I pick up the remaining nineteen questions prompted by my analysis of the literature on the ‘Missing Diplomats’, last month’s report having been dedicated to Question 1. Reading this will be a slog! No further illustrations to distract you. But it will be worth it, I promise you. Pour yourself a cup of coffee, and bite off three or four sections each day for a week. Take plenty of notes, as you will be tested on this stuff later.

- 2. Maclean as HOMER: When was Maclean first suspected of being HOMER? Why did it take so long to identify him confidently? Did this process have any effect on the project?

On the other hand, we do still wish to avoid any official confirmation of the story that Maclean was being investigated before he disappeared. If this was once established, it might become exceedingly difficult to avoid letting out the whole story, including the source of our knowledge, which it is of the highest importance to protect. (in letter from Patrick Reilly to Sir Christopher Steel in Washington, January 28, 1953; sn. 335 in FCO 158/6)

The struggles to match Maclean to HOMER, and the timorousness shown by MI5 and the Foreign Office in sharing the fruits of their investigations with the FBI, constitute a problematic and important aspect of the case. As I wrote several years ago: “Given the intensity of this effort, and its being undertaken by cryptanalysts highly skilled at the task, the time it took for these correspondences to be made defies belief. The name HOMER was decrypted on September 26, 1947. Messages also emanating from the British Embassy, ascribed to ‘Source G’, were known by some time in 1949. The equivalence of ‘Source G’ and ‘G’ was worked out in August 1950. On March 31, 1951, a suggestion was made that perhaps ‘G’ and HOMER were the same person, at which time Eastcote announced it had solved the puzzle. It took three-and-half years for Maclean’s identity as HOMER to be recognized and admitted: a period longer than that between the USA’s entry into the war and VE-Day.”

Part of the dilatoriness was probably due to the hope that the leaker of secrets would turn out to be an American, or at least a person with lower standing in the Embassy, so that the Foreign Office would not turn out to have been shamed by one of its high-flyers. (As late as 1955, when preparing responses to probable parliamentary questions, a Foreign Office employee wrote, absurdly, that six thousand suspects had had to be assessed, and hence eliminated, one by one. This process had taken place while the Fuchs and Pontecorvo incidents were taking place: yet it was a highly restricted document that had been passed to the Soviets, which must have restricted its circulation.) If the investigators had been more attentive to the testimony of Walter Krivitsky, however, and his references to the ‘Imperial Council’ spy, they might have focussed their attentions on Maclean a little sooner, instead of pretending to themselves that one of their ‘family’ could not possibly be a traitor, or that a minor clerk or typist had conceivably been HOMER.

I remind readers that Roger Makins had informed Anthony Glees that he was asked to keep an eye on Maclean when he rejoined the Foreign Office in November 1950. Why would that be? If Maclean had simply been rebuked for irresponsible behaviour, and diagnosed as requiring psychiatric treatment, that would have been an internal Foreign Office matter of discipline. It suggests that White harboured other suspicions about Maclean, and the timing of it would indicate that Maclean fitted the profile of the HOMER spy, and that the investigating team had turned its sights on Maclean far earlier than the archival material suggests. After all, if Philby had been able to discern the equivalence, MI5 should perhaps have been able to perform the same exercise.

It comes back to the ‘Imperial Council’ reference that Krivitsky had so precisely nailed. When the investigation into Embassy staff was in full swing, Philby boldly drew attention, on November 19, 1949, to Walter Krivitsky’s description of a spy in the Foreign Office, and reminded Sir Robert Mackenzie of the parallels between Krivitsky’s revelations in 1939 (actually, early 1940) and the leakage from the Embassy in 1945. Philby did not want ‘this disquieting possibility’ to be overlooked. Apart from the fact that Philby was already willing to sacrifice Maclean to save himself, this should have been an alarm-call to accelerate the project. Yet Carey-Foster was unimpressed. Beside a few disturbing reactions in the pursuant correspondence, and an indication that MI5 was not being told all, Carey-Foster deflected any further inquiry, replying on December 9: “I think it right to say at this stage that there is absolutely no evidence to connect the Washington case with the ‘Imperial Council’ story contained in Krevitsky’s [sic] interrogation report.” Nevertheless, he did provide a list of potential diplomats who might have been contemporary and suitably located, including Maclean, before claiming boldly: “There is, however, no other connexion at all.”

These events are remarkable, for several reasons. First, Philby obviously felt confident enough in his guise as apostate-KGB agent turned MI6-loyalist to be able to risk reminding the authorities that he was the probable Times journalist who had been in Spain with Franco – also mentioned by Krivitsky. Second, if he had included some of his cohorts (i.e. Burgess, Blunt, Rees) in his blanket volte-face (a topic I shall visit next month), he had never named Maclean as one of the troupe, since he was here making a pre-emptive strike towards the latter’s unmasking. Third, he must have been sure that Maclean knew so little about his activities that he would not betray him even under intense interrogation. Fourth, the greenhorn Carey-Foster showed extraordinary naivety (or disingenuousness) in dismissing the possible connection purely on the basis of no obvious superficial evidence. Fifth, despite Carey-Foster’s insouciance, MI5 did get excited about the tip, with Geoffrey Patterson in Washington urging a closer inspection of diplomatic records, and this response was obviously fed to Dick White. Sixth, it was immediately after this disclosure that Maclean reputedly requested to be released from his espionage duties (and was turned down), and then, in the first half of 1950 had his mental breakdown in Cairo. Hamrick claimed that White would have established Maclean’s identity as HOMER by January 1949: that may have been premature, but he could well have done by the end of the year. For what it is worth, Maclean’s friend Nicholas Henderson told investigators that Maclean started drinking more heavily in 1948.

The reason that the drawn-out investigation is important is that it leads to questions as to why Maclean was so calmly reinstated at the American desk of the Foreign Office in November 1950. (Burgess’s Personal File shows that a few ‘diplomats’ interviewed after the escape expressed their amazement that Maclean had been appointed to such a prominent position so soon after his apparent ‘breakdown’.) This is where Hamrick’s theory that Maclean and Burgess were deliberately appointed to prominent positions, despite their erratic behaviour, comes in. One does not have to accept Hamrick’s more extreme hypothesis that they were part of an ingenious scheme to send disinformation to the Soviets, and thus the fact of their detection had to remain concealed. It may have been that the restoration of their careers reflected a need to gain solid evidence of their treachery with a hope, perhaps, for Burgess to entrap Philby through his proximity in Washington, and for Maclean to make fresh contact with his Soviet controllers in London. The evidence from VENONA would be unavailable in any prosecution, because of the security implications, and the cryptographic aspects would mean that it would not, in any case, hold up in a court of law.

One has to wonder at the possible dangers of knowingly implanting such viruses in the heart of the US capital, but the idea is not completely absurd. I record again that Roger Makins was asked to keep an eye on Maclean when he rejoined the Foreign Office in November 1950, and that he admitted that he had had to find a job for Maclean that was important enough not to raise his suspicions. The recent release of the record of interviews carried out by Dick White with Philby in June 1951 proves that Burgess was also under suspicion when he left for the USA in the autumn of 1950. As I showed in last month’s report, Philby had been considered guilty by de la Mare in the Home Office, and Dick White’s dossier compiled for the FBI in June of 1951 very quickly added the seventh point that Philby was suspected of assisting in the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean.

Makins admitted in writing that he had withheld top-secret documents from Maclean on his re-installation (see sn. 613 in FCO 158/9), which was a bizarre move. If the Foreign Office thought that his placement might be a danger, they should never have approved his appointment. If Maclean detected that he was not being shown memoranda that he would customarily have seen, it would have put him on his guard. If a serious attempt to entrap him was being considered, however, he should have been fed with spurious (i.e. authentic, but not genuine, memoranda), crafted to include apparently vital information that would actually be harmless, so that Maclean might have considered pausing his passivity, and reaching out to Modin. Yet the whole exercise achieved nothing, and turned out to be pointless. Moreover, Makins showed a typical bureaucrat’s evasiveness in his testimony, confirming that he had been withholding ‘papers with an important security rating from him’ since Maclean’s appointment (as he told Glees and others), but then disavowing responsibility ‘as soon as Maclean became the suspect’ – a date he does not identify, but was presumably, for purposes of maintaining the fiction, in April 1951.

