[This report was updated on July 17, 2023, to include information from reports submitted by Philby to his Soviet controllers in 1945 concerning his visits to Europe, and some brief analysis. The information comes from Genrikh Borovik’s ‘Philby Files’.]

I use this month’s report to address an outstanding question regarding Kim Philby and his actions on taking over Section IX of MI6, namely:

- What was Philby up to in Europe in 1945?

During this analysis, I shall be bearing in mind the subsidiary questions:

- Which of the dates and locations of Philby’s visits can be verified from other sources?

- What authority and what mission did Philby carry at those times?

- What was the strategy of MI6 at the time of these visits?

- How did the activities of Section IX relate to military strategy at the end of the war?

Contents:

Introduction

Histories

Memoirs and Biographies

A Small Town in Germany

Conclusions

Introduction

Kim Philby’s travels in Europe in 1945, described in his memoir My Silent War, may turn out not to be highly significant, but they are worth inspecting because they occurred at a critical time in the post-war evolution of MI6 (SIS), and because his account of them contains some implausibilities. The details are not easily verifiable, suggesting some possible deception. What fascinates me is the fact that Philby’s undisciplined account has, so far as I know, not been challenged anywhere (although it has been distorted). This suggests to me either a) that no one with any knowledge of the background has paid much attention to the anomalies inherent in his account, or b) that it is more convenient to let Philby’s fantasies endure, since they obscure some more embarrassing secrets that the authorities probably wanted to remain concealed.

Philby had only recently (October 1944) been appointed to head Section IX of MI6, which had been established in March 1943, dedicated to Soviet counter-espionage and counter-intelligence. Philby replaced John Curry, who, having been loaned by MI5 to MI6 to lead and build the unit, returned to MI5 in November 1944. Section IX was an outgrowth of the wartime Section V that targeted the Abwehr and other Nazi intelligence groups, in which Philby had led the Iberian section. Such resources and skills that drove Section V’s success were now required for the task of frustrating the Soviet Union’s designs for communist subversion. Philby had managed to persuade Valentine Vivian to give him the job in place of the natural candidate, the diligent but difficult Felix Cowgill, who had managed very well Section V’s operation of Special Control Units embedded with the British Army. Cowgill had, however, made himself unpopular with MI5 because of his reluctance to share decrypted ULTRA intelligence, and Philby skillfully courted his allies (Liddell and White) within MI5 to secure the position.

Philby gave a grudging appreciation of Cowgill’s skills in a report to his Moscow bosses, crediting him with an enormous capacity for work, aided by a prodigious memory, and combative in standing up for his principles. But he had few social graces, was unable to delegate and failed at any task of diplomatic negotiation. Thus Cowgill’s ambitions were quickly snuffed. He returned from a visit to the USA, and a further journey to Germany, in November 1944, and resigned in a huff when he discovered how he had been stabbed in the back.

It is not my intention here to offer a comprehensive analysis of the evolution of Section IX – a difficult enough challenge anyway, given the paucity of sources. Rather it is my goal to provide an accurate context for Philby’s initiatives after he assumed leadership of the Section, thereby shedding light on his movements in 1945, and maybe revealing more about how he was viewed in MI6. It was a critical and sensitive time. As the war began to wind down, and the fresh threat of Soviet expansion in Europe and Communist subversion of the democracies was recognized, a gradual shift in resources took place. Yet the assumption evident in the expressed plans was that the transition from performing counter-intelligence against one totalitarian state to building an organization to thwart the incursions and threats of the Soviet Union would be relatively smooth. That was an analysis that at first failed to register some significant differences.

The strength of Section V had been the successful exploitation of wireless traffic undertaken by German military and intelligence units. Operating on occupied territory, the enemy forces had been required to use radio instead of more secure land-lines. A massive investment in message capture (by the Radio Security Service) and decryption (by the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park) of the so-called ULTRA traffic had allowed Section V (in collaboration with MI5) to build up an extensive map of German units, movements, officers, and missions, alongside information about their deployment of agents. This was supplemented by intelligence gained from air reconnaissance, as well as contributions from citizens of these occupied territories who could provide ancillary information to fill out the inventory. A vital storehouse of data was captured and maintained that helped the Allied military effort.

The situation with the Soviet Union was very different. First of all, it was still technically an ally, and there were factions, especially within the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and in the Foreign Office, who looked forward to cooperating with the Soviet Union after the war. They would have tried to suffocate any plans for expanding Soviet counter-intelligence. Work on the external communist threat had however been sadly neglected during the war, both in MI5 and MI6. Wireless traffic was still very much a closed book. Even though some Soviet messages may still have been collected, decryption efforts had stopped after Barbarossa in June 1941. Not until 1943, when renewed efforts by the exiled Poles at Boxmoor, and a successful project based at Berkeley Street in London, under Denniston, to decrypt ex-Comintern communications in Eastern Europe, was the process of intelligence-gathering resumed. In addition, the Soviet Union was a heavily-guarded citadel: SIS had no agents at all on its territory, and SIS’s officers in outlying stations were known to the NKVD. For example, when Archie Gibson moved from Turkey to Sofia in September 1944, he was expelled a couple of weeks later. What SIS officers (apart from Philby, of course) were not aware of was that details of their complete organization, personnel, and mission had been regularly handed over to Moscow. It was not a level playing-field.

My Silent War (Kim Philby, 1968)

Philby’s own account of his travels is elliptical. He starts: “At the beginning of 1945, when the section [IX] was adequately staffed and housed, the time came for me to visit some of our field stations”, and, after a paragraph complimenting himself on the way that he had repaired the damage done by Harry Steptoe (according to Philby Number 2 in Section IX under Curry – whom Philby spells as ‘Currie’: any writer who lazily follows Philby’s example should be treated warily), with his station commanders universally approving Philby’s decisive sacking of the man, he offers an assessment of the state of counter-intelligence:

Our real target was invisible and inaudible; as far as we were concerned, the Soviet intelligence service might never have existed. The upshot of our discussions could be little more than a resolution to keep casting flies over Soviet and East European diplomatic personnel and over members of the local Communist parties. During my period of service, there was no single case of a consciously conceived operation against Soviet intelligence bearing fruit. We progressed only by means of windfalls that literally threw the stuff into our laps. With one or two exceptions, to be noted later, these windfalls took the form of defectors from the Soviet service.

One wonders whether he presented such a bleak outlook to his bosses at the time: this would have seemed to be no recipe for success, and he would surely have had to present a more positive and energetic front to justify his expansion plans.

He went on to describe his sorties:

These trips, which covered France, Germany, Italy, and Greece, were to some extent educative, since they gave me insight into various types of SIS organization in the field. But after each journey, I concluded, without emotion, that it would take years to lay an effective basis for work against the Soviet Union.

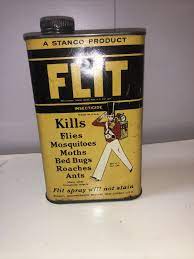

Indeed. He then regaled his readers with a series of anecdotes from ‘that summer’ including ‘the wine-glass of chilled Flit which I drained in Berlin’, under the impression it was Niersteiner, as well as memories from Rome, Bari, and Larissa (in Greece).

My instant reaction on re-reading this recently was one of disbelief, for several reasons. First, the timing is impossible. The implication given is that Philby visited such stations early in 1945. For Paris and other liberated cities, that would obviously have been practicable, but for Germany it would have been absurd, since the Nazi surrender did not take place until May 7. And we should remember that Philby was back in London in August 1945, just before the Gouzenko and Volkov events took place, jarring interruptions that disrupted his peace of mind. In any case, were the outlying stations in previously occupied Europe reconstituted that quickly? And would it not have been easier for Philby to have briefed the station-leaders in London? The second is to do with responsibilities. Since Philby had been appointed to head Section IX only in October 1944, it would have been premature and inappropriate for him to refer to ‘his’ station commanders, who reported to a different section. Moreover, Philby had been with MI6 for only three years, had been working in what was essentially a desk-job (analysis), and had no experience in recruiting and handling agents (operations). The third is to do with MI6’s strategy and organization at the time. I recalled vaguely that a deep study of MI6’s post-war structure and mission was carried out during 1944, with a report not coming out until the end of the year, and that further studies continued well into 1945. Thus the new structure, job definitions, and personnel assignments, as well as the methods by which the roles of counter-intelligence officers would be carried out, would not have been established until several months had passed.

I had to start digging around in the literature. First, the histories.

Histories

The Secret History of MI6 1909-1949 (Keith Jeffery, 2010)

Even though it is not the first, chronologically, Keith Jeffery’s authorized history of MI6 (SIS) was the obvious place to start. In many ways I find this a frustrating volume: it is crammed with facts, but Jeffery dances around the chronology so erratically, preferring to concentrate on exploits by geography, that he misses the chance to offer real integrative analysis. No account of the activities of Section IX in its short lifetime was to be found – an extraordinary omission. I consequently discovered that I had to compile my own interpretation of what decisions were driving what events.

