Ambler, Waugh and Lord Byron October 1, 2009

I recently bought, in a second-hand bookshop, a copy of Alec Waugh’s A Spy In The Family. I had been looking into the acquaintance that both Alec and his more famous – but less prolific –brother Evelyn might have had with Michael Arlen. I have Waugh’s The Loom of Youth, and Island In The Sun on my shelves, but this title was new to me. The paperback has several blurbs on the cover, including a quote from Life magazine that it is ’the cleanest dirty book ever’, but this edition fails to include a dedication that the author makes in the hardcover edition (inspectable at the local University Library): ‘To the memory of my deeply missed friend Vyvyan Holland, the younger son of Oscar Wilde and very much a person in his own right, as a man of letters and a Bon Viveur, I dedicate not inappropriately this indelicate story that contains no indelicate words.’

I shall not recount the plot here, but the book is fascinating to me because it includes a section of bawdy verse introduced by Waugh, via the character of Victor Trail, as ‘a poem called The Enchantment, that’s attributed to Byron’, something supposedly handed down from generation of public schoolboy to the next. Yet I cannot find any such text on the Web: it does not appear in T.R. Smith’s Poetica Erotica (1923), or any of the anthologies edited by Derek Parker, Christopher Hurford, Alan Bold, Geoffrey Grigson and E. J. Burford that I own. Surprisingly, the book appears not to have been scanned by Google, as a GoogleBooks search fails to locate the piece.

But a search on GoogleBooks for the phrase with which Waugh starts his extract does result in a find – Eric Ambler’s The Light Of Day, published in 1962, eight years before Waugh’s Spy. I have several Ambler titles in my library, including this one. Right at the beginning of the tale, the narrator, Arthur Simpson, states that he attended ‘Coram’s Grammar School, For The Sons of Gentlemen, Founded 1781’, located ‘on the Lewisham side of Blackheath. A friend of Simpson’s had been given the four foolscap pages by ‘a customer at the garage’ owned by his father, and the poem was ‘called the Enchantment, and was supposed to have been written by Lord Byron’. Ambler quotes little of it, only two lines of it in common with the Waugh version, and even those are in a slightly different format.

So what is this Aphra-Behnesque poem? Truly an unrecorded item by Lord Byron? Or does it have another anonymous parent? Is Vyvyan Holland involved somewhere along the line? Did nobody comment when Waugh’s book came out? The poem is more probably a spoof created by Ambler and Waugh, to my way of thinking. (Ambler did not attend public school.) So, if anyone knows more about this item, please contact me at antonypercy@aol.com, or Nigel Rees of ‘Quote…Unquote’ fame, at nigel.rees@btinternet.com . Nigel will shortly be adding it to his list of ‘Latest Quotation Queries’ at http://www1c.btwebworld.com/quote-unquote/p0000112.htm, where it will appear as Q4079.

The texts appear here:

(from The Light Of Day, Arthur Simpson speaking)

“It began:”

Upon one dark and sultry day,

As on my garret bed I lay,

My thoughts, for I was dreaming half,

Were broken by a silvery laugh,

Which fell upon my startled ear,

Full loud and clear and very near.

“Well, it turned out that the laugh was coming through a hole in the wall behind his bed, so he looked through the hole.”

A youth and maid were in the room,

And each in youth’s most beauteous bloom.

“It then went on to describe what the youth and maid did together for the next half-hour – very poetically, of course, but in detail. It was really hot stuff.”

(from A Spy In The Family, Victor Trail speaking)

“I’ve forgotten the first few lines. You must imagine the narrator looking through the window of a chalet on a summer’s afternoon. This is what he sees:”

A youth and maid were in the room,

Were each in youth and beauty’s bloom,

She seemed in age about sixteen,

He full three summers more had seen.

And from the way they hugged and squeezed

Each seemed with other highly pleased.

Their garb was very light, for she

Was only clad in her chemise,

While he, the youth, did also lack

All but one garment on his back.

And there the youth and beauteous maid

Still kissed and hugged, and hugged and played.

At length his free hand wondered o’er

The charms beneath the garb she wore.

