(This post is being placed a day early, as I am scheduled for cataract surgery later this morning, July 30. I have been commanded to ‘avoid reading or computer use’ for four days after the procedure, so I shall not be able to respond to any messages until August 3. In the interim, I shall just have to relax by listening to my Black Sabbath CDs. Inexplicably, the death of Ozzy Osbourne was the lead story on the NBC Nightly News of July 22, in which the entertainment world-besotted broadcaster spent over five minutes lamenting his demise.)

Preface: An observation by a reader prompted me to provide a guide to coldspur posts. Hereon they will be coded according to one of the following categories:

E: Elementary

Safe to read this to the kiddies, or to pass on to Aunt Edna. Nothing risky or inflammatory, and probably of zero historical interest. Very rare: perhaps my post from ten years ago, ‘Surveying Lake Tahoe’ (https://coldspur.com/surveying-lake-tahoe/), is the closest example.

D: Divertive

Some personal memoir, which may border on the saucy. Not to be taken completely seriously, but may contain some social observations of vague merit. See, for example, https://coldspur.com/a-rovin-with-greensleeves/.

C: Congenial

A mixture of pieces, in more accessible formats, which may contain both serious and light-hearted commentary on intelligence matters. Typical examples: my occasional ‘Round-Up’ posts.

B: Businesslike

Serious analysis of intelligence matters, but more exploratory, and designed for the occasional reader not steeped in the topic being covered, or in its background.

A: Advanced

Detailed inspection of topics of some controversy, probably involving close inspection of archival material, and requiring readers’ attention to detail. Only for aficionados and for historiographical posterity. Might induce torpor. Do not read while operating agricultural machinery.

This post, which offers a broad analysis of the contents of the recently released Anthony Blunt Personal File, and then investigates Blunt’s dissimulations over his dealings with Guy Burgess and the events of May-June 1951, is definitely code ‘A’. No figures or illustrations to distract you!

Contents:

Introduction: A Breakdown of the Blunt Personal File

- The Exchanges of May 25-June 1, 1951

A Chapter of Accidents

March and August 1956

Anthony Blunt’s Version

The ‘Confession’

The Wright Era

Interpretation

- Burgess and the Comintern

The Guy-Margy Conversation

Meetings and Statements

A Series of Interrogations

Courtenay Young

Interpretation

- Blunt’s Meetings with Burgess, May 1951

- The Leakage of the Soviet Embassy Files

Conclusions

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction: A Breakdown of the Blunt Personal File

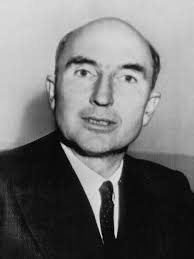

The set of Personal Files on Anthony Blunt (clumsily identified as ‘Blunden’) comprises a challenging opportunity for research and analysis. There are twenty-two of them, KV 2/4700-4722 – with 2/4717 being void – and they contain hundreds of reports, memoranda, and notes to file, as well as transcripts of multiple interviews with Blunt, and others he incriminated, such as Leo Long. I have decided first to process them with a view to determining how Blunt (mis)represented the facts in four critical areas: i) in his description of the exchanges and communications that took place immediately after Burgess and Maclean decamped on May 25, 1951; ii) in his recall of the time when he was approached by Burgess for intelligence, an event that Goronwy Rees re-presented as indicating that Blunt had also been working for the Comintern at that time; iii) in the account of his movements and meetings between the time of Burgess’s arrival on May 7 and abscondment with Maclean; and iv) in his explanation of the way by which Personal Files on members of the Soviet Embassy reached the Russians during World War II.

Blunt was granted immunity from prosecution on espionage charges on the condition that he would give his inquisitors a full and frank account of his exploits working for the NKVD/KGB. This was a shallow tactic, since the officers in D Division had no way of verifying how comprehensive Blunt’s ‘confessions’ would be, and the art historian notoriously fell on the tactic of blaming his fallible memory when conflicts in the evidence came to light. Yet the interrogators were extremely indulgent: before the confession (nominally in April 1964, but in reality in December 1963, as I showed in https://coldspur.com/the-hoax-of-the-blunt-confession-part-1/ and https://coldspur.com/the-hoax-of-the-blunt-confession-part-2/), they also carried on multiple intense discussions with Blunt. Their main objective appeared to be to gain as much intelligence as they could about Soviet subversion and espionage rather than getting him to betray the fact that he had been a spy. Concerned that they might frighten Blunt into clamming up, they were reluctant to press home any advantage they might have had in proving what they strongly suspected. After the confession, everyone seemed to relax, and now that prosecution was off the cards, Arthur Martin continued his pursuit in trying to fill in the gaps about the processes of Soviet recruitment, and the extent of the ‘Ring’. Naively believing that Blunt would sincerely want to contribute to the mission, he treated what Blunt told him with far more respect than it deserved.

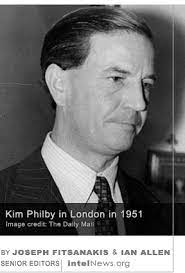

The dating of the contents of the files ranges from 1935 to 1974, with the bulk coming after the confession. The events described are punctuated by external prompts. The initial entries show that Blunt was tracked as a member of a party that sailed to Leningrad in 1935. Several items consist more of records from his MI5 personal file, showing his transfer from Military Intelligence in 1940, and some of his activities working for B1b, and further desultory deeds after the war, when he had been released from MI5. And then the first major external factor is the escape of Burgess and Maclean (p 186 of KV 2/4700 – with the pages reducing in number as chronology advances). While Blunt comes under instant suspicion, the coverage of him is very sporadic, and is interrupted by his departure for a holiday in Greece, and Liddell’s excursion to the USA. It carries on in KV 2/4701 to the end of the year, sparked a little by Milmo’s interrogation of Philby, but then fades away at the beginning of 1952, with Robertson regretfully concluding that Liddell’s closeness to Blunt will probably interfere in the delivery of any rewards.

The next punctuation mark seems to occur in April 1952, and is represented by revealing interviews with John Cairncross (moved to the wilderness after the incriminating information found in Burgess’s flat), and with the ex-Communist Humphrey Slater. In addition, Blunt’ s being threatened with blackmail by Jackie Hewit prompts Robertson to suggest that Blunt be interviewed again. Skardon takes it on, but Blunt continues to be evasive, there is little to go on, and the investigation peters out again by October. Remarkably, very little happens during 1953 and 1954, with Blunt even returning to some measure of respectability. In August 1954, de la Mare, the new Security Officer at the Foreign Office, contacts MI5 about Blunt’s suitability as a nominee for a British Council lecturing job abroad.

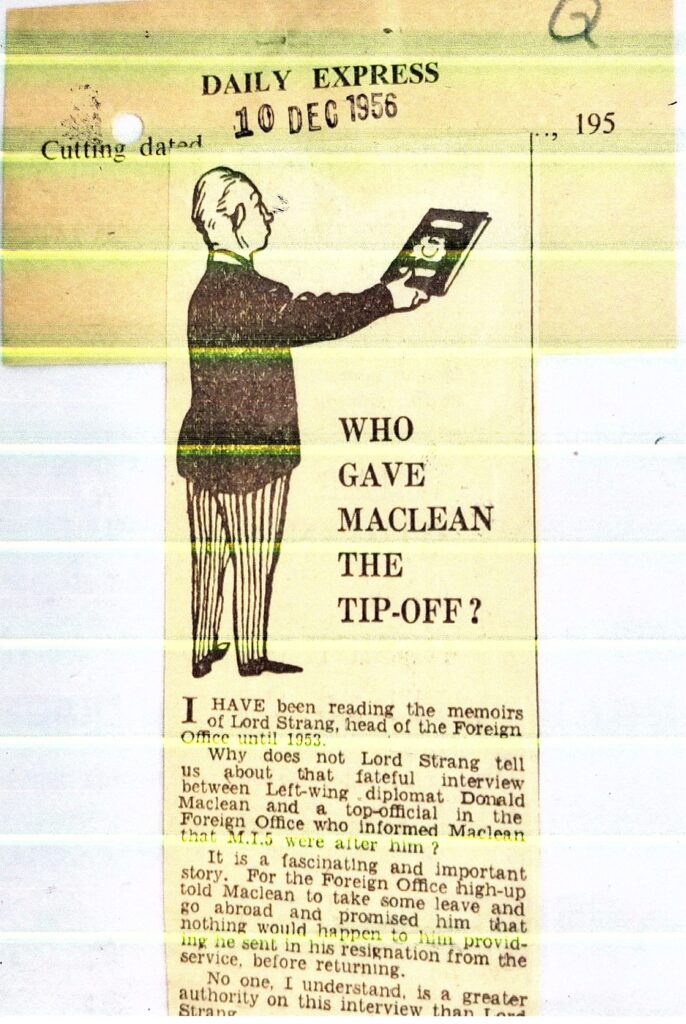

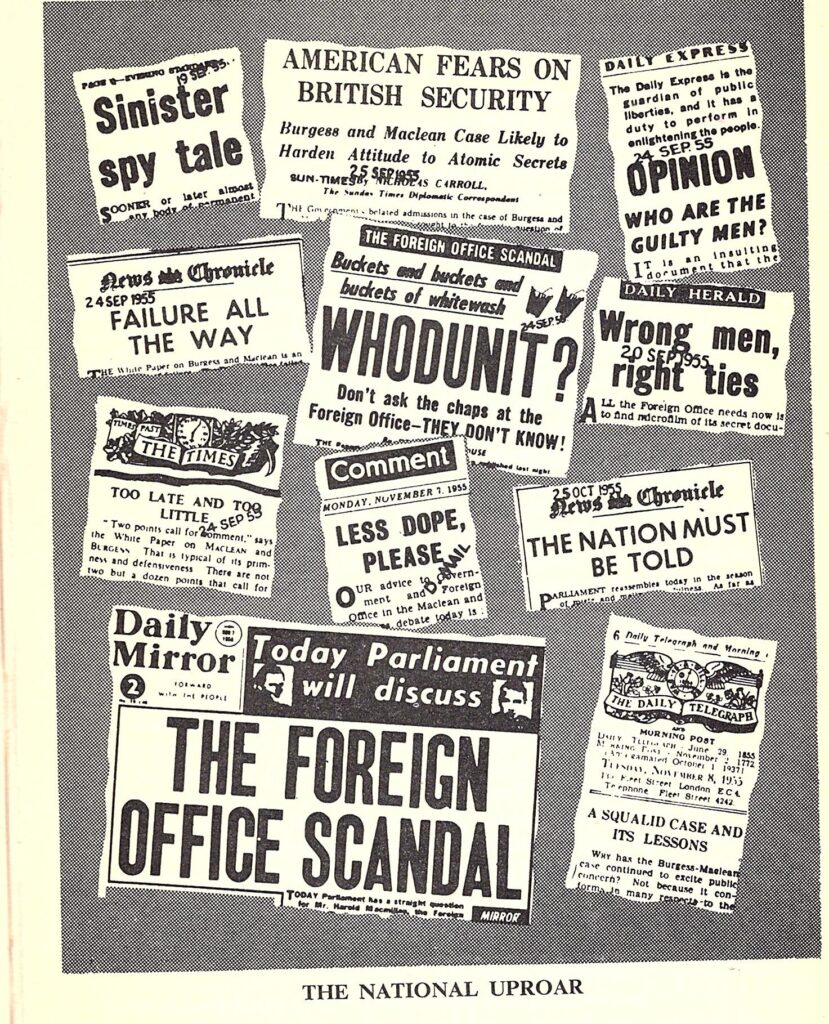

As the archive moves into KV 2/4702, another massive jump takes place, with the expected revelations from the Petrovs on Burgess and Maclean constituting the next punctuation mark, in July 1955. Reed wants telephone checks re-imposed on Rees and Blunt. The Press gets interested, Chapman Pincher becomes excited, and Cyril Connolly (who wrote The Missing Diplomats) has a lot to say to the head of D, Graham Mitchell. Courtenay Young (now D1) enters the story in a big way, writing a long report about his dealings with Blunt over the years, starting with their acquaintance at Trinity College in 1934. At the end of the year, Young makes a strong case for re-interviewing Blunt, and he even hypothesizes that Blunt might be ELLI. Early in 1956, interest is resuscitated by the statements that Burgess and Maclean made in Moscow on February 11. On March 3, D1A has another interview with Rees, inviting him to go over the events of May 1951 again. As another stimulant, MI5 has a glimpse of the notorious articles that Rees had written for The People, and KV 2/4702 closes with some intense inspections of Blunt, including an important long transcript of Reed’s and Young’s interview in May 1956.

KV 2/4703 is restricted to August-October 1956. It is a shorter file, including a detailed examination of the case against Blunt, as well as transcripts of telephone calls between Blunt and Tess Rothschild, Isaiah Berlin, Mrs Bassett (Guy’s mother), Tom Driberg, and others. It is all rather inconclusive, as if MI5 were reluctant to follow up. The year peters out with an interview of Burgess’s friend, and possible agent, Andrew Revai, and, as the archive moves into KV 2/4704, goes unaccountably quiet for a year, until another punctuation point – the possibility of Burgess’s returning to the UK – prompts further flurries in October 1957. The legal aspects of Burgess’s case appear to have drawn the interest of the Attorney-General in Blunt’s situation, and thus MI5 is required to hustle to bring together the records of all the interrogations of Blunt, and to revisit some problematic incidents. Discrepancies between Rees’s and Blunt’s accounts are again noticed. B. A. Hill, MI5’s solicitor, presents Samuel in the Foreign Office with a full dossier on Blunt that he has sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions.

After the Director (Sir Theobald Mathew) decides, on January 7, 1958, that there was no case for justifying a prosecution against Burgess (if he returned), and that likewise it was fruitless taking any further statements from Blunt, Young has another discussion with Blunt about Driberg’s book, and the possibility of Burgess’s return. But Blunt was shortly to leave for an elongated visit to the USA and Mexico, so the summer moves into the doldrums. Indeed, the next punctuation mark seems to occur when the Cabinet discusses the Burgess and Maclean affair in February 1959, although the topic is Burgess more than Blunt. This time Blunt approaches Young, wanting to consider the possibility of Burgess’s return. The remainder of this section is taken by discussions of methods of preventing Burgess’s return, with KV 2/4704 alarmingly breaking off after Blunt is allowed to go on another lecture tour. A few desultory items concerning Blunt’s travels from the years 1960 and 1961 appear, but nothing of substance.

The next major entry is dated July 18, 1962, which reflects an extraordinary hiatus in the career of our hero. This entry refers to the fact that Burgess has made a will, naming Philby as one of the beneficiaries. Another jump represents a fresh, important punctuation mark – Philby’s abscondment from Beirut, as an item dated January 11, 1963, records something that Philby must have said to Nicholas Elliott before he escaped, indicating that he did not believe that Blunt worked for the Russians. A need to know how Blunt might react to the disappearance of Philby activates another warrant for a telephone check on him. This must have been fruitless, because a further bombshell arrives on June 24 – Michael Straight’s admission to the FBI that he had been recruited by Blunt at Cambridge. Evelyn McBarnet acknowledges receipt. At the same time, Anthony Purdey, who has written a book on Burgess and Maclean, makes a private claim that Blunt was the Fourth Man, which is passed on to Malcom Cumming (D). Extraordinarily, no other items for 1963 are posted, as if the news from Straight were unremarkable. We know from other sources what went on with Hollis, Hoover, Straight, Cairncross and Blunt in the closing months of 1963.

Thus the narrative picks up again only in February 1964, describing Blunt’s role as the MI5 officer who was handling the affair of the wartime burglary of a property where members of the Soviet Embassy were residing. R. C. Symonds (D1/Inv.) then gives the game away at the beginning of KV 2/4705 by noting that Straight’s allegations about Blunt have been discussed by D1 and him ‘on a number of occasions since they were first received’ – with none of them having been minuted or filed. Arthur Martin reports his interview with Straight in Washington on February 26, and much of the rest of KV 2/4705 is taken up by the absurd rigmarole of pretending to prepare for Blunt’s confession, and the negotiations with the Attorney-General and the Director of Public Prosecutions. The famous first interview with Blunt, at which he confesses, on April 23, 1964, is reported by Martin in detail, and the remainder covers the aftermath, where Blunt is apparently talking freely, and Leo Long is unmasked.

The remaining sixteen volumes in the file take up the decade after the confession until 1974 – i.e. well before Blunt’s unmasking in 1979. (I cannot do justice here to this enormous tranche, and shall have to return to them at a later date. Yet I consider it will take months and months of intense effort to disentangle them all.) The notorious event marks a caesura in the treatment of Blunt. Up until then, his interrogators suspected him of being a spy, but treated him with kid gloves, as he was under no obligation to speak to them, and they wanted to learn as much as possible about Burgess’s associates. (In one notable memorandum of June 1956, J. D. Robertson remarks on the difficulty of interviewing Blunt without antagonising him!) In that respect they were lenient with his frequent lapses of memory, and the impression given is that senior MI5 officers would have preferred to drop the whole case – until another external event resuscitated interest. After the confession, however, the mood changed. Blunt was initially more relaxed (although he was concerned that the fact of his guilt might come out), and the emphasis of his inquisitors switched more to general fact-finding than detecting holes in Blunt’s story.

And then Peter Wright joined the team, in 1963. Initially he went along with the flow of Evelyn McBarnet and Arthur Martin. Martin, however, fell foul of Director-General Hollis, was effectively demoted, and transferred to MI6 in 1964. (You can read about the rivalries and fall-out in Andrew’s history of MI5 and in Wright’s Spycatcher.) That left Wright in a leadership role, and he took over exclusive control of the interrogations. As he gained in confidence (and his suspicions of deeper rot in the system increased), his curiosity also swelled, and he became more incisive about the flaws in Blunt’s testimony over the years. This worried Blunt, since the terms of his immunity required him to tell all he knew, and he could thus no longer decline interviews. There were added complications. If he were shown to have lied to his interrogators, his agreement might well turn out to be null and void. And, if he ‘shopped’ other agents, would they automatically receive immunity, as well? If not, if they were prosecuted, they might spill beans about Blunt that he had kept tidily packaged away. As Wright gathered more admissions from Blunt, and the network was extended, this problem affected Leo Long, Alister Watson, Peter Astbury, Brian Simon, and others. The political implications affected MI5’s lawyers, too.

For the purposes of this study, the period before the confession is critical, since opportunities for pinning Blunt down on the contradictions in his testimony arose, but were not exploited. Occasional reinforcement of such anomalies appears in Wright’s reports, but it does not seem that he had seen all the previous evidence, as if parts of the Blunt file had been withheld from him. By then, of course, such lies or inconsistences were largely irrelevant, since Wright was seeking his wider goal of discovering broader and deeper infiltration in government departments, and prosecution of Blunt was (practically) a dead issue. He expressed his frustration with Blunt (who in turn threatened suicide or defection if things turned sour), and he stated that he did not think Blunt was delivering on his side of the immunity deal. Yet that was an inherent failing of the hastily concocted agreement.

Lastly, much of the crucial evidence comes from other files (especially the Personal Files of Goronwy Rees and Guy Burgess, but also in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office series, and the MI5 files of the PEACH Inquiry), and a process of triangulation is necessary. Guy Liddell’s Diaries are another extremely important source for investigating validity of statements elsewhere – although they must be treated with caution as well.

The Exchanges of May 25-June 1, 1951

What occurred in the few days after the abscondment has been so distorted in the memoirs and observations of those who played a critical part – Rees, Blunt, Footman, Liddell – that it is difficult to re-create an accurate concordance of events.

A Chapter of Accidents

What Goronwy Rees said when, and to whom, over that critical weekend, is the nub of this case. The most frequently quoted version is that given by Rees in A Chapter of Accidents, published in 1972, when he appeared to have no loss of memory concerning the events of twenty-one years beforehand. After Rees had his ‘absolutely certain, if irrational’ epiphany that Guy had departed for the Soviet Union, he telephoned David Footman. It is worth citing the whole paragraph:

It was now late on Sunday night and I telephoned to [sic] a friend, who was also a friend of Guy’s and a member of MI6, and told him that Guy had apparently vanished into the blue and that I thought that MI5 ought to be told. When he asked why, I said I thought Guy might have defected to the Soviet Union. He was, naturally enough, incredulous, but I was insistent that something should be done and he promised, somewhat reluctantly, that he would inform MI5 of what I said. The next day I received a message from him saying that he had done so and that MI5 would be getting in touch with me.

Rees then goes on describe how he called another (another) anonymous friend, ‘who had served in MI5 during the war, and still preserved close connections with it’ to inform him of what he had done. This friend (Blunt) was extremely distressed, and insisted on coming to Sonning the next day (Monday), where he tried to convince Rees that it was premature to denounce Burgess to MI5. Yet Rees was not to be deterred, even though it was with despondency that he made his way to MI5 the next day (i.e. Tuesday, 30 May), where he had a meeting with an MI5 officer with whom he was familiar (again unnamed). Here Rees goes off the rails, because he telescopes two separate meetings, with Liddell and White, into one, and grossly misrepresents the timing of the event, where the officer (White) tells him that Burgess absconded with Maclean, and when the billboards in the street are already proclaiming the disappearance of two British diplomats. What else did he get wrong?

One might ask other questions. Why did Rees not admit his own part-time work for MI6 at the time? Even more to the point, if his second friend still maintained close contact with MI5, why did he not use that acquaintance to gain rapid access to MI5? What was the point of contacting Blunt, in that case? Why, if he had been working alongside Liddell on the Borodin case as recently as two years ago, did he not try to contact Liddell directly? Why, if he received a message from Footman on the Monday saying that MI5 would be getting in touch, had he already set off for his as yet unscheduled meeting with MI5, and why was the officer ready and available to talk to him? (We know that MI5 and the Foreign Office did not until the afternoon of May 30 acknowledge that Burgess and Maclean had fled together, and White was then immediately despatched to France.)

Apart from Liddell’s diary entries, little from other accounts can be trusted here. The fact that Rees did call Footman is reliable. Footman confirmed it, much later, to Peter Wright in 1965, and Liddell indicates that Footman (unidentified) did contact him, although not until Tuesday, May 29, suggesting it was provoked by Rees’s request. Liddell, however, gives no indication that he responded quickly by calling Rees and urging that he come in that same day (or asking Footman to do the same), but does note in his June 1 diary entry that Rees came to visit him that day – the sole evidence of a meeting that they tried to bury later. That entry is confirmed by a note at sn. 3H in KV 2/4603. (No indication is given anywhere that Blunt accompanied Rees to this meeting, but that possibility should not be discarded completely, and it may have larger implications as this story unfolds.) I have explored the inconsistencies in the accounts of the Rees-Footman-Blunt exchanges, and the fact that the Liddell-Rees meeting on June 1 was conveniently overlooked or forgotten, at https://coldspur.com/an-anxious-summer-for-rees-blunt/, but I shall revisit them here by more closely inspecting what arose from those interviews. What is extraordinary is that it took until March 11, 1956 (after the appearance of Rees’s first scandalous article in The People), for MI5 to challenge Rees on those facts. Ronnie Reed and Jim Skardon visited Rees in Aberystwyth, and Reed’s initial report can be seen at sn. 165a in KV 2/4605.

March and August 1956

Reed starts off by stating that neither he, nor anyone else in M5, had been clear about the events of that critical weekend (May 25-28, 1951), and seeks direction. Rees reminds him that he was away at All Souls College (in Oxford) for the weekend, and that his wife, Margy, had to take the brunt of the troublesome calls from Guy Burgess (on the Friday), and Jackie Hewit (throughout the weekend). Now, however, Rees presents a different story. He claims that, after returning home on the Sunday to hear the account from his wife, he did not call Footman until the following morning, May 28, and then called Blunt, who insisted on visiting him at Sonning that same afternoon, and tried to dissuade Rees from telling the authorities about Burgess’s statements in 1937. Rees then stated that, after their intense discussion, he subsequently received a call from Footman asking him to go to MI5 on the Tuesday afternoon (May 29). This is clearly impossible if Liddell’s testimony that Footman did not call him until Tuesday can be relied upon. No indication of Rees’s speaking to anyone at MI5 is chronicled before Liddell’s statement of June.

No matter. Rees says that he went into London on the morning of May 29, where he first went to Blunt’s flat. Blunt tried to talk him out of going to MI5 (which would have been a bizarre outcome, if Liddell in truth had been urgently looking forward to seeing him, and would have drawn suspicion on Blunt.) In spite of Blunt’s protestations, Rees expressed his commitment to going ahead, but Blunt insisted on accompanying him – to a meeting that did not take place. Why Rees simply did not say: ‘You are not invited, Anthony’, is not clear. Reed was sharp enough to point out the anomaly, reminding Rees that Footman did not make his report until 11 a.m. on the Tuesday. Yet the tale becomes even more absurd. According to Reed, “REES said that he found that extremely interesting as he had never understood why there had been 24 hours delay on the part of M.I.5 before they had taken his story, for he had assumed that it would be of considerable importance and we should have wanted to hear it immediately.”

Yet this was a blatant contradiction. Rees had just claimed that Liddell had shown extreme interest, by asking him to turn up the very next day! Yet Reed fails to spot the anomaly (nor does anyone else reading his report, it seems), nor does he follow up by asking what happened when he and Blunt presumably turned up at Leconfield House to see Liddell, since there was no record of the meeting. In a memorandum to his boss dated March 16, Reed writes of Blunt’s visit to Sonning, adding: “He again tried to dissuade REES on the Tuesday morning prior to REES’s appearance at this office”, overtly confirming the appointment, and the general awareness within MI5 of what transpired. He confirms the 24-hour delay before the Security Service became aware of his claims, but the next two lines of his note have been redacted. Was he relying solely on what Rees told him, without performing any verification? It seems absurd.

Moreover, in Skardon’s separate report of the encounter, he writes how Rees was concerned lest any of what he was telling the pair got to the ears of Blunt. “You do know that Anthony BLUNT endeavoured very hard to dissuade me from coming to your office with information about the disappearance of BURGESS on 29 May, 1951?”, he records Rees as remonstrating, implying that he did nevertheless accomplish his objective. Both Skardon and Reed are blithely unaware that no visit occurred that day: at least they do not challenge that assertion. A ‘Sequence of Events’ is then presented in the file, omitting the phantom meeting of May 29, and barely recording Rees’s cataloguing of calls on Monday.

Having done some homework, Skardon and Reed confronted Rees again on March 21. They immediately challenged him (justifiably) concerning his claim that he had come to MI5 within forty-eight hours of his return home on May 27. They pointed out that MI5 had not received information from him about Burgess’s work for the Comintern until ten days after the disappearance. That was when Rees and Blunt had their critical confabulation with White. They reminded him, also, that Blunt and Harris had visited MI5 on May 30, and that Rees ‘had got in touch with Captain Liddell’ on Friday June 1, after which he had reconstructed the Guy-Margy call in writing. For some reason, Skardon and Reed did not consider Rees’s recorded ‘contact’ with Liddell as evidence of an earnest endeavour, amazingly pointing to the fact that Rees’s written reconstruction of the telephone conversation did not arrive at MI5 (via David Footman) until June 6. They thus assumed that Rees and Liddell spoke about nothing else than the bare bones of the Margy-Guy conversation, but then obstinately insisted, again, that his ‘telephone call’ to Liddell was made solely to determine why MI5 had not invited him in.

Rees was forced to backtrack, and blamed his mistakes on his faulty memory, thus annulling all the nonsense about seeing Blunt in London and going to visit Liddell, and finessing the meeting that he had had with Liddell on June 1. He naively stated that ‘due to the passage of time he had firmly imagined that the events that took place had occurred within twenty-four hours’. The fact that he and Blunt did not have any meeting with Liddell that could have been transposed in time was not noticed by MI5’s sleuths. He repeated his claims that the calls to Footman and Blunt occurred on May 28, as well as the visit by Blunt to Sonning, but (since he was not asked about it) neglected to mention the spurious visit he had earlier claimed to make to London on May 29. In fact Reed helped him, suggesting that Rees had made the call to Liddell on June 1 as he had not heard back from MI5! Yet Rees then said that he could not remember the call, but ‘presumed it was so’. (It is at this stage a weak and selective ‘Sequence of Events’ was created, reflecting Rees’s current version of his story. It does not bear an author’s name, but looks as if it was produced on the same typewriter that was used for Reed’s March 26 report of the interview.)

