft beides, wie er sie wohl vorher noch nicht getroffen hatte.ˮ

Peter Smolka’s wife was called Lotte, Litzy’s best friend from her childhood days when they attended school together in Vienna, the very same woman who spoke so angrily, after his death, about Georg’s affair with the Spanish dancer. Philby was Litzy’s husband.

Ever since he became acquainted with my mother, Georg was watched by MI5, Britain’s domestic security service, and thus a file was opened on him, since by that relationship he entered social circles whose proximity to, or membership of, the Communist Party was known, and the circles might even have been suspected of spying on behalf of the Soviet Union. That suspicion was in most cases confirmed, and was exposed many years later as having had strong justification, in a way that MI5 could only have imagined in its worst nightmares.

In the tight Viennese circle around Peter Smolka, Lotte and Litzy, Georg met for the first time persons, mostly young and many Jewish, of the left or Zionist, frequently both, whom he could never have come across beforehand.

The important link between Litzy and Smolka is revealed, which explains how Philby and Smolka so easily started to conspire in 1934. (I reported last month that Smolka has been claimed as assisting Kim and Litzy in Vienna in February 1934, a story that Smolka’s family has promulgated orally, and one that has also appeared in the media, since Smolka’s godson, Peter Foges, avowed it in an interview presented in an on-line segment from Lapham’s Quarterly. I have started a research project to investigate this claim, and I shall be reporting more in January 2024. It has very dramatic implications.) Georg was in fact watched by MI5 as soon as he arrived in the United Kingdom, and his movements were noted: the assertions he made to his daughter may have been false, and Barbara, since she claims to have inspected her father’s file, would know about the earlier surveillance. The account of proven espionage is enticing, since it specifically does not include Philby. MI5 later stated that they knew that Litzy was a Soviet agent, yet ‘MI5’s worst nightmares’ would appear to be something of a hyperbole.

P 69 “Litzy und ihre Freunde waren schon vorher in der ‘Roten Hilfeʼ und der ‘Internationalen Arbeiterhilfeʼ organisiert und hatten Geld fűr sie gesammelt, Kleider und Essen verteilt und bei ihren Versammlungen revolutionäre Pläne geschmiedet, und in diesen dramatishen Februartagen wählten sie natűrlich die Seite des sozialdemokratischen Schutzbűndler und schließlich der Kommunisten, obwohl sie meistens aus gutbűrgerlichen Verhältnissen stammten, es war wohl auch eine Revolte der Jugend. Sie gaben sich kommunistische Träumen von Gleichheit und Gerechtigkeit hin, die dann fast ein ganzes Leben hielten, auch wenn sie dabei oft die Augen fest verschließen mussten. Vielleicht weil sie so jung waren, sind sie dabei in ihrem politischen Engagement sehr weit gegangen. Sie ließen sich gleich am Anfang vom Sowjetischen Geheimdienst rekrutieren und haben in den Jahren nach 1934 dann fűr ihn spioniert, nachdem sie in Asyl vor rassicher und politischer Verfolgung gefunden hatten, während der Zeit des Hitler-Stalin-Pakts, als Großbritannien sich Hitler gegenűber ohne Verbűndete fand, und später, als die Sowjetunion zum Allierten Großbritanniens wurde, und schließlich noch viele Jahre darűber hinaus, nach dem Sieg uber Hitler, während des Kalten Krieges.ˮ

Litzy and her friends had already been enrolled in the ‘Red Aid’ and ‘International Workers’ Aid’ organizations, and had collected funds for them, distributed clothing and food, and forged revolutionary plans at their meetings. In these dramatic February days they of course chose the side of the Schutzbund [the paramilitary Defence League] and eventually that of the Communists, even though most of them came from bourgeois backgrounds: it was indeed a youth revolt, as well. They indulged in communist dreams of Equality and Justice, which then lasted for almost all their lives, even though they had to close their eyes tightly while doing so. It was probably because they were so young that they drove their political engagement so deeply. Right from the start, they let themselves be recruited by the Soviet Secret Service, and consequently spied for it in the years after 1934, after they had found refuge from racial and political persecution, during the time of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, when Great Britain was facing Hitler without any allies, as well as later, when the Soviet Union joined Britain’s allies, and finally, for several years more during the Cold War following the victory over Hitler.

Enough said. Having been hooked in, they would not have been allowed to leave, even if they wanted to. Yet what is highly significant about this paragraph is the fact that it states that ‘Litzy and her friends’ ‘let themselves be recruited by the Soviet Secret Service’ in 1934. Since Lotte was Litzy’s closest friend, and she was married to Peter Smolka, and Litzy then married Kim Philby, it appears to confirm that all four became NKVD agents at this time.

P 70 “Als sie Georg durch ihre Wiener Freunde in London kennenlernte, war Litzy noch mit Philby verheiratet, hatte aber schon einen anderen Geliebten, und Philby hatten andere Frauen, ich glaube, sie lebten auch schon in verschiedenen Wohnungen. Georg war noch mit Ruth verheiratet, ihre Wege trennten sich jedoch bald.ˮ

When Georg got to know her through her Viennese friends in London, Litzy was still married to Philby, although she already had another lover, and Philby also had other women in his life. I believe they already lived apart. Georg was still married to Ruth, but they went their separate ways.

At some stage, Litzy had affairs with Michael Stewart and Anthony Milne: there may well have been others. This note would appear to confirm that the relationship between Litzy and Georg started early in 1940, after Litzy returned from France. Philby had affairs in Spain during his time there as a journalist during the Civil War. Part of the ‘living apart’ was the fact that they were both on assignments abroad for much of the late 1930s.

P 72 “Jedenfalls konnte ihm Ruth darin nicht mehr folgen, so bestätigen es auch die files von MI5: G. H. had no firm political views until he met Litzy.ˮ

In any case, Ruth could no longer follow him in his views, as the files of MI5 confirm: G. H. had no firm political views until he met Litzy.

Georg had claimed to believe in ‘pacifist humanism’ up till then. Thus the split between him and Ruth had much to do with political affiliation.

P 73 “Die Berichte der files und Akten aber erfanden fűr mich nun die Vergangeheit eines Mannes aus einer weit entfernten Lebensepoche, eines Mannes, der nicht mein Vater war.ˮ

The reports from the files and documents revealed to me, however, the past of a man from a long-distant period, of a man who was not my father.

This would seem to be self-delusion on Barbara’s part. Georg had pulled the wool over her eyes.

P 74 “Er ließ auch nie Zweifel daran, dass er Amerika England vorzog, und teilte nicht die pro-englische Euphorie seiner ersten Frau und eigentlich auch seiner zweiten, meiner Mutter. ‘Ja, die Engländer sind tolerantʼ, meinte er, ‘aber vor allem sind sie herablassend: ja, sie sind fair, aber nur solange du nicht die Grenzen ihrer Toleranz uberschreitest – da verstehen sie nämlich űberhaupt kein Spaß mehr, und ihr sprichwörtlicher Humor löst such in Luft auf. ʼˮ

He left no doubt over the fact that he preferred America to England, and shared neither the pro-English euphoria of his first wife, nor even that of his second, my mother. ‘Yes, the English are tolerant’, he would say, ‘but above all they are condescending: yes, they are fair, but only as long as you do not overstep the boundaries of their tolerance – in that event they don’t allow any more joking, and their proverbial humour flies out of the window’.

It is perhaps surprising that Litzy’s enthusiasm for England is disclosed: in her own conversations with her daughter, she emphasized her fond memories of Paris. Thus she may have been a reluctant – but pragmatic – émigré to East Berlin in September 1946. Unlike Georg, of course, she had a British passport, and Georg forever had a grudge because the British appeared to have rejected him on account of his German/Jewish origins. The observations on ‘tolerance’ show the utter hypocrisy of those Communists who sheltered under Britain’s wing and then tried to undermine its way of life.

P 75 “Georg war nämlich zugleich misanthropisch and gesellig, bissig und charmant, immer witzig und zugleich immer ein bisschen traurig, widersprűchliche Eigenschaften, die vielleicht von den ‘miesen Erbschaftʼ stammten, dem ewigen Zwischen-den-Stuhlen-Sitzen.ˮ

Georg was indeed misanthropic and sociable at the same time, mordant and charming, forever amusing and yet always a bit melancholy, contradictory qualities that perhaps derived from his ‘wretched background’, the eternal ‘sitting-between-two-stools’.’

This item of pop psychology makes out as unusual what one could accept as normal behaviour from anyone accustomed to mixing successfully in varied company. Georg sought psychiatric help to no avail: he was perhaps not smart enough to grow up and sort things out himself, and instead blamed what he saw as his failings of character on childhood repressions.

P 76 “Über die Anfangszeit von Georg und Litzy als Paar weiß ich wenig, denn ihre Erzählungen aus dieser Zeit handelten fast ausschließlich vom Krieg, der Internierung in Kanada, den Bomben auf London und waren wohl außerdem von ihren Geheimdienst-Verstrickungen űberschattert.ˮ

I know little about the early days of Georg and Litzy as a couple, for their stories from this period dealt almost exclusively with the war, with internment in Canada, the bombs falling on London, and were besides overshadowed by their entanglements with intelligence work.

Georg was fortunate enough to avoid the Battle of Britain (July to October 1940), since he was interned in Canada throughout. Unless he was being creative, those memories must have derived from Litzy, who was trying to help engineer his release.

P 77 “Er sprach natűrlich fließend Englisch, er las Englisch und schrieb Englisch, aber ohne die Begeisterung meiner Mutter, die űberhaupt bis zum Ende ihres Lebens lieber englisch als deutsche Bűcher las; in den Gesprächen meiner Eltern mischten sich die Sprachen des öfteren, weil das Englische manchmal die bessere Formulierung bereithielt, so wie Georg die Hauswirtin in Hirschgarten die ‘Landladyʼ nannte.ˮ

He of course spoke fluent English, read it and wrote it, but without the enthusiasm of my mother, who overall preferred to read English books rather than German ones to the end of her life; when they chatted, my parents frequently switched between languages, since English often offered a better formulation, as, for example, in Georg’s calling the landlady in Hirschgarten the ‘landlady’.

More insights on the ‘Anglicization of Litzy’. Since the best translation of ‘Hauswirtin’ is ‘landlady’, this example would appear to be suboptimal.

