This is a B (Businesslike) report, with occasional pretensions to A (Advanced). I believe that it constitutes an innovative exposé of a couple of Soviet agents whose names have been largely concealed from the public eye. The saga really lends itself to being transformed into a TV drama, with the trimmings of espionage, subterfuge, sexual rivalry, betrayal and conspiracy, all of which (especially since they are true) should contribute to box-office success. Be patient, and don’t try to take it all in at once.

Contents:

Introduction: Astbury and Simon

Earlier Published Material

The Archives: Astbury

The Mysterious Long Interrogation

Investigating Blunt: the Simon Affair

The Wright Era

The Rothschilds

Conclusions

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction: Astbury and Simon

Astbury, Simon, Long and Blunt. Not a rock-group like Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, but a band of some import, nevertheless. Peter Astbury and Brian Simon are perhaps the equivalent of the Crosby and Stills duo, not so well-known as the other two. Simon seems on the surface to be only a marginal player in this drama, but may be a dark horse. On the other hand, where is Peter Astbury?

I pose the question ‘Where is Peter Astbury?’ rather than ‘Who is Peter Astbury?’. A quick search on Google will bring up a collection of facts about the Cambridge scientist and communist, but the more interesting question is ‘Why does he not appear in any of the usual places?’. For Astbury, through authorized but clandestine surveillance, was detected in passing on secrets to the Soviets, and he is thus one of the unheralded members of the extended Cambridge Ring. In an era of molehunting and spycatching one would expect him to have been highlighted by now. Christopher Andrew’s Defend the Realm has no mention of him; Peter Wright, who certainly knew of him from his interviews with Blunt and Rothschild, does not discuss him in Spycatcher; his name is not to be found in The Mitrokhin Archive (but then neither does that of Alan Nunn May or Bruce Pontecorvo); that renowned unmasker of imagined traitors Chapman Pincher has no room for Astbury in Treachery; I do not believe that Nigel West ever mentions him in any of his two dozen or so books, including his Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence. It seems that all were so entranced by the notion of a supermole in MI5 that they forgot about the (relatively) small fry.

The National Archives released Astbury’s Personal Files back in 2008 (KV 2/2884-2886), so there should have been some response by now. The rubric describing them reads as follows: “Peter ASTBURY studied at Cambridge 1935-38, joined the Communist Party in 1936, and was a member of the Apostles. Enlisted in the army in 1940, coverage of Party Headquarters in connection with the SPRINGHALL case showed ASTBURY to be passing information to SPRINGHALL knowing he was working for the Russians. When questioned in December 1943 ASTBURY lied. He worked for Professor BLACKETT at Manchester University on atomic energy, and researched cosmic rays at the Jungfrau High Altitude Laboratory in Switzerland.” Ignoring the unrelated participle (‘coverage’ was not ‘enlisted’), I observe that this description contains many provocative keywords: ‘Cambridge’, ‘Communist Party’, ‘Apostles’, ‘Springhall’, ‘Russians’, ‘Blackett’, ‘atomic energy’, and ‘cosmic rays’. One might have expected him to have been picked up by the molewatchers.

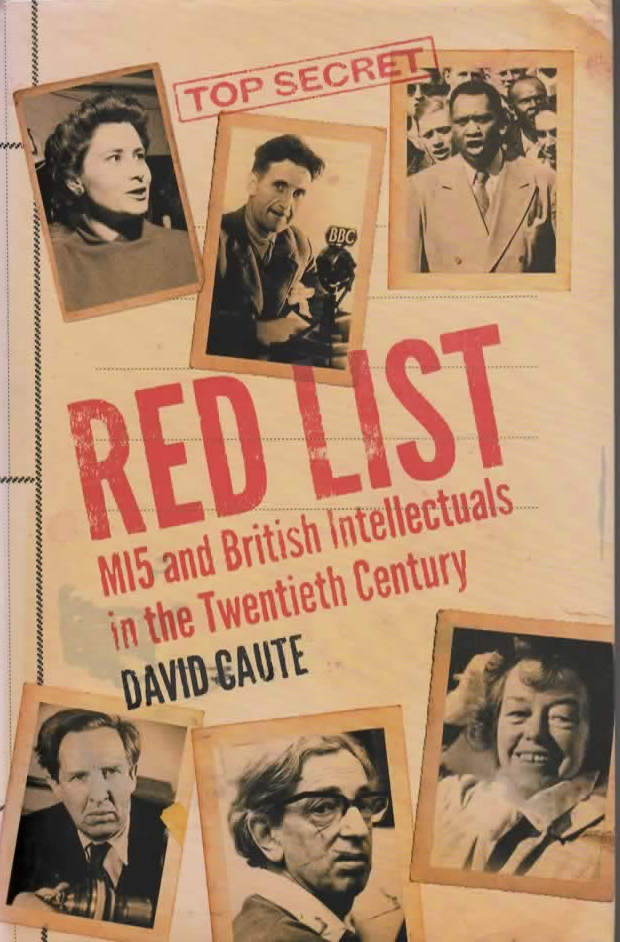

In fact, David Caute, in his Red List (2022), devotes three pages (222-225) to a useful précis of Astbury’s files, although it reflects no integrative analysis of material about him from elsewhere. And Daniel Lomas, in his new (and very expensive) Secret History of British Security Vetting from 1909 to the Present Day, offers a few sentences about this scientist’s dubious career. Those works are, I believe, the only two to have taken advantage of the Astbury Personal Files at Kew. Yet Astbury is mentioned in other relevant files at the National Archives, and I have been able also to gain some useful – though not always accurate – nuggets from sources published before 2008. That aspect is part of the enjoyment of the chase: determining how those stories evolved, investigating why mis- or dis-information was planted on the unsuspecting authors, and examining why other writers have ignored or overlooked their evidence.

The main issue is this: Astbury was determined to have been spying for the Soviets in 1943. Why was this fact hushed up?

Part of the reason, I suspect, is the fact that Astbury was tightly linked to another Communist, Brian Simon, who had friends in high places. The rubric for Simon’s voluminous Personal File (KV 2/4175-4184) runs as follows: “While at Cambridge University in the 1930s SIMON was active in student communist affairs. In 1935 he visited the USSR. After army service he resumed open communist activity and party committee work. During the 1950s and 1960s SIMON was one of the Communist Party’s leading intellectuals concentrating on educational affairs. He was also a major donor to Communist Party funds.” Simon was accompanied on that visit to the Soviet Union by Anthony Blunt, and he had some closer associations with his more famous mentor that shed light on the case. Astbury and Simon enjoyed a provocative wartime association, moreover, and they both appear in a curious episode concerning Blunt and Leo Long that is laid out in Blunt’s own Personal Files. Simon’s files were released in 2015: I regret that I have not yet had an opportunity to inspect them.* All four of the books listed above fail to make any mention of Brian Simon.

[* As can be seen, there are ten files – quite a substantial photographic project, with maybe little reward. I am hoping that my London-based researcher, Dr. Kevin Jones, will soon be able to browse them to search for nuggets. I doubt whether I shall have time to inspect them when I am in the UK in September.]

Caute’s Red List manages to summarize the ten-volume Personal File into a couple of pages, in which the author highlights Simon’s career as a communist rabble-rouser: school attendance at that hotbed of leftist ideas, Gresham’s; admittance to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1934; a visit to the Soviet Union with Blunt, Michael Straight and others in 1935; campaigning for the CPGB in the Rhondda Valley; membership of a communist cell at Catterick during the war, alongside Astbury; and vigorous promotion of Marxist ideas in the educational world thereafter. Moreover he married a Communist wife, who earned her own set of MI5 files under the name Joan Home Peel. Simon remained a member of the CPGB well into the 1960s.

Earlier Published Material

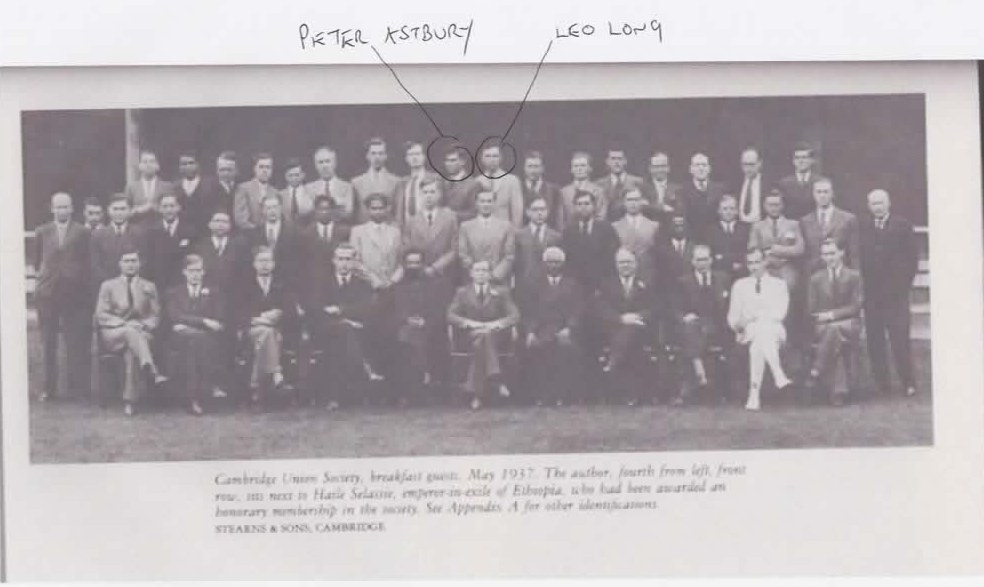

So what had been generally available about these two before their files were released? I believe the first mention was by Michael Straight.

Michael Straight’s After Long Silence (1983)

Straight was an American whom Blunt had recruited when he was at Cambridge, and Straight’s recognition, early in 1963, that he had to come clean, and admit to the FBI his time as a Soviet agent, led to the unmasking of Blunt himself. Straight revealed that, in the summer of 1935, he had been a member of a party that travelled to the Soviet Union, some of his ‘fellow-travellers’ being Blunt and Brian Simon. Apart from their devotion to Communism, Straight and Simon had another passion – ‘a student of unearthly beauty’, named Teresa Mayor. Straight tried in vain to seduce her, but Simon was apparently successful (although Straight does not declare that fact here). What should be noted is that Miss Mayor later became the second wife of Victor, Lord Rothschild, after working for him in MI5 during the war. The fact that Guy Burgess was also involved with Straight at the time is shown by a visit that Blunt, Simon and Burgess made to Dartington Hall (the Straight pile in Devon) in April 1937.

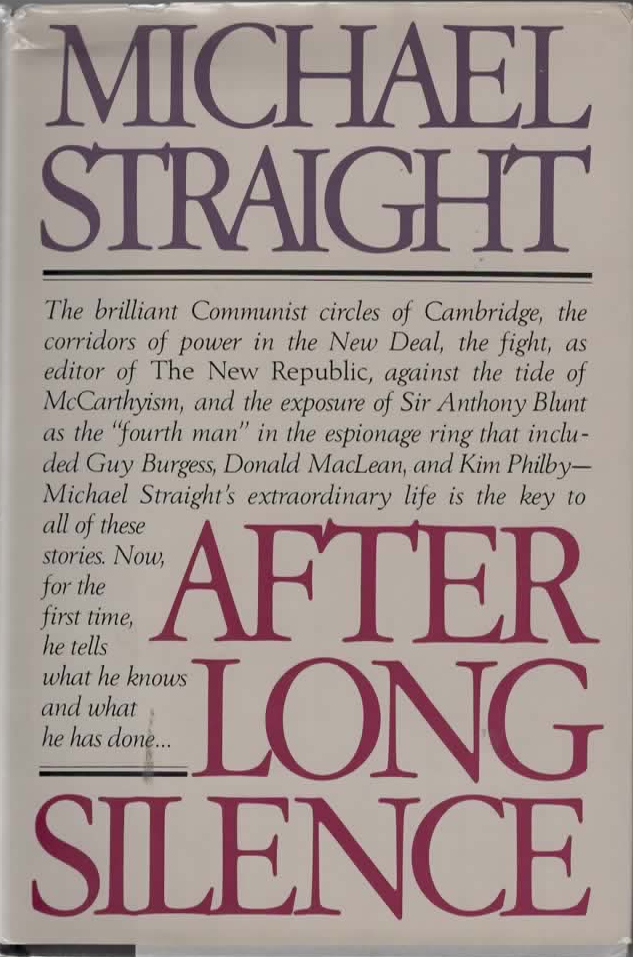

That summer, another important event occurred. The Emperor Haile Selassie of Abyssinia was given an honorary membership by the Cambridge Union, and a party was held at the Rothschild residence at Merton Hall. Straight provides a photograph of the occasion, in which he sits on the Emperor’s right. In the back row can be seen a member of the Apostles, Peter Astbury, standing next to another recent (or imminent) recruit, Leo Long. I can recall how undergraduates would be drawn to sit or stand next to their friends on such occasions: Astbury is, rather enigmatically, looking away from Long and the camera, but cannot escape the inevitable historical record. Three years later, when Straight met Guy Burgess in Washington after the latter’s aborted trip to Moscow with Isaiah Berlin, Burgess told him that Blunt had recruited Long to the Apostles, and Straight assumed, therefore, that Blunt must have brought his latest protégé into the Soviet cause. When Straight was interviewed by MI5’s Arthur Martin in January 1964 (actually late February), in Washington, Martin asked him if he could name anyone else who had been recruited by Burgess and Blunt. Straight expressed his thoughts about Leo Long, whereupon Martin apparently let out a deep sigh, and indicated that that was the first hard evidence that the Security Service had been able to obtain on the pair. (That gasp of relief is not expressed in Martin’s report of the conversation, where he less definitively records: “He thought, too, that BLUNT may have tried to recruit Leo LONG, an undergraduate with a working-class background. On the other hand this may have been a homosexual ‘pass’.” See sn. 312b, KV 2/4705.) In any event, the network of Burgess, Blunt, Straight, Simon, Astbury and Long has emerged as a significant Cambridge cabal.

Barrie Penrose’s and Simon Freeman’s Conspiracy of Silence (1986)

The authors’ exposé of Anthony Blunt relied largely on interviews with contemporaries, such as Brian Simon and Margot Heinemann, and they perhaps should have reflected whether their subjects had an unbiased and totally honest understanding of what went on in the 1930s. Moreover, Penrose and Freeman display an occasionally indulgent attitude towards the nature of Stalinism. For instance, after recounting Simon’s decision to join the Party in 1935 after witnessing the horrors of Nazism, they write that his commitment ‘endured the disappointments of the Nazi-Soviet pact, the Stalin show trials and mass arrests and the post-war occupation of Eastern Europe’. Disappointments? That reaction sounds more like that of weary parents regretting that their offspring has mixed with the wrong crowd. [“Really, Iosif! How could you kill all those innocent people . . .?”] Later, the authors wrote that Simon told them that he was ‘shattered’ by the Pact. He nevertheless managed to pull himself together.

Penrose and Freeman recorded some useful information about Leo Long and the Apostles, and described Brian Simon’s life-long commitment to Communism, despite all those ‘disappointments’. His impression of life in the Soviet Union was overall very favourable, with no unemployment evident. “A planned economy seemed to be working”, Simon observed, perhaps not having been informed about the slave labour of millions in the Gulag. The authors displayed their sympathies: “Privileged and cosseted, they [the tourist group] focused on physical squalor, apparently unaware that for many people in the capitalist West life was not much better.” Towards the end they re-presented Straight’s statement that he was able to help MI5 by clearing his friend Brian Simon of any charge of espionage. On an initial reading, that was probably true: the primary research indicates that Simon had only tried to help Blunt as a look-out for new recruits, and had encouraged subversion in the Army, but Straight’s testimony derived from what Simon told him, so should perhaps be questioned. From this account one might conclude that Simon had little access to confidential material, and a lifelong ‘useful idiot’ would seem to be a more accurate description of this impressionable character.

John Costello’s Mask of Treachery (1988).

Costello picked up some of the threads a couple of years later, although his coverage of Astbury and Long (he does not mention Simon) was – despite his extensive sleuthing, or maybe because of it – a characteristically Costellovian muddle. He wrote that Straight (as the new boy) obliged Blunt by bringing in five new Apostles, and that the recruitment of Long was actively canvassed by Blunt and Astbury. First, he misnamed Astbury as John Peter, instead of Joseph Peter. He then stated, however, that Long and Astbury were elected at the same time in the summer of 1937, and overlooked the fact that, if that were true, Astbury could not have supported Long’s election. He mysteriously claimed that Long was the only candidate who remained Communist for more than a short time, yet, later in the book, wrote that Astbury was a prime suspect of Peter Wright’s. Costello’s chronology concerning Astbury’s time at Manchester University and at Imperial College, London, was haphazard. He also reported that Straight had told him that he had, in 1964, given Astbury’s name to MI5 as an Apostle who had been recruited by Burgess or Blunt. (The archive does not bear that out, but of course, that does not prove anything.) Costello was told by Chapman Pincher that Peter Wright had confirmed to him in 1981 that Astbury’s work made him a candidate for investigation, but Costello did not think to ask either of these celebrated spycatchers why they had both neglected to mention Astbury in their exposures.

The problem is that Costello frequently ended up lost in his own rabbit-holes. On page 412, he dropped a short aside when he recorded that Blunt told MI5 about another Cambridge man whom he discovered making an attempt to recruit Long. As his source, he gave Wright’s Spycatcher, p 222. Yet that page says nothing about Long’s alternative recruitment. In the next few sentences, Costello wrote about Blunt’s running Long during the war: the Endnote to this section echoes Straight’s claim of how Burgess had reported Blunt’s rage when another Apostle had tried to seduce Long. The Endnote then switches to Wright, p 249-250, where the author says that Blunt knew of two other spies, one of whom was the rival described earlier, and Costello cites Wright’s claim that ‘the situation was additionally complicated by the fact that Blunt was having an affair with the potential recruiter’. Only in this Footnote does he also mention that Wright had said that both of those two men, still alive at the time, had worked on the Phantom Program during the war, although they left afterwards to pursue academic careers (p 251).

It is clear that MI5 maintained a close interest in this obvious pair – Astbury and Simon. Wright added that ‘neither of them would agree to meet me to discuss their involvement with Russian Intelligence’. Astonishingly, neither Wright nor Costello describes what the Phantom Program was, as if it were irrelevant. [The Phantom, or GHQ Liaison, Regiment, was a GHQ Reconnaissance unit that gathered battlefield data to be transmitted back to central command. I shall write more on it later.] And then, one hundred and eight pages later (p 592), Costello introduces Astbury for the first time as being also ‘a prime suspect of Wright’ (presumably relying on what Chapman Pincher told him), yet he never makes the connection, or delves into the membership of the Phantom Regiment. He thus fails to come up with the name of Brian Simon either, whose identity as ‘a leading educator and member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party’ is clearly laid out on page 63 of After Long Silence, and his closeness to Blunt and Burgess made very evident in surrounding text. Moreover, Penrose and Freeman had made it very clear that Simon had been a suspect.

Costello relied a lot on what Astbury’s brother told him. H. R. Astbury informed Costello that he never recalled Peter ever coming under suspicion (well, he would say that, wouldn’t he?). Peter Astbury had declined to be interviewed, as was his right, although the archives indicate that he was interrogated, but admitted nothing. Shortly before Astbury’s death in December 1987, Straight was told at a Trinity College reunion that Astbury was studiously avoiding his old friends. MI5 was apparently renewing its investigations into him. His brother mentioned suspicions of suicide. In 1986, therefore, when Spycatcher came out, the laws of libel might have inhibited Wright from naming Astbury, but Costello should have worked it out by 1988.

As I have indicated, an irritating trait of Costello’s is his relegation to Endnotes (which appear copiously in the hardback edition, but have been compressed in the otherwise expanded 1989 paperback edition) of several potentially important observations. As another example, I record Costello’s account of the Blunt ‘confession’. Costello was clearly reliant on what Arthur Martin told him about the episode (although he did not specifically give him attribution in his Endnotes), and for the paragraph where Blunt is reported as ‘saying “It is true” (p 590), Costello provided a long Endnote 13. It details Straight’s meetings with Martin and Blunt, where Straight continued to get dates wrong. Costello then wrote:

Straight’s confidence in Blunt’s good intentions towards him, however, were shaken when I showed him pages from his memoir After Long Silence, which I had obtained from a confidential source, in which Blunt had underlined passages where he claimed Straight was not telling the truth. They had been marked by Blunt before Straight was confronted in a hostile television interview by Nigel West after the book was published in Britain in the fall of 1984.

Why such coyness over such valuable primary material? What were the relevant passages? How did Straight respond to the claims of that notorious liar that he was not telling the truth? On what grounds was West hostile? (Was West the ‘confidential source’?) How did Straight react to West’s attacks on him? What is the point of all this subsidiary material, and why could a proper analysis not have appeared in the meat of the book?

Miranda Carter’s Anthony Blunt: His Lives (2001)

Carter made only a brief reference to Astbury, in a Footnote, but had plenty to say about Brian Simon, whom she interviewed, and whose testimony she trusted. Much of it is familiar, but she did add an account of Simon’s horror at witnessing the results of the Ukraine famine, and she did use the autobiography that Blunt supplied for the NKVD (as presented in West’s and Tsarev’s Crown Jewels, p 130) to identify members of the Communist Pary at Cambridge with whom he socialized – a list led by Simon, Straight, Cairncross and Long, but omitting the name of Astbury. Carter hypothesized correctly that the person whom Straight referred to as someone whom Blunt had unsuccessfully tried to recruit for his Comintern activity was indeed Brian Simon, who had eliminated himself on the grounds that he was ‘not sufficiently strong to survive going underground’. Blunt later tried to use Simon as a talent-spotter instead. Simon no doubt concealed some of his more seditious wartime activities from Ms. Carter.

Roland Perry’s Last of the Cold War Spies (2005)

In his profile of John Cairncross Roland Perry had a few things to say about Astbury and Simon. Perry must, however, be taken very cautiously, as he tends to get carried away with some wild theories. He offers a few useful facts. Leo Long was elected to the Apostles on May 15, 1937, Peter Astbury on June 5. Thus, since Haile Selassie visited the Cambridge Union on June 8, both would have been members of the sect when the photograph was taken. (Straight mistakenly dates the event simply as ‘May 1937’.) If correct, this claim offers a fresh reinforcement of the fact that Astbury could not have encouraged the recruitment of Long. Perry also asserts that Brian Simon had been a lover of Anthony Blunt, ascribing this statement to Straight, which introduces a new dimension to the sexual tensions.

On the role of the Rothschilds in Soviet schemes, Perry is less reliable. Part of his message is the bizarre suggestion that Victor and Tess in combination were indeed the ‘Fifth Man’, with the cryptonyms DAVID and ROSA, but that would be unlikely if those names had been allocated in the 1930s, since the duo did not become an item until after the war started. As I explained in Misdefending the Realm, Rothschild was never going to become involved with the sordid business of passing on secrets, so he is best described as an ‘agent of influence’. Perry makes out that Tess was ‘a fanatical communist’, but that she was inhibited by the patriarchal traditions at Cambridge from playing any role in the societies. He echoes the infatuations that Straight and Simon nursed over Tess, but adds Rothschild to the list of admirers – which is unlikely at that time. Moreover, he suggests that Straight had a dalliance with Victor’s wife, Barbara, one that was engineered by Blunt himself. That again is improbable. Straight did indeed write that he had a fling with the wife of one businessman who got too clingy with him. Perry writes that the affair helped cause the breakdown of the Rothschild marriage, but, since they did not divorce until the end of the war, the claim is tenuous, at best.

Perry writes very little about Brian Simon, primarily echoing Simon’s infatuation with Tess Mayor. He refers to Simon’s affair with Blunt in two places: first, incidentally, in the context of the visit to Dartington made by Blunt, Burgess and Simon in March 1937, and second, much later, in the 1960s. MI5 wanted to find out whether Blunt had actually recruited Simon as an agent, and requested Straight (who was visiting London at the time) to determine ‘the truth’. Perry says that Dick White, the head of MI5 was behind the request, but since White had by then moved on to MI6, Perry’s story is weakened from the outset. Straight’s method was to take Simon out for a hearty liquid-filled dinner to learn the facts. In Perry’s words, Straight apparently reported afterwards to Osmond of MI5 that ‘Blunt had tried to recruit Simon but that Simon had said any move by him would be too obvious since he (Simon) was close to Blunt (so close, in fact, that they were lovers, Straight alleged’.) Of course this might have all been some nifty invention by Straight that Simon did not even know about. He claims that Peter Wright was not taken in by it, despite what Wright wrote earlier. Guy Burgess claimed that he could seduce any man he chose, but for Simon to fall for the charms of Blunt while he was scoring with Tess Mayor seems unlikely. Perry also writes that Tess’s seduction of Simon must have been directed by the KGB (at that time, of course, the NKVD), since no agents would have been allowed to embark on such liaisons without the approval of Moscow. It seems all rather absurd to me. I doubt whether the Simon archive at University College, London (which I plan to visit next month) will shed much light on the matter. I shall report more later in this bulletin when I come to analyze the Blunt archive.

And I must address one significant volume published well after the availability of the Simon PF:

Gary McCulloch’s, Antonio F. Canales’ and Hsiao-Yuh Ku’s Brian Simon and the Struggle for Education (2023)

This book is available on-line at https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10176795/1/Brian-Simon-and-the-struggle-for-education.pdf, published by the UCL Press. University College, London holds the Simon Archive. It is a hagiographic work, largely reliant on Simon’s own published memoir, and unpublished autobiography, while also making occasional use of Simon’s MI5 Personal Files. It focusses primarily on Simon’s contribution to educational theory, but also pretends to give an accurate account of his life before he took up teaching after the war. It has several inaccuracies (e.g. Donald Maclean was at Trinity Hall, not Trinity; Astbury did not attend Gresham’s School, Holt).

It is a very shallow and indulgent representation. Simon’s exploits with Burgess, Blunt and Straight at Cambridge are completely overlooked, as is his dalliance with Tess Mayor. There is no mention of Simon’s visit to the Soviet Union in 1935 – indeed, it would appear from Simon’s unpublished memoir that he denied that he travelled there before the war. Of Simon’s role as a talent-spotter for Blunt, there is nothing. Simon’s career in the Army is sketchily covered, apart from a note that his commanding officer at Catterick overrode the recommendation from MI5 that he not be given a commission because of his seditious activity. The time with the Phantom Regiment is briefly dispensed with: a provocative note about Simon’s enigmatic trips to New York, Africa and Sicily is not followed up. Overall, the volume, emphasizing Simon’s open embrace of Communist positions and organisations, shows no interest in investigating whether he became involved with any clandestine activity.

In summary, enough provocative material has been in the public domain for many years, but it is all rather a muddle, and the reliability of these authors is not great. Moreover, nobody has seen fit to attempt to analyze it, to follow up leads, or to synthesize a coherent narrative for Astbury and Simon from the pickings. I now turn to the archives, and approach them chronologically, by interweaving extracts from the Astbury, Simon, Burgess, Blunt and Rothschild files.

The Archives: Astbury

The vital entry occurs on June 18, 1943 (sn. 32z, KV 2/2884-2). Dave Springhall, National Organiser of the Communist Party, had been arrested the previous day, caught in the act of receiving Air Ministry documents from Olive Sheehan. For some reason (maybe he was not aware of the arrest), Astbury considered it a good idea to visit the Party HQ in King Street, where MI5 had microphones installed. Seeking advice on an overseas posting, Astbury told R. W. Robson that he had been supplying Springhall with information that he believed had been passed on to the Soviet Embassy, probably through a student, either Betty Matthews or Freddie Lambert. He also mentioned that he had also met a ‘Red Army fellow’ some time before, whose name he did not know. (This claim will turn out to have serious implications later.)

For some reason, MI5 did not get round to interrogating Astbury until December 1 of that year, and for confirmation of that event researchers cannot rely on an official record, but have to use another transcript of an overheard conversation at CPHQ. A Mr Rust bursts into the office of Harry Pollitt to tell him that MI5 had seen Astbury the previous evening, and had asked him why he had visited King Street. Astbury had denied any nefarious purposes, and invented some story about hearing that an old college friend, Betty Matthews, was to be found there. While Pollitt appears to be quite blasé about the whole business, Rust expresses great alarm, and leaves the office spouting something about Peggoty Freeman, the Party Organiser at Bedford . . . It is not until June 13, 1947, that a reference to the interrogation appears, when Roger Hollis asked Mr Cussen, who carried out the interview, to call and give his recollection of what took place.

C. A. G. Simkins presented the report, indicating that Cussen told Astbury that the CPHQ was under surveillance, and that he had been noticed entering the CP HQ in King Street. When Astbury continued to assert that he had simply gone there to get in touch with old Cambridge friends, it was found impossible to make him shift his ground in any way. Cussen was extremely clumsy: he stated that Astbury ‘refused to respond to suggestions that he had been inveigled into SPRINGHALL’s espionage activities and that it would be advisable for him to make a clean breast of what had occurred’. That would have immediately put Astbury on guard that his conversations had been overheard, but that Special Branch and MI5 had nothing else they could pin on him, and that, so long as he continued to deny everything and stayed out of trouble in the future, he would be safe. Moreover, he would no doubt have alerted Pollitt in more secretive surroundings. Yet telephone surveillance continued, and long conversations at King Street during the intervening months appear in Astbury’s file. In addition, the incriminated Betty Matthews was persuaded to give a statement to Special Branch, in which she disavowed anything sinister going on, and said that she was unaware that Astbury knew Springhall. Yet, between 1943 and 1947, Astbury had been experiencing some remarkable adventures, while MI5 could only look on powerlessly.

Astbury’s professional qualifications are a source of puzzlement. His file states that he gained his Cambridge degree in history (sometimes anthropology). He was enlisted in the Army on July 4, 1940, was sent to an O.C.T.U. (Officer Cadet Training Unit) on October 9, and, despite being active in two communist cells at Catterick, received his commission on May 30, 1941, and joined 4th division, Signals. On October 27, 1941 he was posted to G.H.Q. Liaison Regiment (Phantom) at Richmond, Surrey, and was promoted to Captain on February 5, 1942. His Commanding Officer gave him clearance of any subversive tendencies, but MI5 wanted to know whether he was involved in any secret projects. The answer came back that ‘the most secret equipment handled by him was of his own invention’. By December 1943 he had truly found his métier in radio research.

While MI5 had earlier requested that Astbury not be sent overseas, his superior officers in Phantom obviously ignored such supplications. MI5 evidently was not tracking his military movements at the time, but Astbury’s file contains a clipping from the Daily Mirror of May 22, 1945, headlined ‘“Fruit Machine’ Was Hun-Beater In Every Major Battle”, and goes on to describe Astbury as the ‘28-year-old genius’ who was the inventor. (It is here that Astbury’s degree is given as being in anthropology.) What his ‘fruit-machine’ accomplished was that it scrambled every message sent (from the field), and then unscrambled it the other end (in Montgomery’s headquarters). The article mentioned Arnhem, but what it did not say was that Astbury had been captured and imprisoned after his glider crashed. It should have been tabu to allow personnel who had knowledge of such sensitive secrets to be sent overseas lest they be captured and interrogated, and that is surely why that information was not released. (The essence of the article also appeared, in more sober terms, in the Daily Telegraph of the same day.) Only on February 5, 1945 did MI5 contact the War Office to determine Astbury’s whereabouts and status, and two days later received the news that Astbury had been categorized as a Prisoner-of-War on September 17, 1944.

Shortly before those newspaper articles appeared, Astbury had been repatriated. He found work at the Labour Research Department for a couple of months in the summer, suggesting he had been demobilized: MI5 was again tracking his calls. On November 14, he is reported to be employed by the Army again, in the ISTC at Catterick, with the rank of Temporary Captain, but was not demobilized until August 4, 1946. By the summer of 1947, MI6 was taking an interest in him, and on June 6 requested a trace of him to Graham Mitchell of MI5, at the same time letting MI5 know that Astbury was now an assistant to Professor Patrick Blackett, the nuclear physicist at Manchester University. While the ‘trace’ request was made probably because of a recommended posting abroad, the fact that Astbury has now been able to add nuclear physicist skills to his portfolio is rather impressive. This trace, however, brings the story back to the confirmation of the 1943 interrogation, with Roger Hollis expressing his surprise that there was no record of it.

Further investigations showed that Astbury was one of a tightly-knit – and very leftist – team working on a ‘Cosmic Rays’ project under Professor Blackett. Where Astbury developed his qualifications is unstated. A note reports that there are two contradictory views as to his scientific ability: 1) that he is good in theory; 2) that he is a nice fellow, but a complete nincompoop living off other people’s brains. It is hard to understand why Blackett (a Nobel Prize-winner) would want any but first-class brains on his team. Another note states, in rather peculiar terms, that Astbury is living at the house of Mrs. Joan Simon, who, like her husband (Brian) has a considerable communist record. Perhaps Brian was occupied elsewhere at the time. In any event, knowing how closely Blackett was to ‘the innermost councils of defence planning’, MI5 was concerned enough to request a telephone check on the house in West Didsbury.

During the next couple of years, MI5 kept an intermediate watch on Astbury, aware of his frequent trips abroad, but not knowledgeable about the purposes and destinations of them. In one notorious incident in 1948, he left behind on the quay at Newhaven a letter of introduction to Togliatti, the Italian Communist leader, from Harry Pollitt, written a year beforehand. A remarkable letter on file, dated January 25, 1949, is signed by Detective-Sergeant Robert Mark, noting that he himself had served in the Phantom Regiment during the war, and knew both Astbury and Simon as ardent communists. Mark, who questioned the wisdom of employing Astbury as a lecturer in physics in a project related to atomic energy, would later be the renowned Sir Robert Mark, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police from 1972 to 1977.

Blackett himself came under suspicion at this time, although Sir Henry Tizard at the Ministry of Defence continuously supported him. John Curry’s history of MI5, written in 1946, reported that Blackett had given information to the CPGB before June 1943, when he had been Scientific Adviser to the Admiralty on Operational Research, which must have been regarded as an inexcusable action, and cast permanent doubt about his integrity. Richard Aldrich has written that Blackett, for several years after 1945, had been a disaster as chairman of the scientific intelligence sub-committee reporting to the Joint Intelligence Committee. In his diary entry for December 2, 1948, Guy Liddell records that both Blackett and Astbury were then regarded as a security risk.

Dick White and Graham Mitchell visited Tizard on July 22, 1949. MI5 had detected leakage from Blackett’s laboratory, but Blackett claimed, perhaps ingenuously, that he could not imagine which member of his team there could justify any uneasiness. In October Tizard was moved to identify Astbury to Blackett, who assured Tizard that he had tightened up his security arrangements, and that Astbury could not have access to confidential information. He confirmed that Astbury, ‘an excellent teacher and a great help’, was on probation, and the time was approaching when he would be considered for permanent employment. He was uncomfortable about terminating Astbury if he was only under suspicion, although Astbury’s fervent support of Communism should perhaps have given him pause for reflection. Tizard himself showed some ingenuousness while going along with the less cautious approach to handling Astbury’s evident loyalties, as Mitchell minuted, on November 11:

It should be recorded that the singular naivety of some of the questions that Tizard put to me about the Communist Party suggested that he has no comprehension whatever of the nature of the Communist set-up in this country – even less than I should have credited the man in the street with.

What made the leniency shown to Astbury even more astonishing was the fact that Prime Minister Attlee’s Purge Procedure had been in full swing for some time. In January 1949 he had announced that eleven government officials (ten of them communists) had been removed from sensitive work, and in August 1949 the Soviet Union had carried out its first test of atomic weaponry, thus greatly alarming the administrations of the USA and the UK. Surely this was the time to act on Astbury? Yet even Astbury’s meeting with Nicolai Korovin and Professor Gluschenko from the Soviet Embassy, arranged in November by the suspected communist courier Danny Nahum, did not stimulate any action. Instead, MI5 increased surveillance, in the familiar hope, perhaps, that they would uncover a broader and more baleful nest of evil-doers by that stratagem.

In April 1950, MI5 learned that Blackett had offered Astbury a job in the Pyrenees. In early June Astbury received notice that his application for a permanent post in the Department of Physics at Manchester University had been rejected, but he was probably not surprised, as, a week later, he was confirmed as taking up an appointment at the Scientific Research Laboratory at Pic du Midi in France. Another report emanating from the local CP meeting informed MI5 that Astbury would go to the Jungfrauhoch High Altitude Research Station in Switzerland in July, for two or three months. By then, Simon had decided to take up a position at Leicester College: Dick Thistlethwaite (B1f) noted that Blackett’s entourage would be ‘two Communists the less in the fairly near future’.

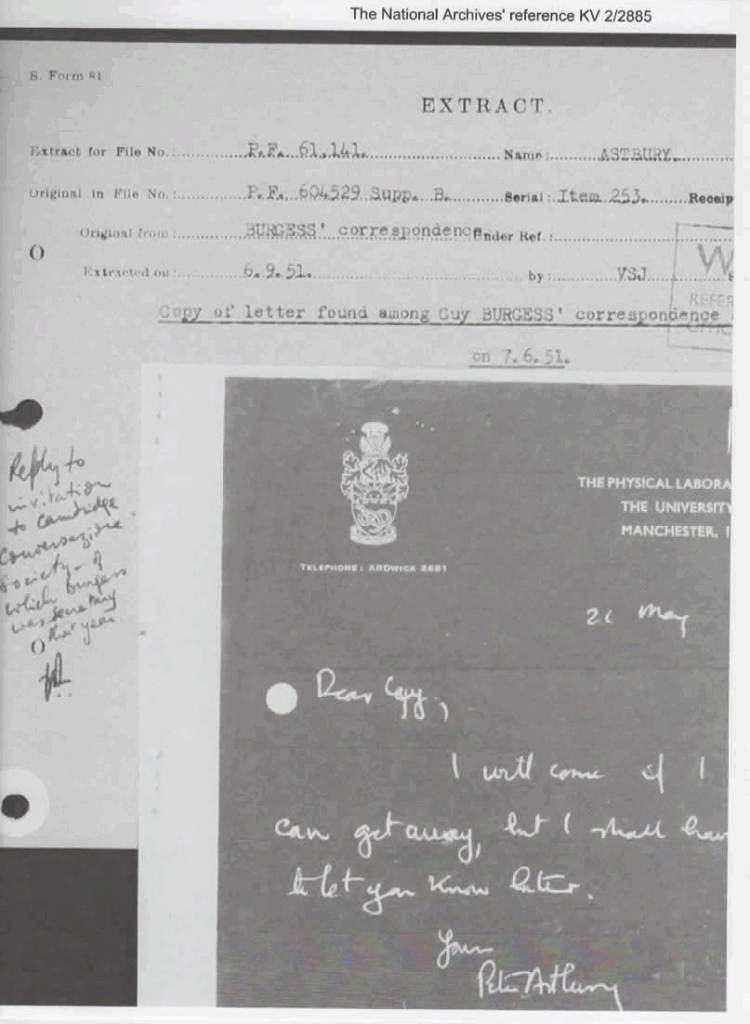

Astbury’s position at the Jungfrauhoch turned out to be more long-lasting, and he made several visits there over the next couple of years, Special Branch always being careful to inspect his luggage. By now, however, he was surely very careful not to carry anything incriminating about his person, although he did continue to wear his Communist credentials on his sleeve. On June 26, 1950, Guy Liddell reported in his diary that the Czechs had tried to recruit him, but how he acquired that knowledge, unless Astbury had come clean and admitted such, is not clear. (His file shows that his telephone calls were being intercepted on that very day, but nothing about Czechs has been recorded.) On July 14, he learned that he had been appointed as a Research Assistant (i.e. a demotion) at Manchester University, but accepted it since he had failed to obtain a job elsewhere. Yet he continued to draw attention to himself, by attending a Peace Conference in Budapest in October, sponsored by the Hungarian Communist government, and making an incendiary speech. A declaration he made of his Communist convictions when he returned on November 8 appeared to shock the Press, but it must have come as no surprise to his employers, nor to MI5. Blackett was angered by the adverse publicity, and warned that any further such actions would lead to dismissal. Astbury continued his visits to Switzerland, and returned on June 8, 1951, carrying a quantity of rolls of film, which he claimed contained research photographs. On the previous day, however, a letter from Astbury to Guy Burgess had been found among Burgess’s papers at his flat.

The letter does not appear in the Burgess Personal File. It is dated May 21, but the year is uncertain. It has been written on official University notepaper. An annotation states that the letter is ‘a reply to invitation to Cambridge Conversazione Society – of which Burgess was Secretary that year.’ (The Conversazione Society was another name for the Apostles.) The address is familiar (‘Dear Guy’, not ‘Dear Mr Burgess’), but the closing is more formal (‘yours, Peter Astbury’), no doubt to ensure his identity was not mistaken. Astbury did not start work at Manchester until June 1947, so the year must have been one of 1948-1950. But how did the annotator know that the letter was in response to an Apostles invitation unless Burgess’s invitation was also discovered? And why would ‘the authorities’ consider anything sinister behind the procedure of postal exchanges concerning a legal society? Was it an unnecessarily obvious move by Burgess even to keep such a remnant, let alone leave it behind to be found? Were other Apostles’ responses kept by him? Or did it represent part of Burgess’s undeniably spiteful initiative to incriminate others before he absconded?

If Burgess was being provocative, it was not merely at the expense of Astbury alone. A very revealing entry in Blunt’s Personal File (in KV 2/4711) provides a list of Apostles that is described as deriving from Burgess’s Correspondence, ‘mainly from 1949’. It suggests that Burgess had indeed kept many responses to his invitations. When Tom Driberg wrote his profile of Burgess in 1956 (A Portrait with Background), he rather ingenuously wrote “I was unable to persuade Guy to tell me who his fellow-members were . ..”, but Driberg may have been dissembling, or Burgess may well have been pulling Driberg’s leg, considering the trove he left behind in his flat. That collection was rigorously trawled by MI5: sixty-three Apostles were listed (some of whom were deceased by then), but the sheer volume set MI5 on a wild goose-chase that consumed an enormous amount of time for little reward.

The event that prompted the invitation was in fact quite epic. It was the 1949 Annual Dinner held at the unlikely venue of the Royal Automobile Club: Apostles were not normally known to be secret petrolheads. Burgess was in fact Chairman, not Secretary, and in his occasionally enlightening, very choppy, and ultimately pointless study of the Apostles, The Cambridge Apostles (1985), Richard Deacon highlights the event as one of the most successful. (For some strange reason, Deacon omits Astbury from his extensive list of Apostle members. Nor does he list Francis Haskell, one of the subjects of the positively reviewed but essentially bloodless study by Iain Pears, Parallel Lives, which was published earlier this year.) Two other items of evidence shed further light on the matter. The first is the presence in Burgess’s file (at page 66 in KV 2/4531-2) of a letter from Victor Rothschild, dated June 1, 1949, also declining the invitation (see figure below). Astbury’s reply was dated May 21, so Burgess was obviously soliciting early, and Rothschild was dilatory if the invitations went out at the same time. Yet I would point out how coolly and formally Rothschild signs off: no longer ‘love’ (his traditional signing-off to his close friend), but ‘yours sincerely’, which sounds completely artificial. No one would respond to a long-standing friend in that way, even if the pair had drifted apart. It appears to me as a clumsy exercise by Rothschild to distance himself from Burgess. (It looks as if Rothschild signed it himself.) Thus the nature of the replies of Astbury and Rothschild is more telling than the disclosure of their names.

The second important datum is the presence at the dinner of the American Michael Straight (who eventually shopped Blunt). I wondered whether Burgess had encouraged Rothschild and Astbury to attend because of Straight’s committed attendance. Since matters were heating up, the dinner might have provided an opportunity to get stories aligned (not at the dinner itself, as not all would be in on the plots, but in separate meetings). I don’t trust Straight’s account of things – where he suggests it was all impromptu and accidental – at all. In After Long Silence (p 229), he writes that he and Milton Rose were in England ‘on family matters’ when they passed Burgess on Whitehall. Burgess told him that the Apostles were about to hold their annual dinner at the RAC, urged Straight to attend, and Straight said he would. This was a forerunner of the chance encounter with Burgess in March 1951, when MS bumped into Burgess by the British Embassy in Washington, and warned him to break off his espionage, else he would report him. Two chance encounters in two busy capitals? That does not convince me. I suspect that Straight had planned to attend the dinner all along, and may have built his itinerary around it.

The problem is that Straight gave wholly contradictory accounts of his intercourse with Burgess over the years – to the FBI on two occasions in the summer of 1963, to Arthur Martin in his interview in February 1964, to Wright and Martin in the joint interview with Blunt later that year, and in his memoir of 1983. It appears that he wanted to accelerate the dating of his break from Communism when he made his confession to the FBI, and consequently misrepresented his relations with Burgess before 1949, since Burgess would not have been so welcoming to him had he suspected that Straight had changed his spots some time before. Unlike Goronwy Ress, Straight probably presented the truth a bit more accurately when he came to write his memoir. He was safe by then.

There was a rumpus at the dinner, because Straight was seated next to the unspeakable Eric Hobsbawm, and the duo had a loud argument about Hobsbawm’s defence of the Czech invasion, with Straight being rebuked by other members because he was not acting in a becoming manner. Burgess and Blunt requested a meeting with Straight the next day, at the same club, when they challenged him to admit whether he was ‘still with them’. After some prevarications, Straight claimed that Guy had arranged the meeting in the club in order to learn whether he had already turned him in to the authorities. But that does not make sense: if Burgess had been fearful that he had been turned in (unless Straight’s challenge to Hobsbawm at the dinner had been the instigator of the suspicions), he would have quickly arranged a quiet chat rather than inviting Straight to a broader gathering where he might talk too much. I recall that, in 1947, Straight had warned Burgess about his illicit activities. It is all too much of a coincidence, and does not sound plausible. Of course, this tale would not have been available to MI5’s officers in the late summer of 1951, but the discovery of the Astbury and Rothschild letters might have given them pause for thought.

The story on Astbury fades away soon after this. In August 1951 he was recorded as being more wary with his CP friends. He continued going to the Jungfrauhoch into the Spring of 1952, but it was then announced that he would be leaving Manchester that year: Blackett, tired of leftist shenanigans, had opposed his re-appointment. A ‘well-placed and reliable source’ told MBT in B1F that Blackett was trying to secure a grant from ICI to allow Astbury to work at London University under Professor Massey. Astbury did indeed take up a position at London, but the final file (KV 2/2886) contains nothing of unusual interest, and is closed in 1957 – not without revealing that Astbury and Simon were still meeting occasionally. His scientific career continued to take immense leaps, however. As one memoir reveals (see https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/161268/from-archives-early-physics-research-imperial/ ), by the nineteen-sixties he was a Ph. D. supervisor in nuclear physics at CERN – a big step up from his role as Research Assistant at Manchester. Professor Massey must have developed him fast.

One last gem needs mentioning, however. At sn. 161b in KV 2/2885 appears a note from November 11, 1952, sourced from B1F in MI5, capturing an interview with Leo Long in which he revealed information about his contemporaries at Cambridge from 1935-1938, and commented that Astbury had been an Apostle as well as a Party member – item number 13 extracted from the report. Now Long’s PF has not been declassified, so we do not know whom else he shopped, and what else he said. 1952 is very early in the Blunt-Long saga, however, and we know that Martin claimed to have elicited the name of Long from Michael Straight only in early 1964, and then suggested it to Blunt soon afterwards, without a great deal of confidence. (See my comments under ‘After Long Silence’ above.) That is now all shown to be another part of the charade. It is not surprising that Long’s PF has not been released, if the main revelation from it would be that Long confessed and gained immunity in 1952.

The Mysterious Long Interrogation

The Long item described above presents formidable problems to the analyst of the Blunt ‘confession’, and indeed for the subsequent investigations into Communist penetration. I consider three alternative explanations of its appearance in the Astbury file:

- It is not genuine, and thus it cannot be assumed that Long was communicating to MI5 freely about his colleagues at Cambridge as early as 1952. The ‘official’ accounts of the Blunt ‘confession’, and the subsequent unmasking of Long, for all their defects in chronology and stagecraft, must stand as a solid guideline to the course of events, and the actions of the participants.

- It is genuine, and the fact that Long (who later admitted to passing military secrets on to Blunt during WWII) was speaking freely to his MI5 interlocutors suggests strongly that the officers in B Division would have known about the espionage of both him and Blunt twelve years before it had been officially recognized. That scenario would add fuel to the argument that White and Robertson did follow up their suspicions concerning Blunt in October 1951 more aggressively than any archival source has indicated, and engineered some kind of plea bargain with him before November 1952. That explanation has massive implications for the presentation and interpretation of events in the Blunt Personal Files.

- It is genuine, but of local relevance – to Long only. MI5 must have found some reason for interrogating Long that did not involve Blunt, and Long volunteered some names (such as Astbury’s) as part of a routine response, or in order to fulfil his part of whatever agreement he made with MI5, without mentioning Blunt. Such an explanation of course greatly undermines the proclaimed sequence of events in April 1964 by which Straight and Blunt gave up Long’s name, to the great relief of Arthur Martin, but it is possible that Long was not regarded as a suspect at this time.

I shall return to these scenarios, but move to study the contemporary records first. Blunt’s file shows that, in August 1952, a ‘reliable source’, to whom Blunt had been French supervisor at Cambridge, offered some information about Blunt’s friends at Cambridge (see sn. 117a in KV 2/4701). Ironically, the informant did not consider that Blunt had been a serious Communist at the time, while some of his friends had indeed been such. Blunt was very close to Long, he said, but Long was already a communist when he arrived at Cambridge, and was not converted by Blunt. The communist friends included Michael Straight and Hugh Gordon, as well as R. L. M. Synge, Peter Astbury and S. Devons. A separate note on Long states that Long ‘was a protégé of Anthony BLUNT at Trinity and was associated with BLUNT in a secret department during the war.’

The first reference to Long is a note by G. H. Leggett (B1F) on December 15 (under sn.127z in KV 2/4702), but there is strangely no record of the statement Long made concerning Astbury (November 11) in that Blunt file. Leggett rather bizarrely adds: “It is B.I.F’s intention to go back to Leo LONG presently, by arrangement with D.B., in order to ask him further specific questions about Communism at Cambridge in the late thirties”, whereupon J. D. Robertson (B2) asks Evelyn McBarnet whether she has any questions to put to Long. McBarnet’s response is dated December 29. She notes that Long’s years at Cambridge (1935-1938) are a little late for MI5’s special interests, but ponders vaguely about the chances that Long might have something to say about Burgess.

I came up with multiple questions concerning these few items. For instance:

- What was B1F?

- Who was G. H. Leggett?

- Who was the ‘reliable source’?

- Why has the record of the earlier interview with Long not been posted in the file?

- Why did McBarnet show so little interest in the Long connection?

- Why were ‘arrangements’ required with D.B. (Dick White) to follow up with Long?

- Why did no progression of this initiative appear in the file?

What was B1F?

You will look in vain in Christopher Andrew’s authorized history for much mention of B1F after 1938, when Maxwell Knight’s M Section was incorporated under that nomenclature. John Curry informs us that M Section was split off again in 1942, and B1F became responsible for Japanese Espionage. At some stage after the war, it was reconstituted as ‘Covert Communist Activity/Investigations Agents and Informers/Communism in the Universities’, in a rather dramatically fragmented B1 organization that covered B1A (British Communist Party) to B1K, Maxwell Knight’s enduring M Section. B1F (‘a new section’) had been established on January 1, 1950 ‘to take over from B1A the work in connection with the clandestine activity of the Communist Party’, and was led by Richard Thistlethwaite, who had been MI5’s representative in Washington until 1948. Yet B1F was abolished in July 1950, with work transferred primarily to B1A, and Thistlethwaite assumed leadership of B1G, which covered the CPGB, its Foreign Activities, and Communists from Overseas. Andrew (who is haphazard and thoroughly lazy over MI5’s organization) offers, in Note 11 to his chapter on the Communist Party of Great Britain, the dubious insight that ‘Knight’s section was renamed B1K in 1952 and B1F in 1952’ [sic], which is probably the work of a confused research assistant.

Ewing, Mahoney and Maretta, in MI5, the Cold War, and the Rule of Law, make some provocative assertions while usefully exploiting the file at KV 4/162. They state that in 1951 Courtenay Young managed a section containing i) B1a, and ii) B1a/Investigations, which included B4C, and that this second unit became B1H. Yet B1H is shown as a completely separate, though anonymous, entity reporting directly to Marriott, head of B1, in the chart in KV 4/162. These authors also claim that Thistlethwaite gave up his B1G responsibilities in the 1951 re-organization, ‘continuing as B1F’, and cite examples from Personal Files to show that he was the ‘universities specialist’. I can back that up. For example, I have found an instance in one of Burgess’s files, namely at sn. 301a in KV 2/4106, where in October 1951 Evelyn McBarnet wrote to Thistlethwaite of B1F about the Cambridge careers of CURZON (MacLean), Burgess, and PEACH (Philby). Yet B1F does not appear in Dick White’s organization chart: it is as if it were a clandestine section, maybe managed by White himself, and whose existence was not openly admitted. (The files KV 4/161 and 4/162 purportedly cover MI5’s organization up until 1953, but close disappointingly in June 1951.)

Ewing & co. also assert that B1H (Investigations Agents and Informers) was dissolved late in 1951, with responsibilities relinquished to B1K (Maxwell Knight’s newly split off section) and to B1F, although there is no evidence for that claim in the files. As evidence, they cite memoranda in the Pritt and Redgrave files that point to B1H activity in the summer of 1951, while by the end of the year such reports are sourced as B1K. A more probable explanation would be that Thistlethwaite was charged, after the escape of Burgess and Maclean, with setting up the B1F unit that maintained sensitive informants within the universities to report on questionable figures (see, for example, the case of Blackett and Astbury above).* That would constitute a typically dilatory response by White to a threat that he had acknowledged, but kept to himself. Yet, in that case, what was B1F doing interrogating Leo Long (which should have been the responsibility of B2)? And why has the historical record been purged of the years 1951-1953?

[* In The Cambridge Apostles, Deacon informs us that Nicholas Walter, the son of Grey Walter, familiar to this parish, wrote to Private Eye in November 1979, namely just after the Blunt disclosure, stating that he was told by his father that ‘the Security Services were still interviewing Apostolic suspects up to the 1970s. He told me that he was interviewed by MI5 officers during the late 1960s, well after the Philby defection and Blunt confession, and that they were particularly interested in the social activities of the Apostles during and after the war, and were taking statements from hundreds of prominent men.’ This section was presumably B1F, or whatever it evolved into. When Evelyn McBarnet presented a list of prominent Apostles to Victor Rothschild in February 1966 (see sn. 74b in KV 2/4532), she was working as D1/Inv.: the ‘Burgess list’ was clearly commonly used by then. I have that issue of Private Eye in storage, and hope to retrieve it soon.]

Who was G. H. Leggett?

Likewise, you will find no mention of ‘George Leggett’ in Andrew’s Index. This is quite astonishing, as he was a significant but controversial figure. He was indeed in charge of B1F in 1952, and had been carrying out a study of Cambridge academics with baleful influences at the time. (When Thistlethwaite had moved on, and whereto, are unclear: he must have still been in MI5, since he lectured to outsiders as an expert on Communism. Liddell reported that he received a promotion in April 1953.) The Maurice Dobb PF (specifically sn. 133a in KV 2/1759) shows that Leggett was investigating both Dobb and Piero Sraffa in the autumn of 1952. Leggett (who was half-Polish) joined MI5 during World War II (according to Nigel West’s Historical Dictionary of British Intelligence) and ‘spent most of his career studying Soviet intelligence organizations and their operations’. If that is true, it is remarkable that his researches are not more prominent. According to Trevor Barnes, Leggett is the figure behind the pseudonym of ‘Gregory Stevens’ in Spycatcher (pp 320-324), a character of somewhat dubious credentials who had run the old Polish section of MI5, and held on his résumé the assistance to Stalin on translations at Yalta, as well as having relatives in the Polish Communist Party in London. He was forced to resign in the wake of the Golitsyn revelations after Wright accused him of being the ‘middle-grade’ spy called out by the defector. A letter in Burgess’s PF (sn.737b in KV 2/4115) shows that Leggett had been MI5’s Security Liaison Officer in Canberra in June 1956. According to Adam Sisman, he had also been responsible for recruiting David Cornwell (aka John le Carré) to MI5.

What is also fascinating is that Leggett had, way back in 1940, been quite an authority on Communists. Guy Liddell records in his diaries of going with Roger Hollis in May of that year to consult Leggett for advice on what should be done with communists in industry. Leggett was apparently a hard-liner, and in close contact with Ernest Bevin, since, in January 1941, Liddell reports that Bevin and Leggett wanted the CPGB and the Daily Worker suppressed. This matter is evidently ripe for further research.

Who was the ‘reliable source’?

Leggett’s informant obviously knew the Cambridge set-up well. The officer ‘RT’, working for Leggett, states that his source ‘is reliable and well qualified to judge political opinions’. He was obviously familiar with Long, since he passed on the fact that Long ‘was a member of the Communist Party when he was at Cambridge before the war’. Furthermore, ‘he was a protégé of Anthony BLUNT at Trinity and was associated with BLUNT in a secret department during the war’. In addition, the source ‘knew LONG personally and might be able to obtain further information’. The notes in KV 2/4701 do not contain, however, the information shown in the Astbury file that Long was also an Apostle (a not incontrovertible fact, but one that is reasonable to assume, if Long was admitting knowledge of Astbury’s membership). I suspect the informant was Noel Annan, taught by Blunt, also an Apostle, but now a well-respected intellectual. He wrote about Long extensively in his book Changing Enemies, since he worked alongside him in MI14.

Why has the record of the earlier interview with Long not been posted in the file?

It seems to me that B1F and B2 were not working in close harmony. Leggett’s memorandum of December 15 refers to serials that are not present in the file, and Robertson responds by alerting McBarnet (B2B) of another serial that is not present. McBarnet’s response, in turn, sent on December 29, eleven days later, suggests that she has not seen any transcripts of any interview, or previous records, as she describes Long in terms that reflect a vague interest in what he had been up to. She does, however, recognize the link between Apostles (i.e. Blunt and Rothschild) and the news that Leggett brings of Long’s membership.

The context becomes clearer in a note posted as sn. 127z, with a much later date of February 2, 1972. It reads: “No contemporary note was made on BLUNT’s file in December 1952 from the report on the interrogation of LONG. Attached minute sheet from LONG’s file to be p.a.’d under date 29.12.52.” Thus the minutes referred to by Leggett and Robertson are meaningless in the context of the Blunt file.

Why did McBarnet show so little interest in the Long connection?

It is now clear that McBarnet was unaware that Long had undergone an ‘interrogation’, the intelligence on which the 1972 note carelessly gives away. Long was only vaguely on her radar screen, his period at Cambridge did not coincide with the imagined prime influence of Burgess and Blunt, she knew nothing of his wartime activities, and she was not indoctrinated in anything further. She specifically avoids the invitation to follow up on Leggett’s observation that Long may have useful information about Communism in the late thirties, as if she had not seen the original memorandum. All she can say, when casually invited by her boss to offer questions to be put to Long, is whether he has anything at all to say about Burgess, with no mention of Blunt. She was obviously not shown the data from Annan that pointed to the close wartime alliance of Long and Blunt, and she may not have been aware that Annan’s note had been placed in Blunt’s file.

Why were ‘arrangements’ required with D.B. (Dick White) to follow up with Long?

Robertson very carefully asked McBarnet to offer question to be put to Long. He did not invite her to direct any questions in person to him: they are to be ‘put’ through a third party. White must have been very concerned about lower-level officers learning too much about the secret that he and Robertson shared (as is my belief) – namely that Long and Blunt had been detected in 1943 in passing on secrets of German war plans to the Soviets, but had been accepted or forgiven at the time because it was part of Blunt’s role to provide casual information to them as part of his cover. White and Robertson had also been shocked, in the wake of Burgess’s and Maclean’s escape, into accepting the fact that Blunt’s activities had been devious, and wanting to offer him an immunity deal if he promised to tell all. That was not a ploy that the pair wanted broadcast any further. Thus White would have issued very careful guidelines to Leggett as to how he was to proceed with Long, and made sure that knowledge of the arrangements with him were kept to a very select few.

If we can rely on the 1972 minute, it was not simply a case of Annan passing on useful insights on Long. Long was actually brought in for an ‘interrogation’, not just an interview. Admittedly, the two terms are often used interchangeably, but an ‘interrogation’ sounds more formal and maybe more severe: that fact that the report had numbered bullet-points rather than consisting of a mere transcription suggests that it was more structured and more serious. An officer identifiable solely by initials as ACE, in K7, who provided the note, must surely have read the whole Long file at that time, in order to authorize the extraction of key elements to the Blunt file. The move may be interpreted as another subtle hint that more should have been done at the time. (1972 was mid-way between the Blunt ‘confession’ and his unmasking.)

Why did no progression of this initiative appear in the file?

In summary, this was not perceived as an issue concerning Blunt for those investigating him at the time in the curiously named Russian and Russian Satellite Investigation section (B2A: Jim Skardon, Miss F. M. Small, and C. A. G. Simpkins), and Russian and Russian Satellite Espionage Information section (B2B: McBarnet, Joan Andrews, and A. F. Burbidge). If their respective roles are not immediately obvious, their efforts as displayed in the archives do not provide much greater clarity. Dick White tightly controlled the flow of information surrounding Long, and probably regretted that Leggett had been given the tip by Annan. The several subordinate officers working on the case were thus not provided with the full information needed to do their job properly. The secrets are still held in the Long Personal File.

In summary, Explanation 3 is the correct one.

Investigating Blunt: the Simon Affair

[This section is more ‘A’ than ‘B’ material, reflecting close examination of Arthur Martin’s investigations into Blunt and Long, and is laid out for important reasons of historiography. Readers may choose to skim it, and read the summary at the end. What it mainly serves to show are the knots that Blunt and Long tied themselves into trying to explain away the Astbury-Simon business, and how ineffectual Martin was in pinning them down, or calling out their lies and evasions.]

For several years, Long, Astbury and Simon stayed in the background. In last month’s report, I covered much of the action between 1952 and 1964, when Courtenay Young and Arthur Martin were in the forefront, after Dick White restructured M5, and the remnants of B Division were reassembled into D Branch under Graham Mitchell. Only after the Blunt ‘confession’ of April 1964 do Blunt’s relationships with Long, Astbury and Simon come under scrutiny. I refer readers to my analysis of the Blunt confession from early 2021: https://coldspur.com/the-hoax-of-the-blunt-confession-part-1/, and https://coldspur.com/the-hoax-of-the-blunt-confession-part-2/. I have recently added commentary that reinforced my initial suppositions, at https://coldspur.com/an-anxious-summer-for-rees-blunt/. Cabinet Secretary Sir John Hunt confirmed that the immunity deal had been offered after the confession. The exchanges concerning the preparation for the epic confrontation between Martin and Blunt, to be found in KV 2/4705, add some wry incidental information to the saga, but do nothing more than show how junior officers were misled.

A ten-point memorandum was prepared – probably by Evelyn McBarnet – for Martin’s interview with Blunt. It makes no mention of Long. Towards the end of the interview, on April 23, 1964, when Martin is probing for the names of Blunt’s friends who might have been involved, and Blunt hesitantly states that there had been none, Martin brings up Long’s name. Martin records Blunt’s response: “He sighed and admitted that he had recruited Leo LONG at Cambridge and had tried to reactivate him during the war but was sure that he had failed.” Blunt’s long trail of mendacity starts here. Martin tells him that he will take up the Leo Long story later. In fact, Martin follows up very tentatively two days later: the following is the only mention of Long in a report that lists dozens of possible accomplices:

I told BLUNT that we might need to take action on some of his information. For instance, I thought we might have to interview Leo LONG, Goronwy REES, Edith TUDOR-HART and possibly others. Moreover we might need his active participation in operations along the lines of Michael STRAIGHT’s offer to confront BLUNT. What did he feel about it? BLUNT said that he would like to turn the question over un his mind. He certainly wanted to help us if he could.

‘What did he feel about it’? Who is in charge here? Who should be under pressure? What do Blunt’s sensitivities have to do with it? It is all very amazing.

A further meeting took place on May 1, when Martin again took an obsequious pose: “I asked him if he now felt any revulsion at the idea of helping us, explaining that I could well understand that talking about his friends must be repugnant to him.” Yet, before Martin has evidently picked up the case of Leo Long, events take a strange turn. It is worthwhile re-presenting an important paragraph in full, as reported by Martin, that records what Blunt said:

In the summer of 1939 he and BURGESS had been temporarily out of touch with ‘George’ [their NKVD handler]. During one of their discussions BURGESS had said: ‘Wouldn’t it be splendid if we had Brian SIMON looking out for likely recruits for us?’ SIMON was at that time a leading figure in one of the Communist Party youth movements. BLUNT, who was a close friend of SIMON, interpreted this as an invitation to try to recruit SIMON. This he did, and SIMON showed himself willing (indeed, BLUNT said, SIMON was overjoyed to discover that BLUNT was a dedicated worker and not the dilettante he had thought him to be). However, despite his promise, SIMON did not produce any likely recruits, probably because the war intervened (It was in order to find a reason for SIMON’s non-productiveness that BLUNT dates the episode as 1939; in discussion later he agreed that it might have been 1938 in which case the GLADING arrest might have been the cause of the break in contact with ‘George’; however, if it was 1938, BLUNT could think of no reason why SIMON should not have produced recruits; he rejected my explanation which was that SIMON might already have been working for the G.R.U. [Soviet military intelligence]

What fresh nonsense is this? It is difficult to know which parts of this are pure fancy. Why on earth Burgess would have thought it a good idea for the unqualified Simon to start asking questions of possible recruits, with a view to signing them up for Soviet espionage, without Moscow Central approving the plan, is quite extraordinary. But what stands out is Martin’s sudden knowledge about Simon and the GRU. Where did that spring from, if, a few days ago, he had been struggling to find names to suggest to Blunt as possible conspirators? Was Simon a more established figure at this time? Yet Simon’s failure did not deter him, it seems, since, four or five years later, he tried again. The next paragraph reads:

The next episode in this story occurred in about 1943 when Leo LONG came to BLUNT in some agitation to say that Brian SIMON had tried to recruit him on behalf of Peter ASTBURY. SIMON had explained to LONG that ASTBURY was working for the Soviet Military Attaché. BLUNT reported this to ‘George’ (or his successor) who promised to ensure that this did not recur. BLUNT also saw SIMON and told him to ‘lay off’ LONG.

It was not exceptional for the GRU and NKVD to trip over each other in recruitment: it happened to Klaus Fuchs, for instance. Yet what stands out to me is the durability of Simon as the recruiting agent, and the fact that he now seemed to be under Astbury’s control, not Blunt’s.

Moreover, Blunt’s testimony is very much in conflict with what was reported in Moscow: in The Crown Jewels, Nigel West and Oleg Tsarev claim (on page 155) that Blunt had been trying to distance himself from Simon at this time, writing:

On another occasion, noted in April 1942, Blunt learned that a microphone had been installed in the flat occupied by the flatmate of Elizabeth Shield Collins, who was then married to his old university friend Brian Simon. Blunt promptly severed his connections with them, fearing that he might come up in one of their recorded conversations as someone who had sympathized with the Communists.

How, exactly, he ‘severed his connections’, without drawing unnecessary attention to the breach, is not clear. Moreover, his ‘academic’ communist interests were a matter of common knowledge.

Blunt went on to add that he had known Astbury at Cambridge in 1936, and gave a potted history of his career since, without giving any indication that he had been a spy, or commenting on the extraordinary claim that Simon had made about Astbury’s close relationship with the Military Attaché – which would have been extremely dangerous. Martin, however, poses no further questions on these extraordinary revelations. Having earlier raised the possibility that Simon might have been working for the GRU, he seems utterly incurious about the possible links between Simon and Astbury in that respect. “Having finished with this story. . .”, he writes. It is a large opportunity missed by our ace counter-espionage officer.

A further interview took place two days later. They returned to the subject of Long, but not the Astbury-Simon incident. Blunt reported that he met Long about once a month soon after he (Blunt) joined MI5 (in July 1940), but Long failed to come up with much material, to the degree that his Soviet controller complained. (So much for Blunt’s earlier statement that he had failed to re-activate Long during the war.) Blunt also referred to the occasion in 1945 when the Soviets had applied pressure on him to get Long recruited to MI5. Long had expressed little interest, and, despite Blunt’s probable mentioning of the opportunity to Dick White, nothing came of it. Martin asked whether Blunt might help in the interrogation process of some of the persons he had named. On Simon, Blunt said he was a still a close friend, but he was convinced that Simon could never be induced to talk – thereby suggesting that Simon did have matters important enough to be silent about. Blunt knew Astbury less well, but doubted that he could be induced to talk, either. Perhaps it did not occur to Martin that Blunt might already have been in contact with his two compadres, and had impressed upon them the necessity of saying nothing.

Yet Blunt had a plan for Leo Long. Yes, he might be of help, although he could not be sure that Long was still working for the Russians. “He suggested”, wrote Martin,” that he might have LONG to his flat and try to establish that he had had a change of heart. I could be waiting in an adjoining room ready to join in if the prospects were good. I said that I would like to think this over.” What Martin’s boss, Malcolm Cumming (D) thought about all this, what guidance or criticism he offered, is unknown. As Peter Wright told it, there was animosity between the two. Martin had wanted Cumming’s job (which Cumming had assumed in the summer of 1963 when Martin Furnival-Jones moved on to become deputy director-general under Hollis), and he resented his cautiousness and old-fashioned ways. Cumming considered Martin an impetuous upstart, while Martin obviously needed someone to guide him in proper tradecraft. Cumming was not the man. Yet Martin was also distracted at this time by his overripe pursuit of the PETERS investigation, hunting down Golitsyn’s ‘deep mole’, and investigating Graham Mitchell, and then Hollis himself. That may partially explain his less than rigorous follow-up: Christopher Andrew dubbed him ‘a skilful and persistent counter-espionage officer’, but he did not show those qualities here.

Another meeting took place on May 20, the day after Martin and Blunt had dined with Straight: Martin’s notes on that event reveal nothing about Long, Astbury or Simon. After discussing his visit to the Philbys in Beirut, Blunt suddenly performs what Private Eye would call a ‘reverse ferret’, and ‘corrects’ what he had stated earlier. The speech is a typical example of Blunt’s weaselly, evasive pattern, where he attempts to act as an outside observer analyzing what he must have thought, and it merits being reproduced in all its ghastly entirety (with original edits preserved):

One thing I do want to say a propos of the story of Peter ASTBURY and Brian. On thinking it over I realize that there were elements of reconstruction in that. I mean it wasn’t a straight memory. Actually my memory (?) because you mentioned the question of the G.R.U. and some time afterwards suddenly what jumped to my mind was Peter ASTBURY – military Attache and Leo, and then remembering the thing more carefully I remembered this came through “X” and what is surprising is that I didn’t remember Brian SIMON immediately. That was what would appear to be reconstruction. I remembered that somebody had taken this notion to do Leo and Leo had come to me and that I had been able to do something about it because I’d known that there had been such (?) contact with. And I remember primarily that it was this that led me to tell George or Henry that I had in fact (recruited Brian?). I only say that because bringing Brian SIMON’s name into it was not a direct memory, it was a reconstruction. I think – I still think it is right, but it was a deduction. From this story.

Martin attempts to make sense of this woeful oration, and appears to gather that what Blunt had done was, when discussing matters with ‘Henry’ [his new NKVD handler, Gorsky], to introduce Simon into the events of 1943 simply because he had recruited him as a talent-spotter several years before. While Blunt stammers that they could get Long to clarify matters, Martin suggests that Blunt is perhaps being protective of Simon. Indeed, as Blunt continues:

Well, I am very fond of Brian. I have got a great affection for him. But – I am sensitive about him, on the other hand my guess would be, you may know better, that his activities are so open that I should have thought that he wasn’t involved in anything like that. But he is – there is no question – that he is now a member of the Central Committee, or something.

It seems clear to me that Simon could not have been too happy when (as I suspect) Blunt recently informed him – his one-time lover – of what he had told Martin at the previous meeting. “Look, chum,” he might have said. “Confess all you want, but leave me out of it. Just keep my involvement as that of an ineffectual talent-spotter in 1939.” And there the matter lies, with both Martin and Blunt talking about Simon and Astbury at the same time, and Martin not sure enough about the facts to challenge Blunt. And ‘End of Tape’. The field is presumably open to see what Long has to say.

Indeed, the plans were set up for the staged encounter between Blunt and Long for May 28, with different procedures outlined for handling the possible responses Blunt might receive from Long concerning Blunt’s confession, and the question of whether Long was still in touch with the Russians, including the possibility of an immunity deal for Long, as well. Blunt telephoned Martin after the meeting and gave him the run-down (sn. 374a in KV 2/4705). Long claimed he had broken off with the Russians long ago; Blunt explained that he had had to confess, and had implicated Long; he wanted Long to confess, too, but Long demanded a guarantee of non-prosecution, partly because, if he had nothing new to tell MI5, they would go after him, and partly because he was fearful what his wife’s reaction would be. The coda to this script, however, is the enigmatic revisiting of the Astbury incident. Again, I reproduce the whole paragraph: