A few months ago, I noticed an advertisement that Aeroflot, the Russian carrier, had placed in the New York Times. The appearance reminded me of an approach I had made to the airline over forty-five years ago, in England, when, obviously with not enough serious things to do at the time, and maybe overtaken by some temporary lovelorn Weltschmerz, I had written a letter to its Publicity Manager, suggesting a slogan that it might profitably use to help promote its brand.

Miraculously, this letter recently came to light as I was sorting out some old files. I keep telling my wife, Sylvia, that she need not worry about the clutter that I have accumulated and taken with me over the years – from England to Connecticut, to New Jersey and to Pennsylvania, and then back to Connecticut before our retirement transplantation to North Carolina in 2001. The University of Eastern Montana has generously committed to purchasing the whole Percy archive, so that it will eventually be boxed up and sent to the Ethel Hays Memorial Library in Billings for careful and patient inspection by students of mid-twentieth century social life in suburban Surrey, England.

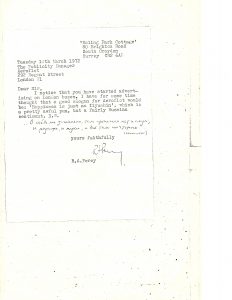

I reproduce the letter here:

It reads:

“Dear Sir,

I notice that you have started advertising on London buses. I have for some time thought that a good slogan for Aeroflot would be: ‘Happiness is just an Ilyushin’, which is a pretty awful pun, but a fairly Russian sentiment. E.G.

. . .В себя ли заглянешь, там прошлого нет и следа;

И радость, и муки, и всё там ничтожно . . . (Lermontov)

Yours faithfully, R. A. Percy”

[Dimitri Obolensky, in the Penguin Book of Russian Verse, translates this fragment of an untitled poem as follows: “If you look within yourself, there is not a trace of the past there; the joys and the torments – everything there is worthless . . .”]

I am not sure why Aeroflot was advertising on London Transport vehicles at the time, since the Man on the Clapham Omnibus was probably not considering then a holiday in Sochi or Stalingrad, and anyone who did not have to use the airline would surely choose the western equivalent. Nevertheless, I thought my sally quite witty at the time, though I did not receive the favour of a reply. Did homo sovieticus, with his known frail sense of humour, not deem my proposal worthy of merit? After all, humour was a dangerous commodity in Soviet times: repeating a joke about Stalin might get you denounced by a work colleague or neighbour and sent to the Gulag, while Stalin himself derived his variety of laughs from ordering Khrushchev to dance the gopak late at night, and forcing his drinking-pals on the Politburo to watch him.

I think it unlikely that the state-controlled entity would have hired a Briton as its publicity manager, but of course it may not have had a publicity manager at all. Maybe my letter did not reach the right person, or maybe it did, but he or she could not be bothered to reply to some eccentric Briton. Or maybe the letter was taken seriously, but then the manager thought about Jimmy Ruffin’s massive 1966 hit What Becomes of the Broken-Hearted? (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQywZYoGB1g) , and considered that its vibrant phrase ‘Happiness is just an illusion/filled with darkness and confusion’ might not communicate the appropriate atmosphere as Aeroflot’s passengers prepared to board the 11:40 flight from Heathrow to Minsk. We shall never know.

My first real encounter with homo sovieticus had occurred when I was a member of a school party to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1965. As we went through customs after disembarking from the good ship Baltika, I recall the officer asking me, in all seriousness, whether I was bringing in ‘veppons’ with me. After verifying what he had asked, I was able to deny such an attempt at contrabandage. I had conceived of no plans to abet an armed uprising in the Land of the Proletariat, as I thought it might deleteriously affect my prospects of taking up the place offered me at Christ Church, Oxford, the following October. Moreover, it seemed a rather pointless question to pose, as I am sure the commissars would have inspected all baggage anyway, but perhaps they would have doubled my sentence if they had caught me lying to them, as well as smuggling in arms. Yet it showed the absurd protocol-oriented thinking of the security organs: ‘Be sure to ask members of English school groups whether they are smuggling in weapons to assist a Troyskyist insurrection against the glorious motherland’.

