Who Framed Roger Hollis

Coming soon to a movie-theatre near you, starring

Donald Pleasance as Stewart Menzies

Tom Cruise as Kim Philby

Ronald Fraser as Roger Hollis

Bob Hoskins as George Hill

Anthony Hopkins as Guy Liddell

Ian Richardson as Dick White

Keira Knightley as Jane Archer

Beryl Reid as Milicent Bagot

Michael Caine as Peter Wright

Tom Courtenay as Arthur Martin

Vladek Sheybal as Igor Gouzenko

Christopher Plummer as Chapman Pincher

With a special guest appearance from Lotte Lenya as Luba Polik

‘It makes Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy look like Dad’s Army’ (Michel Foucault)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Contents:

1. The Story So Far and Dramatis Personae

2. Anomalies and Misconceptions:

a) The BSC Report and Roger Hollis

b) Peter Wright and VENONA Telegrams

c) Guy Liddell and the RCMP

d) Roger Hollis and Counter-Espionage

3. Background Clarification:

a) Stephen Alley

b) George Hill

c) George Graham

4. Guy Liddell’s Moves:

a) Petrie and Sillitoe

b) Security Issues

c) The Voyage to the Americas

5. Conclusions:

1. The Story So Far:

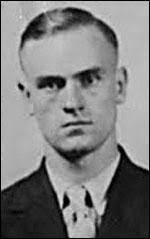

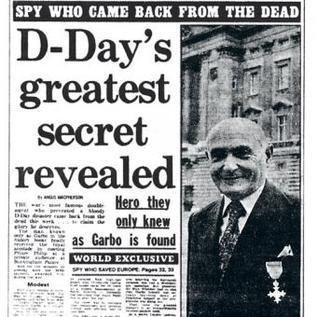

In September 1945, a Soviet GRU (military intelligence) cipher-clerk, Igor Gouzenko, defected in Ottawa, bringing with him evidence of espionage in Canadian government institutions. William Stephenson, the head of British Security Coordination, the wartime intelligence unit in the United States, immediately took a keen interest in the matter. For various reasons, the growing news about Gouzenko’s revelations arrived in London at the desk of Kim Philby of MI6, who alerted his Moscow bosses via his handler, Krotov, and passed on the information with less than urgent dispatch to his colleagues in MI5. While the initial concern of MI5 was about the imminent departure for London of Alan Nunn May, the premier spy named by Gouzenko, the Security Service was also interested in the identity behind another person labelled as ‘ELLI’. ELLI was stated to have been a spy working within the intelligence services in the UK in 1942 or 1943, and had been revealed by Gouzenko’s colleague in Moscow at the time. MI5’s Roger Hollis, responsible for the surveillance of domestic subversives such as the Communist Party of Great Britain, returned from holiday to be sent immediately to North America to co-ordinate the handling of the Nunn May case, and the political fall-out from the defection. At the time he left, he almost certainly knew nothing of ELLI, and he did not see Gouzenko before returning after a couple of weeks. Meanwhile, Guy Liddell, head of B Division, responsible for Counter-Espionage, ruminated on the possible candidates for ELLI, concluding from the meagre descriptions received thus far that he probably had been associated with SOE, the Special Operations Executive. During the period in question, SOE had had a representative in Moscow, George Hill, and it liaised with the NKVD representative in London, Colonel Chichaev. Roger Hollis returned to the Americas, and had a short interview with Gouzenko in November. Liddell then discussed possible security exposures with Archie Boyle, who had been head of Security for SOE during the war. Politicians dithered about detaining and prosecuting the suspects, not wanting to upset Stalin.

Dramatis Personae (status in November 1945, unless otherwise indicated):

Government:

Attlee UK Prime Minister

Dalton Chancellor of the Exchequer: Minister for Economic Warfare 1940-42

Bruce Lockhart Deputy Under Secretary of State, Political Warfare Executive 1941-45

Findlater Stewart retired: previously Chairman of Home Defence Executive

Mackenzie King Canadian Prime Minister

Robertson Canadian Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

MI5:

Petrie Director-General (retired April 1946)

Sillitoe Director-General (appointed November 1945)

Harker Deputy Director-General (retired 1946)

Liddell Director of B Division

White Deputy-Director, B Division

Curry historian: previously Director of F division, then transfer to MI6

Hollis (Assistant) Director of F Division (Subversive Activities0

Alley E2 (Alien Control of Finns, Poles & Baltic States)

Rothschild B1C (Sabotage)

Blunt B1B (Diplomatic)

Wright joined in 1954

Orr Room 055, War Office

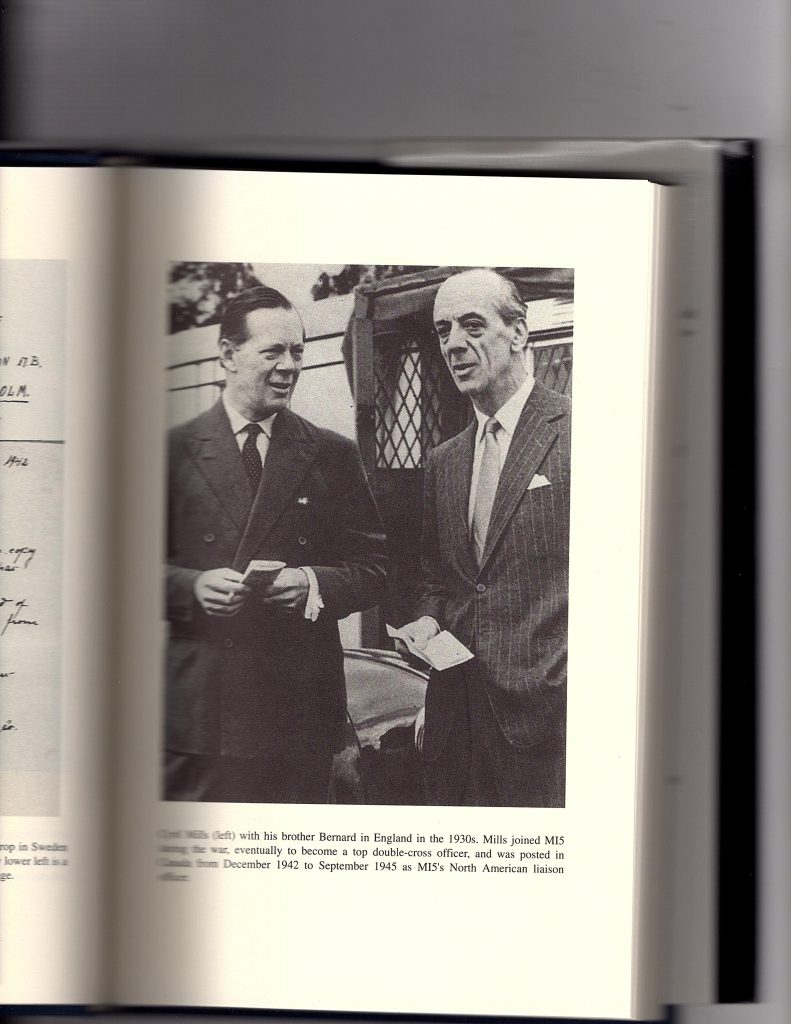

Mills Canadian representative: demobilized September 1945

Shillito F2B & F2C (Communism & Left-Wing Movements: retired August 1945)

Bagot F2B

Stewart active in 1972

MI6:

Menzies Chief

Cowgill head of Section V: retired in 1944

Philby head of Section IX

Archer Section IX (returned to MI5 in 1946)

Curry established Section IX in 1943: moved back to MI5

Dwyer representative in BSC

De Mowbray joined in 1950

SOE (Special Operations Executive):

Nelson chief 1940-42

Hambro chief 1942-43

Gubbins chief 1943-46

Senter MI5 liaison

Boyle head of security

Hill Russian section representative in Moscow until May 1945

Graham aide-de-camp to Hill

Truskowski assistant to Hill

Seddon head of Russian section 1941-44

Manderstam head of Russian section 1944-45

Uren officer, spy; imprisoned

JIC (Joint Intelligence Committee):

Cavendish-Bentinck Chairman

GCHQ:

Sudbury Russian cryptanalyst

RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police):

Wood Commissioner

Rivett-Carnac head of intelligence (Commissioner 1959-60)

Gagnon deputy Commissioner

Harvison head of Criminal Investigation (Commissioner 1960-63)

Leopold deputy to Rivett-Carnac; first translator; chief of Intelligence Branch (October 1945)

Black second translator

McLellan Inspector (Commissioner 1963-67)

BSC (British Security Co-ordination):

Stephenson head

Dwyer MI6 representative: head of MI6 station (1945)

Evans colleague of Dwyer

FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation):

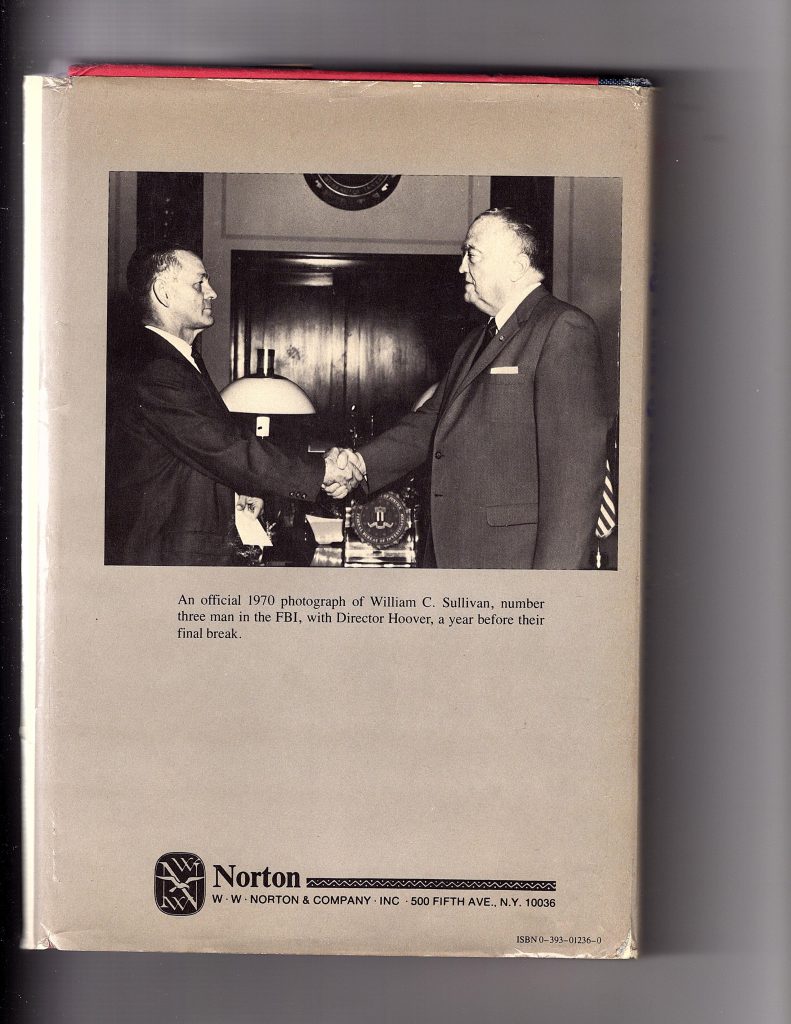

Hoover Director

Harvey counter-intelligence (moved to CIA in 1947)

Whitson expert in communism

Lamphere agent: espionage expert

OSS (Office of Strategic Services) & CIA (Central Intelligence Agency):

Angleton OSS counter-intelligence (chief of CIA counter-intelligence 1954)

GRU (Soviet military intelligence):

Zabotin Colonel, military attaché & head of station, Ottawa

Gouzenko cipher clerk

Kulakov cipher clerk

NKVD (or KGB, Soviet Security):

Ossipov Major-General, liaison to SOE in Moscow (Ovakimyan)

Chichaev [JOHN], Colonel, liaison to SOE in London (1941-45)

Krotov [BOB], controller of Philby (Krötenschield)

Gromov [VADIM], rezident in Washington since 1944 (Gorsky)

Kukin [IGOR], rezident in London, replaced Gorsky in 1944

Pravdin [SERGEY], officer in Washington (Abbiate)

Poliakova Lieutenant-Colonel (on loan from GRU)

Polik manager at the National hotel in Moscow

Journalists:

Worthington Toronto Sun

Picton Toronto Star

Pincher Daily Express

2. Anomalies and Misconceptions:

My overall approach has been to step through these events in strict chronological sequence. Judging from some of the feedback I received after my first instalment, however, I sense it will be useful to comment on some of the anomalies and misconceptions that have been published, and echoed, in recent accounts of the Gouzenko affair, in order to crystallize how the events of 1945 have been consistently misrepresented. [With the goal of improving the independent coherence of this piece, I re-present some material from the previous article.]

a) The BSC Report and Roger Hollis:

One dominant story that has entered the mythology is that of Roger Hollis’s reputed interference in the investigation by creating a false trail. For example, Amy Knight, in her 2005 book How The Cold War Began (which is frequently cited as the ‘standard’ work on the subject), writes (p 237): “Gouzenko’s information about ‘Elli’ was first conveyed during his interview with MI5’s Roger Hollis (with the RCMP present), who visited Gouzenko shortly after the defection. According to the report from the British Security Coordination, written in mid-September 1945, presumably after Hollis’s visit,

Corby [the codename for Gouzenko] states that while he was in the Central Code Section [in Moscow] in 1942 or 1943, he heard about a Soviet agent in England, allegedly a member of the British Intelligence Service. This agent, who was of Russian descent, had reported that the British had a very important agent of their own in the Soviet Union, who was apparently being run by someone in Moscow. The latter refused to disclose his agent’s identity even to his headquarters in London. When this message arrived it was received by a Lt. Col. Polakova who, in view of its importance, immediately got in touch with Stalin himself by telephone.”

Knight, rather mysteriously, here gives the source of this statement (from ‘the BSC Report’) as ‘Intelligence Department of the Red Army in Ottawa’, p 30. (On page 60, she indicates that that was actually the title of the BSC report.) The text is exactly the same as that identified by William Tyrer as coming from the Canadian National Archives, and Tyrer assumes that the message is numbered serial 2a in ELLI’s Personal File in London (as a reference to such a posting, but not the note itself, appears, in KV 2/1420, immediately after a September 15 report on the NKVD).

Yet Knight seems not to have inspected the archives in a disciplined fashion, instead relying too heavily (for example) on the account of Hollis’s activity provided by Dick White to his biographer, Tom Bower. She describes Hollis as MI5’s ‘point man’ for the Gouzenko case, and quotes Bower (The Perfect English Spy, pp 79 & 80) as follows: “MI5’s communist expert flew to Canada to meet Gouzenko on the shores of Lake Ontario”, adding: “Instead of tickling Gouzenko’s vanity and absorbing lessons about Soviet intelligence techniques, Hollis abruptly left the defector after just one hour and flew back across the Atlantic to chase Nunn May, now living in London.” As I shall show, this is pure fantasy. Knight’s ‘presumably’ reflects pure speculation.

Knight then inserts another observation, concerning an interview on October 29, conducted by the RCMP, and recorded only in handwritten notes, at which Gouzenko ‘elaborated’ on his story (p 238). He said (of ELLI) that it was ‘possible he or she is identical with the agent with a Russian background who Kulakoff [Kulakov, Gouzenko’s successor, who had recently come from Moscow] spoke of – there could be 2 agents concerned in this matter’. Knight’s account continues:

Corby handled telegrams submitted by Elli . . . Elli could not give the name of the [British] agent in Moscow because of security reasons. Elli [was] already working as an agent when Corby took up his duties in Moscow in May 1942 and was still working when Kulakoff arrived in Canada in May 1945. Kulakov [sic] said agent with a Russian connection held a high position. Corby from decoding messages said Elli had access to exclusive info.

This is presented as an extension of Hollis’s account of his interview with Gouzenko.

The significance of these claims becomes apparent when Knight later turns to the later re-investigation of the ELLI story on page 243. She reports on the visit by Patrick Stewart of MI5 to Canada in the autumn of 1972. Armed with ‘the notes of the initial debriefing of Gouzenko’, which the RCMP had generously just handed to him, Stewart met the defector in Toronto, showing him a copy of the BSC report, as well as the notes from his interview with the RCMP shortly thereafter, ‘both of which had Gouzenko saying Elli was working in British Intelligence, MI6, not counterintelligence, MI5’. Knight then states:

“Gouzenko went into a fury and threw the papers across the room. He claimed that he had not said what was written in the BSC report, that someone had falsified his statements. As for the notes of the RCMP interview, which were in the handwriting of the translator, Mervyn Black, Gouzenko said they had been forged. He demanded, to no avail, that he be allowed to take the notes home so he could compare them with his copies of Black’s handwriting.”

Knight’s explanation for this outburst is that Gouzenko had been disappointed that the officer who interviewed him in September 1945 had granted him only a few minutes of his time, and did not seem interested in ELLI. When he later learned of that officer’s identity (Hollis), and that Hollis was suspected of being a mole, he believed that Hollis must have deliberately misrepresented his statements to conceal the fact that he was ELLI.

Knight was also basing her narrative on a 1984 compilation by John Sawatsky titled Gouzenko: The Untold Story. Chapter 20 of this book is titled The MI5 Interview, and various journalists, lawyers, broadcasters contributed to the investigation. These persons appear to confirm the following ‘facts’: an unnamed British fellow interrogated Gouzenko shortly after his defection; the meeting was brief; Gouzenko was asked very few questions, and he did not see the interrogator again; the Briton shielded his face; Gouzenko had identified a mole in British Counter-Intelligence [MI5]; Gouzenko was shown a thick report in the early 1970s by a different man from British intelligence; Gouzenko threw the report across the room as it contained ‘all lies’; Gouzenko had asserted that the British could not have a high-ranking mole in the Kremlin, ‘not when Philby was sitting as head of MI6’.

Several aspects of Knight’s account are very tangled. The story that she appears to tell all derives from her strong belief in Hollis’s meeting with Gouzenko in mid-September, and runs as follows, with my commentary in parentheses:

i) When Stewart arrived in Toronto, the RCMP showed him notes of the original debriefing of Gouzenko. (Why only then? Had MI5 never seen them before? How did they correspond to the reports sent over by Dwyer? Did they concern just a single debriefing, and in what way was it ‘original’? Knight suggested that the RCMP debriefing(s) occurred after the BSC interrogation.)

ii) Stewart showed Gouzenko ‘a copy of the BSC report and the notes from his interview with the RCMP shortly after’. (What was the ‘BSC report’? According to Knight, it was the account of the September meeting where Hollis was present. She confirms that the BSC report had been written ‘in mid-September’: yet she knew that Hollis did not fly out until September 16. Elsewhere (p 60), she describes it as having been written by Evans and Dwyer, and that it was based on interviews with Gouzenko and an analysis of his documents (C293177, September 23). Moreover, in a message from London on October 1, after his return from Canada, Hollis informed the RCMP that MI5 had made ‘an extra copy of the interim report produced by EVANS and also of the additional pages I brought back’, apparently confirming Evans’s authorship, and that he, Hollis, was only the messenger (see KV 2/1412, sn.31A). And were ‘the notes from his interview with the RCMP shortly after’ the record of the October 29 meeting, or did they correspond to the ‘additional pages’ that Hollis brought back at the end of September? She does not say.)

iii) Gouzenko introduced the name of ‘ELLI’ when he spoke to Hollis in mid-September. (Knight appears adrift over this issue on two counts. She confuses references to an as yet unnamed agent with a later example of direct usage of that name, and she presents a muddled story about when that latter event occurred. The first citation above – where ELLI is not mentioned – is echoed on page 238, where she states that Hollis reported allegations about ELLI, ‘which is why they appeared in the BSC report’, after his ‘first’ meeting with Gouzenko, allegedly in September. She later quotes the RCMP report (above) of October 29, where Gouzenko talked about ELLI. Elsewhere, however (on page 62), Knight states that ‘ELLI’ was first recorded in a November 1945 RCMP report. She then (page 238) refers to Hollis’s ‘second’ meeting with Gouzenko (in November), and then implies that Liddell responded at that time by looking into the ELLI matter, and sent a telegram to Ottawa about possible identification. Yet she notes that this telegram was dated September 23! It is an unpardonable mess.)

iv) Hollis spent an hour with Gouzenko (at Camp X) before flying back to London. (This flies in the face of what Gouzenko claimed about the shortness of Hollis’s interrogation, which lasted ‘three minutes’, according to John Picton’s testimony in Gouzenko; The Untold Story. Camp X was a long way from Ottawa, and Gouzenko was not moved there until late October. Hollis’s interrogation at the end of November was indeed short.)

v) The main message from these reports was that ELLI was working in British Intelligence, MI6, not Counterintelligence, MI5. (This is not only incorrect factually, but inherently useless – a false contrast. Both MI5 and MI6 had counter-intelligence sections. In 1945, MI6’s counter-intelligence capabilities were stronger than MI5’s. Besides, Hollis’s report of November said no such thing. Interestingly, Genrikh Borovik, in The Philby Files, recorded that Gouzenko’s revelations pointed to a spy within SIS (MI6).)

vi) Gouzenko then went off the deep end, claiming that he had never said what was written in the BSC report, and that the statements were falsified. (Without knowing the exact text provided by Stewart, it is hard to inspect Gouzenko’s objections, but if the challenge was over the denial of the statement about a spy in Moscow, he was apparently wrong. The passage that Knight cites corresponds to what is available in the Canadian Archives, confirming that Gouzenko himself introduced this information. Yet I should note that, in his May 1952 testimony, Gouzenko made no reference to the existence of spies in Moscow, thus giving the denial from the Sawatsky book some merit.)

vii) Gouzenko challenged the notes of the RCMP interview ‘which were in the handwriting of the translator, Mervyn Black’, but he was not allowed to take them home to compare them with his copies of Black’s handwriting. (Black was most certainly not the translator at the time of the RCMP interrogation(s). Was this a simple mistake, with Stewart unaware of John Leopold’s role, and thus innocently misrepresenting the authorship? Or did Black’s name appear as the signatory, and had it been provided by MI5, in the belief that Black had been the translator in September, which would indicated dirty dealings?)

And what would Gouzenko have known about Philby in 1945? Of course Philby was never ‘head of MI6’, and he had a fairly junior role in MI6 in 1942-43. Gouzenko’s comment shows some retrospective imagination that failed to refute what he was claimed to have said at the end of the war. Sadly, Knight did not analyse any of these conundrums, but the distortions have reinforced some highly dubious mis-statements about the Gouzenko interrogations.

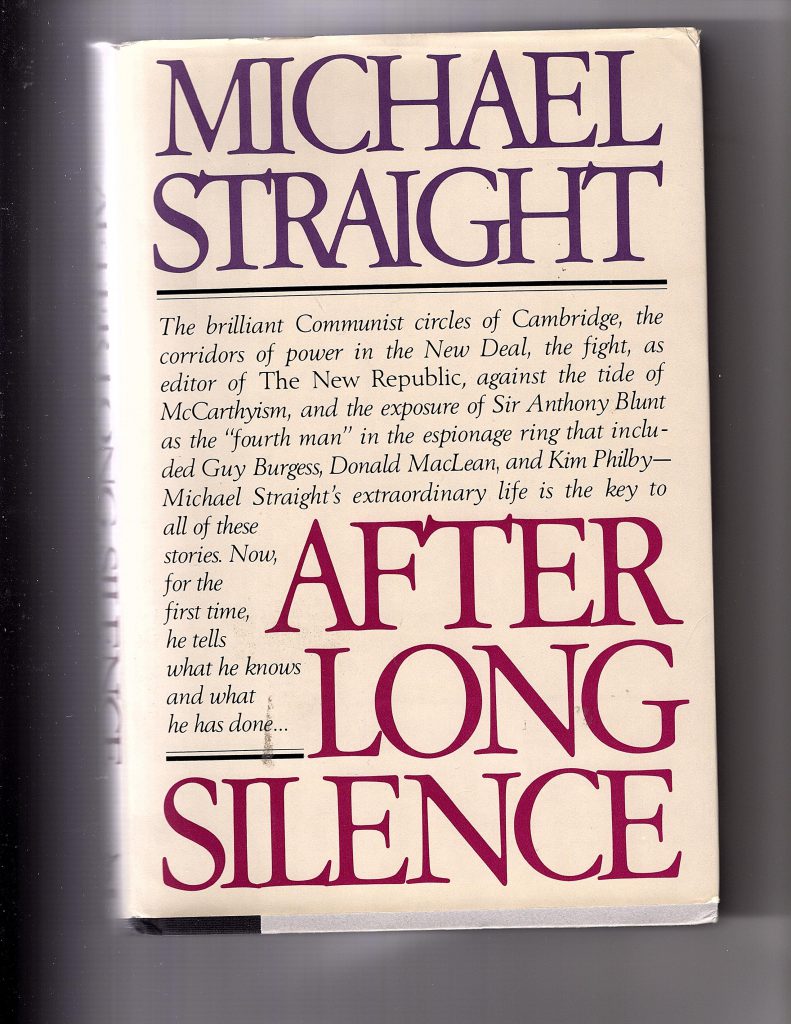

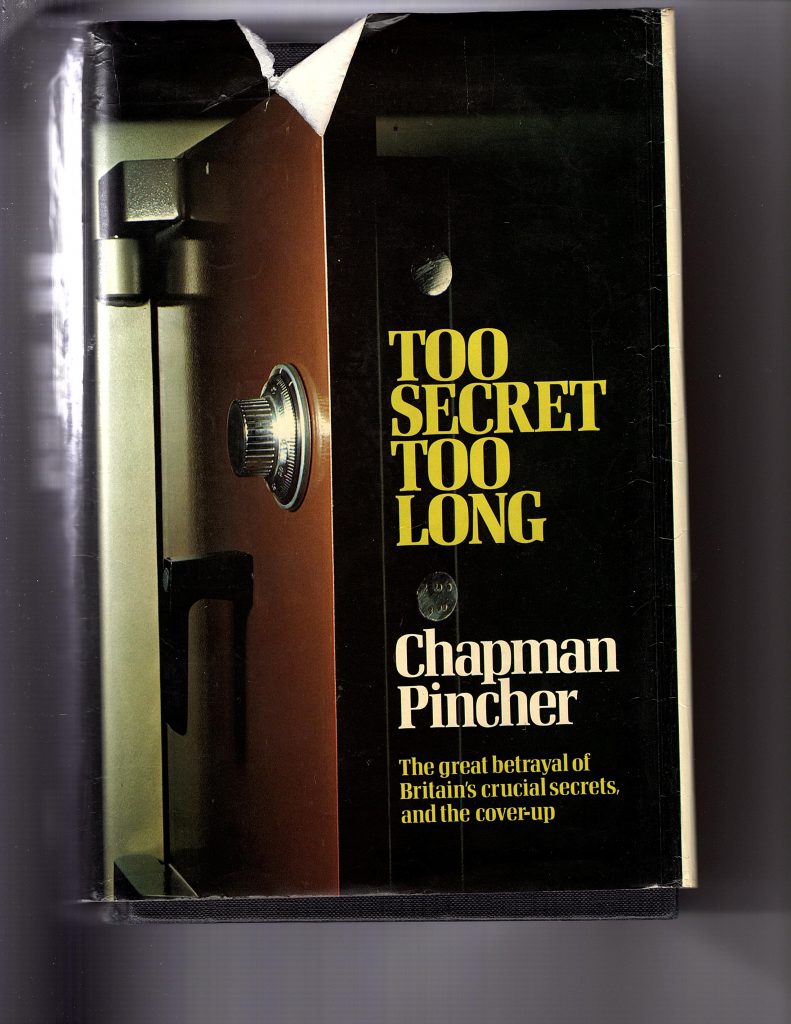

For example, Chapman Pincher echoed Knight’s story faithfully in order to solidify his case against Hollis (p 243 of Treachery, where he reprised the account he had first laid out in Their Trade Is Teachery). Gouzenko was shown ‘a substantial typewritten report that was allegedly Hollis’s account of his original interview’, including the claim about a mole in the Kremlin, he claimed. (This assertion would again fly directly in the face of the accusation that Hollis held only a peremptory interview with Gouzenko.) Pincher continued: “Gouzenko said that the document attributed other false statements to him guaranteed to discredit him as a witness and create the impression that he was unreliable. He told Peter Worthington, then editor-in-chief of the Toronto Sun, ‘whoever wrote that report about a fake interview had to be working for the Soviets’. Worthington put his account on record in a letter to The Spectator on 2 May 1987.”

Earlier, even Nigel West (who favoured Graham Mitchell rather than Hollis as the mole known as ELLI) had got in on the act. In A Matter of Trust (1982), West had rather imaginatively written that William Stephenson had facilitated Gouzenko’s extrication to Camp X: “Here, on the outskirts of the town of Oshawa, Gouzenko was interrogated at length by Stephenson, Hollis, and the Mounties” – an assertion wrong on at least three counts. Later, without providing any sources, West described, in his 1987 book Molehunt (p 79), Patrick Stewart’s visit to Toronto, with Stewart, in the presence of three armed RCMP officers, reading Gouzenko a copy of Hollis’s original report [sic] dated September 1945. “Gouzenko denounced the report as a fabrication,” wrote West, “and insisted that the remarks attributed to him by the author were bogus and had been manufactured with the intention of discrediting him. When asked about the authenticated signatures, Gouzenko insisted that they were forgeries.” West then openly wondered whether the report represented more evidence of the duplicity of DRAT [the codeword for the mole], or simply constituted additional proof of Gouzenko’s paranoia.

Again, in Gouzenko: The Untold Story, the contributors (including Gouzenko’s widow, Svetlana) appeared to corroborate the assertion that the Stewart package was a forgery, clumsily assembled, and something of an embarrassment to the RCMP officers who attended the meeting. Svetlana Gouzenko declared that the report had been pasted together from several separate documents, with inconsistent handwriting. She and Igor had suspected that the words in Black’s handwriting, confirming that Gouzenko had made such and such a statement, were not his, and that is why they wanted to compare the document with what they had at home. She was supported in her objections by the reporter John Picton, who described how the Mounties snatched the report back from Gouzenko. All this gimcrackery was later ascribed to Hollis’s malevolence.

The arrival of Molehunt provoked a lively review by the author’s ex-employer Richard Deacon in The Spectator, and a correspondence to which the journalist Peter Worthington (as noted by Pincher, above), and others, contributed. Deacon attempted to debunk the ‘guilty Hollis’ theory on the basis that i) the allegation about a mole in MI5 did not come up until a much later cross-examination of Gouzenko by the RCMP; ii) Norman Robertson, the Canadian permanent secretary for foreign affairs, came to London after Gouzenko’s defection, and briefed the heads of MI5 and MI6 on Gouzenko’s revelations, so Hollis’s obstructions would have been pointless; and iii) while Hollis was in Ottawa at the time of Gouzenko’s first interrogation, he spoke no Russian, and Nicholson of the RCMP (who was fluent in the language) conducted the interrogation. (The introduction of Nicholson has not apparently been endorsed by any other writer. Deacon’s ramblings did not help in any elucidation.)

This review prompted a spirited riposte by Worthington, who was convinced of Hollis’s guilt, basing his judgment on Gouzenko’s objection to the lies in the report ‘that had been made by the British intelligence officer who had interviewed and debriefed him in 1945 after he defected.’ Worthington especially drew attention to the claims made about the penetration of the Soviet system by British agents, and he reminded his Spectator readers that ‘the British security officer who came to Canada to interview Gouzenko in 1945 was Roger Hollis’. Worthington also boasted that Gouzenko had written, in 1952, ‘a special memorandum directed to British Intelligence’, which Worthington published in the Toronto Telegram 18 years later, and subsequently gave to Chapman Pincher in connection with his book Too Secret Too Long’, and which appears therein as Appendix A.

Yet, in their rush to jump on the band-wagon, all these writers seriously missed several vital points. Moreover, rather surprisingly, recent analysts, with a clearer canvas of archival material available, have failed to tidy up the mess. For example, two important articles that have been published in the intelligence press over the past few years have missed the opportunity to set matters straight. William Tyrer hinted at the confusion, but failed to come to grips with the problem in his rather convoluted coverage in ‘The Unresolved Mystery of ELLI’ (International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 29, 1-24, 2016). David Levy, in his article ‘The Roger Hollis Case Revisited’ (International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 32, 146-158, 2019) skated towards the paradox, but then avoided exploring it. Both writers were equivocal about Hollis’s contribution in September 1945.

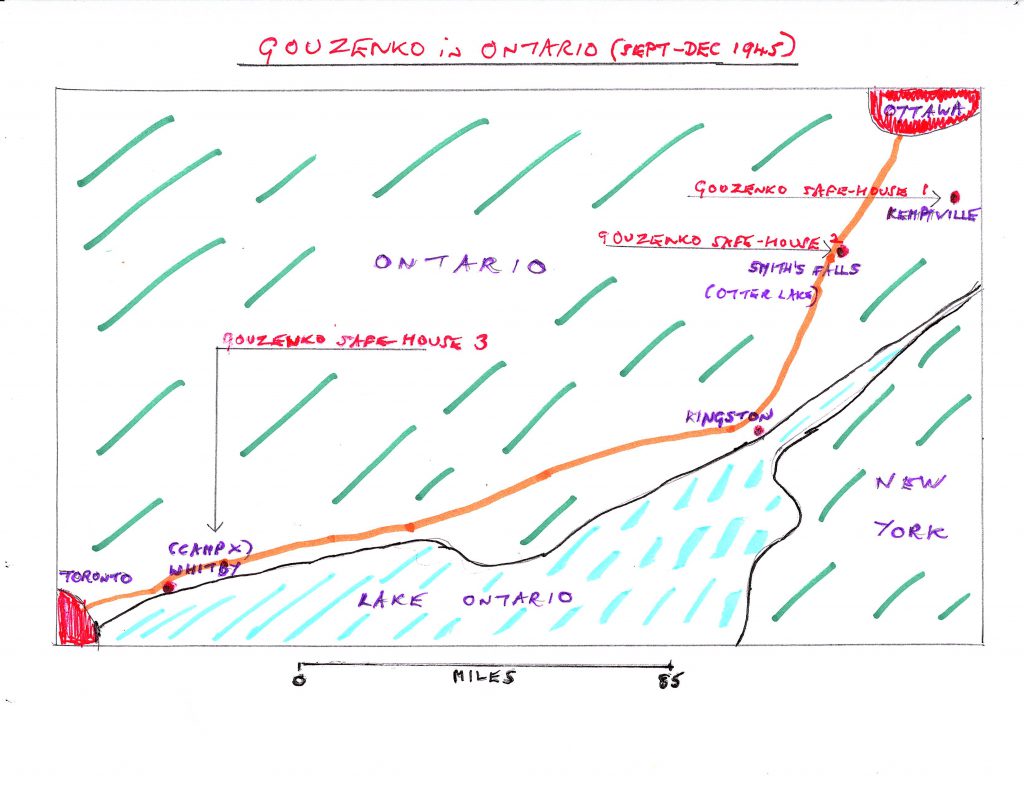

The first point is that Roger Hollis did not interrogate Gouzenko in September 1945. The archive is quite clear that his September mission was to deal with the courses of action deriving from the exposure of Nunn May. Gouzenko had been secluded, for security reasons. He and his wife were moved at the beginning of October to a safe-house in Kemptville, and, after a couple of nights, to one at Otter Lake (about 100 miles from Ottawa), and, two weeks later, to Camp X, which was situated near Whitby, on the northern shore of Lake Ontario, about two hundred and fifty miles from Ottawa. No casual meeting would have been allowed, and even the MI6 members of the now resident BSC team (Dwyer and Evans) were not given an audience. Dick White’s testimony about Hollis interrogating Gouzenko ‘on the shores of Lake Ontario’ represents a dangerously naive attempt to add verisimilitude. Hollis’s first interview with Gouzenko was on November 21, and the report I cited in my March article (the one discovered by William Tyrer, dated November 23, 1945) constitutes the record of that interview, when Gouzenko was brought from Camp X to Ottawa. (The fact that that meeting took place is confirmed by a telegram from London to New York of May 23, 1946, visible at KV 2/1423-2, sn. 216A.) On the other hand, the information about an Allied agent in the Soviet Union (including the reference to Polakova/Poliakova) was provided on September 15, the day before Hollis left for Canada the first time.

(By the time he wrote Cold War Spymaster (2018), Nigel West had modified his stance. He corrected the chronology, although he wistfully reflected on his previous assertion in the following terms: ‘While there is no evidence that Hollis actually met Gouzenko in September 1945 . . .’.)

Thus the second fact ignored by the commentators is that Hollis did not introduce the notion of a British spy in Moscow. The name ‘ELLI’ was known by September 15, and the transcripts of the telegrams received by Liddell in September show very clearly that this idea was transmitted by Dwyer, based on the RCMP interviews with Gouzenko. The insight stimulated both Dwyer and Liddell to focus, separately, on possible SOE links. The October 29 evidence from Gouzenko confirmed the earlier ‘agent in Moscow’ story that he had supplied in September, but also severely muddied the waters before Hollis ever had a chance to meet him. Gouzenko was here relying on further hearsay evidence from another clerk, and thus possibly merging the details of two individuals, as well as casting doubts on the strength of the ELLI identification process. This recognition is confirmed by Liddell’s diary entry of November 5, well before Hollis’s interview with Gouzenko. The passage cited above by Knight corresponds to the RMCP interrogations that must have occurred in September and October. All that Hollis’s report states about the agent in Moscow is to confirm the previously offered insight that the attaché in Moscow would not reveal the name of his agent.

A third distortion occurs in the authorship of the so-called ‘BSC report’. As this was compiled before Hollis arrived on the scene (as is now obvious), it was clearly written by Peter Dwyer and John-Paul Evans, the MI6 representatives attached to BSC, who flew to Ottawa as soon as the Gouzenko case broke. (Knight records this authorship.) Yet neither Dwyer nor Evans interviewed Gouzenko in person. The BSC report was based on information provided by RCMP officers. Moreover, by some vague process of ahistorical drift, it is represented by Pincher and Worthington as being written by Hollis, but Hollis did not compile any report on Gouzenko (as opposed to one on Nunn May) until he had seen the defector, in late November. What he did accomplish, as noted above, was to bring a copy of the Dwyer/Evans report with him when he returned to the UK at the end of September. All of Knight’s analysis is based on the premise that the November 1945 interview that Hollis had with Gouzenko was his second exposure, and she thus presents earlier events (such as the RCMP interview on October 29) as elaborations on what she claims Hollis had discovered in September. Yet all information at that time came from the RCMP via Dwyer and Evans.

The fourth important matter overlooked by these writers is that Gouzenko was correct for the wrong reasons. He suspected forgery, but was let down by his faulty memory, and the wiles of MI5.It is somewhat astonishing that he could not distinguish, even twenty-seven years later, between the circumstances of his several interrogations at the safe house and at Camp X in September and October by RCMP officers (when John Leopold was the interpreter/translator), and his short interview with Hollis in November, which took place in Ottawa (by which time Mervyn Black had assumed the role). Gouzenko claimed to have been interviewed by an MI5 officer (presumably Dwyer, but certainly not Hollis!) in September, when, by all other accounts, not even Dwyer (of MI6) had direct access to him. Gouzenko failed to recall what he had told his RCMP interrogators, including the important intelligence about the British agent in Moscow, and mixed up those interviews with his encounter with Hollis. He rightly was suspicious of the document that Stewart showed him, but was in a muddle about what constituted British counter-intelligence (it could be MI5 or MI6), and allowed himself to be convinced that Hollis had concocted the whole mishmash. [Problems remain with Gouzenko’s testimony, which I shall analyze in a future report. And the possibility must not be discounted that the transcription of his earliest statements was in error, since he never signed off on it.]

In such a way do untruths accumulate. Amy Knight’s lack of chronological discipline causes her whole analytical scaffolding to collapse. Instead, the evidence all suggests a very clumsy attempt by MI5 to frame Roger Hollis, one that was abetted by Gouzenko’s erratic memory, and his strong suspicions of possible traitors around him.

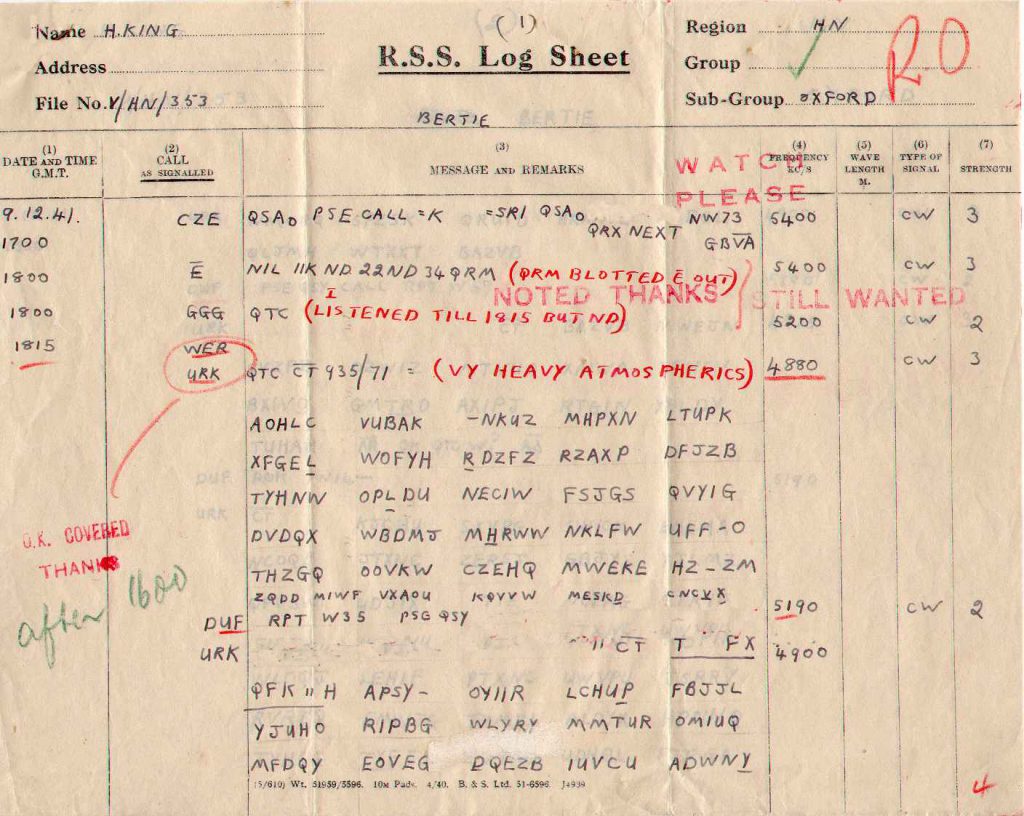

b) Peter Wright and VENONA Telegrams:

Strangely, Peter Wright, in Spycatcher, made no mention of the Patrick Stewart visit to Canada in 1972. In contrast (p 282), he described his own efforts to interview Gouzenko in the mid-1960s, but was told that by then ‘he was an irretrievable alcoholic.’ “I sent a request to the Canadian RCMP for permission to interview Gouzenko once more, but we were told that Gouzenko had been causing problems for the Canadian authorities through his alcoholism and badgering for money. They feared that further contact with him would exacerbate the problems, and that there was a high risk Gouzenko might seek to publicize the purpose of our interview with him.” It is not clear why the RCMP changed their minds a few years later. Chapman Pincher took pains (Treachery, p 248) to relate that whenever he spoke to Gouzenko, and at the time Stewart interviewed him, the defector was coherent and rational in all respects, and that ‘the previous conviction in MI5 that he was a hopeless drunk was an internal deception’. Pincher does not explain why the RCMP originated this slur: nor does he say why or when it became a ‘conviction’ in MI5 rather than perhaps an excuse by the RCMP for limiting visits.

On the other hand, Wright did throw fresh confusion in the works through his citation of VENONA telegrams as a factor in reinforcing the treachery of ELLI, and the claim that Hollis was the probable candidate. First, he recorded that the RCMP told him that the original notes of the debriefing had been destroyed (thus implicitly questioning the authenticity of what Stewart later presented). Yet, as Wright puzzled over the evidence in intelligence files, and pondered over the reasons why Hollis had been sent out to Canada, he focused on Hollis’s apparent attempt to have Liddell’s diaries destroyed, since those journals had speculated on the identity of ELLI. [No matter that the Diaries never betray any suspicion that Hollis was ELLI: in fact they would help the cause for Hollis’s innocence.]

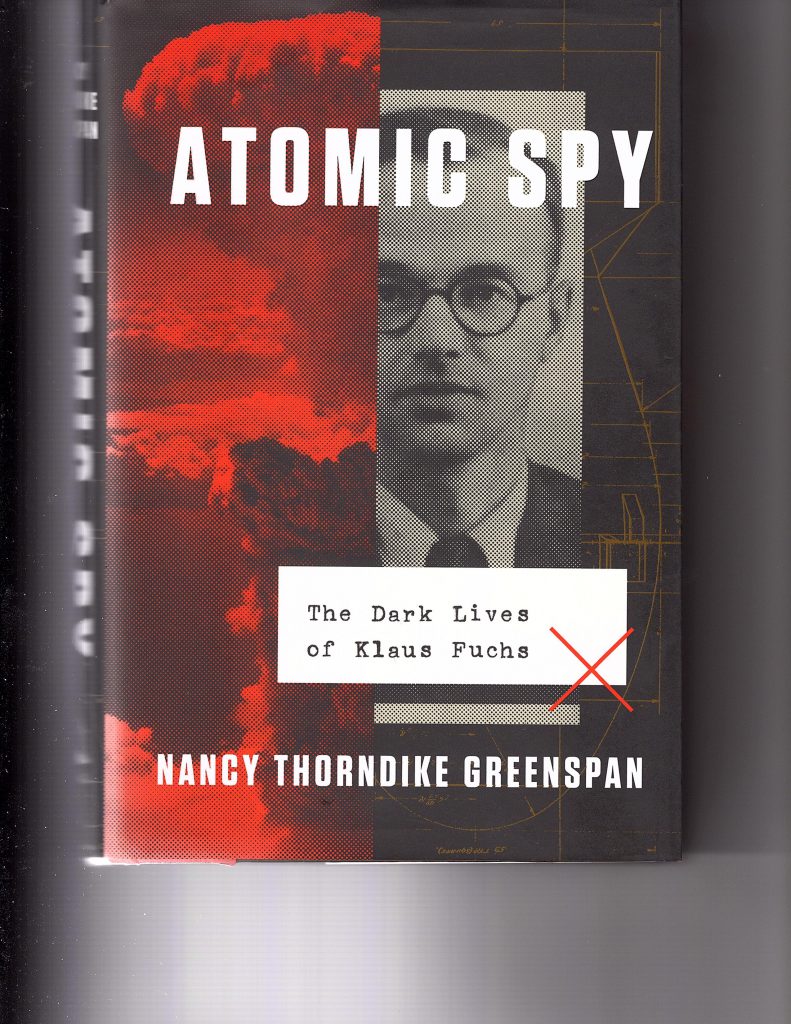

Then Wright recorded a somewhat miraculous breakthrough in breaking out VENONA traffic. He introduced his story by referring to the famous VENONA message that constitutes the confirmation from the KGB about the GRU, but he misrepresented its essence. Wright strongly implied that Hollis was sent to Canada in September to interview Gouzenko, and based his text on that assertion. “We have it from VENONA, however, that the KGB was unaware of the existence of a GRU spy in MI5 when Hollis travelled to Canada and interviewed Gouzenko,” he wrote. As I showed in the previous article, this is a great distortion, one that was reinforced by Pincher. That telegram states no such thing: it was dated September 17, before Hollis arrived in Ottawa, and merely confirmed Philby’s information about GRU spies in Canada. Moreover, Philby’s report of November 18 (which is reproduced in full on pages 238 and 239 of Nigel West’s and Oleg Tsarev’s Crown Jewels, and appears in Vassiliev White Notebook p 27) deals exclusively with the Nunn May case, and its political fall-out, and makes no mention of ELLI or other spies within the intelligence services.

The breakthrough (according to Wright) came with the analysis of a week’s traffic from September 15. It began that day, ‘with a message to Krotov discussing, with no sense of panic, the precautions he should take to protect valuable argentura [sic: agentura] in the light of problems faced by the ‘neighbours’ in Canada’. Wright interpreted this to mean that the KGB had no reason to fear that any of its agents in Britain had been compromised by Gouzenko. Yet, by the end of the week, on September 22, ‘the tone of the messages is markedly different’. “The relaxed tone disappears, Krotov is given elaborate and detailed instructions on how to proceed with his agents. ‘Brush contact only’ is to be employed, and meetings are to reduced to the absolute minimum, if possible only once a month.”

Wright then asked GCHQ to conduct a search on the London to Moscow traffic – but it could not be read. The only significant message they could identify was a Moscow to London message sent on September 19-20 ‘which they could tell was a message of the highest priority because it overrode all others on the same channel’, and Wright concluded that its significance was obvious, as it had been sent the day after Philby had received the MI6 telegram containing Gouzenko’s description of ELLI in ‘five of MI5’. “Indeed,” he wrote, “when GCHQ conducted a group-count analysis of the message, they were able to conclude that it corresponded to the same length as a verbatim copy of the MI6 telegram from Canada which Philby removed from the files.”

Wright and Geoffrey Sudbury (his colleague at GCHQ then sat down made a determined attack on a high-priority message sent by Moscow in reply. It was sent at the end of the week (i.e. about September 22), and eventually they were able to break it out. According to Wright, it read: “Consent has been obtained from the Chiefs to consult with the neighbours about Stanley’s material about their affairs in Canada. Stanley’s data is correct.”

In many respects, this account looks like a farrago of nonsense. First of all, the Vassiliev Notebooks (Black, page 54) inform us that, in light of the increased local surveillance measures, a generic message for all stations (VADIM, SERGEY, BOB and IGOR) about the need for extra caution was despatched as early as September 10. It is worth citing the bulk of the message:

It is essential to carefully prepare for every meeting with agents; operatives should meet with agents no more than 2-3 times a week. Arrange work with agents in such a way that the work of the operating staff is indistinguishable from the work of other members of the Soviet colony. Select authoritative and confidential group handlers from among the local citizens and operate the agents through them. High level workers should meet with group handlers as rarely as possible and only for briefing and to go over assignments.

This message was not decrypted under VENONA.

Thus it would have been not only logistically impossible but also in contradiction of instructions for Philby to have received the message about ELLI, arrange a meeting with Krotov, have his handler send a message to Moscow, and the KGB then investigate the matter with their superiors and the GRU, and then send a message in return the next day. Moreover, we have it on record that the famed ‘confirmation’ message to Krotov (BOB) was sent on September 17, i.e. before Philby received the news about ELLI. Certainly, further warning messages were sent. A message dated September 21 (‘surveillance has been increased’: Vassiliev, Black, p 57) was directed at the USA (VADIM, in Washington) only, and identified agents operating in the USA. A similar message from Moscow to London on the same day (VENONA 34) includes the same precautionary language, and corresponds to the message identified by Wright above, but its main emphasis is on HICKS (Burgess). A further message that day (VENONA 64A) contains a specific warning about maintaining secrecy in meetings with STANLEY (Philby). Furthermore, according to the evidence, the phrase ‘five of MI5’ never appeared in any of the September reports: the indication of some association with ‘5’ in intelligence came in Hollis’s report at the end of November.

The conclusion must be that the precautionary messages had nothing to do with ‘ELLI’. In fact, Philby had requested an urgent meeting with Krotov on September 20 (using Burgess as a courier) in light of the Volkov news from Istanbul. Of course, Peter Wright was writing in 1987, long before Vassiliev got to work, and did not know then that the VENONA transcripts would eventually be published. He therefore thought he could get away with falsifying the record. He presented the confirmatory message about Philby as arriving several days later than it actually did, as if it had been provoked by an alert from Philby about ‘ELLI’ that in fact was never articulated.

c) Guy Liddell and the RCMP:

One of the dubious stories that has gained traction is Gouzenko’s claim that, when Guy Liddell visited Ottawa in 1944, this information was leaked by someone based in London. For instance, the claim can be found in the Spartacus profile of Gouzenko at https://spartacus-educational.com/SSgouzenko.htm. The source given is Philip Knightley’s Master Spy (1988), page 130. Yet no trace of that assertion can be found on page 130 of the book – nor on any succeeding page. Nevertheless, Chapman Pincher echoed this story (Treachery, p 24), where he (correctly) pointed out that Liddell did pay a visit in 1944 to advise the RCMP on German counter-espionage. Pincher quoted Gouzenko as suggesting that this leak meant that ‘Moscow had an inside track in MI5’.

Pincher’s opinions evolved through the creation of Their Trade is Treachery, Too Secret Too Long, and Treachery, as was only natural, given the paucity of archival sources in the early days, and the proliferation of rumours. Regrettably, instead of admitting that he did not know certain things, or that the information was ambivalent, Pincher would use every snippet to try to bolster his accusations against Hollis. (I shall investigate in depth, in a later article, Pincher’s interactions with Gouzenko.) The story about Liddell is just such an example. Gouzenko’s claim can be seen in the Report he submitted to Sergeant McLellan of the RCMP, after a request from MI5, on May 6, 1952. (As I indicated earlier, the whole report appears as Appendix A in Too Secret Too Long.)

Here Gouzenko described some ‘indirect, but possible evidence’. “In 1944, (the latter part, or maybe the beginning of 1945), in the embassy, Zabotin received from Moscow a long telegram of a warning character. In it, Moscow informed that representatives of British ‘greens’ (counter-intelligence) were due to arrive in Ottawa with the purpose of working with local ‘greens’ (R.C.M.P.) to strengthen work against Soviet agents, and that such work would definitely be stepped up.” After outlining the precautionary actions that were taken, Gouzenko commented: “Now it could be that Moscow just invented these representatives who were supposed to arrive in Ottawa, in order to make Zabotin more careful. On the other hand, it might be genuine, in which case it would mean that Moscow had an inside track in the British MI5.”

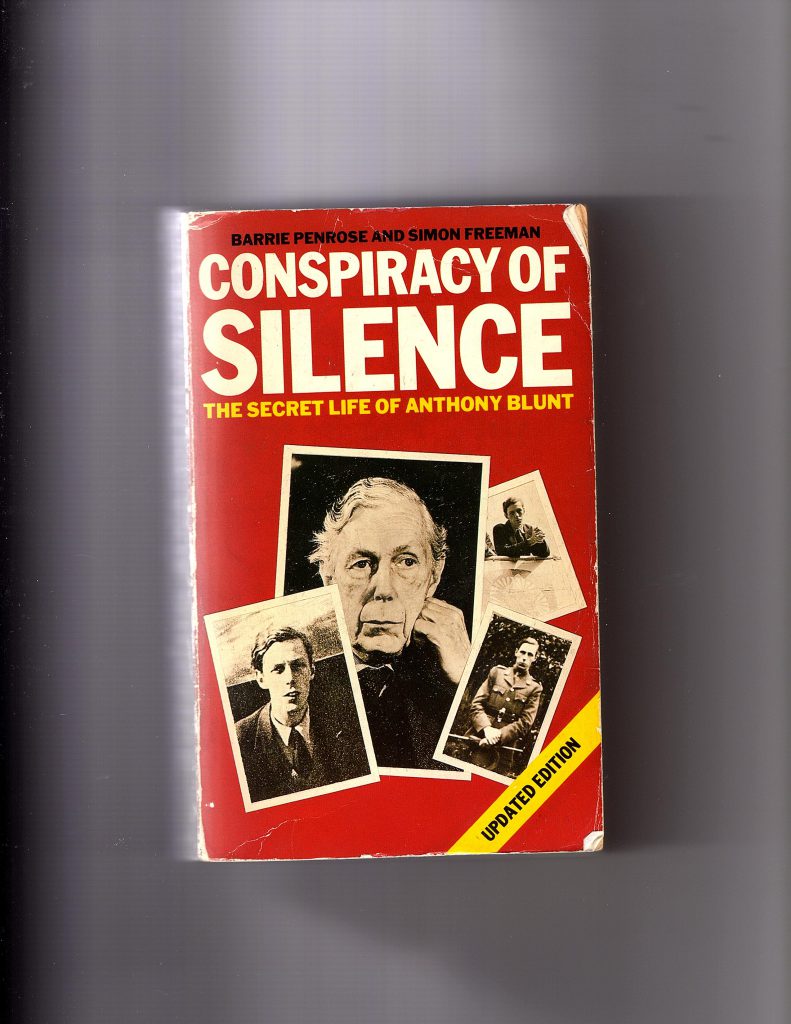

That is hardly the unqualified assertion as expressed by Pincher. Yes, Guy Liddell did pay a visit to Ottawa, in July-August 1944 (not at the end of the year). He was there to discuss with Cyril Mills a possible double-cross operation against the Germans, and advise the RCMP, which was in fact a police force, not a counter-espionage organisation. There is no evidence that MI5 recognised at that time a problem of Soviet agents in Canada, and Liddell travelled alone. Of course, Anthony Blunt (NKVD, not GRU) might have been the source of the information about Liddell’s visit. For example, on July 7, 1944, he provided Moscow with a full report on the Double-Cross system, and would have been very aware of Liddell’s movements.

d) Roger Hollis and Counter-Espionage:

Much has been made of the fact that Roger Hollis was MI5’s expert in Soviet counter-intelligence. Nominally, this might have been so, but, in truth, he was far from being able to fulfil that role. In September 1945, he was head of F Division, ‘Counter-Subversion’. F Division had been split off from B Division in April 1941 by the new Director-General Petrie, as part of his ‘new broom’ reorganization, so that Liddell’s team could focus on the Nazi threat. John Curry had been its first chief, but had moved across to a staff position under Petrie in October of that year, allowing Hollis to take his place. In May 1943, Curry moved over to MI6 to help set up the service’s Soviet counter-espionage section (Section IX).

The mission of F Division was very much on constraining and defanging domestic ‘subversive activities’. When Hollis was placed in charge of F2 (‘Communism and Left Wing Movements’), he had Clarke watching over Policy Activities of the CPGB (F2A), a vacancy for the position managing ‘Comintern Activities generally, and Communist Refugees’ (F2B), and Pilkington representing ‘Russian Intelligence’ (F2C). By April 1943, when Hollis had taken over the Division, Hugh Shillito had replaced Pilkington, and was responsible for F2B and F2C. Thus F Division was very thin on experience with the Soviet espionage threat. In his in-house history, John Curry lamented the fact that the only officers who knew anything about Soviet espionage (Liddell, Harker and Archer) had all been diverted to activities directed against the war enemy.

A major part of the problem was that the movements of communist subversives did not respect the artificial boundaries that divided the responsibilities of MI5 and MI6 into the territories of the Empire, and foreign countries, and thus MI5 was totally reliant on the co-operation of MI6 when it came to providing information about the backgrounds of dubious characters trying to enter the UK, or any imperial territory. The protective policies of Felix Cowgill caused serious rifts during World War II, especially over ISOS (Abwehr ENIGMA) decrypts that revealed German analysis of the results from double-agents, and MI5 also clashed with SOE over escaped agents being too hurriedly allowed into the country without proper vetting. The officers in charge had no direct exposure to the decade of the ‘Great Illegals’ in the 1930s, and the lessons that Walter Krivitsky had provided were too easily overlooked.

Hugh Shillito seems to have made a game attempt to overcome the inattention, and he doggedly pursued the cases of Oliver Green and Sonia, while receiving discouragement from senior officers. In these endeavours, he was determinedly backed up by Milicent Bagot, who assuredly knew the history, but they were both greatly rebuffed in their inquiries. As Curry wrote: “The only palliative to this situation [the inferiority of MI6 records] was that F.2.b was in the hands of Miss Bagot, whose expert knowledge of the whole subject enabled her to find and make available a large variety of detailed information based on the records of the past.” By the autumn of 1945, Shillito (whom Hollis had more than once, probably unjustifiably, characterised as ‘idle’ and ‘ineffective’ in complaints to Liddell, but of whom Curry thought highly), had left the service. Bagot was also fed up, and wanted a transfer.

What is more, MI5 at that time lagged severely behind MI6 in developing structures to handle the Soviet threat. MI6’s Section IX had been set up in May 1943 by Curry, and Kim Philby had engineered his takeover of it by November 1944, when Curry retired from the job. The result was that MI5 dithered. Liddell knew implicitly that the problem had to be addressed by MI5, as his diaries constantly show through the winter of 1945-46. Yet, even though he was the expert on what the Soviets were up to, it was not in his power exclusively to solve the problem. F Division, Petrie’s creation, did not report to him. Hollis, who had at least shown some imagination over the Soviet threat, and written several monitory reports in his vantage point in F Division, obviously did not want his stature diminished by reporting through Liddell.

Hollis was known as somewhat of a plodder, one who preferred the quiet life. He was not temperamentally suited for the role of counter-espionage chief. He did not have a first-rate brain, showed little intellectual curiosity, and would have been bemused by the layers of deception inherent in spycraft. He knew no Russian, and had not been exposed to the structures and techniques of the NKVD and the GRU. He was not a practised or natural interrogator. As K. D. Ewing, Joan Mahoney, and Andrew Moretta wrote, with some equivocation, in their 2020 book MI5, the Cold War and the Rule of Law: “That in 1945 Liddell chose to describe Hollis as an ‘expert’ on counter-espionage was arguably an accolade which reflects [more] the dearth of knowledge about Soviet intelligence operations against the west than upon Hollis’ qualities as a Security Service officer” (note 25, p 454).

Thus it is not surprising that Liddell himself eventually sought an audience with Gouzenko. Amy Knight completely mis-represented Hollis’s role when she described him as MI5’s ‘point-man’ on Gouzenko, and it appears that Kim Philby himself wrote a tissue of lies in his report to the KGB (Should Agents Confess?) when he described setting up meetings with Hollis and lawyers immediately the news about Nunn May came though. Hollis was on holiday at the time. (Unless, of course, Liddell was lying, and Philby’s account is more reliable . . .)

3. Background Clarification:

a) Stephen Alley:

Readers will recall, from my March posting, how Guy Liddell’s analysis of hints provided by Gouzenko through Peter Dwyer led him to discern an SOE connection in the person of ELLI. The fact that, under Operation PICKAXE, the Special Operations Executive had developed a liaison with the NKVD in Moscow and in London suggested to him that an indication of leakages hinted at by Gouzenko might involve security lapses at both ends. There is strong evidence that Stephen Alley, because of his fluent Russian, and his role within MI5, was the officer who shepherded Colonel Chichaev, the NKVD military attaché who represented Moscow in London. Liddell considered Alley as a possible candidate for ELLI before quickly rejecting the idea as absurd.

A close inspection of the conclusions of Dwyer and Liddell is provocative. As I described in March, Dwyer came up with Ormond Uren’s name as a candidate for ELLI. But Liddell instantly dismissed that hypothesis. On November 1, 1943, however, he had recorded in his diary that Uren had ‘divulged the complete lay-out of SOE’s organisation’. Thus something in the information provided by Gouzenko must have indicated to him either a) that there were corners of SOE’s organisation that were not known to Uren, or b) that the disclosures had occurred either before his recruitment to SOE (in 1942) or after his arrest (in July 1943), or c) that the additional hints about ‘Russian descent’ excluded Uren. The third alternative seems the most likely, and may have pointed him towards Alley. In addition, Uren was known to have worked by supplying secrets to Dave Springhall, not to a Soviet handler from the Embassy.

In my previous posting, I drew attention to the astonishing way in which Alley has been excised from the historical record. He makes three brief appearance in the published extracts from Liddell’s Diaries (Volume 1, pages 66, 158 and 245), but Nigel West does not judge him important enough to be listed in his introductory ‘Personalities’. Alley does not appear in the Index of Christopher Andrew’s Defend the Realm, nor does John Curry list him there in his in-house history of the Security Service. Similarly, Nigel West overlooks him in his account of MI5. Curry does show Alley in his organisation charts, however: for June 1941, as Major Alley, sharing responsibility with Mr. Caulfield for E2, a section of Alien Control that managed Nationals of Baltic, Balkan and Central European countries, and, in 1943, maintaining a similar role in that Division.

Yet Alley had a remarkable background. He was born in Russia, and thus had a stronger claim to have been ‘of Russian descent’ than any other candidate for ELLI. As Keith Jeffery recounts, Lieutenant Alley accompanied Captain Archibald Cumming as a member of the mission sent to Petrograd on September 26, 1914. By February 1917, Alley had been promoted to captain in MI1(c), and was responsible for controlling passengers travelling from Russia to England or France, for counter-espionage and the coordination of intelligence matters with the Russian Secret Service. Claims have been made, dependent on the verification for authenticity of a letter that Alley wrote to his colleague John Scale, that he was involved in the murder of Rasputin. Others suggest that he was party to the unsuccessful attempts to save the Romanov family from their execution. In his Historical Dictionary of British Intelligence, however, Nigel West brings Alley’s colourful career down with a thud. After being evacuated in 1918, Alley ‘served in MI5 for three years and then moved to Paris, where he ran a business trading in commodities’.

[In my previous piece, I referred to Alley’s memoir, held by Glasgow University, which rather shockingly tells how Alley was dismissed from MI6 for declining to assassinate Stalin. I have succeeded in contacting the Librarian at the University, but, because of the Covid lockdown, the staff were not allowed into the archive to inspect the status of the memoir for me. A verification of this astounding item will therefore have to wait a while.]

An analysis of MI5 files at Kew, and especially Guy Liddell’s Diaries, shows that Alley was involved in several significant activities with MI5 during World War II. He was the officer who welcomed Walter Krivitsky ashore in January 1940, impressing the defector with his excellent Russian, and thereafter acted as translator for Jane Archer (Sissmore) during the interrogations. Liddell records him having a last confidential discussion with Krivitsky before he returned to the Americas. When the Poles planned to assassinate Rudolf Hess in June 1941, in the belief that such an action would avert peace talks, Alley was brought in to investigate, and produced a report for Liddell – all of which is reported in Nigel West’s Encyclopedia of Political Assassinations.

When Liddell first identified Colonel Chichaev, the NKVD officer liaising with SOE in Operation PICKAXE, in his diary entry for July 19, 1943, the name of the officer who was introduced to Chichaev by the Czech, Bartik, was later redacted, but it is highly probable that it was Alley. Chichaev’s background in Finland and Reval was mentioned, and it would need MI5’s premier (and maybe only) Russian speaker in MI5 to engage with him. It is apparent that the officer had had a lengthy interview with Chichaev in order to assess his character. Alley’s name fits in the redacted space, and Liddell wrote of this officer: “He thinks that provided the odds are not too much against him, he can handle CHICHAEV without making the slightest concession to the amour propre of the man himself or the country he represents.” The fact that Alley had a prominent role in handling Chichaev is confirmed by numerous items concerning Chichaev’s engagements that appears in his file at the National Archives. They have the rubric “No action to be taken on this report without reference to Major Alley” boldly displayed on them.

Alley is also mentioned several times in the period in which the Gouzenko affair unfolded. He had apparently been drawn in to try to help the Dutch set up a counter-intelligence department, and Alley negotiates with Liddell and Colonel Eindhoven over providing training, in order to pre-empt the American OSS from taking over. It can thus be safely concluded that Alley’s name was considered persona grata for most of the war. For some reason, a direct association with Chichaev was later considered a little too sensitive, drawing attention unwittingly to what must have been an embarrassment.

Finally, Alley was friendly with George Hill, which brings him more closely into the net of the ELLI business. Exactly what Alley’s political sympathies were at this time is impossible to gauge (yet), but the role of this vital, knowledgeable, and influential personality in the Gouzenko affair has clearly been overlooked in the accounts to date. Last month, I emailed Nigel West to ask him why he thought that Alley had been ignored in all the histories (including his own). He replied that his impression was that Alley was not well-liked, and was regarded with some suspicion, by other MI5 officers. Yet West did not answer my question directly. I would have thought that the perceived lack of trust in Alley on the part of his fellow-officers should provoke greater interest in his career and influence, not less.

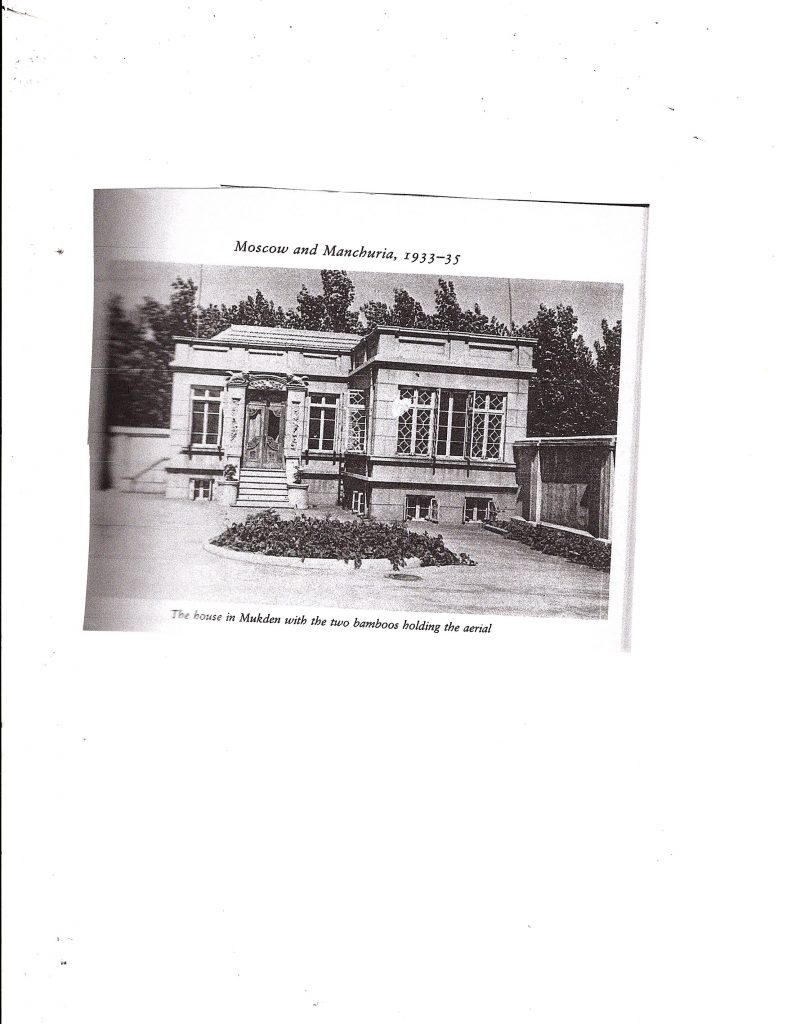

b) George Hill:

Far more has been written about Stephen Alley’s long-time fellow-agent and friend, and counterpart in the SOE Russian operation, George Hill. He wrote two published memoirs, Go Spy the Land (1932), and Dreaded Hour (1936), and an unpublished record of his WWII experiences, Reminscences of Four Years with N.K.V.D. (ca. 1967), is freely available from the Hoover Institution. As with any memoir, but especially those concerning intelligence matters, the material needs to be treated with caution. Furthermore, Peter Day has written a biography of Hill, Trotsky’s Favourite Spy (2017), which relies heavily on his subject’s memoirs, but also incorporates much archival and other material. Day informs us that, when Alley returned to Britain in 1919, he had ‘set up an unofficial lunch club for intelligence officers known as Bolo, short for the Bolshevik Liquidation Club, and George Hill had been a member alongside such as Sidney Reilly and Paul Dukes’. In Dreaded Hour, Hill describes how, in 1923, he bumped into his ‘old friend’, ‘Major Stephen Ally [sic], M.C. one time Assistant Military Attaché in Petrograd’ in London, whereupon the latter engaged him to help liquidate the Bulgarian branch of a huge British tobacco concern. Thus their anti-Bolshevik credentials had at that time been strong.

Hill’s appointment as SOE’s representative in Moscow was thus a controversial one, initially because the Foreign Office thought that his track-record in Russia would make him unacceptable to the NKVD, and on those grounds he had sceptics within SOE, too. After consulting Stafford Cripps, the ambassador in Moscow, Dalton was able to push though his nomination, and some have even stated that MI6 helped in the appointment – perhaps to weaken the unit. In January 1943, Menzies, who was a fierce critic of SOE, vented to Bruce Lockhart of the Political Warfare Executive about ‘the nomination of a hopeless adventurer like ‘Flying Corps’ Hill as their man in Moscow’, perhaps unaware that his underlings may have abetted the appointment.

More serious reservations emerged after Hill was installed, moreover. MI5 and others judged that he had become too easily manipulated by his Soviet counterparts, and feared that his character defects would lead him to be naturally exploited. He had been introduced to SOE through Lawrence Grand and D Section of MI6, and had actually shared training duties at Brickendonbury Hall and at Beaulieu with Kim Philby, who recalled Hill in his own memoir. The conflicts and disputes that endured over Hill’s time in Moscow are too complex to be covered in detail here, but can be summed up as consisting of the following: a) security exposures in the Moscow station; b) Hill’s indiscretions in getting too close to Ossipov, his NKVD counterpart, and giving him confidential information; c) Hill’s dalliance with the hotel manager, Luba Polik, who was surely under the control of the NKVD; and d) Hill’s evolving sympathies with his hosts’ politics, which drew him into a massive clash with the head of the Russian section of SOE, Len Manderstam, over the propaganda role of Soviet citizens forced to serve in the Wehrmacht.

For the purposes of the ELLI investigation, the claims about Hill running an agent in Moscow are of the most relevant. Recall the vital phrase from the BSC report: “The British had a very important agent of their own in the Soviet Union, who was apparently being run by someone in Moscow.” In his Reminiscences, George Hill describes how, in March 1942 he was accosted in his hotel by a man, Sergei Nekrassov, whom he did not recognize at first. When the man identified himself as Hill’s ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’, Hill realized who he was: ‘my best White Russian agent, 1919-1922. A Tsarist cavalry officer from a crack regiment, fearless, resourceful, who loathed the Reds, and went through their lines like a needle through a haystack.’

When Hill went to drink brandy in Nekrassov’s room, he quickly conjectured that Nekrassov had been sent as a provocation, and, overcoming the temptation to re-use Nekrassov as a source, he complained by telephone to Ossipov, who claimed to know nothing about Nekrassov. But before Ossipov arrived (at 5:30 in the morning), Hill wrote out a report on the incident, with one copy for Ossipov, and a second to the Foreign Office via the Embassy diplomatic bag. Thus, when Hill returned to the United Kingdom in the autumn of 1943, Liddell and White presumably had some knowledge of the incident. Part of Liddell’s diary entry for October 5, a long account of the discussion he had with Hill, alongside Dick White and John Senter (the MI5 liaison in SOE), accompanied by two other unnamed SOE members, runs as follows:

The Russians had sent him a man who had worked for him in 1920, and who had made suggestions about working for him again. Hill did not fall for this but immediately rang up the NKVD. The man was removed from the National Hotel where Hill stays with apologies. Three of four months later however he made another approach. Hill then became exceedingly annoyed. The man disappeared again and Hill was told that he had been severely dealt with. The whole thing was an obvious plant. It was however an interesting example of Russian distrust. Hill had never made any attempt to disguise his past activities in Russia which were of course well known to them owing to the publication of his book. He thinks he was accepted because he was regarded as a professional. The Russians have a liking for professionals and experts.

This passage is, I believe, significant in several aspects. First, it confirms what Hill wrote in his memoir, namely that he objected violently to the approach, and made his reaction known to Ossipov. (Whether that account is entirely true cannot be assessed, of course.) Second, Liddell was clearly familiar with the story of Hill’s encounter with an ‘agent’ in Moscow – although that figure was supposed to have been retired long before then – and appeared to accept Hill’s account at face value. Yet, in November 1945, Liddell was unable to associate this anecdote with the disclosure emanating from Gouzenko [see my March report]. Perhaps most startling, however, is the method by which the story could have been leaked – and possibly misinterpreted. Hill had sent a copy of his letter to the Foreign Office, and here, apparently, were two junior officers in SOE who were being regaled with the same information. Had Hill told them this story beforehand? It is not clear. Since Liddell also reported on the fact that Hill said that Chichaev ‘had received instructions from Moscow not to hold official conversations with U.35’ [‘Klop’ Ustinov, an MI5 agent: coldspur], it would seem a gross misjudgment by Liddell and White, on security grounds, to have Hill talking so freely on these matters.

In any case, it is perhaps easy to imagine how the story about Hill’s ‘agent in Moscow’ made the rounds, and became distorted in the process. If Alley was informed, he may have shared it with Chichaev, not even thinking that it was a confidential matter. Chichaev may not have understood the subtleties of the incident, but would have been bound to report such matters to his bosses in Moscow, with the inevitable result of alarm-bells ringing. Poliakova would have taken the news to the Kremlin, whereupon Ossipov would have smoothed matters over.

A question mark must remain over Hill’s honesty, as well as his judgment, however. Chapter XIV of his Reminiscences, purportedly written in 1945, starts off as follows:

“Uncle Joe”, had skilfully gained his aim. The Polish Provisional Government in London was powerless to prevent the Lublin Committee becoming the Lublin Provisional Government, and not much later the Government of Poland. Prime Minister Mikolajczyk due to pig headedness and failure to face realities and utter miscalculation of Mr. Churchill’s strength and the intention of dying President Roosevelt. Thus Poland as planned by Stalin became communist; a satellite of Moscow. General Mihailovic was out, Yugoslavia was to be governed by Marshall Tito, a satellite of Moscow. Bulgaria was communist, Comrade Vyshinsky saw to that. Czechoslovakia was still Democratic, but not for long. Truly those ‘Planners’ in London, drawn from the Foreign Office and State Department had made a mess of their task.

Yet in a report to his SOE bosses in January 1944, Hill had written the following:

All this means what I have endeavoured to point out in previous despatches that the moral leadership of the new Europe has passed to the Soviet Union in much the same manner as England had the moral leadership in the nineteenth century when Liberal movements were astir in Europe. The day has passed when this new movement should be considered in terms of ideologies. It is no longer a matter of communism versus capitalism or even socialism versus capitalism. It is rather a struggle of the peoples of Europe to free themselves of some of the vested interests of the past. These vested interests have been throttling the efforts of the people to attain that degree of political and economic security they feel will put an end to the miseries which have vitiated the lives of a whole generation. The peoples have been looking forward to the leadership of one of the great powers and in this way they have been finding it in the Soviet Union. It is up to the real democracies of the West not to lag behind but to keep in step with the progressive movements now preparing the way to a brighter future for the oppressed people of Europe. (from HS 4/338 at The National Archives)

This echoed a pitch he had given Bruce Lockhart in March 1943. It is pure Marxist propaganda, straight from the editorials of Pravda. Hill was a humbug, and a dangerous one at that. He had gone native. The efforts of ELLI pale beside this rampant example of ‘useful idiocy’. Yet, a third leg of the stool – alongside Hill’s romantic dalliances, and his Stalinist sympathies – eclipsed any security threat that may have been posed by the obscure ELLI. And that concerned Hill’s aide-de-camp, George Graham.

c) George Graham:

Readers will recall, from my March posting, the meeting that Liddell had with Archie Boyle on November 16, 1945, where they discussed, among other concerns about the Moscow outfit, their suspicions about George Graham. When Hill travelled to Archangel, at the end of September 1941, on the minesweeper HMS Leda, the other two members of his team were on another ship of the convoy, and arrived at the same time after a difficult three-week voyage. The first member, Major Richard Truszkowski (‘Trusco’), had been foisted on Hill at the last moment, and Hill complained bitterly about him in his memoirs, as he was the son of a well-known Pole who had fought Russia ‘tooth and nail, in Tsarist days’. The Polish faction in SOE had demanded that they have a representative with the Polish forces in the USSR, and Frank Nelson and Hugh Dalton had given in. Hill thought his appointment would only arouse the NKVD’s suspicions. (Hill had himself been cleared, despite his similar background.)

About Graham, Hill said little, only that the Lieutenant was in the Intelligence Corps, and that Hill had selected him as his A.D.C. Nevertheless, he relied upon him extensively. One of the items that the Hill party took with them to Moscow was a heavy Chubb safe in which to lock the codes and ciphers each night, but when the embassy was evacuated to Kuibyshev, soon after their arrival, because of the proximity of Hitler’s army, the safe had to be left behind. When an apartment had been found for the SOE office in Kuibyshev, Hill wrote in his diary: “We take care never to leave the flat alone; poor Graham is practically chained to it. Our files and codes are kept under lock and key when not in use. Not in a safe, deary – we ain’t got one – but in our largest suitcase, which is nailed to the floor.” [Much of Hill’s memoir derives from letters that he sent his wife.]

Yet a few months later, Graham and Hill were separated. When it was safe, after a few months, to return to Moscow, Ossipov went first, followed by Hill in early February. But Hill had to leave ‘Trusco’ and Graham behind, much to Hill’s chagrin. “I don’t like being separated from Graham, though, especially on account of coding,” he wrote. Trusco was scheduled to return to England in mid-February, so Graham would have sole responsibility for the flat. Before Hill left (by train), he had to write out orders for Graham, ‘covering every likely eventuality’. “Codes and cash we deposited with the Embassy, otherwise poor Graham would have been tied to the flat for keeps: he will do his coding at the Embassy”, he continued.

Hill’s chronology is annoyingly vague (and not much helped by Peter Day in Trotsky’s Favourite Spy), but it seems that Hill did not see Graham again until he returned to Kuibyshev in about July 1942, to renew his passport, as he had been recalled to London for discussions. Even (or especially) in wartime, strict diplomatic protocols had to be obeyed. Thus Graham had been left for several months without any kind of formal supervision. As a member of the Intelligence Corps, his credentials were presumably considered impeccable.

At some stage, concerns about SOE’s security in the Soviet Union must have been raised. Initially, this focused on physical security: SOE’s premises had been previously used by the Yugoslavs, and Soviet technicians must have placed bugs in them before Hill took over. Even Kim Philby knew about this. “A very belated security check of his conference room in Moscow revealed a fearsome number of sources of leakage”, he wrote in My Silent War, suggesting he knew about it at the time, or soon after. Yet the security problem did not stop there. And that is why the infamous Liddell diary entry for November 16, 1945, becomes so relevant. Archie Boyle, who was head of Security for SOE during the war, describes to Liddell the close relationship between Hill and Graham: “Archie says he cannot understand how a man like Hill can possibly be acceptable to the Russians unless they are getting some sort of quid pro quo, the more so since they banished his mistress to Siberia and then brought her back after a certain delay.”

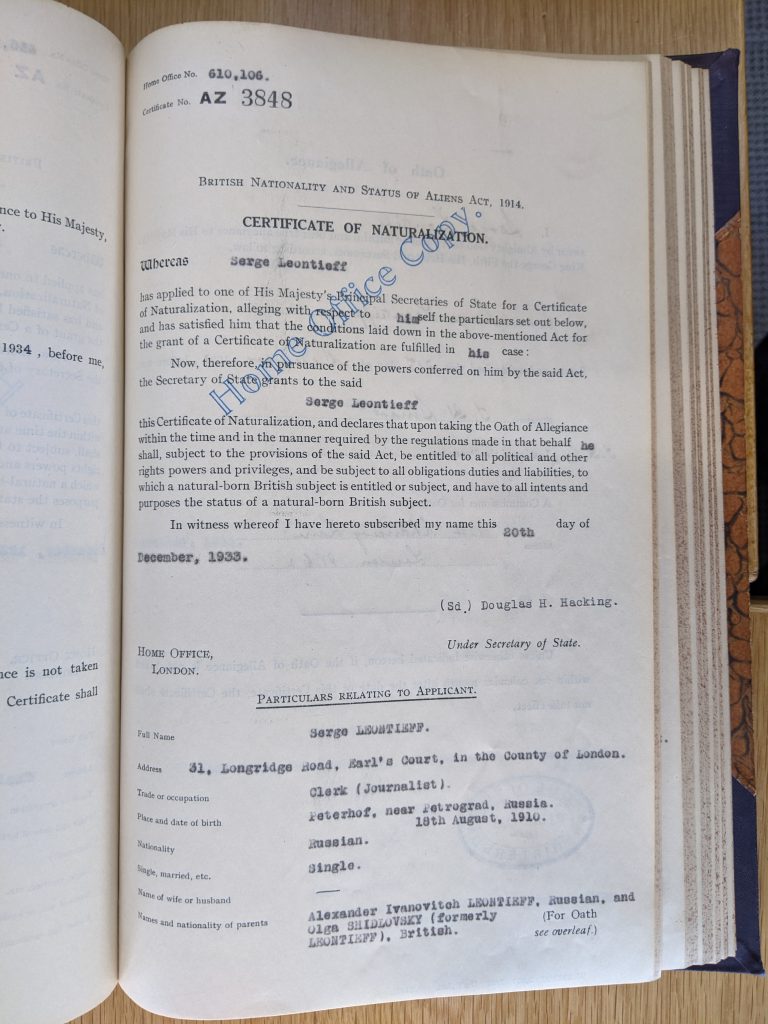

Boyle also revealed something astounding. George Graham’s real name was Serge Leontieff, and he was a White Russian. Now, it would have been questionable enough for the Intelligence Corps to have recruited someone with such a history without a very careful background check, but to send him on a mission to Moscow, even under deep cover and an anglicised name, was surely irresponsible. If he truly was a White Russian (i.e. a person born in tsarist times, of probable aristocratic lineage, and against the revolution), the Soviets would be merciless, either rejecting him immediately, or accepting him in the knowledge that they would be able to suborn him by threats to surviving family members. And if he had arrived, apparently freely, from the Soviet Union at some later stage (perhaps in the early 1930s), that should have rung alarm bells about the circumstances of his escape, and the purpose of his arrival. No Soviet citizen was able to leave the country at that time without some ulterior motive on the government’s part.

A certain Serge Leontieff received his naturalization papers in London on December 20, 1933. He had been born in Peterhof, near Petrograd, on August 18, 1910, and his parents were given as Alexander Ivanovitch Leontieff and Olga Shidlovsky (formerly Leontieff), with Olga having British citizenship. Serge was single, gave his trade as Clerk (Journalist), and lived in Earl’s Court. The records suggest that his parents had been accepted to the UK some years before, but the circumstances of Olga’s second marriage are not clear. Nor is it explained how and why she alone took up British citizenship. A newspaper report (in the Winnipeg Tribune) shows that Alexander Leontieff, a former Colonel of the Imperial Guard, led the Old Moscow Balalaika Orchestra at a concert in London on May 30, 1931. Another short piece (in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram) informs us that on November 10, 1934, Alexey Leontieff, a former colonel in the Czarist Army, and manager of a local machine supply office, faced a firing-squad in Novosibirsk, for failing to provide proper machinery to a nearby collective farm. Were Alexander and Alexey brothers? And did ‘Serge’ want to try to determine what happened to his uncle? Pure conjecture at this time. Yet Graham’s past would turn out to be more complicated.

4. Liddell’s Moves:

In this context of mismanagement and deception Guy Liddell faced the combined challenge of the ELLI threat, and the disturbing news about SOE security lapses in Moscow, as well as concerns about his own professional status in MI5. (For a more detailed analysis of Liddell’s career, and the events of this time, I recommend to readers that they turn to https://coldspur.com/guy-liddell-a-re-assessment/ ).

a) Petrie and Sillitoe:

Guy Liddell had a difficult time with his boss, David Petrie, during this period. Liddell admitted that he lost his temper with Petrie back in February, and threatened to resign, over what seemed to be a relatively minor matter concerning the Channel Islands, when Petrie interfered after forgetting what Liddell had briefed him on beforehand. When Petrie planned his retirement (his sixty-fifth birthday fell on September 9, 1945), and considered who should replace him, Liddell was not his recommendation. Jasper Harker, Petrie’s nominal deputy, was not yet sixty, but was not a candidate, and retired in 1946. Various accounts have been put forward as to why Liddell was overlooked at this time, but the influence of the Attlee government, and MI5’s reputation for being anti-socialist, must have contributed to the decision to bring in an outsider. Findlater Stewart, so busy in trying to define the future of the intelligence services, had wanted Petrie to stay on for a couple of years ‘to put MI5 on a good peace-time footing’ (as Howard Caccia told Liddell), but he was overruled.

Petrie’s behaviour was decidedly odd. John Curry gave hints of his enormous stress and disappointment at the end of the war, hinting at ‘tragedy’, as if Petrie would have been glad to get out of the hothouse. Yet he took an unconscionably long time in leaving, and botched the handover. Liddell found him very listless over the Gouzenko case: on October 18, he recorded a frustrating meeting he had with Hollis and Petrie after Hollis’s return from Canada, when the two officers were seeking some high-level directive on signals security. Petrie did not want to speak to the Prime Minister (Attlee) himself, and merely suggested that Liddell and Hollis talk the matter over with Menzies, and have him make the approach to Downing Street. Overall, it was a poor performance by Petrie: he neglected to solve the problem of Soviet counter-intelligence himself, he failed to give Liddell the authority to do so, and he protected his own broken structures, all while knowing that his successor would be bewildered by the challenge.

Moreover, Petrie did not have the guts to inform Liddell himself that the next Director-General would be a policeman, Percy Sillitoe, the Chief Constable of Kent. Liddell heard the rumour on December 10, when Desmond Orr, a member of Petrie’s staff, and the liaison with the War Office told Liddell that he had learned ‘on good authority’ that a policeman in the UK had been appointed. The story was relayed to Liddell more strongly on December 17, so Liddell went to Petrie’s office, where the news was confirmed. Petrie, rather uncomfortably, explained that the choice had been between Liddell and Sillitoe, but that (as Liddell recorded Petrie’s words) ‘the Committee possibly having thought that it might be better that I should have my hands free to deal with the Intelligence side of things’. This was a weaselly and sophistical excuse – what else was MI5, if not ‘Intelligence’? And Petrie hypocritically did not divulge to Liddell the recommendations he had made in a report submitted in 1943, which specifically called for an external career police officer to take over. Liddell had been invited to appear before the Whitehall interviewing committee, but his diary entry for the interview, on November 14, does not reflect a convincing and authoritative display. The committee had seen several other impressive candidates (e.g. Strong, Eisenhower’s intelligence chief, and Penney, a senior military intelligence officer), and was perhaps going through the motions with Liddell. As confirmation of his shiftiness, Petrie did not want to make any formal announcement: he wanted the news to ‘leak out’.

Liddell was naturally very disappointed, and listed his reasons why choosing an outsider policeman was a bad idea, for practical considerations, and especially for morale. But then Petrie told him that he was going to stay on until April 1946, which left Liddell in a very invidious position. Petrie would be filling ‘Shillito’ (as Liddell’s secretary mis-spelled the newcomer’s name) with all the wrong ideas (such as separating Russian espionage from F Division, and inserting it in B), while Liddell and his team would have to perform the grunt-work of implementing new organisation and policies. Liddell eventually met Sillitoe – but not until February 8, his judgment being that he seemed ‘a pleasant person’. That had more the ring of Barbara Pym describing a new curate despatched to the parish by Lambeth Palace than a senior officer heralding a steely new director-general ready to take on the Gremlin from the Kremlin. MI5 needed more than leadership by a nice chap.

Yet one more clash with Petrie occurred. Liddell was keen to pay a visit to the United States – ostensibly to reinforce good relations with the FBI, but also for personal reasons. Rather than simply declare his intentions, he sought permission, and raised the matter with Petrie on February 4. Budgets must have been tight, and Petrie was not enthusiastic. Hollis had recently journeyed there, and Lord Rothschild also had a visit coming up. Petrie wanted to have Liddell around in March, when Sillitoe would be visiting regularly, and suggested he go in June instead. For reasons that will become apparent, that did not suit Liddell, and a compromise was suggested, whereby Liddell would pay half his passage if he insisted on leaving sooner. The next day, Liddell accepted those terms, but felt insulted by the way he had been treated. “I feel rather like a schoolboy who has been accused of wangling a day’s holiday on the excuse that he is going to his aunt’s funeral.” There was, however, a grain of truth behind that implicit grievance.

b) Security Issues: