Seasonal greetings to all my readers – especially those who joined the group this year! Among new contacts is one former officer of an intelligence service, who very kindly wrote, about ‘Sonia’s Radio’: “It’s the most impressive counter intelligence research/historiography I’ve read – the web of known and suspected affiliations is masterly.”

And now you can help spread the word! In a survey of a thousand households of recent retirees across the European Union, commissioned by the Coldspur Appreciation Society, residents were asked to list the Top Ten Items on their Bucket List. Here are the consolidated results (after some flattening of rankings according to the Ogden-Zeiss method of Flawed Preference Detection): ‘Reading “Sonia’s Radio”’ was pipped out of first place by ‘Visiting Machu Picchu’, but pushed ‘Snorkelling on the Great Barrier Reef’ into third position. A great outcome!

So all you have to do, laid out in five easy steps:

- Select your favourite e-card supplier;

- Choose your recipient;

- Write a personalised greeting;

- Insert https://coldspur.com/sonias-radio/ into the text;

- Press ‘Send’.

And you will immediately have made another close friend or relative very happy!

And now to those books . . .

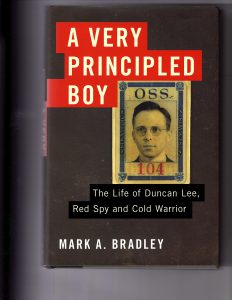

The Spy and the Traitor by Ben Macintyre (Crown New York, 2018)

Traitor Lodger German Spy by Tony Rowland (APS Publications, 2018)

Transcription by Kate Atkinson (Little Brown & Co., 2018)

The Secret World by Christopher Andrew (Yale University Press, 2018)

The Spy and the Traitor

How well do you know your Communist defectors? For instance, can you clearly distinguish and differentiate Igor Gouzenko, Anatoly Golitsyn, Michael Goleniewski and Oleg Gordievsky? (In the spirit of 1066 and All That, the use of protractors is encouraged.) No? Well, here’s a thumbnail sketch to help you prepare for that pub quiz. Gouzenko was the cipher clerk who worked for the GRU in Ottawa, and whose revelations in 1945 led to the unmasking of the atom spies. Golitsyn defected in 1961, and provided information that led to the confirmation of Kim Philby’s treachery. Goleniewski was a Pole, reputedly a triple agent, who helped identify George Blake as a spy within SIS. And Gordievsky was the KGB officer who turned against his employers after the invasion of Czechoslovakia, and in 1985 was spirited out of the Soviet Union in a daring escape organised by SIS.

The highly successful journalist Ben Macintyre, author of five gripping books about espionage and sabotage, has now turned his hand to the story of Gordievsky. The tale is not new: Gordievsky wrote a memoir titled Next Stop Execution, which gives almost as much detail about his career with the KGB, as well as the climax of the book, the enterprising escape plan, and how it was executed. (In recommending The Spy and the Traitor as one of his Books of the Year, Peter Frankopan wrote recently in the Spectator: “As with his other books, Macintyre seems not only able to find amazing new material, but to write perfectly paced prose that reads like a thriller.” I agree with the second part of the statement, but not the first.)

Shortly after being posted to London in early 1985, Gordievsky, who had made his desires and loyalties clear when an officer in Copenhagen, and had later provided much valuable information to help Margaret Thatcher negotiate with Gorbachev, was recalled to Moscow, ostensibly for some kind of confirmation process for his recent promotion to rezident. Instead he was immediately interrogated and put under surveillance on suspicion of being a spy. Fortunately for him, Soviet Intelligence was at that time taking a more formal approach to the determination of guilt. Taking advantage of a scheme devised by SIS long before, Gordievsky was able to signal to British Embassy officials that he was in danger, and made his plans for escape. He took a train to Leningrad, and hitched a ride to a place near the Finnish border, where he was picked up and hidden in the boot (trunk) of a car being driven by members of the embassy. He was then smuggled into Finland – an adventure which must surely lead to a movie before long. Macintyre has complemented that account by virtue of his being able to discuss the case freely with Gordievsky’s handlers in SIS (MI6) – a disturbing venture in its own right, given the implications of the Official Secrets Act, and one that raises some troubling questions about the reliability of Macintyre’s judgments.

First of all – that title. The Spy. And the Traitor. Is Gordievsky supposed to be both? Probably not. The traitor is probably meant to indicate Aldrich Ames, the CIA agent who was, somewhat remarkably, given his personality and drinking habits, the Soviet and East European Division’s chief of counter-intelligence, which allowed him to realise that an anonymous high-grade informer was being handled by the British. In order to deliver his high-expense wife the luxuries she demanded, Ames offered his services to the KGB, and was able to provide enough hints to Gordievsky’s background and movements that the Soviets concluded that the pattern of activity and geography cast a strong suspicion that Gordievsky might be the source of the leaks. Yet we should not forget that both men were traitors. I would probably be the last man to propose ‘moral equivalence’ in the actions and motivations of the two (see Misdefending the Realm, p 280, for example), but it is a matter of fact that both men were traitors to the nation they served. This is a vital point, because Gordievsky is still under a death sentence: Putin is reported to be livid with his former colleague’s treachery. An attempt has been made on Gordievsky’s life already, and he has to live in seclusion in darkest Surrey somewhere. (I know Surrey is still ‘leafy’. But do ‘dark’ portions of that county still exist?

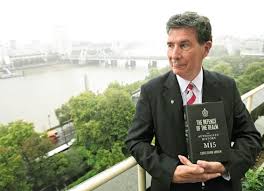

What Macintyre does well, he does very well. He has a journalist’s eye for the telling detail, weaves the relevant background material into his ripping yarn very smoothly, and keeps the suspense up extremely capably. Yet his judgment is fallible: he gets a little too close to his subject and the SIS officers who guide him through the story, and lacks the temperament and resolve to stand back coolly from the whole operation. Gordievsky has collaborated with Christopher Andrew on a couple of books since his defection, and, as I noted in last month’s blog, these were not received with the critical acclaim that the author appears to assume. I repeat Macintyre’s assertion: “He gave lectures, listened to music, and wrote books with the historian Christopher Andrew, works of detailed scholarship [sic] that still stand as the most comprehensive accounts of Soviet intelligence to date.” Macintyre echoes Gordievsky’s claim that the spy ELLI was Leo Long, Gordievsky having claimed to have found that detail in the KGB archives. Remarkably, Christopher Andrew used Gordievsky’s statement to voice the same opinion in his authorised history of MI5, The Defence of the Realm, as well as in other books he has written about the KGB, a mistake that has been criticised by historians ever since. (Andrew has declined to appear in forums to discuss this very controversial judgment, but Macintyre should have known about the problem.) It has been rumoured in some quarters that Gordievsky was encouraged by SIS to make the equivalence of ELLI and Long to distract attention from molehunts after more likely candidates . . . Again, Macintyre, in his enthusiasm, is reluctant to consider such matters worthy of discussion.

Then there is the case of Michael Foot. Macintyre repeats Gordievsky’s claim that the leader of the Labour Party had been a paid Soviet agent with the cryptonym BOOT (again showing the Soviet bureaucrats’ highly subtle choice of monikers to conceal the identity of their contacts). Macintyre accepts unquestioningly everything that Gordievsky says about Foot, how he was served with raw Soviet propaganda, and how he provided valuable information about Western political strategies from the Korean War onward. In recent weeks, the fortnightly magazine Private Eye has taken the cudgels up against Macintyre, coming to Foot’s defence, showing how his Tribune articles constantly criticised the Soviet Union, and thus showed that he was no friend of the Soviets. I think Private Eye may be jumping too quickly into the fray, too (Michael’s nephew, the late diehard Socialist Paul Foot, is still a much-revered figure at Gnome House). It is possible that Michael Foot conveyed an anti-Soviet stance in Tribune to cover his activities as an agent of influence, but the magazine has showed that Macintyre has tied himself in knots over the chronology of Gordievsky’s awareness of Foot’s activities. However, both Macintyre and Private Eye fail to use the diaries of Anatoly Chernyaev, the Kremlin’s liaison with the Labour Party, which have been translated and are available at the National Security Archive (see https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB192/index.htm ), and would appear to confirm Foot’s foolishness, if not malfeasance. ‘This one will run and run’, in the words of one of Private Eye’s favourite slogans.

And was Macintyre being used by his SIS friends? He carefully explains (in his Acknowledgments) that his work is not an authorised biography, and takes pains to explain that he has had ‘no access to the files of the intelligence service, which remain classified’. Yet he is naïve enough to state that the book was not aided by SIS, having shortly before expressed his huge gratitude to ‘every MI6 officer involved in the case’. If that is not ‘aid’, what is? On page 79, he writes that ‘the correspondence between SUNBEAM and C remains in the MI6 archives, proof of the personal touch on which successful spying depends.” If that is some ‘proof’ to which Macintyre can attest, has he actually inspected it? Even to know that the correspondence exists seems to me an outrageous liberty granted by SIS to the journalist. I do not understand how, given the constraints of the Official Secrets Act, SIS officers were allowed selectively to pass on confidential material to a chosen writer, and get away with it.

But perhaps I do. Macintyre is careful to conceal his contacts under aliases. Gordievsky’s main handler in London is identified as ‘James Spooner’, but Christopher Andrew, in The Secret World (see below) has identified ‘Spooner’ as John Scarlett, who later became chief of SIS. So we must interpret this joint venture between SIS and Macintyre as another in a line of valiant PR exercises by the intelligence services, which started with Alan Moorhead’s The Traitors in 1952. So long as there is a positive story to tell, which shows up the imagination and dedication of the Secret Intelligence Service in a good light, SIS will arrange for a reliable journalist/historian to tell the tale, and break its own rules in so doing. The Spy and the Traitor will be immensely successful, and like other popular retreads of Macintyre’s, will no doubt be enjoyed by millions, but his books should not be regarded as serious history, as they constitute a potpourri of fascinating facts and unreliable information. Moreover, if there is a serious reappraisal of Anglo-Soviet relations to be undertaken, it should not be at the whim of John Scarlett, allowing selective disclosure by the triumvirate of Andrew, Gordievsky and Macintyre. The material on which their statements are based should be made generally available to historians at large.

