Guy Liddell’s ‘Guardian’ – Nigel West

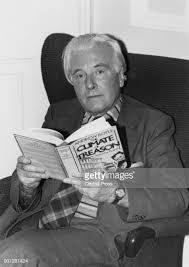

I have met Nigel West, the pen name adopted by Rupert Allason, the undisputed doyen of British writers on intelligence matters, on three occasions, as I have recorded in previous blogs. I met him first at a conference on wartime Governments-in-Exile at Lancaster House several years back, and he kindly agreed to come and listen to the seminar on Isaiah Berlin that I was giving at the University of Buckingham the following week. We exchanged emails occasionally: he has always been an informative and encouraging advisor to researchers into the world of espionage and counter-espionage, like me. A couple of years ago, I visited him at his house outside Canterbury, where I enjoyed a very congenial lunch.

Shortly before Misdefending the Realm appeared, my publisher and I decided to send Mr. West a review copy, in the hope that he might provide a blurb to help promote the book. Unfortunately, Mr. West was so perturbed by the errors in the text that he recommended that we withdraw it in order to correct them. This was not a tactic that either of us was in favour of, and I resorted to quoting Robin Winks to cloak my embarrassment: “If intelligence officers dislike a book, for its tone, revelations, or simply because the find that one or two facts in it may prove compromising (for which, also read embarrassing), they may let it be known that the book is ‘riddled with errors,’ customarily pointing out a few. Any book on intelligence will contain errors, given the nature and origin of the documentation, and these errors may then be used to discredit quite valid judgments and conclusions which do not turn on the facts in question.” (Robin W. Winks, in Cloak & Gown: Scholars in the Secret War, 1939-1961, p 479) Since then, therefore, I have not dared to approach Mr. West on questions of intelligence where I might otherwise have sought his opinion.

I would still describe myself as being on friendly terms with Mr. West, though would not describe us as ‘friends’. (No collector like Denis Healey or Michael Caine am I. I count my friends in this world as a few dozen: most of them live in England, however, which makes maintenance of the relationship somewhat difficult. On my infrequent returns to the UK, however, I pick up with them as if I had last seen them only the previous week. What they say about the matter is probably better left unrecorded.) And I remain an enthusiastic reader of Mr. West’s books. I have about twenty-five of his publication on my shelves, which I frequently consult. I have to say that they are not uniformly reliable, but I suspect that Mr. West might say the same thing himself.

His latest work, Cold War Spymaster, subtitled The Legacy of Guy Liddell, Deputy Director of MI5, is a puzzling creation, as I shall soon explain. Two of Mr. West’s works on my bookshelf are his editions of Guy Liddell’s Diaries – Volume 1, 1939-1942, and Volume 2, 1942-1945. In a way, these items are superfluous to my research needs, as I have the full set of Liddell’s Diaries on my desktop, downloaded from the National Archives website. Mr. West told me that he would have dearly liked to publish more of Liddell’s chronicle, but it was not considered economically viable. Yet I still find it useful to consult his editions since he frequently provides valuable guides to identities of redacted names, or cryptonyms used: it is also important for me to know what appears in print (which is the record that most historians exploit), as opposed to the largely untapped resource that the original diaries represent. Cold War Spymaster seems to reflect a desire to fill in the overlooked years in the Liddell chronicle.

Guy Liddell, the Diaries and MI5

As West [I shall, with no lack of respect, drop the ‘Mr.’ hereon] points out, Liddell’s Diaries consist an extraordinary record of MI5’s activities during the war, and afterwards, and I do not believe they have been adequately exploited by historians. It is true that a certain amount of caution is always required when treating such testimony: I have been amazed, for example, at the attention that Andrew Roberts’s recent biography of Churchill has received owing to the claim that the recent publication of the Maisky Diaries has required some revisionist assessment. The Soviet ambassador was a mendacious and manipulative individual, and I do not believe that half the things that Maisky ascribed to Churchill and Anthony Eden were ever said by those two politicians. Thus (for example), Churchill’s opinions on the Soviet Union’s ‘rights’ to control the Baltic States have become distorted. Similarly, though to a lesser degree, Stephen Kotkin takes the claims of Maisky far too seriously in Volume 2 of his biography of Stalin.

Diaries, it is true, have the advantage of immediacy over memoirs, but one still has to bear in mind for whose benefit they are written. Liddell locked his away each night, and probably never expected them to be published, believing (as West states) that only the senior management in MI5 would have the privilege of reading them. Yet a careful reading of the text shows some embarrassments, contradictions, and attempts to cover up unpleasantries. Even in 2002, fifty years later, when they were declassified, multiple passages were redacted because some events were still considered too sensitive. Overall, however, Liddell’s record provides unmatched insights into the mission of MI5 and indeed the prosecution of the war. I used them extensively when researching my thesis, and made copious notes, but now, each time I go back to them on some new intelligence topic, I discover new gems, the significance of which I had overlooked on earlier passes.

Describing Liddell’s roles during the time of his Diaries (1939-1952) is important in assessing his record. When war broke out, he was Assistant-Director, under Jasper Harker, of B Division, responsible for counter-intelligence and counter-espionage. B Division included the somewhat maverick section led by Maxwell Knight, B1F, which was responsible for planting agents within subversive organisations such as the Communist Party and Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists. When Churchill sacked the Director-General, Vernon Kell, in May 1940, and introduced the layer of the Security Executive under Lord Swinton to manage domestic intelligence, Liddell was promoted to Director of B Division, although he had to share the office with an inappropriate political insertion, William Crocker, for some months. As chaos mounted during 1940, and Harker was judged to be ill-equipped for leadership, David Petrie was brought in to head the organisation, and in July 1941 he instituted a new structure in which counter-intelligence against communist subversion was hived off into a new F Division, initially under John Curry. Thus Liddell, while maintaining an interest, was not nominally responsible for handling Soviet espionage during most of the war.

Petrie, an effective administrator appointed to produce order, and a clear definition of roles, was considered a success, and respected by those who worked for him. He retired (in somewhat mysterious circumstances) in 1946, and was replaced by another outsider whose credentials were superficially less impressive, the ex-policeman, Percy Sillitoe – an appointment that Liddell resented on two counts. Petrie was a solid administrator and planner: he had been in his position about a year-and-a-half when he produced, in November 1942, a paper that outlined his ideas about the future of MI5, how it should report, and what the ideal characteristics of officers and the Director-General should be. His recommendations were a little eccentric, stressing that an ideal D-G should come from the Services or Police, and have much experience overseas. Thus Liddell, who probably did not see the report, would have been chagrined at the way that career intelligence officers would have been overlooked. In the same file at Kew (KV 4/448) can be seen Liddell’s pleas for improving career-paths for officers, including the establishment of a permanent civilian intelligence corps in the services.

Petrie was reported to have kept a diary during his years in office, but destroyed it. The authorised historian, Christopher Andrew, glides over his retirement. In a very provocative sentence in his ODNB entry for Petrie, Jason Tomes writes: “In retrospect, this triumph [the double cross system] had to be set alongside a serious failure: inadequate surveillance of Soviet spies. Petrie sensed that the Russian espionage which MI5 uncovered was the tip of an iceberg, but the Foreign Office urged restraint and MI5 had itself been penetrated (by Anthony Blunt).” What Soviet espionage had MI5 uncovered by 1945? Green, Uren and Springhall were convicted in 1942, 1943 and 1944, respectively, but it is not clear why Petrie suspected an ‘iceberg’ of Communist penetration, or what sources Tomes is relying on when he claims that Petrie had evidence of it, and that he and the Foreign Office had a major disagreement over policy, and how the Director-General was overruled. Did he resign over it? That would be a major addition to the history of MI5. The defector Gouzenko led the British authorities to Nunn May, but he was not arrested until March 1946. Could Petrie have been disgusted by the discovery of Leo Long and his accomplice Blunt in 1944? See Misdefending the Realm for more details. I have attempted to contact Tomes through his publisher, the History Press, but he has not responded.