P 83 “Obwohl er mehrfach die Britische Staatsangehörigkeit beantragt hatte und sich wohl bis zur Begegnung mit Litzy sehr gut ein weiteres Leben mit Ruth in London zwischen Hyde Park und Holland Park hätte vorstellen konnen, weigerte er sich hartnäckig, seinen Namen zu anglisieren, davon sprach er später immer voller Stolz wie von einer tapferen Tat, sondern beharrte auf der deutschen Schreibung des Namens und ließ nicht einmal das zweite ‘nʼ in seinem Namen fallen.ˮ

Even though he had applied for British citizenship several times, and up until his meeting with Litzy would have imagined very well an ongoing life with Ruth in London between Hyde Park and Holland Park, he obstinately refused to anglicize his name, and always spoke of that decision as if it had been a courageous deed. On the contrary, he insisted on the German spelling of his name and never let the second ‘n’ in Honigmann ever be dropped.

Fairly petty: ‘Honigman’ would still have looked very German. Maybe it was because he had been refused citizenship that he clung to the German formulation. He was, of course, stateless when in the United Kingdom, since the German government refused to renew his citizenship.

P 87 “Georg fűhlte sich wie viele andere zu den Kommunisten hingezogen, die sich vom ersten Tag an organisierten, manche von ihnen, vor allem die Österreiecher, kannten sich ja schon aus den Bűrgerkriegszeiten in Wien, und sie beeindruckten Georg vor allem dadurch, wie selbstbewusst sie gegenűber der Lagerleitung und Lageradministration auftraten, um bestimmte Bedingungen zu fordern, den unsinnigen Feind-Status abzuwenden und stattdessen den Status all dieser inhaftierten Männer als Nazi-Flűchtlinge anzuerkennen.ˮ

Like many others, Georg felt himself strongly drawn to the Communists who were from the first day well-organized. Many of them, above all the Austrians, knew each other from the civil war days in Vienna, and above all they impressed Georg by virtue of the fact that they confidently stepped up to the tasks of camp leadership and administration, in order to demand certain conditions, to overturn their absurd status as ‘enemy’ and instead to have the status of all internees as refugees from Nazism acknowledged.

This testimony from Canada might tend to undermine Georg’s firmness of convictions arising from his few months with Litzy.

P 88 “Mit diesen Erklärungen warben sie vor allem bei den jugendlichen Internierten, von denen vorher viele Zionisten waren, aber Zion war weit und kompliziert, und der Kommunismus was schließlich so einfach, wurde ihnen erklärt, und obgleich Georg gar nicht mehr jugendlich, sondern inzwischen fast vierzig war, ließ auch er sich vom Elan dieser Leute tragen, schließlich war er ja schon von Litzys Freunden aus dem Wiener Kreis in London, von denen sich auch einige unter den Internierten befanden, initiiert worden.ˮ

“Jede der verschiedenen Gruppen in Lager konnte einen Kandidaten aufstellen, Georg wurde von den Kommunisten aufgestellt und mit großer Mehrheit auch von den anderen Gruppierungen gewählt, was er nie zu betonen vergaß, ‘auch von allen anderenʼ.ˮ

With these explanations they wooed above all the younger internees, many of whom had been Zionists beforehand. Yet Zion was distant and complicated, and Communism was at the end of it all quite simple, or so it was explained to them, and although Georg was no longer young, but at the time almost forty years old, he let himself be carried away by the spirit of these people. Finally, he had already been initiated by Litzy’s friends from the Vienna circle in London, some of whom were also among the internees.

Each of the various groups in the camp could appoint a representative. Georg was appointed by the Communists and elected as well, by a large majority, by all the other groups, something he never forgot to emphasize: ‘as well by all the other groups’.

Somewhat surprising for a man with an apparently diffident personality. Maybe his language skills, and tact, came to the fore.

P 90 “Wie so viele andere auch hat sich Martin jedoch 1968, nach dem Einmarsch der Sowjetischen Truppen in die Tschechoslowakie, mit seiner Partei űberworfen, und auch fűr Georg war dieses Ereignis ein Wendepunkt, von dem an er in seinen kommunistischen Überzeugungen deutlich nachließ und seine Enttäuschung gar nicht mehr zu verbergen suchte.ˮ

Like so many others, Martin had however fallen out with his party after the invasion by Soviet troops of Czechoslovakia in 1968. For Georg this experience was also a turning-point after which he distinctly abandoned his communist convictions and no longer attempted to conceal his disillusionment.

‘Martin’ (unidentified further in the text) was Leopold Hornik, who had been interned in Canada alongside Georg. One might ask why it took the two of them to wait until the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 to discover a turning-point. Were (for example) the 1952 trials and executions of Slánský and others not enough? Why was the brutality of the Hungarian Uprising of 1956 not an adequate stimulus? Perhaps it was not safe to show dissent before 1968, the year that Slánský was exonerated.

P 92 “Georg gehörte zu den ersten, die aus dem Lager in Kanada entlassen wurden, Litzy und seine Kollegen von Exchange Telegraph hatten Himmel und Hölle in Bewegung gesetzt, um die Entlassung zu bewirken. In einem seiner Lebensläufe, die er später während der zahllosen Parteiűberprufungen der frűhen fűnfziger Jahre in der DDR zu schreiben hatte und die ich in seiner Stasi-Akte fand, schrieb er: ‘Nach meiner Freilassung meldete ich mich in London bei der Partei und wurde anschließend als Mitglied aufgenommen. Alle beruflichen Fragen und Entscheidungen, wie beispielsweise mein Eintritt in die Nachrichtenagentur Reuter, wurden mit der Partei abgesprochen.ʼˮ

“Als er Anfang des Jahres 1941 nach London zuruckkehren konnte, erwartete ihn dort Litzy, seine neue Geliebte, und er zog aus der Wohnung zwischen Hyde Park und Holland Park aus, in der er mit Ruth gewohnt hatte, und lebte fortan mit Litzy in einer Wohnung in St. Johns Wood.ˮ

Georg was one of the first to be released from the camp in Canada. Litzy and his colleagues at the Exchange Telegraph had tried to move heaven and earth to secure his release. In one of his autobiographical accounts that he was required to write during the countless DDR Party examinations of the early nineteen-fifties, which I found in the Stasi-Files, he had written: ‘After my release I reported to the Party in London and was firmly accepted as a member. All professional questions and decisions, for example my entry into the Reuter’s news agency, were disputed by the Party.

When he was able to return to London at the beginning 1941, Litzy, his new love, was waiting for him, and he moved out of the flat between Hyde Park and Holland Park which he had occupied with Ruth, and went to live with Litzy in a flat in St John’s Wood.

That Litzy had become a passionate supplicant on Georg’s behalf is, perhaps unsurprisingly, not found in his MI5 dossier, but points to the fact that she must have become besotted over him in the short time since they met (early 1940) before his detention (July 19). Honigmann’s statements after his own release attest to his devotion and dedication to Ruth’s liberation from internment, since he expresses a desire to be re-united with her and her mother in the family home, but that was evidently a charade. (The word ‘abgesprochen’ is ambiguous in meaning: it strongly suggests ‘refused’, but since Georg was indeed admitted to Reuters, I have selected the variant ‘disputed’ to indicate that no decision was made independently without Moscow approval.)

P 94 “ . . . das war es, wovon Georg und Litzy später am meisten erzählten, das war es, wovon ich wieder und wieder hörte, die Ruhe der Engländer, der Beistand, den sie gegenseitig leisteten.ˮ

“Meine Eltern haben mir ein ganzes Epos űberliefert von dem stoischen Heldenmut, dem klaglosen Wegräumen der Trűmmer, den gegenseitigen Ermutigungen, und die Bewunderung, die sie dafűr empfanden, klang auch nach vielen Jahren noch in ihren Erzählungen nach und hat mein Englandbild fűr immer geprägt. Umso unverständlicher war und ist mir noch heute die Entscheidung Litzys und ihres Freundeskreise, in die sich Georg hatte hinziehen lassen oder von der er doch wenigstens Kenntnis haben musste, diese so bewunderte Land zu hintergehen und es fűr die Sowjetunion auszuspionieren. Sie haben mir diesen Widerspruch nie erklären können, später in ihrem DDR-Leben war das alles schon weit weg und lange vegangen, oder sie haben es einfach weit weggeschoben; ob sie sich dafűr je schuldig gefűhlt haben, habe ich nie erfahren.ˮ

. . . that was what, what I heard again and again, and what Georg and Litzy talked about most, the calm of the English people, and how they helped each other out.

My parents passed on to me a complete epic story of stoical courage, of the removal of debris without complaining, of the mutual inspiring of courage. The admiration they felt for it resounded in their description of it to me many years later, and it has stamped my picture of England for ever. The decision made by Litzy and her circle of friends, into which Georg had been drawn, or about which he must have at least known, to deceive this wonderful country and betray it through espionage to the Soviet Union, was all the more incomprehensible to me then, and remains so today. They were never able to explain this contradiction to me: later in their life in the DDR everything was a long way away, and in the distant past, or they simply pushed it far into the background: whether they felt any guilt over it I was never able to determine.

This flattering appreciation of Londoners’ spirit during the Blitz displays a certain naivety on the author’s part. Once her parents had taken the decision to work for the Soviet Union, it was irrevocable. Otherwise they would have probably been found dead in a hotel room, with the symptoms of a heart attack brought about by some untraceable poison, like so many of Stalin’s victims. (Goronwy Rees just escaped assassination: Anthony Blunt alone remained unscathed.)

P 96 “Der Club wurde jedoch, im Unterschied zu anderen, vor allem judischen Emigranten-Organisationen, mehr und mehr von Kommunisten dominiert, und das entging auch dem MI5 nicht, der trotz oder wegen der Allianz mit der Sowjetunion die neue Sympathie fűr die Kommunisten und deren Aktivitäten genau beobachtet, wenn auch nicht genau genug, um herauszufinden, dass die echten Spionen fűr die Sowjetunion sich nicht gerade in den offen kommunistischen Gruppen zeigten. ‘Mein Gott, wie naiv die Engländer warenʼ, sagte manchmal meine Mutter: sie wusste ja, wovon sie sprach.ˮ

In contrast to the other, primarily Jewish emigrant organizations, the Club was dominated more and more by Communists, and that fact did also not elude MI5, which, despite or perhaps on account of the alliance with the Soviet Union, closely followed the fresh sympathy for the Communists and their activities, though not closely enough for it to discover that the real spies for the Soviet Union did not show their faces in the open communist groups. ‘Dear Lord, how naive the English were!’, my mother used to say: she knew what she was talking about.

The Club was Der Freie Deutsche Kulturbund (the Free Germann League of Culture) which maintained a centre in Hampstead. Indeed, it was the strategy of Moscow Centre to have its espionage activities directed well away from the Party itself. MI5 persisted in believing that any dangerous element of Soviet subversion would automatically have been a member of the party at one time, and would have mixed with members.

P 100 “Die Partei hatte beschlossen, dass Georg und Litzy nach Deutschland zurűckkehren sollten, und zwar in die sowjetisch besetzte Zone, um den Russen zu helfen, dort auf den Trűmmern des nationalsozialistischen Deutschland ein international eingebundenes, das hieß, ein an die Sowjetunion fest angebundenes sozialistisches System aufzubauen.ˮ

“Georg hat mir selbst einmal gesagt, ‘schon als ich bei Reuters war, habe ich fűr die Russen gearbeitetʼ.ˮ

The Party had decided that Georg and Litzy should return to Germany, to the Soviet zone, of course, in order to help the Russians construct out of the ruins of Nazi Germany a tightly bound international socialist system – that is to say, one inextricably linked to the Soviet Union.

Georg told me himself: ‘As soon as I was employed by Reuters, I started working for the Russians.’

If the Party decided that, why did it ordain that Georg should leave in April 1946, but Litzy not until four months later? After all, the rather airy and impractical Georg was perhaps not first choice for the task of ‘socialist reconstruction’, and leaving Litzy behind might have caused some great embarrassments if MI5 had been on its toes. I am sure that a very suspicious MGB was performing some strenuous due diligence. As for Georg’s joining Reuters, that appears to be another lie. He joined Reuters in December 1943, but had already been working for the Soviet cause for some time.

P 101 “Andererseits berichten die files vom MI5, das musste ihnen jemand zugetragen haben, dass Georg eigentlich gar nicht nach Deutschland zurűckkehren wollte und dass es wieder Litzy war, die ihn dazu űberredete: When, after the war she announced, that they would go to the Soviet sector of Berlin, he was obviously unwilling and held back.ˮ

On the other hand the MI5 files inform us (something that must have been reported to them) that George in fact had no desire to return to Germany and that it was again Litzy who convinced him of the necessity: ‘When, after the war she announced that they would go to the Soviet sector of Berlin, he was obviously unwilling and held back.’

This again sheds light on the paradox. If Litzy was so keen, why did she not travel with her lover? She no doubt informed Georg that it was too late to change his mind about the Communist cause now. But maybe Georg still hoped that a position with the Control Commission would allow him to live in the far more congenial British sector of Germany.

P 102 “Unter Litzys Einfluss jedoch und dem Druck der Partei, die das so geplant hatte, lief er zu den Russen űber und arbeitete fűr sie im Nachrichtenbűro der sowjetischen Militäradministration.ˮ

Under Litzy’s influence, however, and the pressure from the Party, who had planned it that way, he deserted to the Russians and worked for them in the news bureau of the Soviet military administration.

How voluntary this step was must be debatable. The Party did not apply ‘pressure’ as if it were a kind of soft influence. It threatened. And Georg may have been abducted by force.

P 104 “In dieser Zeit muss die Affäre mit der spanischen Tänzerin stattgefunden haben, . . . ˮ

“Litzy war zunächst noch in London geblieben, um zu warten, bis Georg eine Wohnung fand . . . ˮ

His affair with the Spanish dancer must have taken place at this time. To begin with, Litzy had stayed in London, waiting until Georg found somewhere to live.

The presence of attractive Spanish dancers in post-war Berlin is a phenomenon to be marvelled at. No doubt this particular example was spying on Georg during their affair. Equally amusing is the notion that Litzy would have been waiting for Georg to scout around and find a desirable accommodation for the two of them. This was rubble-strewn Berlin in 1946, after all, and the Party would have told him where to live.

P 106 “Georg und Litzy heirateten 1947, nachdem sie sich beide zuerst hatten scheiden lassen műssen, Georg von Ruth und Litzi von Kim Philby.ˮ

Georg and Litzy were married in 1947, after they had both evidently arranged their divorces, Georg from Ruth, and Litzy from Kim Philby.

A paraphrase of the facts. Georg had legally divorced Ruth on November 23, 1942. The ‘evidently’ suggests a belief that the Litzy-Kim divorce must have happened in order for the Litzy-Kim marriage to be legal, but no ‘evidence’ is offered.

P 109 “Von den höheren Partei-Kadren, die aus Moskau zurűckgekehrt waren und wussten, dass sie ihr Überleben dort einzig dem Zufall under der völligen Unterordnung unter die ‘Zentraleʼ zu verdanken hatten, zu deren Befehlsempfängern sie jetzt geworden waren, schlug ihnen ebenso großes Misstrauen entgegen, da sie sich nämlich in den westlichen Ländern des Exils vielleicht eine gewisse Freiheit bewahrt hatten. Von dieser letzten inneren Freiheit mussten sie gesäubert werden, und so zog nun eine Säuberungswelle die nächste nach sich, und in allen Ostblockstaaten wurden Prozesse gegen ‘Kosmopoliten, Zionisten und Agenten der amerikanischen Finanzoligarchieʼ inszeniert, in Bulgarien, in Ungarn, in Rumanien und schließlich in Prag, und sie trugen immer deutlicher einen antisemitischen Charakter.ˮ

The upper-level Party cadres, who had returned from Moscow, and knew that they could attribute their survival there only to the happenstance of their utter submission to ‘Moscow Centre’, whose messenger-boys they had become, exercised massive mistrust against them [the emigrants], since the latter had perhaps been able to enjoy a certain freedom in those western countries where they had been exiled. They would have to be purged of this last inner liberty, and thus a wave of purging followed closely after. In all the states of the Eastern Bloc trials against ‘cosmopolitans, Zionists and agents of the American financial oligarchy’ started, in Bulgaria, in Hungary, in Rumania and lastly in Prague, and they took on an ever more clearly anti-Semitic character.

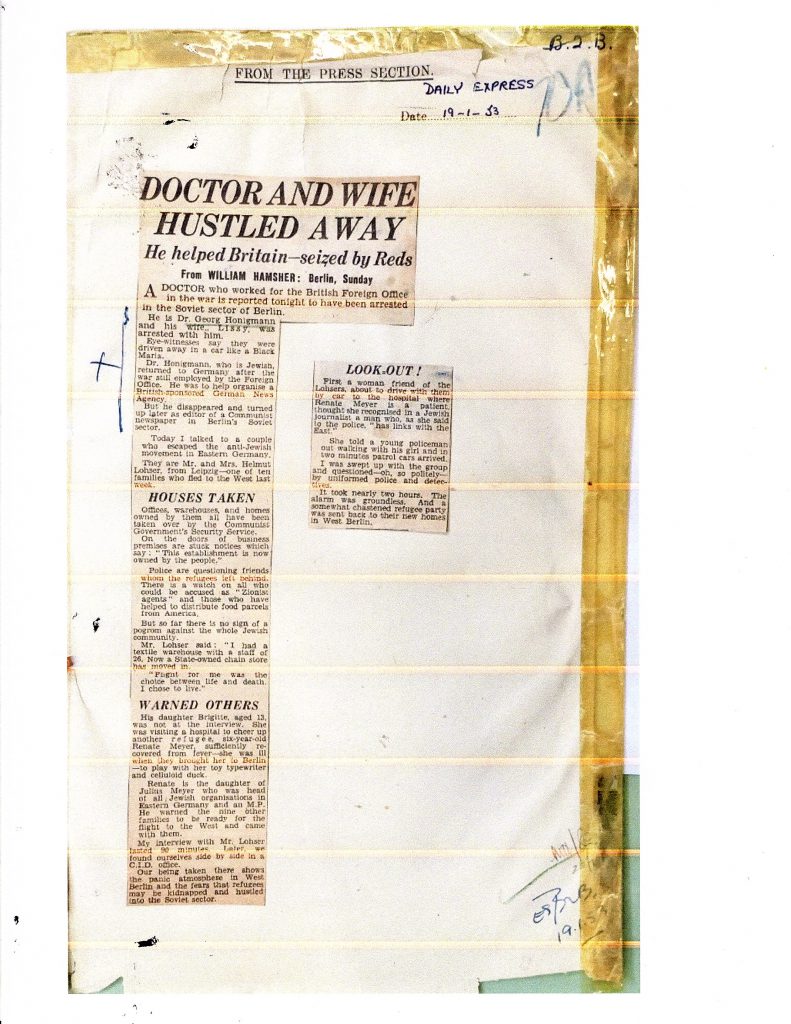

The very sad, but real, fact about the suspicions of the Party organs concerning those who had survived the war in relative comfort, and had thus clearly been exposed to bourgeois influences. A true Stalinist philosophy. Ms Honigmann says nothing about the arrest and interrogation of Georg and Litzy in early 1953.

P 110 “In Georgs Stasi-Akte häufen sich die Berichte der Nachbarn und Ortsparteigruppen-Mitglieder aus Karolinenhof, die ihn ‘westlicher Kleidungʼ, ‘uberheblichen und arroganten Auftretensʼ, ‘Beherrschung der englischen Sprache in Wort und Schriftʼ, ‘reservierten Verhaltens‘, ‘mangelnden Parteibewusstseinʼ, ‘Kontakten zu Ausländernʼ beschuldigten und sehr wahrscheinlicher Verbindungen mit dem amerikanischen Geheimsdienst verdächtigen.ˮ

In George’s Stasi-Files reports from neighbours and members of local party groups in Karolinenhof pile up, accusing him of ‘western clothing’, ‘overbearing and arrogant behaviour’, ‘mastery of the English language, both orally and in writing’, ‘deficient party-consciousness’, ‘contact with foreigners’, and casting suspicions on him of highly probable connections with American intelligence.

Further evidence of the resentment and suspicion.

P 112 “Hätte ich nicht besser in London bleiben sollen, warum bin ich zurűckgekommen, wird er sich wohl gefragt haben, warum habe ich mich zur Kommunistischen Partei drängen lassen, wo ich doch nie űber Herman Hesse hinausgekommen bin.ˮ

‘Wouldn’t I have done better to stay in London?’, ‘Why did I return?’, he must indeed have asked himself. ‘Why did I let myself be forced into the Communist Party, when I had never really escaped from Herman Hesse?’

Indeed.

P 116 “Nach der Scheidung meiner Eltern im Jahr 1956, ich war gerade eingeschult worden, űbernahm Georg das Grundstűck und das Haus mit der Schauspielerin, und unsere letzte Begegnung zu dritt fand auch dort statt, nachdem ich gerade jugendgeweiht worden war.ˮ

After my parents separated in 1956, when I had just started school, Georg occupied the property and house with the actress, and the last meeting between the three of us took place there, just after I had celebrated coming of-age.

Jugendweihe is a German secular ceremony (Youth Consecration) celebrated about age 14 – hence the year would be 1963.

P 120 “Wir besuchten ihn [Wolfgang Gans Edler Herr zu Putlitz] manchmal in seinem Haus und gingen dann zusammen űber die märkischen Sandwege zwischen den Kiefern, Georg und er kannten sich nämlich schon aus England, diese Bekanntschaft is auch in den files des MI5 bemerkt, der Gans Edle Herr wird da Baron gennant.ˮ

“Genau wie Georg setzte er sich später von der britischen Besatzungszone in die sowjetische besetzte Zone ab und bot den Russen seine Mitarbeit an, die ihn wahrscheinlich schon in der Zeit in London angeworben hatten.ˮ

We frequently visited him [zu Putlitz] at his house, and walked together along the sandy paths that bordered the Scotch pines. He and Georg knew each other well from their time in England, and this friendship is also noted in the MI5 files; the Gans Edler Herr was known as ‘Baron’.

Just like Georg, he deserted from the British occupation zone to the zone occupied by the Soviets, and he offered his cooperation to the Russians, who had probably already wooed him during his time in London.

Zu Putlitz was another shady character who fled to the British side shortly after war broke out, when he was about to be unmasked as a spy. He was also dispatched (by MI6) to West Germany after the war, but had to return to the UK. Ms Honigmann’s account suggests that zu Putlitz’s and her father’s ‘desertions’ were contemporaneous, but, after taking British citizenship in 1948, zu Putlitz did not defect to East Germany until January 1952. The ‘Gans Edler Herr’ is probably a sarcastic pun: his name was Wolfgang Gans [goose] Edler [noble] zu Putlitz, but the formulation suggests ‘ganz edler Herr’, an ‘utterly noble gentleman’. Why the Soviets thought he might be worth wooing is not clear.

P 129 “Eine Anzahl ehemaliger Emigranten lebte dort, so John Hartfield und Wieland Herzfelde, Giselas und Georgs Nachbarin war Elisabeth Hauptmann, und eine Etage darűber wohnte John Peet, den Georg noch aus England kannte, wie auch dem MI5 nichtentgangen ist, das schon ihre Bekanntschaft in London und ihre Nähe zu den Kommunisten festgehalten hat.ˮ

A number of former emigrants lived there, such as John Hartfield and Wieland Herzfelde, Elisabeth Hauptmann was a neigbour of Georg’s and Gisela’s, and John Peet, whom Georg had known from his London days, lived on the floor above. MI5 had failed to notice their relationship, even though the Security Service had already established their acquaintance in London and their proximity to the Communists.

Georg is recorded as deputising for John Peet on the ‘Democratic German Report’ in September 1952, while the latter was on holiday. Peet was a leftist journalist who, while working for Reuters, defected to East Germany in 1950. He wrote a quite amusing memoir titled The Long Engagement (1989). It does not mention Honigmann.

P 146 “Obwohl er in seinem Leben immer wieder Frauen, Freunde, Familie, Wohnungen und Orte verlassen hatte – die Partei verließ er nicht, den ‘stumpfen Kern des Kommunismusʼ hat er doch nicht wahrhaben wollen.ˮ

Even though he had during his life abandoned again and again women, friends, residences and localities, he never left the Party, while at the same time he never wanted to acknowledge the ‘indifferent heart of Communism’.

He was free to abandon his women, but not the Party. His daughter should have known that.

P 151 “Damals wusste ich noch nicht, dass die letzte Frau alles der Stasi zutrug, und ich weiß auch heute noch nicht, ob Georg davon Kenntnis hatte oder es gar tolerierte.ˮ

I did not know at the time that his last wife reported everything to the Stasi, and I still do not know to this day whether Georg knew about it, or even tolerated it.

His fourth wife (born 1930) was Liselotte Honigmann-Zinserling (née Bandow), an art historian, who died in August 2021. She must have been sucked into the Stasi information-gathering net.

P 155 “Als Deutscher bekannte er sich, er hatte schließlich das zweite ‘nʼ in seinem Namen unter den Engländern aufrechterhalten, so war er fűr die Engländer ein Deutscher gebleiben, aber fűr die Deutschen ein Jude. Fűr die Genossen war er zu bűrgerlich, nie űber Herman Hesse hinausgekommen. Fur die richtigen Bűrger war er zu bohèmehaft, er hatte ja nichts aufgebaut, angesammelt oder gar vermehrt, weder Titel noch Besitz, nicht einmal ein geordnetes Leben im einfachsten Sinne hatt er zustande gebracht mit all seinen Ehen und Scheidungen, und wie viel er herumgezogen ist, in wie vielen Wohnungen er gelebt hat, wegen Frauen und wegen Krieg. Er hatte Orte, Adressen und Ehen aneinandergereiht und außer seinen beiden Töchtern und den Bata-Schuhen nichts besessen, und am Schluss war er dann nur noch ein old man in a hurry, wie er seiner Ärztin, die ihn zum Tode hin behandlete, erklärt hat.ˮ

He acknowledged himself as a German: among the English, he decisively preserved the second ‘n’ in his surname, and thus remained a German to them. But to the Germans, he was Jewish. For the comrades he was too bourgeois, and had never escaped the shadow of Herman Hesse. For the real bourgeois he was too bohemian, and had never built, accumulated or created anything, neither a title nor an estate, and with all his marriages and divorces, had not achieved any organized life in any simple sense, no matter in how many places he had lived, because of his wives and because of the war. He had lined up places, addresses and marriages against each other, and beyond his two daughters and his Bata shoes had owned nothing. He was at the end simply ‘an old man in a hurry’, as he explained to his (female) doctor, who treated him all the time until his death.

The expression ‘old man in a hurry’ derives from Winston Churchill. This profile tends to confirm the persona of Georg as something of a ‘Luftmensch’, namely an impractical, contemplative person having no definite business or income. He clearly possessed a lot of charm, but portrayed little backbone, and was easily seduced into the perils of Communism, which really suited him not at all.

Conclusion:

Contemplating the strange interlude in the summer of 1946, when Georg was separated from Litzy when in Berlin, I had hoped to learn from this memoir a little more about his relationship with the NKVD. Yet, almost predictably, he presents a very sanitized picture. He is contradictory and elliptical in his account of meeting Litzy and how he was converted to Communism, and avoids any explanation of the events of 1946. Just as Barbara’s mother declined to reveal from her daughter the truth about her work for the NKVD, so did Georg cloak his activities in vagueness and deception. It was as if the two of them grew increasingly regretful and embarrassed about their service with Soviet espionage and counter-espionage, but did not want to admit how cruelly they had been exploited.

Thus Georg’s role, and his importance to the NKVD, remain very enigmatic. Unlike many other emigrés who found themselves inextricably linked with Communist organizations and movements, he did not appear to have imbibed the red juice by the time he arrived in the United Kingdom. Perhaps his affair with Litzy was truly the event that solidified his allegiances, bolstered by his experiences in Canada. One must imagine that Litzy’s cohabitation with him must have been approved by her Moscow masters, as if it created a distance between her and Philby, and even gave her some tortuous ‘respectability’. But, in that case, why did the NKVD not insist that she divorce Philby, and why did they encourage Georg to draw a lot of attention to himself by consorting with the exile communist groups in London? He was not useful to them in other ways: he had no access to secret information, and he had no role as a propagandist for the cause.

As I have argued before, until 1944 Litzy was probably considered a much more important asset than Philby, who was in semi-disgrace, and had not even managed to secure a position in British Intelligence, when she started to live with Honigmann in 1940. Moreover, they might have believed (incorrectly) that Litzy would lose her residential status if she threw off her legal relationship with Philby. Yet they then involved Georg in the extraordinary clumsy business over the Control Commission post, and the subsequent ‘kidnapping’.

We know from the KASPAR/LAMB reports (if they can be trusted, obviously) that Georg for a while resisted Litzy’s strong appeals to him that it was their duty to move to the Soviet sector of Germany, and that they fell out over the idea. Eventually, Georg must have learned that he had no choice in the matter, and, when he accepted the job, he knew that he was not going to end up in a cozy position in the British sector. Yet it again strains the imagination to understand what the NKVD was up to, having him reside in Berlin throughout the summer of 1946, while Litzy and Philby were left high and dry, perhaps ready to be abandoned. Were they perhaps using Georg as an intelligence source, demanding he explain to them exactly what the loyalties of the other two were before allowing Litzy to join him, and only then approving and engineering a very dubious divorce? They must have received the answer they hoped for, but they left themselves exposed should the very unalert and sleepy MI5 have jumped on the bizarre goings-on. As Litzy frequently remarked (p 96 above): ‘How naive the English were!’

[added December 3, 2023]

Yet perhaps the most provocative feature of Barbara Honigmann’s book is the confusion she shows over her parents’ marriage. As the comments posted immediately after the original publication of this piece indicate, the records on the genealogical site Geni, maintained by her extended family, firmly state that Litzi and Georg were not married, but merely ‘partners’. If that were true, her vagueness about the date of their marriage could be attributed to three possible causes:

- She firmly believed that they were married, but was uncertain of the date (in which case she showed astonishing carelessness in the way she wrote about it, an oversight that her editors should surely have picked up).

- She was uncertain about the regularity of the union, and was putting out feelers to try to receive enlightenment.

- She knew that the marriage was illusionary, and was putting out crude hints that reinforced the fact of the sham.

And if they were not married (Litzi, in her discussions with her daughter, spoke of the marriage as fact, but always reflected an uneasiness about her relationship with Philby, sometimes expressing a desire that they get together again), a chain of logic might appear as follows:

- Litzi was unable to marry Honigmann because she had never been divorced from Kim.

- The very questionable claims made by Philby about a hastily-arranged divorce would thus be undermined.

- The marriage between Eileen and Kim on September 25, 1946 was illegal, took place probably with the collusion of the authorities, and Philby was a bigamist.

- Those facts would give credibility to the claims made by Anthony Cave Brown in his biography of Stewart Menzies that the marriage was fraudulent (assertions that he irresponsibly failed to follow up).

- If the marriage had been shown to be bigamous, Philby would have had to resign from MI6 immediately, and a public scandal would have arisen, thus revealing a number of ugly secrets that MI6 would have preferred to be kept concealed. (Philby denied this accusation virulently, as well he might.)

- It would explain the nervousness expressed by MI5 over the prospect of Litzi ‘Honigmann’ (actually ‘Philby’) returning at some time to the UK, and the consequent retention of HO 382/255, given the effect it would have on the status and emotional well-being of Philby’s children with Aileen Furse, and that of their offspring.

I shall follow up on this line of inquiry in due course.

(New Commonplace entries can be seen here.)