This segment really belongs as an appendix to ‘Sonia’s Radio’, but I deemed it to be of such startling importance that I decided to devote a Special Bulletin to it. It concerns a letter sent from Geneva to Len Beurton, the husband of Ursula, agent Sonia, in Kidlington, Oxfordshire, in March 1943, one that provokes an entire re-evaluation of the Beurtons’ relationship with the authorities. The letter was intercepted by the U.K. censorship before being mailed to the address to which Beurton had moved in August 1942, to be reunited with his wife, and it appears in one of the Kuczynski files at the National Archives, KV 6/41.

KV 6/41 must be one of the richest and most provocative files at Kew. Its activity record shows that it was a very frequently inspected folder during the 1980s and early 1990s. A book could be written on it alone, as it offers tantalising glimpses of other worlds, other discussions, other communications, and other meetings, the proceedings or records of which have been withheld or destroyed. Thus this analysis is highly exploratory, and reflects more my thinking as it has evolved rather than a tidy and complete item of research. I do not have clear answers to many of the riddles it offers, and am seeking help from my readers.

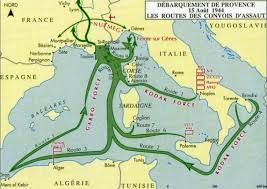

A recap may be useful for the occasional coldspur reader. Len Beurton was a veteran of the International Brigades in Spain, and had been recruited by his friend Alexander Foote to join the Soviet espionage team in Switzerland in early 1939, and train as a wireless operator under Ursula Hamburger (as she then was), née Kuczynski. With her Swiss visa soon to expire, Sonia was ordered, early in 1940, to travel to the UK, but needed a British spouse in order to gain a UK passport. Foote initially responded to the call, but then evaded it, on the grounds that he had a pregnant girl-friend in Spain, and recommended Beurton instead, who accepted the role with enthusiasm. Foote then provided perjurious evidence of Sonia’s husband’s infidelity in order for the pair to be married. Thereafter, SIS in Switzerland helped to arrange Sonia’s passage, via France, Spain, and Portugal, to England, where she installed herself and two children in Oxford at the end of January 1941. Len had not been able to join her at first, since his enlistment in Spain disqualified him from being given a visa to pass through France, Spain, and Portugal. After pleas from Sonia to the MP Eleanor Rathbone, and with the intervention of the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, SIS’s representatives in Geneva supported the project to bring him home. They provided him with a false identity, and Len was eventually able to leave the country, arriving back in the UK in late July 1942. Almost immediately, he and Sonia moved from their rented bungalow in Kidlington to a cottage attached to the house of Neville and Cissie Laski, in Summertown, Oxford, where Sonia rather flamboyantly installed her wireless set. Len, meanwhile, was thought to be spending time at the old address, and MI5’s F Division requested that mail sent to Len (but not Sonia) at Kidlington be intercepted. This letter is one of only two addressed to Beurton on file.

The Geneva Letter

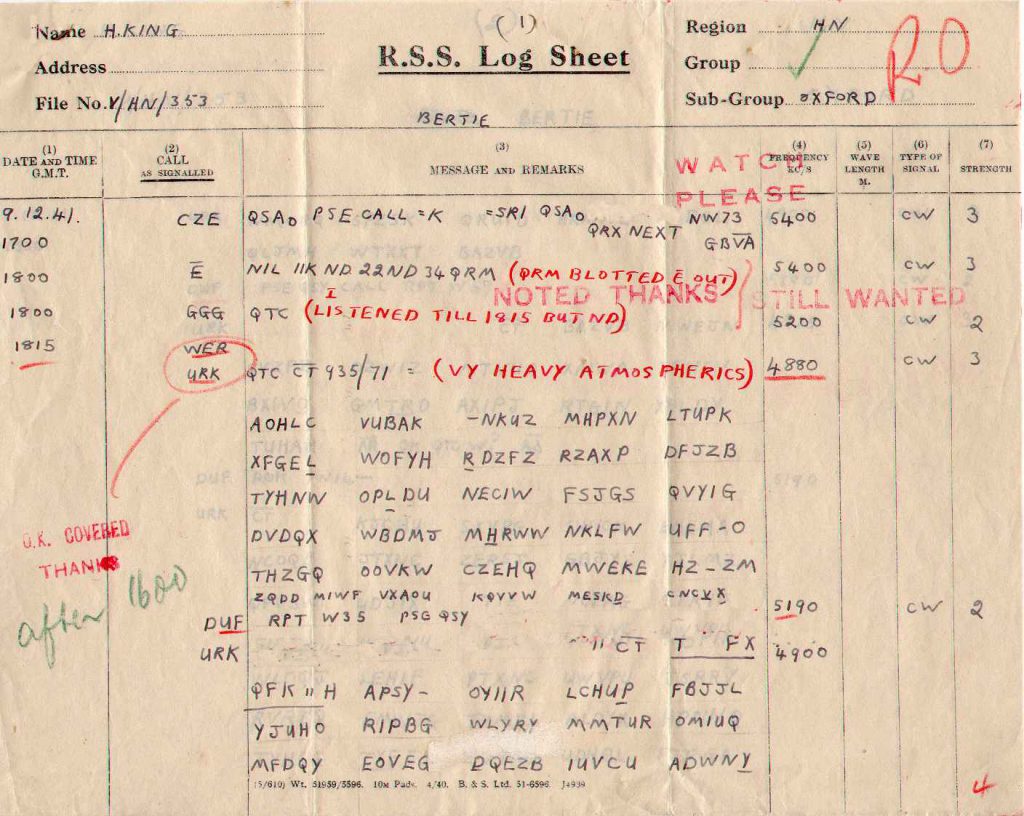

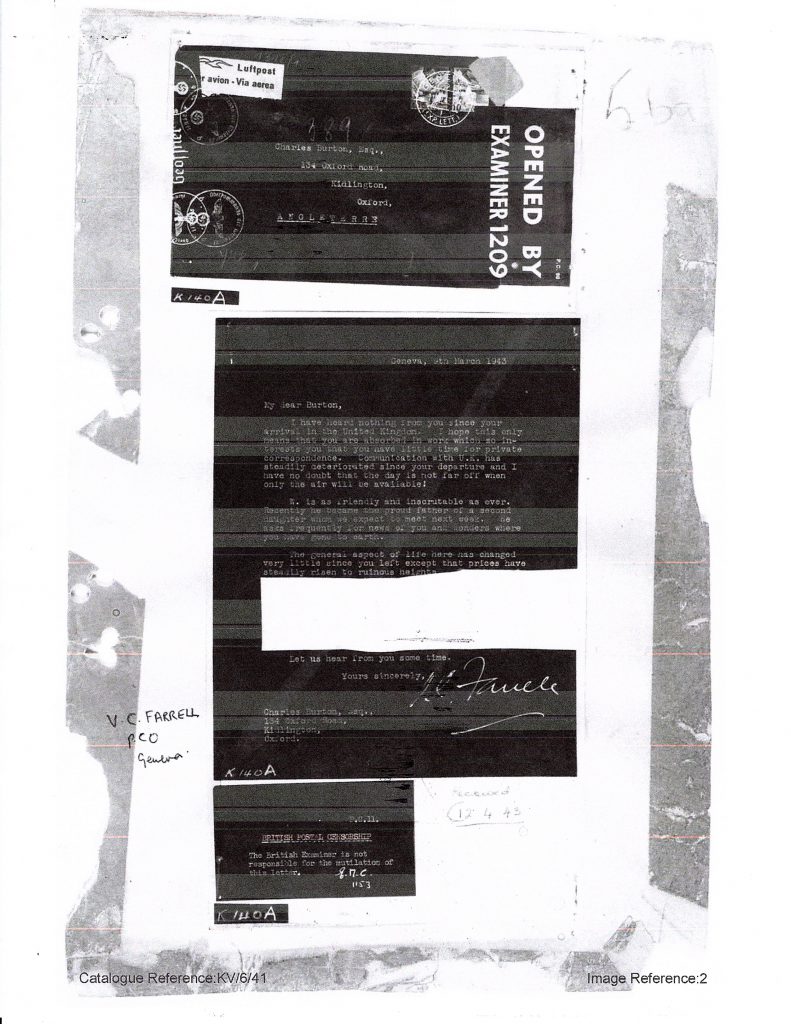

An image of the document appears here:

[Do not be concerned about the readability of the document. I present it here to show that it exists, and to reveal one or two important aspects of it.]

First of all, the text:

“My dear Burton,

I have heard nothing from you since your arrival in the United Kingdom. I hope this only means that you are absorbed in work which so interests you that you have little time for private correspondence. Communication with U.K. has steadily deteriorated since your departure and I have no doubt that the day is not far off when only the air will be available!

W. is as friendly and inscrutable as ever. Recently he became the proud father of a second daughter whom we expect to meet next week. He asks frequently of you and wonders where you have gone to earth.

The general aspect of life here has changed very little since you left except that prices have steadily risen to ruinous heights.

[ ‘paragraph missing’ * ]

Let us hear from you some time,

Your sincerely, V. C. Farrell”

* British Postal Censorship

“The British Examiner is not responsible for the mutilation of this letter.”

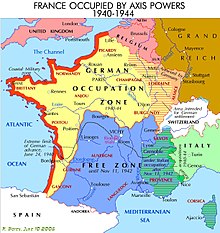

An inspection of the envelope indicates that the latter passed through German territory: several stamps with the swastika appear on the left side, with the slogan ‘Geöffnet’ [opened] between them. (The challenges of delivering airmail from Switzerland when the country was surrounded by Axis forces had not occurred to me. I found a link to the potentially very useful following article: “Zeigler, Robert (2008): “The Impact of World War II on Airmail Routes from Switzerland to Foreign Countries, 1939-1945” in the National Postal Museum at the Smithsonian, but the item has disappeared.) What is not clear is whether the letter was automatically forwarded to Summertown (if instructions for forwarding mail were still extant and valid), or whether it was simply delivered to the address at Kidlington, under the assumption that Len Beurton still lived there. An earlier item on file (at 47B) offers a list of intercepted mail from September 19 to October 10, 1942, including an item redirected from Kidlington, sent from Epping, in Essex, but there is no other record of interception details.

The story of the interception requests is a puzzle in its own right. The record is predictably incomplete, but the first request, for all correspondence sent to Avenue Cottage, Summertown, is made by JHM of F2A on September 15, for a period of two weeks. [This ‘JHM’ is probably the renowned punctilious solicitor, J. H. Marriott. Marriott was reportedly working in B1A as Secretary of the XX Committee by this time, but he was probably performing double-duty. His name appears in the Beurton file after the war, when he returned to F Division for a while.] F2A was responsible for ‘Policy activities of C.P.G.B. in UK’, under John Curry’s ‘Communism and Left-Wing Movements’ Division. D. I. Vesey (B4A), working for ‘Suspected Cases of Espionage in UK’, under Major Whyte in Dick White’s ‘Espionage’ B Division, had referred to Beurton’s residence in Kidlington up until September 9, at which time he was seeking an interview with Beurton, which occurred on September 18. (His belated report was not submitted until October 20: the delay seems unnatural and indolent.) JHM’s analysis of the mail received from September 19 until October 10 is on file. It is a fascinating document, but there is no indication that any of the correspondents were followed up.

One entry, concerning the letter from Epping, Essex, introduced above, has been redirected from 134 Oxford Road, Kidlington, strongly indicating that the Beurtons had cleared out and informed the Post Office of their move. Another, astonishingly, is from Alexander Cadogan, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, a very important figure in the war, accustomed to accompanying Eden and Churchill around the globe, addressed to ‘L. C. Beurton, Esq.’. Cadogan had also been instrumental in authorizing Beurton’s liberation from Switzerland. Was he perhaps asking whether his protégé had settled in satisfactorily? It seems very provocative for Cadogan to be writing, in his own hand, but JHM’s entry incontrovertibly records ‘envelope signed – A. CADOGAN’. A few letters are described as having been sent from Kidlington, but only one is identified – Dr. Duncan, at Exeter House. Is that a clue? It would have been highly negligent for these correspondents not to be followed up. The lead from Epping might have been very fruitful: Alexander Foote was later to tell his interrogators in MI5 that Sonia visited her contact in Epping once a month.

And then, on November 30, Hugh Shillito, F2B/C, ‘Comintern Activities General and Communist Refugees’ & ‘Russian Intelligence’, inquires of the G.P.O whether there is a telephone at 145 Oxford Road, stating that Beurton has ‘gone to live there’, as if Beurton had left the new family nook in Summertown to return to the premises north of Oxford. The following day, Shillito makes a request to Colonel Allan of the G.P.O. for a Home Office Warrant to check all of Len Beurton’s mail (but not his wife’s). Nothing had been submitted by December 19 (‘unremunerative’, in Shillito’s words), and the first item is the Geneva letter. But Shillito presumably sat next to JHM, and exchanged ideas and insights with him and with Vesey. How could Shillito have possibly been mistaken in thinking that Len was spending time at the address in Kidlington?

The Sender of the Letter

Who was the sender of this remarkable letter? The signature is somewhat inscrutable, but a helpful note visible at the side states: ‘V. C. Farrell. P.C.O., Geneva’, an annotation that was surely made much later. And there lies the real drama of the correspondence. For ‘P.C.O’ stands for ‘Passport Control Officer’, and that role was adopted by SIS as the (supposedly) undercover job title for SIS representatives in consulates and embassies abroad. Yet Victor Farrell was more than that. While his name does not appear in Keith Jeffery’s authorised history of SIS, Jeffery merely stating that ‘in September 1939, SIS had a station in Geneva, headed by a Passport Control Officer, with an assistant and a wireless operator’, Nigel West, in MI6, describes him in the following terms:

“One important figure already in Geneva at this time [June 1940] was Victor Farrell, an experienced SIS officer who had previously served in Budapest and had then replaced Kenneth Benton in Vienna in 1938. Farrell had been appointed to head the Geneva Station in place of Pearson, and had succeed in recruiting an extremely valuable local source of German intelligence. Farrell’s agent was Rachel Dübendorfer, a middle-aged Polish Jewess who was then working in the League of Nations’ International Labour Office as a secretary and translator.” (p 202). West also writes (p 152) that Menzies had appointed Farrell as PCO in Geneva in February 1940.

In Colonel Z, their biography of Claude Dansey, the head of the shadow Z network within SIS, (which work needs to be considered somewhat circumspectly), Anthony Read and David Fisher supply the information that Farrell had been Professor of English at the St Cyr military academy in France, and inform us that Farrell had been promoted to consul at the beginning of 1941, taking over from Frederick Vanden Heuvel. The authors also describe how the officers in Switzerland felt marooned from the outside world:

“The only way out for couriers, escapers or anyone else was the hazardous land route through southern France to Spain, using all the cloak-and-dagger paraphernalia of disguises, false names and forged papers. Radio sets were still in short supply, and in any case the Swiss, ever fearful for their precious neutrality, did not welcome the transmission of secret information which might be intercepted by the Germans and used as an excuse for invasion. The SIS therefore had only one available radio transmitter, located in Victor Farrell’s office in Geneva. This was used for urgent communications; anything less vital was sent as telegrams through the Swiss Post Office over the normal telegraph lines, enciphered by the one-time pad method . . .” (p 239)

“Sissy [Dübendorfer] was a communist, and merged her network with Radó’s, and her communications were channelled through Allan [Alexander] Foote. Yet all the time, she was being paid by Victor Farrell.” (p 247) [This refers to the famous communist Rote Drei network in Switzerland. Alexander Radó was its leader, Alexander Foote its main wireless operator. The network was also called the Lucy Ring, after its reputed main informant, Rudolf Rössler, who was based in Lucerne.]

“All that was required of her [Sissy Dübendorfer] was that she should send the material given her by Farrell to Rössler via Schneider for evaluation, and then pass Rössler’s reports to Radó. But in order to maintain the camouflage, Dansey also used the various other routes to Rössler and Radó: Sedlacek, Foote, Pünter, and the official Swiss and British intelligence organizations all played their parts in his master plan.” (p 253)

In their companion book, Operation Lucy, Read and Fisher further describe Farrell’s valuable role: “He dealt with escaping prisoners, organising routes through southern France and across the Pyrenees into Spain, then Portugal and so to Britain, besides liaising with the French and with other agents working in the ILO and similar institutions in Geneva, on behalf of the SIS. He also looked after the smuggling of arms and strategic materials such as industrial diamonds. Farrell had his own radio transmitter/receiver, through which he could contact both Berne and London.” (p 111) M. R. D. Foote’s and J. M. Langley’s book titled MI9: Escape and Evasion 1939-1945 confirms that ‘Victor’ was the (unimaginative) cryptonym of the contact officer in Geneva for escaping prisoners-of-war and SOE agents.

SIS in Switzerland

It is very difficult trying to establish a clear chronology of the movements of the SIS officers in Switzerland during World War II. The chief was apparently Frederick Vanden Heuvel, who, according to West, was flown out to Berne by Menzies (or Dansey) at the beginning of 1940 to become the case officer of the valuable informant Madame Symanska. Yet, continues West, Vanden Heuvel had to decamp to Geneva in June 1940 in the face of a possible German invasion (p 202), before returning to Berne a month or two later. Jeffery, on the other hand, writes (p 507): “For most of the Second World War the main representative in Switzerland was Frederick ‘Fanny’ Vanden Heuvel, based in Geneva”. On page 381, Jeffery refers to some twenty-five reports that were sent from Geneva between August 1940 and December 1942, channeled through Symanska, with commentary apparently supplied by Vanden Heuvel. (How these reports were sent is not indicated, but the implication is by cable or by courier. If anything was sent by wireless, it would have had to go via Geneva, but that did not mean that Vanden Heuvel worked there.)

Yet Read and Fisher have Vanden Heuvel sent out by Claude Dansey to Zürich (i.e. not Berne) in February 1940, working out of offices at 16 Bahnhofstrasse, and being appointed vice-consul in March 1940, and then consul on May 31 (p 231 & p 238). Soon afterwards, he moved his base to French-speaking Geneva, leaving Eric Grant Cable in charge, and became Consul in Geneva until the beginning of 1941. At that time he passed on the title to Farrell, and moved, nominally to take on the ‘unlikely role of assistant press attaché in Berne’, but actually to deal with Symanska in that city. That makes more sense, in view of the absence of Farrell’s name in the correspondence concerning Sonia’s passport application in early 1940. In November 1940, when negotiations were undertaken over adding Sonia’s children to her passport, a single unencrypted cable from Geneva (‘PRODROME’) can be found in the archive, but no official’s name appears on it. In the Kuczynski archive at Kew, Len Beurton attests to Farrell’s being the consular officer (‘Geneva Consulate-general’) who helped him acquire a passport under a false name in early 1942. Beurton claimed that ‘after becoming friendly with a member of the British Passport Office in Geneva, to whom he claims he gave useful information’, he was given a passport under a false name. (Document 47A in KV 6/41 confirms that Farrell, as PCO in Geneva, enabled Beurton to get his passport.)

A clue to the ‘useful information’ that Beurton had provided to Farrell appears in another (anonymous) document on file, which reports that, when in Switzerland, Beurton had been in touch with a Chinese journalist accredited to the League of Nations, one L. T. Wang. A contact with a mysterious General Kwei is posited, but the contact appears to have more relevant implications. For Sonia herself, in Sonya’s Report, describes Wang in exactly the same terms, but adds the following: “He was married to a Dutch woman. General von Falkenhausen, a former military adviser of Chiang Kai-Shek who became High Commander in Belgium during the Nazi occupation, often stayed in Switzerland and was well acquainted with Wang and his wife. Through Wang, Len occasionally learnt something of the General’s opinions and comments.”

This is highly significant, for von Falkenhausen was later known to be a fierce critic of Hitler, and was lucky to escape execution after the failed assassination attempt of 1944. Allen Dulles was sent to Switzerland in November 1942 precisely to assess the level of opposition to Hitler, and Stalin would remain highly suspicious of any peace initiatives between the western Allies and the Nazis that took place behind his back. The fact that Beurton had first-hand information about a potential anti-Hitler movement (which, of course, he continued vigorously to pass on to Moscow) would mean that he had been an extremely valuable asset for SIS, who would have wanted to keep him in place. The fact that von Falkenhausen was known to be a realistic anti-Hitler conspirator at this time has been revealed by Dennis Wheatley, who, in his memoir of his work at the London Controlling Section (The Deception Planners) recalls how the Political Warfare Executive in April 1943 floated an idea for propaganda centred on an anti-Hitler figure for whom von Falkenhausen would be a prominent supporter.

The claim that Vanden Heuvel, and then Farrell, acted as consuls in Geneva, does raise some questions, however. What is certain is that the official working on behalf of His Majesty’s Consul at the time of Sonia’s passport application, in March 1940, was one H. B. Livingston. His stamped name, with ‘SGD’ [‘signed’] appearing next to it, appears above the rubric ‘His Majesty’s Consul’. If, as the authors mentioned above claim, Vanden Heuvel and Farrell occupied that office, Livingston must have been a junior member of staff, and the narratives would suggest that both Vanden Heuvel and Farrell distanced themselves from the details of the process. Thus it is impossible to confirm confidently either Read’s and Fisher’s claim of Farrell’s appointment in early 1941 or West’s assertion that Farrell was the immediate successor to the disgraced Pearson in February 1940. A synthesis of the various accounts would suggest that Farrell was an assistant to Vanden Heuvel, maybe with vice-consular status, in Geneva in 1940, before being promoted in early 1941. (This fact has significance when assessing Farrell’s exposure to Sonia’s various arrangements.)

Moreover, Livingston was a permanent fixture. On June 3, 1942, after the intervention of Sir Alexander Cadogan, he submitted a memorandum to Sir Anthony Eden, Foreign Office Minister, explaining his failure in being unable to help Mr Beurton. Yet, on July 20, Livingston is able to inform Sir Anthony that Beurton left Geneva on July 11, rather surprisingly informing his boss only now that Beurton had been issued a new passport under the name of John William Miller on March 9. It doesn’t sound like a civil servant completely in charge of the case: the message lacks authority, and his tone is very subservient. (What is extraordinary is the fact that Livingston sent the message as a package, enclosing Beurton’s old passport, and it was received at the Foreign Office as early as August 5. ‘John Miller’, moreover, was a cryptonym used by the circle of Alexander Foote (‘Jim’) to refer to Beurton.)

The Implications of the Letter

In any case, the event of the letter is pretty remarkable. A high-up in the Secret Intelligence Service is sending a plaintext letter to a recognised communist who has married a wireless operator known to be a Soviet agent, in the knowledge that the letter will be opened and inspected by a) the Swiss authorities, b) the German censors, c) British Censorship, and d) (probably) MI5, before the recipient reads it. For some reason, the writer gets his addressee’s name wrong, calling him ‘Charles Burton’ on the envelope, when his name is really ‘Leonard Charles Beurton’. But the introduction is ‘My dear Burton’, an astonishingly intimate parlance for an exchange between a consul and a lowly peon. One would expect ‘Dear Mr Burton’ in a formal letter, and ‘Dear Charles’ if the two were close friends, even ‘Dear Burton’, if they had been at school together, but not bosom buddies *. ‘My dear Burton’ suggests a close colleagueship in the same organisation, or a professional acquaintance of some duration. (One can track the degrees of acquaintance and intimacy between British civil servants through their correspondence, ranging from, for example, ‘Dear Vivian’, through ‘My dear Vivian’, and ‘Dear Valentine’, to ‘My Dear Valentine’, in the case of the SIS officer Valentine Vivian.) But the two were not social equals, by any stretch. Readers will recall that Beurton stated that he had become ‘on friendly terms’ with the consular official, but what is going on here?

[* Back in the nineteen-fifties, my father recited to me a jingle from his schooldays:

“He had no proper sense of shame.

He told his friends his Christian name.”

This tradition at independent schools certainly endured into the 1960s.]

Moreover, the text surely has some coded messages. “I have no doubt that the day is not far off when only the air will be available!” certainly does not look forward to the time when airline passenger service will be restored between the two countries: it must refer to the use of wireless. “Recently he became the proud father of a second daughter . . .” is probably not referring to a real birth, but is some kind of pre-arranged text to indicate that something has happened, perhaps the recruitment of a new sub-agent. (Rössler had been recruited in November 1942.) Such a formulation was a common practice for coded messages in WWII. The statement that Farrell expects to meet W’s new daughter is very revealing, however, since it suggests that Farrell has taken over Beurton’s role in associating with Wang and his links to Falkenhausen.

The second part of the sentence might otherwise have indicated that ‘W’ could be Foote, but, now that L. T. Wang has been identified, and Beurton’s friendship with him revealed, the Chinse journalist must be the prime suspect. The statement that ‘communication has deteriorated since you left’ could refer to the fact that the German entry into Vichy France in November 1942 had made the escape/route (by which couriers could carry messages to London) even more perilous and unreliable. Yet ‘W’ is a very odd way of identifying a common acquaintance in a personal letter, and the usage draws attention to the secrecy. Why would Farrell not use the person’s real name, unless it was a foreigner with dubious connections? Moreover, Farrell signs off by requesting Beurton to ‘let us know’, not ‘let me know’, thus suggesting his membership of a larger organisation.

But, again, why was Farrell communicating by letter with Beurton rather than going through Head Office? Farrell expresses disappointment that he has not heard from Beurton, and regrets that Beurton has no time for ‘private correspondence’. Yet it is a strange set of circumstances where a consular official and a communist agent would try to establish a ‘private’ exchange of letters. And the implicit references to do not suggest that these are purely personal matters.

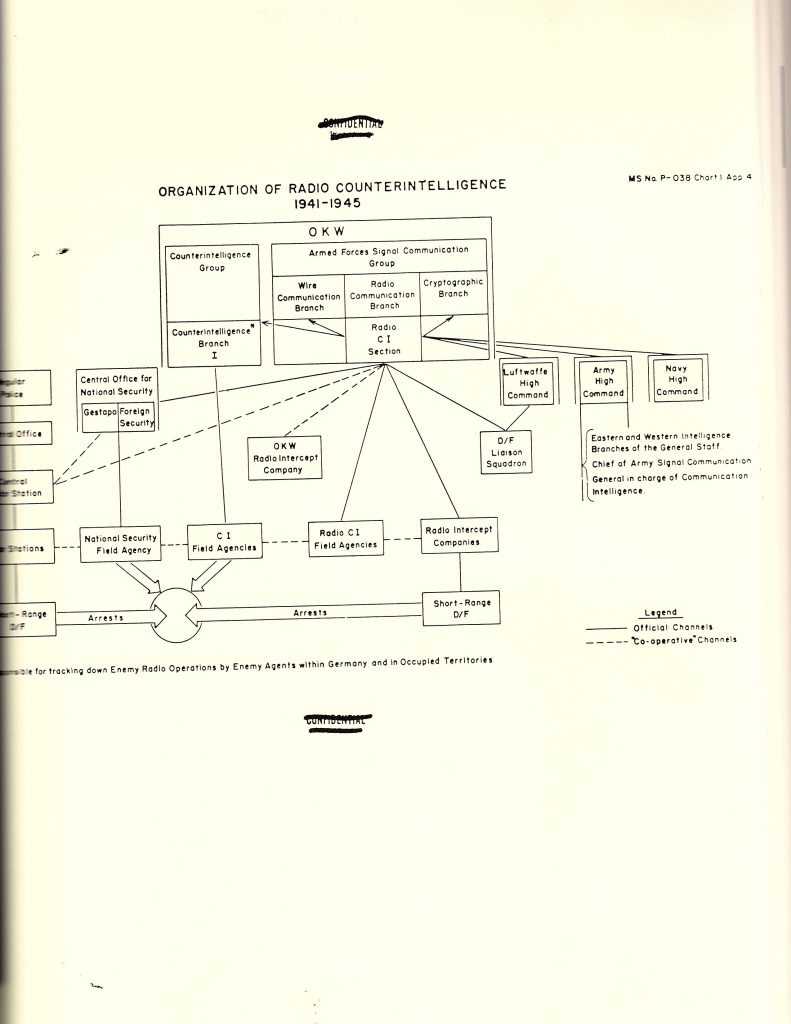

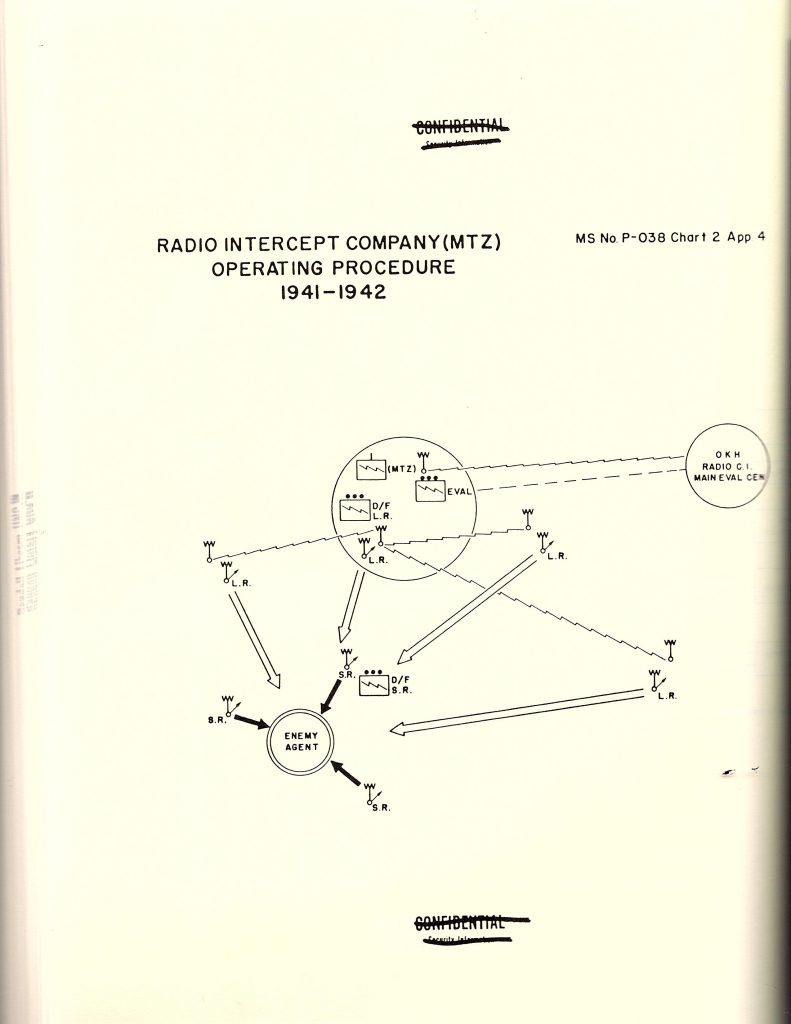

At face value, the letter makes an appeal to Beurton to contact the Geneva station by wireless. Now, although Jeffery’s History of SIS does not mention Farrell by name, it does reveal some useful facts about wireless communication at that location: “There was a SIS wireless set at Geneva, but it could be used only for receiving messages as the Swiss authorities did not permit foreign missions in the country to send enciphered messages except through the Post Office” [apparently describing the situation in 1940], adding that “These communication difficulties meant that only messages of the highest importance could be sent by cable, and that much intelligence collected in Switzerland reached London only after a considerable delay. Because of the lack of continuous secure communications, moreover, London was unable to send out any signals intelligence material, which was another handicap for the Swiss station [undated, but implicitly suggesting the period after Vichy had been closed off in November 1942].” (p 380)

Analysis

In this context, we have to take some logical steps about the context of Farrell’s letter:

First of all, irrespective of the text enclosed, it would on the surface have been extraordinarily foolish for a senior diplomatic officer, having acted as a presumably objective arbiter in a repatriation case, to enter communication with the subject in any form. Yet Farrell not only bypassed the official channels: he wrote privately, from an undisclosed address, to a distorted and hence not immediately familiar name, using an unnaturally intimate form of address, and concluding with a near-undecipherable signature. He was indisputably trying to contact Beurton about business they had discussed, but in his effort made a clumsy attempt to conceal the fact.

Second, Farrell must have known that his letter would be intercepted by both Swiss and British – and even Nazi – censors, and that the message would reach the eyes of MI5, SIS and other government organisations. Yet he did not expect the Swiss censor to be able to identify him or Beurton, or the British censor to recognize his name. Beurton was known as ‘John Miller’ to the Swiss authorities. (Beurton appeared as ‘Fenton’, the name of his adoptive parents, in MI5 files, but his identity was known to MI5 before he arrived in Britain.) The fact that German intelligence could have discovered messages that pointed to Switzerland’s possibly weakening neutrality by allowing British wireless communications could have had a very serious consequence. Yet Farrell, an experienced SIS officer, was apparently not concerned about this exposure.

Third, given what is known about Farrell’s close involvement with, and recruitment and maintenance of, Sissy Dübendorfer, and her association with the ‘Lucy’ Ring, and his presence as Passport Control Officer in Geneva at the time Sonia departed for the UK (and probably when her marriage and passport application took place), one’s first instinct is to assume that he was familiar with the SIS exercise of enabling Sonia’s marriage, and her passage to the United Kingdom. He most certainly knew about the shenanigans involved in giving Len a false identity, and oversaw the whole project. Yet he might not have known about the details of the arrangement of Sonia’s affairs, if they were arranged before he was installed in Geneva, or were handled by other officers. (Sonia describes the passport officer as being somewhat remote, as if he were unfamiliar with her recent marriage, but, again, he may have been acting so.)

Fourth, the message indicates that Farrell had received information from a third party that Beurton had arrived safely in England, and rejoined Sonia, but had clearly not been given his Summertown address. In that case, however, unless he was confident that Beurton was living alone at Kidlington, a highly unlikely supposition, he must have realised that Sonia could have picked up the letter, and opened it, or that Len would have to explain to her what the letter was about. Thus he must have believed that referring elliptically to wireless transmission was not a statement that incurred undue risk in the management of Sonia.

Fifth, if one accepts that Farrell was an experienced and respected member of Dansey’s Z organisation, and that he performed his job of consul/PCO professionally, and one finds the superficial meaning of the text absurd, one can only assume that he had an ulterior motive beyond that outlined in the letter, and was consciously drawing Len out into the open. Alternatively, because he believed the import of his message was concealed, he did not believe that anyone not part of the conspiracy would be able to detect what was going on. He surely must have gained approval from Vanden Heuvel for what he was doing.

Sixth, if receiving messages on his apparatus in Geneva was not a problem (although without confirmation of receipt, or an ability to discuss them, their value would have been diminished), trying to acquire another sender in the United Kingdom would appear to be pointless. Thus Farrell’s request only makes sense if it implies a tacit agreement that Beurton’s wireless would communicate not with the Geneva station, but with a wireless apparatus outside the consulate – presumably Alexander Foote’s, and that, in addition, Beurton would have useful information to impart. He would have been of no value as a freelancer. Thus a clandestine but official link, not so easily detectable by the Swiss authorities, but monitorable by Dansey (presumably) at one end, and Farrell at the other, would allow a two-way exchange to take place. His invitation is undeniable: the content of any such exchange deriving from it still enigmatic.

Seventh, Farrell must have considered Beurton a loyal servant to the cause, committed to helping SIS, and he must also have imagined that Beurton’s International Brigade past had been some kind of cover, or that he had changed his views, or that his Communist past was irrelevant for the current project. This was an understandable attitude to take after June 1941, but would not have been when Sonia left Geneva at the end of 1940, when the Nazi-Soviet pact was still in effect. He and Beurton shared the desire to acquire information about opposition to the Nazis: they were both interested in helping escaped POWs get to Lisbon. Farrell has apparently taken over Beurton’s role as intermediary with Wang. Thus all evidence seems to suggest that Farrell trusted Beurton. (When Skardon and Serpell questioned Beurton in the infamous 1947 encounter at ‘The Firs’, they assumed Beurton was anti-communist, according to Sonia.)

Eighth, Beurton could thus, with the Soviet Union and Great Britain as allies, presumably feel at ease with working for SIS, expressing enthusiasm for his role in returning to the UK, and managed to convince Farrell and his team that he could put his wireless operations skills to good use in a shared cause. Beurton claimed, after his return, that he had been able to help Farrell on some matters of intelligence (surely the Wang-von Falkenhausen business), something that may have facilitated the granting of his false identity. As a quid pro quo for gaining Farrell’s help on his passport, he probably made some sort of agreement with Farrell for trying to communicate with Farrell (or the surrogate) by wireless when he reached the UK – perhaps on the status of Soviet POWs – but probably did not plan to take it seriously. Farrell’s hint that he knows what Beurton is focused on (‘you are absorbed in work that so interests you’) indicates that Beurton might have confided in him some aspect of his plans with Sonia. Yet why, if Farrell had taken over Beurton’s role as intermediary to Wang, he would be expecting useful information from Beurton at a personal level now that Beurton was in England, is very puzzling.

Thus the primary enigma over Farrell’s approach stands out: was it authorised, unauthorised, or clandestine? If it was authorised, it would seem unnecessarily hazardous, as Beurton could much more easily have been contacted and influenced from London. If it was unauthorised, it would seem pointless, as Beurton would have nothing of value to offer to Farrell in Geneva, or any associate wireless operator in Switzerland, and raises all manner of questions of responsibility and secrecy. The third option is that it was clandestine, and that Farrell was also a Soviet agent or, at least, a sympathiser. Yet the foolishness of exposing his relationship with Beurton to Swiss, German and British intelligence is simply beyond belief, and Farrell’s stature as a senior SIS officer – even with what we know about Kim Philby – almost certainly would seem to exclude him from that category. Thus a more plausible conclusion is that the communication was ‘semi-authorised’: Farrell had received tacit approval for an exercise that would be denied on high if the details ever surfaced.

In this scenario, therefore, Farrell would have been treating Beurton as a potentially valuable communicant, with wireless skills, who would be able to facilitate secret, less obvious, exchange of information with Dansey in London and the Swiss outpost through its extended network, namely Foote. There was risk involved, but he must have considered that Sonia would not be perturbed by disclosure of the agreement. What information, and from what source, Beurton would have provided his contact in Switzerland is not clear. It may be coincidental that ‘Lucy’ (Rudolf Rössler) was recruited by the Swiss network in November 1942, shortly after Beurton’s arrival in Britain. Yet the case for Beurton’s being the conduit for Ultra-derived messages would appear to be weakened by the following:

- Foote had been transmitting such intelligence messages before Len’s arrival in the UK;

- Beurton, unlike Foote, would have explained to Moscow (via Sonia) the source of his intelligence, but Moscow continuously pressed for more information about ‘Lucy’;

- Even if he did not see the Ultra-based messages himself, Farrell would presumably have been aware of Beurton’s role, and thus would not have had to remind him of his obligations;

- If SIS had nurtured Beurton as an official messenger for such traffic, and trusted him, it would surely have kept him out of national service, so that he could continue his role;

- Foote would not have complained so much, after his return to the UK in 1947, about Sonia’s receiving warnings by an officer within MI5 about Fuchs’s imminent arrest.

Farrell’s Intentions: A Closer Study

If a more detailed look is taken at Farrell’s situation, enhanced by the (admittedly unreliable) memoirs of Foote and Sonia herself, one might conclude that Farrell was indeed acting in a semi-official capacity, probably with Vanden Heuvel’s knowledge, but without any formal approval from SIS in London. Consider the following reasoning:

Because of the multi-month delay since Beurton’s arrival in the UK, Farrell’s letter of March 1943 must have been prompted by some event. The likeliest candidates must be i) Beurton’s failure to do something, or ii) an unexpected happening with the Soviet network in Switzerland. Yet it is difficult to see how any of the events concerning the Rote Kapelle after July 1942 (such as Rössler’s recruitment) could have prompted the approach. The cryptic references to ‘W’, and W’s new child, would not appear to have anything to do with wireless communications. On the other hand, the progress of hostilities might have provided a stimulus: the Wehrmacht’s first major defeat of the war at Stalingrad, in February 1943, could conceivably have re-energised interest in the anti-Hitler movement. Farrell might have then tried to resuscitate a contact.

What was Farrell’s probable relationship with Beurton? His familiar mode of address shows that he had grown to know him well in the time between Sonia’s leaving (December 1940) and Beurton’s departure (July 1942). Beurton confirmed that he had provided Farrell with information and that the two had become friendly, but Sonia’s own account suggests that it was only very late in the cycle, after Cadogan’s involvement in February 1942. In Sonya’s Report, the author describes how Len’s applications to the British Consulate were brushed off since they had more urgent cases to deal with. Only after Cadogan’s letter (written February 29) did Farrell ask Beurton to come and see him, and then ‘smoothed the way for his journey’.

What was Beurton’s status? To SIS, it would probably have been safer, and more productive, for Beurton to remain in Switzerland, where he was effectively neutralized, but could provide useful information via his Chinese acquaintance, Wang. It is significant that SIS apparently made no move to accelerate his reunion with his wife. After all, they (in London) did not really know whether he was an unideological agent (like Foote), or a committed communist (like Sonia). If he was an unreconstituted International Brigader, and had enthusiastically married Sonia, SIS would conclude that he was certainly the latter. But he shared SIS’s anti-fascist mission. Moreover, Sonia relates how Len and ‘Jim’ (Foote) grew apart in 1940, as Foote became more egoistic and pleasure-loving. She notes that Foote did not become a communist until he returned from Spain. Foote writes, in Handbook for Spies, that Beurton had no further contact with the group after March 1941. He also told MI5, in 1947, that Beurton had been very critical of Radó, whom Beurton ‘hated’, and that Moscow had asked Foote to get Beurton to stop sending embarrassing telegrams to Sonia that were unencrypted.

Did the request from the UK to do whatever it could to gain Beurton’s egress come as an unpleasant surprise, or simply a bureaucratic chore? Cadogan and Eden, after pressure from Sonia and Eleanor Rathbone, had become involved. There is no evidence of SIS applying pressure, and a note from SIS to Vesey on file reinforces the fact that the PCO in Geneva knew nothing of Beurton’s shady past beforehand. (It would say that, of course. It would not have been wise for SIS to admit to Cadogan and Eden that they had been employing known Communists for clandestine work.) So why would such high-ups agree to support the case of one single dubious citizen? It seems an inordinate amount of effort to gain the repatriation (and airplane flight home from Lisbon) of a highly dubious and subversive character, who was, moreover, on the C. S. W. (‘Central Security War’) Black List, and thus considered officially an undesirable. Sonia had also been placed on that list before her arrival.

One suggestion, put to me by Professor Glees, is that Beurton may have been recruited as an SIS agent before his marriage to Sonia, in a fashion similar to the method Foote indeed had been (according to my theory), and was instructed to marry her to facilitate her passage to the UK. In this role, his task would have been to keep an eye on Sonia, and he thus would have been sent to the UK to fulfil this mission, but reporting to Farrell via personal letter, and then wireless, rather than to London. This is a very dramatic hypothesis that must not be excluded, but it does raise questions about Beurton’s true commitment, and whether he never really switched allegiances, but acted along with SIS as far as he could. While Alexander Foote was an adventurer, of pliable political convictions, Beurton had been a dedicated communist for years, having joined the CP in Spain, and openly transferred to the CPGB on his return. Moreover, we have to face the fact that Beurton showed intense loyalty to Sonia, and followed her to East Germany in 1950, soon after she and their three children escaped, where they apparently lived happily together. According to Sonia, Beurton worked in a dedicated fashion for the German Democratic Republic for twenty years.

However, after Len’s departure, Farrell (and Heuvel, presumably) did nothing for eight months. If they had divulged anything confidential to Beurton, they must have known that, as soon as Beurton arrived in Oxford, he would tell Sonia about the set-up in Geneva, and what discussions he had had with Farrell. Did Farrell let Beurton know about the infiltration of the Rote Kapelle network (by Foote and Dübendorfer)? Surely not, otherwise Foote would have been blown. (Although Radó knew that Foote had friends in the British Embassy.) Foote underwent strenuous interrogation in Moscow after the war, and was absolved. Sonia admits she did not mistrust Foote in 1940, even when the breach with Beurton occurred. Again, that may have been an insertion required by the GRU, but the latter allowed Sonia to describe Foote’s innate humanity in warning her to leave the country well before Fuchs’s arrest.

What did Sonia do in the weeks/months following Beurton’s return? The most significant is being set up, with Moscow’s approval, to meet Fuchs (although some accounts suggest she met him earlier). Did she get the all-clear because Beurton returned from Geneva? Thus Moscow could not have been alarmed by anything Beurton reported. Maybe she received the go-ahead on the basis that her husband was in place to transmit her messages. Meanwhile, Dansey and Menzies must have breathed a sigh of relief that nothing outwardly changed after Beurton’s arrival. There were no alterations in behaviour, and Sonia clearly believed she could transmit undisturbed.

Farrell’s informal approach to Beurton therefore only makes sense if either a) Farrell had not been personally involved with Dansey in the scheme to manipulate Sonia, and had been delegated with merely formal tasks to facilitate her passage only, or b) Beurton was now a recognized SIS agent, and Farrell was his controller. Sonia presents the request for a passport as a surprise to the British Consul in Geneva, as if he had no knowledge of the marriage itself. (“His response was distinctly cool.”) Farrell’s primary focus was on escape lines – as was that of Beurton, who was tasked by Moscow with trying to get escaped Soviet prisoners-of-war out of Switzerland. Farrell knew Beurton and Foote were (or had been) friends. Farrell must have had broad sympathies with anti-fascist activities, and believed Sonia’s story that she had abandoned any Soviet espionage because of her disgust with the Nazi-Soviet pact (a claim Sonia makes in her book, and one that is conveniently echoed in Foote’s Handbook for Spies, where it suited MI5 to indicate that Sonia’s disillusionment meant that she had given up spying).

A plausible explanation is that Beurton thus made some deal with Farrell concerning liaison with his (former) friend Foote, but did not take it seriously, as he considered he had duped Farrell, and thus did nothing about it on his return to the UK. If he had been recruited to keep a watch on Sonia, he would surely have passed on some worthless details to keep his legend alive, rather than do nothing at all. Beurton turned out to be a highly mendacious character, inventing all manner of stories to mislead the authorities about his travels, and his source of funds, but suddenly expressed a sense of entitlement when SIS aided his return to the United Kingdom

The conclusion must be that Farrell made an unofficial approach to Beurton, reckless in its poorly veiled language, but that all the authorities astonishingly failed to note its import, with the result that no strategies were derailed. Yet the existence of the Geneva letter shows a degree of connivance with the Beurton/Sonia axis that has been ignored by those who claim that SIS had no part in masterminding Sonia’s escape.

Conclusions

Farrell: On the most probable assumption that Farrell was acting without overt higher authority, the implication of his action is that a high degree of naivety must be ascribed to him and Vanden Heuvel, because, irrespective of their degree of trust in Beurton, and his exact mission, they must have realised that Beurton would immediately inform Sonia of what was happening. I am of the opinion that Sonia probably guessed in 1940 that SIS was trying to manipulate her, because of the chain of events that led to her arrival as a free Englishwoman in war-struck Britain in January 1941, but Len’s arrival eighteen months later, if he divulged any secret agreement with Farrell, would have immediately confirmed that everything they did was presumably under surveillance. And that fact has enormous implications for Sonia’s career in espionage after that date. Moreover, Farrell appears to disappear from the picture after this episode

Beurton: And how was Beurton to handle this fresh requirement made on him? Farrell expects him to have made contact with him since his departure, although perhaps not immediately by ‘air’. Is that an evasion, a subtly coded wish that he should have communicated by wireless by now? Beurton apparently did not hear from Farrell for eight months. Maybe he thought that, without a firm agreement on schedules, frequencies, callsigns, etc., or even knowledge of the capabilities of any wireless transmitter he might acquire or construct, he could safely avoid trying to make wireless contact with Farrell. But what about Dansey and SIS? If Farrell’s approach to Beurton had been authorized by Vanden Heuvel, but not by Dansey, it would explain why Dansey and his minions did not discreetly try to ensure that Beurton was following up. But Beurton’s status in the whole drama is now elevated: Soviet wireless operator, confidant with connections to the opposition to Hitler, clandestine communicant with – or even agent of – SIS, and decoy for an important Soviet spy.

Sonia: One of the most significant conclusions must be that, if Farrell had tried to open a communication channel with Beurton, Sonia would have known about it as well. And, even if she knew nothing of the programme to manipulate her, the realisation that SIS was aware of Len’s capability for using wireless in the UK would make any attempt by her to perform clandestine transmissions pointless. The only other explanation would be that Sonia had left for the UK as a compliant accomplice in some disinformation exercise towards the Soviet Union, and went along with it, while all the time planning to pursue courier activities of which SIS was unaware (i.e. meeting with Fuchs). That hypothesis is unlikely, but not outrageous. I would not discard it immediately, and offer a possible scenario as to how it might have rolled out.

It is quite possible that SIS, having abetted Sonia’s marriage, then threatened her, when she applied for a passport, that they would reveal her subterfuge and return her to a probable death in Germany unless she agreed to work for them. The motive here would be to learn more about Sonia’s contacts, feed her disinformation, and, by using her transmissions as a crib, acquire clues to Soviet ciphers and codes. Sonia would have gone along with this scheme, of course, and, once she was in the UK, would have had to cooperate for a while. Yet, a ‘double agent’ (which, strictly speaking, she would not have been) cannot be relied upon unless his or her handler has exclusive control of the subject agent’s communications. Sonia would have alerted her true bosses of the situation via her brother and his conduit to the Soviet Embassy, and Military Intelligence would have adjusted plans and expectations accordingly.

Sonia & Len: In that temporary twilight world, the outcome would be that Sonia would have had to stifle her own transmissions (or deliver completely harmless messages, to fool her surveillers), and that Len would have managed to deceive or shake off his would-be SIS controllers, and transmit to the Soviet Union (or the Soviet Embassy) until he was called up for national service. While Len’s actual role with SIS remains very murky, Sonia may then have turned to couriers and the Soviet Embassy for delivering her intelligence from Fuchs.

The exploits of Sonia and Len in going to Switzerland, later escaping from there to the United Kingdom, and then surviving in Britain undetected, are so packed with incidents of unmerited good fortune, complemented by a massive series of untruths declared to immigration officers and others by the married pair, that one can come to only one reasonable conclusion: they were remarkably stupid, or they were abetted by an extraordinarily naïve British intelligence organisation. And, if they were allowed to get away with such obviously refutable false claims, they must have themselves concluded that the opposition was either simply incompetent, or believed that it could manipulate them without it’s being suspected. I shall cover the whole farrago of lies in a future piece.

SIS: The inescapable fact is that the existence of the letter proves that SIS was trying to manipulate Sonia (and Len), in a futile effort to control her broadcasts, and learn more about Soviet tradecraft and codes. What the letter and the surrounding information on file show is that, contrary to earlier analyses, which have focused on MI5’s negligence in not detecting what Sonia was up to, and thus allowing her to operate as a courier scot-free, is that MI5’s senior officers were colluding with SIS and allowing her to operate without hindrance. Beurton’s arrival caused a worrying flurry of unwanted interest from an eager junior in F Division (Shillito) at a time when B Division had studiously been ignoring her activity and movements. Ironically, Beurton was at this time, in 1942 and 1943, the probable real wireless operator transmitting Sonia’s messages, while Sonia was able to roam around with MI5 casually ‘keeping an eye on her’. All the time, however, she was able to distract her surveillers from the main illicit activity. Sonia outwitted both MI5 and SIS.

The pattern in KV 6/41 reinforces the major theme of ‘Sonia’s Radio’ – that SIS developed a scheme to place Sonia in a position where she would be encouraged to spy for the Soviets, but where her every move would be known to the Secret Intelligence Service. In order to execute this plan, SIS had to gain the co-operation of senior MI5 officers, who were responsible for the surveillance of possible threats, whether German or communist, on home soil, so that Sonia’s life would not be interfered with. Every time a junior officer pointed out Sonia’s background and communist ideology, or her connections with strident rabble-rousers like her brother, that officer was quashed, and instructed to lay off. Yet the corporate discomfort was obvious: in one very telling detail from after the war, the same John Marriott who worked for the Double-Cross operation in B1A, and then returned to communist counter-espionage in F Division as F2C (Shillito’s old job), wrote to Kim Philby of SIS on April 15, 1946. The FBI had contacted MI5 wanting information about Sonia in relation to her husband Rudolf Hamburger, who had been captured in Tehran, and the FBI wanted MI5 to question Sonia. Marriott wrote to Philby: “For a variety of reasons I do not feel able to comply with this request . . .” Indeed.

Postscript

I wonder whether any readers can help with the following questions:

- What was the staff organisation in the Geneva consulate from 1939-1943?

- Who were the owners of the bungalow in Kidlington, and did they really eject the Beurtons and move in?

- What route did mail from Switzerland to the UK take in 1943?

- What other interpretations might one place on the message in the letter?

- What was Beurton’s exact role supposed to be in making wireless contact with Switzerland?

- Can anyone point me to details of Falkenhausen’s activities in the first years of the war?

As with all these intelligence mysteries, one has to believe there exists a logical explanation – unless, of course, the archival record itself is fallacious. One has to assume that each agent in the story was acting in the belief that what he or she did was in furtherance of his or her own interests, or those of their employer. The Geneva Letter is in the same category as the memorandum on Guy Burgess’s going to Moscow to negotiate with the Comintern, or the report from the Harwich customs officer querying Rudolf Peierls’s passport, or Dick White’s instructions to Arthur Martin to brief Lamphere on Philby. A convincing explanation will eventually be winkled out.

[I thank Professor Anthony Glees, Emeritus Professor of Security and Intelligence Studies at the University of Buckingham, and Denis Lenihan, distinguished analyst of intelligence matters, for their comments on earlier versions of this report. Professor Glees came to Roger Hollis’s defence in ‘The Secrets of the Service’, and can safely be described as a supporter of my theory that SIS manipulated Sonia: Mr Lenihan is overall a supporter of Chapman Pincher’s claims in ‘Treachery’ that Hollis was the Soviet mole ELLI, and is sceptical of the SIS-Sonia conspiracy theory. Neither gentleman has endorsed my argument, and any errors or misconceptions that appear in it are my responsibility alone.]