The Death of a Cambridge Spy

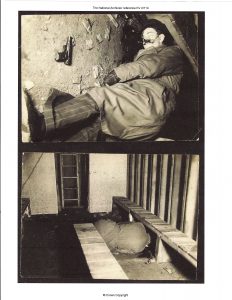

“Warning: Some images may cause distress” (I reproduce this warning verbatim from the folder on the Abwehr spy Willem ter Braak at the National Archives. When you read down, you will see the reason for the caution. And the analysis behind this photograph suggests some highly controversial behaviour from British counter-intelligence in WWII, explored here in depth for the first time.)

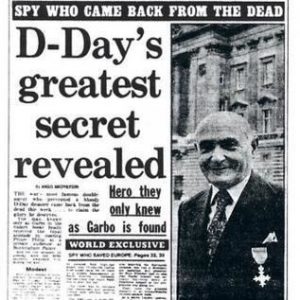

It has long been an article of faith that British Intelligence controlled all the Abwehr spy networks in Britain during World War II. On July 15, 1942, Lieutenant-Colonel Robertson, identified as B.1a in MI5, reported to the W Board that his organisation controlled all the active networks of spies originally deployed by the Abwehr in Britain. In his book The Double-Cross System, published in 1972, John Masterman boldly declared that ‘we actively ran and controlled the German espionage system in this country’. This opinion was endorsed by Sir Michael Howard in Volume 5 of the authorised History of British Intelligence in the Second World War, issued in 1990, who reported that ‘the Radio Security Service had discovered no uncontrolled agents operating’. Very soon after Robertson’s submission, Colonel J H Bevan, head of the London Controlling Section of the Chiefs of Staff Committee, attended a meeting of the XX Committee. The great deception programme could begin.

The importance of this claim has two dimensions. At the time, it was critical that no undetected network of spies could send reports back to Germany that countered the false information that was going to be transmitted by the double agents, such as a lack of substance behind the reported movements of a dummy army that would turn out to be the most critical aspect of the FORTITUDE deception campaign for the invasion of Europe. Even more critical, perhaps, it was vital that no leakage of information arrived in Germany to suggest that any spies had actually been turned. Historically, it became a matter of pride that the combination of disciplined reception procedures, rapid decisions on the viability of double agents, and interception of Abwehr radio intelligence confirming both the activities of planted agents and the acceptance of their stories, had conspired to eliminate the possibility of any agent’s survival undetected. In particular, the reputation of the Radio Security Service (RSS) for comprehensive interception of illicit transmissions was at stake. This was one of the major stories of British intelligence success in World War II.

Yet doubts occasionally surface about how watertight the processes were. It should be noted that Sir Michael Howard did not assuredly declare that no agents were operating, but merely that the RSS had not discovered any. Guy Liddell, the wartime head of counter-espionage in MI5, also suggested in the summer of 1940 that there might be a few German agents at large. It would be useful had the authorities provided a comprehensive table of all German agents captured, and what the outcome of their detention was. Howard tells us that sixteen spies were eventually executed, of whom nine met their deaths between December 1940 and December 1941. Volume 4 of the authorised history contains several Appendices that list agents and their fates, but it is not inclusive. Masterman’s Double-Cross System provided a list of thirty-nine double agents, which contains details on each agent’s method of communication, tasks undertaken, as well as the reason for the conclusion of the case, but did not identify them by name. When the magazine After the Battle, in issue Number 11 of 1976, reprinted Masterman’s list, it added some information, such as giving real names, where it could. In his history, MI5, Nigel West extended the number to list forty-seven double agents, a roster that does not include fictitious ‘notional’ agents created to add verisimilitude and vigour to a real agent’s recruitment efforts. After the Battle also offered in-depth profiles of the sixteen who were executed, a list that is confirmed exactly by West (pp 342-343), who also lists two spies executed in Gibraltar.

But were all agents truly detected? And was the outcome solely execution or being turned? The latter dilemma was a subject of intense negotiation between MI5 and Lord Swinton of the Security Executive, who represented Churchill’s preferences. In the heat of the Battle of Britain, Churchill wanted to see more spies executed, as a signal to warn others, and as a show of efficacy to the British public. MI5 was of a more cautious bent, wanting to preserve captured agents as an element to be turned, or a source of information, although it accepted that some spies would have to be executed in order to show the Germans a (partially) successful programme of arrest and conviction, as well as a degree of ruthlessness. The Abwehr would have been perplexed if none had been captured and condemned. Yet there were risks as well. Should a turned spy turn out to be unreliable, or his usefulness to be outworn, a decision on his treatment had to be made. A public trial might expose too many secrets about the process, and if the agent had misled his controllers about his sincerity, he might constitute a serious security risk even if incarcerated. A year later, MI5 had to deal with the realities of deals made, and gone sour, in the case of SUMMER (Gösta Caroli), as Hinsley explains: “In November 1941, however, in discussions held between Swinton, MI5, the DPP and the Attorney General about SUMMER and GANDER, whose careers as double-agents had come to an end, it was agreed that no question of prosecution could arise if MI5 had used an agent or given him a promise: the risk that an agent’s double-cross work would be revealed in court had to be considered; and a promise once given had to be honoured. MI5, to avoid undue publicity, should prepare a statement to be approved by the Home Office before release to the Press through the Ministry of Information.”

It can be seen that MI5 faced a wrenching choice: if a trial and possible execution were not possible, a potentially dangerous agent (especially if he had been exposed to the Double-Cross, or XX, System) would have to be incarcerated and held incommunicado in order to preserve secrecy. Thus uncertainty rests over those agents who evaded capture for any period of time, and over those whose career ended in untidy circumstances, such as Caroli, who in fact broke his side of the bargain, as I shall explain later. The history of these individuals makes the simple conclusions of most accounts of the Double-Cross operation much more complex. This chapter discusses a few of those who fall into those categories, with special attention to the puzzling case of the Dutchman ter Braak (real name Engelbertus Fukken), who was reported to have committed suicide after parachuting into the Buckinghamshire countryside and successfully evading the authorities – including RSS – in the winter of 1940-1941.

The suspicion that the authorised accounts are not complete is reinforced by the occasional comment from Guy Liddell’s Diaries. For example, on August 21, 1940, he wrote: “H. K. BRUIN came over in guise of refugee from Holland, had wireless set he had been using to communicate weather and other information to Germans. Self-confessed agent working for Dr. Rantzau. Is this a shooting case?” Liddell indicated that BRUIN had been active for a while, since one of his goals had been to alert his bosses about British troop movements into Belgium. Yet we never learn how BRUIN was detected, whether an attempt was made to turn him, or whether he simply went to trial. It is an astonishing entry that completely undermines the clean story that has been presented since. On September 14, Liddell also notes that KUHIRT and SCHROEDER are expected to arrive, but that is the only reference to them.

One major assumption that British intelligence made was that the Abwehr was exclusively responsible for placing agents in Britain. In 1981, the journalist and historian Leonard Mosley (no relation to the fascist, Oswald) published a book title The Druid, which claimed that the Sicherheitsdienst (identified by Mosley as the SS, but an abbreviation which probably indicated the German Security Service rather than the familiar SS, the Schutzstaffel, under which the Sicherheitsdienst was originally created), dismayed by the quality of intelligence it was gaining from Admiral Canaris’s Abwehr, in May 1941 parachuted in a spy with ties to Welsh nationalists who survived the war, reporting alongside the set of turned agents. Mosley had been fed with enough leads by his contacts in intelligence to believe that the story was true, but had been hushed up. Yet any substance of truth in his account was overwhelmed by the way his informers embroidered it, and by the many fanciful touches he introduced, with the result that it is very difficult to identify reliable facts among the many fictions. In his 1998 study of bogus memoirs of espionage exploits in WWII, Counterfeit Spies, Nigel West effectively demolished Mosley’s narrative, concluding that ‘most of the book can be traced to three published sources: Ladislas Farago’s The Game of the Foxes; Masterman’s The Double-Cross System in the War of 1939-45 and Popov’s Spy Counterspy.’ [Note: Mosley was an accomplished and careful historian: I have recently read his excellent 1978 biography of the Dulles siblings John Foster, Eleanor and Allen, which also happens to contain some revealing letters to the author by Kim Philby, written from Moscow, as well as Mosley’s absorbing account of the period leading up to the Second World War, On Borrowed Time, published in 1966.]

