A Very Principled Boy by Mark A. Bradley (Basic Books, 2014, pp 348)

The Spy Who Changed History by Svetlana Lokhova (William Collins, 2018, pp 476)

A Spy Named Orphan by Roland Philipps (Norton & Company [in USA], 2018, pp 440)

Enemies Within by Richard Davenport-Hines (William Collins, 2018, pp 642)

A Very Principled Boy

By now, many readers may have been sated by stories of the Cambridge Spies, but may not be aware that Oxford University was determined not be outdone in infamy. Despite the observations of Professor Trevor-Roper, who, with an air almost of regret, asserted that his university had not produced any Soviet agents of its own, Oxford certainly had solid claims to a comparable Comintern-spawned ring. When MI5 and SIS in the 1960s, after the confessions of Anthony Blunt, performed their internal investigation into further penetration of the services by Soviet spies, they discovered that Arthur Wynn was probably responsible for recruiting at Oxford a number of agents in the 1930s, including Christopher Hill and Jenifer Hart (née Fischer-Williams). After Bernard Floud and Phoebe Pool (independently) committed suicide, however, the mandarins decided that they should perhaps let any other sleeping dogs lie, lest any action provoke an epidemic of self-destruction that might have challenged even the considerable skills of Chief Inspector Morse.

Yet another furtive element had existed in the nest on the Isis – Rhodes Scholars. It surprises me that so many paragons of the USA educational system, chosen for their all-round excellence, whether they brought the virus of Communist idealism with them across the Atlantic, or became infected with it by their colleagues and acquaintances at places like the Oxford Labour Club and October Club, turned out to be such bad apples. The group included Daniel Boorstin, Peter Rhodes, Donald Wheeler, and the New Zealander Ian Milner. But the most renowned individual – and the one who did the most damage – was Duncan Lee, the subject of this book. Its title derives from an assessment of Lee by a Yale professor: ‘a thorough gentleman, earnest, high-minded, tactful, clean, and honorable, and a man of unusual intellectual power and promise’. Lee also happened to attend my alma mater, the college of Christ Church, and thus I have a particular interest in him.

The author of A Very Principled Boy, Mark A. Bradley, was a Rhodes scholar himself, and his conclusion is that Lee, whose family was related to the famous Confederate general, had leftist tendencies, but was converted to a commitment to the Communist cause by his wife, Isabelle Gibb (known as Ishbel), whom he met at a dance in Oxford in May 1936. Lee had a conventional upbringing to prepare him for committing to a Great Cause: he was born in China, of earnest Episcopalian missionaries, Edmund and Lucy, and he admired his parents’ dedicated but fruitless attempts at converting the natives to Christianity. The family moved back to the United States in 1927, where, after a stellar academic career at boarding-schools, Duncan was accepted by Yale in 1931. He read widely and had deep thoughts, but remained unpoliticized, concentrating more on awards and honours, with the result that he was selected for a Rhodes scholarship in January 1935.

At Oxford, he met the already radicalized Ishbel in May 1936: they were engaged by August, and shocked his parents by their obvious cohabitation when Lucy and Edmund visited that summer. The couple visited Germany that autumn, and made the pilgrimage to the Soviet Union the following year. By then Ishbel had converted Duncan to the communist cause, and they were able to close their eyes to Stalin’s Great Terror. When they returned to Oxford, Duncan shocked his parents by telling them that he and Isabel were planning to join the Communist Party. After their marriage in May 1938, the Lees moved to the United States, where their subversive activities were reported to the FBI, who did nothing. Duncan then took up an honest communist job working as a lawyer on Wall Street. One of the partners of the firm was William Donovan, who was in April 1942 invited by Roosevelt to set up the OSS, the equivalent of Britain’s SIS. Lee moved to the OSS as Donovan’s assistant, at about the same time he was recruited, via Joseph Golos and Mary Price, to become a spy for the Soviet Union.

What distinguished Lee’s espionage was that he never handed over any physical document. Everything he gave to Mary, and her successor, Elizabeth Bentley (after Price had a health breakdown) was passed over orally. So when Bentley, in her famous 1945 confession to the FBI, identified Lee as a prime informant, he buckled down and denied everything. And even when the VENONA project, the decryptions of which revealed secret cable communications between the Washington outstation and Moscow Centre, confirmed that Lee was a prominent Soviet agent, the FBI could not afford to unveil such a sensitive source. Lee brazened it out, but it cost him his marriage (the FBI made it difficult for him to rejoin his wife and family in Bermuda), and his clean conscience. Yet he had betrayed some of the most significant secrets of World War II, those that condemned eastern Europe to Soviet domination. Lee remarried, moved to Canada, and died in 1988 after leaving a testimony for his children that portrayed himself as a victim.

Hadley tells all this in a very cool and professional way. He has delved into all the appropriate sources and archives. His judgments are sound. His conclusion on Lee’s motivations and make-up could stand as a classic assessment of many others of his tribe: “Although there is no evidence that the CIA’s psychiatrists ever studied Lee’s background, his personality reflected several of the basic traits that they have seen in others who have stolen their country’s secrets. Most spies have the ability to exhibit a sham, superficial loyalty. As narcissists who believe themselves destined to play a special role in history, they have already led lives full of mini-defections before they finally cross into full-blown betrayal. Perhaps most importantly, they are capable of ignoring the devil in themselves while condemning it in others. This permits them to deflect guilt, blame, and responsibility.” And further: “Lee’s multiple sexual affairs, or ‘mini-defections’, his compartmented personality, his violation of his government’s and mentor’s trust, his prodigious ability to lie, his belief that his hour had come when Mary Price recruited him to spy for the Soviets, his wallowing in victimhood, and his cruel attacks on Bentley underscore how accurately the CIA’s profile fits. To unleash these traits and commit espionage, Lee needed only a great cause, access to classified information, and a permissive environment.”

And what happened to the redoubtable Ishbel, who put Duncan on his perfidious track? She returned to Oxford with their four children, and then moved to Edinburgh, where she married John Petrie (who, so far as I can tell, was not closely related to David Petrie, the wartime head of MI5). To her dying day, she refused to acknowledge that Duncan had been involved in espionage. A retired CIA officer interviewed her in 1989, but drew a complete blank. In 1997, she published a brief memoir titled Not a Bowl of Cherries, emblazoned with a drawing of Christ Church’s Tom Tower on its cover, and a blurb that merely states that she was divorced from her American lawyer husband. “Duncan felt the charges made by Elizabeth Bentley very keenly, and not only because he had to answer them before a Committee of Congress and two grand juries in 1947 and 1954,’, she writes, adding: “Needless to say the charges were never substantiated.” The VENONA transcripts had been published two years before, but that did not cause the lady to even flutter. “Mainly, though, the whole crazy scene was so unlike Duncan’s style and unlike anything he had ever experienced,” was her only comment. She died in 2005. The capacity of Lenin’s and Stalin’s useful idiots for selective self-delusion and mendacity is unlimited.

The Spy Who Changed History

Let me get the ridiculous title out of the way first. This book is clearly not to be confused with Mike Rossiter’s 2014 book about Klaus Fuchs, The Spy Who Changed the World, or with Nigel West’s 1991 compendium Seven Spies Who Changed the World, a select group that excludes all of the Cambridge Spies, no doubt to their evident chagrin had they all survived long enough to learn about it. * Now, a Great Spy might make History, but he or she cannot change History, because History is integral and unvariable, and any self-respecting spy who didn’t believe that he or she was in truth having an effect on the course of history was obviously in the wrong job, and should have been working for Facebook helping to spot harmful fake news posts. The other alarming item about the choice of titles is that this book is subtitled The Untold Story of How the Soviet Union Won the Race for America’s Top Secrets, which should set off warning signals among those of us who were not aware that the project to engage in massive plundering of industrial secrets in order to be prepared to destroy the owner of such technology was actually a race to be won. What other competitors were there in this race, one wonders, and why should such sordid endeavours be sanctified with such puffery?

(* I have since discovered that Anthony Blunt is one of the featured spies in West’s book. October 1, 2018)

Next, the author. Svetlana Lokhova is described as ‘a By-Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge, and was ‘until recently a Fellow of the Cambridge Security Initiative jointly chaired by the former head of MI6, Sir Richard Dearlove, and Professor Christopher Andrew, former official historian of MI5’. So her association with those names should obviously add some gloss to that rather enigmatic introduction, right? Or was her fellowship rescinded? Her website biography claims as one of her accomplishments that she ‘identified the Sixth Man, Cedric Belfrage’, which is hardly a newsworthy achievement, and should pose questions about her credentials, and what the depth of her reading has been. Yet the unfortunate author has since had to deny suggestions that she was too closely involved with the disgraced Trump official General Michael Flynn (see https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-39863781), in a tale that is echoed somewhat by the case of another young Russian academic, this time in the USA, Sara Butina. Apparently the author had to flee, with her baby, to a retreat 600 miles from London to escape all the adverse publicity. I would not bring this up unless her work had not irritated me as a piece of inappropriate Russian propaganda: I tried to contact Ms. Lokhova via her website, but she has not granted me the favour of a reply.

So who was this epoch-making spy? His name was Stanislav Shumovsky, and Lokhova has a very innovative tale to tell. She had been given exclusive access to NKVD files (an alarming signal, in fact, which historians should be wary of) and has thus been able to disclose information unavailable to western analysts. Shumovsky was a Pole, born in 1902, whose career in flying was cut short by a crash. He then developed such depth of expertise as an aeronautical technician that he was selected to be enrolled at Harvard in 1931, with the cryptonym BLERIOT, after his hero. This was before the USA had officially recognized the Soviet Union, so trade between the two countries was impossible. The Russians, however, had their eye more on stealing industrial secrets than on paying for them. At Harvard, Shumovsky was taught by the aviation expert Jerome Hunsaker, and set about recruiting agents to the cause. He exploited mainly Jews, the offspring of parents who had escaped from pre-revolutionary Russia, but an Englishman, Norman Leslie Haight, was also in his network. In the year 1933, when the much better-known Gaik Ovakimian came to the US to be Shumovsky’s boss, Roosevelt recognized the Soviet Union, which opened up dealings quite considerably, and made institutions and corporations more positive about the country. In 1939, 18,000 pages of technical documents, 487 sets of designs, and 54 samples of new technology were shipped back to Moscow, in areas such as wind-tunnel design, high-altitude flying, and bomb-loading. Shumovsky travelled thousands of miles inspecting manufacturing plants to learn from American techniques. He arranged for Semyonov and other scientists, who would later work on the ENORMOZ atomic-bomb project, to be enrolled at MIT, which was now considered a finishing-school for ‘legal’ Soviet spies, and returned to Moscow in 1939. The capstone of his efforts was probably the unveiling of the Soviet Union’s most advanced strategic bomber in 1947.

Not only did I find all this activity distasteful, I also thought Lokhova’s treatment of it betrayed too much of a celebratory attitude towards the achievements of Comrade Stalin. There was an obtuseness about Lenin and Stalin in failing to understand that the creativity of the American free-enterprise system was what allowed so many inventions to be pursued, and yet Lokhova echoes such hypocrisy in comments such as the following: “Despite being a lifelong and dedicated Communist, he [Shumovsky] had come to respect American scientists and entrepreneurs for their extraordinary achievements in his beloved field of aviation. He had worked in the heart of capitalism and seen the rewards on offer for a successful entrepreneur like Donald Douglas, but was never tempted to defect; he was too aware of the inequalities and injustices of capitalism. All the American technological treasures he acquired were the tools needed to defend his people from a merciless invader.” She goes on to praise Shumovsky’s ‘remarkable’ skills, as he was able to exploit the disenchanted, the greedy and the idealistic – all in a cause of ugly Stalin totalitarianism that she never actually admits, as she glorifies the Soviet Union’s ability to wage war – one that Stalin thought was inevitable, even if the Americans did not.

She is also rather scathing about Western histories of intelligence, suggesting that they are ‘biased’, since they rely primarily on open western sources, or accounts from journalists and defectors. According to the author, the accounts of such as Elizabeth Bentley and Harry Gold were ‘problematic’: the results of the VENONA project have long been ‘unreliable’. You mean that they have failed to exploit those famously open archives of the Kremlin, Ms. Lokhova, and that we should be looking to the official Russian state-sponsored publications for the unvarnished truth? Given that President Putin decided to close the KGB archives after an exciting decade when western historians were allowed to gain a glimpse of what the secret police had recorded, one must view Ms. Lokhova’s access with some suspicion. I have written elsewhere (see SoniaandtheQuebecAgreement) about the highly dubious way in which Russian archives have been selectively revealed to compliant historians.

As an example, the author reveals, on page 389, that the nuclear scientist Igor Kurchatov ‘responded enthusiastically’ when Stalin made the decision on 27 September, 1942 to restart research on the atomic bomb. Kurchatov was then put in charge of the project, and became an eager consumer of all the pillaged information that Ovakimian and his agents provided for him. He provided long lists of further secrets needed, as evidenced, apparently, from Kurchatov’s letters to Molotov. Lokhova informs us that Kurchatov’s note to Stalin on accepting the challenge ‘testified not only how deep was the penetration of British laboratories in Cambridge, Birmingham and Liverpool, as well as the Chicago Metals Lab . . .’. Such a revelation should cause some flutters in English academic coops, as Kurchatov was later received and remembered with much fondness by British scientists. As Dr. Brian Austin writes, in his biography of Basil Schonland: “ . . . it was actually this giant of a man’s [Kurchatov’s] wholeheartedness and bonhomie that had endeared him to so many at Harwell . . .” (see below).The role of Fuchs and Peierls at Birmingham has been well publicised, of course, but such statements about Kurchatov’s knowledge of deeper and broader espionage merit further evidence, which Lokhova does not provide. Her source (given only as ‘USSR’s Atomic Project Documents and Materials, Moscow Naeuka, 1998’) can therefore not implicitly be relied on. She reproduces a couple of pages of VENONA transcripts identifying Shumovsky (unreliable? – see above), but offers us no NKVD documents.

Dr. Schonland, assistant director of AERE, Harwell, and Professor Igor Kurchatov, before the latter’s lecture at Harwell on April 25, 1956. The congeniality of the occasion is perhaps surprising, given that the body of the SIS diver ‘Buster’ Crabb had been found six days earlier near the S.S. Ordzhonikidze, on which vessel Kurchatov had arrived with Bulganin and Khrushchev, and that Khrushchev was at the same time threatening to drop H-Bombs on West Germany. (photograph courtesy of Dr. Brian Austin)

In a somewhat fawning review of Sir Christopher Andrew’s The Secret World: A History of Intelligence in this month’s Literary Review, Professor Michael Goodman (who is on the Advisory Board of the Cambridge Security Initiative – not a connection he declares in his piece) refers to the historian as ‘the doyen of the academic study of intelligence on the UK . . . [who] has really made the field his own’, and ‘the great Yoda [who he? Ed.] of intelligence studies in the UK’. He added that ‘there are few academics working on intelligence in the UK who cannot trace the origins of their work back to him’. Well, I am not sure that that is a healthy state of affairs, and I don’t count myself in that number, but Ms. Lokhova surely does. In her Acknowledgements, Ms. Lokhova says that she owes ‘an enormous debt to Professor Sir Christopher Andrew for introducing me to the fascinating study of intelligence history . . . Over the many years it has taken me to complete this work, Chris [sic] has been unstinting in his support and praise for my work.” Now that the text has appeared, I am not sure that the high-sounding Cambridge Security Initiative would still want its name associated with this book. Maybe that is why Ms. Lokhova is no longer a Fellow of the Initiative. ‘Former people’ – ‘byvshie lyudi’: that is what they were called in Stalin’s Russia.

Thus, for all its breakthrough revelations, it is difficult to accept Lokhova’s work completely seriously. The Spy Who Changed History fits in well with President Putin’s desire to reinvigorate Mother Russia and to bring alive again the heroic nature of the communist era. We all know that he regarded the dismantling of the Soviet Union as one of the most tragic events of the century, and Ms. Lokhova’s work falls uneasily on the wrong side of the propaganda campaign to further that goal. Maybe the most important lesson we should take from her book is that today the Chinese may have similar designs on Western technology as the Soviets did in the 1930s and 1940s.

A Spy Named Orphan

Of the Cambridge Five (or was it Thirteen? One struggles to remember . . . ), Donald Maclean was perhaps the most enigmatic. Burgess was brazen and undisciplined; Cairncross cerebral and reclusive; Blunt artificial and aloof; Philby calculating and ruthless. But none of them was tortured so severely by his traitorous activity as was Maclean, given the cryptonym ‘SIROTA’, Orphan, because of his famous father, who died in 1932. He was, in Civil Service parlance, ‘very able’ – a high-flyer expected to go far. He was also, when he was not drinking, a hard and productive worker, but the fact that he was at the same time toiling so industriously for a foreign power anguished him. At one stage, he wanted to get out, but his handlers would not let him as he was too valuable – unlike Blunt, who was able to persuade the boys from Moscow that he would be of little use to them after the war. And then, when in 1951 Maclean escaped with Burgess (to be followed later by Philby), he alone adapted successfully to life under the Communist state. He became a well-respected analyst of international affairs, whose reports were regarded seriously in the West. A famous photograph shows him at Burgess’s funeral – austere, almost pious, as if he were an acolyte at some papal ceremony, which in one sense I suppose he was.

Yet do we need another biography of him? What more is there to tell? Robert Cecil gave us his personal, sometimes fond, but not uncritical portrait of Maclean in 1988, in his A Divided Life. Michael Holzman, of a more leftist persuasion, offered a summary that exploited much new material in his 2014 work Donald and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage, including an analysis of his published work from the Soviet Union, but it was not generally available, being self-published. And there have been dozens of related works that have picked at Maclean’s boyhood, his indoctrination at Gresham’s School, Holt, and at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and traced his turbulent career in the Foreign Office, and the highly dubious circumstances of his escape with Burgess in 1951. ‘The Enigma of Donald Maclean’ is how Roland Phipps subtitles his work, incidentally reinforcing the Maclean puzzling persona. So perhaps readers should look forward to an unravelling of the riddle, and an explanation of why such an otherwise sensible boy was taken in by all the nonsense of the Communist utopia?

Roland Philipps (whose first book this is) has solid qualifications. He claims two relevant grandfathers – Roger Makins, the last Foreign Office man to see Maclean in 1951, and the unreconstructed Communist Wogan Philipps. He is a publisher with the right contacts: his ‘matchless friend and brilliant author’ Ben Macintyre encouraged him to write the book. (How come Benny Boy never urged me on? Do not write in. I think I know the answer . . .) Philipps has enjoyed access to the full Philip Toynbee and Alan Maclean papers, and help from all manner of archival resources in the UK, as well as an impressive list of experts in the field. Thus we learn details about Maclean’s life and career that have not been revealed elsewhere. I should add, however, that the author had not then had the benefit of reading Misdefending the Realm: else his Chapter 5, ‘Homer’, that covers Maclean’s relationship with Isaiah Berlin in Washington would have been a tad sharper and more insightful. (I have brought this point to Mr. Philipps’ attention, and he graciously acknowledged my message.)

I noticed a few false notes and errors. When Philipps writes on page 133: “Yet none of the Five was passing on information that would harm British interests, which therefore meant they could not be real traitors to their country . . .”, it is not clear whether he is representing Moscow’s opinion, or his own. His reference to ‘the rabid witch-hunts of the McCarthy era’, on page 284, has too much of the unthinking leftist sloganeering about it. He misrepresents some details in the Krivitsky affair. Yet it his conclusion that is the most disappointing. It runs: “Donald Maclean’s conscience was inspired by his Victorian, church-going parents, and then was forged in the godless atmosphere of the General Strike, the Depression and the rise of fascism. He was dedicated to the pursuit of peace and justice for the largest number, the humanism referred to by Izvestia. His conscience and the fulfilment of the secret life enabled him to maintain his core beliefs through the purges and the Nazi-Soviet Pact, and when many others fell away he continued to work for what he still believed in resistance to the capitalist hegemony and atomic might of his wife’s country. There is purity about this consistency that makes his collapse into alcoholism in Cairo and afterwards all the more painful.”

I don’t think this is good enough. (And it sounds rather like an obituary in Pravda.) The same could be said of Duncan Lee and his ‘Victorian, church-going parents’, but what about all those other young men growing up in the 1930s who had moralising parents or difficult fathers but who were not attracted to the plodding deceits of communism, and instead saw through Stalin and his communist edifice as a destroyer of millions rather than as a ‘pursuer of peace and justice for the largest number’? A ‘purity about his consistency’? To praise a stubborn commitment to evil in the face of overwhelming evidence that it is in fact loathsome and soul-destroying and averse to those principles one claimed to cherish is simply perverse. Moreover, Philipps quotes without comment Maclean’s best man, Mark Culme-Seymour, who had felt ‘betrayed by a man he had loved and trusted’, and had the effrontery to write to Alan Maclean, Donald’s brother, that Maclean ‘was a victim of our times and I will cling on to the idea that he was a noble victim, no matter how profoundly misguided’. Victimisation – the scourge of 21st century denial of responsibility (and remember Duncan Lee above). For Philipps to record this observation without comment shows simply bad taste. And his epitaph, on depicting Donald and his father lying side-by-side in graves in Penn, Buckinghamshire, is the equivocal and rather distressing statement: “. . . the remains of two men with the same name, both men of their times, of high ideals, optimism and strong consciences. Men with similar but differing beliefs and truths to which they remained firm, perhaps too doggedly firm.” The old thread of moral equivalence.

Thus A Spy Named Orphan is an intriguing and comprehensive – almost ‘definitive’ – account of a spy who, even he did not make Nigel West’s Top Seven, was one of the most significant betrayers of Western security. Yet we are no nearer to knowing exactly why he chose that path. Maybe it was something in the water at Gresham’s School, Holt, but more likely it was due to a mentor who encouraged what Robert Cecil called ‘Gresham’s radical heritage’ under its headmaster J. R. Eccles. Certainly that tradition allowed not only Maclean, but also such (temporary or permanent) subversives as James Klugmann, Bernard Floud, Roger and Brian Simon, Cedric Belfrage, Stephen Spender, Christopher Strachey and W. H. Auden to flourish and reinforce each other, with Tom Wintringham leading the way a decade before. One master whom the author identifies as wielding such an influence was Frank McEachran, who (as Philipps tells us) has also been claimed as a model for Hector in Alan Bennett’s History Boys. McEachran gains a short vignette in A Spy Named Orphan as ‘the Svengali-like teacher’, who, though ‘not a Marxist himself’, urged Maclean and Klugmann ‘to read Marx, and imbibe the core ideas on the state, class struggle and historical materialism’. Ah yes. I recognize those ‘academic Marxists’ (or non-Marxists), who are supposed to be quite harmless, but encourage their pupils to swallow at the pump of Marx’s banalities. That’s what the War Office and MI5 concluded about Anthony Blunt when they allowed him back into intelligence – not practical or dangerous at all. So another armchair revolutionary, McEachran, caught his ‘victims’ [!] at a most impressionable age, and they were hooked.

Enemies Within

Richard Davenport-Hines may have wondered why the Times Literary Supplement review of Enemies Within had to be shared with some upstart he had never heard of. Ben Macintyre perhaps, but Antony Percy? After all, R D-H has written one-hundred-and-sixty entries for The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, while I have written only one. And he is a Major League historian, and biographer of such subjects as W. H. Auden, Maynard Keynes and Harold MacMillan, while I am a latecomer who have never even been put on a shortlist for a possible interview by Melvyn Bragg. On the other hand, I was greatly honoured to have Misdefending the Realm appear alongside Enemies Within in Mark Seaman’s review of May 27. And I have coldspur, while Mr. Davenport-Hines does not.

So why has Mr. Davenport-Hines turned his attention to the world of espionage? As an expert analyst on social trends (look to his book on the Profumo era, for example), he brings a depth of knowledge of social climes, and a capability for narrative strength, to this intriguing topic. The flyer is promising: “With its vast scope, ambition and scholarship, Enemies Within charts how the undermining of authority, the rejection of expertise and the suspicion of educational advantages began, and how these have transformed the social and political agenda of modern Britain.” It sets out to challenge ‘entrenched assumptions about abused trust, corruption and Establishment coverups’. If indeed Davenport-Hines can explain why the Cambridge Five betrayed their country (a task that has apparently fallen beyond the capabilities of other biographers), and how it was that they managed to provoke such a passive response from the authorities, his massive work would indeed have to be compulsory reading.

But it is a heady programme. First of all, while he brings several new facts to the table, it is not clear who his audience is. While his research into some new areas (such as the Rhodes scholars) make this an indispensable book for the dedicated student of espionage history, the latter will be very familiar with most of the accounts of the nefariousness of the 1950s and 1960s. On the other hand, such masses of detail may overwhelm the more casual reader, who will no doubt be familiar with much of the story, but become confused by the mass of names and events. A long preliminary discussion over Soviet history really does not belong here, and adds little. If his case for a fresh analysis of political dynamics in Britain is to hold water, it is critical that any major new lessons that Davenport-Hines derives from his material can clearly be ascribed to a pattern of particular incidents. Yet, as he declared in his Introduction, the author does not really believe in the truth that the wills and actions of individuals can exert a powerful effect on history.

Davenport-Hines lays out some early guidelines that point to the nature of his argument: “Historians fumble their catches when they study individuals’ motives and individuals’ ideas rather than the institutions in which people work, respond, find motivation and develop their ideas.” “One aim of this book is to rebut the Titus Oates commentators who have commandeered the history of communist espionage in twentieth-century Britain.” “The key to understanding the successes of Moscow’s penetration agents in government ministries, the failures to detect them swiftly and the counter-espionage mistakes in handling them lies in sex discrimination rather than class discrimination.” Are these a priori impulses, or a posteriori conclusions? One’s immediate reaction might be to challenge all of these assertions: that individuals can exercise no individual choice but are driven by workplace factors, that a free market in espionage history has somehow been made an oligopoly (pace Sir Christopher Andrew’s dominance), and that the fashionable theme of sex discrimination has suddenly become a retrospective critical factor for assessing British political structures and why cover-ups were engaged in. So how does Davenport-Hines go about it?

The author develops his theme by covering a vast and rich array of incidents, but it is not clear which episodes support which aspect of his argument. As he tells it, overall, MI5 performed an honourable and professional job in countering the Communist subversion. The criticism that the intelligence services were guilty of aristocratic in-breeding, or homosexual camaraderie, is quite misplaced: the symptoms of failure were more male chauvinism, since female expertise was discarded or overlooked. The blame for misrepresenting what happened lies with the gutter press, with irresponsible journalist and writers, and an ill-educated Labour Party. The Cambridge spies did far more harm in eroding trust between civil servants than they did in betraying secrets. Yet even worse were the journalists. “The mole-hunters of the 1980s were foul-minded, mercenary and pernicious. Their besmirching of individuals and institutions changed the political culture and electoral moods of Britain far beyond any achievement of Moscow agents or agencies,” he writes, as if the Press had invented the whole story. The spies, he claims, could not be prosecuted because conviction would have been difficult without a confession, the evidence against them (such as in VENONA transcriptions) being too sensitive to be used in court. (But he also admits that a prosecution of Burgess would have released too many embarrassing secrets about his past career in diplomacy.) Finally, the recent loss of trust in ‘experts’ has opened the debate to untutored discussion.

This seems to me a strange line to take, and it is not helped by Davenport-Hines’s approach. The problem is that he really shows no methodology in his use of sources, making no distinction as to why some are reliable and some not, with the result that (for instance) he is taken in by a letter to one of the authorized historians of intelligence, Sir Michael Howard, who wrote an absurd letter to the Times after the Blunt fiasco claiming that inactivity was justified as Blunt had been useful as an asset in MI5’s hands. Davenport-Hines largely accepts the official histories on trust, when they need to be treated with a high degree of scepticism: he refers to Sir Christopher Andrew ‘whose painstaking research and careful conclusions belied the conspiracy theorists’. Yet, for all the diligence of the undertaking, the authorised history of MI5 is inadequate: a selective, censored and far from definitive work, and its sources cannot be verified. Davenport-Hines tends to accept unquestioningly the pronouncements of the Great and the Good (such as Gladwyn Jebb on Laurence Grand), is too quick to come to the defence of officers like the hapless Dick White against his justified critics, or the ‘luckless’ (rather than incompetent) Robert Armstrong, and is too hasty in backing the opinions of his fellow-academic Hugh Trevor-Roper. His opinion on the amount of harm perpetrated by the spies would appear to run counter to that of another well-respected ‘expert’, Nigel West, who wrote, in The Crown Jewels: “Undoubtedly, the damage inflicted by Philby, Burgess, and Blunt can only be described as colossal, and on a much greater scale than has ever been officially admitted.”

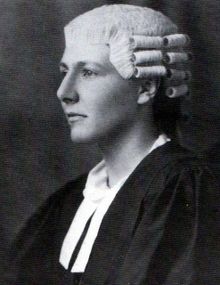

In addition, I noticed multiple minor but important errors (for example, over Fitzroy Maclean, Kitty Harris’s birthplace, the identification of ELLI, Liddell’s handling of Burgess, Petrie’s accession as head of MI5, the identities of Joe and Jane Archer, and the ‘turning’ of Wilfrid Mann). He denies the existence of an Oxford ring of spies, and judges the confessed traitor Jenifer Hart to be innocent. He is very contradictory about the role of religion in the 1930s. He makes the extraordinary claim (p 442) that the spies were relics of the 1941-45 period, when the Soviet Union was an ally, although they had been infiltrated long before. And the case for anti-feminism is weakly made, coming in almost as an afterthought. “My belief is that the dynamics of departments in government ministries and agency were gender-bound more than class-bound”, he writes, but that is rather like criticising Trollope for not writing about the ‘LBGQT community’. If there were a case to be made there, it would be over the sidelining of MI5’s sharpest counter-espionage officer, Jane Archer. Davenport-Hines picks up the fact that she was not forced to retire when she married (at the outbreak of war), but he does not develop the theme to support his argument. And how would ‘feminine’ influence have changed things? Would it have made vetting more rigorous, a pattern he would appear to disdain? Which characteristics of the ’gentler sex’ would he have preferred to have seen holding sway in the Civil Service? Those of Jenifer Hart or Ellen Wilkinson? Or those of Margaret Thatcher – or even Rosa Klebb? He does not tell us.

Yet my main cavil with the book is the fact that the author turns the undermining of civil institutions, which was undeniably effected by the actions of the Cambridge spies, into a free pass for the intelligence services and the politicians themselves, as if they were merely victims, and responded only as they could, given the constraints. On page 368, he writes that trust is one of the elements that distinguished liberal democracies from despotisms. But if a certain trust has been shown to be broken, it should be reviewed. Since the objective of the spies was to erode the whole blooming edifice of a liberal democracy, the fact that the civilities of political trust were fractured first should hardly have come as a surprise. That was why we had a Security Service in the first place. The fact was, however, that MI5 received solid leads about the deep insertion of Soviet spies from Krivitsky, but lacked the guts and insight to pursue them single-mindedly. As an institution, it never planned what it would do if it found such traitors in its midst, so it was in ‘react mode’ every time another ghastly truth came out. Davenport-Hines says that he prefers the level of trust that existed before positive vetting arrived in 1951 to ‘Gestapo methods, Stalinist purges, American loyalty tests or HUAC scapegoating’, as if there were no less draconian alternatives. But the careless way that the threat was managed could have paved the way for such totalitarian horrors.

MI5 (and SIS) should not have trusted anyone for sensitive work in intelligence simply because that person came with a good reputation. In a pluralist democracy, trust has to be earned and protected: reputation is everything. As a result, rather than facing the facts, the two intelligence services indulged in an operation of continuous cover-up, over Fuchs (when the survival of MI5 was at stake), over Burgess’s and Maclean’s career, over Blunt, over Cairncross, and even over Philby, for whom SIS had no realistic strategy. They did encourage the prosecution of outsiders (like Fuchs, and Nunn May, and Blake), but not those native Englishmen whom they had recruited themselves. Their selectivity therefore looked hypocritical. Out of this desire to protect the institution there came a great betrayal of trust to the British public, whom the authorities thought inferior and not deserving of openness. The result was that a natural void occurred for the inquiring newshounds and journalists, who smelled that the facts were not being told. The indomitable Chapman Pincher, for one, was fed both truths and lies by his informers, and it often suited the authorities to have the waters permanently muddied. The official histories came too late, and tried to finesse the problems.

I believe it is also very dangerous to draw simple sociological conclusions over such a large sweep of history. When, for my doctoral thesis, I was studying MI5 over a period of just two years (1939-41), I was exposed to multiple dynamics in organizational frameworks, managerial conflicts, personal relationships and affiliations, and individual ambitions, betrayals and mis-steps, all in an environment of rapidly shifting political fortunes and alliances. In that context I felt comfortable making judgments about the wisdom or foolishness of decisions taken or not taken. To analyse a period of sixty years, and replace one grand theme of misplaced Establishment loyalty with one that identifies failures ascribed to gender-bound, as opposed to class-bound, weaknesses, does not move the debate forward constructively. The psychology of each mole gets smothered in the sociological generalisations, and the personal contributions of different political and intelligence leaders become homogenized. “Institutional life, not parental influence, made Blunt, Burgess, Maclean and Philby what they were. They disliked the bullying, discomfort, injustice and surveillance of their schooling,” Davenport-Hines writes with apparent authority, ignoring the fact that a far greater majority of young adults were subjected to the same disciplines, but did not become traitors. Kim Philby himself warned of the danger of ‘long-range psychology’.

I suppose it all comes down to this matter of trust. Davenport-Hines wants the judgments of the experts (like him) to be trusted. He is a believer in epistocracy – government by the knowledgeable. But this is the world of espionage and intelligence. You cannot trust the memoirs of those who took part, whether spies or intelligence officers. You cannot trust the experts, especially not the authorised historians. You cannot trust the politicians. You cannot trust the scoop-seeking journalists. You cannot even trust the original documents – the archives – as they have been doctored and weeded, and maybe even deliberately planted with disinformation. Davenport-Hines does not explain why he trusts some sources, but not others, and also appears to be of the opinion that the Great British Public should not be trusted with the facts about the security services which should be accountable to it. Thus he has compiled a fascinatingly rich and enjoyable romp through a century of subversion and counter-intelligence, but, since the reader cannot rely on the sources of his judgments, he or she has to parse very carefully any claim he makes. Enemies Within is a very impressive achievement, but it is very difficult to interpret with confidence a canvas this large because of the multiple distortions of reality that are woven into the fabric in every sector. The problem is that the experts very quickly come to resemble the Establishment, and, as another famous political critic wrote of related goings-on: “ . . . already it was impossible to say which was which”.

Latest Commonplace entries can be found here.

Dear Tony Percy,

Thank you for the kind words. In case you happen to be interested, I am working on a book about the relationship of James Angleton and Kim Philby and hope someday to do some more with Melinda Maclean, who remains mysterious.

Yours,

Michael Hozlman