Thus MI5 and the Foreign Office may have wanted to keep a lid on the HOMER discovery as long as possible, since they would eventually be pushed into conducting an intensive interrogation. That exercise would either fail to get a confession, and the prosecution would have to be abandoned (as later happened with Philby), or would be successful, and the authorities would be forced to go to a messy trial that would bring all manner of nasty skeletons out of the closet. That was something that Philby had internalized, and which he later explained to his masters in Moscow. It is this background that encourages the notion that the group of insiders managing the project may have viewed the abscondment of its three suspects to Moscow as the cleanest exit strategy. After all, Dick White had even suggested to Andrew Boyle that Guy Liddell might have been involved with such a scheme.

It is as if the decision to have Morrison sign the paperwork to detain and interrogate Maclean was taken only when the escape plans had been finalized, rather than vice versa.

- 3. Guy Burgess’s Recall: Was it part of the plan to facilitate the escape? Or was Burgess’s return to London merely a fortuitous event that worked in Moscow’s favour?

It is extraordinary how many commentators have continued to assert that Philby managed to effectuate Burgess’s return to London – in a hasty, manner, moreover – when the following facts conspire against such an account. First of all, the timing: Burgess’s speeding offences occurred at the beginning of March, before the HOMER shortlist had officially been reduced. If Philby had been serious about wanting Maclean exfiltrated, he would have acted much earlier, and he would have found some way to get a message, through Makayev, to his Moscow bosses – as indeed he did. Yet the events moved so slowly that the initiative would have been flawed, in any case. The Ambassador was away, and did not return until the end of March, by which time Philby was already documenting further pointers towards Maclean in an attempt to save himself. Second, Burgess’s behaviour was not that of a man on a mission. He was not ordered home until April 14, but, even then, after vigorously protesting his punishment, he did not hurry. In early April, he had found time to greet his mother who was paying him a visit: one might imagine that, if he had really wanted to return to London quickly, he would have taken leave and accompanied her back to the UK. If the pair wanted to grasp at an opportunity for urgency, they spectacularly missed it.

The Foreign Office archival material (FCO 158/182) shows that Ambassador Franks had just returned from the UK when he announced to Burgess that he was being sent home. This was not presented as a serious disciplinary matter, however, and the incidents of the speeding offences were given as only of secondary importance in the recommendation that Franks had made to the Chief Clerk in the Foreign Office. Burgess was described as a poor fit in the office, and criticized for putting in shoddy and superficial work, which represents a rather bizarre explanation for his effectively being sacked, given his notorious examples of gross misbehaviour both before he was sent to Washington, and thereafter. Material in FCO 158/189 proves that Burgess was moved to Washington despite having been subject to a disciplinary hearing already, so that he would be able to work less conspicuously in a larger environment, and an eye could be kept on him. The indulgence shown towards him is dumbfounding. I do not exclude the possibility that Burgess’s future was discussed by Franks and his Foreign Office colleagues during the Ambassador’s fortnight in London at the end of March.

When Burgess did arrive, at the beginning of May, he immediately came under MI5’s eye. The Security Service was ready and waiting for him. This surveillance intensified when he determined Maclean’s address, contacted him, and started meeting him. An outwardly innocent acquaintanceship between two FO colleagues could pass muster, and it allowed Modin to restrict his clandestine contacts with Blunt, who obviously did not want to be seen hobnobbing with Maclean. Burgess thus became a natural middleman for negotiations between, on the one hand, the residency and Blunt, and, on the other, Maclean. His presence therefore allowed for a slightly more careful approach to developing an exfiltration plan: at the same time, however, his reckless and ostentatious behaviour over the two weeks leading up to May 25 could have jeopardized the exercise.

This portion of the project has been treated very superficially in the literature. For instance, the most thorough study of Burgess, The Spy Who Knew Everyone, by Purvis and Hulbert, relying mainly on what Burgess told Driberg, and what Philby wrote, has Philby and Burgess planning the details in New York the night before he set sail (April 30). They echo Philby’s statement that Burgess ‘was to meet a Soviet contact on arrival and give him a full briefing’, without any indication as to how such a meeting could be set up, or assessing how risky such an undertaking might be. Yet they go on, incongruously, to say that Burgess would then make contact with Maclean, who was expected to be under surveillance, and that Burgess concluded that a go-between should deliver the warning, and that he chose Blunt. But that is nonsensical. Blunt needed Burgess because he did not want to be seen in the company of Maclean, and Burgess had valid reasons for seeking Maclean out. Blunt was the go-between between Maclean and Modin, since he was not under surveillance. Blunt’s telephone number was discovered in Maclean’s office address-book after he disappeared, but Blunt probably did not know how to contact Maclean after his return from Cairo. Burgess had to track Maclean down on his arrival.

The authors then compound their mess by quoting from Blunt’s unpublished memoir held by the British Library. Now Blunt reports on ‘the first meeting between Guy and his Russian contact’, where discussions focused purely on Maclean’s escape. Blunt then follows up: “ . . at a later stage I remember Guy coming to see me at Portman Square . . . those in control of his contact had decided that he should go with Donald . . .”. It is an utterly sophistical display by Blunt, and Purvis and Hulbert have been taken in by it. At least Andrew Lownie accepted that it was Blunt who met Modin regularly to supervise the project, although he also records that Burgess had the meeting with Modin where he was informed that he would be joining his friend in the exfiltration. (That must be the occasion described by Modin, where he, Blunt and Burgess met – an event that the Watchers somehow managed to miss, which is disturbing in itself.)

In fact Carey-Foster, the Foreign Office’s Security Officer, later (in February 1956) admitted to Patrick Dean, the new deputy Under-Secretary of State, that he had been remiss in not taking Burgess more seriously in May 1951 (sn. 619z, KV 2/4112). He said that he had a hunch that Burgess had decided that he had better get back to London ‘to be on the spot when the time came’, as if he had gained an early insight that the project was ‘getting hot’. MI5 had informed him that Burgess and Maclean were in constant contact, but he did nothing (an observation that clashes with what Reilly later claimed: see Item 6 below). Yet there can be seen a high degree of ingenuousness in his self-flagellation. He added that he did not know whether Philby had been involved, and told Dean that he should have pressed for surveillance on Burgess. By then Philby had been clearly implicated, and Burgess had indeed come under surveillance as soon as he landed in 1951. Carey-Foster also claimed to Dean that MI5 ‘continued to deny that he had warned them’. It appears to me that Carey-Foster was trying to conceal the true story from Dean.

When Burgess and Maclean at last made their public statement in Moscow in February 1956, part of Maclean’s text ran as follows: “His [DM’s] telephones in his office and private house were used as microphones. Plain clothes policemen followed him wherever he went, and one of his colleagues was put up to act as provocateur. Maclean therefore decided to come to the Soviet Union to do whatever he could to further understanding between East and West, from there. The difficulty of leaving the country while being tailed by the police was solved by a meeting with Burgess shortly after the latter’s return from the Washington Embassy to London. The latter not only agreed to make arrangements for the journey but to come too.”

The bottom line? Writers can pluck anecdotes from the highly unreliable memoirs of Philby, Burgess, Blunt, Modin, Rees and others and hope that they somehow hang together, but it simply does not work. Burgess’s presence enabled the MVD’s plans to be communicated regularly to Maclean, which circumvented what would otherwise have been a fascinating challenge for Modin and Blunt. Yet Burgess’s exaggerated behaviour inevitably made him an accomplice and fellow-absconder, and his connection with Philby should have defined a similar fate for his friend.

- 4. Communications with Moscow: Was Philby able to update his masters in Moscow, and receive instructions from them? When was Maclean in contact with Modin in London?

Philby was without direct contact with any Moscow representative for most of his time in Washington. Macintyre’s account is not reliable. We know that Makayev arrived in New York in the spring of 1950, and that Burgess, after his arrival in September of that year, had occasional meetings with Makayev, acting as a courier for Philby. For a while, I believed that we had no precise dates for his visits to New York, but Donald’s younger brother, Alan, proved very helpful in Jim Skardon’s inquiries. Burgess’s pretext for going to New York was to visit Alan, so that might also have been a hitherto undeclared channel for messages to get to Donald, since communications from Alan to his brother would not have been intercepted. Alan gave a detailed list of Burgess’s visits (visible at KV 2/4104, sn. 195z), declaring that Burgess ‘spent at least two weekends in August or early September 1950, the weekend of November 11/12th or 4/5th, and a few weekends in October, November and December.’ In 1951 Alan thought that Burgess made about five visits to New York during January, February and March. We might assume that most, if not all, of Burgess’s visits to New York during this period (September 1950-April 1951) included a meeting with Makayev. Thus it would seem reasonable to conclude that Moscow, and the London residency, received warnings about the net closing in on Maclean in early 1951. Makayev was an unreliable agent, however, and slipped up badly when tasked with leaving information and cash at a dead-drop to aid Philby’s possible escape.

The fact that Maclean had no contact with his handler in London appears to be reliable. He had requested to be relieved of his espionage duties after his breakdown, and Modin does not seem to have made any further approach. Modin’s claims that Maclean provided much useful information after his return to the UK in the early summer of 1950, and used Burgess as a courier when he returned to work in November, are obviously bogus, since Burgess was in Washington by then. Maclean’s lack of utility as a spy since his return to work would tend to undermine Philby’s claim that Moscow deemed that he was too valuable to be exfiltrated, and that it wanted to keep him in place for a while. The suggestion that Moscow did not want Modin to reach out to him indicates that it was regarded as too dangerous. When Maclean had his first meeting with Burgess, after Burgess discovered where he lived, and then contacted him at the Foreign Office, Maclean claimed that he was being watched, but it appears that Maclean was not informed of the immediate threat to him until then.

Yet he may have been on tenterhooks ever since returning from Cairo, if Philby had managed to alert him to the overall threat, and his irresponsible and erratic behaviour in Cairo would bear a more rational explanation. That would also explain his resolve not to pass on any more secrets when he returned to the Foreign Office. I raise again the obvious question: why would Philby and Burgess not have used the safe channel of Alan Maclean in New York to send messages to Donald? It was obviously more difficult for Philby to use Alan Maclean as a (probably innocent) intermediary until Burgess arrived, but in late 1949 or early 1950 he could have written to Alan with an enclosure to be passed on, perhaps in code. Tom Bower (White’s biographer) claims that Maclean’s mail would have been intercepted, but that sounds absurd. No British authority would have been able to have private mail sent from New York to Cairo opened and read, and such surveillance on Maclean did not start in England until April 1951.

- 5. Burgess’s Visit to Sonning: When was it set up? Was its purpose to discuss Burgess’ future journalistic career? Was it to verify that he would not betray Burgess, Blunt, and Maclean? Or was it something else?

Even though Goronwy Rees is the only major witness to Burgess’s visit, and he tried to use it to his advantage in his memoir, there is no doubt that it did take place. The Watchers were ready to observe Blunt and Hewit meeting Burgess at Waterloo Station on May 7, and while their records show that their knowledge of Burgess’s visiting Sonning the same day, after lunch with Blunt, is dependent on Rees’s signed statement, we have confirmation from Rees’s daughter, Jenny. She is the eldest of the Rees children, and remembers the visit clearly, a girl of nine at the time. Furthermore, her recall was abetted by what her aunt Mary told her, Margie Rees’s sister having been present when the Burgess visit occurred. She had been instructed to watch Rees and Burgess surreptitiously, and eavesdrop on their conversations, since Goronwy and Margie, after receiving Guy’s letters of self-invitation from the USA, had awaited his arrival with some trepidation. Margie was worried that Guy would lead her husband into excessive drinking (a rather vacuous concern, one might say, as Goronwy was quite capable of overindulging without any external stimulus).

Rees’s explanation of the visit was that Burgess wanted to discuss his forced change of career into journalism, and that he had an article for Rees to review. This seems a very artificial scenario, and it hardly warranted the priority and importance that Burgess had obviously granted it. From what Burgess and Philby themselves wrote, his first task – after exchanging news with Blunt – was to contact Maclean. Nor was it probable, in the fashion that Chapman proposed, that Burgess’s mission was to gain Rees’s agreement to keep silent over the planned exfiltration of Maclean. Arousing Rees’s interest at a time when Maclean’s state of mind had not been determined, and no specific plan for his escape was in the offing, would have been a reckless move of endangerment. What would have happened if Rees had bluntly deplored the conspiracy and proposed manœuvres, and declared his resolve to inform the authorities? Burgess could hardly have bumped off his pal on the spot. He would have done better to carry out his project without bringing in Rees at all.

Peter Wright interviewed David Footman in 1965, then in comfortable retirement at St Antony’s College, (sn. 385z in KV 2/4608), alongside an officer whose name has been redacted, but is almost certainly Evelyn McBarnet. Wright had recently been told by Mrs Rees that Goronwy considered Footman a more dangerous spy than Kim Philby, even, which makes the format of this interrogation even more bizarre. Wright explained his puzzlement at Burgess’s haste in seeing Rees before he even contacted Maclean, and he tried to draw Footman out on the matter of the Burgess visit to Sonning, and the subsequent phone calls:

It makes you think that he went to see GORONWY to enlist GORONWY’s aid, maybe GORONWY refused it and – mavbe GORONWY and MARGIE between them refused it and are denying the story ever since simply because he defected afterwards and they feel, you know, that they could have stopped it if they’d come clean, or , something like that – or, that GUY told them about DONALD this time and –

Wright was groping towards the right questions, but overlooked the fact that Burgess had set up the Sonning visit well ahead of time. Moreover, between them, McBarnet and Wright botch the interrogation, talking too much, interrupting each other, and not staying silent when Footman should have been encouraged to explain himself more fully as to why Rees had called him to unload his thoughts on Burgess. Footman even poses the question himself: ‘Why did he ring me up’? It constitutes a feeble show of tradecraft.

One reason why such an approach by Burgess would have been risky is that Rees was at that time working, if only part-time, for MI6, under his friend Footman. Thus, unless he was still [?] a penetration agent, he would be working for the opposition. Moreover, Burgess would have known about Rees’s employment. We learn from Guy Liddell’s Diaries that in 1948 Liddell had been engaged with Rees, Burgess – and Blunt, even – in an unlikely cabal for discussions on Borodin and bacteriological warfare secrets (see https://coldspur.com/biological-espionage-the-hidden-dimension/ ). A more recent inspection of the Rees archive that I have undertaken shows that, in March-April 1949, Rees behaved in a disreputable fashion, without authorization revealing to his fellow director at Bennetts and Shears the fact that Borodin had defected. The firm wanted to recruit Borodin (on whose behalf MI5 was undertaking efforts to have him relocated for safety purposes to Canada) to assist in developing penicillin plant facilities abroad, since Borodin’s mentor Ernest Chain had turned out to be unreliable and very expensive. Robertson of MI5 (B2a) was more cautious than Deputy Director-General Liddell about the opportunity. An item in the Burgess file (sn. 123b, KV 2/4102) reports that an MP named Edelmann had written to the Foreign Office claiming that Rees had set up a trading concern with Russia soon after the war.

Moreover, at a conference held for MI5 and MI6 officers at Worcester College, Oxford, as late as August 1949, Burgess (despite not being a member of either service) was a speaker alongside Borodin, and Rees and Footman were also in attendance (as Burgess’s letter from Moscow, and notes written by MI5 officers in his Personal file KV 2/4116 confirm). Since the Provost of Worcester College was John Masterman, the supervisor of the wartime Double-Cross operation, it is probable that one of the themes of the conference was the management of passing disinformation to the enemy. The fact that Burgess was invited to attend such a sensitive and confidential gathering suggests that he was in good standing at the time. (He was, in fact, invited by Footman.) While it is astonishing, given the security considerations, that Borodin was put on display in this manner, another remarkable aspect of this gathering was that Rees, Footman and Burgess were all noted as heckling the unfortunate Borodin, which represents another signal of Rees’s hypocrisy and questionable loyalties. I reported recently on the fact that Robertson had accused Rees, in June 1951, of helping the Soviets with their penicillin projects: that may have been a ‘legitimate’ disinformation exercise, into which Robertson had not been indoctrinated, but Rees was obviously following a rather precarious line.

The conclusion I come to is that Burgess still trusted Rees implicitly. He could have been using him as a source of information on the status of the HOMER investigation, and, specifically, what interest the security services had in him. In this respect, the previous connection to Liddell, when Burgess had worked with Rees and Blunt on the Borodin project, is very pertinent. Of course, Blunt, with his ready access to Liddell, could have told him more than Rees ever knew, but Burgess would not have known that at the time he wrote to Rees. Yet Burgess met Rees again (though Rees denied it), and was in telephone contact with him, so there must have been something more that his friend could provide him with. It is superficially difficult to imagine that Rees’s dealings with Burgess could have been approved by the authorities, which is why Rees had to offer an alternative explanation, fudge the facts, and highlight his own breakthrough conclusions in an attempt to save his own skin. His involvement with Burgess before his friend left for Washington at the end of July, 1950 belies how he described the relationship in his memoir. A more sinister interpretation, given that we now know that Burgess was under suspicion before he arrived in the UK [see below], is that Rees’s bosses were using him as an intermediary and informant to learn more about Burgess’s plans, which would have imposed additional mental strain on the weak-willed Rees.

- 6. Surveillance of Burgess and Maclean: Was Burgess also under suspicion? What was the nature of the surveillance of Maclean? Why was it so obvious, and what were its goals? What was the reality of the telephone surveillance installed in his house?

Dick White twice indicated to his biographer that Burgess had not been under any suspicion until he absconded, and thus there would have been no reason to watch him. In his Diaries, Liddell iterated this belief when he briefed Director-General Sillitoe on May 30, claiming that there was no special reason why Burgess’s meetings with Maclean should have been deemed suspicious. Yet that opinion is not supported by later minutes provided by Talbot de Malahide *, as recorded by Purvis and Hulbert, which indicate that Burgess had been under suspicion before his arrival. In Too Secret Too Long Chapman Pincher asserted that Burgess was ‘under such deep suspicion’ before he even went to Washington that an officer was sent out to keep an eye on him. A statement made by White to Philby on June 16, 1951 – only recently made available at KV 2/4723 – would appear to confirm that Burgess was under suspicion before he went to the USA, because of a garbled reference to Frederick Kuh, the American journalist to whom Burgess had been passing information that Kuh forwarded to the Soviets. Memoranda posted in the FCO archive (sn. 656, FCO 158/9) indicate that several important members of Chancery (Marten, Jellicoe, Greenhill) in the Washington Embassy deemed Burgess’s behaviour so outrageous that they sought an opportunity to pool their thoughts with the MI5 representative, but were ignored. That suggests again that Burgess was being tolerated for deeper reasons.

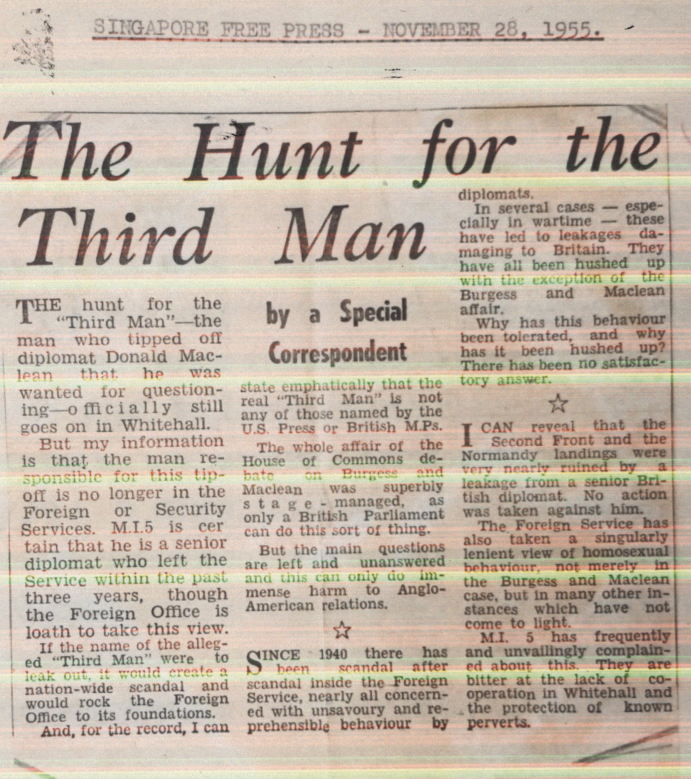

[* I covered some questions concerning de Malahide in my February analysis. In Undercover: Two Secret Lives, by Tony Scotland, issued in October 2024, the author states that de Malahide, in the Foreign Office, may have been a spy alongside his friends Burgess and Maclean. The book is not yet available in the United States, and amazon.uk informed me that the distributor in the UK could not send it here. Thanks to my enterprising colleague Andrew Malec, I have been able to arrange direct shipment. I thus have not yet inspected Scotland’s assertions, but I shall do as soon as the book arrives. It may provide a useful pointer to the identity of a ‘Sixth Man’ – or alternative ‘Third Man’: see illustration at the head of this piece – in the Foreign Office.]

This contrary theory is also borne out by the fact that the Watchers obviously knew about Burgess’s arrival time at Southampton (White also declaring, very absurdly, that he had not even been aware that Burgess was on his way), and that they were ready to see Blunt and Hewit greet him at Waterloo Station. That encounter is probably a more reliable event than that of Blunt’s welcoming him at Southampton Docks. Yet it immediately poses the question: how did the Watchers learn of Burgess’s itinerary, and why were they already keeping an eye on him when he met Blunt and Hewit? That scenario undermines the account provided by Carey-Foster that he advised MI5, a few days after his arrival, that it should surveil Burgess as well, after he was seen in Maclean’s company. (Lownie cites this observation from Patrick Reilly’s unpublished memoir at the Bodleian, but Reilly is not a trustworthy witness.) Had Blunt informed Liddell of the particulars of Burgess’s homecoming? It is difficult to identify anyone else who had the knowledge and the opportunity.

The surveillance of Burgess thus poses something of a mystery. In his confusing chapter ‘BARCLAY and CURZON’, in Cold War Spymaster, Nigel West asserts that, because Burgess ‘had never been a suspect’ (a fact we know now to be untrue), reconstructing Burgess’s movements posed more of a challenge. He writes that Burgess had been spotted meeting Maclean ‘several times in Pall Mall’ by the Watchers, but that MI5 had had to resort to rely on interviews of Burgess’s circle to re-create his movements. I doubt whether that tells the whole story: when Burgess travelled into the country, the Watchers would not have followed him, but it seems they kept a closer eye on him in London. Since Maclean was closely watched, encounters between Burgess and Maclean would have been recorded: KV 6/145 indicates that they met solely on May 15, 22, 23 and 24 (which could barely count as ‘several’). Burgess’s movements independent of Maclean are sometimes recorded, even when he was alone, which could not have been derived from third parties. KV 6/145 provides an excellent summary of these activities. My assumption is that these are by default first-hand observations, since alternative sources (e.g. Rees, Cyril Connolly) are annotated in the notes of the file. Thus Burgess’s booking of his rental car, and his reservation of the berths on the Falaise, on the morning of May 25, are provocatively presented as being noticed at the time. That has enormous implications, as far as the indolence of MI5 in following the trail is concerned.

Philby’s alleged instruction to Burgess, before the latter left for the United Kingdom, that he should not ‘go too’, indicates that Philby did not believe that Burgess was under suspicion at the time, and that he would be able to contact Maclean without becoming included in the investigation. If Maclean alone were exfiltrated, Philby might have remained intact, but his close associations with Burgess would immediately draw deeper suspicions on him. This was a serious misjudgment.

As for Maclean, we have a very comprehensive account of the level of surveillance in the KV 2/4140 series. It was very intensive, and must have been quite obvious to the subject. What is more, despite the claims made by some accounts that it did not extend beyond the London railway termini, they are not true. Donald and Melinda are observed driving to the station on May 11, and Donald is recorded at arriving at Warlingham Station [sic: actually ‘Woldingham’] at 5.55 pm later that day (indicating that he took the slow train, and was picked up at the station). On another occasion, Maclean’s parking of his car at Oxted station is noted, as well as shopping expeditions to that town with Melinda (May 12). One of his travelling companions was traced to the Sussex town of Hayward’s Heath when Maclean wanted to buy a new car. Furthermore, one report even records the exact time he arrived at his home in Tatsfield, which debunks the claim that surveillance would have been too obvious in the countryside.

What was the purpose of such surveillance? Ostensibly, it must have been to ascertain who Maclean’s contacts were, with the hope, perhaps, of catching him red-handed passing over some document to a cut-out, or even directly to a member of the Soviet residency, as that would solely provide the evidence that would be needed for a conviction if no confession were extractable. Yet the Watchers were so heavy-handed and obvious that Maclean quickly realized what was going on. In any event, he had not been in touch with any Soviet controller since rejoining the Foreign Office after his convalescence. A more likely explanation is that it constituted more of a campaign of fear-induction – to exploit his already tortured existence to provoke him to perform something desperate, and maybe to conclude that he should confess to get the whole torment out of his system. Or perhaps even to make him think he should abscond . . . .

The telephone surveillance began on April 23, although Maclean’s name had already come up in calls made by Peter Floud, and monitored by the General Post Office, earlier that month. The archive indicates that a special telephone was installed on May 11 at the Macleans’ house, so that conversations taking place could be relayed and recorded. Again, Donald and Melinda must have realized what was happening when the technicians arrived, no doubt needing to ‘inspect a fault’. Thus they would have been guarded – or deliberately misleading – in their talk thereafter, whether on the phone or when inactive. That did not prevent Maclean from calling Burgess from home on Monday May 14 (Whit Monday, and thus a public holiday). Their conversation should have been very revealing – but maybe it was a ruse. That would play into the scenario suggested by Nigel West, who described Burgess’s inventive countermeasures to frustrate the Watchers.

One vital aspect of the surveillance concerns the leaking of the news, via the defector Petrov, in April 1954, that Burgess and Maclean had been able to inform their handlers at the Soviet Embassy that they were being watched. This revelation may not have seemed very striking to the general public, or even to the Press, but it must have been highly alarming to MI5. Since close surveillance had been kept on the pair since Burgess’s arrival (and before that, on Maclean), the Watchers would have picked up any contact with members of the Embassy. So how had they communicated? Through an intermediary? They had a long list of characters with whom Burgess had socialized, including Anthony Blunt, who by some accounts was the ‘tall figure’ seen with Burgess in the early evening of May 25. (Later, in February 1952, MI5 believed that the figure was Bernard Miller, who had since been interrogated by the FBI.) Dick White had already suggested, in August 1951, that Blunt be given immunity from prosecution for a full confession. His meetings with Burgess in May 1951 (especially since he convened regularly with Guy Liddell at that time) must have given White & Co. some severe headaches.

Of course, the fresh disclosures from Tony Scotland [see above] may throw further tasty ingredients into the mix. (Readers may recall, from last February’s coldspur, a somewhat enigmatic reference by Richard Davenport-Hines to an anecdote from Chapman Pincher indicating that de Malahide had alerted Burgess.) If de Malahide had been aware of what was happening with Maclean, even if he were only a Soviet sympathizer (i.e. an ‘agent of influence’ rather than a penetration agent) might he have warned him? And did Maclean know of de Malahide’s role? Was de Malahide in touch with the Soviet Embassy at any time? (Modin did not name him.) Furthermore, Scotland has informed me that de Malahide was investigated and interviewed shortly after the abscondment, but that the transcript of that interview has not been released, despite Andrew Lownie’s application through a Freedom of Information request to have it declassified. Why was de Malahide investigated? And why, unlike Footman, was he kept on? It constitutes a fascinating project to pursue. The continued secrecy over these seventy-year-old goings-on is absurd, and very incriminating.

In any event, the various accounts of these encounters pose further challenges. As I described in Section 3 above, Purvis and Hulbert get into knots presenting unreconciled versions of the meetings arranged with Modin. Burgess claimed that he decided to deal with Modin directly, bypassing Blunt. Modin said he met Burgess and Blunt on May 10. Blunt in his memoir claims that Burgess had at least two meetings with ‘his contact’, to which Blunt was not invited, as Burgess updated him afterwards. Moreover, Burgess’s meetings with Modin were unobserved by the Watchers. That is what caused the later ado in MI5 in 1954, when Petrov reported that Burgess and Maclean had alerted their contacts, as Robertson and Mitchell could not imagine that either of them would have succeeded in keeping unnoticed a clandestine meeting with a Soviet official, even if they had dared to. After all, that was the key objective of the surveillance – to catch them in flagrante. Either they were all lying to some extent, or the Watchers were carrying out a very selective observation on Burgess, astutely being around when he arrived at Waterloo Station, and when he had his meetings with Maclean, but overlooking some other activities. A third explanation is that Robertson in MI5 assumed that the surveillance of Burgess was comprehensive in London, but that he had not been told the full story by Dick White.

In that respect, I note one final highly controversial item. Much later, after the ‘Third Man’ debacle, on November 11, 1955, Skardon (now in A4) send a note to Reed (now D1a) concerning the surveillance of Burgess and Maclean on May 24, 1951 (sn. 612a, in KV 2/4112). Burgess had been noticed as being in an ‘agitated state’, and Skardon completes his memorandum with the following cryptic observation (including an errant comma):

It is not felt that we should elaborate further on this unhappy demeanor of BURGESS or illustrate the circumstances which existed then, as all A.4. officers engaged on this case, realised this condition of BURGESS’s but had been instructed to take no further interest in him.

Seriously? That is not what the comprehensive record at sn. 607a in KV 6/145 states. I have no idea what that entry means, but might surveillance have been passed over to an elite team for the final twenty-four hours? Had some of Burgess’s activities been condoned, like Blunt’s, perhaps? Was it a very selective surveillance?

- 7. The Defection of Burgess: Why did Burgess have to accompany Maclean? Was it his own decision? Or was he ordered to?

“To hell with the Foreign Office, Moscow is the place where I would like to be!” (Guy Burgess, at dinner hosted by Moura Budberg, May 13, 1951)

The notion that Burgess at the outset made a sober, voluntary decision to accompany Maclean (as declared by Burgess himself, and echoed by Modin) barely merits consideration. It is much more likely that he became sucked into a maelstrom from which he could not escape. He was probably misled by the Soviets, who encouraged his assistance in helping Maclean on his path by promising him that he could return at some stage during the journey, or even after he had arrived in Moscow. But the idea that he might be a stable guide for Maclean in Paris, where (so Modin claimed) Maclean feared that he might be tempted by nostalgia to hang around, exploring his old haunts, is plainly ludicrous. The MVD would not have allowed that to happen, and for anyone to think that Burgess was the appropriate figure to keep Maclean on the straight and narrow would be a serious delusion. Moreover, if Burgess had been able to return, he would have to face the inevitable music, and he might have betrayed further members of the network. How Burgess, even under stress, could have contemplated that he could accomplish a graceful re-landing on British soil, and continue his sybaritic life there, is hard to imagine.

There is also evidence that Maclean was by now the more level-headed of the pair. The reports of his mental turmoil may have been overstated. Once the die was cast, he may have calmly resigned himself to the inevitability of spending his remaining years in Moscow, and simply prepared himself as coolly as possible for the departure day. Certainly his demeanour in his last social engagements, especially that with Anthony Blake at the Reform Club on May 24, as reported by Aldrich and Philipps, indicate that he was able to conceal any turmoil that may have been oppressing his mind. Moreover, he had his wife and family to consider, and the effect it would have on Melinda’s confinement, and his sons’ morale. Thus it was Burgess who was more likely than a ‘desperate’ Maclean to put the whole project at risk.

Such a theory is reinforced by a remarkable item that the FBI has placed on its electronic archive. It constitutes a letter from an ‘old friend’ of Maclean’s, sent to the American Ambassador. The text is a message from Maclean about his intentions of fulfilling his duties to his country by taking a message directly to Stalin, and that he has convinced his friend Burgess of the correctness of his decision. By June 6, he writes, they will ‘have crossed the Iron Curtain unto the Free World’. A vital hint to the identity of the old friend is given by the information that Maclean passed the message on May 24. The only engagement Maclean is noted as having on that day was with his friend of long standing, Anthony Blake. Roland Phillips records, using KV 2/4150, that Blake told his MI5 interlocutors that Maclean was in good spirits that day, and had expressed no intentions of running away. The first claim was true, but Blake out of loyalty obviously deceived MI5 on the second point. The letter was forwarded to the FBI on June 12, 1951.

It is much more probable that Moscow decided, once that Burgess was abetting the project and carrying out some of the main initiatives, that they had better ‘rescue’ both their agents. Maclean was busted, and of no further use. Burgess was emotionally stressed, and addicted to medication and alcohol, so had thus also lost any value. His erratic behaviour no longer served as a cover for reprehensible activity, and thus he had to be exfiltrated as well. Philby needed to be protected: as we know, Blunt was also ordered to defect, but declined, and got away with it, although Moscow could not have been happy with his decision. Their orders were not normally defied. Moreover, there had been a possibility that Philby would defect as well, as if Moscow feared that he would inevitably be linked with the others. As it happened, Makayev erred by failing to provide Philby with the cash to fund his escape. For whatever reason, Philby decided to brazen it out.

If, however, it was part of the plan by Dick White and his cabal to abet the escape of MacLean, and discreetly encourage it, packaging Burgess in the arrangement as well would have been a very obvious requirement. Burgess may have been pushed.

- 8. Burgess’s Behaviour: Why did Burgess socialize so promiscuously in the weeks before his defection? Why did he draw attention to the crisis so ostentatiously, to so many?

If the defectors had wanted to keep their activities discreet in the ten days before they departed, Burgess’s behaviour would clearly have undermined such an objective. Apart from all his noted social gatherings, lunches, dinners, country visits, etc. with such as Peter Pollock, the Harrises, David Footman, even the Headmaster of Eton, Robert Birley, he went out of his way to draw attention that something was afoot. He introduced his friend Bernard Miller to the talkative and immoral Hewit, and he then told Hewit that he was going away for the weekend to help a friend in need. He openly purchased tickets on the Falaise (either on the 24th or the morning of the 25th), presumably in the knowledge that his activity might be monitored. He flamboyantly hired a car on the Friday, rather weakly trying to drop hints that he was driving north, when a more subtle way of making the journey could have been to use Maclean’s Humber for the getaway. He made the absurd late call to Margie Rees from the Reform Club, announcing his intentions of doing something dramatic, dismissing any need for privacy, and then did not pay for the call, thus having his failure published for all club members (and journalists) to see. Instead of arriving at Southampton Docks in good time, and leaving the car in a secluded spot, he left it in full view, and gave a melodramatic shout as he and Maclean boarded at the last minute.

Apart from the fact that one might have expected MI5 and the Watchers to suspect that something untoward was afoot (after all, preventing the escape of the duo was presumably part of their mission, and, as we now know, Burgess was also under strong suspicion at this time), Burgess’s behaviour might indicate that he nurtured a half-realized wish to make the project fail. After all, what was there to lose, and he might have been able to brazen it out because of what he knew, and how he had been let off beforehand. Another motivation might have been to cause as much embarrassment as possible to all those left behind – not only those whom he saw as enemies of his cause, such as the security officers in MI5, but those with whom he had some sympathies, such as Rees, Blunt, Footman, and Liddell, even. The only thing that may have held him back from blowing the operation completely might have been the fear that, if he let down the MVD, and disobeyed its orders, he might be disposed of in the conventional murderous ways of the RIS.

- 9. The Role of the MVD: How authoritative was the MVD in making decisions? How much was left to Blunt and Burgess?

One would expect the MVD, when apprised of the facts, to act decisively and quickly. That Maclean needed to be exfiltrated was a decision it surely made soon after Burgess arrived in London. As soon as Burgess had his significant meeting with Maclean on May 15, and Moscow was alerted to the crisis, the order was given to Maclean that he had to defect. According to the Mitrokhin archive, Burgess was ordered to accompany him to Moscow, although, at this stage, the planners did not have any clear idea how the exfiltration would take place. Anything from deploying submarines off the coast of England to drugging their victims and smuggling them overseas was surely considered, as Kislitsyn suggested. According to Modin, it was Blunt who came up with the idea of a weekend cruise ship to France, a week before the eventual date, and Moscow then approved the plan. (Philipps gives it as late as May 23, which would have made sharing logistics with Moscow rather difficult.) That option could thus not have been invoked any earlier. At that stage, Moscow Centre must have deployed its full resources to arrange visas and passports, and the necessary couriers to help the pair get from St. Malo to Prague.

Given that Burgess must have protested at first about his forced abscondment, Moscow used deception, knowing perhaps that they had no other choice. Yet promising Burgess that he might at some stage during the journey simply turn round required a measure of gullibility in the reluctant escapee. It must have become obvious to him during the last week that there was no way back. All through this, Blunt played a minor role as deliverer of messages – far from the authoritative organizer who belittled his minder as portrayed by Chapman. He may well have had the idea of the Falaise cruise (that idea has been ascribed to Modin, even), but the suggestion that Modin came to it by spotting an advertisement in a travel agent’s window, as Bower reported in The Perfect English Spy, seems a little too coincidental. Even the booking of the tickets by Burgess as late as the Thursday, May 24, (as reported by Modin and Lownie) seems cutting it fine, but maybe he feared detection if a delay were built in to the system. Yet the Watchers confidently reported that he acquired them only on the morning of May 25, the day of the escape.

- 10. The Interrogation: Why did the authorities dither and delay? On what date was it planned to haul Maclean in? Did this event change? Why were Foreign Office mandarins so insistent that it was about to happen on May 28?

Irrespective of the months, even years, behind the narrowing-down of the identity of HOMER to a confident belief that it was Maclean, the final weeks were riddled with hesitations, and some unconvincing displays of sensitivities concerning security – mostly involving concerns about the FBI. If one can trust the documents of the case as deposited in KV 6/140-145 (and it is possible that false records may have been inserted), the sequence of events after Gore-Booth was eliminated from the reckoning on April 19 through the verification of the suspect’s visits to New York appears to be as follows:

April 23: Surveillance of Maclean starts. Carey-Foster of FO & Robertson of MI5 inform Vivian of MI6.

May 1: Patterson in Washington reports demands for action from FBI.

May 4: FO & MI5 discuss whether to inform NSA at Arlington & FBI of suspicions.

May 4: Meeting resolves that Maclean should be interrogated within a fortnight.

May 5: FO expresses concern that FBI will leak information to other US departments (such as State). Robertson advises Patterson to keep silent.

May 7: FBI is still thinking in terms of other candidates.

May 9: FO is torn over waiting for Maclean’s arrest before telling the FBI.

May 15: Schedule sets June 4 as day for informing FBI. Makins and Mackenzie in Washington want to inform Hoover after the interrogation. Interrogation is then set for June 8. GCHQ promises not to tell NSA of latest decrypt until May 28.

May 18: Timetable of May 15 confirmed for FO & MI6.

May 24: FO & MI5 decide Maclean cannot be interviewed until June 18.

May 25: Morrison signs off on interrogation for the following month.

While a cynical interpretation might suggest that the decision to interrogate Maclean was taken only when the escape plan was properly hatched and about to be executed, a more conventional analysis would declare MI5 and the FO were torn between a preference for waiting until Maclean was arrested before informing the FBI and a desire to move quickly to satisfy critics like Mackenzie. They dreaded the story getting out through other channels, and they accepted that it was essentially a breach of trust not to keep their counterparts at the FBI informed. Behind all this were the circumstances of Melinda Maclean’s pregnancy, and a natural, humane consideration to wait until after her confinement. In addition, MI5 reputedly needed time – three weeks – to prepare for the interrogation, as has been suggested by Nigel West. It would be senseless to suppose that a decision could be passed down on the Friday for a proper session to be started the following Monday. As a sidenote, Dick White’s reminiscences, given to his biographer, again need to be treated sparingly: he claimed that Sillitoe ruled that no action could be taken until Hoover were informed.

Thus the remonstrations that the interrogation was scheduled for May 28, echoed so frequently in the literature, represent a shocking display of deception. The prime culprits for this grotesque disinformation were Carey-Foster and Patrick Reilly, with the latter being particularly egregious (see Glees). Carey-Foster fed Andrew Boyle a similar, but less expansive, message. MI5 and the Foreign Office were in horror of the public relations disaster that would occur (primarily for the FO, as MI5’s mission and organization were not well-understood by the public) should the facts come out that the surveillance of the pair had been lacklustre and ineffective, thereby pointing to operational incompetence They thus had to create the phantom of an alerter, ‘the tipoff man’, who had managed to warn the miscreants of the imminent arrest. It was nonsense, and they knew it, but they thought that they could get away with it. And, for a long time, since the politicians themselves were either misinformed or confused, they did so. The ‘Third Man’ myth took off.

- 11. Maclean’s Leave: Who granted leave to Maclean for May 26? Why was the fact not broadly known? Why did Makins and Carey-Foster even think that he might have been granted leave on May 28 as well?

The fact that Maclean was able to take leave on Saturday May 26 (even though he was not around to enjoy it) is a matter of great concern. If he was under close surveillance, and in danger of absconding, one might expect that the antennae of the authorities would have been optimally sensitized to detect any unusual behaviour or movements. The circumstances of his request are indeed very puzzling. The primary source is Roger Makins’ unpublished memoir held at the Bodleian Library (which I have not inspected, but which Philipps uses freely): one would not expect Makins to record anything self-incriminating in such an account, but Makins comes across generally as a rather naïve soul. Maclean apparently bumped into Makins on his way out of the Foreign Office, and he reminded him that he ‘would not be in in the morning as he had his sister staying with him’. Makins thought little of it immediately, but, after reflection, went into the office the next day to see if Carey-Foster was still there. Yet the office was empty. Since Makins was running late for his social engagements, he did nothing, assuming that, since Maclean was being monitored, there was no point in raising the alarm.

This is an extraordinary testimony. Makins openly writes about being ‘reminded’. Why did he not challenge that claim? Had he forgotten? If Saturday was a workday, why would Makins not have attended the office that day, anyway? And why would Carey-Foster ‘still’ be there, as opposed to being required to be present? Why did Makins have social engagements on a Saturday morning? Could Makins not have telephoned Carey-Foster or White? Moreover, Philipps offers two accounts of Maclean’s requesting colleagues to stand in for him on the Saturday – a call to Geoffrey Jackson from the Travellers Club at lunchtime, and an in-person request to his subordinate, Margaret Anstee, during the afternoon. If these two had compared notes, might it have struck them as odd? Should Makins perhaps have checked in Maclean’s office to see who was holding the fort, and then perhaps attempted to verify their stories?

Maclean’s excuses for absence, to Makins and Jackson, were lies, as could have been verified on that same day. Yet the situation became even more absurd. When Maclean did not turn up at the office on Monday, either, Carey-Foster was informed that the telechecks, and a call by Lady Maclean, indicated that Maclean had been away for the weekend. Carey-Foster then confirmed to MI5 that Maclean had not come in, but that he was not alarmed since Maclean had asked for a day off. Carey-Foster then confirmed this understanding with Makins, who was also under the belief that he must have given him the Monday off as well! Thus did the brilliant mind of the future Lord Sherfield work: on Friday, somewhat perturbed by the suspect’s taking an impromptu Saturday off, and on Monday leading himself to believe that he had given him leave of absence on the Saturday and the Monday.

The incompetence shown by Makins and Carey-Foster was rightly castigated in the Press.

- 12. Foreign Office Response: Why was the response to Maclean’s absence on May 28 so sluggish? Why did no official immediately call the Maclean household to determine his whereabouts?

We should recall that these shenanigans were supposedly taking place on the day when Maclean was going to be brought in for interrogation, as Makins, Carey-Foster and Reilly earnestly informed the journalists later. Whereas, if that had been true, a feverish response would have been expected, we should certainly disregard that notion, and simply ascribe lowly and dishonourable motives to the distinguished Foreign Office civil servants. Yet one might have expected a more urgent response, given the general surveillance, and the warnings suggested by the provocative events of Friday evening. By all accounts, however, Carey-Foster did not jump into action until Melinda Maclean called some time after 10 o’clock in the morning (Melinda knowing, of course, the somewhat leisurely hours maintained by the Foreign Office).

Unfortunately, the archival record is probably wrong here, which has led some analysts (Philipps included) to suggest that Melinda did not call in until the Tuesday. The Concordance of Events at KV 2/4140, which includes Mrs Grist’s record of telechecks, declares that Mrs Maclean called the Foreign Office at 10:58 am on May 29 [sic], and it lists other happenings, such as David Footman’s call to Liddell, as also occurring on that day. While the delayed reaction by Footman is probably true, the logging of the other events must be a mistake. Melinda would not have waited another day for reporting her husband’s absence, and Carey-Foster would surely have reached out to the Maclean residence before then. Indeed, Carey-Foster confirmed to Dick White that he had received Melinda’s call on the morning of May 28, although he dissembled somewhat, stating that the call arrived at 10:15 am, presumably before he had settled in his chair properly, thus giving the Director of B Division the impression that he not been twiddling his thumbs. (The official Grist report stated that she called at 10:58 am.) One might, however, expect that the Watchers would already have alerted White to the fact that Maclean had not arrived on his usual train at Victoria Station that morning, rather than waiting to enter a daily formal report. White, however, apparently did nothing. And then the urgent meetings began.

Yet the whole performance is one of incredible insouciance. If the objectives of the surveillance had clearly been to keep a very close eye on Maclean’s movements, and to prevent him skipping the country, such abnormal and suspicious events as his taking the Saturday off, and not turning up for work on Monday, should have rung alarm-bells immediately.

- 13. Telephone Intercepts: What did the telephone intercepts over the weekend tell the authorities about Maclean’s movements? Why were they ignored?

Again, the formal record is intriguing. The Concordance is sparse: it records only two events – on Saturday, “Telechecks on Tatsfield and Lady MACLEAN’s flat gave the impression that Donald MACLEAN was at home”, and on Sunday, “No calls were made or received at Tatsfield and the telephone of Lady MACLEAN still gave the impression that Donald MACLEAN was at home.” Presumably Melinda and her mother-in-law made oblique references to Donald’s proximity. Yet, apart from implying that Donald’s mother may have been involved in the conspiracy, without explaining what was said to relay that impression, this is a highly sanitized and incorrect account. Roland Philipps has been enterprising enough to study KV 2/4143 (one of the Maclean files, which I have not yet seen), and reports that a call was received at 8:00 pm on Sunday 27, when Nancy Oetking, Donald’s sister, ‘rang to say they were at Ashford on their journey from Dover and would arrive at about 9:30.’ Philipps goes on to write that Melinda told her visitors that Donald had since rung ‘to say he would be back late and they were not to delay dinner for him’.

We are thus faced with the paradoxical situation in which Melinda, conscious of her non-telephone conversations being overheard, invents a call from her husband which her surveillers would know did not occur. Yet the Watchers did nothing, and she was never challenged on it. At 10:09, Lady Maclean called to discuss arrangements for the next day, and, tellingly, asked Nancy to check with Donald while she was on the line. After talking to her husband, Nancy told Lady Maclean that she had conferred with Melinda rather than Donald. Philips does not, however, quote the report from May 28, which states that ‘it was learned from the telechecks on Tatsfield and Lady MACLEAN that Donald MACLEAN had in fact been away at the weekend and was not yet back’ – an item noted by Nigel West.

Philipps ignores the anomalies explicit in these anecdotes. He does not remark on the discrepancy between the detailed records and the Concordance – with which he has already shown familiarity. He does not point out that, if Donald had indeed called home to speak to Melinda, that call would have been picked up by the telechecks. The Concordance comes to this conclusion without reporting how it gained that insight: the Oetking call must have been registered, but then quietly dropped. Also, if Melinda had claimed that she had spoken to him, one might wonder why she did not ask him about his whereabouts, and when she might see him again. It was an extraordinary oversight by MI5 and the Foreign Office not to pick up on this subterfuge, but, since the official record shows that they wanted to bury the complete Oetking business, it is perhaps no surprise. I look forward to exploring the whole of KV 2/4143 before too long.

- 14. Role of Jackie Hewit: Why did he act so hysterically? Why are there conflicting stories of whom he called? Which can be trusted?

Hewit should potentially be a vital part of the transactional record. He was Burgess’s residential partner and factotum; he had been the lover of Blunt as well as Burgess; he was in the middle of the business with Bernard Miller, the American who had been the placeholder for the berth on the Falaise; he sounded the alarm when Burgess did not return; he knew most of Burgess’s friends and contacts. He called the Rees household at the peak of the events, and called Goronwy ‘Gonny’, indicating that they were on very friendly terms. Indeed, he leveraged this unique position to sell his story to the Daily Express, its coverage of the Missing Diplomats relying mostly on what he told the newspaper in the early days. Unfortunately he was an established liar, thief, and blackmailer, and we should be very cautious about accepting his testimony. This hesitancy should especially be applied to his ‘unpublished memoirs’, which Lownie relies on quite extensively. What Lownie quotes includes some anecdotes that show a degree of verisimilitude, but they also show some violent contradictions that help to undermine anything factual that he may have reported.

In fact, Hewit had a special relationship with Blunt. He had been employed by him in WWII as an agent for Blunt’s TRIPLEX operation in MI5, and for performing general spying on people. His cryptonym was DUMBO, and he was spectacularly inefficient. Thus Blunt knew he had a potentially dangerous element on his hands, and that is how it turned out. Hewit showed his volatility when describing how Burgess presented his plans for the weekend. He was interviewed by Jim Skardon on June 5, Skardon blatantly describing him as a ‘loathsome creature’. Hewit went over his long career with Burgess, including his role in the overheard telephone conversations of the Sudeten politician Henlein in 1938. Yet the most important of his assertions was his describing the events of May 25. Guy Liddell later reported that Blunt told him that Hewit had called Blunt on May 26 to tell him that Burgess had not returned that day, as expected. Hewit also called Miller that day with the news. He also called the Reeses. Yet in his memoir, Hewit wrote that Burgess had told him that he would not be back until the Monday. The subsequent hue and cry were thus all a melodramatic stunt. He also claimed that he guessed that the colleague in the Foreign Office, who, Burgess told him, needed help, and would be accompanying him in place of Miller, was Maclean.

There is no doubt that Hewit’s frantic telephone calls over the weekend rather disturbed the illusion that Burgess’s disappearance was not detected until Tuesday, when an apparently shocked David Footman broke the news to Guy Liddell (having committed to Rees that he would call him immediately on the Sunday). Thereafter Liddell learned from Blunt what Hewit had told him. All in all, it reflected badly on Blunt, because of his closeness to the affairs, and his lack of openness. Hewit would later use this to his advantage when he successfully blackmailed Blunt into paying off an amount of money that he had stolen from his employer. All this sits in the Hewit files at KV 4526-4529.

- 15. Role of Goronwy Rees: How can his reactions to the news of Burgess’s call be interpreted? How did he really follow up? When was he telling the truth?

Where were Rees’s loyalties? It is difficult to gauge the true allegiances of this slippery character. As I have indicated above, the two given agendas for Burgess’s long-planned self-invitation to Sonning do not make sense. Moreover, Rees lied about his contacts with Burgess after the visit. His written report on the events, after his second interview, that can be found in KV 2/4104, is stilted and artificial – too precise on some matters, too vague on others, and suggests that the whole episode was designed to give Rees cover. For a recent analysis of Rees’s activities at the time, please turn to https://coldspur.com/an-anxious-summer-for-rees-blunt/.

Yet a closer inspection of the files shows that major discrepancies appeared in the timing of the events immediately after the disappearances. I believe that they were due to a) Rees’s deviousness in trying to exonerate himself; b) Liddell’s need to conceal the fact that he met with Rees on June 1; c) MI5’s inattention to detail when its officers (particularly Peter Wright) returned to the investigation; d) Rees’s failing memory; and e) Rees’s desire to rectify the chronicle when he came to write his book.

When Reed set out to capture the sequence of events in March 1956 (see KV 2/4605), he recorded Rees calling Footman, and then Blunt, on the morning of Monday May 28, with Footman not reacting until 11:00 am on the following day, when he called Liddell. On May 30, Blunt and Harris came to see Liddell, who confirmed to them, in confidence, that Burgess had accompanied Maclean. The record then has Liddell reporting, on Friday June, that he had received a message from Rees describing his wife’s bizarre conversation with Burgess, and that he had asked Rees to re-construct the conversation in writing, which Rees subsequently did, passing it, for some reason, via Footman on June 2. Footman then handed it to White on June 6, just before Rees’s meeting – alongside Blunt – with White.

Liddell’s diary, however, tells otherwise. He declared very plainly that he had had a meeting with Rees on June 1, at which he no doubt persuaded Rees to hold back his accusations, because of the specially sensitive relationship with Blunt (see https://coldspur.com/an-anxious-summer-for-rees-blunt/), either because Liddell convinced Rees that Blunt was working undercover for him, or alternatively because he suspected Blunt, and already had him under close surveillance. (Rees would later inform Andrew Boyle about the lunch meeting with Liddell, and it is described both in Climate of Treason and The Perfect English Spy.) Liddell reinforced this fact by placing a note on file on June 1 (sn. 94b, KV 2/4102) that [name redacted] ‘told me about a conversation that his wife had had with BURGESS before the latter’s departure’, implying (but not guaranteeing) a face-to-face meeting. Whether out of ignorance or complicity, Reed introduced Rees’s report of the conversation by posting a careful note to Rees’s file on June 6 (sn. 7b in KV 2/4603), stating that ‘Geronwy [sic] REES telephoned [sic!] Captain Liddell last week’ to inform him of the ‘alarming’ conversation. Thus a new mythology was created in which Rees did not meet any MI5 officers until June 6.

Much later, when Reed interrogated Rees in the wake of the People articles in March 1956, he challenged Rees’s account of the timetable. In his report (sn. 177a in KV 2/4605) he wrote:

REES claimed to have come to the Security Services within 48 hours of his return to his home at Sonning and that he had seen BLUNT in the intervening period, In fact REES had not given to us the information about BURGESS’s Comintern work until 10 days after his disappearance.

This would suggest that Liddell had not told Reed about the face-to-face encounter on June 1. Reed went on to challenge Rees about his account of the facts. Rees stuck to his story that he had spoken to both Footman and Blunt on May 28, and had thus expected a call from MI5. Reed suggested to him that it was the lack of response that prompted him to telephone Liddell on June 1. (One might ask why, if Rees was able to telephone Liddell directly on Friday June 1, he had not been able to do so on May 28, instead of using Footman as a go-between.) Rees responded that he presumed it was so, but that he could not remember making the call. Of course: he had visited instead, but he needed to conceal the fact of that personal visit from his inquisitors. Whatever occurred, Reed’s accusation that Rees had delayed ten days before alerting the Security authorities of Burgess’s Comintern connection was unfair, but justified in Reed’s eyes, and not something that Rees could have easily refuted.

Peter Wright took up the cause, too, in May 1965, when he and another officer interviewed Mr and Mrs Rees (sn. 377a, KV 2/4608). Again, confusion appeared to exist between i) the fact of Rees’s attempt to contact MI5 and alert it to the possibility of Burgess’s escape to Moscow, and ii) his knowledge that Burgess had worked for the Comintern, and slowness in passing on that insight. At the beginning of the interview, both Goronwy and Margie insisted that Goronwy had ‘not knowingly concealed his knowledge of BURGESS’s pre-War espionage’, and that he had come forward after ‘a lapse of only 48 hours’. What delimited this two-day period is not at first clear, but Margie Rees, later in the interview, changed her mind about the timetable. Wright noted that, if only forty-eight hours had elapsed between the time that Rees contacted Footman (either May 27 pm or May 28 am) and Rees’s subsequent visit to MI5 with Blunt, Rees would have had no cause to complain. Yet the latter took place on June 6: Margie then accepted the fact that ‘there had been an interval of ten days between Guy’s defection and the MI5 interview’. She – like Reed and Wright, and several others – obviously had not been told about her husband’s luncheon meeting with Liddell on June 1. Goronwy had to bite his lip, and move on.

So when it came to writing Chapter of Accidents, Goronwy set out to correct the account, clearly describing a meeting with an (unnamed) MI5 officer as occurring soon after the escape, but in the process mangling the chronology so badly (adding the premature flourish about the newspaper placard) that he should have lost credibility immediately. Yet no one knew enough to untangle the lies.

My supplementary conclusions are as follows:

- In May 1951, Rees was much closer to Burgess, Blunt and Footman than he made out. He concealed the fact that he had recently worked with Burgess and Blunt on the Borodin case, and MI5 reported that Burgess, Rees and Footman had been energetically criticizing Borodin after his appearance at the 1949 Conference in Oxford. Rees was still working (part-time) under Footman at MI6 when the diplomats disappeared.

- Rees had been briefed by Burgess about the coming escape plan. His surprise, and then breakthrough conclusion about Burgess’s escape to Moscow, after he listened to his wife on May 27, were feigned. It was a ruse to allow him to claim integrity and loyalty to his bosses when the knowledge was already too late to have any effect, or it had already been carefully exploited.

- Rees’s using Footman as a back-channel to Liddell was clumsy and devious. He no doubt wanted to implicate Footman in his wiles, knowing that he was as guilty as Rees himself, and he thereby also inserted a built-in delay into the process. Since he arranged a meeting with Liddell on the Friday, and Liddell acknowledged that Rees had been able to telephone him, Rees could have called Liddell directly on the Monday morning. (He also sent to Footman, on June 2, his summary for Liddell of the conversation they had, asking Footman to send it on, which seems an unnecessarily bureaucratic procedure.)

- Despite what has been written about Rees’s conveniently being away from the scene, at Oxford, when the abscondment occurred, I judge that it must be a coincidence. His attendance at All Souls seems to have been required before the timing of the Falaise booking was determined.

- I suspect that Rees was being used by MI5/MI6 in some way as a back-channel to Burgess, in a way that suggests that senior officials at MI5 and the Foreign Office would not have been unhappy if the escape plan succeeded.

- Rees clearly expected a different outcome, and that his accusations against Blunt would be followed up. He showed some political naivety in misjudging the relationship between Liddell and Blunt and the general nervousness about letting MI5 skeletons out of the cupboard, as well as the reactions of Liddell and White to his own chequered past.