Till warming more he bade her lift

Up to her slender wait her shift;

The which she did and there displayed

The loveliest limbs that e’er were made

To Lover’s kindly eye presented.

But he the youth was not contented.

But bade her straightway cast aside

The garb which did her beauties hide.

“’I never bothered to learn the lines describing her less essential charms, shoulders, breasts, navel, legs”. It then goes on:

All these he saw, but fixed his eyes

Most on the part below her thighs.

The only entrance to her heart

Lay like a rosebud set apart.

And this unlike to other girls’

Was yet unhid by shady curls,

But by a down as you might find

Upon the peach’s luscious rind

And still its coral lips displayed

Undimmed by this capillary shade

A tempting prize, yet which to name

You, dear, would say it were a shame.

But still there’s many a blushing miss

Whose fingers try its path to bliss

And in their teens to show their shrine

Will lift waist high their crinoline

For some fair youth to fill with joy

With his easily erected toy

And in return some inches get

Between her open pantalette.

But to my tale: the youth was left

Still gazing at the open cleft

To which his fingers soon did fly

And raised his passions there so high

That casting off his garb he wear

He, too, stood naked like the fair.

And with one arm around, entwined

Felt every part, before, behind.

Nor was he idle for her hand

Grasped something that it nearly spanned

And as it rose she took the dart

Which sometimes almost reached her heart;

And when she did her grasp resign

Her finger’s opened love’s new shrine

To which with meaning full intent

The sturdy uncapped hermit went.

But in her rosy gates he lingers

Detained by her encircling fingers,

Till with sensation dear to wives

Deep in the welcoming cavern dives,

And through and through triumphant goes

Right through the centre of the rose

Till with one last convulsive throe,

She feels love’s burning lava flow.

“There are a few more lines, but I never learned them.”

***************************************************************************

October 30, 2009

After I gave Nigel Rees (of ‘Quote…UnQuote’) my query about ‘The Enchantment’, the bawdy poem attributed to Byron, he soon posted it on his website, under ‘Latest Quotation Queries’. After a few days, he received a response – from one of his sleuths in New York, of all places. This lady had succeeded in googling part of the text and coming up with a ‘Find’ – surprisingly not via Google Books, but by means of the standard search engine. The verses appeared in a volume innocently titled ‘Folk Songs and Ballads: An Anthology’, published, however, by the Cruciform Press in Mexico City, in 1945. (While the complete text of the book was viewable as a PDF, I succeeded in acquiring a copy of it via Abebooks at a price that did not break the budget. Each of the 250 copies manufactured in Mexico City was declared to be numbered, but my copy sadly lacks any identification in the given place.) The collector of the anthology was anonymous, defined solely as ‘The Author of The Limerick, A Facet Of Our Culture’. A small amount of research revealed that this person was someone called A. Reynolds Morse, although this anthologist likewise chose to conceal his name from the Limerick book. Both volumes were suppressed by police action in the 1940s.

Who was A. Reynolds Morse? He was an American, born in 1914, who died in 2000. An industrialist and philanthropist, he is best known for his activity in collecting works by Salvador Dali, and founding the Salvador Dali Museum, which took a permanent home in St. Petersburg, Florida. Reynolds also wrote several books about Dali. But he had pursued other interests, one of which was the publishing of ‘Injection Molding News’, and another (as light relief, perhaps) the libertarian quest to make available to the public items that US publishers were too nervous to print, such as the ‘scandalous’ verses that appear in these two volumes. Unless of course the use of his name is a hoax perpetrated by yet another party…. But some facts would seem to provide evidence that this was his secret pastime. Morse moved to Cleveland from Denver in 1941, and, after his marriage in 1943, started his hobby of collecting Dalis: moreover, the Limerick book was published privately in Cleveland in 1948. According to his obituary in the New York Times, Reynolds and his wife ‘embarked on a sometimes turbulent friendship with Dali and his wife, Gala’ soon after their collecting habit began. Dali was liable to bizarre behaviour, and wrote pornographic letters to his wife, so he may well have encouraged Reynolds’s interests in this sphere.

‘Folk Poems and Ballads’ is subtitled: ‘A collection of rare verses and amusing folk songs compiled from scarce and suppressed books as well as from verbal [‘oral’?] sources which modern prudery, false social customs, and intolerance laws have separated from the public and historical record.’ It was printed ‘for a small number of Experts and Specialists, Scholars, Psychiatrists, Sociologists, and Anthropologists.’ In other words, designed specifically with Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest in mind, and I half-expected to find references to it in the letters between Amis and Philip Larkin. Reynolds also introduces the volume with a quotation attributed to Remy [sic, should be Rémy] de Gourmont: ‘When morality triumphs, nasty things happen’ [‘Quand la morale triomphe, il se passe des choses très vilaines’], and spends several pages of his introduction railing against Puritanism, and proclaiming the cultural virtue of the verses that follow. His overall message reads as follows (note the Popean Capitals): “The False Morality of the Age of Heresy produced the Inquisition, and the Renaissance Resulted. The False Morality of the Age of Faith Produced the Witch Mania, and the Industrial Revolution Resulted. The False Morality of the Twentieth Century produced Sex Censorship, and this Book is therefore Dedicated to THE NEXT AGE OF MAN and to his Eventual Freedom from False Myths, Obscure Symbolism, Incredible Superstitions, and especially from the Intolerable Burden of False Social Customs now Sponsored by THE LAW”. H. L. Mencken would have loved him, although the Sage of Baltimore would have despaired at his Millenarianism.

Reynolds includes two poems that he attributes to Byron – ‘To Rosalie’ and ‘Enchantment’. In his comments on them, he writes that they “came to my attention ten years apart. The former I received in typescript from a girl editor of a college paper who had access to the secret books in the library. The second came to me in verbal form [he means ‘oral’ again, as opposed to ‘in writing’] from an Oxford student who memorized it from a manuscript in one of the college libraries. In many ways the verses are comparable to passages in ‘Don Leon’ and ‘Leon to Annabella’, which length alone excludes from this anthology. ‘Don Leon’ is Byron’s praise of homosexuality, and forms part of the private journal supposed to have been entirely destroyed by Thomas Moore”. Reynolds offers a sample fourteen lines from the work. But experts today appear to doubt that ‘Don Leon’ was written by Byron. It was first published in 1866, and contains references that suggest it was written after Byron’s death. It is frequently attributed to George Colman the Younger. And the doggerel of ‘Enchantment’ suggests that it is more a pale imitation of Byron than convincing parody.

A quick inspection of the two versions will quickly persuade one that neither is the original that we Seekers for the Truth so ardently wish to verify. For example, a single line of a couplet (the rhyme for ‘contented’) is missing in Reynolds’s version: the Waugh version has several anomalies, as well as lines not found in the Reynolds version. They both have the aspect of an oral tradition poorly passed on. So where is the Ur-Text? Which Oxford College holds this work? And how did Eric Ambler and Arthur Waugh really hear about ‘[The] Enchantment’? And why has it never been recorded anywhere else? The mystery is not yet solved.

The ‘official’ text, as it appears in the Reynolds volume, appears below the versions I previously published here.

From ‘Folk Poems and Ballads’ (1945, published by The Cruciform Press, Mexico City)

********************************************************************

November 30, 2014

After a few more years, I received an email out of the blue from a reader in Peru, a Mr. Adrian Geiser, who had come across the poem on my website. He wrote: “I have the poem “Enchantment” written on four pages (each 19.5 x 12 cm in size) which I have had for 50 years. It had been given to my mother many years before that by a friend who in turn had inherited it in England.” After inspecting it, I replied as follows: “I think you have the closest to the original in your hands. After all, Ambler’s account of Simpson does talk about four foolscap pages. . . The version that Morse publishes is, by his own account, based on a version memorised by an Oxford student. And when you compare the two, you can see the omissions and reorganisation of verses. Your version, however, is also a bit clumsy, don’t you think? The scansion is at times horrific (e.g. ‘Designed by Cupid to pierce the heart’), with an odd mixture of masculine and feminine rhymes, and one feels that this was not the secret compilation of a master. Someone with a love of language would not have written: ‘We’ll lay together wholly nuded’ (should be ‘lie’ not ‘lay), and ‘nuded’ sounds Ogden-Nashish. Not sure why your copy would have the ‘Alfred’ of Lord Byron crossed out, but that’s a red herring, I am sure. Maybe it was intended as a parody of Byron, but I don’t know what of. I’ll look around.”

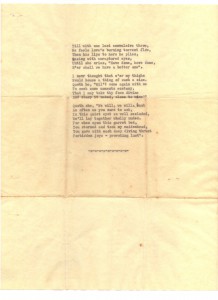

Mr. Geiser was happy for me to reproduce what he sent me on my website, so I reproduce his fuller version here:

(I regret these are not very legible. I shall experiment. I shall also try to post the manuscript version.)

January 20, 2016

I received an email, via Nigel Rees, from Margaret (Maddison) and her husband, Basil Butcher, in Newcastle, England, which ran as follows:

****************************

My husband Basil Butcher, born 1 December 1920 thus now 95, has often quoted scraps of this to me. I have searched for it at intervals without success till now, as he wanted to find the whole poem – so many thanks for your Coldspur blog!

He too believed it was by Byron. He learnt it as a teenager, though he is not sure how, but at the same time as he was given a copy of Robert Burns’ poems which included the more erotic ones. This suggests to me that it was circulated among schoolboys, which he thinks was likely! He was then at the Royal Grammar School, Newcastle upon Tyne, England, a minor public school, which would agree with what Waugh wrote.

Although he cannot now remember the whole poem (and doesn’t recall all the lines you have published), he has always said that it began

‘Twas on a hot and sultry day

As on my garret couch I lay

He remembers the ‘silvery laugh’ and that the writer put his eye to a crack in the wall and saw (though he can’t remember all the lines)

A youth and maid in beauty’s bloom

He had always loved the part

And with a feeling known to wives

Deep in that yawning cavern dives

And through and through triumphant goes

Right to the centre of the rose

I remember that he used to quote ‘the sturdy uncapped pilgrim’ somewhere, though we can neither remember its exact context. After another gap, he recalls the phrase

… though now undone

I never had a sweeter one

So this appears to be another slight variant on those you have identified. Either oral transmission, and/or manuscript transmission does seem very probable. But this does take the poem back another decade to the 1930s.

****************************

It is always a pleasure to hear from people who have stumbled onto the site!

My Father, Leonard J. Halley often recited this poem. As an adult, I transcribed this poem as he recited and wrote out in calligraphy. I was actually working on memorizing the poem! My father was a Newfoundlander who went off to join the R.A.F. in W.W.II. After the war he went to Trinity College and the story goes that the “Poem” was found there unpublished and hidden in the archives. Dad called the poem “Lord Byron’s Enchantment”.

Hallo Coldspur, I have another version of Enchantment (attributed to Byron), beginning Twas on a sultry summer’s day / When on my garret couch I lay. It is written out in hand in the wartime log book of an Australian prisoner of war, sometime between 1943-45. Happy to send scans for your interest, but not for publication as the book is not mine.

I remember this as a note passed to me at school in about 1937. I loved the delicate descriptions – “The ruby entrance to her heart which like a rosebud lay apart” . Happy schooldays !

Dear Sir:

I have a handwritten copy of this poem that I found amongst my mother’s papers that, years later, I am able to go through. I know from her that he was a relative in her family. The pages are really old, tea colored, but the paper is of good quality. It appears to have been written by the old quill nib pen as after so many words the ink would need to be renewed and the following letters are darker than the prior ones. I am missing the top half of the last page. It is not written exactly like your copy and it looks as though it was copied from another one as there are few errors and only a few words scratched through and or changed. It appears very old and while I know that this stuff can be forged, knowing my mother the wayI did, I doubt very much that this is the case with this item. There are 5 pages with the last page torn and only the lower part with the other 4. I am courios about it. I would happily send a photo if you would like to see it. I hope this has piqued your couriosity as well and perhaps tell me something about it. I must say, I love that poem as it is well written, quite descriptive but in a good way, and let’s one ponder for awhile after reading it. I hope to hear back from you.