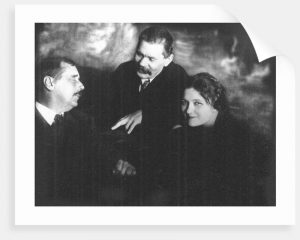

At least it was not as naïve as the question that the US customs officer asked me, when I visited that country for the first time about eleven years later: ‘Do you have any intentions to overthrow the government of the United States?’. Did he really expect a straight answer? When H. G. Wells asked his mistress, Moura Budberg, whether she was a spy, she told him very precisely that, whether she was a spy or not, the answer would have to be ‘No’. That’s what spies do: lies and subterfuge. If I really did have plans for subversion in the United States, the first thing I would have done when I eventually immigrated here would be to plant a large Stars and Stripes on my front lawn, and wear one of those little pins that US politicians choose to place in their lapels, in the manner that Guy Burgess always sported his Old Etonian tie, to prove their patriotism. So the answer in Washington, as in Leningrad, was ‘No’. That was, incidentally, what Isaiah Berlin meant when he wrote to his parents in July 1940 that Americans were ‘open, vigorous, 2 x 2 = 4 sort of people, who want yes or no for an answer. No nuances’. These same people who nailed Al Capone for tax evasion, and Alger Hiss for perjury, would have to work to convict Tony Percy for the lesser charge of deceiving a customs official.

H.G. Wells, Maxim Gorky & Moura Budberg

I did not manage to speak to many homines sovietici during my time in the Soviet Union, but I did have one or two furtive meetings with a young man who was obviously dead scared of the KGB, but even keener to acquire nylon shirts and ballpoint pens from me, which I handed over at a night-time assignation in some park in Leningrad. That was clearly very foolish on my part, but it gave me an early indication that, despite the several decades of Leninist, Stalinist, Khruschevian and Brezhnevian indoctrination and oppression, the Communist Experiment had not succeeded in eliminating the free human spirit completely. Moreover, despite the ‘command economy’, the Soviets could not provide its citizens with even basic goods. When the Soviet troops invaded eastern Europe in 1944, among other violations, they cleared the shelves, grabbed watches, and marvelled at flush toilets that worked. As Clive James wrote in his essay on Coco Chanel: “It was the most sordid trick that communism played. Killing people by the millions at least had the merit of a tragic dimension. But making the common people queue endlessly for goods barely worth having was a bad joke.”

Piata-Victoriei Square, Bucharest

My only other direct experience with life behind the Iron Curtain was in Bucharest, in 1980. In an assignment on which I now look back on with some shame, I was chartered with flying to Romania to install a software package that turned out to be for the benefit of the Ministry of Home Affairs, probably for the Securitate. I changed planes in Zürich, and took a TAROM flight (not in an Ilyushin, I think, but in a BAC-111) to reach Ceausescu’s version of a workers’ paradise. The flight crew was surly, for they had surely glimpsed the delights of Zürich once more, but knew that they were trapped in Romania, and had probably been spied upon as they walked round one of the most glittering of the foreign cities. And yet: I had been briefed beforehand to bring in some good whisky and a stack of ‘male magazines’ to please my contacts among the party loyalists. This time, I was able to bypass customs as a VIP: my host escorted me past the lines directly to the car waiting for us, where I was driven to my hotel, and handed over my copies of The Cricketer and Church Times for the enjoyment of the Romanian nomenklatura. I spent the Sunday walking around the city. The population was mostly cowed and nervous: there was a crude attempt to entrap me in the main square. During my project, I was able to watch at close hand the dynamics of the work environment in the Ministry, where the leader (obviously a carefully selected Party apparatchik) was quick to quash any independence of thought, or attempts at humour, in the cadre that he managed. A true homo sovieticus daciensis.

The fantasy that occupied Lenin’s mind was that a new breed of mankind could be created, based on solid proletariat lineage, and communist instruction. The New Man would be obedient, loyal, malleable, unimaginative, unselfish, unthinking. Universal literacy meant universal indoctrination. The assumption was accompanied by the belief that, while such characteristics could be inculcated in captive youth, inherited traits of the ‘bourgeoisie’ would have to be eradicated. The easiest way of achieving that was to kill them off, if they did not escape first. There were almost as many executions in the Red Terror of 1918 as there had been death sentences in Russian courts between 1815 and 1917, as Stephen Kotkin reminds us in Volume 1 of his epic new biography of Joseph Stalin. Kotkin also recounts the following: “Still, Lenin personally also forced through the deportation in fall 1922 of theologians, linguists, historians, mathematicians, and other intellectuals on two chartered German ships, dubbed the Philosophers’ Steamers. GPU notes on them recorded ‘knows a foreign language,’ ‘uses irony’.” Irony was not an attribute that homo sovieticus could easily deploy. What was going on had nevertheless been clear to some right from the start. In its issue of June 2, 2018, the Spectator magazine reprinted an item from ‘News of the Week’ a century ago, where Lenin and Trotsky were called out as charlatans and despots, and the revolution a cruel sham.

The trouble was that, once all the persons with education or talent had been eliminated or exiled, there were left only hooligans, psychopaths, or clodpolls to run the country. Kotkin again: “A regime created by confiscation had begun to confiscate itself, and never stopped. The authors of Red Moscow, an urban handbook published at the conclusion of the civil war, observed that ‘each revolution has its one unsightly, although transient, trait: the appearance on the stage of all kinds of rogues, deceivers, adventurists, and simple criminals, attaching themselves to power with one kind of criminal goal or another. Their danger to the revolution is colossal.’” This hatred of any intellectual pretensions – and thus presumptions about independent thinking – would lead straight to Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, with their execution of persons wearing eyeglasses, as they latter could obviously read, and thus might harbour ideas subversive to agrarian levelling.

Oleg Gordievsky

Oleg Gordievsky, the KGB officer who defected to Britain in 1985, crystallized the issue in his memoir Next Stop Execution. “Until the early 1970s I clung to the hope that the Soviet Union might still reject the Communist yoke and progress to freedom and democracy. Until then I had continued to meet people who had grown up before the revolution or during the 1920s, when the Soviet system was still not omnipotent. They were nice, normal Russians – like some distant relatives of my father who were engineers: not intellectuals or ideologues, but practical, decent people, embodying many of the old Russian engineer characteristics so well described by Solzhenitsyn. But then the last of these types died out, and the nation that emerged was composed purely of Homo sovieticuses: a new type had been created, of inadequate people, lacking initiative or the will to work, formed by Soviet society.” [The author acknowledged the ungrammatical plural form he used.] Thus Gordievsky classified both the common citizenry intimidated into submission and the apparatchiks themselves as homines sovietici. He also pointed out that what he found refreshing in English people generally was their capability for spontaneity, their discretion, their politeness, all qualities that had been practically eliminated in Russia under Communism. He may have been moving in sequestered circles, but the message is clear.

I sometimes reflect on what the life of a Soviet citizen, living perhaps from around 1922 to 1985, must have been like, if he or she survived that long. Growing up among famine and terror, informing against family members, with relatives perhaps disappearing into the Gulag because of the whisperings of a jealous neighbor, or the repeating of a dubious joke against Stalin, witnessing the show-trials and their ghastly verdicts, surviving the Nazi invasion and the horrors of serving in the Soviet armed forces, and then dealing with the long post-war deprivation and propaganda, dying before the curtain was pulled back, and the whole horrible mess was shown to be rotten. Yet some citizens had been taken in: they believed that all the suffering was worthwhile in the cause of Communism. In Secondhand Time, the nobelist Svetlana Alexievich offers searing portraits of such persons, as well as of those few who kept their independence of thought alive. Some beaten down by the oppression, some claiming that those who challenged Stalin were guilty, some merely accepting that it was a society based upon murder, some who willingly made all the sacrifices called for. Perhaps it was a close-run thing: the Communist Experiment, which cast its shadow over all of Eastern Europe after the battle against Fascism was won, almost succeeded in snuffing out the light.

(Incidentally, in connection with this, I recommend Omer Bartov’s searing Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz, published this year. Its title is unfortunate, as it is not about genocide. It tells of the citizens of a town in Galicia in the twentieth century, eventually caught between the monsters of Nazism and Communism. It shows how individuals of any background, whether they were Poles, Ruthenians, Ukrainians, or Jews, when provoked by pernicious demagogues or poisonous dogmas, could all behave cruelly to betray or murder people – neighbours – who had formerly been harmless to them. All it took was being taken in by the rants of perceived victimhood and revenge, or believing that they might thus be able to save their own skins for a little longer by denouncing or eliminating someone else.)

I was prompted to write this piece, and dredge out some old memories, by my reading of Odd Arne Westad’s The Cold War a few months ago. In many ways, this is an extraordinary book, broad in its compass, and reflecting some deep and insightful research. But I think it is also a very immoral work. It starts off by suggesting, in hoary Leninist terminology, that the battle was between ‘communism’ and ‘capitalism’ – a false contrast, as it was essentially between totalitarianism and liberal, pluralist democracy. (For a fuller discussion of this issue, please read Chapter 10 of Misdefending the Realm.) Westad goes on to suggest that the Cold War’s intensity could have been averted if the West had cooperated with the Soviet Union more – a position that ranks of sheer appeasement, and neglects the lessons of ‘cooperation’ that dramatically failed in World War II. (see https://coldspur.com/krivitsky-churchill-and-the-cold-war/) But what really inflamed me was the following sentence: “There were of course dissidents to this ameliorated view of the Cold War. In the Soviet Union and eastern Europe some people opposed the authoritarian rule of Communist bosses.” On reading that, I felt like hurling the volume from a high window upon the place beneath, being stopped solely by the fact that it was a library book, and that it might also have fallen on one of the peasants tending to the estate, or even damaged the azaleas.

‘Some people opposed the . . . rule’? Is that what the Gulag and the Great Terror and the Ukrainian Famine were about, and the samizdat literature of the refuseniks, and the memoirs of Nadezhda Mandelstam and Yevgenia Ginzburg, and the novels of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and many many more? Did these people protest noisily in the streets, and then go home to their private dwellings, resume their work, perhaps writing letters to the editors of progressive magazines about the ‘wicked Tories’ (sorry, I mean ‘Communists’)? How on earth could a respectable academic be so tone-deaf to the sufferings and struggles of the twentieth century? Only if he himself had been indoctrinated and propagandized by the left-wing cant that declares that Stalin was misunderstood, that he had to eliminate real enemies of his revolution, that the problem with Communism was not its goals but its execution, that capitalism is essentially bad, and must be dismantled in the name of Equality, and all that has been gradually built with liberal democracy should be abandoned. Roland Philipps, who recently published a biography of Donald Maclean (‘A Spy Named Orphan’), and who boasts both the diplomat Roger Makins (the last mandarin to see Maclean before he absconded to Moscow) and Wogan (‘Rockfist’) Phillips (who served as an ambulance-driver with the Republicans in Spain) as his grandfathers, asked Wogan, shortly before he died in 1993, where he stood on the durability of Communism. “He said that Stalin had been a disaster for the cause but that the system was still inherently right, would come round again, and next time be successful.” Ah, me. Wogan Phillips, like Donald Maclean, was a classic homo sovieticus to the end.

Wogan (‘Rockfist’) Phillips

As we consider the popularity of such as Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders, it is as if all the horrors of socialism have been forgotten. A few months ago, the New York Times ran a full-page report on the disaster of Venezuela without mentioning the word ‘socialism’ once: it was apparently Chávez’s and Maduro’s ‘populism’ that put them in power. A generation is growing up in China that will not remember Tiananmen Square, and the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution will not be found in the history books. Maybe there is an analogy to the fashion that, as a schoolboy, I was given a rosy view of the British Empire, and was not told of the 1943 famine in India, or the post-war atrocities in Kenya. But I soon concluded that imperialism was an expensive, immoral and pointless anachronism, and had no interlocking relationship with liberal democracy, or even capitalism, despite what the Marxists said. This endemic blindness to history is ten times worse.

So why did my generation of teachers not point out the horrors of communism? Was it because they had participated in WWII, and still saw the Soviet Union as a gallant ally against Hitler? Were they really taken in by the marxisant nonsense that emerged from the Left Bank and the London School of Economics? Or were they simply trying to ratchet down the hostility of the Cold War, out of sympathy for the long-suffering Soviet citizenry? I cannot recall a single mentor of mine who called out the giant prison-camp for what it really was. Not the historians, not the Russian teachers. The latter may have been a bit too enamoured with the culture to make the necessary distinction. Even Ronald Hingley, one of my dons at Oxford, who was banned from ever revisiting the Soviet Union after his criticisms of it, did not encourage debate. I had to sort it out myself, and from reading works like Robert Conquest’s The Great Terror, Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, Marchenko’s My Testimony, Mandelstam’s Hope Against Hope and Hope Abandoned, and Ginzburg’s Into the Whirlwind. On the other hand, under the snooker-table in my library rests a complete set of the Purnell History of the Twentieth Century, issued in 96 weekly parts in the 1960s. (Yes, you Billings librarians: soon they too shall be yours.) In part 37, that glittering historian, TV showman, hypocrite and Soviet stooge A. J. P. Taylor wrote: “Lenin was a very great man and even, despite his faults, a very good man.” For a whole generation, perhaps, the rot started here. That’s what we mostly heard in the 1960s. But Lenin was vicious, and terror was his avowed method of domination.

President Putin is now trying to restore Stalin’s reputation, as a generation that witnessed the horrors of his dictatorship is now disappearing. So is Putin then a homo sovieticus? Well, I’d say ‘No’. Maybe he was once, but he is more a secret policeman who enjoys power. The appellation should be used more to describe those cowed and indoctrinated by the regime rather than those who command it. Putin’s restoration of Stalin is more a call to national pride than a desire to re-implement the totalitarian state. Communism is over in Russia: mostly they accept that the Great Experiment failed, and they don’t want to try it again. More like state capitalism on Chinese lines, with similar tight media and information control, but with less entrepreneurialism. As several observers have noted, Putin is more of a fascist now than a communist, and fascism is not an international movement. Maybe there was a chance for the West to reach out (‘cooperate’!) after the fall of communism, but the extension of NATO to the Baltic States was what probably pushed Putin over the edge. The Crimea and Ukraine have different histories from those in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, and I would doubt whether Putin has designs on re-invading what Kotkin calls Russia’s ‘limitrophe’ again. He is happier selectively cosying up to individual nations of Europe, especially to those countries (e.g. Poland, Hungary, and now maybe Italy and Austria, and even Turkey) whose current leaders express sympathy for his type of nationalism, while trying to undermine the structure of the European Union itself, and the NATO alliance.

So whom to fear now – outside Islamoterrorism? Maybe homo europaensis? I suspect that the affection that many Remainers have for the European Union is the fact that it is a softer version of the Socialist State, taking care of us all, trying to achieve ‘stability’ by paying lip-service to global capitalism while trying to rein it in at the same time, and handing out other people’s money to good causes. And it is that same unresponsive and self-regarding bureaucracy that antagonizes the Brexiteers, infuriated at losing democratic control to a body that really does not allow any contrariness in its hallways. (Where is the Opposition Party in Brussels?) I did not vote in the Referendum, but, if I had known then of all the legal complexities, I might have voted ‘Remain’, and fought for reform from inside. But my instincts were for ‘Leave’. If the European Project means tighter integration, political and economic, then the UK would do best to get out as soon as possible, a conclusion other countries may come to. The more oppressive and inflexible the European Union’s demands are (to discourage any other defectors), the more vigorously should the UK push against its increasing stranglehold. That does not mean goodbye to Goethe and Verdi, or those comforting ’cultural exchanges’, but it does require a bold stance on trade agreements, and limitations on migration of labour. We should beware of all high-faluting political projects that are experimental, and which remove the responsibility of politicians to their local constituents, as real human beings will be used (and maybe destroyed) in the process. A journalist in the New York Times wrote a few weeks ago that he was ‘passionate’ about the European Union. That is a dangerous sign: never become passionate over mega-political institutions. No Communist Experiment. No New Deal. No Great Society. No European Project. (And, of course, no Third Reich or Cultural Revolution.) Better simply to embrace the glorious muddle that is liberal democracy, and continue to try to make it work. Clive James again: “It is now part of the definition of a modern liberal democracy that it is under constant satirical attack from within. Unless this fact is seen as a virtue, however, liberal democracy is bound to be left looking weak vis-à-vis any totalitarian impulse.” (I wish I had been aware of that quotation earlier: I would have used it as one of the headliners to Chapter 10 of Misdefending the Realm.)

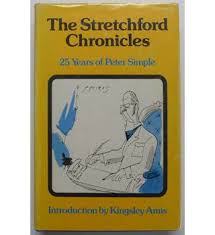

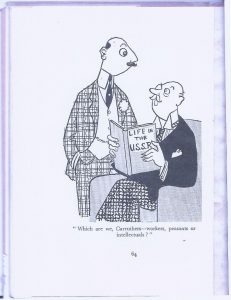

I close with a riposte to A. J. P. Taylor, extracted from one of the great books of the twentieth century, The Stretchford Chronicles, a selection of the best pieces from Michael Wharton’s Peter Simple columns in the Daily Telegraph, from 1955 to 1980. These pieces are magnificent, daft, absurd, hilarious, and even prescient, where Life can be seen to imitate Art, as Wharton dismantles all the clichéd cant of the times, and anticipates many of the self-appointed spokespersons of loony causes and champions of exaggerated entitlement and victimisation who followed in the decades to come. Occasionally he is simply serious, in an old-fashioned way, as (for example) where he takes down the unflinching leftist Professor G. D. H. Cole, who in 1956 was trying to rally the comrades by reminding them that ‘while much has been done badly in the Soviet Union, the Soviet worker enjoys in most matters an immensely enlarged freedom’, adding that ‘to throw away Socialism because it can be “perverted” to serve totalitarian ends is to throw out the baby with the dirty bath-water’. Writes Wharton:

“This is familiar and most manifest nonsense. What has gone ‘amiss’ in Socialist countries is no mere chance disfigurement, like a false moustache scrawled by a madman on a masterpiece. It is Socialism itself, taken to its logical conclusion.

The death of freedom, the enslavement of the masses, the withering of art and culture, the restless, ruthless hunt for scapegoats, the aggressive folie de grandeur of Socialist dictators – these are no mere ‘perversions’ of Socialism. They are Socialism unperverted, an integral and predictable part of any truly Socialist system.

We are not faced here with so much dirty bath-water surrounding a perfectly healthy, wholesome Socialist baby. The dirty bathwater is Socialism, and the baby was drowned in it at birth.”

New Commonplace entries can be found here.