Jeffery judged that the three-man committee under Nevile Bland, chartered with reporting on the future organization of the S.I.S., did deliver, in October 1944, a document that was ‘crucial in the history of the service’. Since this was the same month in which Philby had been appointed to head Section IX, the timing of his career ascent was not the most auspicious. Apart from the controversial recommendation that the functions of SOE be absorbed into SIS, the report seems largely unsurprising, making (for example) the case that that SIS be kept independent of MI5, its tone poignantly echoing the name of its chairman. It did discuss a more professional approach to recruitment, recommended that SIS improve its communications with its consumers, and took on the thorny problem of how SIS officers abroad should be disguised. It emphasized the growing importance of scientific and technical intelligence, and managed to stave off a push by the Joint Intelligence Committee to make SIS more subservient to military needs.

Yet matters did not move quickly, as if nothing should happen until the war were won. Moreover, Menzies wanted more deliberations. Jeffery wrote: “Menzies, in fact, had begun planning for the postwar Service early in the spring of 1945, evidently as a response to the Bland Report, with the C.S.S. committee on S.I.S. organization” being established. This entity consisted of Maurice Jeffes, who had been Director of Passport Control since 1938, Dick Ellis [yes, him who had the dubious past], Bill Cordeaux and Kim Philby. The Committee did not report until November 13, 1945, long after Philby’s reputed excursions around the European stations, and just after the Gouzenko and Volkov episodes, which one might expect to have coloured both the conclusions of the report as well as the formal reception of it.

What this Committee recommended was a wholesale re-organization of SIS, to be divided into four main branches, namely Requirements, Production, Finance and Administration, and Technical Services (which absorbed much of SOE). The largest section of the Requirements Branch was to be the counter-intelligence section, headed by Philby, and Jeffery oddly notes that this section would absorb ‘its predecessor’, Section V, but fails to offer any acknowledgment of the recent birth and presence of Section IX. (Only in an observation concerning 1948, when R5 was split into two, does Jeffery mention Section IX. But Philby had long been despatched to Istanbul by then.) At the same time, the report prescribed some streamlining of the Production Branch, which essentially consisted of the field stations gathering intelligence, and confounding enemy thrusts to undermine them. This new system of five Regional Controllers did not, however, operate until ‘late 1945’. Remarkably, Jeffery offers no names to fill all these exciting new posts (apart from Philby in Requirements, and Wilfred Dunderdale, heading his mysterious so-called ‘Special Liaison Controllerate’), perhaps responding to SIS’s desire for anonymity of its officers.

The adoption of these new structures took place in 1946, and only here does Jeffery inform his readers that the Requirements Directorate came into being that spring under Claude Dansey. Yet that does not make sense. By all accounts, Dansey had retired by then, and he died in 1947. Jeffery eventually lists those who took over responsibility for Production in January 1947 (Sinclair overall in charge, with Ellis, Cohen and Teague as his Chief Controllers). The infrastructure and achievements between the end of the war and 1947 are thus a sorry blur, and Jeffery records nothing about any sorties by Philby into Europe. In fact, almost immediately after he had settled in, towards the end of 1946, Philby was summoned by Sinclair (according to Philby’s account) and informed that it was time for him to have a tour of duty overseas. (Might Sinclair’s decision to move him out conceivably have been provoked by the alarming news of Philby’s bigamous marriage in September 1946? That is something over which Anthony Cave Brown speculated.) Jeffery is completely silent on this appointment, until he reaches 1948 in his saga, when, in an aside to the description of a disastrous exploit to infiltrate a couple of Georgians (the ‘Climbers’) into the Soviet Union, he mentions that they were welcomed in Istanbul by the head of station, Kim Philby. It is all a very unsatisfactory performance by the authorized historian, but he was severely inhibited by the selection of material shown to him.

The Friends: Britain’s Post-War Secret Intelligence Operations (Nigel West, 1989)

At times, the narrative in Nigel West’s account would appear to be describing a different world. As an introduction to SIS’s transition from war to peace, West (who never mentions Bland) refers to the fact that Findlater Stewart, the former head of the recently disbanded Home Defence Executive, was commissioned by Winston Churchill, before he was ousted by Attlee, to recommend how the British Intelligence Services should be organized to meet changing needs. Stewart delivered his report on November 27, 1945. West imputes this study as applying to both MI5 and MI6, and gives as an example for such initiatives as having SIS incorporate the rump of SOE in its organization, including several key officers, such as Robin Brook and Dickie Franks.

What is bizarre about this analysis is firstly that the Stewart report actually concerned itself with MI5 (as the National Archives reveal to us), including only marginal comments about relationships with MI6. Attlee and Petrie negotiated over its recommendations until as late as April 1946, when Attlee signed off on it. Secondly, Christopher Andrew completely ignored the existence of such a report and subsequent process in his authorized history of MI5. West acknowledged at the time that the Stewart report had never been published: it was an imaginative guess on his part to attribute to it the mandarins’ recommendations for MI6, but he had been wrongly informed. Thereafter, West provides a little more detail on the new SIS organization than was to be provided by Jeffery, two decades later.

First, he disposes of Cowgill, without mentioning Philby’s role, describes the continued structure of the Sections, including both V and IX, and introduces three Deputy Directors to Menzies, representing the three services, Cordeaux, Payne and Beddington. Then he starts to coincide with Jeffery, outlining the members of the committee that Menzies established in the summer of 1945, adding Hastings, Arnold-Forster and Footman to the list, but dropping Ellis. The structure of the eventual recommended organization is identical: West states that Menzies approved much of the report, but offers no date. He does identify the nine ‘R’ (Requirements) sections, with Philby’s Counter-intelligence being R5. And he adds the fact that Kenneth Cohen was appointed Director of Production, and that three European regional controllers, Gallienne (Western Area, namely France, Spain and North Africa), Carr (Northern Area, namely the Soviet Union and Scandinavia) and King (Eastern Area, namely Germany, Switzerland and Austria) served under Cohen. (Andrew King had to resign from MI6 in the 1960s for concealing his Communist past; a fact not admitted here by West.).

West spends a fair amount of space in describing the role of Passport Control Officer that continued to serve as cover for SIS officers abroad, despite the fact that it was an open secret. He reveals a surprising fact: that during the immediate post-war period, Charles de Salis and John Bruce Lockhart were manning the SIS station in Paris, and two MI5 officers were also on the staff, namely Jasper Harker (the old chief who was lampooned by Jane Archer), and Peter Hope. This might be relevant in that Paris was one of the stations Philby claimed to have visited, and (as will be revealed) the one with the most solid evidence of his presence.

We can find nothing in West’s study about the activities of Section IX before the reorganization took place, but he does provide some useful information about the Allied Control Council, the entity that governed Germany, the members of which were drawn from the separate Allied Control Commissions. He writes:

SIS had offices in the British Control Commission for Germany (BCCG) at Lancaster House on the Fehrbelliner Platz and requisitioned a building adjoining the Olympic Stadium, where SIS opened a station in 1946. Since the BCCG was eventually to employ a total of 22,520 staff, it was easy enough to provide further cover by attaching SIS personnel to the BCCG’s Intelligence Division (ID), a small unit run discreetly by Brigadier J. S. (‘Tubby’) Lethbridge.

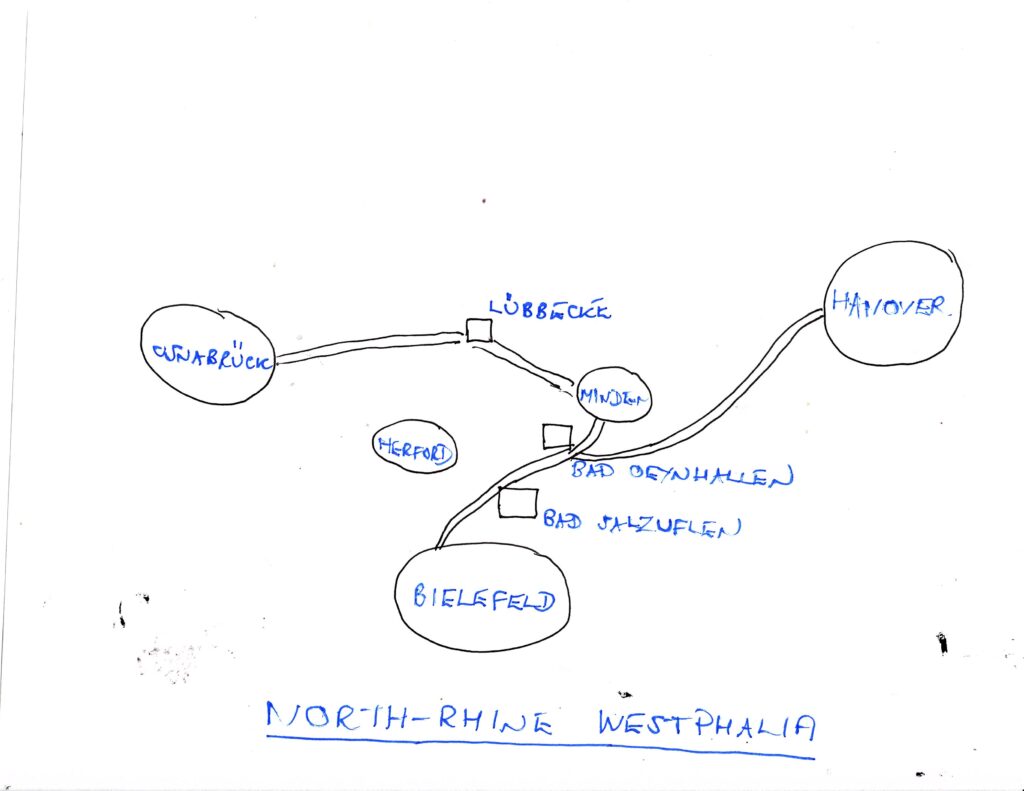

The Berlin connection is interesting: but, of course, it post-dates Philby’s assertions about his travel to that city. West also informs us that, in the year following Germany’s surrender, numerous SIS outposts were established in Germany, the most important being located at Bad Salzuflen, between Düsseldorf and Hanover, under the command of Harold Shergold.

West stresses how important the BCCG was as the frontline of the intelligence war: it was for this group that Dick White of MI5 worked for a year or so, and thereby gained experience and a reputation that helped him in his future career. As West puts it: “ . . . dozens of sites throughout the occupied lands sprang up to house intelligence personnel, train forces, provide wireless interception bases, debrief potentially useful sources and interrogate suspects.” He points out that the focus on denazification, complemented by Soviet-appeasing noises from the Foreign Office, meant that anti-Soviet operations received short shrift, and were frustrated in any case by the communist spy Leo Long, who had been given the responsibility of running agents into the East. Another well-placed spy worked in the BCCG’s Press department, but West was unable to name him in 1989, as he was still alive. While admitting that he had been a Communist, this character denied having spied for the Reds.

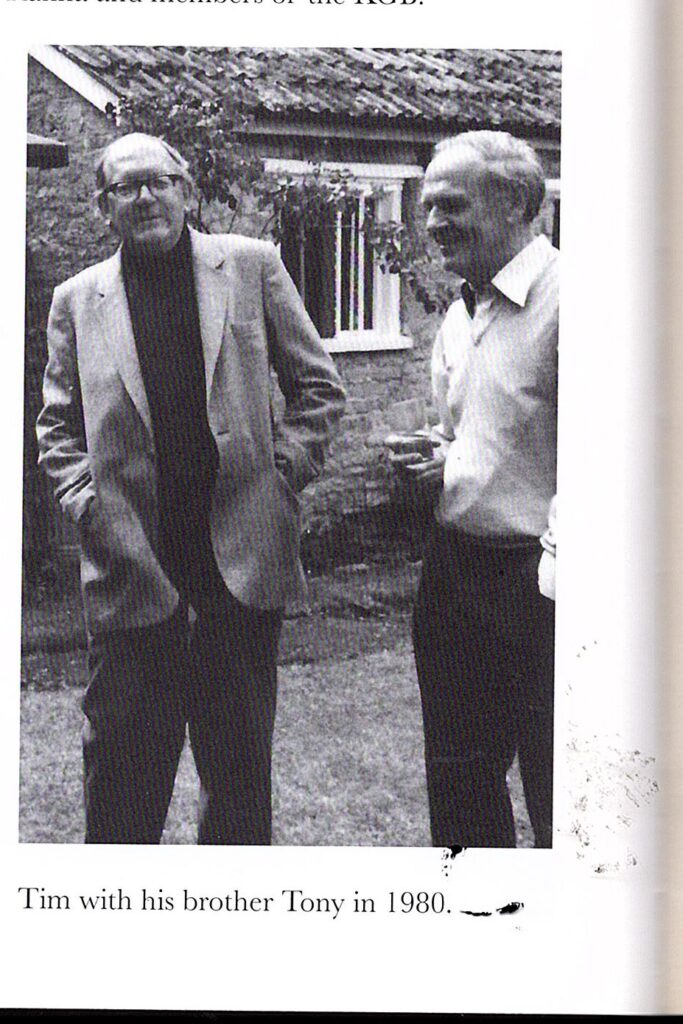

The author dedicates a whole chapter to Philby (‘Kim Philby and VALUABLE’), providing some additional facts. When Philby took over Section IX, he left his Westminster schoolfriend Tim Milne in charge of Section V, ‘which also happened to employ Philby’s younger sister, Helena’. West gets the date of Section V’s formation wrong, stating that it was in September 1944, indicating that Curry and Harry Steptoe led it, when that was in fact the time that Curry gave up the post, and returned to MI5. He does record that Steptoe had been selected to make a tour of the Mediterranean stations to rebuild SIS’s organization after the invasion of Italy, an event that would tend to undermine the fact that Philby had to perform this task again himself. Steptoe later became Head of Station in Tehran, but West provides no dates. One might interpret from these sparse sentences that Steptoe was sent to Iran before he could carry out his Mediterranean tour. West’s narrative here could be interpreted to assert that SIS’s reorganization (where R5 replaced Sections V and IX) occurred before the end of the war. His chronology is distressingly vague.

After providing a detailed exposition of Philby’s career, West returns to 1945. Unfortunately, he relies almost exclusively on what Philby wrote in My Silent War, adding a flourish of his own:

While in his new post, Philby made several sorties abroad during the summer of 1945. He visited France, Germany, Italy and Greece, partly to reconnoitre the facilities that might be available for extending SOE’s covert war against the Soviet Bloc, and partly to indoctrinate SIS’s field personnel into Menzies’ plan for continuing irregular operations into the peace.

Where does this embellishment come from? It is not clear. What ‘facilities’ had to be inspected? What ideas did the unimaginative Menzies come up with for ‘irregular operations’? And what was a counter-intelligence officer doing promoting and explaining plans for subversive operations? And all this apparently occurred before Menzies’s internal study was completed in November 1945. It does not make sense.

Yet West continues the myth. Thus:

Since it was ex-SOE personnel who were going to be expected to spearhead SIS’s anti-Communist campaign in the Balkans, Philby undertook a length tour of inspection. His journey in the summer of 1945 took him to visit Charles de Salis and John Bruce Lockhart in Paris, Monty Woodhouse in Athens and SOE’s outpost in Bari.

Paris would have been a very critical element in Balkan subversion, of course. And what happened to Germany? Moreover, SOE was not formally closed down, and absorbed by SIS, until January 1946. It would have been highly irregular for Philby to be nosing around in sabotage or subversive plans at this time, and Gubbins would have been in uproar. There were no deployable ‘ex-SOE’ personnel in existence at this time. The whole account is nonsensical. ‘The importance of chronology’ raises its head again.

MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service (Stephen Dorril, 2000)

Dorril presents a slightly different time-line. He erroneously has Menzies re-constituting the anti-communist Section IX in March 1944, under Curry, with Philby taking charge of Section V in May, while Cowgill was negotiating agreements with the Americans on intelligence exchange – BRUSA. Philby led a team of 250 officers who performed a valuable task of compiling records on members of the German security services. Before long, however, Valentine Vivian gave him his new assignment:

In August 1944, Philby, who had expected to begin work on the illegal organisations of the Nazi Party and, when the war ended, to work in Berlin as chief of counter-intelligence, was informed that Vivian wanted to appoint him the operational chief of MI6’s anti-communist work in place of Curry.

This came as no surprise to Philby, of course, since he had been manœuvering for it ever since his Soviet bosses told him how imperative it was that he win it. Why ‘operational’ is italicized is not clear.

Dorril goes on to describe how SOE’s demise was arranged, quite quickly, by a committee set up in June 1945, composed of Cavendish-Bentinck, Menzies, Gubbins, and representatives of the chiefs of staff and the Treasury. Gubbins was outnumbered, and accepted the inevitable dissolution of his province as early as July 16, 1945. With the war over, Menzies apparently sent Philby to Athens, and then Frankfurt, ‘where he saw the chief of Allied Intelligence in Europe, General Long’. Thus an apparently genuine confirmation of Philby’s travel appears – but no mention of Berlin. Elsewhere, Dorril appears to accept Philby’s description of his visit to Bari in summer 1945, although he very illogically asserts that this event confirms that SOE was still operational. It was, but Philby had nothing to do with it.

On the other hand, some new intriguing links appear. Dorril frequently refers to Tom Bower’s biography of Dick White for this period – and Dick White was working at the time for Montgomery as chief of counter-intelligence at Bad Oeynhausen, a few miles north of Herford in Rhine-Westphalia. Dorril also reports that that highly dubious character Goronwy Rees – up until the time of the Nazi-Soviet pact an enthusiastic supporter of the Comintern – was also installed there as a person of some influence, senior intelligence officer to Sir William Strang, political adviser to Montgomery. Rees, the character whom Guy Burgess had sought permission to assassinate just a few years ago was now ‘responsible for diplomatic relations with the Russians’.

Dorril, also relying on Tom Bower’s The Red Web (1989), describes how Philby enthusiastically picked up what the old MI6 warrior in Scandinavia, Harry Carr, was trying to organize with Alexander McKibbin – anti-Soviet guerrilla activity in satellite nations like Latvia, Belarus and Ukraine.