Traitor Lodger German Spy

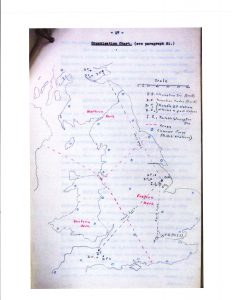

Tony Rowland (a nom de plume, as the author wishes to stay anonymous) has chosen, for his crafting of a novel about the mysterious German agent, broadly the same archival documents on ter Braak that I used in my September analysis (see TheMysteryoftheUndetectedRadiosPart3). ‘Based on a true story’, the back cover boasts, but, as readers who have studied my explanation would probably agree, exactly what the true story was is open to a large amount of controversy. Mr. Rowland has overall ingeniously translated the fragments available at the National Archives on Engelbertus Fukken (ter Braak’s real name) into a gripping tale of treachery and murder, but, since the bare threads of the Abwehr agent’s life evading capture have been embellished by the insertion of a completely artificial and unconvincing personage of a Cambridge Professor who is (as far as I can judge) nowhere to be found in the archival records, the story unnecessarily loses its grip with reality.

That is not to say that the fiction is unenjoyable. Rowland has done his homework: he portrays Cambridge in 1940 in very convincing fashion, he is good with dialogue, he represents police procedures with authority, he understands well the political issues at home as well as the sensitive dynamics of the Abwehr, and the subversive mentality of its leaders. He presents the complex issues of wireless telegraphy soundly, and realistically brings in both Bletchley Park and the Cavendish Laboratory as possible targets of ter Braak’s mission. He very sensibly questions the denials by Abwehr officers that they could identify ter Braak, as well as the repeated claims that the arrival of the parachutist Josef Jakobs had nothing to do with ter Braak’s plight. He has done an excellent job of bringing life into the two-dimensional characters who largely people the documents released by MI5. It may be that the person-in-the-street, unfamiliar with what appears in the archives, will find Traitor Lodger German Spy an engrossing spy story and not be concerned about where the author’s imagination has run away with him.

The primary problem, as I see it, is that Rowland presents MI5 as ‘moving heaven and earth’ to find ter Braak, when it is clear from the archives, and from the way Rowland faithfully reflects that part of the story, that the Security Service attempted no such thing. Thus his fiction fails to take on with any resolve the paradox central to ter Braak’s status as a fugitive. How could an escaped German parachutist, at a time when a small densely populated country was on alert for any alien presence, and when enemy agents had been swiftly captured elsewhere, survive for so long, living among apparently unsuspicious civilians and officials? And why would he dabble with the Cambridge netherworld so dangerously, and thus draw attention to himself? Moreover, the background, personality, activities and discoveries of the person that really drives the plot, the Professor (about whom I shall write no more detail, as it would spoil the reader’s enjoyment), were to me so unconvincing as to pull the story out of its realistic framework.

Perhaps my experience in trying to analyse what the ‘true story’ about ter Braak was make me an unsuitable critic of Mr. Rowland’s experiment. To me, the questions naturally surrounding what went on in those hectic months of the winter of 1940-41 are fascinating enough without bringing in in any deus ex machina. In an email exchange, Mr. Rowland told me that he had ‘made no attempt to stick with the recorded facts, or indeed cold logic, where they don’t fit with the plot.’ That struck me as an odd argument to make: if the plot drove everything, why attempt to promote the book as being based on a true story, while emphasizing the process of researching the story in ‘the files of the National Archives at Kew, the Cambridge Archives . . .’? (Rowland appears to have overlooked the very considerable facts about ter Braak uncovered in the articles in After the Battle magazine.) He does credit, however, two writers with a significant interest in the story, a Dutch writer Jan-Willem van den Braak, and Giselle Jakobs, the granddaughter of Josef Jakobs (who was executed later in 1941) with assisting him with the results of his research. I have not read the contributions of either (apart from blogs posted on the latter’s website), but why would the author go out of his way to incorporate information from them, only to dismiss certain facts as inconvenient for his plot?

In an imagined world of fiction, the plot should derive from the convincing but probably flawed characteristics of the participants, and not be a mechanism of its own that relies on artificiality and unexplainable events. Rowland has the skills to have made this a more convincing tale. I am very supportive of efforts to bring the strange history of ter Braak into the public eye, but the bare facts as revealed by the archives provide enough opportunity for weaving an engrossing story about a brave but misguided man during a fascinating winter in history, without the introduction of unconvincing melodrama.

Transcription

I do not read much fiction these days, but this title caught my eye. Kate Atkinson was not a name I knew, but her latest work was suddenly being reviewed everywhere, she was being interviewed by the New York Times, and Transcription quickly made its way into the NYT best-seller list. More relevantly, it was a novel about a period that I know fairly well – the spring and summer of 1940 when Britain came under a ‘Fifth Column’ scare. So I thought I should acquire the book, and see what was going on.

The story concerns a young lady, an orphan, who is recruited by MI5 to assist in a surveillance operation against Fascist sympathisers. After working as a transcriber of the recorded conversations that the potential traitors engage in, innocently believing they are having an exchange with a Gestapo officer under cover in Dolphin Square, Juliet Armstrong is asked to take part in a more aggressive project to entrap one of the ladies who is facilitating the illicit passing of information from the American Embassy. This leads to further complications, both romantic and political – including a murder carried out and concealed by MI5 – and an estrangement from the MI5 agent who was responsible for carrying out the deception. After the war, she is called on again to provide a safe house for a fleeing scientist from behind the Iron Curtain, and things go wrong, which lead to her being persecuted. The narrative starts with her death when hit by a car in London in 1981, and flashes back to 1940 and 1950, when she was working for the BBC.

