“In view of the damage that Sonia helped to inflict on Western interests through her assistance to Fuchs alone, the suggestion by some authors that she was some kind of double agent being used by MI5 as a means of passing misleading information to the Russians is ridiculous. In a BBC radio programme in 2002, Markus Wolf, the former spymaster of the East German intelligence agency the Stasi, who knew Sonia in her later years, categorically denied that she had been any kind of ‘double’. Released MI5 documents confirm that view.” (Chapman Pincher, in Treachery, p 208)

When Chapman Pincher wrote these sentences, he was guilty of what could be called Professor Hinsley Syndrome, a pattern of hinting at unexplained rumours, and then pretending to refute them by simple denial. Careful readers of coldspur will recall, from Sonia’s Radio, Chapter 5, that I quoted the following utterance from the official historian of British intelligence in World War II: “There is no truth in the much-publicised claim that the British authorities made use of the ‘Lucy’ ring, a Soviet espionage organisation which operated from Switzerland, to forward intelligence to Moscow”.

Now, if you are assigned the role of ‘official’ historian of anything, my view is that you should follow these precepts:

- Never dignify a rumour that you want stifled, whether you believe it has merit or not, by even mentioning it.

- If you are going to identify a rumour, explain what it is, where it derives, who is promoting it, and on what grounds the claims in it are made.

- If you then want to deflate the rumour, explain in a detailed fashion why it should be disregarded.

Otherwise, all you do is provoke interest, and encourage readers to postulate ‘There’s no smoke without fire’ and wonder ‘what is he or she trying to hide?’

Pincher was not an official historian (nor a very disciplined one), but the outcome is the same. Moreover, he refers to ‘some authors’, which suggests that the culprit was not a one-man-band. Yet the only author that I can identify who suggests anything close is Jerry Dan, the nom de plume of one Nigel Bance, who in his Ultimate Deception, an odd compilation of fact and fiction, implies that a high-level plot, approved by Churchill, funnelled information about the Manhattan project (the US-based exercise that researched and developed atomic weaponry) through Sonia to Stalin. But the channelling of disinformation through a known enemy agent does not automatically mean that that person becomes a double agent. A double agent is a turned spy, switching allegiances, perhaps under threat of death, to become a vehicle for the side that captures him or her. There is no evidence that Sonia was ever confronted and pressured to be controlled by the British, or subsequently consented to such a move. On the contrary: the little evidence we have suggests that MI5 officers recognised her as a sometime Soviet spy, declared openly to her that they believed she had been inactive during her time in the UK, and tried to haul her in only after she had flown the coop. (Some of this archival evidence may be disinformation to muddy the waters, of course.)

Pincher’s statement is thus problematic in many aspects. No source for the claim that Sonia was a double agent is identified. Wolf’s denial means nothing, as all it declares is that Sonia was never turned. Pincher’s claim that MI5 documents ‘confirm this view’ is completely hollow: it is almost impossible for archives to prove a negative, and he does not identify what files support his case. However, by expressing the rumour in this way, Pincher’s dismissal of the claim does not explicitly reject the more nuanced notion that Sonia may have been fed information (or disinformation, or a mixture of the two) to pass on to her bosses in Moscow, without ever acting as a double agent. Lastly, and most significant of all, if the implication is that Sonia was manipulated as ‘some kind of double agent’, it would suggest that British intelligence knew that her role in the United Kingdom was that of a Soviet agent in communication with her controls in Moscow. Why, then, did they do nothing about it? Exploring this avenue would have severely damaged Pincher’s theory that Sonia was able to thrive solely because of the efforts of her protector, Roger Hollis.

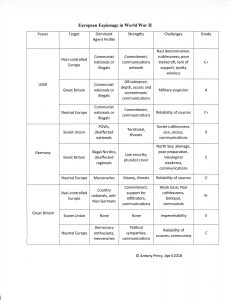

European Espionage Patterns in WWII

Before I explore the various accounts that might bolster the claim that British Intelligence could have attempted to mirror its success with the Double-Cross System (in which the complete Abwehr-supplied network of agents in the United Kingdom was turned and managed) by taking some measure of control over Soviet spies, it will be useful to apply some structure to the variety of espionage efforts that were undertaken in Europe during World War II, and then to analyse what made the Double-Cross operation successful.

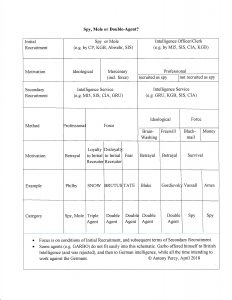

I have thus created the following chart:

Please double-click on the image to see it fully.

Please double-click on the image to see it fully.

I do not believe any historian has produced a similar classification, as comparative studies of intelligence in World War II are thin on the ground, and tend to skim the surface of what is a highly intriguing subject. Readers may have suggestions as to how to improve or amplify the chart, but I think that, as it stands, it can teach several useful lessons.

- The Soviet Union was far more energetic in spying against its allies than it was against its enemy. The main reason that this conclusion is true is that, in the couple of decades before the war, the Soviet Union had treated Great Britain (and its Empire) as the major enemy, and had made espionage investments accordingly. Lenin believed that the inevitable worldwide revolution would break out in Germany first, only for his successors to watch how communists in that country were either quietened, exiled, imprisoned, or killed. Thus the build-up of the Red Orchestra, the Soviet Union’s espionage network in Western Europe, was a slower and arduous process. Yet the dividends of recruiting Soviet spies in Britain in the early 1930s, and inserting them into the fabric of British institutions, paid off handsomely by the time the war started. While its network in Germany was gradually mopped up by German counter-intelligence, Moscow could take advantage of British accommodation of, and indulgence to, Soviet sympathisers in government and the intelligence services to gain detailed secrets about Nazi war-plans from its ally. These revelations dwarfed what information the British government was prepared to pass on openly.

- It was very difficult to sustain an intelligence network in a totalitarian country. If the country being spied upon is a ruthless, totalitarian state that has little respect for human life, the life expectancy of agents trying to report its secrets will be short. Nazi Germany used its radio-detection and location-finding apparatus mechanisms ruthlessly to track down illegal broadcasts. Suspects and those caught red-handed were tortured, confessions with names of contacts extracted, and the victims normally executed. Soviet tradecraft was not solid enough to isolate spies from each other, and the bosses in Moscow had little concern about the capture of their agents. The Red Orchestra was wrapped up in Germany by August 1942. In the latter stages of the war, the NKVD parachuted into Germany spies who were hopelessly unprepared and ill-equipped for what they would face. Planting spies in the Soviet Union was even more difficult, owing to the distances involved, and the challenges in getting any information out. Instead, the Nazis and the Soviets both looked to prisoners-of-war as a primary source of intelligence.

- Agents in neutral countries were of dubious reliability. While Britain’s SIS should have been able to have in place a productive agent network in Europe at the time war broke out, a combination of spending restrictions and incompetence (e.g. the Venlo incident in the Netherlands) meant that its forces were thin. A shadow structure (the ‘Z’ organisation) was developed under Colonel Dansey, but that was also pared back. As the Nazi war machine rolled over Europe, the residual centres of espionage activity in Europe in WII were in the neutral countries, predominantly Portugal, Switzerland, and Turkey, with Spain and Sweden in the background. All participants had agents in the three main countries, constantly looking over their shoulders. Yet those claiming to have access to proprietary information would often offer it for financial reasons, would not offer it exclusively to one party, and it was not always reliable. In Switzerland, some members of the Soviet network were also working for British intelligence, and, in addition, informants passed on their secrets to Swiss intelligence. Thus espionage on neutral territory was always a speculative venture, as the motivations and intentions of agents not under direct control could not reliably be assessed. British intelligence was always fearful that anti-Nazis might turn out to be fervent communists – as was frequently the case in Nazi-occupied countries.

- Fascism attracted fewer espionage activists than did communism. While communism had an international and idealistic appeal, and thus exerted a broad influence that crossed national boundaries, the German style of Fascism, especially when its cruelty became apparent, had fewer ideological sympathisers. For example, the feared ‘Fifth Column’ in Britain petered out: few fascist enthusiasts wanted Hitler as a future dictator. Soviet citizens who initially welcomed German troops as liberators from Communism were soon subjected to the brutality of Nazi methods of oppression, and thus quickly antagonized. Thus, as the Nazi empire extended its range, apart from the rise of notable quislings and their followers, and an ugly contribution by anti-Semitic collaborators, kernels of civic populations eager to abet Nazi successes were thin on the ground. The Nazis relied on criminals, hoodlums, and the morally bankrupt to assist in their counter-intelligence efforts. Even Germany’s Abwehr was sprinkled with patriotic Germans who wanted Hitler to fail, as the failed coup against him proved. In addition, Hitler, as aggressor, did not strongly believe in the value of intelligence, trusting his army and weapons to crush opposition without the need for complementary information on the activities of his adversaries. Only when faced with the Allied assault on Europe did the role of intelligence gain more significance for the Wehrmacht.

- British counter-intelligence versus Germany was in direct contrast to its performance against the Soviet Union. The major intelligence successes for Britain were the decryption of Enigma traffic, and the management of the Double-Cross System, by which Germany’s complete network of agents in Britain was turned and manipulated. This latter programme, coupled with realistic illusory effects about non-existent battalions, contributed largely to the success of the Normandy landings. While Germany also deployed such tactics (such as the Englandspiel, by which SOE agents captured in the Netherlands – and France – sent positive messages to London to entice further landings), nothing approached the comprehensiveness and thoroughness by which British intelligence provided a mixture of facts and disinformation to help misdirect German suppositions about the location of the invasion of France in 1944. This success was in dynamic contrast to MI5’s woeful performance against the Soviet Union, where a lack of discipline in assessing the threat of homegrown communists, and a weak and appeasing stance against the Soviet Union, left a large network of spies untouched. This failure resulted from a reluctance to accept that the country, while a temporary ally against Nazi Germany, remained a permanent adversary and threat.

- Wireless was the greatest asset in espionage, and its biggest liability. Couriers were a valuable mechanism for passing on secrets at the outbreak of war, but the Nazi invasions of much of Europe made their use far more difficult – such as British communications from Switzerland. Surprisingly, perhaps, invisible writing (in letters passed through the mail) was still a useful technique. When Soviet wirelesses failed in western Europe, the Communists had to resort to couriers, but the passage of material in diplomatic bags from (say) London to Moscow took several weeks, thus putting more pressure on speedier radio communications. Britain’s ability to mount more aggressive work through the XX system increased markedly when GARBO acquired a wireless transmitter. Wireless messages were faster, but could be intercepted, and thus required encryption. Much of the British counter-intelligence success was gained by decrypting Enigma and hand-cypher traffic, such as the Abwehr’s reports from Madrid and Paris to Berlin that transcribed the reports given by XX agents to their German handlers, which thus confirmed that the Double-Cross bait had been accepted. The Battle of the Atlantic was won and lost by the fact that Germany and Britain at different stages had an advantage in deciphering their adversaries’ open communications on the air. At the same time, within any country, techniques in location-finding improved quickly, leading to more portable equipment and greater precision in tracing illicit communications. Telephonic cable communications, such as those possible on natively controlled territory, remained highly secure.

Yet the most startling fact is how inconsistently Britain’s counter-intelligence performed. Germany’s utter failure to deploy agents successfully in Britain (and thus Britain’s complete success in nullifying them) was diametrically different from the Soviet Union’s complete success in penetrating Britain’s defences (and Britain’s corresponding utter failure in countering such subversion). This cannot be ascribed solely to the role of the Soviet Union as an ally. That transformation occurred only in June 1941 (Barbarossa), and two years of bitter experiences later, the new threat that the Soviet Union represented was recognised – admittedly sooner by military and intelligence officers than by diplomats and politicians. Britain knew about a Soviet espionage campaign, and tolerated it. Stalin did not regard the alliance against Hitler as a reason for pausing in the quest for secrets from his partners, nor would he have expected Great Britain and the United States to loosen their efforts. I have written before about the apparent belief by Dansey that he could undermine the Soviet espionage network, in a fashion perhaps similar to the Double-Cross System. But what was different is that British counter-intelligence officers massively underestimated the scope and depth of the Moscow-controlled espionage that was going on under their noses.

The Double-Cross Operation

The Double-Cross operation was conceived as early as November 1940, when Britain was essentially fighting alone, and still under threat from invasion. Historians almost universally accept that its success in convincing German Intelligence that its agents were passing on accurate reports on Allied military plans for the invasion of Europe consisted a vital part of the deception campaign. Why was it so successful? What lessons can be learned from it? Analysis of it (notably by Masterman, Howard, Andrew, West, Holt, Hastings, and Macintyre) indicates a number of vital features:

- Ill-preparedness of inserted agents: It was difficult enough to insert agents across the North Sea, either by boat or by parachute. Those that did make the journey were not well-prepared, as far as their knowledge of British customs and the language, and the reliability of their wireless equipment (if they had it), were concerned.

- Inclusivity: By early 1942, MI5 was confident that it had trapped 80% of all spies, through interrogation and interception of radio messages, and by the summer, that it was in control of all. (Though Guy Liddell, head of B Division in MI5, would in his Diaries later cast doubt on the expertise behind such claims.) If spies refused to be turned and to cooperate, they were executed.

- Authenticity: Only authorized spies were used in the operation. MI5 initiated no ‘coat-trailing’, namely offering up volunteers to the Abwehr. (GARBO had, admittedly, offered his services in Spain, after being rejected by the British, and TREASURE had approached the Abwehr in Paris after declining an offer to work for German intelligence before the war.) The motivations and psychologies of those who committed to turn were severely tested before being approved for deception work.

- Patience: The operation was undertaken by a passive requirement to keep agents viable, and learn more about Nazi invasion plans – a defensive manoeuvre – and only as the war progressed was it converted into an offensive strategy, namely that of deceiving the enemy about the eventual Normandy landings. Subsidiary objectives (such as learning more about Enigma encryptions) were clearly laid out. This kept the team very focused.

- Plausibility: An immense effort was expended in ensuring that the messages sent by double agents were plausible, namely that the disinformation was combined with a high degree of realism concerning events, location, contacts, etc. and a sprinkling of facts that could be verified. Painstaking details were created around the lives of the fictional spies in GARBO’s network.

- Isolation: Solid tradecraft was used to ensure that the double agents did not know about each other, and thus never had a chance to exchange notes about the experience. Agents were rarely allowed to transmit messages themselves.

- Verifiability: Messages that were transmitted on behalf of double agents to controllers in Madrid would later be re-sent by the Abwehr to Berlin, and thus the XX Committee, able to review transcripts of Enigma traffic provided by Bletchley Park, could verify that their information had been received and accepted.

- Secrecy: While the XX Committee had representation by the Intelligence Services and the Armed Forces, a high degree of secrecy was demanded and maintained. Even the Joint Intelligence Committee was not initially aware of its activities. (Yet Anthony Blunt, MI5’s representative on various committees dealing with strategic deception, gave his Moscow masters a full account of what was happening.)

- Integrity: The Committee was very sensitive to its mission, and conscious that, by delivering disinformation, the process might have unexpected consequences (such as the attempted rerouting of V1 and V2 bombs short of London.) No decision was made casually: highly sensitive decisions were made very carefully.

- Leadership: The committee was ably led by John Masterman, a tactful and persuasive chairman, who inspired confidence, and commanded attendance at meetings that were held every week until the end of the war.

The success was also abetted by the defects of the Abwehr organization. It was a failing of human nature for officers in the Abwehr to want to believe that their hand-picked agents were successful. Maintaining the story that their agents were trustworthy and valuable was a career-helping activity, the alternative for some officers perhaps being sent to the Russian Front. The voices of those that queried whether the agents were in fact being controlled by the British were quickly quashed. There were even Abwehr officers (e.g. Jebsen) who were surely aware of what was happening, but desired an Allied victory. (Jebsen’s refusal to talk, when arrested by the Gestapo, was critical to the success of FORTITUDE, part of the OVERLORD deception plan named BODYGUARD.) Kliemann (who controlled TREASURE) was an amateur, an Austrian more concerned about his romantic life than serious spycraft, and he did not have his heart in the business.

Yet some exposures could have fatally damaged the exercise. The agents’ true loyalty was always suspect: they could have inserted codes into their wireless transmissions to indicate that they were fake, and thus experienced operators were brought in to adopt their transmission patterns, and act as surrogates. One double agent, SNOW, was suspected of being a triple agent, and was withdrawn. TREASURE was immediately suspended when MI5 learned that she had omitted to inform her handlers about a special code she was to insert into messages to indicate to the Abwehr that she was being controlled. Despite their confidence over radio transmission detection, intelligence officers were always fearful of an undetected spy in their midst, and had to be wary of reports emanating from the embassies of ‘neutral’ countries, which might contradict the information the XX Committee was disseminating. There were occasional accidental releases of intelligence hinting at the operation, or uncannily similar bulletins issued by discrete agents, that were fortunately not picked up by the enemy.

Finally, there was the major unexplained phenomenon of undetected radio traffic. Given the progress that the Gestapo had made in improvements in radio direction-finding and location, it should have been obvious for the Germans to assume that the British had made similar advances. It is still astonishing to consider the ability with which agents were apparently allowed to move about Britain, carrying bulky wireless equipment, and to install themselves invisibly in lodgings where they were able to transmit lengthy, wordy, messages without their ever being detected, and without the Abwehr ever seriously analysing why and how their agents were able to operate so freely. The official historian, Michael Howard, provocatively wrote that ‘their [the agents’] transmissions had to evade detection by the security authorities’. He was describing the challenges from the perspective of the Abwehr, but, pari passu, he sharply identified how canny a game the XX Committee had to play, with turned agents operating wireless equipment that its own detection powers would have to overlook. He left unexplained the extent to which RSS, the Radio Security Service, had been brought in to the secret, and whether the network’s integrity was kept intact by virtue of a) the deployment of transmission techniques that managed to evade the detectors, or b) the guidance by influential members of RSS who would have been capable of ensuring that the signals were ignored.

Howard then appeared to explain things, but in an unconvincing way: he informed us that Lieut Col TA (‘Tar’) Robertson (of B1A in MI5) on July 15, 1942 told the Y Board, the committee responsible for overall wireless monitoring, that ‘the RSS had discovered no uncontrolled agents reporting’, an observation that would appear to confirm that the RSS was aware of the transmissions of authorised double agents, could discriminate between them and possible illicit occurrences, and was confident, presumably, that no felonious transmissions had gone undetected. (Robertson’s statement granted the RSS an omnipotence that Guy Liddell would repeatedly question in his Diaries.) Howard also related how 500 transmissions were made between January 1944 and D-Day: the ‘security authorities’ presumably did not pick them up, and somehow the Abwehr must have been convinced of their undetectability. What Howard did not record was the fact that, in March 1943, the Abwehr instructed the agent GARBO to imitate call-signs of the British Army, whose messages were not analysed by the Radio Security Service. This reality immediately undermines Robertson’s confident assertion, and leaves unanswered many questions concerning the stumbles in Britain’s radio detection-finding operation. Howard never resolved this paradox, which is a highly controversial topic, and one to which I shall return in a future article.

(For a refresher on the activities of the RSS, I refer you to Sonia’s Radio: Chapter 9)

Application of XX to the Soviets?

It is in this context – of a disciplined procedure for handling double agents, complemented by a fear that the enemy would suddenly realise that the exercise was a total sham (owing to exposures such as the efficacy of Britain’s radio detection-finding techniques) – that any inspection of possible manipulation of Soviet agents must be understood.

The story starts with Colonel Dansey’s Z Organisation, a shadow espionage service set up within SIS in the late 1930s. The experts seem to agree that some of the agents who worked for the Soviet subsection of the so-called ‘Rote Kapelle’ (‘Red Orchestra’) in Switzerland were also working for the British, whose strongest remaining ‘Z’ outstation, at the outbreak of war, was in Geneva. In Sonia’s Radio: Chapter 6, I present the case for concluding that Alexander Foote, one of the leading wireless operators in the Swiss network (‘Rote Drei’), was actually a double agent planted by Dansey. Foote had perjured himself to the Swiss authorities when providing evidence that Sonia’s husband, Rolf Hamburger, had committed adultery in London with Sonia’s sister, thus enabling Sonia to enter an arranged, and probably bigamous, marriage with Foote’s colleague Len Beurton. This, in turn, allowed her to gain British citizenship (the objective of her bosses in Moscow), and re-enter Britain as a citizen, whereafter she was able to act as a courier for the atomic scientist and spy, Klaus Fuchs.

Credulity is strained to accept that the British Intelligence Services, knowing that a Soviet agent, one of the infamous Kuczynski family, whose members were the bane of the British authorities in defending subversive Communists in Britain and preventing their being expelled, would not attempt to confound her plans for migrating to the United Kingdom at a time when the Soviet Union was an ally of Nazi Germany. On the contrary, her marriage and her transport were facilitated, and lower members of MI5, the domestic security service, were misled about the facts of her application. The obvious conclusion would be that Dansey hoped to be able to manipulate her when she was safely installed, as a means of monitoring and intercepting her radio transmissions with a view to decipherment (since the provision of a ‘crib’ would have greatly facilitated the process), or as a way of planting false information on her, or as a means of identifying her contacts, or for some combination of the above purposes. According to his biographers, Dansey had been a pioneer of double-cross operations in World War I, strongly believing that, if you convinced your enemy that his agent is ‘loose and operating’, it was ‘of infinitely greater value than having a dead man’.

Complementary to this analysis are the well-documented assertions, despite the blunt denial by the official historian of wartime British Intelligence of such, that the British authorities used members of the Rote Drei to pass on to the Soviets thickly veiled summaries of highly confidential intelligence gained from decryption of Nazi signals traffic (‘ULTRA’). I describe these in Sonia’s Radio: Chapter 4. Further reading appears to confirm the accuracy of this interpretation of the exercise: for example, I have recently read Hidden Weapons: Allied Secret or Undercover Services in World War II, by Basil Collier, who received ULTRA material when working in Fighter Command. Collier added to the chorus of experts who suggest that the official explanation was incorrect when he wrote, in 1982: “I have always supposed that Lucy received from the British the substance of Enigma decrypts, but this has been authoritatively denied.”

According to the more reliable accounts, Rudolf Roessler (LUCY), the primary source of information to the Soviets about the Nazi battle-plans, was not recruited until the autumn of 1942. Great Britain had become frustrated with trying to pass massaged intelligence derived from the ULTRA programme through its military mission in Moscow, and had thus decided to exploit its contacts in Switzerland. Thus the intelligence provided to Lucy was authentic, but not genuine: the information passed was accurate, but its authorship was concealed. By the Law of Unintended Consequences, however, the project had the effect of reducing Stalin’s trust rather than provoking his gratitude. The Soviet leader naturally wanted to know the source of such intelligence, and since he was receiving comprehensive transcriptions of ULTRA traffic from his well-placed spies within Britain’s political infrastructure, he naturally mistrusted the LUCY material, judged Britain’s official cooperation to be minimal, and wondered whether he was being manipulated. Thus the whole programme rebounded poorly on the British Intelligence Services. They had a poor understanding of the psychology of their dictator-ally, and they were blithely ignorant of the fact that the task of passing on information was being executed more efficiently by traitors in their midst.

The LUCY project was thus one concerning information – intelligence, even though its method of delivery was deceptive. Yet the main campaign of disinformation – if indeed there was one – came earlier. And, if Chapman Pincher’s disguised references can be interpreted correctly, it concerned research into atomic weapons.

Pincher clearly had read Jerry Dan’s 2003 work, Ultimate Deception, since he cites it in his attempt to pin the revelation of the Quebec Agreement to Sonia. Ultimate Deception, subtitled How Stalin stole the Bomb, is an extraordinary work, primarily because it is very difficult to separate fact from fiction. It includes as appendices a number of documents from the NKVD/KGB archives, which look as if they are genuine, but perhaps not authentic – i.e. they were assuredly crafted by qualified officials, but may have been written and inserted some time after the fact, to deliver an alternative story. [see below] The main thrust of Dan’s account seems to be that the British government engineered a disinformation campaign to convince the Soviets that British interest in nuclear weaponry was nugatory, while spies in its midst (most surprisingly, the newly-revealed Soviet sympathiser John Anderson, Home Secretary, Lord President of the Council, and then Chancellor of the Exchequer in Churchill’s wartime coalition administration) facilitated the delivery of atomic secrets to Stalin, thus accelerating his development of the bomb.

The blurb for Ultimate Deception is unhelpful: “Is the ULTIMATE DECEPTION merely historical fiction or is it a genuine account of an extraordinary wartime episode?”, it challenges us. If the author, editor and publisher abandon their readers so equivocally, I am not going to spend any more time here analysing the strengths and defects of this work. Pincher hinted at other sources. What else can be found?

The precise role of Klaus Fuchs has come under the microscope. In his very careful biography of Fuchs, The Spy Who Changed the World, Mike Rossiter describes a puzzling series of events. Rossiter has studied documents that indicate that, after the war, when he returned to a position at AERE Harwell, Fuchs provided confidential information to the British on the construction of nuclear reactors and other topics that he had gained from his time in the USA at Los Alamos. The implication here is that Fuchs had been spying on the Americans. President Truman had signed the McMahon Act on August 1, 1946, which made it illegal for the United States to share nuclear information with any other country, thus brusquely annulling the commitment to technology sharing embodied in the Quebec Agreement of 1943. (According to Graham Farmelo’s account in Churchill’s Bomb (2013), Truman’s officials could not find a copy of the Quebec Agreement, and had to request a copy from London.) Coincidentally, August 1, 1946 was the day that Fuchs took up his position at Harwell. Prime Minister Attlee was seriously peeved at Truman’s betrayal: it would not be surprising if Fuchs had been approached with the goal of maximising knowledge that would contribute to Britain’s now independent atomic weapons programme. Yet picking his brains over information learned before the McMahon Act was passed can hardly count as espionage.

Rossiter believes this transaction may have affected Fuchs’s confession. Rossiter discovered at the National Archives a file titled ‘Miscellaneous Super Bomb Notes by Klaus Fuchs’, dated 1954, but when he went back to re-inspect it in November 2013, it had been withdrawn at the request of the Ministry of Defence, as if the idea of collaboration between Fuchs and the Ministry were an item of some embarrassment. If this were so, it is perhaps surprising that Fuchs did not bring this matter up with his lawyer, as he surely was expecting a stiff sentence. The episode could even hint instead at influence by bureaucrats who knew what Fuchs was up to, and even approved it. After all, in the USA, Roosevelt’s nefarious emissary, Joseph Davies, had stated that Soviet stealing of atomic secrets was morally justified (Ottawa Citizen, February 19, 1946, according to David Levy). Yet, if it was not considered embarrassing to mention Fuchs in this context in 1954, why should it be so in 2013? Despite this unseemly and provocative attempt at a cover-up, there seems to be no indication of any controlled release of information (or disinformation) to Soviet Russia using Fuchs as an intermediary.

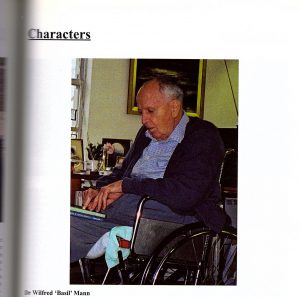

Then there is the case of Wilfrid Basil Mann, whose role in the saga of atomic secrets remains elusive. I have written about Mann before (see Mann Overboard!), pointing out the discrepancies in the account of the scientist’s negotiations to leave the Tube Alloys project in London, and gain a transfer to Washington. This career move suggested to me connivance over a clandestine move by the British authorities, which now seems to be supported in other accounts. Reliable testimony on Mann’s life is sparse, but I note that Nigel West, in his history of the stealing of atomic secrets, Mortal Crimes (2004), wrote of Mann that he was ‘cultivated by the KGB to the point that he was run as a double agent by the CIA’s Counterintelligence Staff’, thus finessing the question of whether Mann had been recruited by SIS (see below). It was not clear at the time where West derived his information; West also appears to contradict the terminological rules he set up himself as to the nature of a ‘double agent’. (I have developed a diagram that sets out to distinguish ‘spies’ and ‘double agents’ based on their initial recruitment and allegiance, and later conversions or treachery: it must be noted that, in order to be considered a ‘double agent’, the organization the agent is then working for must know that he is a confirmed agent of a foreign power. See here:

Andrew Lownie, who published a biography of Guy Burgess in 2016, then found further incriminating evidence in the papers of Patrick Reilly (which I have since confirmed) that indicated that Mann was a Soviet spy (cryptonym MALONE) disclosing confidential intelligence to his masters. Lownie referred to the thinly veiled description of Mann in Climate of Treason (1979), where Andrew Boyle wrote that ‘Basil’ was identified and ‘broke down quickly and easily’. “He was given the choice of continuing to work for the Russians as a double agent under CIA direction, or face prosecution under American law. He agreed to provide Maclean with useless information in return for immunity from prosecution and American citizenship”, wrote Lownie. Boyle’s account, nourished by CIA contacts, explained that Mann had been tailed because of his contact with Donald Maclean, and, having been turned, was tutored (by James Angleton) to advise Maclean which information the later should extract from the US Energy Commission’s headquarters, and then pass on to the Soviets. Thus we have a clear glimpse of a disinformation exercise. Yet why the Americans thought it useful to supply any information to the Russians at this time, and why they did not haul Maclean in if they had proof he was a spy, is not clear. Despite Mann’s having been ‘turned’, he was not ‘controlled’, and still could have signalled to his Soviet handler, or Maclean himself, that the latter was under suspicion, which would, while increasing Maclean’s emotional instability, probably also have accelerated his flight.

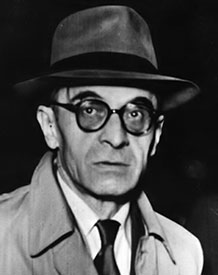

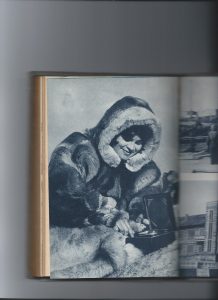

In 2000, when Mann was 92 years old, Dan tracked him down to a retirement home in Owings Mills, Maryland. He did not gain much fresh information from his prey, although he did extract a confession from Mann that he was indeed ‘the Fifth Man’ (the subject of his rhetorically-titled memoir, Was There a Fifth Man?). Since John Cairncross had long been outed as Number 5, that admission was perhaps surprising. Dan appended the photograph he took of Mann (below) with the following (partial) text: “After a short period with the British nuclear programme in Canada Mann returned to Washington as a member of MI6, advising Donald Maclean on atomic matters, reporting to Welsh, and liaising with James Angleton of the CIA. Under suspicion after Maclean’s defection, Mann was replaced by Dr Robert Press, an attaché at the Embassy. From 1951-1980 Mann worked at the US National Bureau of Standards, and headed the radioactivity department. He later became a naturalized American citizen, but was accused in 1979 of being a Soviet agent, the same year Anthony Blunt was publicly named a wartime spy. Mann was a double agent, working for both British Intelligence and the NKVD, the Russians believing he was part of the British wartime Double X operation. During the war and in the post-war period Mann had been in regular contact with Gorsky, Kukin, Kreshin and Barkovsky. The author visited Mann in Rainbow Hall, a retirement home in Owings Mills, near Baltimore, just months before he died in March 2001. KGB veterans confirm that Mann was a Soviet agent of considerable influence. His codename in NKVD transmissions from London was Malone. In his debriefing session in Moscow Philby argued that Mann was unstable and his information should not be relied upon.”

Wilfrid Basil Mann in 2000

Nigel West agrees, in his Dictionary of British Intelligence, that Soviet archives appear to confirm that the spy identified as MALONE was indeed Mann. And here is the relevant page from the NKVD archive, as presented by Dan:

It is dated August 23, 1945, and confirms that MALONE is an ‘agent of the NKGB, employee of the special technical bureau of the second department of the intelligence service [SIS]’. Yet this chronology is complicated by the fact that Mann, in his memoir, states that he returned to the UK from Washington on 29 September 1945, docking at Southampton. This archival entry, however, reports a meeting between the head of the Department of Industrial and Scientific Research, [Sir Edward] Appleton, attended by MALONE, that took place on August 17. If Mann was truly MALONE, and had in fact been debriefed after his return, either he or the NKGB archive was falsifying the record. Mann also dissembles about his appointment to the ‘civil service’, after which he moved to Canada, arriving at Chalk River on 27 July, 1946, to continue his further career in counter-espionage.

But what is astonishing in Dan’s account is the claim that Mann came under suspicion only after Maclean’s desertion. Moreover, Dan does not allude to Mann’s being turned. Thus his classification of Mann’s being a double agent, because he worked ‘for both British Intelligence and the NKVD’ is also spurious. More accurately Mann was a spy (like Nunn May) who had made a personal allegiance to the Communist movement, had been recruited to SIS (like Kim Philby), and had then acted as an advisor to Donald Maclean (another mole), perhaps spying for Britain and the Soviet Union against the Americans (when Maclean was not aware of Mann’s true loyalties), and then had been turned by the CIA (or so they thought). No wonder Mann became a little unstable: he did not have the temperament of a TRICYCLE (Dusko Popov) or a GARBO (Juan Pujol Garcia) to handle the stress of such dissimulation and conflict of roles. In this mass of rumours, the exact chronology of Mann’s activities is probably never definable. Yet the most fascinating fact coming out of Dan’s summary is where he asserts that the Russians believed there was a British wartime Double Cross operation targeted at the Soviet Union. I shall return to this topic shortly.

Akin to the Mann/MALONE case is that of Cedric Belfrage. In many ways his career has similarities to that of Mann – a British citizen with communist convictions who ended up in the United States, and then came under suspicion from the US authorities. Only Belfrage’s identity was revealed more blatantly, by the Soviet courier Elisabeth Bentley, who had taken over the network of her lover and NKVD illegal agent in New York, Jacob Golos, when the latter died in November 1943. She told the FBI, in her 1945 confession, of Belfrage’s activities while working for British Security Coordination (BSC), the representative of Britain’s overall intelligence interests in the USA. Belfrage then left the USA at the end of the war, to take up a position with the Allied government of occupation in Germany, but returned to the USA in 1947, when the FBI started interrogating him. The fact that he lied to the FBI about his removal of documents from BSC to hand over to one V.J. Jerome was confirmed later in VENONA decrypts, where Belfrage’s activity as the agent with cryptonym UNC/9, during the period 1943-1945, is clearly shown. Belfrage was not charged by the FBI. As Nigel West writes: “Despite Bentley’s incriminating testimony, because the offenses he had committed against British interests had occurred in America, he was never charged.” Instead, he was subject to a deportation order after being called to give evidence at the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1953. He fought the order, but was eventually deported to England in August 1955.

Yet there is another link in the ‘double agent’ movement. John Simkin has written in depth on Belfrage in his Spartacus blog (http://spartacus-educational.com/spartacus-blogURL61.htm). As if coming to Belfrage’s defence while challenging the perspective of a BBC programme on Belfrage, Simkin makes the somewhat strange statement: “However, as he explained in his own interview with the FBI in April, 1947, he only passed information to the Soviet Union on behalf of BSC. Belfrage, like several intelligence officers, worked as a double agent in the war.” He attempts to make the case that, as Belfrage was working for the BSC when he was passing secrets to the Soviets, he was providing that information under orders, as if Belfrage’s testimony in this matter should be trusted. Yet, with all his communist affiliations and obvious illicit disclosures – Belfrage joined the Party in the US in 1937, only to drop it, as many others did, for cover – Belfrage should be characterized more as a Soviet spy who was recruited by a British intelligence organisation, in this case, BSC, just as Mann was, rather than as an idealistic anti-fascist who took a long time to understand the reality of communism. Simkin presents Belfrage as innocent – in other words, that he was a true patriot under cover feeding selected information to the Soviets. But that would make him a supremely competent intelligence officer – not a double agent.

Simkin may have become excited about what is a fascinating thread in this story – the need for America’s OSS (the wartime predecessor of the CIA) to understand what double-crossing was about. Simkin quotes a passage from the History of BSC that indicates that BSC was helping the Americans run double agents. “Many of the FBI’s troubles with double agents arose from their lack of understanding of the European mind and outlook, and their inability to place in charge of a double agent officers with a background likely to win his friendship and sympathy”, he quotes, adding that ‘the book also attempts to explain why the BSC double agents had to be given real intelligence to pass to another country’. “Finally, double agents cannot be used to deceive the enemy unless they are given, from time to time, true and useful intelligence material which they are permitted to transmit, for otherwise the enemy will realize that their information is of no value and will soon discard them.” I have a copy of this work in front of me. The chapter on ‘Double Agents’ very clearly states “A man or woman who is already permanently engaged in espionage on the enemy’s behalf must be persuaded or coerced to retain his employment but to transfer his allegiance to the other side.” If Belfrage had been in this category, he would have had to be a proven Soviet agent first, known to the authorities, and then coaxed to shift his allegiances. That is not the claim. Moreover, this book focuses exclusively on counter-espionage against the Nazis: Simkin’s inability to distinguish between the highly different circumstances of the Double Cross System and the management of suspected Soviet spies represents a colossal failure in analysis.

Were the Americans clumsily trying to imitate the practices of the XX System, but now against communist spies? In June 1943, the OSS had transferred the Yale academic Norman Holmes Pearson to London to learn from British counter-intelligence operations, and he became a member of the XX Committee in 1944, where he offered advice on some of the ethically more troublesome decisions that had to be made. (Other Americans involved in the BODYGUARD deception plans were allowed to attend XX meetings.) Holmes also recruited James Angleton as his assistant, an experience that had a long-lasting effect on the future CIA officer, who developed close relations with both Wilfrid Mann and Kim Philby. In his study of this period, Cloak and Gown, Robin Winks wrote: “James Murphy [counter-intelligence chief in OSS] was beginning to think that the next task would be to detect Soviet intelligence agents in the west, including those who worked under the cover of their own embassies. The NKVD had begun as a defensive intelligence organization with the goal of saving the revolution in Russia, but in its Cheka guise it had turned into an offensive operation. In this Murphy was joined by Norman Pearson, privy to the secrets of the British use of double agents against the Germans. At some point between August and December 1943 Murphy mentioned his concern to Angleton, who was fascinated by the notion of penetrating the enemy by exploiting its own agents.”

Yet it was one thing to turn a captured Nazi parachuting into the country, and quite another to attempt to convince an isolated but committed Soviet spy to change his allegiance fully to the other side! Most of the Abwehr agents landed in the United Kingdom were not Nazi enthusiasts, and quite quickly agreed to their new role. The most stubborn, TATE, took some time to be convinced, even though the alternative was a death sentence. And, indeed, many spies were led to the hangman’s noose or the firing-squad as the only alternative course of action. That threat did not loom over Blunt or Philby, Long or Cairncross. Guy Liddell would have preferred to shuffle off Nunn May or Fuchs, when they were proved to be spies, off to some provincial university, and Leo Long was encouraged to go on some kind of long stretch of Gardening Leave to repent, before being called back to intelligence duties. The punishment that the Cambridge Five faced, since MI5 did not want any messy trial to be undertaken, and knew that only a confession would procure a conviction, was the British version of the Comfy Chair so menacingly offered by Monty Python’s Spanish Inquisition. Did Pearson and Angleton really think they had a model for a strategy? After all, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg quietly went to the electric chair because they refused to implicate others, or change their opinions. The whole performance seems very ingenuous, but a fuller study of that aspect of OSS/CIA policy must remain for another day.

This intrinsically absurd phenomenon received official approbation after Margaret Thatcher unmasked Anthony Blunt in the House of Commons in 1979. Richard Davenport-Hines writes, in his Enemies Within (2018), that the official historian of intelligence, Sir Michael Howard, had a letter published in the Times, on November 21, which exculpated MI5’s cover-up. Decrying ‘witch-hunts’ (of course, but we must remember that while there was no such entity as ‘witches’, ‘unidentified Soviet spies’ was a very real category), Howard apparently gave a ‘temperate explanation’. The Times archive on-line does not go back that far, but Davenport-Hines next quotes from the letter: “When an enemy agent is discovered, the natural instinct of the security authorities is not to expose but to use him, and the greater his importance the stronger his instinct will be. Not only is he a mine of useful information, but if his employers are unaware that he has been ‘blown’, they will keep in contact with him. He can then be used as a double agent, feeding them information. For MI5, the value of keeping Professor Blunt as a card in their hands rather than discarding him by handing him over to justice must have been a major factor in the minds of those who made the decision.”

This is manifest nonsense. Blunt had managed to extricate himself from any commitments to his Soviet handlers soon after the war, and had lain idle, as a spy, for almost two decades before Michael Straight revealed Blunt’s activities, and MI5 successfully gained a confession from him in 1964. His importance then as a source was negligible. He was not a ‘mine of information’: on the contrary, he lied and dissembled about the whole story. If he had started producing ‘disinformation’ for Moscow, presumably under some threat of prosecution otherwise, Soviet intelligence would have immediately smelled a rat. Moreover, what would have stopped him telling his contacts what had happened, and thus alerting them to the deception? Was a minder going to accompany Blunt on his assignations to ensure that he passed on the information correctly? Howard’s ingenuous message should have received a vigorous riposte, but Davenport-Hines appears to have been taken in as well.

And what had the Soviets thought of all this wartime Double-Cross activity? After all, they were well aware of what was going on with Masterman’s committee, since Anthony Blunt kept them well-informed. Indeed, in 1943 Moscow Centre’s suspicions that British Intelligence might be double-crossing them were raised after Kim Philby made an operational mistake. According to West’s and Tsarev’s Crown Jewels, Moscow was shocked that Philby had decided to recruit as a source Peter Smollett (né Smolka) in the Ministry of Information, to be handled by Guy Burgess, without gaining permission first. ‘The Centre was appalled: who was Smollett?’ Notwithstanding that this, on the surface, showed a bewildering amount of ignorance about a person who was known to be a friend of the Communists, had visited the Soviet Union, and written a sympathetic book about it, Moscow was unconvinced by Burgess’s protestations, and documented that they now had set themselves the task of discovering what disinformation the British were planting on them. Lieutenant Elena Modrzchinskaya, who headed the English section of the NKVD, in July 1943 sent a damning report to her boss, Merkulov, claiming that the XX Committee was conducting a well-coordinated program against the Soviets as well as the Nazis. It was a typical display of obtuseness that only homo sovieticus could accomplish, in which Moscow displayed disgust at the untrustworthiness of its ally, while at the same time indulging in deep penetration of the latter’s political infrastructure in order to steal secrets.

It all blew over. At some stage the NKVD leaders decided that their spies had provided them with so much rich material that it was highly likely that it consisted of genuine confidential documents illicitly gained, and they could also not identify exactly which information was false. Burgess pointed out that it would be impossible for the British authorities to maintain so many double agents in places of influence. Just because the British had developed an efficient double-cross system against the Nazis, it did not automatically mean that they would deploy it against their allies. Russian paranoia had come into play. Thus by October 1943 the credibility of the network in Britain was restored. The London residency was told to take great care in handling the group, but the period of suspicion had come to a close by August 1944. Just before then, Blunt had given his bosses a comprehensive account of the XX System, which would have described its sole focus on the Abwehr, and that helped the NKVD to relax. Moreover, a delegation to Moscow, early in 1944, led by John Bevan, the head of the London Controlling Section (responsible for deception) had explained the whole BODYGUARD project to the Soviets, with the result that Lieutenant-General Kuznetsov of the General Staff was able to master its intricacies. Presumably Messrs. Murphy and Pearson were not aware of this goodwill visit.

Soviet Military Intelligence (the GRU, for whom Fuchs and Sonia worked) would have been unaware of all this turmoil. Yet it is hard to imagine that the GRU did not observe the whole matter of Sonia’s installation in England with a certain amount of amazement. How could the British authorities be so dumb as to facilitate her transfer? Even Sonia recorded in her memoir that she thought she had some kind of protector helping her in MI5. The evidence (such as the phony-looking extracts from the Soviet archives that suggest Sonia was merely loyally passing on information about German war plans) indicate that they went along with the game, using the surreptitious wireless set for the real business. Yet they must overall have concluded that the naivety of British Intelligence outweighed its natural wiliness, else they would not have been so indulgent with Alexander Foote. They had concerns that he might be a British plant back in Switzerland, and Foote must have performed heroically after his return to Moscow in 1945 to convince his interrogators that he was the genuine article.

The links between the activities of the XX Committee and attempts to turn Communist spies do have some substance, however. After the war, General Leslie Hollis *, then Chief of Staff to the Ministry of Defence, set up what was called the ‘Hollis Committee’, effectively taking over the role of the old W Board, which had directed high-level policy for the management of double agents, and to which the XX Committee had reported. To complement it, a little-known committee was set up to replace the wartime XX Committee, titled the Inter-Service Communications Intelligence Committee, under the chairmanship of ‘TAR’ Robertson (him who was so important a figure in the Double-Cross operation), to coordinate ongoing deception plans. The only adversary of substance, to whom such plans might be directed, was the Soviet Union. This committee did explore some ideas, such as using GARBO to infiltrate Soviet intelligence via Nazi officers recruited by the Soviets, although that particular exploit was abandoned. Moreover, there is evidence of loftier attempts to pass misinformation to the Russians. Thaddeus Holt, in his epic account of military deception in WWII, The Deceivers, writes about postwar efforts by the British and the Americans to mislead the Soviets as to the state of Western research and development, and ‘in particular to induce them to fritter their resources in directions known to the West to be unproductive’. Holt refers in passing to Operations THUMBTACK, CLASSROOM and BOYHOOD that were under discussion in 1948, and the little that Holt offers about them suggests that the first of these could well apply to nuclear secrets. (I am astonished that such an accomplished historian as Holt could, as late as 2007, solemnly describe the attempts to mislead the Soviets without acknowledging that the whole wartime deception plan had been revealed to them by the Cambridge spies.)

[* Were Roger Hollis, director-general of MI5, and General Leslie Hollis perhaps cousins? Roger was born in Wells in 1905, and his father, George Arthur, was at that time a curate. Leslie was born in Walcot, Bath, in 1897, and his father, Charles Joseph, was also a curate . . .]

But Fuchs seems a highly unlikely candidate to have been adopted at this time, and there is no evidence (that I have found) which would suggest that efforts had been undertaken to persuade Sonia to act as a double agent as the Cold War got under way. By then, her utility had diminished. Dansey, the premier candidate for the project of her manipulation, had died in 1947. The only clear incidents – with Mann and Belfrage – both occurred in the United States, where British Security Co-ordination, more closely linked to SIS than to MI5, rather clumsily succeeded in recruiting officers with communist sympathies to perform some sort of propaganda. Inspired by the heroics from Masterman and his team, BSC (and the OSS, FBI and CIA) then may have made even clumsier attempts to convince them to work against their Soviet bosses. Yet the conditions that made double-crossing of Nazi spies successful in wartime Britain – threats, confidence in the reoriented agent, tight and exclusive control, painstaking preparation, a high degree of security – simply did not obtain with the management of Soviet spies.

As for domestic lessons from the exercises during the war, and afterwards, we know that Britain was harsher with foreign-born spies (e.g. Fuchs, Blake) than it was with native-born Englishmen (and Scotsmen) who had betrayed their country from what the Security Service considered was a misguided sense of mission. (If obtuseness was the métier of homo sovieticus, that of homo britannicus was hypocrisy.) But MI5 (and MI6) did not linger long over the thought that they might be turned to good advantage. These characters did what they did out of political conviction, not from shabby mercenary motives, and the preference was, when their guilt was established, to hush the whole matter up and get the pests secluded somewhere, maybe abroad (like Cairncross), or preferably, perhaps, behind the Iron Curtain. If the intelligence services had tried to turn them as a bargain for non-prosecution, how would they ever have been convinced that an ideological volte-face had occurred, and that their victims had been defanged? The spies would still have had to communicate with their controllers in person, so it would have been impossible to supervise their duplicity. Guessing full well that they did not control the full network, what could MI5 and SIS possibly have hoped to achieve?

Pincher’s vague denials should thus be seen more as a smokescreen to deflect attention from the more plausible scenario that British intelligence tried to manipulate Sonia. She was never any kind of double agent, and any plans to assist her were conceived long before the XX Committee was created. If Dansey, as Colonel Z, did try to facilitate her passage into a role where the SIS might have had some measure of supervision over her, it was far more likely that it would have been simply a discreet attempt to decrypt her wireless transmissions. The official histories provide no insights. Dansey himself does not appear in the index of any of the five bulky volumes of the History of British Intelligence in World War II, which cannot be attributed solely to the fact of his unpopularity. It is true that the authors were reticent in identifying individuals, but then there is no reference to the Z Organisation, either. The lack of coverage means nothing. It could indicate that there was a massive cover-up over an intelligence disaster: it could indicate that there truly was some manipulation, but that the historians were ‘encouraged’ not to write about it. But it surely cannot mean that nothing of significance at all happened around the indulgent treatment of Sonia. And the fact is that SIS and MI5 were outwitted. The Soviets swindled the British.

[I encourage readers who may have insights into Pincher’s claims to contact me at antonypercy@aol.com]

This month’s Commonplace entries can be found here.