As Dorril wrote:

War planning soon became an integral part of MI6’s activities and much thought was given to the setting up of anti-Soviet Stay Behind (SB) networks throughout Europe.

Furthermore, Dorril wrote that Philby was helping with the links to the various exile movements, and was even ‘recruiting among the exiles’.

The archival evidence, however, for exactly what contacts Philby had with such rogues as the Ukrainian nationalist Stephan Bandera in the summer of 1945 is sketchy at best. In his history of the CIA, The Old Boys, Burton Hersh wrote (1992):

It had been Philby’s job all through the postwar months as Chief of Section 9, the Soviet intelligence branch of the SIS, to revise British control over anti-Bolshevik malcontents, and he was quickly in touch with Bandera and his Ukrainians along with the Abramtchik schismatics. Before long the cost of subsidizing these émigré encampments was breaking the English. Unloading ‘the Communist-infiltrated Abramtchik organization upon the all-too-eager Wisner’, Loftus writes, would stand as ‘Philby’s biggest coup.’ ‘Philby also threw in the entire NTS network to serve as the foundation for a Pan-Slavic anticommunist bloc in exchange for access to the intelligence produced.’

Yet this seems to me a mangling of chronology. The author he cites, John Loftus, provided in The Belarus Secret (1982) no archival evidence that Philby was in touch with Bandera at this time, and his text suggests – Loftus is likewise irritatingly vague over his dates – that Mikola Abramtchik (president of the Belarusian Democratic Republic in exile) was not recruited until 1947 or 1948. Nevertheless, Philby was no doubt causing mayhem in many ways already. Such connections and rivalries, and the dampening effect of White’s pragmatism, would probably turn out to be a major influence on subsequent events.

With SOE taken care of, Menzies then set up his Reorganisation Committee (although Dorril presents the deliberations as occurring in October and November 1945). Dorril names the usual suspects, adding Alurid Denne, who, rather improbably, is described as having ‘control of the USSR region’. (Some region: some control.) Philby would indicate that Denne was in fact the secretary to the committee, ‘a careful, not to say punctilious, officer who could be relied on for complete impartiality because he had a comfortable niche awaiting him in the Shell Oil Company’. Hardly the man to cause knee-quaking in the Kremlin. (Dorril attributed the details of his coverage of this committee to West’s book analysed above.)

The outcome, according to Dorril, was similar to that described by West:

Philby was still responsible for supervising the worldwide collection of all anti-Soviet and anti-communist material, intelligence which, according to Philby’s reports to the Soviets, was used ‘to discredit individuals in Soviet embassies and communist activities in other countries, to create provocations against them, to force or encourage them to defect to the West’. A great deal of attention was paid to interrogating former Soviet POWs and other displaced Russians. Philby discovered that the mostly low-level defectors did not know very much about the Soviet Union but were ‘very eager to tell whatever they thought British intelligence officers wanted to hear’.

Dorril here uses Noel Annan (Changing Enemies, p 230) and Borovik as his sources. Yet it all sounds very exaggerated in Philby’s words, and was in reality a poor cousin of what the KGB was actually doing at the time. Indeed, Annan’s message sounds to me antithetical to the sentiments expressed here. Annan wrote, from the page Dorril cited:

It was almost impossible to plant agents in Russia or its satellite states when security was so intense that diplomats were not free to travel where they wished. Yet although the nomenklatura were reluctant to learn that the working class were not starving in the West, the steady stream of defectors, some from the KGB itself, showed that truth did penetrate the Soviet defences.

One yearns for more details here. Who carried out these interrogations – solely Military Intelligence? Were some defectors brought to London? Or did Philby travel to the places where the defectors were detained? And how were the Requirements formulated? What did Philby’s Section IX actually create and distribute in the way of intelligence? Again, details on the work of Section IX are very hard to come by, and the historians try to bluff their way through the fog.

The Cambridge Comintern (Robert Cecil, 1984)

In 1984, Christopher Andrew and David Dilks edited an intriguing set of essays published under the title The Missing Dimension: Governments and Intelligence Communities in the Twentieth Century. One of the contributors was Robert Cecil, who had replaced Patrick Reilly as Stewart Menzies’s private secretary in the summer of 1943, and then moved to the Washington Embassy in April 1945. His essay, The Cambridge Comintern, is notable because he was intimately involved with the creation of Section IX.

Cecil makes some background observations: for example, that ‘contrary to what is asserted by Philby in his book, the Foreign Office had no hand in the manœuvre by which he ousted Cowgill’. When it came to delineate the size and scope of the new anti-Communist section, ‘consultation with the Foreign Office was doubly necessary’, owing to budgetary concerns, and the sensitivities of Heads of Mission who might object to MI6 officers working under their wing. As the intermediary to the Foreign Office, Cecil was given the courtesy of seeing, ‘in late February or early March 1945’ a document written by Philby. It was the proposed ‘charter’ of Section IX. Here Cecil discloses that the proposal described how MI6 officers overseas would be reporting directly to the head of Section IX, and it was couched in language that emphasized the challenges of increased surveillance, and thus the requirement for deeper diplomatic cover. Cecil objected, but was not determined enough:

My vision of the future was at once more opaque and more optimistic; I sent the memorandum back to Philby, suggesting that he might scale down his demands. Within hours, Vivian and Philby had descended upon me, upholding their requirements and insisting that these be transmitted to the FO. Aware of the fact that I was in any case due to be transferred in April to Washington, I gave way, but I have since reflected with a certain wry amusement on the hypocrisy of Philby who, supposedly working in the cause of ‘peace’ (as Soviet propaganda always insists), demanded a larger Cold War apparatus, when he could have settled for a smaller one.

This is a strange passage. Did Cecil simply give way, and pass the document on to the Foreign Office? And did that mean that Permanent Under-Secretary Cadogan automatically approved it? In the absence of any countervailing evidence, one presumably has to accept that Philby and Vivian got their way, and might thus have become carried away with the idea of promoting their mission at stations abroad. The notion that an analytical department head would have officers in stations abroad reporting him seems, on the surface, quite absurd, and would surely have received fierce opposition from the operations leaders. And such a move would fly in the face of the more deliberate approach by Menzies to activate a committee during the remainder of the year to make recommendations on MI6 organization. Menzies would surely have had to approve the foreign travel. Etc., etc. The anecdote does, however, reinforce the fact that Vivian was thick with Philby at this stage, and thus would not have been easily discouraged when the business of the Litzi divorce came up the following year.

Triplex (edited by Nigel West and Oleg Tsarev, 2009)

Perhaps the most remarkable contribution to the investigation comes with the collection of secret documents passed on by the Cambridge Five to their Soviet masters, published as Triplex. What is unique about these items is that they have never appeared in their native English form: they are translations back from the Russian of documents passed on to their handlers by the spies, which were then put into Russian by the NKVD/KGB. It was my old friend Geoffrey Elliott who performed the re-translation, along with Dina Goebbel, and the two of them did an extraordinary job of creating material that appears almost totally accurate and plausible.

Philby has a generous allocation of thirty documents, although, for some inexplicable reason, Nigel West does not present them in chronological order. It is possible, nevertheless, to trace a narrative that shows how the fledgling Section IX found its feet (and wings). Valentine Vivian, with the title of DD/SP (Deputy Director, Security) described the problem of ‘Communist activity’ (XK) in a memorandum of September 6, 1944, and, in an adjacent note, pressed for the appointment of Curry’s successor, and for accelerating hiring, bringing his readers’ attention to the ‘heavy load of investigative and collation work needed to enable PCO and SIS officers to handle operational tasks abroad’. The material needing to be analyzed was probably the ISCOT (i.e. Berkeley Street-Comintern) decrypts, since he referred to the fact that ‘in the subsequent fifteen months’ (since Section IX was created), Section IX had become significantly more effective, and had drawn up a picture of how ‘organised Communism is moving at the present time and its ties with the Soviet government’. He continued: “The staffing of Section IX as a whole needs discussing and then resolving, with an eye in particular to the handling of top-secret material within the section and the changes needed to rectify the shortcomings of CR (the Central Registry).” Vivian then laid out an ambitious scheme for staffing up in stations around the world.

What is fascinating is that Vivian then introduced a very comprehensive paper submitted by Harold Steptoe – ‘22850’s very clear report’. Steptoe had just completed a ‘major swing through the Middle East region to train selected representatives in SIS requirements’ (thus clarifying the vague comments that West made), and Vivian highlights Steptoe as being ‘fully trained’ for the purpose. Philby included the report in his dossier handed over to his NKVD controller, and it makes fascinating reading, showing that Steptoe was a very capable officer who indeed had some excellent insights into the state of the game. Thus, if Vivian thought so highly of him, it is somewhat perplexing why Philby boasted of getting him fired so promptly. (After all, Dorrill wrote that he was moved to head of station in Tehran, which was the job that Vivian sought for him. Philby surely never imagined that Steptoe’s report would ever come to light.) Maybe Philby saw him as a threat, since he had been Curry’s leading man, and had had a solid career in Shanghai as consul. Sadly, Steptoe died just a few years later, on March 15, 1949, at the young age of 56. He suffered a heart attack while serving as the minister to El Salvador. I trust his demise was not suspicious, but in the cases of ex-intelligence officers who came too close to the action, one can never be sure.

At the end of the month, Menzies responded by issuing a memorandum that described the mission of Section IX, and outlined an important directive for overseas work.

In the overseas system the work of Section IX should not be confined to Section V personnel stationed abroad. Although the training and techniques of Section V officers make them the best suited for Section IX operations, nevertheless only Section V officers occupying posts appropriate for the task are to be employed for this purpose.

While clumsily worded, this suggested that not all Section V officers were suitable for communist counter-intelligence, and that, despite the considerable size of Section V, suitable staff would have to be drawn from other sections. Menzies hereby announced that Philby would take over Section IX on October 1, and would be ‘ready to assume executive authority’ by November 13, at which point John Curry would return to MI5.

Somewhat surprisingly, Philby’s impulse (in a report of a meeting that he submitted in December) was to argue against the idea that officers of Section V attached to the military staffs in Italy and France should be used for investigating the Communist movement. He wanted a more careful selection of certain Section V officers to be recalled from other military staffs and first trained for this work (something that I actually suggested, in the passage above, would have been sensible). The other attendees at the meeting apparently agreed with him, identified two officers in Rome and Vienna who were suitable, and resolved that ‘all heads of station should in future receive instruction in this field before taking up their posts’. Whether Philby really wanted the cream of the crop, and how he might go about training such persons, are not clear.

In a memorandum from the month before, to Menzies, Philby had made a very noteworthy recommendation, actually proposing a more pro-active approach to intelligence-gathering, echoing ideas that his predecessor, Curry, had made:

However, recent events and especially the position described in Curry’s memorandum have led me to wonder whether we should not in fact be looking at the problem as an integral part of the military situation, intelligence on which might be of real significance for the foreign secretary and the prime minister in determining policy and which should at a minimum provide reliable and useful background even before hostilities cease and far in advance of the peace negotiations.

While this suggestion would appear to contradict one of the key proposals of the Bland Committee’s recommendations, one can perceive how paradoxical Philby’s situation was becoming: in trying to be more effective in his role, he would presumably be aiding the military cause of preparing for conflict with the Soviet Union. One wonders to what degree the Kremlin internalized this message. At the same time, he may have hoped, by working more closely with Military Intelligence, to learn about plans for conflict in a scheme that would benefit his masters. This initiative may have influenced his travel plans for 1945.

The record for the first half of 1945 is bare. Yet evidence of Philby’s pre-occupations is present in a report that he submitted on July 6, when he described how eight meetings of Menzies’s reorganization committee had taken place over the past month (another important chronological pointer). Menzies was nominally chairman of the Committee, but attended only the first meeting, after which he was represented by Arnold-Foster (sic: actually Christopher Arnold-Forster, Chief Staff Officer). The deputy chairman was Maurice Jeffes, and the permanent members were the naval representative, Colonel Cordeaux (whom Philby respected), Dick Ellis, and Philby himself. Gambier-Parry, Hastings, and Footman were ad hoc members, called upon for specific issues. Philby’s observations on the careers and personalities of all these characters are enlightening, and he gives a detailed account of the resolutions and recommendations of the committee.

One of the most vital insights is the fact that Section IX was designed to become a much more aggressive counterintelligence organization rather than a more passive counter-espionage unit. The distinction is important. Since MI6’s charter was to cover non-British territory (and thus not Imperial domains), the role of counter-espionage would necessarily have been restricted – presumably to the movements of agents of Soviet espionage sometimes operating on alien turf, and efforts to infiltrate British embassies abroad. Philby and Vivian had far more grandiose ambitions: Philby’s paper talks openly of ‘targets’ and ‘penetrating the USSR’. “The whole purpose of the operational regionalization is to facilitate penetration of the USSR from the north, south, east and west.” This was of course a futile gesture, but also a monstrous provocation.

Yet what is puzzling about Philby’s early exposition is that he refers to four directorships – for functions identified as Production, Operations, Administration and Technical Services. This scenario would attempt to grant Production (the division designed for Philby himself) a much greater influence in the whole set-up, since the division would be ‘concerned with evaluating, collating and distributing to user departments . . . all material obtained by British intelligence’. As has been shown above, Philby’s vaunted ‘Production’ was reduced to ‘Requirements’, and the ‘Operations’ sector became ‘Production’. Philby must have had his wings clipped during the subsequent negotiations. What is clear, however, is that – contrary to the way some accounts have represented it – the Operations Division would be organized on tight geographical (as opposed to functional) lines ‘since penetration was the cornerstone of the effort’.

An intriguing letter dated two weeks later (July 16) reflects some fascinating light on the fortunes of some of Philby’s colleagues, while enabling the KGB to prepare for the coming assaults. Major Charles de Salis ‘looks after Western Europe’, and is scheduled to be posted to Paris ‘around August 1945’ – an important date, given Philby’s itinerary. On his move to France, he will be replaced by Sir Colville Barclay. (Attentive coldspur readers may recall that Barclay once came under suspicion of being a Soviet spy himself: see https://coldspur.com/two-cambridge-spies-dutch-connections-1/ .) And ‘looking after the Middle East’ is none other than Anthony Milne, the sometime lover of Litzy Philby, who had joined Section IX in May 1944, and was forced to resign for concealing the fact – but not until twenty-five years later! The list has its comic touches: John Ivens, ‘a fruit merchant by profession’, has, as his current job, ‘dealing with the Western Hemisphere’. So comforting to know that these regions of the world were in such capable and experienced hands.

Perhaps the most extraordinary item at this time is a report on Commander Dunderdale’s SLC (Special Liaison Control), since it shows that a parallel intelligence-gathering operation was carrying on, containing an ‘Atlantic’ section, dealing with the USSR, and a ‘non-Atlantic’ one, dealing with everything else. As Philby writes:

The Atlantic section gets intelligence on the USSR from the following sources:

- Decrypting of radio telegraph traffic;

- Radio telegraph messages en clair;

- Radio-telephone intercepts; and

- Sundry overt sources such as the Soviet press.

Philby goes on to describe the hush-hush activities of the Poles in this endeavour, with interception stations in Stanmore and in Scotland, and a code-breaking bureau in Boxmoor.

While Philby expresses admiration for the energy executed in his mission by Dunderdale (another character familiar to coldspur readers: see https://coldspur.com/enigma-variations-dennistons-reward/ ), he also points out that Dunderdale ‘claims that the barriers erected around the USSR are so watertight that the old methods, i.e. agents, are virtually impossible to use. Moreover, the strict controls existing inside the country make rapid detection of agents virtually certain’. Such a judgment would obviously diminish Philby’s more expansive plans for penetration. It would be fascinating to know how this dynamic was worked through in successive months. Yet, by highlighting what the SLC did, and emphasizing that SIS would have to rely on techniques deployed by it, as described, Philby gave a clear indication to the Kremlin as to where it needed to tighten up its signals security.

No reports are available on the debates that followed the Committee’s ruminations and recommendations, and the next report is dated March 8, 1946, where Philby describes the new organization, although the final touches are awaiting budgetary approval. The report is rather a muddle: one wonders whether the NKVD officers could make any sense of it, since it displays contradictory information about the gathering of intelligence, and how the management hierarchy works. What is evident is that Philby does not exert as much influence as he imagined he would. John Sinclair has been brought in as deputy director, and reportedly has five directorates reporting to him, which Philby describes as Intelligence (including all stations engaged in counter-intelligence), Information, Finance and Administration, and Development. (He seems to have overlooked ‘Production’ in this list, which is led by Kenneth Cohen, responsible for ‘execution of intelligence operations’. Yet Philby then states that such a function lies with the Intelligence Directorate.)

Moreover, the Intelligence Directorate is headed by Easton, now third in the SIS hierarchy after Menzies and Sinclair, and Philby shares only a deputy role alongside Footman. Philby’s R5 section (‘Counter-Intelligence’) is, however, the largest, and is expected to have a staff of fifteen by the end of the year. And Philby draws attention to a vital new section, the Co-ordination section, which has ‘the very important task of comparing the value of intelligence procured with the price of procuring it, a comparison that it is required to make across very region and every issue’. This section is in the very capable hands of one Squadron Leader John Perkins. Of Dunderdale’s Special Liaison Section nothing is said. Philby’s ally Vivian has been moved out to a staff post as Advisor on Security Policy. Philby adds a short note to the effect that a small group from SOE is being merged into SIS, but it is not clear yet exactly what they are going to do.

All in all, a remarkable collection, a tale of knavery and ambition, but also including a number of pointers (dates, personnel appointments) that help shed light on the puzzling travel arrangements of Philby in 1945.

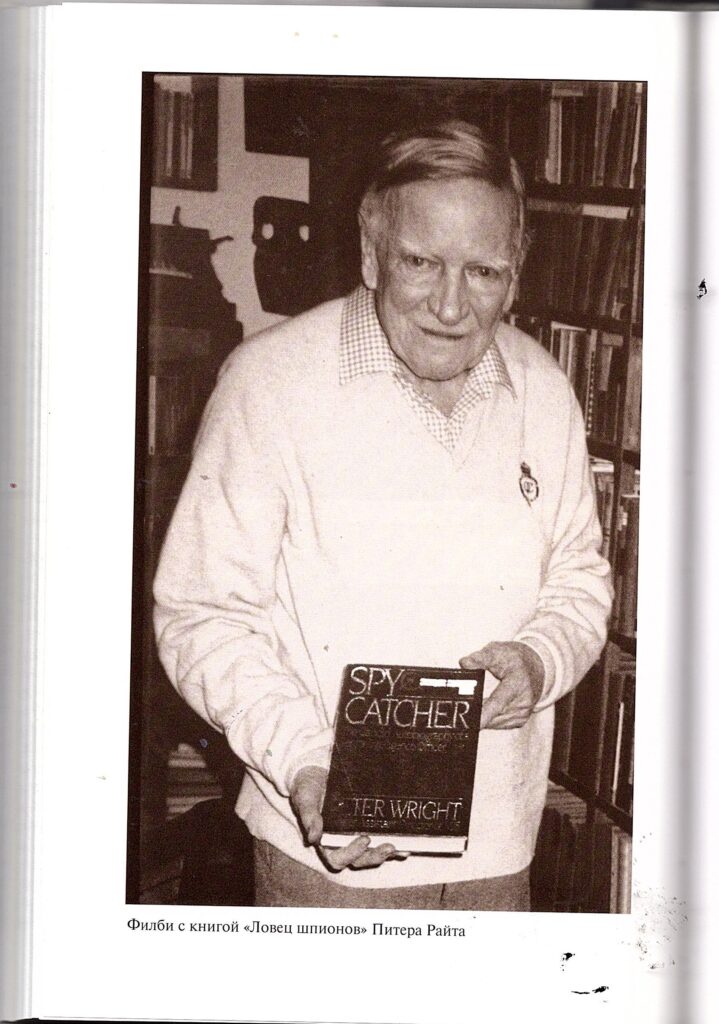

The Philby Files (Genrikh Borovik – 1994)

An important contribution is made by Borovikh, in that he quotes some of [sic] the reports that Philby wrote for his handler, Yuri Modin, on his ‘inspection tours’ of ‘the European capitals’ in 1945. Because of their immediacy, and the nature of the communication, one might expect these accounts to be of greater reliability than what Philby wrote in his memoir.

The first relevant report is dated March 1945, and describes Philby’s visits to Paris and Rome. He spoke to the MI6 head of counter-intelligence about prospects for anti-Communist work, but the unit was small, and concentrating on ‘German diversionary organisations’. In Rome, the station was more guarded. It had decided ‘to keep Section 9 from any degree of contact with local counter-intelligence service – French, Italian and so on – since they fear that those services could be infiltrated by Soviet agents’.

After reporting (in May) about an OSS project to install a microphone in the building where Togliatti works, the following month Philby recorded a visit to Athens, then Rome, before he flew to Frankfurt (on Menzies’s orders) for a conversation with General Long, chief of Allied military intelligence on the Continent. The objective was to organise ‘gathering of military and political information about the Red Army’. The narrative continues: “S [Söhnchen] reports on his conversation with Long and other members of intelligence in Frankfurt with his material”, indicating that there was further information not disclosed here.

A final relevant report (and I note that these few are probably only a selection) is dated July, and it reflects the deliberations of the committee on how MI6 should be organized best to perform espionage against the USSR. That statement would tend to confirm the suggestion I made earlier that any claims that Philby made about rallying ‘his’ people in the first half of 1945 would have been premature, and that his visits must therefore have been very exploratory. What is significant is the omission of any account of Philby’s and Milne’s expedition to Germany and Austria in July and August. One would expect that the time spent in the hotbed of Allied intelligence would have been of intense interest to Moscow. Philby may have glossed over the whole experience because of the embarrassment of the Niersteiner incident. Alternatively, the KGB might have decided not to release such a report because of its high-level strategic importance. Borovik’s evidence suggests that Philby made only two trips in the first half of 1945: one to Paris, and another to Athens, Rome and Frankfurt. As with many of these records, what is missing is sometimes as critical as what appears. But one can only guess.

* * * * * * * * * * *

In summary, the histories told a confusing story. Much guessing, some inept dating and several unlikely events, a few regular clues, a possible justification for early visits to stations in 1945, as well as some provocative links with Army Intelligence in the British Sector. Perhaps various memoirs and biographies could tell me more?

Memoirs and Biographies

Seale and McConville, Knightley & Macintyre

It is odd how this critical period in Philby’s career is overlooked by many of his biographers. Patrick Seale and Maureen McConville, in Philby: The Long Road to Moscow (1973) took a languid detour around the events of this time. They recognized Philby’s achievement in gaining the headship of Section IX, but laconically dismissed the period as follows: “ . . . from the British point of view the section was not very effective in the immediate post-war period, as its information was largely pre-war and needed extensive updating”. They moved on to the Volkov incident, and then covered the Philby divorce. While they no doubt did not have access to the records now available, they did trust to an excessive degree the surely mendacious account of the events that Vivian vouchsafed to them in letters. After some further rather desperate psychological analysis, and a brief mention of Philby’s contribution on the reorganization Committee (‘in the autumn of 1945’), they recorded Philby’s posting to Istanbul in February 1947.

Phillip Knightley, in The Master Spy (1990), having had the dubious benefit of interviewing Philby in Moscow, had a different spin on this period. He likewise attributed to Philby the achievement of making Section IX a much more aggressive operation, and explained why Cecil was so shocked at Philby’s ambitious goals in wanting to include in his charter the task of gathering intelligence in the Soviet Union. After Cecil backed down, according to Knightley, Philby ‘pushed ahead with the expansion of his section as fast as he could’, with the result that it employed ‘a staff of more than thirty’ within eighteen months – a rather more aggressive build-up than Philby acknowledged to his masters in that summer of 1945.

With no recognition of the reorganization process, or the new structures (had Knightley not even read West’s Friends at this time?), the author went on to write: “In the winter of 1945-6, Philby visited France, Germany, Sweden, Italy and Greece to brief station chiefs on what Section IX planned to do and what it would require”. He had either ignored My Silent War, or decided that he had better correct Philby’s faulty memory (without explaining why), or was simply guessing. Maybe he was using what Philby had told him more recently in Moscow, but it was a very careless treatment. He made, however, an astonishing observation that might point to a strategy that Philby had devised, but one which showed extraordinary naivety:

SIS was not surprised to discover that some of its agents, arrested by the Germans in the general round-up of 1939-40, had been recruited to work in Eastern Europe against the Soviet Union. With a typical display of pragmatism, some of the agents were now rehired by SIS, which argued that their anti-Soviet experience would be invaluable.

I am not sure what is ‘pragmatic’ about a tactic that concludes that a sweep of ‘agents’, who at that time would have had ‘anti-fascist’ and thus harboured possible communist sympathies, had been able to survive the war by working in Eastern Europe against the Soviets, and were now willing to be recruited to do it all over again, working for SIS, would turn out to be a winning gambit. This fragment, however, does perhaps provide a hint as to what Philby may have been up to in Germany in 1945.

Knightley then provides an anecdote about a Latvian, Felikss Rumniceks, who had reportedly been recruited by Philby in Stockholm in May 1945 to infiltrate Soviet Latvia, and had miraculously survived the Gulag to tell, in 1988, the tale of his betrayal. (The Soviets presented him for an interview: Philby died in May of that year.) This factoid must be highly dubious. The timing of this exploit – right at the end of the war, so early in Philby’s tenure, before the project of re-organization, at a time when SOE was still independent, in conflict with how Knightley dates Philby’s travels – would be a stunning disclosure if verifiable. It is true that the Latvian independence movement had been in touch with MI6 officer McKibbin in Stockholm, and radios had even been supplied, but for MI6 to be recruiting and infiltrating agents at this time seems to me highly unlikely. (McKibbin actually worked for Dunderdale’s SLC: he did later lead Operation JUNGLE in the Baltics. Jeffery on page 709 does record such an operation in 1949, but Philby was out of the picture by then. See also https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/1396086.pdf for more information on this fascinating issue.) In any event, Philby had earlier told Knightley that he was unrepentant over sending agents to their death in such cases, and especially in Albania.

In A Spy Among Friends (2014), Ben Macintyre is both lax and inattentive. He misattributes the setting-up of Section IX to Philby’s idea in March 1944, with Curry initially being placed in charge. While acknowledging that the section’s mission quickly evolved to running intelligence operations, not just counter-espionage, Macintyre then focuses on Philby’s close friend, Nicholas Elliott, before covering the Gouzenko and Volkov incidents, which he places in September 1945 and August 1944 [sic]respectively. He covers the sordid details of Philby’s marriage to Aileen, after ‘an uncontested and amicable divorce’ from Litzi in Paris – with no evidence offered to support his assertion – before moving smoothly on to Menzies’s directive to Philby ‘late in 1946’ that he would be sent to Istanbul as station chief. His replacement as head of Section IX (which in fact no longer existed) would be Douglas Roberts. Of the reorganization, and of Philby’s travels, Macintyre writes nothing.

I next turn to some accounts that contain a little more beef.

The Philby Conspiracy (Bruce Page, David Leitch, and Phillip Knightley, 1968)

The above-mentioned Knightley collaborated with two other journalists on the ground-breaking 1968 publication. I find it impressive in many ways, since it uncovers aspects of the case that could not have been documented at the time, and which many commentators since have ignored. Since their story is based primarily on conversations with other MI6 officers and Foreign Office personnel, it does contain errors, but overall it is insightful and accurate. The authors describe Philby’s moving from Section V in Ryder Street to his new position in Section IX, in Broadway, ‘early in 1944’. They then carry out a sharp analysis of whether the mission of Section IX was counter-espionage or more offensive activities, with one officer informing them that “It was certainly an offensive espionage operation. Philby was supposed to be setting up networks in east European countries for operating against the Russians”. This is not a convincing assertion: the timing must be premature, and Philby had no skills in that domain.

Yet they correctly judge that, because of all the information that Philby passed on, the Soviets must have retained their ‘paranoia’ about the West. They correctly assess that, while the founding of the new section took place before D-Day, its real expansion occurred afterwards. And then they make the very powerful observation about the rivalry between MI5 and MI6 over special intelligence for Eisenhower’s armies, when the responsibility was taken away from SIS, who had expected the role to fall into its lap:

But it did not. Instead, against what one participant described to us as ‘bitter’ opposition from the SIS, a special intelligence organisation was set up called the Cabinet War Room. This was an extremely successful organization, and it was controlled, de facto, by the star of MI5, Dick White. It would have been difficult to think of anything which could have outraged the SIS more. Theoretically, an SIS man was joint head of the War Room: but White was the more formidable figure, and the practical effect. The undeniable fact was that MI5, together with a gaggle of wartime ‘amateurs’, was running perhaps the most exciting foreign-intelligence operation in British history.

While the statement about White is incorrect (White was in Germany with SHAEF at the time: the MI5 officer who supervised the War Room was T. A. Robertson, of the Double-Cross Committee), the claim that the War Room, which was nominally an instrument jointly managed by OSS and MI6, was usurped by MI5, is right. It was set up in June 1944 to service Cowgill’s Special Counter-Intelligence Units (SCIUs) by providing them with the current intelligence on agents, collaborators, location of documents, enemy premises, etc. as the allied armies moved east. MI5 claimed that its greater experience in managing ‘double agents’, and the strength of its Registry, made it a more suitable body to take charge, and Tim Milne of SIS (who had replaced Philby in Section V) was not felt to be a strong enough character to manage it. (Philby famously described his friend, in a report to Moscow, as ‘a very good brain, though inclined towards inertia’.) Menzies bristled, but had to concede.

The War Room is another phenomenon that has not been adequately covered, although Chapter 15 in Hinsley’s and Simkins’s Volume 4 of British Intelligence in the Second World War gives a thorough account (while scrupulously failing to identify any names), and Edward Harrison adds some useful detail in The Secret World. Surprisingly, Andrew makes no mention of it in his history, although Guy Liddell, in his diaries, is expansive about the feuds with MI6 that surrounded it. The authors make an imaginative point that the increased aggressiveness of Section IX was developed out of pique over this slight, and thus should not have been taken seriously. “It is the very presence of Philby as director of the new section which argues that it could hardly have represented the most serious intentions of the British administration”, they wrote, and went on to marvel at SIS’s naivety. “Once again, the question arises of whether the leaders of the SIS simply knew nothing about Philby’s past or whether they knew about it and failed to investigate and take account of it”, they continued, sentiments that approach very closely my theory about the Philby ‘conversion’.

Page, Leitch and Knightley conclude their account by describing Philby’s visit to Paris to see Malcolm Muggeridge (although they do not date it). This is an important subject to which I shall return. They cite Muggeridge’s statement that Philby pointed out to him the flat where he had stayed with Litzi: Muggeridge did not mention the incident to anyone at the time. They also describe how Philby managed to survive the intense vetting process carried out by SIS in 1946. “Numerous officers were re-vetted, and some were asked to leave the Service. Philby was not one of these: he remained an important departmental executive.” Coldspur readers who have come this far will not be surprised by that assessment. Yet the authors trip over their discovery: they (erroneously) declare that Philby was moved to Turkey ‘early in the summer’ of 1946, without evidently considering that the move may have been associated with the purge of the same year.

The Climate of Treason (Andrew Boyle, 1979)

Boyle’s book was the breakthrough volume that led to the outing of Anthony Blunt. He was helped by scores of persons, many of whom he could not name for security reasons, and, of course, in this process he may well have been led astray by some who wanted to obfuscate the issue. Yet his exchanges with such as Malcolm Muggeridge and Felix Cowgill enabled him to shed some fresh light on the events of 1944 and 1945. Boyle was able to benefit from the publication of Muggeridge’s Chronicles of Wasted Time (1973) – which I inspect below – but also learned some valuable information from exclusive conversations with the ex-MI6 officer.

His treatment of J. C. Currie [sic] as the ‘makeshift’ initial head of Section IX is uncharitable and unfair, although he indicates that Cowgill denied Curry access to ‘the pre-war files’. What these files were, or what they contained, Boyle does not say, but Curry would have been intimately familiar with the files maintained in the MI5 Registry. Boyle then follows Philby’s account of his project to usurp Cowgill as the legitimate head of Section IX, with Vivian (‘a weak character who had long smarted under Cowgill’s self-righteous scorn’) easily being enrolled to the Philby cause. Boyle mistakes Robert Cecil for Patrick Reilly as Foreign Office representative, but observes that, when Philby encouraged Menzies to seek the approval of MI5 officers before he accepted the job, director-general Petrie was less than enthusiastic. Boyle writes: “Petrie, in fact, privately disapproved of the underhand scheming which eventually forced Cowgill to swallow his pride and resign from the secret service.” (That insight was provided by Cowgill himself, and Boyle offers a lengthy paragraph on Cowgill’s fruitless ongoing protests and chagrin over his treatment.)

Yet two outlying critics endured in the persons of Graham Greene and Malcolm Muggeridge. Greene rather ostentatiously resigned when Philby was appointed to head Section IX. As for Muggeridge, after his work in Mozambique, and then tours of duty in Algeria and Italy, he had been despatched to liberated Paris in mid-August 1944. He related to Boyle an incident that had occurred some weeks before the Cowgill business had come to a head, when the Personnel Chief of MI6, Kenneth Cohen, sought Muggeridge’s opinion of Philby. Cohen had ventured that ‘anyone so able and energetic as Kim would almost certainly be found a permanent post’. While this is the only indication I have found that Philby’s employment in MI6 was perhaps only temporary, Muggeridge was vehemently opposed to the idea.

“You can’t be serious, Kenneth,” Muggeridge expostulated. “I like the man as well as you do, but I wouldn’t give him house room.”

“Why not?”

“For one good reason. Kim simply can’t be trusted. He happens to be one of nature’s farouches, a wild man capable of turning the place upside down for his own ends.”

Cohen did not act upon Muggeridge’s advice, and Philby advanced. Boyle then recounts the meetings between Muggeridge and Philby ‘during the bleak winter of 1944-45’ in Paris. I shall leave the details of these encounters (when Muggeridge developed solid beliefs about Philby’s treachery) when I cover Muggeridge’s memoir (and may thus be able to date Philby’s visit more precisely). Muggeridge added other anecdotes, however, that did not make it into his memoir. The first was quite remarkable, and involved Rothschild and Philby. At a heated dinner, Rothschild had vehemently criticized the policy of withholding Bletchley Park intercepts from the Soviets, and Philby had joined him in asserting that such cooperation should override any security concerns. The second incident involved an apparent lack of interest on Philby’s part in Soviet infiltration of the French government, and a contemptuous dismissal of information volunteered by a Colonel Arnould, described as ‘the war-time head of the SIS network in France’.

The major episode that provoked Muggeridge took place after an expensive dinner that Muggeridge had reputedly shared with Philby. He tried to discern why it was that Philby had come to Paris to see him. To fire him, perhaps? No. He didn’t work for Philby then. Muggeridge knew that Philby ‘had lately fired Steptoe, a splendid character, straight out of the pages of P. G. Wodehouse, who’d worked for a while with me in Mozambique and then temporarily succeeded Currie [sic] in Section Nine before Philby’s permanent appointment was promulgated’. He fondly imagined that Philby might have wanted to recruit him (Muggeridge), ‘a well-known anti-Communist’, to his empire. For some reason, Philby funked the offer, maybe because he did not want to be rejected in the way Greene had demeaned him. In any case, Muggeridge made a major point to Boyle that he was distanced from Philby, never worked for him, and had spotted signs of his treachery early.

But why was Steptoe so cruelly let go? And what was he doing as a temporary replacement for Curry when Philby had already been anointed? And how had he managed to cause such ‘damage’ during his short tenure? Here is another testimony to Steptoe’s qualities, yet Philby was able to exert some strange power over him, without a whimper from the allies that Steptoe had in MI6. It is very odd. In The Crown Jewels, West and Tsarev write:

He [Philby] was not averse to introducing some humour: at the conclusion of this report he adds ‘Rest in Peace’ to the news that Harry Steptoe, formerly the SIS head of station in prewar Shanghai, has been posted to Algiers. Philby despised Steptoe, an old Far East hand who had been interned by the Japanese and exchanged in Mozambique together with other diplomats after long hardship. Steptoe was later to be appointed deputy head of Section IX, the anti-Communist section that was to prove such an irritant to Philby.

Section IX an ‘irritant’? That does not make sense. In any case, Muggeridge was not having anything of it, however. He told Boyle that, after the events in Paris of that winter, he couldn’t get out of SIS fast enough.

The culmination of that social evening with Philby was the incident that Muggeridge does describe in his memoirs, namely Philby’s rather absurd and flamboyant gestures outside the Soviet Embassy, where he appeared to express his frustration at the impenetrability of that institution, and the whole Soviet intelligence apparat. Muggeridge did not know what to make of it, but considered it was ‘most irregular, if not reprehensible, behaviour on the part of a senior MI6 officer’.

Treason in the Blood (Anthony Cave Brown, 1994) & The Perfect English Spy (Tom Bower, 1995)

I conjoin these two volumes because, despite the slender contribution they make, they are contemporary, and together predictably offer further confusion to the chronology. Bower’s biography of Dick White relies heavily on conversations that the chief of MI5 and MI6 had with Andrew Boyle as well as Bower, and I have shown before what a vain and deceptive raconteur White was. Yet he would not obviously have had reason to lie over some of the events in Paris.

Bower has White arriving in Paris at the end of August to join SHAEF, and sharing coarse living accommodation with ‘about ten British intelligence officers from MI5 and SIS, including Malcom Muggeridge, Desmond Bristow and later Kim Philby’. White at some stage saved Muggeridge from being deported by irate Americans over his attempts to aid the escape of P. G. Wodehouse. Bower then described ‘a contretemps over several [sic] meals with Rothschild and Philby’, also attended by Muggeridge. While Bower seems to analyze the events in some confusion, it appears that White was present at a dinner at which ‘shortly after arriving in Paris [sadly undated] Philby and Rothschild had agreed that the Russians should have been given the Ultra intercepts’. Muggeridge disagreed, but Rothschild grabbed some of those precious messages and pushed them through the letter-box of the Soviet Embassy. White was also able to witness Philby shaking his fist at the Embassy, apparently out of frustration at his inability to penetrate Soviet intelligence. What is extraordinary about this testimony is that White claimed that he was present at two of the scenes described by Muggeridge, yet Muggeridge left White out of his chronicles completely.

And then Bower writes: “As autumn approached, the deteriorating atmosphere in the small mess was aggravated by the cold.” Now this suggests to me that these bizarre goings-on occurred in late September, or possibly early October, unless White and Bower got their chronology hopelessly wrong. The ‘approach of autumn’ is far from Boyle’s ‘bleak mid-winter’, and, since Philby did not take command of Section IX until November 13 (see Triplex above), it sounds as if he was on an exploratory tour, and that Muggeridge may have conflated multiple visits into one. For example, how would Muggeridge have been able to comment, in late September 1944, on the firing of the unfortunate Steptoe?

I turned to Cave Brown. His books are always a mixed blessing. His ‘encyclopedism’ (as Trevor-Roper called it in an infamous review) can be infuriating, and he shows little discrimination in reproducing all the insights that have been entrusted to him over the years. His chronology is perpetually chaotic, and he does not have a nose for following up on ambiguous answers or statements. Yet, in between the overblown narrative, one can expect to find some useful nuggets. So it is with his Treason in the Blood, subtitled H. St. J. Philby, Kim Philby, and the Spy Case of the Century.

Typical is his coverage of Section IX. He introduces it by declaring how Churchill, in September 1944, had instructed Menzies to revive his anti-Soviet service. Yet he next asserts that Menzies responded to that command by re-establishing Section IX in March 1944, and then cites Philby’s memoir, where he explains how Philby’s Moscow bosses urged him to win the prize, and outwit Cowgill. Cave Brown then makes a meal of Graham Greene’s resignation from Section V on June 2, 1944, ostensibly because he was shocked by Philby’s intriguing and lust for power. (Other writers have questioned Philby’s role in ousting Cowgill, indicating that he was on the way out, anyway. Liddell, for example, wrote that Cowgill was fired.) Cave Brown then covers the exchanges with Robert Cecil, implicitly undertaken in March or April 1945.

Next comes a typical item of Cave Brownian flim-flam. “More or less immediately Philby began to recruit men of high quality . . .” I do not know what ‘more than immediately’ might mean, but the impression Cave Brown gives is that a stream of suitable loyal Philbyites ‘began to leave London and to situate themselves at every important outpost on foreign territory; their mission was to keep Philby informed about Soviet, American, British, and French intelligence activity in their areas of operations and to establish working relations with the local foreign counterespionage and security systems where they existed’. I am not sure what these gallant gentlemen did in their afternoons, but it strikes me as odd that such a wholesale surge of busyness could occur at exactly the time that Menzies was initiating his project to consider the new organization of MI6.

Now Cave Brown returns to Muggeridge and Paris.

As each Western European country was liberated, Philby went to its capital to restore the old prewar counterespionage alliance that had formed the basis of the cordon sanitaire against the Soviet Union. The first and the most important of the new liaisons was with General Charles de Gaulle’s Services Spéciaux in Paris. First he sent Malcolm Muggeridge to represent him and then he himself arrived soon afterwards.

Philby was reportedly installed at the Rothschild mansion on the Avenue Marigny – no chilly fleapit for him, then. And then Cave Brown, exploiting Muggeridge’s memoirs, recites the story of the drunken meal with Philby that ended up with the spy gesticulating wildly at the ‘hermetically sealed [Soviet] Embassy’. He also reproduces the spat over the Ultra disclosures carried on by Rothschild and Philby against Muggeridge, but does not source it to Boyle. Instead he refers to pages 186 and 187 of Muggeridge’s memoir, where the incident described did not take place in Paris, but in London, probably in late 1943, and Philby alone was involved, not Rothschild.

The discerning reader will by now have spotted several anomalies. Despite Muggeridge’s protestations that he would have turned down any offer by Philby to work for him, it seems that he was actually on Philby’s team when these events happened. But Cave Brown implies that they happened after the episodes with Cecil, and the roll-out of Philby’s cavalry to points around the world – thus not before April 1945. Given Muggeridge’s period of residence in Paris (see below), that would have been impossible. And Cave Brown’s own timeline is very hazy: if he really meant that Philby’s tours took place ‘as each western European country was liberated’, one might have expected that Paris (liberated August 1944) would have been graced by Philby’s visit a lot earlier. Moreover, the confusion over the place, timing and locale of the Rothschild/Philby protestations about ULTRA is utterly unforgiveable.

Maybe it was time to check what the source (Muggeridge) wrote.

Chronicles of Wasted Time: Number Two – The Infernal Grove (Malcolm Muggeridge, 1973)

Muggeridge is also characteristically vague about chronology. Some events are dated: we learn that he arrived in Paris on August 12, 1944. He soon met up with his MI6 colleague, Trevor-Wilson, and some time after that he was joined by Victor Rothschild, whose arrival enabled Muggeridge to move into the Rothschild mansion in the Avenue Marigny, where Victor Rothschild was de facto head of the family. (His sardonic description of Rothschild could not have endeared him to the ‘Socialist millionaire’.) The business with P. G. Wodehouse took place a few days after his arrival. The memoirist describes the ‘cold fuel-less winter months’ that came along, and confirms that he was representing MI6 in Paris, ‘trying to sort out the position of purported British agents who had been arrested as collaborators by the French police’.

The nearest we get to a specific date appears in the following statement: “When I had been in Paris some months, a directive came from London about a new MI6 department which had been setup specifically with Soviet intelligence activities, including sabotage and subversion. The directive had been drafted by Philby . . .” It is here that Muggeridge makes a brief reference to Steptoe, again suggesting that Philby had managed to oust him from control of Section IX rather than the maybe more deserving Cowgill. A further pointer is offered by a reference to Ambassador Duff Cooper’s anger over the Yalta Conference (which took place between February 4 and 11, 1945). Muggeridge then writes:

It was around this time I received an intimation that Kim Philby was coming over to Paris in connection with his new duties as head of the department concerned with Soviet espionage, and that he wanted to see me. He stayed in the Avenue Marigny house, and we arranged to dine together.

After Muggeridge curries favour with Philby by gratuitously insulting Vivian (whose name he mis-spells) and the unfortunate Steptoe, Philby then takes him for a stroll, and points out a block of flats where he had lived with his first wife. Muggeridge writes: