Contents:

Introduction

Analysis of Works Since 1987

Phase 1: Academics and Overseas

Phase 2: The Soviet Influence

Phase 3: Authorized History

Phase 4: The Release of the Archives

Phase 5: Post-Archival Exploitation

Phase 6: Further Archival Releases

Conclusions: Paradoxes, Contradictions and Conundrums

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Introduction

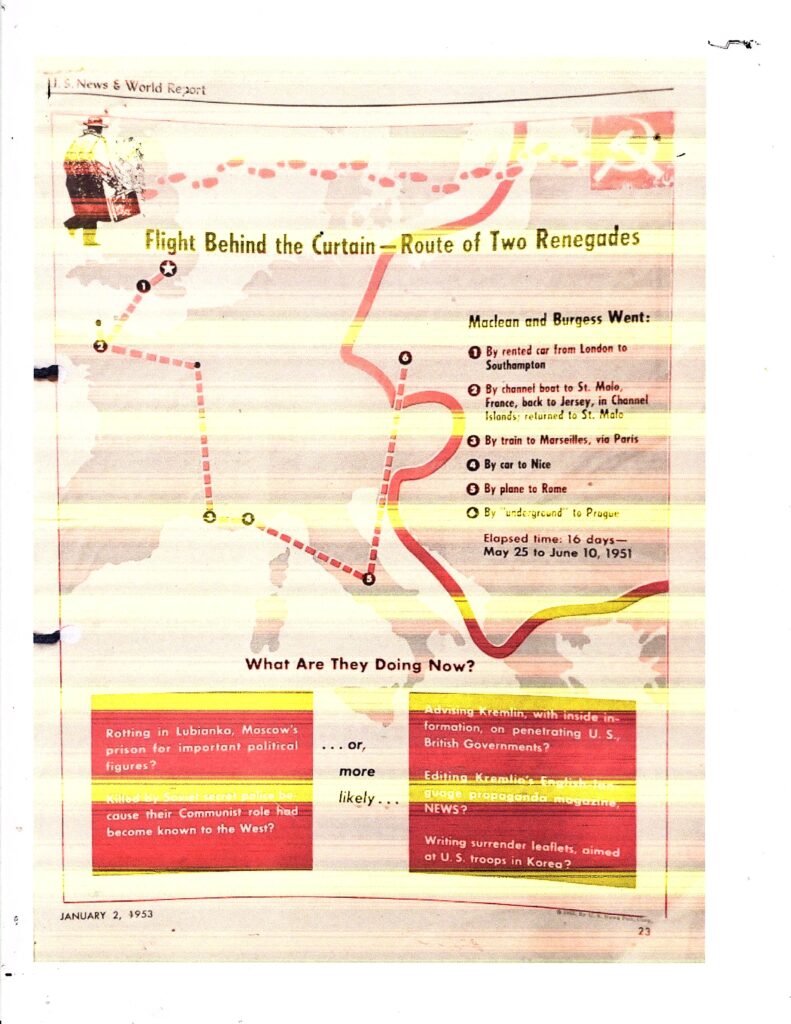

In last month’s report, I summarized the accounts of the events surrounding the ‘Missing Diplomats’ in the summer of 1951, focussing on the period up to the release of the TV movie The Fourth Man in 1987. The accounts during this period were largely anecdotal, and based on rumour or possibly unreliable sources who had some ulterior motive. There was one major official pronouncement (from the Home Office in 1955), and it was received with a great deal of scepticism. The appearance of the defectors Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov in Australia in 1954, and their contribution to the debate, had reminded some writers that British sources alone could not tell the whole story. Leaks arrived from disgruntled insiders, who were dismayed that the Government was not telling the whole story, but such insights were inevitably intermingled with the distracting tales from those in authority who probably had some objective in covering up the true facts. It was in their interest that confusion remained as the state of the game.

The participants themselves also had something to gain by distorting the truth, either because they had something to hide (Melinda Maclean), or wanted to aggrandize their own contribution (Kim Philby), or to minimize their culpability (Guy Burgess). Goronwy Rees was far more influential than he deserved to be. After his disastrous attempt to open the veil of secrecy in The People in 1956, his memoir published sixteen years later was implicitly trusted (and quoted) much more than it merited. Rees provided much of the material to Andrew Boyle that the latter exploited in The Climate of Treason, but also set some false hares racing in its pages, since he also wanted to minimize the role he had played in collaboration with the Cambridge Spies. Now it is time to leave the fancies of Robin Chapman behind, and analyze the literature published since 1987. My goal? To present a fresh account of what really happened in the Case of the Missing Diplomats.

As a prelude to my detailed study of the period, I organize it into six rough, but not watertight, segments: 1) Academics and Overseas (1987 to 1994); 2) The Soviet Influence (1994 to 1999); 3) Authorized History (1999 to 2015); 4) The Release of the Archives (2015); 5) Post-archival Exploitation (2015-2018); and 6) Further Archival Releases (2022-2025). I do not believe anything significant has been published since the flurry in 2018.

- Academics and Overseas: A more disciplined approach to the material was attempted by Glees (1987) and Cecil (1988), the latter expanding on his brief flurry from 1984, although both projects were flawed by a less than rigorous exploitation of the material at hand, and a susceptibility to being misled by insiders. This period also enjoyed a renewed journalistic offering by Costello (1988), who provided a rather chaotic analysis while bringing some useful insights from an American perspective. A deeper, more sceptical, and serious evaluation was then provided by Newton (1991), who used American source material very carefully.

- The Soviet Influence: Startling new testimony came from Modin (1994) and Borovik (1994). While the KGB account contained some probably reliable facts, the opportunity for propaganda was strong, and a degree of wariness in treating their work is essential. Borovik was not an insider, but someone who had to interpret what he was told by Philby and Modin. West and Tsarev collaborated on a work that exploited KGB archives (1998), although the independence of their work must now be questioned. Cave-Brown also made a brief and melodramatic insertion in 1994, while two examples of memoir/biography appeared in this period. Jenny Rees (1994) expanded on her father’s dubious memoir with some personal observations, while Dick White offered his unreliable and occasionally scandalous comments to his biographer, Bower (1995).

- Authorized History: Andrew and Mitrokhin, taking advantage of Mitrokhin’s painstaking copying of Soviet archives, were able to publish a breakthrough work in 1999, the assertions of which are probably more reliable than Modin’s. This decade was otherwise quite barren: Carter provided a rich biography of Blunt (2001), which was skillfully compiled, but obviously suffered from having no access to any official archive. After Aldrich provided a brief but informative section in a broader work (2002), the next major study to appear was Andrew’s authorized history of MI5 (2009). This was a colossal disappointment, as Andrew largely just reproduced chunks from his Mitrokhin Archive volume, and he had obviously been steered clear of the critical material, most of which was not housed in MI5 files, but in Foreign and Colonial Office folders. The arrival of Andrew’s work suggested perhaps that the ‘final word’ on the saga had been written, which was a major misapprehension.

- The Release of the Archives: Maybe the delay in declassifying so much critical material was deliberate: the authorities may have judged that the public was stunned by now, that individual memory was severely weakened, and that the official account could stand unchallenged. And the method of release was very fragmented, complicating the task for any researcher to apply a disciplined investigation. Yet there were gems to be found in the release of (partial) MI5 files on Burgess and Maclean, on the MI5 view of the Molehunt, as well as on Foreign Office investigations into the leakage of telegrams, the ‘PEACH” (i.e. Philby) inquiry, and assorted related material. A few biographies had preceded these releases, no doubt to the chagrin of the authors. Holzman offered two self-published biographies of Burgess (2012) and the Macleans (2014), both of which dredged up some useful new facts, but skated away from any novel or bold conclusions. Macintyre delivered an engaging but unreliable profile of Philby (2014), while Lownie performed much the same task with his biography of Burgess (2015).

- Post-Archival Exploitation: the first work to exploit the recent archival declassification was by Purvis and Hubert (2016), although they had to make hasty revisions to their book just before publication, and had clearly not enjoyed any intensive study of the material. Some of their insights were nevertheless impressive. West’s analysis of the events, focusing on the role of Guy Liddell (2018), was a very erratic work, containing large chunks of extracted material, but ignoring much of the historical evidence, and drawing back when anything controversial cropped up. The same year, Philipps’s biography of Maclean appeared, but he very selectively exploited the fresh archives, and again showed an absence of interest or wonderment at many of the blatant paradoxes that his research threw up. The third major publication in 2018 was Davenport-Hines’s study of the ‘Enemies Within’. It was a hugely entertaining volume, but inconsistent in its use of sources, and boundless in the confidence of its conclusions. It likewise offered no hard, comprehensive analysis of the confusion of ‘facts’ that were still laid out for those prepared to look closely.

- Further Archival Releases: In 2022 more Personal Files were released by the National Archives, with those on Victor and Teresa Rothschild, Tomás Harris, Goronwy and Margery Rees, and Jackie Hewit being significant items. While only one potentially significant book has been published since then (Calder Walton’s Spies), a vast new set of material was declassified in January 2025, including MI5’s Personal Files on Philby, Blunt and Cairncross.

Yet the state of the 2015 issuance remains very problematical: as I have described before (see ‘Guy Burgess at Kew’, in https://coldspur.com/summer-2024-round-up/), the records on Burgess are unnecessarily fragmented across scores of files. Nearly all of them are undigitized, and thus not downloadable. For a researcher based in London, that may not be so much of a problem, as they can be scoured for interesting tidbits (and that is the approach that recent writers appear to have taken). It presents a severe problem for me, however. I cannot gauge the relevance or size of most of the files merely by reading their descriptions, and thus giving instructions to my local researcher to photograph what is important can be an expensive and perhaps wasteful process. I shall accomplish what I can.

I predictably believe that the contents of those files are crying out for a serious integrated analysis to include what has gone before, but the energy and dedication required to perform that task may be beyond the bounds of today’s commercially-oriented authors. The various doyens of the industry appear to have lost some of their enthusiasm, or perhaps are reluctant to re-tread ground they have stepped over before. Yet I suspect that the public’s interest in stories about the Cambridge Five, and its latent desire to know what lies behind the durable rumours, and the permanent contradictions, are still strong.

I next offer detailed analysis of all the works listed above.

Phase 1: Academics and Overseas

The Secrets of the Service by Anthony Glees (1987)

Professor Glees is an academic who has specialized in security and intelligence matters. (For the record, I should declare that it was my reading of The Secrets of the Service that prompted me to contact the Professor, which eventually resulted in his acting as supervisor on my doctoral thesis.) He had been fascinated by the apparent secrecy behind the story of the Missing Diplomats: in his words “Those who knew did not want to say; those who did not know were not going to be told”. He was also perturbed by Chapman Pincher’s campaign against Roger Hollis, in which the journalist presented the one-time head of MI5 as a Soviet mole. Glees knew Hollis, and knew his family, and judged that Hollis was very unlikely to have been recruited for such a role, and to have been able to sustain it. He also picked up the accusation that Robert Cecil had openly made against Roger Makins (the future Baron Sherfield), where Cecil appeared to blame Makins for not acting on the fact that Maclean had asked for leave on the half-day of Saturday May 26, namely by not pursuing it aggressively enough with Carey-Foster, the Foreign Office Security Officer. Glees noted that some MI5 and MI6 officers to whom he spoke still argued that Maclean could have been arrested, but for Makins’ indolence. On what grounds he could have been arrested and detained – as opposed to being required to attend an interrogative interview –was not stated.

The main conundrum Glees identified was stated thus: “Why had the two men defected immediately after the decision was made to arrest and interrogate them?”. Glees heroically tried to decode all the messages he was getting, but overall turned out to be a bit too deferential to, and trusting of, what the ‘Great and the Good’ pronounced, or privately told him, from Harold Macmillan (who claimed that Burgess had not been under any suspicion) to the highly deceitful Patrick Reilly, who had been close to the action, and had wanted to conceal what really happened. Glees also appeared to trust the public statements that Anthony Blunt made about his own involvement. In this way, he stumbled somewhat around the key events. He swallowed whole the notion that there was a Third Man who gave a late tip-off to the miscreants, and that there had indeed been a plan to interrogate Maclean on the morning of May 28. He trusted what Boyle wrote (Boyle having in turn been fed by the awkward and mendacious Carey-Foster) that Philby had been the probable leaker, although he did not seriously inspect the chronology, or attempt to identify the mechanism whereby Philby had both learned of the plan and been able to send a speedy alert to Burgess. He echoed Makins’ assertion that Burgess had ‘decided’ to defect only at the last minute.

Makins did, however, bequeath a very important insight to Glees. He told the author in 1985 that he had been asked (presumably by Dick White) to employ Maclean again in Whitehall ‘in order to keep an eye on what he did’. Makins (then Lord Sherfield) admitted that he had known for several months of the suspicions against Maclean, and that putting him in charge of the American desk was the least sensitive post he could find without raising Maclean’s suspicions. Furthermore, MI5 had told him that Maclean was being trailed only in London, as if that somehow lessened the furtiveness of Makins’ contribution. This was not a very auspicious performance by Makins (who had also came under criticism for his laxity in the matter of Maclean’s Saturday leave), and he was criticized for it.

Glees showed far too much deference to Patrick Reilly, who corresponded with him, Reilly perhaps thinking that the exchange would be forgotten or overlooked. Reilly insisted that the FBI had been kept informed (wrong), that there was no doubt that it was Philby who set Maclean’s escape in train (correct only in a very narrow sense), that Philby was able to engineer Burgess’s recall to organize the escape without any involvement from the Soviet control (wrong), that Philby used contacts in Washington to get a message to Burgess by the morning of May 25 (wrong), and that Maclean was about to be interrogated on May 28 (wrong). What Glees failed to do was to challenge Reilly on any of his points, even to remind his correspondent that the official Home Office pronouncement of 1955 declared that there was no immediate plan to interrogate Maclean. How would Reilly have responded to that? Overall, I judge Glees’s contribution as an opportunity missed, with not enough rigorous preparation carried out before he set himself up to make his inquiries.

A Divided Life by Robert Cecil (1988)

Robert Cecil followed up his 1984 segment [see last month’s posting] with a fuller study of Maclean in 1988. Cecil was in a curious position: he was a career diplomat who had been a close friend and colleague of Maclean’s, both at Cambridge and in the Foreign Office, and was due to replace him at the American desk in London. That association probably stalled his career, and in 1986 he moved to an academic position at the University of Reading. He had also worked for Stewart Menzies, the chief of MI6 during the war (a post also enjoyed by Patrick Reilly), and so regarded himself as somewhat of an intelligence insider. He thus brought some unique insights to the inspection of the saga of Burgess and Maclean, but displayed some muddled thinking over the evidence, which resulted in a very equivocal conclusion.

Cecil took great offence at Anthony Glees’s representation of his charges against Makins, characterizing Glees as an ‘ill-informed academic writer’ who had presented Cecil as stating that Makins was essentially responsible for the defections. This was a hypersensitive attack by Cecil, and was possibly prompted by a degree of academic jealousy (after all, Cecil was himself an ‘academic writer’ by then): in fact, casting blame towards Makins was exactly what he had done. Perhaps to compensate for his past institutional disloyalty, he took pains to declare that any allegations that had been voiced that the Foreign Office had been glad to see the back of Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean were baseless.

His analysis is a mixture of close insights, and woolly thinking. He had some personal experience of the immediate aftermath: he was in Paris on the evening of May 29 (Tuesday), and witnessed the Sûreté carrying out traffic stops in an attempt to find the escapees. On the other hand, he made some odd judgments. He claimed that there was evidence ‘pinpointing’ Maclean as HOMER in late 1950 or early 1951, which was an unfortunate choice of metaphor for that stage of the investigation. He was misguided about Maclean’s status with his controller in London. He wrote that it was implausible that Burgess was essential to the task of abetting the escape, since the NKVD was active in London, and that Maclean decided to break off contact with his control only when he realized that he was being surveilled – pure guesswork on Cecil’s part. He also claimed that Burgess was not being watched, and that there had been no dossier maintained on him at the time. It sounds as if he were merely parroting the party line.

His representation of the final days is also messy and lazy. He did correctly state that there was no decisive meeting on May 25, the day of the escape, but that a decision had been made the previous day to interrogate Maclean some time after May 28. The coincidence, however, did not allow him to dispel the notion that a leakage had occurred, either in Washington or in London, and he imputed some significance to Philby’s ability to send an emergency airmail to Burgess, without any indication of spelling out what he learned when, how quickly the letter arrived, and how Burgess responded to it. He did, however, appear to eliminate Hollis from the list of suspects, informing his readers that the future chief of MI5 never attended any of the meetings held by Sir William Strang, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office. He trusted Blunt when the latter asserted that the tickets for the Falaise had been bought some days before, thus undermining the theory of the last-minute alert.

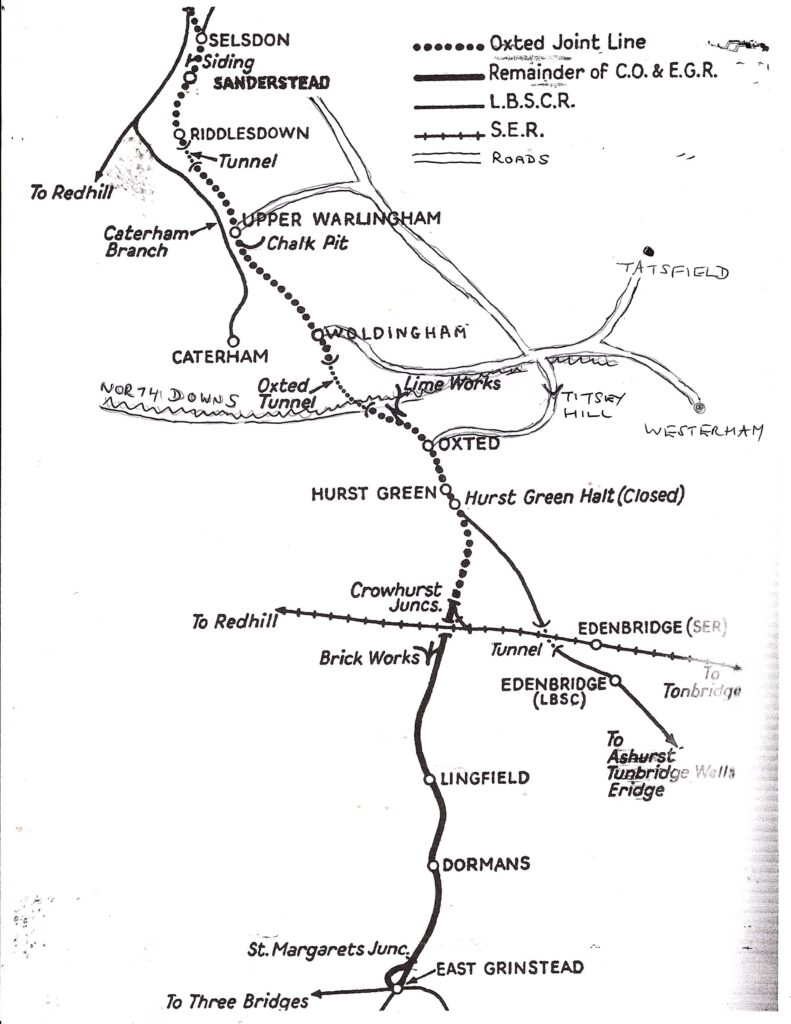

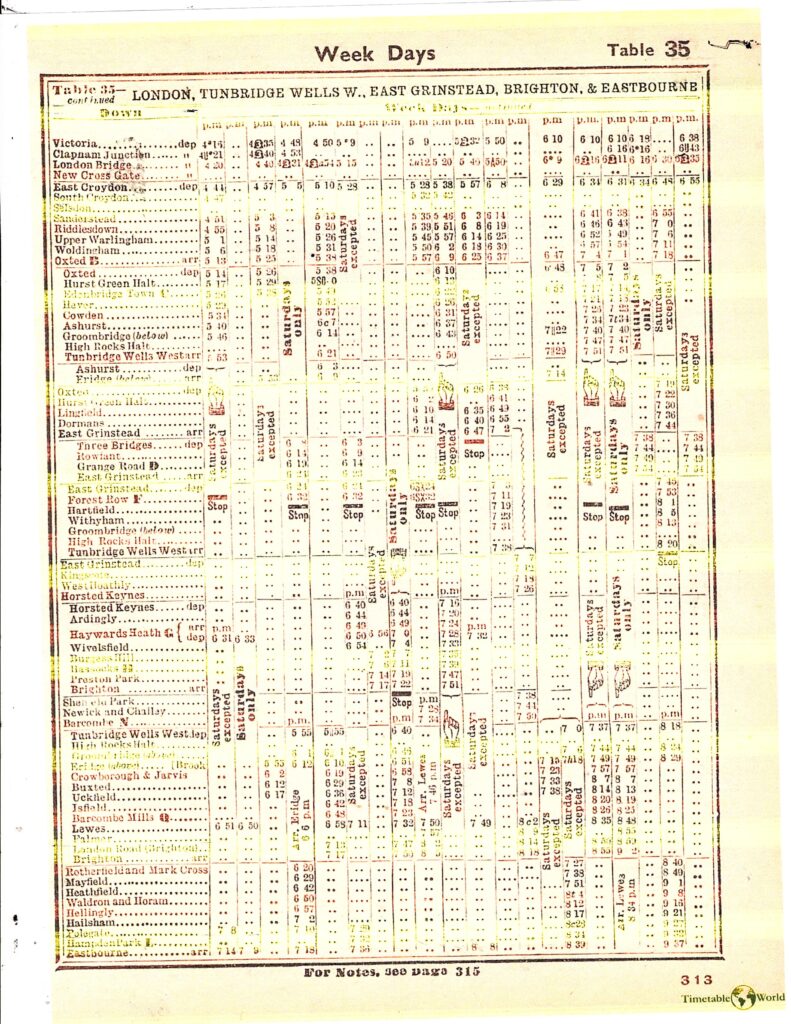

Cecil gets himself in a tangle over Maclean’s last movements. He wrote that Maclean sometimes varied his commuter routine by travelling to Victoria rather than Charing Cross. On the contrary, Maclean normally travelled from Oxted to Victoria (and back) because it was a fast train, even though the walk from Victoria to the Foreign Office was longer than that from Charing Cross. The 6:10 pm down train split at East Croydon, with the rear four carriages becoming a slow train, halting at stations such as Upper Warlingham and Woldingham, which was closer to the Maclean house in Tatsfield. The drive home from either station avoided the long and steep Titsey Hill, which defined the climb back to the North Downs from Oxted. (For further background on this part of North-East Surrey, please see https://coldspur.com/reviews/some-reflections-on-the-north-downs/.) Thus Maclean could preserve some options by taking the 6:10 train. On the other hand, the Charing Cross train would require a connection at East Croydon. Moreover, Maclean normally left his car at Oxted Station, so he would have to pick it up in the evenings. This misunderstanding, however, leads Cecil to claim that Maclean missed his regular 5:19 pm train from Charing Cross on Friday, May 25, and switched to Victoria.

Matters became out of hand the next morning (Saturday, with half-day working). Cecil writes that when Maclean’s ‘usual train’ arrived (the terminus undefined) without the emergence of Maclean, ‘phones began to ring’. It was then that the Foreign Office and MI5 learned that Maclean had gained leave for that morning (with Makins being regarded as lax), but no one seemed to have raised any red flags. On the Monday, however, events took on a preposterous character. Cecil observes that Melinda Maclean made two calls to the Foreign Office on Monday May 29 [sic!], notifying them of her concern over her husband’s absence. Cecil thus appears to make a slight correction to what he wrote in The Cambridge Comintern, where he gave the date as May 28. This conflict will resurge later in this analysis. The error probably reflects a mis-statement in one of the archival notes, to which Cecil presumably had early and privileged access. Others made the same mistake.

Cecil must be referring to the Monday, however, since he next confirms that Carey-Foster received the call from Melinda, and then verified from the watchers that Maclean had not appeared on the Monday morning train either. That was an astonishing piece of behaviour from Carey-Foster, especially since the Saturday incident should have placed the security officer on guard. Why was the Foreign Office, and Carey-Foster in particular, not informed of Maclean’s absence first thing on Monday morning? After all, Andrew Boyle had strongly implied that Carey-Foster and Makins had told him that Maclean was due to be interrogated that day! Cecil was surely negligent in not following up Carey-Foster’s studied inattention. Lastly, Cecil reports that Robert McKenzie, Carey-Foster’s deputy, who had recently passed through London on his way from Washington to Paris, was invoked in the French capital, and he passed on the information that the Sûreté was already involved in the hunt on the Monday evening. Overall, it is a very ingenuous piece of work by Cecil.

Mask of Treachery by John Costello (1988)

Another, more journalistic, work appeared in 1988. Costello was an ‘encyclopaedist’ in the Cave-Brown tradition, who seemed to hope that, if he recorded in one place all the ‘facts’ that he could assemble, his readers would be able to work out what really happened. Mask of Treachery is thus a rather indigestible mixture, although it does bring some fresh insights from across the Atlantic. The author does not organize his material well, and, each time he appears to be coming to a penetrating insight, he backs off and goes off on a different tangent.

Costello was probably the first to debunk the yarn of the engineered recall of Burgess, pointing out the delays in Burgess’s homecoming, and indicating that Burgess’s mother came out to visit him for a week in April 1951, and that he saw her off on a plane (on which he surely could have accompanied her if he had been in a rush), before returning to Washington and New York. Yet most of his observations are erratic: he states that FBI files show that Burgess knew about his flight to Moscow when he was in Washington, and that it was the FBI that secured a delay in the interrogation of Maclean. He cannot make up his mind as to whether the escape on May 25 was a coincidence, although he skillfully debunks the possibility that Philby could have been an informant to the interrogation which Costello assumes was to take place on May 28. (In this he incidentally attributes the Philby myth directly to what Patrick Reilly told him.) He thus points the finger at a ‘high-ranking mole in MI5’, who tipped off Burgess. He also declares that MI5 lied to the FBI in stating that the interrogation had been put back a fortnight from May 28.

He rightly dismisses the importance of Bernard Miller (Burgess’s friend from the Queen Mary), whose role was merely a placeholder for the berth to be occupied by Maclean on the Falaise. Yet he indulges in fantasy concerning Burgess’s visit to Sonning to see the Reeses, claiming that it was at Moscow’s behest, since the MVD was worried that Rees might ‘rat’ once he learned that Burgess was safe in Moscow. Since Burgess had set up the invitation before he even set foot again in Britain, and had spoken to Rees before he even met Modin in mid-May, that does not make sense. Then Costello suddenly suggests that the submission of papers was calculated ‘to give the birds two days to fly the coop’ – a truly shocking declaration. He fails to follow up on this, but does provocatively announce that officials in Southampton noticed Maclean’s name from a watch-list. Did they do anything, or report it? Costello does not appear to be interested.

The author gets into an unholy muddle over the events of the weekend, and the actions of Rees, Liddell and Blunt thereafter. His lack of methodology is obvious. His final flourish is to assert that Blunt had a clear day to scour Burgess’s flat, and he adds that Rosamond Lehmann in 1970 told him that Rees had helped him. That is probably not a trustworthy piece of input. There were enough leads in Costello’s piece for others to follow up, but anyone interested probably got lost in the morass.

The Cambridge Spies by Verne Newton (1991)

Verne Newton was an American historian who tried to bring a disciplined and methodical approach to the study of the Cambridge Spies in America. He closely inspected the chronology of Burgess’s movements, and he concluded that Philby’s account of the ruse to get Burgess sent back to the UK was a complete fabrication, while offering the opinion that it was absurd to suggest that Moscow needed help from two men three thousand miles away from the action. The claim of manipulating US officials over Burgess’s speeding was ‘absurd’. He explained the delay in Burgess’s being sent home to the fact that Ambassador Franks was in London from March 10 to March 28, and thus did not read the scathing letter from Governor Batlle of Virginia until the end of the month. On April 7, the State Department was told that Franks was consulting with the Foreign Office over what action to take with Burgess. By that time, however, Burgess’s mother had arrived, and she and her son went to Charleston on April 5. That was not the behaviour of someone in a hurry to return to the UK, and Newton reports also that Burgess ‘raged’ when he was told the news about his recall around April 18, which did not give the impression of someone racing to salvage matters in London.

