Dramatis Personae 1963-1964

UK Government:

Alec Douglas-Home (Prime Minister since October 1963)

Rab Butler (Foreign Secretary)

Henry Brooke (Home Secretary)

John Hobson (Attorney-General)

Bernard Burrows (Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee)

Howard Caccia (Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office)

Burke Trend (Secretary to the Cabinet)

MI5:

Roger Hollis (Director-General)

Graham Mitchell (deputy to Hollis, retired in September 1963)

Martin Furnival-Jones (head of D Division, transferred to deputy to Hollis in September 1963)

Malcolm Cumming (head of D Division, replacing Furnival-Jones)

Arthur Martin (head of D1, ‘Investigations’, former henchman of Dick White)

Peter Wright (joined D1 in January 1964)

Ronnie Symonds (working for Martin, compiler of report on Mitchell)

MI6 (SIS):

Dick White (Chief since 1956; former head of MI5)

Maurice Oldfield (White’s representative in Washington)

The Spies:

Guy Burgess (absconded to the Soviet Union in 1951)

Donald Maclean (absconded to the Soviet Union in 1951)

Kim Philby (absconded to the Soviet Union in January 1963)

Anthony Blunt (strongly suspected of being Soviet spy)

John Cairncross (forced to leave the Treasury in 1952)

Leo Long (detected spying in 1944, but not prosecuted)

James Klugmann (open CP member, and ex-SOE officer)

Michael Straight (American recruited by Blunt in 1937)

In the USA:

Edgar Hoover (Chief of FBI)

William Sullivan (Hoover’s deputy)

James Angleton (Head of CIA Counter-Intelligence)

Anatoli Golitysn (KGB defector)

Contents

Introduction

The Official Account

Had Blunt confessed before?

The Sources: Wave 1 – Conflicting Rumours

The Sources: Wave 2 – Digging Deeper

The Sources: Wave 3 – The Era of Biography

The Sources: Wave 4 – The Archives Come Into Play

Introduction

When I set out on this project, I did not know whether it was important, or why it might be so. I did not even seriously believe that there could be significant doubts about the facts of Anthony Blunt’s confession. Yet I had a nagging suspicion that all was not right, and my impressions were that the official account was at loggerheads with other descriptions I had read. Thus, as my investigation continued, and I became more convinced that the official accounts were false, I asked myself: If the event had indeed been bogus (as Chapman Pincher suspected), why would Hollis and White go to such elaborate lengths to construct such a flimsy story, and why did they execute the misinformation exercise with such appalling clumsiness? The irony remains, however, that, despite the project’s ham-handedness, every historian, journalist and commentator has been taken in by what appears to be an absurdly clumsy attempt by Dick White, former head of MI5, and chief of MI6, to divert attention from his profound culpability over Anthony Blunt. This report lays out the historical evidence. Next month I shall interpret it all.

[Note: In my text, as a general rule, standard parentheses enclose natural asides. Square parentheses indicate editorial comment.]

The Official Account

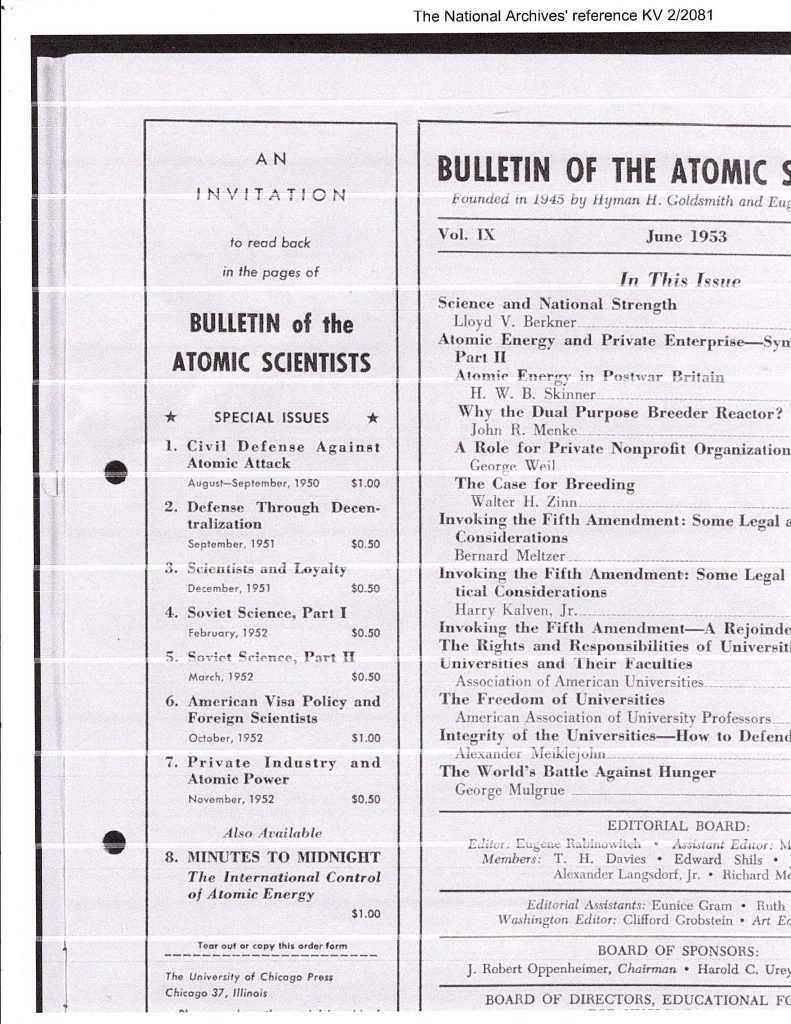

The anchor for the analysis of the confessions of Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross in early 1964 should probably be the account of the events by the authorised historian, Christopher Andrew, delivered in 2009. We should recall that MI5 had set out on its celebrated ‘Molehunt’ two years before the Blunt confrontation. In April 1962 the Soviet defector Anatoli Golitsyn had defected to the USA. On James Angleton’s invitation, Arthur Martin of MI5 had interviewed him, and Golitsyn later declared the existence of a ‘Ring of Five’ Cambridge spies. Burgess and Maclean were the obvious first two. Philby was not named, but was indirectly identified. The names of the last two were unknown. Philby, perhaps with MI6’s connivance, escaped from Beirut in January 1963. Cairncross and Blunt had apparently been interviewed by MI5 several times since the abscondence of Burgess and Maclean in 1951. Cairncross had been required to leave the Treasury in April 1952 when evidence of his espionage came to light.

The famous and much quoted passage in Defend the Realm runs as follows (pp 436-437):

“The decisive breakthrough in the Service’s investigation of Anthony Blunt came when the American Michael Straight admitted that Blunt had recruited him while he was an undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge. Arthur Martin called on Blunt at the Courtauld Institute on the evening of 23 April 1964 and asked him to recall all he knew about Michael Straight. Martin ‘noticed that by this time Blunt’s right cheek was twitching a good deal’ and ‘allowed a long pause before saying that Michael Straight’s account was rather different from his’. He then offered Blunt ‘an absolute assurance that no action would be taken against him if he now told the truth’:

He sat and looked at me for fully a minute without speaking. I said that his silence had already told me what I wanted to know. Would he now get the whole thing off his chest? I added that only a week or two ago I had been through a similar scene with John Cairncross who had finally confessed and afterwards thanked me for making him do so. Blunt’s answer was: ‘give me five minutes while I wrestle with my conscience.’ He went out of the room, got himself a drink, came back and stood at the tall window looking out on Portman Square. I gave him several minute of silence and then appealed him to get it off his chest. He came back to his chair and [confessed].”

Andrew sources this passage as ‘Security Services Archives’.

Now, I do not doubt that Professor Andrew did find a document containing this information, but it is bewildering that it has not been released by MI5 to the National Archives for perusal by objective historians. It is not unknown for inauthentic documents to be inserted into an archive in order to indicate that things were other than they actually were. For the melodramatic event poses all sorts of pertinent questions. Andrew’s vagueness about dates (including in a predecessor passage where he describes Cairncross’s confession to Martin in Cleveland, Ohio) provokes some major challenges: the circumstances of Martin’s approaches to Blunt raise a few more. For example:

Straight confessed to the FBI in June 1963. Why did it take so long to confront Blunt?

Why was Cairncross interrogated in Ohio, when he had recently passed through London?

What was Martin’s real business in the USA in January 1964?

What made Cairncross confess, just when he had taken up a new academic post in Ohio?

Why did Martin visit Blunt alone? This was not normal investigative practice.

Why did Martin state that Blunt’s account ‘was rather different from’ Straight’s, when Blunt had apparently not said anything at that time?

Why did Martin’s claim that Cairncross had confessed not have any discernible effect on Blunt?

Why were Blunt’s revelations about Cairncross such a big issue if Cairncross had already confessed?

Why did Martin say that Cairncross’s confession had occurred ‘only a week or two ago’, when it had happened over two months beforehand?

How did Martin and MI5 expect to be able to establish whether Blunt told them ‘the truth’ or not?

I shall attempt to answer those questions by peeling away the various records and interpretations of the event in books and archival material published since Andrew Boyle’s unveiling of ‘Maurice’ in 1979, and Margaret Thatcher’s subsequent admission in the House of Commons that Anthony Blunt had been given immunity. The story displays a kind of ‘Rashomon Effect’, although the testimony of the scribes is rarely that of eye-witnesses, and those closest to the action appear to have the most at stake in distorting the facts of what actually happened. Perhaps it should be seen as more of a detective-story, where a Hercule Poirot-like figure interviews all the participants in order to establish the truth.

But first, the claims about an earlier Blunt confession.

Had Blunt confessed before?

