“These got a further boost when, just after midnight on 9 June, CATO [the German codename for GARBO] spent two full hours on the air sending a long and detailed report to his spymaster, Kühlenthal. The risk of capture was enormous when an agent transmitted that long, for it gave the direction-finding vans plenty of time to locate him. But this very fact impressed the Germans with the importance of his signal.” (Hitler’s Spies, by David Kahn, p 515)

“If the receivers of this vast screed had paused to reflect, they might have registered how unlikely it was that a wireless would have been able to operate for more than two hours without detection. But they did not.” (Double Cross, by Ben Macintyre, p 324)

“Garbo still ranked high in the esteem of his controller, but if Kühlenthal had thought coolly and carefully enough, there was one aspect of that day’s exchange of signals that might have made him suspicious. Garbo had been on the air so long that he had given the British radiogoniometrical stations ample time on three occasions to obtain a fix on his position and arrest him. Why was he able to stay on the air so long? Did he have a charmed life? Or was he being allowed to transmit by the British for the purpose of deception? These were questions that Kühlenthal might well have asked himself. But instead of being suspicious, he sent a message to Berlin. In it he recommended Garbo for the Iron Cross.” (Anthony Cave-Brown, Bodyguard of Lies, pp 676-677)

“The Abwehr remained remarkably naïve in thinking that in a densely populated and spy-conscious country like England an agent would be able to set up a transmitter and antenna without attracting attention. Moreover, it seems not to have smelled a rat from the fact that some agents, notably GARBO, were able to remain on the air for very long periods without being disturbed. It did have the good sense to furnish agents sent to Britain with only low-power sets that would cause minimal interference to neighbors’ receivers and would be more difficult for the British to monitor – though they also afforded less reliable communication. Once again, GARBO was an exception. Telling the Germans that he had recruited a radio operator with a powerful transmitter, he sent his messages at 100 watts from a high-grade set. Even this did not raise the Abwehr’s suspicions.” (Thaddeus Holt, The Deceivers, pp 142-143)

“And so, with Eisenhower’s authorization, Pujol transmitted, in the words of Harris, ‘the most important report of his career’. Beginning just after midnight, the message took two hours and two minutes to transmit. This was a dangerously long time for any agent to remain on air.” (Operation Fortitude, by Joshua Levine, p 283)

“GARBO’s second transmission lasted a record 122 minutes, and hammered home his belief that the events of the past forty-eight hours represented a diversionary feint, citing his mistress ‘Dorothy Thompson’, an unconscious source in the Cabinet Office, who had mentioned a figure of seventy-five divisions in England.” (Nigel West, Codeword OVERLORD, p 274)

“The length of this message should have aroused suspicion in itself. How on earth a real secret agent could stay on the air transmitting for so long in wartime conditions was unbelievable. British SOE agents operating in Europe were told to keep transmissions to less than five minutes in order not to be detected. However, this was not questioned.” (Terry Crowdy, Deceiving Hitler, p 270)

“We are sure that we deceived the Germans and turned their weapon against themselves; can we be quite sure that they were not equally successful in turning our weapon against is? Now our double-cross agents were the straight agents of the Germans – their whole espionage system in the U.K. What did the Germans gain from this system? The answer cannot be doubtful. They gained no good from their agents, and they did take from them a very great deal of harm. It would be agreeable to be able to accept the simple explanation, to sit back in the armchair of complacency, to say that we were very clever and the Germans very stupid, and that consequently we gained both on the swings and the roundabouts as well. But that argument just won’t hold water at all.” (The Double-Cross System, by John Masterman, p 263)

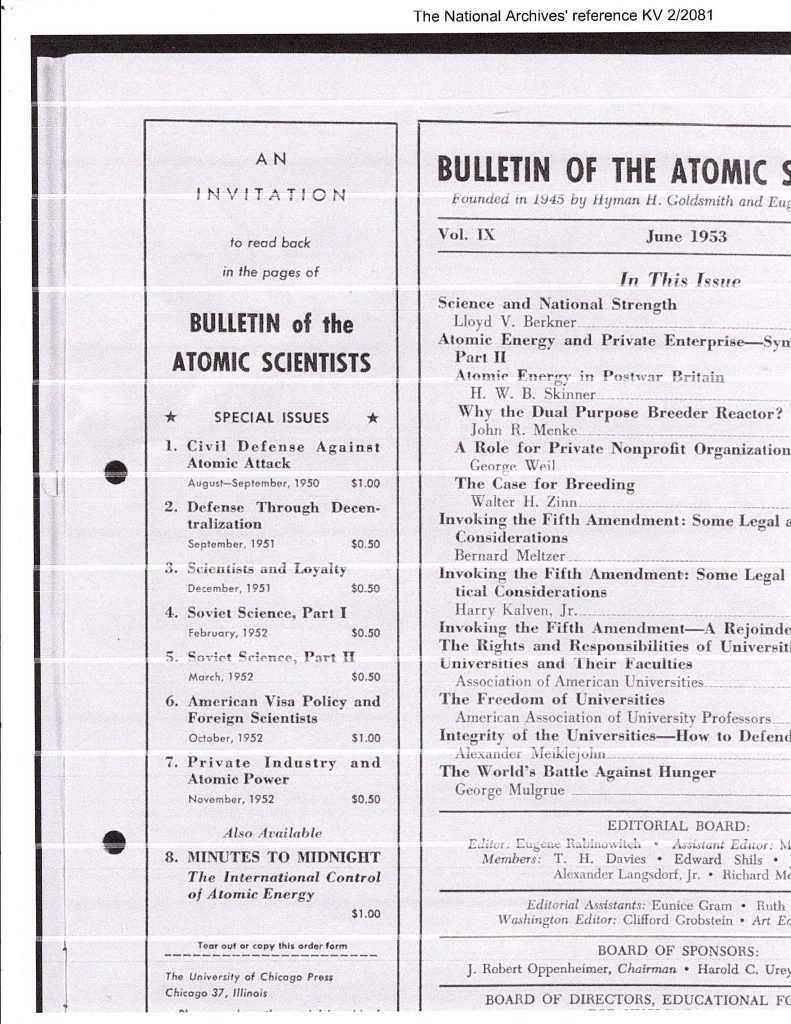

“Masterman credited only his own ideas, fresh-minted like gold sovereigns entirely from his experiences on the XX Committee. The wonder of it is, with the exception of the sporadic pooh-poohing from the likes of maverick Oxford historian A. J. P. Taylor and veteran counter-intelligence officer David Mure, The Double-Cross System came to be swallowed whole. Farago’s book was essentially forgotten; Masterman’s became celebrated.” (Fighting to Lose, by John Bryden, p 314)

“Yet, when all is said, one is left with a sense of astonishment that men in such responsible positions as were those who controlled the destinies of Germany during the late war, could have been so fatally misled on such slender evidence. One can only suppose that strategic deception derives its capacity for giving life to this fairy-tale world from the circumstance that it operates in a field into which the enemy can seldom effectively penetrate and where the opposing forces never meet in battle. Dangers which lurk in this terra incognita thus tend to be magnified, and such information as is gleaned to be accepted too readily at its face value. Fear of the unknown is at all times apt to breed strange fancies. Thus it is that strategic deception finds its opportunity of changing the fortunes of war.” (Fortitude, by Roger Hesketh, p 361)

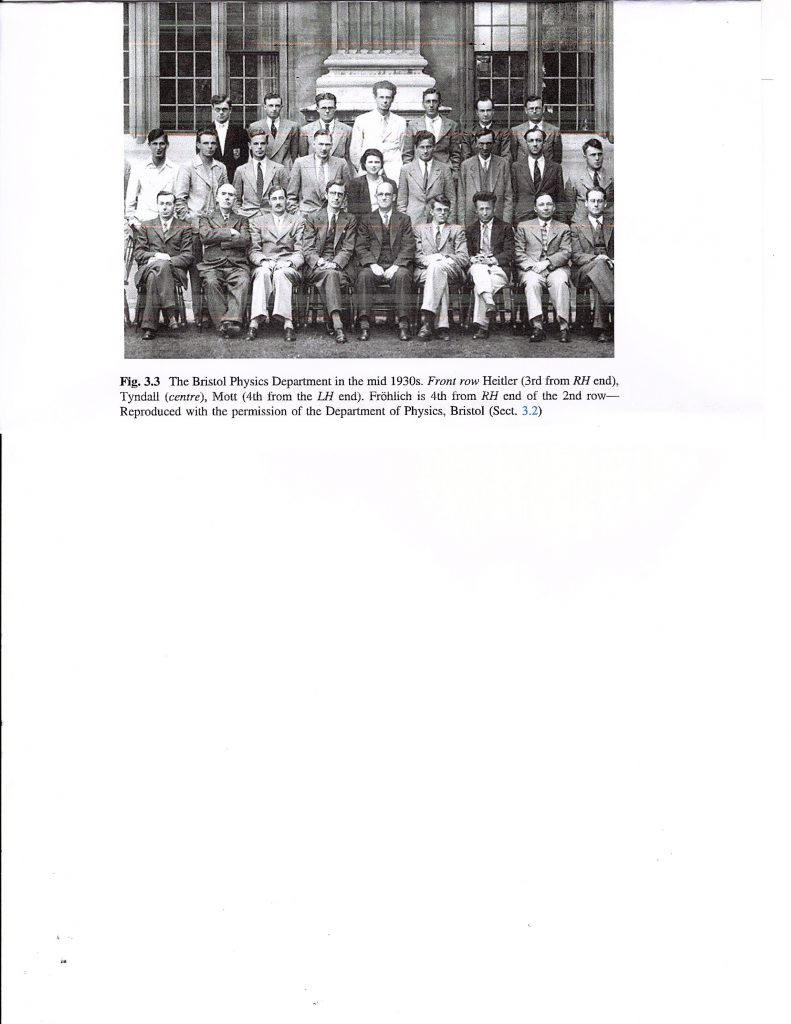

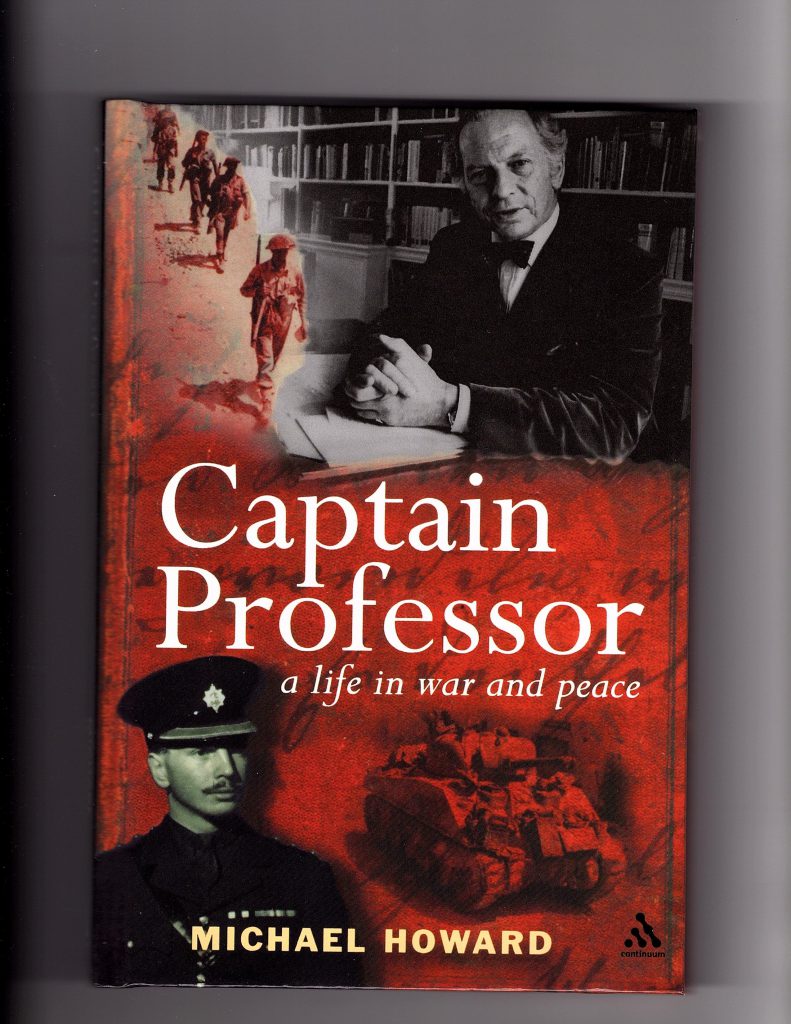

“Abwehr officials, enjoying life in the oases of Lisbon, Madrid, Stockholm or Istanbul, fiddling their expenses and running currency rackets on the side, felt that they were earning their keep so long as they provided some kind of information. This explains why for example Garbo was able to get away with his early fantasies, and Tricycle could run such outrageous risks.” (Michael Howard, British Intelligence in the Second World War, Volume 5, p 49)

“However, the claim that the Double Cross spies were ‘believed’ in ‘Berlin’ needs some amplification. Even if the information was swallowed by the Abwehr, that is not to say that it was believed at OKW or that it influenced overall German policy. Part of the problem is that the Abwehr was not a very efficient organisation. Nor was it involved in significant analysis of its intelligence product: on the contrary, the Ast and outstations tended to pounce on any snippet of potentially useful information and, rather than evaluate its intelligence value, pass it on to Berlin as evidence of their ‘busyness’ and as justification for their salaries and expense accounts.” (David Kenyon, Bletchley Park and D-Day, p 163)

“We have succeeded in sustaining them so well that we are receiving even at this stage . . . an average of thirty to forty reports each day from inside England, many of them radioed directly on the clandestine wireless sets we have operational in defiance of the most intricate and elaborate electronic countermeasures.” (Admiral Canaris, head of the Abwehr, in February 1944, from Ladislas Farago’s Game of the Foxes, p 705)

“A fundamental assumption they [the Germans] made was logically simple: if they were reading parts or all of different British codes at different times, and no mention of any signal was ever found that referred to any material transmitted by the Germans in an Enigma-encoded message, then the system had to be secure.” (Christian Jennings, The Third Reich is Listening, p 261)

The Story So Far

(Readers looking for a longer recap may want to inspect the concluding paragraphs of The Mystery of the Undetected Radios, Part VII)

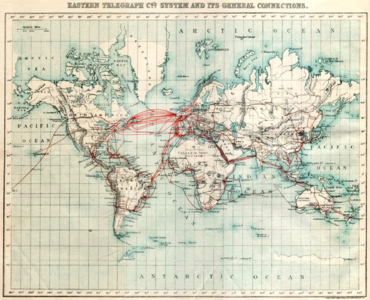

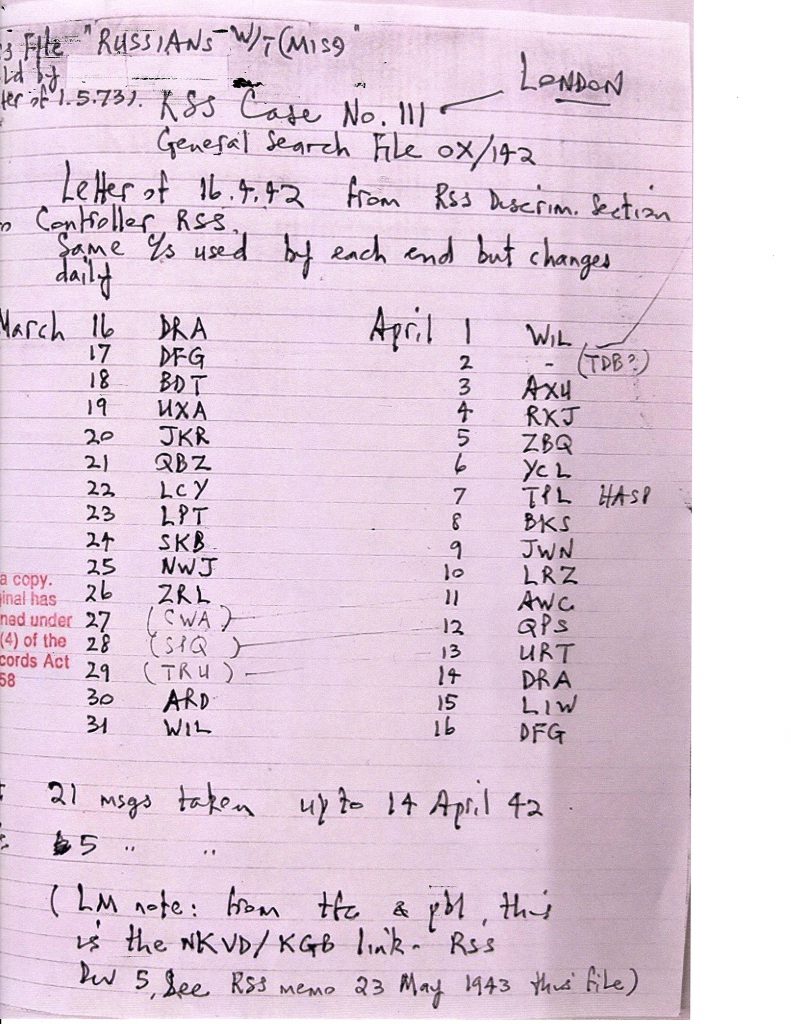

By 1943, the Radio Security Service, adopted by SIS (MI6) in the summer of 1941, has evolved into an efficient mechanism for intercepting enemy, namely German, wireless signals from continental Europe, and passing them on to Bletchley Park for cryptanalysis. Given the absence of any transmissions indicating the presence of German spies using wireless telegraphy on British soil, the Service allows its domestic detection and location-finding capabilities to be relaxed somewhat, with the result that it operates rather sluggishly in tracking down radio usage appearing to be generated from locations in the UK, whether they are truly illicit, or simply misguided. RSS would later overstate the capabilities of its mobile location-finding units, in a fashion similar to that in which the German police units exaggerated the power and automation of its own interception and detection devices and procedures. RSS also has responsibilities for providing SIS agents, as well as the sabotage department SOE (Special Operations Executive), with equipment and communications instructions, for their excursions into mainland Europe. SOE has had a very patchy record in wireless security, but RSS’s less than prompt response to its needs provokes SOE, abetted by its collaborators, members of various governments in exile, to attempt to bypass RSS’s very protocol-oriented support. RSS has also not performed a stellar job in recommending and enforcing solid Signals Security procedures in British military units. Guy Liddell, suspicious of RSS’s effectiveness, knows that he needs wireless expertise in MI5, and is eager to replace the ambitious and manipulative Malcom Frost, who is eased out at the end of 1943. It thus takes Liddell’s initiative, working closely with the maverick RSS officer, Sclater, to draw the attention of the Wireless Board to the security oversights. Towards the end of 1943, the plans for OVERLORD, the project to ‘invade’ France on the way to ensuring Germany’s defeat, start to take shape, and policies for ensuring the secrecy of the operation’s details will affect all communications leaving the United Kingdom.