My first, highly distracting, impression was that Ms. Atkinson overloaded her reach for historical authenticity by including too many reasonably well-known historical figures masquerading under invented names. Thus Peregrine Gibbons, the handler of agents who works from his residence in Dolphin Square, is incontrovertibly the nature-lover of ambiguous sexuality, Maxwell Knight, who, like Juliet, moves over to the BBC to work after the war. Godfrey Toby, who mysteriously ‘cuts’ Juliet after the war, is Eric Roberts, working for Knight, who pretended to be a representative of the Gestapo in encouraging the Fascist ladies. Oliver Alleyne, who is Gibbons’ boss, and who also recruits Juliet for special tasks, is presumably Guy Liddell: the name Alleyne is perhaps a deliberate echo of John Le Carré’s Percy Alleline. Miles Merton, ‘the intellectual communist’, must be based on Anthony Blunt. I glimpsed Olga Gray, and saw traces of Joan Miller (author of One Girl’s War) in Juliet. The American spy Chester Vanderkamp is indubitably the author’s name for Tyler Kent, and his partner in crime Mrs. Scaife is Anna Wolkoff of the Russian Tea Room. The introduction of a dog named Cyril who is withheld from his owner, a double-agent, clearly comes from the case-history of Anna Sergueiew. Etc. etc.

But why all the distortions? The author gets dates wrong, for instance, misrepresenting Knight’s career. She greatly overstates the function of the perceived Nazi sympathisers, a set of chattering ladies, as a ‘Fifth Column’, when it bore none of the characteristics of a force ready to take up arms in the event of an invasion. Even though Maxwell Knight’s official report on the operation (written much later) called it that, the Fifth Column menace did not rear its head until the Low Countries and France succumbed to Nazi invasion, and then blew over in a couple of months. Victor Rothschild and Anthony Blunt did not join MI5 until May of 1940. Roger Hollis was not yet a prominent officer of MI5. Ms. Atkinson anticipates the execution of German spies by about a year. The Sergueiew incident did not occur until 1943. Some of this may be deliberate – an attempt to show that the experts in counter-espionage were as deceived as anybody as to what was going on. As another MI5 officer (Hartley, who also wants to use Juliet as ‘his girl’ on a project) says: “Storm in a teacup, all that stuff about the fifth column. Bunch of frustrated housewifes, most of them. Gibbons was obsessed with them. Anyway, you were looking at the wrong people – you should have been looking at the communists, they were always the real threat.”

So what we find here is more playing fast-and-loose with historical figures. And then I found that the author is quite candid about such games. In her ‘Author’s Note’, she admits that she ‘got a lot of it wrong, on purpose’, and ‘invented what she felt like’. Her sources show all the familiar titles (although she appears not to have used Henry Hemming’s recent biography of Maxwell Knight), and she has plucked from these the anecdotes and characters that suited her. But why? What she ends up with is neither authentic documentary nor imaginative fiction. She describes the process as ‘a wrenching apart of history followed by an imaginative reconstruction.’ No, madam: this is no Wolf Hall. And the plot is no stellar composition to compensate: the character of Juliet (who is mildly interesting to begin with, although this reviewer, appropriately sensitised by the #MeToo movement, found her urgent desires to be seduced by one or more of her mentors a trifle unsavoury) dissolves into a blur. Her involvement in a murder, and MI5’s disposal of the body, is simply melodramatic. Juliet never shows the aptitude or inclination to be a spy, and simply becomes a creature of apparently unexplained events. If there were subtle hints of her eventual political convictions to be found in earlier scenes, they certainly escaped me. I had lost interest in her before the twist in her career became clear.

Is there a deeper message here? Does ‘Transcription’ have something to do with ‘Deception’ or ‘Distortion’? Are the struggles and delusions of the Security Service an allegory of some post-imperial hangover? Does the ‘transcription’ carry a genetic metaphor, reflecting some process of DNA copying? “Search me, guv!”, as Harold Pinter responded when an enthusiastic devotee asked him for confirmation as to what one of his plays meant. One critic of this ‘superb story of wartime espionage’ (Gerry Kimber, in the Times Literary Supplement) declared that ‘readers will eventually learn that nothing they encounter here can be taken at face value: in this novel the dividing line between truth and lies is only smoke and mirrors.’ But thriving on smoke and mirrors can lead to intellectual sloppiness, and allow the writer to get away with all manner of carelessness. This novel has many moments of humour, and insights into the world of 1940 Britain and 1950 BBC that I found convincing and familiar, even, but Juliet’s arch asides became tiresome after a while, and I was not convinced by the actions and motivations of anybody.

As readers of my critiques will now have concluded, I am not a fan of ‘novels’ which attempt to compensate for their lack of creativity in credible plot and characterisation by drawing on historical sources in a highly selective manner. And I do not think I am alone, as the recent controversy over the distortion of facts by Heather Morris in her best-selling The Tattooist of Auschwitz shows. The author’s editor at Harper Collins was quoted as saying: “It’s a novel so it didn’t need to be fact-checked, though a novel needs to have verisimilitude.” But then it should not emphasise the ‘true story’ aspect if it plays around with the facts, as the alert reader will question everything else. I happened to turn next for my bedtime reading to an often neglected book by John le Carré that truly covers the ‘smoke and mirrors’ theme: The Looking-Glass War (1964). In his Foreword, le Carré writes: “None of the characters, clubs, institutions nor intelligence organisations I have described here or elsewhere exists, or has existed to my knowledge in real life.” That’s more like it, guv! (Though he had to say that, as they obviously did. But that’s a story for another day.)

