(Since I shall be on holiday/vacation in California and Maui for the remainder of December, I am posting this month’s blog early, as a special gift to all my readers – and especially to the members of the Murmansk Chapter of the Coldspur Appreciation Society – and presenting a piece that I wrote five years ago. When I started my research for what was then going to be a master’s degree, the focus was very much on Isaiah Berlin, and I decided then to write up some initial findings on various episodes in his life that Michael Ignatieff’s biography bypassed. I have used parts of this essay in a previous post (‘Some Diplomatic Incidents‘), and have explored in depth some aspects concerning Berlin’s role in intelligence in my book Misdefending the Realm. I have also described the strange coincidence that found Berlin in Estoril at exactly the time (early January 1941) when Soviet agent Sonia received her permission to travel to the UK (see ‘Sonia’s Radio: Part VIII)’. The essay could also be updated in the light of more recent findings. For instance, I have now discovered that Berlin’s claims to have stayed at the Palacio Hotel in Estoril, Portugal, in that January, appear to have been completely fabricated, which must cast some doubt on the accuracy of other details he provided on his journey from the UK to the USA. Exploring those murky events warrants a dedicated blog later in 2018. I thus present ‘Isaiah in Love’ unchanged. I shall update the Commonplace files on my return. A happy seasonal festival to all my readers! December 12, 2017. P.S. Please note that I now list, for ease of access, all previous monthly blog entries on the ‘About’ page.)

December Commonplace entries duly posted here. (December 31)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

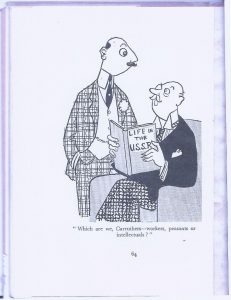

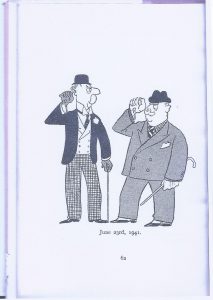

One of the more bizarre episodes in the life of the great intellectual historian Sir Isaiah Berlin occurred when Guy Burgess invited him to join him on a trip to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1940. Burgess, probably anxious to make contact with his spymasters after the purging of the London station, had persuaded his mentor Harold Nicolson that Berlin, a native Russian speaker, should be appointed as press officer at the embassy in Moscow. Was Berlin merely a cover? Did Burgess have other motives for enticing Berlin to Russia? Maybe – but Berlin was in any case eager to fulfill a long-time desire to visit the Soviet Union. The necessary paperwork was arranged, and Berlin and Burgess left Liverpool for Moscow, via Montreal, the US, and Vladivostock. They never completed the journey. In New York, Burgess received the news that he was to be recalled to London. Unlike ‘recalls’ to Moscow, where agents would probably be sent to the Lubianka, for no other reason than that they had been exposed to Western influences, Burgess was simply fired by MI6 on his return. There, in the treatment of agents under a cloud, lay a key difference between the West and Soviet Russia: in Moscow, a bullet in the back of the head; in London, a transfer to the BBC. Yet, despite Berlin’s ease in gaining a visa from the Soviet Embassy in Washington, the Foreign Office quickly scotched his hopes of taking up his post in Moscow, and he was left twiddling his thumbs. Adapting to circumstances, he quickly earned a reputation for his deft analysis of the American scene, and through the British Embassy was offered a semi-permanent job with the British Press Service. While successful in this role, Berlin wanted to return to the United Kingdom first, one strong reason he gave his biographer being that he was did not want to be thought cowardly in avoiding the Blitz back in England. Was this desire not to end up as a character in an Evelyn Waugh novel, like the elopers Auden and Isherwood, whom Waugh so sharply lampooned as Parsnip and Pimpernel, some neat retrospective insight? Put Out More Flags did not appear until 1942. The timing is unclear: Michael Ignatieff’s biography of Berlin states that Burgess came to Berlin’s rooms with his plan ‘in mid-June’, while Henry Hardy notes in Volume 1 of Berlin’s Letters that it was ‘in late June’. On June 23, Berlin wrote to Marion Frankfurter, wife of Felix, the associate justice on the Supreme Court, joining in the condemnation of Auden, Isherwood and Macneice, and added: ‘ – if I could induce some institution in the U.S.A. to invite me, I would. But cold-blooded flight is monstrous.’.

Ignatieff’s biography covers this period, but depicts the philosopher’s return to the United Kingdom, in the winter of 1940-41, as an insignificant interlude. In doing so, Ignatieff was largely reliant on Berlin’s account of that journey. After describing how Berlin returned on a sea-plane with Lord Lothian, the British Ambassador, as far as Lisbon (whence Lothian moved on alone, leaving Berlin to await a regular flight), he devotes a paragraph to Berlin’s time in Oxford and London, mentioning along the way a lunch with Guy Burgess and Harold Nicolson at the Ministry of Information. He then writes: ‘A month into term, a letter arrived from the Ministry of Information ordering Berlin to return immediately to New York. Having reassured his parents, arranged his leave from New College, and having proved that he wasn’t running away from the Blitz, Isaiah now returned to New York with a clear conscience.’

But did Berlin really have a clear conscience? While he evidently did not want to be seen as an escapist, it is unlikely that anyone would have thought that of him, since his journey to Washington had been on government business. Nevertheless, all the evidence suggests he had a hidden agenda that he was never comfortable making public, and points towards his motivation for returning to Europe being a desire to meet with his current hero, Chaim Weizmann, at an important rendezvous in Lisbon to discuss Zionist matters. Why, as his life was fading to a close, would he wish to conceal such activities from his biographer? Both his Zionist enthusiasm and scepticism were well-known; after the creation of the Israeli state, he had had misgivings over the way it had developed, as well as over the pusillanimity of the British government towards it. He had had to be careful about promoting ideas too energetically while being employed by that same government. So why would he try to prevent his attendance at a meeting in Lisbon becoming part of the record?

That he intended to meet Weizmann in Lisbon seems clear from a reading of the biography and his Letters 1928-1946. The following conclusions are derivable:

1) Berlin contrived a convoluted story about the renewal of his post in Washington. The first impression he leaves is that he was offered a permanent job with the British Press Service there in 1940, but negotiated that he had to return to the UK first. A letter to his parents, dated October 5, from New York, states that his job is ‘practically fixed’. But in his Introduction to Washington Dispatches (1980), he muddies the waters by indicating that he returned home without an understanding that he had an offer to continue the job in Washington. When in the UK, he reports that he received a sharp letter from the Ministry of Information asking him to explain why he hadn’t reported for duty, at which he claims that he had never been told about the appointment, an observation which the Ministry admitted was true. (Henry Hardy, the editor of the Letters, points out this contradiction in a note.) On the other hand, he writes to a friend, Marie Gaster (January 3, 1941) and gives a very different account, claiming he was not offered anything attractive in Washington, and wanted to return to the UK to look for something more appropriate. He further suggests that, much against his will, he was then encouraged to take up the job with the British Press Service, and ‘return to America at once’. (Hardy suggests that this account ‘offers a possible explanation of what really happened’, but it gives the appearance of yet another smokescreen.)

2) Berlin indicates that his return to the UK should have been considered as a personal trip, because he takes pains, in a letter to his parents (October 5, 1940), to make arrangements for the cost of the four links in the journey (New York-Lisbon-UK-Lisbon-New York) to be paid partly by them. If he was in any way on government business, because an appointment had come to a close, or he needed to be interviewed for another position, he would surely have had his expenses paid for him by the UK Government. In fact, in another letter to his parents (January 10, 1941), when stuck in Estoril, he writes that, ‘unlike the private passengers, I can claim a Govt. priority from the Air Attaché.’ And, indeed, the manifest for his voyage from Lisbon to New York, on the SS Excambion, does indicate that his fare was paid for by the British Government.

3) Berlin always intended to see Chaim Weizmann during his visit, probably to explore a position with the Jewish Agency. Ignatieff reports on that preference in the biography. In another letter to his parents (September 3, 1940), he writes: ‘I should like to hop back [sic] to England, see some people, Lord Lloyd [Secretary of State for the Colonies], Weizmann, etc., arrange with Oxford, & skip back [sic] again, preferably by Clipper.’ ‘Hopping and skipping’ was not the normal mode of travel across the Atlantic during the early years of WWII, but it helps suggest to posterity that Berlin was in a hurry to get back, implying again that he had a permanent position waiting for him in the USA that he was eager to assume. He also made a reference to possible ‘ice on the Clipper’s wings’ in January, which might necessitate a slower return by boat. The Weizmann papers in fact show that Weizmann did enjoy a thorough de-briefing from Berlin soon after his arrival in the UK. Berlin was asked to describe the disruptive effect a visit from a Foreign Office functionary, a Mr Voss, had had on Jews in the US. Weizmann expressed his desire that Berlin could delay his trip back to the States so that they could journey together. Communications must have broken down, because, shortly before his departure, writing from Oxford, Berlin tries to contact Weizmann, after abortive phone-calls, with a note of urgency detectable in the message, at the Dorchester Hotel in London in December 1940, saying that he would ‘make a gigantic effort to see you before I go’, and asking Weizmann to ‘write or wire me in Oxford where & when you are to be expected in Lisbon and whom I could ask, while there, about your probable whereabouts?’ Berlin was due to leave on January 3, from Bournemouth airport. Lastly, he writes to his old friend Maire Gaster (wife of the Communist activist, Jack Gaster) again, just before his flight to Lisbon, informing her that he is very miserable at the prospect of leaving the UK for New York, but that ‘there is no doubt that there is a job to perform & my new God Dr Weizmann is wooing me ardently into doing it.’ For some reason, communications broke down, or Weizmann lost his enthusiasm for having Berlin work for the Jewish Agency. Berlin was deceptive when explaining this offer to his biographer: he told Ignatieff that Weizmann had urgently pressed him to accept a position with the organization when in New York, but that he had ‘diplomatically declined the Chief’s embrace’. On the other hand, he was perhaps playing for time.

4) Berlin had been impressed with Weizmann when he met him early in 1939. At the time, Weizmann was heavily involved, as head of the Jewish Agency and the World Zionist Organization, in negotiating with the British Government the form of the Jewish homeland in Palestine, as well as the shape of a Jewish Fighting Force to be established in Palestine as part of the British Army. But talks had stalled. Lord Lloyd, the Colonial Secretary, was fatally ill, and would die on February 2, 1941. Anthony Eden, representing the Arabist Foreign office, was executing delaying tactics; Weizmann decided to extend his stay in London until he could witness the proclamation of the communiqué announcing the Jewish Unit. Of all this, Berlin seemed to be unaware. He wrote to his parents (January 10, 1941), in the Excambion, on Hotel Estoril Palacio notepaper – about to leave, but still moored – that he intended to buy dried fruit for the journey later in the day. The timing means, that, despite his – and his employers’ – desire for him to report quickly to the States, he would have been able to have a few days with Weizmann, and almost a week in Lisbon for any meetings before embarking on his voyage. Mysteriously he told his parents that ‘Chaim said he was going – the 15th’, which suggests that he was very much out of date. Weizmann did not leave England for the United States until March 10. Finally, Berlin bizarrely informs his parents, in a letter from New York (January 28, 1941), that he spent ‘two agreeable days in Portugal about which I wrote to you from Lisbon’ – a gross understatement of the time he spent there. As for Weizmann, he completely ignores this interval, his autobiography Trial and Error skipping directly from meetings with Churchill in September 1940 to the bland statement: ‘In the spring of 1941 I broke off my work in London for a three month trip to America.’

Was there a secret Zionist meeting in Lisbon, at which Berlin and Weizmann had hoped to meet? As the Nazi net closed around the capitals of Europe, the Portuguese capital had become a popular city for assignations of every kind. For example, an important Jewish charitable organization, the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, was compelled to close its offices in Paris as the Germans approached in 1940, and relocate to Lisbon. With official German authorization, Dr. Josef Löwenherz, described as ‘the leader of Jews in Vienna’ visited Lisbon in neutral Portugal (apparently in 1940 or 1941) to meet with representatives of the World Jewish Congress, including Dr. Parlas, described as ‘secretary to Chaim Weizmann’ (but who does not appear in the Index to Weizmann’s memoirs), and with WJC financial affairs director Tropper. Löwenherz wanted to negotiate an agreement for the mass emigration of Jews from German-controlled Europe. But if Berlin attended such meetings, he says nothing about them. And, as a government employee, he had to be very careful about adopting Zionist causes too vigorously.

Berlin’s enthusiasm for Zionism was typical of the contradictions that appeared to grip him at times, and cause perennial self-doubt. While he believed fervently that a home in Palestine was essential to protect the beleaguered and oppressed Jews of Eastern Europe, in the United Kingdom (as well as the United States) Berlin would often encounter Jews who had gradually been assimilated and who were taken aback by the whole idea of Zionism. Some found the notion that the world could be divided into Jews and Gentiles to be as bizarre – and even as offensive – as the notion that it could be divided into Aryans and non-Aryans. And Berlin was not consistent himself. In his government role, he was often asked to calm the more urgent Zionists, and he often called upon the secular Jew Victor Rothschild to help him in his mission. Such gestures, of embracing a vague ‘Jewish’ but unreligious culture but resisting the more extreme aspects of Zionism, sometimes got him into trouble. Ignatieff represents Berlin’s views on cultural identity in the following way: ‘individuals must have secure cultural belonging if they are to be free’. While that sounds more like T. S. Eliot than Isaiah Berlin, Berlin appeared never to come to terms with the paradox that assimilated Jews whom he encountered could be happy with their situation, having cast off so many cultural remnants, whereas he always had feelings of being an outsider. Right up to the time of his death he expressed feelings of alienation, of not being accepted in English society, unaware, perhaps, that an insistence on tribal separateness constituted the real irritant to a pluralist culture. But many Jews established in Britain were not interested in aspirations for a homeland for Jews. As Kenneth Rose writes of (some of) the Rothschilds: ‘By a century and a half of assiduous assimilation they had emerged from the ghetto of Frankfurt to the broad, sunlit uplands of Buckinghamshire; they were not prepared to see their security eroded by a sentimental attachment to Zionism.’ Later on in life, Berlin saw Zionism in action – the terrorism, the jingoism – and began to realize that it was becoming just another of those Grand Solutions of which he was instinctively suspicious. His enthusiasm for it nevertheless sometimes blinded his judgment, and caused him some missteps. Ignatieff recounts the way that Berlin, stung by a critical review by the Trotskyist * Isaac Deutscher, was antagonized by ‘Deutscher’s political dogmatism and his hostility to Zionism’, and decided to destroy the historian’s chances for being appointed to a professorship at Sussex University, saying that Deutscher was ‘the only man whose presence in the same academic community as myself I should find morally intolerable.’ But anti-Zionism is not the same thing as anti-Semitism: in an exchange with the critic Christopher Hitchens, Berlin tried to wriggle out of the charge of trying to scotch Deutscher’s ambitions, and thus suppressing free speech.

[* Nuno Miranda pointed out to me on June 2, 2021 that Deutscher was a Trotskyist, not a Stalinist, as the original text claimed.]

In any case, a momentous encounter causes the plot to take a sudden switch, as in a Hitchcock film. In his letter to his parents dated January 28, 1941, after he arrived in New York, Berlin gave a thumb-nail sketch of the voyage across the Atlantic. ‘A mixed, very mixed company, a Duchess, a lot of rich expatriated Americans, the Times correspondent from Lisbon, a plump Jewess from Geneva called Frieda Vogel who insisted, to the general amusement that she was a Turk, a member of an old Turkish family, etc.’ Indeed, some breathtakingly clear camera footage of the arrival in New York of the Excambion appears to confirm some of this picture. These are not images of starving refugees delirious at their first sight of the Manhattan skyline, but of comfortable-looking citizens in furs and plush coats, chewing gum and smoking cigars, looking happily at familiar landmarks. They receive perfunctory inspections of their landing passes, and make landfall without stress. On the other hand, it must have been a much more arduous inspection for escapees from Nazi Europe; US immigration officials were urged to be very careful in discriminating between US citizens and aliens. And from a study of the ship’s manifest, one can fill in a few details in Berlin’s account. The Times journalist was Walter Edward Lucas, returning with his American wife, Lenore (née Sandberg). The duchess was 27-year-old Solange de Vivonne, described as widowed; Frieda Vogel, single, aged 39, and travelling with her mother, had indeed been born in Istanbul. Yet Berlin fails to identify someone who must have been the most famous passenger on board at that time, someone very close to the Roosevelts in the White House – Eve Curie, who had in 1937 published an extremely successful biography of her mother, Marie Curie, the Nobelist scientist, and was travelling from the UK on a lecture tour. When interviewed in one of the lounges on the Excambion, as it moved from Quarantine to Pier F, in Jersey City, Madame Curie gave a promotional speech for Great Britain, and pleaded for more tangible aid to the war effort there. Berlin, himself a government propagandist, surprisingly makes no mention of her or her role. Maybe his attentions were drawn elsewhere during the ten-day voyage. For, as he decades later told his biographer, it was on that ship that he first saw a striking lady. ‘He had noticed the tall, elegant, shy woman, and wondered who she was.’