In one provocative paragraph in Climate of Treason, Andrew Boyle suggested that Blunt (‘Maurice’) had voluntarily approached MI5 to admit his connections with Burgess and Maclean. “Yet less than two years after the reappearance of Burgess and Maclean in Moscow [February 1956]”, he wrote, “‘Maurice’, the Fourth Man, belatedly called on the security authorities to confess all he knew about the past links between himself and his fellow conspirators.” Boyle went on to describe how Blunt gained the equivalent of a ‘Royal Pardon’ for disclosing what Blunt claimed was ‘a secondary role’ in the ‘nefarious exploits of Burgess, Maclean and, to a lesser degree, of Philby’.

Boyle offers no source for these assertions. And it is easy to grant this event (if it occurred) more substance than it merits. After all, Blunt apparently did not admit to grand espionage on his own account, but merely to abetting the real traitors. Moreover, such revelations would not have come as much of a surprise to Dick White and Roger Hollis (who had succeeded White as head of MI5 on the former’s transfer to MI6 chief in 1956), since Blunt’s behaviour at the time of the abscondence of Burgess and Maclean had been well-noted, and Blunt’s collaboration with Leo Long at MI14 in 1944 was still fresh in their minds. 1958 seems rather early in the cycle, yet, if Blunt was anxious to get his account out before Burgess spoke up and distorted the story (in Boyle’s thinking), one might have assumed that Blunt would have spoken up even earlier.

Other writers, however, have brought up stories in a similar vein. In her 2001 biography of Blunt, Anthony Blunt: his lives, Miranda Carter reports a claim made by Michael Taylor, an undergraduate at the Courtauld in the early sixties (pp 438-439). In a letter to Carter of February 8, 1996, Taylor had written:

I knew MI5 had offered him immunity if he would confess, that he had got up, walked over and poured himself a drink and gone over and gazed out of the window for a while before turning around and admitting he was a spy. I knew he had been questioned a number of times over the years and had proved too clever to be trapped. And I knew that the car of the last of the three had been finally located in the carpark of the Courtauld Institute galleries . . . To me this was common knowledge and it was told to me by a fellow undergraduate in 1961 (or perhaps 1962).

This anecdote may betray a confusion of memories: how would Taylor have known of the drink-pouring incident? He may have recollected it from another account, as I shall show later. Carter goes on to claim that Blunt’s guilt was ‘canteen gossip at MI5’ in the early 1960s. She shows that there were frequent declarations made among the denizens of the art world that their resident expert on Poussin had been a Soviet spy. Yet all these denunciations could be indicative only that senior officers at MI5 believed that Blunt was a spy, and were happy to have their suspicions broadcast. They do not necessarily point to the fact that Blunt had made a confession, and agreed to some form of an immunity deal.

Carter also identifies the story in Private Eye, in the issue of 28 September 1979 (i.e. before Blunt was officially unmasked) that named Blunt as the interested party, after a leak from the practices of Blunt’s lawyer, Michael Rubinstein. One of the statements that the magazine made was that Blunt ‘had confessed in 1957’.

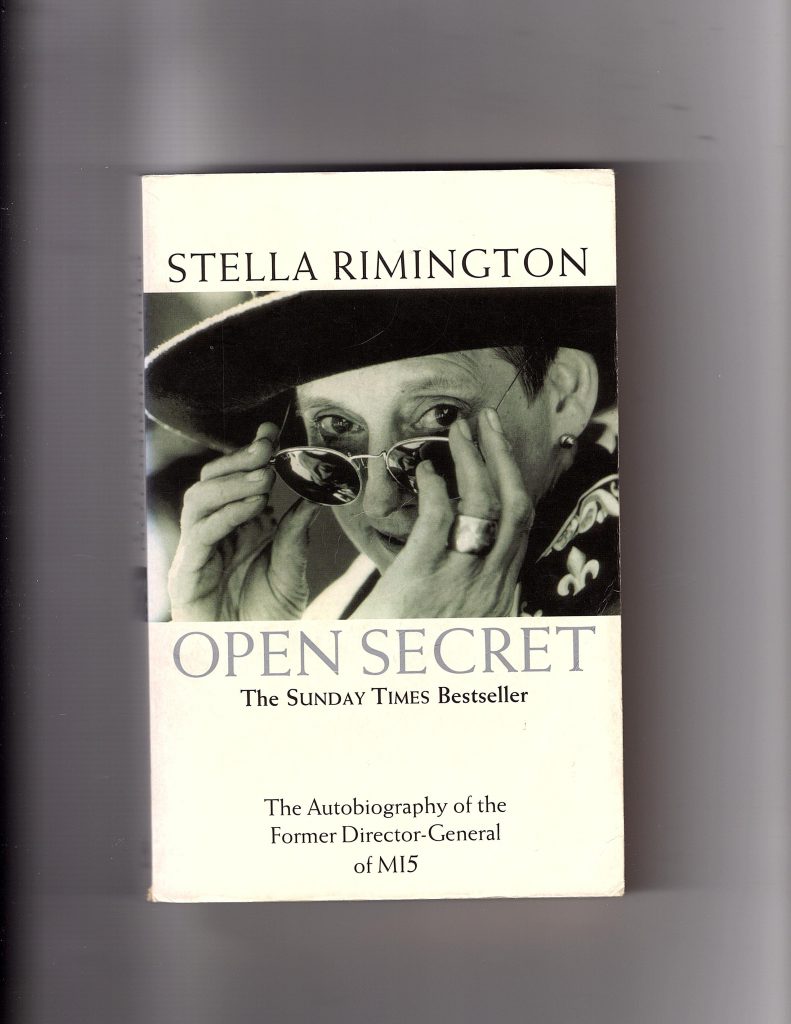

Other indications of an earlier confession have surfaced. In his 2019 biography of John Cairncross, The Last Cambridge Spy, Chris Smith informs us (p 154) that Dame Stella Rimington (Director-General of MI5 from 1992 to 1996), when a junior officer, had interviewed Cairncross in 1973, and noted that he had claimed that Blunt was MI5’s source on Cairncross’s guilt. Was she perhaps just parroting what Cairncross said? Indeed, in Cairncross’s memoir The Enigma Spy (p 141) the author declared, in describing Martin’s arrival in Cleveland, Ohio, and the subsequent interview, that ‘his informant was again Anthony Blunt, the man who had organized my recruitment without appearing on the scene himself.’ Moreover, in Open Secret, her 2001 memoir, Dame Stella appears to make a far more authoritative declaration (p 119): “He [Cairncross] had been exposed as a spy for the KGB by Anthony Blunt, and had been interviewed by, amongst others, Peter Wright, to whom he had made some limited admissions.” In other words, Blunt confessed before Cairncross.

It must be daunting for any biographer new to this sphere to sort out such conflicts. Thus, instead of analyzing this valuable item of evidence from a highly authoritative source, and considering its implications, Smith has to resort to trusting ‘the archival evidence’ (which of course he has not seen, as it has not been shown to any writer except Christopher Andrew). “Yet, the archival evidence conclusively shows that Martin had interviewed Cairncross by 18 February 1964. They cannot have been interested in Cairncross because Blunt tipped them off”, Smith writes. The evidence is, however, not conclusive at all. So what does a researcher do: accept the judgment of the authorised historian that an authentic and reliable document exists, or trust the word of a director-general of MI5, who was there at a critical interview? Of course, you must do neither. You have to accept that there is a conflict, and dig more deeply yourself.

My method here is thus to study in depth the publications that cover the Cairncross-Blunt confessions, to determine what source material they relied upon, and thus to attempt to establish how some of the mythology took hold. Next month I shall propose what a more likely explanation of events might be. This study may be very laborious for some: for true aficionados I hope (and believe) that it will be as compelling to read as it has been for me to compile it. I know no other way of dismantling the scaffolding of untruths that has concealed the structure behind it.

The Sources: Wave 1 – Conflicting Rumours

The Prime Minister’s Statement to the House of Commons: November 21, 1979 (extract)

“The defection of Burgess and Maclean led to intense and prolonged investigations of the extent to which the security and other public services had been infiltrated by Russian intelligence.

At an early stage in these investigations Professor Blunt came under inquiry. This was as a result of information to the effect that Burgess had been heard in 1937 to say that he was working for a secret branch of the Comintern and that Blunt was one of his sources. Blunt denied this. Nevertheless, he remained under suspicion, and became the subject of intensive investigation. He was interviewed on 11 occasions over the following eight years. He persisted in his denial, and no evidence against him was obtained. Of course, until his confession, the authorities did not know the extent of his involvement with the Russians or the period over which it lasted.

It was early in 1964 that new information was received relating to an earlier period which directly implicated Blunt. I cannot disclose the nature of that information but it was not usable as evidence on which to base a prosecution. In this situation, the security authorities were faced with a difficult choice. They could have decided to wait in the hope that further information which could be used as a basis for prosecuting Blunt would, in due course, be discovered. But the security authorities had already pursued their inquiries for nearly 13 years without obtaining firm evidence against Blunt.

There was no reason to expect or hope that a further wait would be likely to yield evidence of a kind which had eluded them so far. Alternatively, they could have confronted Professor Blunt with the new information to see if it would break his denial. But Blunt had persisted in his denial at 11 interviews; the security authorities had no reason to suppose that he would do otherwise at a twelfth. If the security authorities had confronted him with the new information, and he still persisted in his denial, their investigation of him would have been no further forward and they might have prejudiced their own position by alerting him to information which he could then use to warn others.

They therefore decided to ask the Attorney-General, through the acting Director of Public Prosecutions, to authorise them to offer Blunt immunity from prosecution, if he both confessed and agreed to co-operate in their further investigations.”

The Fourth Man by Douglas Sutherland (1980)

Quick off the press after Boyle was Douglas Sutherland, who had written a book with Anthony Purdy titled Burgess and Maclean in 1963, and now felt encouraged to make more explicit what he had hinted at earlier. The Fourth Man is a paradoxical work, since it starts out by criticizing MI5 and other government agencies for being in their employment practices too tolerant of Burgess, Maclean, Philby and Blunt, but concludes that it did not really matter, since they all achieved very little in the line of espionage, and that Cairncross was an unfortunate victim of spy fever. Of course, these latter assumptions were all made in ignorance of the secrets later revealed in the Moscow archives.

His coverage is relevant for this discussion of the challenge he threw down to Blunt in 1962. He writes (p 18): “In 1963, when Anthony Purdy and I published our book Burgess and Maclean, we had known with complete certainty that the shadowy figure now known in the popular numbers game as ‘The Fourth Man’ was Sir Anthony Blunt.” Sutherland thus invited Blunt to a meeting at the Travellers’ Club, and confronted him, listing the reasons he thought he was implicated. Blunt was visibly shocked, but Sutherland spoiled his opportunity by making a weak claim that allowed Blunt to wriggle free. “Unfortunately I did not realize at the time just how the last minute tipoff to Maclean had been contrived and wrongly accused Blunt of using his MI5 contacts to tell Maclean on Friday that he was to be interrogated on the Monday after his flight. This, it now emerges, was not the case. My inadvertent disclosure that my information was not entirely accurate seemed to rally Blunt. He stopped shaking and mumbling, told me in a comparatively firm voice that I would hear from his solicitors immediately if his name appeared anywhere in connection with the case, and beat a hasty retreat.”

Sutherland used this experience, however, to suggest that Blunt, over the eleven interrogations that the Prime Minister stated had occurred, could well have been broken, and he also expressed his belief that MI5 might have brought Blunt in from the cold and asked for his cooperation. Thus Sutherland is another who doubted the solemn implications of a stagey April 1964 melodrama, and, in his own style, he anticipated the Stella Rimington story. Yet he showed his own inconsistencies. On page 162, he claimed that Blunt held back on what he admitted because of the demands of the Official Secrets Act, and on the next, indicated that Blunt made a ‘full confession’ in 1964. He overlooked the obvious irony.

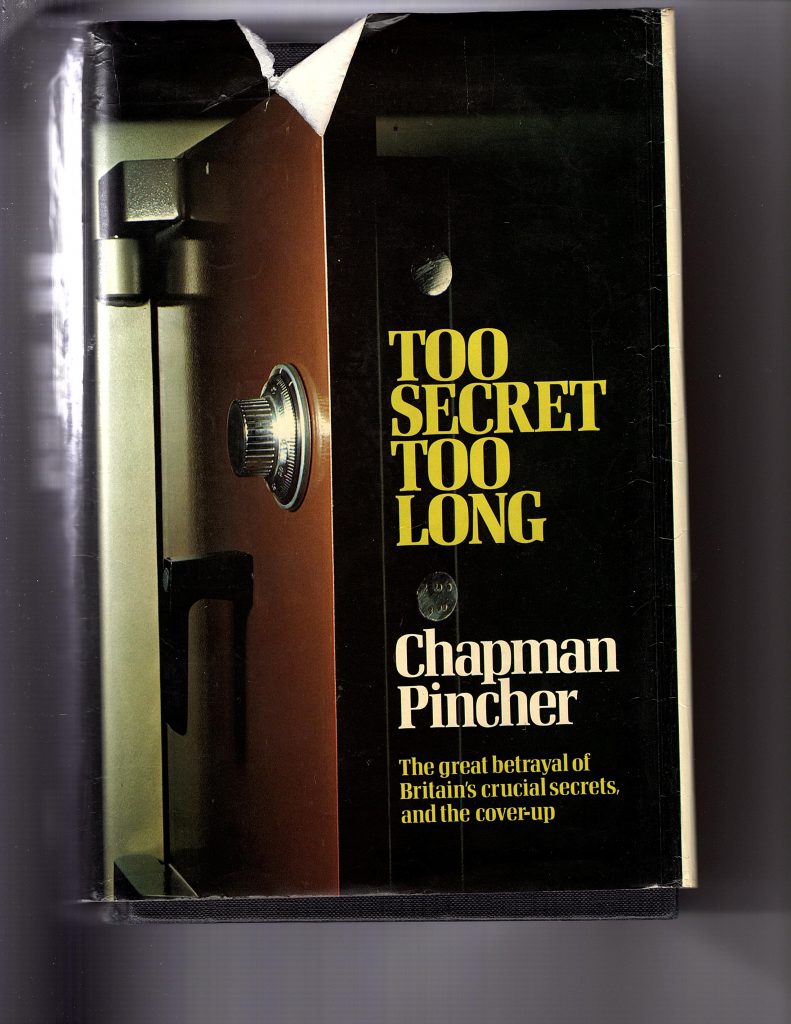

Their Trade is Treachery by Chapman Pincher (1981: paperback version 1982)

When Pincher issued the first edition of Their Trade is Treachery, he was prevented, on legal advice, from naming some of the figures in the drama, such as Michael Straight, Leo Long, and Jack Jones, and instead had to deploy vague coded language. Straight, for instance, was described as ’a middle-aged American belonging to a rich and famous family’. But by the time the paperback version was published the following year, Straight had been flushed out by an enterprising journalist (Pincher), and admitted his role. In this revised edition, Pincher described how he had been able to interview Straight: he and Straight became close friends, and met several times before the paperback version was published. Pincher was free to name names.

Peter Wright was the source for the story. He had been introduced to Pincher by Victor Rothschild, and was seeking monetary reward to compensate for the fact of his pitiful £2000-a-year pension. Pincher had travelled to Australia to see Wright, and had made detailed notes from his conversations with him in Tasmania and from his inspection of the chapters that Wright had written. (Wright would not hand over his manuscript.) In his 2014 autobiography, Dangerous To Know, Pincher said he wrote the book in four months on his return to England. And sometimes it shows.

Pincher’s account runs as follows: Straight was asked by President Kennedy, late in 1963, shortly before he was assassinated, to be chairman of the National Council for the Arts. Concerned about what a security check might bring up, Straight met with the FBI, and admitted that he had been recruited in Cambridge by Blunt,’ whom he knew to have been a Soviet agent’, and was willing to give evidence against Blunt, if necessary. The FBI gave the news to MI5, and senior MI5 officers ‘discussed the situation for several weeks before taking any action’. Pincher continued by making a rather brazen observation: “It was agreed inside MI5 that the main purpose of confronting Blunt with the evidence was to induce him to talk in the hope that he would give a lead to the still unknown Fifth Man, to others he and his friends might have recruited, and to the identities and methods of the Soviet intelligence officers who had been involved.”

It was (according to Pincher) Arthur Martin who came up with the idea of offering Blunt immunity, and the Attorney-General approved the idea. After an intense discussion in April, Martin was chosen to interview Blunt in his flat. When the testimony from Straight was described to him, Blunt denied it, but, after Martin, in a huge bluff, indicated there was further evidence, and then made the offer of immunity, Blunt poured himself a stiff gin, and confessed that he had been a long-serving KGB agent. No written confession was made. Hollis suspended Martin almost immediately after the confession, an indication, in Pincher’s mind, that Hollis was himself a Soviet agent.

I see several problems with this account. The first is the date given for Kennedy’s offer of a job to Straight. Working backwards, Pincher must have assumed that it occurred just before Kennedy was killed, as the news would surely have been passed quickly to MI5. Moreover, Pincher claimed to have interviewed Straight. As Straight’s testimony, and the FBI files show [to be analyzed in this piece later], the events happened in June 1963. Why did Straight not make this clear? Thus the ‘several weeks’ for which MI5 sat on the information are highly problematical. And the fact that MI5 decided to interrogate Blunt in order to determine who the ‘Fifth Man’ was fairly comprehensively suggests that the Security Service had already concluded that Blunt was the ‘Fourth Man’. Had this realization happened before the Straight incident? Moreover, the description of the interrogation departs from the version appearing in the Authorised History. There is no mention of the recent interrogation of Cairncross, or of the way that the latter’s confession was used as an opening to encourage Blunt to do the same. And it is highly unlikely that Martin, an avid molehunter, would have been the person who came up with the idea of offering Blunt immunity. Martin was head of D1 at the time, a relatively low-level officer in the hierarchy.

It is difficult to pin down why this account was so sloppy – especially as Straight had been interviewed. Did Straight dissemble? Did the interview even take place? Was Wright simply confused, as he had not been close enough to the action? Or had Pincher made a number of transcription errors during his time in Tasmania? Some of these issues would get reconstructed in the coming years.

MI5: British Security Service Operations 1909-1945 by Nigel West (1981)

The first instalment of Nigel West’s history of MI5 presents some historiographical problems. The project fell into West’s lap because of Dick White’s annoyance that Prime Minister Thatcher had cancelled the publication of Volume 4 of the British Intelligence in the Second World War series. Drawing on a conversation he had with Sir Michael Howard, White’s biographer, Tom Bower, described White as being ‘furious’ about her veto, and went on to write: “ . . .White encouraged a new writer, Rupert Allason, alias Nigel West, to write the history of MI5 up to 1945. With his assistance, West would be introduced to Tar Robertson and the MI5 officers who had rune the double-cross operation.” White was also upset that John Masterman (of Double-Cross fame) had been gaining all the glory.

West rather disingenuously recorded White’s contribution in his Introduction to MI5, where he wrote: “When I began my research I was told by a former Director-General of the Security Service that the task was virtually impossible, especially for an outsider.” Since three of the four previous DGs with deep knowledge of the period in question were deceased (Petrie, 1961; Sillitoe, 1962; and Hollis, 1973), the finger was pointed fairly squarely at Dick White. And West became an insider.

MI5 was first published in 1981, hard on the heels of Their Trade Is Treachery, and its ambit is clearly up to the end of World War II. Yet, at some stage, West added a Postscript that refers to Pincher’s book, and searches on West’s text suggests that the Postscript was added as early as 1982. It shows enough knowledge to indicate the role of Michael Straight, but is vague enough on the details to indicate that his precise testimony had not been examined. In his Postscript, West refers to Chapman Pincher’s Their Trade is Treachery, stating that it ‘caused such a furore early in 1981’, a choice of phrase that suggests it was a recent year, and not the same year in which MI5 originally appeared.

The story West tells is rather odd. Unfortunately, he displays a haphazard and imprecise approach to chronology. Cairncross is introduced into the story before the Straight incident. Without providing any context or timing, or explanation of what made Cairncross suddenly change his tune, West blandly declares: “Cairncross underwent a further interview in the United States, where he was lecturing, and made a full statement on his role as a Soviet agent. Although he was able to fill in a number of gaps about Burgess, he was unaware of Blunt’s talent-spotting and thus failed to name Blunt as a suspect. Cairncross wisely decided not to return to England and went to live in Rome when the American Department of Immigration declined to renew his visa.” But was this interview further to one he had submitted to recently, or further to his confession of 1952?

The temporal flow of West’s account suggests that the Cairncross confession occurred before Straight’s admissions to the FBI. West offers no date apart from ‘1963’ for the episodes involving Straight, and the passing on of Straight’s information to Hollis. Likewise, the sequence of events concerning the formal immunity from prosecution, and Blunt’s agreement to co-operate, is undated. West was probably uncomfortable with Pincher’s description of events, but was fed another leaky story by White and his cohorts, and was not ready to try and synthesize from all these half-baked stories exactly what happened, when.

MI5: 1945-72, A Matter of Trust by Nigel West (1982)

Soon after the publication of MI5 came Nigel West’s second instalment, not without controversy. On October 12, 1982, Her Majesty’s Attorney-General, Sir Michael Havers, QC, MP, successfully applied to Mr Justice Russell for an injunction against publication, as West’s work contained much secret information, including names of MI5 officers. After some negotiation, and the removal of some fairly innocuous names in organisation charts, the Court Order was discharged, and the book was published in November of that year.

MI5:1945-72 went through several impressions in the 1980s (my paperback copy is from the sixth impression in 1987), so it is not easy to determine whether subtle changes were made in the text concerning Cairncross and Blunt. In his Introduction, West volunteered the information that the Stephen Ward case had caused some major revisions, while making the claim that ‘this final version of A Matter of Trust is the most detailed account of MI5’s work ever published, or ever likely to be.’ Well, West could probably not imagine an authorised history coming out in 2009: his work held the stage for over twenty-five years.

In any case, it does not appear that A Matter of Trust took advantage of other works published during the mid-1980s. In fact, West’s account is singularly obtuse over the 1963-64 events. He identifies the trigger for the interrogation of Cairncross, after Blunt had repeatedly declined to co-operate, with D Branch’s decision to ‘retrace their steps’ and arrange an interview with Cairncross, ‘who was then lecturing at the University of the North-West in Cleveland, Ohio.’

Accordingly, Martin flew to Cleveland late in March 1964 ‘to talk over the situation with Cairncross’. [We know now that those dates are false.] For some reason, ‘the years abroad had mellowed him and he appeared ready to admit his espionage for the Russians.’ [The mellowing had presumably taken place in Pakistan or Italy, not the USA, as Cairncross had only just arrived in his post there.] West does not attempt to analyze why Cairncross would suddenly jeopardise his new career by owning up to something for which there was no fresh evidence.

West’s informer was no doubt Arthur Martin: no written record of Cairncross’s ‘confession’ has come to light. Cairncross was apparently able to reveal how he had been recruited by Guy Burgess in 1935, and he confirmed the awkward situation in 1951, when MI5 had tried to set him up with a rendezvous with his handler, Yuri Modin, during which only the Soviet officer’s quick-wittedness prevented a compromising meeting. Satisfied with his meeting with Cairncross, Martin prepared to return to London, travelling through Washington, where he was surprised to find that his opposite number in the FBI, William C. Sullivan, had some news for him. (Sullivan was assuredly not Martin’s ‘opposite number’.) He was told that Sullivan’s boss, Edgar Hoover (whom Sullivan loathed) ‘knew all about the communist cells at Cambridge because the FBI had its own special source on the subject’. That source was, of course, Michael Straight, and Martin had a meeting with him the following day. The story again came out: Hoover, apparently, had not trusted MI5 with the information. The given interval, however, between the end of March, for Straight’s revelations, and the date of Blunt’s confession [as we now know, dated on April 22] seriously belies Pincher’s assertion that MI5 officers ‘discussed the situation for several weeks before taking any action’.

Martin reportedly flew promptly back to London [an event we now know not to be true], and informed his boss, the head of D Division, Martin Furnival-Jones. West collapses the events concerning the agreement, and Martin’s interview with Blunt, into a few short sentences. Blunt took only a few seconds to consider the promise of immunity from prosecution, and then admitted that he had been recruited in 1936. Later, he admitted talent-spotting for Burgess, and recruiting Cairncross, which went rather against the grain of Cairncross’s claim that he had been recruited in 1935, as well as West’s assertion in MI5 that Cairncross was not aware of Blunt’s activities as a talent-spotter, and denial that he had been effectively recruited by him. The overall conclusion from this account, however, is that Arthur Martin was a professional liar who could not even construct a solid legend about his activities.

West does add some commentary on Martin’s subsequent suspension by Hollis, although his description of the conflict is undermined by his listing of Malcolm Cumming as Martin’s boss of D Division, since the organization charts provided by West show that Furnival Jones held that position until Hollis’s retirement in 1965. If indeed Cumming had been appointed head of D Division, Martin might well have resented it. [I shall cover this later.] In explaining Martin’s suspension, however, West strongly counters Pincher’s assertion that Hollis was the prime mover behind the act. He states that the decision was made by the Security Service Directorate (i.e. the six Directors alongside the DG and the Deputy DG). Lastly, West adds the laconic but portentous sidenote: “In his [Martin’s] absence, Peter W. took over Blunt’s debriefing.”

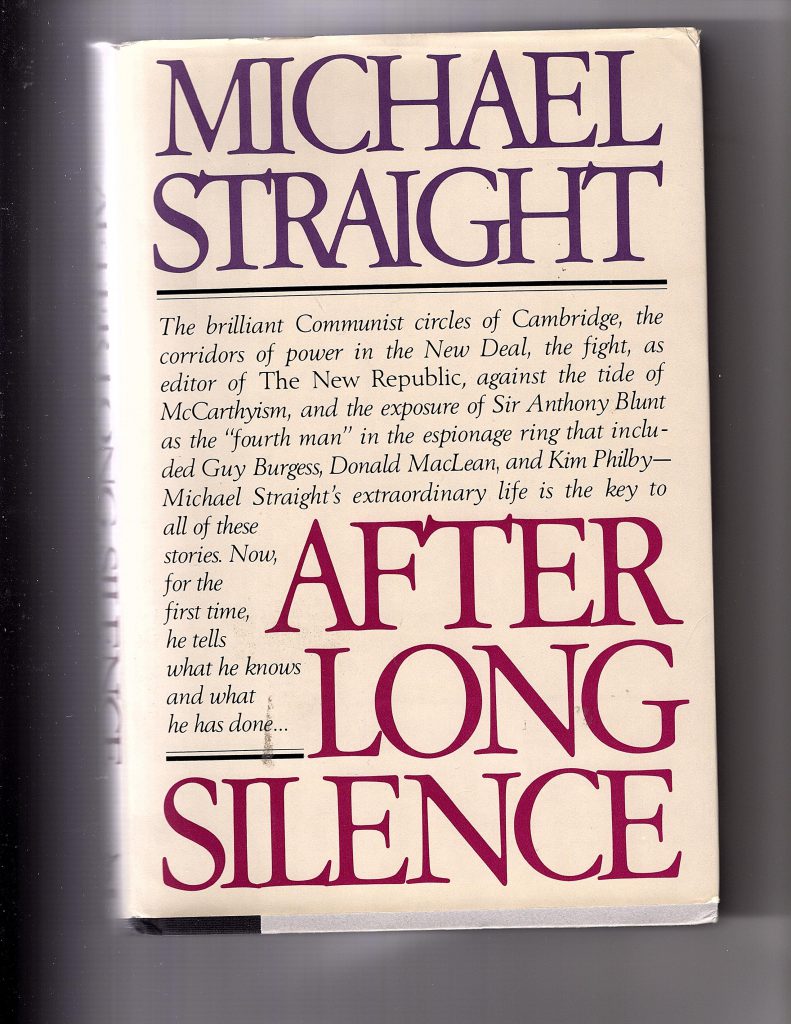

After Long Silence by Michael Straight (1983)

The last book from this exploratory period is Michael Straight’s own confessional work, which laid out for the public to read the whole saga of his recruitment as a Comintern spy in Cambridge. He describes how Blunt, about two weeks after the news of the death of Straight’s hero and friend, John Cornford, in Spain had reached the colleges of Cambridge (mid-January 1937), explained that ‘their friends’ had plans for him. By exploiting Cornford’s sacrifice, Blunt persuaded Straight that he could not turn down his assignment to move back to the USA and work on Wall Street, providing economic appraisals ‘of Wall Street’s plans to dominate the world economy’. Straight’s obvious distress at Cornford’s death would form a first-class cover for his breaking away from Cambridge.

Straight then covers his not very subversive career in espionage until June 1963, when he was invited to the White House to see Arthur Schlesinger, who showed him J. F. Kennedy’s plans for creating an Advisory Council on the Arts. Straight’s membership of that body would not have been problematic, but when he was recommended as chairman of the administrative arm of the new agency, the National Endowment of the Arts, he had to reconsider. Prior to his appointment, Straight would have to undergo an F.B.I. check. He decided he could not risk it. He told Schlesinger the whole story, and was set up with an interview with William Sullivan, the deputy director of the F.B.I. He told his whole story again.

In July, Sullivan asked Straight if he would repeat his story to the British intelligence authorities, and he willingly agreed to do so. For some reason, however, he was not called again until January 1964. Straight attributed this lack of exchange of information to the distrust and suspicion that lingered with the F.B.I after the Burgess/Maclean fiasco of 1951. Nevertheless, Sullivan called Straight in January 1964, saying that a friend of his was flying in from London. It was, of course, Arthur Martin, and he had a long discussion with the MI5 officer. He told Martin that he believed that Burgess had been behind the plot to send him back to America. He said he thought Leo Long had been brought into the network as well. Martin was elated at the breakthrough, and asked Straight if he would be prepared to confront Blunt if the latter declined to confess. Straight said he would, and the two parted.

Straight does not describe any other events of 1964 until he flew to London in September to be with his mother. Martin debriefed him, explaining that Blunt had confessed (though why Straight could not have been informed of this before is not analysed). “He had, in the course of many interrogations, named his Russian and his British colleagues; he had described the material that he had turned over to the Soviet government; he had provided the intelligence services with a great deal of information.” Yet Straight appears incurious about Blunt’s fate. He has a long chat with Blunt, who appeared to bear no grudges. Straight forgot most of what they discussed, but added that ‘the question of immunity from prosecution was never mentioned”. One might imagine that a person in Straight’s position would have shown greater interest in why a confessed spy was apparently being allowed to survive unscathed and unprosecuted.

This memoir adds some valuable facts that are probably reliable: the confession in June, the role of Sullivan, the meeting with Martin in January 1964 [which will be confirmed later in the course of historiography]. But it thus sheds a lot of doubt on the testimony of Martin himself, when telling West that he did not meet Straight until the end of March, on his way back from Cleveland, and it raises some thorny questions about the six-month hiatus when the FBI and MI5 apparently never discussed Straight’s extraordinary testimony.

* * * * * * *

Thus the first wave concludes with some conflicts in dates, as well as in evidence. How much of this was due to misunderstanding or mistranscription, and how much to forgetfulness or even active disinformation?

The Sources: Wave 2 – Digging Deeper

Too Secret Too Long by Chapman Pincher (1983)

Chapman Pincher was first to return to the fray, with a weightier volume, Too Secret Too Long, published in 1983. The publication of Their Trade Is Treachery had resulted in a groundswell of communications to the author from around the world, and Pincher exploited his many contacts in government and the civil service to flesh out his story. He contacted Michael Straight, and befriended him, and Straight in turn showed him his communications with Arthur Martin. Pincher harvested many useful items from Parliamentary proceedings, published in Hansard. Some of his information sources, however, had to be masked as ‘Confidential’, indicating that certain civil servants knew they were betraying secret information. He was able to access F.B.I. papers on the Straight confessions. And he started to construct a more rigorous chronology of events, while neglecting to follow it up in a truly disciplined manner.

The first major breakthrough that Pincher brought to the table was an illumination of the movements of the key players in 1963. He shows how Blunt was himself in the USA, at Pennsylvania University [sic], while Straight’s debriefing was being completed in August of that year. He points out that Roger Hollis had been in Washington in September, in an attempt to explain to Edgar Hoover of the F.B.I. the rationale behind the inquiry into Hollis’s deputy, Graham Mitchell, and that Arthur Martin followed close behind. He states that John Minnick, the legal attaché at the U.S. Embassy in London (and also the resident F.B.I. officer) delivered a letter from Hoover carrying the Straight-Blunt information – but only in November 1963. Pincher correctly draws attention to this astonishing delay, and surmises that Hollis did perhaps get briefed by Hoover in September, but decided to keep the information to himself.

Yet Pincher then breaks down in his own details. He goes on to write: “Whatever the extent and reasons for the long-time gap, Hollis decide to introduce a further delay. He allotted the case to Arthur Martin who was already in Washington pursuing the Mitchell inquiries and could easily have seen the F.B.I. about Blunt. Hollis, however, told Martin nothing, insisting that he must first return to London for discussions before either the F.B.I. or Straight could be approached.” This analysis is illogical, and in contradiction of Pincher’s own facts. If Hollis had truly been trying to keep things quiet, the last thing he would want to do would be to let loose an officer with a reputation for skulduggery in Washington, digging up secrets. There were no ‘Mitchell inquiries’ to be pursued in Washington. Moreover, this sequence of events flies completely in the face of what Straight had published in After Long Silence, where Martin in early 1964 was flown out to the U.S.A. on a mission (to interrogate Cairncross, as other accounts would soon confirm), and had a surprise encounter with Straight engineered by Hoover’s deputy, Sullivan.

But then Pincher corrects himself. He uses the Straight-Martin correspondence to show that Martin was not permitted to see Straight until early January, 1964, and cites Martin (who ‘recalled the situation to an informant recently’) as confirming that he had not been told about Blunt in the November time-frame, and that it was Sullivan who approached him about it when he was in Washington ‘for another purpose’. Pincher writes; ‘He seems to believe that the information he then received from Straight, in January 1964, was the first that MI5 had ever heard about it, implying that the F.B.I. had delayed for almost eight months before sharing its knowledge. This does not accord with my information from other MI5 sources.” Pincher then posits an arrangement between Hoover and Hollis (who apparently got on well) to set up the Straight-Martin meeting, so that Martin could return in triumph, and cover Hollis’s clandestine knowledge since November. But what would Hollis have hoped to gain through that intrigue?

The main thrust of Pincher’s case is, however, that Blunt’s confession was essentially bogus. [Chapter 37 of his book should be re-inspected by those readers who need to see his full analysis.] Pincher considers that Blunt must have been pre-warned about the proposed immunity offer: there was no planning for the eventuality that Blunt would not confess; the meeting did not take long; Blunt capitulated too soon; Martin never outlined to Blunt the conditions agreed on for the deal itself; there was no written record of the event; Martin tape-recorded it, and asked Blunt to agree to the proceedings, but Blunt knew that it could have no status in law. Moreover, Pincher now states (in contradiction of what he claimed in Their Trade Is Treachery) that Martin made no attempt to bluff Blunt. “The circumstances of Blunt’s confrontation by Martin would be rejected by an author of spy fiction as too wildly improbable a scenario”, was how Pincher summed it up.

Pincher’s natural instinct is by now to blame Hollis for everything. In this assessment he completely ignores any role for Dick White, but I think that is a gross oversight. Hollis and White were surely in the plot together. White had ensured that Hollis succeeded him as D-G of MI5, and White had far much more to lose than Hollis did, given White’s leading part in MI5 when Blunt had been recruited, his treachery later discovered and then condoned, and then his advice sought in the Philby affair. Martin had been White’s henchman in the 1950 business to mislead the F.B.I and the C.I.A. (see Dick White’s Devilish Plot), and it is possible that the strife immediately after the Blunt engagement of April 1964, whereafter Martin joined his former boss in MI6, was a ruse to isolate Hollis.

There are two further gems in Pincher’s account. He informs us that Straight visited London in September 1964 and with Hollis’s assent confronted Blunt, ‘having been ignored by MI5 during a visit in the previous November’ [my italics]. I believe this is sensational. Pincher cites ‘Letters from Michael Straight’ as his source. Yet Straight had carefully elided over any intermediate visits to Britain – and possibly to Blunt – in After Long Silence. Why? Was he now trying to provide a hint to Pincher? As will be shown later, Straight’s biographer added some flesh to this particular journey. Yet Pincher’s reinforcement of his hints from MI5 insiders that the FBI had contacted MI5 earlier in the cycle is important.

The last revelation is Pincher’s treatment of Cairncross, in Chapter 40. He goes over the now familiar story of Cairncross’s career and partial confession in 1952, and stresses that one of the first fellow-spies whom Blunt named was Cairncross, that he had talent-spotted him, and arranged for him to be recruited by James Klugmann. Next, however, as part of the prevailing doctrine that Cairncross’s confession followed that of Blunt, Pincher writes: “MI5 had no option but to take some action and in 1964 Martin travelled to Rome to interrogate Cairncross who could, of course, have simply refused to be interviewed.” Cairncross apparently made a full confession to Martin.

As we know now, this is hogwash. And Pincher should have realised that a massive disinformation campaign was under way, as Nigel West had written in 1982 about Martin’s interrogation of Cairncross in Cleveland earlier in the year, before the date of Blunt’s reported confession. Martin was feeding stories to West and Pincher, but tripping over himself by not getting a watertight story together first. Pincher then absolved him by stumbling over his own details, and focusing exclusively on Hollis. He spotted that the Blunt confession was a sham, but was not imaginative enough to propose an alternative scenario. Martin was turning out to be a liar, and not a very good one. Enough evidence was around in 1983 to explode the whole façade that Hollis and White had been constructing.

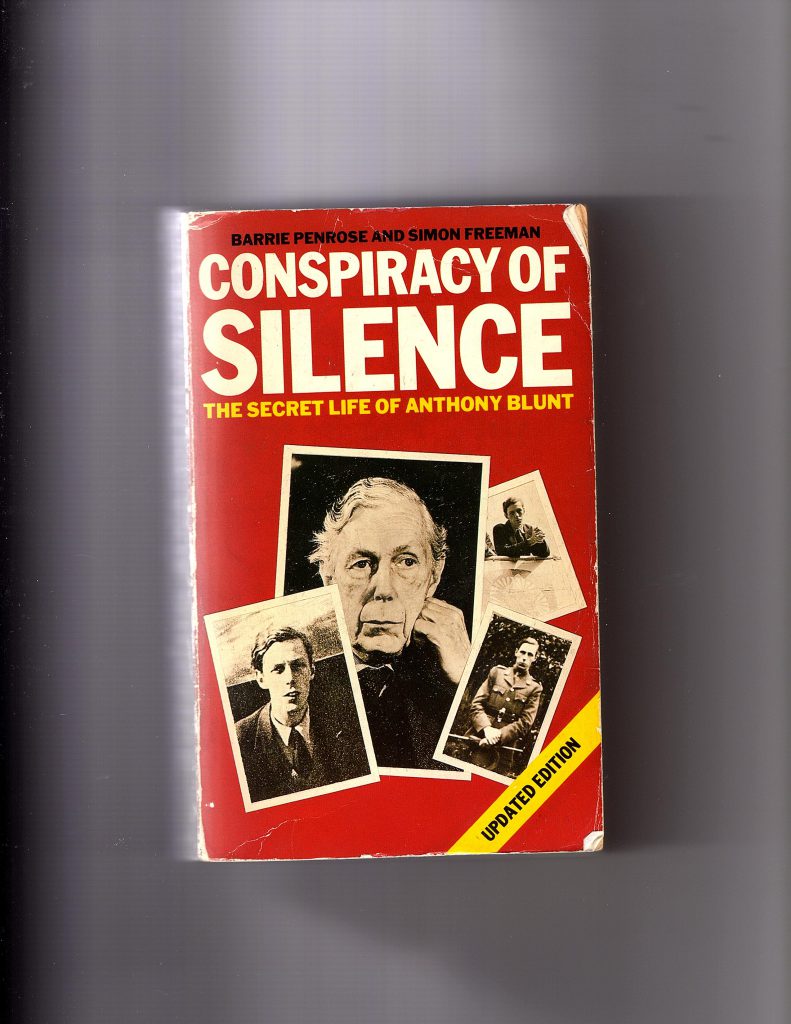

Conspiracy of Silence by Barrie Penrose and Simon Freeman (1986)

The hardback version of Conspiracy of Silence came out in 1986: energized by the Spycatcher Trial, an expanded paperback edition with a lengthy new postscript was issued in 1987 [the version I own]. Penrose and Freeman were journalists on the enterprising Sunday Times team, and they had been spurred into action by the death of Blunt in 1983. The subtitle of their work is The Secret Life of Anthony Blunt, yet it covers much more.

Penrose and Freeman had shown the skills of some old-fashioned sleuthing in flushing out Cairncross and Leo Long in the wake of Andrew Boyle’s book. In December 1979, following up on a clumsy hint from Sir John Colville, Winston Churchill’s sometime private secretary, Penrose had landed on Cairncross’s name and tracked him down to Rome, where they interviewed him, and it was Arthur Martin himself who told the reporters that Straight had informed him about Long. In this regard, the role of Martin in Penrose’s and Freeman’s story is quite remarkable. He is cited generously, having granted the authors off-the-record interviews in 1985, at a time when the Government was attempting to tighten up on unauthorized disclosures by retired intelligence officers (such as Peter Wright). These interviews provide the bulk of Penrose’s and Freeman’s account of Blunt’s confession. Was Martin being encouraged to string West, Pincher, Costello and others on with conflicting stories, just to sow confusion?

On pages 431 and 432, the authors offer as flattering a profile of Martin as you will find anywhere else: ‘unprepossessing, self-made, and down-to-earth’. He had enjoyed an unconventional entry into MI5, and had headed D1, the service’s ‘elite section’ responsible for Soviet counter-espionage since 1960. Penrose and Freeman portray him as ‘a creation of John le Carré; a brooding spycatcher’. “His mind was a constant blur of bluffs and double-bluffs and, although he never claimed to be an intellectual, he was quick-witted and open-minded”, they go on to write. [This goes entirely against the grain of how his close colleague Peter Wright would describe him in Spycatcher.]

Yet Martin was not sharp enough to construct his own legend carefully, since, right off the bat, he records a series of events that counters what he has told before. Perhaps the ‘constant blur’ of his impostures had destabilised him. Martin relates how, when he arrived in Washington, on his way to interview Cairncross, he found a message from Sullivan to meet him at the Mayflower Hotel that afternoon. There he met Straight, who told him about his recruitment by Blunt, alongside Leo Long. He then claimed that he returned from the USA a few days after his meeting with Straight. The authors add that ‘the trip had gone better than Martin had dared hope. John Cairncross had, or so Martin believed, confessed to having passed information to the Soviets.” Yet Penrose and Freeman offer no explanation of the timeline of the Cairncross interview, and do not question Martin’s newest account, which directly contradicts what he told Pincher and West.

Thus the three of them dig a deeper hole. “There was a delay of several months between Martin’s return from the States and his crucial meeting with Blunt when he presented Straight’s evidence”, they write, and then have to fall into useless contortions trying to explain why there was such a delay. Thus they offer a long digression into the Profumo affair, before returning to the main plot. “Martin and Hollis spent weeks debating how to handle the Straight material”, even though Martin was a member of the anti-Hollis faction, the ‘Young Turks’, and Martin has to offer his interlocutors a crust that maybe the anti-Hollis group was wrong about him.

The emphasis that Penrose and Freeman make on Martin’s and Hollis’ intense collaboration on a strategy for Blunt rather goes against the grain of Hollis’s abrupt suspension of Martin a few weeks later. According to Martin, he and Hollis came to concur on the need to offer Blunt immunity from prosecution. The authors then go on to describe the negotiations with the Home Secretary, the Attorney-General, and the Queen’s private secretary, before describing the fateful meeting of April 23, 1964. And this is the story that has been picked up as the ‘official’ account by various writers since.

The key ‘facts’ are as follows. Martin asks Blunt if he would mind his using a tape-recorder. Blunt nods in assent. Martin says he has unequivocal evidence that Blunt had been a Soviet agent during the war, something that Blunt denies, as the assertion simply wasn’t true. Martin then introduces his meeting with Straight, and outlines the allegations Straight made. Blunt is expressionless, so Martin decides he has to use the immunity card. Blunt walks to the window, pours himself a large drink, and turns to Martin, saying ‘It is true’. Martin plays back the tape, so that Blunt can agree it was an accurate record of the conversation. Martin reminds Blunt that ‘total co-operation’ is the price of immunity. Blunt nods: the meeting, lasting twenty-five minutes, is over.

There is much bogus about this story. If readers recall the description by Andrew at the beginning of this bulletin, they might wonder why Martin made no mention of Cairncross in this account. Blunt ‘left the room’ in the authorised version: not so here. The business with the tape-recorder is absurd: first of all, the real meeting could have been only about ten minutes if the total length included the playback, and yet in the authorised version Blunt requests five minutes to ‘wrestle with his conscience’. (Did Martin turn the tape-recorder off during this time?) And how would Blunt have been able to challenge the accuracy of what had just been recorded? Martin’s quickness in switching to the offer of immunity is clumsy and unrealistic. Why did he not exploit the Cairncross episode more imaginatively?

One might conclude that the version supplied by Andrew was an attempt to ‘correct’ what was a transparently spurious record on file, since other evidence would show that Cairncross had provided a full ‘confession’ only weeks before Blunt was given the same treatment. Yet the argument is full of holes, and should have been picked apart at birth.

Conspiracy of Silence was recognized as having benefitted from the indiscreet, and surely unlawful, revelation of information from present and past intelligence officers. According to Hansard, on November 19, 1986, Mr. Campbell-Savours (Member of Parliament for Workington) asked the Attorney-General whether he would prosecute Russell Lee, Christopher Harmer, William Luke, T. A. R. Robertson, Lord Rothschild, Leo Long, Andrew King, William Skarden [sic], Stephen Demoubray [sic], Lord Dacre, George Carey-Foster, Nigel Burgess, Constance Burgess, John Cairncross, Malcolm Muggeridge, Sir Robert Mackenzie, Sir Ashton Roskill and Lord Clanmorris under the Official Secrets Act of 1911. Arthur Martin – whose name appears most prominently in the book – was not listed.

Molehunt: Searching for Soviet Spies in MI5 by Nigel West (1987)

By 1987, Nigel West felt confident enough to claim, as he did in his Introduction to Molehunt, that “The molehunts have now ended, and are of only historical importance, so at last the full, bizarre story can be told.” I recommend readers return to West’s book, published as the Spycatcher trial was concluded, but before Wright’s book came out, to assess how comprehensively West’s judgements should be accepted, and to learn the fate of ELLI, and Graham Mitchell, West’s bête noire for the role of chief mole in MI5, before determining whether they agree with West’s opinions.

Where was West looking for his authority? His text is irritatingly imprecise, his chronology customarily haphazard, and his sources generally feeble. In his chapter 3, Operation Peters, which covers the events of interest to me here, the only sources he lists are Straight’s After Long Silence, Goronwy Rees’s A Chapter of Accidents, and a World in Action programme featuring Peter Wright. Yet the text is littered with evidence that could have come only from Arthur Martin. And, immediately, new variations on the significant visit to the USA in 1963 appear.

West introduces Martin’s activities in the context of the FLUENCY Committee, chaired by Peter Wright, that had been set up in late 1964 to take over the investigation into moles. Operation PETERS, which had looked into Graham Mitchell as a candidate, had been wound down. West salutes Martin’s success with Cairncross and Straight in the following terms: “ . . . Arthur Martin had scored an important success during his visit to America to explain the outcome of the Peters inquiry to the FBI.” West thus explains Martin’s visit to Cleveland as an incidental opportunity, a by-product of his briefing, rather than the main purpose of his assignment. Hereby Martin conflates two visits, or West has got his wires crossed over what he was told. “Since Martin was already in the United States, he decided to have a second bite at the cherry.” This is all nonsense, as we know that Cairncross was recently in London, and could have been interviewed there, and that Martin had expressly been sent out to interview Cairncross.

The next event is Martin’s return to Washington, where he apparently ‘briefed William Sullivan of the FBI on the latest development’, and then was introduced to Straight. West next travels over the now familiar Straight confession. “Armed with this valuable information, Martin returned to London and informed Hollis of this remarkable development.” Yet West is very terse about the build-up to the confrontation at the Courtauld, where ‘all that remained to be done was to obtain his [Blunt’s] co-operation.’ Then we receive a modified version of the engagement, given by West as April 22, not the 23rd, and described as taking place ‘in midmorning’, not in the evening, as Andrew claims. The Straight experience is related (but not the Cairncross meeting), and the offer of immunity given. “Blunt slowly got up from his desk, walked over to a tray of bottles and poured himself a stiff gin, apparently deep in thought. As he did so he turned and said, simply: “It’s true.”

What are we to make of this? That Martin would discuss with Sullivan the Cairncross confession before he had even spoken to his bosses at MI5 is simply absurd. That would have been extremely irresponsible – and highly unlikely, if the F.B.I. truly had withheld their information on Blunt for six months. Why does Martin now push back his meeting with Straight and Sullivan to the end of his visit(s) to Cleveland? And why are all those details about the Courtauld meeting such a mixture of the precise (‘he poured himself a stiff gin’), and the erratic (Blunt’s leaving the room in one account, and walking over to the window in another). The whole imbroglio is simply farcical.

West takes up the ‘bluff’ angle again, and is generous in his praise of Martin’s performance. “The trump card had been the offer of immunity from criminal prosecution.” But, if Martin thought he had sufficient information from Straight to prove Blunt’s guilt (which he did, although it would not stand up in court), it wasn’t a bluff at all. Just a ruse to get Blunt to talk without all the embarrassing business of a trial. West’s conclusion runs as follows: “If self-preservation was to be a factor in Blunt’s motivation, the carrot dangled so skilfully by Martin contained everything he might be seeking: no embarrassing police involvement; no public humiliation; no obvious betrayal of friends.” But what did MI5 and Martin gain from this? A ‘cooperation’ that allowed Blunt to be as secret and reclusive as he wished.

Molehunt is thus a rather sad and inadequate display of sleuthing. West allows Martin to get away with an alarming number of untruths, and it is merely further evidence that these chroniclers, as they obtained their ‘insider’ information, naively believed that they were the sole receivers of the actualités. And the simplest of facts are not cross-checked.

Spycatcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer by Peter Wright (1987)

Spycatcher is an unreliable memoir. I have drawn attention to some of its flabby arguments in HASP: Spycatcher’s Last Gasp, and it is likewise a very shaky source for the events of 1963 and 1964. There are no footnotes, no sources or references quoted, and thus the reader frequently cannot discern how Wright knew about events at which he was not present, or on whom he relied for information. The approach to chronology is chaotic: one might alight on an interesting event, but then have to step back for several pages to determine which year the author is writing about, as he weaves around, skipping from topic to topic.

Yet there are diamonds in the rough. On more neutral topics, where it would appear that Wright has no reason to dissemble, some important facts emerge. He provides (undated) insights on Hollis’s decision to move Furnival Jones from his position as head of D branch to C Branch, in preparation for his appointment as Deputy-Director on Mitchell’s retirement. Furnival Jones was replaced by Malcolm Cumming, an old and not very imaginative hand, and Wright claims that Arthur Martin expected to get the job himself. Mitchell retired in September 1963, so West’s account of Martin’s return to inform Furnival Jones of the Straight interview is wrong. Further ammunition for Martin’s resentment, and Hollis’s distaste for Martin’s disruptive tendencies, is provided, yet, if Martin did work closely with Hollis on the Blunt plan, it would appear that Cumming had been considered superfluous by that time. What should also be noted is that Wright himself drew attention to Martin’s faults, dubbing him ‘temperamental and obsessive’, and noting that he ‘never understood the extent to which he had made enemies over the years.’

Wright also adds details on the activities of summer 1963, where Hollis, facing opposition from his officers on disclosing the fruits of the Mitchell inquiry to the Americans, ‘glowered at’ Martin across the table when he announced, that he would visit the USA himself, to keep the F.B.I. informed. Wright then states how Hollis left for the United States ‘almost immediately’, but, since the controversial meeting where Hollis’s voice had been outnumbered is undated, we cannot pin an exact time on his departure. ‘Shortly after’, Martin followed him. Thus there exists strong evidence that Hollis and Martin were in a position where they could have, and should have, been briefed about Straight. Yet Wright was almost certainly not at that meeting himself: he started working for Martin only in January 1964. He also provides details about the scientist/officer, Hal Doyne Ditmass, whom Hollis tried to remove from D3 in May 1964, at a critical time of negotiations with the Americans. That was another event – accompanying the failed promotion – that riled Martin.

The most astonishing revelation, however, is made when Wright introduces the Blunt case. “It brewed up in late 1963”, he writes, “when MI5 were informed by the FBI that an American citizen, Michael Whitney Straight, had told them that Blunt had recruited him for the Soviets while they were both at Cambridge in the 1930s.” This awareness of a much earlier disclosure forces Wright to re-draft the reason for Martin’s visit to Washington. “Arthur Martin flew over to interview Straight, who confirmed the story, and agreed to testify in a British court if necessary.” Thus, in one short sweep, Wright annuls all the previous leaks that the meeting with Straight was the first time that MI5 heard about the Straight-Blunt imbroglio, that it was a coincidental encounter, engineered by Sullivan, and that Martin’s chief purpose in visiting the States had been to interview Cairncross. Wright does not even mention Cairncross in this situation. It is an extraordinary proof that MI5 had lost control of the legend.

Wright is lapidary about the events leading up to the meeting at the Courtauld. His account runs as follows: “. . . Blunt was confronted by Arthur Martin and almost immediately admitted his role as Soviet talent spotter and spy.” Yet he has not finished yet. After a diversion about the impact of the Blunt confession on Victor and Tess Rothschild, he tells how Blunt swiftly named Leo Long and John Cairncross as fellow spies, and how they both then confessed. “Long, informed by Arthur that a prosecution was most unlikely provided he cooperated with MI5, swiftly confessed, as did Cairncross, who was seen by Arthur in Rome.” Wright was either completely uninformed about what really happened, or very stupidly tried to cast a web of deceit around events in the belief that he would not be smoked out. Cairncross had already confessed, according to the official line. Dick White, for one, must have been horrified when he read Spycatcher.

In summary, therefore, we have a rather ingenuous admission that MI5 did learn about Straight from the FBI in November 1963, which makes a lot of sense, and then a naïve attempt to explain the outcome in a way that belies nearly every account of the story. What Christopher Andrew made of all this is a mystery: he lists Spycatcher as one of his sources in his authorised history, but he does not investigate the claim about the November debriefing at all.

Mask of Treachery by John Costello (1988)

The final study in this section is John Costello’s Mask of Treachery, bearing the rather convoluted sub-title Spies, Lies, Buggery & Betrayal, The First Documented Dossier on Anthony Blunt’s Cambridge Spy Ring. It is an extraordinary work, reflecting the author’s dedicated search to discover all the facts about the treachery of Blunt and his cronies. He digs far and wide. Yet it is also a highly flawed creation, as if Costello imagined that, by assembling all the information in one place, a confident hypothesis about the moles inside MI5 would magically appear. His conclusion? Remarkably, that Guy Liddell was the obvious flake in MI5’s management ranks, a suggestion that distances himself from the dominant theories of West (Mitchell), and Pincher, Martin and Wright (Hollis).

The major problem with Costello’s record is that he drags in all manner of possibly relevant details, but omits to apply any rigorous methodology in his approach, not attempting to define the reliability of all evidence he cites, and leaving many matters of chronology unsettled. Very typical is his handling of the Straight business. He echoes the accepted fact that Straight went to the Justice Department, and then the F.B.I., on June 7, 1963, but then hypothesizes that ‘it would not be surprising if he had not considered himself under an obligation to give Blunt the same sort of warning in 1963 that he had given Burgess twelve years earlier.’ Costello then assembles the following weird paragraph:

“Straight had several weeks in which he could have alerted Blunt that an impending Presidential appointment would require FBI clearance and would raise the possibility that the Cambridge connection would be uncovered. According to Stella Jefferies, an administrative secretary at the Courtauld, Straight appeared unannounced at the institute one day that summer. She says Blunt ‘was not keen to see him’. Later, she heard Blunt telling someone ‘he – meaning Straight – was going to shop them.’ Jeffries claims the incident stuck in her mind because it occurred shortly before the director himself went off to America – at short notice.” Blunt, rather suddenly, decided to spend six weeks in the United States.

But then Costello immediately adds: “Straight has admitted that he was in England that April, but he insists that he did not visit the Courtauld.” That is, however doubly irrelevant. Straight did not know about his appointment, and the need to confess, back in April, and thus not visiting the Courtauld at that time merely casts suspicion on his testimony. So when did the encounter occur? Costello adds a Footnote that claims that Mrs. Jeffries said it was in July 1963, but the letter from Blunt she presents is dated August 1962! Pincher claimed that Straight was still being debriefed by the F.B.I. in August. And if Blunt heard about Burgess’s death in Moscow on August 19 while he was at Pennsylvania, probably at the end of his six-week engagement, it leaves no time for Straight to have warned Blunt – unless he contacted him through other means, and arranged to talk to Blunt while he was at the university. The whole cavalcade is a mess, with much possibly irrelevant detail being introduced without analysis.

What makes this testimony even more dubious is that Blunt had been invited by Pennsylvania State University the previous year to lecture at the summer school in 1963 (as an announcement in the Art Journal in 1962 proves), and thus the idea that he made a sudden decision is patently false. And, since his invitation had been well publicized, Michael Straight would certainly have learned about it. Thus we have to face the possibility that Straight and Blunt did in fact meet in April 1963, despite Straight’s denial.

Lastly, Costello covers the Straight-Martin encounters. Yes, Sullivan did not approach Straight until January 1964, when he arranged for him to meet Martin at the Mayflower Hotel, where Straight told Martin all. “Straight did not know that Martin had just finished interviewing John Cairncross at Northwestern University”, he writes. He might just as well have written that Straight did not know that Martin was on his way to interview Cairncross. He then presents an uncontroversial account of the events leading up to the immunity deal, but then introduces an insightful observation: “Considering what was at stake in Blunt’s confession, it is astonishing that Arthur Martin was sent alone to confront Blunt on the morning of April 23, 1964. (American counter-intelligence officers have assured me that the standard practice calls for at least two officers to be present.) Martin still believes that Blunt had been forewarned and held out for the immunity deal.”

Thus we have a third timing of the event, the morning of the 23rd, as opposed to Andrew’s evening of that day, and West’s mid-morning of the 22nd. And Martin surely knew that he was involved in a staged set-up, in which he and Blunt were equal players. Costello continues by tersely stating that Blunt and Cairncross were unmasked by Blunt, and that they ‘confessed on the understanding that they would not be prosecuted either’. So what was going on between Martin and Cairncross in January, Mr. Costello? There is no answer.

* * * * * * * *

This wave of studies shows an extraordinary lack of discipline. The authors must surely have felt themselves in competition, yet one can detect a large amount of collaboration behind the scenes. None of them, however, applied any amount of rigour when evidence turned up that clearly contradicted other evidence they cited. And yet, until now, I do not believe they have properly been called to account.

The Sources: Wave 3 – The Era of Biography

A strange hiatus settled on the investigations between 1988 and 2005. For example, Christopher Andrew’s and Oleg Gordivesky’s KGB: The Inside Story (1990) has only a couple of sentences on the events of 1964. Matters picked up again with the release of a number of biographies and memoirs, the first of which was Tom Bower’s profile of Sir Dick White. But first, Nigel West’s gallery of spies.

Seven Spies Who Changed the World by Nigel West (1991)

Nigel West selected Blunt as one his Seven Spies (the others being Popov, Schmidt, Buckley, Blake, Powers, and Wynne). Whether his title is meant to signify that these seven ‘changed the word’ (while others did not), or whether the author just happened to choose these seven for some special reason (since all spies change the world, just as all non-spies do, too), or whether the title is simply one foisted on West by his publisher, is not clear. In his Introduction, however, West does state: “All these men, to a greater or lesser degree, have made a remarkable contribution, either positive or negative, to the course of history, and most have been known to me personally.”

West’s caption for Blunt’s photograph is unfortunate. “Anthony Blunt, a long-term Soviet asset who penetrated MI5 and then switched sides in return for an immunity from prosecution. His confession ruined the careers of a dozen top civil servants, but MI5 eventually concluded that he had duped his interrogators and remained loyal to the KGB.” ‘Switching sides’, eh? Receiving an immunity deal, not specified in writing, in return for promising to ‘co-operate’, is hardly descriptive of the process of realigning one’s skills to the cause of the erstwhile enemy – especially when he could not help whatsoever with espionage against the Soviets.

The story of Blunt is a fascinating one, but marred by West’s irritating practise of providing references for many well-thumbed and familiar incidents, while inserting highly provocative assertions that do not carry any supporting evidence whatsoever. [They are surely feeds from the highly unreliable Martin.] For example, he writes (without identifying Martin): “This [review] resulted in an inconclusive statement from Cairncross, then lecturing at Northwestern University, who reluctantly named James Klugmann as his recruiter at Cambridge.” No source; no date; no explanation of ‘inconclusive’; no indication of why Cairncross admitted something ‘reluctantly’, or why he admitted to anything at all. He then goes on to write, about Straight’s confessions, that ’Petty inter-agency rivalry, exercised by J. Edgar Hoover, had prevented the FBI from sharing this crucial information with MI5.’ Another bold and cryptic statement that does not disclose a source, nor provide strong evidence.

The description of Blunt’s confession is likewise weak. West discloses nothing about the intriguing that went on, and repeats his notion of Blunt’s ‘switching sides’, only a few lines later equating this act with ‘a decision to collaborate with MI5’. When he identified his fellow conspirators, ‘among the first were John Cairncross, who was already known to MI5, and Leo Long, who had never previously been a suspect.’ Well, of course Cairncross was known to MI5, not solely because of the confession that West had revealed on the previous page, but was that all that there was? Leo Long, moreover, had been known a suspect, having been caught in the act of espionage in MI14 in 1944. West appears as muddled as he was in MI5.

My 5 Cambridge Friends by Yuri Modin (1994)

Yuri Modin was the controller of the Cambridge Five at the end of WWII and into the 1950s. His memoir has some useful facts about his dealings with the spies (especially John Cairncross), but his access to reliable information is naturally flawed. He offers some problematic ideas about the confessions of Blunt and Cairncross that need to be recorded as they constitute part of the mythology.

On Cairncross, he writes that ‘some people say he was finally exposed by MI5 in 1964. I think he confessed, but well before that date, in 1951 or possibly 1952’. He goes on to state that he is convinced that ‘Cairncross told everything he knew in the early 1950s, in exchange for a promise of immunity.’ Of course, Cairncross did make a very constrained confession in 1952, but the evidence thereafter confirms that it was only after Blunt’s confession that he extended his story, but even that failed to do justice to his complete record of espionage, which was revealed in KGB archives.

As for Blunt, Modin tends to overstate Blunt’s attachment to Guy Burgess, and interprets Blunt’s desire to confess as a reaction to Burgess’s death in August 1963. He introduces yet a new date (early 1964, ‘soon after’ Blunt’s death) for the timing of Blunt’s confession, and describes it as follows: “All the same, he prepared and refined the actual content of his confession with the greatest care, and delivered it only when he had received the assurance of the Attorney-General that he would be immune to prosecution if he revealed the truth about his dealings with the Soviets.”

Where Modin gained this intelligence is not clear. There is no doubt a measure of truth about Blunt’s carefully honed confession, but to suggest that he was in control of the whole process does not bear close analysis.

The Perfect English Spy by Tom Bower (1995)

Tom Bower took over from Andrew Boyle the project of writing Dick White’s biography, since Boyle had died in 1991. Boyle had gained White’s confidence for a while, but had also annoyed him by pressing too hard on some sensitive matters. Nevertheless, the very wary response Boyle received from White on the Blunt case proved to him that this was a sore subject with the only man to have been head of MI5 and MI6.

The Perfect English Spy is a bit of a muddle, written without a lot of precision, and relying too much on volumes like Spycatcher, and unattributable or undocumented conversations Bower had with various figures in intelligence. Yet it has enough substance to provide another dimension to the Molehunt – the fact that White, having held a prominent role in MI5’s counterespionage operations from the day Blunt joined in 1940 to the day White retired in 1956, had even more at stake in protecting his own reputation, and that of the Service, than did Hollis himself. White’s involvement in the action thus explains a lot of the successful cooperation between the CIA and British Intelligence, with Maurice Oldfield (White’s representative in Washington) and White himself acting as go-betweens to Arthur Martin and Hollis in MI5 (Martin having been White’s loyal sidekick in the Burgess/Maclean/Philby deception of 1951: see DickWhite’sDevilishPlot).

Thus Bower starts off by emphasizing Martin’s close relationship with White, and the reinforcing to him of Angleton’s persistent declarations about Soviet penetration. White shows a lot of trust in Martin, and encourages him, in early 1963, to approach Hollis on the need for a proper investigation, even following up by speaking to Hollis about the requirement for Graham Mitchell to be surveilled. At the same time, Angleton of the CIA is applying pressure on Oldfield on the Golitsyn testimony, and encourages Oldfield and Martin to invite the defector to Britain that summer, where he causes some havoc. Hollis acts unreasonably: White is clearly in charge of the investigation. The rather ineffective Martin Furnival Jones has been moved in a position within MI5 to head the investigation, and the even less impressive Cumming takes over as Martin’s boss in D Division.

It is here that Bower calls out White for being overimpressed by Martin, whom Bower categorises as ‘not a trained intelligence officer nor a skilled interrogator; hardworking but with no understanding of the history of espionage’. Readers should bear this in mind when they consider why Martin was selected as the officer most likely to obtain, working on his own, a confession from Blunt in April 1964.

When the Mitchell affair petered out, an important meeting was held in September 1963, at Hollis’s house (Bower does not record who else was there), where White strongly recommended that MI5 inform the CIA and the FBI about the state of the case, and their ongoing concerns. In Bower’s account, Hollis ‘reluctantly agreed ‘to fly to Washington to do just that. [This is in contrast to the description by Peter Wright (see above) of what was perhaps a meeting with his officers immediately afterwards, where Hollis grabbed the reins and told his subordinates that he was going to Washington.] Hollis apparently received a derisory reception there, especially from Angleton and the CIA, although Hoover and Sullivan of the FBI were also fairly contemptuous. Bower then writes: “Martin heard about Hollis’s humiliation from Angleton. At the same time, Angleton invited Martin to consult with him in Washington.” No dates, or items of correspondence identified, and Bower does not specifically say that Martin had flown out in Hollis’s wake (a fact we have learned elsewhere). Yet, while Martin (of MI5) dealing with the CIA’s Angleton was highly irregular, it does provide a clue as to how the CIA, behind Hoover’s back, and surely with Oldfield’s assistance, was able to engineer the meeting between Straight and Martin in January 1964. And it adds another wrinkle to the question of Martin’s primary mission in visiting the Unites States at that time.

The narrative thins out after that. Straight repeats his story to Martin, who returns to Britain excited by the disclosure [patently untrue, and an echo of Martin’s dissemblance marked earlier]. He gives his report to Hollis, and they meet with White, who was apparently ‘shaken’ by the revelation. Accusations against Blunt had been common in Leconfield House, but White claimed to have been ignorant of the whole business. White thus had to face the dilemma of protecting the Queen and the Government from embarrassment, and pursuing the right cause, which would be prosecution. He consults Trend, who advises him of the political realities. White tells Hollis that sufficient evidence would never be found to prosecute any of the Cambridge Five, so the plan to trap/entice Blunt with a pardon goes ahead.

Apart from Hollis and White, Bower indicates that only Burke Trend, the Home Secretary (Brooke) and the Attorney-General (Hobson) were in on the deal. Now Bower uses Penrose and Freeman as his source for the event of April 23, 1964. How much Martin knew, going in to the Courtauld that day, is not clear. In any case, he soon got incensed by the lack of aggression in going after Blunt, and Blunt’s less than comprehensive revelations., and incurred the wrath of Hollis and Cumming. He was thus suspended, and later transferred to MI6, to work under his old mentor, Dick White, As Bower shrewdly observes, at this time White appeared to express more sympathy for Martin and Wright than he did for Hollis.

The Enigma Spy by John Cairncross (1995)