Newton was also, I believe, the first person to report that Burgess bumped into Michael Straight before he left Washington, where Straight gave him a warning about exiting the business. Overall, Newton was dumbfounded about the apparent way that the MVD had sacrificed Philby by insisting that Burgess accompany Maclean, and he suggested that, if Maclean had escaped with a Soviet agent, Philby would at least have not been compromised. That was the main failure of Newton’s analysis: he regrettably had only a hazy idea about what was happening in the UK in those summer months of 1951, and did not appear to have studied the British sources that were available at the time he wrote. Yet he made one startling disclosure, namely that Valentine Vivian flew out to Washington in late March to advise Philby that he should get Burgess moved out. That was surely an extravagant gesture, and also one that indicated that the authorities recognized Burgess as an ominous figure early in the cycle.

Thus Newton’s observations concerning the education of the Americans were shallow. They did not seem to have received proper updates from the British: it was a June 7 wire service that alerted them that Burgess and Maclean were missing. Roger Lamphere of the FBI claimed that he had immediately had a hunch that Phiby had been involved, but no indication of a tip-off was given from London at this time. (In an Endnote, Newton reports that the innocent American student Bernard Miller was first referred to as the possible ‘Third Man’ in the Daily Express of June 21, 1951, but this concept was not pursued. When Percy Hoskins wrote a long article on ‘The Missing Diplomats’ for Argosy in January 1953, he made no mention of tip-offs apart from claiming that Burgess returned to the UK with premonitions of an investigation into Maclean.) The State Department received the ambiguous message from London that Morrison had authorized the interrogation of Maclean on May 25, but that it would not take place ‘until May 28 at the earliest’ – not a very convincing statement, given that May 28 was the next full working day. Despite the fact that Roger Lamphere continued to assert that Philby had tipped off Maclean, Newton countered that Philby could not possibly have learned about the date on which Maclean was to be confronted in time to do anything about it. For some unexplained reason, Newton declared that Burgess never thought that he was leaving Britain for ever. His last thought? Why did the Soviets not simply kill Burgess? By not doing so, they sacrificed Philby.

Newton’s book has some value in its perspective from America, but it was a shame that he could not have applied his fresh and more objective methods to a proper investigation of the stories circulating about the Cambridge Five in London. He was ignorant of Dick White’s scheme with the dossier planted on Harvey, and thus exaggerated Harvey’s role. Solving the overall mystery was not the task he set himself, and he closed out his book with a subset of the conundrums that I list below, but he inevitably waded into that water while missing some of the most problematic aspects of the case.

Phase 2: The Soviet Influence

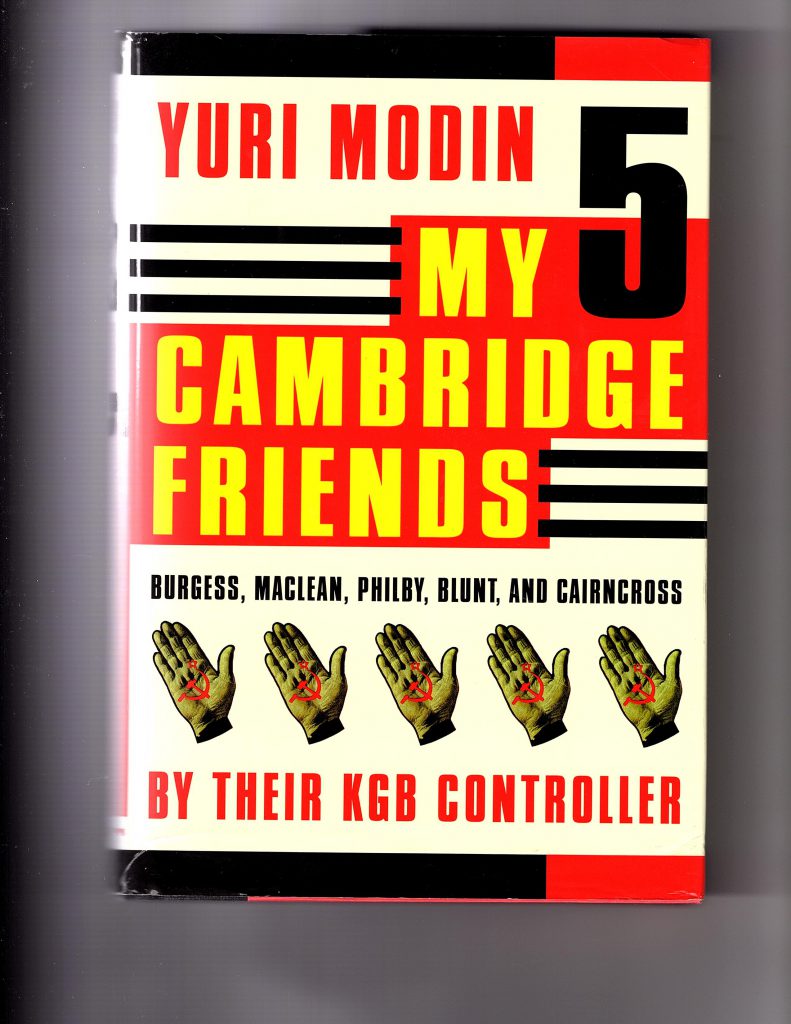

My Five Cambridge Friends by Yuri Modin (1994)

Any volume published in the name of a KGB officer must be treated with scepticism, even if it did appear after the fall of Communism. Thus the account by Modin, the officer (‘Peter’) who controlled the operation in London in 1951, needs to be treated as an item of propaganda, probably magnifying the ingenuity of Soviet intelligence, and minimizing the contributions of lesser-known figures. It also contains some rather obvious contradictions and errors. For instance, Modin was hopelessly wrong about the interactions of Maclean and Burgess in 1950. He had Burgess working in partnership with Maclean in June 1950, after which Maclean had six months’ rest before returning to work at the Foreign Office, where he sent information to Burgess, not dealing with Modin personally. He then asserted that Burgess and Maclean had been ‘more active than ever’ on June 25, 1950, when North Korea invaded the South. Yet Burgess was posted to Washington in August 1950. Maclean was out of action from the end of May until November. Burgess did not return to the UK until May 1951.

Modin’s first tactic was to erase any notion of a KGB (MVD) controller for Philby in the USA, claiming that, for eighteen months he spent in the USA (August 1949 to February 1951, presumably) he ‘never had the least contact with any KGB agent in the USA’, implying, perhaps that he could have done so from March through May, although Makayev was never mentioned. Yet he claimed, without explaining the medium, that Philby was able to send messages to the London residency as early as autumn of 1949 (before Burgess was available as an emissary), and that Modin and his boss, Korovin, were thus able to forward Philby’s reports (such as on Ukraine parachutists, and those concerning the VENONA programme) to Moscow. Meanwhile, he claimed that Blunt had taken over from Burgess as Maclean’s intermediary to the KGB after Burgess was sent to the USA in August 1950, all of which would tend to indicate that Maclean was not isolated, that the London Residency knew what was going on, and that Burgess was not needed to facilitate the escape.

Nevertheless, Modin boosted the story of Philby’s involvement. He granted Philby and Burgess the benefit for taking the initiative when the HOMER short-list was reduced to three in January, and with deciding that both Maclean and the residency should be warned. He next appeared to forget about the established link to London, and accepted that the speeding ruse of February was genuine, since Philby had decided that Burgess needed to go to London to give the alert. He skipped to April 16, when he noted that Burgess had received his notice, and was told that he would leave Washington ‘at the earliest opportunity’. Philby apparently told Burgess just before he left that he was to arrange the defection, but that he must not abscond with Maclean. According to what Modin had already written, Burgess’s involvement was all very unnecessary, and his account sounds very bogus.

After Burgess’s return, his presence did help to take the attention off Blunt, since, if Blunt had been in Maclean’s presence that late in the investigation, it would have endangered him. Even so, Modin had Blunt telling Modin that the arrest would take place in a matter of days, even hours, but that Maclean was at breaking-point, and would not survive interrogation. Thereafter, Modin had Burgess playing a leading role in the conspiracy. After meeting Modin and Korovin, he was ordered to contact Maclean and to persuade (?) him that there was no alternative to defection. At this stage, no suggestion of Burgess’s accompanying Maclean was made. Maclean, however, got sentimental, and claimed that, because of his past affection for Paris, he would never be able to move past the French capital on the road to Moscow. (As if that would stop the KGB, with its ability to anaesthetize and smuggle bodies.) Meanwhile, Maclean was told to involve his wife in the facts of the exfiltration.

Matters then took a strange turn, which confounded Modin. Moscow ordered Burgess to accompany Maclean as a travelling companion, with the pretext that he would be able to return at some stage during the journey to Moscow. Burgess doubted that he would ever make it back, and Modin could not understand why Burgess had agreed to flee without any guarantee of return: his disappearance would immediately incriminate Philby. Modin was puzzled that Moscow could not design some other mechanism for guiding Maclean through France. The Centre, however, showed no concern about Burgess, since he had lost his value. One might conclude (although Modin did not say so) that Moscow had therefore given up on Philby, too. Thus the final stages of the plan were put into motion.

Modin offered a conventional account of the escape: the identification of the Falaise (which Modin claimed he did himself); the purchase of the tickets, with Miller as a false trail; the rented car; the rush to Southampton; the calls from Melinda on Monday morning; the removal by Blunt of items in Burgess’s flat. Modin did nevertheless seem to accept that a decision had been made on May 25 to interrogate Maclean on May 28, while indicating that there had been no leakage, and that it had all been coincidence and good fortune. He still questioned why Burgess had not turned back at Prague, but his return to the UK would immediately have put him under a barrage of questions. And – even though Modin did not state it – that was something that neither Moscow, nor the Foreign Office and MI5, would have wanted.

Modin’s account received a withering review in Hamrick’s Deceiving the Deceivers. Appendix B of that work offers a lively and incisive critique of the feeble attempt by Modin to weave a coherent story from the soup of Philby deceptions, KGB disinformation, and rumours from third parties, of which Modin knew little. It is essential reading.

Treason in the Blood by Anthony Cave-Brown (1994)

Cave-Brown made a brief, awkward insertion in 1994. He somehow interpreted Burgess’s ‘dawdling’ in South Carolina after the motoring offence, and complaint to the Ambassador, as ‘giving Donald Maclean more time’, which was not an asset that he needed. He accepted that Morrison agreed that the interrogation should start on May 28, and noted that Modin did not explain how he learned about that ‘fact’. Cave-Brown also remarked that Maclean’s disappearance was noticed on Monday morning, when he did not appear for work, and yet the remarkable thing about other testimony is that Maclean’s absence was not openly admitted until Melinda Maclean rang the Foreign Office. Sensing darker goings-on, Cave-Brown observed that, in view of Melinda’s story, the Foreign Office was in ‘damage control’, but the writer did not have the nous to pursue this thought.

The Philby Files by Genrikh Borovik (1994)

Hard on the heels of Modin’s contribution arrived Borovik’s expanded account. Borovik was a journalist who conducted interviews with Philby, and claimed that the KGB had shown him excerpts from Philby’s file. He also had conversations with Modin. Borovik showed that he could get out of his depth in the sea of disinformation that naturally swamps these affairs, but he did offer some useful insights.

Contrary to what Modin wrote, Borovik stated that Philby did have vicarious consultations with his Soviet controllers in the winter of 1950-1951, but that Maclean had not had contact for two years, ever since his return from Cairo. Probably because of that, he trusted what Philby told him, namely that the only certain way to warn Maclean was to send Burgess over, and that Philby, Burgess and the intermediary in the USA (unnamed, but the ‘illegal’ Makayev) had agreed that Maclean had to defect. Why Borovik chose to ignore Modin’s testimony that Blunt had been able to act as go-between between Modin and Maclean is not clear. He added that Philby was concerned about Maclean’s ability to stand up to interrogation, although, as he had not seen Maclean since 1940, the reasoning behind that supposition was also fuzzy, and he contradicted his own evidence when he later added that Philby said that it was a mistake to dispatch Maclean then, as he could have rejected all the charges, and slipped away later. Philby apparently was confident that he could withstand interrogation, although he realized that his career would probably be over if the escape were successful.

Thereafter Borovik echoes most of the Modin story, namely about Maclean’s frailty and sentimentality, the decision made by London (or Moscow) that Burgess was safer in Moscow, too, and the bogus offer to have Burgess accompany Maclean before turning back. Borovik blames the KGB for betraying both Burgess and Philby, while he reports Philby’s bitterness over Burgess, believing that it had been Burgess’s decision to accompany Maclean, despite Philby’s strong plea in Washington that he should not do so. Philby harboured that resentment until Burgess died, never even visiting him in hospital on his deathbed. Yet Borovik had one last cracker in his bag: he wrote that Jack Easton, the assistant chief of MI6, in early June 1951 sent a hand-written letter to Philby alerting him to an imminent telegram from London the content of which would be to demand his recall. Philby interpreted this as a possible hint that defection might be appropriate. He did in fact have a plan to do so, through Mexico, but judged that circumstances were not dire enough to warrant such a move at that juncture. If this is reliable information, it bolsters considerably the theory that the British authorities would have rather seen all the spies (and suspected spies) conveniently shoved off to Moscow.

Looking for Mr. Nobody by Jenny Rees (1994, rev. 2000)

Goronwy Rees’s daughter Jenny (who, as a young girl, had been entertained by Burgess in Sonning on that May day in 1951) offered some fresh insights based primarily on what her aunt Mary had witnessed during Burgess’s visit. Overall, Jenny was orthodox in following what her father had written. She writes that Goronwy received two letters from Burgess ‘in the spring of 1951’ – a vague qualification, of course, but reinforcing the importance that Burgess assigned to speaking to Rees as one of his more urgent tasks. Mary told Jenny that Burgess had insisted to Rees that he had got into trouble with the car on purpose – but that may have been part of the deception. Mary also learned that, after Burgess left, Goronwy told his wife, Marge, that he, Burgess, was still a spy, a disclosure that rather undermines the message that Burgess had successfully persuaded Rees to keep silent about his activities.

As far as the important phone calls of the weekend are concerned, the author reinforces the somewhat strained sequence of events. Rees was at All Souls, of course, and on the morning of May 26 (the Saturday) Marge telephoned him to ask, first of all, whether Guy had gone to see him there, as she had received a call from Burgess’s flat-mate (Jackie Hewit, but unnamed), who had called her, and seemed rather hysterical about Guy’s absence. Why Hewit would call the Rees household is not explained: perhaps he had been put up to it, but Burgess knew that Rees was going to be away that weekend. Only after she had relayed that message did Marge go on to explain to her husband that she had received a very strange telephone call from Burgess the previous day, in which Guy was almost completely incoherent. She claimed that she had not paid much attention to what he was saying, but one wonders why she simply did not put the telephone down. Yet the fact of Burgess’s incomprehensible call should probably have been the first thing to report to her husband.

Despite having paid little attention, Marge was able to recall some of what Burgess had said when Goronwy arrived back in Sonning on Sunday evening, and that led to his leaping to the conclusion that Guy had departed for Moscow, setting in train the series of calls that Rees made to Footman and Blunt. It is noteworthy that Jenny writes of Footman ‘with whom he worked at MI6’ – not ‘had worked’ – appearing to confirm that Rees was still working for MI6 during this period, if only part-time. She then adds little to the version of events provided by her father, although she does report that Goronwy, in a very distraught state, very soon afterwards met Stuart Hampshire at a party, and Hampshire told him to do nothing about what he wanted to disclose, and instead to wait it out – advice that he later considered was poor. Lastly, she informs us that Burgess’s telephone call from the Reform Club to the Rees household on May 25 had not been paid for, and that the fact of non-payment was put up on a notice-board for members and inquisitive journalists to see. That was surely another example of Burgess’s flamboyant behaviour in trying to draw attention to his strangled appeals for help in his predicament. It immediately brough unwished-for publicity to the Rees family, and embroiled Goronwy in the saga even more tightly.

The Perfect English Spy by Tom Bower (1995)

The journalist Tom Bower picked up the project of writing a biography of Dick White from Andrew Boyle, who had died in 1991 at the age of seventy-one. He thus assembled his story from inherited notes as well as fresh conversations with White and other participants in the saga of the Missing Diplomats. White gave him a very cagey and deceptive account of events: it is difficult to divine a coherent story from the fragments he provided.

White’s first point is that MI5 had vetoed surveillance at the Maclean house in Tatsfield, presumably because it was too exposed. Yet he hints at the fact that the dwelling was bugged (it was), by indicating that MI5 recorded Burgess’s initial call to Maclean. Amazingly, White claims that he was unaware that Burgess had been ordered home, and he blames Geoffrey Patterson, the representative in Washington, for being remiss. He states, also, that Modin was also unaware of Burgess’s arrival, and learned the fact when he had his regular meeting with Blunt the day after the landing. On the other hand, he blandly echoes the story that Philby and Burgess had engineered the latter’s return to the UK. What is also important is the fact that White twice told Bower that Burgess, before the escape, was not suspected of any complicity, and that he did not believe that Burgess was a spy ‘at the beginning’ (of the investigation, presumably). (As I explained in the Special Bulletin earlier this month, the recently-released PEACH archive proves that Burgess was under suspicion already.)

Modin instructed Burgess to contact Maclean, and White was of the opinion that it was Korovin’s plan that Maclean should flee as soon as possible. Moscow approved the plan, and, since the KGB could not provide an officer to meet Maclean in France (‘leave arrangements, old man’?), Burgess was ordered to accompany Maclean to France, and then to return. Burgess declined this offer, but Korovin apparently convinced him he would be able to get back in time. On the timing of the interrogation, White shows some confusion. He claims that Carey-Foster had sent a message to the FBI indicating that Maclean would be handed over on May 28, and that this happened the same day that Philby wrote to Burgess about the ‘heat’ in Washington. Yet that date, May 21, is impossibly early for the confirmation of Morrison’s decision, and, in any case, as the archives will show, no such information was passed to the FBI at that time, as the Foreign Office and MI5 wished to keep them in the dark still.

White blames Carey-Foster (rather than Makins) for not letting MI5 know that Maclean had taken leave on May 26 – another contradiction, but he does confirm that Carey-Foster received a call from Melinda Maclean at 10:15 on Monday morning. He skates around the hectic communications following that discovery, although he points out (without explaining how the news was received) that Burgess was shown to have been the renter of the car found abandoned in Southampton docks. Liddell informs him and Carey-Foster of the Goronwy Rees episodes (the calls to Footman and Blunt), but White omits to mention that, when he tried to leave for Paris the next morning, he was turned back at the airport since his passport had expired.

The account finishes with a typical Whitean flourish. He asserts that Blunt did indeed manage to check out Burgess’s flat for incriminating papers when Liddell asked him for the keys, and he then describes the various meetings between Rees and Liddell, and Rees and himself. With Liddell conveniently long dead by now, he judges that Liddell himself may have been party to the conspiracy, thus explicitly suggesting that there was some sort of collaboration between MI5-MI6 and the escapees, but one that White himself was nobly detached from. It is a shabby performance. For further analysis of White’s machinations at this time – concerning his planting evidence with the FBI to incriminate Philby – please read https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-devilish-plot/ and https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-tangled-web/.

The Crown Jewels by Nigel West and Oleg Tsarev (1998)

The collaboration between Tsarev and West, abetted by some co-operation from the KGB, shed little light on the events of May 1951, but did disclose some revealing facts about Goronwy Rees, whose connections with the Cambridge Five were perhaps more ominous than he made out. Despite Burgess’s claiming that public opposition to the Nazi-Soviet Pact in September 1939 provided solid justification for severing the relationship between the Comintern and Rees, the KGB archives showed that, as late as 1943, Burgess was still talking about disconnecting him. Moreover, Rees had been given a new cryptonym, FLIT, in place of GROSS, that suggested he was still considered an asset by Moscow Centre. It was at this stage that Burgess raised the question of having Rees eliminated.

In November 1944, Burgess informed his controller Kreshin that Rees had been offered a job by David Footman in MI6, but, a few months later, in March 1945, Burgess claimed that he had talked Footman out of recruiting him, suggesting that the Footman-Burgess relationship was also tighter than it should have been. As we have learned elsewhere, Rees did in fact join MI6 soon afterwards. Nevertheless, Rees was still working furtively with Burgess, as he had tipped him off in 1949 of the imminent arrival of Alex Halpern from the USA. Burgess feared that Rees had Valentine Vivian’s ear, and that Rees might thereby betray him, although he sensed that Rees would do no more than hint, because of his lucrative position with MI6. Anthony Blunt, meanwhile, was very aware of the fact that Burgess had briefly passed Rees on to him in 1939, and that he was clearly in a position where he (Rees) could compromise him. Yet Rees’s darker secrets would perhaps always constitute an inhibitor.

Phase 3: Authorized History

The Sword and the Shield by Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin (1999)

The painstaking exercise undertaken by Vladimir Mitrokhin in copying and secreting a vast number of KGB papers during their transfer to a new vault has provided us with an authentic lode, although not all the items may be genuine. In other words, documents with false information may have been inserted into the files. The process of allowing Andrew exclusive access to, and interpretation of, the file under Secret Service supervision has been criticized, too. For example, David Caute, in Red List, has drawn attention to Andrew’s appointment by Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee, and has pointed out ‘the dangers of granting unique access to one pair of eyes reflecting one perspective, exempt from alternative scrutiny’. Nevertheless, The Sword and the Shield indeed sheds some valuable light. It confirms some important details about Philby’s cut-out, Makayev, indicating that he carried a false Polish passport in the name of Kovalik, and that he left Gdynia on March 5, 1950 with the purpose of his mission to serve Philby. After Burgess’s arrival, Guy acted as an intermediary to Makayev, seeing him in New York on the pretext of visiting Maclean’s brother Alan. At some stage Philby started meeting Makayev in person.

Mitrokhin is a bit sluggish in representing the pace of the HOMER inquiry, but appears to echo the Modin thesis that the credit should be given to Philby and Burgess for coming up with the plan to warn Maclean, finessing the circumstances of Burgess’s recall. According to the files, when Burgess was sent to Maclean to instruct him to defect, Burgess judged that he might decline, because of the need to abandon Melinda: this spravka may have been inserted to protect Melinda’s knowledge and collaboration. On May 17, the London residency was told that Burgess had to accompany Maclean, and Burgess, because of the promise he had made to Philby, became hysterical when he was given the order. The rezident, Rodin, then promised Burgess that he would be free to return: Burgess presumably believed him.

The chronology, characteristically for many of these accounts, then goes a little awry. Moscow Centre was under the impression that Morrison had secretly authorized the interrogation, while the residency believed it would be on May 28, and accordingly made plans for the escape the previous weekend. (The impression is that this was based on an earlier statement of intention by the Foreign Office and MI5, and not any sudden late change on May 24 or May 25.) Burgess was thus instructed to buy tickets on the Falaise. A stock description of the abscondment follows, until Burgess is told in Moscow that he will not be allowed to return. A few loose ends finalize the account: Makayev found Philby very alarmed on May 24, although Philby did not learn the truth until five days later. Makayev let Philby down over a dead-letter box, and was punished for it. Blunt was reported as clearing Burgess’s flat, but he overlooked the Cairncross notes that Colville recognized. Lastly, the book states that Philby never realized that Burgess’s defection was not due to a loss of nerve, but was instead caused by a cynical deception by the KGB.

Anthony Blunt: His Lives by Miranda Carter (2001)

Carter struggles valiantly with a host of conflicting inputs. (She interviewed well over a hundred persons during her research: whether that process leads to clarity or contradiction I cannot say.) She uses her base date as March 30, 1951, when Maclean was solidly identified, but then asserts that MI5 decided to delay a search of the Maclean home until June, because of Melinda’s pregnancy – an odd observation, as if a trawl through the house at that stage would unearth anything incriminating. She accepts the ruse of Burgess’s motoring offences, at the same time stating that Modin’s account cannot be trusted. She has Hewit meeting Burgess and Miller at Southampton, whereafter Burgess went straight to Blunt, who became the go-between to Modin. She judges that Burgess’s hasty visit to Rees (now a ‘zealous anti-communist’) was to gauge whether Rees would tell his secret if the Maclean business blew up.

The days leading up to the escape are fairly conventionally described: Maclean wanted a companion, but Burgess resisted, until he was pressured by Modin to go part of the way. Burgess buys the tickets on the Falaise earlier in the week, but then behaves ‘waywardly’. Carter records Burgess’s call to Margery Rees, and then jumps to Hewit, who reputedly called Blunt on Sunday evening in despair over Burgess’s absence. Against Blunt’s advice, Hewit then called Rees (an event not recorded by him), and Rees went on to call David Footman (‘an old MI6 contact’, but probably still such) and Blunt. When Blunt tried to persuade Rees to keep silent, Carter observes that it was already too late, as Footman had been in touch with Liddell. She has Blunt calling Liddell on May 29, whereupon Liddell gave him the news. It was then, when Liddell asked for the keys to Burgess’s flat, that Blunt was able to get in early and scoop up some items.

Overall, Carter was misled on several counts: the biography is not very enlightening, although the tabulation of the weekend’s telephone-calls will prove useful in a later assessment.

The Hidden Hand by Richard J. Aldrich (2002)

Aldrich does not write much about the Missing Diplomats, but his passages in The Hidden Hand are significant because of his presumed authority as an expert, and the fact that Christopher Andrew cites them in his authorized history of MI5. He starts off with a very casual and confident claim, namely that it was Philby’s tip-off that allowed Burgess and Maclean to ‘evade surveillance and flee eastwards’ – an utterly irresponsible assertion. Yet Aldrich (Professor of International Security at the University of Warwick) is quick to point out that much of the writing on the case has been anecdotal biography, ‘from the Hello! Magazine school of intelligence history’. He has Strang breaking the news about Maclean to Morrison on April 17, when he suggests that MI5 delve into the suspect’s background (as if that had not already been undertaken quite thoroughly already), and on May 25 the Foreign Office proposes that Maclean should be interviewed between June 18 and June 25 – thus apparently scotching the popular story that Maclean was due to be hauled in on May 28. Foreign Secretary Herbert Morrison did not know about the VENONA transcripts, and the problem of evidence, and was thus puzzled why MI5 needed to wait four weeks. He was not told that the pair had disappeared until May 29. Aldrich concludes by noting that the Foreign Office conceded that Morrison had not been told of the suspicions of Philby as the tipoff man.

Aldrich does offer, however, a valuable insight into the way that Morrison (who had only recently replaced Ernest Bevin) was kept in the dark by his Foreign Office bureaucrats. Late in 1955 (after the White Paper had been published) Morrison made some discreet inquiries among his friends, and he discovered that Maclean had lunched with Anthony Blake the day before he escaped. In October he spoke to Blake, who told him that Maclean had been very relaxed, adding that he was sure ‘that he had been tipped off some time after and at very short notice’. That sounds more like a post hoc rationalization, but Blake added that Maclean had always been a fervent Communist, that the White Paper had been misleading about the longevity of his commitments, and that he himself had been shocked to learn that Maclean had gained entry to the Foreign Office with such a background. Aldrich used the Morrison papers as the authority for this story.