The Secret World

For any collector of books on intelligence, Christopher Andrew’s latest work must be a necessary addition, probably to join other serious companions on the shelf of authorised histories. Yet, if such bibliophiles are like me, there will no spare space on any of their shelves, and it will have to take its place on one of the piles on the bridge-table, or heaped on the grand piano, unless I consider reclaiming shelf-space from some valuable but less solemn volumes that will be relegated to the annex. On reflection, I do not think the last option is likely. For all its 760 pages of Text, 58 pages of Sources, and 55 pages of Notes, I doubt whether I shall be referring to The Secret World often. Weighing in at three-and-a-half-pounds, however, it will undoubtedly bust many blocks. (And maybe block a few busts on top of the piano.)

So what is it about? Its subtitle runs ‘A History of Intelligence’, but the flyleaf claims that it is ‘the first global history of espionage ever written’, which is not the same thing at all. Espionage, counter-espionage, information-gathering, propaganda, deception: all those I might include under ‘Intelligence’, but I would certainly not consider state-arranged murder of its own citizens, or covert assassinations of foreign politicians, as part of that domain. Yet, in his Introduction, Andrew provocatively claims that they are. Thus, while it may be illuminating to make comparisons between the Spanish Inquisition and Stalin’s Great Terror of 1938, I question whether the classification of mass murder of innocent persons as a matter of ‘intelligence’ reflects a solid humanitarian judgment. Simply because the institution that carried out the executions was also responsible for spying on the populace, that fact does not contribute valuably to the study of the suitable deployment of ‘intelligence’ in domestic or foreign affairs. Andrew reinforces this unhappy theme by relating, in the concluding chapter, the worldwide assassination exploits of the Israeli intelligence organisation, Mossad, and controversially appears to approve such aggression as a winning strategy of ‘the most recent of the world’s most successful intelligence agencies’ in protecting the country. While ‘intelligence’ must be largely secret, however, not all that is secret counts as intelligence. These are shifting and controversial territories to be working in, and some moral compass is required.

Andrew’s dominant message is that a professional unawareness of how intelligence has been successfully (and unsuccessfully) deployed leads to repeated mistakes. Yet, as he explains in his Introduction, the excessive secrecy that attends to its role leads to delayed recognition of such awareness and to an uninformed populace. Records are not released, and histories are written with incomplete information or concealed knowledge (e.g. by such leading lights as A. J. P. Taylor and Winston Churchill respectively), with the result that whole generations are brought up on inadequate or distorted accounts of what primarily influenced outcomes. As he says, the public was protected from knowing about Ultra and the Double-Cross system decades after the events. But he does not analyse (as an outsider) or explain (as an insider) why secrets are maintained for so long. The Double-Cross system was never going to be exploited successfully against the Soviet adversary, no matter that some had delusions that it could be. Germany was never going to gain a revanchist advantage from learning how its Enigma messages had been decrypted, and the science of cryptology moved on. The VENONA secret was maintained for fifty years, but the Soviets knew about it from their spies anyway, and had fixed any procedural problems that the project would have revealed. (Moscow frequently knew much more than Britain’s Joint Intelligence Committee about what was really going on in the UK’s Secret World, a point that Andrew does not explore in depth.)

At the end of the book, Andrew returns to this important question of secrecy, dedicating a few pages to Wikileaks, making the claim that not much damage was in fact performed through this breach, and that government secrets have been betrayed for centuries. But, in that case, why has the US Government granted the highest-level security clearance to one-and-a-half million employees and consultants? How could it possibly monitor and maintain a system that pretended that it could vet and trust so many persons, and that the exposure of the secrets that had been entrusted to them would cause ‘exceptionally grave damage’? And why do MI5 and SIS display such a possessive and secret attitude to files that can have no possible bearing on today’s security challenges, and refuse to release folders that have by far outlived their shelf-life? This is the obverse of Andrew’s assertion, which he does not inspect at all. (Yet it was one that came through very clearly in his 1984 collaborative work with David Dilks, The Missing Dimension.)

The bulk of the book consists of a walk through intelligence history over the millennia, but it lacks much of a roadmap. One looks, therefore, to the final chapter for perhaps a thematic summing-up. This chapter is not titled ‘Conclusions’, however, but ‘Conclusion: Twenty-First Century Intelligence in Long-Term Perspective’. Rather than neatly integrating the lessons from the past, the section disappointingly rambles all over the place, introduces much new material, and ends with the rather plodding assertion: “The more that is discovered about the long-term history of intelligence, the more difficult it will be for both policymakers and practitioners to ignore past experiences”, as if the publication of this book will suddenly make ministers, intelligence chiefs, and watchdogs around the world all suddenly perk up when Andrew had presumably not been able to convince them beforehand of the errors of their ways. Well, maybe. Old habits die hard. And if the ‘Yoda’ (see FourBooksonEspionage) of intelligence studies cannot improve matters, who will be able to? But that is what you are paying for.

To reach that conclusion, the reader will have waded through a rich cavalcade of histories of espionage and deceit through the ages. The early parts had a little too much religion and mythology for my liking, much of the story having an anecdotal and unreliable aspect that may not bear much rigorous examination. (His narrative also served to remind me how the interminable feuds between Catholics and Protestants disproportionately influenced state policies, and how calamitous such futile religious commitments were for the peace of Europe.) Thereafter, the reader can pick up some of the lessons that recur over the centuries: the analogies between Ivan the Terrible and Stalin, for instance; the fact that despots want to be told what they have already preconceived (the difficulty of telling ‘Truth-to-Power’), disdaining intermediary intelligence-analysing bodies; and the requirement for governments to avoid proving an allegation against a foreign power by disclosing the clandestine channel through which they acquired it. (Though the existence of those hidden cameras in the Saudi Arabian embassy in Ankara had to be revealed for the greater good.)

But it would have been useful for Andrew to have identified up-front some themes that were important to the use of intelligence in strategy, and relate them to the epochs he studies. For example, how relevant today are lessons from the Second Punic War as opposed to those from WWII? What technological developments in the past fifty years have caused strategic assessment to change? In the final chapter he tries to recapitulate, by making some highly important points about the necessity for imagination when assessing the motivations and practices of the foe: these indeed point to some enduring patterns. Thus he shows how important open-ended questions for agents assessing German weapons programmes in WWII were, a lesson forgotten by the CIA sixty years later when it sought intelligence on Iraq. And he reminds us that both Stalin’s and Hitler’s obsessions, at different times of the war (Stalin’s determination to assassinate Trotsky, Hitler’s pursuit of the Final Solution) were completely misread by intelligence analysts in the West. Yet only in the last sentence of the penultimate chapter does he introduce his theory of Historical Attention-Span Deficit Disorder (HASDD), which he had briefly introduced in his Introduction. Why so late? Moreover, this is a global study: is misuse of intelligence cancelled out if it is perpetrated by adversaries, such as the West on the one side and Russia or China on the other? It is as if he (rightly) feels uncomfortable about giving advice to regimes for whose goals he does not bear any sympathy, but this matter is never explored.

By dint of this rather strange structure, Andrew does not really perform justice to the richness of lessons to be learned. Would it not have been educational, for instance, to make some comparisons between surveillance and containment activities undertaken by totalitarian regimes to further their control over perceived enemies, and those pursued in constitutional democracies? How should policies differ in peace and war, and how should they change in that time when the former drifts into the latter? What lessons should we take from the successes of state-sponsored assassination – that it works for some democracies, but not others, and is not justifiable when committed by more authoritarian states (Israel, yes, but not Russia or North Korea, perhaps)? It would have been enlightening if he had offered an analysis of how many of Israel’s 2700 targeted killings were a) strategically beneficial, and b) justifiable. Such passages really shocked this reader, who looked for more context and analysis.

It would also have been useful for him to have explored the question of political organisation of intelligence. For example, should leaders’ recognition of the strategic value of intelligence be translated into close contact with intelligence heads, or should it concentrate instead on the building of the appropriate processes and structures, and the recruitment of the right people (not potential traitors!), including enough individuals with appropriate language skills, and giving them training and a proper budget? (The former could indicate the latter has been ignored, of course. Executive politicians come and go: institutions endure.) He could have inspected successful patterns for developing mechanisms for sharing intelligence across different groups of the armed forces, and encouraging objective assessment. He could have explored cases where intelligence personnel showed imagination in not assuming that the enemy worked and thought as themselves. Britain, in the Chamberlain era, ignored nearly all these rules, and it took Churchill to make amends, such as giving the Joint Intelligence Centre some real teeth and focus, but policy towards the Soviet Union in World War II was marred by the Foreign Office’s belief that, if handled nicely, Stalin would behave like a typical English gentleman, rather than the Georgian gangster he always was. Readers will learn much more about such matters from, say, Ralph Bennett’s Behind the Battle (a work not appearing in Andrew’s Bibliography, but one which he could profitably have read) than they will from The Secret World.

Andrew’s judgments are largely unsurprising and sometimes questionable, I think, and he steps back from exploring really important topical matters, such as the use of modern technology (e.g. encryption, social media) in both subversion and counter-subversion. Neither Apple nor Facebook appears in the Index. He offers a few pages on Islamic fundamentalism, but does not discuss the critical subject of taqiyya, Islamic propaganda with a devious religious spin, or recommend how it should be countered. He represents 9/11 as a failure to combine the preparation for a threat originating on foreign soil with delivery inside the nation’s boundaries, when the plotters were in fact able to pass undetected because of woeful lack of communication and collaboration by the country’s intelligence agencies. He comes up with a knee-jerk assessment of McCarthyism that contains all the fashionably correct codewords: “The outrageous exaggerations and inventions of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s self-serving anti-Communist witch-hunt in the early 1950s made liberal opinion skeptical for the remainder of the Cold War of the reality of the Soviet intelligence offensive”, as if McCarthy had been responsible for the concealment of communists undertaken by such as the State Department. If there was a ‘reality of the Soviet intelligence offensive’, how should it have been revealed when it had already succeeded in its infiltration? Why was ‘liberal opinion’ so appeasingly indulged? How would experience have helped? Andrew ventures no opinion. He spends an enormous amount of print on Pearl Harbor, but barely scrapes the surface of the Soviet Union’s Red Orchestra and spy network in World War II, and how it affected critical negotiations between the Big Three towards the end of the conflict.

What it boils down to is that repeated patterns of activity are not really that interesting, while integrating growing knowledge of intelligence into historiography is endlessly so. That is why rewriting WWII history in the light of revealed secrets about Ultra, for example, is an ongoing task: even histories written in the 1990s were not able to take advantage of the raw decrypts that have now been released to the National Archives. He mentions this in his Introduction, but does not follow through. Instead, in order to provide some linkage with the present, Andrew has chosen to develop some leitmotifs that are entertaining, though not always revelatory. It is worth quoting a few:

“Scot was the first, and so far the only, British intelligence chief executed for treason.” (p 231)

“Before he [James II] could escape, however, he was caught by fishermen looking for fleeing Catholic priests, and suffered the humiliation of becoming the only British monarch ever to be strip-searched.” (P 250)

“Wallis was the first, and so far the only, British codebreaker to receive an award from a foreign ruler.” (P 253)

“Among the most reluctant witnesses to give evidence in the Lords against Atterbury was Edward Willes, the only codebreaker ever to appear before Parliament.” (p 274)

“His [Swift’s] Gulliver’s Travels contains the first (and so far the only) satire of codebreaking by a major British writer.” (p 275)

“So far as is known, following the failure of the Cadoudal conspiracy [1804], no British government or government agency approved another plot to assassinate a foreign leader until the Second World War.” (P 338)

“The identity of ‘Michel’ was discovered from the handwriting and he became probably the only Russian spy ever to be sent to the guillotine.” (P 355)

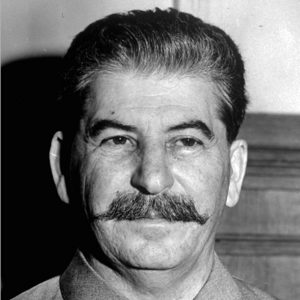

“After the Bolshevik Revolution, Stalin placed all the volumes in his personal archive and brooded over them for many years, making extensive annotations and occasional doodles. So far as is known, no other world leader has ever spent so much time brooding over the intelligence record of his past life.” (P 441)

“Apis and three fellow officers were shot by firing squad. He thus became the first intelligence chief [of Serbia] of the twentieth century to be executed.” (P 448)

“Thanks to the failure of the Cheka to provide security, Lenin became the first, and so far the only, head of government to be the victim of a carjack.” (P 574)

“He [Kalugin] became the first (and possibly the last) KGB officer to serve on the Columbia University Student Council.” (P 685)

Does this pattern represent a nervous tic, or does it show innovative scholarship? I leave the reader to decide. But it must be passages like this that prompted Ben Macintyre to assert, in an interview in the New York Times Book Review, that The Secret World is ‘easy to dip into’ and ‘surprisingly funny’. I did not laugh much – but then I was not dipping.

While this critic was sometimes overwhelmed by the panorama of historical figures, many of whom I had not encountered before, I must credit the tremendous scholarship that has gone into this publication. Did Andrew really compose it all himself? Can any single scholar have read all those works listed? He thanks dozens of academics in his Acknowledgements, many of whom ‘notably extended my grasp of intelligence by allowing me to supervise their PhD theses’. Yet those theses are not listed separately, and only four such writers (Gioe, Gustafson, Larsen and Lokhova, whose contribution is actually an MPhil dissertation) have their theses listed in the Bibliography. On the other hand I did notice references to Cambridge University theses by authors whose names do not appear in the Acknowledgments. Were projects delegated to different scholars? I ask simply because I do not know how the process worked, although I have read that Andrew, who said that his writing of Defend the Realm was for him a part-time occupation, did on that project have junior academics performing primary research for him in the MI5 archives.

Irrespective of how the project functioned, or whether everyone has received the credit due to them, any seams are overall well concealed, and Andrew’s copy-editor has performed a solid job in providing stylistic consistency. Some deep textual analysis might show multiple authors at work: I spotted ‘different to’ on page 346, and ‘different from’ on page 490, which would be an unusual syntactic habit by an established academic with a competency for polished prose. Occasionally, errors occur: repeated textual descriptions and references (even in the same chapter) come up quite regularly, suggesting a text that has undergone homogenization without complete cross-checking. An individual map appears twice. ‘Bagration’ (from the Index) appears as ‘Bagratian’ (in the text). Rear-Admiral Macintire appears as ‘Macintyre’ in the same line (p 633). Colonel House appears sometimes as ‘Colonel’ House, as if it were a nickname. (The author invites readers to contact him with notices of errors, but does not indicate how.)

As for sources, Andrew quotes his own works a little too much for my liking, and I found it bizarre that he, as the authorised historian of MI5, would cite Ben Macintyre’s Double Cross as a source. He stresses the importance of the American journalists Woodward and Bernstein, but fails to mention anything that Chapman Pincher wrote, or the contribution that Pincher made to drawing attention to murky secrets. On the other hand, Andrew is a bit too eager to mention his acolyte Svetlana Lokhova (see FourBooksonEspionage), who even gains credit for her entrepreneurship: “The investigation of the Kremlin plot, whose voluminous files have recently been discovered by Svetlana Lokhova, revealed a security shambles on an even larger scale.” It was not as if Ms. Lokhova had been tramping intrepidly through the Amazon jungle in search of a lost tribe: she would not have been able to ‘discover’ those voluminous files without some high-up permission and guidance. Yet Andrew has no room for Lokhova’s profile of Shumovsky, The Spy Who Changed History, which essentially glorified the Soviet Union’s purloining of American scientific secrets. Is Andrew suggesting that the lessons of HASDD be applied consistently by potential global adversaries? It is all rather uneven, and reflects very indeterminate principles.

In conclusion, I should have liked Andrew to explore this notion of HASDD in more detail, and how it relates to the defence of the constitutional democracies. After all, we should assume that his lessons are for the ‘good guys’ (the liberal democracies) rather than for the ‘bad guys’ (authoritarian or totalitarian states, or transnational terrorist organisations). Andrew does not make this explicit: he describes China’s efforts to erase any memories of Tiananmen Square, but does not offer us an opinion of whether this initiative to improve state security is commendable, or to be deplored. (Is a stable but authoritarian and expansive China better for the West than a China that starts to fragment or crumble?) Nor does he encompass the possibility, as we are frequently told these days, that the democracies may well be at risk more from the imitation of illiberal democracies, or from the sway of undemocratic superstates, than they are from ideological would-be territorial invaders, such as the Nazis and the Communists. That former warning is, presumably, the moral message he is leaving with us, rather than a sermon on how an inattention to historical precedent sometimes inhibits China’s new imperialism, or Iran’s regional ambitions.

Does this HASDD syndrome reflect a problem of structure, personnel, process, or skills? Is it the fault of the intelligence services, the politicians, (in Britain) the Joint Intelligence Committee, or some other agency? Is this a uniquely British/American condition? And, if he considers that the lore of successful spycraft is not properly understood and applied, why is he surprised, given that the security services (in the UK) were not admitted to exist until the 1990s, that the authorised history of SIS stops in 1949, that both MI5 and SIS have engaged in cover-ups to conceal their mistakes, and that they have selectively broken the Official Secrets Act by allowing journalists access to secret files in order to write publications that would act as public relations exercises? After all, the authorised histories avoid the really contentious issues that might provide learning examples for HASDD. It is no wonder that there exists a substantial amount of suspicion about the effectiveness of both institutions.

Coming closer to home (well, my spiritual home, I suppose, but I suspect I have more readers in the UK than in the USA), what needs to be done to improve British intelligence? In response to Andrew’s examples from more recent times, were the close links between Sir Richard Dearlove (head of SIS) and Anthony Blair that the author highlighted a sign of greater ministerial awareness, or of dangerous cronyism? Clement Attlee, as he points out, had frequent meetings with Percy Sillitoe, the head of MI5, but what Andrew does not say is that it did not help Attlee, since Sillitoe lied to his PM over the Fuchs case, in order to save the Service. How actively should the parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee monitor MI5? Shouldn’t there be a vigorous filter between intelligence collection and executive action – the JIC? Andrew supports the establishment of centres for study into intelligence and security matters, but are those who teach there going to be unrestrained by pledges of secrecy? Would research carried on under their auspices address the HASDD problem? And does each faculty then become part of that inescapable irritatingly-named entity ‘the intelligence community’? Is it good or bad that members of this group might have different views on intelligence matters? If it is indeed a ‘community’, should MI5 and SIS be combined, since the Empire no longer exists, and many threats to security do not recognize national boundaries? Do retired heads of MI5 and SIS, voicing their opinions on national security on public platforms, help or hinder the task of guiding policy? These are some of the questions that it would have been useful for Andrew to address.

And, as a final thought – perhaps intelligence is sometimes overrated. In life we learn that the predatory behavior of a bully is best resisted as early as possible, as the malefactor will otherwise assume that his aggression works for him, and will repeat it. At the time of Hitler’s militarization of the Rhineland in 1936, and Stalin’s claims for possession of the Baltic States in 1941, both bullies were relatively weak, and yet they were not challenged. Is it the same with President Xi, and his demands on Taiwan, and the construction of artificial islands in the China Sea? No furtive gathering of information was necessary to divine what was happening in either of the two historical instances, yet the fear of ‘provocation’ overrode the political conviction that what deters bullies best is a quick biff on the nose – or, at least, its diplomatic equivalent. And autocrats are more transparent in that they don’t have to avoid decisions that might lose them the next election (unlike Stanley Baldwin). We can perhaps get too caught up in the fog of intelligence, and forget some simple psychological lessons.

I suppose part of the problem in taking on a task of this magnitude is the truth that Andrew has become part of the official intelligence apparatus. That leads to a paradox – a Morton’s Fork. If Andrew is indeed that firmly embedded, it must be impossible for him to analyse objectively the infrastructure to which he belongs. Yet, if he were an outsider, he would not be privy to much of the knowledge of how the apparatus works, because it is so secret, although sometimes unnecessarily so. An insider knows too much, an outsider too little. Moreover, it is difficult to write a volume that serves as both objective history as well as a tutorial on intelligence and spycraft. The Secret World is thus a compromise: a monumental and educational undertaking of great academic quality, testimony to some impressive research, but lacking a clear charter, and failing to explore ruthlessly enough the patterns of failure and success in governments’ deployment of intelligence. There is a book to be written about that latter topic, but Andrew’s is not it.

(This month’s new Commonplace entries can be found here.)