Dead Doubles, by Trevor Barnes (2020)

Atomic Spy, by Nancy Thorndike Greenspan (2020)

An Impeccable Spy, by Owen Matthews (2019)

Master of Deception: The Wartime Adventures of Peter Fleming, by Alan Ogden (2019)

Secret: The Making of Australia’s Security State, by Brian Toohey (2019) [guest review by Denis Lenihan]

I return this month to reviewing some recently published books on espionage and intelligence, and thank Denis Lenihan, coldspur’s Commissioner for Antipodean Affairs, for making a lively and insightful contribution. Ben Macintyre’s Agent Sonya did not arrive in time to meet the Editor’s deadline, but, in any case, I have been engaged to write a review of it for an external publication, so I shall have to hold off for a while. (My review was submitted on October 19, has been accepted, and will be published soon.) I considered two other books that, from their titles, might have been considered worthy of consideration for a review, Secret History: Writing the Rise of Britain’s Intelligence Services, by Simon Ball (2020), and Radio War: The Secret Espionage War of the Radio Security Service 1938-1946 by David Abrutat (2019). Then, a few weeks ago, I came across the following comment from one of my least favourite economists, Joseph Stiglitz, in a book review in The New York Times: “As a matter of policy, I typically decline to review books that deserve to be panned. You only make enemies.”

On reflection, this seemed a tendentious and somewhat irresponsible line to take. Assuming that experts like Stiglitz are commissioned to write reviews of books, how will they know whether such volumes deserve to be panned or not until they have read them – unless they make a prejudgment based on their understanding of the author’s politics or opinions, and in ignorance of how well the book may have been written? It would be a bit late to accept the commission, read the book, decide it was dreadful, and back out of the contract. But maybe that is why book reviews are overall positive: the publisher of the review wants to encourage readers, not warn them off undeniable clunkers.

Well, I am not worried about making enemies. Heaven knows, I must have upset enough prominent historians and journalists through my writings on coldspur, and the ones who were too elevated to engage with me were never going to change anyway, so that is not a worry that concerns me. And, since I am not in this for the money, I can choose to review what I want. But the two books named above, which would seem, potentially, to play a valuable role in the history of intelligence activities were in their different ways so poor in my opinion that I decided not to waste any further time on them. Incidentally, as I revealed a few months ago, Abrutat has recently been confirmed as the new GCHQ departmental historian.

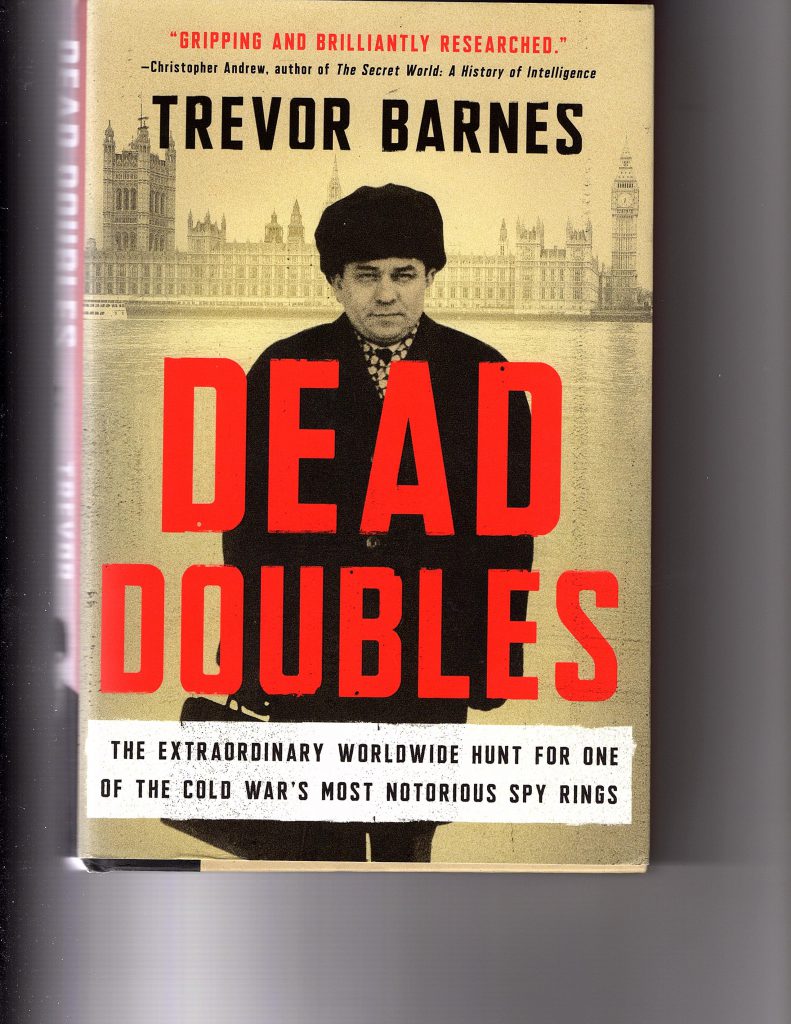

Dead Doubles, by Trevor Barnes

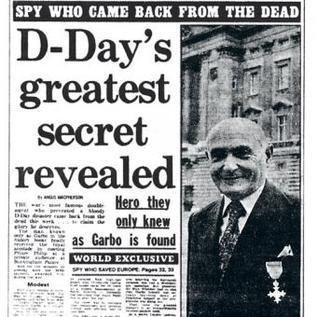

The 1960-61 case of the Portland Spy Ring is, I assume, fairly well known by enthusiasts of espionage lore. A very public trial took place, and a government inquiry followed. Paul Tietjen, a Daily Mail reporter, wrote a very competent account, Soviet Spy Ring, in 1961, and a movie based on the case, Ring of Spies, appeared in 1964. References are sprinkled round various books, and the several million who read Peter Wright’s Spycatcher will have learned of some of the electronic wizardry that went on in preparation for the arrests. Late in 2019, the National Archives released a batch of files relating to the five subjects in the case, and Trevor Barnes has worked fast and diligently to produce a comprehensive account of what happened, in his recently released Dead Doubles. The title is a little unfortunate: it refers to the Soviet practice of stealing identities of children who died soon after birth, such as Konon Molody was permitted to do with Gordon Lonsdale. Yet it is not the essence of the story, and does not perform justice to the other actors in it.

In 1959, the CIA received a warning from a Polish intelligence officer who was close to defecting, Michael Goleniewski, that secrets were leaking from a top-secret naval research establishment in Portland, Dorset. When MI5 was informed, suspicion soon fell upon Harry Houghton, who maintained a relationship with Ethel Gee, an employee who had access to documents concerning development of underwater weapons technology. Houghton was trailed to London, where he had assignations with an enigmatic character called Gordon Lonsdale. By inspecting Lonsdale’s possessions, and eavesdropping on his apartment, MI5 and GCHQ were able to ascertain that Lonsdale listened to coded messages from Moscow on his wireless, and also owned one-time pads (OTPs) that were necessary for decryption – and probable encryption – of messages. He was in turn followed to a bungalow in Ruislip, where two ostensible New Zealanders, Peter and Helen Kroger, the latter a second-hand book-dealer, were living. As the KGB moved closer on Goleniewski, MI5 had to act quickly, and arrested all five miscreants, soon discovering a hidden wireless apparatus in the Ruislip basement. All five were jailed: Gordon Lonsdale turned out to be one Konon Molody, while the Krogers’ real identities were Morris and Lona Cohen, known to the FBI as dangerous Soviet agents, but lost track of. Molody and the Cohens were soon released in spy swaps.

Barnes’s story does not start well. He supplies a map – an excellent device, since maps give substance to the dimension of space in the same way that a proper chronology provides a reliable framework for time. In his first sentence, however, he refers to ‘Fitzrovia’ in order to provide a location for ‘Great Portland Street’. But ‘Fitzrovia’ is a literary construct, not an administrative district, and his map betrays the confusion, as Fitzrovia is clumsily packed close to Marylebone, and, to make matters worse, mis-spelled as ‘FIZROVIA’. Moreover, on page 2, Barnes describes a journey from Great Portland Street to the ‘secret MI5 laboratory two miles to the west’. But this establishment does not appear on the map, and it was located two miles to the east, not to the west. Thereafter, some other important places do not appear on the map, such as the CIA’s London Office at 71 Grosvenor Street, referred to on page 15.

After this, Barnes quickly gets into his stride. He has performed all the necessary research to give the story the political and intelligence context it needs, exploiting American and Russian sources, the obvious archives at Kew, as well as the unpublished diaries of Charles Elwell, the MI5 officer on the case, and the papers of Morris Cohen at the Imperial War Museum. He understands the technological issues well, and re-presents them in a highly accessible and comprehensible way. He very rarely gives the impression of bluffing his way through a thorny controversy, although he may be a bit too trusting of that rogue, Peter Wright. (Barnes refers to Wright’s ‘Radio Operations Committee’, when the Spycatcher author wrote of a ‘Radiations Operations Committee’. I can find no trace of such an entity.) The story moves at a smooth pace, although the chronology darts around a little too much for this highly-serial reader, with the result that relevant details of some events are scattered around the text. An irritating structure of Parts and Chapters, a very sparsely populated Index, and – the bane of all inquisitive reference-followers – Endnotes that refer to Parts, but do not describe the relevant chapter or page ranges at the top of their own pages, made close analysis more difficult than it could have been. A master index of National Archives files used would have been useful, rather than having them scattered around the Endnotes. Overall, however, Dead Doubles is unmistakably an indispensable and highly valuable contribution to espionage literature.

And yet. (Coldspur regulars will know there is always an ‘and yet’.) While every aspect of the investigation, arrest and prosecution is fleshed out in gripping detail, I was looking for a deeper analysis of some of the more troubling dimensions of the case. For example, it does not help me to know that, a week before Houghton and Gee were trailed to London on the day of their arrest, the Beatles had given ‘a sensational performance in the ballroom of Litherland Hall’, or that The Avengers serial began on television the same day (January 7, 1961). What I would have liked to read, for example, was a more insightful analysis of why Houghton’s drunkenness and violent behaviour while working for the British Embassy in Warsaw resulted in his being sent home but then transferred to Portland’s Port Auxiliary Unit in 1951, rather than being fired.

It reminded me of the scandalous behaviour of Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, who benefitted from a series of indulgent job changes, instead of being despatched to earn their living elsewhere. What is it about the British Civil Service that causes it to think that a recruit has a job (and pension) for life? Barnes reveals some fresh information on the way that The Admiralty and MI5 had ignored a damaging report on Houghton provided in 1956 by his abused wife, which was buried, or diminished, and he concentrates on this new archival evidence, but at a cost of overlooking a more dramatic scoop.

For the charges went back farther than that. In his book, Tietjen had recorded, back in 1961, that the British Embassy in Warsaw had declared, when they sent Houghton home in October 1952, that he was ‘a security risk’. If that were true, the whole exposure could have been quashed at birth. (We must remember that Tietjen was not aware of the Goleniewski revelations, or Mrs Johnson’s testimony, when he wrote his book. Moreover, as is clear from his notations, his book was published before the Romer Report on security at Portland came out in June 1961.) It is not clear where Tietjen gained his information about the ‘security risk’ report, but it was obviously official, as Tietjen annotates his awareness of it with a Footnote: “Whether Houghton was ever reported to the Admiralty by Captain Austen as a ‘security risk’ is a matter still under investigation by a specially convened Government committee.”

Yet Barnes does not mention this report in his book: he records an interview (undated, but probably in late May 1960) that MI5 officer George Leggett and MI6’s Harold Shergold had with Captain Nigel Austen, for whom Houghton had worked in Poland, but Barnes does not cite Austen as referring to his own ‘security risk’ report on Houghton. On the contrary, Austen used the opportunity to minimise Houghton’s failings, and bolster his own image: Yes, Houghton had been drinking heavily, but Austen was quick to get rid of him; yes, Houghton did make money on the black market, but then no more than any other Embassy official; Houghton’s wife was as much to blame (‘a colourless, drab individual who disliked being in Warsaw and no doubt was partly responsible for Houghton’s conduct’) for her husband’s behaviour. And when Leggett asked Austen whether he thought Houghton was a spy, Austen suggested that Houghton’s actions never indicated any betrayal of secrets to the Poles. (p 19)

It appears as if Austen had been nobbled by this stage, and instructed that, if he wanted to keep his pension (he had retired in January 1960), he should downplay Houghton’s behaviour, and never mention the ‘security risk’ report. Yet the Admiralty had already started digging its hole. As Barnes writes: “The Admiralty had forwarded this report [UDE to Admiralty in 1956, concerning claims made by his ex-wife, now Mrs. Johnson] to MI5 with a covering note, which disclosed that Houghton had been sent home from Poland because he had become very drunk on one occasion, and ‘it was thought he might break out again and involve himself in trouble with the Poles.” (p 10)

‘On one occasion’? As Barnes adds: “According to Mrs Johnson, while in Warsaw Houghton was ‘frequently the worse for drink in public, and apt to talk loudly and indiscreetly about his work. On . . . occasions, at official parties at the embassy, Captain Austen was obliged to send Houghton home by car, he having become incapable of standing up.’” Moreover, when the MI5 officer James Craggs, ‘a sociable bachelor in his late thirties’, went into the Admiralty on May 5, 1960 to inspect the Houghton files, he apparently learned a lot. “A picture of Houghton’s life began to emerge. In December 1951 Austen had cautioned the navy clerk for heavy drinking, and the following May Austen wrote again to say that Houghton was still drinking excessively. Houghton was sent home later that year, and on his return to the UK he was posted to the UDE at Portland.” (p 12) The Admiralty was trying to pull the wool over the eyes of MI5. Certainly not just ‘one occasion’.

So where did Tietjen get his information? Did officer Craggs find out about the ‘security risk’ in his session at the Admiralty, and leak it to Tietjen? The claims that the Admiralty made were evidently untrue, according to Mrs Johnson’s testimony, but also from the Admiralty files that they must have forgotten to weed. But Craggs surely knew. And the whole problem of suitable behaviour at foreign embassies was brushed under the rug when Lord Carrington addressed the House of Commons on the Romer Report. On June 13 he spoke as follows, as Hansard reports: “1. No criticism can be made of Houghton’s appointment in 1951 as Clerk to the Naval Attaché in Warsaw. Nor can any criticism be made of want of action by the Naval Attaché or the Admiralty in the events leading up to his recall to London, before the expiration of his appointment, on account of his drinking habits. 2. Given the security criteria of the time no legitimate criticism can be made of Houghton’s subsequent appointment in 1952 to a post in the Underwater Detection Establishment at Portland which did not in itself involve access to secret material. It is regrettable however that the authorities at Portland were not informed about the reason for Houghton’s recall from Warsaw.”

So that’s all right, then. Getting continually sloshed is a hazard of working in dull Embassies behind the Iron Curtain. Black market dealings are not mentioned. Nothing is said about the lost ‘security risk’ report. Yet the Admiralty’s own evidence contradicts this smooth elision of what happened. Did Tietjen speak up after the Romer Report was issued, possibly incriminating Craggs, and was he then sworn to silence? Moreover, a further disturbing complication has to be addressed. In an endnote, Barnes informs us that ‘Craggs’ was not the MI5 officer’s real name (it had been redacted in the archives), and Barnes, though he discovered the real name, had to conceal it, at the request of MI5, because of ‘potential distress to his family’. (Note 8, p 290)

Apart from questioning why Barnes was negotiating with MI5 during this research, I have to ask: what could Craggs possibly have done that would require his name to be concealed after sixty years have passed! This must be an epic scandal if today’s cadre of MI5 officers have to be warned about it. Was Craggs perhaps punished severely for leaking information from the Admiralty files to a Daily Mail journalist? Craggs’s inspection of Admiralty records, Tietjen’s knowledge of Austen’s report, Austen’s clumsy interview, the Admiralty’s claim that the report was lost, Cragg’s humiliation and excision from the record: they all point to a dishonourable leakage of information. I believe that Barnes could, and should, have paid more attention to this mystery. By highlighting the fact of his own diligent sleuthing, namely that he had discovered who the anonymous officer was, but then showing no interest in what the scandal was about, Barnes has simply drawn attention to the shenanigans. (I have communicated my thoughts to him, but he has not replied to my latest analysis.)

A related story worthy of deeper investigation is the lamentable security at the Underwater Defence Establishment (UDE) at Portland. On May 11, 1961, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan commissioned Lord Radcliffe to investigate security across all the public services, and the Romer Committee (which was inquiring into Houghton and Gee) delivered its own findings to the Cabinet Secretary on May 30. The Romer report described the lack of security-consciousness at UDE, and criticised the head of the establishment, Captain Pollock, but the outcome was feeble. As Barnes writes: “Although the Portland security officer was dismissed from his post, as a temporary civil servant his pension was not cut; and the head of UDE in 1956, Captain Pollock, who retired in 1958, submitted a robust defence. Almost a year after the Portland trial, the Admiralty decided there were simply no grounds for disciplinary action against him.” What incentive can there be for doing a job properly if the incumbent knows that the institution will always take care of its own? The analysis of the Radcliffe report warrants only two short sentences in Dead Doubles: no doubt Barnes felt it was outside his remit, but this is a subject crying out for greater analysis.

This account presents an absorbing case-study in historiography. Barnes has clearly benefitted from the support and encouragement of his mentor, Christopher Andrew (‘the godfather to this book’), and cites Andrew’s coverage of the case in his 2009 history of MI5, Defending the Realm (pp 484-488). Andrew had offered one line about the failure of MI5 to follow up on the clues provided by Houghton’s ex-wife. But Andrew was characteristically oblique in his sources, listing solely his traditional ‘Security Service Archives’, some conversations with MI5 officers, and some selective – and thus, highly questionable – references to Peter Wright’s Spycatcher. (which Andrew shamelessly lists in his Bibliography). The only specific source was an obscure article in Police Journal by Charles Elwell, one of Barnes’s key witnesses, written under the pseudonym ‘Elton’. See: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0032258X7104400203 . (I do not believe Barnes cites this, but it may have been inserted into the recently released files.)

Yet a useful file was available at the National Archives at that time. In his 2012 work, The Art of Betrayal, Gordon Corera also wrote about the Portland Spy Ring at length, and dedicated a paragraph (p 234) to the fact that Houghton’s ex-wife believed that he was in touch with Communist agents. Corera quotes the response from MI5 that her accusations were ‘nothing more than the outpourings of a jealous and disgruntled wife’, citing the file ADM 1/30088, which was the text of the Romer Inquiry. One can ascertain from the Kew Catalogue that this file is accompanied by ADM 116/6295-6297: they appear to have been stored for access in the 1960s, and updated with various items since. Yet these files (which Andrew could have named) are not referred to by Barnes. Instead, he uses the more comprehensive version of the Romer Inquiry issued in 2017, at CAB 301/248. I have not been able to compare the two, but it is important to recognize that the facts about MI5’s oversights in not checking out Houghton have been known for almost sixty years.

Furthermore, Chapman Pincher claimed, at the same time, that Macmillan ‘declined to publish Romer’s findings’, and that they were not published until 2007, when the Cabinet Office yielded to a Freedom of Information request from Dr Michael Goodman. That presumably relates, however, to Cabinet Office files, not Admiralty records. (Infuriatingly, the Catalogue entry for ADM 1/30088 does not give a release date.) Naturally, Pincher places all the blame on Roger Hollis, and that his ‘minimalist policy’ had allowed Houghton to continue his espionage untroubled. That was more an indictment of incompetence rather than of treachery. If Hollis had really wanted the Portland Spy Ring to remain a secret, he would surely have arranged things so that Lonsdale left town at the first available opportunity.

I believe Barnes might have plunged in more boldly on some other intelligence aspects of the case, and I highlight six here:

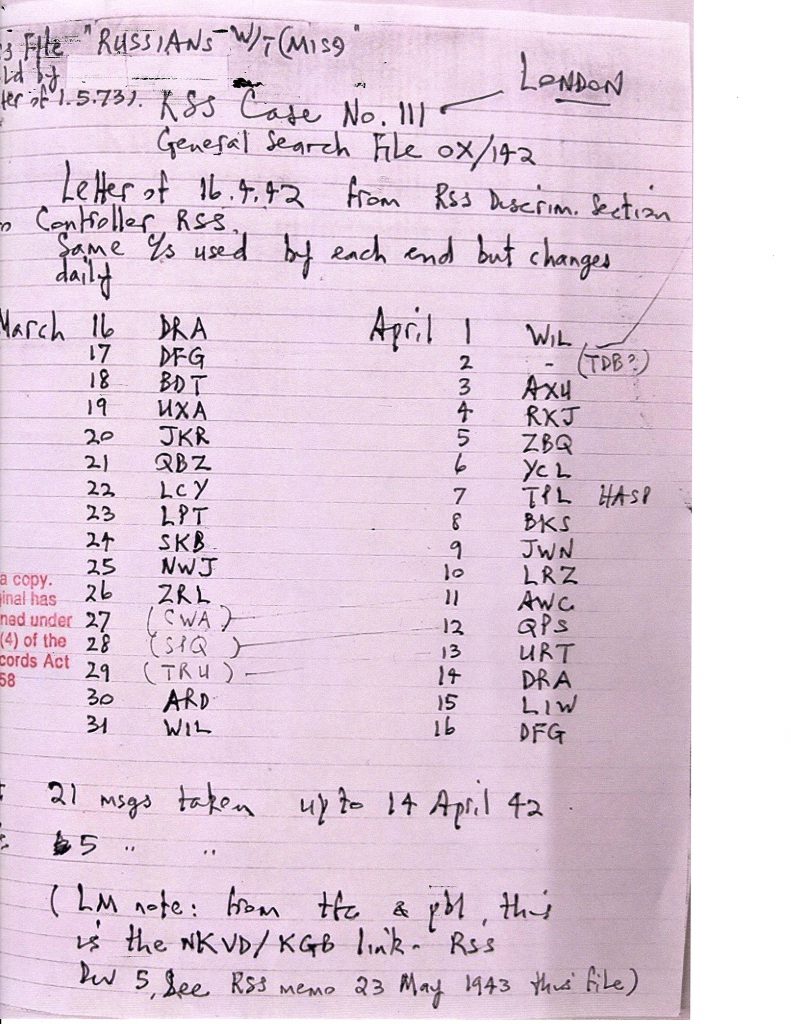

- Lonsdale’s One-Time Pads: One of the key discoveries made when Lonsdale’s safe-deposit box was opened by MI5 was a set of three one-time pads (OTPs), vital for the decryption of incoming and outgoing messages. It seems that Helen Kroger keyed in all of Lonsdale’s messages, both the confidential ones (encyphered and typed on his typewriter), and the family ones (in manuscript) that were found in HK’s bag. One of the pads evidently referred to encyphered messages received on Lonsdale’s general-purpose wireless set, and MI5 & GCHQ were able to detect the frequency of personalized transmissions by inspecting the use of the pad. Thus the second of the three OTPs found in Lonsdale’s box must have been used for the encypherment of transmissions. Why did GCHQ/MI5 not notice or comment on how pages in this OTP had been used up, as they did with his receiver OTP? And what was the third OTP used for? Barnes does not comment.

- Lonsdale in Ruislip: The reason that the Krogers were able to be arrested was because Lonsdale had unwittingly led his surveillance officers to their bungalow. But why did Lonsdale have to visit them? It sounds to me like very dangerous tradecraft. He should surely have met Helen or Peter at a neutral location to pass over his documents. After all, when Lonsdale was extradited to Berlin in the swap with Greville Wynne, he told MI5 officers, as they went through Ruislip, that they had chosen that location because of the US air traffic that would mask their transmissions, so why would the three of them endangered that ruse by the possibility of Lonsdale’s leading surveillance officers to the secret place?

- Flash Mode: Barnes comments that the Krogers had been issued with a ‘novel’ wireless apparatus (the R-350-M) that operated in ‘flash’ mode, namely allowing keyed messages to be stored on tape, and then sent at ultra-high speeds to Moscow to avoid interception and direction-finding. If the Krogers had been using flash mode from the start, why would they have been concerned about direction-finding? The operation would have been over before GCHQ could even contact a van, if they had been able to pick up the signal (which Arthur Bonsall of GCHQ said was impossible, anyway.) Barnes refers to their previous equipment as the ‘Astra’ box, but does not describe it fully, or explain whether it was also capable of ’flash’ operation. His reference to ‘novel’ suggests that the previous box did not have flash capabilities. This characteristic is important in the story of interception.

- Interception and Direction-Finding: Astonishingly, the status of GCHQ’s ability to intercept and locate illicit transmissions in 1960 appears to be markedly weaker than it was in World War II, as is shown by the testimony from Bonsall that Barnes cites. Coldspur readers will recall that Peter Wright claimed that GCHQ said that it would have been impossible for Agent Sonia to have operated undetected in the years 1941 to 1945. Yet by 1959 GCHQ admits defeat in its ability to pick up clandestine traffic targeted towards Moscow, and needs MI5 to tip it off about the places to watch! There is an untold story here about the reality and deterioration of the capabilities of the RSS (after the war The Diplomatic Wireless Service). (I have my own theories on this, which I shall explain in my culminating chapter on Sonia and Wireless Detection.)

- Soviet Stable of Spies: Barnes makes some highly provocative claims about the presence of unnamed Soviet spies and illegals, assertions that are dropped into the text – almost carelessly. He writes that, at the time of the arrests, GCHQ was aware of ‘radio signals transmitted by KGB illegals in the UK’. So how did they know of the existence of such? Elsewhere he refers to the ‘stable of spies’ which had issued burst signals similar to those transmitted by the Krogers? Who were these people? He also states that MI5 had no practical experience of KGB illegals. Apart from the fact that they were aware of Soviet illegals in the 1930s (Mally & co.), if GCHQ knew of them, MI5 must surely have known them, too. This is a puzzle that I do not understand, and I am anxious to know Barnes’s sources.

- Lonsdale’s Death: Lastly, the demise of Lonsdale. I have a particular interest in the dozens of cases of unexplained or early deaths of those who incurred the wrath of the KGB, and whom Sudoplatov’s ‘Special Tasks’ group may have pursued and annihilated. Barnes recounts Lonsdale’s death from a heart-attack in Moscow while mushroom-picking (a notoriously dangerous Russian pastime, by the way). Was this a straightforward medical incident? After all (as Barnes relates) he received death warnings, feared being shot on his return, was openly critical of Soviet society, and was given multiple injections shortly before he died. Is it not possible that his appalling tradecraft incurred the ire of KGB high-ups?

The good news is that I have presented this set of questions to Mr. Barnes himself, and he has accepted them as appropriate and thought-provoking. He has promised to inspect them more closely when he is not so busy. He must be much in demand with the attention over his book, as he well deserves to be. I look forward avidly to Barnes’s eventual response. His discomfort with Peter Wright comes through in his narrative, where he is sensibly cautious in accepting some of Wright’s claims about GCHQ’s interceptions of related messages. That is the perennial challenge for Barnes, and Andrew, and anyone else who chooses to cite Wright’s recollections from Spycatcher. Why do you accept some assertions, but discount others, and what does the inclusion of the book in your Bibliography mean?

I also wish Barnes had pushed his comprehensive reportage a bit further into analysis, and not withdrawn because of pressure from MI5, but I still encourage you to read Dead Doubles. And please send me your thoughts on the issues I have listed. In order to ensure the confidentiality of our correspondence, I do remind you all not to re-use your one-time pads (as some of you have been doing), and to ensure that your indicator groups appear in your message after my name, not before it. And, if you run out of one-time pads, we use Wisden’s Almanac, 2016 edition (not 2015!) as our reference book. Got that? It shouldn’t be that difficult, should it?

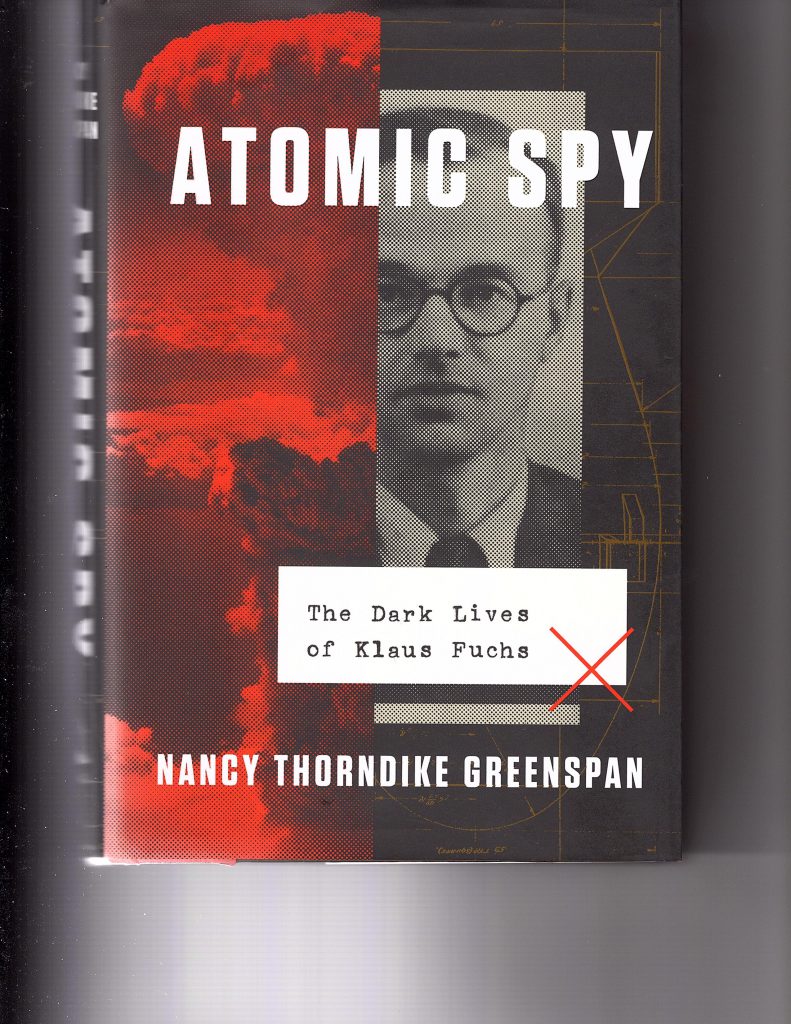

Atomic Spy, by Nancy Thorndike Greenspan (2020)

Does the world need another biography of Klaus Fuchs? I have on my shelf those by Norman Ross, Robert Chadwell Williams, and Eric Rossiter, as well as last year’s epic composition by Frank Close. Evidently, the publishers at Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House, thought so, even though Close’s Trinity was published by Allen Lane, also an imprint of Penguin Random House. Presumably Ms. Greenspan knew about Frank Close’s concurrent work, and she indeed lists it in her biography. So one might expect a novel interpretation of the life of the atomic spy with divergent loyalties. The sub-title is ‘The Dark Lives of Klaus Fuchs’. Dark – as in ‘previously undisclosed’? Or as in ‘sinister’?

And what are Ms. Greenspan’s qualifications for writing about Fuchs, and what is her approach? It is not clear. She is recorded as having collaborated with her late husband, Stanley, on works of child psychiatry, and she published a book on the Life and Science of Max Born a decade ago, but I can find no record of her academic credentials. Moreover, she appeared to require large doses of help in compiling her work – not just the predictable interviews with a large range of offspring of friends and associates of Fuchs, but availing herself of an impressive list of persons who ‘agreed to interviews, tours, meetings, teas, and lunches and in every way were supportive’, from Charles and Nicola Perrin to the inevitable Nigel West and the elusive Alexander Vassiliev. How very unlike the solitary drudgery in which coldspur finds himself performing his researches! I should add, however, that while I shall probably not breakfast in Aberystwyth again, I did have a very pleasant lunch with Nigel West a few years ago, but am still awaiting Sir Christopher Andrew’s invitation to tea.

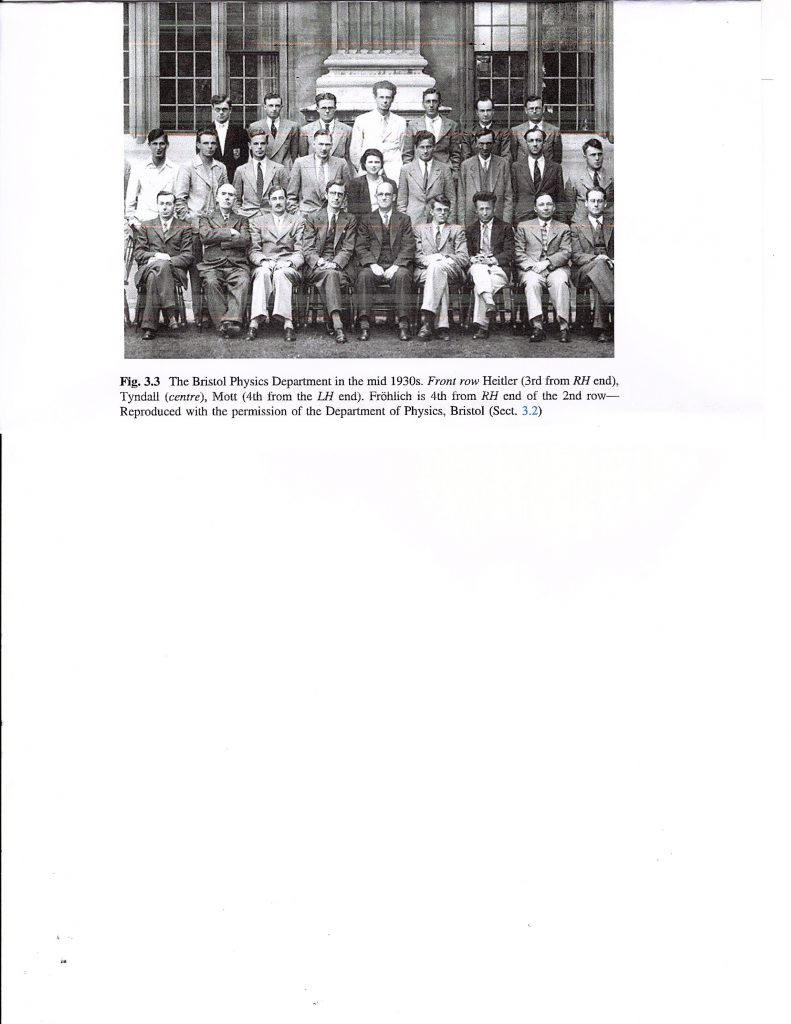

Ms. Greenspan lists a highly impressive set of international archival references, which point to a broad and deep study of the available material. Moreover, one noticeable feature of Greenspan’s detailed endnotes is the fact that she appears to have had access to some of the Fuchs files that have been withheld at Kew, such as the AB/1 series, which has been closed for access for most human beings. Her ability to inspect Rudolf Peierls’s correspondence, for instance, represents a highly controversial feather in her cap, which demands a more open explanation. Why would the relevant ministries allow an American writer to inspect such files, and why does she not explain her tactics in achieving such a coup? I was immediately intrigued to know whether her access to papers that the authorities have, in their wisdom, deemed too confidential to be exploited by the common historian, enabled her to construct some piercing breakthroughs in analysing Fuchs’s relationship with his political masters in the United Kingdom. When researching this matter with an on-line colleague, however, I was informed that she (and Frank Close) both probably benefitted from the availability of papers before the decision to withdraw them – primarily the AB 1/572-577 series of Rudolf Peierls’s correspondence. From a study of her endnotes, and those of Close (which are, incidentally, a treasure trove in their own right, which teaches more on each subsequent inspection), it would appear that Greenspan delved more widely in these particular arcana than did Close. What prompted the sudden secrecy by units of the British government over atomic research in the 1940s remains an enigma.

Greenspan’s methodical coverage of the sources is, however, not reflected in the originality of her text. Atomic Spy is overall disappointing, and does not add much to our understanding of Fuchs’s motivations and behaviour. Nevertheless, in four aspects, I thought Greenspan provided some fresh value worth noting. She dedicates four excellent chapters on Fuchs’s experiences in Kiel and Berlin in 1932 and 1933 – a period compressed to just two pages in Close’s account – describing vividly the terrors that the Nazis imposed on opposition groups, but especially the German Communist Party. At the age of twenty-one, Klaus had taken over from his brother, Gerhard, the leadership of the Free Socialist Student Group (a cover name) in Kiel. Gerhard had escaped to Berlin, but Klaus was now a hunted man, under sentence of death. On February 28, 1933, Klaus himself escaped from Kiel, when he was number one on the list to be arrested, and moved to Berlin. Very recklessly, when Gerhard had had to go into hiding, Klaus continued to try to recruit students to the communist cause, when it was clearly a hopeless venture. The Nazis were leaving mangled bodies of communists on the streets. In mid-July, Klaus boarded a train for Aachen, Paris, and eventually Bristol.

Greenspan also sheds fresh light on the horrors of internment that Fuchs and others experienced on the S. S. Ettrick on the voyage to Canada in July 1940, the brutal way that the prisoners were treated by their guards, and the vile conditions that existed on the ship, with thirteen hundred refugees crowded into a hold with the portholes shut in conditions of unbelievable squalor. According to Fuchs, the communists did most of the work in cleaning up the vomit and excrement that swamped the place. While they were at sea, they heard that U-boats had torpedoed the sister ship, the Arandora Star. Dry land in Canada may have been a relief after ten days on the Atlantic Ocean, but conditions in the camp were also grim to start with, a freezing winter making life desperately uncomfortable. The prisoners successfully petitioned for improved conditions, and by December Fuchs was a member of one of the first lists of internees to be sent back to Britain. One can forgive him for harbouring a grudge against the treatment they received, and the frequent accusations and insults that they heard from guards and civilians that he and his fellow internees were ‘Nazis’ simply because they were Germans.

The third area where I believe that Greenspan is more perceptive than other biographers is her coverage of the conversations between Henry Arnold, the security officer at Harwell, and Klaus, in late 1949. A possible defence that Fuchs could have used at his trial was that he had been ‘induced’ by Arnold, and John Cockcroft, the director of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment, into confessing his espionage a spart of a deal. The concern that Fuchs’s confession might not have been truly voluntary brought MI5 to questioning whether the prosecution might fail on that account. Moreover, he had not been cautioned appropriately. Thus the written confession that he provided became extremely important. MI5’s attorney, B. A. Hill, was comfortable, however, with the sequence of events, and moved to advise the prosecuting lawyer, Christmas Humphreys. Yet Fuchs’s decision to say nothing at his initial hearing (on February 10, 1950), and the reluctance of Derek Curtis-Bennett, who represented Fuchs at the trial that took place on March 1, to challenge the Attorney-General, Sir Hartley Shawcross, on what Greenspan describes as ‘the now open secret of inducement’ is puzzling and disturbing. Curtis-Bennett, perhaps under instructions, made a very disjointed plea in Fuchs’s defence, but Fuchs had little to say when invited by Lord Goddard to speak.

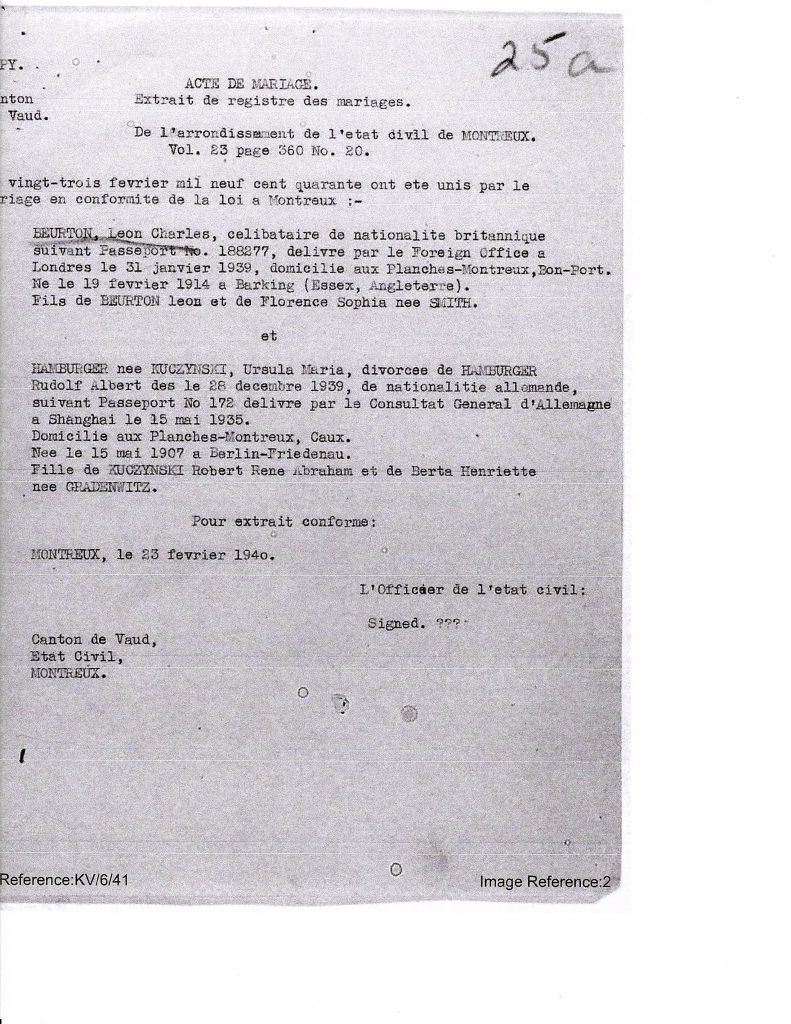

Lastly, Greenspan adds some useful information about Fuchs from his time in East Germany, where he did not get the heroes’ welcome that he expected, maybe naively. The Soviets wanted no suggestion that they had acquired the atomic bomb other than from their own research and imagination. The author writes: “No celebrations and accolades welcomed him. The Russians wanted no reference to his passing them information. According to them, they had discovered the atomic secrets themselves. Russia’s denial of any connection to him made his past taboo. Even his nephew Klaus had felt the long arm of the KGB. When he applied for admission to Leipzig University in 1956, he included that his uncle had spied for Russia. University officials accused him of lying. Russia didn’t have spies. They forced him to delete the information.” But what is surprising is that Greenspan does not include the passage from the Vassilievsky Notebooks, where Sonia (Ursula Beurton, née Kuczynski) was quick to tell the authorities how ashamed she was of Fuchs’s conduct in confessing, and how, if she had been given the chance to give him a firm talking-to, the whole messy business of arrest and trial could have been avoided.

Yet the reader has to trudge through some familiar territory, well-ploughed by Close, to glean these insights. And Greenspan leaves behind a number of errors in her wake, mainly because she appears to have spent little time in the British Isles. She characterizes MI6 as ‘the military division of foreign intelligence’, represents the British intelligence establishment as ‘dominated by toffs’ from Eton or Harrow, which was certainly not the case, and introduces Edinburgh (where Fuchs returned to work under Max Born) in the following terms: “Januarys in Edinburgh are blustery and gray. The cold, raw air from the English Channel blankets the city of stone and seeps into the bones”, an observation bound to raise the hackles of even the most indulgent Caledonian. She hazards a guess that Sonia might have been in contact with Fuchs in 1949 because of ‘the proximity of Harwell to Great Rollright’, when Sonia had in fact lived closer to Harwell beforehand, and there is no evidence that she and Fuchs got together again in the UK after 1943. I would have thought that one of her many advisory readers would have shown a greater familiarity with British geography and institutions. Like many chroniclers, Greenspan is also a bit too trusting of ‘Sonya’s Report’.

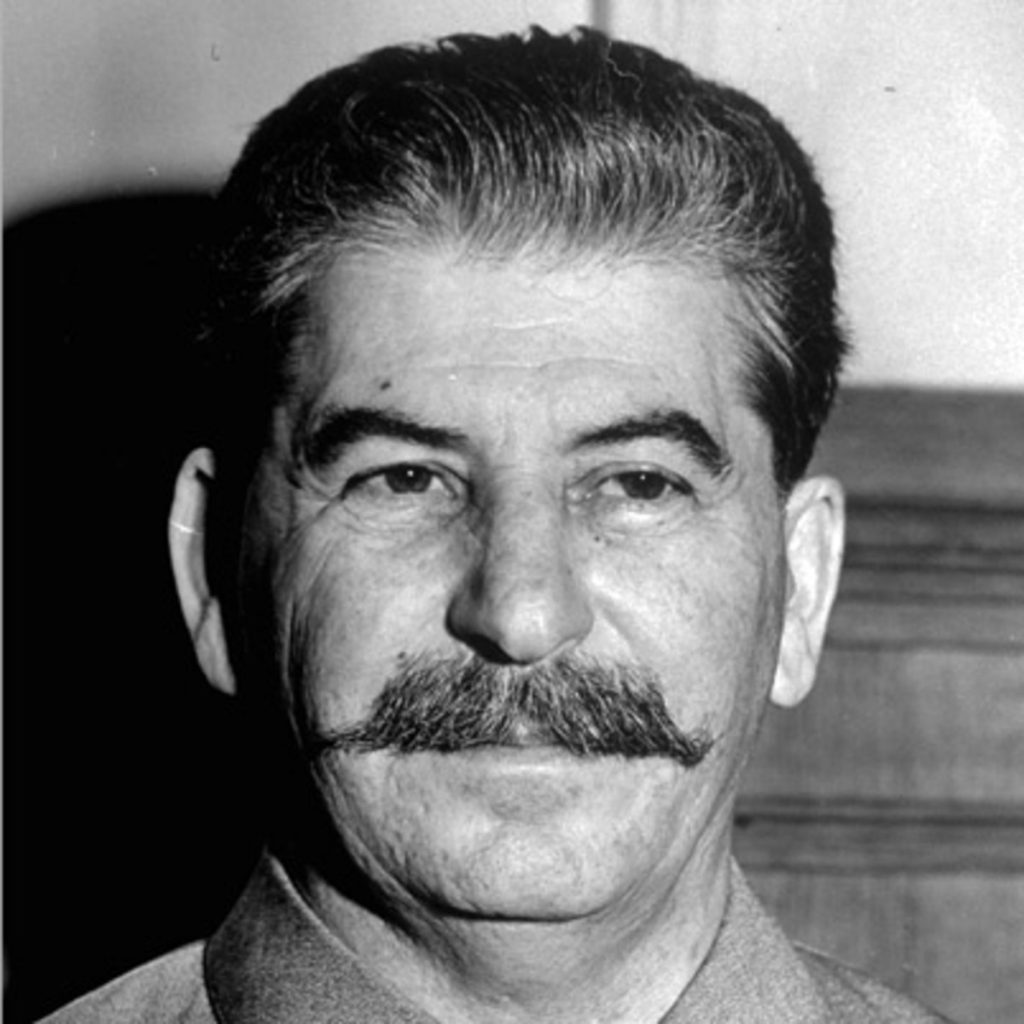

The final judgments that emanate from all this teamwork are drearily mundane and misguided. She phrases her final verdict thus: “Fuchs’s actions left most people confused, but what they didn’t see was that his life, circumscribed from within, was consistent and constant to his unwavering set of ideals, he sought the betterment of mankind that transcended national boundaries. His goal became to balance world power and to prevent nuclear blackmail. As he saw it, science was his weapon in a war to protect humanity.” If this is what ‘Dark Lives’ consists of, it is very feeble, and represents the tired refrain that a traitor like Fuchs, who, like Sonia, took advantage of British citizenship, and then betrayed his adopted home, should somehow be forgiven because he was ‘sincere’. (Shortly before she died, Lorna Arnold, the official historian at AERE Harwell, gave Frank Close a similar testimony.) ‘An unwavering set of ideals’ – much the same could be said of Lenin, and Stalin, all the way to their grisly imitators such as Pol Pot, all laced with the vague narcissistic illusion that the hero of our tale had it in his hands the ability ‘to balance world power’. It is a shoddy ending to a weakly-conceived and ill-timed book.

Ms. Greenspan needed some help with her writing, as she acknowledges no less than sixteen persons who read ‘most or some of the manuscript’, a handful who helped her with German and Russian translations, another twelve who made suggestions or who provided introductions, and archivists from thirty or so libraries who pointed her in the right direction, as well as her team of agents, editors, project managers, an endnote compiler, and a copy editor. As an author who had to perform my own copy-editing with no benefit of outside readers, and was obliged to reconstruct my own text after an ‘experimental’ editor mangled my words and punctuation, who had to create all the footnotes and endnotes, create the Affinity Charts and Biographical Index, select and organize the illustrations, undertake the laborious task of constructing an index, recruit my own PR agency, and then, when a copy of Misdefending the Realm was requested for review purposes by the Times Literary Supplement, had to order a copy from amazon for the reviewer since my editor had taken off for India for a month without informing me, I was both overwhelmed and disenchanted. It is rather like comparing two expeditions to the Hindu Kush. The Zoological Society would take hampers of chutney, chocolate and champagne with them, and recruit a posse of porters and ponies to carry their provisions, while Eric Newby or Eric Shipton would go alone, with a rucksack on their backs. But it is the solo explorers who bring back the more intriguing stories.

An Impeccable Spy, by Owen Matthews (2019)

The only major feature wrong with this book is its title. If a spy were truly ‘impeccable’, he (or she) would be infiltrated silently into a target institution, would extract vital secrets and deliver them to his controllers without ever being detected, his achievements would never be lauded and publicized, and he would die in obscurity, his name and cryptonym forever a secret. No doubt there have been persons like that. But there would be no material to write biographies of them.

Richard Sorge (the subject of Owen Matthews’ book) was far from that model. He behaved ostentatiously, drawing attention to himself, he was caught by the Japanese, he confessed his crimes, and was eventually hanged. Up until the last day he believed that Stalin would rescue him in some exchange deal because of his dedication, and the value he had brought to his bosses. Yet that was not the way Stalin thought. Sorge was a failure because he had got himself caught. And maybe Sorge knew at heart that a return to Moscow might mean death at the hands of his employers. After all, in Stalin’s eyes, Sorge had lived too long abroad, would clearly have been subject to non-communist influences, and might disapprove of how Stalin had distorted the Bolshevik impulse. Moreover, he was half-German. Let him swing.

Biographers of spies have to spice up their stories to attract attention, admittedly. ‘The Most Dangerous Spy in History’ (Fuchs, according to Frank Close); ‘The Spy Who Changed the World’ (Fuchs, according to Mike Rossiter); ‘Moscow’s Most Daring Wartime Spy’ (Sonia, according to Ben Macintyre), ‘The Spy Who Changed History’ (Shumovsky, according to Lokhova), etc. etc. Matthews appears to have taken his inspiration from Kim Philby, perhaps a dubious authority in this métier. Philby is quoted on the dust-jacket as stating that Sorge’s ‘work was impeccable’, John le Carré, for good measure, classifies Sorge as ‘the best spy of all time’, and Ian Fleming is recorded on the cover as claiming that Sorge was ‘the most formidable spy in history’, all reflecting an enthusiasm for bohemianism and extravagance rather than patience and discretion.

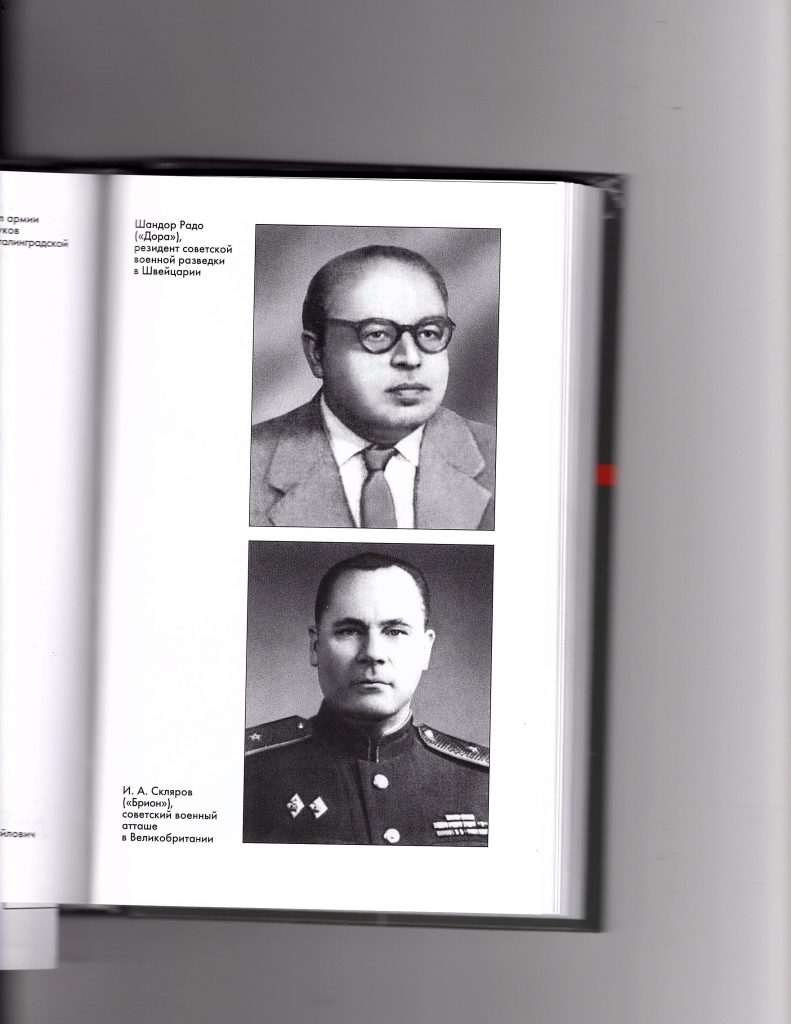

Sorge’s life was a rambunctious and exhilarating one. He was born in 1895 in Baku, in the Russian Empire, of a German father and Russian mother. He served on the Western Front, where he became a communist. After the Russian revolution, he moved to Moscow, where he was recruited by the Comintern, and roamed around Europe on various missions, including a short stay in the United Kingdom in 1929. Shortly after that, he was instructed to join the Nazi party with cover as a journalist, and sent to Shanghai, China in 1930, to join a motley international group of ne’er-do-wells, conspirators, saboteurs, spies and activists, and among his sexual conquests were Agnes Smedley and Ursula Hamburger (Sonia). (In Agent Sonya, Ben Macintyre has written: “Exactly when Ursula Hamburger and Richard Sorge became lovers is still a matter of debate.” That may be so in London, but in the circles in which I move, the precise date of that tempestuous event has never been a topic of conversation.) On a return to Moscow in 1933, where Sorge got married, he received fresh instructions to go to Japan and organize an intelligence network, since Stalin was more concerned about the threat from the East than he was of the Nazi menace. He went there via Germany, where he was able to build links with the Nazi Party, and thereafter led a stressful double life of hobnobbing with Nazi officials while building contacts with the Japanese government, and recruiting Max Clausen to send his reports to Vladivostok by wireless. He provided much valuable information to Stalin – although some of it is overrated – but the Japanese penetrated his ring, and he was arrested on October 18, 1941, interrogated and tortured. He then confessed, and was hanged on November 7, 1944.

I was familiar with Owen Matthews from an earlier work of his, Stalin’s Children (2008), which was not literally about the Dictator’s own offspring, but consisted of an uneasy combination of private memoir and serious history. It was an affecting and occasionally moving composition, uncovering the stories of Matthews’ maternal Russian grandparents (his grandfather was killed in the purges of 1937, and his grandmother lost her mind in the Gulag), and the love-affair of his own parents. (The granting of his mother’s visa to leave for Britain was part of the deal to free the Krogers, noted above.) Yet I found it flawed, owing to some mystical nonsense about ‘blood memory’, a lot of speculation about his grandfather’s thoughts and intentions, the insertion of many now familiar stories of the Ukrainian famine and the Purges, too much shy-making information on the author’s own love-life, and an irritatingly but no doubt fashionably erratic approach to the chronology of his story. The book was 50% longer than it needed to be.

Matthews, who spoke Russian before he learned English, studied Modern History at my alma mater, Christ Church, Oxford, and then pursued a career as a journalist, working in Moscow from 1997. His account of Sorge’s life is methodical, and sensibly cautious about many of the rumours that surrounded Sorge’s career in the muddle of Shanghai and wartime Japan. (I must confess that I have not read any other of the Sorge biographies, so cannot compare.) He has had access to American, German, Russian and Japanese archival sources, with necessary assistance in translation, and professes a large and learned bibliography. There is little of the Pincherite speculation about assignments and recruitment (e.g. ‘Hollis’s position at BAT would have been of interest to the GRU’ and ‘Sorge could have encountered Hollis there [at the YMCA]’: Treachery, page 46).

Matthews does comment on the Hollis case, however, although mainly in an endnote (of which there are many rich examples). On pages 367 and 368 he spends perhaps too much space on a topic that is not germane to the Sorge story, echoing the line of the Pincherite-Wrightean clique of faux-historians. He states that ‘there is evidence that Luise Rimm [the wife of a GRU operator] had a love affair with Roger Hollis that lasted three years’, and he accuses Hollis of being deceptive about his movements in China and Moscow. He is firmly of the belief that Hollis alone was able to shield Sonia from investigation, concluding, rather lamely: “The record is clear that Hollis was that protective hand, for reasons that make no apparent sense unless he was the agent ‘Elli’ and was working, like Sonja, for the GRU”. It would have been better for Matthews to have stepped back from this particular controversy.

I found a few mistakes about personalities and organisation. Matthews introduces Peter Wright as ‘the Australian-born head of MI5 counter-intelligence’, which is wrong on two counts. And he gets a bit carried away about Shanghai in the 1920s. One sentence stands out, on pp 57-58: “In the 1920s Shanghai hosted many of the great Soviet illegals of the age – Arnold Deutsch (who went on to recruit Kim Philby), Theodore Maly (later controller of the Cambridge Five), Alexander Rado (one of the many agents who would later warn Stalin of Nazi plans to invade the Soviet Union), Otto Katz (one of the most effective recruiters of fellow-travellers to the Soviet cause from Paris to Hollywood), Leopold Trepper (founder of the Rote Kapelle spy ring inside Germany before the Second World War), as well as legendary Fourth Department illegals Ignace Poretsky and Walter Krivitsky, Ruth Werner [Sonia] and Wilhelm Pieck.” No matter that this was the decade before Sorge arrived, that not all of these characters were ’illegals’, and that none of them was mythical. Sonia did not arrive there until 1930, and Agnes Smedley would have been very upset to have been omitted from this list of desperadoes. How a lot of problems would have been forestalled if this crew had been mopped up at the time and locked away where they could do no damage!

The account of Sorge’s eventual entrapment and arrest is very dramatic, and Matthews tells it well. I was particularly interested, because of my research into Sonia’s activities, in the attempts to determine the location of Clausen’s transmitter, as one would think that the Japanese would have been ruthless and efficient in tracking down illicit transmissions. Matthews reports: “Thanks to their own radio monitoring, and after a tip-off from the military government in Korea, the Japanese authorities knew that a powerful illegal transmitter was regularly operating from various sites in the Tokyo area. An all-points bulletin was sent out to all municipal police stations, including Toriizaka, to try to spot the source of the signals. But the Japanese were never able to successfully triangulate Clausen’s radio. And happily for Sorge, the Russian military code he used proved unbreakable – though the messages were faithfully monitored and transcribed by the Japanese in an ever-thickening file of unintelligible strings of number groups.” It seems to me that because of the wavelengths that Clausen would have been using, and the peculiar shape of Japan, and its mountains, that detecting the exact location of Clausen’s transmissions (and he did sensibly move around) turned out to be impossible.

Matthews’s final judgment endorses the view that Sorge was impeccable because he was ‘brave, brilliant and relentless’, and he laments the Soviet Union’s overall indifference to him, and the fact that it engaged in ‘the ultimate betrayal of its greatest spy.’ “It was Sorge’s tragedy that his masters were venal cowards who placed their own careers before the vital interests of the country that he laid down his life to serve” is the last sentence in Mathews’ book. Well, that is one way of looking at it. But you could also say that he was just like every other Stalinist dupe: he was consumed by a dopey ideology, believed that he was one of the charmed saviours of humanity, and completely overlooked the evidence that pointed to the fact that Stalin was a monster who would show no compassion or mercy when his underlings were no longer of use to him. One of Matthews’ excellent commentaries contains the following chilling fact (p 179): Soviet military intelligence had six different heads between 1937 and 1939, five of whom would be executed. The Hall of Fame consists of the following:

Jan Berzin, 1924-April 1935

Semyon Uritsky, April 1935-July 1937

Jan Berzin, July 1937-August 1937

Alexander Nikonov, August 1937-August 1937

Semyon Gendin, September 1937-October 1938

Alexander Orlov, October 1938-April 1939

Ivan Proskurov, April 1939-July 1940

Filipp Golikov, July 1940-October 1941

Alexei Panfilov, October 1941-November 1942

Not a career to be undertaken lightly. One might wonder why Jan Berzin, the second time round, didn’t reflect on the opportunity, and select a quieter and less hazardous occupation, such as deep-sea diving. But you couldn’t do that with Stalin. Once you were in the maw, you had no control. And the same for Sorge. Despite its occasional missteps, I recommend this book highly.

Master of Deception: The Wartime Adventures of Peter Fleming, by Alan Ogden (2019)

Most readers will probably recall Peter Fleming as the elder brother of Ian Fleming, or the husband of Celia Johnson, whose controlled performance of thwarted passion made Brief Encounter such an iconic film. That story of how Sonia (Celia Johnson) met Klaus Fuchs (Trevor Howard) at Birmingham’s Snow Hill Station, and then how the couple had to subdue their romance for the cause of delivering atomic secrets safely to the Soviet Embassy [are you sure this is correct? Ed.], was a box-office hit in 1945, and notable for the cameo performance by Joyce Carey playing Myrtle Bagot [sic! Milicent’s sister?], an MI5 officer under cover as the restaurant owner. Perhaps more authentically, I remember being introduced to Fleming in his travel-book, Brazilian Adventure (1933) about a poorly-organized search for Percy Fawcett, which entertained me because the author appeared to parody himself. I thus keenly consumed his One’s Company (1934) and News from Tartary (1936), in which his cover as a journalist allowed him to perform some intelligence-gathering on behalf of MI6. (There is no evidence that he had an affair with Sonia while he was in Manchukuo, and Sonia wisely decided to omit all references to any such liaison in her memoir.) His account of Hitler’s plans after the invasion of Britain, Invasion 1940, was of great historical interest to me. Finally, I enjoyed Duff Hart-Davis’s biography of Fleming, published in 1974.

Thus I jumped at the opportunity to learn more when Alan Ogden’s Master of Deception appeared last year, especially since it carried a warm endorsement from Professor Glees on the back cover. Alan Ogden was not a name I knew, but, since he has written several books about the Special Operations Executive, especially concerning activities in a region of the world that I find utterly absorbing – Transylvania, Romania, and parts of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire – I thought that it was an omission that I should quickly remedy. Ogden has set himself the task of documenting Fleming’s war experiences in the Military Intelligence Directorate (MIR) and then in what Ogden calls the ‘mysterious’ D. Division, which was responsible for deception in the Far East.

Part of the problem of recording faithfully what went on in military intelligence circles is the tendency to be overwhelmed with acronyms, liaison officers, operational code-names, and a host of minor figures, the Biffies, Jumboes and Tigers who populated this realm. (Ogden recognises part of this challenge in his Preface, where he declares his aim to reduce the ‘alphabet soup’. Yet he provides no glossary of acronyms, and his Index is very weak.) Thus it requires a large amount of concentration and patience to keep up with the stream of codewords and rapidly changing military units that evolved as the war changed its shape. Another hurdle for the author to overcome, however, is more paradoxical, and more serious. Even though Fleming is characterised as the ‘Master of Deception’, his schemes and campaigns were essentially failures – not because of his lack of inventiveness, but because the enemy refused to bite, or because the battle was lost for external reasons. A campaign record of Norway, Greece, the Pacific and Burma is not the most illustrious showcase for how deception operations won the day.

I have recently studied the deception campaign supporting the Normandy landings (see https://coldspur.com/the-mystery-of-the-undetected-radios-part-8/ ), and it was informative to discover that much of the investment that the Allies put into the movements of dummy armies was wasted because the Germans did not have the capacity nor the imagination to interpret all the fake signals and equipment that were constructed to convince them of the existence of FUSAG. The Nazis were nowhere near to building a picture of the organisation and order of battle of the Allies to match what British and American intelligence had constructed concerning Nazi forces. Thus Germany came to be completely reliant on its crew of agents, who had either been ‘turned’ or had signed up for the Abwehr originally with the intention of working for the opposition. And British intelligence was able to manipulate the Abwehr and its successors simply because they wanted to be misled.

Whereas deception, under Lt.-Colonel Dudley Clarke’s ‘A’ Force, had been successful in Africa, it was a struggle in the war in Burma and the frontiers of Japanese-controlled territory. As Fleming himself wrote in a report: “There can be no question that the Japanese Intelligence was greatly inferior in all respects to the German and even the Italian Intelligence. The successful deception practiced on the Axis military machine in Europe was made possible by the fact that the enemy’s Intelligence staffs and services were, though gullible, well organized and reasonably influential.” As Ogden concludes, D. Division’s plans were too sophisticated: Philip Mason, head of the Conference Secretariat (SEAC), echoed Fleming’s judgment: “Deceiving the Germans had been very different; they wanted to know our plans and expected us to try and deceive them. That had been like playing chess with someone not quite as good as oneself.; with the Japanese, it was like setting up the chessboard against an adversary whose one idea was to punch you on the nose.”

Fleming was to explain failure in other ways, such as a lack of knowledge with the deception planners as to what military strategies actually were in a chaotic and dispersed region – very different from what existed in the European theatre. But a naivety about deception, and maybe an overestimation of achievement, and a lack of understanding of how controlling agents was supposed to work, were evident in other activities. Ogden reports how, in March 1943, our old coldspur friend John Marriott was sent to India to advise on how a new section should be formed to handle double-agents (a formulation that immediately highlights a problem, as you cannot be sure you have ‘double-agents’ until you have trained them, and brought them strictly under your control). Ogden reports: “Marriott’s credentials were impeccable save in one respect. He had never been to India, and knew next to nothing about its peculiarities, impediments and handicaps.” Marriott was very critical of the set-up in India, and Fleming appeared to have been rather disdainful of Marriott’s practical experience. For where were these double-agents going to come from? Who arrested them, interrogated them, and who was to ‘turn’ them, and ensure that they were loyal to you? Moreover, Fleming frequently upset the military brass with his unconventionality. One judgment recorded by Ogden is that of Colonel Bill Magan, one of the officers in the Delhi Intelligence Bureau. He found Fleming ‘an irresponsible, ambitious and irrational man who was always trying to persuade us to pass messages which we believed would “blow” the channel.’

Ogden has clearly done his homework, as is shown by the hundred or so files from the National Archives that he lists in his Sources, and whose contents are faithfully reflected in his text. But it becomes a bit of a trudge working through his story to find the nuggets. Too many multi-page reports are embedded, when they should preferably have been summarized, and the complete versions relegated to Appendices. Much detail about operations, which is surely of considerable value to the dedicated military historian, could have been left out in order to focus more tightly on the author’s main thrust, and Fleming sometimes gets lost in the caravanserai.

Yet nuggets there certainly are. I was delighted to add the following assessment to my dossier on Roger Hollis. In August 1939, Fleming was invited to submit his recommendations as to who, among associates he had known, might be useful to the war effort, and offered, among his testimonies, that Hollis ‘Did several years in China with BAT’, adding: “Though he has not been there recently, his judgement of Far Eastern affairs has always impressed me as unusually realistic. His cooperation, or even his comments, might be valuable at an early stage, particularly as he is available in London.” Nothing appeared to come from this, but the outwardly rather dim Hollis had impressed someone who knew what he was talking about, and gained a fan of note. (My dossier has also been enriched this month by one of the more memorable phrases in Ben Macintyre’s Agent Sonya: “He [Hollis] was a plodding, slightly droopy bureaucrat with the imaginative flair of an omelet.”)

Another gem consists of a paper that Fleming wrote in Chungking in 1942, titled ‘Total Intelligence’, which, by using the fictitious example of Ruritania in 1939, outlined how a diverse set of intelligence sources could be harnessed without consolidating the gatherers of intelligence into one massive organisation. The paper takes almost ten pages of text, and should thus likewise have been a candidate for appendicisation, but it deserves broader exposure, and is well worth reading. I was a bit puzzled, however, by Ogden’s brief commentary on this report, where he indicates that, addressing Fleming’s criticism, SOE went out of his way to recruit business men and bankers to assist them in undermining the enemy. But SOE was a sabotage organisation, not an intelligence-gathering unit (although intelligence came its way by way of its destructive exploits), and I should have liked Ogden to explore this dilemma – one so keenly understood by MI6 – in a little more depth.

So what is the verdict on Fleming? Ogden’s assessment is a little surprising. He writes (p 274): “As the new world order unfurled, with his knowledge of and experience in dealing with Russia and China, he was eminently well qualified for a top post in either SIS or MI5.” That seems to me an errant call. Fleming had no insider reputation in the Security Service or the Secret Intelligence Service, and his sudden appointment would surely have provoked resentment. Moreover, I believe he was temperamentally unsuited for roles that required tact, patience, and an ability to negotiate with Whitehall. He was an adventurer, a maverick, and would have bridled at all the protocols and formalities of communicating with career civil servants – something that Dick White was famously good at. It is not surprising that Fleming took early retirement as a gentleman farmer.

‘Master of Deception’ he may have been, but the targets of his deception frequently failed to act like English gentlemen, or perform as they were supposed to, not having installed the obvious British-like institutions. In one important passage, Fleming’s frustrations come through. As Ogden writes, of one multi-year operation that had minimal impact, the HICCOUGHS project, which planted a network of notional agents in Burma, and somehow caused them to send messages back to Delhi (p 228): “For two years, Fleming and the HICCOUGHS case attached little importance to this rather tiresome routine commitment since it was transparently flawed. ‘Why,’ asked Fleming, ‘if our agents could communicate with us by W/T, could we not communicate with them by the same means? Why, if we were forced to broadcast messages to them, did we continue to use a low-grade cipher? How was it that they were all (apparently) able to listen in twice daily at fixed times to receive a message when in most cases it affected only one of them? How was it that the Japanese Radio Security Service never obtained the slightest clue to the places and times at which they transmitted their lengthy and invaluable reports? Why, after all this talk about sabotage and subversion, did nothing ever happen?’”

This was perhaps an admission that ingenuity alone was not enough. It needed comprehensive understanding and support from the military organisation, and it required, even more, a proper assessment of the psychology of the enemy, insights into how its intelligence units thought, and a clear idea of what behavioural changes the operation was trying to achieve. Causing confusion was not enough.

Secret: The Making of Australia’s Security State, by Brian Toohey (2019) [guest review by Denis Lenihan]

Even taking into account the generation gap, there are some remarkable similarities between Brian Toohey (born 1944) and Harry Chapman Pincher (1914-2014). Both began their journalistic careers in conventional fields, Toohey in finance, although the Australian Financial Review when he joined it in the 1970s had perhaps a somewhat broader range than now. Pincher’s field was initially defence and science on the Daily Express in the Beaverbrook days after the war. Both had the gift or the knack of attracting confidences, so that senior figures in government leaked material which they wished to see released, for varying reasons. The historian E P Thompson described Pincher as

“a kind of official urinal in which, side by side, high officials of MI5 and MI6, sea lords, permanent under-secretaries, Lord George-Brown, chiefs of the air staff, nuclear scientists, Lord Wigg and others, stand patiently leaking in the public interest. One can only admire their resolute attention to these distasteful duties.”

Pincher’s sources went beyond that group, taking in those who went fishing or pheasant or grouse shooting in season – cabinet ministers, industrialists, well-informed nobles – when some on Pincher’s account became much more willing to divulge secrets, or at least matters which were classified as secrets. It was not a difference that they or Pincher always recognised. Toohey’s only overseas posting was to Washington, and his social circle was more restricted; and if there were any grouse shooters among his sources, he has been careful to protect them.

While Pincher will be well-known to readers of coldspur.com some further information on Toohey might be helpful. He has written about national security policy since 1973 and is the author or co-author of four books, including Oyster: The Story of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (1989). After part of the manuscript came into the Australian (Labor) Government’s possession, it took court action which resulted in the book effectively being vetted by the Government. A sensible approach saw only one major deletion, the name of a public relations firm, an omission remedied soon after the book’s publication by another journalist who published not in The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age (Melbourne).

Pincher became interested in spies in 1950 when he covered the trial of Klaus Fuchs, the atomic spy. Pincher informed his editor that a spy named Fuchs had been arrested, and the editor said ‘Marvellous! I’ve always wanted to get that word into a headline.’ As noted, Toohey has written about national security matters since 1973, while he was still at the AFR, perhaps more so later when he moved to the late-lamented National Times. Both believed in lunch as a setting where people talked; French was Pincher’s cuisine of choice, habitually at A L’Ecu de France in Jermyn St Piccadilly. His footnotes show that Toohey followed suit on at least one occasion, at La Bagatelle in Washington, but in New York he went to the Union Club (founded 1836), the cuisine in which was unlikely to have been French. No Canberra restaurant is mentioned. Perhaps Toohey was wise to move about. After A L’Ecu closed in the 1990s, Pincher was told by the senior director that MI5 had bugged the banquettes, including the one favoured by Pincher. A later development of the story had it that when MI5 went to remove the bugs, it found another set – put there by the KGB. Whether it’s true or not is irrelevant: it’s a great story. Pincher evidently had a very good memory and drank little. After lunch he would return to his office and dictate the story without reference to documents. ‘…I have always had a golden rule’, he recorded in 2013,’ that I would never touch or look at any classified documents’. (Foreword to Christopher Moran: Classified: Secrecy and the State in Modern Britain (2013)). Toohey seems to have got documents frequently but after writing his story he would very sensibly destroy them, thus putting himself beyond the reach of his official pursuers who often took him to court.

Reading along and between the lines in Toohey’s book Secret: The Making of Australia’s Security State (2019) suggests that most of his sources were public servants. As with Pincher, much public money was spent on attempting to find out who they were, evidently without success. Both lived or have lived long enough to be able to see from government files released to archives the attempts made to identify their sources. After Pincher had published in 1959 details of a cabinet decision two days after it had been made, Harold Macmillan was moved to exclaim: ‘Can nothing be done to suppress or get rid of Mr Chapman Pincher’. Pincher’s books contain the explanation for many of the characteristics of Australian government which Toohey rightly complains about: unwarranted secrecy and lies, particularly by security agencies. The UK system of government has for decades prized secrecy, very often in circumstances where it was later shown to be unnecessary and even harmful. In Treachery, Pincher is able to show that time and again MI5 in particular lied to ministers and even the Prime Minister, to the extent of being publicly reproved. In 1963 Harold Macmillan criticised Sir Roger Hollis, the Director General of MI5, in the House of Commons for keeping from him critical information during the Profumo affair.

As time goes by, more and more ludicrous examples emerge. In 1940 Neville Chamberlain while still Prime Minister commissioned Lord Hankey to investigate the efficiency of the intelligence services. His report has never been released in the United Kingdom, which had prompted much speculation about its contents. The spy John Cairncross had at the time slipped a copy to Moscow and in 2009, in its well-known role of assisting scholarship, the Soviet archives released it. Fallen upon by scholars eager to find its secrets, it turned out to be in the words of one reader ‘mostly pedestrian and superficial’.

That tradition of too much secrecy and too many lies was bequeathed to Australia and the other colonies and continues to bedevil them, as Toohey shows. He became the bete noire of Sir Arthur Tange, the Secretary of the Department of Defence, whose ‘demands to find the leakers chewed up the time of senior officials who had more important things to do than pursue often inept and always futile investigations’. Tange might usefully have followed the precedent of his UK counterpart, Sir Richard Powell, who advised his minister in 1958 with regard to Pincher that

“I believe that we must live with this man and make the best of it. We can console ourselves that his writings, although embarrassing at times to Whitehall, disclose nothing that Russian intelligence does not already know.”

Toohey’s jousts with the establishment make for enjoyable reading, and on most issues (nuclear bomb testing in Australia, ‘the depravity of nuclear war planning’ etc) he is on the side of the angels, even if sometimes he does not quote prominent supporters such as the Pope who give weight to his causes. Given that most of the Pope’s clergy and his flock do not at least in public echo his views on the bomb, Toohey’s omission is forgivable.

When he strays outside his area of expertise, however, as he does when arguing that out of the thirteen wars Australia has fought, only one (the Pacific theatre of World War II) was ‘a war of necessity for Australia’, Toohey stumbles. Some of the thirteen pre-dated the establishment of Australia in 1900, and while his argument might be true looking backwards, there was no prospect in say 1914 that Australia would not join in the defence of what was then called the mother country, especially when all her other white daughters enrolled. Toohey must also be one of the very few Australian commentators to have written about the Japanese and World War II and who have failed to mention the bombing of Darwin and the invasion of Sydney Harbour by midget submarines, both in 1942.

All this makes it very disappointing that Toohey should be so far off the mark in the very first chapter of his book (there are 60 chapters, some of them very short), which deals with ‘The Security Scandal that the US Hid from the Newborn ASIO’, as the chapter heading has it. The scandal concerned the Venona material, messages which passed between Moscow and its embassies in a number of countries, including Australia, in the 1940s, many of which were intercepted by the US or its allies (or by neutral countries such as Sweden) and some of which were able to be decoded or deciphered. On Toohey’s account, an NSA employee, William Weisband, was a KGB spy and told Moscow in 1948 about the interceptions and the encryption methods were then changed. Again on Toohey’s account, ASIO was never told about this betrayal. All these assertions are worth examining in some detail, together with Toohey’s account of what the Australian Venona material revealed.

Toohey begins by claiming that ‘the highly classified material handed over by the Australian spies was of no consequence’, in particular the two top-secret UK planning papers passed over in 1946 which showed ‘banal, often erroneous predictions’; further, the predictions were ‘fatuous’ while the other papers passed over were ‘trite’. That some of the predictions turned out to be wrong, and that some of the other material seemed to be unimportant, are hardly sufficient to dismiss them altogether. Given some indication by the Soviet Embassy in Canberra of the contents of the two top-secret reports, Moscow asked that they be sent immediately by telegram, which is a good indication of what it thought of them at the time. A more objective account of the Canberra Venona is to be found in Nigel West’s Venona (1999), where he describes one of these two documents as being ‘of immense significance’, and says that for it to have fallen into Soviet hands at that time was ‘devastating’.

In any event, Toohey fails to mention that in the estimation of the US National Security Agency which released the Venona material in the 1990s ‘More than 200 messages were decrypted and translated, these representing a fraction of the messages sent and received by the Canberra KGB residency.’ (NSA website). It is idle to suppose that those not intercepted contained no important classified material.

Toohey also misrepresents the messages sent by Moscow to the senior MI5 officer in Canberra, Semyon Makarov: ‘Moscow told Makarov not to let [Clayton, the Communist Party member who was the contact man for the spies in External Affairs] recruit new agents, not to send any document that was more than a year old, not to be overeager to achieve success and to stop obtaining information of little importance.’ What Moscow in fact said to Makarov was‘…if possible do not take any steps in the way of bringing in new agents without a decision from us’ (message of 6 October 1945); ‘you should not receive from [Clayton] and transmit by telegraph textual intelligence information that is a year old’ the implication being that it might be sent by bag (message of 17 October 1945); and that [Nosov, the TASS correspondent in Sydney] should be brought into the work ‘but do not be over-eager to achieve success to the detriment of security and maximum caution’ (message of 20 October 1945). This kind of close supervision by Moscow was not unusual, as West’s book shows.

Individual members of the External Affairs spy ring are declared to be innocent. Ric Throssell is described thus: ‘After interviewing him in 1953, ASIO concluded that he “is a loyal subject and is not a security risk in the department in which is employed” ‘. Quite true, but incomplete. After Petrov’s defection in 1954, ASIO formed the view that Throssell could not be given a security clearance for classified material, and he never was. Frances Garratt (nee Bernie) is described by Toohey as ‘working mainly on political party issues as a young secretary/typist in the Sydney office of the External Affairs minister, Bert Evatt..She insisted that she thought she was simply giving the local Communist Party some political information.’ Again, incomplete. As Robert Manne noted in The Petrov Affair (1987), the Royal Commission on Espionage found that

“While Frances Bernie had certainly broken the law – in passing official documents to Walter Clayton without authorisation – she had only admitted to doing so having been granted an immunity from prosecution.”

And according to the late Professor Des Ball, ‘In 2008, Bernie admitted that she had given Walter Seddon Clayton (code-named KLOD or CLAUDE), the organiser and co-ordinator of the KGB network, much more important information than she had previously confessed’. (‘The moles at the very heart of government’, The Australian, April 16, 2011)

The scandal referred to in the chapter heading is this. As noted, on Toohey’s account the Venona secret was betrayed to Moscow by William Weisband, a Soviet spy employed by the National Security Agency, and in 1948 the Soviet encryption systems were changed. Toohey takes up the story:

“I asked ASIO when the US informed it (or its predecessor) that Weisband had told the Soviets that Venona was able to read its messages; ASIO replied in an email on 30 June 2017: ‘The information you refer to is not drawn from ASIO records.’ ASIO also told the National Archives of Australia (NAA) that it does not hold any open period records (i.e.up to 1993) about the US notifying it that Weisband told the Soviets about Venona. The US should also have told the Defence Signals Directorate (now the Australian Signals Directorate, or ASD). When I asked ASD, via Defence, it declined to answer.”

It is worth noting here that entering ‘William Weisband’ and ‘National Security Agency’ into the Australian Archives website yields only references to public material about the Agency. Entering ‘William Weisband’ into the website of the UK National Archives yields no result; while the only two results for ‘National Security Agency’ are for files from the Prime Minister’s Office concerning the publication of material about the Agency. Toohey would presumably not argue on the basis of these results that the Agency did not tell the UK security authorities about Weisband. The strongest argument against Toohey’s claim is that entering Weisband’s name into the website of the US National Archives and Records Administration yields only scraps, and nothing connected directly to the NSA. Clearly NSA guards its records zealously, as one would expect. It was at one time so secret that its initials were said to mean ‘No Such Agency’.

In any event, ASIO did not come into existence until 1949, and on Horner’s account in Volume 1 of the history of ASIO – The Spycatchers – he and his research team ‘found files that ASIO did not even know they had.’ Relying on ASIO records, especially from the early days, is thus a chancy business.

So no scandal here – or not yet anyway.