Deceiving the Deceivers by S. J. Hamrick (2004)

Certainly out of place in a section titled ‘Authorized Histories’ is S. J. Hamrick’s convoluted and very weird extended hypothesis about MI5 counter-espionage, Deceiving the Deceivers. I include it primarily because of the way it abuses the facts of early 1951, but also for what may turn out to be more valuable insights about the use of VENONA, and the possibility that Maclean had been identified as HOMER as early as 1949. For a fuller critique of the book, and for my interpretation of Hamrick’s theory, I strongly encourage readers to turn to my 2019 story about Dick White’s plotting to plant accusatory information on the FBI, at https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-devilish-plot/. There you will learn that (according to Hamrick’s fertile imagination) Philby was sent out Washington in 1949, Burgess was retrieved from ignominy to join him in the summer of the next year, and Maclean was re-instated at the American desk in London, after his destructive behaviour in Cairo, in November 1950, all for the purposes of providing disinformation about US/GB nuclear weapons – at a time when both Philby and Maclean had no direct contact with the MGB, by the way. This was all Dick White’s scheme, apparently, whereby he also hoped to entrap all three of the known (or suspected) Soviet agents.

What Hamrick did bring to the table was a close inspection of the VENONA records, concluding that GCHQ concealed the results of its early decryptions. He thus managed to indicate that the official identification of Maclean as HOMER in April 1951 occurred two years later than the date on which it actually was resolved, and that the institution was caught on the back foot by the US revelations concerning VENONA in 1995. It will be worth inspecting the supportive detail for these claims, especially since we now have a paper-trail of the (supposed) investigations into HOMER that took place in 1950 and 1951 – on the sluggishness of which I have myself remarked. It may well be that White was able to delay the fruits of Eastcote’s labours for some purpose. Yet Hamrick is hopelessly confused and contradictory when it comes to the timetable for Philby’s sending Burgess back to London (a ‘fact’ he accepts). For example, he describes Philby as having known since September 1949 that Maclean was under suspicion, but a few lines later has him meeting Makayev in May 1951 for help in removing Maclean from England. Moreover, Philby had sent Burgess home as late as April (!), having learned about the critical VENONA decryption: Hamrick ignores all the shenanigans with Burgess and the Embassy. One of the many problems with Hamrick’s narrative is that it is never clear when he is just re-presenting established wisdom and when he is promoting one of his crackpot theories.

Defend the Realm [US title] by Christopher Andrew (2009)

A few years passed before the long-awaited authorized history of MI5 appeared. One might have expected the Professor (now Emeritus Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Cambridge) to have been able to exploit some relevant MI5 and Foreign Office files. Yet, for the critical period leading up to May 25 he offers only three items from ‘Security Service Archives’ – all unidentified, of course – and none at all from Foreign Office, or Foreign and Colonial Office files. The three are all fairly inconsequential items to do with surveillance, or the lack of it, and it appears that Andrew was not allowed to inspect the whole file on the surveillance. He thus relies primarily on Philby, Modin, Aldrich and Mitrokhin for his sources, with a couple of references to Borovik and Costello-Tsarev.

Andrew’s account turns out to be primarily a rehash of what he wrote in The Sword and the Shield: the role of Makayev, the plan hatched by Philby and Burgess, the insistence that Burgess accompany Maclean, and Burgess’s resistance, the plans made the previous weekend; the residency’s discovering the Falaise opportunity, and Burgess being commanded to book the tickets. Most of the details between Burgess’s arrival and the escape day of May 25 are skipped over: Andrew relies on Aldrich for the proposal to interrogate Maclean in June, but claims that the London residency believed that Maclean was going to be arrested on May 28 (but he does not explain how it gained this insight). Yet he ignores what Aldrich wrote about Philby’s tip-off. Why Andrew should be so reliant on a secondary source, but then selectively use what that source wrote without exploring the contradictions is an enigma in its own right.

Yet the issuance of an ‘authorized’ account was presumably designed to quash any inquisitive minds, as if the last word on the episode had been written. MI5 and the Foreign Office must have felt fairly pleased with themselves, and, after a few years of letting the dust settle, showed their generosity by releasing a shaft of files that undermined what their chosen historian had written. I do not know what was Andrew’s reaction to inspecting the 2015 batch (I assume that he has done so). Defend the Realm definitely needs a revision.

The Petrov Files (2011)

In 2011 an enormous trove of records, designated as the Personal File on Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov, who defected in Australia in 1954, was released to the National Archives in Kew. It contains not only the complete transcripts of the Australian Royal Commission Investigation into Soviet Espionage, and its final Report, but a very rich record of exchanges between MI5 and its Security Liaison Officer in Canberra in the years 1954, 1955, and 1956, including some very revealing memoranda about Burgess and Maclean. I do not believe that anyone has performed justice to it yet. (I shall present my initial analysis next month.)

Treachery by Chapman Pincher (2011 & 2012)

I include this volume only because it is the book that probably has been read the most, while it has had an influence completely disproportionate to its value. Pincher covered the saga of the Missing Diplomats without providing any references, and he was exceedingly neglectful of the need to provide proper dating of the events. He clearly had access to some Security Service records not yet released, and was undoubtedly assisted by Peter Wright. He clumsily inserted Roger Hollis as a regular accomplice to Dick White, since his objective was to prove that Hollis was a Soviet mole. He accepted that Burgess’s trip home was engineered by Philby, and he declared that Maclean was indeed about to be hauled in on May 28, just after he disappeared. He made many other mistakes.

Guy Liddell’s Diaries

In 2012, Guy Liddell’s Diaries were declassified, and released to the National Archives. The entries for 1951 appeared as KV 4/473. They are an indispensable resource for understanding the events of this year – or for any of the other years when Liddell was active. Overall, they are probably very reliable, although Liddell was guilty of some occasional dissimulation. And they have been redacted – severely, in some places. Many of the individual names redacted can be confidently assessed, from context and from other sources, but large chunks of text have been irretrievably lost. The act of censorship itself points to the fact that what Liddell wrote must have been far too sensitive to be revealed, and a variety of ‘traffic analysis’ can constitute an important part of the intellectual process of interpreting such passages.

Phase 4: The Release of the Archives

In the hiatus before the critical archives were declassified, a few relevant biographies appeared. Michael Holzman, an American described simply as a ‘writer’, supplied two of them, both self-published. Guy Burgess: Revolutionary in an Old School Tie (2012) displays his approach of digging around in obscure places to reveal fresh facts, but Holzman never applies any rigorous methodology to the treatment of his material. Thus he discovers that Wilfred Mann (listed by Boyle as a possible conspirator) echoes the story of Philby’s ruse in getting Burgess home, and ascribes to Philby the foresight to have made plans well before the reduction of the short-list of suspects in mid-April. He sheds some fresh light on Burgess’s movements that spring, including a visit to W. H. Auden in New York on March 17. Holzman has inspected Blunt’s memoir at the British Library, and appears to trust what the spy wrote, for instance that it was Burgess’s own decision that he should defect, even though Burgess told him he had been ordered to do so. He also adds that Burgess visited Blunt at Portman Square on the afternoon of May 25 to say ‘goodbye’. He reinforces the notion that Bernard Miller was a ‘pick-up’ on the Queen Mary, and that Hewit, having been introduced to Miller when the latter arrived from Paris on May 21, called him in the morning of May 26 in an attempt to discover where Burgess was. All in all, it is a flat and uninspiring account.

Holzman took up his pen again in a treatment of the Macleans in 2014, namely Donald and Melinda Maclean: Idealism and Espionage. The work is even less enthralling than his book on Burgess. He informs us that Tatsfield could be reached by train and taxi via Oxted, perhaps a journey of two hours, which is both overstated and irrelevant, and writes that Maclean was receiving highest-classification papers as late as April 5. Thereafter he muses about the possible motives and intentions of the Soviets without ever coming off the fence, while reinforcing the notion that Miller was ‘Burgess’s last lover’. Lastly, he throws in the notion that a decision was taken to interrogate Maclean on the morning of May 28, but lazily does not explore this newly-found datum.

A Spy Among Friends by Ben Macintyre (2014)

Macintyre brought his celebrated journalistic flair to his 2014 study of Philby. It contains some shrewd insights, quite a few unsupported assumptions, as well as many careless mistakes. He has little to say on the escape, but the build-up at Philby’s end should have revealed useful information. He describes Philby’s briefing on the HOMER investigation before he leaves for Washington – but oddly does not mention Maurice Oldfield. He introduces Makayev by claiming that the Soviet illegal managed to inform Philby that he had arrived, and that they would ‘rendezvous at different points between New York and Washington, in Baltimore or Philadelphia’, but Macintyre provides no source for this startling tale. Furthermore, he then explains that Burgess was able to act as a courier soon after he arrived, taking information to Makayev in New York. In June 1950, Philby learned that the VENONA project had identified an important spy active in 1945 in the British network with the cryptonym STANLEY – himself.

It was only when Philby heard of the critical decryption involving Melinda Maclean in New York that he apparently ‘demanded’ that Maclean be extracted before interrogation, and Macintyre echoes the dubious story that Philby’s delay was occasioned by Moscow’s insistence that Maclean stay in place. Here Macintyre correctly interprets the Burgess recall as an item of luck, an opportunity to warn Maclean, yet puts an odd spin on the saga. Maclean would be warned by ‘a third party who would not arouse suspicion’, a rather naïve observation given Burgess’s recent track-record. He further slips up by saying that the plan would involve Burgess’s contacting the Soviets in London: of course he did no such thing, using Blunt as go-between. Thereafter, Macintyre trots out aspects of the error-prone familiar story (Tatsfield in Kent, Miller the ‘boyfriend’), and echoes the claim that Modin thought Maclean would be interrogated on Monday, May 28, without commenting on whether that belief had any relevance to the escape plan. He adds that the escape plan ‘swung into action’ only on May 25, but it had been in the works for some days. Lastly, he has Modin insisting that Burgess accompany Maclean, but later acknowledging that ‘allowing’ Burgess to leave had been an error. He provides the information that Special Branch reported that a car hired by Guy Burgess had been abandoned at Southampton, but does not provide any timing for this important event. Overall, it is a gripping but rather shallow story.

Stalin’s Englishman by Andrew Lownie (2015)

Andrew Lownie, perhaps better known as a literary agent, outdid Miranda Carter in the number of persons he acknowledged for helping him in his biography of Burgess, with a cast of over two hundred listed. A writer needs good discriminatory powers to separate the gold from the dross when treating input from so many sources. While that exercise may have enabled Lownie to provide a rich scrapbook of his subject’s activities, it did not lead to any greater clarity on the escape. He recapitulates the summons of Burgess to Ambassador Franks’ office, but then interjects that Burgess went over the ‘escape plan’ with Philby on April 30 – surely a premature assessment. He then has Blunt meeting Burgess at Southampton, where they immediately discuss plans for Maclean’s exfiltration – another item of inaccurate chronology. For Burgess’s return to the flat in new Bond Street, and his reunion with Hewit on May 9 (thus contradicting other accounts that have Hewit welcoming Burgess at Waterloo Station), he relies on Hewit’s ‘unpublished memoir’. The provenance of this work does not appear to be acknowledged anywhere else, and its reliability (let alone its existence) should probably not be trusted very implicitly. It is here, however, that Hewit discloses the ‘wads of money’ he found in Burgess’s suitcase.

Lownie’s mingled yarn then borrows from Modin, Roland Perry, Andrew, Costello/Tsarev, and what Patrick Reilly told him. Reilly told him that Carey-Foster had recommended that Burgess be surveilled, too (probably correct), but Lownie next oddly remarks that Maclean was tailed to and from Victoria and [sic] Charing Cross each day to the ‘little station at Tatsfield’ (there was, of course, no such edifice). Before Moscow sent detailed plans for the escape on May 17, the final plans for interrogation were drawn up on May 15 (Reilly), and the group met in Strang’s office again on May 21, where Dick White pressed for a delay in informing the FBI, in case Maclean happened to crack and incriminate himself soon. Somehow, the plans were telegraphed to Philby on May 24: Reilly told Lownie that the interrogation was due to begin the week of May 28, and Lownie notes that Reilly’s papers at the Bodleian Library indicate that it would probably take place on the Monday.

The author offers some fascinating details about the fateful week that culminated in the escape. Bernard Miller arrived from Paris on May 21, and was introduced to Hewit and others. Hewit was then told that Burgess and Miller were going away for a weekend together: this may not have pleased Burgess’s housemate, but it throws into a cocked hat the notion that Hewit would have been ‘hysterical’ when Burgess did not return by Saturday morning. Hewit also recalled (in his notorious memoir) that Burgess told him that he was helping a friend from the Foreign Office, and that he would be back on Monday, at which Hewit outrageously claimed that he guessed that the friend was Donald Maclean. Meanwhile, Burgess had booked the berth on the Falaise in the names of himself and Miller, and was laying the false trails about his intended itinerary.

Suddenly, Lownie inserts a valuable archival reference, from the Security Conference of Privy Counsellors (CAB 134/1325, declassified in December 2006), in which Morrison’s decision of May 25 to interrogate Maclean the following month is made explicit. (Lownie overlooks the clash with Reilly’s testimony.) He records Burgess’s visit to Blunt on May 25 (probably from Hewit, again), and then relates the awkwardness of Roger Makins when he bumped into Maclean in the Foreign Office courtyard around 6:00 pm and learned about Maclean’s day off, but could not find Carey-Foster to verify that leave had been granted. Maclean then caught the ‘usual train’ from Charing Cross: not only was it the wrong terminus, but Maclean would not have been able to catch the 6:10 from Victoria if Makins’s timetable is correct. Whatever the circumstances, Burgess arrived at the Tatsfield house shortly after Maclean arrived.

The plot is lost completely after that. Lownie relies on West’s Molehunt (see above) to report that an immigration official at Southampton had noticed Maclean’s name on a watch list, and that he ‘immediately rang MI5’s operational headquarters in London, Leconfield House, where a number of officers were still planning the Monday interview’. So much for Morrison’s approval for a June interrogation. The inability to cross-check one’s own facts (and for Nigel West, who is thanked for checking the script, not to notice the anomaly) is unforgiveable. Lownie then adds a provocative flourish: Winston Churchill was reportedly informed of the abscondment at Chartwell on the Saturday, May 26.

It was not the last of the contradictions, however. Lownie writes that Hewit called Blunt on the evening of May 26 to tell him that Burgess had not returned from his ‘overnight trip’ (when it was for the weekend). Yet Lownie also cites Freeman & Penrose (Conspiracy of Silence), who actually wrote (based on an interview with Hewit in 1985) that Hewit was perturbed at the fact that Burgess had not returned on Sunday evening, and thought he might have stayed with Blunt that night. Hewit did not call Blunt immediately, however: he instead called Rees on Monday morning, and only then Blunt, who told him not to do anything. And then the search of the flat occurred. He also reproduces Rees’s testimony about the frenzied telephone calls. Finally, he asserts (using Reilly) that Makins thought that Maclean might have taken the Monday off as well – an extraordinary suggestion, although, as I shall show, that claim came also from Carey-Foster. Lownie then describes Blunt’s attempts to hush up Hewit, and then relates how Blunt acquired the key to the Burgess premises on May 30, sent Hewit away, and searched the flat with MI5’s Ronnie Reed, when he was able to retrieve some incriminating love letters.

Stalin’s Englishman was well-received by the critics, and it won several prizes (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stalin%27s_Englishman). It is quite astounding to me that its multiple flaws were overlooked.

The 2015 Archival Releases

For the purposes of examining the events leading up to, and occurring immediately after, the defection of Burgess and Maclean, I consider the following the most important:

MI5’s Personal Files on Burgess (especially the series KV 2/4102 through KV 2/4116). This set is not exclusive: there are many others in the range from 4101 to 4139, but I suspect that this core represents the most valuable material. While the record does not start until after the defection, the interviews with Burgess’s friends and associates frequently bring up valuable refinements of the received wisdom, including (but by no means limited to) interviews with Anthony Blunt, whose testimony of course cannot be relied upon. The files named above extend to 1956, when Driberg interviewed Burgess in Moscow, and when Goronwy Rees’s articles in the People appeared, thus offering an important perspective, and sometimes a correction, to the established interpretation of events.

MI5 also released a rich file on the surveillance of Donald Maclean (and his mother) in KV 2/4140, digitized for general availability, an item that also reaches back to 1949 in some detail, and includes an account of Liddell’s interviews with Blunt and Tomás Harris. This is an extremely important file, since it shows that MI5’s watchers were in fact more persistent and mobile than has been presented before, and it also confirms the startling information (hinted at in some works) that MI5 inserted telephone bugs in several properties, including the Macleans’ house in Tatsfield and the residence of Donald’s mother in London. It gives a day-by-day analysis of Maclean’s movements in May, including his meetings with Burgess and others, except when, for a few incidents, the watchers lost track of him. A larger tranche of files on Maclean has also been released, namely KV 2/4141-4164, but unfortunately not digitized. These must constitute a critical source, but I do not believe anyone has mined them properly yet. I have yet to inspect them.

Another MI5 series, KV 6/140-145, described as the ‘Investigation into leakage of telegrams’ is a vital account of the VENONA exercise, starting in January 1945, and ending in February 1956, with the most intense scrutiny taking place between April 2 and June 7, 1951 (KV 6/142 & 143). (I used these files in my examination of Dick White’s role in https://coldspur.com/dick-whites-devilish-plot/, from June 2019.)

The remainder of my selection comes from the Foreign and Colonial Office files, series FCO 158. FCO 158/1-16 provide a valuable series concerning the leaks and investigations after the disappearance, but some are still closed. The set FCO 158/24 through 158/28 deals with the initial inquiry into the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean, with the last two dedicated to the PEACH inquiry, namely the possible role that Philby had played in the affair. FCO 158/133 investigates the possible continuance of Soviet Agents in the Foreign Service, and Philby as the ‘Third Man’ is importantly covered in a file from 1955, FCO 158/175. The Investigation continues in FCO 158/176 & 177, with a draft statement from 1954 recorded in FCO 158/180. Burgess has his own FCO file in FCO 158/181 & 182, while Goronwy Rees’s profile on ‘Burgess’ is maintained at FCO 158/184. Finally, the Foreign and Colonial office kept its own file on the defector Vladimir Petrov (distinct from Petrov’s extensive files in MI5’s KV 2 series) at FCO 158/198 & 199.

I have so far studied few of these files, but am attempting to work my way through them.

Phase 5: Post-Archival Exploitation

Guy Burgess: The Spy Who Knew Everyone, by Stewart Purvis and Jeff Hulbert (2016) is a more measured and thoughtful study of Burgess’s life, again broad and detailed in its sweep, but more selective and less impressionable. The authors start their ‘Acknowledgements’ by stating that ‘much of the content of this book is based on files which were only made available at the end of October 2015’. Their editor thus had the unenviable task of getting their work to the printers within six weeks. Exactly how much time they were able to spend perusing the masses of files is not clear, but they made some judicious choices. From the sources given, the authors appear to have spent more time investigating the post-mortems on Burgess’s disappearance, and his previous career, than the flight itself, and the account of the events of May is therefore somewhat incurious and vague.