Contents:

NEPTUNE, OVERLORD, BODYGUARD & FORTITUDE

Determining Censorship Policy

The Dilemma of Wireless

Findlater Stewart, the Home Defence Security Executive, and the War Cabinet

Problems with the Poles

Guy Liddell and the RSS

‘Double’ or ‘Special’ Agents?

Special Agents at Work

The Aftermath

NEPTUNE, OVERLORD, BODYGUARD & FORTITUDE

My objective in this piece is to explore and analyse policy concerning wireless transmissions emanating from the British Isles during the build-up to the Normandy landings of June 1944. This aspect of the war had two sides: the initiation of signals to aid the deception campaign, and the protection of the deception campaign itself by prohibiting possibly dangerous disclosures to the enemy that would undermine the deceits of the first. It is thus beyond my scope to re-present the strategies of the campaign, and the organisations behind them, except as a general refreshment of the reader, in order to provide a solid framework, and to highlight dimensions that have been overlooked in the histories.

OVERLORD was originally the codeword given to the assault on Normandy, but in September 1943 it was repurposed and broadened to apply to the operation of the ‘primary United States British ground and air effort against the Axis in Europe’. (Note that, on Eisenhower’s urging, it was not considered an ‘invasion’, a term which would have suggested incursions into authentic enemy territory.) NEPTUNE was the codeword used to describe the Normandy operation. BODYGUARD was the overall cover plan to deceive the enemy about the details of OVERLORD. BODYGUARD itself was broken down into FORTITUDE North and FORTITUDE South, the latter conceived as the project to suggest that the main assault would occur in the Pas de Calais as opposed to Normandy, and thus disguise NEPTUNE.

I refer the reader to six important books for greater detail on the BODYGUARD deception plan. Bodyguard of Lies, by Anthony Cave Brown (1975) is a massive, compendious volume, containing many relevant as well as irrelevant details, not all of them reliable, and the author can be annoyingly vague in his chronology. Sir Michael Howard’s British Intelligence in the Second World War, Volume 5 (1990), part of the authorized history, contains a precise and urbane account of the deception campaign, although it is rather light on technical matters. Roger Hesketh, who was the main architect of FORTITUDE, wrote his account of the project, between 1945 and 1948, but it was not published until 2000, many years after his death in 1987, as Fortitude: The D-Day Deception Campaign. (In his Preface to the text, Hesketh indicates that he was given permission to publish in 1976, but it did not happen.) Hesketh’s work must be regarded as the most authoritative of the books, and it includes a large number of invaluable, charts, documents and maps, but it reflects some of the secrecy provisions of its time. Joshua Levine’s Operation Fortitude (2001) is an excellent summary of the operation, lively and accurate, and contains a highly useful appendix on Acknowledgements and Sources. Nigel West delivered Codeword Overlord (2019), which sets out to cover the role and achievements of Axis espionage in preparing for the D-Day landings. Like many of West’s recent works, it is uneven, and embeds a large amount of source material in the text. Oddly, West, who provided an Introduction to Hesketh’s book, does not even mention it in his Bibliography. Finally, Thaddeus Holt’s Deceivers (2007) is perhaps the most comprehensive account of Allied military deception, an essential item in the library, very well written, and containing many facts and profiles not available elsewhere. It weighs in at a hefty 1000+ pages, but the details he provides, unlike Cave Brown’s, are all relevant.

Yet none of these volumes refers to the critical role of the Home Security Defence Executive (HSDE), chaired by Sir Findlater Stewart, in the security preparations. (Findlater Stewart receives one or two minor mentions in two of the Indexes, but on matters unrelated to the tasks of early 1944.) The HSDE was charged, however, with implementing a critical part of the censorship policy regarding BODYGUARD. The HSDE was just one of many intersecting and occasionally overlapping committees performing the planning. At the highest level, the Ops (B) section, concerned with deception under COSSAC (Chief of Staff to Supreme Allied Commander), was absorbed into SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) in January 1944, when General Eisenhower took over command, expanded, and split into two. Colonel Noel Wild headed Ops (B), with Jervis Read responsible for physical deception, while Roger Hesketh took on Special Means, whose role was to implement parts of the deception plan through controlled leakage.

In turn, Hesketh’s group itself was guided by the London Controlling Section (LCS), which was responsible for deciding the overall strategy of how misinformation should be conveyed to the enemy, and tracking its success. At this time LCS was led by Colonel John Bevan, who faced an extraordinary task of coordinating the activities of a large number of independent bodies, from GC&CS’s collection of ULTRA material to SOE’s sabotage of telephone networks in France, as well as the activities of the ‘double-agents’ within MI5. Thus at least three more bodies were involved: the W Board, which discussed high-level policy matters for the double-cross system under General Davidson, the Director of Military Intelligence; the XX Committee, chaired by John Masterman, which implemented the cover-stories and activities of both real and notional agents, and created the messages that were fed to the Abwehr; and MI5’s B1A under ‘Tar’ Robertson, the group that actually managed the activities and transmissions of the agents. Lastly, the War Cabinet set up a special group, the OVERLORD Security Sub-Committee, to inspect the detailed ramifications of ensuring no unauthorised information about the landings escaped the British Isles, and this military-focussed body enjoyed a somewhat tentative liaison with the civilian-oriented HDSE through the energies of Sir Findlater Stewart.

When Bevan joined the W Board on September 23, 1943, the LCS formally took over the responsibility for general control of all deception, leaving the W Board to maintain supervision of the double-agents’ work solely. Also on the W Board was Findlater Stewart, acting generally on behalf of the Ministries, who had been invited in early 1941, and who directly represented his boss, Sir John Anderson, and the Prime Minister. The Board had met regularly for almost three years, but by September 1943, highly confident that it controlled all the German agents on UK soil, and with Bevan on board, held only one more meeting before the end of the war – on January 21, 1944. It then decided, in a general stocktaking before OVERLORD, that the XX Committee could smoothly continue to run things, but that American representation on the Committee was desirable. As for Findlater Stewart, he still had a lot of work to do.

Determining Censorship Policy

The move to tighten up security in advance of NEPTUNE took longer than might have seemed appropriate. At the Quebec Conference in August 1943 Roosevelt and Churchill had agreed on the approximate timing and location of the operation, but it needed the consent of Stalin at the Teheran Conference at the end of November, and the Soviet dictator’s commitment to mount a large scale Soviet offensive in May 1944 to divert German forces, for the details to be solidified. Thus Bevan’s preliminary thoughts on the deception plan for OVERLORD, sketched out in July, had to be continually revised. A draft version, named JAEL, was circulated, and approved, on October 23, but, after Teheran, Bevan had to work feverishly to prepare the initial version of the BODYGUARD plan which replaced JAEL, completing it on December 18. This received feedback from the Chiefs of Staff, and from Eisenhower, newly appointed Commander-in-Chief, and was presented to SHAEF in early January, and approved on January 19. Yet no sooner was this important step reached than Bevan, alongside his U.S. counterpart Bauer, was ordered to leave for Moscow to explain the plan, and convince the Soviets of its merits. Such was the suspicion of Soviet military and intelligence officers, and such was their inability to make any decision unless Stalin willed it, that approval did not arrive until March 5, when the delegates returned to London.

Yet Guy Liddell’s Diaries indicate that there had already been intense discussion about OVERLORD Security, the records of which do not seem to have made it into the HDSE files. Certainly, MI5 had been debating it back in December 1943, and Liddell refers to a Security Executive meeting held on January 26. At this stage, Findlater Stewart was trying to settle what travel bans should be put in place, and as early as February 8 Liddell was discussing with his officers Grogan and (Anthony) Blunt the implications of staggering diplomatic cables before OVERLORD. The next day, he met with Maxwell at the Home Office to discuss the prevention of the return of allied nationals to the country (because of the vetting for spies that would be required).

More surprisingly, on February 11, when reporting that the Chiefs of the General Staff had become involved, and had made representations to Churchill, Liddell refers to the formation of an OVERLORD Security Committee, and comments drily: “The committee is to consist of the Minister of Production, Minister of Aircraft Production, Home Secretary and Duncan Sandys, none of whom of course know anything about security.” This committee was in fact an offshoot of the War Cabinet, which had established a Committee on OVERLORD Preparations on February 9, part of the charter of which was ‘the detection of secret enemy wireless apparatus, and increased exertions against espionage’, perhaps suggesting that not all its members were completely au fait with the historical activities of RSS and the W Board. It quickly determined that it needed a further level of granularity to address these complex security matters. Thus the Sub-committee on OVERLORD Security was established, chaired by the Minister of Production, Oliver Lyttleton, and held its first meeting on February 18, when Liddell represented MI5. Oddly, no representative from MI6 attended. Liddell continues by describing the committee’s charter as considering: 1) the possibility of withdrawing diplomatic communications privileges; 2) the prevention of export of newspapers; 3) more strengthened surveillance of ships and aircraft; 4) the detection of secret enemy wireless apparatus and increased precautions against espionage. Findlater Stewart is charged with collecting relevant material. In what seems to be an overload of committees, therefore, the HDSE and the War Cabinet carry on parallel discussions, with Findlater Stewart a key figure in both assemblies.

The primary outcome of this period is the resistance by the Foreign Office to any sort of ban, or even forced delay, in diplomatic cable traffic, which they believed would have harmful reciprocal consequences abroad, and hinder MI6’s ability to gather intelligence (especially from Sweden). This controversy rattled on for months [see below], with the Cabinet emerging as an ineffective mechanism for resolving the dilemma. Liddell believed that, if the Foreign Office and the Home Office (concerned about invasion of citizens’ rights) had not been so stubborn and prissy about the whole thing, the Security Executive could have resolved the issues quickly.

Thus the impression that Findlater Stewart had to wait for Bevan’s return for seeking guidance before chairing his committee to implement the appropriate security provisions is erroneous. Contrary to what the record indicates, the critical meeting on March 29 was not the first that the HDSE Committee held. Yet, when Bevan did return, he might have been surprised by the lack of progress. He quickly learned, on March 10, that the Cabinet had decided not to withdraw facilities for uncensored communications by diplomats, as it would set an uncomfortable precedent. That was at least a decision – but the wrong one. Bevan had a large amount of work to do shake people up: to make sure that the rules were articulated, that the Americans were in line, and that all agencies and organizations involved understood their roles. “Only under Bevan’s severe and cautious direction could they perform their parts in FORTITUDE with the necessary harmony”, wrote Cave Brown. Bevan clearly put some urgency into the proceedings: the pronouncements of LCS were passed on to Findlater Stewart shortly afterwards.

The history of LCS shows that security precautions were divided into eight categories, of which two, the censorship of civilian and service letters and telegrams, and the ban on privileged diplomatic mail and cipher telegrams, were those that concentrated on possible unauthorised disclosure of secrets by means other than direct personal travel. The historical account by LCS (at CAB 154/101, p 238) explains how the ban on cable traffic was imposed, but says nothing about wireless: “The eighth category, the ban on diplomatic mail and cipher telegrams was an unprecedented and extraordinary measure. As General EISENHOWER says, even the most friendly diplomats might unintentionally disclose vital information which would ultimately come to the ears of the enemy.”

What is significant is that there is no further mention of wireless traffic in the HDSE meetings. Whether this omission was due to sheer oversight, or was simply too awkward a topic to be described openly, or was simply passed on to the War Cabinet meetings, one can only surmise. When the next critical HDSE meeting took place on April 15, headlined as ‘Withdrawal of Diplomatic Privileges’, it echoed the LCS verbiage, but also, incidentally, highlighted the fact that Findlater Stewart saw that the main threat to security came from the embassies and legations of foreign governments, whether allies or not. Well educated by the W Board meeting, he did not envisage any exposure from unknown German agents working clandestinely from British soil.

The Dilemma of Wireless

It is worthwhile stepping back at this juncture to examine the dilemma that the British intelligence authorities faced. Since the primary security concern was that no confidential information about the details of the actual assault, or suggestions that the notional attack was based on the strength and movement of illusionary forces, should be allowed to leave the country, a very tight approach to personnel movement, such as a ban on leave, and on the holidays of foreign diplomats, was required, and easily implemented. Letters and cables had to be very closely censored. But what do to about the use of wireless? Officially, outside military and approved civil use (railway administration, police) the only licit radio transmissions were being made by Allied governments, namely the Americans and the Soviets, and by select governments-in-exile, the French, the Poles and the Czechs (with the latter two having their own sophisticated installations rather than just apparatus within an embassy). It was quite possible that other countries had introduced transmission equipment, although RSS would have denied that its use would have remained undetected.

Certainly all diplomatic transmissions would have been encyphered, but the extent to which the German interception authorities (primarily OKW Chi) would have been able to decrypt such messages was unknown. And, even if the loyalty and judgment of these missions could be relied upon, and the unbreakability of their cyphers trusted, there was no way of guaranteeing that a careless reference would not escape, and that a disloyal employee at the other end of the line might get his or her hands on an indiscreet message. (Eisenhower had to demote and send home one of his officers who spoke carelessly.) Thus total radio silence must have been given at least brief consideration. It was certainly enforced just before D-Day, but that concerned military silence, not a diplomatic shutdown.

Yet the whole FORTITUDE deception plan depended on wireless. The more ambitious aspect focused on the creation of dummy military signals to suggest a vast army (the notional FUSAG) being imported into Britain and moved steadily across the country to assemble in the eastern portion, indicating a northern assault on mainland Europe. Such wireless messages would have appeared as genuine to the Germans – if they had had the resources and skills to intercept and analyse them all. Thus the pretence had to be meticulously maintained right up until D-Day itself. In August 1943, the Inter-Services Security Board (ISSB) had recommended that United Kingdom communications with the outside world should be cut off completely, and Bevan had had to resist such pressure. As Howard points out, most involved in the discussion did not know about the Double-Cross System.

As it turned out, both German aerial reconnaissance and interception of dummy signals were so weak that the Allies relied more and more on the second leg of their wireless strategy – the transmissions of its special agents. Thus it would have been self-defeating for the War Cabinet to prohibit non-military traffic entirely, since the appearance of isolated, illicit signals in the ether, originating from British soil, and remaining undetected and unprosecuted, would have caused the Nazi receivers to smell an enormous rat. (One might add that it strains credibility in any case to think that the Abwehr never stopped to consider how ineffectual Britain’s radio interception service must be, compared with Germany’s own mechanisms, if it failed completely ever to interdict any of its own agents in such a relatively small and densely populated territory. And note Admiral Canaris’s comments above.) Of course, the RSS might have wanted to promote the notion that its interception and location-finding techniques were third-rate, just for that purpose. One might even surmise that Sonia’s transmissions were allowed to continue as a ruse to convince the Germans of the RSS’s frailties, in the belief that they might be picking up her messages as well as those of their own agents, and thus forming useful judgments about the deficiencies of British location-finding.

We should also recall that the adoption of wireless communications by the special agents was pursued much more aggressively by the XX Committee and B1A than it was by the Abwehr, who seemed quite content to have messages concealed in invisible ink on letters spirited out of England by convenient couriers, such as ‘friendly’ BOAC crewmen. Thus TREASURE, GARBO and BRUTUS all had to be found more powerful wireless apparatus, whether mysteriously acquired in London, from American sources, or whether smuggled in from Lisbon. The XX Committee must have anticipated the time when censorship rules would have tightened up on the use of the mails for personal correspondence, even to neutral countries in Europe, and thus make wireless connectivity a necessity.

In conclusion, therefore, no restrictions on diplomatic wireless communication could allow prohibition completely, as that would leave the special agents dangerously exposed. And that policy led to some messy compromises.

Findlater Stewart, the Home Defence Security Executive, and the War Cabinet

It appears that the War Cabinet fairly quickly accepted Findlater Stewart’s assurances about the efficacy of RSS. A minute from February 28 runs: “We have considered the possibility that illicit wireless stations might be worked in this country. The combined evidence of the Radio Security Service secret intelligence sources and the police leads to the firm conclusion that there is no illicit wireless station operating regularly in the British Isles at present. The danger remains that transmitting apparatus may be being held in readiness for the critical period immediately before the date of OVERLORD – or may be brought into the country by enemy agents. We cannot suggest any further measures to reduce this risk and reliance must therefore be placed on the ability of the Radio Security Service to detect the operation of illicit transmitters and of the Security Service to track down agents.” Thus the debate moved on to the control of licit wireless transmissions, where the HDSE and the War Cabinet had to overcome objections from the Foreign Office.

The critical meeting on ‘OVERLORD Security’ – ‘Withdrawal of Diplomatic Privileges’ was held on the morning of April 15, under Findlater Stewart’s chairmanship. This was in fact the continuation of a meeting held on March 29, which had left several items of business unfinished. That meeting, which was also led by Findlater Stewart, and attended by only a small and unauthoritative group (Herbert and Locke from Censorship, Crowe from the Foreign Office, and Liddell, Butler and Young from MI5) had considered diplomatic communications generally, and resolved to request delays in the transmission of diplomatic telegrams. After the Cabinet decision not to interfere with diplomatic cable traffic, Petrie of MI5 had written to Findlater Stewart to suggest that delays be built in to the process. A strangely worded minute (one can hardly call it a ‘resolution’) ran as follows: “THE MEETING . . . invited Mr. Crowe to take up the suggestion that diplomatic telegrams should be so delayed as to allow time for the Government Code and Cypher School to make arrangements with Postal and Telegraph Censorship for particularly dangerous telegrams to be delayed or lost; and to arrange for the Foreign Office, if they agreed, to instruct the School to work out the necessary scheme with Postal and Telegraph Censorship.”

It would be difficult to draft a less gutsy and urgent decision than this. ‘Invited’, ‘suggestion’, ‘to make arrangements’, ‘if they agreed’, ‘to instruct’, and finally, ‘particularly dangerous telegrams’! Would ‘moderately dangerous telegrams’ have been allowed through? And did GC&CS have command of all the cyphers used by foreign diplomacies? Evidently not, as the following discussion shows. It is quite extraordinary that such a wishy-washy decision should have been allowed in the minutes. One can only assume that this was some sort of gesture, and that Findlater Stewart was working behind the scenes. In any case, as the record from the LCS history concerning Eisenhower, which I reproduced above, shows, the cypher problem for cable traffic was resolved.

When the forum regathered on April 15, it contained a much expanded list of attendees. Apart from the familiar group of second-tier delegates from key ministries, with the War Office and the Ministry of Information now complementing Censorship, the Home Office, and the Foreign Office, Vivian represented MI6, while MI5 was honoured with the presence of no less than seven officers, namely Messrs. Butler, Robertson, Sporborg, Robb, Young, Barry – and Anthony Blunt, who no doubt made careful mental notes to pass on to his ideological masters. [According to Guy Liddell, from his ‘Diaries’, Sporborg worked for SOE, not MI5.] But no Petrie, Menzies, Liddell, White, Masterman, or Bevan. And the band of second-tier officers from MI5 sat opposite a group of men from the ministries who knew nothing of Ultra or the Double-Cross System: a very large onus lay on the shoulders of Findlater Stewart.

The meeting had first to debate the recent Cabinet decision to prohibit the receipt of uncensored communications by Diplomatic Missions, while not preventing the arrival of incoming travellers. Thus a quick motion was agreed, over the objections of the Foreign Office, that ‘the free movement of foreign diplomatic representatives to this country was inconsistent with the Cabinet decision to prohibit the receipt of uncensored communications by Foreign Missions in this country’. After a brief discussion on the movement of French and other military personnel, the Committee moved to Item IX on the agenda: ‘Use of Wireless Transmitters by Poles, Czechs and the French,’ the item that LCS had, either cannily or carelessly, omitted from its list.

Sporborg of MI5/SOE stated that, “as regards the Poles and the Czechs, it has been decided after discussion with the Foreign Office –

- that for operational reasons the transmitters operated by the Czechs and the Poles could not be closed down:

- that shortage of operators with suitable qualifications precluded the operation of those sets by us;

- that accordingly the Poles should be pressed to deposit their cyphers with us and to give us copies of plain language texts of all messages before transmission. The Czechs had already given us their cyphers, and like the Poles would be asked to provide plain language copies of their messages.”

Sporborg also noted that both forces would be asked not to use their transmitters for diplomatic business. Colonel Vivian added that “apart from the French Deuxième Bureau traffic which was sent by M.I.6, all French diplomatic and other civil communications were transmitted by cable. There were left only the French Service transmitters and in discussion it was suggested that the I.S.S.B. might be asked to investigate the question of controlling these.”

Again, it is difficult to make sense of this exchange. What ‘operational reasons’ (as opposed to political ones) could preclude the closing down of Czech and Polish circuits? It would surely just entail an announcement to targeted receivers, and then turning the apparatus off. And, since the alternative appeared to be having the transmitters operated by the British – entrusted with knowledge of cypher techniques, presumably – a distinct possibility of ‘closing down’ the sets must have been considered. As for Vivian’s opaque statement, the Deuxième Bureau was officially dissolved in 1940. (Yet it appears in many documents, such as Liddell’s Diaries, after that time.) It is not clear what he meant by ‘French Service transmitters’. If these were owned by the RF Section of SOE, there must surely have been an exposure, and another wishy-washy suggestion was allowed to supply the official record.

The historical account by LCS says nothing about wireless. And the authorized history does not perform justice to the serious implications of these meetings. All that Michael Howard writes about this event (while providing a very stirring account of the deception campaign itself) is the following: “ . . . and the following month not only was all travel to and from the United Kingdom banned, but the mail of all diplomatic missions was declared subject to censorship and the use of cyphers forbidden”, (p 124, using the CAB 154/101 source given above); and “All [the imaginary double agents] notionally conveyed their information to GARBO in invisible ink, to be transmitted direct to the Abwehr over his clandestine radio – the only channel open after security restrictions on outgoing mail had been imposed.” (p 121) The irony is that Howard draws attention to the inconvenience that the withdrawal of mail privileges caused LCS and B1A, but does not inspect the implications of trying to suppress potentially dangerous wireless traffic, and how they might have affected the deception project’s success.

Problems with the Poles

Immediately after the critical April 15 meeting, the War Office began to toughen up, as the file KV 4/74 shows. The policy matter of the curtailment of diplomatic privileges was at last resolved. Findlater Stewart gave a deadline to the Cabinet on April 16, and it resolved to stop all diplomatic cables, couriers and bags, for all foreign governments except the Americans and the Russians. The ban started almost immediately, and was extended until June 20, even though the Foreign Office continued to fight it. Yet it required some delicate explaining to the second-tier allies. Moreover, the Foreign Office continued to resist it, or at least, abbreviate it. They even wanted to restore privileges on D-Day itself: as Liddell pointed out, that would have been stupid, as it would immediately have informed the enemy that the Normandy assault was the sole one, and not a feint before a more northerly attack at the Pas de Calais.

Brigadier Allen, the Deputy Director of Military Intelligence, who had been charged with following up with the ISSB on whether the British were controlling French service traffic to North Africa, drew the attention of the ISSB’s secretary to the importance of the proposed ban. The record is sketchy, but it appears the Chiefs of Staff met on April 19, at which a realisation that control over all diplomatic and military channels needed to be intensified. The Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee was instructed to ensure that this happened, and a meeting was quickly arranged between representatives of the ISSB, MI6, SOE, the Cypher Policy Board and the Inter-Service W/T Security Committee, a much more expert and muscular group than had attended Findlater Stewart’s conference.

While the exposure by French traffic was quickly dismissed, Sir Charles Portal and Sir Andrew Cunningham, the RAF and Royal Navy chiefs, urged central control by the Service Departments rather than having it divided between SHAEF and Allied Forces Headquarters, and invited the JISC committee “to frame regulations designed to prevent Allied Governments evading the restrictions imposed by the War Cabinet on diplomatic communications, by the use of service or S.O.E. ‘underground’ W/T channels for the passage of uncensored diplomatic or service messages.” This was significant for several reasons: it recognized that foreign governments might attempt to evade the restrictions, probably by trying to use service signals for diplomatic traffic; it recommended new legislation to give the prohibitions greater force; and it brought into the picture the notion of various ‘underground’ (not perhaps the best metaphor for wireless traffic), and thus semi-clandestine communications, the essence of which was barely known. This minute appeared also to reflect the input of Sir Alan Brooke, the Army Chief, but his name does not appear on the document – probably because the record shows that he was advocating for the shared SHAEF/AFHQ responsibility, and thus disagreed with his peers.

The outcome was that a letter had to be drafted for the Czechoslovak, Norwegian and Polish Commanders-in-Chief, the Belgian and Netherlands Ministers of Defence, and General Koenig, the Commander of the French Forces in the United Kingdom, outlining the new restrictions on ‘communications by diplomatic bag and cipher telegrams’ (implicitly cable and wireless). It declared that ‘you will issue instructions that no communication by wireless is to be carried out with wireless stations overseas except under the following conditions’, going on to list that cyphers would have to be deposited with the War Office, plain language copies of all telegrams to be submitted for approval first, with the possibility that some messages would be encyphered and transmitted through British signal channels. A further amendment included a ban on incoming messages, as well.

Were these ‘regulations’, or simply earnest requests? The constitutional issue was not clear, but the fact that the restrictions would be of short duration probably pushed them into the latter category. In any case, as a memorandum of April 28 makes clear, Findlater Stewart formally handed over responsibility for the control of wireless communications to the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC), reserving for himself the handling of ‘mail and telegrams’ (he meant ‘mail and cables’, of course). By then, the letter had been distributed, on April 19, with some special annexes for the different audiences, but the main text was essentially as the draft had been originally worded.

The Poles were the quickest to grumble, and Stanisław Mikołajczyc, the Prime Minister of the Polish Government-in-Exile, wrote a long response on April 23, describing the decision as ‘a dangerous legal and political precedent’, making a special case out of Poland’s predicament, and its underground fight against the Germans. He promised to obey the rules over all, but pleaded that the Poles be allowed to maintain the secrecy of their cyphers in order to preserve the safety and security of Polish soldiers and civilians on Polish soil fighting the German. “The fact that Polish-Soviet relations remain for the time being unsatisfactory still further complicates the situation,” he added.

It is easy to have an enormous amount of sympathy for the Poles, but at the same time point out that their aspirations at this time for taking their country back were very unrealistic. After all, Great Britain had declared war on Germany because of the invasion of Poland, and the Poles had contributed significantly in the Battle of Britain and the Italian campaign, especially. The discovery by the Germans, in April 1943, of the graves of victims of the Katyn massacre had constituted a ghastly indication that the Soviets had been responsible. Yet Stalin denied responsibility, and broke off relations with the London Poles when they persisted in calling for an independent Red Cross examination. Moreover, Churchill had ignored the facts, and weaselly tried to placate both Stalin and the Poles by asking Mikołajczyc to hold his tongue. In late January, Churchill had chidden the Poles for being ‘foolish’ in magnifying the importance of the crime when the British needed Stalin’s complete cooperation to conclude the war successfully.

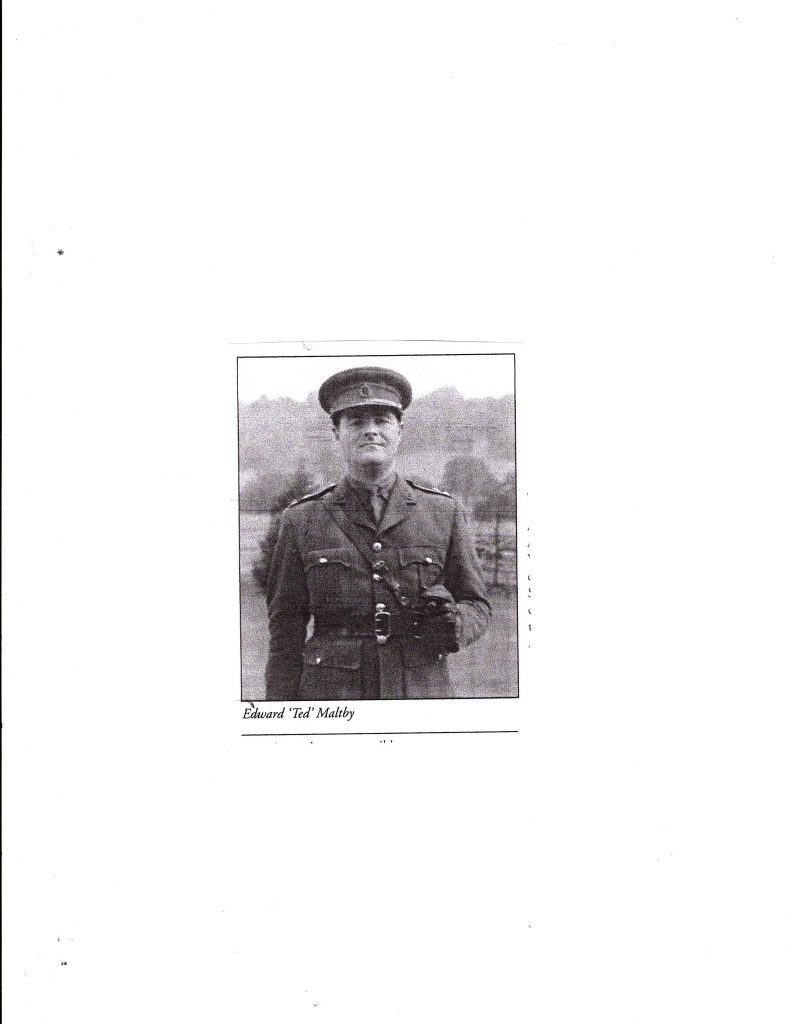

Yet the Poles still harboured dreams that they would be able to take back their country before the Russians got there – or even regain it with the support of the Russians, aspirations that were in April 1944 utterly unrealistic. The file at HW 34/8 contains a long series of 1942-1943 exchanges between Colonel Cepa, the Chief Signals Officer of the Polish General Staff, and RSS officers, such as Maltby and Till, over unrealistic and unauthorized demands for equipment and frequencies so that the Polish government might communicate with all its clandestine stations in Poland, and its multiple (and questionable) contacts around the world. Their tentacles spread widely, as if they were an established government: on December 9, 1943, Joe Robertson told Guy Liddell that ‘Polish W/T transmitters are as plentiful as tabby cats in the Middle East and are causing great anxiety’. They maintained underground forces in France, which required wireless contact: this was an item of great concern to Liddell. Thus the Poles ended up largely trying to bypass RSS and working behind the scenes with SOE to help attain their goals. The two groups clearly irritated each other severely: the Poles thinking RSS too protocol-oriented and unresponsive to their needs, RSS considering the Poles selfish and too ambitious, with no respect for the correct procedures in a time of many competing demands.

The outcome was that Churchill had a meeting with Mikołajczyc on April 23, and tried to heal some wounds. The memorandum of the meeting was initialled by Churchill himself, and the critical passage runs as follows: “Mr. Churchill told Mr. Mikołajczyc that he was ready to waive the demand that the Polish ciphers used for communication with the Underground Movement should be deposited with us on condition first, that the number of messages sent in these ciphers was kept down to an absolute minimum; secondly, that the en clair text of each message sent in these ciphers should be communicated to us; thirdly, that Mr. Mikołajczyc gave Mr. Churchill his personal word of honour that no messages were sent in the secret ciphers except those of which the actual text had been deposited with us, and fourthly, that the existence of this understanding between Mr. Mikołajczyc and Mr. Churchill should be kept absolutely confidential; otherwise H.M.G would be exposed to representations and reproaches from other foreign Governments in a less favourable position.”

Thus it would appear that the other governments acceded, that the Poles won an important concession, but that the British were able to censor the texts of all transmissions that emanated from British soil during the D-Day campaign. And Churchill was very concerned about the news of the Poles’ preferential treatment getting out. Yet the JIC (under its very astute Chairman, Victor Cavendish-Bentinck) thought otherwise – that the news was bound to leak out, and, citing the support of Liddell, Menzies, Cadogan at the Foreign Office and Newsam at the Home Office, it requested, on May 1, that the Prime Minister ‘should consider the withdrawal’ of his concession, and that, if impracticable, he should at least clarify to Mikołajczyc that it ‘related to messages sent to the underground movement in Poland and not to communications with other occupied or neutral countries’.

Moreover, problems were in fact nor restricted to the Poles. De Gaulle, quite predictably, made a fuss, and ‘threatened’ as late as May 29 not to leave Algiers to return to the UK unless he was allowed to use his own cyphers. The Chiefs of Staff were left to handle this possible non-problem. Churchill, equally predictably, interfered unnecessarily, and even promised both Roosevelt and de Gaulle (as Liddell recorded on May 24) that communications would open up immediately after D-Day. Churchill had already, very naively, agreed to Eisenhower’s desire to disclose the target and date of NEPTUNE to France’s General Koenig. The Prime Minister could be very inspiring and insightful, but also very infuriating, as people like Attlee and Brooke observed.

And there it stood. Britain controlled the process of wireless communication (apart from the Soviet and US Embassies) entirely during the course of the D-Day landings, with a minor exposure in Polish messages to its colleagues in Poland. The restrictions were lifted on June 20. And B1A’s special agents continued to chatter throughout this period.

Guy Liddell and the RSS

Guy Liddell, deputy director-general of MI5, had been energized by his relationship with Sclater of the RSS, and, with Malcolm Frost’s departure from MI5 in December 1943, he looked forward to an easier path in helping to clean up Barnet, the headquarters of the Radio Security Service. In the months before D-Day, Liddell was focused on two major issues concerning RSS: 1) The effectiveness of the unit’s support for MI5’s project to extend the Double-Cross System to include ‘stay-behind’ agents in France after the Normandy landings succeeded; and 2) his confidence in the ability of RSS to locate any German spies with transmitters who might have pervaded the systems designed to intercept them at the nation’s borders, and who would thus be working outside the XX System.

Overall, the first matter does not concern me here, although part of Liddell’s mission, working alongside ‘Tar’ Robertson, was to discover how RSS control of equipment, and its primary allegiance to MI6, might interfere with MI5’s management of the XX program overseas. Liddell had to deal with Richard Gambier-Parry’s technical ignorance and general disdain for MI5, on the one hand, and Felix Cowgill’s territoriality on the other (since a Double-Cross system on foreign soil would technically have fallen under MI6), but the challenges would have to have been faced after D-Day, and are thus beyond my scope of reference. In any case, the concern turned out to be a non-problem. The second matter, however, was very serious, and Liddell’s Diaries from early 1944 are bestrewn with alarming anecdotes about the frailties of RSS’s detection systems. The problems ranged from the ineffectiveness of Elms’s mobile units to the accuracy of RSS’s broader location-finding techniques.

I shall illustrate Liddell’s findings by a generous sample of extracts from his Diaries, as I do not believe they have appeared in print before. Thus, from January 26:

Sclater gave an account of the work by the vans on an American station which had been d.f.d by R.S.S. The station was at first thought to be a British military or Air Force one as it was apparently using their procedure. The vans went out to the Horsham area where they got a very strong signal which did not operate the needle. Another bearing caused them to put the Bristol van out, which luckily found its target pretty quickly. The point of this story is that it is almost impossible to say more than that a wireless transmitter is in the north or south of England. Unless you can get into the ground-wave your vans don’t operate. To get into the ground-wave you may need to be very close to their target. There is still no inter-com between the vans and they cannot operate for more than 8 hours without having to drive several hundred miles in order to recharge their batteries. Not a very good show. Sclater is going to find out who is responsible for American Army signal security.

While this may not have been a perennial problem for units that were repeatedly broadcasting from one place, it clearly would have posed a serious exposure with a highly mobile transmitting agent. Moreover, at a meeting on February 17, MI6/SIS (in the person of Valentine Vivian, it appears) had, according to Liddell, admitted some of its deficiencies, stating, in a response to a question as to how its General Search capability worked: “S.I.S. did not think that an illicit station was operating in this country but it was pointed out that their observation was subject to certain restrictions. They were looking for Abwehr procedure, whereas an agent might use British official procedure, which would be a matter for detection by Army Signals, who were ill-equipped to meet the task.” Did Vivian not know what he was talking about, or was this true? Could an agent using ‘British official procedure’ truly evade the RSS detectors, while the Army would not bother to investigate? I recall that Sonia herself was instructed to use such techniques, and such a disclosure has alarming implications.

The minutes of the War Cabinet Sub-committee on February 17 confirm, however, that what Vivian reported was accepted, as an accompanying report by Findlater Stewart displays how the vision for wireless interception embraced by Colonel Simpson in 1939 had been allowed to dissolve. (In fact, as Liddell’s Diaries show, a small working-party had met on the morning of the inaugural meeting to prepare for the discussion.) In a report attached to the minutes, Stewart wrote the following (which I believe is worth citing in full):

“As a result of their experience extending over some four years the Radio Security Service are of opinion there is no illicit wireless station being worked in this country at present. Nevertheless it must be borne in mind that by itself the watch kept by the Radio Security Service is subject to some limitations. For example, the general search is mainly directed to German Secret Service communications and if an agent were to use official British signal procedures (there has already been some attempt at this), it is not likely to be picked up by the Service, and no guarantee that such stations would be detected should be given unless the whole volume of British wireless traffic, including the immense amount of service signal traffic, were monitored. This ‘general search’, however, is not the only safeguard. The danger to security arises from the newly arrived German Agent (on the assumption that there are no free agents at present operating here), but the art of tracking aircraft has been brought to such a point that the Security Service feel that in conjunction with the watch kept by the Radio Security Service even a determined effort by the enemy to introduce agents could not succeed for more than a few days. Admittedly if the agent were lucky enough to be dropped in the right area and obtain his information almost at once serious leakage could occur. But there is no remedy for this.”

I find this very shocking. While the RSS was justifiably confident that no unidentified spies were operating as its interceptors were monitoring Abwehr communications closely, it had abandoned the mission of populating the homeland with enough detective personnel to cover all possible groundwaves. Apparently, the sense of helplessness expressed in Stewart’s final sentence triggered no dismay from those who read it, but I believe this negligence heralded the start of an alarming trend. And the substance of the message must have confirmed Liddell’s worst fears.

Liddell and Sclater intensified their attention to RSS’s activities. Sclater also referred, later in February, to the fact that RSS had picked up Polish military signals in Scotland, but the Poles had not been very helpful, the signals were very corrupt, as picked up, and it was not even certain ‘that the messages were being sent from Gt. Britain’. Liddell also discovered that RSS had been picking up messages relating to Soviet espionage in Sweden, and blew a fuse over the fact that the facts about the whole exercise had been withheld from MI5 and the Radio Security Intelligence Committee, which Dick White of MI5 chaired. Thus, when he returned from two weeks’ leave at the end of March, his chagrin was fortunately abated slightly, as the entry for April 16 records:

During my absence there have been various wireless tests. GARBO, on instructions from the Germans, has been communicating in British Army procedure. He was picked up after a certain time and after a hint had been given to Radio Security Service. He was, however, also picked up in Gibraltar, who notified the RSS about certain peculiarities in the signals. This is on the whole fairly satisfactory. TREASURE is going to start communicating blind and we shall see whether they are equally successful in her case. Tests have also been taking place to see whether spies can move freely within the fifteen-mile belt. One has been caught, but another, whose documents were by no means good, has succeeded in getting through seven or eight controls and has so far not been spotted.

This was not super-efficient, however: ‘hints’, and ‘after a certain time’. At least the British Army procedure was recognised by the RSS. (Herbert Hart later told Liddell that ‘notional’ spies dressed in American military uniforms were the only ones not to get caught.) But the feeling of calm did not last long. Two weeks later, on April 29, Liddell recorded:

The Radio Security Service has carried out an extensive test to discover the GARBO transmitter. The report on this exercise is very distressing. The GARBO camouflage plan commenced on 13 March but the Mobile Units were not told to commence their investigations till 14 April. From 13 March to 14 April GARBO’s transmitter was on the air (and the operator was listening) for a total of twenty-nine hours, and average of one hour a day. On 14 April the Mobile Units were brought into action and they reported that the GARBO transmitter operated for four hours between 14 and 19 April inclusive. In fact, it operated for over six and a half hours, and it would seem that the second frequency of the transmitter was not recorded at all. On 15 April, GARBO transmitted for two whole hours. This incident shakes my confidence completely in the power of RSS of detecting illicit wireless either in this country or anywhere else. It is disturbing since the impression was given to Findlater Stewart’s Committee and subsequently to the Cabinet that no illicit transmissions were likely to be undetected for long. Clearly, this is not the case.

The irony is, of course, that, if the Abwehr had learned about RSS’s woes, they might have understood how their agents were able to transmit undetected. Yet this was a problem MI5 had to fix, and the reputation of the XX System, and of the claim that MI5 had complete control of all possible German agents in the country, was at stake. Liddell followed up with another entry, on May 6:

I had a long talk with Sclater about the RSS exercise. Apparently the first report of Garbo’s transmitter came from Gib. This was subsequently integrated with a V.I. report. The R.S.S. fixed stations in N. Ireland and the north of Scotland took a bearing which was well wide of the mark, and although the original report came in on March 13th it was not until April 14th that sufficiently accurate bearings were obtained to warrant putting into action of the M.U.s. They were started off on an entirely inaccurate location of the target somewhere in the Guildford area. Other bearings led to greater confusion. Had it not been for the fact that the groundwave of the transmitter was then ranged with the Barnet station it is doubtful whether the transmitter would ever have been located. The final round-up was not done according to the book, i.e. by the 3 M.U.s taking bearings and gradually closing in. One M.U. got a particularly strong signal and followed it home.

By now, however, Liddell probably felt a little more confident that homeland security was tight enough. No problematic messages had been picked up by interception, and thus there were probably no clandestine agents at large, a conclusion that was reinforced by the fact that the ULTRA sources (i.e. picking up Abwehr communications about agents in the United Kingdom) still betrayed no unknown operators. Nevertheless, Liddell still harboured, as late as May 12, strong reservations about the efficacy of RSS’s operations overseas, which he shared with the philosopher Gilbert Ryle at his club. At this time, MI5 was concerned about a source named JOSEFINE, sending messages that reached the Abwehr via Stockholm. (JOSEFINE turned out to be the Swedish naval attaché in London, and his associates or successors.) But then, Liddell expressed further deep concerns, on May 27, i.e. a mere ten days before D-Day:

I had a long discussion with TAR and Victor [Rothschild] about RSS. It seemed to me that the position was eminently unsatisfactory. I could see that the picking up of an agent here was a difficult matter. If he were transmitting on ordinary H.F. at fairly frequent intervals to a fixed station on the continent in Abwehr procedure we should probably get his signals. If he were transmitting in our military procedure it was problematic whether we should get his signals. If he were transmitting in VHF it was almost certain that we should not get him. I entirely accept this as being the position but my complaint is that the problem of detecting illicit wireless from this country has never been submitted to a real body of experts, and that possibly had it been given careful study by such a body at least the present dangers might have been to some extent mitigated. Victor agreed that it might be possible to work on some automatic ether scanner which would increase the chances of picking up an agent. There might also be other possibilities, if the ground were thoroughly explored. So much for picking up the call. The next stage is to D.F. the position of the illicit transmitter. Recent experiments had shown both in the case of GARBO and in the case of an imaginery [sic] agent who was located at Whaddon, that the bearings from the fixed stations were 50-60 miles out. This being so, the margin for error on the continent would be considerably increased. We have always been given to understand that fixed stations could give a fairly accurate bearing. The effect is that unless your vans get into the ground-wave they stand very little chance of picking up the agent. The D.G. is rather anxious to take this matter up; both TAR and I are opposed to any such course. I pointed out to the D.G. that the Radio Security Committee consisted of a Chairman who knew nothing about wireless, and that he and I had no knowledge of the subject, and therefore we would all be at the mercy of Gambier-Parry who could cover us all with megacycles. The discussion would get us no where and only create bad blood. He seemed to think however that we ought to get some statement of the position particularly since I pointed out to him that if an agent were dropped we should probably pick him up in a reasonable time. The fact is that unless the aircraft tracks pin-pointed him and the police and the Home Guard did their job, we should be extremely unlikely to get our man. Technical means would give us little if any assistance. By the time a man had been located the harm would have been done.”

Some of this plaint was misguided (VHF would not have been an effective communication wavelength for a remote spy), but it shows that, despite all the self-satisfied histories that were written afterwards, RSS was in something of a shambles. Fortunately there were no ‘men’ to be got: the Abwehr had been incorporated into the SS in the spring of 1944. Canaris was dismissed, and no further wireless agents were infiltrated on to the British mainland. Liddell was probably confident, despite RSS’s complacent approach, that no unknown wireless agents were at large because intercepted ISOS messages gave no indication of such. He made one more relevant entry before D-Day, on June 3:

TAR tells me that since 12 May RSS have been picking up the signals of an agent communicating in Group 2 cypher. They have at last succeeded in getting a bearing which places the agents somewhere in Ayrshire. The vans are moving up to the Newcastle area. Two hours later, TAR told me that further bearing indicated that the agent was in Austria. So much for RSS’s powers of D.F.ing. My mind goes back to a meeting held 18 months ago when G.P. [Gambier-Parry] had the effrontery that he could D.F. a set in France down to an area of 5 sq. miles.

Did someone mishear a Scottish voice saying ‘Ayrshire’, interpreting it as ‘Austria’? We shall never know. In any case, if Liddell ever stopped to think “If we go to the utmost to ensure there are no clandestine agents reporting on the real state of things here, wouldn’t German Intelligence imagine we were doing just that?”, he never recorded such a gut-wrenching question in his Diaries.

‘Double’ or ‘Special’ Agents?

Before Bevan left London for Moscow, he attended – alongside Findlater Stewart – that last meeting of the W Board before D-Day. They heard a presentation by ‘Tar’ Robertson, who described the status of all the double agents, confirmed that he was confident that ‘the Germans believed in TRICYCE and GARBO, especially, and probably in the others’. Robertson added that ‘the agents were ready to take their part in OVERLORD’, and offered a confidence factor of 98% that the Germans trusted the majority of agents. The concluding minute of the meeting was a recommendation by Bevan that the term ‘double agents’ be avoided in any documentation, and that they be referred to as ‘special agents’, the term that appears in the title of the KV 4/70 file. A week later, Bevan was on his way to Moscow.

The reason that Bevan wanted them described as ‘special agents’ was presumably the fact that, if the term ‘double agent’ ever escaped, the nature of the double-cross deception would be immediately obvious. Yet ‘special agents’ was not going to become a durable term: all agents are special in some way, and the phrase did not accurately describe how they differed. Liddell continued to refer to ‘DAs’ in his Diaries, John Masterman promulgated the term ‘double agents’ in his influential Double Cross System (1972), and Michael Howard entrenched it in his authorised history of British Intelligence in the Second World War – Volume 5 (1990).

Shortly after Masterman’s book came out, Miles Copland, an ex-CIA officer, wrote The Real Spy World, a pragmatic guide to the world of espionage and counter-espionage. He debunked the notion of ‘double agents’, stating: “But even before the end of World War II the term ‘double agent’ was discontinued in favor of ‘controlled enemy agent’ in speaking of an agent who was entirely under our own control, capable of reporting to his original masters only as we allowed, so that he was entirely ‘single’ in his performance, and by no means ‘double’.” The point is a valid one: if an agent is described as a ‘double’, he or she could presumably be trying to work for both sides at once, even perhaps evolving into the status of a ‘triple agent’ (like ZIGZAG), which applies enormous psychological pressure on the subject, who will certainly lose any affiliation to either party, and end up simply trying to survive.

Yet ‘controlled enemy agent’ is, to me, also unsatisfactory. It implies that the agent’s primary allegiance is to the enemy, but that he or she has been ‘turned’ in some way. That might be descriptive of some SOE agents, who were captured, and tortured into handing over their cyphers and maybe forced to transmit under the surveillance of the Gestapo, but who never lost their commitment to the Allied cause (and may have eventually been shot, anyway). Nearly all the agents used in the Double Cross System had applied to the Abwehr under false pretences. They (e.g. BRUTUS, TREASURE, GARBO, TRICYCLE) intended to betray the Germans, and work for the Allied cause immediately they were installed. Of those who survived as recruits of B1A, only TATE had arrived as a dedicated Nazi. He was threatened (but not tortured) into coming to the conclusion that his survival relied on his operating under British control, and he soon, after living in the UK for a while, understood that the democratic cause was superior to the Nazi creed. SUMMER, on the other hand, to whom the same techniques were applied, refused to co-operate, and had to be incarcerated for the duration of the war.

Thus the closest analogy to the strategy of the special agents is what Kim Philby set out to do: infiltrate an ideological foe under subterfuge. But the analogy must not be pushed too far. Philby volunteered to work for an intelligence service of his democratic native country, with the goal of facilitating the attempts of a hostile, totalitarian system to overthrow the whole structure. The special agents were trying to subvert a different totalitarian organisation that had invaded their country (or constituted a threat, in the case of GARBO) in order that liberal democracy should prevail. There is a functional equivalence, but not a moral one, between the two examples. Philby was a spy and a traitor: he was definitely not a ‘double agent’, even though he has frequently been called that.

I leave the definitional matter unresolved for now. It will take a more authoritative writer to tidy up the debate. I note that the highly regarded Thaddeus Holt considers the debate ‘pedantic’, and he decided to fall back upon ‘double agent’ in his book, despite its misleading connotations.

Special Agents at Work

The events that led up to the controversial two-hour message transmitted by GARBO on June 9, highlighted in the several quotations that I presented at the beginning of this script, have been well described in several books, so I simply summarise here the aspects concerning wireless usage. For those readers who want to learn the details, Appendix XIII of Roger Hesketh’s Fortitude lists most of the contributions of British ‘controlled agents’ on the Fortitude South Order of Battle, and how they were reflected in German Intelligence Reports. Ben Macintyre’s Double Cross gives a lively account of the activities of the agents who communicated via wireless – via their B1A operators, in the main.

TATE (Wulf Schmidt) was the longest-serving of the special agents, but the requirement to develop a convincing ‘legend’ about him, in order to explain to the Abwehr how he had managed to survive for so long on alien territory, took him out of the mainstream. In October 1943, Robertson had expressed doubts as to how seriously the Germans were taking TATE, as they had sent him only fourteen messages over the past six months, and in December, the XX Committee even considered the possibility that he had been blown. Their ability to verify how TATE’s reports were being handled arose mainly because communications were passed to Berlin from Hamburg by a secure land-line, not by wireless (and thus not subject to RSS/GC&CS interception.) Indeed, Berlin believed that the whole ‘Lena Six’ (from the 1940-41 parachutist project, and whose activity as spies was planned to last only a few weeks before the impending German invasion!) were under control of the British, but the Abwehr, in a continuing pattern, were reluctant to give up on one of their own. The post-war interrogation of Major Boeckel, who trained the LENA agents in Hamburg, available at KV 2/1333, indicates that Berlin had doubts about TATE’s reliability, but that Boeckel ‘maintained contact despite warnings’. TATE provided one or two vital tidbits (such as Eisenhower’s arrival in January 1944), and by April, the XX Committee judged him safe again. In May, he was nominally ‘moved’ to Kent, ostensibly to help his employer’s farming friend, and messages were directed there from London, in case of precise location-finding. But TATE’s information about FUSAG ‘operations’ did not appear to have received much attention: TATE’s contribution would pick up again after D-Day.

The career of TREASURE (Lily Sergeyev, or Sergueiev) was more problematical. In September 1943 she had had to remind her handler, Kliemann, that she was trained in radio operation, and that she needed to advance from writing letters in secret ink. Kliemann then improbably ordered her to acquire an American-made Halicrafter apparatus in London, and then promised to supply her one passed to her. He let her down when she visited Madrid in November, so the XX Committee had to start applying pressure. They engineered a March 1944 visit by TREASURE to Lisbon, where she was provided with a wireless apparatus, and instructed on when and how to transmit, with an emphasis that the messages should be as short as possible. She returned to the UK; her transmitter was set up in Hampstead, and her first message sent on April 13. There was a burst of useful, activity for about a month or so, but, by May 17, a decision was made that TREASURE had to be dropped. She confessed to concealing from her B1A controllers the security check in her transmissions that she could have used to alert the Germans to the fact that she was operating under control: she was in a fit of pique over the death of her dog. Robertson fired her just after D-Day.

TRICYCLE (Dusko Popov) had formulated a role that allowed him to travel easily to Lisbon, but the Committee concluded that he need to communicate by wireless as well. Popov had engineered the escape to London of a fellow Yugoslav, the Marquis de Bona, in December 1943, who would become his authorized wireless operator, and Popov himself brought back to the UK the apparatus that de Bona (given the cryptonym FREAK) started using successfully in February. Useful information on dummy FUSAG movements was passed on for a while, but a cloud hung over the whole operation, as the XX Committee feared, quite justifiably, that TRICYCLE might have been blown because Popov’s contact within the Abwehr, Johnny Jebsen (ARTIST) knew enough about the project to betray the whole deception game. When Jebsen was arrested at the end of April, TRICYCLE and his network were closed down, with FREAK’s last transmission going out on May 16. TRICYCLE explained the termination in a letter written in secret ink on May 20, ascribing it to suspicions that had arisen over FREAK’s loyalties. Astonishingly, FREAK sent a final message by wireless on June 30, and the Germans’ petulant response indicated that they still trusted TRICYCLE. After the war, MI5 learned that Jebsen had been drugged and transported to Berlin, tortured and then killed, but said nothing.

The career of BRUTUS (Roman Czerniawski) was also dogged by controversy, as he had brought trouble on himself with the Polish government-in-exile, and the Poles had access to his cyphers. Again, fevered debate over his trustworthiness, and deliberation over what the Germans (and Russians) knew about him continued throughout 1943. His wireless traffic (which had been interrupted) restarted on August 25, but his handler in Paris, Colonel Reile, suspected that he might have been ‘turned’. Indeed, his transmitter was operated by a notional friend called CHOPIN, working from Richmond. By December 1943, confidence in the security of BRUTUS, and his acceptance by the Abwehr, had been restored: the Germans even succeeded in delivering him a new wireless set. Thereafter, BRUTUS grew to become the second most valuable member of the team of special agents. A regular stream of messages was sent, beginning in from February 1, culminating in an intense flow between June 5 and June 7, providing (primarily) important disinformation about troop movements in East Anglia.

Lastly, the performance of GARBO was the most significant – and the most controversial. According to Guy Liddell, GARBO had made his first contact with the Abwehr in Madrid in March 1943. GARBO had also claimed to have found a ‘friend’ who would operate the wireless for him. The Abwehr was so pleased that it immediately sent him new cyphers (invaluable to GC&CS), and, a month later, advised him how to simulate British Army callsigns, so as to avoid detection. A domestic crisis then occurred, which caused Harmer in MI5 to recommend BRUTUS as a more reliable vehicle than GARBO, but it passed, and, by the beginning of 1944 GARBO was using his transmitter to send more urgent – as well as more copious – messages. GARBO benefitted from a large network of fictional agents who supplied him with news from around the country, and his role in FORTITUDE culminated in the epic message of June 9 with which I introduced this piece.

The Aftermath

BODYGUARD was successful. The German High Command viewed the Normandy landings as a feint to distract attention from the major assault they saw coming in the Pas de Calais. They relied almost exclusively on the reports coming in from the special agents. They did not have the infrastructure, the attention span, or the expertise to interpret the deluge of phony signals that were generated as part of FORTITUDE NORTH, and they could not undertake proper reconnaissance flights across the English Channel to inspect any preparations for the assault that they knew was coming. Interrogations of German officers after the war confirmed that the ‘intelligence’ transmitted by the five agents listed above was passed on and accepted at the very highest levels. This phenomenon has to be analysed in two dimensions: the political and the technical.

The fact that the Abwehr (and its successor, the SS) were hoodwinked so easily by the substance of the messages was not perhaps surprising. To begin with, the Abwehr was a notoriously anti-Nazi organisation, and the role of its leader, Admiral Canaris, was highly ambiguous in his encouraging doubts about the loyalty of his agents to be squashed. He told his officer Jebsen (ARTIST) that ‘he didn’t care if every German agent in Britain was under control, so long as he could tell German High Command that he had agents in Britain reporting regularly.’ Every intelligence officer has an inclination to trust his recruits: if he tells his superiors that they are unreliable, he is effectively casting maledictions on his own abilities. Those who spoke up about their doubts, and pursued them, were moved out to the Russian front. The Double Cross System was addressing a serious need.

When the ineffectiveness and unreliability of the Abwehr itself was called into question, and the organisation was subsumed into the SS, the special agents came under the control of disciplinarians and military officers who did not really understand intelligence, were under enormous pressures, and thus had neither the time nor the expertise to attempt to assess properly the information that was being passed to them. They had experienced no personal involvement with the agents supposedly infiltrated into Britain. What intelligence they received sounded plausible, and appeared to form a pattern, so it was accepted and passed on.