The Book Cover

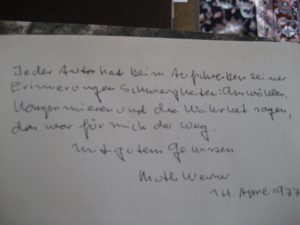

Sonia’s Inscription

A couple of years ago, I bought on-line, from a bookshop in Minneapolis, an item titled ‘Sonjas Rapport’ (‘Sonia’s Report’) by one Ruth Werner. It is rather a drab publication, a fourth edition of 1978, issued by Verlag Neues Leben, in East Berlin. On one of the leading pages, it appears that the author has written an inscription for the buyer. It runs as follows: ‘Jeder Autor hat beim Aufschreiben seiner Erinnerungen Schwierigkeiten; Auswählen, Komprimieren und die Wahrheit sagen, das war für mich der Weg. Mit gutem Gewissen, Ruth Werner. 14 Avril 1977.’ [‘Every author experiences difficulties in recording his or her memoirs: to select, to condense and to tell the truth, that was the approach I took. With a clear conscience, Ruth Werner. 14 Avril, 1977.’]

What is going on here? Is this a hoax? Why would the inscription be dated ‘April 1977’ when the book was printed the following year? A Google search for the sentence is partially rewarding but also frustrating: it seems that this was something that Werner had declared when the book was first published. An occasion to celebrate her 75th birthday (in 1982) reproduces the sentence. See: https://books.google.com/books?id=O3omAAAAMAAJ&q=jeder+autor+hat+beim+Aufschreiben&dq=jeder+autor+hat+beim+Aufschreiben&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiFhoy5653MAhVCdD4KHQujCXEQ6AEIODAE So, Werner presumably thought it appropriate to annotate the volume with her pronouncement, but indicate the date she first said it, at the time of the book’s launch, I imagine. The statement is, however, both anodyne and perplexing. Of course, every memoirist faces difficulties – but was telling the truth one of these challenges? And why introduce her ‘conscience’ unless she had something she was feeling guilty about?

So why did I seek this particular book out? Because Ruth Werner (aka Ursula Hamburger, or Kuczynski, or Beurton: agent SONIA) was one of the most notorious Communist spies of the century. (I direct readers to her Wikipedia entry to learn more about her life and career. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ursula_Kuczynski.) Now, we must bear in mind that the reminiscences of spies are not at all trustworthy, despite their claims to clean consciences and honesty, and Werner’s work was no doubt controlled by Soviet military intelligence, the GRU. Yet I was especially interested in what she had to say, because of my research into Communist subversion in the early part of World War II. For Sonia managed to hoodwink an incompetent MI5 into letting her back into the United Kingdom, after her arranged marriage to Spanish Civil War veteran Len Beurton in Switzerland (by which she gained British citizenship), in the winter of 1940-1941. Soon thereafter, she became the primary contact for Klaus Fuchs, allowing the German Communist (now also a naturalised Briton) to give her atomic secrets for passing on to Moscow, and she started using radio equipment given to her by her London contacts (or maybe constructed by herself) to communicate information to her bosses in the Soviet Union. Falling upon a signed copy of her memoir was quite a coup.

Yet Sonia pulled off this massive espionage exercise when MI5 was completely aware of her political affiliations, and the probable intentions behind her marriage, as well as her relationship with her openly subversive brother, Jürgen, who was interned early in 1940, alongside some of his Comintern friends. Moreover, a couple of years later, in January 1943, a wireless set was discovered at the cottage in Oxfordshire which she was renting from Neville Laski, the brother of the notorious Communist sympathizer, Harold Laski! Yet nothing was done. What was going on?

Now that my doctoral thesis has been submitted, I can turn to some of the puzzling and controversial episodes of communist subversion in the period of the 30s and 40s (and occasionally beyond) that have never been satisfactorily resolved (e.g. Kim Philby’s recruitment, Philby’s relationship with Stephen Spender, Guy Burgess’s protectors, Isaiah Berlin’s relationship with Soviet intelligence, Klaus Fuchs’s Aliens War Service permit, Victor Rothschild’s guilt, the early detection of Leo Long’s espionage, the role of Basil Mann, the death of Hugh Gaitskell, etc.). Why illicit broadcasts from Soviet spies were allowed to proceed unpunished is one of the most perplexing of these challenges. The journalist/historian Michael Smith even claims that, during World War II, a nest of communist spies was overheard discussing plans for the forthcoming war between the Soviet Union and the West. (That assertion must be tested.) Ursula Werner’s ability to remain untouched is part of that enigma.

Most of this story has been told before. One of the best accounts appears in Chapman Pincher’s ‘Treachery’, although the reader must be careful with Pincher’s narrative, as he provides no sources for his multiple claims, and since his goal is to show that Roger Hollis was the Soviet Super-Spy in the innards of MI5, his objectivity and accuracy (especially as regards chronology) cannot be readily trusted. For example, his argument is that Sonia was able to continue to perform untroubled because Roger Hollis and his counter-espionage partner in SIS, Kim Philby, were able to keep the authorities from investigating and prosecuting her. Yet it seems inconceivable to me that those two would be able to pull off such a coup, and convince their masters of the correctness of such a course of action, without drawing obvious attention to themselves. Moreover, MI5 harboured a more deep-seated problem of dealing with Communists than might have been contained in the unbrilliant mind of Roger Hollis.

Wireless and its associated techniques are a complex area, attracting both brilliant and slightly eccentric characters. As George Smiley says, when describing to his colleague Peter Guillam the encounter he had with Karla, in John Le Carré’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy: “We all have our prejudices and radio men are mine. They’re a thoroughly tiresome lot in my experience, bad fieldmen and overstrung, and disgracefully unreliable when it comes down to doing the job.” (Chapter 23). I can’t claim to have a good understanding of the technology involved, but I believe I have learned enough to conclude that the failure to act over Sonia (and maybe other spies at the time) was not a technical problem.

I do know that possessing unregistered wireless sets was illegal, as was using registered sets for transmission. I have learned that, in the first years of the war, the responsibilities for tracking, recording and decoding illicit radio transmissions (as well as messages originating from overseas) were calamitously split between such groups as the BBC, Military Intelligence (in a section called MI8), Section W in MI5, the Radio Intelligence Service and its offshoots (which was a reincarnation of the group within MI8 called MI8(c), and moved to SIS in 1941), and the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS), whose name was changed to Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in 1943. I know that MI8(c) and RSS very much focused their efforts on Nazi wavebands (‘the enemy’), even when the Soviet Union was still an ally of Germany, that is up to June 1941. (Older readers of this blog may be familiar with the BBC 1979 television programme ‘The Secret Listeners’, which described the corps of amateur wireless enthusiasts who aided the effort. It is viewable at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RwbzV2Jx5Qo). I recall that MI5 rapidly claimed, in its promotion of the Double-Cross System, that no unidentified Nazi spies remained at large in the UK, sending radio messages back to Germany, despite the administrative mess. I know that Malcolm Frost, who joined MI5 from the BBC to run Section W, was a very arrogant and ambitious character, and that Guy Liddell (head of B Division, responsible for Counter-Espionage) felt threatened by him. I know that the head of MI8(c) protested the move of RSS to SIS, and that his boss, the Director of Military Intelligence, tried to talk the head of the Security Executive (Swinton) out of it, but that Petrie of MI5 and Swinton forced the transfer through in May 1941. I also know that, once MI5 had declined the offer to take over RSS itself in early 1941, Liddell started being very critical of RSS’s direction-finding techniques and discipline.

But what I don’t know is who called the shots, who made the fateful decisions to minimise the Communist threat and to allow people like Sonia to continue working, even after the defector Krivitsky had warned MI5 of the dangers of Communist infiltrators. I certainly do not yet know what is the source of Smith’s claim that the codes of the Soviet spy network in 1943 had been broken, and by whom, or whether the Joint Intelligence Committee knew what was going on. In the coming months, I plan to dig around relevant papers at the National Archives that are available on-line, various works of intelligence history (which are very contradictory about organisation and responsibilities on these issues), and the memoirs of such as the history don Hugh Trevor-Roper (who worked for RSS). I thus hope to be able to offer a workable hypothesis as to why MI5 – or the government in general – was so indulgent with the Soviet Union’s subversive efforts with illegal radios. Anyone who has unpublished (or published) insights on these issues is encouraged to contact me at antonypercy@aol.com.

Finally, a hint as to the muddle that was MI5 – and at the same time a reminder that it was such a pluralist muddle that we were fighting for in the struggles against the totalitarian states. Readers may recall those wartime films, where the Gestapo homes in on the desperate SOE agent, feverishly tapping out a Morse message on his (or her) radio set, perhaps in an attic in suburban France, hoping that he can complete it before the Nazis, with their goniometric equipment, can identify the location whence the transmissions are made. The Gestapo officers normally burst in just as the operator is winding down. And we know what happens next: the agent is executed – or maybe, after torture, turned to send false messages back to Britain. If the operator does not use a cyanide pill first, or puts a revolver to his or her head.

Guy Liddell’s Diaries report an incident when the German spy Wulf Schmidt, known as TATE, after being maltreated by a brutal Military Intelligence officer, is rescued by MI5 and persuaded to track down where he buried his parachute and wireless set after landing. MI5 sends out its men to Cambridgeshire to dig it up. But they forget to alert the local constabulary of their intentions. As Liddell records it (September 24, 1940): “The worst of it was that the police, L.D.V. [Local Defence Volunteers], etc. have been scouring the country for this wireless set during the last 48 hours. They eventually came upon some people who reported that some mysterious diggers had come down in a car and removed what appeared to be a wireless set. On making further enquiries they discovered that these people were officers of M.I.5.” On another occasion in 1940, Liddell complains that the police are not allowed even to enter any house merely on the suspicion that illicit transmissions may be going on. (Maybe that reminds you of the current ban in Brussels on night-time police incursions into possible terrorist houses.)

Watch this space! I plan to provide the next installment in a couple of months’ time.

P.S. The New York Times fails to learn. Despite my attempt to engage the newspaper a couple of months ago (see Refugees & Liberators), it has not got things straight. In an article on immigration to Germany in its Magazine of April 10, James Angelos wrote: “The scale of the influx last year – roughly one million asylum seekers in all, nearly half of whom made formal applications – was exceeded in German history only by the influx of ‘ethnic Germans’ who were expelled from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union after World War II.”

P.P.S. Again, for those of you who want to contact me, please send your message to my email address at antonypercy@aol.com. If you use the box underneath maintained by WordPress, your message will probably get lost among the literally thousands of spam messages that I have not yet ploughed through. If I have not yet acknowledged your genuine message deposited there, I apologise.

This month’s new Commonplace entries appear here. (April 30, 2016)