Like several other officers, including Dick White, who considered resigning over the intrusion, Liddell did not think the Labour Party’s appointing of a policeman showed good judgment. Sillitoe had worked in East Africa as a young man, but since 1923 as a domestic police officer, so he hardly met Petrie’s criteria, either. Astonishingly, Petrie’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography asserts that Petrie had recommended Liddell for the post, but had been overruled by Attlee – an item of advice that would have been a complete volte-face in light of his memorandum three years earlier. On the other hand, it might be said that Sillitoe could have well riposted to his critics, after the Fuchs affair, that the established officers in MI5 did not understand counter-intelligence either. And in another of those enigmatic twists that bedevil attempts to work out what really happened here, Richard Deacon (whose role I shall inspect later in this piece), wrote about Sillitoe in The Greatest Treason: “The picture which has most unfortunately been portrayed since Sillitoe’s departure from MI5 has been that of a policeman totally out of place in a service which called for highly intellectual talents. This is total balderdash: someone like Sillitoe was desperately needed to put MI5 on the right track and to get rid of the devious amateurs who held power.” One might ask: was that not what Petrie had been doing for the past five years?

In any case, Liddell also thought that he deserved the job himself. Yet he did receive some recognition, and moved nearer to the seat of leadership. In October 1946 he replaced Harker as Deputy Director-General, and frequently stood in for his new boss, who had a rough time trying to deal with ‘subversive’ MI5 officers, and reportedly liked to travel to get away from the frustrations of the office climate. What is puzzling, however, about the post-war period is that, despite the fact that the Nazi threat was over, and that a Labour government was (initially) far more sympathetic to the Soviet cause, B Division did not immediately take back control of communist subversion. A strong leader would have made this case immediately.

The histories of MI5 (by Christopher Andrew, and West himself) are deplorably vague about responsibilities in the post-war years. We can rely on John Curry’s internal history, written in 1945, for the clear evidence that, after Petrie’s reorganization in the summer of 1941, F Division was responsible for ‘Communism and Left-Wing Movements’ (F2, under Hollis), which was in turn split into F2A (Policy Activities of CPGB in UK), under Mr Clarke, F2B (Comintern Activities generally, including Communist Refugees), and F2C (Russian Intelligence), under Mr. Pilkington. Petrie had followed Lord Swinton’s advice in splitting up B Division, which was evidently now focused on Nazi Espionage (B1A through B1H). Dick White has been placed in charge of a small section simply named ‘Espionage’, with the mission of B4A described as ‘Suspected cases of Espionage by Individuals domiciled in United Kingdom’, and ‘Review of Espionage cases’. Presumably that allowed Liddell and White to keep their hand in with communist subversion and the machinations of the Comintern.

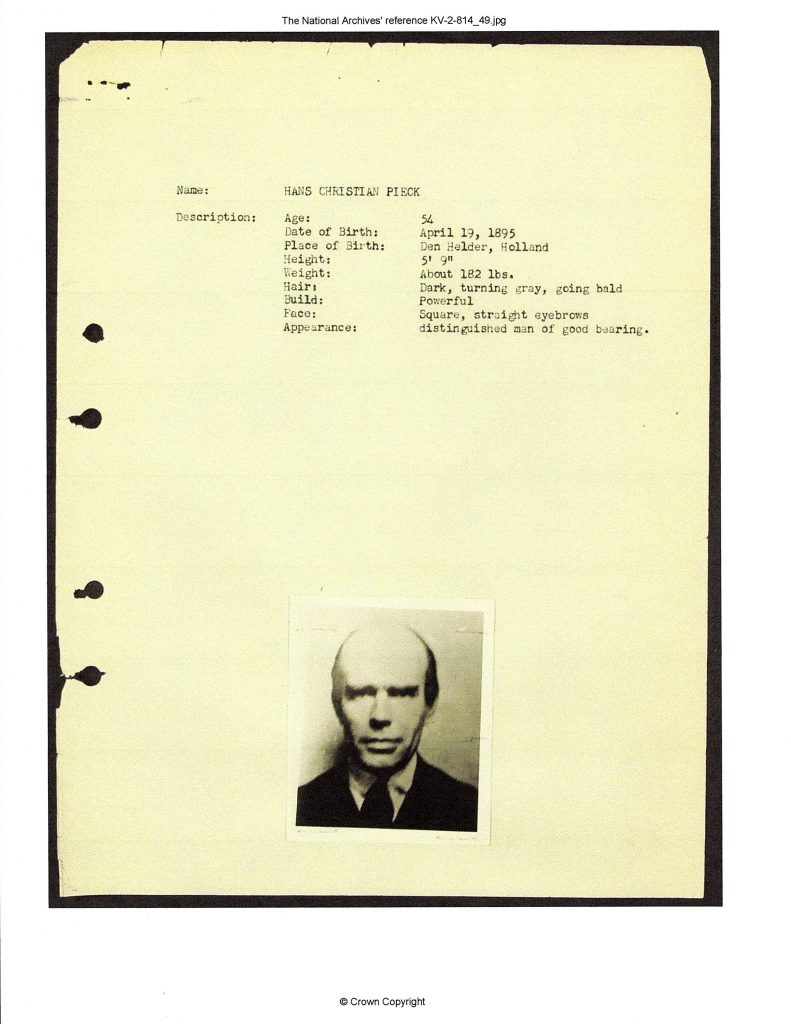

Yet that agreement (if indeed it was one) is undermined by the organisation chart for August 1943, where White has been promoted to Deputy Director to Liddell, and B4A has been set a new mission of ‘Escaped Prisoners of War and Evaders’. F Division, now under the promoted Roger Hollis, since Curry has been moved into a ‘Research’ position under Petrie, still maintains F2, with the same structure, although Mr Shillito is now responsible for F2B and F2C. With the Soviet Union now an ally, the intensity of concerns about Communist espionage appears to have diminished even more. (In 1943, Stalin announced the dissolution of the Comintern, although that gesture was a fraudulent one.) One might have expected that the conclusion of hostilities, and the awareness within MI5, and even the Foreign Office, that the Soviet Union was now the major threat (again), would provoke a reallocation of forces and a new mission. And, indeed, this appears to be what happened – but in a quiet, unannounced fashion, perhaps because it took a while for Attlee to be able to stand up to the Bevanite and Crippsian influences in his Party. A close inspection of certain archives (in this case, the Pieck files) shows that in September 1946, Michael Serpell identified himself as F2C, but by the following January was known as B1C. This is an important indicator that White’s B Division was taking back some responsibility for Soviet espionage in the light of the new threat, and especially the Gouzenko revelations of 1945. Yet who made the decision, and exactly what happened, seems to be unrecorded.

According to Andrew, after the war, B Division was highly focused on Zionist revolts in Palestine, for which the United Kingdom still held the mandate. Yet he (like West) has nothing to say about F Division between Petrie’s resignation in 1946 and Dick White’s reorganisation in 1953. The whole of the Sillitoe era is a blank. Thus we have to conclude that, from 1947 onwards, Hollis’s F Division was restricted to covering overt subversive organisations (such as the Communist Party), while B Division assumed its traditional role in counter-espionage activities, such as the tracking of Klaus Fuchs and Nunn May, the case of Alexander Foote, and the interpretation of the VENONA transcripts. The artificial split again betrayed the traditional weaknesses in MI5 policies, namely its age-old belief that communist subversion could come only through the agencies of the CPGB, and that domestically-educated ‘intellectual’ communists would still have loyalty to Great Britain. White held on to this thesis for far too long. Gouzenko’s warnings – and the resumption of the Pieck inquiry – had aroused a recognition that an ‘illegal’ network of subversion needed to be investigated. Yet it was not until the Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia, with the subsequent executions, and the Soviet blockade of Berlin in 1948, that Attlee’s policy toward the Soviets hardened, and B Division’s new charter was accepted.

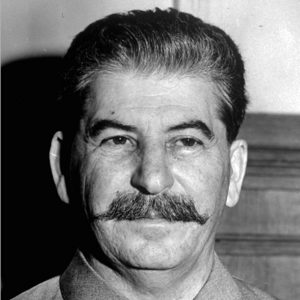

I return to West and Liddell. On the inside cover of each volume of the published Diaries appear the following words: “Although reclusive, and dependent on a small circle of trusted friends, he (Liddell) was unquestionably one of the most remarkable and accomplished professionals of his generation, and a legend within his own organisation.” Even making allowances for the rhetorical flourish of granting Liddell a ‘mythical’ status, I have always been a little sceptical of this judgment. Was this not the same Liddell who recruited Anthony Blunt and Victor Rothschild into his organisation, and then wanted to bring in Guy Burgess, only being talked out of it by John Curry? Was this the same officer who had allowed Fuchs to be accepted into atomic weapons research, despite his known track-record as a CP member, and who allowed SONIA to carry on untouched in her Oxfordshire hideaway? Was this the same officer whom John Costello, David Mure, Goronwy Rees, Richard Deacon and SIS chief Maurice Oldfield all * thought so poorly of that they named him as a probable Soviet mole? Moreover, in his 1987 book, Molehunt, even West had described Liddell as ‘unquestionably a very odd character’. Can these two assessments comfortably co-exist?

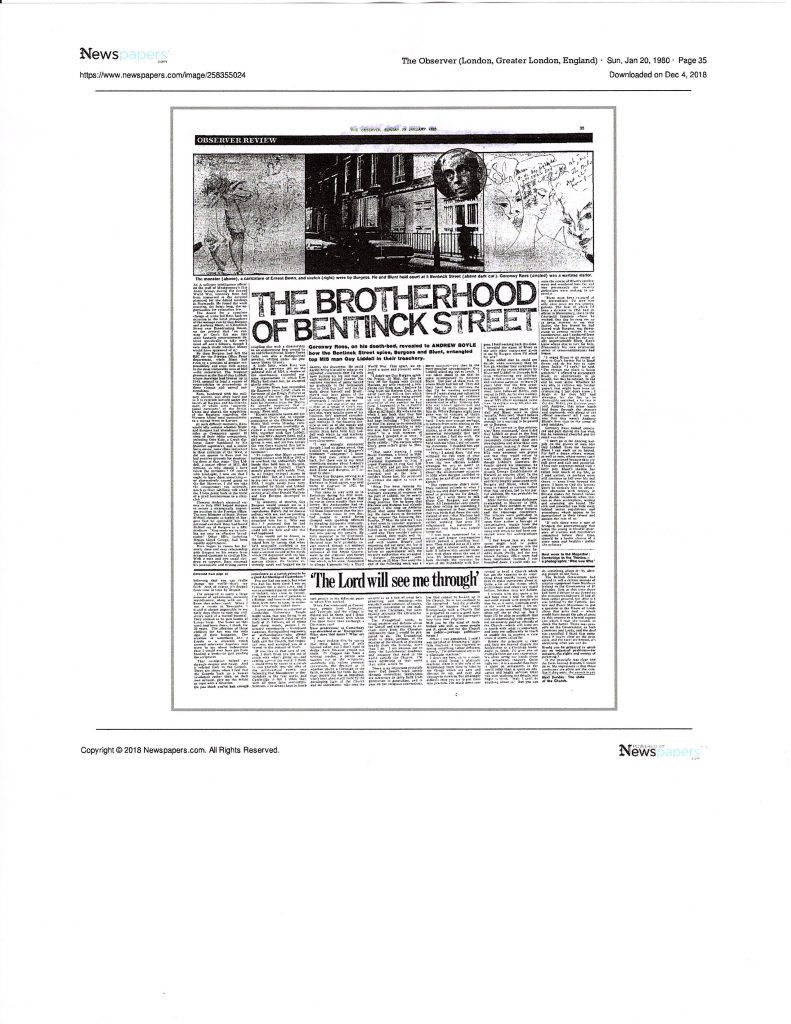

* John Costello in Mask of Treachery (1988); David Mure in Master of Deception (1980); Goronwy Rees in the Observer (1980); Richard Deacon in The Greatest Treason (1989); Maurice Oldfield in The Age, and to US intelligence, quoted by Costello.

To balance this catalogue of errors, Liddell surely had some achievements to his credit. He was overall responsible for conceiving the Double-Cross Operation (despite White’s claims to his biographer of his taking the leading role himself, and ‘Tar’ Robertson receiving acclaim from some as being the mastermind of the operation), and basked in the glory that this strategic deception was said to have played in ensuring the success of OVERLORD, the invasion of France. He supervised Maxwell Knight’s infiltration of the Right Club, which led to the arrest and incarceration of Anna Wolkoff and Tyler Kent. He somehow kept B Division together during the turmoil of 1940 and the ‘Fifth Column’ scare. His Diaries reveal a sharp and inquiring mind that was capable of keeping track of myriads of projects across the whole of the British Empire. Thus I opened Cold War Spymaster in the hope that I might find a detailed re-assessment of this somewhat sad figure.

‘Cold War Spymaster’

First, the title. Why West chose this, I have no idea, as he normally claims to be so precise about functions and organisation. (He upbraided me for getting ‘Branches’ and ‘Divisions’ mixed up in Misdefending the Realm, although Christopher Andrew informs us that the terms were used practically interchangeably: it was a mess.) When Geoffrey Elliott wrote about Tommy (‘Tar’) Robertson in Gentleman Spymaster, he was somewhat justified, because Robertson’s main claim to fame was the handling of the German double-agents in World War II. When Martin Pearce chose Spymaster for his biography of Maurice Oldfield, he had right on his side because Oldfield headed SIS, which is primarily an espionage organisation. Helen Fry used it for her profile of the SIS officer, Charles Kendrick, and Charles Whiting wrote a book titled Spymasters for his account of GCHQ’s manipulation of the Germans. But Liddell headed a counter-espionage and counter-intelligence unit: he was not a master of spies.

Second, the subject. Subtitled The Legacy of Guy Liddell, Deputy Director of MI5, the book ‘is intended to examine Liddell’s involvement in some important counter-espionage cases’. Thus some enticing-looking chapters appear on The Duke of Windsor, CORBY (Gouzenko), Klaus Fuchs, Konstantin Volkov (the would-be defector from Turkey who almost unveiled Philby), BARCLAY and CURZON (in fact, Burgess and Maclean, but why not name them so? : BARCLAY does not appear until the final page of a ninety-page chapter), PEACH (the codename given to the investigation of Philby from 1951), and Exposure. One might therefore look forward to a fresh analysis of some of the most intriguing cases of the post-war period.

Third, the sources. Like any decent self-respecting author of average vanity, the first thing I did on opening the book was to search for my name in the Acknowledgments or Sources. But no mention. I might have thought that my analysis, in Misdefending the Realm, of Liddell’s flaws in not taking the warnings of Krivitsky seriously enough, in not insisting on a follow-up to the hint of the ‘Imperial Council’ source, worthy of inclusion. I saw such characters as Tommy Robertson, Dick White, Anthony Blunt, John Cairncross, Yuri Modin and even Jürgen Kuczynski listed there, which did not fill my bosom with excitement, as I thought their contributions would have been exhausted and stale by now. The Bibliography is largely a familiar list of books of various repute, going back to the 1950s, with an occasional entry of something newer, such as the unavoidable and inevitable Ben Macintyre, from more recent years. It also, not very usefully, includes Richard Deacon’s British Connection, a volume that was withdrawn and pulped for legal reasons, and is thus not generally available So what was this all about?

It turns out that the content of the book is about 80% reproduction of public documents, either excerpts from Liddell’s Diaries from the time 1945 to his resignation in 1953, or from files available at the National Archives. (It is very difficult to distinguish quickly what is commentary and what is quoted sources, as all appear in the same typeface, with many excerpts continuing on for several pages, even though such citations are indented. And not all his authoritative statements are sourced.) The story West tells is not new, and can be largely gleaned from other places. Moreover, he offers very little fresh or penetrating analysis. Thus it appears that West, his project on publishing excerpts from the Diaries forced to a premature halt, decided to resuscitate the endeavour under a new cover.

So what is Liddell’s ‘legacy’? The author comes to the less than startling conclusion that ‘with the benefit of hindsight, access to recently declassified documents and a more relaxed attitude to the publication of memoirs [what does this mean? Ed.], we can now see how Liddell was betrayed by Burgess, Blunt and Philby.’ Is that news? And does West intend to imply that it was not Liddell’s fault? He offers no analysis of exactly how this happened, and it is a strain to pretend that Liddell, whose object in life was to guard against the threats from such lowlifes, somehow maintained his professional reputation while at the same time failing calamitously to protect himself or the Realm. What caused the fall from grace of ‘unquestionably one of the most remarkable and accomplished professionals of his generation’? Moreover, the exploration of such a betrayal could constitute a poignant counterpoint to the sometime fashionable notion – espoused by Lord Annan and others – that Goronwy Rees had been the greater sinner by betraying, through his criticisms of Burgess and Maclean in his People articles, the higher cause of friendship. Cold War Spymaster thus represents a massive opportunity missed, avoided, or perhaps deferred.

Expert, Administrator or Leader?

In Misdefending the Realm, my analysis of Liddell concluded that he was an essentially decent man who was not tough enough for the climate and position he was in. Maybe someone will soon attempt a proper biography of him, as he deserves. His earlier years with Special Branch and the formative years in the 1930s are not really significant, I think. West starts his Chronology with January 1940, when Krivitsky was interrogated, and I agree that that period (which coincides closely with the start of the period studied in Misdefending the Realm) is the appropriate place to begin.

I have always been puzzled by the treatment of Jane Archer, whom Liddell essentially started to move out at the end of 1939. Why he would want to banish his sharpest counter-espionage officer, and replace her with the second-rate Roger Hollis – not the move of a ‘remarkable and accomplished professional’ – is something that defies logic. Yet the circumstances of Archer’s demise are puzzling. We have it solely on Liddell’s word that Archer was fired, in November 1940, at Jasper Harker’s behest, because she had reputedly mocked the rather pompous Deputy Director-General once too much. (She did not leave the intelligence world, but moved to SIS, so her behaviour cannot have been that subversive. Incidentally, a scan of various memoranda and reports written by Harker, scattered around MI5 files, shows a rather shrewd and pragmatic intelligence officer: I suspect that he may have received a poor press.) I should not be surprised to discover that there was more going on: I am so disappointed that no one appears to have tried to interview this gallant woman before her death in 1982.

It would be naïve to imagine that MI5 would be different from any other organisation and be immune from the complications of office politics – and office romance. If I were writing a fictionalized account of this period, I would have Guy Liddell showing an interest in the highly personable, intelligent, humorous and attractive Jane Sissmore (as she was until September 1939). Liddell’s marriage had fallen on rocky ground: in Molehunt, Nigel West stated that his wife Calypso née Baring (the daughter of the third Baron Revelstoke) had left him before the start of the war. John Costello, in Mask of Treachery, related, having interviewed Liddell himself, that Calypso had absconded as early as 1938, and that Liddell had travelled to Miami in December of that year, and surprisingly won a successful custody battle. Yet contemporary newspapers prove that Calypso had left her husband, taking their children to Florida as early as July 1935, in the company of her half-brother, an association that raised some eyebrows as well as questions in court. Liddell followed them there, and was able, by the peculiarities of British Chancery Law, to make the children wards of court in August. In December, Calypso publicly called her husband ‘an unmitigated snob’ (something the Revelstokes would have known about, I imagine), but agreed to return to England with the offspring, at least temporarily. At the outbreak of war, however, Calypso had managed to overturn the decision because of the dangers of the Blitz, and eventually spirited their children away again. West informs us that, ‘for the first year of the war Liddell’s daughters lived with his widowed cousin Mary Wollaston in Winchester, and Peter at his prep school in Surrey, and then they moved to live with their mother in California’. (Advice to ambitious intelligence officers: do not marry a girl named ‘Calypso’ or ‘Clothilde’.)

The day before war broke out, Jane Sissmore married another MI5 officer, Joe Archer. In those days, it would have been civil service policy for a female employee getting married to have to resign for the sake of childbearing and home, but maybe the exigences of war encouraged a more tolerant approach. Perhaps the Archers even delayed their wedding for that reason. In any case, relationships in the office must have changed. There is not a shred of evidence behind my hypothesis that Liddell might have wooed Sissmore in the first part of 1939, but then there is not a shred of evidence that he maintained a contact in Soviet intelligence to whom he passed secrets, as has been the implication by such as Costello. Yet it would have been very strange if, his marriage irretrievably broken, he had been unappreciative of Sissmore’s qualities, and not perhaps sought a closer relationship with her. It might also explain why Liddell felt uncomfortable having Jane continue to work directly for him. Despite her solid performance on the Krivitsky case, she was appointed supremo of the Regional Security Liaison Officers organisation in April 1940. In this role she quickly gained respect from the hard-boiled intelligence officers, solicitors, stockbrokers and former King’s Messengers who worked for her, until she and Liddell in late October 1940 had another clash (as I reported in the Mystery of the Undetected Radios: Part 3). She was fired shortly after.

Liddell’s life was complicated by the insertion, in August 1940, of William Crocker as his co-director of B Division, at Lord Swinton’s insistence, and no doubt with the advice of Sir Joseph Ball. It is not clear what the exact sequence of events was, but Crocker, who was a solicitor, and Ball’s personal one to boot, had acted for Liddell in trying to maintain custody of the three children he had with Calypso. While the initial attempt had been successful, it was evidently overturned in 1939, and Liddell and his wife were legally separated in 1943. Crocker did not last long in MI5, and he resigned in September of 1940. While David Petrie brought some structure and discipline to the whole service by mid-1941, Liddell had buried himself in his work (and in the task of writing up his Diaries each night), and had found social company in circles that were not quite appropriate for his position. The personal stress in his life, alone and separated from his four children, must have been enormous.

Such contacts would come back to haunt Liddell. When Petrie retired from the Director-Generalship of MI5 in 1946, Liddell was overlooked as replacement, some accounts suggesting that a word in Attlee’s ear by the leftwing firebrand, ‘Red’ Ellen Wilkinson, had doomed his chances. The most recent description of this initiative appears in Michael Jago’s 2014 work, Clement Attlee: The Inevitable Prime Minister, where he describes Liddell’s rejection despite the support for him from within MI5. Wilkinson had apparently told her lover, Herbert Morrison, who was Home Secretary in the postwar Labour administration, that Liddell had in 1940 betrayed the communist propagandist Willi Münzenberg, who had entered Stalin’s hitlist and been assassinated in France.

Several aspects of such an assertion are extremely illogical, however. It is true that the suspicions that Attlee and his ministers had about the anti-socialist tendencies of MI5 coloured the Prime Minister’s perspectives on security matters, but this narrative does not bear up to examination. First, for a leftist agitator like Wilkinson (who had also been the lover of Münzenberg’s henchman, Otto Katz) to confirm her close association with Münzenberg, and take up Münzenberg’s cause against Stalin, was quixotic, to say the least, even if her convictions about the communist cause had softened. Second, for her to believe that the democratically-minded Attlee would look upon Münzenberg’s demise as a cause for outrage reflected a serious misjudgment. He would not have been surprised that MI5, and Liddell in particular, would have taken such a stance against Communist subversion, especially when he (Attlee) learned about the activities of the Comintern a decade before. Third, for Wilkinson to think that Attlee could be persuaded that Liddell had abetted the NKVD in eliminating Münzenberg, showed some remarkable imagination. Fourth, if Attlee had really listened carefully to her, and found her arguments persuasive, he would hardly have allowed Liddell to continue on in MI5 without even an investigation, and to be promoted to Deputy Director-General as some kind of designate. (Churchill was back in power when Sillitoe resigned.) Thus Wilkinson’s personification of Liddell as an agent of Stalinism has the ring of black comedy.

I have discussed this with the very congenial Mr. Jago, who, it turns out, was at Oxford University at exactly the same time as I, and like me, relocated to the USA in 1980. (We worked out that we must have played cricket against each other in opposing school teams in 1958.) He identifies his source for the Wilkinson anecdote as that figure with whom readers of this column are now very familiar, the rather problematical Richard Deacon. Indeed, in The Greatest Treason, Deacon outlined Wilkinson’s machinations behind the scenes, attributing her reservations about Liddell to what Münzenberg had personally told her about his ‘enemy in British counter-espionage’ before he was killed. Deacon had first introduced this theory in his 1982 memoir With My Little Eye, attributing the source of the story to the suffragette Lady Rhondda, who had apparently written to Deacon about the matter before she died in 1958, also suggesting that Liddell ‘was trying to trap Arthur Koestler’. Yet Deacon qualified his report in The Greatest Treason: “Whether Ellen Wilkinson linked the Münzenberg comments with Guy Liddell is not clear, but she certainly remembered Münzenberg’s warning and as a result expressed her doubts about him. Morrison concurred and it was then that Attlee decided to bring an outsider in as chief of MI5.” I rest my case: in 1940, with Nazi Germany an ally of Soviet Russia, Liddell should have done all he could to stifle such menaces as Münzenberg. Of course Münzenberg would have ‘an enemy in MI5’. I cannot see Attlee falling for it, and this particular urban legend should be buried until stronger independent evidence emerges.

The rumour probably first appeared in David Mure’s extraordinary Last Temptation, a faux memoir in which he uses the Guy/Alice Liddell connection to concoct a veiled dramatization of Liddell’s life and career. This work, published in 1980, which I have analysed in depth in Misdefending the Realm, exploits a parade of characters from Alice in Wonderland to depict the intrigues of MI5 and MI6, and specifically the transgressions of Guy Liddell. If anyone comes to write a proper biography of Liddell, that person will have to unravel the clues that Mure left behind in this ‘novel of treason’ in order to determine what Mure’s sources were, and how reliable they were. Mure describes his informant for the Ellen Wilkinson story as an old friend of Liddell’s mother’s, ‘the widow of a food controller in the First World War’, which does not quite fit the profile of Sir Humphrey Mackworth, whom Viscountess Rhondda had divorced in 1922. A task for some researcher: to discover whether Mure and Deacon shared the same source, and what that person’s relationship with Ellen Wilkinson was.

Regardless of these intrigues, Nigel West suggested, in A Matter of Trust, his history of MI5 between 1945 and 1972, quite reasonably that an ‘insider’ appointment would have been impossible in the political climate of 1945-1946, what with a rampant Labour Party in power, harbouring resentment about the role that MI5 had played in anti-socialist endeavours going back to the Zinoviev Letter incident of 1924. Yet West, while choosing to list some of Liddell’s drawbacks (see below) at this stage of the narrative, still judged that Liddell could well have been selected for the post had Churchill won the election. The fact was that Churchill returned, and Liddell again lost.

Another Chance

When Sillitoe’s time was over in 1953, Liddell still considered himself a candidate for Director-General, and faced the Appointments Board in the Cabinet Office on April 14. (West reproduces his Diary entry from that evening.) It appears that our hero had not prepared himself well for the ordeal. Perhaps he should have been alarmed that a selection process was under way, rather than a simple appointment, and that one of his subordinates was also being encouraged to present himself. When the Chairman, Sir Edward Bridges, asked him what qualifications he thought were appropriate for the directorship, Liddell recorded: “I said while this was a little difficult to answer, I felt strongly somebody was need who had a fairly intimate knowledge of the workings of the machine.” That was the tentative response of an Administrator, not a Leader. Later: “Bridges asked me at the end whether I had any other points which had not been covered, and on reflection I rather regret that I did not say something about the morale of the staff and the importance of making people feel that it was possible for them to rise to the top.” He regretted not saying other things, but his half hour was up. He had blown his opportunity to impress.

Even his latest sally probably misread how his officers thought. Few of them nursed such ambitions, I imagine, but no doubt wanted some better reward for doing a job they loved well. For example, Michael Jago (the same) in his biography of John Bingham, The Spy Who Was George Smiley, relates how Maxwell Knight tried to convince Bingham to replace him as head of the agent-runners. Jago writes: “He strenuously resisted promotion, pointing out that his skills lay as an agent runner, not as a manager of agent runners. The administrative nature of such a job did not appeal to him; his agents were loyal to him and he reciprocated that loyalty.” This is the dilemma of the Expert that can be found in any business, and is one I encountered myself: should he or she take on managerial duties in order to gain promotion and higher pay, or can the mature expert, with his specialist skills more usefully employed, enjoy the same status as those elevated to management roles?

Liddell was devastated when he did not get the job, especially since his underling, Dick White, whom he had trained, was indeed appointed, thus contradicting the fact of White’s ‘despondent’ mood after his interview, which he had communicated to Liddell. The authorised historian of MI5, Christopher Andrew, reported the judgment of the selection committee, which acknowledged that Liddell had ‘unrivalled experience of the type of intelligence dealt with in MI5, knowledge of contemporary Communist mentality and tactics and an intuitive capacity to handle the difficult problems involved’. But ‘It has been said [‘by whom?’: coldspur] that he is not a good organiser and lacks forcefulness. And doubts have been expressed as to whether he would be successful in dealing with Ministers, with heads of department and with delegates of other countries.’ This was a rather damning – though bureaucratically anonymous – indictment, which classified Liddell as not only an unsuitable Leader, but as a poor Administrator/Manager as well, which would tend to belie the claim that he had much support from within MI5’s ranks.

(Incidentally, Andrew’s chronology is at fault: he bizarrely has Liddell retiring in 1952, White replacing him as Deputy Director-General and then jousting with Sillitoe, before the above-described interviews in May 1953. The introduction to the Diaries on the National Archives repeats the error of Liddell’s ‘finally retiring’ in 1952. West repeats this mistake on p 185 of A Matter of Trust, as well as in Molehunt, on pp 35-36, but corrects it in the latter on p 123. Tom Bower presents exactly the same self-contradiction in his 1995 The Perfect English Spy. West’s ODNB entry for Liddell states that “ . . . , in 1953, embarrassed by the defection of his friend Guy Burgess, he took early retirement to become security officer to the Atomic Energy Authority”, thus completely ignoring the competition for promotion. It is a puzzling and alarming pattern, as if all authors had been reading off the same faulty press release, one that attempted to conceal Liddell’s embarrassing finale. In his 2005 Introduction to the published Diaries, West likewise presents the date of Liddell’s retirement correctly, but does not discuss his failed interview with the Appointments Board. The Introduction otherwise serves as an excellent survey of the counter-intelligence dynamics of the Liddell period, and their aftermath.)

Liddell’s being overlooked in 1946 cannot have helped his cause, either. West wrote, of the competition for D-G that year, that Liddell’s intelligence and war record had been ‘exceptional’, and continued: “He was without question a brilliant intelligence officer, and he had recruited a number of outstanding brains into the office during his first twelve months of the war. But he had a regrettable choice in friends and was known to prefer the company of homosexuals, although he himself was not one. [This was written in 1982!] Long after the war he invariably spent Friday evenings at the Chelsea Palace, a well-known haunt of homosexuals.” West updated his account for 1953, stating that Liddell ‘might have at first glance have seemed the most likely candidate for the post, but he had already been passed over by Attlee and was known to have counted Anthony Blunt and Guy Burgess amongst his friends.’ In the light of Burgess’s recent decampment with Maclean, that observation strikes an inappropriate chord, as if Burgess’s homosexuality rather than his involvement in Soviet espionage had been the aspect that tarnished Liddell’s judgment, and that Liddell’s now recognized professional failings were somehow not relevant. After all, Burgess’s homosexuality was known to every government officer who ever recruited him.

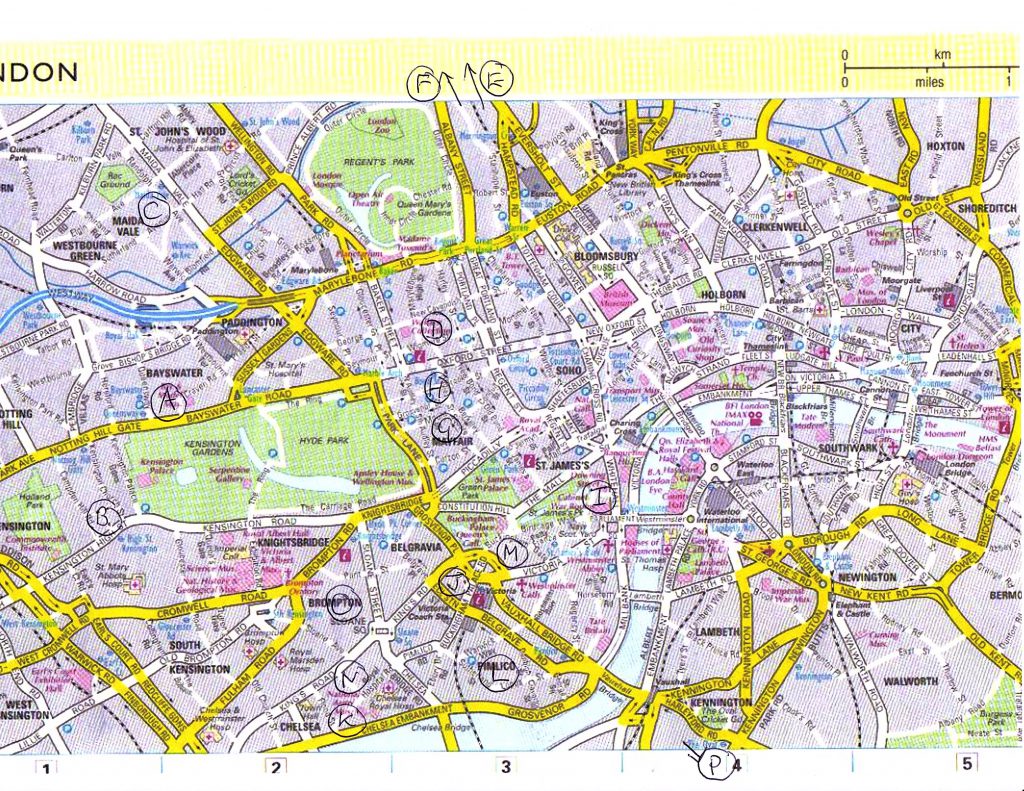

Moreover, if associating with the Bentinck Street crowd that assembled at Victor Rothschild’s place cast a cloud over Liddell’s reputation, Dick White may have been as much at fault as was Liddell. It is somewhat difficult to find hard evidence of how close the associations at the Rothschild flat were, and exactly what went on. Certainly, Rothschild rented it to Guy Burgess and Anthony Blunt. Goronwy Rees’ posthumous evidence, as retold by Andrew Boyle, was melodramatic. The Observer article of Sunday, January 20, 1980 was titled ‘The Brotherhood of Bentinck Street’, with Rees explaining how ‘Burgess and Blunt entangled top MI5 man Guy Liddell in their treachery’. Rees went on to say that Liddell was one of Burgess’s ‘predatory conquests’, and that Burgess’s ‘main source’ must have been Liddell. Rees certainly overstated the degree of sordidness that could be discovered there. White, meanwhile, still a bachelor, was reported, according to his biographer, Tom Bower, to attend wartime parties in Chesterfield Street, Mayfair, hosted by Tomas ‘Tommy’ Harris, where he mixed with such as Blunt, Philby, Burgess, Rothschild, Rees and Liddell himself. White, however, was not a ‘confirmed bachelor’ and married the communist novelist Kate Bellamy in November 1945.

Yet none of this would have been known about in 1953, or, if it had, would have been considered quite harmless. After all, the top brass in Whitehall was unaware at this time of Blunt’s treachery (although I contend that White and Liddell, and maybe Petrie, knew about it), and Burgess had mixed and worked with all manner of prominent persons – all of whom rapidly tried to distance themselves from any possible contamination by the renegade and rake. Moreover, Liddell had not recruited Burgess to MI5, even though he had wanted to, but been talked out of it by John Curry. John Costello, in his multipage assault on Liddell in Mask of Treachery, lists a number of ‘errors’ in Liddell’s behavior that raise ‘serious questions about Liddell’s competency, bad luck, or treachery’, but most of these would not have been known by the members of the Appointments Board, and the obvious mistakes (such as oversights in vetting for Klaus Fuchs) were not the responsibility of Liddell alone. He simply was not strong enough to have acted independently in protecting such persons.

Thus it is safe to assume that Liddell was rightly overlooked in 1953 because he was not leadership material, not because of his questionable associations. White was, on the other hand, a smoother operator. He had enjoyed a more enterprising career, having been posted to SHAEF at the end of 1944, and spent the best part of eighteen months in counter-intelligence in Germany, under General Eisenhower and Major-General Kenneth Strong, before touring the Commonwealth. (Strong was in fact another candidate for the MI5 leadership: White told his biographer that he noted Strong’s lack of interest in non-military intelligence.) He knew how to handle the mandarins, and sold himself well. As Bower wrote, in his biography of White, The Perfect English Spy: “The qualities required of an intelligence chief were evident: balance, clarity, judgment, credibility, honesty, cool management in the face of crisis, and the ability to convey to his political superiors in a relaxed manner the facts which demonstrated the importance of intelligence.” Malcolm Muggeridge was less impressed: “Dear old Dick White”, he said to Andrew Boyle, “‘the schoolmaster’. I just can’t believe it.”

White was thus able to bury the embarrassments of two years before, when he and Liddell had convinced Sillitoe to lie to Premier Attlee over the Fuchs fiasco, and he had also somehow persuaded the Appointments Committee that he was not to blame for the Burgess/Maclean disaster. This was an astounding performance, as only eighteen months earlier, in a very detailed memorandum, White had called for the Philby inquiry to be called off, only to face a strong criticism from Sir William Strang, the permanent under-secretary at the Foreign Office since 1949, who was also on the Selection Committee. Yet White had previously clashed with Strang when the latter held back secret personal files. They shared similar convictions of misplaced institutional loyalty: Strang could not believe that there could be spies in the Diplomatic Service, while White refused to accept that there could be such among the officers of the intelligence corps.

White had also benefitted from Liddell’s promotion. He had returned from abroad in early 1946, and had been appointed head of B Division, since Liddell had been promoted to Deputy Director-General under Sillitoe, with Harker pushed into early retirement. Thus White took over centre-stage as the Cold War intensified, and was in obvious control of the meetings about Fuchs (1949-50), and then Burgess and Maclean (1951), with Liddell left somewhat out of the main picture. White was then able to manipulate the mandarins to suggest that the obvious mistakes had either not occurred on his watch, or had else been unavoidable, while Liddell was left in a relatively powerless no-man’s-land. It would appear that White out-manoeuvred his boss: how genuine was his display of ‘despondency’ to Liddell after the interview, one wonders?

White was probably also a better Leader than a Manager. He was somewhat bland, and smoothness was well-received in Whitehall: he had the annoying habit of agreeing with the last person who made a case to him – a feature that I came across frequently in business. There can be nothing more annoying than going in to see a senior manager, and making a well-prepared argument, and see a head nodding vigorously the other side of the desk, with its owner not challenging any of your conclusions or recommendations. Yet nothing happens, because the next person who has won an audience may put forward a completely different set of ideas, and still gain the nodding head. That is a sign of lack of backbone. R. A. (later Lord) Butler ascribed the same deficiency to his boss, Lord Halifax, and Franklin Roosevelt was said to exhibit the same tendency, preferring to manipulate people through his personal agencies and contacts, and commit little in writing. But White dealt well with the politicians, who considered him a ‘safe pair of hands’, and his career thrived after that.

Re-Assessing Liddell

When Kim Philby was being investigated as the possible ‘Third Man’ in the latter part of 1951, George Carey-Foster, the Security Officer in the Foreign Office, wrote to Dick White about their suspect’s possible escape: “Are you at any stage proposing to warn the ports, because even that may leak and bring in the Foreign Office? For these reasons as well as for those referred to in my previous letter I think we ought to know how we are to act before we are overtaken by events.” That was one of the main failings of Liddell’s that I identified in Misdefending the Realm: “Liddell was very reactive: he did not appear to prepare his team for any eventuality that came along” (p 284). How should MI5 respond if its recommendations over vetting were overruled? What policies were in place should a defector like Gouzenko or Volkov turn up? How should MI5 proceed if it came about that one of its officers was indeed a Soviet spy, yet the evidence came through secret channels? Who should conduct interrogations? Under what circumstances could a prosecution take place? There was no procedure in place. Events were allowed to overtake MI5.

The task of a regular counter-espionage officer was quite straightforward. It required some native intelligence, patience and attention to detail, stubbornness, curiosity, empathy, a knowledge of law and psychology, unflappability (the attributes of George Smiley, in fact). As it happens, I compiled this list before reading how Vernon Kell, the first Director of MI5 had described the ideal characteristics of a Defence Security Officer: ‘Freedom from strong personal or political prejudices or interest; an accurate and sympathetic judgment of human character, motives and psychology, and of the relative significance, importance and urgency of current events and duties in their bearing on major British interests’. They still make sense. Yet, if an officer performed his job of surveillance industriously, and identified a subversive, not much more could be recommended than ‘keeping an eye on him (or her)’. MI5 had no powers of arrest, so it just had to wait until the suspect was caught red-handed planting the bomb in the factory or handing over the papers before Special Branch could be called in. That process would sometimes require handling ‘agents’ who would penetrate such institutions as the Communist Party HQ, for example Olga Gray and her work leading to the capture and prosecution of Percy Glading. That was a function that Maxwell Knight was excellent at handling.

With the various ‘illegals’ and other aliens floating around, however, officers were often left powerless. They had to deal with busybody politicians interfering in immigration bans and detention orders, civil servant poohbahs overriding recommendations on non-employment, cautious ministers worried about the unions, inefficient security processes at sea- and air-ports, leaders cowed by their political masters, Foreign Office diplomats nervous about upsetting Uncle Joe Stalin in the cause of ‘cooperation’, or simple laziness and inattention in other departments – even absurd personnel policies. Thus Brandes and Maly and Pieck were allowed to escape the country, Krivitsky’s hints were allowed to fade away, Fuchs was recruited by Tube Alloys, and Burgess and Maclean were not fired from their positions in the Foreign Office but instead moved around or given sick leave, and then allowed to escape as the interrogation process ground into motion. These were problems of management and of leadership.

If a new manager asks his or her boss: “What do I have to do to perform a good job?”, and the boss responds: “Keep out of trouble, don’t rock the boat, and send your status reports in on time”, the manager will wisely not ruffle feathers, but concentrate on good recruitment, training, and skills development, following the procedures, and getting the job done. The problem will however arise that, after a while when the ship is running smoothly, the manager may be seen as superfluous to requirements, while his or her technical skills may have fallen by the wayside. That may lead to a loss of job (in the competitive commercial world anyway: probably not in government institutions.) If, however, the boss says: “I want you to reshape this unit, and set a few things on fire”, the candidate may have to develop some sharp elbows, lead some perhaps reluctant underlings into an uncertain future, and probably upset other departments along the way. That implies taking risks, putting one’s head above the parapet, and maybe getting metaphorically shot at. In a very political organisation – especially where one’s mentor/boss may not be very secure – that rough-and-tumble could be equally disastrous for a career. I am familiar with both of these situations from experience.

So where does that leave ‘probably the single most influential British intelligence officer of his era’ (West)? We have to evaluate him in terms of the various roles expected of him. He was indubitably a smart and intelligent man, imaginative and insightful. But what were his achievements, again following what West lists? ‘His knowledge of Communist influence dated back to the Sidney Street siege of January 1911’ – but that did not stop him recruiting Anthony Blunt, and allowing Communists to be inserted into important positions during his watch. ‘He had been on the scene when the Arcos headquarters in Moorgate had been raided’, but that operation was something of a shambles. ‘He had personally debriefed the GRU illegal rezident Walter Krivitsky in January 1940’, but that had been only an occasional involvement, he stifled Jane Archer’s enterprise, and he did not put in place a methodological follow-up. ‘He was the genius behind the introduction of the now famous wartime Double Cross system which effectively took control of the enemy’s networks in Great Britain’, but that was a claim that White also made, the effort was managed by ‘Tar’ Robertson, and the skill of its execution is now seriously in question. As indicated above, West alludes to Liddell’s rapid recruitment of ‘brains’ in 1940, but Liddell failed to provide the structure or training to make the most of them. These ‘achievements’ are more ‘experiences’: Liddell’s Diaries contain many instances of decisions being made, but it is not clear that they had his personal stamp on them.

Regrettably, the cause of accuracy is not furthered by West’s entry for Liddell in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Again, vaguely referring to his subject’s ‘supervision’ of projects, and ‘key role’ in recruiting such as White and Blunt, West goes on to make the following extraordinary claim: “Thus Liddell was closely associated with two of MI5’s most spectacular accomplishments, the interception and decryption of German intelligence signals by the Radio Security Service, and the famed ‘double cross system’. The Radio Security Service had grown, under Liddell’s supervision, from an inter-service liaison committee known as the Wireless Board into a sophisticated cryptographic organisation that operated in tandem with Bletchley Park, concentrating on Abwehr communications, and enabling MI5 case officers to monitor the progress made by their double agents through the reports submitted by their enemy controllers to Berlin.” Yet this is a travesty of what occurred. As I showed in an earlier posting, the Radio Security Service (RSS) was a separate unit, part of MI8. MI5 rejected taking it over, with the result that it found its home within SIS. It had nothing organisationally to do with the Wireless Board, which was a cross-departmental group, set up in January 1941, that supervised the work of the XX Committee. RSS was an interception service, not a cryptological one. It was the lack of any MI5 control that partly contributed to what historian John Curry called the eventual ‘tragedy’. Thus West founds a large part of what he characterizes as a ‘remarkable’ career on a misunderstanding: Liddell’s lifework was one dominated by missed opportunities.

Moreover, West cites one of his sources for his bibliographic entry on Liddell as Richard Deacon’s Greatest Treason. This seems to me an error of judgment on at least three counts, and raises some serious questions of scholarship. While Deacon’s work contains the most complete account of Liddell’s earlier life, it is largely a potboiler, having as its central thesis the claim that Liddell was an agent of Soviet espionage, and may even have been the elusive ELLI over whose identity many commentators have puzzled. (The lesser-known subtitle of Deacon’s book is The Bizarre Story of Hollis, Liddell and Mountbatten.) Yet this is a position with which West is clearly not in sympathy, as is shown by his repeated encomia to Liddell’s performance. The Editors at the ODNB should have shown much more caution in allowing such a book to be listed as an authoritative source without qualification. Lastly, a fact that Deacon did not acknowledge when his book was published in 1989, West had himself been a researcher for Richard Deacon, as West explains in a short chapter in Hayek: A Collaborative Biography, edited by Robert Leeson, and published in 2018. Here he declares that Deacon was ‘exceptionally well-informed’, but he finesses the controversy over Liddell completely. Somewhere, he should have explained in more detail what lay behind his research role, and surely should have done more to clarify how his source contributed to his summarization of Liddell’s life, and why and where he, West, diverged from Deacon’s conclusions.

Something else with which West does not deal is Liddell’s supposed relationship with one of the first women members of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Joyce Whyte. David Mure, in The Last Temptation, had hinted at this lady’s identity, but not named her, giving her the codename ‘Alice’. In With My Little Eye, however, Richard Deacon went much further, providing us with the following insight (which can be found in a pagenote on p 194 of Misdefending the Realm): “In the early 1920s, when Liddell was working at Scotland Yard, supposed to be keeping a watch on communists, his mistress was Miss Joyce Wallace Whyte of Trinity College, Cambridge, and at that time one of the first women members of the Cambridge Communist Party. In 1927 she married Sir Cuthbert Ackroyd, who later became Lord Mayor of London.” For what it is worth, Deacon has Whyte’s family living in Chislehurst, Kent: Mure indicates that the influential lady lived nearby, in Sidcup.

It is not as if Liddell were outshone by his colleagues, however. To an extent, he was unlucky: unfortunate that there was another ‘able’ candidate available in White when a preference for an insider existed, and perhaps unfairly done by, from a historical standpoint, when the even less impressive Hollis succeeded White later. A survey of other candidates and successes does not depict a parade of standouts. Jasper Harker was regarded by all (maybe unjustly) as ineffectual, but was allowed to languish as Deputy Director-General for years. Dick White was not intellectually sharper than Liddell, but was likewise impressionable, and equally bamboozled. He managed the politics better, however, had broader experience, and was more decisive. Hollis was certainly less distinguished than Liddell in every way. Petrie was an excellent administrator, and occasionally showed signs of imaginative leadership, sharpening up MI5’s mission, but he was not a career intelligence officer. Sillitoe did not earn the respect of his subordinates, and had a hazy idea of what counter-intelligence was. Liddell’s equivalent in SIS, Valentine Vivian, comes across as something of a buffoon, clueless about the tasks that were confronting him, and how he should go about them, and Vivian’s arch-enemy within SIS, Claude Dansey (whose highly unusual behavior may perhaps be partially explained by his being involved, in 1893, in a scandalous affair with Oscar Wilde, Lord Alfred Douglas, and Robbie Ross), was regarded as poisonous by most who encountered him. Kim Philby outwitted them all. (If his head had been screwed on the right way, he would have made an excellent Director-General.) So, with a track-record of being only a mediocre man-manager, it should come as no surprise that the very decent and intellectually curious Liddell should have been rejected for the task of leading Britain’s Security Service. The tragedy was that MI5 had no process for identifying and developing interior talent.

When Liddell resigned, he was appointed security adviser to the Atomic Energy Commission, an irony in that AERE Harwell was the place where Fuchs had worked until his investigation by Henry Arnold, the adviser at the time. The introduction to Liddell’s Diaries at the National Archives suggests that he was in fact quite fortunate to gain this post, considering his links to Burgess, Rothschild and Philby. (The inclusion of Rothschild in these dubious links is quite impish on the behalf of the authorities.) Liddell died five years later. The verdict on him should be that he was an honest, intelligent and imaginative officer who did not have the guts or insight to come to grips with the real challenges of ‘Defending the Realm’, or to promote a vision of his own. He was betrayed – by Calypso, by Blunt, Burgess and Philby, by White, and maybe by Petrie. In a way, he was betrayed by his bosses, who did not give him the guidance or tutoring for him to execute a stronger mandate. But he was also soft – and thus open to manipulation. Not a real leader of men, nor an effective manager. By no means a ‘Spymaster’, but certainly not a Soviet supermole either.

What it boils down to is that, as with so many of these intelligence matters, you cannot trust the authorised histories. You cannot trust the memoirists. You cannot trust the experts. You cannot always trust the archives. And you cannot even trust the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, which is sometimes less reliable than Wikipedia. All you can trust is coldspur, whose ‘relentless curiosity and Smileyesque doggedness blow away the clouds of obfuscation that bedevil the world of intelligence’ [Clive James, attrib.].

In summary, we are left with the following paradoxical chain of events:

- During the 1970s and 1980s, Nigel West performs research for Richard Deacon.

- In 1987, West publishes Molehunt, where he describes Liddell as ‘a brilliantly intuitive intelligence officer’.

- In 1989, Deacon publishes The Greatest Treason, which claims Guy Liddell was a Soviet mole.

- In 2004, West writes a biographical entry for Liddell in the ODNB, which praises him, but carelessly misrepresents his achievements, and lists The Greatest Treason as one of the few sources.

- In 2005, West edits the Liddell Diaries, and provides a glowing Introduction for his subject.

- In 2015, West provides a chapter to a book on Hayek, praises Deacon for his knowledge, but debunks him for relying on two dubious sources. He does not mention Liddell.

- In 2018, West writes a new book on Liddell, which generally endorses the writer’s previous positive opinion of him, but rejects the opportunity to provide a re-assessment of Liddell’s career, merely concluding that Liddell, despite being’ the consummate professional’, had been ‘betrayed’ by Burgess, Blunt and Philby. West lists in his bibliography two other books by Deacon (including the pulped British Connection), but ignores The Greatest Treason.

So, Nigel, my friend, where do you stand? Why would you claim, on the one hand, that Liddell was a brilliant counter-espionage officer while on the other pointing your readers towards Richard Deacon, who thought he was a communist mole? What do you say next?

This month’s Commonplace entries can be found here.