A Tale of Two Schmidts

A last misconception that has refused to die is the account that appeared in Charles Wighton’s and Gunter Peis’s Hitler’s Spies and Saboteurs, the title used when the book appeared in the USA in 1958. We should recall that this was well before the date (1972) in which any details of the Double-Cross System were made available to the public. Wighton and Peis, claiming to have had access to the diaries of the head of Abwehr Abteilung II (Sabotage and Subversion), General Irwin Lahousen, described in detail some of the exploits of Abwehr spies in Britain. Apart from a chapter that revealed an enormous amount of detail about Arthur Owens (whom we know as SNOW), the authors laid out a convincing account of how two Danish agents had been recruited by the Abwehr in the summer of 1940, and parachuted in to Wiltshire. One, Jorgen Björnson, severely damaged his ankle on landing in a tree, while his companion, Hans Schmidt, came to earth successfully, located his injured colleague, walked into Salisbury for provisions, contacted Hamburg by wireless, and arranged through the Hamburg station for SNOW to set up a sympathetic doctor to attend to Björnson’s ankle. Björnson was soon captured and incarcerated, but Schmidt roamed free, picking up intelligence in southern England. After a breather in Wales to evade the radio monitors, whom Hamburg suspected were closing in on its agent, Schmidt resumed his espionage activity, even found work on a farm, married, and had a child, and continued transmitting his information to Germany until April 1945.

This book does not appear to have been challenged by any authority at the time. After all, despite the authors’ lack of awareness of the Double-Cross project, too many facts were close to the truth, and drawing attention to the activities of these German agents might have allowed some skeletons to escape from the closet before the authorities were ready to share their secrets. Many years later, in the issue of the magazine After the Battle referred to above, the editor and sleuth Winston G. Ramsey listed They Spied on England (the original UK title of Wighton’s and Peis’s book) as a source of information, but made no mention of Björnson and Hans Schmidt – apart from a careless but understandable error of expanding on Masterman’s list of double-cross agents by identifying TATE as Hans Schmidt, when in fact it should be Wulf Schmidt. And herein lies the key to the mystery. There was only one Schmidt.

Yet the story resurfaced in 2017. Last year Bernard O’Connor published a book titled Operation LENA and Hitler’s Plots to Blow Up Britain, an account of Abwehr incursions into British and Irish – and US – territory between January 1940 and the end of the war. (Operation LENA was the name given to the undertaking to infiltrate spies and saboteurs to Britain in late 1940 to prepare for and facilitate the imminent invasion of Britain by the German forces.) This volume appears to be a very thoroughly researched book, cataloguing a series of initiatives by the Abwehr to cause havoc, or gain intelligence, in Eire and Great Britain, and it is liberally sprinkled with references to the archives. O’Connor reproduces as fact, however, the whole story of Björnson and Schmidt, commenting only that ‘these two agents are not mentioned in most accounts of the German espionage service’. The author betrays some confusion, however, by maintaining only one entry for ‘Schmidt, Hans/Wulf’, identifying him as TATE, but pointing to two separate passages in his book.

The farrago can probably be explained by the fact that several episodes in the Björnson/Schmidt saga are almost identical copies of events in the Caroli/Schmidt adventure. Both teams travelled from Hamburg to Brussels via Paris, and were delayed by the weather. Both Björnson and Caroli had a dalliance with a servant girl along the way. Björnson was incapacitated in his fall – as was Caroli, whose wireless equipment knocked him out. Hans Schmidt made his way to a nearby town, as did Wulf Schmidt. Both Schmidts arranged for SNOW to meet them, but with Wulf, it was High Wycombe, not Salisbury. (Landing in Wiltshire had been the original goal of the Caroli/Schmidt airdrop, as Nicholas Mosley reported.) SNOW arranged for a sympathetic doctor to treat both Caroli and Björnson. Caroli was arrested, as was Björnson. Both Schmidts were able to roam – apparently freely – for the remainder of the war, but they both had a clandestine meeting in London with a Japanese diplomat who provided them with more funds. The details of Hans Schmidt’s employment at a farm, and of his marriage, match Wulf’s exactly – except that Wulf had been under the control of the XX Committee.

[Note: The writer Nigel West asserts that the anecdotes about broken ankles, doctors, SNOW’s visit, etc. were invented by MI5 as a smokescreen to explain Caroli’s time of interrogation at Latchmere House.]

How this happened is easier to understand when the circumstances of the authorship are considered. ‘Charles Wighton’ never existed: it was the pen-name of one Jacques Weil, a former Swiss resistance fighter in France whose organisation was subsumed by SOE (Special Operations Executive). Under the same name, he wrote a disguised memoir of himself, titled Pin-Stripe Saboteur, in which he concealed his identity as ‘Simon’ while recounting his adventures in espionage in occupied France. (Nigel West criticises the book for suggesting that the PROSPER network in France was sacrificed for a ‘Machiavellian scheme’ to mislead the enemy about a second front, but does not indicate he knows who Wighton really was.) Gunter Peis was an Austrian journalist, who had met Lahousen after the war. Lahousen was indeed a real figure, who had very significantly provided important evidence against Goering, Ribbentrop and others at the Nuremberg Trials. He had fortuitously escaped punishment for the Stauffenberg plot on Hitler because he had been moved to the Russian Front in 1943, and been severely injured. He did indeed maintain a war diary, which was not available at the time, but, since it is now inspectable on-line, the reader can verify that its entries discuss activities at a very high level. Lahousen had far too wide an area of responsibility, in charge of sabotage (not espionage) across the whole of Europe, to know the details of operatives trained and sent out by the Hamburg Abwehrstelle.

Wighton and Peis quoted some entries from the Diaries in their story, but they can now be proved to have been faked. What seems clear is that the authors must have used the existence of the Lahousen Diaries as an alibi for a largely reliable source within British Intelligence to tell a surprising story about German espionage in Britain. The source – and Wighton/Weil admits to having a high-level friend in British Intelligence towards the end of Pin-Stripe Saboteur – must have been close enough to the action (or to classified documents) to have been able to relate a sizable amount of information that was true, but which became garbled in the transfer to the author. And if that source knew about the Double-Cross System, he or she withheld that aspect of the story because of the strict embargo that had been placed on all those involved under the Official Secrets Act. (In 1976, Peis repeated some of those initial errors in his book about TATE, The Mirrors of Deception, but he still did not have access to the unreleased files at that time.) Two major conclusions can be drawn from this exercise: i) the RSS was indeed not fooled or evaded by what turned out to be an imaginary duo of Nazi agents; and ii) unreliable sources can easily be elevated to a level of authenticity that they do not deserve once they appear alongside authoritative academic references. (See OfficiallyUnreliable for more on this topic.) O’Connor’s book should be withdrawn.

The Strange Suicide of Ter Braak

The case of J. Willem ter Braak is much more alarming, however. The archival documents on ter Braak (actually classified under his real name, Fukken) would have us believe that the Dutchman parachuted into Britain successfully, was not detected, and was thus not turned, but eventually committed suicide after some months of semi-successful espionage and wireless transmission, followed by a period of rapidly increasing desperation, as his money ran out. As will be shown, this is a highly controversial story, as, if true, it would point to massive failures in security and detection at a time when Britain was supposed to be on highest alert. Yet, if it is not true, what alternative explanation could there be?

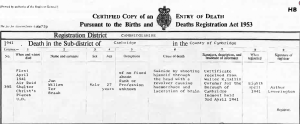

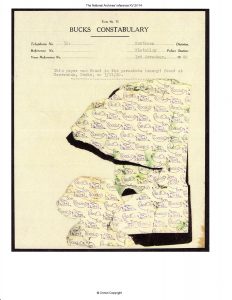

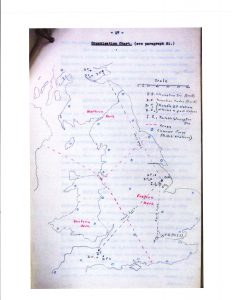

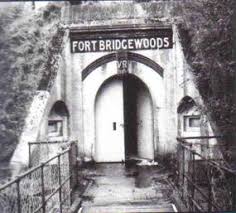

On November 3, 1940, a German parachute was found in a field near Haversham, in Buckinghamshire, but the owner was not found, and the search was apparently abandoned after a few weeks. On April 1, 1941, the body of an illegal alien was found in an air-raid shelter in Cambridge, an apparent suicide. The narrative proposed by a superficial examination of the documents in his Kew file runs as follows: MI5 was swiftly able to match the corpse with the person who had landed five months before, and, with the aid of articles found on the agent’s body, and items (including his transceiver) found in a compartment at the Left Luggage Office at Cambridge Railway Station, was able to construct the life that ter Braak had led in the interim. Having evaded capture, he had made his way to Cambridge, acquired a rental accommodation, as well as a bare office premises, and probably broadcast to his controllers in Hamburg until his batteries ran low. He had experienced problems with his food ration cards, but local officialdom had been careless. While pretending to have to leave Cambridge, he had in fact found other rental accommodation in the city, from where he made several excursions to London and to surrounding areas. Having not heard from his Abwehr bosses (possibly because he was not able to get his receiver to work), he was running short of money, and may have asked for help by communicating via traditional mail, using invisible ink and a poste restante address. Having wrapped himself up against the cold, in order to watch for help to be parachuted in that never arrived, he felt abandoned, and shot himself in despair.

What is extraordinary is how the official line has been accepted, even after the release of the files on ter Braak from Kew. For example, the German historian Monika Siedentopf, in her 2014 work, Unternehmen Seelöwe (Operation Sealion), offers one paragraph on ter Braak, merely echoing the conclusion of the authorised historian, Professor Hinsley. She does not appear to have read KV 2/114, the Ter Braak archive, however, as she provides no reference to it in her long list of TNA sources. It is quite extraordinary, given the length of time that this fugitive remained at large, how little attention has been given to him. (The records were declassified nineteen years ago.) Yet several aspects of the case merit very close inspection, namely: 1) MI5’s expectation that a parachutist would arrive; 2) ter Braak’s ability to escape initial attempts to capture him, and remain at large for several months; 3) the deductions made by MI5 concerning his wireless activity; 4) his struggles with his ration-book; 5) the evidence of ter Braak’s movements, and possible involvement in espionage and sabotage; 6) the reaction of MI5 when ter Braak’s body was found, and the subsequent cover-up; and 7) the highly controversial aspects of the victim’s ‘suicide’. I shall now explore each in depth.

Surprise?

In view of the heightened fears about invasion at the time, the recent well-publicised scare about a Fifth Column, the scars from the Battle of Britain, as well as the successful detention of several spies arriving by air and by sea, one might expect the authorities to have been better organised to handle the arrival of further enemy parachutists. Despite the Battle of Britain notionally having been won by then, Guy Liddell, head of B Branch, responsible for counter-espionage, himself wrote on November 15 of ‘one of the worst bombing raids . . . since the beginning of the war’. The procedures for communicating and following-up on such incidents of infiltration were, moreover, well documented. And yet, when the Haversham parachute was found, the local constabulary ‘forgot’ to inform the Regional Security Liaison Officer responsible. The outcome was that ter Braak managed to escape to Cambridge, about forty miles away, by November 4, and found lodgings there. One might have expected an intense manhunt to have been ordered, but the authorities remained calm. In an almost comical twist, on November 26, three weeks later, Worlledge of RSS suggested to Frost of MI5 that bloodhounds should perhaps be used to help track down the fugitive: two days later, Frost earnestly replies that they were in fact tried, without success.

Complementary to this strange behaviour are the very revealing observations made by MI5 officers. The day that ter Braak’s parachute was found (November 3) Liddell rather drily recorded the details, which merit citation in full: “An enemy parachute landing was reported today. A complete parachute with harness overalls and flying helmet was found neatly folded and placed in a hedge beside a bridle path on Hill Far [sic], Haversham, Bucks. The parachute was wet but the clothing inside dry, and it appears that it may have been dropped during the past two or three days. Inside the parachute was a paper wrapping for chocolate made in Belgium, and a packet containing a white tablet, probably concentrated food. The packet had recently been opened and contents consumed. The parachute had without doubt been used, and the parachutist landed uninjured and is still at large. There is no trace of a crashed aircraft and the parachute was undoubtedly deliberately dropped.” (This entry does not appear in the published extracts of Liddell’s Diaries edited by Nigel West, it should be noted.)

Liddell did not record, however, how he received this news, or how he was able to conclude that the spy had not suffered any contusions in his touching the ground. The message probably came directly from T. A. (‘Tar’) Robertson, then working for Major Frost of W Branch (sometimes called Section W, which had recently been subsumed into B Division), whom the local constabulary had contacted, via the Special Branch. Readers should bear in mind that, as Masterman’s account makes clear (p 100), while the authorised history of MI5 assuredly does not, that the famed B.1a section responsible for managing double-agents, led by Robertson, was not created until June 1941, long after the last LENA agent had landed. (After a showdown with Frost, when Robertson had complained to Liddell that he could no longer work with him, Liddell made the decision on December 12 to transplant Robertson ‘and all his minions’ out of W Branch into an established unit of B Division.) Yet Liddell never questioned why the relevant RSLO (one of the Regional Security Liaison Officers, namely B Division representatives dispersed around Britain, and first in line to investigate possible spy threats) was not informed, or why the message had not arrived through the proper channels. And he never referred to the case again in his diaries until ter Braak’s body was found, an extraordinary example of ‘the dog not barking in the night-time’. Why would it not be of supreme importance to him, and for his chronicle, to record how the hunt for the fugitive progressed?

It is also noteworthy that the proceedings of meetings of the RSLOs and the Security Executive (the supervisory body installed by Churchill to manage domestic intelligence) in the period October 1940 to April 1941 focus almost exclusively on what the procedures should be for processing captured agents, not on how resources should be deployed to tracking down undetected agents whose traces of arrival have been found. It is very telling that, at a meeting a few weeks before ter Braak’s body was found, the RSLOs engineered a change in the communications procedures, which now required that the Police Constables first inform them, who would in turn let W Branch know of a suspected agent. What is also intriguing is that the notes supplied for White’s address at the meeting (on February 18) specifically refer to ‘the Haversham parachutist’, indicating that he was still at large, but nowhere does this highly provocative state of affairs appear to engage the attention of the participants.

What should have been fresh in the minds of the RSLOs, however, was the case of SUMMER (Gösta Caroli), a supposedly turned agent who had tried, on January 13, to kill his guard and flee the country, being arrested at Ely, not far from Cambridge. (I have not yet discovered any record of what they were told of the affair.) Masterman later hinted that the RSLOs must have been in the know, since he wrote that SUMMER was apprehended ‘after some anxious hours in which we had been compelled to warn the appropriate authorities over half England to set a watch for the fugitive’ – a pattern of behaviour in marked contrast to the lethargy over ter Braak. Masterman went on to write: “His escape, had it succeeded, would indeed have wrecked all our schemes, but as things were no harm was done – not even to the strangled guard, who was the richer for a stimulating experience (and a good story) at the expense of some small temporary inconvenience.” Masterman’s levity was misplaced: if the guard had indeed talked carelessly about the event, the outcome might have been just as calamitous. I shall return to SUMMER’s fate later.

A full chapter – a thesis, even – could be written on this aspect of British security measures at the time. One of the most unprofessional, almost scandalous, aspects of the affair is that the role of Malcolm Frost and W Branch has been completely excised from the authorised history, as if Robertson always worked for the not yet created B1a. Neither Malcom Frost nor W Branch (nor even the RSLO organisation) appears in the index of Sir Christopher Andrew’s authorised history of MI5, Defending the Realm. Yet, at a time (November 1940) when Frost was being scorned by such as Swinton for his ego and his ambition, and he was apparently driving Robertson to distraction, the Director of Military Intelligence, Beaumont-Nesbitt, was writing to Frost, almost as an equal, to suggest that the military authorities should be given the responsibility for handling suspected spies after their arrest. It was a very puzzling relationship.

The focus returns to Liddell, since his Diaries are such a central source of the story. In the middle of November, instead of instantly organising pursuit of the dangerous quarry, he started plans for the formation of the famous XX Committee, and then had to deal with the sacking of Jane Archer, which in his journals he ascribed to her extended derisory comments about the MI5 head-in-waiting, Jasper Harker. (In April 1940, Jane Archer had been taken out of her vital role as lead in Soviet counter-espionage to design the RSLO group, and then manage the team of RSLOs.) Yet the timetable offered by the ter Braak archive lays open a completely new interpretation. Had Jane Archer perhaps challenged Liddell’s methods of undermining her authority through Section W’s continued bypassing of the RSLOs, who seem to have respected her skills very highly? Archer knew that Liddell could not be held totally responsible for the dysfunction in MI5, as an ungainly organisation had been forced upon the service by Swinton. In August 1940, however, Frost’s W Branch had been moved under Liddell’s ‘B’ organisation, and tensions between Frost’s group and the rest of ‘B’ were slow to be resolved.

The presumed cause for Archer’s sacking comes solely from Liddell himself, but in his Diary (in a passage also not published by Nigel West) he refers to a contentious conference on October 31 between himself, Archer and Frost. It would not be surprising if the highly capable Archer, perhaps still smarting about her removal from Communist work, had in fact challenged Liddell quite robustly over the way the whole RSLO infrastructure was being undermined, and over Liddell’s inability to control Frost, and that she thus forced a rupture. The timing of this meeting occurs just before ter Braak’s arrival: if Liddell was expecting him, as he admitted, could it be that he and Archer disagreed about a level of secrecy required in dealing with the Abwehr spy, that would have entailed excluding the RSLOs? I have found no documentary evidence of this, but it seems highly possible that he could not convince her otherwise, leading to a dissension that brought on her forced resignation. Liddell may then have made recourse to an external enduring motif to explain her dismissal. In addition, Frost was certainly a problem: on December 6, Robertson declared he could no longer work for him, and Liddell, who had been so enthusiastic about his ‘man from the B.B.C.’ a few months before, must have been having second thoughts.

Thus, after the heated events of the winter, and the arrival of David Petrie (who, after a few weeks of intense analysis, was officially appointed as the new Director-General in mid-February 1941) to shake things up, it is with some degree of astonishment that the ter Braak case suddenly reappears in Liddell’s Diary. We read in his entry for April 1, 1941, that he has, the same day the body was found, already been informed of the discovery, and of the verdict of suicide (before any inquest, one should note). The local police force had very speedily undertaken their investigations, being able to inform Liddell that ‘he had lived in Cambridge for about four months’ (an incorrect calculation, as it happens), having arrived with a small suitcase and parcel. Liddell concluded his entry as follows: “On form I should say he was undoubtedly a parachutist, and probably one whom we expected at that time.” (In a more public forum, however, he was much more guarded: at a meeting with the RSLOs in Oxford a few days later, he merely commented that the person discovered was ‘probably’ the parachutist from November.)

So why would Liddell not have pointed out that fact – that ter Braak had been expected – when the parachute was found? And why might MI5 have expected his arrival? Ter Braak was, according to most accounts, not in fact linked with the Operation LENA spies (e.g. Caroli and Wulf Schmidt), so the story has been encouraged that MI5 would not have learned about his role from Caroli (SUMMER) or Wulf Schmidt (TATE). After the war, in June 1946, when MI5 interrogated Abwehr officials, and showed them ter Braak’s photograph, neither Nikolaus Ritter (head of Abwehr I in Hamburg), nor Jules Boeckel (who replaced Ritter in March 1941) could identify who he was. Ritter, who denied that ter Braak was a LENA agent perhaps a bit too assertively, said his wireless apparatus was not designed for summer use (unlike the LENA agents), and Boeckel suggested that he might have been managed by Brussels, which would make excellent sense, given the origin of the chocolate wrapping that Liddell had referred to. (Though one has to question such an obvious clue: why would an ostentatious wrapper be packed into the parachute, and were parachutes not supposed to be buried or burned on arrival, rather than being ‘neatly folded’?) Thus two scenarios present themselves: 1) The RSS had picked up Abwehr messages, with the resulting decrypts pointing to an imminent drop by the Brussels station. (I have not yet been able to inspect the detailed source records at Kew. And we recall Liddell’s comments about KUHIRT and SCHROEDER.) 2) Ter Braak was indeed a LENA agent, and Liddell had been warned of his arrival by TATE, but for some reason all the Abwehr officers after the war wanted to disown any connection with him. That would not be surprising if the Churchill assassination plot (see below) were indeed true. Abwehr officers, in any case, gained a well-deserved reputation for not speaking, under interrogation, openly and directly about their wartime experiences.

Finally, we have the evidence of Robertson. On November 15, this gallant officer had had to apologise to Michael Ryde, the RSLO in Reading, stating that the blame for the failure in communications lay with the Chief Constable of Buckinghamshire, who should have reported the matter to the RSLO rather than alerting adjacent police forces. The same day, Robertson wrote to Ronald Haylor, the RSLO for the adjacent region of Nottingham, to make a similar apology, explaining that he did not hear about the parachutist until November 3 (i.e. the same day that Liddell learned of it), but enigmatically added that he did not recommend ‘using the parachutist for our own purposes, so I think it would be advisable to lay on as wide a hunt as is possible’. Is this not an extraordinary careless way of representing MI5’s intentions, and expressing the necessity of speeding up isolation of the spy? First of all, Robertson obliquely admitted that MI5 had ulterior purposes in considering the exploitation of parachutists (for the emerging Double-Cross System), and implicitly that the RSLOs knew of this project, but at the same time indicated that efforts to track down spies could be restrained – and no doubt were being held back – in the cause of presumed monitoring of their activities. He very significantly echoed this policy when, after Jakobs had parachuted in on January 31, 1941, Liddell noted in his Diary that Robertson wanted to give him [Jakobs] a run ‘in order that we may find out exactly how much these people can ascertain if they are left to themselves’.

Yet it was a very risky and slapdash judgment to make about the potential of a double agent when MI5 had not even identified or interrogated the suspect, and did not know how dedicated a Nazi he was. As soon as every agent was captured, he or she should have been sent to Camp 020 at Latchmere House in Ham, for interrogation by Colonel R. W. G. Stevens, but such a consideration appeared far from the minds of Liddell and Robertson in this instance. On November 18, Robertson wrote two more significant letters. The first was to Colonel Wethered, the RSLO for Birmingham, following up on a telephone call with him the previous day. It is clear from this long letter that Wethered knew nothing about the parachutist before then. The RSLOs had not been informed. The same day, Robertson had an important insight, showing all the wiliness of the veteran officer’s knowledge about fugitives, and wrote to Worlledge of RSS in the following terms: “This brings one to the conclusion that the parachutist, if he is at large, must have gone to some hiding-place.” Indeed, for that is what fugitives do the world over – unless they are allowed to survive in broad daylight. Suddenly, a pattern for ter Braak’s bewildering ability to stay on the run emerges.

Ter Braak’s Wireless

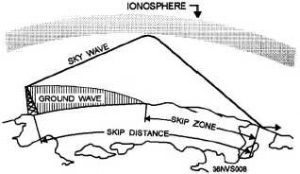

What is critical to this story is the use of wireless: ter Braak had a working set, and RSS was supposed to be supremely well-equipped to deal with incidences of illicit transmissions from within the nation’s borders (see earlier Chapters 1 and 2 in this saga). Thus an inspection of what RSS and related units did or did not do, and how MI5 responded to their actions, is highly important. The analysis by MI5 officers of ter Braak’s wireless activity can be seen to take place in three stages. There is an initial assessment necessary to provide the political cover for informing the government of what happened, completed by May 1941. That is followed by a deeper internal review later that year. The last stage occurs after the war, when Abwehr officers have been interrogated about the case.

After the wireless apparatus had been discovered in the left luggage office on the day after the corpse was found, Herbert Hart (B2.b, the Oxford academic, who the following October was to marry Jenifer Fischer-Williams, the Soviet spy and probable betrayer of Walter Krivitsky to Guy Burgess), on April 11 sent it to the SIS for examination. Marriott (B2.a) recorded on May 6 that he had received the report from SIS, which had, strangely, been ‘missing’ for a while. The report included the statement that the apparatus was ‘identical in design to one taken from enemy agents off coast of Scotland, though not so complete.’ It added: ‘The separate H.T. and L.T. battery completely run down [sic], while H.T. batteries in suitcase show 195 volts instead of normal 270.’ The conclusion was that the set had been used considerably

Hart’s official May 7 report to Dick White, head of B.1, responsible for ‘Espionage’, offers a different conclusion, however: “Ter BRAAK’s wireless transmitting set has been examined and the expert opinion is that it had probably been used in the effort to establish contact, but it is impossible to say whether the effort was successful or not.” This last observation was an embellishment by Hart, as SIS ventured no opinion on that unverifiable truth. Moreover, that was not the only opinion Hart inserted. He also described the set as follows, saying that the search at Cambridge Railway Station revealed ‘a brown Moroccan leather case containing a W/T set similar in all respects to sets brought to this country by enemy agents who had been dropped by parachute and captured’. This statement is false in many respects. There had been only four admitted enemy agents who had been dropped by parachute – TATE, SUMMER, GIRAFFE (Graf) and GANDER (Geysen). The last three brought with them a device that contained a transmitter only. The SIS report referred to the three agents who had been arrested in Scotland on September 30, Drucke, Walti, and Eriksen, but they had not arrived by parachute. And there is a combination of naivety and excessive detail in Hart’s report as well. He offers a conclusion that ‘there are strong grounds for thinking that Ter BRAAK was, in fact, the parachutist whose parachute was discovered on 3.11.40 at 12.00 hrs at Hill Farm, Haversham, Bucks.’, when, as has been shown above, Liddell had come firmly to that conclusion the day that ter Braak’s body was found. Hart also provides some details about ter Braak’s ‘self-inflicted wound’ that should perhaps have been kept under wraps.

A reason that this report might have been considered unsuitable for wider dissemination is that, while White’s forwarding of it appears in the ter Braak files at TNA (KV 2/114), Hart’s report is absent. It can, however, be found in a folder concerned with ‘immobilisation and arrest of enemy agents’ (KV 4/406). Thus Hart’s misrepresentations might have been deemed unsuitable for inclusion, as they both contradicted facts elsewhere, and told too much: his memorandum somehow managed to escape to another file. Were Liddell and White withholding information from Hart, and letting him blunder on in the dark? That would be highly unlikely, given Hart’s deep involvement in the case, and the sensitivity of his mission. It seems much more probable that he was guided to write a report that emphasized the similarity between ter Braak’s case and those of other agents, and that for some reason MI5 wanted ter Braak’s possible wireless activity to be minimized. After all, it would not help much if the report – to be sent to all the RSLOs – indicated that RSS had not been succeeded in performing its job properly.

MI5 picked up the investigation again in the autumn. Hart had provided some details about ter Braak’s movements with suitcases, gathered from his landladies, that indicated that the agent had concealed the wireless set from both of them. By this time MI5 officers have started to theorise more profoundly. Now under the new leadership of Petrie, a fresh organisation is in place: head of B1.a is ‘Robertson, ‘Special Agents’, and Hart is now alongside him as B1.b ‘Espionage Special Sources’. (Dick White is now head of B.1, while Frost now reports to Liddell as head of B.3, responsible overall for ‘Communications’, which includes B.3A, ‘Censorship and Reception Analysis’, B.3B, ‘Illicit Wireless Investigation and Liaison with RSS’, and B.3C, ‘Lights and Pigeons’.) On September 10, Gwyer in B1.a issued a long report. It informs us that, during both his periods of lodging, from early November to late March, ter Braak never left his accommodation overnight. He had rented an office above the agents who had found his rental properties, but apparently visited it only two or three times, and was never seen taking a suitcase with him when he left in the mornings. Gwyer’s conclusion was that he could not accept the view (apparently promoted by Fl. Lieutenant Cholmondeley of B.2a, the officer who later cooked up the Operation Mincemeat scheme with Ewen Montagu) that ter Braak failed to communicate by wireless, pointing out that he had one aerial suitable for night-time transmission. (And the SIS report indicated that he was given two crystals, and thus had two frequencies to use, the lower one being necessary for night-time use.) “We know that he was only equipped with one aerial which was suitable for the frequency he was instructed to use at night, but we also know . . . that the only time that he was alone with his wireless set, apparently, was at night. He could not have transmitted during the day, as he could not have left lodgings with a wireless set in a suitcase without somebody noticing this fact. Equally, he could not have used his office for transmissions if he was there so infrequently.”

Gwyer owned up to a high degree of precision in his estimates. He stated that ter Braak’s batteries, ‘exhausted at time of his death’ would not have lasted more than two months, although how he came to that conclusion without knowing how frequently, or for how long, the apparatus had been used is not explained. Ter Braak was able to replace his low tension battery, but not the high tension one, and thus had to purchase an accumulator. His conclusion was that ter Braak had probably transmitted successfully up until about Christmas 1940, after which he communicated in secret ink, using a poste restante address. Gwyer assumed that he had asked for a new battery through this medium, and was expecting delivery from a new agent. When none appeared, he killed himself. Gwyer’s colleague, R. T. Reed, added that ‘contacts during the day would have been impossible, because of aerial provided and difficult to avoid suspicion or capture if seen’, but expert judgment (in the person of Dr. Brian Austin) has informed me that adapting an aerial for the night-time frequency should have been a straightforward task. In Dr. Austin’s words: “Ter Braak’s single piece of aerial wire, of some unknown length, could have been made to work at maximum efficiency on both the frequencies allocated to him.”

Perhaps ter Braak had not been properly trained for such adaptations. In his interrogation after the war, Lahousen (the officer who headed Sabotage and Subversion) criticised the Abwehr’s radio ‘expert’, Rasehorn, for being ‘not very well qualified’, asserting that ‘his wireless connexions did not work’. Thus there could have been deficiencies in understanding in both Abwehr and MI5 camps. Indeed Reed’s expertise must also be questioned. On July 24, he had written a report on wireless telegraphy which stated: “I tested the set of ter BRAAK in communication with Radlett. The aerial that he was given is satisfactory on 4508 kcs, but will not work effectively on 5435 kcs., which is his day frequency. According to the file of Ter BRAAK, it would seem that he never tried to get into communication during the night time and only tried during the day time.” Did Reed adjust the aerial? It is not clear. Yet how did anyone know about ter Braak’s failure, since other testimony points to the fact that ter Braak did not even take his set out during the day? The evidence provided elsewhere is that ter Braak could have communicated only in the night-time.

It is only at this stage that the RSS appears to become seriously involved, which is quite astonishing. Back in November 1940, RSS was certainly deploying its interception capabilities. A report from W.2 (Robertson, working for Frost, whose main interest at that time was investigating ground communications with aircraft) on November 5 declares that the unit was hunting the spy, with promising indications. “From the intercepts produced by R.S.S., it seems likely that there is at least one wireless set being operated in the country. Every effort is of course [sic] being made to locate this.” Dr. Austin has estimated that, at the frequencies used by ter Braak, a successful Direction-Finding station would have had to be as close as 6 miles away for his ground wave to be picked up – a calculation that might suggest that Lt.-Col. Simpson’s planned dispersions (see Chapter 2) were not dense enough. The nearest station appears to have been one at Steeple Bumstead, about twenty miles south of Cambridge, but, with a known enemy agent on the loose in the area, one might perhaps expect a more flexible campaign to have been undertaken to track down the suspect.

The same day (November 5), Robertson reports that all the intercepts appearing in RSS’s weekly report have been identified. And a week later, Hinchley-Cooke in B.13 receives a report from Robertson that ‘so far neither the Bucks Police nor R.S.S. have been able to find any trace of the man.’ One could reflect that the parachutist might not have considered helping the authorities by remaining in the small county of Buckinghamshire, but the current record then goes quiet. Did MI5 not really care what happened after that? So, much later, during this post mortem, when Robertson asks Hughes of B3.b (the liaison between MI5 and RSS), on September 11, 1941, to enquire of RSS ‘whether any station heard on 4508 kcs or possibly 5435, in period November 4 1940 to January 31 1941, between 2100 and 0900 GMT using a 3 letter call of the type others used having a circular code, i.e. LNP, GIK, etc’, one’s first reaction is, even if the exact frequencies and callsigns were not known then, why would such an intense action have not been performed at the time of the hunt? And why would Robertson and Hughes not ask whether any traffic had been intercepted from Hamburg during the time of ter Braak’s fugitive status?

The description of the exchange that followed deserves quoting in full. Thus Hughes to Robertson on September 14, 1941: “With regard to your note of the 11th Sept. concerning the possible workings in connection with the Cambridge ‘suicide’ case, the Controller, R.S.S. replies that they are doing what they can with extracted records, but that the original traffic of that period has been destroyed. It is not possible for RSS to keep all original logs for any great length of time as the volume would be entirely unmanageable, so I am afraid there are not likely to be any useful results of this inquiry. Is there any other line of attack you would like me to suggest to RSS? RSS are hoping to be able to make records of any QZZ traffic which they pick up during this week. Only part of the text is likely to be recorded, but I think this will be satisfactory for your purpose.” And two days later, Reed writes: “I spoke with Major Morton Evans yesterday and asked if it were possible to keep a careful radio check on the East-Anglia area. We decided that this was technically impracticable. The only line to take was that if any station was suspected of working in the East Anglia area – by the results of the direction finding stations – special attention should be paid to it. Should any such station be intercepted, Major Morton-Evans will see that this is done.”

Group of ex-RSS members and supporters, Bletchley Park, 2013

Bob King is seated, far right. Stanley Ames and Dr. Brian Austin, standing, far left.

Over the years, this puzzling interchange has tested many members of RSS. At one of the assemblies of ex-RSS interceptors and officers, at which enthusiasts also take part, in 2015, with ter Braak’s records then open at last, a group discussed how RSS could have avoided picking up his signals. After all, they should have had enough density of voluntary interceptors to simply pick up the groundwaves. Bob King, who had been working at Arkley, the location to which all logs were sent, at the time, offered the following possible reasons (which I reproduce here in their original form):

- He did not transmit.

- If he did his procedure was not suspicious.

- His calls were very short and with a non-resonant aerial very weak.

- No one was listening at the right time on the right frequency. (Not so likely).

- He was heard and his logs arrived at Arkley but not fitting any group was marked in the books as ‘Suspect’ and awaiting further reports.

- He was reported to Arkley, and log readers were told to ignore [signals] believing it to be an agent already covered.

What Bob King overlooked in this analysis was the detection of signals from ter Braak’s controllers in Hamburg. According to the confident doctrine of Walter Gill, whose report was written just after ter Braak arrived, the absence of agents in the UK could be determined by the fact that no incoming transmissions were intercepted by the RSS’s major stations. Yet, if ter Braak had a receiver, messages would surely have been sent to him – at least in the first few weeks. Thus, one must conclude that RSS picked up those signals (even if ter Braak was unable to), but that MI5 chose not to act on that discovery. In light of the fact that MI5’s leaders admitted that an unidentified German agent had parachuted in with a wireless apparatus of some kind, Gill’s policy appears at best bizarre, and at worst, simply irresponsible.

Interrogations with Abwehr officers after the war did not disclose much else, although now new officers in B1.a were still asking the same questions. Joan Paine of B1.a in September 1946 still acts as if she does not know whether ter Braak and the Buckinghamshire parachutist are the same person, which makes it appear as if she had been deliberately kept in the dark. Her colleague Warrec expresses the same uncertainty. But the Abwehr officers either do not know any more, or pretend they do not. Karl Krazer, of the Hamburg unit, asserted that the last LENA mission took place in September 1940, and thus ter Braak could not have been part of it. Moreover, he echoes Ritter’s claim that LENA agents all had ‘summer-time’ transmitters, unlike ter Braak, thus providing an opinion contrary to what Hart had said. Both Krazer and Richter recommended speaking to Sensburg of Brussels. The file on Sensburg is dominated by his time as head of the Athens Abwehrstelle, whither he was transferred from Brussels in May 1941. He was surely still in charge when ter Braak’s crisis occurred.

The documents also confirm that a Brussels-based agent named Fackenheim was close to being parachuted into Britain, but was confounded by the weather. Yet Fackenheim was returned to Germany in the autumn of 1940, so he could not have been around in April 1941. Sensburg also gave final instructions to Waldberg, Kieboom, Pons and Meier, who were sent to the Kent Coast by trawler early in September, all of whom except Pons being subsequently executed, so his role in handling ter Braak sounds very probable, even though Sensburg does not list ter Braak as a member of the LENA operation. (Interestingly, Jakobs and Richter, both of whom were sent out later than ter Braak, are listed as LENA agents by Sensburg, thus contradicting Krazer. Again, these Abwehr officers may not have been entirely honest.) But the opportunity to interrogate Sensburg on that matter seems to have been missed. A few extracts from ULTRA intercepts describe some of his actions, but nothing concerning spies sent to Britain. Perhaps senior MI5 officers were hoping the whole issue would die a gradual death.

Ter Braak’s Mission and Movements

So what was ter Braak doing in Cambridge? It might seem an unlikely city to conduct espionage, although several military airfields were in reasonably close reach. One theory, promoted by Winston G. Ramsey in After the Battle, suggests that the spy was sent, by SS General Walter Schreckenbach, on a special mission to assassinate Churchill, and it describes how ter Braak was trailed, his lodgings searched while he was out, and found to contain ‘a wireless transmitter, detonators, a Luger pistol, a file on Mr. Churchill’s movements and three crudely forged Dutch passports’. The writer provides no source for this fantasy, which sounds like a crudely conceived smokescreen. (The assassination plot is echoed by Charles Whiting, in his 2000 book Hitler’s Secret War, though whether he used Ramsey as a source, or shared Ramsey’s informant, is not clear. Whiting is of the school that considers that ter Braak was indeed one of Ritter’s LENA agents, while he repeats Ramsey’s more credible account of how ter Braak’s body was found. He does not list Nikolaus Ritter in his Acknowledgments, but it is evident from his text that Ritter became a friend after the war, and was a major source of his information, thus undermining Ritter’s testimony to his interrogators.) It would have been highly unlikely for the SS to select an Abwehr operative for such a scheme; it would not be good practice to try to mix sabotage/destruction with espionage (although it did sometimes happen), as sabotage is noisy, and gains attention, while espionage is quiet and clandestine. An assassin would not need a wireless, just a rapid means of escape. The pistol found by ter Braak’s body was a Browning, not a Luger. And why ter Braak would languish in Cambridge for five months if charged with such a mission cannot be answered.

Another explanation, which surfaced when a flurry of memories was published in the Cambridge Evening News in January and February 1975, following the After the Battle investigations, was that ter Braak had come to blackmail prominent émigré academics living in England into cooperating with the enemy, presumably by threatening their relatives. “One person on ter Braak’s list”, the account read, “was professor of Law at Clare College, Kurt Lipstein, who had left relatives behind in Germany when he came to England in 1936”. But the leads appear not to have been followed up. A perhaps more convincing explanation was that ter Braak was guiding German aircraft to military targets in the area, and that that ‘Army Intelligence knew that signals were being given during raids and troop movements in the Cherry Hinton area’ (which was part of Cambridge). A major example provided was a raid by Dornier 17s as tanks were being unloaded in the Cambridge marshalling yard, with eleven fatalities as a result. Yet the date given was February 24, 1941, when ter Braak’s radio was supposed to be no longer working. Can we rely on that? Or was he indeed still broadcasting at that time, and was that a fact that MI5 chose to conceal when it realised it might have had blood on its hands by allowing him to remain active? Did MI5 then attempt retrospectively to ‘silence’ ter Braak from December?

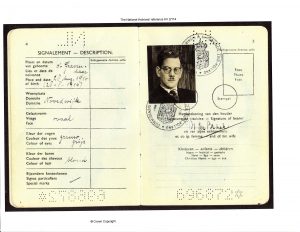

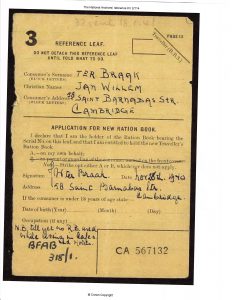

Yet Cambridge was indeed his objective. The false and very clumsy identity-card he was provided with in Brussels (see photograph) gives a non-existent address of ‘Oxford Street, Cambridge’. It has one person’s handwriting in places where that of an official and the owner should appear. The number of the residence was entered after the name of the street, in continental style. The Christian name appeared, wrongly, before the surname, and the card was machine-folded, not hand-folded. (These failures were provocatively used at RSLO training in February 1941.) Thus we have to face the facts that the spy apparently landed on October 31 or November 1 (since enemy aircraft were spotted both those nights, and the parachute was wet from rains since) and was able to extricate himself from his parachute, conceal it neatly, pick up his two suitcases, and somehow walk the forty miles from Milton Keynes without being spotted, or gain transport from some unsuspecting or abetting agency, not reaching Cambridge until November 4. The parachute was found at noon on November 3: this was at a time when the head of counter-intelligence at MI5 declared the service was expecting him, and a ‘thorough search of all woods, buildings’ was in process and that ‘enquiries are being made at all shops, cafes, hotels, railway stations, etc.’. One report, from November 12, says that the parachute was found near the house of a man who was under suspicion, but no more is said of this gentleman, or whether he was able to help ter Braak on his journey to Cambridge. Thus we have to conclude that Ter Braak either arrived in Cambridge with at least three days’ stubble on his chin, and a wet overcoat, having slept in the open, with a suitcase on either arm, yet failed to provoke any attention, or found shelter with some sympathizer. He then successfully installed himself with Mr. and Mrs. Sennitt of 58 St Barnabas Road, Cambridge, after gaining their address from a rental agency.

Ter Braak’s movements overall were erratic, and showed no focused pattern of activity. They were partly re-creatable because the spy rather enigmatically kept all his used bus-tickets, and thus his journeys around the countryside, and once to London, could be traced. But, since he never spent a night away from Cambridge until his final foray into the night, they are not really germane to the story. MI5 knew, from interrogations of other agents, that reporting on the success of bombing-raids was a major part of their mission, so it is likely that ter Braak was involved in such activity. What is far more intriguing is how he managed to deceive the authorities for so long. Most of the recorded saga refers to his travails with his ration-book, but the failure of everyone (rental agency, or landlord and landlady) to make even a cursory inspection of his identity card, is dumbfounding. What is noteworthy about the card, apart from its obvious forgery to the eye, was the fact that it contained a serial number that had been provided to the Abwehr by SNOW, thus showing that, even if the Hamburg Abwehrstelle did not know about ter Braak, Nikolaus Ritter was clearly passing on seemingly valid numbers to be shared by the Brussels Abwehrstelle. Evidence of such cooperation could of course reinforce the theory that ter Braak was indeed one of the LENA team. Only when the Food Office in Feltham looked up the ID card number supplied by ter Braak did it realise, very tardily, that the number was one issued to a Mr. Burton. When challenged on explaining this, ter Braak panicked and left his lodgings, saying he was leaving Cambridge, but in fact he only moved to a different accommodation in the city.

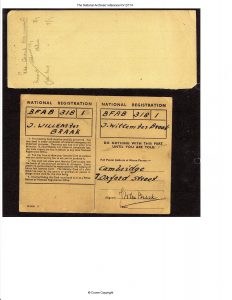

What occurred with ter Braak’s National Registration Card and ration-book would come back to haunt MI5. The card found on ter Braak’s body had the number BFAB 318-1 (see image). When ter Braak’s landlord, Mr. Sennitt, dutifully went to see the Assistant Aliens Officer of the Cambridge Borough Police after ter Braak’s arrival, in order to report the Dutchman’s presence, the officer told Sennitt to get hold of a copy book and get the Dutchman to write his name, and date of arrival in it. As Hart reported: ‘the Assistant Aliens Officer concluded his remarks to Mr. Sennitt by saying: “Don’t you worry, the fellow will be along shortly soon to report himself.”’ Hart added that ‘ter Braak, of course, did nothing of the sort and nothing further was done by the Assistant Aliens Officer’. That was quite an extraordinary oversight by the Officer, but why Sennitt – or even the rental agency, Haslop & Co. – had not thought to ask for the alien’s identity papers on first encountering him, is also worthy of comment. Were all regional towns, cities and their establishments not on high alert for detection of an alien parachutist? Experiences with other dubious-looking strangers, such as the three spies who landed in Scotland by boat (Drucke, Walti, and Eriksen – see above), show that inspection of ID cards was the first task to be undertaken.

That hurdle passed, ter Braak had to provide a ration-book to his landlady, so she could buy provisions for him. Yet the forged one he supplied was seen to have expired in July 1940. Here the narrative diverges. Hart’s memorandum indicates that that fact was ‘soon’ discovered by ter Braak, although the word ‘soon’ is enigmatically written in by hand, replacing the word ‘not’, a paradox, and maybe a subconscious error, that Hart did not attempt to explain. The hidden notion may be revealed in the report by the Cambridge Borough Police, dated April 24, 1941, where the officer wrote that Mr. Sennitt agreed to visit the Food Office in Cambridge to obtain an emergency ration card, while ter Braak wrote off for a new one. Again, why no one asked how ter Braak had managed to survive beforehand with an out-of-date ration book is a question unraised by all concerned. It should be recalled that November 1940 was the peak of the Blitz, when Hitler was trying to strangle Britain to death: nearly 7,000 civilians died from German bombing that month, and offences against the use of ration-books were publicly listed to deter abuse.

Here again, Hart distorted the truth. In his memorandum, he wrote that ter Braak applied on November 28, 1940 to the Food Office appropriate to the number on his Identity Card (i.e. Feltham Food Office) for a new book, ‘explaining away the fact that his book had become out of date and had not been used on the ground that he had been living in Cafes and Hotels’. Yet the only address on the Identity card was ‘Cambridge, 7 Oxford Street’, and MI5 officer Gwyer’s report of September 10, 1941 expressed puzzlement as to how ter Braak knew to write to an office in Feltham. “He himself never visited the Food Office, his emergency cards being drawn by his landlord. It is true that the Food Office may have told the landlord which was the correct office for ter Braak to apply to, but the Police Report of April 21st states ‘so far as Mrs. Sennitt (the landlady) is aware, Braak sent the old book to either Cambridge Street Road or Terrace, London’”. The issue is mysteriously left unresolved, though later in his report Gwyer refers to Mrs. Sennitt as ‘an incompetent witness’. Mrs Sennitt persisted in questioning ter Braak each week about the receipt of his new ration book, and each time, on receiving a negative answer, she would acquire another temporary one.

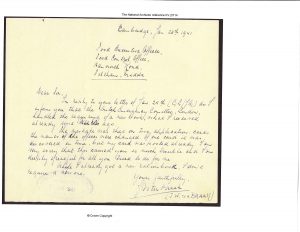

I reproduce ter Braak’s application here: the date is clear; a Food Officer has entered the wording of ter Braak’s explanation for survival without a book, and also entered his National Registration number, as we can confirm. The Ration Book number is printed – CA 567132. (Hart mistakenly listed it as CA 567123, which might explain some later confusion. The Cambridge Borough Police had by April 4, 1941 verified that that number had been issued by the Feltham Food Office to one William Widhers, a civil servant employed by the Prison Commissioners. This was the same number that had been provided on August 9, 1940, to MI5, in the name of Burton, and was passed on, nominally through SNOW, as a safe number for the Abwehr to use. MI5 then tried to contact Burton to clear up the duplication, but he was away, and the error had to be ascribed to ‘mistakes by the registration authorities’.) The timing after the receipt of ter Braak’s submission is not precise in Hart’s account: he wrote that, ‘on receipt of ter Braak’s application,’ Feltham Food Office looked up the number of the ID, found that it had been issued to a Mr. Burton, and thus sent the official form R.G. 32 to ter Braak, asking for full particulars. At some stage ter Braak must have sent in his R.G. 32, as a letter from Feltham, dated January 25, asks him to confirm that he no longer wants a new book, and that the previous request was a mistake. Ter Braak’s reply of January 28, 1941 can be seen in the accompanying image. Either the Feltham office had been very sluggish in sending out the original R.G.32, or it had been very lenient in not demanding the prompt return of the form. Again, no questions appear to have been raised about the efficiency of the process, or the lack of consultation between the Feltham and Cambridge Food Offices.

One can now understand why ter Braak probably relaxed up until the end of January. He had followed the protocols, submitted his application, continued to receive temporary ration books (though to the consternation and amazement of his landlady), and could carry on with whatever he was doing. Yet the lie he gives in his letter about the Dutch Emergency Committee, and its supplying him with a new ration book ‘a few weeks ago’ with the result that he no longer needs a new one, does betray some desperation. Moreover, the normal number of weekly emergency ration books that was allowed to be issued was six: the Food Office in Cambridge had been lax enough to extend it to twelve in ter Braak’s case. Eventually its patience ran out – on January 30, just before ter Braak’s letter was received in Feltham, The Cambridge Office informed Mrs Sennitt that ter Braak was required to pay a visit to the Food Officer.

At this stage, ter Braak panicked. “He appeared agitated’, said Mrs Sennitt later. He told his landlady that he had to go to London, and would have to quit his premises. Only then did Mrs Sennitt notice his second suitcase (containing his wireless set), which he put in the taxi taking him to the railway station. Yet, by a remarkable coincidence, Mr Sennitt, who suddenly realized that he had to follow him to regain the front-door key, could not find ter Braak when he explored all the carriages in the London train waiting to leave. And a few days later, Mrs Sennitt bumped into ter Braak on the street in Cambridge, at which he explained that he had had to return for a few days.

In fact, ter Braak, again using the rental agency, had arrived the same day he left the Sennitts, on January 31, with his two suitcases, at 11 Montague Road, the residence of Miss Rosina Greenwood, to begin a new rental. Part of the arrangement was that he did not require feeding (apart from toast and tea at breakfast), so Miss Greenwood had no need to ask her new lodger for a ration book. Yet the indolence of the authorities is perplexing. Why on earth would Mr and Mrs Sennitt, who had watched a lodger with dubious papers suddenly come under close examination from the Food Office, one who apparently never followed up with the Aliens Officer, and then observed him displaying erratic and mendacious behavior in suddenly quitting his lodgings and making spurious claims about going to London, yet not boarding the train, but taking a mysterious suitcase with him which they had not seen before, not think they should perhaps report such behaviour to the authorities? Had they perhaps been primed to stay silent about the whole business?

Yet ter Braak managed to stay undetected for another two months. He continued his perambulations; he made a visit to London; in mid-March he went to Peterborough for the day. He visited his office above the agents for the last time on February 12. Obviously it was important for him to stay in Cambridge, although one might judge that he could have been safer settling down in another city, with a different Food Office. Why did he think he could remain safe? He left the house each day, but, according to Miss Greenwood, never took either of his suitcases with him. And then, according to one report, a fortnight before he left for the last time, in mid-March, he told his landlady that he would be leaving in two weeks. Gwyer’s report, however, states that he left his lodgings on March 29, without settling the bill, but taking with him nearly all his luggage, and returning the key to his landlady. He told her he would be back on April 5. Incredibly, apart from an aside where he tells us that ter Braak asked, on March 20, a fellow lodger who was employed at Lloyd’s Bank to cash some dollar notes for him (an account that is incidentally undermined by the subsequent police report which states that ter Braak asked Mr Sennit, his first landlord, to exchange some dollars, which duly occurred at Lloyd’s Bank), Hart’s memorandum just devotes one sentence to ter Braak’s time at 11 Montague Road, and does not discuss the circumstances of his departure at all.

The ‘Suicide’

The investigation into ter Braak’s death was beset with contradiction and controversy immediately his body was found. It was perhaps a bit hasty of Liddell to record confidently in his diary on that day, before any official police report or inquest the following assertions: “He had evidently shot himself and had been dead some 36 hours. His Dutch papers were out of order and did not show any authority to land. He had lived in Cambridge for about four months [thus echoing the erroneous Police calculation]. He had arrived about 4th November with a small suitcase and parcel.” Such a conclusion would have required the Cambridge Police to have traced ter Braak’s residence through two rentals in the space of a few hours. Yet that unit did not deliver its report on finding the body until April 4, the day of the coroner’s inquest. Amazingly, that report declares that the first landlady’s address was determined only through ascertaining that the suit that ter Braak was wearing had been bought at the Fifty Shilling Tailors in Petty Cury, and the purchaser had given his name and address of 58 Barnabas Road, Cambridge. The report continues: “Detective-Inspector Ernest Bird went with Captain Hughes and Detective Sergeant Robinson to that address, and interviewed the occupier.” The officers then had to make ‘continued enquiries’ to trace the suitcases in the Left Luggage Office, as well as tracking down and interviewing ter Braak’s second landlady. This constituted an impressive piece of work by the Cambridge constabulary, in order to be prepared for the April 4 inquest.

Liddell appeared to be on top of the case, and have paranormal insight, as he recorded the following in his April 3 entry: “There is no doubt that he was the parachutist who was reported to have come down near Bletchley. We have obtained his wireless set which was in the cloak-room of Cambridge Railway station.” It appears he had been kept informed by Robertson, who in another memorandum written on April 2, indicates that Mr. Hughes, the Regional Officer at Cambridge, had spoken to him on the telephone the previous evening, informing him that the police had spoken to the first landlady (only). Hughes called again on that morning (April 2) to let Robertson know that they had found ter Braak’s possessions at the station. But at that time they had not yet interviewed Miss Greenwood: Liddell should not have been able to know for certain that ter Braak had resided in Cambridge ‘for about four months’ as he stated in his April 1 diary entry. He clearly anticipated the error from the April 4 report.

In any case, MI5 was preparing single-mindedly for a quick and clean inquest. As early as April 2, Brigadier-General Jasper Harker, Deputy Director-General, wrote a letter to the coroner W.R. Wallis, pointing out how delicate the case was, and how grateful he was to Wallis for consenting to take the case in camera. ‘We have in our possession information which satisfies us beyond any doubt that the deceased was an enemy agent’, he wrote, an extraordinarily premature claim if it had been based on materials found on ter Braak’s body, and definitely not yet in the possession of MI5. Harker continued: “You will appreciate that it is of paramount importance that no report of any kind should be published with reference to the proceedings before you”, adding that the Home Office had approved MI5’s request for secrecy. All went off very smoothly. Dixon was able to report to Dick White that ‘I am pleased to say that the Coroner’s inquest went off very successfully, Brigadier Harker’s letter helping in no small degree.” The target of Jane Archer’s lampoonery had come through.

Yet the facts of the death should have provoked some deep questions. The police report said that the body had first been found by an electrician who had entered the air-raid shelter to complete electric installation at 11 am on the 1st April. “He had at once telephoned the police. Nothing had been disturbed by him.” Police photographers then took pictures of the body, which was then removed: a list of possessions found on the body was made. Yet when After the Battle published the results of its investigation in 1976, it told how its researcher had interviewed Mrs. Alice Stutley, who had been Air Raid Shelter Marshal for her area in 1941. She told her interviewer that she had been walking her dog in the park, Christ’s Pieces, where six air-raid shelters stood. At about 9 a.m. a small boy came up to her and said that there was a dead man in the second shelter. She at first took the observation as an April Fool’s Day joke, but, when the lad persisted, inspected the site herself, confirmed that a corpse was there, and informed the police, who likewise thought she was jesting. When he finally agreed, she showed him the body. She heard nothing more until that evening, when she received a knock on the door, and two unidentified men asked her if she was the one who had found the body. ‘When she said she was they warned her in no uncertain terms to keep it to herself and not to say a word to anybody”.

Yet they were too late. Apparently, the next day the Cambridge News contained details of the discovery (according to After the Battle), but they were withdrawn after an urgent call from the Ministry of Information, the government department responsible for censorship. In the 1974 interview, Mrs Stutley told the investigator that the fact that the name of the dead man was ter Braak and that he was a German spy was ‘common knowledge amongst the older residents of the area’. And small boys talk.

But now we come to the most arresting part of the story. I present the photographs of the corpse here – the pictures that the authorities might cause ‘some distress’. In his words, Mrs Stutley also told the investigator the following: “She found the body of a man, dressed in a dark overcoat, horn-rim glasses and black homberg (sic) hat, wedged tightly underneath one of the fixed slatted seats. She could see no pistol but it was evident that he had been shot in the head.” Unless Mrs Stutley had some strangely defective vision, which allowed her to see accurately the details of ter Braak’s body but not the weapon a foot in front of it, or had some inexplicable reason to lie, her evidence would suggest that the weapon was not present when she inspected the corpse, but must have been later planted next to it.

Apart from that, one cannot look at the sad photograph without thinking: how could a man who committed suicide manage to wedge himself underneath a seat after he shot himself? And, as the police report informs us, ‘a bullet wound was traced above the left ear’. Even an amateur criminologist could point out that, in order for a suicide to shoot himself in the left side of his temple, he would have to be left-handed. Was that so? Did a graphologist ever study the writing in his letter to the Feltham Food Office (shown below), or ask his landladies whether they noted how he wrote? To me, the slant of the words in his letter suggests the script of a right-hander, but should that not have received expert analysis? Was the weapon inspected for any fingerprints? The report tells us that it was a Browning Automatic Revolver, No 468225, Calibre 7F/M55. Did the bullet-hole match the calibre of the pistol? And was the weapon traceable? It certainly looks like a Browning High Power, manufactured in Belgium under German control from 1940: did MI5 record whether such a device was found on other agents? As I noted earlier, the report on Gösta Caroli tells us that he carried an unnamed German revolver, and the After the Battle story, in its more fanciful exposé of ter Braak’s room being searched, relates that a Luger was found in his possessions. Whatever the real facts were, the whole process of the post-mortem shows an extraordinary slackness and naivety. Perhaps the authorities though they would get away with it, as they believed the photographs would never come to light, and that they had instantly hushed the source of any dissent and rumour that might shed light on the true circumstances of ter Braak’s death.

Certainly, there were circumstances that might have led ter Braak to consider suicide: he was running out of money, the Food Office was tightening up on his papers, and he may have felt abandoned if and when he ventured out at night to make contact with someone who could provide him with money, and no help came. Why did he cover himself in newspapers, no doubt to keep warm, if he had already considered killing himself as an option? Did he consider all hope gone when he failed to make contact with another parachutist? That seems unlikely, as none was scheduled to help him: Richter was dropped later to verify whether TATE had been turned, not to help ter Braak. Did he receive guidance to make a rendez-vous with SNOW, perhaps, and was then ambushed? Was another agent actually scheduled to parachute in, like Fackenheim, but was frustrated by the weather? These questions may remain unanswerable unless further documents are released.