The woman was named Aline Strauss, and would fifteen years later become his wife. Aline was travelling with her son, Michel, aged four. She was a widow, and had fled south from Paris as the Germans approached, staying in Biarritz, then Nice, and running to Portugal after the Vichy regime published its anti-Jewish edicts. (Ignatieff reports all this.) But it could have not been easy exiting France and crossing Spain to get to Lisbon, especially with her parents in tow. Susan Zuccotti, in her book The Holocaust, the French, and the Jews writes: ‘Hoping to leave legally, Aline Strauss wrestled with government bureaucracies for weeks. Her top priority was to obtain entry visas to the United States for herself and her family – a supremely difficult challenge, for few such visas were being issued at the time. She also needed to secure French passports for herself and her family, transit visas through Spain and Portugal, French exit visas, and proof of ship passage. The entire process was complicated by endless bureaucratic obstruction and by the intricate time frame involved. Visas were often valid for only a limited period, and by the time they were all in place, a ship might have sailed. Miraculously enough, Aline Strauss finally succeeded. She left France with her son in January 1941; her parents, to avoid giving the impression of a family exodus, followed three months later.’ Apart from the ‘With one bound Jack was free’ nature of this adventure, one wonders whether concerns about ‘a family exodus’ would really have been that intense under the circumstances, and how Aline’s parents managed to organize their departure with similar dexterity in Aline’s absence. For a historian such as Zuccotti to go all the way to Headington House in Oxford to interview Aline Berlin, and take back no explanation of the ‘miracle’, is disappointing.

Did Aline get help? Did she have connections? Probably. As Chaim Weizmann once said to Berlin: ‘Miracles do happen. But one has to work very hard for them.’ And the account of the trek offered by her son, Michel, in his 2011 publication Pictures, Passion, and Eye is far more revealing, showing the tenacity and resolve she had to adopt. What Michel adds is that Aline had to make repeated visits to the US Embassy in Nice to get her exit visa, not being allowed to see the consul or vice-consul, since the necessary affidavits had not arrived from the US. After receiving assistance from the American Embassy in Vichy, she did manage to gain access to the vice-consul in Nice, and acquired the necessary visas. But then she was unable to acquire the necessary exit visa from the Vichy government, and had to start the whole process again, having to invent a justification for her journey by claiming that she was getting married in America. The Vichy government even demanded that the banns for such a marriage be read, until the Consulate lawyer issued a paper stating that in America, banns did not have to be read. Finally, she had the exit visas; the miracle had occurred, and she and her son made their way by train, from Barcelona to Madrid, and on to Lisbon – not without further scares – until they were able to rest at a small hotel in Estoril, in all probability not the Palacio, where Berlin was staying, to wait for the departure of SS Excambion. One surprising datum from the ship’s manifest, however, is the description of Aline Strauss’s marital status as ‘married’ not ‘widowed’ – a simple mistake, perhaps, or possibly a reflection of her desire to be taken as attached, and thus unavailable, by possible suitors on board. But she was on the less prestigious list of ‘Aliens’, for whom immigration officers performed additional checks. Was it not dangerous to represent herself this way, especially as the method by which she had gained an exit visa was a laborious and stressful process in which she claimed that she was to be married in the USA?

Who was Aline Strauss? She had been born Aline de Gunzbourg – in England, in 1915, away from the war zone – and had been brought up in an apartment block in the Avenue d’Iéna in Paris, enjoying contacts with some of the most celebrated names of French society, such as the Rothschilds. She was a close friend of Liliane Fould-Springer (a great-aunt of the actress Helena Bonham-Carter), who lived in another apartment in the block, and who was later to marry Elie de Rothschild, her childhood sweetheart. As Ignatieff reports: ‘Aline’s father was Baron Pierre de Gunzbourg, an illustrious banker and philanthropist of pre-revolutionary St Petersburg. Her father had settled in Paris and had married the daughter of a Jewish family from Alsace, who had made their fortune in heating oil.’ In fact, there was another Rothschild link here, because her grandfather had set up a company to sell American oil in other European countries with the Rothschilds. (There was also intermarriage between Rothschild and de Gunzbourg: for example Marguerite de Gramont (1920–1998), daughter of the Count de Gramont, Officier of Légion d’Honneur and Croix de Guerre, was later to become Baroness de Gunzbourg, and Aline’s cousin, Bertrand Goldschmidt – of whom more later – married Naomi de Rothschild, who was the daughter of Victor Rothschild’s cousin Lionel, in 1947.) Aline spent considerable time in the United Kingdom. She would pass several summers in a rented house in North Berwick with relatives, and regularly played golf in England with some of the world’s best-known players: she can be seen in photographs on the course at Stoke Poges, for instance, in the early 1930s. Indeed, she was a golfer of renown. After winning the National Ladies’ Championship of France in April 1934, she represented her country in the tied match against England, and, in July of that year, lost in the semi-final of the country’s International Championship to the eventual winner, Pam Barton. But Aline also had her share of tragedy. Her husband, Jules Strauss, a well-known art-collector, died young of cancer in 1939. She had also lost a brother (while he was a conscript in the army in 1933) and a sister (who fell to her death from a horse in an accident in Windsor Great Park in 1925).

The story now resembles a world conceived by Alan Furst, but with the clumsy plotting of Raymond Chandler. Aline Strauss had a few other encounters with Berlin in the US before their love affair blossomed, several years later, in England. The first few appear at first glance to be chance meetings at which the two really did not connect. From an inspection of Ignatieff’s biography, and Berlin’s Letters, they run as follows:

i) Berlin spots the elegant shy woman on the Excambion. (January 1941)

ii) They meet at the Rothschilds on Long Island, where Aline is playing golf with Cécile Rothschild. Isaiah is impressed; Aline less so. (undated)

iii) Aline visits Victor Rothschild’s apartment at the Hotel Pierre in New York, to find Isaiah there. She ignores him, since she is pre-occupied with gaining news from Rothschild about her brother Philippe, then working for the Resistance in France. (November 1942)

iv) Aline and Isaiah meet at a tea arranged by Victor Rothschild in New York. Berlin reports that ‘marriage has crushed her, she is meek and unhappy’, although Aline of course does not talk about any problems. (Spring 1946)

What has been going on here? Berlin was known for his perceptiveness about other people’s state of mind, but how has the callow Isaiah suddenly become an expert on woman’s psychology? And why the emphasis on the failure of these two engaging personalities to connect? The studied reinforcement of the distance between the two is overdone, and thus generates a degree of scepticism.

Many aspects of this account do not ring true. Aline Strauss was certainly ‘tall and elegant’, but hardly shy – although those who know her say that she is diffident in front of high-powered intellectuals. She was travelling with her son; she had moved in dazzling social circles, had been in the limelight in the world of golf, and had shown great enterprise and fortitude in escaping to Portugal while dealing with obstructive officials in Southern France. She was acquainted with several other passengers on the Excambion, and, upon her arrival in New York, left her son in the care of nannies in order to take up a hectic social life. There may have been more alluring companions on the ship than Isaiah Berlin, but it was unlikely that she shrank back to her quarters, or avoided company out of shyness. Even more telling, on the occasion of his marriage to Aline on February 8, 1956, Berlin informed a reporter from the Hampstead and Highgate Express that their first ‘meeting’ had been ‘in the middle of the Atlantic in 1941’. A ‘meeting’ suggests an introduction, and exchange of names, at least. So why did he tell his biographer that he wondered who she was?

The next two encounters also stretch the bounds of credulity. Here was a refined Jewish woman, attracted to intelligent men, being introduced to another Jew with roots in St Petersburg, while both of them had strong connections with the Rothschilds. Moreover, this was no ordinary Jew. Berlin was the first Jew to be elected to a fellowship at All Souls, and had been described as the best conversationalist in Britain (in truth, more of a monologuist), noted for charming both the men and the ladies with his quick-wittedness and intellect. His gift of good companionship, and his ability to lift people’s spirits, have been well-recorded. Yet Aline Strauss ignores him. And then, a few years later, Berlin meets her again, at a tea-party on Long Island, evidently not surprised to find her married (he makes no comment). Despite his lack of close acquaintance with the lady, he is immediately able to detect signs of stress, although Aline has been married for only a little over two years and is pregnant with her first son by Hans Halban, to be born on June 1, 1946. What is more, the archives indicate that her husband, who had also recently returned from a visit to the UK, was present at the meeting. It had apparently been set up by Victor Rothschild to facilitate the move by the Halbans to Oxford, where Hans was taking up a job at the Clarendon Laboratory, so that they would have ready friends there. How did this sophisticated lady, on such a happy occasion, with a birth imminent, at a positive meeting set up by their mutual friend, soon to welcome the arrival of her Resistance hero brother and his family in New York, and the prospect of an exciting new life in Oxford ahead, give such signals of attrition and stress to a man she had hardly noticed on previous encounters?

Were there problems with her marriage already? Certainly Hans Halban had had his difficulties. Halban was a nuclear scientist who was working on the Manhattan Project in Montreal. Ignatieff, again, does not quite get the story right. He reports that, in 1943, ‘Aline met Halban, a physicist of Austrian extraction who had worked on the French nuclear programme and had escaped to America in 1940, carrying with him important information about the production of heavy water, a component in the manufacture of atomic weapons.’ According to Ignatieff, they married and went to Montreal. But Halban’s journey had in fact been more circuitous, and tinged with controversy. Halban was indeed an Austrian, of half-Jewish descent, who had been educated at Leipzig, and worked with Irene Joliot-Curie, and with Niels Bohr in Copenhagen before being invited to Paris to collaborate with Frederic Joliot-Curie at the Collège de France, where he was granted French citizenship. As the Nazis approached, he had escaped with his colleague Lew Kowarksi to the UK with a valuable canister of heavy water (stored temporarily at Wormwood Scrubs, where MI5 was also located for a while, and then at Windsor Castle). Winston Churchill invited him to work at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge; he was greatly aided by John Cockcroft and Frederick Lindemann (later Lord Cherwell), both of whom became lifelong allies. Halban was eventually appointed to the technical committee of the Tube Alloys Project, the codename for research into atomic power and weaponry. His team was later reconstituted in Canada, in order to be close to the US atomic research efforts, and where resources for their experiments would be more available. Halban moved to Montreal in 1942.

But Halban had the knack of acquiring some highly dubious characters to work for him. The connections and conspiracies that evolved among his team constitute some of the most significant espionage activities of the century, and are worth listing. In Cambridge, he employed one Engelbert (Bertl) Broda, who was in fact a Communist agent (code-named ‘Eric’). Broda had come to the UK in 1938, found his way to Cambridge University, and was by 1942 assisting Halban in his work on atomic reactors and controlled chain reactions. In that seedbed of communist subversion, Vienna in the early 1930s, Broda had probably been the lover of another Soviet agent, Edith Tudor-Hart. Tudor-Hart was acquainted with the master-spy Kim Philby via the latter’s first wife Litzi Friedman, whom he married in Vienna in 1933, and may have been responsible for recruiting him to spy for the Soviet Union. Broda was eventually to return to Austria in 1947, having been a steady provider of atomic secrets to the Soviets in the intervening years. MI5 also suspected Broda of being responsible for the recruitment of the spy Alan Nunn May, who also worked for Halban – and followed him to Montreal in 1943. Nunn May was closely connected to the notorious group of Soviet agents known as ‘the Cambridge 5’. He was a friend of Donald Maclean at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, was tutored by the Communist sympathiser Patrick Blackett, and had joined the Communist Party on the early 1930s. He was able, however, able to get past security checks, as he was a ‘secret’ member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, and had been recommended by the prominent scientist James Chadwick to join the Cavendish team. He was recruited by the GRU (the Army side of Soviet intelligence) while on the Tube Alloys Project, and it was only through the testimony of the Soviet cipher-clerk Igor Gouzenko, who identified him after defecting in Toronto, that Nunn May was arrested, and subsequently confessed to his espionage activities. He was jailed in 1946, and when released a few years later, went to work in Ghana, having married Bertl Broda’s former wife, Hildegarde.

But there were other snakes in the grass who worked closely with Halban. Bruno Pontecorvo, the spy who suddenly defected to the East in 1950, had worked with him in Paris, and escaped to the US as the Nazis approached. He then not only gained employment in Canada under Halban, but also rejoined him at Harwell in 1948 under John Cockcroft’s leadership. Working there, too, was yet another notorious spy, Klaus Fuchs, maybe the most brilliant of them all. Having recruited Nunn May, Broda had been responsible for the KGB’s recruitment of Fuchs, who continued his spying activities after the war. In 1946, Fuchs was hired at Harwell as Head of the Theoretical Physics Division, and gave the Soviets some of the most critical and useful information about the USA’s nuclear achievements and potential, which directly affected Stalin’s military decisions, such as initiating the Korean War. When Soviet wartime radio traffic was decrypted in the Venona project, evidence pointed to a spy at Harwell, and Fuchs’s background made him an obvious suspect. He was arrested in January 1950, confessed under interrogation, and was sentenced to fifteen years’ imprisonment, though released after nine. He then left for the German Democratic Republic (DDR), (leaving London on a plane with a ticket in the name of Strauss!), and in September 1959 married a Central Committee employee, Margarete Keilson (a widow, six years older), whom he had met as a fellow Communist in Paris in the 1930s. He later indicated to Markus Wolf, the head of the DDR’s foreign intelligence division, that he had expected the death penalty. While Halban’s role was reduced in the post-war organization at Harwell, it was perhaps a signal of recognition for his skills and knowledge that so many spies gathered around him during his career.

While he tried to re-build, in Canada, the team that had worked for him in Paris (to the consternation of the Americans, who did not trust the French implicitly), Halban’s managerial skills were tested. His colleague Kowarski declined to accompany him to Montreal, frustrated by the politicization of dealings with patents, and Halban’s treatment of him. Later, another physicist on the team, Bertrand Goldschmidt, reported how the team was frustrated by lack of access to raw materials, and that ‘their demoralization was to be further increased by the difficult character, the authoritarian manners and the poor managerial abilities of Halban, their leader’. (Goldschmidt was in fact a cousin of Aline Strauss, and was the person responsible for introducing her to Halban in Canada when they were on a ski-ing trip early in 1943.) Despite his reputation for acting alone, and not being the best communicator, Halban had nevertheless managed to bring other members of his Parisian team to Montreal. One was Georg Plazcek (who married Halban’s first wife, Els Andriesse, after Els followed Halban to Montreal, but then left him); another was the afore-mentioned Communist agent, Bruno Pontecorvo. Pontecorvo had failed security checks for joining the Manhattan project in the USA, but had been able to get hired in Canada.

The Americans were very suspicious of Halban. Their misgivings increased when he visited France after the liberation of Paris in 1944, with the purpose of discussing the issue of patents with Joliot-Curie. They wondered whether he was planning to pass atomic secrets to the French. Knowing the situation was tense, Halban had travelled to England, but waited there for approval for his visit to Paris. On gaining it from Sir John Anderson, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, he left on November 24, and was given hospitality by the UK’s Ambassador to France, Duff Cooper, who was staying at Victor Rothschild’s elegant house in the Avenue Marigny. Halban had been caught in a complex conflict of loyalties. He had taken patents created in Paris with him to the UK in 1940, and given them to the UK government. And as the Americans started to wonder about why so many French scientists were working on the project in Montreal, they tried to apply stricter controls on participants without firm allegiances to the USA or the UK. This process resulted in the passing of the McMahon Act of 1946, which restricted access to nuclear secrets even to accredited citizens of countries who were US allies (like Great Britain and Canada), and thus solidified the preliminaries to the Cold War. Halban denied giving secrets to Joliot-Curie, but the Americans were annoyed, knowing that Joliot-Curie was a member of the Communist Party who had made threatening noises about contacting the Soviet Union if he were not treated respectfully. They thus applied pressure on the British to replace him – which they did, demoting Halban to head of the physics committee, and bringing in John Cockcroft as leader in Montreal. Nevertheless, Halban was soon put under detention in the US for a year, and not allowed to work. Ironically, the man who replaced him in Montreal was the spy Alan Nunn May. Any secrets that Halban might have confided to Joliot-Curie were dwarfed by the revelations of Nunn May, Fuchs, Pontecorvo and Broda, as well as those made by Guy Burgess’s fellow absconder, Donald Maclean, working in Washington.

The week of the meeting between Berlin and the Halbans that was set up by Victor Rothschild can be pinpointed, as Berlin completed his assignment in Washington on March 31, and left for the UK on the Queen Mary on April 7. Clearly, Halban had been under stress, which might have affected his marriage. Here was a man, born von Halban in Austria, of half-Jewish background, who was sometimes taken for a German, but who then adopted French citizenship (and dropped the ‘von’ from his name on that occasion) when he worked in Paris. After his escape to France, he was employed by the British government, and owed it his allegiance, signing the Official Secrets Act, before leaving to work in Canada in co-operation with the United States government. He was intensely concerned about the patents he had brought with him from France, and his loyalties were thus pulled in multiple directions. His health was not good: he had a weak heart, which had necessitated his travelling by cruiser rather than aircraft during the war, and Bertrand Goldschmidt attributes his dictatorial and impatient manner partly to that affliction. He was harsh with his stepson, Michel, who explained his own asthma attacks as being caused by Halban’s treatment of him: this must have distressed his mother. But in the spring of 1946, Halban was coming to the end of a frustrating nine months’ period of cooling his heels in New York, eagerly waiting for June to come round, a date on which he would be free to return to Europe. One might have imagined a positive outlook from both Halban and his wife.

Isaiah Berlin, on the other hand, had just returned from experiencing one of the most significant adventures of his life – his encounter with the famous Russian poet, Anna Akhmatova, in Leningrad. Berlin had been able to fulfill his longtime desire to visit the Soviet Union after the British ambassador in Moscow from 1942 to 1946, Archibald Clark Kerr, had suggested to him that he survey the scene, and write a report on relations between the Soviet Union and the West. Having carefully gained approval from the Foreign Office, Berlin was initially subject to obstructive tactics by the Soviet Foreign Ministry. Molotov eventually granted him official accreditation as a member of the British Embassy, and Berlin was given a visa in September 1945. It is ironic that Berlin breezed through his visa application with the Soviet authorities in Washington in 1940, before that particular journey was cancelled. Clark Kerr, made Baron Inverchapel in 1946, had shown a remarkable talent for engaging Stalin’s confidence, and no doubt influenced the approval process. The historian John Costello has written of Clark Kerr’s enthusiasm for communism. He had consorted with Stig Wennestrom, a Soviet spy from Sweden, in the 1930s, and in his role as ambassador to China in the late 1930s, had also been a keen admirer of Mao Tse-Tung. He then developed a special relationship with Stalin himself, going to so far as being a supporter of Stalin’s demands for the repatriation of Russians as the war came to a close. As Costello writes (in Mask of Treachery) ‘The ambassador was so cozy with the Soviet dictator that he secured the release from prison of a Red Army deserter whose sister was on the British embassy staff. Instead of facing a firing-squad, Yevgeny Yost found himself presented – like some medieval serf – as a valet to Inverchapel when he left Moscow and returned to London at the end of the war.’ Clark Kerr had also been a close friend of Guy Burgess, and, on visits back to London in the 1940s, held parties which communist sympathizers and Soviet diplomats attended: his suggestion that Berlin travel to Moscow was thus an eerie echo of the abortive exploit of 1940.

Ignatieff covers the journey in depth, so only the key aspects of his encounter with Akhmatova, whose first husband, Gumilev, had been executed in 1921, and whose son had suffered in the Gulag, need be retold here. On a visit to Leningrad, Berlin had casually asked about her in a bookstore, and had been led to her apartment. He ended up talking to her all night about Russian friends, about art and literature. She told him her bitter life-story, her love affairs, her exile, and encouraged him to speak of his own personal life. He admitted to her that he was in love with one Patricia de Bendern (née Douglas), whom he was to visit in Paris on his way back. (Extraordinarily, the previous August, Patricia, despondent after the collapse of her marriage, had proposed to Berlin, a suggestion which he assessed as unlikely to have a happy outcome, and thus declined.) What Akhmatova made of all this is unknown, but Berlin’s account of their meeting suggests it was erotically charged. At eleven the next morning, when he returned to the Astoria Hotel, he exclaimed to Brenda Tripp, his companion from the British Council: ‘I am in love, I am in love.’

Akhmatova went on to write a cycle of elegiac poems about Berlin and his visit, titled Cinque. But the encounter caused her problems, too. The fact that Berlin had eluded Stalin’s secret police in managing to meet Akhmatova infuriated the dictator, who had essentially been blackmailing her, forcing her silence in public by holding a sword over the head of her son. When Zhdanov, Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, sent him a report on the encounter, Stalin was reported to have said: ‘So our nun has been seeing British spies’, accompanying his reaction with a vulgar epithet. The matter was complicated by the fact that Randolph Churchill, the son of Stalin’s old rival Winston Churchill – sometime ally, sometime adversary – had also been present, according to Berlin’s account, outside Akhmatova’s residence. Seeking Berlin out, he had reputedly called boorishly to him, although he had not been able to gain entry. Akhmatova thought enough of her own importance, and the way Stalin behaved afterwards, to state to Berlin, years later, when she visited Oxford, that she thought their encounter provoked the Cold War – a probable overstatement, though an accurate insight, no doubt, into the fact that Stalin did not like to be thwarted or challenged. Akhmatova’s biographer Roberta Reeder makes the point that Stalin used her as a victim to teach a lesson to the Soviet people, and the writer Konstantin Simonov represented Stalin’s attack on her as a general one on the intelligentsia, cosmopolitanism, and even the independent westernized spirit of Leningrad itself. Stalin had delivered a speech in February 1946 that reaffirmed the superiority of communism, which in turn prompted Churchill’s ‘Iron Curtain’ speech in March, so the fresh challenge from his former ally was on his mind when he heard that Randolph was meddling.

Most commentators have pointed out that Stalin was exaggerating in describing Berlin and Churchill as ‘spies’, since Berlin’s mission to prepare a dispatch about American-Soviet-British relations had been approved by the Soviet Foreign Office. Eluding one’s minder was not evidence of espionage, but the Soviet authorities were obviously suspicious of any covert activity, or attempts to contact Soviet citizens without supervision. Berlin took pains to declare his lack of involvement with any intelligence activities at any point in his life. ‘I had nothing to do with intelligence in any country, at any time, and took no interest in what he [Alexander Halpern] did,’ he wrote in his profile of the Halperns, maybe a little disingenuously. (It should be pointed out that he informed his parents – in a letter of June 2, 1944, from Washington – that Halpern ‘works for us here’, suggesting a close familiarity with Halpern’s activities.) There is a difference between ‘having something to do with intelligence’ and ‘formally working for the Intelligence Service’, the latter being what Berlin appears to want to disassociate himself from. While nominally working for the British Embassy in New York and Washington, Berlin had actually been seconded to the assuredly covert British Security Co-ordination, an organization dedicated to propaganda and intelligence-gathering. And another little-known relationship that Berlin had in the world of intelligence was with Efraim Halevy, who was head of Mossad (Israel’s Intelligence Organization) from 1998 to 2002. A casual search of the Internet will give a careless browser the news that Halevy was Berlin’s nephew: he was in fact a nephew of Berlin’s aunt. Their relationship was close: Halevy was born in London in 1934, and his parents were friends of the Berlin family in Hampstead. Isaiah, along with his parents, attended Halevy’s bar mitzvah. But you will not find an entry for him in Ignatieff’s biography of Berlin. That is doubly remarkable, as the Letters, Volume 2, reports that Halevy accompanied Berlin on the 1956 trip to the Soviet Union. As the editors report: ‘As Secretary-General of the National Union of Israeli Students, he was in Moscow ostensibly to assist in planning for an international youth festival to be held in Moscow the following year, but his main intention was to make contact (normally impossible) with young Russian Jews.’ They go on to say that Berlin and Halevy did succeed in the early hours of one morning in getting away to meet Berlin’s aunt Zelma Zhmudsky, although Halevy was later reprimanded and delayed at the border for the ‘crime’ of escaping surveillance. More significant is the fact that Halevy delivered the seventh annual Isaiah Berlin lecture in Hampstead, London, on November 8, 2009, choosing the title: ‘Diplomacy and Intelligence in the Middle East: How and why are the two inexorably intertwined?’ After lauding Berlin’s contribution to the Jewish people, the Israeli nation, and the Rothschild Foundation, he went on to say: ‘Shaya, as we all called him, was not a neutral bystander as history unfolded before our eyes. He was often a player, at times a clandestine one, as when he met me in the nineties to hear reports of my many meetings with the late King Hussein of Jordan and his brother Crown Prince Hassan, who had been his pupil at Oxford. In retrospect, I regret not taking with me one of my secret recording machines to allow for these titillating exchanges to become part of recorded history. Alas, one more Israeli intelligence failure.’ That is hardly the evidence for someone who was never involved with intelligence, and to commemorate Berlin via a lecture on the subject suggests a pride in his achievements in that sphere. But this aspect of Berlin’s life is smoothly finessed, as is information about the Rothschild Foundation. Kenneth Rose’s biography of Victor Rothschild practically ignores that whole segment of Rothschild’s life. It appears that many people would prefer it to remain a mystery.

Berlin returned to the USA to tidy up his commitments in Washington, and to have the equally fateful meeting with the Halbans. But questions have arisen about his version of what happened in Leningrad. When György Dalos was researching his account of the event for his book The Guest From The Future, and interviewed Berlin in 1995, Berlin significantly downplayed the romantic aspect of his feelings. ‘No’, he said, ‘there was no Utopia for me’, and his feelings towards Akhmatova were expressed in terms of fascination, respect, admiration and sympathy – not love. Perhaps he said so to protect the feelings of his wife, Aline, whom he had taken to the Soviet Union in 1956, and whom Akhmatova, possibly with a sense of jealousy, but also because she was fearful that the thaw in the oppression of writers such as her might only be temporary, declined to see. Berlin always stated that his meeting with Akhmatova was the most important event of his life, but he felt guilty for the mayhem that occurred afterwards – including the growing anti-semitism in the Soviet Union that was fostered by Stalin. (Akhmatova was not Jewish, but Berlin had relatives who suffered under Stalin’s persecution.) The focus of that new purge, the uncovering of a so-called ‘Doctors’ Plot’, was derailed only by the dictator’s death in 1953, a couple of days before those indicted were to go on trial. By the time Berlin returned to the Soviet Union in 1956, matters had improved considerably. Khrushchev’s celebrated speech debunking Stalin (February 1956) had resulted in a release of political prisoners, including Akhmatova’s son, Lev, who was freed on May 14 and officially exonerated by the Supreme Soviet on June 2, shortly before the Berlins arrived. Akhmatova had not been re-admitted to the Writers’ Union, and still felt threatened, but there is no doubt that she felt peeved at the realisation that her ‘Guest From the Future’ had turned out to be just like other men, and had transferred his affections to someone else. Berlin himself reported the long silence on the telephone after he spoke to Akhmatova about his marriage, a pause followed by: ‘I am sorry you cannot see me, Pasternak says your wife is charming’, after which came another long silence. Roberta Reeder, in Anna Akhmatova: Poet and Prophet, writes: ‘Her grief and disappointment, as in the past, were transformed into poetry, into a cycle entitled Sweetbriar in Blossom’, in which Akhmatova compares herself to Dido abandoned by Aeneas.

Later commentary, namely Josephine von Zitzewitz’s article in the Times Literary Supplement of September 9, 2011,‘That’s How It Was’ (effectively a review of a book published with that title, ‘I eto bylo tak’, in St Petersburg in 2009) represented further research into records from contemporaries at the scene, as well as study of archives in Britain. This analysis suggests that Berlin must have known that Akhmatova was still alive beforehand, that the original encounter may not have been as spontaneous as suggested, that there may have been further encounters between Akhmatova and Berlin (namely five, to match the number in Cinque), that details of those present are incorrect, that the incident with Randolph Churchill was invented, and that the meetings may have been more intimate that Berlin admitted. One key plank concerning the first part of this claim, not explained in the piece, is Berlin’s friendship with Alexander and Salomea Halpern (née Andronikova). Berlin had been introduced to this couple by a friend in New York, found them appealing (especially Salomea), and they became close friends. Salomea had been a noted beauty, and a very close friend of Akhmatova’s in pre-war St. Petersburg, sharing a circle including the poets Tsvetaeva, Mandelstam, and Akhmatova’s husband, Gumilev. Indeed, Mandelstam had fallen deeply in love with her. It seems inconceivable that Salomea Halpern would not have besought Berlin to try and visit Akhmatova while he was in Leningrad, yet Berlin later claimed to have asked naively inside an antiquarian bookseller’s whether she was still alive. (In a letter to Maurice Bowra, dated June 7, 1945, he refers to Akhmatova’s forced seclusion at that time in Leningrad, thus showing knowledge of her status.) This association has further wrinkles: Alexander Halpern, like Berlin, worked for the British Security Coordination in the US, helping to set up propaganda on a dummy radio station in Boston, and his role as head of Special Operations Executive’s (SOE’s) Political and Minorities section included responsibilities for the sensitive category of Ukrainians. Moreover he had been an official in Kerensky’s Provisional Government in 1917, as well as being an advisor to the British Embassy in St. Petersburg. If Stalin’s intelligence network had been doing its job, such a relationship would surely have come to his attention. Salomea herself was an enigma: by the 1950s she had become a rabid Stalinist herself, and when she moved to London after the war (so Berlin himself informs us), Russian writers were encouraged by the Soviet authorities to visit her primitive salon in Chelsea. ‘Salomea’s opinions were evidently noted favourably in Moscow’, notes Berlin.

The conclusions of Zitzewitz’s article are enigmatic: Berlin may have wanted to protect Akhmatova, but it does not explain why, since Akhmatova died in 1966, he would have needed to continue to shield her from the facts concerning his visit when he recalled the encounter, both in his 1980 essay Meetings With Russian Writers in 1945 and 1946, and in his conversations with Ignatieff shortly before he died. Moreover, a faulty memory cannot really explain all the distortions of the truth. As in other aspects of his life, Berlin frequently presented facts in a disturbingly deceptive manner. Akhmatova challenged Berlin on his sense of reality: after she received an honorary degree at Oxford in June 1965, she visited the Berlins at their opulent Headington House, and declared: ‘So the bird is now in its golden cage.’ (She then went on to have a long-awaited reunion with her close friend, but now a political adversary, Salomea Halpern, in London.) Ignatieff notes that, after Akhmatova’s death, Berlin wrote to a friend, Jean Floud, that he would always think of her as an “uncontaminated”, “unbroken” and “morally impeccable” reproach to all the Marxist fellow-travellers who believed that individuals could never stand up to the march of history. This avowal was doubly ironic: Jean Floud was the sister-in-law of another Soviet agent, Bernard Floud, and she misguidedly came to his defence in a letter to the Times. And Berlin would later undermine his heartfelt comment about fellow-travellers in his praise of another woman.

In April 1946 Berlin returned to England, and Oxford. The Halbans sailed back on July 1; Peter had been born on June 1, and their two children followed them on the Queen Mary in September. Berlin resumed teaching at New College, now a celebrity with a reputation gained from his Washington dispatches. Hans Halban was pleased to assume a post as Professor of Physics at the Clarendon Laboratory, after an offer from his old friend Lord Cherwell. By all accounts, he had eight successful and productive years working there. At first, the Halbans lived in a rented mock-Tudor house outside Headington; a year later, the family moved into Hilltop House ‘a finely proportioned Georgian House with a large garden at the top of Headington Hill’, as Michel Strauss reported. In 1953, Aline and Hans found a larger Georgian house on six acres of land in Old Headington, Headington House, which was to become the Berlins’ domicile after Hans and Aline divorced, and Hans moved back to France, in 1955. As Victor Rothschild had hoped, Isaiah became good friends with the Halbans during the next few years. Ignatieff relates: ‘Isaiah became part of their life, taking Aline to concerts, dining at their house and gradually becoming a family friend. She felt at ease with him; he made her laugh and provided her with a safe and blameless escape from a marriage that was becoming more difficult by the year.’

An example of this new intimacy was apparent in 1949. The way Ignatieff reports it, it was an accident: ‘when he went to Harvard, she was on the same boat heading to visit her mother in New York, and they spent ten happy days together on a crossing which included Marietta and Ronald Tree and other friends.’ The least ingenious of sleuths might conclude that there had been some planning to this highly enjoyable voyage, perhaps a subtle twist to Graham Greene’s May We Borrow Your Husband? Berlin’s diligent amanuensis, Henry Hardy, and his co-editor, Jennifer Holmes, inform us that Berlin had indeed suggested that Aline join him and his friends on the voyage, and she travelled from Paris to pick up the Queen Mary when it docked at Cherbourg. As luck would have it, the ship, driven by a gale, ran aground there, and had to limp back to Southampton for repairs. Isaiah and Aline took the opportunity to leave the rest of the party marooned in a dock on the Solent, and to return to Oxford until the ship was ready to sail again. Earlier, as he waited off the Isle of Wight on January 2, while the ship was being inspected by divers, Berlin wrote to his parents: ‘Life is terribly gay & agreeable: breakfast in bed with every kind of delicious juices & eggs: then promenades with Mrs Halban, the Trees, Miss Montague, Alain de Rothschild’. Ignatieff (provided with this insight by Isaiah and Aline in the 1990s) states that it was on board ship that they became inseparable friends, but the evidence suggests that they had already formed a strong bond. And at some stage they started an affair. Michel Strauss confides that his mother used to have trysts with Isaiah, before their liaison became official, in a flat in Cricklewood (a touch that would have delighted Alan Coren). Michel also informs us that Hans Halban had been seeing Francine Clore (née Halphern), a cousin of his mother’s, in the 1950s, ‘at the same time my mother was seeing Isaiah Berlin’. The gradual dissolution of the marriage, and the new re-groupings, were becoming obvious to their friends.

Halban’s social stature had improved in his time at Oxford. A significant feather in his cap was being elected to one of the initial fellowships at St Antony’s College. The College (for graduates only) had been founded in 1950 by a bequest from a successful French businessman with merchant interests in the Middle East, Antonin Besse. After some preliminary stumbles in negotiation between Besse and the University, Bill Deakin had taken over the Wardenship of the College, impressing Besse with his common sense and vision. Deakin (who had worked with Isaiah Berlin in Washington during the war) was a historian who had seen fierce action with SOE among the guerrillas in Yugoslavia, and had acted as literary assistant to Winston Churchill in the latter’s historical writing. While Deakin had been a fellow at Wadham College, many of the initial staff members were from New College, and Isaiah Berlin had been very active in advising the Warden on appointments and administration. Halban was offered a Fellowship; when interviewed in 1994 by Christine Nicholls, the historian of the college, Berlin said that it was because Lord Cherwell had thought it a good idea that a scientist be represented – a somewhat surprising explanation, given that the mission of St Antony’s was to improve international understanding, and diplomacy had not been the strongest arrow in Halban’s sleeve. Maybe the fact that the elegant Mrs Halban would be able to join in social events was an extra incentive. Indeed, Headington House had its uses. As Nicholls’s History of St Antony’s College reports: ‘The grandest social event of all was the ox-roasting. In 1953, at the time of the Queen’s coronation, an Anglo-Danish committee, on which Deakin sat with a Danish chairman, wanted to do something to thank Britain for its help in wartime. The chairman asked Deakin whether his college would like to roast a Danish ox ….. Hans Halban and his wife Aline, who had a large house with land on Headington Hill, agreed to the roasting taking place there.’

The choice of Fellows was a little eccentric. A certain David Footman was elected at the same time as Halban. His expertise lay in the Balkans and the Soviet Union, but he had been dismissed from the Secret Service because of his support for Guy Burgess. Intriguingly, Deakin, who enjoyed fraternizing with Secret Service personnel, had said he wanted a Soviet expert who was free of any commitment to Marxism, and therefore welcomed Footman to the college. But there were questions about Footman’s loyalty: the Foreign Office did not give him a clean bill of health, and Sir Dick White (who headed both MI5 and MI6 in his career) admitted he should have been more skeptical about his trustworthiness. Footman had had contacts with the Soviet spy-handler Maly, and, when Guy Burgess defected, Footman was the first to be notified of the event by that dubious character Goronwy Rees, close confidant of Burgess; Footman in turn informed Guy Liddell – Victor Rothschild’s boss in MI5. Thus the first appointments at St Antony’s were very much made by an old-boy network, about which Berlin must have eventually had misgivings. As early as 1953, he was to write to David Cecil, when looking for advice on career moves: ‘In a way I should prefer Nuffield because St Antony’s seems to me (for God’s sake don’t tell anyone that) something like a club of dear friends, and I should be terribly afraid that the thing was becoming too cosy and too bogus.’ His words got back to the sub-warden at St Antony’s, James Joll, who had also lectured at New College and had been a pupil of Deakin, and Berlin was duly chastised. (James Joll was later to receive a certain amount of notoriety by virtue of his harbouring Anthony Blunt when the latter was being hounded by the Press after his public unmasking.) In any case, the chroniclers at the college did not seem surprised when the Halban marriage fell apart. The History laconically reports: ‘Halban remained at St Antony’s until he resigned on October 1, 1955, upon taking a chair at the Sorbonne. When Halban resigned his fellowship and left for Paris, he asked his wife to choose between Paris and Berlin. She determined on the latter and became Isaiah Berlin’s wife.’ The source was James Joll. After returning to France as a professor at the Sorbonne, Halban was invited to direct the construction of a nuclear research facility (a large particle accelerator) at the Orsay facility in Saclay, outside Paris, for the French Energy Commission. When the divorce between Mr and Mrs Halban was finalised, Isaiah and Aline were married at Hampstead Synagogue on February 7, 1956, with Victor Rothschild as Aline’s witness. For over forty years, they enjoyed a stable, loving, and rewarding marriage. Practically the last thing he said to his biographer was how much he loved Aline, and how much she had been the centre of his life – no doubt a sincere claim, but one made with the intent of comforting Aline and stilling any doubts she may have had about competition from other relationships.

There was, however, at least one more twist to the story before Isaiah and Aline were able to be together. Berlin had seemed to be destined for the life of a bachelor: his correspondence shows that he was able to keep up a lively and affectionate dialogue with attractive young females, but they did not appear to view him as romantic material. (One exception was a pupil, Rachel Walker, of Somerville College, who fell in love with him, but whose attentions he found discomforting.) In the early 1950s he still professed to be in love with Patricia de Bendern, even as she misused him, continually playing with his affections. Moreover, Berlin had been telling friends he wanted to get married. Then, out of the blue, in the summer of 1950, Berlin started an affair with the wife of an Oxford don. When Ignatieff wrote his biography, the woman’s identity was thinly veiled, but the story came out when Nicola Lacey published, in 2004, her biography of the woman’s husband, H. L. A. (Herbert) Hart. Hart was a prominent professor, one of the great legal philosophers of the twentieth century. Berlin had known Jenifer and Herbert for a long time; indeed, Henry Hardy describes Jenifer as ‘a close and lifelong friend of IB’. Herbert was a don at New College, and Jenifer had been an admirer of Berlin’s intellectual talents ever since she first met him. Unlike Aline Berlin, who claimed to struggle to understand what he was saying at their first encounter, Jenifer Hart recorded in her own memoirs, Ask Me No More, her first impression of Berlin, in 1934: ‘It was here [New College] that I first met the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, whose conversation I found so dazzling that, already in an excited state, I was almost reduced to hysterics.’ Ignatieff describes the historic seduction as one initiated by Berlin when he was sick, and Jenifer came to visit him: Hardy and Holmes note that, much later, both Isaiah and Jenifer would claim that the other initiated the affair. Berlin’s state of mind was probably at a low point; on May 11, 1950, Aline Halban gave birth to her third son, Philippe, her second with Hans. For what Berlin had gauged as a rocky marriage several years ago was perhaps re-energizing itself, and his opportunity was fading. Isaiah was anguished over his affair with Jenifer, believing that he had to explain himself to the husband, also a close friend; Herbert Hart (who had homosexual tendencies, and once declared to his children that the problem with their parents’ marriage was that ‘one of the partners didn’t like sex, and the other didn’t like food’) refused to accept the reality of the situation. The Nobelist Mario Vargas Llosa has written about Berlin’s ‘adulterous affairs with the wives of university colleagues’, which makes Berlin sound like a satyr of Ayeresque proportions. It is possible that Llosa has inside information that would expand the list of Berlin’s amours: no other lady, apart from Mrs Hart and Mrs Halban, has been identified, but of course it is as difficult to prove that somebody definitely did not have another lover as it is to prove that any senior British Intelligence officer was for certain not an agent of the Soviets. (Though the sexual mores of the intelligentsia of that time seem bizarre even in this enlightened age: Isaiah Berlin was in love with Patricia de Bendern, who was sleeping with A. J. Ayer, who was two-timing her with Penelope Felkin, who was married to Elliott Felkin, who had been the first lover of Jenifer Hart, who initiated Berlin into sex: a veritable La Ronde on the Isis.)

And here the timing looks a little awry. It is impossible to plot the exact trajectory of the affair of Isaiah and Aline, since the prime source of facts about it is Berlin himself, and he has proved to be an unreliable witness, events blurring from a faulty memory forty years later, and maybe a desire to believe that the course of true love had been more honourable than it really was. Ignatieff writes that ‘the affair continued for several years, but Berlin’s affections slowly began to transfer towards another woman, also married to an Oxford colleague’. Berlin’s affections for Aline had of course been harboured for many years already: in a letter to Alice James (August 12, 1955), he writes about his impending marriage: ‘I have loved her long and very silently for fear of upsetting what seemed to me a household.’ And then, after claiming his innocence, and rather ingenuously stating that ‘No “deeds” occurred’, he writes further: ‘I am naturally in a state of enormous bliss; & think myself fantastically lucky & cannot conceive how such happiness can have come my way after eating my heart out for years (I first saw her in 1941) nor does Dr Halban seem to mind much now’. It seems very incongruous for a man who had loved in vain for all those years to have set upon a sudden affair with another woman only five years previously, and indicate to his biographer that his affections slowly began to transfer to another woman. In any case, the usual accompaniments to such affairs took place: secret assignations, surreptitious telephone calls overheard, private detectives tracking movements, confrontations, temporary separations and tearful reunions. Berlin tried the same tactic of confronting Halban, pointing out to him the philosophical challenge of trying to keep caged someone yearning to be free (neatly paraphrasing a saying of Herzen about the impossibility of providing a house for free people within the walls of a former prison), and how such behavior would be counterproductive. At the end of 1954, another deus ex machina saved the situation. Halban was offered the position in Paris, and gave Aline the famous ultimatum. She decided to stay: Halban somehow must have been persuaded to give up Headington House, no doubt with some monetary payment to assist the process, and after waiting for the divorce to come through, Isaiah and Aline became engaged. Jenifer Hart happened to hear the news at an All Souls lunch, and was notably shocked and upset. According to Ignatieff, she came to Isaiah’s rooms and he could only comfort her as best he could: ‘Cry, child, cry’ (since emended by Henry Hardy, after inspection of the tapes, to ‘Weep, my child, weep’). Marx and Belinsky meet Mills & Boon.

Yet Jenifer Hart’s world contained another momentous secret: she had been a member of the Communist Party, and a Soviet agent, suspected by MI5 of passing on secrets from the Home Office to her Communist handlers. In her autobiography, Hart makes no secret of her Communist affiliation, but claims that she abandoned her allegiance at the time of the Nazi-Soviet pact in 1939. (Protestations made by former Soviet agents under gentle Security Service interrogation are notoriously untrustworthy, as the experience with Anthony Blunt showed. Unfortunately, statements made by their more innocent friends, such as Rothschild and Berlin, likewise have to be treated with circumspection.) She was one of the group that regularly mingled at the apartment in Bentinck Street that Victor Rothschild rented to Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt. Others are not so sure that she abandoned her role in espionage that soon. The historian Professor Anthony Glees even lists her, in his Secrets of the Service, in a rogues’ gallery of Soviet spies, in the same class as Blunt, Philby, Maclean, Burgess, Long and Fuchs; other analysts, such as the veteran tracker of communist subversion, Chapman Pincher, consider her as relatively small fry. But there seems no doubt she was a traitor. She concealed her membership of the Communist party, being told by her masters to go underground. She gained employment at the Home Office, where she had access to information on telephone taps, without declaring her affiliation, and signed the Official Secrets Act. She married Herbert Hart, and recommended him for work at Bletchley Park, where he worked on decrypts of Nazi radio traffic. Glees believes that she would have had to pass on secrets to prove her commitment to the cause: that was the pattern that the Stasi followed in East Germany, and what the KGB demanded of its agents in the UK and the USA. Her role was revealed by Anthony Blunt and his associate Phoebe Pool, who was incidentally a very close friend of Jenifer Hart’s. Pool stated that Hart had been recruited by Bernard Floud – another agent in the Oxford Ring that mirrored the Cambridge Five – who committed suicide shortly after being interrogated by MI5. Arthur Wynn, another recently uncovered agent, was her handler. She might have escaped more public attention, but she made some unguarded comments to a journalist in 1983, expressing overtly unpatriotic opinions, which provoked interest in her all over again, actions which caused her to threaten Professor Glees. She blustered, but eventually backed down from the threat of a libel action, as her previous disloyalty was undeniable. As Markus Wolf, the Chief of Foreign Intelligence for the German Democratic Republic, wrote in his memoirs, Man Without A Face: ‘No co-operation with an intelligence service will ever leave you. It will be unearthed and used against you until your dying day.’ Moreover, Hart’s life was one of hypocrisy: she claimed to be a socialist, but clearly believed that socialism was not for her, as she took advantage of all the benefits of a liberal education, watched her investments (like that other armchair socialist A. J. P. Taylor), sent her children to public schools, jointly inherited a large house in Cornwall, and travelled around the world with her husband on the proceeds of a trust established by an American entrepreneur. And as the cycle of Berlin’s life came to a close, she revealed in the book a last ironic twist: Aline de Gunzbourg had been a schoolmate of hers in Paris, and she included in the memoir a photograph of her class at the Cours Fénelon, which clearly identifies herself and Aline.

All this might not affect Isaiah Berlin’s legacy, except for the fact that he wrote a very flattering foreword to Hart’s memoirs just before he died. (The volume was published only after his death in 1998.) In some matters, he was blunt. He spoke of Hart’s betrayal of her husband. He named Michael Oakeshott, the conservative philosopher, as an early amour, and added: ‘Nor was he her only lover’, but did not divulge that he himself was one on that list. And he showed some awareness of her shady past. He recognized her communist commitment, but was indulgent with her failing. ‘At any rate, Jenifer was much taken in by what I have described, and that is what made her drift towards the Communist Party; a great many friends had done the same, and in peaceful, civilized England communism must have seemed mainly a strong remedy against illiteracy and injustice, an illusion which persisted in the West for a very long time.’ He even recognized her role as a Soviet agent while working at the Home Office, but was inclined to give her the benefit of the doubt. ‘The Party was probably pleased to have an agent in so sensitive a place, but in fact Jenifer never did anything for the benefit of the Party – gave no secret information – this has never been refuted in all the examinations of Soviet penetration that took place in later years.’ How did Berlin know that for sure? Did he really believe it? (The only sure fact about the whole affair appears to be that there is no record of Clement Attlee’s receiving a report from MI5, and then commenting: ‘So our monk has been seeing Soviet spies.’) But what reflected really poor judgment was his going overboard in his testimony to Hart’s character: ‘Before her unyielding integrity, her acute moral sense, even the cynical or complacent or indolent or wheeler-dealers, were bound to quail, or at least feel uncomfortable.’ There is a world of difference between having vague sympathies for Communism (such as Berlin himself might have harboured had he not been inoculated in his youth by the barbarity of the Revolution), and breaking an oath of loyalty to one’s government to betray secrets to a foreign power. So is this the implacable foe of Soviet totalitarianism, disgusted by the violence he saw as a boy in Petrograd, and by the cruelty of Stalin’s institutionalized terror that he witnessed in the 1950s, speaking? Is this the man who would not stay in a room with Christopher Hill because of his ideology, and who prevented Isaac Deutscher from getting a chair at Sussex University because of his totalitarian sympathies? Berlin liked to see the positive aspects of people he knew (witness his Personal Impressions), but he could have performed a favour for an old friend and lover without putting her on a false pedestal.