The farce continues, since Reed then reminds Rees that he should acknowledge that ‘far from having told the Security authorities about Burgess’s Comintern work immediately after the disappearance he had in fact delayed ten days before doing so’. There is no record of Rees’s protesting this, but all parties agreed that he had alerted both Footman and Blunt to the accusations (whether on Sunday or Monday), and had furthermore ‘been in contact’ with Liddell on June 1, after which he was invited to write a report on his assertions. (Reed completely forgets the phantom meeting Rees had claimed for May 29.) Why would Rees so weakly cave in to Reed’s allegations unless he recollected how he must have been cowed by Liddell in the physical meeting he had with him, and thought it better to leave that particular sleeping dog lie still? Until, of course, he attempted to reframe the narrative in A Chapter of Accidents, when his memory miraculously returned to him.

A curious coda appears at sn.260b in KV 2/4606, dated August 17, 1956, not initialled, but probably from Skardon, who had just interviewed Blunt in the wake of the People business. (It is annotated as being an extract from a note in Blunt’s file, PF 604582 sn. 221a from August 17, 1956, later to be released as KV 2/4703.) Skardon tells Blunt that he saw a conflict in the testimonies of him and Rees concerning the visit to Liddell, and admits that one of them must be lying (and he tells Blunt he is inclined to think it is Rees). Here Skardon famously observes that ‘either Blunt was a liar, or Rees was’, thus rather artlessly overlooking the strong possibility that both could in fact have the habit of telling fibs. After Blunt produces some ridiculous rigmarole about a dinner some weeks after the disappearance (which makes no sense at all), Skardon writes: “He did say, however, that he mentioned the matter to Captain Liddell. He (Liddell? Blunt?) thought that it was possible that REES had muddled up this conversation with the conversation at Sonning before their first interview with Captain Liddell and thus produced the result as known to us from REES’s statement.” Yet this is further nonsense. Rees and Blunt never had a meeting with Liddell. It was Blunt and Harris who visited Liddell on May 30. Rees met with Liddell alone on June 1. Liddell went on leave on June 3. Rees and Blunt met with White on June 6.

[Another oddity concerning these items is that, despite the clear annotation, the text in the Blunt file and that in the Rees file do not correspond, with different numbering schemes, and different points made. This is mysterious, and worthy of investigation another time.]

Anthony Blunt’s Version

Since the next interrogation of Rees did not take place until almost a decade later, it is probably wise to step back and to record what Blunt said about the events. (It would also be desirable to learn what David Footman said: he was clearly interviewed, but his PF 604589 has not been released and his name is usually redacted from current reports, although one or two fragments from his interviews appear in other files.) The first serious attempt to pin Blunt down on the events of the weekend seems to have occurred only on May 15, 1956, at the height of the People scandal, after Rees had been re-interviewed. The full transcript appears at sn. 205a in KV 2/4702, and it makes depressing reading. Courtenay Young (who had been working in Australia in 1951, but happened to be in the UK on leave – or so he claimed: other evidence suggests that he had come back permanently in March 1951) and Reed (who had executed the search of Burgess’s flat alongside Blunt) carried out the interrogation, occasionally getting in each other’s way. What is extraordinary is Blunt’s ability to mumble through his answers to the questions, and attribute his vagueness to faulty memory. One small item that is gripping is a comment which Blunt, as he attempts to remember what happened, throws out at the outset concerning ‘what he said at the time’ (namely about the Friday morning when he last saw Burgess). I can find no record of an early interview in which Blunt was asked to give his version of events. [If anybody finds such, please let me know.]

Yet it is impossible to believe that, five years later, Blunt could have blotted out so completely the details of some seminal events. Reed and Young tried to construct the timetable. To the degree that it is possible to present something coherent about Blunt’s ramblings, I lay out a rough synopsis of the statements he made, and the context:

- He vaguely recalled that Burgess rang Margy or Goronwy Rees on Friday, May 25.

- The next he heard about Guy was from Jackie Hewit and Bernard Miller. Miller came round around noon on Saturday, somewhat hysterical, asking what had happened to Guy. Guy had cancelled his planned trip on the Falaise with Miller in order to help ‘a friend in trouble’.

- Blunt claimed that Miller had contacted the police on the night of May 25 because his friend had not turned up for their date. The police did not take him seriously.

- Jackie Hewit rang Blunt while Miller was there, also in hysterics, concerned that Guy had not returned on Friday night. Blunt tried to calm them down, as Guy’s being absent for a while was not unusual.

- Over the weekend, nothing much happened. [!!] Hewit rang Goronwy or Margy, probably on Saturday afternoon.

- Blunt probably saw Hewit again over the weekend. [Blunt is reminded by Young and Reed that Margy rang Goronwy in Oxford. Reed tells Blunt about Margy’s conversations with Hewit, and that Goronwy was concerned about Burgess. Blunt expresses surprise that Goronwy was concerned.]

- When Reed next asks Blunt what happened on Monday, Blunt completely elides any discussions with Rees, and moves on to the dinner party planned that evening with Blunt and Burgess, opining that, if Burgess had turned up for it, all would be well.

- Blunt suddenly recalls that at some stage – Sunday or Monday – he and Miller had gone round to see Tomás Harris.

- They remind themselves that Burgess did not turn up for dinner, and they move on to Tuesday. Reed jogs Blunt’s memory by stating that David Footman called MI5 in mid-morning.

- Blunt then says that he doesn’t think that Footman ‘came into it directly at all’. He has ‘no recollection of any communication’ with him: Reed points out that it was Rees who contacted him. [Blunt specifically ignores the fact of Rees’s call to him, that Rees had informed him that he had spoken to Footman, and of the consequent hastily planned meeting at Sonning.]

- Blunt quickly switches the discussion to Harris. Reed reminds him that Harris called Liddell on the Tuesday evening, and declares his surprise at how interested he was. He supposes Liddell must then have invited him and Harris to see him on the Wednesday (May 30).

- When next asked by Reed whether he was in touch with Rees at all that weekend, Blunt replies: “I don’t rem- . . .I don’t think so”, and diverts the conversation to Hewit.

- Young then persists, asking Blunt when Rees came into the picture, but the two interrogators again show their ham-handedness by looking at their notes, and telling Blunt it was ten days later, on June 6.

- Blunt is extremely vague about Sonning, stating that he went down there at some time, but can’t remember when. He assumes he must have rung Rees at some stage, but gives the impression it happened after he spoke to Liddell.

- Young and Reed show that they are familiar with the Liddell-Blunt-Harris meeting, because they remind Blunt that it was he who guessed that Burgess had absconded with Maclean.

- Reed tries to press Blunt about the date of his visit to Sonning. When Blunt appears bereft of any insight, Reed asks him whether it was the day before he came to see White (i.e. June 5), or was it some days before?

- Blunt mumbles and waffles, until Young interrupts him again, interjecting: ‘Wednesday’. Blunt replies; “On the Wednesday. I should have thought – one might assume it was a probability that it was the Tuesday but I don’t know.” [He must be referring to May 29-30, since June 6 fell on a Wednesday. But see the amendment made later, below.]

- When Young asks whether it was Rees or Blunt who expressed a need to talk, Blunt hesitates, then suggests that it was he. He had been talking to Harris, and they wanted to clear up Burgess’s activities before the war. [The fact that Blunt and Harris were with Liddell on the Wednesday is overlooked.]

- Blunt justifies his reason for wanting to speak to Rees was the need to gather as much evidence as possible for the period before the war, and Burgess’s activities then.

- Blunt could not recall Rees’s reaction to his inquiries, but did state that he produced the Comintern story.

(The conversation then turns to aspects of Burgess’s working for intelligence, which I shall cover under the next question.)

One highly important aspect of this is the fact that Burgess had visited Harris on Thursday May 23. This is explicit in what I call the ‘master register’, in KV 6/145. If anyone thought of asking Harris what he had discussed with Burgess, I cannot find it in the archive. Why Young and Reed had not had access to this gobbet of information, or overlooked it, is a mystery. But it helps to explain why Harris took such an immediate interest in the case, and colluded with Blunt.

The conclusion from all this is that Young and Reed were responsible for an utter shambles. They were ill-prepared, and too chummy with Blunt, they prompted him out of his awkward silences and amnesia, and they missed an excellent opportunity to pin him down. Blunt escaped with telling manifest lies about his exchanges with Rees on May 27 (or May 28), and his visit to Sonning on that latter day. The final report on the interview (sn.207a in KV 2/4702) blandly echoes Blunt’s claim that he had not been in touch with anyone else (apart from Harris) over the disappearance. In the set of interview reports gathered for the Attorney-General in December 1957 (see sn. 265 in KV 2/4704), an Appendix H (which, remarkably, does not appear in the material collected at the time!) states, with much more conviction than Blunt himself ever expressed, that Blunt believed that he must have visited Sonning on Tuesday June 5. It is almost inexplicable.

Young offered his report on June 13. Maybe not completely as an accident or coincidence, Reed had just been removed from D1, and Young, an old friend and contemporary of Blunt’s at Cambridge, was on his own. Young’s account of Blunt’s description of his visit to Sonning runs as follows:

BLUNT said that he and HARRIS had been talking over BURGESS’s past actions and on the assumption that he had flown because he had been guilty of espionage were wondering how far back the trail led. This in turn led BLUNT to go and see REES to compare notes with him. BLUNT said that he and REES agreed to go together to see Captain Liddell as a result of that talk.

All of which is absolute nonsense, of course. Why would Harris and Blunt have considered that Burgess had a track-record of espionage? Why would Blunt believe that Rees would have insights in that area? And why would Blunt then manufacture the visit to Liddell together with Rees, which never happened, whereas he and Harris did have a meeting with him? Why, if Blunt and Harris then decided to visit Liddell, did they not mention any of their suspicions that had presumably tightened after visiting Rees, or Blunt’s ‘subsequent’ visit to Sonning – a fact that could have been verified from the record of the discussion? It is either deplorably lax behaviour by Young, or mischievously misleading. Yet no-one picked up on it. Graham Mitchell (D, to whom Young’s boss, Robertson, reported) commended to Roger Hollis, the Deputy Director-General (whom he would very shortly replace), the ‘pertinacity and skill’ with which Young and Reed had conducted the interview. Robertson failed to notice the anomalies. He and Young continue to trust Blunt’s account of the exchanges more than those of Rees. And Blunt must have marvelled as to how he was able to get away with it.

The ‘Confession’

For many years, little fresh happened. In 1963 Philby absconded from Beirut, and Blunt was induced to give his ‘confession’ after being unmasked by Straight. Blunt had made a characteristically devious statement about the events of May 1951 during his ‘confession’ to Arthur Martin (sn. 355 in KV 2/4705). He claimed that, when Burgess returned from Washington he ‘went straight to Blunt’ (not true, Blunt went to welcome Burgess), and told him that Philby had warned him that the game was up. Burgess had come back to England to help Maclean escape, and he hoped Blunt would collaborate. As a result, Blunt met PETER (Modin), but Blunt could not remember how they had made contact, and assumed that Burgess had arranged it (utter nonsense). “Nor could he remember exactly why he had met ‘Peter’, but he thought he must have been acting for the sake of security as an intermediary between ‘Peter’ and BURGESS”, ran Martin’s report. Martin asked no questions as to why Burgess would have initiated the highly insecure process of reaching out to Modin in the first place. Martin continued: “At any rate he, BLUNT, played no part in arranging the flight although he was of course generally aware of what was going on.” He begged Burgess not to go too: after the flight Modin urged him to follow them, but he declined. Blunt claimed that his last meeting with Modin occurred in June or July 1951 (not true).

This paragraph alone could have been enough to nullify the terms of Blunt’s agreement, but Martin did not follow up immediately. He was more interested in following up other leads (e.g. Leo Long), but on May 20, he carried out another long interview with Blunt, of which the transcript has been kept (sn. 364b in KV 22/4705). Ironically, it is Blunt who brings the conversation around to the events of 1951, since he explains to Martin that Jackie Hewit was not involved at all. Blunt goes on to make the following observations:

- He had no inkling that trouble was afoot before Burgess’s return.

- He received letters from Burgess indicating he was in trouble because of the speeding offences.

- He received a cable – or possibly a letter – from Burgess stating that he was back.

- He checked with Martin to determine whether Burgess came by sea [!]

- He went down to meet Burgess as he arrived on the Queen Mary [having just recalled that he did not know how he had travelled, and that he did not know of his arrival until he received a message]

- Thereafter, he was only in touch with Burgess

- He was due to have lunch with Maclean almost by chance [?], having met him for lunch a few weeks before

- He called Maclean to cancel the lunch

- Maclean told Burgess that he had assumed Burgess had requested him to cancel it

- That was the first indication he had that Maclean knew about him

- Burgess then set up a casual meeting with Maclean at the Foreign Office

- Burgess and Maclean then met several times, more often than they should have

- Burgess had his arrangement for meeting Modin

- Philby or Burgess must have contacted the Soviets in the States to say that Maclean was in trouble

- Maclean was not in contact with his handlers at that time

- The reason that the Russians did not take charge was that they were not in contact with Maclean

- When Martin suggested that the Russians probably instructed Burgess to hotfoot it to London, Blunt claimed that he told him his return was entirely accidental

- Thus, when Burgess made contact with Maclean, the Russians were not aware of his venture

- Burgess had returned with some information for how to make contact: ‘that is certain’

- The Russians were very shy about taking the initiative: they did not want Maclean picked up

- Thus Burgess was in charge, in touch with Maclean and Modin

- Burgess told Blunt he was making arrangements for Maclean’s escape, and that he had been told he would have to accompany Maclean

- Burgess had been alarmed by the Michael Straight encounter in Washington

- Philby had warned Burgess that he was not to go too [Martin does not believe that the Soviets could have ‘encouraged’ him to go]

- Blunt believed that Burgess persuaded the Soviets to let him go [!]

- He admitted that he must have been introduced to Modin by Burgess

- He had stated earlier that the reason was in case he was required to play an active part, but he did not

- He didn’t think he saw Modin more than once

- Burgess told him of the flight plans at the last moment

- He met Modin once or twice afterwards to check on message indications (chalk marks)

- Blunt rejected Modin’s please that he should abscond as well

More follows concerning the events of the weekend, Blunt’s meeting with Liddell, and further rendezvous with Modin. And then the discussion turns to 1956, when Blunt did meet Modin again. It does not appear that this farrago of lies was re-inspected, or that any of Martin’s superior officers showed any interest in following up the anomalies and contradictions in Blunt’s testimony. It was a lamentable performance.

The Wright Era

And then, that same year, Peter Wright entered the picture in a big way. First, Wright picked up the Rees threads. Rees’s telephone had been continuously surveilled, and on March 16, 1965, Wright sent him a letter requesting an interview so that the discussions on the ‘interesting matters’ that Rees had shared with Skardon some years earlier could be picked up. The ‘Interrogation’ (as it is titled at sn. 366c in KV 2/4607, where a full transcript is available) took place on March 19 at the Reeses’ domicile in South Audley Street. Of course, the Reeses knew nothing about Blunt’s confession.

Yet the day beforehand, another interview of Blunt by Wright and Martin had been set up, on March 18. The transcript (comprising forty pages) of this grisly event can be seen at sn. 497z in KV 2/4707, and it shows an extraordinarily incompetent and rambling display by Blunt. It is difficult to perform justice to the complete inanity of the whole performance. He claims that he cannot recall whether Rees rang him, and believes that he did not go to Sonning on Monday, May 30, to see him, placing the encounter later in the week, just before he saw Rees in Oxford, on Saturday June 4. Yet he cannot explain the purpose of that meeting either. He is utterly haphazard on the course of events: he cannot recall why he brought Tomás Harris in. Wright and Martin appear to utterly bamboozled by Blunt’s inability to present any coherent account of the events: perhaps they thought he had gone completely ga-ga by then.

Armed with this bewildering tale, when the Rees meeting takes place the day afterwards, Wright presses Rees to describe for him the events of that weekend again. Wright (who has probably not studied the complete Rees, Burgess and Blunt files, or has had some of them withheld from him), is accompanied by both Martin and a third officer identified only as ‘JP’ – which cannot have made the interrogation process easy, with each officer tripping over the others’ line of questioning, and each bringing different knowledge to the table. Early on, Wright challenges Rees with the charge that he did not contact MI5 for ten days. Rees explains that he called Footman, and then Blunt, but now he states that he told Blunt to come and see him, which puts a very different spin on the notion that Blunt insisted on coming to Sonning. For some reason, Rees is then evasive as to whether he called Footman or Blunt first, but then concludes that he must have called Blunt second, anxious not to do anything behind his back. When he is asked whether he telephoned Blunt after he called Footman, the renowned intellectual from All Souls resorts to such absurd circumlocutions as “I would have thought it was highly unlikely that I hadn’t . .”. He claims that he contacted Footman because he was ‘the greatest possible friend of Liddell’ – a somewhat contentious assertion, by any standard, especially since Rees knew that Blunt was in regular touch with Liddell, and had worked under him in MI5, while Footman was working for MI6. Now Rees makes another change to his story: he tells Wright that he told Footman only that Burgess was missing, not that he believed he had fled to Russia! How Rees thought he could get away with such outrageous nonsense is incredible. Why Footman and MI5 would want to be alerted to such a non-event on a Sunday evening is not explained, nor is it challenged by Wright. And Rees baldly contradicted it all in A Chapter of Accidents.

Rees is then asked how the joint meeting with Liddell [sic!] was set up? “Did Blunt insist on coming with you?” To this, Rees responds that they received separate invitations, again suggesting there was some delay, as he expresses surprise that he had not been contacted earlier. He does not identify the date of the meeting, but the timetable tends to exclude the possibility that Rees was referring to the event following two days after Liddell’s meeting with Blunt and Harris. Again Liddell, describing the contact in his diary, refers solely to Rees. It appears that Rees is talking about the July 6 meeting with White. Nevertheless, the discussion fizzles out here, with Rees rather casually inviting Wright to speak to Margy, whose memory (he says) is better than his.

Accordingly, another meeting is set up a week later, on March 26. After some initial hostility, Margy opens up. She at first casts doubt on the ten-day interval, and suggests that MI5 may have cooked the records. She and Goronwy agree that a meeting could not have taken place within forty-eight hours; in that case why would he have been so upset? It is clear to me that the pair had discussed the matter, and agreed to stifle the embarrassing session that Goronwy held with Liddell on June 1. Lastly, however, Margy suggests that Blunt made the arrangements. At this stage, Goronwy (who was rather the worse for wear after some heavy lunchtime drinking) left the room. And now comes Margy’s unvarnished account of the events of May 27.

It is a little ambiguous. She states that when Goronwy called her on Sunday, he asked her to repeat what Burgess had told her, as if that were the first time he had heard the story. The implication is that he asked her to make that declaration over the telephone, and that he came to the conclusion then that Guy had gone to Russia. Yet in A Chapter of Accidents Rees wrote that they had the discussion on the Saturday morning, and it was only when he arrived home on the Sunday evening that he learned the full scope of Burgess’s diatribe. That may be immaterial. She did make clear, however, that when Goronwy called Blunt, it was at her husband’s ‘urgent request’ that Blunt come to Sonning as soon as possible. That sounds much more like collaboration, and a need to prepare stories, than Blunt’s shock at his friend’s rather clumsy approach, and a desire to talk him out of going to MI5.

Margy’s words are bizarre, as she describes Blunt’s manner when he visited on the Monday: “Shaking like a leaf, but no inkling he was aware that Burgess had gone to Russia.” ‘Inkling’ and ‘aware’ suggest ignorance of the truth, when neither Rees nor Blunt (if they had truly been innocent) could have known for certain whither Burgess had fled. ‘Suspected’ would be a much more natural way of describing it if Margy indeed had not been complicit in the plot and cover-up as well. “Blunt did his best to dissuade Goronwy from telling MI5 all he knew about Guy Burgess, but finally agreed”, she continued. “Agreed”? Did he have a choice? Was it perhaps truer to say that he reluctantly accepted what Rees was about to do? Or did the two hatch up their story then, only for Rees to go behind Blunt’s back? Again, it is all very odd.

As a final reminder of how undisciplined Blunt’s interrogators were, the last interview that Wright and Martin held with Blunt, on Friday June 26, 1965 (see sn. 460d in KV 2/4708) shows Blunt play the absent-minded professor while Wright and Martin struggled to pin down the timing of the events, getting the incidents with Footman and Liddell quite wrong. As shown above, Wright had recently interviewed Goronwy Rees, but had not come to this interview prepared with the facts or the precise questions he wants to ask, with the result that Blunt is allowed to get away with much of his waffle.

Interpretation

What can one derive from these shenanigans? First, I assume that Burgess trusted Rees, and had confided to him the plans for exfiltrating Maclean – and then himself. Rees’s absence in Oxford that weekend may have been coincidental, but it allowed for a built-in delay between Burgess’s emotional phone-call to Margy on the Friday (before they had made their escape), and Sunday evening (when it would have been too late to prevent it). Rees’s claim, echoing Burgess, that it would have been too difficult and contentious for Guy to have had the discussion with him is unconvincing. The account by Goronwy and Margy of the timing of the revelation is similarly dubious. Margy apparently informed her husband on Saturday that Hewit had called her, but she waited until Sunday evening to lay out to him of the full scope of what Burgess said to her on Friday, which one would imagine would be the more significant exchange to report. In his memoir, Rees said that the call lasted only twenty minutes, and that Margy found it difficult to give a coherent account of it. When asked by Liddell on June 1 to write up what the conversation consisted of, Rees had no trouble laying out the full story. He later said that it lasted an hour.

Burgess’s plan, in encouraging Rees to call Footman and Blunt, was presumably to give all three some sort of alibi with MI5 – showing that they were alarmed by Burgess’s behaviour, and believed that he might be making a flit, because of suspicions concerning his past associations with the Comintern. If Rees did indeed call Footman first, he may well have advised him not to call Liddell until he (Rees) had spoken to Blunt, which would explain the thirty-six hours’ delay before Footman did contact Liddell at 11:00 am on Tuesday morning. Rees’s statement that Footman called him back, positively, the next morning (Monday) does not make sense. Contrary to how Rees presented it in his memoir, when he claimed how distressed the unnamed Blunt had been, and indicated that he wanted to see Rees, both Margy and Goronwy indicated in their interrogations that it was at Rees’s behest that Blunt visited Sonning.

Why did Rees want to talk to Blunt – or vice versa? They needed to get their stories straight. At this stage, Rees might have had no plans to shop Blunt directly, but, if he planned to open up the matter of Burgess and the Comintern experiences with MI5 [see below], the awkwardness about Blunt’s apparent role as an informant for Burgess may have come out. That should not have come as a surprise to Blunt, however, since his collusion with Burgess and Modin would have been known in some quarters in MI5, namely by White and Robertson. Others (including Liddell), however, may not have been aware of the extent of the plotting going on. Thus Blunt had to take the initiative. It would have been impossible for him to roll back completely the process of revelation that Rees (and Burgess) had put in motion, but he had to protect himself. After meeting his ally, Tomás Harris, and speaking to Liddell on Tuesday evening, he and Harris went to Liddell’s office the next day, where Blunt (perhaps impetuously and unwisely) suggested to Liddell that Maclean had accompanied Burgess (and had his supposition confirmed). He pre-empted Rees’s probable accusation by reminding Liddell of Burgess’s Marxist past. He probably also discussed Rees’s upcoming meeting two days’ hence, and advised Liddell to be on his guard against some assertions that Rees would probably make.

When the controversial meeting between Rees and Liddell took place on June 1 (the report of which is very abbreviated), Rees’s plans were probably humbled. All that officially came out of it was the record of Burgess’s conversations with Margy, which, since Liddell immediately afterwards departed for his holiday, Rees wrote up and submitted for Dick White before the subsequent meeting with him and Blunt on June 6. If Rees did indeed intend to reveal to Liddell that Blunt was probably a Soviet agent of the same calibre as Burgess, he no doubt received a discouraging response. Liddell would have rebuked him for not bringing up this insight beforehand, especially given that all four (Rees, Liddell, Blunt and Burgess) had collaborated on the Borodin case only two years ago. And Liddell might have pointed out that he knew about Blunt’s occasional contacts with the Soviets: it was part of the disinformation exercise that MI5 had been carrying out for years. Rees would have been advised to lay off and not poke his nose into matters that MI5 was quite capable of handling. And that would explain Rees’s much chastened behaviour for months thereafter, although the resentment over Blunt’s going scot-free would drive him to rash acts a few years later.

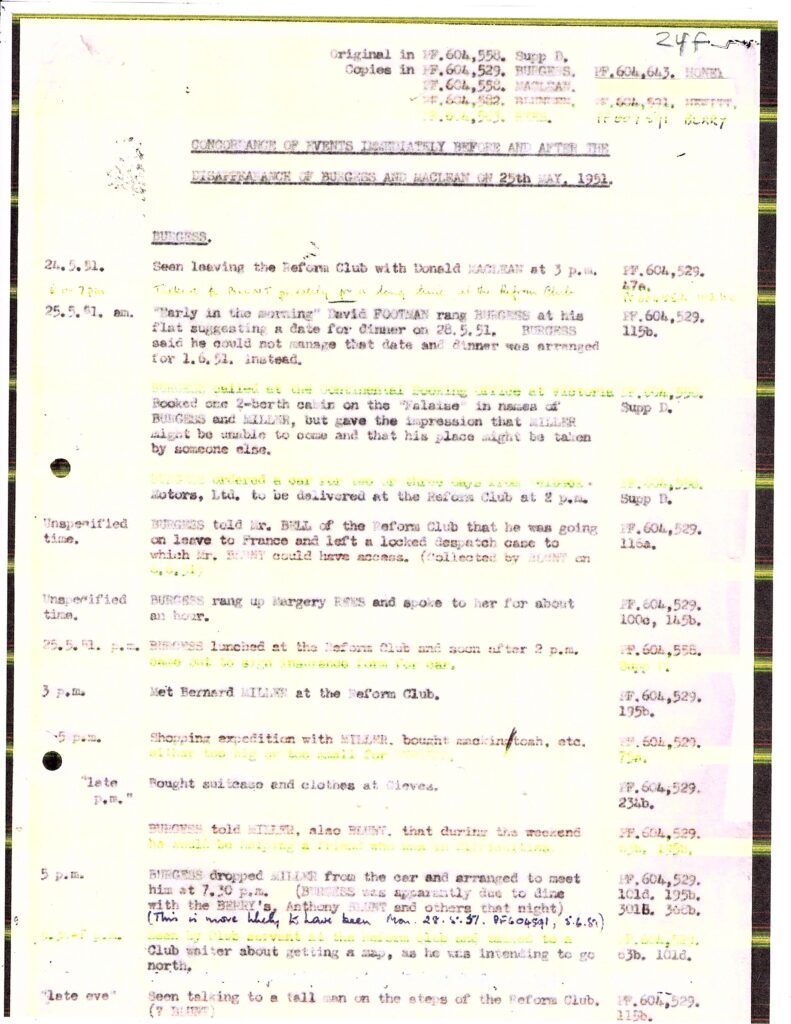

What is also apparent is the utter failure of officers in the counter-espionage Division (B, then D) to apply any discipline to the case. Whereas the Foreign Office constructed a concordance of events around the bigger picture, a detailed chronology of the happenings between May 25 and June 6 concerning Rees, Footman, Blunt, Harris and Liddell was only once attempted, in March 1956 (at sn. 177a in KV 2/4605), and it is by no means complete. While White may have encouraged such inattention while he was in charge, it should have been incumbent on Robertson, Reed, Young, McBarnet, Skardon, Martin, Whyte – and later Wright – to provide themselves with a tightly-drawn chart of telephone conversations, meetings, and individuals’ records of them. As far as I can see, Blunt and Rees were never brought together to face each other with their claims after the June 6 meeting with White, and that gathering was a characteristic Whitean fiasco. Naively, officers like Skardon tried to calculate whether it was Rees or Blunt who was lying – overlooking the fact that they were both unprincipled fabricators.

Despite the obvious prevarications that both Rees and Blunt were engaged in, it seems that Wright could not imagine the enormity of the cover-up that the pair were involved in – namely the stage-managing of the Burgess-Maclean escape by Dick White himself. Wright could not work out why his two slippery customers, at this late stage of the proceedings, could not put together a consistent story, and he must eventually have tired of the manipulation and selective amnesia, switching his energies to the tracking down of the supermole.

- Burgess and the Comintern

The Guy-Margy Conversation

Of course the main item of interest in this imbroglio is exactly when Rees first brought up his experience of Burgess’s admitting that he worked for the Comintern, and the circumstances behind it, and to whom he divulged this information. I confidently conclude that when Rees called Footman (whether on the evening of May 27 or the morning of May 28) he told him of his suspicions that Burgess had absconded to Russia, and why. (Not that either of those pieces of information would have come as a surprise to Footman, but there was a play being acted here.) Likewise, he repeated his suppositions to Blunt, who was even closer to the truth than was Footman. Yet it was Blunt who had more to fear from such revelations being passed generally to MI5.

Before he left on holiday, Liddell said only that the Margy-Guy conversation was ‘sinister’. When Reed put a note on file on June 1, he quoted Liddell as saying it was ‘alarming’, and that that word presumably meant that Burgess may have intended to go to Russia. Rees’s account appears at sn. 7b in KV 2/4703. It is a joke. There is nothing sinister in it: all that Burgess was claimed to have stated that could vaguely have been interpreted as ‘alarming’ is that ‘he would not see [Goronwy] for some time’, and that many people ‘would be shocked at what he was going to do’. The last point that had fallen to Margy (whose skillful recreation of what was presented as a drunken, slurred and haphazard ramble is quite remarkable) was that ‘if G. had come to some decision, he had only just made up his mind and had not made any definite plan’. And Rees came to the conclusion that Burgess had fled to Moscow on the basis of this? He had been defanged by the time he wrote his report. (When this report was later paraphrased, and presented anonymously, by MI5 as Appendix D in the brief provided for Sillitoe’s visit to see Hoover of the FBI (see KV 6/143), Burgess was reported as saying that ‘he was leaving England and would not return for a long time’. That seriously indicates that another version had been prepared by Rees.)

I thus believe that the item as it appears is inauthentic. It looks as if the account of the conversation has been typed up by EJS/R5 on July 16. It has been produced on a typewriter different from that used by Rees to write to David Footman after his meeting with Liddell, undated, but clearly before the meeting with White. Even Reed’s memorandum recording the facts appears to have been entered by the same EJS/R5 on July 16, while Reed has not signed the note in person. Rees’s explanation is far more intense than the account suggests: his fourth point runs as follows:

I think he had come to some important decision you can guess what, but hadn’t decided how to execute it. If this is not so, then it may be still not be too late to prevent him doing something which will give great distress to us all and may be fatal for him, and I therefore hope that every possible effort will be made to locate him.

In no way does the telephone conversation justify such a feverish response.

The document is phoney on several counts: dating, authorship, typescript, context. It is a classic example of an artefact that is Genuine (originating from an authorized office) but Inauthentic (representing a spurious version of reality). It was also delivered with extreme clumsiness. Yet it also shows disingenuousness on Rees’s part: by the time he spoke to Liddell, on June 1, Burgess had already taken his irrevocable and precipitate action, and Liddell, who had already confided in Blunt and Harris that Burgess and Maclean had decamped, must have informed Rees as well. Moreover, Rees asks Footman to show the enclosure to Liddell, who has already left on his holiday. Even allowing for Rees’s clumsiness, I believe that he must have attached a far more provocative account than the one that Dick White must presumably have authorized after the event. White must have sent him back to ‘re-do’ it, properly this time.

Meetings and Statements

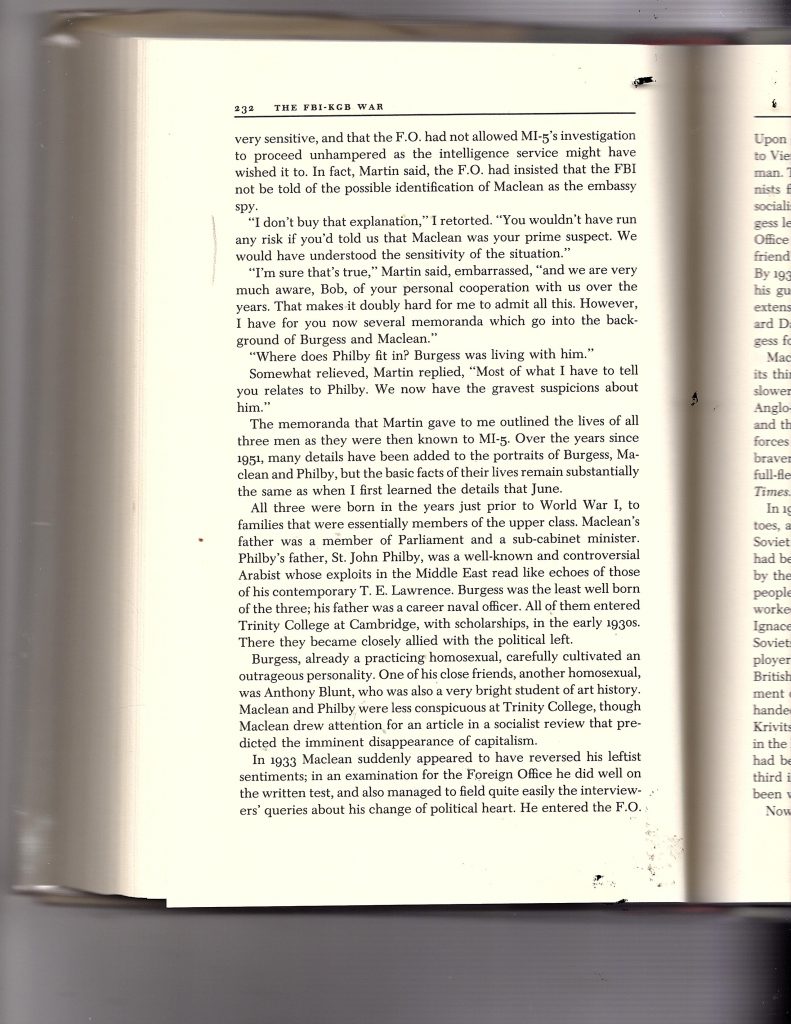

That Rees must have written up some more provocative suspicions is suggested by the meeting that took place immediately after Rees’s report was received. The first exposure of his specific accusations appears in the transcript of the Blunt-Rees-White meeting on June 6 (at sn. 145b in KV 2/4603). The interview was a disaster – incoherent and undisciplined. (Someone has written on the title page: “This is quite impossibly bad, but does contain a few scraps of value.”) There is no introduction. Several pages are taken up by confused talk where the three (mainly White and Blunt) are trying to establish Burgess’s movements and affiliations before the war. Blunt tries to monopolize the conversation, muddying the waters by referring to Burgess’s work for the Joint Broadcasting Committee and Section D of MI6. The Comintern is mentioned. Then Rees tries to set the scene, stating that ‘at that time’, ‘1937 roughly’ Burgess had recently broken with the [Communist] Party, but had admitted to Rees that he was a Comintern agent, and wanted Rees to tell him as much as he could about conversations he heard that would be of interest to Russia. Suddenly he throws out: “. . .he told me . . . Anthony was working for him . . .”.

Dick White pricks up his ears. “Were you consciously doing that Anthony?”, he asks. Blunt simply responds: “No”, and Rees carries on. He suspected Burgess of going to meetings in Paris with Comintern funding. He moves on the Nazi-Soviet pact of August 1939, and that, after Blunt and Burgess returned from Potsdam, he faced Burgess and said that he would have nothing more to do with the business. Burgess replied that he has had the same discussion with Blunt, who had taken exactly the same stance as Rees, and that they agreed to bury the subject. White starts to focus on possible other accomplices, but then Rees brings him back to earth, reminding him of the letter he had written today. (Was that a careless slip-up, or had he really only just written the piece he had claimed to have sent to Footman some days before?) White asks Rees if he thought Burgess had made a clean break from the Comintern in 1939. Rees says ‘yes’, but after Blunt describes Burgess’s mental turmoil as they raced across France to discover the hard news, Rees implied that they disagreed. Blunt grunts sympathetically.

And then White breaks the news. Burgess has dragged in another man at the Foreign Office, ‘a man called Maclean’. (Liddell had obviously neglected to tell White about his disclosures to Blunt before he left.) But White’s mind is moving feverishly, and showing his skills as a superior counter-intelligence officer: “Let’s get to the bottom of them [‘the state of affairs’] – these chaps are on the run together because of something they have done in the past which looks uncommonly like espionage.” White next actually betrays the fact that he is familiar with the surveillance of Burgess that had been undertaken, since he describes Burgess’s discussions with his friends (anti-Americanism, risk of third world war, etc.), and equates them with what Burgess told Margy (which is a bit of a stretch). He then plays the naif, expressing surprise that Burgess should have inveigled Maclean into his thinking.

Rees then expands on his knowledge of Burgess, indicating that he had been working for the Communists ever since he left Cambridge. He states that the business of Guy’s acting as a messenger between Chamberlain and Daladier had Soviet connections. The conversation then drifts inconsequentially, with the assumed whereabouts of Burgess and Maclean being discussed, before White requests that both Blunt and Rees issue some form of statement. Jim Skardon comes in to escort Rees to another room, leaving White and Blunt alone. They dance around the issue, White continuing to pretend that he does not really know what demons were catching up with the pair. Blunt thinks the situation is retrievable. The discussion closes forty-five minutes after it began.

The statements made that day by both Rees and Blunt are available. Rees (in KV 2/4603) describes his associations with Burgess since the latter had become an active communist in 1932, including the time when he appeared to become a right-winger. In 1937, Burgess told him that he had left the Communist Party under direction, and now wanted Rees to help him, since one of his other sources of information was Blunt. Rees lists Rolf Katz and Edouard Pfeiffer as probable sources for Burgess, but then denies that Burgess had ever asked him to provide any information (which tended to contradict what he had just written). He describes the confrontation after the Pact, and reports that, according to Burgess, Blunt had expressed the same objections as he had. Rees describes how he had, untruthfully, told Burgess that he had deposited an account of his dealings with Burgess in his bank, which naturally alarmed Burgess. While he does not explain why, he says that he had believed that Burgess had given up his Kremlin associations at the time of the Pact. Finally, he relates Burgess’s increasingly anti-American opinions, in many letters that he had sent to Rees from the USA, as well as in the visit to Sonning after his return to the UK. He claims that was the last time he saw Burgess (a lie, according to his own testimony later), and closes by referring to the telephone call with Margy.

Blunt’s statement (in KV 2/4700) is terser. He avoids any mention of his providing information to Burgess, but states that Burgess had told him, a year or two before the war, that he was working for an organization that he later believed to be ‘D’ Branch of SIS, engaged in anti-fascist propaganda, and that it was connected to the Joint Broadcasting Committee. Blunt also refers to Katz and Pfeiffer, and even hints that he may have met them. He suggests that Burgess admitted that he had carried information between Chamberlain and Pfeiffer and Daladier, but gained the impression that this had been arranged by Burgess’s employer at the time. He lastly provides a brief snapshot of the time when he and Burgess heard about the Pact (this time they were in the South of France, not Potsdam), and reports that the announcement came as a great shock to Burgess.

The major discrepancy in the reports, namely that Blunt completely skipped the claim about the role that Rees had laid out as an informant to Burgess, was immediately spotted by Reed. A couple of days later, moreover, Reed notes that Blunt had stated that he knew that Burgess had been a Comintern agent – something carefully omitted from Blunt’s testimony, but a conclusion easily arrived at after hearing the transcript. Meanwhile, on June 7, White and Rees had a long conversation, a congenial one, in which they exchanged reminiscences and understandings of Burgess’s cohorts and the influences on his life. They eventually were able to name Klugman, and Rees vaguely incriminated David Footman. White did not press Rees at all on Blunt, however. It seems that Rees knew nothing of White’s plotting to exfiltrate the pair, or his knowledge of Maclean’s and Burgess’s respective guilts, and White played along as the earnest office trying to gather the facts. Later, White would tell his biographer how despicable Rees’s behaviour was at this time, but there is no sign of that animosity here.

The discovery of incriminating letters at Burgess’s flat had earlier prompted further investigation of Blunt, in any case, and on July 7, a note was written asking for White’s approval of a ‘re-interrogation’ (not that the chat on June 6 could have been regarded as such an inquisition.) Reed had made a cryptic note on July 6, stating that ‘in view of the somewhat unusual conversations on the RALEIGH [= Rees] telephone check for the 5th July between RALEIGH, his wife, and BLUNDEN [= Blunt], I have asked today for all the BLUNDEN telephone checks to be re-imposed as soon as possible’. Oddly, there is no record of this conversation in the Rees file, but a possible candidate appears in the Blunt file, dated July 6. The interrogation requested was set up for July 14, and Blunt was invited to describe to Robertson and Skardon his knowledge of Burgess. (It can be seen at sn. 17b in KV 2/4603, and at sn. 27a in KV 2/4700. Interestingly, the Blunt version has been more intensely annotated: on the other hand, it has been redacted more deeply, with information on Revai, Brookes and Pollock visible only in the Rees version, with possibly embarrassing information on Liddell.)

It is a typically devious performance by Blunt. He claims that Burgess left the Party in 1935 because he could not accept the discipline required. He fails to mention his own visit to the Soviet Union in 1935, but states that he saw Burgess only sporadically between 1935 and 1938, when Burgess was working for the BBC in London. He failed to note that Burgess had now become right-wing, and described his political views as still ‘anti-fascist’. He moved on to describe the ‘cloak and dagger’ period of 1937-38 when he admitted he was assisting Burgess in his intelligence activities, innocently, of course, since he had inferred that Burgess was working for British Intelligence. He insists that, until Rees made his statement, he had never heard any suggestion that the work that Burgess was doing was on behalf of the Comintern. He recalls the drive home from France with Burgess in August 1939, but admits ignorance of how Burgess eventually interpreted it all, and that it was from Rees that he derived the fact that Burgess had said that his work for the Russians ceased at that time. He thus effectively denies the discussion that he had serenely glided through with White and Rees on June 6. The rest of what Blunt has to say mainly concerns the war years and after, and sheds nothing controversial.

Blunt was remarkably foolish in what he told Robertson and Skardon. He must have felt confident because he had negotiated some kind of a deal with Rees that allowed him to escape, but he did not know exactly what Rees submitted in his written testimony, and he was surely unaware that the tri-partite talks with White and Rees had been recorded for others to hear. He presumably believed that, since White was his ally, nothing embarrassing would be revealed by what he had said. Yet he had presented no firm objections to the fact that Burgess had explicitly invoked his name as an informant (from what Rees said). Blunt had merely denied, in one monosyllable, consciously helping Burgess. It was surely that laconic response which came back to haunt him, as well as the fact that he made two serious mistakes about the existence of the two institutions, the JBC and Section D of MI6.

Rees was interviewed again on July 24, when Robertson and Martin quizzed him further about his knowledge of and relationships with Burgess. Rees again described how Burgess had approached him in 1937, and admitted being an agent of the Comintern. Burgess had then stated that Blunt was one of his agents, but he did not want Rees to discuss the matter with Blunt – something Rees ignored. Rees let his guard down when he referred to Burgess’s meeting his Russian contacts in Paris, indicating that he suddenly knew that the rendezvous had occurred in Paris when he had disclaimed knowledge before. He also said that he had confided his secret not only with Blunt, but with Rosamund Lehmann, and with his wife. He restated his view that he thought that Burgess had given up his espionage work at the time of the Pact. Arthur Martin (B2b) concluded that Rees was telling just enough to serve as an insurance policy against the possibility that MI5 would discover the facts for themselves.

All this brings us back to Robertson’s memorandum of July 31, 1951, to Dick White, drawing attention to the apparent complicity of Blunt and Rees over their earlier statements, in which Rees gave Blunt an opportunity to deny the assertions that Rees made. Robertson has also noticed the apparent contradictions in Rees’s statements concerning Blunt from the interview with Rees on July 24, although he still holds Blunt to be the guiltier party. Unfortunately, MI5 has not been able to interview Blunt again by this time, as he has left for Greece. (Robertson very oddly does not mention the interrogation undertaken by himself and Martin on July 14.) This is the occasion where the first suggestion of an amnesty for Blunt, if he were to give MI5 ‘with complete frankness every detail of his knowledge of BURGESS’s espionage’ appears. (see ‘An Anxious Summer for Rees and Blunt’ at https://coldspur.com/an-anxious-summer-for-rees-blunt/). Given the sparse information publicly available, one might conclude that Dick White had by now been convinced by this – and maybe other evidence – that Blunt’s explanation of innocence and ignorance back in 1937 did not hold up to scrutiny.

A Series of Interrogations

A few months passed before attention to Blunt began again in earnest. On November 14, 1951, Arthur Martin prepared a brief for an arranged meeting later that day that drew attention to Blunt’s inability to distinguish between events immediately before the war and those a few years before. “One is forced to conclude therefore”, he wrote, “that BLUNDEN drew upon his knowledge of BURGESS’ genuine intelligence activities to cover those earlier activities which RALEIGH declared were for the Comintern; and that he was able to do so because there had been collusion between RALEIGH and himself before they made their statements.” That last supposition might not have been totally accurate, but there is no doubt that Blunt had committed a major faux pas. Section D and the JBC were not created until 1938, and Burgess did not join Section D until October of that year.

Dick White conducted the meeting, and wrote up the report (sn. 69a in KV 2/4701). It had apparently been precipitated by an interview [sic] between Blunt and Harris: Blunt had wanted to alert MI5 to the fact that he was in possession of a further set of Burgess’s papers, the existence of which had escaped his memory. White then started taking Blunt over the Burgess story – when he became a Communist, his break with the Party in 1935, Blunt’s travels with him, his underlying Marxist political views, his view of the Pact – which he justified because Britain had let her down. Yet what White does not do is ask any of the questions that Martin had set up in his brief, namely those concerning the extraordinary assertions that Blunt had made that Burgess had been working for Section D over a year before it was created. It was a characteristically inept performance by White, and it must surely have been noted.

But not by Liddell, who was asked to comment on the report, and could come up only with a lame excuse for Blunt’s explanation about the papers. Yet it took a new voice, that of F. M. Small, of B2a, on March 12, 1952, to resuscitate the case. He laid out a series of questions on which Blunt should be interrogated, including his haphazard recall of Burgess’s employment, and he provided a very comprehensive background report on the whole case. When Robertson was asked by Dick White, in early April, to justify the continuation of the telephone checks on Blunt, Rees, Philby, Harris and Footman, he made a very strong statement indicating that Blunt’s testimony concerning his relationship with Burgess was not believed by the officers in B2. He planned for Skardon to conduct another interview. If White was gently trying to stall the inquiry, Robertson successfully resisted his attempt.